- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

Fascinating, mysterious 'intimacies' doesn't let readers get close enough.

Leland Cheuk

The unnamed heroine of Intimacies , Katie Kitamura's fascinating and mysterious new novel, observes that "none of us are able to see the world we are living in — the world, occupying as it does the contradiction between its banality ... and its extremity." She's a new interpreter at The Hague, responsible for the banal function of translating legal proceedings for extremely evil defendants: genocidal former heads of state.

We know only that the narrator came to The Hague by way of New York, her father has just died after a long illness, and her mother has returned to Singapore. Even her age and ethnicity are murky and, strangely, rarely commented upon. Kitamura seems to intentionally test the boundaries of how little biographical information an author can reveal about a protagonist while still making the reader feel intimately connected to them.

Readers will get a sense of both the importance and the futility of the International Criminal Court. The narrator points out that the Court primarily prosecutes crimes against humanity in African nations, becoming an "ineffectual" instrument of "Western imperialism." Of the building that the Court is housed in, the narrator observes "the modern architecture still seemed incongruous, perhaps even lacking the authority I had expected."

Author Interviews

Kitamura is out with another novel that transcends languages and borders.

Fires Burn — At A Distance — In Unnerving 'Separation'

When the narrator must interpret for an African head of state accused of enforcing Sharia law and numerous crimes related to the persecution of women, Kitamura portrays the accused's intake process as an hours-long exercise in bureaucratic drudgery. The narrator dryly observes, "I even forgot who I was waiting for, only that I was waiting for someone who might never arrive, and that I might never leave this vestibule." The accused and the narrator develop a Hannibal Lecter/Clarice Starling dynamic, with the narrator simultaneously drawn to and repulsed by the accused's remorselessness.

Outside of work, the narrator wants what anyone moving alone to a new city wants: friendship and love. She gets involved with Adriaan, a married father finalizing a divorce. Not long after they meet, however, he leaves for Portugal. The narrator can't tell whether he's gone to rekindle his marriage or work out the terms of the separation. While she stays in Adriaan's apartment alone for weeks on end, their relationship reduced to a series of infrequent and terse texts, her insecurities grow.

While Adriaan is gone, the narrator develops a fascination with an elegant art historian named Eline and her charismatic, disabled brother Anton. The narrator's description of her profession mirrors her interactions with these new friends: "We interpreters were only extras passing behind the central cast and yet moved with caution, we had a sense of being under observation." Kitamura casts the narrator as an extra in the lives of Adriaan, Eline, Anton, and others. They are named; she is not. And yet, the narrator is the character we're supposed to feel most intimate with. We observe her actively hiding herself, as she reveals every thought and feeling with an abundance of discretion. She's so circumspect that I started to wonder: What exactly did Adriaan and others find alluring about her?

Inside the crucible of a war crimes trial and a relationship that seems doomed, the mysterious narrator gradually breaks down. When her boss at The Hague offers to renew her contract, she demurs and begins to cry there on the spot. Her loss of restraint feels like a major moment in the book, but why? Is she finally coming to terms with her father's passing, her mother's abandonment, Adriaan's desertion, her inability to develop lasting friendships in a new city, or all or some of the above?

I couldn't help but crave a more open, incautious narrator, someone who is more than, as the accused puts it, "part of the institution that [she] serve[s]." The novel effectively comments on the elusiveness of intimacy, but perhaps at the cost of the reader's emotional connection to the narrator. How much of what is factually revealed helps one understand a situation — or a person — more intimately? Even the journalists covering the International Criminal Court "had merely fragments of the narrative and yet they would assemble those fragments into a story like any other story, a story with the appearance of unity." Kitamura's novel has its own appearance of unity, but ultimately illustrates how one's interpretations can fail to help them see the world in which they live.

Leland Cheuk is an award-winning author of three books of fiction, most recently No Good Very Bad Asian. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle and Salon , among other outlets.

- print archive

- digital archive

- book review

[types field='book-title'][/types] [types field='book-author'][/types]

Riverhead, 2021

Contributor Bio

More online by greg chase.

- The Guest Lecture

- The Colonel’s Wife

- See What I Have Done

by Katie Kitamura

Reviewed by greg chase.

With Intimacies, her fourth novel, Katie Kitamura cements her status as one of contemporary fiction’s most controlled and perceptive writers, particularly when it comes to ambiguities of language and the risks of miscommunication. The novel’s unnamed first-person narrator has just moved to The Hague, where she works as an interpreter for a court clearly based on (though never explicitly identified as) the International Criminal Court. Her job is to translate testimony from one language into another in real time. As she recognizes, there’s something inherently contradictory about this work: legal proceedings demand “extreme precision,” whereas “great chasms” exist between the expressive possibilities of one language and those of another. The narrator is meant to be an “instrument” who facilitates legal proceedings, but her turns of phrase, as well as her affect and tone, can influence the outcome of a trial.

The novel hits its stride about a third of the way through, when the narrator is assigned to work with a team of lawyers defending an unspecified West African country’s ex-president, who has been accused of ethnic cleansing after a contested election. The accused comes off as scornful of the court and bored by the deliberations of his defense team, yet oddly attuned to the narrator’s presence. He frequently “nod[s]” at her during court sessions, “[a]s if to recognize the work that I performed.”

Meanwhile, the narrator struggles to find her footing in The Hague. She has one friend, a curator of Serbian-Ethiopian descent, and she is in a relationship with a married man who may or may not be in the process of separating permanently from his wife. We learn little about the narrator’s past, other than the fact that her father is dead, she is an only child, and her mother, with whom she is “not in the habit of regularly speaking,” now lives in Singapore. She has “native fluency in English and Japanese from my parents, and in French from a childhood in Paris.”

Through this dislocated narrator, Kitamura offers a fresh take on the relationship between the personal and the political. Set during the run-up to the Brexit referendum—and with concerns about the American presidential election hovering in the background— Intimacies explores how far one should seek to understand proponents of isolationism and intolerance. (At one point, during a commotion in the courtroom, the judge sternly instructs the former president, “ Please control your supporters, ” a line that will resonate with readers in chilling new ways after the events of January 6, 2021.)

In Kitamura’s hands, the narrator’s cosmopolitanism shades into moral relativism, a constitutional inability to make strong judgments or take decisive action. She is quick to recognize legitimate criticisms of the court, such as the fact that it “had primarily investigated and made arrests in African countries, even as crimes against humanity proliferated around the world.” More troublingly, she finds herself secretly rooting for the former president, “flinch[ing] when the proceedings seemed to go against him,” feeling that “of all the people in the city [ … ] [he] was the person I knew best.” It is as though the numerous languages she hears spoken around her have crowded out her sense of self.

Intimacies has its shortcomings. The scenes outside the court, which typically consist of the narrator having dinner or attending some sort of event with one of the novel’s secondary characters, can drag. Despite the intriguing political and philosophical questions it raises, Intimacies focuses on a relatively small group of cultured, upper-middle class characters and shows only a cursory interest in portraying other elements of Dutch society.

But Kitamura has a real gift for tone. She infuses seemingly mundane events—staying in someone else’s apartment, encountering the same person in two different contexts—with a powerful sense of dread. She calls to mind W. G. Sebald in her portrayal of the finite nature of human perspective as a kind of chronic confusion, a thick and inescapable “cloud of unknowing.”

Intimacies looks back on the political and cultural chaos of the last decade and wonders what kinds of epistemological and moral certainties remain available to us. It is more concerned with raising these questions than with attempting to offer clear answers; it is, in other words, a successful novel: subtle, carefully constructed, and not easily reducible to any kind of coherent political position.

Published on October 26, 2021

Like what you've read? Share it!

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Katie Kitamura Writes a World Ruled by Charisma

There is something decidedly unintimate about calling a novel “Intimacies.” The refusal to specify (what, whose) feels like a hedge. And yet “ Intimacies ,” by the author Katie Kitamura, achieves a kind of truth in advertising. Kitamura pursues various definitions of the word: knowledge of, closeness with, closeness to. At times, intimacy suggests friendship—a nearness of hearts—and other times merely precision, a nearness in sense, or proximity, a nearness in space. These forms of closeness want to bleed together, and characters sweat to keep them straight, to be close to one another in the “right” ways. The result is a rich, novelistic portrait of an abstraction.

The book, Kitamura’s fourth, follows an unnamed woman who has left New York—having lost her father, to a long illness—and come to The Hague, for work. She speaks in an unadorned first person, and reveals an acute but incomplete grasp of her surroundings. “I was surprised by how easily and frequently I lost my bearings,” she says, sounding like Sebald, another perceptive emigrant. (Her intelligence and sense of dissociation have the same uncanny quality of reinforcing each other.) The woman’s affect is also the novel’s: haunted, unstable, and intermittently hopeful. (“I had begun looking for something, although I didn’t know exactly what.”) Partway through the book, the narrator’s new boyfriend, Adriaan, decamps to Lisbon to finalize his divorce; she moves into his enviable apartment, and weeks pass with no word from him. Meanwhile, she begins to spend time with an art historian whose twin brother was mugged and brutally beaten. The assault occurred recently, in another friend’s neighborhood, and all three—the siblings and the friend—seem thrown, viscerally transformed. The narrator studies them with empathy and a quiet interest, as if their behavior contained an answer to the puzzle of violence, how it changes the course of things, how its consequences linger.

The narrator, it emerges, has a professional as well as a personal stake in these questions. She works as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court, where her “daily activity,” she says, hinges on the “description, elaboration, delineation” of horrors. Shortly after Adriaan leaves, she is assigned to the trial of a former President, also unnamed, who stands accused of war crimes. (He is partially modelled on Charles Taylor , the former President of Liberia; that the I.C.C. seems to prosecute with particular zeal evildoers from nonwhite countries is not lost on Kitamura.) The narrator, although supremely competent, does not always relish her job. It makes her feel permeable, open like a ramshackle house to the drafts of others’ moods and desires, and aspiring to perfect technical fidelity robs her of understanding.“You can be so caught up in the minutiae” of interpretation, she explains, “that you do not necessarily apprehend the sense of the sentences themselves: you literally do not know what you are saying.”

In Kitamura’s books, career is frequently a metonym for character. “ A Separation ,” her previous novel, featured a narrator who was also a translator (albeit of literature) and who exhibits a translator’s apparent passivity. At one point, she reproduces a soliloquy from her husband on professional mourners , who are paid to weep and wail at funerals in Greece. “You, the bereaved, are completely liberated from the need to emote,” the husband had said. “You purchase an instrument to express your sorrow, or perhaps it’s less like an instrument and more like a tape recorder and tape, you simply press play.” The narrator in “A Separation” seems enthralled by this system of surrogate feeling, and, in “Intimacies,” we find her counterpart trapped in its gears. At work, something nauseating has happened: the former President has taken a shine to her. She suspects his favor might relate to her soothing blankness, the way her subjectivity yields to others’. “I was pure instrument,” she thinks, “someone without will or judgment, a consciousness-free zone into which he could escape, the only company he could now bear.”

If passivity was an occupational hazard for the protagonist of “A Separation,” complicity is a problem for her successor. Her profession is to be a professional—to encase the monstrous in bureaucracy and expertise—and although this has not dulled her emotions it does dictate where and how she feels them. (She remembers being “startled” by the “unmeasured” tones of lawyers arguing about hideous crimes.) Kitamura devotes much more time in her new book to the narrator’s vocation, which is portrayed as subtle and dynamic, demanding exactitude, improvisation, and a flair for pressing artifice into the service of truth. There are many novels about women looking for agency, but agency, “Intimacies” wants to insist, is unavoidable. As the judicial setting highlights, accountability—others’ and one’s own—proves the more elusive quarry.

One point of intersection between the exercise of agency and the evasion of accountability might be charisma. Kitamura’s narrators, perhaps because they are outwardly unassuming, tend to fixate on this quality, greedily parsing the advantages it confers. (Because we see the world through their eyes, the books themselves feel exquisitely attuned to performance; all of human affairs can seem to run on currents of attraction and repulsion.) In “Intimacies,” the former President has an aura of force and elegance, a smooth attentiveness, but he is just one mesmerizing figure in a story lousy with them. It is implied that the trial’s defense attorney and even Adriaan are coasting on their handsomeness. (In fact, many of the book’s male characters could pass for Christopher, the husband in “A Separation,” who “risked spreading his charm thin.”) As the book proceeds, this wary diagnosing of magnetism becomes a sort of narrative tic. The victim of the mugging has features that are “primal” and “memorable,” exuding “some dark charisma.” A young warlord evinces “a dazzling air of command.” And Adriaan’s wife, when she shows up, is—inevitably—“improbably beautiful and also highly polished, as if she lived in continual expectation of being observed.”

There is a whiff of courting the reader to this study of star power. By dwelling on others’ seductiveness, the narrator presents herself as relatively guileless and likably average. But one struggles not to notice that many of the book’s characters seem drawn irresistibly to her . There’s the dictator, for one. There’s Adriaan, who asks for the narrator’s phone number within a few minutes of meeting her, and, several months later, invites her to live in his home. The defense attorney tries to pick her up three times. The sister of the mugging victim converses briefly with her at a gallery event and then, smitten, e-mails a mutual friend, requesting to be put in touch.

I thought here of the psychological phenomenon called “ egocentric bias ,” which causes people to overestimate the degree to which others’ perceptions resemble their own. One effect of the bias, as the researcher Vanessa Bohns has demonstrated, is that we tend to downplay the pressures we place on those around us. In “Intimacies,” the narrator’s own power and persuasiveness seem veiled to her. This deepens Kitamura’s theme of accountability—we don’t take responsibility for things we don’t realize we’ve done—but, to me, it also creates a crack in the storytelling. “Intimacies,” like “A Separation,” is explicitly about closeness and distance, drawing together and pulling apart. Kitamura depicts these processes as strikingly physical, as if governed by literal magnetism—the tug of a man’s charm, the repellency of his deceit, the way a friend’s misfortune can both beckon and paralyze you. But, in a novel about seeking the correct calibration for various relationships (the narrator senses herself to be too separate from Adriaan, not separate enough from the dictator), placing so much weight on invisible influences elides the role of decisions, discretion, and judgment, reducing a complex dance of personalities to a game of positive and negative charges. It can feel as though Kitamura’s fascination with beauty exists in tension with the book’s richest theme: how we decide how close we get.

“Intimacies” is not a shallow novel, but it is, finally, a deep and layered novel about superficiality. One of my favorite moments takes place in the courtroom, after proceedings have ended for the day, when the narrator catches a glimpse of the dictator. “His shoulders slumped and he suddenly appeared much older,” she says. “I realized it must have taken him great effort to appear before the Court with his posture so erect, his bearing still presidential, to marshal what charisma remained, because contrary to popular belief, charisma was not inherent but had to be constantly reinforced.” For an instant, magnetism is doxxed, revealed as theatre, and the relief is that of leaving a brilliantly overlit room. But the implications of the moment run deeper: in exposing the pneumatics of charm, Kitamura insists that there are motivations behind it. People have reasons for pushing one another around, and for endlessly repositioning themselves; they have longings and aversions—entire histories—that elude even the sharpest eye. It would be a privilege to watch Kitamura, with the full scope of her intelligence and art, illuminate these intimacies, too.

New Yorker Favorites

- Can reading make you happier ?

- Doomsday prep for the super-rich.

- The white darkness : a journey across Antarctica.

- Time-travelling with a dictionary .

- The assassin next door.

- The curse of the buried treasure .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

by Katie Kitamura ‧ RELEASE DATE: July 20, 2021

This psychological tone poem is a barbed and splendid meditation on peril.

A watchful, reticent woman sees peril and tries not to vanish.

“Every certainty can give way without notice,” thinks the narrator of Kitamura’s stunning novel, a statement both true and freighted. It's a delight to accompany the narrator’s astute observational intelligence through these pages, as it was in A Separation (2017), which also unspooled completely in the mind of its speaker. Both slim books are pared down, without chapter headings or quotation marks. A murder unsettles A Separation ; a mugging destabilizes this new book . Its narrator is a temporary translator at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, where an unidentified head of state is on trial for atrocities in the months before the Brexit vote. The accused specifically requests the narrator to translate for him in a claustrophobic meeting with his defense team: “ cross-border raid, mass grave, armed youth .” She hears and doesn’t hear the words amid her focus, just as she sees and doesn’t completely register events in her everyday life. “It is surprisingly easy to forget what you have witnessed,” she thinks, “the horrifying image or the voice speaking the unspeakable, in order to exist in the world we must and we do forget, we live in a state of I know but I do not know.” This is the crux of Kitamura’s preoccupation. She threads it brilliantly through the intimacies her character is trying to navigate: with new colleagues, women friends, and her beau, who goes away; with the work and with the nature of The Hague itself. Landscape holds a key, and on the final pages, the narrator intuits it might release her from some of the dread suffocating her. The novel packs a controlled but considerable wallop, all the more pleasurable for its nuance.

Pub Date: July 20, 2021

ISBN: 978-0-399-57616-4

Page Count: 240

Publisher: Riverhead

Review Posted Online: June 1, 2021

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 15, 2021

LITERARY FICTION | GENERAL FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Katie Kitamura

BOOK REVIEW

by Katie Kitamura

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

IT STARTS WITH US

by Colleen Hoover ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 18, 2022

Through palpable tension balanced with glimmers of hope, Hoover beautifully captures the heartbreak and joy of starting over.

The sequel to It Ends With Us (2016) shows the aftermath of domestic violence through the eyes of a single mother.

Lily Bloom is still running a flower shop; her abusive ex-husband, Ryle Kincaid, is still a surgeon. But now they’re co-parenting a daughter, Emerson, who's almost a year old. Lily won’t send Emerson to her father’s house overnight until she’s old enough to talk—“So she can tell me if something happens”—but she doesn’t want to fight for full custody lest it become an expensive legal drama or, worse, a physical fight. When Lily runs into Atlas Corrigan, a childhood friend who also came from an abusive family, she hopes their friendship can blossom into love. (For new readers, their history unfolds in heartfelt diary entries that Lily addresses to Finding Nemo star Ellen DeGeneres as she considers how Atlas was a calming presence during her turbulent childhood.) Atlas, who is single and running a restaurant, feels the same way. But even though she’s divorced, Lily isn’t exactly free. Behind Ryle’s veneer of civility are his jealousy and resentment. Lily has to plan her dates carefully to avoid a confrontation. Meanwhile, Atlas’ mother returns with shocking news. In between, Lily and Atlas steal away for romantic moments that are even sweeter for their authenticity as Lily struggles with child care, breastfeeding, and running a business while trying to find time for herself.

Pub Date: Oct. 18, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-668-00122-6

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Atria

Review Posted Online: July 26, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 2022

ROMANCE | CONTEMPORARY ROMANCE | GENERAL ROMANCE | GENERAL FICTION

More by Colleen Hoover

by Colleen Hoover

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

PERSPECTIVES

BOOK TO SCREEN

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

2024 newspaper of the year

@ Contact us

Your newsletters

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura, review: A glitteringly intelligent study of moral compromise

The american author's fourth novel is a coolly disquieting account of an interpreter who has moved from new york to work at the international court in the hague.

In one telling scene in Katie Kitamura’s fourth novel , its unnamed narrator introduces her boyfriend to her friend, and inwardly marvels at the “futility and falseness” of their chit-chat (everyone in the room is surely aware her friend has been fully briefed on this new love interest).

“Our behaviour did not seem especially strange, people behave with such conscious and unconscious dishonesty all the time,” thinks the narrator. Such an observation is typical of this graceful, glitteringly intelligent book, which examines the artifice embedded in all manner of social situations and systems.

Echoing the American writer’s previous novel, A Separation , which was about a translator who travels to Greece to track down her missing former husband, her protagonist here is an interpreter who has moved to The Hague from New York following the death of her father.

Brandon Taylor: ‘Which character do I most resemble? The irritating younger sister in a Jane Austen book’

She works for an unspecified international entity that strongly resembles the International Criminal Court . Rootless and grieving, she is searching for stability in a shifting world, but is soon assigned to the trial of a former president accused of war crimes (and who is partially based on Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia).

This is less a blow-by-blow account of the case than a study of the narrator’s moral queasiness about her work. She puzzles over the contradiction between the “high theatrics” of the court and the very real accounts of suffering relayed there. She also balks at how translating the president’s speech leads her to see things from his perspective: “I was repulsed to find myself so permeable.”

Elsewhere, the narrator frets about her increasingly complicated relationship with her boyfriend, who is married. She also befriends an enigmatic woman whose brother has been the victim of a crime.

Giving these storylines the same weight as the court case is a neat way of exploring the cognitive dissonance at play as we switch off from large-scale horrors to focus on everyday matters. “In order to exist in the world we must and we do forget, we live in a state of I know but I do not know,” observes the narrator, as her bus trundles past a detention centre and she considers how readily we overlook the less palatable parts of life.

Three Rooms by Jo Hamya, review: A brave, experimental debut

Kitamura’s prose is gorgeously crisp and precise, and teems with sharp observations about everything from language to coercive relationships. By conjuring a landscape rich with ambiguity and ambivalence, she gives the book the quality of a thriller, where few things are what they seem and where people and events are disquietingly unpredictable.

An engrossing and evocative page-turner, Intimacies is also a profound, affecting look at the moral compromises of modern life. It is an immensely perceptive read and one which, as the narrator gradually decides what she wants from her future, ends on a note of fragile hope.

Intimacies is published by Jonathan Cape, at £14.99

Most Read By Subscribers

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

The Book Report Network

Sign up for our newsletters!

Regular Features

Author spotlights, "bookreporter talks to" videos & podcasts, "bookaccino live: a lively talk about books", favorite monthly lists & picks, seasonal features, book festivals, sports features, bookshelves.

- Coming Soon

Newsletters

- Weekly Update

- On Sale This Week

Fall Reading

- Summer Reading

- Spring Preview

- Winter Reading

- Holiday Cheer

Word of Mouth

Submitting a book for review, write the editor, you are here:.

Like its critically acclaimed predecessor, A SEPARATION, Katie Kitamura’s new novel introduces a protagonist whose job it is to translate words from one language to another. In the case of INTIMACIES, however, the unnamed narrator works at a job where the stakes are much higher than literary translation --- the International Court at The Hague, where she acts as an interpreter in major criminal cases involving issues like genocide and terrorism. Combining a glimpse of the tensions inherent in this unusual occupation with an edgy love story, Kitamura once again has found the formula for a moody, tension-filled work that’s noteworthy for its ability to maintain a consistently elevated level of suspense from beginning to end.

The intensely self-aware and articulate narrator of INTIMACIES is a young woman who has moved to the Netherlands from New York in 2016 with a “renewed sense of possibility” after the death of her father following a long illness. She signs a one-year contract to work at The Hague, so there’s something of a provisional quality to her presence there, but that doesn’t prevent her from forming a close friendship with Jana, a curator at the Mauritshuis, an esteemed Dutch art museum. More significantly, she embarks on a romantic relationship with Adriaan, who she discovers is married and the father of two children whose mother has taken them to live in Portugal.

"There’s nothing explosive or startling in this brief novel, but the pleasures of inhabiting the mind of a complex and intriguing protagonist are considerable and undeniable."

Much of the novel’s tension revolves around whether Adriaan truly is resigned to the demise of his marriage or is instead committed to salvaging it. The narrator spends an agonizing interval in Adriaan’s apartment in what she thinks of as a “precarious position” after he departs for Lisbon, assuring her that he intends to ask his wife for a divorce. Her doubts about his intentions only grow as a projected one-week trip stretches on indefinitely. Convinced that she “had been complicit in my own erasure,” she frets that she had “made myself too easy to leave, stashed away like a spare part, I had asked for too little, and now it was too late.”

But it’s not only her personal life that’s tangled. Her professional responsibilities take on new difficulty and complexity when she’s asked to substitute for one of her colleagues as an interpreter in the long-running trial of the ex-president of an unnamed African nation who is accused of crimes against humanity for, among other things, mass murders allegedly committed at his direction as he attempted to cling to power following a disputed election.

Hers is an unusual job, one in which she regards herself at times as “only an instrument.” She admits that her role “can be profoundly disorienting, you can be so caught up in the minutiae of the act in trying to maintain utmost fidelity to the words being spoken first by the subject and then by yourself, that you do not necessarily apprehend the sense of the sentences themselves: you literally do not know what you are saying. Language loses its meaning.”

The narrator’s responsibilities in the case aren’t confined to the courtroom, as she’s called upon frequently to interpret at conferences for the defense team, led by a lawyer named Kees, who appears to take a more than professional interest in her. What becomes even more unsettling is the increasing attention the defendant begins paying her as her role in the case grows. When she must interpret the testimony of a family member of some of his victims, she’s brought face-to-face with the moral gravity of the proceeding in which she plays an anonymous, if vital, part.

Kitamura carefully evokes a sense of place in describing The Hague, a locale her protagonist describes as “almost strenuously civilized,” while simultaneously sensing that “the docile surface of the city concealed a more complex and contradictory nature.” An air of menace lingers over the story with the occurrence of a mugging outside the apartment building where Jana lives. That unease deepens when the narrator is introduced to the victim, the brother of a woman she meets at the opening of an exhibition that Jana curates.

Whether it’s in the quotidian details of life or her description of a fraught romantic relationship, what makes Kitamura’s work so satisfying is her ability to sustain what the novelist and teacher John Gardner described as the “vivid and continuous dream” that’s at the heart of the best fiction. She’s a seductive writer, enticing the reader effortlessly from one sentence to the next, impelled by an urgent desire to find out what will happen to her characters and to follow her more deeply into the darkest corners of their emotional lives. There’s nothing explosive or startling in this brief novel, but the pleasures of inhabiting the mind of a complex and intriguing protagonist are considerable and undeniable.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on July 29, 2021

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura

- Publication Date: July 19, 2022

- Genres: Fiction , Women's Fiction

- Paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Riverhead Books

- ISBN-10: 0399576177

- ISBN-13: 9780399576171

Support GMW's work in Wilton — Become a Member TODAY!

S upport Wilton's only locally-owned, independent source of news about Wilton.

For as little as $5/month, every GOOD Morning Wilton membership helps ensure we can continue to provide coverage of Wilton's town government, businesses, schools, community and more.

Wake up with GOOD Morning Wilton!

Sign up to receive GOOD Morning Wilton 's daily email newsletter every Monday-Friday. You'll be the FIRST to know the news that everyone in Wilton will be talking about!

Good Morning Wilton

BOOK REVIEW: “Intimacies” Offers Insightful Character Study

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Mastodon (Opens in new window)

We never learn our protagonist’s name. Even though she is the main character, she is the only one whose name Kitamura never reveals — she remains a passive observer to her own life. However, Kitamura allows us into her inner consciousness, her anxieties and insecurities. In every scene, uncertainty and apprehension linger. Though our narrator often isn’t privy to the whole story, she can sense that there are gaps in her knowledge. As an interpreter, her job is to “throw down planks across these gaps,” bridge the divide between languages. However, she cannot translate what goes on in the minds of her friends. She can only fill that gap with her own guesses or her imagination. When she describes her initial move to the Netherlands, she explains that “A place has a curious quality when you have only a partial understanding of its language, and in those early months the sensation was especially peculiar.” This statement applies to the unique, personal language each of her friends speaks, and the narrator struggles to gain a fuller understanding, dissatisfied with an incomplete picture.

See more related GMW stories...

54 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-3

Chapters 4-7

Chapters 8-11

Chapters 12-16

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Written in 2021 by Japanese American author Katie Kitamura, Intimacies explores the complicated nature of love and secrecy and examines the blurred boundaries that define human connections. The novel follows an unnamed narrator whose job as a language interpreter for the World Court in The Hague draws her into an intricate web of moral ambiguities within the diplomatic world. At the same time, she must navigate the psychological impact of grief and personal entanglements. The novel was longlisted for the 2021 National Book Award and PEN/Faulkner Award and was a finalist for the Joyce Carol Oates Award. The novel also made President Barack Obama’s summer reading list in 2021 and was listed as one of The New York Times’s Book Review ’s “10 Best Books of 2021.”

Kitamura’s previous novel, A Separation, also featuring an unnamed narrator, was a finalist for the Premio Gregor von Rezzori and a New York Times Notable Book in 2017. Translated into 16 different languages, A Separation was widely acknowledged as one of the year's best books and was adapted into a screenplay. Additionally, two of her other works, Gone to the Forest and The Longshot , were awarded the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award. Kitamura currently teaches creative writing at New York University.

This guide refers to the 2021 Penguin Random House eBook edition.

Content Warning: Both the source material and this guide contain descriptions of crimes against humanity, including a victim’s testimony detailing a genocide in her village.

Plot Summary

After her father dies and her mother returns to their country of origin in Singapore, the unnamed narrator accepts a position as an interpreter for the World Court in The Hague, Netherlands. Since her contract is only for a year, everything about her life in The Hague feels temporary, including her relationships and her impersonal rented apartment. The narrator has a convivial relationship with her coworkers at the Court, but she has only one close friend in The Hague: Jana , a curator at the Mauritshuis Museum. The narrator is also involved in a romantic relationship with a married man named Adriaan . She does not know about his wife and children until Adriaan’s friend Kees, a renowned defense attorney, tells her at a cocktail party. While Adriaan steps away, Kees drunkenly and luridly makes a pass at the narrator and tells her that Gaby, Adriaan’s wife, has left him and has taken the children to Lisbon, Portugal.

The narrator’s work in the Court goes far beyond translating testimony from one language to another, for she must also accurately interpret the words’ deeper meanings in order to create a cohesive narrative and preserve the truth as much as possible. The work is physically demanding, requiring her to sit in the courtroom for long hours as she listens, makes notes, and rapidly interprets the proceedings. She also learns that the work of translating is emotionally draining because the Court tries war criminals, and she must listen to gruesome details of many heinous crimes against humanity.

Jana invites the narrator over to her apartment for dinner and encourages her to move to the same neighborhood and purchase her own apartment. The narrator is uncertain how long she will remain in The Hague and is reluctant to put down any permanent roots. They plan for another dinner party that will including Adriaan, and the narrator returns home. The following day, Jana calls to check on her. A man was mugged and beaten outside of Jana’s apartment that night. The random act of violence has frightened Jana and also unnerves the narrator: She wonders what else is lurking under the delicately curated façade of the city. Jana later learns that the victim was Anton de Rijik , a local bookshop owner.

Bettina, the narrator’s supervisor, assigns her to translate for a Jihadist who is arriving at the Detention Center. His trial will be high-profile and secretive, so she cannot tell anyone about his arrival. The narrator goes to the Detention Center in the middle of the night to translate the Jihadist’s rights before officials put him behind bars to await trial. The court assumes that his first language is French, but he is offended by the narrator’s French and is incensed that an Arabic translator has not been procured. The entire encounter is unsettling to the narrator, for as she reviews his file and sees his crimes, she feels that she has never been in such close proximity to pure evil. The interaction leaves her exhausted, and she is late for her dinner with Jana and Adriaan the next day. When she arrives an hour late for dinner, she perceives that Jana might be flirting with Adriaan, but she is not quite sure. In reality, the two spent the hour getting to know one another, and Jana also grilled Adriaan to ascertain his fitness as a partner for her friend. After dinner, on the way to his apartment, Ariaan tells the narrator that he will be traveling to Lisbon to see his children and to ask Gaby for a divorce. He will be gone for a week or perhaps longer, and he invites her to stay in his apartment while he’s away. Later that night, the narrator leaves Adriaan’s bed and walks around his apartment. She notices that he still has a photo of Gaby and reflects on the fact that he has another life about which she knows very little.

Amina, the narrator’s co-worker and one of the most adept translators in the Court, is pregnant and will soon be taking leave. The narrator will take her place, so she joins Amina in the translator's booth for the trial of the former president of a West African country, who has been accused of crimes against humanity. The trial is widely publicized because the Court has recently been under fire for showing bias against African countries. In addition to protesters outside the court, many supporters of the former president are in the court gallery. As the narrator takes over the translating duties, she finds herself increasingly uncomfortable with how close her duties bring her to this man who has no remorse for his crimes and behaves like a celebrity in court. She is disturbed by the unwanted intimacy that speaking his words creates for her. Even more alarming is Kees’s surprise appearance in the courtroom as a lead attorney for the defense. Still unnerved by her prior interaction with Kees, the narrator worries that their social connection will be interpreted as a conflict of interest and will get her fired.

Weeks go by, and Adriaan doesn’t return the narrator’s messages. She feels foolish staying in his lavish apartment and becomes increasingly lonely as she begins to doubt the viability of their relationship. Meanwhile, as the trial progresses, the defense team summons the narrator to translate for the president in their private meetings. To do her job properly, she must force herself to put aside her judgments of the president’s crimes so that she can focus on the task of translating, but she remains uncomfortable with the growing rapport that the president develops with her. To make matters worse, Kees catches her after one of the meetings and suggests that Adriaan has gone to Lisbon to win Gaby back from her lover.

One day, Jana invites the narrator to an art opening at the Mauritshuis with Eline, who is the sister of Anton, the bookshop owner who was recently mugged. The narrator and Eline bond over a mutual interest in a particular painting at the permanent exhibit. Eline later invites the narrator out for coffee, but the narrator still does not reveal her awareness that Eline is Anton’s sister. Eline invites the narrator to have dinner with herself and Anton. The dinner is awkward as Anton shares the details of his recent experience of being mugged. He claims to have no memory of the attack or even of why he was in that neighborhood in the first place. His claim of amnesia is questionable, and later, the narrator spots Anton having lunch with another woman. She realizes that he is having an affair and has lied about the details of that night in order to hide his clandestine relationship.

The trial continues, and the prosecution calls a victim of the genocide to testify against the accused. Her compelling testimony captivates the interpreters and makes the narrator realize the degree to which she has become desensitized to the testimony that she must interpret. In the final private meeting for which the narrator is asked to translate, the president realizes that she has surrendered her neutrality, and he asks her to leave. The Court drops the case against the president and sets him free. The narrator’s supervisor, Bettina, offers the narrator a permanent job at the Court, but she declines, claiming that she is not emotionally equipped to handle the intensity of the work. The narrator moves out of Adriaan’s apartment, but when she returns to collect her things, Gaby appears unexpectedly and says that Adriaan is returning with the children. Feeling lost and alone, the narrator visits the dunes near the beach and calls her mother. Her mother reminds her of when they visited The Hague during the narrator’s childhood and reassures her that when some things end, new things begin. Adriaan returns, and the narrator accepts his invitation to dinner. He apologizes for ignoring her messages and explains that dealing with his wife and children has proven more difficult than anticipated. The narrator empathizes with his situation and resolves to give him and their relationship another chance. Adriaan asks to walk with her to the dunes, and she accepts.

Featured Collections

View Collection

Asian American & Pacific Islander...

Books on Justice & Injustice

Good & Evil

National Book Awards Winners & Finalists

Popular Study Guides

Psychological Fiction

The Best of "Best Book" Lists

The Book Report Network

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

Sign up for our newsletters!

Find a Guide

For book groups, what's your book group reading this month, favorite monthly lists & picks, most requested guides of 2023, when no discussion guide available, starting a reading group, running a book group, choosing what to read, tips for book clubs, books about reading groups, coming soon, new in paperback, write to us, frequently asked questions.

- Request a Guide

Advertise with Us

Add your guide, you are here:, reading group guide.

- Discussion Questions

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura

- Publication Date: July 19, 2022

- Genres: Fiction , Women's Fiction

- Paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Riverhead Books

- ISBN-10: 0399576177

- ISBN-13: 9780399576171

- About the Book

- Reading Guide (PDF)

- How to Add a Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Newsletters

Copyright © 2024 The Book Report, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The Pilot Who Almost Crashed a Plane While on Mushrooms

“Lie to Fly” tells the tragic story of a pilot who nearly killed 83 passengers—and ruined his career—while tripping on mushrooms.

Nick Schager

Entertainment Critic

On October 22, 2023, Joe Emerson boarded a flight from Everett, Washington to San Francisco, California. As an off-duty Alaska Airlines pilot, he was able to ride in the cockpit's jump seat. Once in the air, he became agitated and uncomfortable, and without much warning—save for a few strange glances—he suddenly leapt up and attempted to grab the engine fire shut-off handles, which if pulled would have sent the craft into free fall.

In audio of this incident, Emerson states, “I’m not OK” and, after being asked if feels alright, begins cursing as he springs into dangerous action. Fortunately, the pilots’ quick reactions stopped Emerson from accomplishing his goal, and in the aftermath of this near catastrophe, he was charged with, among other federal crimes, 83 counts of attempted murder.

Scarier still? Emerson’s explanation for his outburst was that, two days prior, he’d taken psychedelic mushrooms, and on this flight home, he couldn’t tell what was real and what was a dream.

Lie to Fly (August 23), the latest installment of FX’s The New York Times Presents -branded docuseries, is an investigation into Emerson’s saga—and amazingly, his use of mind-altering substances is the least stunning thing about it. To be sure, the fact that an experienced pilot went haywire thanks to ingesting psilocybin was attention-grabbing at the time, and is the primary selling point of this hour-long venture. Yet as elucidated by producer/director Carmen Garcia Durazo, Emerson’s story is also the most shocking evidence to date of a burgeoning United States aviation industry problem that threatens the safety of pilots and passengers alike, and seems to require large-scale reforms lest it blossom into a full-blown crisis.

Emerson knew from an early age that he wanted to fly. As a lonely kid, being in the air gave him the sense of “freedom” and purpose he’d always craved. In a new interview that forms the basis of Lie to Fly , Emerson talks candidly about his fondness for his profession, as well as its difficulties, given that traveling for a living means constant time away from home and, in his case, his wife Sarah Stretch and their two sons in Pleasant Hill, California. To maintain bonds with loved ones (and to make up for the fact that he often missed big events and had to cancel plans at the last second), Emerson would send his clan regular videos from his many pit-stops, some of which are depicted here. Despite these difficulties, however, Emerson was certain that being in the cockpit was “where I needed to be.”

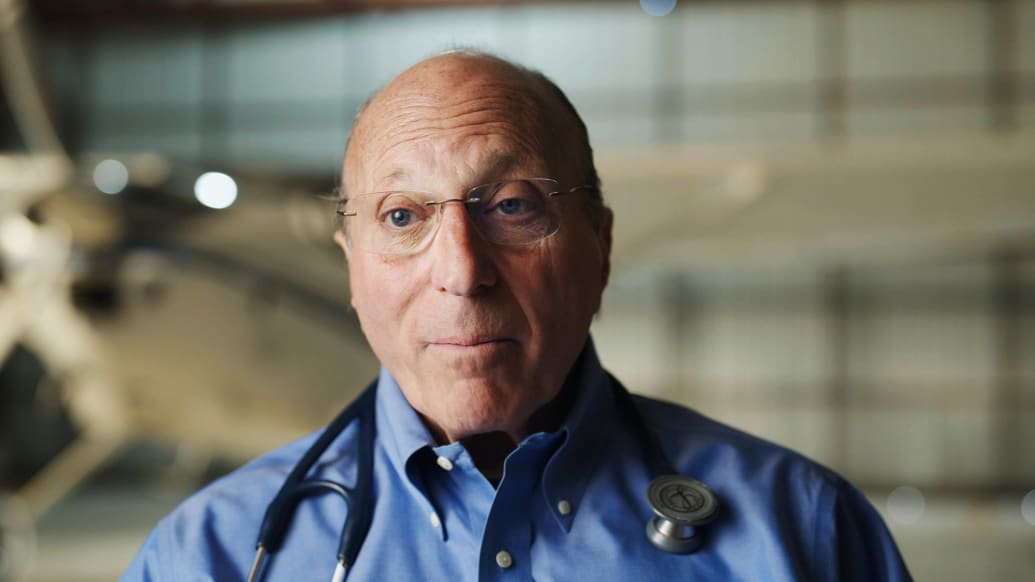

Dr. Brent Blue, MD.

If being a pilot put an inevitable strain on Emerson’s life, so too did the terrible news that his fellow pilot and close friend Scott Pinney (who’d been the best man at his wedding) had died of an out-of-the-blue cardiac event. This rocked Emerson, who in the ensuing weeks and months became very close with Pinney’s father Frank, who says that their relationship “literally changed my life.” They grieved over gin and tonics (a course of action that Emerson admits wasn’t shrewd), and in October 2023, Emerson and some of Pinney’s other friends took a vacation together on remote property owned by Frank. This spot included a yurt, and while the guys were all together, Emerson was cajoled into trying mushrooms, thus initiating mayhem two days later.

Lie to Fly has Emerson recount his under-the-influence ordeal, during which he became convinced that he was “trapped” and that nothing around him was real. This is harrowing in and of itself, and yet Durazo’s exposé is really about the larger issue at play here: Emerson’s prior hesitancy to seek out counseling and medical attention for his depression. The reason for that reluctance, it turns out, is a system that’s increasingly ill-equipped to grapple with modern realities. For pilots to receive medical certification, they must pass exams conducted by senior aviation medical examiners such as Dr. Brent Blue, whose reports are then sent to the Federal Aviation Admission (FAA) so a determination can be made about whether an individual is fit to fly. Any red flags can lead to deferrals, and because of staff shortages and bureaucratic obstacles, those can last for more than a year—a calamitous situation for pilots who love their jobs and for families that want to stay financially afloat.

Pilot medical certification.

Because medical deferrals can go on for extended stretches (there are no Congress-ratified rules governing timetables), and because common challenges such as depression and anxiety (and the SSRIs that counteract them) are viewed the same as serious conditions such as schizophrenia, many pilots simply don’t seek the care they need. What this means is that rather than being flown by men and women who are depressed and medicated, millions are potentially being flown by pilots who aren’t properly coping with their struggles.

Lie to Fly portrays Emerson as merely an extreme example of the consequences of this “culture of concealment,” and his tale is paired with that of John Hauser, a nineteen-year-old sophomore at the University of North Dakota—where he was studying to be a commercial pilot—who chose to take his life because he knew that, should he get help for his mental health issues, he’d jeopardize his chance to professionally fly.

Lie to Fly is bolstered by input from John’s parents, aviation lawyer Joseph LoRusso, University of North Dakota Assistant Professor of Aviation Dr. William Hoffman, and FAA U.S. Federal Air Surgeon Dr. Susan Northrup, all of whom speak to the intricacies of this important topic. Most heartrending of all, however, is Emerson, who discusses his plight with an anguish that’s colored by self-recrimination, fear, and frustration at a paradigm that makes pilots choose between their dreams and their health.

Such a dilemma can only, in the end, lead to bad choices. While Durazo’s documentary ends on a somewhat heartening note—with the FAA taking “baby steps” toward rectifying this state of affairs—it nonetheless paints an unnerving portrait of aviation industry shortcomings that put everyone at risk. It also, in the process, serves as a stark reminder that sometimes, there’s more to a story than just its sensationalistic headline.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here .

READ THIS LIST

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

An Experiment in Lust, Regret and Kissing

By Curtis Sittenfeld

Ms. Sittenfeld is the best-selling author of seven novels and the forthcoming story collection “Show Don’t Tell.”

This summer, I agreed to a literary experiment with Times Opinion: What is the difference between a story written by a human and a story written by artificial intelligence?

We decided to hold a contest between ChatGPT and me, to see who could write — or “write” — a better beach read. I thought going head-to-head with the machine would give us real answers about what A.I. is and isn’t currently capable of and, of course, how big a threat it is to human writers. And if you’ve wondered, as I have, what exactly makes something a beach read — frothy themes or sand under your feet? — we set out to get to the bottom of that, too.

First, we asked readers to vote on which themes they wanted in their ideal beach read. We also included some options that are staples of my fiction, including privilege, self-consciousness and ambivalence. ChatGPT and I would then work using the top vote-getters.

Lust, regret and kissing won, in that order. Readers also wrote in suggestions. They wanted beach reads about naps and redemption and tattoos gone wrong; puppies and sharks and secrets and white linen caftans; margaritas and roller coasters and mosquitoes; yearning and bonfires and women serious about their vocations. At least 10 readers suggested variations on making the characters middle-aged. One reader wrote, “We tend to equate summer with kids,” and suggested I explore “Why does summer still feel special for older people?”

So I added middle-age and another write-in, flip-flops — because it seemed fun, easy and, yes, summery — to the list and got to work on a 1,000-word story.

My editor fed ChatGPT the same prompts I was writing from and asked it to write a story of the same length “in the style of Curtis Sittenfeld.” ( I’m one of the many fiction writers whose novels were used, without my permission and without my being compensated, to train ChatGPT. Groups of fiction writers, including people I’m friends with, have sued OpenAI, which developed ChatGPT, for copyright infringement. The New York Times has sued Microsoft and OpenAI over the use of copyrighted work.)

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Riverhead Books. The unnamed heroine of Intimacies, Katie Kitamura's fascinating and mysterious new novel, observes that "none of us are able to see the world we are living in — the world ...

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura. reviewed by Greg Chase. With Intimacies, her fourth novel, Katie Kitamura cements her status as one of contemporary fiction's most controlled and perceptive writers, particularly when it comes to ambiguities of language and the risks of miscommunication.The novel's unnamed first-person narrator has just moved to The Hague, where she works as an interpreter for ...

Katy Waldman reviews Katie Kitamura's new novel, "Intimacies," which suggests that we are constantly buffeted by the forces of beauty, seduction, and charm.

INTIMACIES. This psychological tone poem is a barbed and splendid meditation on peril. A watchful, reticent woman sees peril and tries not to vanish. "Every certainty can give way without notice," thinks the narrator of Kitamura's stunning novel, a statement both true and freighted. It's a delight to accompany the narrator's astute ...

Review by Ron Charles. July 13, 2021 at 1:17 p.m. EDT. At the opening of Katie Kitamura's intense, unsettling new novel, " Intimacies ," an unnamed narrator has left New York in a fugue of ...

A NEW YORK TIMES TOP 10 BOOK OF 2021LONGLISTED FOR THE 2021 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD IN FICTIONONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S FAVORITE 2021 READSAN INSTANT NATIONAL BESTSELLER A BEST BOOK OF 2021 FROM Washington Post, Vogue, Time, Oprah Daily, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Atlantic, Kirkus and Entertainment Weekly"Intimacies is a haunting, precise, and morally astute novel ...

Intimacies featured on a list of book recommendations by Barack Obama for the summer of 2021. [3] Dwight Garner described the book as "a taut, moody novel that moves purposefully between worlds" in his review for The New York Times. [4] Ron Charles reviewed the book for the Washington Post. [5] Brandon Yu compared the work favourably to Kitamura's third novel A Separation. [6]

The American author's fourth novel is a coolly disquieting account of an interpreter who has moved from New York to work at the International Court in The Hague. Katie Kitamura's crisp, elegant ...

A NEW YORK TIMES TOP 10 BOOK OF 2021 LONGLISTED FOR THE 2021 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD IN FICTION ONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S FAVORITE 2021 READS AN INSTANT NATIONAL BESTSELLER A BEST BOOK OF 2021 FROM Washington Post, Vogue, Time, Oprah Daily, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Atlantic, Kirkus and Entertainment Weekly "Intimacies is a haunting, precise, and morally astute ...

Intimacies is a quietly understated novel about big issues (another paradox!), including morality, crimes against humanity, ... and I've been wondering ever since what I might say about it. I'm sorry, I'm stuck at excellent review, sounds like an interesting book. Like Like. Reply. kimbofo says: March 4, 2024 at 6:02 PM.

Listen. (4 min) The unnamed narrator of Katie Kitamura's novel "Intimacies" (Riverhead, 225 pages, $26) has moved from New York to the Hague to take a temporary position as an interpreter at ...

An interpreter has come to The Hague to escape New York and work at the International Court. A woman of many languages and identities, she is looking for a place to finally call home. She's drawn into simmering personal dramas: her lover, Adriaan, is separated from his wife but still entangled in his marriage. Her friend, Jana, witnesses a seemingly random act of violence, a crime the ...

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Katie Kitamura's Intimacies (Riverhead, 2021) follows a young woman working at the International Criminal Court in The Hague as a translator, leaving New York after her father's death.As she is given the responsibility of interpreting the trial of a powerfully charismatic West African dictator, brought to court for perpetrating an ethnic cleansing, she struggles to retain stability and ...

A NEW YORK TIMES TOP 10 BOOK OF 2021 LONGLISTED FOR THE 2021 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD IN FICTION ONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S FAVORITE 2021 READS AN INSTANT NATIONAL BESTSELLER A BEST BOOK OF 2021 FROM Washington Post, Vogue, Time, Oprah Daily, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Atlantic, Kirkus and Entertainment Weekly "Intimacies is a haunting, precise, and morally astute ...

The novel was longlisted for the 2021 National Book Award and PEN/Faulkner Award and was a finalist for the Joyce Carol Oates Award. The novel also made President Barack Obama's summer reading list in 2021 and was listed as one of The New York Times's Book Review 's "10 Best Books of 2021."

Intimacies. by Katie Kitamura. Publication Date: July 19, 2022. Genres: Fiction, Women's Fiction. Paperback: 240 pages. Publisher: Riverhead Books. ISBN-10: 0399576177. ISBN-13: 9780399576171. From Katie Kitamura, the author of A SEPARATION, comes an electrifying story about a woman caught between many truths.

Author: Katie Kitamura Genre: Fiction, Drama, Relationships Publisher: Penguin Random House Rating: 2/5 About the Author: Katie Kitamura (born 1979) is an American novelist, journalist, and art…

A NEW YORK TIMES TOP 10 BOOK OF 2021 LONGLISTED FOR THE 2021 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD IN FICTION ONE OF BARACK OBAMA'S FAVORITE 2021 READS AN INSTANT NATIONAL BESTSELLER A BEST BOOK OF 2021 FROM Washington Post, Vogue, Time, Oprah Daily, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Atlantic, Kirkus and Entertainment Weekly "Intimacies is a haunting, precise, and morally astute novel ...

Intimacies. by Katie Kitamura. Publication Date: July 19, 2022. Genres: Fiction, Women's Fiction. Paperback: 240 pages. Publisher: Riverhead Books. ISBN-10: 0399576177. ISBN-13: 9780399576171. A site dedicated to book lovers providing a forum to discover and share commentary about the books and authors they enjoy.

On October 22, 2023, Joe Emerson boarded a flight from Everett, Washington to San Francisco, California. As an off-duty Alaska Airlines pilot, he was able to ride in the cockpit's jump seat.

A person trying to escape an abusive relationship, on average, needs seven attempts to actually leave. Lily Bloom, the protagonist of the new drama "It Ends With Us," needs only one. In the ...

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

The New York Times has sued Microsoft and OpenAI over the use of copyrighted work.) Readers made it clear, with their votes and suggestions, that a beach read is more than just a story you happen ...