Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

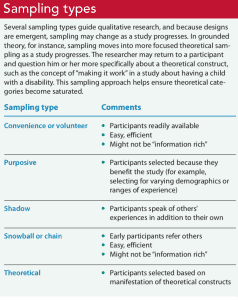

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

| Action research | Education | Conducted by and for those taking action to improve or refine actions | What happens to the quality of nursing practice when we implement a peer-mentoring system? |

| Case study | Many | In-depth analysis of an entity or group of entities (case) | How is patient autonomy promoted by a unit? |

| Descriptive | N/A | Content analysis of data | |

| Discourse analysis | Many | In-depth analysis of written, vocal, or sign language | What discourses are used in nursing practice and how do they shape practice? |

| Ethnography | Anthropology | In-depth analysis of a culture | How does Filipino culture influence childbirth experiences? |

| Ethology | Psychology | Biology of human behavior and events | What are the immediate underlying psychological and environmental causes of incivility in nursing? |

| Grounded theory | Sociology | Social processes within a social setting | How does the basic social process of role transition happen within the context of advanced practice nursing transitions? |

| Historical research | History | Past behaviors, events, conditions | When did nurses become researchers? |

| Narrative inquiry | Many | Story as the object of inquiry | How does one live with a diagnosis of scleroderma? |

| Phenomenology | Philosophy Psychology | Lived experiences | What is the lived experience of nurses who were admitted as patients on their home practice unit? |

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

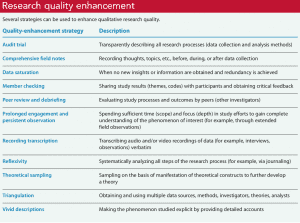

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

| o What is the report title and composition of the abstract? o What is the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and study significance? o What is the purpose of the study and/or research question? | → Clear and concise report title describes the research topic and design (e.g., grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interviews) → Abstract summarizes key points including background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions → Problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance is identified and well described, with a thorough review of relevant theories and/or other research → Study purpose and/or research question is identified and appropriate to the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance |

| o What design and/or research paradigm was used? o Is there evidence of researcher reflexivity? o What is the setting and context for the study? o What is the sampling approach? How and why were data selected? Why was sampling stopped? o Was institutional review board (IRB) approval obtained and were other issues relating to protection of human subjects outlined? | → Design (e.g., phenomenology, ethnography), research paradigm (e.g., constructivist), and guiding theory or model, as appropriate, are identified, along with well-described rationales → Design is appropriate to research problem and/or phenomenon of interest → Researcher characteristics that may influence the study are identified and well described, as well as methods to protect against these influences (e.g., journaling, bracketing) → Settings, sites, and contexts are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales |

| o What data collection and analysis instruments and/or technologies were used? o What is the method for data processing and analysis? o What is the composition of the data? o What strategies were used to enhance quality and trustworthiness? | → Sampling approach and how and why data were selected are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales; participant inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined and appropriate → Criteria for deciding when sampling stops is outlined (e.g., saturation) and rationale is provided and appropriate → Documentation of IRB approval or explanation of lack thereof provided; consent, confidentiality, data security, and other protection of human subject issues are well described and thorough → Description of instruments (e.g., interview scripts, observation logs) and technologies (e.g., audio-recorders) used is provided, including how instruments were developed; description of if and how these changed during the study is given, along with well-described rationales → Types of data collected, details of data collection, analysis, and other processing procedures are well described and thorough, along with well-described rationales → Number and characteristics of participants and/or other data are described and appropriate → Strategies to enhance quality and trustworthiness (e.g., member checking) are identified, comprehensive, and appropriate, along with well-described rationales; trustworthiness framework, if identified, is established from experts (e.g., Lincoln and Guba, Whittemore et al.) and strategies are appropriate to this framework |

| o Were main study results synthesized and interpreted? If applicable, were they developed into a theory or integrated with prior research? o Were results linked to empirical data? | → Main results (e.g., themes) are presented and well described and a theory or model is developed and described, if applicable; results are integrated with prior research → Adequate evidence (e.g., direct quotes from interviews, field notes) is provided to support main study results |

| o Are study results described in relation to prior work? o Are study implications, applicability, and contributions to nursing identified? o Are study limitations outlined? | → Concise summary of main results are provided and thorough, including relation to prior works (e.g., connection, support, elaboration, challenging prior conclusions) → Thorough discussion of study implications, applicability, and unique contributions to nursing is provided → Study limitations are described thoroughly and future improvements and/or research topics are suggested |

| o Are potential or perceived conflicts of interest identified and how were these managed? o If applicable, what sources of funding or other support did the study receive? | → All potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and well described; methods to manage potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and appear to protect study integrity → All sources of funding and other support are identified and well described, along with the roles the funders and support played in study efforts; they do not appear to interfere with study integrity |

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Emotional intelligence: A neglected nursing competency

Hypnosis and pain

Measuring nurses’ health

From Retirement to Preferment: Crafting Your Next Chapter

Leadership in changing times

Promoting health literacy

Mentorship: A strategy for nursing retention

States Set Minimum Staffing Levels for Nursing Homes. Residents Suffer When Rules Are Ignored or Waived

Anatomy of Writing for Publication for Nurses: The writing guide you’ve been looking for

Nurse leadership: Pitfalls and solutions

Home health nursing

Navigating the crossroads of nursing faculty practice

Does money matter?

It’s time embrace AI in nursing

CMS establishes minimum LTC staffing standards

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 15, Issue 1

- Qualitative data analysis

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Correspondence to Kate Seers RCN Research Institute, School of Health & Social Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, Warwick, UK; kate.seers{at}warwick.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs.2011.100352

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Good qualitative research uses a systematic and rigorous approach that aims to answer questions concerned with what something is like (such as a patient experience), what people think or feel about something that has happened, and it may address why something has happened as it has. Qualitative data often takes the form of words or text and can include images.

Qualitative research covers a very broad range of philosophical underpinnings and methodological approaches. Each has its own particular way of approaching all stages of the research process, including analysis, and has its own terms and techniques, but there are some common threads that run across most of these approaches. This Research Made Simple piece will focus on some of these common threads in the analysis of qualitative research.

So you have collected all your qualitative data – you may have a pile of interview transcripts, field-notes, documents and notes from observation. The process of analysis is described by Richards and Morse 1 as one of transformation and interpretation.

It is easy to be overwhelmed by the volume of data – novice qualitative researchers are sometimes told not to worry and the themes will emerge from the data. This suggests some sort of epiphany, (which is how it happens sometimes!) but generally it comes from detailed work and reflection on the data and what it is telling you. There is sometimes a fine line between being immersed in the data and drowning in it!

A first step is to sort and organise the data, by coding it in some way. For example, you could read through a transcript, and identify that in one paragraph a patient is talking about two things; first is fear of surgery and second is fear of unrelieved pain. The codes for this paragraph could be ‘fear of surgery’ and ‘fear of pain’. In other areas of the transcript fear may arise again, and perhaps these codes will be merged into a category titled ‘fear’. Other concerns may emerge in this and other transcripts and perhaps best be represented by the theme ‘lack of control’. Themes are thus more abstract concepts, reflecting your interpretation of patterns across your data. So from codes, categories can be formed, and from categories, more encompassing themes are developed to describe the data in a form which summarises it, yet retains the richness, depth and context of the original data. Using quotations to illustrate categories and themes helps keep the analysis firmly grounded in the data. You need to constantly ask yourself ‘what is happening here?’ as you code and move from codes, to categories and themes, making sure you have data to support your decisions. Analysis inevitably involves subjective choices, and it is important to document what you have done and why, so a clear audit trail is provided. The coding example above describes codes inductively coming from the data. Some researchers may use a coding framework derived from, for example, the literature, their research questions or interview prompts, (Ritchie and Spencer 2 ) or a combination of both approaches.

Qualitative data, such as transcripts from an interview, are often routed in the interaction between the participant and the researcher. Reflecting on how you, as a researcher, may have influenced both the data collected and the analysis is an important part of the analysis.

As well as keeping your brain very much in gear, you need to be really organised. You may use highlighting pens and paper to keep track of your analysis, or use qualitative software to manage your data (such as NVivio or Atlas Ti). These programmes help you organise your data – you still have to do all the hard work to analyse it! Whatever you choose, it is important that you can trace your data back from themes to categories to codes. There is nothing more frustrating than looking for that illustrative patient quote, and not being able to find it.

If your qualitative data are part of a mixed methods study, (has both quantitative and qualitative data) careful thought has to be given to how you will analyse and present findings. Refer to O’Caithain et al 3 for more details.

There are many books and papers on qualitative analysis, a very few of which are listed below. 4 , – , 6 Working with someone with qualitative expertise is also invaluable, as you can read about it, but doing it really brings it alive.

- Richards L ,

- Ritchie J ,

- O'Cathain ,

- Bradley EH ,

- Huberman AM

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Nursing Research Guide

- General Search Strategies

- Searching by Author & Theory

- Searching for Qualitative Studies

- Searching for Systematic Reviews & Controlled Trials

- Health Data & Statistics

- Tutorials & Help

- SoN and APA (7th Ed.)

- NSC 890: PICOT Searches

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research in Nursing approaches a clinical question from a place of unknowing in an attempt to understand the complexity, depth, and richness of a particular situation from the perspective of the person or persons impacted by the situation (i.e., the subjects of the study).

Study subjects may include the patient(s), the patient's caregivers, the patient's family members, etc. Qualitative research may also include information gleaned from the investigator's or researcher's observations.

While typically more subjective than quantitative research (which focuses on measurements and numbers), qualitative research still employs a systematic approach.

Qualitative research is generally preferred over quantitative research (which on measurements and numbers) when the clinical question centers around life experiences or meaning.

Adapted from:

- Wilson, B., Austria, M.J., & Casucci, T. (2021 March 21). Understanding Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

- Chicca, J. (2020 June 5). Introduction to qualitative nursing research. American Nurse Journal.

Where can I find qualitative research?

Qualitative research can be found in numerous databases. Some good starting options are:

- CINAHL Ultimate Journal articles and eBooks in nursing and allied health.

- MEDLINE (EBSCOhost Web) Journal articles in medicine, life sciences, health care, and biomedical research.

- APA PsycINFO Articles from journals, newspapers, and magazines, along with eBooks in nearly every social science subject area.

- PubMed Citation search of journal articles and books in health and life sciences.

How can I find qualitative research?

Cinahl and/or medline.

- Start at the Advanced Search screen.

- Add a search term that represents the topic you are interested in into one (or more) of the search boxes.

- Scroll down until you see the Limit your results section.

- Qualitative - High Sensitivity (broadest category/broad search)

- Qualitative - High Specificity (narrowest category/specific search)

- Qualitative - Best Balance (somewhere in between)

- Select or click the search button.

APA PsycINFO

- Start at the Advanced Search screen.

- Use the Methodology menu to select Qualitative .

- Use the drop-down menu next the Enter search term box to set the search to MeSH Terms

- Qualitative Research

- Nursing Methodology Research

How can I use keywords to search for qualitative research?

Try adding adding a keyword that might specifically identify qualitative research. You could add the term qualitative to your search and/or your could add different types of qualitative research according to your specific needs and/or research assignment.

For example, consider the following types of qualitative research in light of the types of questions a researcher might be trying to answer with each qualitative research type:

- Clinical question: What happens to the quality of nursing practice when we implement a peer-mentoring system?

- Clinical question: How is patient autonomy promoted by a unit?

- Clinical question: What is the nursing role in end-of-life decisions?

- Clinical question: What discourses are used in nursing practice and how do they shape practice?

- Clinical question: How does Filipino culture influence childbirth experiences?

- Clinical question: What are the immediate underlying psychological and environmental causes of incivility in nursing?

- Clinical question: How does the basic social process of role transition happen within the context of advanced practice nursing transitions?

- Clinical question: When and why did nurses become researchers?

- Clinical question: How does one live with a diagnosis of scleroderma?

- Clinical question: What is the lived experience of nurses who were admitted as patients on their home practice units?

Adapted from: Chicca, J. (2020 June 5). Introduction to qualitative nursing research . American Nurse Journal.

Need more help?

Finding relevant qualitative research can be both difficult and time consuming. Once you conduct a search, you will need to review your search results and look at individual articles, their subject terms, and abstracts to determine if they are truly qualitative research articles. And that's a determination that only you can make.

If you still need help after trying the search strategies and tips suggested on this research guide, we encourage you to schedule an in-person or Zoom research appointment . Health Services librarian Rachel Riffe-Albright is a great bet, but any librarian would be happy to help!

Additonal resources on qualitative research

The following are research guides created by other academic libraries. While you likely will not have access to any of their linked resources, the tips and tricks shared may be useful to you as you search for qualitative research:

- What is Qualitative Research? from UTA Libraries at University of Texas Arlington

- Finding Qualitative Research Articles from Ashland University Library

- Finding Qualitative Research Articles from the Health Sciences Library at University of Washington

- Advanced Search Guide: Qualitative and Quantitative Studies from Southern Connecticut State University Library

- Finding Qualitative and Quantitative Studies in CINAHL from Southern Connecticut State University Library

- << Previous: Searching by Author & Theory

- Next: Searching for Systematic Reviews & Controlled Trials >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 2:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eku.edu/nursing

EO/AA Statement | Privacy Statement | 103 Libraries Complex Crabbe Library Richmond, KY 40475 | (859) 622-1790 ©

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 09 November 2005

A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice

- Farkhondeh Sharif 1 &

- Sara Masoumi 2

BMC Nursing volume 4 , Article number: 6 ( 2005 ) Cite this article

362k Accesses

169 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Nursing student's experiences of their clinical practice provide greater insight to develop an effective clinical teaching strategy in nursing education. The main objective of this study was to investigate student nurses' experience about their clinical practice.

Focus groups were used to obtain students' opinion and experiences about their clinical practice. 90 baccalaureate nursing students at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery) were selected randomly from two hundred students and were arranged in 9 groups of ten students. To analyze the data the method used to code and categories focus group data were adapted from approaches to qualitative data analysis.

Four themes emerged from the focus group data. From the students' point of view," initial clinical anxiety", "theory-practice gap"," clinical supervision", professional role", were considered as important factors in clinical experience.

The result of this study showed that nursing students were not satisfied with the clinical component of their education. They experienced anxiety as a result of feeling incompetent and lack of professional nursing skills and knowledge to take care of various patients in the clinical setting.

Peer Review reports

Clinical experience has been always an integral part of nursing education. It prepares student nurses to be able of "doing" as well as "knowing" the clinical principles in practice. The clinical practice stimulates students to use their critical thinking skills for problem solving [ 1 ]

Awareness of the existence of stress in nursing students by nurse educators and responding to it will help to diminish student nurses experience of stress. [ 2 ]

Clinical experience is one of the most anxiety producing components of the nursing program which has been identified by nursing students. In a descriptive correlational study by Beck and Srivastava 94 second, third and fourth year nursing students reported that clinical experience was the most stressful part of the nursing program[ 3 ]. Lack of clinical experience, unfamiliar areas, difficult patients, fear of making mistakes and being evaluated by faculty members were expressed by the students as anxiety-producing situations in their initial clinical experience. In study done by Hart and Rotem stressful events for nursing students during clinical practice have been studied. They found that the initial clinical experience was the most anxiety producing part of their clinical experience [ 4 ]. The sources of stress during clinical practice have been studied by many researchers [ 5 – 10 ] and [ 11 ].

The researcher came to realize that nursing students have a great deal of anxiety when they begin their clinical practice in the second year. It is hoped that an investigation of the student's view on their clinical experience can help to develop an effective clinical teaching strategy in nursing education.

A focus group design was used to investigate the nursing student's view about the clinical practice. Focus group involves organized discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain information about their views and experiences of a topic and is particularly suited for obtaining several perspectives about the same topic. Focus groups are widely used as a data collection technique. The purpose of using focus group is to obtain information of a qualitative nature from a predetermined and limited number of people [ 12 , 13 ].

Using focus group in qualitative research concentrates on words and observations to express reality and attempts to describe people in natural situations [ 14 ].

The group interview is essentially a qualitative data gathering technique [ 13 ]. It can be used at any point in a research program and one of the common uses of it is to obtain general background information about a topic of interest [ 14 ].

Focus groups interviews are essential in the evaluation process as part of a need assessment, during a program, at the end of the program or months after the completion of a program to gather perceptions on the outcome of that program [ 15 , 16 ]. Kruegger (1988) stated focus group data can be used before, during and after programs in order to provide valuable data for decision making [ 12 ].

The participants from which the sample was drawn consisted of 90 baccalaureate nursing students from two hundred nursing students (30 students from the second year and 30 from the third and 30 from the fourth year) at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery). The second year nursing students already started their clinical experience. They were arranged in nine groups of ten students. Initially, the topics developed included 9 open-ended questions that were related to their nursing clinical experience. The topics were used to stimulate discussion.

The following topics were used to stimulate discussion regarding clinical experience in the focus groups.

How do you feel about being a student in nursing education?

How do you feel about nursing in general?

Is there any thing about the clinical field that might cause you to feel anxious about it?

Would you like to talk about those clinical experiences which you found most anxiety producing?

Which clinical experiences did you find enjoyable?

What are the best and worst things do you think can happen during the clinical experience?

What do nursing students worry about regarding clinical experiences?

How do you think clinical experiences can be improved?

What is your expectation of clinical experiences?

The first two questions were general questions which were used as ice breakers to stimulate discussion and put participants at ease encouraging them to interact in a normal manner with the facilitator.

Data analysis

The following steps were undertaken in the focus group data analysis.

Immediate debriefing after each focus group with the observer and debriefing notes were made. Debriefing notes included comments about the focus group process and the significance of data

Listening to the tape and transcribing the content of the tape

Checking the content of the tape with the observer noting and considering any non-verbal behavior. The benefit of transcription and checking the contents with the observer was in picking up the following:

Parts of words

Non-verbal communication, gestures and behavior...

The researcher facilitated the groups. The observer was a public health graduate who attended all focus groups and helped the researcher by taking notes and observing students' on non-verbal behavior during the focus group sessions. Observer was not known to students and researcher

The methods used to code and categorise focus group data were adapted from approaches to qualitative content analysis discussed by Graneheim and Lundman [ 17 ] and focus group data analysis by Stewart and Shamdasani [ 14 ] For coding the transcript it was necessary to go through the transcripts line by line and paragraph by paragraph, looking for significant statements and codes according to the topics addressed. The researcher compared the various codes based on differences and similarities and sorted into categories and finally the categories was formulated into a 4 themes.

The researcher was guided to use and three levels of coding [ 17 , 18 ]. Three levels of coding selected as appropriate for coding the data.

Level 1 coding examined the data line by line and making codes which were taken from the language of the subjects who attended the focus groups.

Level 2 coding which is a comparing of coded data with other data and the creation of categories. Categories are simply coded data that seem to cluster together and may result from condensing of level 1 code [ 17 , 19 ].

Level 3 coding which describes the Basic Social Psychological Process which is the title given to the central themes that emerge from the categories.

Table 1 shows the three level codes for one of the theme

The documents were submitted to two assessors for validation. This action provides an opportunity to determine the reliability of the coding [ 14 , 15 ]. Following a review of the codes and categories there was agreement on the classification.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted after approval has been obtained from Shiraz university vice-chancellor for research and in addition permission to conduct the study was obtained from Dean of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery. All participants were informed of the objective and design of the study and a written consent received from the participants for interviews and they were free to leave focus group if they wish.

Most of the students were females (%94) and single (% 86) with age between 18–25.

The qualitative analysis led to the emergence of the four themes from the focus group data. From the students' point of view," initial clinical anxiety", "theory-practice gap", clinical supervision"," professional role", was considered as important factors in clinical experience.

Initial clinical anxiety

This theme emerged from all focus group discussion where students described the difficulties experienced at the beginning of placement. Almost all of the students had identified feeling anxious in their initial clinical placement. Worrying about giving the wrong information to the patient was one of the issues brought up by students.

One of the students said:

On the first day I was so anxious about giving the wrong information to the patient. I remember one of the patients asked me what my diagnosis is. ' I said 'I do not know', she said 'you do not know? How can you look after me if you do not know what my diagnosis is?'

From all the focus group sessions, the students stated that the first month of their training in clinical placement was anxiety producing for them.

One of the students expressed:

The most stressful situation is when we make the next step. I mean ... clinical placement and we don't have enough clinical experience to accomplish the task, and do our nursing duties .

Almost all of the fourth year students in the focus group sessions felt that their stress reduced as their training and experience progressed.

Another cause of student's anxiety in initial clinical experience was the students' concern about the possibility of harming a patient through their lack of knowledge in the second year.

One of the students reported:

In the first day of clinical placement two patients were assigned to me. One of them had IV fluid. When I introduced myself to her, I noticed her IV was running out. I was really scared and I did not know what to do and I called my instructor .

Fear of failure and making mistakes concerning nursing procedures was expressed by another student. She said:

I was so anxious when I had to change the colostomy dressing of my 24 years old patient. It took me 45 minutes to change the dressing. I went ten times to the clinic to bring the stuff. My heart rate was increasing and my hand was shaking. I was very embarrassed in front of my patient and instructor. I will never forget that day .

Sellek researched anxiety-creating incidents for nursing students. He suggested that the ward is the best place to learn but very few of the learner's needs are met in this setting. Incidents such as evaluation by others on initial clinical experience and total patient care, as well as interpersonal relations with staff, quality of care and procedures are anxiety producing [ 11 ].

Theory-practice gap

The category theory-practice gap emerged from all focus discussion where almost every student in the focus group sessions described in some way the lack of integration of theory into clinical practice.

I have learnt so many things in the class, but there is not much more chance to do them in actual settings .

Another student mentioned:

When I just learned theory for example about a disease such as diabetic mellitus and then I go on the ward and see the real patient with diabetic mellitus, I relate it back to what I learned in class and that way it will remain in my mind. It is not happen sometimes .

The literature suggests that there is a gap between theory and practice. It has been identified by Allmark and Tolly [ 20 , 21 ]. The development of practice theory, theory which is developed from practice, for practice, is one way of reducing the theory-practice gap [ 21 ]. Rolfe suggests that by reconsidering the relationship between theory and practise the gap can be closed. He suggests facilitating reflection on the realities of clinical life by nursing theorists will reduce the theory-practice gap. The theory- practice gap is felt most acutely by student nurses. They find themselves torn between the demands of their tutor and practising nurses in real clinical situations. They were faced with different real clinical situations and are unable to generalise from what they learnt in theory [ 22 ].

Clinical supervision

Clinical supervision is recognised as a developmental opportunity to develop clinical leadership. Working with the practitioners through the milieu of clinical supervision is a powerful way of enabling them to realize desirable practice [ 23 ]. Clinical nursing supervision is an ongoing systematic process that encourages and supports improved professional practice. According to Berggren and Severinsson the clinical nurse supervisors' ethical value system is involved in her/his process of decision making. [ 24 , 25 ]

Clinical Supervision by Head Nurse (Nursing Unit Manager) and Staff Nurses was another issue discussed by the students in the focus group sessions. One of the students said:

Sometimes we are taught mostly by the Head Nurse or other Nursing staff. The ward staff are not concerned about what students learn, they are busy with their duties and they are unable to have both an educational and a service role

Another student added:

Some of the nursing staff have good interaction with nursing students and they are interested in helping students in the clinical placement but they are not aware of the skills and strategies which are necessary in clinical education and are not prepared for their role to act as an instructor in the clinical placement

The students mostly mentioned their instructor's role as an evaluative person. The majority of students had the perception that their instructors have a more evaluative role than a teaching role.

The literature suggests that the clinical nurse supervisors should expressed their existence as a role model for the supervisees [ 24 ]

Professional role

One view that was frequently expressed by student nurses in the focus group sessions was that students often thought that their work was 'not really professional nursing' they were confused by what they had learned in the faculty and what in reality was expected of them in practice.

We just do basic nursing care, very basic . ... You know ... giving bed baths, keeping patients clean and making their beds. Anyone can do it. We spend four years studying nursing but we do not feel we are doing a professional job .

The role of the professional nurse and nursing auxiliaries was another issue discussed by one of the students:

The role of auxiliaries such as registered practical nurse and Nurses Aids are the same as the role of the professional nurse. We spend four years and we have learned that nursing is a professional job and it requires training and skills and knowledge, but when we see that Nurses Aids are doing the same things, it can not be considered a professional job .

The result of student's views toward clinical experience showed that they were not satisfied with the clinical component of their education. Four themes of concern for students were 'initial clinical anxiety', 'theory-practice gap', 'clinical supervision', and 'professional role'.

The nursing students clearly identified that the initial clinical experience is very stressful for them. Students in the second year experienced more anxiety compared with third and fourth year students. This was similar to the finding of Bell and Ruth who found that nursing students have a higher level of anxiety in second year [ 26 , 27 ]. Neary identified three main categories of concern for students which are the fear of doing harm to patients, the sense of not belonging to the nursing team and of not being fully competent on registration [ 28 ] which are similar to what our students mentioned in the focus group discussions. Jinks and Patmon also found that students felt they had an insufficiency in clinical skills upon completion of pre-registration program [ 29 ].

Initial clinical experience was the most anxiety producing part of student clinical experience. In this study fear of making mistake (fear of failure) and being evaluated by faculty members were expressed by the students as anxiety-producing situations in their initial clinical experience. This finding is supported by Hart and Rotem [ 4 ] and Stephens [ 30 ]. Developing confidence is an important component of clinical nursing practice [ 31 ]. Development of confidence should be facilitated by the process of nursing education; as a result students become competent and confident. Differences between actual and expected behaviour in the clinical placement creates conflicts in nursing students. Nursing students receive instructions which are different to what they have been taught in the classroom. Students feel anxious and this anxiety has effect on their performance [ 32 ]. The existence of theory-practice gap in nursing has been an issue of concern for many years as it has been shown to delay student learning. All the students in this study clearly demonstrated that there is a gap between theory and practice. This finding is supported by other studies such as Ferguson and Jinks [ 33 ] and Hewison and Wildman [ 34 ] and Bjork [ 35 ]. Discrepancy between theory and practice has long been a source of concern to teachers, practitioners and learners. It deeply rooted in the history of nurse education. Theory-practice gap has been recognised for over 50 years in nursing. This issue is said to have caused the movement of nurse education into higher education sector [ 34 ].

Clinical supervision was one of the main themes in this study. According to participant, instructor role in assisting student nurses to reach professional excellence is very important. In this study, the majority of students had the perception that their instructors have a more evaluative role than a teaching role. About half of the students mentioned that some of the head Nurse (Nursing Unit Manager) and Staff Nurses are very good in supervising us in the clinical area. The clinical instructor or mentors can play an important role in student nurses' self-confidence, promote role socialization, and encourage independence which leads to clinical competency [ 36 ]. A supportive and socialising role was identified by the students as the mentor's function. This finding is similar to the finding of Earnshaw [ 37 ]. According to Begat and Severinsson supporting nurses by clinical nurse specialist reported that they may have a positive effect on their perceptions of well-being and less anxiety and physical symptoms [ 25 ].

The students identified factors that influence their professional socialisation. Professional role and hierarchy of occupation were factors which were frequently expressed by the students. Self-evaluation of professional knowledge, values and skills contribute to the professional's self-concept [ 38 ]. The professional role encompasses skills, knowledge and behaviour learned through professional socialisation [ 39 ]. The acquisition of career attitudes, values and motives which are held by society are important stages in the socialisation process [ 40 ]. According to Corwin autonomy, independence, decision-making and innovation are achieved through professional self-concept 41 . Lengacher (1994) discussed the importance of faculty staff in the socialisation process of students and in preparing them for reality in practice. Maintenance and/or nurturance of the student's self-esteem play an important role for facilitation of socialisation process 42 .

One view that was expressed by second and third year student nurses in the focus group sessions was that students often thought that their work was 'not really professional nursing' they were confused by what they had learned in the faculty and what in reality was expected of them in practice.

The finding of this study and the literature support the need to rethink about the clinical skills training in nursing education. It is clear that all themes mentioned by the students play an important role in student learning and nursing education in general. There were some similarities between the results of this study with other reported studies and confirmed that some of the factors are universal in nursing education. Nursing students expressed their views and mentioned their worry about the initial clinical anxiety, theory-practice gap, professional role and clinical supervision. They mentioned that integration of both theory and practice with good clinical supervision enabling them to feel that they are enough competent to take care of the patients. The result of this study would help us as educators to design strategies for more effective clinical teaching. The results of this study should be considered by nursing education and nursing practice professionals. Faculties of nursing need to be concerned about solving student problems in education and clinical practice. The findings support the need for Faculty of Nursing to plan nursing curriculum in a way that nursing students be involved actively in their education.

Dunn SV, Burnett P: The development of a clinical learning environment scale. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995, 22: 1166-1173.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lindop E: Factors associated with student and pupil nurse wastage. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1987, 12 (6): 751-756.

Beck D, Srivastava R: Perceived level and source of stress in baccalaureate nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education. 1991, 30 (3): 127-132.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hart G, Rotem A: The best and the worst: Students' experience of clinical education. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994, 11 (3): 26-33.

Sheila Sh, Huey-Shyon L, Shiowli H: Perceived stress and physio-psycho-social status of nursing students during their initial period of clinical practice. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2002, 39: 165-175. 10.1016/S0020-7489(01)00016-5.

Article Google Scholar

Johnson J: Reducing distress in first level and student nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000, 32 (1): 66-74. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01421.x.

Admi H: Nursing students' stress during the initial clinical experience. Journal of Nursing Education. 1997, 36: 323-327.

Blainey GC: Anxiety in the undergraduate medical-surgical clinical student. Journal of Nursing Education. 1980, 19 (8): 33-36.

Wong J, Wong S: Towards effective clinical teaching in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1987, 12 (4): 505-513.

Windsor A: Nursing students' perceptions of clinical experience. Journal of Nursing Education. 1987, 26 (4): 150-154.

Sellek T: Satisfying and anxiety creating incidents for nursing students. Nursing Times. 1982, 78 (35): 137-140.

PubMed Google Scholar

Krueger RA: Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Sage Publications: California. 1988

Google Scholar

Denzin NK: The Research Act. 1989, Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 3

Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN: Analysing focus group data. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. Edited by: Shamdasani PN. 1990, Sage Publications: Newbury Park

Barbour RS, Kitzinger J: Developing focus group research : politics, theory and practice. Sage. 1999

Patton MQ: Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 1990, Sage publications, 2

Graneheim UH, Lundman B: Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004, 24: 105-112. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR: Qualitative Research in Nursing. Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 1995, J.B. Lippincott Company: Philadelphia

Polit DF, Hungler BP: Nursing research: Principles and Methods. Philadelphia newyork. 1999

Allmark PA: classical view of the theory-practice gap in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995, 22 (1): 18-23. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22010018.x.

Tolley KA: Theory from practice for practice: Is this a reality?. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995, 21 (1): 184-190. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21010184.x.

Rolfe G: Listening to students: Course evaluation as action research. Nurse Education Today. 1994, 14 (3): 223-227. 10.1016/0260-6917(94)90085-X.

Johns Ch: clinical supervision as a model for clinical leadership. Journal of Nursing Management. 2003, 11: 25-34. 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2002.00288.x.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Berggren I, Severinsson E: Nurses supervisors'action in relation to their decision-making style and ethical approach to clinical supervision. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003, 41 (6): 615-622. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02573.x.

Begat I, Severinsson E: Nurses' satisfaction with their work environment and the outcomes of clinical nursing supervision on nurses' experiences of well-being. Journal of Nursing Management. 2005, 13: 221-230. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00527.x.

Bell P: Anxiety in mature age and higher school certificate entry student nurses – A comparison of effects on performance. Journal of Australian Congress of Mental Health Nurses. 1984, 4/5: 13-21.

Ruth L: Experiencing before and throughout the nursing career. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002, 39: 119-10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02251.x.

Neary M: Project 2000 students' survival kit: a return to the practical room. Nurse Education Today. 1997, 17 (1): 46-52. 10.1016/S0260-6917(97)80078-0.

Jinks A, Pateman B: Nither this nor that: The stigma of being an undergraduate nurse. Nursing Times. 1998, 2 (2): 12-13.

CAS Google Scholar

Stephen RL: Imagery: A treatment for nursing student anxiety. Journal of Nursing Education. 1992, 31 (7): 314-319.

Grundy SE: The confidence scale. Nurse Educator. 1993, 18 (1): 6-9.

Copeland L: Developing student confidence. Nurse Educator. 1990, 15 (1): 7-

Ferguson K, Jinks A: Integrating what is taught with what is practised in the nursing curriculum: A multi-dimensional model. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994, 20 (4): 687-695. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20040687.x.

Hewison A, Wildman S: The theory-practice gap in nursing: A new dimension. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996, 24 (4): 754-761. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.25214.x.

Bjork T: Neglected conflicts in the discipline of nursing: Perceptions of the importance and value of practical skill. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995, 22 (1): 6-12. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22010006.x.

Busen N: Mentoring in advanced practice nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice. 1999, 2: 2-

Earnshaw GP: Mentorship: The students' view. Nurse Education Today. 1995, 15 (4): 274-279. 10.1016/S0260-6917(95)80130-8.

Kelly B: The professional self-concepts of nursing undergraduates and their perceptions of influential forces. Journal of Nursing Education. 1992, 31 (3): 121-125.

Lynn MR, McCain NL, Boss BJ: Socialization of R.N. to B.S.N Image:. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1989, 21 (4): 232-237.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Klein SM, Ritti RR: Understanding Organisational Behaviour. 1980, Kent: Boston

Corwin RG: The professional employee: A study of conflict in nursing roles. The American Journal of Sociology. 1961, 66: 604-615. 10.1086/223010.

Lengacher CA: Effects of professional development seminars on role conception, role deprivation, and self-esteem of generic baccalaureate students. Nursing Connections. 1994, 7 (1): 21-34.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6955/4/6/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the student nurses who participated in this study for their valuable contribution

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Psychiatric Nursing Department, Fatemeh (P.B.U.H) College of Nursing and Midwifery Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Zand BlvD, Shiraz, Iran

Farkhondeh Sharif

English Department, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

Sara Masoumi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Farkhondeh Sharif .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author(s) declare that they no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FSH: Initiation and design of the research, focus groups conduction, data collection, analysis and writing the paper, SM: Editorial revision of paper

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sharif, F., Masoumi, S. A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice. BMC Nurs 4 , 6 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-4-6

Download citation

Received : 10 June 2005

Accepted : 09 November 2005

Published : 09 November 2005

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-4-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Focus Group

- Nursing Student

- Professional Role

- Nursing Education

- Focus Group Session

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Quantitative and Qualitative Research

You can find evidence for clinical decision making in quantitative and qualitative research studies . Quantitative research refers to any research based on something that can be accurately and precisely measured and will include studies that have numerical data . Quantitative data are expressed numerically and analyzed statistically. The data are collected from experiments and tests, metrics, databases, and surveys. In healthcare research they often include studies of intervention effectiveness, satisfaction with care, the incidence, prevalence, and etiology of diseases, and the properties of measurement tools (Kolaski, 2023).

Findings in qualitative studies are not based on measurable statistics. Qualitative data are descriptive rather than numerical. Qualitative research derives data from observation, interviews, verbal interactions, or textual analyses and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants. Qualitative research studies in healthcare investigate the impact of illnesses and interventions. The research explores experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians (Kolaski, 2023). The analysis of qualitative research is interpretative, subjective, and impressionistic.

Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2023). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews , 12 (1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02255-9

Quantitative vs Qualitative Study Types:

For more information on qualitative research:

Curtis, A. & Keeler, C. (2022). An introduction to qualitative methods for the nurse researcher. American Journal of Nursing, 122 (8), 52-56. https://doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000854992.17329.51.

Noyes, J., Booth, A., Cargo, M., Flemming, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Pantoja, T., & Thomas, J. (2023). Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A. (Eds.). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.4. Cochrane. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Video: UniversityNow: Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

Appraising Quantitative and Qualitative Research

The articles below provide a step-by-step appraisal on how to critique quantitative and qualitative research articles:

- Ryan, F., Coughlan, M. & Cronin, P. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: quantitative research. British Journal of Nursing, 16 (11), 658-663 .

- Ryan, F., Coughlan, M. & Cronin, P. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 2: qualitative research. British Journal of Nursing, 16 (2), 738-744 .

- << Previous: Study Types & Terminology

- Next: Critical Appraisal: Evaluating Studies >>

- Evidence-Based Medicine/Evidence-Based Practice

- Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

- Question Types

- Levels of Evidence

- Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

- Study Types & Terminology

- Critical Appraisal: Evaluating Studies

- Conducting a Systematic Review

- Research Study Design

- Selected Books for EBP Research

- Find a Book by Call Number

- Find EBP Articles in the Databases

- Selected EBP Journals

- Finding the Full Text of an Article from a Citation

- Nursing Databases

- Databases for EBP

- More EBP Resources

- Intro to Nursing Resources

- Citation Management Programs

- Annotated Bibliography

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.adelphi.edu/evidence-based-practice

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

Nursing Resources : Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Differences between Qualitative & Quantitative Research

" Quantitative research ," also called " empirical research ," refers to any research based on something that can be accurately and precisely measured. For example, it is possible to discover exactly how many times per second a hummingbird's wings beat and measure the corresponding effects on its physiology (heart rate, temperature, etc.).

" Qualitative research " refers to any research based on something that is impossible to accurately and precisely measure. For example, although you certainly can conduct a survey on job satisfaction and afterwards say that such-and-such percent of your respondents were very satisfied with their jobs, it is not possible to come up with an accurate, standard numerical scale to measure the level of job satisfaction precisely.

It is so easy to confuse the words "quantitative" and "qualitative," it's best to use "empirical" and "qualitative" instead.

Hint: An excellent clue that a scholarly journal article contains empirical research is the presence of some sort of statistical analysis

See "Examples of Qualitative and Quantitative" page under "Nursing Research" for more information.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Considered hard science |

| Considered soft science |

| Objective |

| Subjective |

| Deductive reasoning used to synthesize data |

| Inductive reasoning used to synthesize data |

| Focus—concise and narrow |

| Focus—complex and broad |

| Tests theory |

| Develops theory |

| Basis of knowing—cause and effect relationships |

| Basis of knowing—meaning, discovery |

| Basic element of analysis—numbers and statistical analysis |

| Basic element of analysis—words, narrative |

| Single reality that can be measured and generalized |

| Multiple realities that are continually changing with individual interpretation |

- John M. Pfau Library

Examples of Qualitative vs Quantitiative

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| What is the impact of a learner-centered hand washing program on a group of 2 graders? | Paper and pencil test resulting in hand washing scores | Yes | Quantitative |

| What is the effect of crossing legs on blood pressure measurement? | Blood pressure measurements before and after crossing legs resulting in numbers | Yes | Quantitative |

| What are the experiences of fathers concerning support for their wives/partners during labor? | Unstructured interviews with fathers (5 supportive, 5 non-supportive): results left in narrative form describing themes based on nursing for the whole person theory | No | Qualitative |

| What is the experience of hope in women with advances ovarian cancer? | Semi-structures interviews with women with advances ovarian cancer (N-20). Identified codes and categories with narrative examples | No | Qualitative |

- << Previous: Table of Evidence

- Next: Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 10:13 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

[Importance of qualitative research for nursing and nursing science]

Affiliation.

- 1 Universität Utrecht.

- PMID: 9370721

Qualitative research has an important place in nursing science and is becoming increasingly recognized. Qualitative research in nursing mainly deals with the lived experiences of patients and nurses. In the field of chronic illness, qualitative research has brought to the open some of the processes chronically ill patients undergo and what it means living with chronic illness. In addition, new insights were gained about the processes involved in receiving and in giving care. Qualitative research about chronic illness provided nurses with understanding of the lived experience of patients. This understanding is essential for good nursing care. However, qualitative research is not the only method and for some aspects of nursing not the adequate one. Qualitative and quantitative research are complementary.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Two decades of insider research: what we know and don't know about chronic illness experience. Thorne SE, Paterson BL. Thorne SE, et al. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2000;18:3-25. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2000. PMID: 10918930 Review.

- Capturing day-to-day aspects of living with chronic illness: the need for longitudinal designs. Russell CK, Gregory DM. Russell CK, et al. Can J Nurs Res. 2000 Dec;32(3):99-102. Can J Nurs Res. 2000. PMID: 11928137 Review. No abstract available.

- Ricoeur's hermeneutic phenomenology: an implication for nursing research. Charalambous A, Papadopoulos IR, Beadsmoore A. Charalambous A, et al. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008 Dec;22(4):637-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00566.x. Epub 2008 Oct 16. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008. PMID: 19000085

- The nature of hope in hospitalized chronically ill patients. Kim DS, Kim HS, Schwartz-Barcott D, Zucker D. Kim DS, et al. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006 Jul;43(5):547-56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.010. Epub 2005 Sep 6. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006. PMID: 16140301

- Clients with chronic and complex conditions: their experiences of community nursing services. Wilkes L, Cioffi J, Warne B, Harrison K, Vonu-Boriceanu O. Wilkes L, et al. J Clin Nurs. 2008 Apr;17(7B):160-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02454.x. J Clin Nurs. 2008. PMID: 18578792

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Evidence Based Nursing

- Electronic Resources

- Step 1: Ask

- Step 2: Aquire

- Step 3: Appraise

- Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Systematic Reviews

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

- Searching Tips

- APA Citations

- Useful Websites

Difference between Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

Qualitative research allows you to discover the why and how of people and activities. The abstract from this dissertation shows the study:

- Asks open-ended questions

- Examines people's activities

- Gives a narrative conclusion

- Observations and Interviews

- Understanding and interpreting social interactions and behaviors

- Uses a small group of subjects

- Uses words

Quantitative research is based on things that can be accurately and precisely measured. The abstract shows that this dissertation:

- Describes with statistics

- Gives a statistical result

- Makes predictions

- Objective

- Studies a randomly selected group

- Tests a theory

- Uses numbers

- Uses a survey

Identifying Quantitative Research- Example

This abstract has several indications that this is a quantitative study:

- the goal of the study was examining relationships between several variables

- the researchers used statistical methods (logistic regression models)

- subjects completed questionnaires

- the study included a large number of subjects

Based on Eastern Michigan University Library Libguide Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Identifying Qualitative Research-Example

This abstract has several indications that this is a qualitative study:

- the goal of the study was to explore the subjects' experiences.

- the researchers conducted open-ended interviews.

- the researchers used thematic analysis when reviewing the interviews.

Based on Eastern Michigan University Library Libguide Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- << Previous: Systematic Reviews

- Next: Searching Tips >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 10:17 AM

- URL: https://libguide.umary.edu/evidencebasednursing

Nursing: Quantitative vs. Qualitative?

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Searching for Empirical Articles

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Systematic Reviews

- Grey Literature

- Writing a Literature Review

- Annotated Bibliography vs. Literature Review

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative?

- Writing Help

Qualitative vs Quantitative worksheet

- Methodology Decision Tree This diagram should help you to determine whether the research you are looking at is qualitative or quantitative. NOTE: This is a brief guide and might not be correct in every instance

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography vs. Literature Review

- Next: EndNote >>

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2024 10:22 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.fullerton.edu/nursing

This site is maintained by Pollak Library .

To report problems or comments with this site, please contact [email protected] . © California State University, Fullerton. All Rights Reserved.

Web Accessibility

CSUF is committed to ensuring equal accessibility to our users. Let us know about any accessibility problems you encounter using this website. We'll do our best to improve things and get you the information you need.

- Adobe Reader

- Microsoft Viewers

- Report An ATI Issue

- Accessible @ CSUF

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

The design, implementation, and evaluation of a blended (in-person and virtual) Clinical Competency Examination for final-year nursing students

- Rita Mojtahedzadeh 1 ,

- Tahereh Toulabi 2 , 3 &

- Aeen Mohammadi 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 936 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Studies have reported different results of evaluation methods of clinical competency tests. Therefore, this study aimed to design, implement, and evaluate a blended (in-person and virtual) Competency Examination for final-year Nursing Students.