50 Best Sample Research Proposal on Education Topics

A research proposal is a comprehensive plan that outlines the key components of a research study you intend to conduct. It serves as a roadmap for your investigation, helping you to clearly articulate your research goals, methodology, and potential contributions to the field of education. Here are Sample Research Proposal on Education Topics with examples to help you prepare for your research proposal.

By developing a well-structured proposal, you demonstrate your understanding of the research process and your ability to design a rigorous and meaningful study.

What You'll Learn

Sample Research Proposal on Education Topics

1. research topic.

The foundation of your research proposal is the selection of an interesting and relevant topic within the field of education. This topic should align with your personal interests, academic background, and potential for making a valuable contribution to existing knowledge.

Examples of Education Research Topics:

- Impact of technology integration on student learning outcomes in science classrooms

- Effectiveness of inquiry-based learning approaches for developing critical thinking skills

- Strategies for improving reading comprehension and literacy among English language learners

- Role of parental involvement in promoting academic achievement and motivation

- Factors influencing teacher job satisfaction, burnout, and retention rates

- Effects of inclusive education practices on students with special needs

- Exploring culturally responsive teaching methods in diverse classrooms

2. Background and Rationale

In this section, you will provide a comprehensive context for your research study, highlighting the importance of your chosen topic and the specific problems or issues it addresses. You should establish a clear rationale for your research by identifying gaps or limitations in existing literature and explaining how your study can contribute to filling those gaps and advancing knowledge in the field.

“While numerous studies have examined the impact of technology integration in classrooms, there is a lack of research specifically focused on the effects of interactive whiteboards on student learning outcomes in science subjects at the secondary level. This study aims to investigate the potential benefits and challenges of using interactive whiteboards in high school science classrooms, and how this technology may influence student achievement, engagement, and interest in science compared to traditional teaching methods.”

3. Research Questions or Hypotheses

Based on your background research and identified knowledge gaps, you will formulate specific research questions or hypotheses that will guide your investigation. These should be clear, measurable, and directly aligned with your research objectives.

Example Research Questions:

- How does the use of interactive whiteboards in high school science classrooms influence student achievement in science compared to traditional teaching methods?

- What are the perceptions and attitudes of students and teachers towards the use of interactive whiteboards in science instruction?

- How does the integration of interactive whiteboards impact student engagement and interest in science subjects?

Example Hypothesis:

“Students in high school science classrooms that incorporate interactive whiteboards will demonstrate significantly higher achievement scores and improved engagement compared to those in classrooms using traditional teaching methods.”

4. Literature Review

In this section, you will provide a comprehensive overview of existing research and literature related to your topic. This review should critically analyze and synthesize relevant studies, theories, and findings from scholarly sources. Identify gaps, contradictions, or areas that need further exploration, and explain how your research study will contribute to addressing these gaps and advancing knowledge in the field.

5. Research Methodology

This section outlines the specific methods and procedures you will employ to conduct your research study effectively. It should provide a detailed description of the following components:

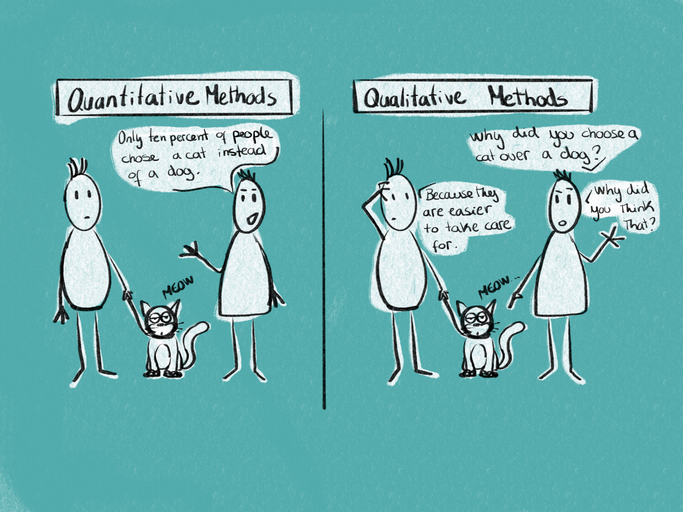

a. Research Design

- Qualitative (e.g., case studies, ethnographies, phenomenological studies)

- Quantitative (e.g., experiments, surveys, correlational studies)

- Mixed methods (combining qualitative and quantitative approaches)

Justify your choice of research design and explain how it aligns with your research questions and objectives.

b. Participants or Sample

- Describe the target population for your study (e.g., high school science students, teachers)

- Explain your sampling techniques (e.g., random, stratified, convenience sampling)

- Provide details on sample size and any inclusion/exclusion criteria

c. Data Collection Methods

- Surveys (e.g., online, paper-based, Likert scales)

- Interviews (e.g., structured, semi-structured, focus groups)

- Observations (e.g., classroom observations, video recordings)

- Document analysis (e.g., student work samples, lesson plans)

- Experimental tasks or assessments

Describe the specific data collection instruments or tools you will use and how they align with your research questions or hypotheses.

d. Data Analysis Plan

- For quantitative data: statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis)

- For qualitative data: coding and thematic analysis techniques

- For mixed methods: explain how you will integrate and triangulate different data sources

Provide a clear plan for how you will analyze the data collected, ensuring that your analysis methods are appropriate for your research design and questions.

Read more on Research Methodology

6. Expected Outcomes and Significance

In this section, you should articulate the potential implications and contributions of your research study to the field of education. Describe how your findings could inform educational practices, policies, or curriculum development. Additionally, discuss how your research could pave the way for future investigations or address broader educational issues or challenges.

“The findings of this study could provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of interactive whiteboards as a teaching tool in science classrooms, potentially informing decisions about technology integration and resource allocation in schools. Additionally, understanding the impact of interactive whiteboards on student engagement and interest in science subjects could have implications for addressing the declining interest in STEM fields among high school students.”

7. Timeline

Provide a detailed and realistic timeline for completing the various stages of your research project. This should include estimated dates or durations for tasks such as literature review, obtaining necessary approvals or permissions, participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis, and writing the final report or thesis.

8. Ethical Considerations

Depending on the nature of your research study, you may need to address ethical considerations related to working with human participants, data privacy, and potential risks or benefits. Outline the steps you will take to ensure ethical conduct, obtain necessary approvals or consent, and protect the rights and well-being of participants.

9. Limitations and Delimitations

It is important to acknowledge the potential limitations and delimitations of your research study. Limitations refer to factors or constraints beyond your control that may affect the generalizability or validity of your findings. Delimitations are the conscious boundaries or choices you make to narrow the scope of your research. By addressing these aspects, you demonstrate an understanding of the study’s constraints and the appropriate context for interpreting the results.

10. References

Include a comprehensive list of relevant literature and sources you have consulted or plan to use in your research study. Follow the appropriate citation style (e.g., APA, MLA) and ensure that all in-text citations are reflected in the reference list.

50 Sample Research proposal topics in education

- Effectiveness of project-based learning in promoting critical thinking skills.

- Impact of classroom technology integration on student engagement and motivation.

- Strategies for fostering inclusive and equitable learning environments.

- Role of social-emotional learning in academic achievement and well-being.

- Effects of gamification on student learning outcomes and retention.

- Exploring culturally responsive teaching practices in diverse classrooms.

- Factors influencing teacher job satisfaction, burnout, and retention rates.

- Strategies for improving literacy and reading comprehension among struggling readers.

- Impact of parental involvement on student academic achievement and motivation.

- Effectiveness of differentiated instruction in meeting diverse learning needs.

- Role of peer mentoring in facilitating student success and adjustment.

- Exploring the benefits and challenges of implementing a flipped classroom model.

- Strategies for promoting positive school climate and reducing bullying.

- Impact of outdoor education and nature-based learning on student well-being.

- Examining the effectiveness of different assessment methods in measuring learning.

- Strategies for supporting English language learners in mainstream classrooms.

- Impact of early childhood education programs on later academic success.

- Exploring the use of virtual reality and augmented reality in educational settings.

- Factors influencing student motivation and engagement in STEM subjects.

- Strategies for promoting inclusive education for students with special needs.

- Examining the role of arts education in fostering creativity and self-expression.

- Impact of mindfulness and meditation practices on student well-being and academic performance.

- Strategies for promoting digital literacy and responsible technology use.

- Exploring the benefits and challenges of personalized learning approaches.

- Impact of service-learning and community engagement on student development.

- Examining the effectiveness of different instructional models for teaching mathematics.

- Strategies for promoting positive school-family partnerships and communication.

- Impact of physical education and physical activity on student health and academic performance.

- Exploring the use of open educational resources (OERs) in higher education.

- Factors influencing student academic resilience and persistence.

- Strategies for promoting social and emotional learning in early childhood settings.

- Impact of professional development programs on teacher effectiveness and student outcomes.

- Exploring the use of educational technology in distance learning and online education.

- Strategies for promoting self-regulated learning and metacognitive skills.

- Impact of inquiry-based learning approaches on student understanding and problem-solving skills.

- Examining the role of extracurricular activities in student development and well-being.

- Strategies for promoting positive classroom management and student behavior.

- Impact of collaborative learning and group work on student achievement.

- Exploring the use of mobile technologies and apps in educational settings.

- Strategies for supporting students with learning disabilities and ADHD.

- Impact of project-based learning on student engagement and real-world skill development.

- Examining the effectiveness of different teaching methods for adult learners.

- Strategies for promoting global citizenship and intercultural competence in education.

- Impact of school counseling services on student well-being and academic success.

- Exploring the use of adaptive learning technologies and personalized instruction.

- Strategies for promoting environmental education and sustainability in schools.

- Impact of peer tutoring programs on student academic achievement and social skills.

- Examining the role of teacher mentorship programs in supporting new teachers.

- Strategies for promoting digital citizenship and online safety education.

- Impact of maker spaces and hands-on learning experiences on student engagement and creativity.

FAQs on Sample Research Proposal on Education Topics

What is the best topic for research in education.

The “best” topic depends on your interests and current issues in education. Some compelling areas include:

- Impact of technology on learning outcomes

- Strategies for inclusive education

- Effectiveness of project-based learning

- Mental health support in schools

- Addressing the achievement gap

How do you write a research proposal for education?

Key steps include:

- Choose a relevant topic

- Conduct initial literature review

- Develop your research question

- Outline your methodology

- Explain significance of the study

- Draft a timeline and budget

- List references

I can provide more details on any of these steps if needed.

What are 10 examples of research titles in school?

- Effects of Mindfulness Training on Student Stress Levels

- Gamification in Math Education: Impact on Engagement and Performance

- Peer Tutoring Programs: Benefits for Tutors and Tutees

- Parent Involvement and Its Influence on Academic Achievement

- Effectiveness of Flipped Classroom Model in Science Education

- Cultural Responsiveness in Curriculum Design

- Social Media Use and Its Effects on Student Writing Skills

- Early Childhood Nutrition Programs and Cognitive Development

- Impact of School Start Times on Adolescent Sleep and Academic Performance

- Teacher Burnout: Causes, Consequences, and Interventions

What is the best topic for a research proposal?

The best topic is one that:

- Addresses a gap in current research

- Is relevant to current educational challenges

- Aligns with your interests and expertise

- Has potential for practical application

- Is feasible given your resources and timeframe

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Post navigation

Previous post.

📕 Studying HQ

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Research Proposal – Types, Template and Example

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step...

17 Research Proposal Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

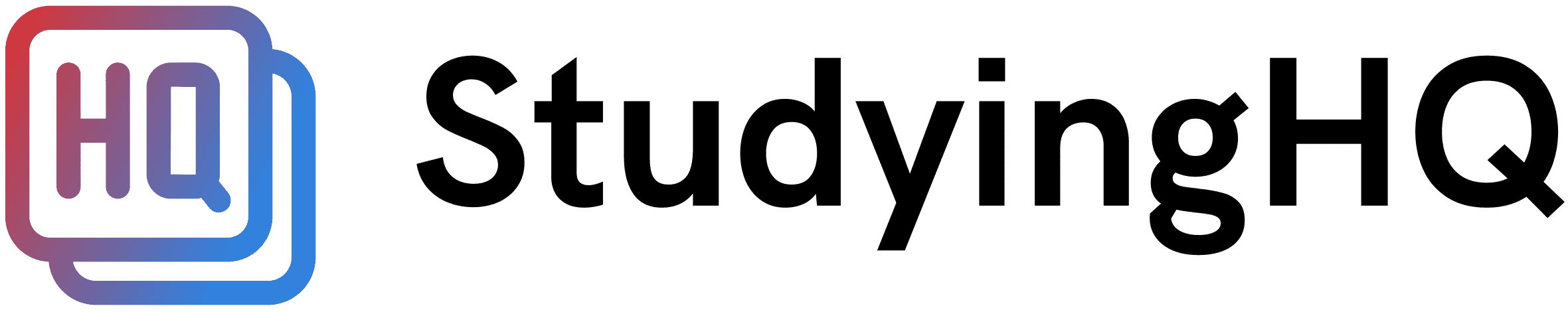

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

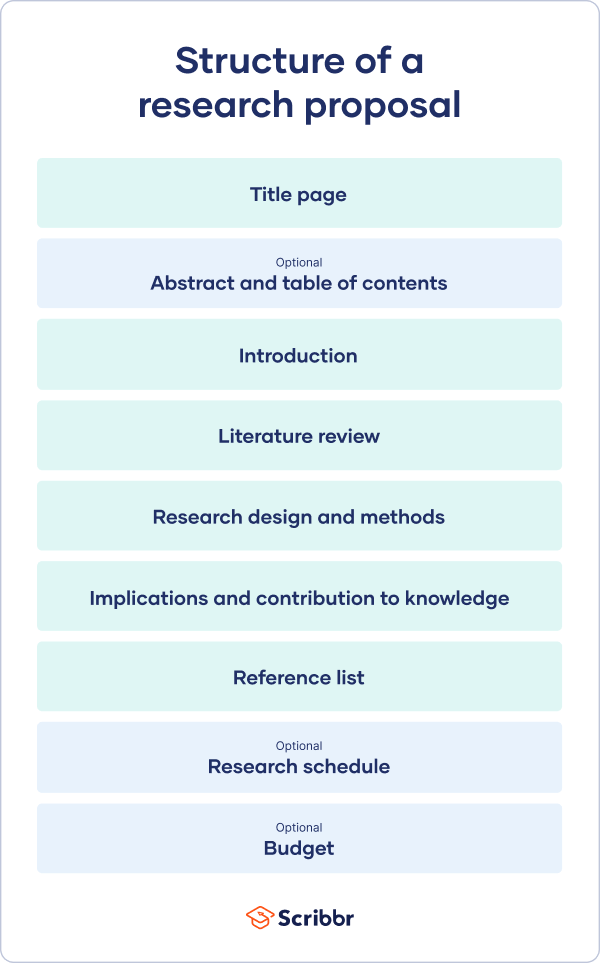

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians

Abstract: This research will examines the impact of effective nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and health outcomes for women following c-sections, utilizing a mixed-methods approach with patient surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Introduction: It has long been known that effective communication between nurses and patients is crucial for quality care. However, additional complications arise following emergency c-sections due to the interaction between new mother’s changing roles and recovery from surgery.

Literature Review: A review of the literature demonstrates the importance of nurse-patient communication, its impact on patient satisfaction, and potential links to health outcomes. However, communication between nurses and new mothers is less examined, and the specific experiences of those who have given birth via emergency c-section are to date unexamined.

Research Design and Methods: Participants will be patients in a hospital setting who have recently had an emergency c-section. A self-report survey will assess their satisfaction with nurse-patient communication and perceived health outcomes. A subset of participants will be selected for in-depth interviews to explore their experiences and perceptions of the communication with their nurses.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including rolling recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing within the hospital.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the significance of nurse-patient communication in supporting new mothers who have had an emergency c-section. Recommendations will be presented for supporting nurses and midwives in improving outcomes for new mothers who had complications during birth.

5. Social Work Research Proposals

- Experiences of negotiating employment and caring responsibilities of fathers post-divorce

- Exploring kinship care in the north region of British Columbia

Consider this hypothetical social work research proposal:

The Role of a Family-Centered Intervention in Preventing Homelessness Among At-Risk Youthin a working-class town in Northern England

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effectiveness of a family-centered intervention provided by a local council area in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth. This case study will use a mixed-methods approach with program evaluation data and semi-structured interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data .

Introduction: Homelessness among youth remains a significant social issue. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in addressing this problem and identify factors that contribute to successful prevention strategies.

Literature Review: A review of the literature has demonstrated several key factors contributing to youth homelessness including lack of parental support, lack of social support, and low levels of family involvement. It also demonstrates the important role of family-centered interventions in addressing this issue. Drawing on current evidence, this study explores the effectiveness of one such intervention in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth in a working-class town in Northern England.

Research Design and Methods: The study will evaluate a new family-centered intervention program targeting at-risk youth and their families. Quantitative data on program outcomes, including housing stability and family functioning, will be collected through program records and evaluation reports. Semi-structured interviews with program staff, participants, and relevant stakeholders will provide qualitative insights into the factors contributing to program success or failure.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Budget: Expenses include access to program evaluation data, interview materials, data analysis software, and any related travel costs for in-person interviews.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in preventing youth homelessness, potentially informing the expansion of or necessary changes to social work practices in Northern England.

Research Proposal Template

Get your Detailed Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

This is a template for a 2500-word research proposal. You may find it difficult to squeeze everything into this wordcount, but it’s a common wordcount for Honors and MA-level dissertations.

| Section | Checklist |

|---|---|

| Title | – Ensure the single-sentence title clearly states the study’s focus |

| Abstract (Words: 200) | – Briefly describe the research topicSummarize the research problem or question – Outline the research design and methods – Mention the expected outcomes and implications |

| Introduction (Words: 300) | – Introduce the research topic and its significance – Clearly state the research problem or question – Explain the purpose and objectives of the study – Provide a brief overview of |

| Literature Review (Words: 800) | – Gather the existing literature into themes and ket ideas – the themes and key ideas in the literature – Identify gaps or inconsistencies in the literature – Explain how the current study will contribute to the literature |

| Research Design and Methods (Words; 800) | – Describe the research paradigm (generally: positivism and interpretivism) – Describe the research design (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods) – Explain the data collection methods (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations) – Detail the sampling strategy and target population – Outline the data analysis techniques (e.g., statistical analysis, thematic analysis) – Outline your validity and reliability procedures – Outline your intended ethics procedures – Explain the study design’s limitations and justify your decisions |

| Timeline (Single page table) | – Provide an overview of the research timeline – Break down the study into stages with specific timeframes (e.g., data collection, analysis, report writing) – Include any relevant deadlines or milestones |

| Budget (200 words) | – Estimate the costs associated with the research project – Detail specific expenses (e.g., materials, participant incentives, travel costs) – Include any necessary justifications for the budget items – Mention any funding sources or grant applications |

| Expected Outcomes and Implications (200 words) | – Summarize the anticipated findings or results of the study – Discuss the potential implications of the findings for theory, practice, or policy – Describe any possible limitations of the study |

Your research proposal is where you really get going with your study. I’d strongly recommend working closely with your teacher in developing a research proposal that’s consistent with the requirements and culture of your institution, as in my experience it varies considerably. The above template is from my own courses that walk students through research proposals in a British School of Education.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

8 thoughts on “17 Research Proposal Examples”

Very excellent research proposals

very helpful

Very helpful

Dear Sir, I need some help to write an educational research proposal. Thank you.

Hi Levi, use the site search bar to ask a question and I’ll likely have a guide already written for your specific question. Thanks for reading!

very good research proposal

Thank you so much sir! ❤️

Very helpful 👌

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Verify originality of an essay

Get ideas for your paper

Cite sources with ease

Selection Of Top Research Proposal Topics In Education

Updated 25 Jul 2024

Talking about education is always tricky. It’s a large field where many things are happening globally. However, this means that there’s a lot of room for discovering new angles that can be interesting to discuss. Naturally, you want your proposal to be accepted so that you can start working on your research. Besides, writing an excellent research paper can gradually improve your grade and affect your further training and how well you develop as a student. Don't forget: a quality plagiarism detector is the need of the hour!

When the time comes it might be overwhelming to choose a topic for research proposal in the education sphere. The sheer amount of information and innovation can make it challenging to recognize the right one. This is why we’ve decided to share some essential advice on how to gain a clear understanding of what a research proposal is and choosing the perfect research proposal topic right for you.

How to Choose Topics For Research Proposal in Education

Below you’ll find some useful recommendations on how to choose the right topic for your research from research paper writing services EduBirdie.

Learn about the latest educational tendencies and changes.

As we mentioned earlier, it’s essential to keep up with the latest news in education. New things are constantly happening, and different news sources can instantly help you brainstorm your topics.

Check some real examples.

If you don’t have any ideas, go straight to the source. Attend a lecture at college or visit a school. See how teachers are using various methods and whether certain practices are used the right way. Sadly, there’s always a difference between theory and practice.

Look up for some topical literature.

Reading books about education is always a good idea. Not only can you find an exciting topic but also get research for it straight away.

Narrow it down.

Being specific helps you bring authenticity and makes your proposal look interesting. Don’t talk about education in general; find interesting pieces and see how to correlate to other factors.

Still have questions considering your proposal? Below you’ll find answers to some of the most common ones students usually ask.

What are some good research proposal topics in education?

A good example would be, “Is a teacher only supposed to educate or act as a moral guide as well?” The issue itself is very specific and comes in the form of a question that is always a good thing. At the same time, this topic has a broad capacity for discussion.

If you need further inspiration, you can find proposal essay examples related to education to help you formulate your own research proposal.

Get your paper in 3 hours!

- Customized writing: 100% original, personalized content.

- Expert editing: polished, standout work.

✔️ Zero AI. Guaranteed Turnitin success.

Top 50 List of Research Proposal Topics in Education

Curriculum and instruction.

- The Impact of STEM Education on Critical Thinking Skills

- Multicultural Education and Student Engagement

- Efficacy of Bilingual Education in Early Childhood

- Digital Literacy: Preparing Students for a Digital World

- The Role of Arts Education in Emotional Intelligence Development

- Inquiry-Based Learning vs. Traditional Teaching Methods

- The Effectiveness of Environmental Education Programs

- Integrating Coding into the Curriculum: Outcomes and Challenges

- Project-Based Learning: Enhancing Collaborative Skills

- Holistic Education: Benefits on Student Well-being

- The Impact of Homework on Academic Achievement

- Adapting Curriculum for Special Needs Students

- Culturally Responsive Teaching Practices

- The Role of Physical Education in Child Development

- Implementing Financial Literacy in High School Curriculum

- The Influence of Textbook Content on Historical Perspectives

- Teaching Critical Media Literacy in Schools

- Outdoor Education and Its Impact on Student Learning

- The Effectiveness of Character Education Programs

- Curriculum Design for Online Learning Environments

Educational Technology

- Virtual Reality in Education: Prospects and Limitations

- The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Personalized Learning

- Gamification in Education: Engagement and Learning Outcomes

- Mobile Learning Apps and Student Performance

- The Impact of Social Media on Learning and Socialization

- Technology Integration in Low-Resource Classrooms

- Online vs. Traditional Education: A Comparative Study

- The Use of Big Data in Educational Assessment

- Cybersecurity Education in Schools: Necessity and Implementation

- E-Learning Platforms: Effectiveness in Adult Education

- Augmented Reality for Enhancing Science Education

- Digital Divide: Access to Technology in Rural vs. Urban Schools

- The Future of MOOCs in Higher Education

- Wearable Technology in Physical Education

- Student Data Privacy in Digital Learning Tools

- Flipped Classroom Model: A Meta-Analysis

- Adaptive Learning Systems and Student Success

- The Role of Podcasts in Higher Education

- Blockchain Technology for Academic Credentials

- Smart Classrooms: Impact on Teacher-Student Interaction

Teacher Education and Professional Development

- Mentoring Programs for New Teachers: Best Practices

- Continuing Education for Teachers: Impact on Teaching Quality

- Teacher Perceptions of Professional Development Programs

- The Role of Reflective Practice in Teacher Education

- Teaching Strategies for Diverse Classrooms

- Impact of Teacher Leadership on School Culture

- Teacher Burnout: Causes, Effects, and Prevention Strategies

- Effective Models of Teacher Evaluation

- Integrating Emotional Intelligence Training for Teachers

- Professional Learning Communities: Enhancing Collaboration

- Teaching Ethics and Professional Responsibility

- Technology Training for Teachers: Adoption and Impact

- Cross-Cultural Competence in Teacher Education

- Strategies for Teaching in Multilingual Classrooms

- The Role of Teachers in Preventing Bullying

- Innovative Teaching Methods in Higher Education

- Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education

- Peer Coaching and Its Effect on Teaching Practice

- The Impact of Teacher Motivation on Student Achievement

- Developing Critical Thinking Skills in Teacher Education

Education Policy and Leadership

- Impact of Education Policies on Achievement Gaps

- School Leadership Styles and Their Effect on Teacher Morale

- The Role of Educational Leaders in Implementing Technology

- Education Reform: Lessons from Successful Systems

- The Influence of Policy on Early Childhood Education

- Charter Schools vs. Public Schools: A Policy Analysis

- Higher Education Funding Models and Their Implications

- The Effect of Standardized Testing on Curriculum Choices

- Policies for Addressing Mental Health in Schools

- The Role of Parental Involvement in Education Policy

- School Safety Policies and Their Impact on Learning Environment

- Equity and Access in Higher Education

- The Politics of Education Reform

- Community Involvement in School Leadership

- Education Policy and Its Impact on Teacher Retention

- The Future of Education Policy in a Globalized World

- Leadership in Special Education Administration

- The Role of School Boards in Educational Improvement

- Policy Approaches to Lifelong Learning

- The Impact of Immigration Policies on Education

Social and Cultural Issues in Education

- Gender Disparities in STEM Education

- The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Educational Achievement

- Cultural Competence in the Classroom

- Education as a Tool for Social Justice

- The Effects of Racial Bias in Educational Materials

- Language Barriers in Education for ESL Students

- The Role of Education in Social Mobility

- Addressing LGBTQ+ Issues in School Curricula

- The Educational Challenges of Refugee and Immigrant Students

- Social Media's Role in Shaping Youth Culture and Education

- The Influence of Family Structure on Educational Outcomes

- Cultural Identity and Its Impact on Learning

- Education and the Digital Divide: Bridging the Gap

- The Role of Schools in Promoting Community Engagement

- Educational Strategies for At-Risk Youth

- The Impact of Globalization on Education Systems

- Cultural Sensitivity Training for Educators

- The Role of Education in Combating Climate Change

- Social Class and Access to Higher Education

- Multicultural Education and Global Citizenship

EduBirdie is Here to Help You with Any Research Topics in Education

If you need research proposal writing help, we have hundreds of professional writers with expertise in the education field. Utilizing proposal writing services can help you craft a well-structured and persuasive proposal and also assist you with writing your whole research paper. Don’t hesitate to contact us, as we guarantee complete anonymity.

Was this helpful?

Thanks for your feedback, related blog posts, 200+ top sociology research topics.

Table of contents Research Methods of Sociology Tips on How to Choose a Good Topic for Sociology Research Sociology Research Topics I...

Best Capstone Project Ideas for Students across subjects

The most challenging aspect of crafting a top-tier capstone project is often getting started. The initial hurdle involves selecting a strong, impac...

How to Write a Movie Review: Tips for Aspiring Critics

If you wish to know how to write a movie review, then you are on the right page. A movie review forms part of essays college students writes. While...

Join our 150K of happy users

- Get original papers written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

The Edvocate

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- Write For Us

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Assistive Technology

- Best PreK-12 Schools in America

- Child Development

- Classroom Management

- Early Childhood

- EdTech & Innovation

- Education Leadership

- First Year Teachers

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Special Education

- Parental Involvement

- Policy & Reform

- Best Colleges and Universities

- Best College and University Programs

- HBCU’s

- Higher Education EdTech

- Higher Education

- International Education

- The Awards Process

- Finalists and Winners of The 2023 Tech Edvocate Awards

- Award Seals

- GPA Calculator for College

- GPA Calculator for High School

- Cumulative GPA Calculator

- Grade Calculator

- Weighted Grade Calculator

- Final Grade Calculator

- The Tech Edvocate

- AI Powered Personal Tutor

Universities, like banks, are too big to fail

Opinion | i’m a college president and i hope my campus is even more political this year, revolutionizing education through school-based healthcare, state set to revolutionise varsity education, funding, christian formation for the ‘toolbelt generation’, marie lynn miranda: public higher education is essential to training our future workforce, hear what the nation’s top student podcasters have to say, teaching students about socialism, teaching students about naturalism, teaching students about heartwood, how to write a research proposal.

As a professor of education, one of my favorite courses to teach was “Introduction to Education Research.” The primary purpose of this course is to introduce students to the concepts and methods of education research. The emphasis is placed on methods most frequently encountered in social science research, especially in the field of education. Students are expected complete a research proposal during this course, and in the follow-up course, “Applications of Education Research,” they use this proposal to conduct a research study.

Why did I love teaching this course? Because education research is not an easy skill to develop, but with hard work and dedication it can be mastered. When I was able to help someone who hated statistics learn to love statistics, it gave me a sense of accomplishment. In this piece, I plan to take you through the process of developing an education research proposal that you can be proud of.

Let’s start off by discussing research problems and questions and then moving on to the four main parts of a research proposal.

Research Problem and Question(s)

A research question is the core of a research project, study, or review of the literature. It centers the study, sets the methodology, and guides all stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting.

A research question starts with a research problem, an issue that you would like to know more about or change. Research problems can be:

- Areas of concern

- Conditions that need to be changed

- Difficulties that should be erased

- Questions that need to be answered

A research problem leads to a research question that:

- Is worth investigating

- Contributes knowledge & value to the field

- Improves educational practice

- Improves humanity

The key features of a good research question:

- The question is viable.

- The question has clarity.

- The question has gravitas.

- The question is moral.

How to Get From Research Problem to Research Questions and Purpose

The following section was originally published on a site entitled Research Rundowns :

Step 1. Draft a research question/hypothesis.

Example : What effects did 9/11/01 have on the future plans of students who were high school seniors at the time of the terrorist attacks?

Example (measurable) Questions: Did seniors consider enlisting in the military as a result of the attacks? Did seniors consider colleges closer to home as a result?

Step 2. Draft a purpose statement.

Example: The purpose of this study is to determine the effects of the 9/11/01 tragedy on the future plans of high school seniors.

Step 3. Revise and rewrite the research question/hypothesis.

Example : What is the association between 9/11/01 and future plans of high school seniors?

Step 4. Revise and rewrite the research question/hypothesis.

Example : Purpose Statement (Declarative): The purpose of this study is to explore the association between 9/11/01 and future plans of high school seniors.

Note: Both are neutral; they do not presume an association, either negative or positive.

Parts of a Research Proposal

A research proposal includes four sections, and they are as follows:

Section One: Introduction

Section Two: Review of the Literature

Section Three: Research Methodology

Section Four: References

The information that follows offers step by step instructions on how to complete each section of your proposal.

Part #1: Write a paragraph that introduces your topic. Mention your topic in the first sentence. What are you planning to study? What is the purpose of the study?

Part #2: Fully discuss your topic. What specifically interests you? Think of a specific research question (or questions) and state it clearly and precisely. You can also begin to formulate your ideas on how you might study your research question, though you need not be very specific in this section. For example, if you plan to study attitudes toward school vouchers, suggest what characteristics influence how individuals feel about school vouchers (e.g., income, location, etc.).

Part #3: Explain to the reader why it is important to study your topic and put it into a larger educational context. Here is where you answer the “So what?” question. That is, you plan to study XYZ. So what? Why is it important to study this topic? What is the educational importance of this research? Why is this study significant? This is your opportunity to be broad, general, and theoretical in your thinking.

This section should be at least 3-5 pages. Based on the outline provided above, you must utilize sub-headings within this section. You must cite articles within this section to support your topic and claim.

The purpose of this section is to find and summarize qualitative or quantitative research studies that directly relate to your research question(s). Use library databases to start searching for articles, but employ other resources when necessary.

When looking for articles, you need to adhere to the following guidelines:

- Use scholarly journals rather than popular magazines, newspaper articles, or the internet.

- Rely on the educational literature. If you are unsure whether an article or journal is included in the discipline, ask me.

- In general, select recent articles (i.e., 1960 or later). However, if an article was written in 1952, for example, is extremely pertinent to your proposal, then use it.

- Choose only research articles (qualitative or quantitative research) for the literature review. Do not include theoretical works, editorials, book reviews, program reports, etc. If you are unsure about an article, I will gladly take a look at it. Your literature review should not be more than 15 pages.

Your task is to:

- Briefly, restate your research topic in an opening paragraph. Provide a short introduction about what question(s) you are trying to answer, why this is educationally interesting, and why you chose it. Also, provide a brief overview of the topics you will cover in your literature review.

- Divide the literature that you have into sections of like Then, for each section, write an essay summarizing the studies. Be sure to state the research purpose, method(s), and findings ONLY for the studies that are paramount to your study. [NOTE: Use transitions within your essay so that it flows and does not appear like disjointed blocks of information.]

- Write a concluding paragraph that summarizes the articles. For example, how will these articles inform your research?

- DO NOT PLAGIARIZE.

The purpose of this section is to allow you to explain your research methodology. This can be the hardest part of the proposal for some students; therefore, do not wait until the last minute to write this section. Think about your design when you write your literature review.

- In a brief introduction, restate your research problem(s)/question(s).

- Indicate the following parts of your research methodology:

- Describe your vehicle of observation. How do you plan to collect your data? If you are creating a survey, what kinds of questions do you plan to ask? If you are going to do interviews, what will you ask of your interviewees?

- What population do you plan to use? How do you plan to sample this population?

- How will you select your sample? What kind of sampling method will you use?

- How will you analyze your data? What kind of analysis best fits your project, and why?

- If you plan to conduct qualitative research, discuss the following issues (be as detailed and accurate as possible):

- Define the theoretical constructs will you be using.

- What is the main concept you are investigating? What other concepts will be examined (note the concepts’ potential structures, processes, causes, and consequences)?

- What type(s) of qualitative analysis will you conduct?

- If you plan to conduct quantitative research, discuss the following issues (be as detailed and specific as possible):

- Clearly, state your hypotheses.

- Identify and operationalize your variables. List the independent variables and the dependent variable.

- List the pros and cons of your methodology.

- Write a concluding paragraph that summarizes the research design and proposal. When writing this section, imagine that have enough resources for your research design. Since you will not perform the research be creative, but appropriate, with your design.

On the last section of your proposal, include an APA-formatted bibliography of the articles, books, websites, etc. that you refer to in the text. This page should be titled “References.” The references should be listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. As a rule of thumb, you need an average of 4 references per page. For instance, if your proposal is ten pages, then technically need 40 references. However, this does not necessarily to have four references on each page.

Please carefully note the following issues: