College Reality Check

What is the PSAT? Practice Test Included

The PSAT stands for Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test. Administered by the College Board, it’s a standardized test that helps high school students prepare for a major college entrance exam and a prestigious merit-based scholarship.

Created as a practice test for high schoolers who are planning on taking the SAT, the PSAT helps boost college admissions chances by improving SAT performance. In addition, the PSAT serves as a qualifying exam for college-bound teens who are interested in winning the National Merit Scholarship Program.

This post contains some of the most essential things you need to know about the PSAT.

Is the PSAT Important for College Admissions?

The PSAT is not an important standardized test for college admissions. That’s because it’s not considered as one of those college admissions tests such as the SAT and ACT that test-required and test-optional institutions take into account in the admissions process. As a matter of fact, the College Board does not send PSAT scores to colleges.

While the PSAT won’t have a direct impact on your chances of getting an acceptance letter from your top-choice school, it can, however, determine your eligibility for the National Merit Scholarship.

Do You Have to Take the PSAT?

Some high schools require students to take the PSAT, and most of them take care of the registration fee, too. Otherwise, it’s completely up to the high schooler to decide whether or not they will sit for the PSAT.

However, being the PSAT/NMSQT, those who wish to apply for the National Merit Scholarship Program should take the standardized test in the 11th grade.

It may be a practice test for the SAT alright, but the PSAT is not a prerequisite for taking the SAT.

Read Also: 13 College Entrance Exams And When To Take Them

Can Colleges See How Many Times You Took the PSAT?

Colleges cannot see how many times applicants took the PSAT. Other than not being an important part of the college admissions process, the College Board does not send PSAT scores to institutions of higher education. Throughout their high school careers, teens can only take the PSAT, which is administered only once a year, up to 3 times.

For high schoolers who like to boost their chances of winning the National Merit Scholarship, taking the PSAT 1 or 2 times before their junior year may be done. It can also help increase their SAT scores and, ultimately, college admissions chances.

What is on the PSAT?

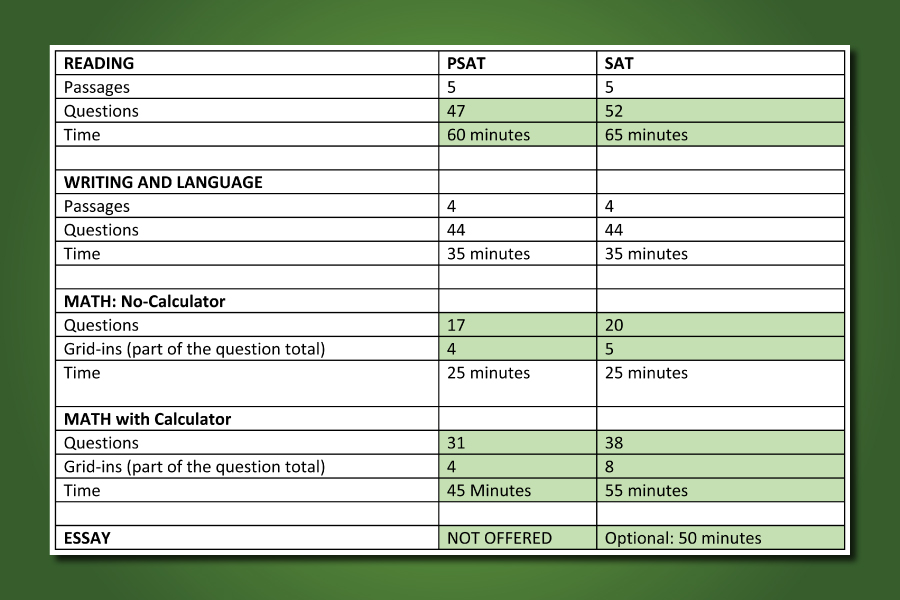

The components of the PSAT are the very same components of the SAT. After all, it serves as a practice test for the SAT. While it’s made up of 3 tests, there are only 2 primary sections of the PSAT: the Evidence-Based Reading & Writing (EWRB) and Math sections. However, unlike in the SAT, test-takers will encounter a few write-in questions, too, in the PSAT.

According to the PSAT website itself, some of the math questions will require you to write an answer instead of choosing it.

How Many Sections are on the PSAT?

The 2 main sections of the PSAT are the EWRB section and the Math section. The EBRW section is made up of Reading and Writing & Language. The Math section, on the other hand, consists of 2 sub-sections: the no-calculator section and the calculator-optional section. There is no optional Essay section on the PSAT, such as the case with the SAT in the past.

Even though the PSAT is a slightly shorter and slightly easier version of the SAT, therefore making it a practice test, both standardized tests are pretty much similar. And that is why the PSAT can help prepare you better for the SAT.

How Many Questions is the PSAT?

The PSAT has a total of 139 questions — the vast majority of them are multiple-choice questions, while a few of them, which are found in the Math section of the PSAT, are write-in questions. Of all the sections, the Math section has the most number of questions. The Writing & Language component of the EWRB section, meanwhile, has the least number of questions.

Here’s a table showing the number of questions each section of the PSAT has:

| Reading | 47 |

| Writing & Language | 44 |

| Math | 48 (31 for the calculator-optional section and 17 for the no-calculator section) |

What Kind of Math is on the PSAT?

The Math section of the PSAT focuses on various areas of mathematics that play the biggest role in numerous academic majors and minors. The College Board refers to the various types of math included in the PSAT as Heart of Algebra, Problem Solving and Data Analysis, Passport to Advanced Math and Additional Topics in Math.

Below is a description of the math kinds you will encounter when sitting for the PSAT:

- Heart of Algebra – knowledge of linear equations and systems

- Problem Solving and Data Analysis – problem analysis and obtaining information from data

- Passport to Advanced Math – questions involving the manipulation of equations

- Additional Topics in Math – college-relevant geometry and trigonometry

Is There Science on the PSAT?

Even though there is no section on the PSAT that’s dedicated to science, some passages are science-related. For instance, the Reading portion of the EBRW section has either 1 or 2 science passages as well as a set of paired science passages, all of which contain a lot of technical terms and jargon that set them apart from other passages.

Both the PSAT and SAT do not have any science sections. On the other hand, the ACT has a science section, which makes it more appealing to some high school teens who consider science as their strength.

Is There Writing on the PSAT?

The PSAT has a Writing section, which is a part of the Writing & Language component of the EBRW section. The Writing section requires test-takers to read passages and then find mistakes and/or weaknesses and correct them. Despite the name, the Writing section contains multiple-choice questions and does not require students to write something.

An argument, informative or explanatory text, or a nonfiction narrative — these are the kinds of passages you will have to carefully read to answer the questions in the PSAT’s Writing section.

How Does the PSAT Work?

In this part of the post, we will discuss various things related to taking the PSAT, including how your test will be scored and what score you should get to impress colleges and qualify for the National Merit Scholarship.

What Does the PSAT Measure?

The PSAT is structured very similarly to the SAT, for which it serves as a practice test. It goes without saying that the PSAT is designed to measure the same things that the SAT is meant to measure. They are reading, writing and math skills that high school students learn in the classroom, all of which are necessary for college and career success.

Because the PSAT can be taken in as early as the 9th grade, the PSAT cannot necessarily determine a student’s college readiness. However, it can help ascertain whether or not a teen is on the right track through grade-level benchmarks.

Is the PSAT Multiple Choice?

Most of the questions on the PSAT are multiple-choice kinds, and each multiple-choice question is accompanied by 4 answer choices. While there are multiple-choice questions in the Math section of the PSAT, some of them require test-takers to write in their answers rather than select them. All in all, there are 8 write-in questions on the PSAT.

Questions where students have to provide their responses are also referred to as grid-in questions or simply grid-ins as they need to enter their answers in the grids found on the answer sheet.

Is the PSAT a Standardized Test?

The PSAT is a standardized test because it is given to high schoolers in a consistent or standard fashion. This means that all the questions on the test are all the same for all students no matter which high school they are attending.

Also making the PSAT a standardized type of examination is the fact that it’s scored the same for all those who take it.

Being the PSAT/NMSQT, the PSAT is also a standardized eligibility exam for the National Merit Scholarship.

When Do You Take the PSAT Test?

Most high school students take the PSAT in the 11th grade. Other than giving them practice for the SAT, it also enables them to be considered for the National Merit Scholarship Program.

However, the PSAT can also be taken during the freshman and sophomore years of high school, but it won’t serve as a qualifying exam for the National Merit Scholarship.

There is no use for any high schooler to take the PSAT in the 12th grade.

How to Guess on the PSAT

The right way to guess on the PSAT is to eliminate at least 1 incorrect answer among the answer choices, which gives the test-taker 1 in 3 chances of making the right guess. On the other hand, eliminating 2 incorrect answers among the answer choices makes it possible for the student taking the PSAT to get the right answer on a 50/50 basis.

Because there is no wrong-answer penalty on the PSAT, it’s generally a good idea for high schoolers who don’t know the answer to make a guess instead of leaving a question unanswered.

How Long is the PSAT?

It takes 2 hours and 45 minutes (with breaks) to complete taking the PSAT. Test-takers are given 70 minutes to complete the Math section, which has a total of 48 questions — 31 questions for the calculator-optional section and 17 questions for the no-calculator section.

Meanwhile, students have up to 95 minutes to complete the EBRW section, which has a total of 91 questions.

Here’s a table showing the breakdown of the PSAT’s testing time:

| Reading | 60 minutes |

| Writing & Language | 35 minutes |

| Math | 70 minutes |

How Does PSAT Scoring Work?

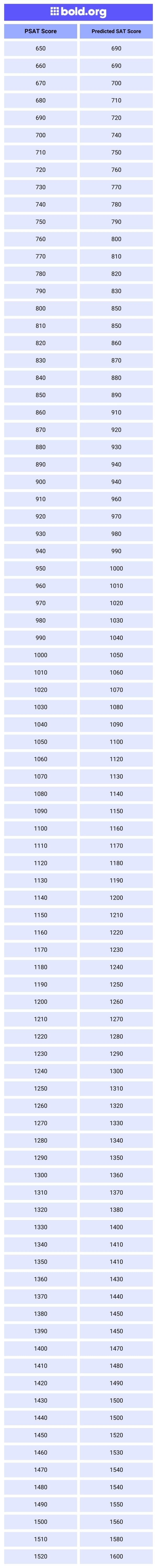

Each section of the PSAT is scored on a scale of as low as 160 to as high as 760. The scores test-takers get in both sections of the standardized test are added, resulting in their PSAT composite score. So, in other words, the overall PSAT score can range anywhere from 320 to 1520, which may help predict the SAT composite scores of a test-taker.

There is no such thing as a failing score on the PSAT.

What is a Good PSAT Score?

Generally speaking, a good PSAT score is a composite score of 1070 or higher, which puts the high school student in the top 25% of all test-takers. An excellent score, which is between 1210 and 1520, puts the teen in the top 10% of all test-takers. For eligibility for the National Merit Scholarship Program, a student must be in the top 1% of all test-takers.

Other than increasing your chances of getting an SAT composite score that can help you get into your top-choice college, getting a high PSAT score can also make it possible for you to win the National Merit Scholarship.

Facts About the PSAT

Let’s talk about some important matters you need to know about the PSAT, including its beginnings, how many high school students take it every year and whether or not it comes with an optional Essay section.

History of the PSAT

The PSAT, like the SAT, was created by the College Board. It was in 1959 when the PSAT was administered for the very first time.

In 1971, the National Merit Scholarship Program, which is a US academic scholarship competition for recognition and university scholarships and is not related to the College Board, adopted the PSAT as its qualifying examination.

More than 30 years after the SAT came into being, the PSAT was administered to help high school students prepare for the SAT. In the past, some intellectual clubs used PSAT scores in admitting new members.

Who Created the PSAT?

It was the College Board that designed the PSAT, whose goal was to serve as a preliminary exam for the SAT. The non-profit organization decided to come up with the standardized test to provide high school students with the opportunity to prepare for the SAT and thus allow them to increase their chances of getting admitted to college.

Eventually, as mentioned earlier, it was used as a qualifying test for the National Merit Scholarship.

What is the College Board?

The College Board is an organization that designs and administers standardized tests as well as develops curricula for use by K-12 and institutions of higher education for the promotion of college readiness. The non-profit was established in 1900 by representatives of a total of 13 academic institutions at the University of Columbia.

Although it’s not an association of colleges, many postsecondary institutions are members of the College Board. As of this writing, there are more than 6,000 schools that are approved members.

How Many People Take the PSAT?

Around 3.5 million high school students take the PSAT. They consist of sophomore and junior high schoolers across the US. The College Board itself says that in the academic year 2021 to 2022, around 3.6 million students took the PSAT.

Meanwhile, over 1.5 million entrants for The National Merit Scholarship Program who meet other requirements take the PSAT.

More high schoolers take the SAT than the ACT. It’s therefore safe to assume that more students also take the PSAT than the PreACT, which is the counterpart of the PSAT.

What is the PSAT Designed to Predict?

The PSAT is designed to predict the SAT scores of high school students and, ultimately, their college readiness given that the SAT is primarily designed for such a purpose.

By taking the PSAT, test-takers know their strong points and, more importantly, their weak spots so that they can take the necessary steps to prepare for the SAT and get good scores.

Want to have an idea of how you may score on the SAT based on your PSAT scores? Online, you can easily access PSAT to SAT conversion tools and charts, most of which are free of charge.

Does the PSAT Have an Essay?

There is no Essay section of the PSAT. The standardized test has 2 main sections, the EBRW section and Math section, and nothing else. In the past, the SAT used to have an optional Essay section but the College Board decided to stop offering it altogether.

On the other hand, the PSAT never had an optional Essay section from the get-go.

Preparing for the Essay section on the SAT by means of an Essay section on the PSAT is completely pointless given that the said section of the SAT became optional in 2016 and unavailable in 2021.

Does the PSAT Provide Calculators?

The PSAT does not provide test-takers calculators. High school students who are sitting for the PSAT must bring their own approved calculators with them to their respective high schools, where the PSATs are administered. Similarly, test-takers are not allowed to share calculators and use them on the Math no-calculator portion and EBRW portion.

Here’s a list of all allowed calculator models from the College Board itself.

PSAT is Changing – Paper Based vs. Digital

The PSAT will be administered in digital format, and its paper and pencil format will cease to exist.

Since it was first taken by students preparing for the SAT back in 1959, it underwent 3 major changes in its format and content as well as how it’s scored. The said changes happened in 1997, 2005 and 2015.

In the fall of 2023, the PSAT will once again go through a significant change in that it will be administered in digital format.

The College Board chose the said date so that high school students who will be taking the digital SAT as juniors in the spring of 2024 will have the opportunity to experience what it’s like to take the standardized test in its entirely new format.

The National Merit Scholarship Program will still use the digital PSAT as its qualifying exam.

When Does the PSAT Go Digital?

As mentioned earlier, the PSAT will go digital in the fall of 2023. From that time onward, the paper and pencil format of the PSAT will no longer be made available by the College Board.

How to Study for the PSAT

According to the PSAT website itself, studying for the standardized test requires making a study plan, creating a realistic goal, taking practice tests and targeting areas that require improvement.

It’s a good thing that free PSAT test preps are available from the College Board and various sources, too.

Undergoing practice tests when preparing for the PSAT is an important step high school teeners should take. Not only will it allow them to become familiar with the PSAT exam experience but also enable them to determine areas that require more attention. This way, they can quit wasting time reviewing things they already know.

It’s recommended to start gearing up for the PSAT about 3 months before the test date. However, it’s a smart move to start preparing for it, which is administered every October of the year, at the start of the school year.

PSAT Practice Test

In this part of the post, I will give you a total of 10 sample PSAT questions — 5 of them are from the Writing & Language portion of the EWRB section, while the other 5 are from the Math section.

Let’s start with a short reading passage:

Vanishing Honeybees: A Threat to Global Agriculture

Honeybees play an important role in the agriculture industry by pollinating crops. An October 2006 study found that as much as one-third of global agriculture depends on animal pollination, including honeybee (12) pollination — to increase crop output. The importance of bees (13) highlights the potentially disastrous affects of an emerging, unexplained crisis: entire colonies of honeybees are dying off without warning.

(14) They know it as colony collapse disorder (CCD), this phenomenon will have a detrimental impact on global agriculture if its causes and solutions are not determined. Since the emergence of CCD around 2006, bee mortality rates have (15) exceeded 25 percent of the population each winter. There was one sign of hope: during the 2010–2012 winter seasons, bee mortality rates decreased slightly, and beekeepers speculated that the colonies would recover. Yet in the winter of 2012–2013, the (16) portion of the bee population lost fell nearly 10 percent in the United States, with a loss of 31 percent of the colonies that pollinate crops.

Q 4. Which choice offers the most accurate interpretation of the data in the chart?

Q 5. Which choice offers an accurate interpretation of the data in the chart?

Answer key:

The following, meanwhile, are 5 sample test questions for the PSAT’s Math portion:

1. A soda company is filling bottles of soda from a tank that contains 500 gallons of soda. At most, how many 20-ounce bottles can be filled from the tank? (1 gallon = 128 ounces)

2. A car traveled at an average speed of 80 miles per hour for 3 hours and consumed fuel at a rate of 34 miles per gallon. Approximately how many gallons of fuel did the car use for the entire 3-hour trip?

3. A high school basketball team won exactly 65 percent of the games it played during last season. Which of the following could be the total number of games the team played last season?

4. Janice puts a fence around her rectangular garden. The garden has a length that is 9 feet less than 3 times its width. What is the perimeter of Janice’s fence if the area of her garden is 5,670 square feet?

5. Tyra subscribes to an online gaming service that charges a monthly fee of $5.00 and $0.25 per hour for time spent playing premium games. Which of the following functions gives Tyra’s cost, in dollars, for a month in which she spends x hours playing premium games?

The sample questions above are from the following site: satsuite.collegeboard.org

Should I Take the PSAT?

In some instances, high schoolers have no choice but to take the PSAT, which costs $18, because the schools they are attending require it — most of the time, though, high schools take care of the registration cost.

Otherwise, it’s completely up to the students to decide whether or not to sit for the PSAT.

Taking the PSAT, however, comes with benefits. For instance, since it’s designed as a preliminary exam for the SAT, teens who undergo it can prepare much better for the SAT, thus allowing them to get good scores and increase their college admissions chances. High PSAT scores also allow high schoolers to qualify for the National Merit Scholarship Program.

Read Next: What is SAT?

Independent Education Consultant, Editor-in-chief. I have a graduate degree in Electrical Engineering and training in College Counseling. Member of American School Counselor Association (ASCA).

Similar Posts

Digital SAT vs. Paper Based: Differences and Similarities

12 Things To Bring to the SAT Test: My Checklist

10 Best SAT Practice Tests To Take

Is It Bad to Fail the SAT? Consider These 5 Things

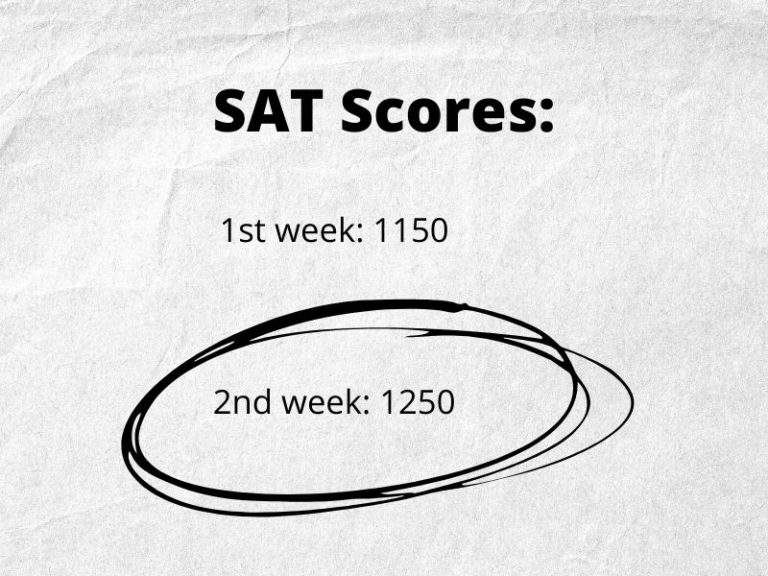

Is It Possible to Raise SAT Score by 100 Points in a Week?

SAT for Test-Optional School: Who and When Should Submit

The Parents Guide to PSAT/NMSQT

College Board

- May 1, 2022

- Last Updated June 30, 2023

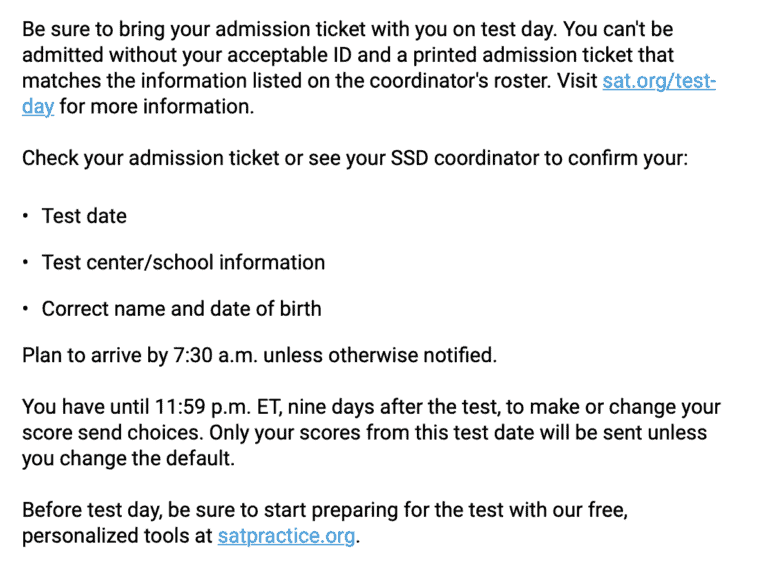

The Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test ( PSAT/NMSQT ® ) is structured similarly to the SAT ® , has the same sections and timing, and measures the same Reading and Writing and Math skills students learn in the classroom—the knowledge and skills your child needs to succeed in college and career. See what’s on the PSAT/NMSQT test.

Beginning in fall 2023, the PSAT/NMSQT is going digital. The SAT will follow in spring 2024. Find out what to expect.

Why the PSAT/NMSQT Is Important

Taking the PSAT/NMSQT is more than just good practice for the SAT, and the scores are more than just a number. With your child’s results, they can:

- See where they are and set a target : You’ll get details on the exact skills and knowledge they need to focus on, while they have plenty of time to improve. If they’ve taken the PSAT 8/9 or PSAT 10, they’ll also see how much progress they’ve made between the tests. They can also use their score from the PSAT/NMSQT, along with some research about their college and career goals, to set their own personal target SAT score . Historically, students who took the PSAT/NMSQT scored better on the SAT, on average, than those who didn’t take the test.

- Find out about their AP Potential : Students who take an AP ® course are better positioned to succeed in college. Your child may not realize that they’re ready to take college level courses and that they have the potential to succeed. Using their personalized view of AP Potential , found in their score report, they’ll get recommendations for courses that may be a good fit for them.

- Enter the National Merit Scholarship Program: Students who take the PSAT/NMSQT and meet other program entry requirements specified in the PSAT/NMSQT Student Guide will enter the National Merit ® Scholarship Program, an academic competition for recognition and scholarships conducted by National Merit Scholarship Corporation (NMSC ® ) Visit NMSC’s website at www.nationalmerit.org for more information..

- Help pay for college: Taking the PSAT/NMSQT gives your child the chance to access over $300 million in other scholarship opportunities .

- Connect to their future: When your child takes the PSAT/NMSQT, they’ll be asked for their mobile phone number so they can download the free BigFuture School™ mobile app and have their PSAT/NMSQT scores delivered right to their phone. They’ll get customized career information and guidance about planning and paying for college. Depending on their school or district, they can use the Connections feature, which lets them here from nonprofit colleges, scholarships and educational organizations interested in them—without having to share any personal information.

- The 2023 PSAT/NMSQT will be given throughout the month of October. Schools may offer the test to different groups of students during the month.

- The only way your child can sign up for the PSAT/NMSQT is through their school—not through College Board. Each school's signup process differs, so your child should talk to their school counselor to learn more.

- Some students pay a small fee to take the PSAT/NMSQT, but many students have test-related fees covered in full or in part by their school. If your child qualifies for a PSAT/NMSQT fee waiver, they test for free. For more information, talk to your child's school counselor.

- Homeschooled students can sign up and take the test at a local school.

- We never send PSAT/NMSQT scores to colleges.

How to Prepare for the PSAT/NMSQT

The best way your child can prepare for the PSAT/NMSQT is to pay attention in their high school classes and study the course material. Students who do well in school are likely to do well on the PSAT/NMSQT.

To become familiar with the test and its format, students can sign into the Bluebook ™ testing app and head to the Practice and Prepare section. They can explore the tools and features of the app and try a few sample questions in the test preview or take a full-length practice test. Then, they can review their results at mypractice.collegeboard.org. Once they know what knowledge and skills they need to work on, they can use Official digital SAT Prep on Khan Academy . It's a free, interactive study tool that provides personalized practice resources that focuses on exactly what your child needs to stay on track for college and career.

PSAT/NMSQT Scores

PSAT/NMSQT scores are available in November. In addition to getting direct access to their scores in the BigFuture School mobile app, your child will get a pdf score report from their school (if they don’t, they can ask their school counselor for it). And they can log intoinsights about their scores and explore Big Future . their personal College Board account at studentscores.collegeboard.org to get additional

Scores range from 320 to 1520 and are on the same score scale as the SAT. This means that a score of 1100 on the PSAT/NMSQT is equivalent to a score of 1100 on the SAT. The only difference is that SAT scores range from 400 to 1600, because the difficulty level of the questions is higher than on the PSAT/NMSQT.

Students also receive a PSAT/NMSQT Selection Index score, which National Merit Scholarship Corporation uses as an initial screen of students to the National Merit Scholarship Program. The Selection Index score is calculated from the Reading and Writing and Math section scores and ranges from 48 to 228.

Who Sees PSAT/NMSQT Scores

We don't send PSAT/NMSQT scores to colleges. We only send your child’s PSAT/NMSQT score to:

- Their school (always), school district (often), and state (often)

- National Merit Scholarship Corporation

- Select scholarship and recognition programs (your child may opt out of)

If you want to log in yourself to see your child's score report, use the email and password your child used when they set up their College Board online account.

Once your child gets their score report, they should sit down with you and go over it. That way, you both know what to focus on to be ready for college.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many times can a student take the psat/nmsqt.

Most students take the PSAT/NMSQT once—in 11th grade. Some schools also offer it to students in 10th grade. They can take it only once per school year. Some scholarship programs only look at the junior year PSAT/NMSQT score.

Can ninth graders take the PSAT/NMSQT?

Yes, but only certain students (typically students in 11th grade) are eligible to enter the National Merit Scholarship Program, as described in the PSAT/NMSQT Student Guide . The PSAT/NMSQT is designed to be grade appropriate for 10th and 11th graders.

Some schools offer the PSAT 8/9, which tests the same skills as the PSAT/NMSQT, but in ways that are appropriate for earlier grade levels. Check with your child's school counselor to see if your school offers the PSAT 8/9.

Does the PSAT/NMSQT have an essay?

No, the PSAT/NMSQT does not have an essay.

Related Posts

College Planning

College Planning Help for Homeschoolers

What's a good psat/nmsqt score.

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

We are experiencing sporadically slow performance in our online tools, which you may notice when working in your dashboard. Our team is fully engaged and actively working to improve your online experience. If you are experiencing a connectivity issue, we recommend you try again in 10-15 minutes. We will update this space when the issue is resolved.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., why you should take the psat.

Once upon a time, the standardized test known as the PSAT was viewed as a mini-SAT. And it was, literally, a “mini” version of the exam—a full hour shorter than the SAT. That’s no longer the case.

Taking The PSAT Today

When folks talk about the PSAT, they typically mean the test students take during junior year. Its full name is the PSAT/NMSQT, which stands for Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test. Here’s a quick breakdown of the three PSAT varieties:

Should You Take the PSAT?

Preparing for the psat.

- PSAT

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

PSAT Practice: How to Prepare and Why You Should

What, exactly, will we look at in this post? First, we’ll start out with some PSAT basics: what, when, why. Then, we’ll take a deep dive into PSAT tips for prep: what you’ll see on the test and how to set yourself up for a great score. We’ll finish up with some PSAT questions and PSAT tips.

Ready? Let’s go!

Table of Contents

What is the psat.

- When Is the PSAT?

What Does the PSAT Test?

How hard is the psat, psat tips for prep 1: evaluate whether you need to prep, psat tips for prep 2: set up your practice schedule, psat tips for prep 3: master content from each section, psat tips for prep 4: work with the correct timing, psat tips for prep 5: use great materials, how can i cram for the psat, how can i practice for the psat over the summer, a final word, psat tips: mastering the basics.

When Do I Take the PSAT?

If you have siblings or friends who have taken the SAT, you might be surprised to learn that, unlike that test, the PSAT/NMSQT, which is commonly taken the year before the SAT, is given only on one date, as determined by the school administering the test in combination with the College Board.

Usually, the PSAT is offered on a Wednesday in October or November. In 2020, the dates the PSAT was offered included Wednesday, October 14; Saturday, October 17; and Wednesday, October 29. Be careful, though: your school will pick one of these dates and have the other as a backup, so make sure you know which day the main test administration will take place by talking to your guidance counselor or the person in charge of the PSAT at your school.

The PSAT is also the qualifying test for the National Merit Scholarship , one of the more prestigious scholarships in the United States. (For this reason, the PSAT is also sometimes called The National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test.) This exam is offered every October and can only be taken once per year.

The PSAT has the exact same sections as the actual SAT. This means that PSAT questions are really similar to SAT questions—there are just fewer of them. There is a math component and a verbal component . The latter consists of both grammar exercises and reading passages. This is a change from the previous version of the PSAT, which I’ll talk about in a minute.

It’s also important to note that the PSAT is not made up of facts that you simply have to cram into your brain and then retrieve test day. It’s about applying rules and concepts to questions that are designed not to be straightforward.

Essentially, you’ll have to use a lot of critical thinking for PSAT questions. For instance, a math word problem won’t be a case of plugging the numbers into a predetermined formula. The information is always different and you’ll have to devise an equation to fit the specific circumstances. Unlike the bread-and-butter three-line word problems you might be used to seeing in math class, some of the math word problems can run close to 15 lines.

Here’s a deeper dive into the subjects you’ll see on the PSAT!

The Reading Test

There are two things to consider when examining the Reading Test: what kinds of passages the test includes and which skills it measures.

As for the first category, you can expect to see at least one literature passage—this can come from anywhere in the world and from any time period. You’ll also see a passage, or a passage pair , from a U.S. founding document (like the Constitution) or a text from the Great Global Conversation (like a speech by a world leader). Two science passages will appear, but they’ll test your reading ability, rather than your science knowledge. Finally, there’ll be a social science text.

In terms of the types of questions you’ll see, be prepared to show your ability to find evidence in the passage and show how authors use it. The test will also ask you to define vocabulary words based on their contexts . Finally, some of the passages will ask you to analyze data and charts from science or social science passages.

The Writing and Language Test

For the Writing and Language Test, you only have one goal for your PSAT questions: find the mistakes in the sentences you’re reading and select the answer that fixes them. Basically, the test looks at your command of grammar and usage , but it also measures those same categories from the Reading Test: command of evidence, words in context, and analysis of additional materials.

The Math Test

The Math Test examines three big categories of PSAT questions: Heart of Algebra , Problem Solving and Data Analysis , and Passport to Advanced Math (all of which will be mixed together, and none of which will be labeled). Let’s look at what each of those areas covers.

In the Heart of Algebra questions, expect to see a linear expression or an equation with one variable. You will also be asked to work with linear inequalities with one variable. You’ll build a linear function to show the relationship between two quantities. You’ll do similar work then with a variety of other equations, some of which may have two variables or include two linear variables.

Problem Solving and Data Analysis will include an entirely different set of topics. These include: ratios, rates, proportions, percentages, measurements, units, unit conversions, scatterplots, relationships between two variables linear versus exponential growth, two-way tables, making inferences from data and statistics (this might include mean, media, mode, range, and/or standard deviation), and evaluating data collection methods. Whew!

How Is the PSAT Different from the SAT?

The PSAT is basically an SAT with smaller teeth and a less overwhelming purpose (it can get you scholarships, but it doesn’t get you acceptance into college). All of the same basic SAT topics show up in PSAT questions, minus a bit of the higher-level stuff, especially in math.

The PSAT is a tad easier than its big brother, but the difference is pretty minimal. It’s all toned down slightly, though. Questions that would be on the easy end of SAT math show up more frequently on the PSAT. You might get 5 questions on PSAT math that are as easy as the first 2 questions of an SAT math test, for example. And the most difficult PSAT questions don’t quite reach the difficulty of the hardest SAT math questions.

The higher end of SAT math topics might still show up on the PSAT, but they’ll be more straightforward. You’ll see easier “Passport to Advanced Math” questions, for example, and you may see only one very basic trig question. Or you might get a graph of a parabola that simply asks for an intercept and requires no algebra.

PSAT Tips for Prep

The PSAT is a preliminary SAT—it isn’t used in college admission—so you might be wondering: is it even worth prepping for the test? What’s the point of studying for a test that colleges won’t even look at?

There are actually two really important reasons to study for the PSAT! First of all, remember that it’s not just the PSAT—it’s also the NMSQT, or the National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test. If you’re a junior, prepping for the test can set up you for a far higher score, putting you in the running for more money for college.

If you’re a sophomore, that’s still a great reason to prepare! Think about it this way: your scores on the PSAT this year will help you get a better idea of what prep you’ll need to do within the next year to reach that qualifying range. If you prep beforehand, it’ll not only set you up for greater success as a junior, but you can also tailor your study this coming year to really focus on your weaker areas, now that you’ve mastered PSAT tips.

Ideally, your practice will consist of a mixture of fundamentals and practice questions, with some test strategy (PSAT tips and tricks) thrown in. For instance, you’ll want to revisit algebra concepts you learned a year back, or are maybe learning right now before you tackle actual test questions.

You don’t want to spend too much time on fundamentals, however. Throw yourself into practice questions to get a feel for the way the test works. Often a good idea is when you miss a PSAT question to review the fundamentals at work, assuming you didn’t make a careless error. That’s better than trying to memorize a bunch of fundamentals but then waiting an indefinite period before actually reviewing them.

The skills that the SAT tests are almost exactly the same that you’ll need to practice on the PSAT . Even the types of questions are the same. In both tests, you’ll see Math and Evidence-Based Reading and Writing.

Math PSAT Prep

- Multiple choice

- Grid-in (Write your own answer)

- A no-calculator section

Reading PSAT Practice

- Reading comprehension of both fiction and non-fiction (including one text from “U.S. Founding Documents and the Great Global Conversation”)

- Long-ish passages of 500-750 words (including one paired set of passages)

- Informational graphics questions

- Words in context questions

- Command of evidence questions

Writing and Language PSAT Prep

- Expression of ideas (rhetorical) questions

- Standard English conventions (grammar) questions

That means that studying for the PSAT is a good way to get ready for the SAT while you are a junior (and the PSAT 8/9 and PSAT 10 for younger grades can help you get ready even earlier). The scores and subscores you receive can help you determine what you need to study and how long you need to study for the real deal.

Our biggest PSAT tip if you’re studying with SAT materials? Make sure you get the timing right!

How long is the PSAT? 2 hours and 45 minutes overall. This means that the PSAT is only just a little bit shorter than the SAT (without the essay anyway), so you’ll need to bring the same level of stamina to the PSAT as you will to the SAT. Pacing on both tests (in terms of the amount of time you have to answer each question) is comparable as well, so you aren’t going to get more time to answer questions on the PSAT.

| PSAT | SAT | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Length | 2 hours 45 minutes | 3 hours (or 3 hours 50 minutes with the optional essay) |

| Reading | 60 minutes | 65 minutes |

| Writing & Language | 35 minutes | 35 minutes |

| Math | 70 minutes (including a calculator and a no calculator section) | 80 minutes (including a calculator and a no calculator section) |

| Essay | None | 50 minute analytical essay (optional) |

Make sure to do your research on practice materials. The best bet is to use SAT practice materials since the questions that pop up on each test are indistinguishable. It is the ordering of the difficulty of the questions that differs between the two tests.

While you should definitely check out the College Board official resources for the PSAT , because the content is so similar, using SAT study materials is also a perfectly good way to study for the PSAT. Just make sure to follow the PSAT tips above and adapt the SAT materials to PSAT timing.

The PSAT will give you a leg-up on test day (and probably a Wednesday morning you don’t have to spend in class). And if you think you can score in the top range, you can also benefit from the Student Search Service (colleges will come looking for you and your awesome test scores) and the National Merit and other scholarship programs , which can earn you some scholarship money along with a pretty sweet feather in your cap. So give it your all!

First of all, it’s almost impossible to “cram” for the PSAT…but if you have limited practice time, here are our top PSAT tips to get the most out of your prep!

PSAT Cramming Tip #1: Take Practice Test(s)

Take a PSAT practice test. Take two, if you can. Heck, why stop at the PSAT? Take a full-length SAT . It’s an hour and a half longer than the PSAT, sure, but that’s basically the same as putting weights on your bat when practicing your swing.

That’s not groundbreaking advice by itself, though. The important part (the part you might be tempted to skip, too) is reviewing the answers . Take the time to figure out what you did wrong, and how you can avoid it. Even if you’ve only got a few days, that’s enough time to learn from your mistakes.

PSAT Cramming Tip #2: Study Vocabulary

Who knows why the College Board ever thought it was appropriate to put words like “clandestine” and “truculent” on their tests, but they did. The good news is that learning vocab by rote memorization is pretty effective in the short term.

That strategy alone is not ideal for long-term growth, and if you want to really bring up your scores significantly, building your vocabulary more organically (by reading a ton) is a better choice, but if your test is in a week, it’s time to break out those vocabulary flashcards .

PSAT Cramming Tip #3: Know Your Grammar Rules

This is pretty much the same idea as memorizing vocabulary. Most high-school teachers don’t spend much time on grammar, which is a shame because A) it will affect everything you ever write (seriously) and B) standardized tests like the PSAT love grammar.

You don’t have to diagram sentences, but you do have to know the common errors . There’s a limited number of them, so it’s pretty manageable to just read up on them and come away with an improved test score—provided you do a bit of practice along the way.

PSAT Cramming Tip #4: Review Math Formulas

I would never suggest that a student with ample time to study and practice instead memorize a bunch of formulas. Actually getting better at PSAT math means training and learning from mistakes (as I mentioned in #1, above). But if you’re running on a tight schedule, this is the fastest way to review what’s in the PSAT math sections.

School’s out for summer! And by now, you’re several weeks into your summer break. If you haven’t started some summer PSAT studying, you should. Here are a few reasons summer is a great time for both fun and a little bit of test prep.

Why is the PSAT’s Fall date a good reason for PSAT summer study? Because summer leads into fall! If you start studying for the PSAT at some point in the summer, you’ll have weeks or months of study time before Fall arrives and it’s time to take the PSAT.

And yes, I did say weeks or months. The best part about summer PSAT studying is that you don’t have to study all summer. You could choose to really focus on your PSAT study in the month of August. Or you start your PSAT study earlier in June or July, if stretching your studies over the whole summer works better for you.

Here’s one of our key PSAT tips: it’s easier to focus on test practice if you don’t have other homework. Summer is a time of minimal academic stress. And when you’re less stressed out, it’s easier to focus on mastering an exam.

During the school year, anytime you’re studying for a test, you have to balance your test practice with homework from other classes. But in the summer, you don’t even have to attend other classes, much less do other homework. This gives you a unique opportunity to just focus on the PSAT, with no other stressful distractions.

And bear in mind that preparing for the PSAT is not as time-consuming as regular high school studies. You’ll still have plenty of time for summer fun between your PSAT practice sessions. And that summer fun can keep you energized and focused when you study.

Unique PSAT study opportunities are available in the summer . Speaking of classes, it’s much easier to enroll in a PSAT practice course in the summer. Private tutoring centers and test practice academies keep longer hours in the summer. And you have more chances to go to these places for test practice during the day, instead of later in the evening when you’re more tired and less able to concentrate on your studies. Not only that, but there are also a lot of summer camps for PSAT and SAT prep.

And speaking of studying the PSAT and SAT together…

FAQ: Answers to Your PSAT Questions

Can i skip the psat.

The short answer to that question is yes—if all you want to do is take the SAT, you don’t have to take the PSAT first. But don’t get ready to pass PSAT and go straight to SAT just yet– there are a lot of advantages to taking the PSAT, even though it’s not strictly mandatory.

You shouldn’t skip the PSAT if you want to enter into the National Merit Scholarship contest. This is because the PSAT actually is a requirement for entry into this prestigious competition. To be a National Merit contender, you must take the PSAT in your junior year. This stage cannot be skipped.

You should also consider the PSAT as part of your journey to college acceptance if you want to practice for the SAT under very real test conditions. The PSAT is very comparable to the SAT in terms of difficulty. There are also conversion tables that translate PSAT scores into SAT equivalents, so you can measure your progress toward SAT success.

Moreover, the PSAT costs just $16 to register, about a third of the SAT fee. So it’s a very affordable way to warm up for the SAT itself.

With that said, there are cases where the PSAT may be an unnecessary extra step that you can and should skip.

If you aren’t interested in applying for the Merit Scholarship, the PSAT will be a lot less important to you, and maybe not worth your time. (Although I always encourage people to consider the Merit Scholarship– just being a runner-up can impress many admissions offices.) If you’ve just realized you are interested in the Merit Scholarship, but your junior year of high school has ended, you can also skip the PSAT.

And of course, skipping the PSAT is a good move if you decide it simply isn’t the right type of SAT warmup for you. While there are students that do benefit from taking the PSAT as a practice run for the SAT in their first or second year of high school, the real SAT can also be a truly authentic form of early practice, with a retake for admissions purposes during junior or senior year.

You don’t have to take the PSAT, but I still strongly recommend it. It’s a low-cost way to practice for the SAT and possibly apply for a National Merit Scholarship. Still, your mileage may vary. Many students skip the PSAT and go on to have top SAT scores and wonderful academic careers.

How has the PSAT changed?

If you know someone who took the PSAT before March 2016, you took a very different test than the current SAT. That test was vocabulary heavy, including the likes of lugubrious , punctilious , and meretricious . Basically words nobody outside of a literary circle would know, let alone have the audacity to utter. The math questions were often more like logic puzzles, carefully engineered so that they would have devious trap answers. The reading passages had lots of big words, abstract ideas, and answer choices so devious they made the math questions blush.

In other words, the test has become a lot friendlier and less likely to induce a full-blown panic attack. Did I mention that the old test actually had a guessing penalty? The reading questions are relatively straightforward, though the passages are longer and (in some cases) denser. Math questions better reflect the fundamentals you likely learned in class. Whereas the trap answers on the old test were as ferocious as mountain lions, on the new PSAT they are, at worst, fussy housecats.

Can I take the PSAT if I’m not in the United States?

If you’re living outside of the United States, you may still be able to find a nearby school that offers the test. The school search on the College Board website can help you figure out where to go and who to contact. Many countries have several schools in different cities offer the exam.

Do it early, though: the College Board recommends making preparations at least four months in advance of the exam—that’s July (although there’s no harm in asking later if you didn’t know you could take the exam as an international student)!

Can I take the PSAT if I’m home-schooled?

Yes! Like international students, students who have been home schooled should identify a local school through the College Board school search. Similarly, the College Board recommends getting in touch with the school at least four months in advance—this way, the school can be sure to have materials, like a test booklet, ready for you.

I need special accommodations to take the test. How should I set those up?

If you have a disability that requires special accommodation, make sure you get approval from the College Board at least seven weeks before the test date. You should make sure that you talk to a guidance counselor or the person in charge of the test at your school, as well, around this date, to ensure that the requirements are met on test day.

I’m planning on taking the ACT. Does the ACT have a similar test like the PSAT?

It does, actually! It’s called the PreACT—check out our complete guide to the PreACT to learn more.

After all of the PSAT tips in this post, here’s one final tip: because the PSAT is not offered as often as the SAT, it’s important to create your study plan with the October test date in mind. Unlike the SAT, the PSAT tends to be an exam that students take just once.

Rachel is a Magoosh Content Creator. She writes and updates content on our High School and GRE Blogs to ensure students are equipped with the best information during their test prep journey. As a test-prep instructor for more than five years in there different countries, Rachel has helped students around the world prepare for various standardized tests, including the SAT, ACT, TOEFL, GRE, and GMAT, and she is one of the authors of our Magoosh ACT Prep Book . Rachel has a Bachelor of Arts in Comparative Literature from Brown University, an MA in Cinematography from the Université de Paris VII, and a Ph.D. in Film Studies from University College London. For over a decade, Rachel has honed her craft as a fiction and memoir writer and public speaker. Her novel, THE BALLERINAS , is forthcoming in December 2021 from St. Martin’s Press , while her memoir, GRADUATES IN WONDERLAND , co-written with Jessica Pan, was published in 2014 by Penguin Random House. Her work has appeared in over a dozen online and print publications, including Vanity Fair Hollywood. When she isn’t strategically stringing words together at Magoosh, you can find Rachel riding horses or with her nose in a book. Join her on Twitter , Instagram , or Facebook !

View all posts

More from Magoosh

4 responses to “PSAT Practice: How to Prepare and Why You Should”

Is there any coaching/test prep for 10th grade PSAT? Thanks , Subramanian

Hi Subramanian,

The PSAT tests exactly the same concepts as the SAT in the same way. It’s just shorter. So, any test prep or practice that you do for the SAT will also help you prepare for the PSAT! 🙂

I need tuition for PSAT

Hi Erum, students sign up for the PSAT through their school. You should contact your teachers and academic counselors for more information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, writing section on the psat: yay or nay.

Guys, is there a separate writing section on the PSAT? I've been practicing my essays, but I'm not sure if I even need to for this test. Can't seem to find a straight answer anywhere, help a junior out!

Hey there! It's great that you're practicing your essays, as strong writing skills are always beneficial. However, the PSAT does not have a separate, scored essay section. The test is divided into Evidence-Based Reading, Writing & Language, and Math sections. The Writing & Language section does test your ability to revise and edit texts for clarity, grammar, and punctuation, but it won't require you to write an essay from scratch. So, while your essay practice won't directly apply to the PSAT itself, it's still valuable practice for future standardized tests you might take, such as the SAT, which does have an optional Essay section. Keep honing those writing skills, and they'll come in handy for your college admissions essays down the line! For now, focus on getting comfortable with the multiple-choice questions you'll see on the Writing & Language section of the PSAT. You've got this!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

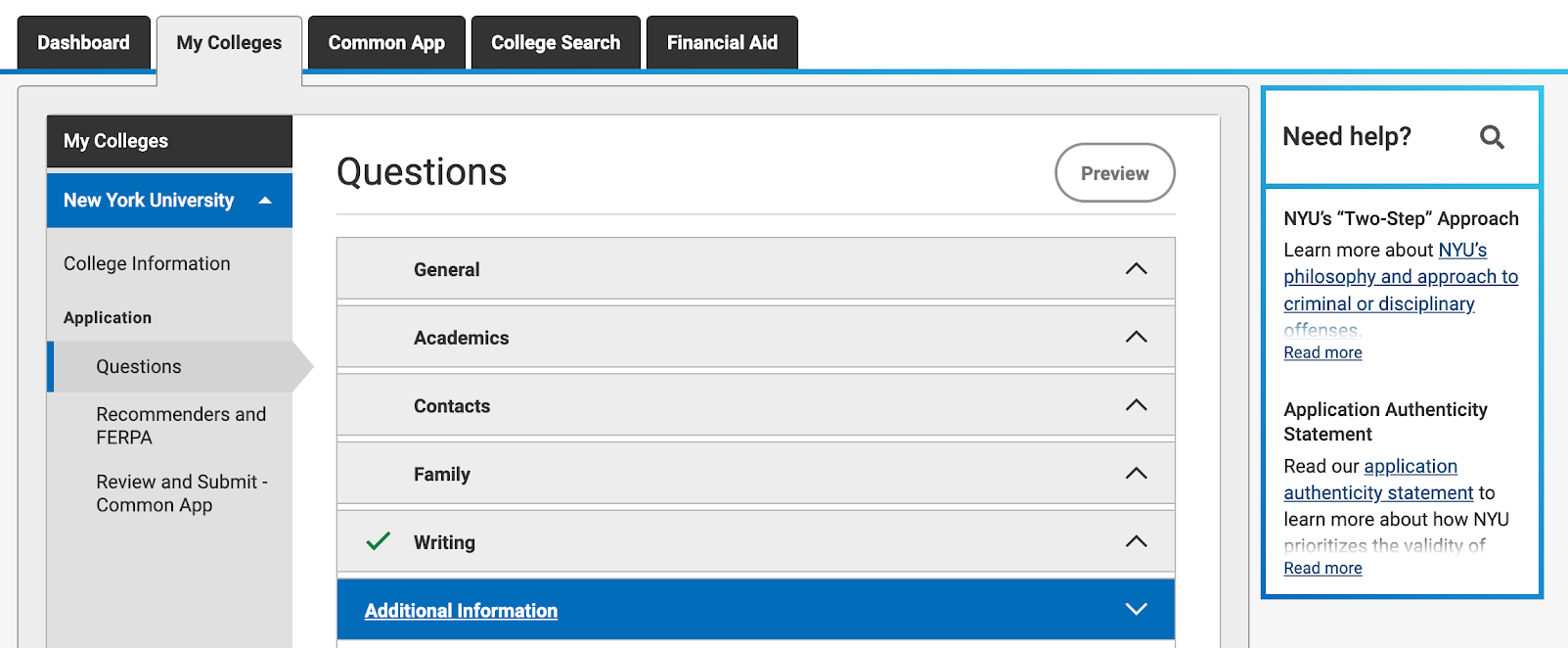

Test Optional and Optional Essay: What Optional Really Means

So far, 2020 has proven to be a year of big changes, and the college admissions process is no different. Some pieces of the application that used to be required are now optional, and what colleges mean by “optional” needs further explanation and clarification.

What “test optional” means

Test optional means just that: it is not mandatory for applicants to submit test scores to be considered for admission. In response to the testing disruptions caused by COVID-19, many colleges and universities have suspended their policy that applicants must submit SAT or ACT results as part of their application.

Eighteen colleges have gone test optional in the last four months. Some schools have waived their standardized test requirement only for applicants seeking to enroll in fall 2021; others waived the requirement for three years (to be followed by an assessment of what they’ll do about tests going forward); and still others made the change permanent. Look at the list of colleges you plan to apply to, and make sure you know which policy each of your schools has adopted. If any of your colleges are test optional, consider the average scores for admitted students (if that college publishes them). If you feel your scores will help your application, send them. If you feel they will hurt your application, don’t send them.

The list of test optional schools can be found at fairtest.org . If you are a client of International College Counselors, your college advisor will help you navigate the policies.

Why take the ACT, SAT, and/or SAT Subject Tests

Be aware that schools with a “test optional” policy are still considering submitted test scores. This means that students who submit strong test scores may have an advantage over students who do not submit them, as reported scores will be factored into the decision-making process. Only if a school explicitly states they have a “test blind” admissions policy (meaning they will not consider test scores even if the applicant submits them), will scores not be factored into the admission decision. There are only a few schools that have “test blind” SAT/ACT admission policies (for example, Northern Illinois University, Loyola of New Orleans, and the University of New Hampshire).

Speaking of “test blind,” several schools, including Cornell, Caltech, MIT, and Harvey Mudd have moved to “test blind” for SAT Subject Tests , meaning they will no longer consider these scores even if an applicant submits them . There are still, however, a number of colleges that still “recommend” or “consider” SAT Subject Test scores (for example, Carnegie Mellon, University of Virginia, Rice, and Northwestern).

In addition, athletes who plan to play at the college level many need an ACT or SAT score to be eligible to compete.

How standardized tests help colleges

Many college admission offices, and many college administrations, though not all, support the use of the SAT or ACT in assessing a student’s college readiness. They claim that the scores are objective, are useful in negating grade inflation, and help identify promising applicants whose high school transcripts do not reflect their potential. They will also tell you that test scores can help a college evaluate an applicant’s academic performance in relation to the rest of the applicant pool, which is applying from thousands of different high schools across the country and around the world.

Scholarships, SAT, and ACT scores

Another reason to take the SAT or ACT is that many colleges offer scholarships to students who have earned a minimum GPA as well as a high SAT/ACT score. These scholarships may range from a few thousand dollars to a “full ride.” Many states also award scholarships to students who meet certain minimum GPA and SAT/ACT requirements. Students who do not take the SAT or ACT may not be eligible for these scholarships.

“Optional” essays which aren’t optional

On the college application, students may see that an essay is “optional.” At International College Counselors, we believe that optional essays are not optional and that students should complete all “optional” essays. Optional essays may help schools differentiate between students with similar qualifications. Writing the optional essay demonstrates that a student has initiative and is serious about attending. In addition, a strong “optional” essay gives the admissions officer more information to consider in their decision.

However, there is at least one exception to the “rule” that optional essays aren’t really optional. On their application last year, Duke included the following optional prompt: Duke’s commitment to diversity and inclusion includes sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. If you would like to share with us more about how you identify as LGBTQIA+, and have not done so elsewhere in the application, we invite you to do so here . This prompt should only be answered by students who feel that their application would otherwise be missing an integral component of their identity and who feel comfortable sharing this information with the admission committee.

Independent college advisors are a good option

At International College Counselors, we believe in helping students develop holistically. A holistic approach allows a student to demonstrate and spotlight their strengths and best leverage their unique talents and situation. Enable us to expand your student’s options.

Looking to connect with a top SAT or ACT tutor, a college admissions essay expert, or a college advisor who can help your student develop holistically? Contact us. International College Counselors strives to be a strong resource and partner for your family. Even in these unprecedented times, we can enable your student to reach their fullest potential in the college admissions journey. We’re here to help.

For help with any or all parts of the college admissions process or decision making, visit http://www.internationalcollegecounselors.com or call 954-414-9986.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Our Services

College Admissions Counseling

UK University Admissions Counseling

EU University Admissions Counseling

College Athletic Recruitment

Crimson Rise: College Prep for Middle Schoolers

Indigo Research: Online Research Opportunities for High Schoolers

Delta Institute: Work Experience Programs For High Schoolers

Graduate School Admissions Counseling

Private Boarding & Day School Admissions

Essay Review

Financial Aid & Merit Scholarships

Our Leaders and Counselors

Our Student Success

Crimson Student Alumni

Our Results

Our Reviews

Our Scholarships

Careers at Crimson

University Profiles

US College Admissions Calculator

GPA Calculator

Practice Standardized Tests

SAT Practice Test

ACT Practice Tests

Personal Essay Topic Generator

eBooks and Infographics

Crimson YouTube Channel

Summer Apply - Best Summer Programs

Top of the Class Podcast

ACCEPTED! Book by Jamie Beaton

Crimson Global Academy

+1 (646) 419-3178

Go back to all articles

SAT vs. PSAT: Key Differences & Essential Insights

/f/64062/1920x800/11d805183b/psat.jpg)

What Is the SAT?

What is the psat, sat vs. psat: key differences, crimson insights: why take the psat.

Deciding Whether to Take the PSAT

Are you a parent or an academically motivated high school student trying to navigate the world of standardized testing? Our blog post, "SAT vs. PSAT: Key Differences & Essential Insights," is here to help. This comprehensive guide breaks down the key differences between the SAT vs. PSAT, explaining their distinct purposes, difficulty levels, and testing formats. You'll get a helpful overview of each test, the SAT and PSAT, and you’ll learn why taking the PSAT, can be a strategic move, offering practice for the SAT, scholarship opportunities, and valuable feedback on academic skills. Whether you're aiming for top colleges or simply want to reduce test anxiety, this post provides essential information to help you make informed decisions about your testing strategy.

As admissions strategists, we know that students and guardians understand how crucial standardized tests can be in the college admissions process.

And, while many families are largely familiar with the SAT, the role of the PSAT, on the other hand, is often a source of some doubt and confusion , especially because both the PSAT and SAT are standardized tests for high school students and published and scored by the same entity, the College Board.

By the end of this post, you'll have a clear understanding of each test and their differences , and you'll learn exactly how the PSAT dovetails with preparation for the SAT.

You’ll also learn the reasons why the PSAT offers some meaningful benefits for high-school-age students, even though not used for college admission, and when and how students can take the PSAT.

The SAT is a widely used, respected, and accepted academic skills assessment. It complements other academic indicators, such as GPA and course rigor, in holistic admissions processes at many US colleges and universities, especially those that are more selective and competitive.

What some people may not realize is that the SAT is part of a larger suite of assessments, all published by the College Board , that includes various versions of the PSAT (Pre-SAT) alongside the SAT.

A rival standardized test, the ACT, is also widely used and accepted for college admissions, but the SAT tends to be used by more students. Both the SAT and ACT have made recent shifts from paper and pencil formats to digital, online test platforms . Today the SAT is officially a digital test , while most students who take the ACT can choose the format they prefer, online or pen and paper.

Unlike the online ACT, the digital version of the SAT resulted in a test that is a bit shorter and introduces adaptive features — adapting the challenge level of some test items in real time, based on an automated assessment of a student’s initial responses and proficiency levels.

The digital SAT continues to be divided into three main sections, as with the old paper version:

- Evidence-Based Reading and Writing

- Optional Essay

Excluding the optional Essay test, students receive two summative scores each time they take the SAT, a Reading/Writing Score (50%) and a Math Score (50%). The maximum in each of these categories is 800 points, making the maximum overall score 1600.

On a national scale, the equivalent of a “good” SAT score might be deemed a score that falls in the 75th percentile — not a score of 75% or higher, but a score high enough to earn a ranking in the top 25% of all scores across a national pool of SAT test takers.

When it comes to getting a “good” SAT score in the context of applying to Ivy League schools or other top US colleges and universities, a test taker will typically need to rank in the very highest percentiles, among the top 8% or better nationally.

To learn more about SAT scores, percentiles, and college admissions, check out What Is a Good SAT Score for Top Universities in 2024?

When to Take the SAT

Most students take the SAT in the spring of their junior year or the fall of their senior year. It's essential to prepare thoroughly, as a strong SAT score can significantly enhance your college application. This means retaking the SAT is a common practice, helping students score in a higher range over time.

To learn more about when to take the SAT, about strategies for retakes, and how to boost scores, check out How Many Times Can You Take the SAT?

How to Know if the SAT Is Required for Admissions

While standardized test scores have typically been a crucial component of a student’s college application, especially for top-ranking schools , many colleges and universities have abandoned that requirement or, in the wake of the pandemic, have adopted temporary or indefinite test-optional admissions policies.

While a SAT score is not required for test-optional schools , many of them recommend including test scores when applying for admission. As strategists, we also typically recommend including test scores due to the competitive nature of admissions at most of the best colleges and universities.

Keep in mind that many top-ranked schools are requiring test scores , including several Ivy League schools currently reinstating test requirements , shifting away from provisional test-optional policies.

While you may still see some references to the PSAT standing for the Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test, the College Board, which publishes and scores the test, points out that references to aptitude testing have been removed from both the SAT and PSAT acronyms.

“Today, ‘SAT’ has no meaning as an acronym. The SAT acronym originally stood for ‘Scholastic Aptitude Test,’ but as the test evolved, the acronym’s meaning was dropped… ‘PSAT’ stands for ‘Preliminary SAT,’ but it has no meaning on its own, and you won’t see it as a stand-alone term.”

- collegeboard.org.

Compared to the SAT, more families have questions about the PSAT, no doubt because PSAT scores are never required when applying to college, making the PSAT less relevant to the college admissions process .

The PSAT/NMSQT (Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test) serves as both a practice test for the SAT and a qualifying test for the National Merit Scholarship Program.

As a practice test for the SAT, the PSAT is slightly shorter and less challenging than its SAT cousin, making it an excellent low-stakes way for a younger student to get a feel for the SAT format.

Aligned with its SAT practice function, the PSAT comes in multiple versions, such as the PSAT 8/9 , and the PSAT 10 — intended for students who want to start practicing in lower grade levels — alongside the PSAT/NMSQT (Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test)

Like the SAT, the PSAT is also now officially offered in a digital format that’s shorter than the older version of the PSAT, has more time per question, and comes with a built-in calculator.

The PSAT also stands out for its exclusive ties to the National Merit Scholarship program . This program offers chances for academic honors and distinction, with top winners eligible to earn cash scholarship awards as well.

To compete in this competition students need to meet the following criteria:

- Take the PSAT/NMSQT

- Be enrolled in a US high school or be a qualifying US citizen enrolled at a high school abroad

- Be on a satisfactory academic trajectory in high school and bound for college

When to Take the PSAT and How

Students typically take the PSAT in their sophomore and junior years. Junior year scores are the ones considered for National Merit Scholarships.

The College Board also offers the PSAT 8/9, adapted to younger test takers, in grades 8 and 9, described by the College Board as designed “to establish a starting point in terms of college and career readiness as students transition to high school.”

The regular PSAT is administered to high school juniors only once per year, typically in the fall.

The PSAT 10 is typically offered in the spring, coinciding with the second half of a student’s sophomore year.

The PSAT 8/9 may be offered in the spring, fall, or both.

Registering for the PSAT

The PSAT is administered only by local schools or school districts working in conjunction with the College Board.

You should check with your school principal or guidance counselor, no later than early September, for more information about test registration and dates.

No test offered at your school? You may want to inquire at other schools in your area and see if you can test at a different school site that does facilitate PSAT test taking.

The SAT and PSAT have a lot in common, but there are some key differences outlined below.

After highlighting the differences between the two tests, we'll explore why and when it can make sense to study for and take the PSAT, on a runway to taking the SAT for college admissions.

| SAT | PSAT | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Used for college admissions May be used to qualify for some merit-based scholarships | Provides practice for the SAT Serves as a way to qualify for National Merit Scholarship or other merit-based programs |

| Length, Content, and Difficulty | About 15 minutes longer and slightly more challenging than PSAT Two main sections are Math and Evidence-based Reading/Writing + an optional Essay | Content and difficulty are similar to SAT but adapted to students in 10th grade Two main sections are Math and Evidence-based Reading/Writing No essay |

| Scoring | Scores range from 400 to 1600 The Reading/Writing component and Math component are both scored on a scale from 200 to 800, giving the SAT an overall score scale from 400 to 1600 | Scores range from 320 to 1520 While PSAT scores correspond directly to SAT scores, the PSAT overall is slightly less challenging than the SAT, so the minimum and maximum scores are 320 and 1520. |

| Test Availability, Registration, and Scheduling | SAT is typically offered seven times each school year Students register using the centralized College Board online registration platform | The PSAT is offered one time each school year, in October The PSAT 10 is typically offered to sophomores in the spring The PSAT 8/9 is typically offered in the fall and/or spring, to 8th and 9th graders |

Comparing Test Structures: SAT vs. PSAT

In terms of academic content and structure, the SAT and PSAT are closely aligned, as shown in the table below.

Comparison of SAT vs. PSAT Structure

| Section | SAT | PSAT |

|---|---|---|

| Reading | 65 minutes, 52 questions | 60 minutes, 47 questions |

| Writing | 35 minutes, 44 questions | 35 minutes, 44 questions |

| Math — No Calculator | 25 minutes, 20 questions | 25 minutes, 17 questions |

| Math — Calculator | 55 minutes, 38 questions | 45 minutes, 31 questions |

| Total | 3 hours, 154 questions | 2 hours 45 minutes, 139 questions |

1. Test Practice

Taking the PSAT allows you to become familiar with the test format and question types, which can help reduce test anxiety and improve your performance on the SAT.

If you haven’t had many experiences taking timed tests in group settings, then taking the PSAT is a great low-stakes opportunity to get some practice. As of 2024 the PSAT is only offered in a digital format, further aligning it with the format of the regular SAT test whose score you’ll use when applying to college.

2. Scholarships

High-scoring individuals can open doors to recognition and scholarship opportunities.

High scores on the PSAT can qualify you for the National Merit Scholarship Program and other scholarship opportunities, which can be a significant financial boost for college.

By scoring well enough to qualify as a semifinalist at your state level, you can add that distinction to your college application resume and vye for a spot as a National Merit Scholarship Finalist, with opportunities to earn a scholarship of up to $2,500.

Students who earn a semifinalist spot do need to satisfy other important requirements in order to become a scholarship finalist, however, so be sure to stay engaged up to the end!

“Only Finalists will be considered for the National Merit® Scholarships. Approximately half of the Finalists will be Merit Scholarship® winners. Winners are chosen on the basis of their abilities, skills, and accomplishments—without regard to gender, race, ethnic origin, or religious preference. Scholarship recipients are the candidates judged to have the greatest potential for success in rigorous college studies and beyond.”

- national merit scholarship.org.

3. Academic Preparation

Get early feedback on academic skills critical for SAT tests and college admissions.

The PSAT provides detailed score reports. These reports provide valuable feedback on your strengths and areas for improvement for the kinds of academic concepts and skills assessed on the SAT.

Because the PSAT is “low risk” — in the sense that your scores are not sent to colleges, only to your high school, district, and state — it’s a way to get feedback and assess your SAT readiness without worrying about any downside if you get a score in the lower ranges.

If you wind up seeking assistance from a personalized SAT tutor down the road, your PSAT score report may equip your SAT tutor to make a better support plan .

4. Vocational Exploration

Establish a foundation for long-term college and career planning.

By taking the PSAT, you gain access to college planning resources and tools that can help you make informed decisions about your future.

This kind of exploration can help students identify high school electives and extracurricular activities aligned with a larger vocational interest and passion.

Your score feedback may also help jump start introspection and ideation for long-term career goals.

Who Should Take the PSAT?

High-achieving students.