Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

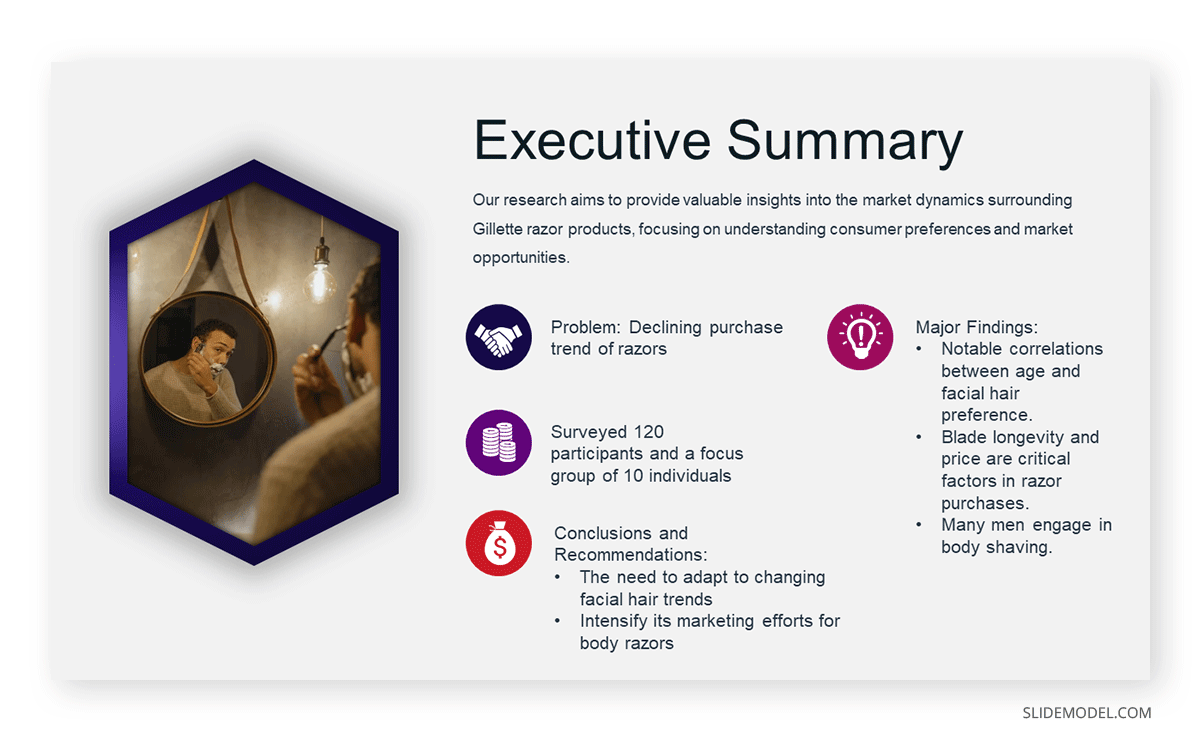

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

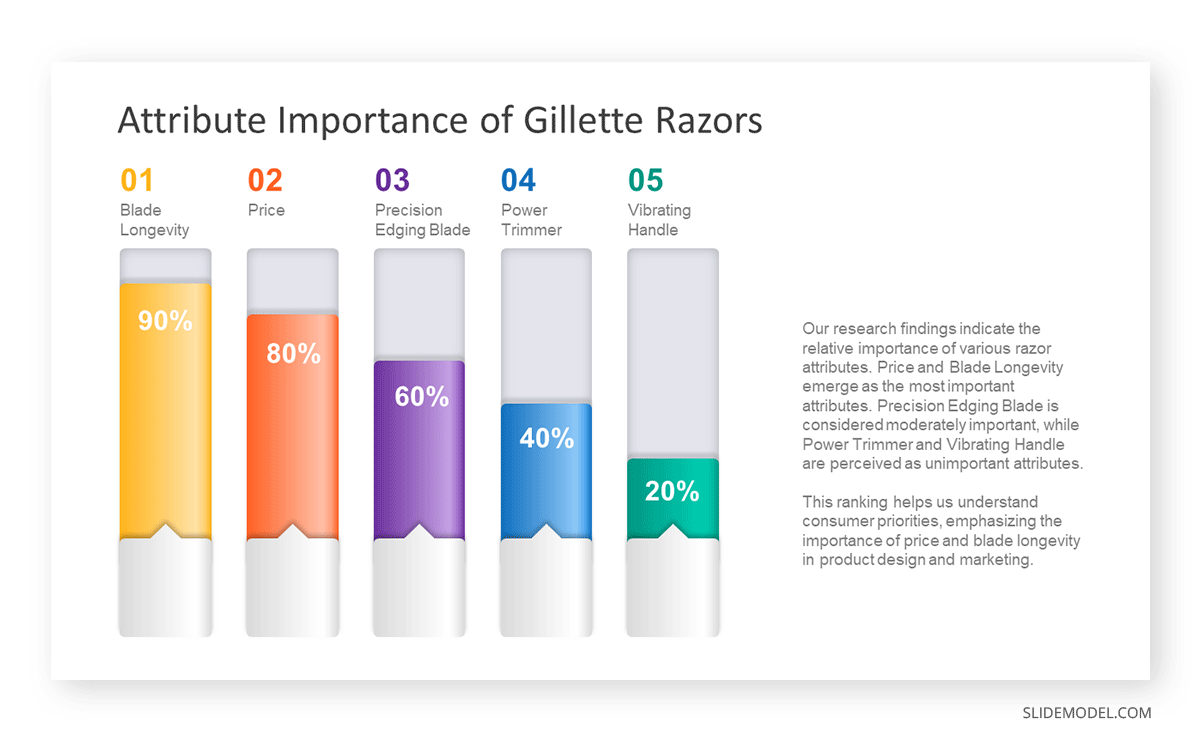

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

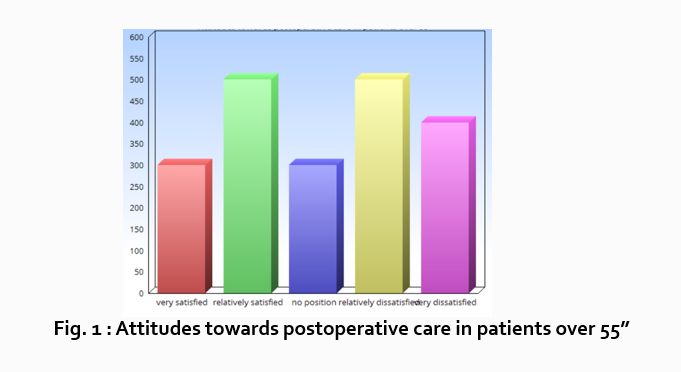

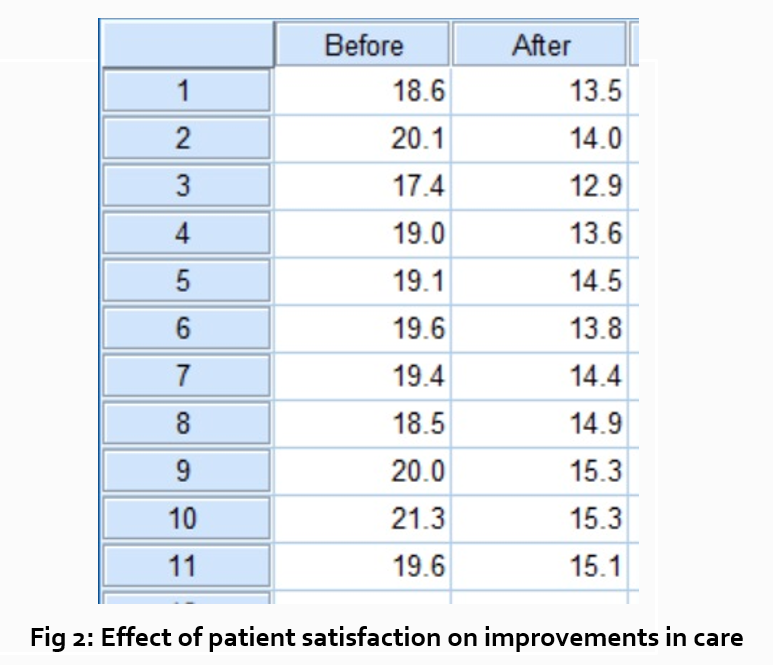

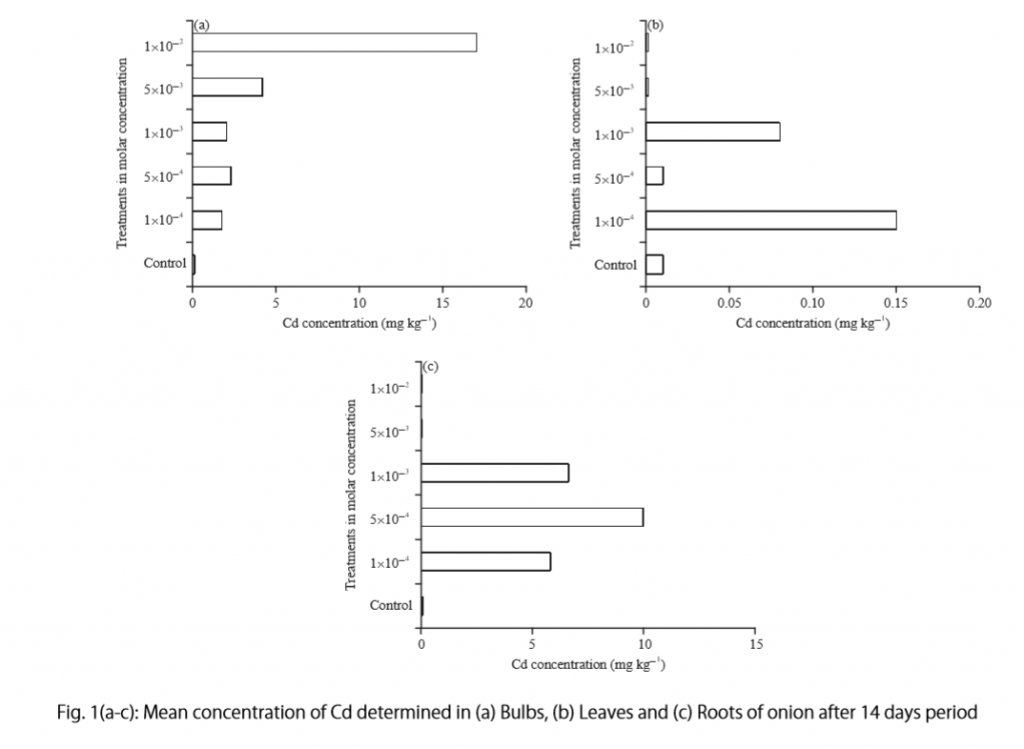

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

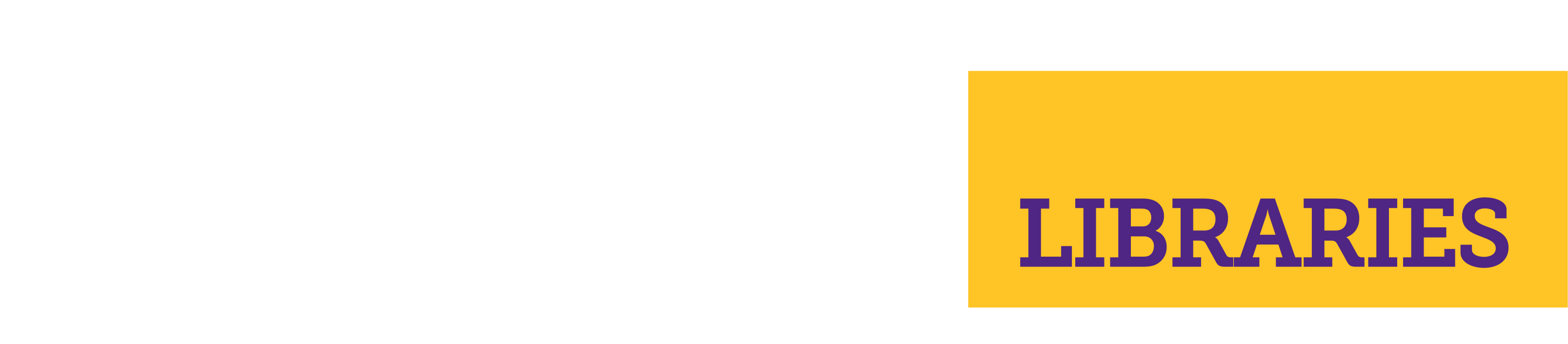

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

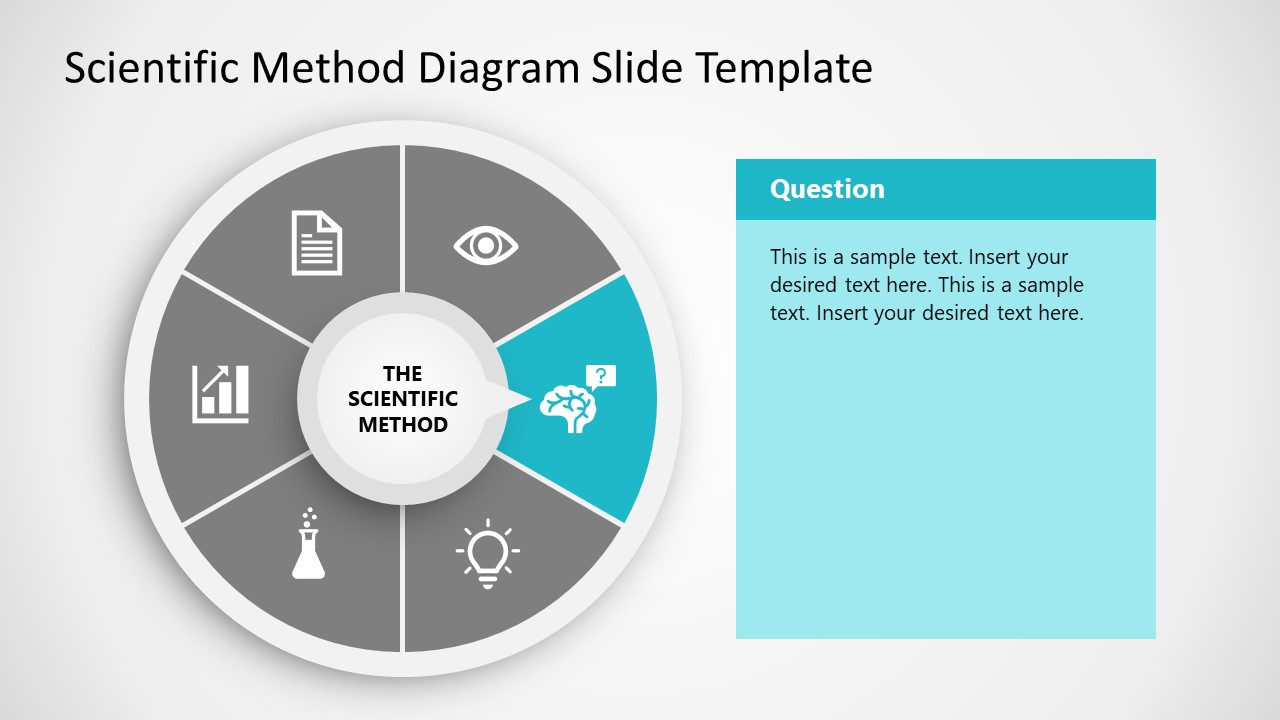

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

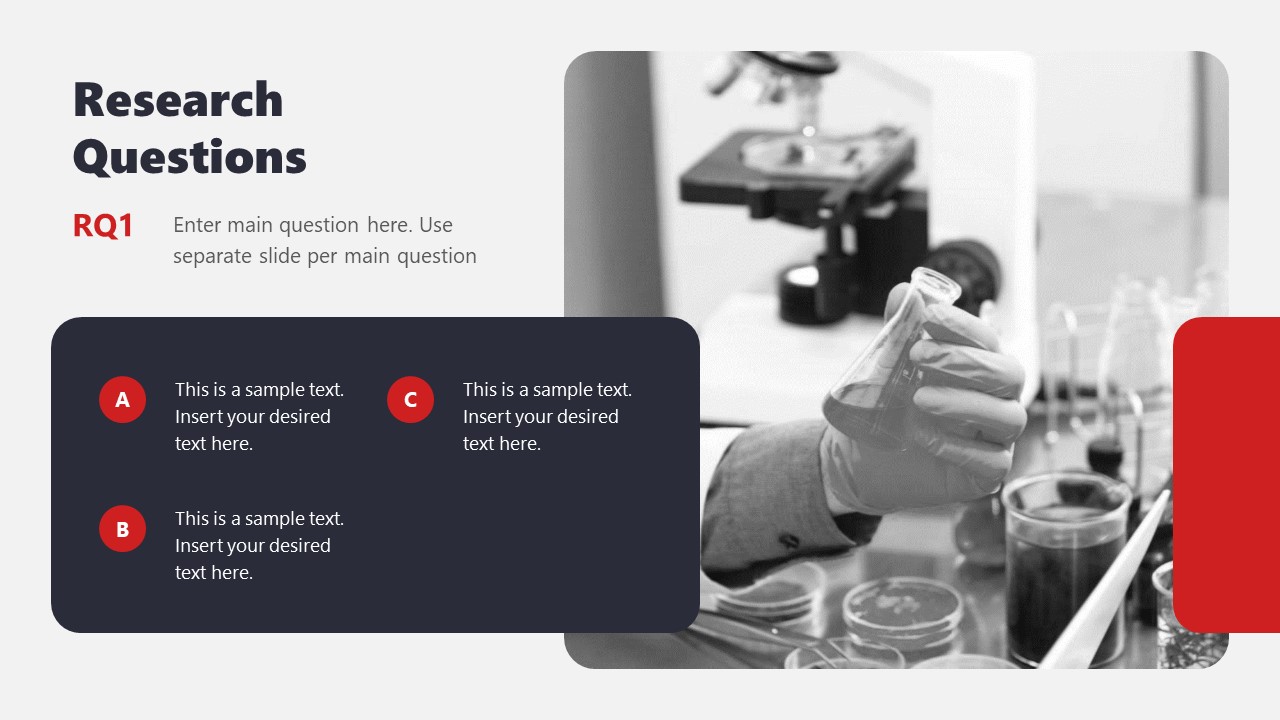

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Design • August 14th, 2024

Creating Custom Themes for PowerPoint and Google Slides

Do you want your slides to go beyond the average result from a template? If so, learn how to create custom themes for presentations with this guide.

Filed under Business • July 24th, 2024

How to Create a Demo Presentation

Discover the secrets behind successful demo presentations and what they should contain with this article. Recommended PPT templates included.

Filed under Presentation Ideas • July 17th, 2024

How to Convert a Text Document into a Presentation with AI

One of the biggest challenges for presenters is to summarize content from lengthy reports, academic papers, or any other kind of written media in an informative and concise way. Rather than losing countless hours going over and over the same text, we can speed up the process thanks to the virtues of artificial intelligence. In […]

Leave a Reply

- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

This chapter serves as the culmination of the previous chapters, in that it focuses on how to present the results of one's study, regardless of the choice made among the three methods. Writing in academics has a form and style that you will want to apply not only to report your own research, but also to enhance your skills at reading original research published in academic journals. Beyond the basic academic style of report writing, there are specific, often unwritten assumptions about how quantitative, qualitative, and critical/rhetorical studies should be organized and the information they should contain. This chapter discusses how to present your results in writing, how to write accessibly, how to visualize data, and how to present your results in person.

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

Written Presentation of Results

Once you've gone through the process of doing communication research – using a quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical methodological approach – the final step is to communicate it.

The major style manuals (the APA Manual, the MLA Handbook, and Turabian) are very helpful in documenting the structure of writing a study, and are highly recommended for consultation. But, no matter what style manual you may use, there are some common elements to the structure of an academic communication research paper.

Title Page :

This is simple: Your Paper's Title, Your Name, Your Institutional Affiliation (e.g., University), and the Date, each on separate lines, centered on the page. Try to make your title both descriptive (i.e., it gives the reader an idea what the study is about) and interesting (i.e., it is catchy enough to get one's attention).

For example, the title, "The uncritical idealization of a compensated psychopath character in a popular book series," would not be an inaccurate title for a published study, but it is rather vague and exceedingly boring. That study's author fortunately chose the title, "A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight ," which is more precisely descriptive, and much more interesting (Merskin, 2011). The use of the colon in academic titles can help authors accomplish both objectives: a catchy but relevant phrase, followed by a more clear explanation of the article's topic.

In some instances, you might be asked to write an abstract, which is a summary of your paper that can range in length from 75 to 250 words. If it is a published paper, it is useful to include key search terms in this brief description of the paper (the title may already have a few of these terms as well). Although this may be the last thing your write, make it one of the best things you write, because this may be the first thing your audience reads about the paper (and may be the only thing read if it is written badly). Summarize the problem/research question, your methodological approach, your results and conclusions, and the significance of the paper in the abstract.

Quantitative and qualitative studies will most typically use the rest of the section titles noted below. Critical/rhetorical studies will include many of the same steps, but will often have different headings. For example, a critical/rhetorical paper will have an introduction, definition of terms, and literature review, followed by an analysis (often divided into sections by areas of investigation) and ending with a conclusion/implications section. Because critical/rhetorical research is much more descriptive, the subheadings in such a paper are often times not generic subheads like "literature review," but instead descriptive subheadings that apply to the topic at hand, as seen in the schematic below. Because many journals expect the article to follow typical research paper headings of introduction, literature review, methods, results, and discussion, we discuss these sections briefly next.

Introduction:

As you read social scientific journals (see chapter 1 for examples), you will find that they tend to get into the research question quickly and succinctly. Journal articles from the humanities tradition tend to be more descriptive in the introduction. But, in either case, it is good to begin with some kind of brief anecdote that gets the reader engaged in your work and lets the reader understand why this is an interesting topic. From that point, state your research question, define the problem (see Chapter One) with an overview of what we do and don't know, and finally state what you will do, or what you want to find out. The introduction thus builds the case for your topic, and is the beginning of building your argument, as we noted in chapter 1.

By the end of the Introduction, the reader should know what your topic is, why it is a significant communication topic, and why it is necessary that you investigate it (e.g., it could be there is gap in literature, you will conduct valuable exploratory research, or you will provide a new model for solving some professional or social problem).

Literature Review:

The literature review summarizes and organizes the relevant books, articles, and other research in this area. It sets up both quantitative and qualitative studies, showing the need for the study. For critical/rhetorical research, the literature review often incorporates the description of the historical context and heuristic vocabulary, with key terms defined in this section of the paper. For more detail on writing a literature review, see Appendix 1.

The methods of your paper are the processes that govern your research, where the researcher explains what s/he did to solve the problem. As you have seen throughout this book, in communication studies, there are a number of different types of research methods. For example, in quantitative research, one might conduct surveys, experiments, or content analysis. In qualitative research, one might instead use interviews and observations. Critical/rhetorical studies methods are more about the interpretation of texts or the study of popular culture as communication. In creative communication research, the method may be an interpretive performance studies or filmmaking. Other methods used sometimes alone, or in combination with other methods, include legal research, historical research, and political economy research.

In quantitative and qualitative research papers, the methods will be most likely described according to the APA manual standards. At the very least, the methods will include a description of participants, data collection, and data analysis, with specific details on each of these elements. For example, in an experiment, the researcher will describe the number of participants, the materials used, the design of the experiment, the procedure of the experiment, and what statistics will be used to address the hypotheses/research questions.

Critical/rhetorical researchers rarely have a specific section called "methods," as opposed to quantitative and qualitative researchers, but rather demonstrate the method they use for analysis throughout the writing of their piece.

Helping your reader understand the methods you used for your study is important not only for your own study's credibility, but also for possible replication of your study by other researchers. A good guideline to keep in mind is transparency . You want to be as clear as possible in describing the decisions you made in designing your study, gathering and analyzing your data so that the reader can retrace your steps and understand how you came to the conclusions you formed. A research study can be very good, but if it is not clearly described so that others can see how the results were determined or obtained, then the quality of the study and its potential contributions are lost.

After you completed your study, your findings will be listed in the results section. Particularly in a quantitative study, the results section is for revisiting your hypotheses and reporting whether or not your results supported them, and the statistical significance of the results. Whether your study supported or contradicted your hypotheses, it's always helpful to fully report what your results were. The researcher usually organizes the results of his/her results section by research question or hypothesis, stating the results for each one, using statistics to show how the research question or hypothesis was answered in the study.

The qualitative results section also may be organized by research question, but usually is organized by themes which emerged from the data collected. The researcher provides rich details from her/his observations and interviews, with detailed quotations provided to illustrate the themes identified. Sometimes the results section is combined with the discussion section.

Critical/rhetorical researchers would include their analysis often with different subheadings in what would be considered a "results" section, yet not labeled specifically this way.

Discussion:

In the discussion section, the researcher gives an appraisal of the results. Here is where the researcher considers the results, particularly in light of the literature review, and explains what the findings mean. If the results confirmed or corresponded with the findings of other literature, then that should be stated. If the results didn't support the findings of previous studies, then the researcher should develop an explanation of why the study turned out this way. Sometimes, this section is called a "conclusion" by researchers.

References:

In this section, all of the literature cited in the text should have full references in alphabetical order. Appendices: Appendix material includes items like questionnaires used in the study, photographs, documents, etc. An alphabetical letter is assigned for each piece (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B), with a second line of title describing what the appendix contains (e.g. Participant Informed Consent, or New York Times Speech Coverage). They should be organized consistently with the order in which they are referenced in the text of the paper. The page numbers for appendices are consecutive with the paper and reference list.

Tables/Figures:

Tables and figures are referenced in the text, but included at the end of the study and numbered consecutively. (Check with your professor; some like to have tables and figures inserted within the paper's main text.) Tables generally are data in a table format, whereas figures are diagrams (such as a pie chart) and drawings (such as a flow chart).

Accessible Writing

As you may have noticed, academic writing does have a language (e.g., words like heuristic vocabulary and hypotheses) and style (e.g., literature reviews) all its own. It is important to engage in that language and style, and understand how to use it to communicate effectively in an academic context . Yet, it is also important to remember that your analyses and findings should also be written to be accessible. Writers should avoid excessive jargon, or—even worse—deploying jargon to mask an incomplete understanding of a topic.

The scourge of excessive jargon in academic writing was the target of a famous hoax in 1996. A New York University physics professor submitted an article, " Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity ," to a special issue of the academic journal Social Text devoted to science and postmodernism. The article was designed to point out how dense academic jargon can sometimes mask sloppy thinking. As the professor, Alan Sokal, had expected, the article was published. One sample sentence from the article reads:

It has thus become increasingly apparent that physical "reality", no less than social "reality", is at bottom a social and linguistic construct; that scientific "knowledge", far from being objective, reflects and encodes the dominant ideologies and power relations of the culture that produced it; that the truth claims of science are inherently theory-laden and self-referential; and consequently, that the discourse of the scientific community, for all its undeniable value, cannot assert a privileged epistemological status with respect to counter-hegemonic narratives emanating from dissident or marginalized communities. (Sokal, 1996. pp. 217-218)

According to the journal's editor, about six reviewers had read the article but didn't suspect that it was phony. A public debate ensued after Sokal revealed his hoax. Sokal said he worried that jargon and intellectual fads cause academics to lose contact with the real world and "undermine the prospect for progressive social critique" ( Scott, 1996 ). The APA Manual recommends to avoid using technical vocabulary where it is not needed or relevant or if the technical language is overused, thus becoming jargon. In short, the APA argues that "scientific jargon...grates on the reader, encumbers the communication of information, and wastes space" (American Psychological Association, 2010, p. 68).

Data Visualization

Images and words have long existed on the printed page of manuscripts, yet, until recently, relatively few researchers possessed the resources to effectively combine images combined with words (Tufte, 1990, 1983). Communication scholars are only now becoming aware of this dimension in research as computer technologies have made it possible for many people to produce and publish multimedia presentations.

Although visuals may seem to be anathema to the primacy of the written word in research, they are a legitimate way, and at times the best way, to present ideas. Visual scholar Lester Faigley et al. (2004) explains how data visualizations have become part of our daily lives:

Visualizations can shed light on research as well. London-based David McCandless specializes in visualizing interesting research questions, or in his words "the questions I wanted answering" (2009, p. 7). His images include a graph of the peak times of the year for breakups (based on Facebook status updates), a radiation dosage chart , and some experiments with the Google Ngram Viewer , which charts the appearance of keywords in millions of books over hundreds of years.

The public domain image below creatively maps U.S. Census data of the outflow of people from California to other states between 1995 and 2000.

Visualizing one's research is possible in multiple ways. A simple technology, for example, is to enter data into a spreadsheet such as Excel, and select Charts or SmartArt to generate graphics. A number of free web tools can also transform raw data into useful charts and graphs. Many Eyes , an open source data visualization tool (sponsored by IBM Research), says its goal "is to 'democratize' visualization and to enable a new social kind of data analysis" (IBM, 2011). Another tool, Soundslides , enables users to import images and audio to create a photographic slideshow, while the program handles all of the background code. Other tools, often open source and free, can help visual academic research into interactive maps; interactive, image-based timelines; interactive charts; and simple 2-D and 3-D animations. Adobe Creative Suite (which includes popular software like Photoshop) is available on most computers at universities, but open source alternatives exist as well. Gimp is comparable to Photoshop, and it is free and relatively easy to use.

One online performance studies journal, Liminalities , is an excellent example of how "research" can be more than just printed words. In each issue, traditional academic essays and book reviews are often supported photographs, while other parts of an issue can include video, audio, and multimedia contributions. The journal, founded in 2005, treats performance itself as a methodology, and accepts contribution in html, mp3, Quicktime, and Flash formats.

For communication researchers, there is also a vast array of visual digital archives available online. Many of these archives are located at colleges and universities around the world, where digital librarians are spearheading a massive effort to make information—print, audio, visual, and graphic—available to the public as part of a global information commons. For example, the University of Iowa has a considerable digital archive including historical photos documenting American railroads and a database of images related to geoscience. The University of Northern Iowa has a growing Special Collections Unit that includes digital images of every UNI Yearbook between 1905 and 1923 and audio files of UNI jazz band performances. Researchers at he University of Michigan developed OAIster , a rich database that has joined thousands of digital archives in one searchable interface. Indeed, virtually every academic library is now digitizing all types of media, not just texts, and making them available for public viewing and, when possible, for use in presenting research. In addition to academic collections, the Library of Congress and the National Archives offer an ever-expanding range of downloadable media; commercial, user-generated databases such as Flickr, Buzznet, YouTube and Google Video offer a rich resource of images that are often free of copyright constraints (see Chapter 3 about Creative Commons licenses) and nonprofit endeavors, such as the Internet Archive , contain a formidable collection of moving images, still photographs, audio files (including concert recordings), and open source software.

Presenting your Work in Person

As Communication students, it's expected that you are not only able to communicate your research project in written form but also in person.

Before you do any oral presentation, it's good to have a brief "pitch" ready for anyone who asks you about your research. The pitch is routine in Hollywood: a screenwriter has just a few minutes to present an idea to a producer. Although your pitch will be more sophisticated than, say, " Snakes on a Plane " (which unfortunately was made into a movie), you should in just a few lines be able to explain the gist of your research to anyone who asks. Developing this concise description, you will have some practice in distilling what might be a complicated topic into one others can quickly grasp.

Oral presentation

In most oral presentations of research, whether at the end of a semester, or at a research symposium or conference, you will likely have just 10 to 20 minutes. This is probably not enough time to read the entire paper aloud, which is not what you should do anyway if you want people to really listen (although, unfortunately some make this mistake). Instead, the point of the presentation should be to present your research in an interesting manner so the listeners will want to read the whole thing. In the presentation, spend the least amount of time on the literature review (a very brief summary will suffice) and the most on your own original contribution. In fact, you may tell your audience that you are only presenting on one portion of the paper, and that you would be happy to talk more about your research and findings in the question and answer session that typically follows. Consider your presentation the beginning of a dialogue between you and the audience. Your tone shouldn't be "I have found everything important there is to find, and I will cram as much as I can into this presentation," but instead "I found some things you will find interesting, but I realize there is more to find."

Turabian (2007) has a helpful chapter on presenting research. Most important, she emphasizes, is to remember that your audience members are listeners, not readers. Thus, recall the lessons on speech making in your college oral communication class. Give an introduction, tell them what the problem is, and map out what you will present to them. Organize your findings into a few points, and don't get bogged down in minutiae. (The minutiae are for readers to find if they wish, not for listeners to struggle through.) PowerPoint slides are acceptable, but don't read them. Instead, create an outline of a few main points, and practice your presentation.

Turabian suggests an introduction of not more than three minutes, which should include these elements:

- The research topic you will address (not more than a minute).

- Your research question (30 seconds or less)

- An answer to "so what?" – explaining the relevance of your research (30 seconds)

- Your claim, or argument (30 seconds or less)

- The map of your presentation structure (30 seconds or less)

As Turabian (2007) suggests, "Rehearse your introduction, not only to get it right, but to be able to look your audience in the eye as you give it. You can look down at notes later" (p. 125).

Poster presentation

In some symposiums and conferences, you may be asked to present at a "poster" session. Instead of presenting on a panel of 4-5 people to an audience, a poster presenter is with others in a large hall or room, and talks one-on-one with visitors who look at the visual poster display of the research. As in an oral presentation, a poster highlights just the main point of the paper. Then, if visitors have questions, the author can informally discuss her/his findings.

To attract attention, poster presentations need to be nicely designed, or in the words of an advertising professor who schedules poster sessions at conferences, "be big, bold, and brief" ( Broyles , 2011). Large type (at least 18 pt.), graphics, tables, and photos are recommended.

A poster presentation session at a conference, by David Eppstein (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ( www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0 )], via Wikimedia Commons]

The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) has a template for making an effective poster presentation . Many universities, copy shops, and Internet services also have large-scale printers, to print full-color research poster designs that can be rolled up and transported in a tube.

Judging Others' Research

After taking this course, you should have a basic knowledge of research methods. There will still be some things that may mystify you as a reader of other's research. For example, you may not be able to interpret the coefficients for statistical significance, or make sense of a complex structural equation. Some specialized vocabulary may still be difficult.

But, you should understand how to critically review research. For example, imagine you have been asked to do a blind (i.e., the author's identity is concealed) "peer review" of communication research for acceptance to a conference, or publication in an academic journal. For most conferences and journals , submissions are made online, where editors can manage the flow and assign reviews to papers. The evaluations reviewers make are based on the same things that we have covered in this book. For example, the conference for the AEJMC ask reviewers to consider (on a five-point scale, from Excellent to Poor) a number of familiar research dimensions, including the paper's clarity of purpose, literature review, clarity of research method, appropriateness of research method, evidence presented clearly, evidence supportive of conclusions, general writing and organization, and the significance of the contribution to the field.

Beyond academia, it is likely you will more frequently apply the lessons of research methods as a critical consumer of news, politics, and everyday life. Just because some expert cites a number or presents a conclusion doesn't mean it's automatically true. John Allen Paulos, in his book A Mathematician reads the newspaper , suggests some basic questions we can ask. "If statistics were presented, how were they obtained? How confident can we be of them? Were they derived from a random sample or from a collection of anecdotes? Does the correlation suggest a causal relationship, or is it merely a coincidence?" (1997, p. 201).

Through the study of research methods, we have begun to build a critical vocabulary and understanding to ask good questions when others present "knowledge." For example, if Candidate X won a straw poll in Iowa, does that mean she'll get her party's nomination? If Candidate Y wins an open primary in New Hampshire, does that mean he'll be the next president? If Candidate Z sheds a tear, does it matter what the context is, or whether that candidate is a man or a woman? What we learn in research methods about validity, reliability, sampling, variables, research participants, epistemology, grounded theory, and rhetoric, we can consider whether the "knowledge" that is presented in the news is a verifiable fact, a sound argument, or just conjecture.

American Psychological Association (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Broyles, S. (2011). "About poster sessions." AEJMC. http://www.aejmc.org/home/2013/01/about-poster-sessions/ .

Faigley, L., George, D., Palchik, A., Selfe, C. (2004). Picturing texts . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

IBM (2011). Overview of Many Eyes. http://www.research.ibm.com/social/projects_manyeyes.shtml .

McCandless, D. (2009). The visual miscellaneum . New York: Collins Design.

Merskin, D. (2011). A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight. Journal of Communication Inquiry 35: 157-178. doi:10.1177/0196859911402992

Paulos, J. A. (1997). A mathematician reads the newspaper . New York: Anchor.

Scott, J. (1996, May 18). Postmodern gravity deconstructed, slyly. New York Times , http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/11/15/specials/sokal-text.html .

Sokal, A. (1996). Transgressing the boundaries: towards a transformative hermeneutics of quantum gravity. Social Text 46/47, 217-252.

Tufte, E. R. (1990). Envisioning information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Tufte, E. R. (1983). The visual display of quantitative information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Turabian, Kate L. (2007). A manual for writers of research papers, theses, and dissertations: Chicago style guide for students and researchers (7th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

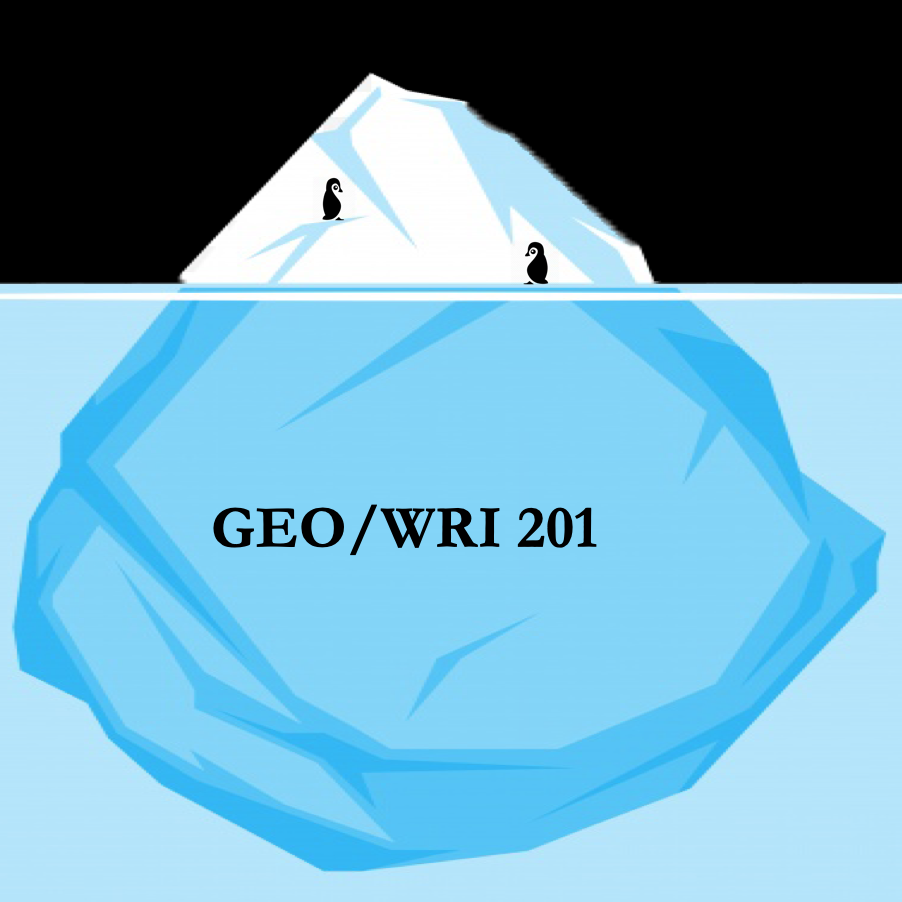

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Research Guide

Chapter 7 presenting your findings.

Now that you have worked so hard in your project, how to ensure that you can communicate your findings in an effective and efficient way? In this section, I will introduce a few tips that could help you prepare your slides and preparing for your final presentation.

7.1 Sections of the Presentation

When preparing your slides, you need to ensure that you have a clear roadmap. You have a limited time to explain the context of your study, your results, and the main takeaways. Thus, you need to be organized and efficient when deciding what material will be included in the slides.

You need to ensure that your presentation contains the following sections:

- Motivation : Why did you choose your topic? What is the bigger question?

- Research question : Needs to be clear and concise. Include secondary questions, if available, but be clear about what is your research question.

- Literature Review : How does your paper fit in the overall literature? What are your contributions?

- Context : Give an overview of the issue and the population/countries that you analyzed

- Study Characteristics : This section is key, as it needs to include your model, identification strategy, and introduce your data (sources, summary statistics, etc.).

- Results : In this section, you need to answer your research question(s). Include tables that are readable.

- Additional analysis : Here, include any additional information that your public needs to know. For instance, did you try different specifications? did you find an obstacle (i.e. your data is very noisy, the sample is very small, something else) that may bias your results or create some issues in your analysis? Tell your audience! No research project is perfect, but you need to be clear about the imperfections of your project.

- Conclusion : Be repetitive! What was your research question? How did you answer it? What did you find? What is next in this topic?

7.2 How to prepare your slides

When preparing your slides, remember that humans have a limited capacity to pay attention. If you want to convey your convey your message in an effective way, you need to ensure that the message is simple and that you keep your audience attention. Here are some strategies that you may want to follow:

- Have a clear roadmap at the beginning of the presentation. Tell your audience what to expect.

- Number your slides. This will help you and your audience to know where you are in your analysis.

- Ensure that each slide has a purpose

- Ensure that each slide is connected to your key point.

- Make just one argument per slide

- State the objective of each slide in the headline

- Use bullet points. Do not include more than one sentence per bullet point.

- Choose a simple background.

- If you want to direct your audience attention to a specific point, make it more attractive (using a different font color)

- Each slide needs to have a similar structure (going from the general to the particular detauls).

- Use images/graphs when possible. Ensure that the axes for the graphs are clear.

- Use a large font for your tables. Keep them as simple as possible.

- If you can say it with an image, choose it over a table.

- Have an Appendix with slides that address potential questions.

7.3 How to prepare your presentation

One of the main constraints of having simple presentations is that you cannot rely on them and read them. Instead, you need to have extra notes and memorize them to explain things beyond what is on your slides. The following are some suggestions on how to ensure you communicate effectively during your presentation.

- Practice, practice, practice!

- Keep the right volume (practice will help you with that)

- Be journalistic about your presentation. Indicate what you want to say, then say it.

- Ensure that your audience knows where you are going

- Avoid passive voice.

- Be consistent with the terms you are using. You do not want to confuse your audience, even if using synonyms.

- Face your audience and keep an eye contact.

- Do not try reading your slides

- Ensure that your audience is focused on what you are presenting and there are no other distractions that you can control.

- Do not rush your presentation. Speak calmly and controlled.

- Be comprehensive when answering questions. Avoid yes/no answers. Instead, rephrase question (to ensure you are answering the right question), then give a short answer, then develop.

- If you lose track, do not panick. Go back a little bit or ask your audience for assistance.

- Again, practice is the secret.

You have worked so hard in your final project, and the presentation is your opportunity to share that work with the rest of the world. Use this opportunity to shine and enjoy it.

Since this is the first iteration of the Guide, I expect that there are going to be multiple typos and structure issues. Please feel free to let me know, and I will correct accordingly. ↩︎

Note that you would still need to refine some of the good questions even more. ↩︎

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Presentations: Oral Presentations

- Poster Design

- Poster Content

- Poster Presentation

- Oral Presentations

- Printing & Archiving

Oral Presentations Purpose

An Oral Research Presentation is meant to showcase your research findings. A successful oral research presentation should: communicate the importance of your research; clearly state your findings and the analysis of those findings; prompt discussion between researcher and audience. Below you will find information on how to create and give a successful oral presentation.

Creating an Effective Presentation

Who has a harder job the speaker? Or, the audience?

Most people think speaker has the hardest job during an oral presentation, because they are having to stand up in a room full of people and give a presentation. However, if the speaker is not engaging and if the material is way outside of the audiences knowledge level, the audience can have a difficult job as well. Below you will find some tips on how to be an effective presenter and how to engage with your audience.

Organization of a Presentation

Introduction/Beginning

How are you going to begin? How are you going to get the attention of your audience? You need to take the time and think about how you are going to get started!

Here are some ways you could start:

- Ask the audience a question

- make a statement

- show them something

No matter how you start your presentation it needs to relate to your research and capture the audiences attention.

Preview what you are going to discuss . Audiences do not like to be manipulated or tricked. Tell the audience exactly what you are going to discuss, this will help them follow along. *Do not say you are going to cover three points and then try to cover 8 points.

At the end of your introduction, the audience should feel like they know exactly what you are going to discuss and exactly how you are going to get there.

Body/Middle

Conclusion/End

Delivery and Communication

Eye Contact

Making eye contact is a great way to engage with your audience. Eye contact should be no longer than 2-3 seconds per person. Eye contact for much longer than that can begin to make the audience member feel uncomfortable.

Smiling lets attendees know you are happy to be there and that you are excited to talk with them about your project.

We all know that body language says a lot, so here are some things you should remember when giving your presentation.

- Stand with both feet on the floor, not with one foot crossed over the other.

- Do not stand with your hands in your pockets, or with your arms crossed.

- Stand tall with confidence and own your space (remember you are the expert).

Abbreviated Notes

Having a written set of notes or key points that you want to address can help prevent you from reading the poster.

Speak Clearly

Sometimes when we get nervous we begin to talk fast and blur our words. It is important that you make sure every word is distinct and clear. A great way to practice your speech is to say tongue twisters.

Ten tiny tots tottered toward the shore

Literally literary. Literally literary. Literally literary.

Sally soon saw that she should sew some sheets.

Avoid Fillers

Occasionally we pick up fillers that we are not aware of, such as um, like, well, etc. One way to get rid of fillers is to have a friend listen to your speech and every time you say a "filler" have that friend tap you on the arm or say your name. This will bring the filler to light, then you can practice avoiding that filler.

Manage Anxiety

Many people get nervous when they are about to speak to a crowd of people. Below are ways that you can manage your anxiety levels.

- Practice, Practice, Practice - the more prepared you are the less nervous you will be.

- Recognize that anxiety is just a big shot of adrenalin.

- Take deep breaths before your presentation to calm you down.

Components of an Oral Research Presentation

Introduction

The introduction section of your oral presentation should consist of 3 main parts.

Part 1: Existing facts

In order to give audience members the "full picture", you first need to provide them with information about past research. What facts already exist? What is already known about your research area?

Part 2: Shortcomings

Once you have highlighted past research and existing facts. You now need to address what is left to be known, or what shortcomings exist within the current information. This should set the groundwork for your experiment. Keep in mind, how does your research fill these gaps or help address these questions?

Part 3: Purpose or Hypothesis

After you have addressed past/current research and have identified shortcomings/gaps, it is now time to address your research. During this portion of the introduction you need to tell viewers why you are conducting your research experiement/study, and what you hope to accomplish by doing so.

In this section you should share with your audience how you went about collecting and analyzing your data

Should include:

- Participants: Who or what was in the study?

- Materials/ measurements: what did you measure?

- Procedures: How did you do the study?

- Data-analysis: What analysis were conducted?

This section contains FACTS – with no opinion, commentary or interpretation. Graphs, charts and images can be used to display data in a clear and organized way.

Keep in mind when making figures:

- Make sure axis, treatments, and data sets are clearly labeled

- Strive for simplicity, especially in figure titles.

- Know when to use what kind of graph

- Be careful with colors.

Interpretation and commentary takes place here. This section should give a clear summary of your findings.

You should:

- Address the positive and negative aspects of you research

- Discuss how and if your research question was answered.

- Highlight the novel and important findings

- Speculate on what could be occurring in your system

Future Research

- State your goals

- Include information about why you believe research should go in the direction you are proposing

- Discuss briefly how you plan to implement the research goals, if you chose to do so.

Why include References?

- It allows viewers to locate the material that you used, and can help viewers expand their knowledge of your research topic.

- Indicates that you have conducted a thorough review of the literature and conducted your research from an informed perspective.

- Guards you against intellectual theft. Ideas are considered intellectual property failure to cite someone's ideas can have serious consequences.

Acknowledgements

This section is used to thank the people, programs and funding agencies that allowed you to perform your research.

Questions

Allow for about 2-3 minutes at the end of your presentation for questions.

It is important to be prepared.

- Know why you conducted the study

- Be prepared to answer questions about why you chose a specific methodology

If you DO NOT know the answer to a question

Visual Aids

PowerPoints and other visual aids can be used to support what you are presenting about.

Power Point Slides and other visual aids can help support your presentation, however there are some things you should consider:

- Do not overdo it . One big mistake that presenters make is they have a slide for every single item they want to say. One way you can avoid this is by writing your presentation in Word first, instead of making a Power Point Presentation. By doing this you can type exactly what you want to say, and once your presentation is complete, you can create Power Point slides that help support your presentation.

Formula for number of visual aids : Length of presentation divided by 2 plus 1

example: 12 minute presentation should have no more than 7 slides.

- Does it add interest?

- Does it prove?

- Does it clarify?

- Do not read the text . Most people can read, and if they have the option of reading material themselves versus listen to you read it, they are going to read it themselves and then your voice becomes an annoyance. Also, when you are reading the text you are probably not engaging with the audience.

- No more than 4-6 lines on a slide and no more than 4-6 words in a line.

- People should be able to read your slide in 6 seconds.

- << Previous: Poster Presentation

- Next: Printing & Archiving >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/c.php?g=637469

Research presentation: A comprehensive guide

Learn how to choose a topic, conduct research, create visuals, and deliver your presentation with confidence.

Raja Bothra

Building presentations

Hey there, fellow knowledge seekers!

Today, we're diving deep into the world of research presentations.

Whether you're a student gearing up for your undergraduate research showcase or a professional preparing for a crucial job interview, mastering the art of delivering an effective research presentation is a valuable skill.

What is a research presentation?

A research presentation is a means to communicate your findings, insights, and discoveries to an audience, be it in a classroom, at a conference, or in a boardroom. It's your opportunity to showcase your expertise and share the results of your hard work.

Purpose of a research presentation

Before we dive into the intricacies of creating a stellar research presentation, let's explore the underlying reasons that make these presentations indispensable. The purpose of a research presentation is not merely to present data but to serve as a powerful tool for communication and engagement.

Sharing knowledge

At its core, a research presentation is a conduit for sharing knowledge, disseminating your research findings, and illuminating the uncharted realms of your work. It's about taking the complex and making it comprehensible, even captivating.

Academic evaluation

In the realm of academia, research presentations play a pivotal role in the evaluation process. They are your platform to defend a dissertation or thesis with vigor and confidence. Moreover, they are your plea for research funding, where your passion and precision could tip the scales in your favor.

Professional communication

Beyond the academic sphere, research presentations find a home in the corporate world, such as job interview s. In these scenarios, your presentation serves as a bridge, connecting your ideas with potential employers. It's an opportunity to demonstrate not just your research skills but also your ability to communicate them effectively.

The bigger picture

Your research presentation is more than just slides and data; it's an embodiment of your dedication and expertise. It's a tool for persuading, inspiring, and inciting action. It's a gateway to engage, educate, and advocate, whether in academic circles, professional settings, or public platforms.

A universal canvas

Regardless of the context, the core objectives of a research presentation remain constant:

- Dissemination of information : Sharing insights and discoveries for the collective advancement of knowledge.

- Engagement : Creating a presentation that captivates and effectively conveys complex ideas.

- Feedback and discussion : Welcoming questions, feedback, and discussions that refine and expand your research.

- Peer review : Serving as part of the peer-review process in academia, where experts evaluate the quality and validity of your work.

- Educational : Actively contributing to education by disseminating valuable information about a particular topic or research area.

- Persuasion : In cases like grant applications, presentations aim to persuade the audience to support or fund the research project.

- Networking : An opportunity to connect with peers, professionals, and stakeholders interested in your field.

- Professional development : A chance to enhance your communication skills and professional development.

- Public awareness : Raising public awareness about significant issues or findings that have a direct impact on society.

Your research presentation is not merely a sequence of slides but a powerful tool for communication and connection. Whether you're in the academic realm, the corporate world, or the public sphere, your ability to convey your research clearly and engagingly is pivotal to your success. Remember, you're not just presenting data; you're sharing knowledge, engaging your audience, and advocating for a cause.

Different types of research presentation

Research presentations are as diverse as the research itself, and the choice of presentation format is crucial. It depends on factors like the audience, the research's nature, and the specific goals of the presentation. Let's explore the myriad forms research presentations can take:

1. Oral presentations

- Conference presentations : These formal presentations are typically held at academic conferences, where researchers present their findings to a specialized audience. It's a platform for in-depth discussions and peer feedback.

- Seminar presentations : Often conducted at universities or research institutions, these presentations delve deep into research topics, encouraging detailed discussions and expert insights.

- Lecture series : A series of lectures focused on a particular research topic, usually organized by universities. These sessions offer a comprehensive exploration of a subject.

2. Poster presentations

- Conference posters : Visual presentations of research findings displayed on large posters, commonly used at academic conferences. They provide a snapshot of research, making complex data more accessible.

- Academic fairs : Frequently used to showcase research projects at the undergraduate or high school level. These exhibitions make research engaging for students.

3. Online/webinar presentations

- Webinars : Online presentations where researchers share their work with a remote audience. These presentations often include interactive elements, like Q&A sessions.

- Online workshops : Hands-on, interactive presentations that teach research methodologies or specific skills. Ideal for engaging the audience in a virtual setting.

4. Thesis or dissertation defense: Researchers defend their doctoral or master's theses or dissertations before a committee. It involves explaining their research in-depth and responding to questions.

5. Ignite or pecha kucha presentations : These are fast-paced presentations where presenters use a fixed number of slides and limited time per slide to convey their research succinctly. It's a dynamic format that encourages clarity and conciseness.

6. Panel discussions: Researchers participate in a discussion alongside other experts, sharing their perspectives on a specific topic

or research area. These discussions provide a well-rounded view of the subject.

7. TED talks or public lectures: Researchers present their work to a general audience in an engaging and accessible manner. The focus is on making complex ideas understandable and captivating.

8. Corporate research presentations: Researchers may present their findings to colleagues, executives, or stakeholders in a business or industry setting. These presentations often have practical applications and implications for the company.

9. Pitch presentations: Researchers may need to pitch their research project to potential funders , collaborators, or sponsors. This format requires the ability to convey the research's value and potential impact effectively.

10. Media interviews: Researchers can present their work through interviews with journalists, on television, radio, podcasts, or in written articles. The challenge here is to convey complex ideas to a broad audience.

11. Educational workshops: These presentations occur in an educational context, where researchers teach others about a particular subject or research method. It's a way to transfer knowledge and skills effectively.

12. Research reports: These formal written reports communicate research findings and are presented in a document format. They are often used for thorough documentation and publication.

13. Interactive exhibits: Researchers create interactive exhibits at science centers or museums to engage the public with their research. It's about making research accessible and engaging to a wide audience.

14. Government or policy briefings: Researchers may present their work to policymakers, helping to inform decision-making. These presentations have a direct impact on policy and require clarity and relevance.

15. Peer review: In the academic realm, researchers present their work to a group of peers for constructive feedback before formal publication. It's an essential step in ensuring the quality and validity of research.

In the world of research presentations, adaptability is key. Researchers often need to tailor their content and style to suit the context and meet the expectations of their audience. Remember, the choice of presentation type should align with your goals and the nature of your research. Each format has its unique strengths and is a valuable tool for sharing knowledge, engaging your audience, and achieving your research objectives.

What should a research presentation include?

A research presentation is not just a random assortment of slides; it's a meticulously crafted narrative that informs, engages, and inspires. Regardless of the type of presentation you opt for, there are some indispensable components to consider:

Introduction: Your presentation journey begins with the introduction—a compelling opening act. This is where you introduce your topic, explain its significance, and clearly state your research question or hypothesis. Think of it as setting the stage for the story you're about to tell.

Background: The background section is your opportunity to equip your audience with the necessary context to grasp the intricacies of your research. This may encompass discussions on relevant theories, prior research, and fundamental concepts that lay the foundation for your work. It's about ensuring your audience starts on the same page.

Methodology: This section provides an insight into the "how" of your research. Share the methods you employed in conducting your research, such as data collection techniques, sampling procedures, and your chosen methods of analysis. It's a backstage pass to the mechanics of your study.

Results: With the methodology unveiled, it's time to present the star of the show—your findings. This section is where you shine a spotlight on your results, delivering them in a clear and concise manner. Visual aids, such as tables, graphs, and other visuals, can be invaluable allies in communicating your results effectively.

Discussion: As you transition from presenting results, you enter the realm of interpretation and discussion. Here, you dissect your findings, analyzing their implications and discussing their real-world significance. Don't forget to address the limitations of your study and suggest future research directions.

Conclusion: In the grand finale of your presentation, it's time to bring the pieces together. Summarize your main points, reiterate the importance of your research, and leave your audience with a lasting impression. A compelling conclusion can be the key to a memorable presentation.

Q&A session: Your presentation isn't just a monologue; it's a dialogue with your audience. Provide an opportunity for engagement and clarification through a Q&A session. Allow your audience to ask questions, offer feedback, and explore the nuances of your research.

Contact information: Consider including a slide with your contact information. This way, curious audience members can reach out to you with questions, feedback, or collaboration opportunities. It's a subtle but essential way to maintain the conversation beyond the presentation.

It's important to note that the specific content and length of your research presentation may vary based on your audience and time constraints. For instance, if your audience is general and diverse, dedicating more time to background and discussion can enhance comprehension. On the other hand, when presenting to experts in your field, you can streamline these sections and focus on the intricate details of your methodology and results.

How to structure an effective research presentation

Crafting an effective research presentation is akin to weaving a compelling narrative. It's about captivating your audience while imparting knowledge. Here's a step-by-step guide on how to structure a presentation that leaves a lasting impression:

Title slide : Your presentation begins with the title slide, your first impression. Include the title of your presentation, your name, affiliation, and the date. This slide sets the stage for your audience, providing essential information about what they are about to learn.

Introduction : The introduction is your opportunity to grab your audience's attention and set the stage for your presentation. Start with a hook, like a thought-provoking question, a surprising fact, or even a touch of humor if it fits naturally. Additionally, in the introduction, provide background and context for your research, clearly state your research question or objectives, and explain why your research is important or relevant.

Literature review : In this section, briefly summarize key research in your field related to your topic. Highlight gaps or areas where your research contributes. If relevant, mention theories or models that underpin your work, demonstrating your understanding of the existing body of knowledge.

Methodology : Explain the nuts and bolts of your research methods. Share the methods you used, whether they were surveys, experiments, case studies, or any other approach. Include details of data collection procedures, sample size, and data analysis techniques. If ethical considerations played a role, mention them here.