- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Technical Writing

How to Write an Index

Last Updated: January 25, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 2,007,566 times.

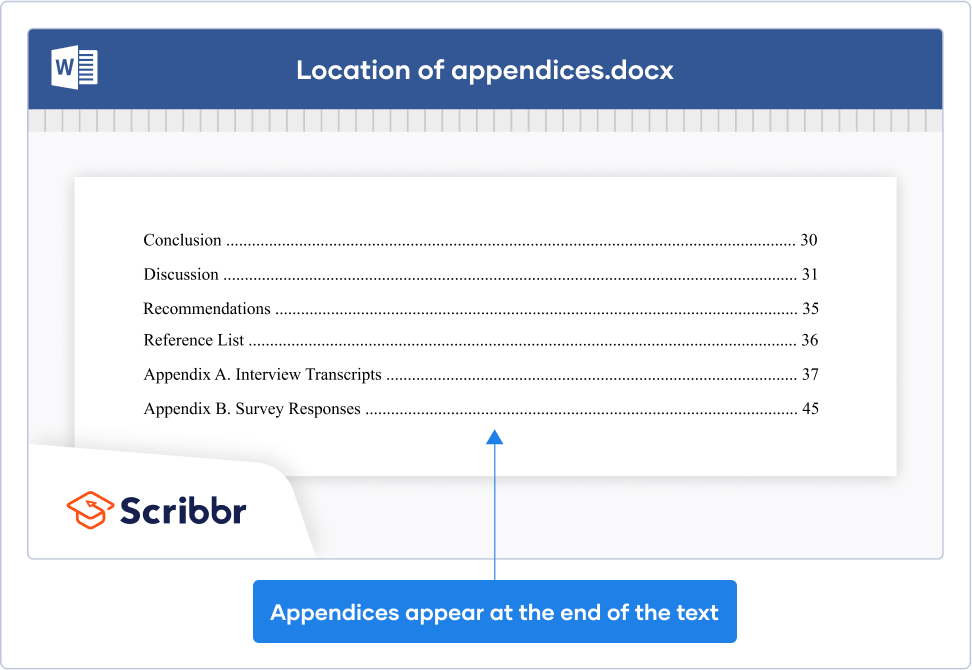

An index is an alphabetical list of keywords contained in the text of a book or other lengthy writing project. It includes pointers to where those keywords or concepts are mentioned in the book—typically page numbers, but sometimes footnote numbers, chapters, or sections. The index can be found at the end of the work, and makes a longer nonfiction work more accessible for readers, since they can turn directly to the information they need. Typically you'll start indexing after you've completed the main writing and research. [1] X Research source

Preparing Your Index

- Typically, if you index from a hard copy you'll have to transfer your work to a digital file. If the work is particularly long, try to work straight from the computer so you can skip this extra step.

- If footnotes or endnotes are merely source citations, they don't need to be included in the index.

- Generally, you don't need to index glossaries, bibliographies, acknowledgements, or illustrative items such as charts and graphs.

- If you're not sure whether something should be indexed, ask yourself if it contributes something substantial to the text. If it doesn't, it typically doesn't need to be indexed.

- In most cases, if you have a "works cited" section appearing at the end of your text you won't need to index authors. You would still include their names in the general index, however, if you discussed them in the text rather than simply citing their work.

- For example, if you're writing a book on bicycle maintenance, you might have index cards for "gears," "wheels," and "chain."

- Put yourself in your reader's shoes, and ask yourself why they would pick up your book and what information they would likely be looking for. Chapter or section headings can help guide you as well.

- For example, a dessert cookbook that included several types of ice cream might have one entry for "ice cream," followed by subentries for "strawberry," "chocolate," and "vanilla."

- Treat proper nouns as a single unit. For example, "United States Senate" and "United States House of Representatives" would be separate entries, rather than subentries under the entry "United States."

- Stick to nouns and brief phrases for subentries, avoiding any unnecessary words.

- For example, suppose you are writing a book about comic books that discusses Wonder Woman's influence on the feminist movement. You might include a subentry under "Wonder Woman" that says "influence on feminism."

- For example, if you were writing a dessert cookbook, you might have entries for "ice cream" and "sorbet." Since these frozen treats are similar, they would make good cross references of each other.

Formatting Entries and Subentries

- The style guide provides specifics for you in terms of spacing, alignment, and punctuation of your entries and subentries.

- For example, an entry in the index of a political science book might read: "capitalism: 21st century, 164; American free trade, 112; backlash against, 654; expansion of, 42; Russia, 7; and television, 3; treaties, 87."

- If an entry contains no subentries, simply follow the entry with a comma and list the page numbers.

- People's names typically are listed alphabetically by their last name. Put a comma after the last name and add the person's first name.

- Noun phrases typically are inverted. For example, "adjusting-height saddle" would be listed in an index as "saddle, adjusting-height." [8] X Research source

- Avoid repeating words in the entry in the subentries. If several subentries repeat the same word, add it as a separate entry, with a cross reference back to the original entry. For example, in a dessert cookbook you might have entries for "ice cream, flavors" and "ice cream, toppings."

- Subentries typically are listed alphabetically as well. If subentry terms have symbols, hyphens, slashes, or numbers, you can usually ignore them.

- If a proper name, such as the name of a book or song, includes a word such as "a" or "the" at the beginning of the title, you can either omit it or include it after a comma ("Importance of Being Earnest, The"). Check your style guide for the proper rule that applies to your index, and be consistent.

- When listing a series of pages, if the first page number is 1-99 or a multiple of 100, you also use all of the digits. For example, "ice cream: vanilla, 100-109."

- For other numbers, you generally only have to list the digits that changed for subsequent page numbers. For example, "ice cream: vanilla, 112-18."

- Use the word passim if references are scattered over a range of pages. For example, "ice cream: vanilla, 45-68 passim . Only use this if there are a large number of references within that range of pages.

- Place a period after the last page number in the entry, then type See also in italics, with the word "see" capitalized. Then include the name of the similar entry you want to use.

- For example, an entry in an index for a dessert cookbook might contain the following entry: "ice cream: chocolate, 4, 17, 24; strawberry, 9, 37; vanilla, 18, 25, 32-35. See also sorbet."

- For example, a beginning cyclist may be looking in a manual for "tire patches," which are called "boots" in cycling terms. If you're writing a bicycle manual aimed at beginners, you might include a "see" cross reference: "tire patches, see boots."

Editing Your Index

- You'll also want to search for related terms, especially if you talk about a general concept in the text without necessarily mentioning it by name.

- If you have any entries that are too complex or that might confuse your readers, you might want to simplify them or add a cross reference.

- For example, a bicycle maintenance text might discuss "derailleurs," but a novice would more likely look for terms such as "gearshift" or "shifter" and might not recognize that term.

- For example, you might include an entry in a dessert cookbook index that read "ice cream, varieties of: chocolate, 54; strawberry, 55; vanilla, 32, 37, 56. See also sorbet."

- Generally, an entry should occur on two or three page numbers. If it's only found in one place, you may not need to include it at all. If you decide it is necessary, see if you can include it as a subentry under a different entry.

- For example, suppose you are indexing a dessert cookbook, and it has ice cream on two pages and sorbet on one page. You might consider putting these together under a larger heading, such as "frozen treats."

- You may want to run searches again to make sure the index is comprehensive and includes as many pointers as possible to help guide your readers.

- Make sure any cross references match the exact wording of the entry or entries they reference.

- Indexes are typically set in 2 columns, using a smaller font than that used in the main text. Entries begin on the first space of the line, with the subsequent lines of the same entry indented.

Expert Q&A

- If creating an index seems like too large of a task for you to complete on your own by the publisher's deadline, you may be able to hire a professional indexer to do the work for you. Look for someone who has some knowledge and understanding about the subject matter of your work. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Make the index as clear and simple as you can. Readers don't like looking through a messy, hard-to-read index. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you're using a word processing app that has an indexing function, avoid relying on it too much. It will index all of the words in your text, which will be less than helpful to readers. [15] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://ugapress.org/resources/for-authors/indexing-guidelines/

- ↑ https://www.hup.harvard.edu/resources/authors/pdf/hup-author-guidelines-indexing.pdf

- ↑ https://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/CHIIndexingComplete.pdf

- ↑ https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/publish-with-us/from-manuscript-to-finished-book/preparing-your-index

About This Article

An index is an alphabetical list of keywords found in a book or other lengthy writing project. It will have the chapters or page numbers where readers can find that keyword and more information about it. Typically, you’ll write your index after you’ve completed the main writing and research. In general, you’ll want to index items that are nouns, like ideas, concepts, and things, that add to the subject of the text. For example, a dessert cookbook might have an entry for “ice cream” followed by subentries for “strawberry,” “chocolate,” and “vanilla.” To learn how to format your index entries, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lisa Nielsen

May 30, 2017

Did this article help you?

Oct 25, 2016

Caroline Mckillop

Oct 16, 2019

Maureen Leonard

Jul 5, 2016

Graham Lidiard

Aug 3, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

What Is a Journal Index, and Why is Indexation Important?

- Research Process

- Peer Review

A journal index, or a list of journals organized by discipline, subject, region and other factors, can be used by other researchers to search for studies and data on certain topics. As an author, publishing your research in an indexed journal increases the credibility and visibility of your work. Here we help you to understand journal indexing better - as well as benefit from it.

Updated on May 13, 2022

A journal index, also called a ‘bibliographic index' or ‘bibliographic database', is a list of journals organized by discipline, subject, region or other factors.

Journal indexes can be used to search for studies and data on certain topics. Both scholars and the general public can search journal indexes.

Journals in indexes have been reviewed to ensure they meet certain criteria. These criteria may include:

- Ethics and peer review policies

- Assessment criteria for submitted articles

- Editorial board transparency

What is a journal index?

Indexed journals are important, because they are often considered to be of higher scientific quality than non-indexed journals. You should aim for publication in an indexed journal for this reason. AJE's Journal Guide journal selection tool can help you find one.

Journal indexes are created by different organizations, such as:

- Public bodies- For example, PubMed is maintained by the United States National Library of Medicine. PubMed is the largest index for biomedical publications.

- Analytic companies- For example: the Web of Science Core Collection is maintained by Clarivate Analytics. The WOS Core Collection includes journals indexed in the following sub-indexes: (1) Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE); (2) Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI); (3) Arts & Humanities Citation Index (AHCI); (4) Emerging Sources Citation Index.

- Publishers- For example, Scopus is owned by Elsevier and maintained by the Scopus Content Selection and Advisory Board . Scopus includes journals in all disciplines, but the majority are science and technology journals.

Key types of journal indexes

You can choose from a range of journal indexes. Some are broad and are considered “general indexes”. Others are specific to certain fields and are considered “specialized indexes”.

For example:

- The Science Citation Index Expanded includes mostly science and technology journals

- The Arts & Humanities Citation Index includes mostly arts and humanities journals

- PubMed includes mostly biomedical journals

- The Emerging Sources Citation Index includes journals in all disciplines

Which index you choose will depend on your research subject area.

Some indexes, such as Web of Science , include journals from many countries. Others, such as the Chinese Academy of Science indexing system , are specific to certain countries or regions.

Choosing the type of index may depend on factors such as university or grant requirements.

Some indexes are open to the public, while others require a subscription. Many people searching for research papers will start with free search engines, such as Google Scholar , or free journal indexes, such as the Web of Science Master Journal List . Publishing in a journal in one or more free indexes increases the chance of your article being seen.

Journals in subscription-based indexes are generally considered high-quality journals. If the status of the journal is important, choose a journal in one or more subscription-based indexes.

Most journals belong to more than one index. To improve the visibility and impact of your article, choose a journal featured in multiple indexes.

How does journal indexing work?

All journals are checked for certain criteria before being added to an index. Each index has its own set of rules, but basic publishing standards include the following:

- An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN). ISSNs are unique to each journal and indicate that the journal publishes issues on a recurring basis.

- An established publishing schedule.

- Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) . DOIs are unique letter/number codes assigned to digital objects. The benefit of a DOI is that it will never change, unlike a website link.

- Copyright requirements. A copyright policy helps protect your work and outlines the rules for the use or sharing of your work, whether it's copyrighted or has some form of creative commons licensing .

- Other requirements can include conflict of interest statements, ethical approval statements, an editorial board listed on the website, and published peer review policies.

To be included in an index, a journal must submit an application and undergo an audit by the indexation board. Index board members (called auditors) will confirm certain information, such as the full listing of the editorial board on the website, the inclusion of ethics statements in published articles, established appeal and retraction processes, and more.

Why is journal indexing important?

As an author, publishing your research in an indexed journal increases the credibility and visibility of your work. Indexed journals are generally considered to be of higher scientific quality than non-indexed journals.

With the growth of fully open access journals and online-only journals, recognizing “predatory” journals and their publishers has become difficult. Indexing a journal in one or more well-known databases is a good sign the journal is credible.

Moreover, more and more institutions are requiring publication in an indexed journal as a requirement for graduation, promotion, or grant funding.

As an author, it is important to ensure that your research is seen by as many eyes as possible. Index databases are often the first places scholars and the public will search for specific information. Publishing a paper in a non-indexed journal could be harmful in this context.

However, there are some exceptions, such as medical case reports.

Many journals don't accept medical case reports because they don't have high citation rates. However, several primary and secondary journals have been created specifically for case reports. Examples include the primary journal, BMC Medical Case Reports, and the secondary journal, European Heart Journal - Case Reports.

While many of these journals are indexed, they may not be indexed in the major indexes, though they are still highly acceptable journals.

Open access and indexation

With the recent increase in open access publishing, many journals have started offering an open access option. Other journals are completely open access, meaning they do not offer a traditional subscription service.

Open access journals have many benefits, such as:

- High visibility. Anyone can access and read your paper.

- Publication speed. It is generally quicker to post an article online than to publish it in a traditional journal format.

Identifying credible open access journals

Open access has made it easier for predatory journal publishers to attract unsuspecting or new authors. These predatory journal publishers often publish any article for a fee without peer review and with questionable ethical and copyright policies. Here we show you eight ways to spot predatory open access journals .

One way to identify credible open access journals is their index status. However, be aware that some predatory journals will falsely list indexes or display logos on their website. It is good practice to make sure the journal is indexed on the index's website before submitting your article to that journal.

Major journal indexing services

There are several journal indexes out there. Some of the most popular indexes are as follows:

Life Sciences and Hard Sciences

- Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) Master Journal List

- Engineering Index

- Web of Science (now published by Clarivate Analytics, formerly by ISI and Thomson Reuters)

- Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)

Humanities and Social Sciences

- Arts & Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) Master Journal List

- Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) Master Journal List

Indexation and impact factors

It is easy to assume that indexed journals will have higher impact factors, but indexation and impact factor are unrelated.

Many credible journals don't have impact factors, but they are indexed in several well-known indexes. Therefore, the lack of an impact factor may not accurately represent the credibility of a journal.

Of course, impact factors may be important for other reasons, such as institutional requirements or grant funding. Read this authoritative piece on the uses, importance, and limitations of impact factors .

Final Thoughts

Selecting an indexed journal is an important part of the publication journey. Indexation can tell you a lot about a journal. Publishing in an indexed journal can increase the visibility and credibility of your research. If you're having trouble selecting a journal for publication, consider learning more about AJE's journal recommendation service .

Catherine Zettel Nalen, MS

Academic Editor, Specialist, and Journal Recommendation Team Lead

See our "Privacy Policy"

The Differences Between Indexes and Scales

Definitions, Similarities, and Differences

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Indexes and scales are important and useful tools in social science research. They have both similarities and differences among them. An index is a way of compiling one score from a variety of questions or statements that represents a belief, feeling, or attitude. Scales, on the other hand, measure levels of intensity at the variable level, like how much a person agrees or disagrees with a particular statement.

If you are conducting a social science research project, chances are good that you will encounter indexes and scales. If you are creating your own survey or using secondary data from another researcher’s survey, indexes and scales are almost guaranteed to be included in the data.

Indexes in Research

Indexes are very useful in quantitative social science research because they provide a researcher a way to create a composite measure that summarizes responses for multiple rank-ordered related questions or statements. In doing so, this composite measure gives the researcher data about a research participant's view on a certain belief, attitude, or experience.

For example, let’s say a researcher is interested in measuring job satisfaction and one of the key variables is job-related depression. This might be difficult to measure with simply one question. Instead, the researcher can create several different questions that deal with job-related depression and create an index of the included variables. To do this, one could use four questions to measure job-related depression, each with the response choices of "yes" or "no":

- "When I think about myself and my job, I feel downhearted and blue."

- "When I’m at work, I often get tired for no reason."

- "When I’m at work, I often find myself restless and can’t keep still."

- "When at work, I am more irritable than usual."

To create an index of job-related depression, the researcher would simply add up the number of "yes" responses for the four questions above. For example, if a respondent answered "yes" to three of the four questions, his or her index score would be three, meaning that job-related depression is high. If a respondent answered no to all four questions, his or her job-related depression score would be 0, indicating that he or she is not depressed in relation to work.

Scales in Research

A scale is a type of composite measure that is composed of several items that have a logical or empirical structure among them. In other words, scales take advantage of differences in intensity among the indicators of a variable. The most commonly used scale is the Likert scale , which contains response categories such as "strongly agree," "agree," "disagree," and "strongly disagree." Other scales used in social science research include the Thurstone scale, Guttman scale, Bogardus social distance scale, and the semantic differential scale.

For example, a researcher interested in measuring prejudice against women could use a Likert scale to do so. The researcher would first create a series of statements reflecting prejudiced ideas, each with the response categories of "strongly agree," "agree," "neither agree nor disagree," "disagree," and "strongly disagree." One of the items might be "women shouldn’t be allowed to vote," while another might be "women can’t drive as well as men." We would then assign each of the response categories a score of 0 to 4 (0 for "strongly disagree," 1 for "disagree," 2 for "neither agree or disagree," etc.). The scores for each of the statements would then be added for each respondent to create an overall score of prejudice. If a respondent answered "strongly agree" to five statements expressing prejudiced ideas, his or her overall prejudice score would be 20, indicating a very high degree of prejudice against women.

Compare and Contrast

Scales and indexes have several similarities. First, they are both ordinal measures of variables. That is, they both rank-order the units of analysis in terms of specific variables. For example, a person’s score on either a scale or index of religiosity gives an indication of his or her religiosity relative to other people. Both scales and indexes are composite measures of variables, meaning that the measurements are based on more than one data item. For instance, a person’s IQ score is determined by his or her responses to many test questions, not simply one question.

Even though scales and indexes are similar in many ways, they also have several differences. First, they are constructed differently. An index is constructed simply by accumulating the scores assigned to individual items. For example, we might measure religiosity by adding up the number of religious events the respondent engages in during an average month.

A scale, on the other hand, is constructed by assigning scores to patterns of responses with the idea that some items suggest a weak degree of the variable while other items reflect stronger degrees of the variable. For example, if we are constructing a scale of political activism, we might score "running for office" higher than simply "voting in the last election." "Contributing money to a political campaign " and "working on a political campaign" would likely score in between. We would then add up the scores for each individual based on how many items they participated in and then assign them an overall score for the scale.

Updated by Nicki Lisa Cole, Ph.D.

- How to Construct an Index for Research

- Scales Used in Social Science Research

- An Overview of Qualitative Research Methods

- Cluster Analysis and How Its Used in Research

- What Is Participant Observation Research?

- Definition and Overview of Grounded Theory

- Pros and Cons of Secondary Data Analysis

- Social Surveys: Questionnaires, Interviews, and Telephone Polls

- Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

- Data Sources For Sociological Research

- A Review of Software Tools for Quantitative Data Analysis

- Constructing a Deductive Theory

- How to Conduct a Sociology Research Interview

- Ethical Considerations in Sociological Research

- The Study of Cultural Artifacts via Content Analysis

- Science Says You Should Leave the Period Out of Text Messages

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

- Searching Solutions

- Indexed Examples

Searching Solutions: Indexed Examples

- Keywords vs Indexed

- Boolean Searching

- Additional Search Options

- Non-Indexed Examples

- Using a Thesaurus

- Subject Searching

- The Search Log

Examples of Indexed Databases

Searching tips are available on this page for:

- BIOSIS Citation Index / CINHAL / Gale Academic File / OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson) / PsycINFO / PubMed

Please contact me if you would to know about other databases and I will add them.

- Biosis Citation Index This link opens in a new window Life sciences and biomedical research database covering pre-clinical and experimental research, methods and instrumentation, animal studies, and more.

Hosted by Web of Science, this database uses BIOSIS Indexers to apply at least one Major Concepts and Concept codes to each citation.

- Major Concepts: About 170 headings, citations may have multiple major concept

- Concept Codes: About 570 five digit code used to represent the biological concepts discussed in the source

A key additional search field is: Taxonomic data .

- CINAHL Complete This link opens in a new window Most comprehensive database of full-text for nursing & allied health journals from 1937 to present. Includes access to scholarly journal articles, dissertations, magazines, pamphlets, evidence-based care sheets, books, and research instruments.

In CINAHL, the thesaurus is called: CINAHL Headings . It is located in the upper navigation bar of our EBSCO hosting program.

- Enter at term in the search box

- Click on a term to view the hierarchy tree

- Use check boxes to add terms to your search

- Click the green search box at the far right of the page to start your search

Boolean Operators: AND, OR and NOT.

Truncation indicator: Asterisk (*), may be used inside parentheses (e.g., "amniotic flud*")

Notes. Related words and equivalent subjects are calculated by the CINAHL database. MEDLINE refers to the indexed subset in PubMed.

- MeSH - Medical Subject Headings PubMed Thesaurus

This National Library of Medicine database is indexed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (their thesaurus) which is updated annually. The full MeSH database is available online. PubMed automatically maps concepts entered into the search box onto MeSH ... sometimes more successfully than at other times. Author keywords are included in the database, but not mapped; [all fields], [ot], and [tw] are fields that will access author keywords

Searching tips

- Always check the Search Details box on the right side navigation bar to see how PubMed applied the Boolean terms and mapped the search concepts; You can delete unneeded terms and rearrange parentheses right in the Search Details box

- Turns off automatic term mapping for that phrase; Use sparingly

- A phrase that contains a stopword will not be found (will be stopped) - even if that phrase exists

- Only MeSH terms that exactly match the quoted phrase will be found

Advanced search

- Boolean operators: AND, OR, NOT

- Proximity indicators: None

- Advanced Search Builder: Includes additional searchable fields

- Stopwords: Yes - see: Stopwords

- History: Combine and manage search strategies

Gale Academic OneFile

This database does not have a separate online Thesaurus, so it is necessary to use the Subject Guide search to locate specific subject. To search by a subject is a two step process:

- Begin by entering a few letters of your search term, then click on the appropriate subject from the drop-down menu

- Select the main subject term or one of the subdivisions by clicking on it

Boolean Operators: AND, OR, NOT

NOTE: Only in the Subject Guide Search and the Publication Search will the auto-fill drop-down menu identify actual subjects and publications. Entering terms in the main search box provides terms others have tried.

OmniFile Full Text Mega

Hosted by EBSCO, the Thesaurus is in the upper right corner.

Search tips

- Phase searching

- Use related words: Uses keywords related to the search term

- Also search within the full text of the articles: Expands search to include article texts

- Apply equivalent subjects: Similar to "See aso" in other thesauri

- Field codes: Two letter terms; available from the drop-down menu

- Search History: Click to show or hide; Use to combine and manage search strategies

- PsycINFO This link opens in a new window Abstract and citation database of scholarly literature in psychological, social, behavioral, and health sciences. Includes journal articles, books, reports, theses, and dissertations from 1806 to present.

ProQuest hosts this database which is indexed using the 11th edition (2007) of the American Psychological Association's Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms® and includes the updated terms for 2015. The Thesaurus is available online under Advanced Search and can be used to locate and combine terms using Boolean operators. Additionally, by using Subject heading (all) - SU from the drop-down menu, Look up Subjects accesses individual terms from the Thesaurus.

- Boolean terms: AND, OR, NOT

- Proximity indicators: NEAR/#, n/# (number required); PRE, PRE/#, p/# (default of 4 words)

- Processing order: NEAR, PRE, AND, OR, NOT.

- Additional search options: EXACT, .e; Hyphen (-)

- Wildcards; Asterisk (*) used at the end or middle of a word; Question mark (?)

- << Previous: Indexed Databases

- Next: Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Jul 29, 2024 2:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/searching

- Peer Review System

- Production Service

- OA Publishing Platform

- Law Review System

- Why Scholastica?

- Customer Stories

- eBooks, Guides & More

- Schedule a demo

- Law Reviews

- Innovations In Academia

- New Features

Subscribe to receive posts by email

- Legal Scholarship

- Peer Review/Publishing

- I agree to the data use terms outlined in Scholastica's Privacy Policy Must agree to privacy policy.

Guide to academic journal indexing: Where, when, and how to get indexed

Researchers overwhelmingly rely on scholarly indexes to find vetted academic content online. So to develop and improve the reputation and discoverability of any journal, getting it added to trusted abstracting and indexing (A&I) databases is essential.

Most journal publishers and editors know this, but how to go about seeking inclusion in indexes isn’t always as clear.

Which indexes should you add your journal articles to? What are the indexing criteria you’ll need to fulfill? When should you apply for target indexes? In what order? And how can you keep improving your content discoverability once admitted to indexes?

In this blog post, we answer these common indexing questions and more, covering everything you need to know to initiate and keep building upon a successful journal indexing strategy. Feel free to use the section links below to skip ahead based on where you are in your indexing journey.

Getting started: Understanding academic journal indexes

Key journal index types to consider and the benefits of each, how to develop an indexing strategy for one or more titles, key journal indexing criteria, navigating the journal indexing application process, tips for optimizing your article indexing outcomes, putting it all together.

Before we get into the nitty gritty of indexing, let’s start with some basics. What are journal indexes? Or, more specifically, how are we defining journal indexes for the purposes of this blog post?

Per this Walden University Library guide :

“An index is a list of items pulled together for a purpose. Journal indexes (also called bibliographic indexes or bibliographic databases) are lists of journals, organized by discipline, subject, or type of publication.”

Of course, mainstream search engines like Google and Bing also index content, but they do not fit the definition of an academic journal index. So we won’t get into them here.

However, with that said, many scholars use mainstream search engines in their research and want to know that their articles will be discoverable from them. So don’t forget to prioritize search engine optimization (SEO) with scholarly indexing. We cover everything you need to know about journal SEO for mainstream and academic search engines in this blog post .

Now, on to the primary types of academic journal indexes to consider (per the definition above).

Before embarking on any journal indexing initiative, we recommend developing a target list of the indexes you’d like your journal or journals to be part of to get a bird’s-eye view of your ultimate goal. The more quality indexes you identify, the better, as inclusion in multiple indexes will help expand your articles’ reach and potential impacts while boosting the reputation of your journal(s).

From there, you can map out an indexing strategy based on your discovery goals and the specific criteria of the indexes you’re interested in ( more on how to do this later ). For example, Scopus requires journals to have a 2+ year publication history. So if you’re working with a new journal, you’ll logistically have to wait for at least two years before applying to that index, whereas; you’ll be able to seek inclusion in other indexes like Google Scholar sooner.

Below we outline the index types to consider and the benefits of each.

Scholarly search engines and aggregators

One of the best starting points for journal indexing is scholarly search engines and aggregators, many of which are freely available to researchers and the general public and often have less stringent inclusion criteria with regard to publication history, citation counts, and so forth.

The top academic search engine to focus on is Google Scholar , Google’s free crawler-based academic index. You can find our complete guide to Google Scholar indexing here . We also cover how to improve your chances of showing up higher in Google Scholar search results in our guide to journal SEO . You may have also heard of the Microsoft Academic search engine, but that was discontinued in December 2021.

Scholarly aggregator options with search functionality include Semantic Scholar , Dimensions , Lens , and CORE . Aggregators like these pull in content from other trusted academic databases, with the Crossref content registration agency being a prime source. So one of the best starting points for getting a new journal indexed is applying for Crossref membership and registering Digital Object Identifiers or DOIs for all the articles you publish. We cover how to apply for DOIs here and how to leverage the discovery benefits of Crossref in this webinar .

Registering DOIs for all articles is among the most common indexing application requirements, as discussed below. So it’s a good idea to apply for DOIs early on for new journals.

General scholarly archiving and indexing databases

In addition to getting indexed in scholarly search engines and aggregators, you’ll obviously want to seek inclusion in dedicated academic indexing databases, also known as abstracting and indexing databases or A&Is. You can apply to add your journal(s) to indexing databases that cover multiple disciplines as well as discipline-specific or “specialized” A&Is.

Many aggregators also ingest content directly from partner A&Is or require journals to be admitted to specific A&Is before being eligible to be included in their search results as a means of quality control, so applying to A&Is can help your articles appear in aggregator search results as well. For example, Semantic Scholar only indexes journals already in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), and the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) free scholarly search engine PubMed pulls in all of its content from the NIH’s archiving and indexing databases MEDLINE and PubMed Central (PMC). So to be included in PubMed search, journals must be accepted to one of those databases first. You can learn more about the relationship between the NIH’s databases and how to apply to PMC and/or MEDLINE to be added to PubMed Search in this blog post .

There will be myriad indexing options for every journal, ranging from government and institutional indexes to commercial indexes run by publishers and data analytics companies. We obviously can’t cover every possible index in this blog post. But we’ve done our best to compile a list of some of the most widely-used and reputable general scholarly A&Is below (we cover top discipline-specific A&Is in the next section):

- The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ): The DOAJ is a non-profit community-curated online directory of peer-reviewed open-access journals. If you’re jumpstarting indexing for a new OA journal, we recommend beginning with the DOAJ because it’s a trusted OA index that various scholarly aggregators use as a data source. We compiled a complete guide to DOAJ indexing here . The DOAJ is a free-access index.

- Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory : Ulrich’s is a leading library directory and database with information about academic journals and serial publications around the world that is part of Clarivate. Ulrich’s is a subscription-access index.

- Scopus : Scopus is Elsevier’s abstract and citation database. It covers over 36,000 titles, spanning the life sciences, social sciences, physical sciences, and health sciences. You can read our guide to Scopus indexing here and a case study with the editors of Precision Nanomedicine , a Scholastica customer, about their experience getting indexed in Scopus here . Scopus is a subscription-access index.

- Web of Science : WoS is Clarivate’s abstract and citation database. Its Core Collection encompasses six citation indexes in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities and collectively contains more than a billion searchable citations spanning over 250 disciplines. We compiled a complete guide to WoS indexing here . WoS is a subscription-access index.

- EBSCO Information Services : EBSCO is a commercial index and aggregator that includes titles compiled by the company and journals from other databases, such as MEDLINE . EBSCO is a subscription-access index.

- JSTOR : JSTOR is a digital library database that covers over 12 million journal articles, books, images, and primary sources in 75 disciplines. They are best known for hosting digitized content from journal back files, books, and other resources. They now publish journals willing to host articles solely on the JSTOR platform.

- SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) : SciELO is a bibliographic database, digital library, and cooperative electronic publishing model for OA journals created to support the publication and increase the visibility of OA research in developing countries. SciELO is a free-access index.

- Cabell’s : This last one is a little different. Rather than being an index readers use to find content, Cabell’s is a directory researchers use to determine which journals will be the best fit to publish in. Of course, attracting more high-quality submissions can also help journals expand their impact and reach, so it’s a good idea to pursue Cabell’s indexing. Cabell’s is a subscription-access index.

Discipline-specific or “specialized” indexes and search engines

Of course, the discipline-specific indexes you choose to apply to will depend on the subject area(s) your journals cover. If you’re unsure which indexes are the most widely used in a given journal’s discipline or across interdisciplinary areas, start to ask around. Query your authors, editors, reviewers, and readers to learn which discipline-specific databases they use.

There are many discipline-specific databases out there to look into. And some broader databases contain discipline-specific segments. For example, the Web of Science Core Collection includes the Science Citation Index Expanded , Social Sciences Citation Index , and Arts & Humanities Citation Index .

Other top discipline-specific or “specialized” indexes include the ones listed below.

STEM journals:

- PubMed Central (PMC): PMC is a digital repository that archives OA full-text articles published in biomedical and life sciences journals. PMC is a free-access index with search functionality. PubMed aggregates articles from PMC. So Applying to PMC is the fastest way to be included in PubMed Search, as explained in this guide .

- MEDLINE : This is the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) bibliographic database of life sciences and biomedical research. MEDLINE is a free-access index searchable via PubMed.

- PsycInfo : PsycInfo is the American Psychological Association’s abstracting and indexing database, with over three million records of peer-reviewed literature in the behavioral sciences and mental health fields. PsycInfo is a subscription-access index.

- MathSciNet : MathSciNet is the American Mathematical Society’s searchable online bibliographic database containing over three million records of peer-reviewed literature. It is a subscription-access index.

Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) journals:

- Project MUSE : MUSE is an index of humanities and social sciences content, including journals, which only indexes content published by a not-for-profit press or scholarly society.

- MLA Directory of Periodicals : This is a searchable list of publication information about the journals included in the MLA International Bibliography.

- EconLit : The American Economic Association’s A&I focused on literature in the field of economics.

For more journal indexing options, check out Wikipedia’s list here and Nature’s list of indexes that their journals are part of here . The University of Miami Library also has a comprehensive list of indexes here .

Pro Tip: As a rule of thumb, if your journal is an OA publication, it’s a good idea to make getting added to the DOAJ a priority. The DOAJ is one of the top general indexing databases in terms of use and reputability that journals can usually apply for relatively early in their publication life. With over 12,000 journal members, over 1.2 million visitors a month, and a continually updating stream of journal metadata ingested by leading discovery services across disciplines, the DOAJ is a powerful platform for journal awareness.

Once you know the indexes you want to pursue, it’s time to map out your indexing strategy. Indexes will have varying levels of inclusion criteria (e.g., publication and technical standards journals must fulfill), so it’s a good idea to make a gradual indexing plan. Start with low-hanging fruit indexes that you can have your journal(s) added to early on, and then build up to more selective cross-discipline and discipline-specific/“specialized” scholarly databases such as Scopus and MEDLINE.

Of course, the more highly vetted an index is, the more trustworthy it will be to scholars. So journals should keep working to apply to more stringent databases as they mature and become eligible. Don’t just stop at a few!

When weighing your indexing options, consider the level of article discovery benefits different indexes will offer. For example, some databases only index article titles, abstracts, and/or references. Whereas some index entire article files. Generally, indexes that ingest more article details or the full text will be better for expanding content discoverability since they’ll have more information to go off of when deciding if and when to show your articles in search results. They also offer a more direct search experience for researchers.

As seen in the previous section, indexes also offer different levels of accessibility, with some being freely available to anyone interested in searching them, like Google Scholar and PubMed search, and others requiring a subscription, like Scopus and Web of Science. For open access (OA) journals especially, ensuring articles are easy to find via free online indexes, not just subscription databases, is paramount to maximizing content accessibility.

Pro Tip: When developing your indexing strategy, don’t forget to account for application review timelines. While some indexes review journals on a rolling basis, others only review applications at certain times throughout the year. So that will also factor into when you’ll be eligible for different indexes.

As you’re considering possible indexes to apply to, you’ll obviously want to start by visiting their application requirements pages and reading them thoroughly. Doing a quick Google search for “[index name] application criteria” or “how to get indexed in [index name]” will usually get you there. If you’re having trouble finding an index’s application criteria, you can also always visit their help/contact page to find a support email to write to for guidance.

Now, onto indexing application criteria journals should fulfill.

As noted, reputable scholarly search engines, aggregators, and A&Is have admittance standards and often require journals to undergo an application process before being eligible for inclusion.

Here, we cover the most common indexing application criteria moving from basics to more stringent requirements. These are all publishing best practices, so you should aim to fulfill them regardless of which indexes you decide to pursue.

Publication standards

Starting with publication standards (e.g., journal details, editorial policies, etc.), in good news, many requirements will essentially be the same across scholarly indexes. Some of the most common publication criteria include that all journals should have:

- An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN)

- Digital Object Identifiers or DOIs for all articles ( Crossref is the leading DOI registration agency for journals)

- A dedicated editorial board page with the names, titles, and institutional affiliations of all editors

- Clearly stated peer review policies , including an overview of the journal’s peer review process (e.g., type, stages of review) and statements on publication ethics

- An established publishing schedule (e.g., bi-monthly, rolling)

- An established copyright policy (e.g., CC BY for fully OA journals)

From there, indexes may have more specific additional guidelines. For example, some indexes require journals, particularly those that publish online only, to show that their articles are being added to an archive (this is also a general best practice !). Other specific indexing requirements may include guidelines around:

- Publication scope: While many indexes accept journals in all disciplines or within a broad set of disciplinary areas, such as the humanities and social sciences, some only accept journals that publish within a particular subject area.

- Minimum publication history: Some indexes require publishers and/or journals to be around for a minimum amount of time before applying. For example, MEDLINE only accepts applications from organizations that have published scholarly content for two years or more.

- Level of publishing professionalization: Some indexes also look at the readability of published articles (e.g., level of editing) and production quality.

- Geographic diversity: Some indexes look to see that journals have geographically diverse editorial boards and authors.

- Adequate citations: Some indexes will not accept journals until they meet a certain citation-level threshold to demonstrate impact.

Technical requirements

In addition to publication standards like those outlined above, many scholarly search engines, aggregators, and indexes require or encourage journals to meet specific technical criteria for content ingestion.

First, it’s helpful to understand the three main ways scholarly search engines, aggregators, and A&Is ingest content:

- Web crawlers: Some scholarly search engines like Google Scholar index journal articles via web crawlers or bots that systematically scan websites for content. For crawlers to be able to find and index articles, publishers must apply machine-readable metadata to all article pages via HTML meta tags and maintain a website structure that complies with the search engine’s requirements. For example, Google Scholar will only index articles hosted on their own webpage with HTML meta tags. You can learn more about Google Scholar’s technical inclusion criteria here .

- Metadata/content deposits: Many indexes do not have web crawlers and instead require content deposits. In this case, publishers must submit article-level metadata and/or full-text article files to the index. Some indexes have forms for making manual metadata deposits. However, many require journals to directly deposit machine-readable metadata and/or full-text article files into the index via an FTP server or API integration. Making machine-readable metadata/article deposits is also a best practice because machine-readable metadata files are generally richer, more uniform, and less prone to inaccuracies than metadata input manually. JATS XML is the standard machine-readable format for journal metadata/article files. JATS, which was developed by the National Information Standards Organization (NISO), stands for Journal Article Tag Suite.

- Cascading metadata: As noted above, some scholarly aggregators automatically ingest content from other trusted academic databases such as the Crossref content registration service and DOAJ index.

At a minimum, journals should aim to produce front-matter JATS XML article-level metadata files that include:

- Journal publisher

- Journal issue details (e.g., publication date and volume/issue number)

- Journal title

- Article title

- Author names

- Copyright license

- Persistent Identifiers or PIDs (e.g., Digital Object Identifier, ORCID iD, ROR ID)

Once journals have the above core metadata fields, they can work to continue enriching their metadata outputs. We cover five elements of “richer” metadata to prioritize in this blog post .

Some databases also require full-text XML article files like PMC, which has specific JATS XML formatting guidelines.

We cover JATS XML 101 in this blog post and the what, why, and how of producing JATS XML in this webinar .

Producing XML in the JATS standard can get quite technical, but thankfully, there are software and services that can help. For example, Scholastica’s digital-first production service generates full-text JATS XML articles with rich metadata, and our fully-OA journal publishing platform features JATS XML metadata on all article pages.

From publication standards to technical requirements, most indexing criteria will be straightforward in nature. But fulfilling them will require a high level of attention to detail. That’s why, in all of your indexing endeavors, it’s so so so important to take your time!

Read indexing applications carefully, then re-read them again — we can’t emphasize this enough. And if you’re already in one index, don’t assume the criteria will be the same for the others. You’ll need to account for variables, big and small.

Also, if you have to update or add information to your journal website to fulfill indexing criteria, be sure to do so in all relevant places and to make required indexing information as specific and explicit as possible. For example, you don’t want your DOAJ application denied because you have missing or inconsistent copyright information on one of your website pages. (Yes, one page can make or break an application!).

Of course, it’s not the end of the world if an index denies your application! All indexes will allow you to reapply. But many require a waiting period for re-application (e.g., the DOAJ has a 6-month wait), so it pays to take some extra time to get your application right on the first round.

If you’re unsure whether one of your journals meets the criteria for a particular database, you can visit their website or contact their support staff to find out what you need to do to be eligible. Another great indexing resource is university libraries. Reach out to scholarly communication or subject-specific librarians to find out what they recommend. Many libraries are well-versed in helping journals get indexed.

A good indexing strategy extends beyond your initial application. Once admitted to indexes, adhering to the highest technical standards is critical to maximizing their discovery benefits.

Start by focusing on producing and enriching machine-readable article-level metadata to have more article details to send to indexes. That means including descriptive HTML meta tags on article website pages for crawler-based search engines and producing rich machine-readable metadata files for deposit-based A&Is. As noted, the machine-readable format standard for academic journals is JATS XML. JATS is preferred or required by many academic indexes, including all National Library of Medicine indexes (i.e., PubMed, PubMed Central, and MEDLINE).

For deposit-based indexes, it’s also important not to lose sight that content won’t be discoverable from those channels until it’s added. So the sooner you can make metadata/article file deposits for new or updated articles, the better. Ideally, you should automate index deposits where possible. Journal publishing platforms can help you here. For example, Scholastica’s OA publishing platform includes integrations with leading discovery services, including Crossref, the DOAJ, and PubMed.

As you can see from this blog post, journal indexing is a process — and it will take time . But it’s well worth the effort to seek inclusion in various relevant indexes and to work to optimize your indexing outcomes. Adding journals to indexes helps expand their reach, reputation, and, consequently, their impacts.

We hope you’ve found this guide helpful! You can learn more about how Scholastica is helping journal publishers automate indexing steps here and how we’re helping journals produce machine-readable metadata to make articles more discoverable here .

Update note: This blog post was originally published on the 21st of June 2017 and updated on the 13th of April 2023.

Related Posts

Are stakeholders measuring the publishing metrics that matter?: Putting research into context

What steps can the scholarly community take to reform research evaluation and move away from relying too heavily on finite metrics that could skew the results? A recent NISO webinar series explored this question.

The biggest opportunities society and university press journal publishers see in 2023: Part 3

Leaders at university presses and scholarly societies publishing research across disciplines discuss the biggest opportunities they see for independent academic publishers to further their journal programs in 2023 and beyond.

Steps journals can take to support authors living with disabilities: Interview with Tekla Babyak

In this interview, Independent Musicologist and Disability Activist Tekla Babyak (Ph.D., Musicology, Cornell, 2014) discusses her experience as an academic living with MS and shares steps scholarly journal publishers and editors can take to better support authors with disabilities.

How to Start an Open Access Journal: 2024 Small Publisher Primer

Are you working with a scholarly society or institution starting an Open Access journal or thinking about transitioning one or more titles to a fully OA publishing model and wondering where to begin? In this blog post, we break down how to determine the best OA publishing route for your organization and get your efforts off the ground.

Behind the scenes of Scholastica's digital-first production service

In this post, we go behind the scenes of Scholastica's digital-first production service, which takes the legwork out of formatting articles by using advanced software to generate PDF, HTML, and full-text XML article files simultaneously.

Improving journal metadata outputs, from basics to semantics: Interview with Jabin White

Jabin White, Vice President of Content Management for JSTOR and Portico, shares his thoughts on how metadata quality can be improved across academia, and how publishers can move from basic metadata concepts to creating enhanced metadata.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Journal Indexing and the Types of Journal Indexing in Research

Just as an index is a list of items put together for a specific purpose, journal indexing is the process of listing journals, organized by discipline, type of publication, region, etc. Journal indexes are also known as bibliographic or citation indexes. The online discovery of research articles relies heavily on journal indexing . And so, researchers and journals alike must know the types of journal indexing to get the best out of it.

Table of Contents

What is journal indexing and how does it work?

Journal indexing in research serves as a guide for relevant scholarly content and seeks to make the information widely available and easy to access. It can function as an information retrieval tool for libraries and archives. Journal indexing allows users to familiarize themselves with an article and decide if they want to read it further.

The process of inclusion in a journal index involves scrutiny and assessment to ensure that a journal meets basic scholarly publishing standards. A journal applies to a relevant journal indexing service, requesting its integration in their database. The journal indexing service will follow a thorough vetting process for industry standards, some of which are as follows:

- Scope of the journal (especially if the index is subject specific)

- Registration of its International Standard Serial Number (ISSN)

- Commitment to a publishing schedule

- Provision of transparent Editorial Board information

- Provision of information on peer review, copyrights, ethics, etc.

- Digital object identifiers (DOIs)

- Basic article-level metadata (persistent identifiers, copyright licenses, open abstracts, etc.).

Once the evaluation is complete and the journal is indexed by a database, it becomes available to the users of that journal indexing database .

Types of index ing in journals

There are many rich options for researchers to tap into during their literature search. To understand these options better, let’s take a look at the types of indexing in journals and how journal indexing databases can be classified.

Specificity

Broad or general indexes are, as the name indicates, broad in scope and coverage. Examples of such indexing databases in research are Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Scopus, and Web of Science.

Free search engines like Google Scholar also fall in this category. Google Scholar indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across the breadth of disciplines and publishing formats. This is where a researcher typically launches preliminary searches before a deep dive into specialized indexes.

Specialized indexes are indexes specific to certain fields or subject areas. Examples of specialized indexes are Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), which includes mainly science and technology journals; PubMed, which contains mostly biomedical journals; and Arts & Humanities Citation Index, which includes mostly arts and humanities journals.

Geographical coverage

While indexes like Web of Science include journals from many countries, some are specific to a country or region, e.g., Korean Citation Index.

Many journal indexing databases are free and open to the public (e.g., Web of Science Master Journal List), while some are subscription based. Journals in subscription-based indexes are generally considered higher in status, perhaps because of the stronger assessment for inclusion in such journal indexing databases . However, their access would be limited to subscribers only.

What is indexed

Different indexes even provide different levels of “discovery potential.” Some databases index article titles, abstracts, and references, whereas some index the full article. It is obvious that journal indexes offering more article information or full text will have a higher potential for discovery.

Journal indexing and the importance of indexing in research

Now that it is clear that there are so many indexing databases in research to choose from, how can users maximize their benefits?

For researchers: at the literature search stage

Researchers can search a list of journal indexing databases to find studies on specific topics. You can search for specific journals and even browse by subject or database. Journal indexes also help you save time because they simplify the search for relevant information.

For researchers: at the journal selection stage

As an author, publishing in an indexed journal increases the visibility and credibility of your work. Most institutions and funders require publications to appear in indexed journals. Many high-quality and high-impact journals are indexed in multiple databases. If you want to know where all your target journal is indexed, go to the “About the journal” section on a journal’s website. You might find an “Abstracting & Indexing” tab, under which you can view a list of journal indexing databases the journal appears in.

For journals/publishers

Being indexed in several well-known bibliographic databases points to the quality of a journal. Moreover, journal indexing makes a journal accessible to a wide audience. This increases its visibility and translates into better reach and impact of the journal, which boosts its reputation and sets the ball rolling for an even wider readership. Journals can also benefit from being added to general search engines, besides scholarly databases, to make their articles highly discoverable.

Concluding notes

Indexed journals are reliable sources of high-quality research. They can be used for efficient literature searches. Further, when choosing where to publish, authors should prioritize journals that are indexed in several general and specialized indexes to improve the visibility and impact of their work.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is IMRaD Format in Research?

What is a Review Article? How to Write it?

Tag: index terms

From the deck of… ala midwinter 2018.

Welcome to “From the Deck of . . .” an irregular series in which we highlight search demos and other information from the slide decks we create for our live training sessions. You can view and download these materials from the PsycINFO SlideShare account .

At the recent American Library Association Midwinter conference, APA hosted a Lunch & Learn training session, which covered searchable vocabularies in PsycINFO®.

- Keywords are searched using natural language, and are good for current research and new concepts.

- Index Terms (also called Subject Headings) are found in the thesaurus tool, and help the focused researcher quickly find all records about a concept.

- PsycINFO Classification Codes ® describe broad areas of psychology, and are good to pair with a keyword or an index term search.

- MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings, are assigned by National Library of Medicine, and are good for searching neuroscience and health topics, especially for researchers familiar with PubMed.

In Case You Missed It – Searching By Keyword, Index Term, and More

In January of 2017, we posted about searching APA PsycInfo® by different vocabularies – keywords, index terms, classification codes, and MeSH.

In case you missed it, start the new semester off with a better understanding of which vocabulary will suit your needs.

Keywords (also called Key Concepts or Identifiers) – individual words, key concepts, or brief phrases that describe the document’s content; usually provided by the author or publisher.

Good for researchers who are new to a topic.

Index Terms (also called Subjects or Subject Headings) – are chosen by APA staff from Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms ® .

Good for the focused researcher.

Classification Codes (also called APA PsycInfo Classifications) – a descriptive term plus a corresponding numerical code; like the index terms, there is a pre-existing list, or controlled vocabulary.

Good to pair with keywords or index terms.

MeSH – Medical Subject Headings are a controlled vocabulary maintained by the National Library of Medicine for their PubMed database.

Good for medical or neuroscience topics.

To learn more about any of these search vocabularies, review our post on them from January 2017 .

Related Resources:

APA PsycInfo Expert Tip – Searching by Keywords Across Platforms

APA PsycInfo Expert Tip – Classification Codes

Tutorial – Using APA PsycInfo Classification Codes on EBSCOhost

APA PsycInfo Expert Tip: Searching by Keyword, Index Term and More

Have you ever wondered what the difference is between a keyword and an index term, and how they can aid your search? What are classification codes, and how does this all relate to MeSH terms? This post will demystify the four types of vocabulary you see in APA PsycInfo®.

Keywords (also called Key Concepts or Identifiers) – Individual words, key concepts, or brief phrases that describe the document’s content. The list of keywords for an article is often provided by the author or publisher, though sometimes it is created by APA staff. There is no pre-existing list of keywords that authors, publishers, or APA staff choose from.

Keyword searching is a good fit for researchers who are new to a topic, and want to get the full scope of what is available. Keyword searching is most similar to the searching you may do on the internet, because keywords are often in natural language or layman’s terms. In addition, you do not need to select or know terms from a pre-existing list, as you do for the following three types of vocabulary.

Index Terms (also called Subjects or Subject Headings) – Index terms are also single words or brief phrases that describe the document’s content, but they are chosen from a pre-existing list (also called a controlled vocabulary). For the APA databases, that list is the Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms ®, which includes more than 8,400 terms. APA staff typically choose about six index terms for each document. You can use the thesaurus tool, linked from the APA PsycInfo search page, to search or browse index terms alphabetically or by topic.

Index term searching is a good fit for the focused researcher, who has identified their best term(s) and now wants to quickly find all of the items about a particular concept. With the wide variety of concepts and vocabulary used in the psychological literature, searching for and retrieving records about specific concepts is virtually impossible without the controlled vocabulary of a thesaurus. It provides a way of structuring the subject matter in a way that is consistent among users (e.g., searching for Dysphoria, Melancholia, and Depression can all be achieved by searching the term “Major Depression”).

Continue reading →

What is an index and do you need one?

Want to know former US president Bill Clinton’s thoughts on the Watergate scandal? The 1993 World Trade Center bombing? Monica Lewinsky? There’s no need to read all 957 pages of his autobiography, My Life . Simply flick to the back of the book and check the index for the page number.

An index is a list of all the names, subjects and ideas in a piece of written work, designed to help readers quickly find where they are discussed in the text. Usually found at the end of the text, an index doesn’t just list the content (that’s what a table of contents is for), it analyses it.

Where are indexes used?

In addition to back-of-the-book indexes found in non-fiction books and technical reports, indexes are also used to make other sources of information – including journal articles, maps and atlases, art collections, online databases and websites – easier to navigate. Where books are published online, in PDF or e-book format, indexes link directly to points in the text.

Indexes are a common inclusion in many annual reports and are mandatory for annual reports produced by Australian Government departments, executive agencies and other non-corporate Commonwealth agencies.

What makes a good index?

An index provides a map to a report’s content. It does this through identifying key themes and ideas, grouping similar concepts, cross-referencing information and using clear formatting. A good index will:

- be arranged in alphabetical order

- include accurate page references that lead to useful information on a topic

- avoid listing every use of a word reor phrase

- be consistent across similar topics

- use sub-categories to break up long blocks of page numbers

- use italics for publications and Acts

- cross-reference information to point to other headings of interest or preferred terms.

For example, a back-of-the-book index might read:

sales, sales process, 147, 149, 158, see also strategy (directs the reader to a related term)

scripts, 56–59 (grouping term)

podcasts, 56–57 (sub-term)

video, 58–59

search engine optimisation, 100, 156

Security Analysis (David Dodd and Benjamin Graham), 89–90 (reference to a book)

spelling, see proofreading (directs the reader to the word or phrase used in the text)

While software is available to help indexers arrange, format and edit entries, indexers will also use their judgement when deciding what to put into an index, what to leave out and how to organise it.

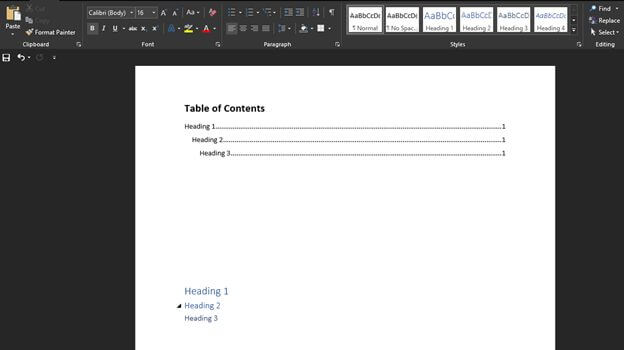

Don’t forget to add a table of contents

A good index may be the difference between people referring to a report regularly and it gathering dust on the bookshelf. If you don’t have an index, it’s important to at least have a good table of contents.

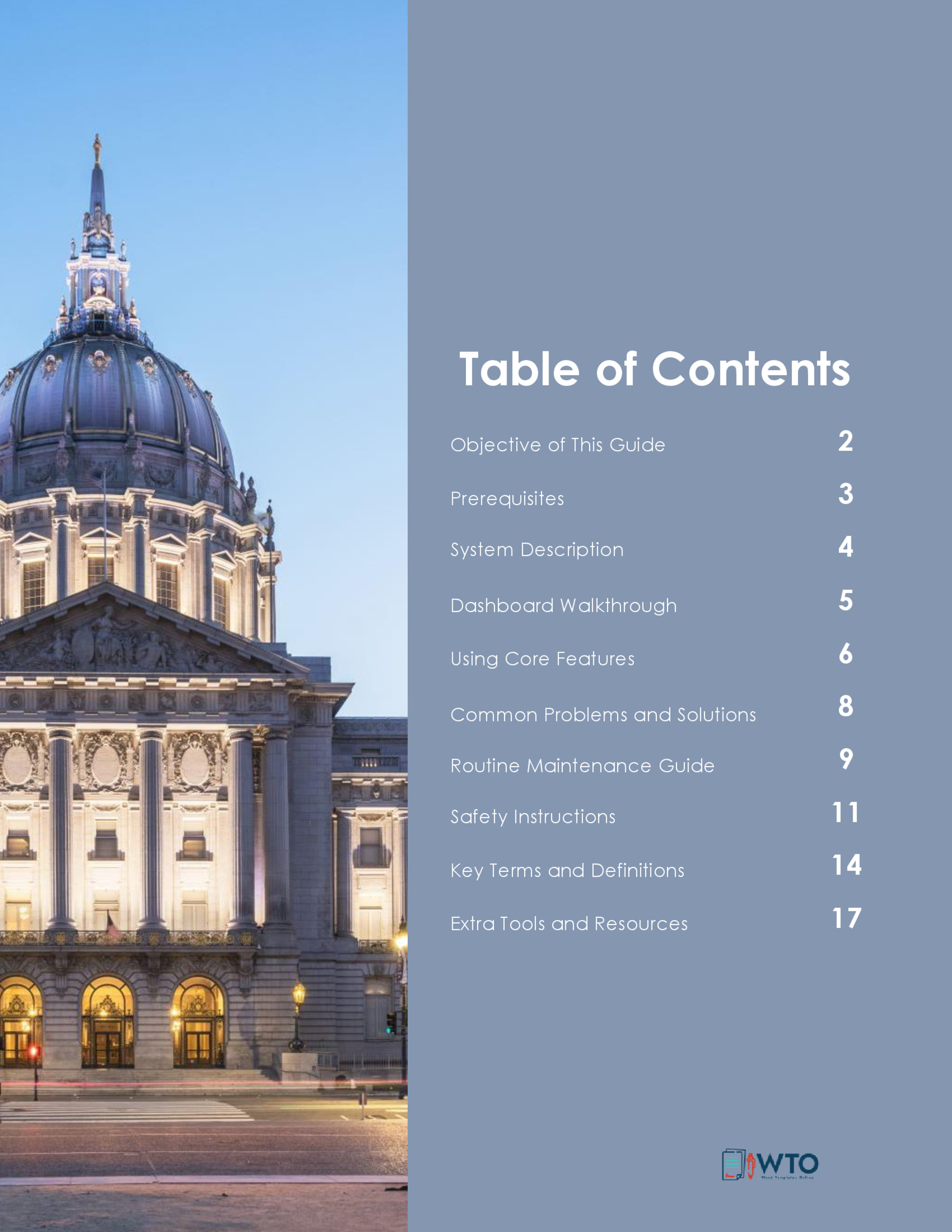

Located at the front of a report, a table of contents allows readers to easily see what the report is about and how sections of the text are arranged, in the order they appear.

A good table of contents will include headings, outlining the main sections or themes; sub-headings that indicate what each section of copy is about; and the page numbers they appear on. Additional content such as tables and boxes can also be added.

Want to make your report as easy to navigate as possible? Bookend it with a table of contents and an index – readers will have no excuse for not being able to find the information they’re after.

We can help create a roadmap for your reports, books and other larger documents. Learn more about indexing or contact us here .

How to create an award-winning annual report

More Insights

That’s a wrap: celebrating the sydney writers’ festival 2024, why clear, concise brochure writing is still vital for marketing success, how to write effective generative ai prompts: a guide for aspiring ai whisperers, what is subject–verb agreement a simple guide to getting it right.

The right words to help you grow sales, deliver messages and meet your compliance needs.

Australia / Singapore / USA

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Research Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Research Paper

There will come a time in most students' careers when they are assigned a research paper. Such an assignment often creates a great deal of unneeded anxiety in the student, which may result in procrastination and a feeling of confusion and inadequacy. This anxiety frequently stems from the fact that many students are unfamiliar and inexperienced with this genre of writing. Never fear—inexperience and unfamiliarity are situations you can change through practice! Writing a research paper is an essential aspect of academics and should not be avoided on account of one's anxiety. In fact, the process of writing a research paper can be one of the more rewarding experiences one may encounter in academics. What is more, many students will continue to do research throughout their careers, which is one of the reasons this topic is so important.

Becoming an experienced researcher and writer in any field or discipline takes a great deal of practice. There are few individuals for whom this process comes naturally. Remember, even the most seasoned academic veterans have had to learn how to write a research paper at some point in their career. Therefore, with diligence, organization, practice, a willingness to learn (and to make mistakes!), and, perhaps most important of all, patience, students will find that they can achieve great things through their research and writing.

The pages in this section cover the following topic areas related to the process of writing a research paper:

- Genre - This section will provide an overview for understanding the difference between an analytical and argumentative research paper.

- Choosing a Topic - This section will guide the student through the process of choosing topics, whether the topic be one that is assigned or one that the student chooses themselves.

- Identifying an Audience - This section will help the student understand the often times confusing topic of audience by offering some basic guidelines for the process.

- Where Do I Begin - This section concludes the handout by offering several links to resources at Purdue, and also provides an overview of the final stages of writing a research paper.

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts