Title VII and Caste Discrimination

- Guha Krishnamurthi

- Charanya Krishnaswami

- See full issue

Introduction

In the summer of 2020, a report of workplace discrimination roiled Silicon Valley and the tech world. 1 An employee at Cisco Systems, Inc. (Cisco), known only as John Doe, alleged he had suffered an insidious pattern of discrimination — paid less, cut out of opportunities, marginalized by coworkers — based on his caste. 2 Consequently, the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH) brought suit against Cisco, alleging that the employee’s managers and (thus) Cisco had engaged in unlawful employment discrimination. 3 Doe is a Dalit Indian. 4 Dalits were once referred to as “untouchables” under the South Asian caste system; they suffered and continue to suffer unthinkable caste-based oppression in India and elsewhere in the Subcontinent. 5 Doe claims that two managers, also from India but belonging to a dominant caste, 6 denigrated him based on his Dalit background, denied him promotions, and retaliated against him when he complained of the discriminatory treatment. 7 Thereafter, a group of thirty women engineers who identify as Dalit and who work for tech companies like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Cisco shared an anonymous statement with the Washington Post explaining the caste bias they have faced in the workplace and calling for the tech industry to be better. 8

While Doe’s and the thirty women engineers’ allegations of caste discrimination raise novel questions about the application of civil rights statutes to workplace discrimination on the basis of caste, these allegations echo a tale as old as time: the millennia-old structure of caste discrimination and the systemic oppression of Dalits, which has been described as a system of “apartheid,” 9 the “[c]onstancy of the [b]ottom [r]ung,” 10 and reduction to the “lowest of the low,” 11 a fixed position that followed Doe and these thirty women engineers halfway around the world. DFEH’s case based on Doe’s allegations is still at the complaint stage, with a long road of discovery surely ahead. Other claims of caste discrimination, including by the thirty women engineers, have not yet been brought to court. Thus, for all these cases, a preliminary legal question beckons: Is a claim of caste discrimination cognizable under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964? 12 We argue that the answer is yes.

This Essay continues in two Parts. In Part I, we explain the basic contours and characteristics of the South Asian caste system and detail the reach and impact of caste in the United States. In Part II, we explain how caste discrimination is, as a legal matter, cognizable under Title VII as discrimination based on “race,” “religion,” or “national origin,” following the Supreme Court’s teaching in Bostock v. Clayton County , 13 in which the Court found that sexual orientation discrimination is a type of sex discrimination. 14 We briefly conclude, contending that, despite the coverage of caste discrimination under federal law, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or Congress should provide further clear guidance — and in doing so consider other kinds of discrimination throughout the world that should be explicitly prohibited in the United States. While addressing claims of caste discrimination through Title VII enforcement is just one of many steps that must be taken to eradicate caste-based discrimination, naming caste as a prohibited basis on which to discriminate has the added value of increasing public consciousness about a phenomenon that, at least in U.S. workplaces, remains invisible to many.

I. Caste Discrimination and Its Reach

A. brief description of the south asian caste system.

Caste is a structure of social stratification that is characterized by hereditary transmission of a set of practices, often including occupation, ritual practice, and social interaction. 15 There are various social systems around the world that have been described as “caste” systems. 16 Here, we will use “caste” to refer to the South Asian caste system that operates both in South Asia and in the diaspora. 17 As we will see, the South Asian caste system is a hierarchical system that involves discrimination and perpetuates oppression.

The South Asian caste system covers around 1.8 billion people, and it is instantiated in different ways through different ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups and geographies. 18 As a result, it can be difficult to say anything categorical about the caste system. Thus, our description identifies its broad contours and characteristics.

The caste system is rooted in the indigenous traditions, practices, and religions of South Asia. 19 We can generally refer to those traditions, practices, and religions as “Hinduism.” The term Hinduism, as we use it, is an umbrella term for a diversity of traditions, practices, and religions that may share no common thread except for geographical provenance. So defined, the term Hinduism is capacious. We separately identify Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. As a matter of convention, Christianity and Islam are not generally considered or labeled indigenous religions of the Subcontinent, but the forms of those religions in the Subcontinent have distinctive features. 20

The caste system is an amalgamation of at least two different systems: varna and jati . 21 Varna is a four-part stratification made up of brahmana , kshatriya , vaishya , and shudra classes. 22 These classes have been characterized as the priestly class, the ruler-warrior class, the merchant class, and the laborer class, respectively. 23 There is implicitly another varna — those excluded from this four-part hierarchy. 24 They are sometimes described as belonging to the panchama varna (literally, the “fifth varna ”). 25 The panchama varna is treated as synonymous with the term “untouchable” 26 — now called “Dalit.” 27

Alongside the varna system is the jati system. Jati refers to more specific groupings, and in the actual practice of the caste system, jati is much more significant. 28 There are thousands of jati -s, and jati identity incorporates, among other things, traditional occupation, linguistic identity, geographical identity, and religious identity. 29 Similar to varna , there is a large underclass in the jati system made up of many jati -s. Those include jati -s based on certain traditional occupations viewed as “unclean,” like agricultural workers, scavengers, cobblers, and street sweepers. 30 They also include certain tribal identities, called “Adivasis.” 31 The relationship between varna and jati is complex. At various junctures, people have attempted to place jati -s within a varna , to create a unified system of sorts. This attempted fusion inevitably continues the “tradition of dispute over whether these two hierarchies coincide, and which is the more fundamental.” 32

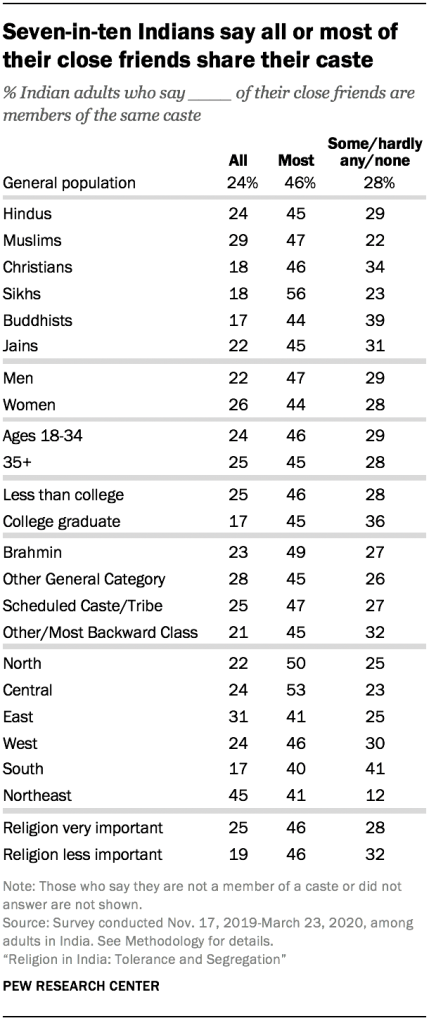

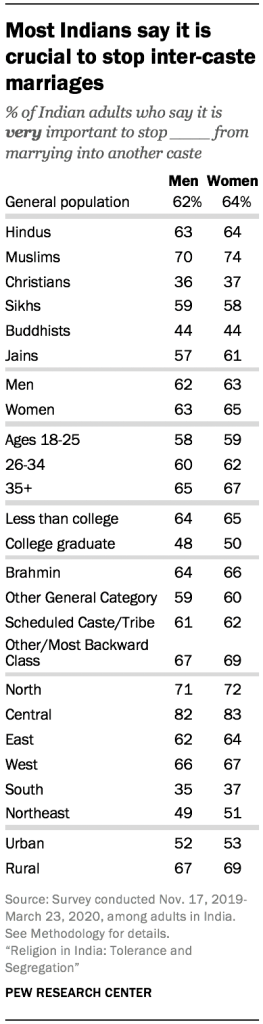

The foundations of the caste system are nebulous at best. The system may have had some grounding in primitive racial, color, ethnic, or linguistic distinctions, but that is unclear. 33 Nevertheless, the resulting caste system can be characterized with at least the following core traits: (1) hereditary transmission and endogamy; (2) strong relationships with religious and social practice and interaction; (3) relationships with concepts of “purity” and “pollution”; and (4) hierarchical ordering, including through perceived superiority of dominant castes over oppressed castes, hierarchy of occupation, and discrimination and stigmatization of oppressed castes. 34

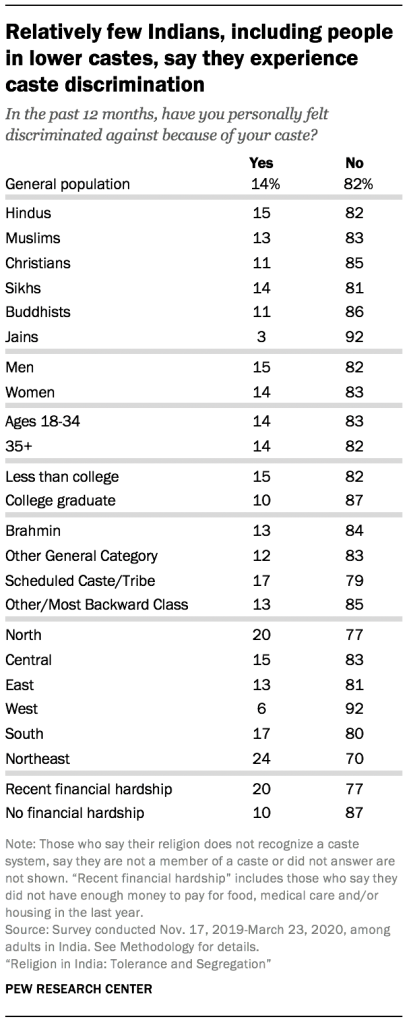

As observed, the caste system is rooted in Hinduism. 35 And it continues to live in modern Hindu practice. 36 Of course, many Hindus are committed to the eradication of caste and the belief that true Hindu belief eschews (and has always eschewed) the evils of caste. 37 But modern Hindu practice continues to recognize and entrench caste in religious and social practice and interaction, and people suffer oppression and discrimination on the basis of caste. 38 The tentacles of caste oppression extend beyond modern Hindu practice as well: in South Asia, caste distinction and oppression manifests in Christian, Muslim, Sikh, and Jain communities, among others. 39 As a detailed report on caste by the Dalit-led research and advocacy group Equality Labs has observed, “[t]his entire [caste discrimination] system is enforced by violence and maintained by one of the oldest, most persistent cultures of impunity throughout South Asia, most notably in India, where despite the contemporary illegality of the system, it has persisted and thrived for 2,500 years.” 40 There is no doubt that Hinduism provided the foundation for caste discrimination and oppression and that modern Hindu practice continues to perpetuate it. But the insidiousness of caste discrimination is such that it sprouts and thrives even when divorced from its doctrinal home of Hinduism, and even when there is claimed caste eradication.

Regarding caste hierarchy, the ordering is complex, incomplete, and controversial. There is no lineal ordering, and any putative ordering is not definitive. Brahmana are generally described as occupying the top of the proverbial pyramid, though kshatriya and vaishya communities often claim divine lineage, and do not necessarily recognize any so-called brahmana supremacy. 41 These three varna are usually understood to form the core of the so-called “upper,” or dominant, castes. 42 Those of the four named varna -s have historically been ranked as “superior” to those of the fifth ( panchama ) varna — the “untouchables” or Dalits. 43 Similarly clear is that those categorized as brahmana , kshatriya , and vaishya have historically subjugated the shudra varna . 44

Of course, these hierarchical comparisons are entirely bigoted and without merit. 45 As a result of them, Dalits, Shudras, and others have experienced and continue to experience horrific oppression at the hands of dominant castes — what Equality Labs has described as a “system of Caste apartheid,” with oppressed castes “having to live in segregated ghettoes, being banned from places of worship, and being denied access to schools and other public amenities including water and roads.” 46

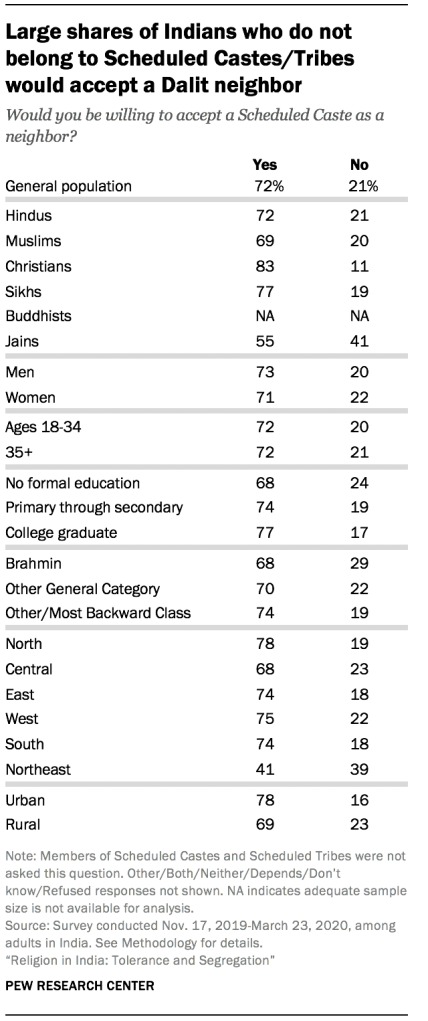

Oppressed-caste status impacts everything in one’s life. 47 It can impact one’s access to religious and social institutions — for example, Dalits and Shudras may be barred from entering temples, mosques, gurdwaras, and churches. 48 It may mean that they cannot eat in certain restaurants or shop at certain stores. It may mean that they are not allowed to marry people of different caste lineage 49 — and will be killed if they try. 50 It may mean that they cannot eat in certain people’s houses. 51 It may mean that they are not even allowed to cremate or bury their dead. 52 Moreover, oppressed-caste individuals have often been subjected to hate-based violence, with no genuine access to jus-tice. 53 And, as a political matter, individuals of oppressed castes have often been denied meaningful representation. 54

Consequently, South Asian governments have attempted to address these problems, at least nominally, through prohibitions on discrimination 55 and through “reservation” — systems that seek to uplift these oppressed communities through uses of quotas in education and employment. 56 These actions have faced continued opposition from members of dominant castes. 57 And, as a result, Dalits, Adivasis, and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) who obtain reservation are often discrimi-nated against as potential beneficiaries of reservation, even though res-ervation was meant to rectify and address millennia of caste-based oppression.

Finally, and relevantly, the South Asian caste system has traveled beyond the borders of the Subcontinent. The South Asian diaspora observes caste identity, and there is consequent caste discrimination. 58 As Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, a leader of the Dalit liberation movement and author of the Indian Constitution, stated, caste discrimination and oppression “is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief, for ‘as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or have any social intercourse with outsiders; and if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem.’” 59

B. The Impact of Caste in the United States

The immigration of South Asians to the United States has come in waves, each of which has changed the caste dynamics of the population. While today the population is viewed as a monolith, from the earliest days of South Asian migration, dominant-caste members of the diaspora sought to differentiate themselves from the oppressed others. 60 Given dominant-caste members’ fears that crossing an ocean would cause them to lose their caste status, the earliest migrants to the United States were those who had nothing to lose: predominantly oppressed-caste and non-Hindu people. 61

At the turn of the twentieth century, xenophobic backlash against East and South Asian immigrants led to new laws forbidding nonwhite immigrants from accessing citizenship, with heart-wrenching consequences for South Asian immigrants who had forged lives and families in the country. 62 In 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind, a dominant-caste immigrant born in Amritsar, Punjab, “sought to make common cause with his upper-caste counterparts in America,” 63 effectively arguing his ethnic background and caste laid a claim to whiteness in his adopted coun-try — claims, as Equality Labs notes, the caste-oppressed could never make. 64

Today, there are nearly 5.4 million South Asians in the United States. 65 From 2010 to 2017, the South Asian population grew by a “staggering” forty percent. 66 The first wave of modern migration from the Subcontinent took place in the wake of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, 67 which removed discriminatory national origin-based quotas, and which established the modern immigration system based on work and family ties. 68 Equality Labs notes the majority of South Asian immigrants who came to the United States after the 1965 reform were “professionals and students[,] . . . largely ‘upper’ Caste, upper class, the most educated, and c[oming] from the newly independent Indian cities.” 69 Oppressed-caste people, by contrast, having had at that point just limited access to educational and professional opportunities, came in smaller numbers. 70 The Immigration Act of 1990, 71 which liberalized employment-based migration, further opened up pathways for South Asian immigration to the United States. 72 This wave, according to Equality Labs, included a growing number of immigrants from historically oppressed castes who, through resistance movements and reforms in access to education and other opportunities, were increasingly able to harness sufficient mobility to migrate. 73 Even still, according to a 2003 study from the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania, only 1.5% of Indian immigrants were members of Dalit or other oppressed castes, while more than 90% were from high or dominant castes. 74

Yet, contrary to the fears of the earliest South Asian immigrants to the United States, the fact of one’s caste is not shed by the crossing of an ocean. As South Asian immigrants have integrated into the United States in increasing numbers, caste discrimination among the diaspora’s members threatens to entrench itself as well. This caste discrimination is complicated and perhaps obscured by a second racial caste system in the United States: one which situates South Asians generally as an in-between “middle caste,” relatively privileged and sometimes conferred “model minority” status, yet still systematically excluded from the highest echelons of power and discriminated against on the basis of race and national origin. 75

Given how entrenched and ubiquitous caste oppression still is across South Asia, and how programmed and hereditary discriminatory attitudes can be, it is easy to imagine how a subtler, more insidious form of caste discrimination has replicated here. As the South Asian community in the United States has grown, so have, for example, identity groups organized around linguistic and caste identities, 76 informally entrenching caste divisions among South Asians in the United States. The only study of which we are aware concerning caste identity and discrimination in the United States, conducted by Equality Labs, found that, of 1,200 people surveyed, over half of Dalits in the United States reported experiencing caste-based derogatory remarks or jokes against them, and over a quarter reported experiencing physical assault based on their caste. 77

Of particular relevance to this paper, an astonishing two-thirds of Dalit respondents to the survey reported experiencing some form of discrimination in the workplace. 78 The workplace is one of the primary areas where caste discrimination manifests — perhaps because caste itself is historically predicated in part on one’s work, the notion that one’s birth consigns one to a certain occupation, and concomitantly a certain status and fate.

In the U.S. tech sector, which has a large South Asian workforce, 79 complaints of caste discrimination have been particularly rampant. Earlier this month, a group of thirty women engineers who identify as Dalit and who work for tech companies like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Cisco issued a public statement to the Washington Post stating they had faced caste bias in the U.S. tech sector. 80 Other Dalit employees have described their fears of being “outed” in the workplace, as well as subtle attempts to discern their caste based on so-called “caste locator[s],” such as the neighborhoods where they grew up, whether they eat meat, or what religion they practice. 81 The risks of caste discrimination against oppressed-caste employees are exacerbated in professions with high numbers of South Asians, where programmed attitudes about caste superiority and inferiority can easily take hold. With this subtler, more insidious discrimination taking root, we must determine what recourse exists in the law to combat it.

II. Title VII’s Coverage of Caste

To answer the legal question, we first look at the statute. Title VII prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. 82 Thus, for caste discrimination to be cognizable under Title VII, it must be cognizable as discrimination based on at least one of these grounds. The challenge is to determine which if any of these grounds encompasses caste discrimination.

Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County , our determination whether caste discrimination is cognizable under any of these grounds is governed by the text of the statute. 83 Title VII makes it “unlawful . . . for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” 84

The first question in determining coverage under Title VII is whether caste is in fact simply reducible to one of these categories. If not, the next question is whether caste discrimination satisfies the but-for causation test with respect to one of these categories. 85 As the Bostock Court explains:

[But-for] causation is established whenever a particular outcome would not have happened “but for” the purported cause. In other words, a but-for test directs us to change one thing at a time and see if the outcome changes. If it does, we have found a but-for cause. This can be a sweeping standard. Often, events have multiple but-for causes. So, for example, if a car accident occurred both because the defend-ant ran a red light and because the plaintiff failed to signal his turn at the intersection, we might call each a but-for cause of the collision. When it comes to Title VII, the adoption of the traditional but-for causation standard means a defendant cannot avoid liability just by citing some other factor that contributed to the challenged employment decision. So long as the plaintiff’s sex was one but-for cause of that decision, that is enough to trigger the law. 86

Finally, we can ask whether caste is “conceptually” dependent on one of these categories. 87 For all these questions, we may consider the original expected applications of the statute, but we are not limited to those expected applications. 88 Rather, we are led by the fair and reasonable meaning of the plain text, even if that goes beyond the expected applications. 89

As a preliminary determination, we can remove “sex” from the picture. Whatever caste discrimination is, it is self-evidently not on the basis of sex. At a first level, caste discrimination is not simply reducible to sex. Further, caste discrimination can be levied upon actors regardless of their sex, and without any appeal to their sex. Consequently, it meets neither the but-for causation test nor the conceptual dependence test. Of course, a person may experience discrimination based on caste and sex — for example, a Dalit woman may experience harassment based on both features of their identity. That raises questions of mixed motivation, addressed below. 90 But discrimination on the basis of caste alone does not necessarily implicate questions of sex.

That leaves national origin, race, color, and religion for our further investigation. We consider each in turn.

A. National Origin

We first contend that there is a plausible argument that caste discrimination constitutes discrimination on the basis of national origin.

Importantly, discrimination based on being South Asian is cognizable as discrimination based on “national origin.” 91 This may at first glance seem like an odd conclusion, since South Asia is not itself a nation. On this point, the EEOC explains: “National origin discrimination involves treating people (applicants or employees) unfavorably because they are from a particular country or part of the world, because of ethnicity or accent, or because they appear to be of a certain ethnic background (even if they are not).” 92 On this account, discrimination based on South Asian identity is clearly national-origin discrimination.

That said, straightforwardly, caste identity is not simply reducible to being South Asian. It is a further qualification of one’s South Asian identity.

In addition, the but-for test can be used to argue that caste discrimination is a form of national-origin discrimination, because it would not occur “but for” one’s national origin. Specifically, but for the employee having an ancestor who had a particular caste identity defined and dictated by South Asian culture and practice, the employee would not have been discriminated against. More simply, but for the employee having a particular South Asian heritage (that is, their involuntary membership in a South Asian caste hierarchy), the employee would not have been discriminated against. So that is national-origin discrimination.

And on the conceptual test: one cannot understand the employee’s caste identity without appeal to certain features of South Asian culture — thus, caste identity is conceptually dependent on South Asian identity and is therefore national-origin discrimination.

What exactly “race” is, and how “races” are properly defined, is an almost impenetrably difficult question. 93 There are compelling accounts of the caste system as, at its genesis, based on some variety of racial categorization, even if primitive. 94 And there are other accounts that claim that race is orthogonal to caste. 95 Resolving the question of whether caste is in fact reducible to or based on race would prove controversial, and so finding caste discrimination is racial discrimination because of caste’s relationship to race is an equally controversial proposition. Consequently, here, we do not pursue that type of argument.

There is however another sense in which caste may be simply reducible to race. If “race” means something like a group distinguished by ancestry, 96 then caste will select a particular “race,” because caste is a hereditary system that relates to ancestry. 97 The EEOC has suggested such an understanding of “race”: “Title VII does not contain a definition of ‘race.’ Race discrimination includes discrimination on the basis of ancestry or physical or cultural characteristics associated with a certain race, such as skin color, hair texture or styles, or certain facial features.” 98

The Supreme Court’s decision in Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji 99 supports the contention that discrimination based on “race” would be interpreted to include discrimination on the basis of “ancestry.” There, a professor — who was a United States citizen born in Iraq — filed suit alleging that his denial of tenure was based on his Arabian heritage and thus constituted unlawful discrimination under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. 100 The district court dismissed the complaint, ruling that a claim under § 1981 could not be maintained for discrimination based on being of the “Arabian race.” 101 The Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed, holding that the complaint properly alleged discrimination based on race. In so doing, the court of appeals explained that § 1981 was not limited to present racial classifications. Instead, the statute evinced an intention to recognize “at the least, membership in a group that is ethnically and physiognomically distinctive.” 102

The Supreme Court affirmed the court of appeals’ decision and holding that discrimination based on “Arabian ancestry” is racial discrimination under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. 103 The Court stated that the court of appeals “was thus quite right in holding that § 1981, ‘at a minimum,’ reaches discrimination against an individual ‘because he or she is genetically part of an ethnically and physiognomically distinctive sub-grouping of homo sapiens .’” 104 The Court cautioned, however, that this was sufficient but not necessary, and that in this case Arab heritage was sufficient because the statute evinced that Congress intended to protect people from discrimination “because of their ancestry or ethnic characteristics.” 105 Indeed, the Court may have been eschewing a biological or genetic conception of race, in favor of an understanding predicated on social construction. To this point, the Court noted:

Many modern biologists and anthropologists, however, criticize racial classifications as arbitrary and of little use in understanding the variability of human beings. It is said that genetically homogeneous populations do not exist and traits are not discontinuous between populations; therefore, a population can only be described in terms of relative frequencies of various traits. Clear-cut categories do not exist. The particular traits which have generally been chosen to characterize races have been criticized as having little biological significance. It has been found that differences between individuals of the same race are often greater than the differences between the “average” individuals of different races. These observations and others have led some, but not all, scientists to conclude that racial classifications are for the most part sociopolitical, rather than biological, in nature. 106

Thus, it seems that the Court understood ancestry discrimination as a type of racial discrimination. 107 And under the Court’s understanding of “ancestry or ethnic characteristics,” even if formed primarily due to sociopolitical forces, caste would qualify as ancestry, and thus caste discrimination as ancestry discrimination and “race” discrimination. 108

Of course, the current Supreme Court may not accept this formulation of race as including “discrimination on the basis of ancestry” or an “ethnic[] and physiognomic[]” subgrouping. Indeed, it is plausible that the Court would interpret “race” to be rooted in racial classifications that were salient in the American experience at the time of the Act’s passage. 109 The new Court could disclaim its decision in Al-Khazraji . Or the Court might decide that, while “Arabian” ancestry was salient at the time of the Act’s drafting, South Asian caste was not.

Notwithstanding, in light of the Court’s precedent and the EEOC’s definition of “race” as encompassing ancestry discrimination, there remains a sound basis to find that discrimination based on South Asian caste is encompassed within Title VII’s category of “race.”

The analysis of whether caste discrimination is discrimination based on “color” is similar to the analysis under “race.” Just as with “race,” it likely rises or falls based on controversial questions about the nature of caste, along with difficult questions about the meaning of “color.”

Like “race,” “color” is not defined by Title VII. The EEOC explains that “[c]olor discrimination occurs when a person is discriminated against based on his/her skin pigmentation (lightness or darkness of the skin), complexion, shade, or tone. Color discrimination can occur between persons of different races or ethnicities, or even between persons of the same race or ethnicity.” 110

Based on the EEOC’s interpretation and a fair interpretation of the text, it does seem that for caste discrimination to be discrimination on the basis of “color” it must be related to discrimination based on skin “pigmentation . . . , complexion, shade, or tone” 111 (which, for ease, we call “visual skin color”). Finding that caste identity is related to visual skin color is difficult. 112 There is some empirical support for the claim, 113 but at the moment the strength of that relationship is uncertain. 114 As a historical matter, varna has one definition which literally translates to “color.” 115 If this referred to visual skin color, then there may be a strong basis — grounded in history and continued by a hereditary, endogamous system — to find caste discrimination as a type of color discrimination. But the consensus scholarly view seems to be that varna did not refer to skin color. 116

As a result, and based on our current understanding, we contend that for purposes of interpreting Title VII, caste discrimination is not best understood as discrimination on the basis of “color.”

D. Religion

What about religion? We contend that there is a plausible argument that caste discrimination can be viewed as discrimination based on religion.

Importantly, discrimination on the basis of religion can be on the basis of religious heritage. 117 That is, if an employee is discriminated against because their ancestors had particular religious beliefs or had a particular religious association, that is religious discrimination, even if the employee does not have those beliefs or accept that association.

Now, suppose a manager discriminates against an employee for their caste identity. The employee has the caste identity of being a Shudra or a Dalit. We know that is a feature of their religious heritage, and so we need not further ask whether the employee has any particular religious beliefs or accepts the association. The question is firmly whether this feature of their heritage is religious heritage. We think it is.

First, caste identity is inextricably linked to religious practice. Caste identity places one in a particular (complex) hierarchy in how they are viewed within a religious community, and in religious terms such as purity, pollution, and piety. In particular, someone being a Shudra or a Dalit means that they are, due to bigotry, seen as occupying a lesser position or role in their religious community — whatever their religion is. Historically, access to places of worship has, and continues to be, closely linked to one’s caste identity. 118 And it is a core facet of caste that it places one in that hierarchy. Consequently, discrimination based on caste is discrimination based on one’s role in their religious community — and that is religious discrimination. 119

An example may clarify: Suppose an employee of unknown religion confesses to their manager that their clan is seen as the lowest in their religious community — but the employee gives no further details about their religion. The manager is disgusted by this and fires them. In so doing, the manager is discriminating against the employee because of a facet of their religious identity. Even though the manager is largely ignorant of the employee’s religious identity, that is still plainly religious discrimination.

In a similar vein, we might also argue that caste identity always qualifies one’s religious identity. It is, in a sense, being part of a particular sect of a religion. Understood thusly, it is pellucid that caste discrimination should constitute religious discrimination.

Now one might object that caste identity is compatible with different religious identities. For example, one can be a Shudra or a Dalit and be of many different religious backgrounds — among other things, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Christian, Muslim, Buddhist. What if the manager does not care at all about the employee’s religion? Would this take caste discrimination outside the scope of religious discrimination?

We think not. First, as argued above, we think that caste discrimination is discrimination based on position in religious society — and thus is religious discrimination. But caste also impacts other parts of one’s life, so the objecting manager may protest that religion has nothing to do with their motivations. Even still, we think the argument is unavailing for another reason: because caste relates to religious heritage. That is, to discriminate against someone based on caste is usually to discriminate against them on the basis that they had an ancestor who occupied a certain position in Hindu society. This is for the simple fact that the caste system is inherited from Hindu society — and one’s caste identity arises from ancestors who occupied a certain position in that Hindu society. We contend that this is religious discrimination. That is because we understand discrimination based on religious heritage as discrimination on the basis of religion, irrespective of the employee’s actual beliefs. 120 But this may also be properly considered discrimination on the basis of ancestry, and therefore as discrimination on the basis of race or national origin. Important here is to recognize that there may be overlap between these categories. 121

In light of that, we can put this idea simply in terms of the but-for test: But for the employee having an ancestor who had a particular caste identity as defined and dictated by Hindu religious practice, the employee would not have been discriminated against. Ergo, but for the employee having a particular Hindu heritage, the employee would not have been discriminated against. Hence, had the employee’s ancestors not been Hindu, the employee would not have their caste identity (that was the subject of discrimination). That is then clearly religious (heri-tage) discrimination.

The conceptual test reaches the same conclusion: one cannot understand the employee’s caste identity without appeal to certain Hindu ideas — thus, caste identity is conceptually dependent on religious practice and is therefore religious discrimination. 122

E. Mixed Motivation

One’s caste identity may be determined by myriad features, other than purely ancestral traits. Their caste identity could, for example, be defined by adopted religion, where one lives, and what languages one speaks, among other things. 123 Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, himself a Dalit, converted to Buddhism from Hinduism because he believed caste discrimination was endemic to Hinduism. 124 In addition to his own conversion, Ambedkar led a mass conversion movement, called the Ambedkarite Buddhism movement (or the Dalit Buddhist movement). 125 Those who were or are part of that movement may identify as Dalit Buddhists, due to their ancestral Dalit identity and their non-ancestral trait of their religious beliefs.

Discrimination against someone based on this combined identity — here, being a Dalit Buddhist — will in the vast majority of cases satisfy the but-for causation test with respect to the ancestral portion of their caste identity. For example, we could imagine someone who discriminated against a Dalit Buddhist, but not a Dalit Hindu nor a non-Dalit Buddhist. The discriminator’s motivation for discrimination is not simply that the employee is a Dalit, but that they are a Dalit who flouted Hindu identity by converting to Buddhism. However, in such an example, but for the person’s Dalit identity, they would not have been discriminated against. 126

One common strategy to defeat recognizing discrimination on mixed-motivation is to disentangle the purportedly separate motivations and then question each in isolation. For example, suppose an employee claims she is being discriminated against for being a Black woman, but the employer also discriminated against non-Black women as well as Black men. Applying a “divide-and-conquer” strategy, the employer may be able to undermine but-for causation on either of the bases of being Black or being a woman, by using non-Black employees (including discriminated-against women) as comparators for assessing the racial component of her claim, while using male employees (including discriminated-against Black men) as comparators for the gendered component. A similar argument might arise against the Dalit Buddhist, where the employer discriminates against non-Buddhist Dalits as well as non-Dalit Buddhists.

Here, Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work is critical and illuminating. Among her observations, she recognized that discrimination across multiple axes of identity may result in particularly pernicious treatment for the targets of such discrimination. 127 Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality may allow targets of multiaxial discrimination to use comparators who suffer discrimination, but not as severe, to ground their claims. 128 In our examples, if Dalit Buddhists are treated more severely than Dalit non-Buddhists and non-Dalit Buddhists, they can still ground their claim as they suffer worse treatment than these comparators. 129

Caste discrimination is in our midst in the United States. Given the nature of caste, which seeks to indelibly mark and stigmatize, this discrimination reaches all facets of life, and thus, it is no surprise that it enters our workplaces. This issue requires our collective awareness and our vigilance. We have argued that Title VII gives us the tools to ensure that we can prevent, rectify, and ensure restitution for caste discrimination. In particular, we have shown how under the text of Title VII, in light of the Supreme Court’s teaching in Bostock v. Clayton County , caste discrimination is cognizable as race discrimination, religious discrimination, and national origin discrimination.

While these arguments are strong, given that judicial interpretation of Title VII’s protections are in flux, the surest way to ensure that workers who experience caste discrimination are able to access recourse is to explicitly enshrine “caste” as a prohibited basis of discrimination, in both executive-branch policy and in the text of Title VII itself. The EEOC could issue an opinion letter or guidance clarifying that Title VII’s provisions prohibiting race, national origin, and/or religious discrimination forbid discrimination on the basis of caste. An even stronger protection, of course, would be for Congress to pass legislation that explicitly states that caste discrimination is unlawful under Title VII. Even in this time of extreme partisanship, this is uncontroversial and should garner bipartisan support. 130 Furthermore, though we do not contend that EEOC guidance or amending Title VII thusly would serve as a magic-bullet solution to a complicated, deep-rooted problem, it would have an important signaling effect, putting workplaces on notice that caste-based discrimination is real and must be vigilantly addressed. Finally, although we address South Asian caste discrimination in particular, there are other types of “caste” and ancestry discrimination that occur around the globe. 131 We think that this case study of caste discrimination, and how it may be addressed by Title VII, applies generally. In that spirit, both the executive branch and Congress should act to clarify that all varieties of global “caste” discrimination are unlawful and intolerable in a just society.

* Assistant Professor, South Texas College of Law. ** J.D., 2013, Yale Law School. The views expressed in this Essay represent solely the personal views of the authors. The South Asian caste system was and is a paradigm of injustice. It has perpetuated incomprehensible suffering. We wish to acknowledge that we are, as a matter of ancestry, members of the dominant Brahmin caste — a designation that has conferred upon us systemic privilege we have done nothing to deserve. We would like to thank Susannah Barton Tobin, Mitchell Berman, Anisha Gupta, Alexander Platt, Charles Rocky Rhodes, Peter Salib, Anuradha Sivaram, and Eric Vogelstein for insightful comments and questions. We would also like to acknowledge the pathbreaking work of Equality Labs on these issues, which served as an inspiration for this Essay.

^ See Yashica Dutt, Opinion, The Specter of Caste in Silicon Valley , N. Y. TIMES (July 14, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/opinion/caste-cisco-indian-americans-discrimination.html [ https://perma.cc/DMS8-LCTF ]; David Gilbert, Silicon Valley Has a Caste Discrimination Problem , VICE NEWS (Aug. 5, 2020, 8:16AM), https://www.vice.com/en/article/3azjp5/silicon-valley-has-a-caste-discrimination-problem [ https://perma.cc/W3V8-H6WN ]; Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Opinion, A New Lawsuit Shines a Light on Caste Discrimination in the U.S. and Around the World , WASH. POST (July 13, 2020, 4:57 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/07/13/new-lawsuit-shines-light-caste-discrimination-us-around-world [ https://perma.cc/5CV8-LC64 ].

^ Paige Smith, Caste Bias Lawsuit Against Cisco Tests Rare Workplace Claim , BLOOMBERG L. (July 17, 2020, 2:45 AM), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/caste-bias-lawsuit-against-cisco-tests-rare-workplace-claim [ https://perma.cc/2E6E-A7TN ]; Press Release, California Dep’t of Fair Emp. & Hous., DFEH Sues Cisco Systems, Inc. and Former Managers for Caste-Based Discrimination (June 30, 2020), https://www.dfeh.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2020/06/Cisco_2020.06.30.pdf [ https://perma.cc/VWC2-79J7 ].

^ Press Release, California Dep’t of Fair Emp. & Hous., supra note 2. DFEH initially brought suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, alleging violations of Title VII. Id . Thereafter, on October 16, 2020, DFEH voluntarily dismissed the suit without prejudice, stating its intention to refile in California state court. California Drops Caste Discrimination Case Against Cisco, Says Will Re-file , The Wire (Oct. 21, 2020), https:// thewire.in/caste/california-drops-caste-discrimination-case-against-cisco-says-will-re-file [ https://perma.cc/P6Z7-E8NM ]. This action may have been because of some question as to whether caste discrimination is cognizable under Title VII or other federal law. If so, we contend this Essay establishes that it is.

^ Gilbert, supra note 1.

^ E.g ., Hum. Rts. Watch, Caste Discrimination (2001), https://www.hrw.org/reports/pdfs/g/general/caste0801.pdf [ https://perma.cc/YA8L-Z8PR ] (discussing discrimination against Dalits in South Asia); Hillary Mayell, India’s “Untouchables” Face Violence, Discrimination , Nat’l Geographic (June 2, 2003), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/pages/article/indias-untouchables-face-violence-discrimination [ https://perma.cc/L5XE-263U ] (“Human rights abuses against [‘untouchables’], known as Dalits, are legion.”).

^ We will use the term “dominant caste” to refer to the so-called “upper castes,” which better reflects the hierarchy of power that has created systemic oppression of Dalits, Adivasis, and other disfavored castes. We will use the term “oppressed caste” to refer to Dalits, Adivasis, and other disfavored castes. See infra notes 41–44 and accompanying text.

^ See Dutt, supra note 1.

^ Nitasha Tiku, India’s Engineers Have Thrived in Silicon Valley. So Has Its Caste System ., Wash. Post (Oct. 27, 2020, 6:45 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/10/27/indian-caste-bias-silicon-valley [ https://perma.cc/VP2F-U7QX ].

^ Maari Zwick-Maitreyi, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, Natasha Dar, Ralph F. Bheel & Prathap Balakrishnan, Equal. Labs, Caste in the United States: A Survey of Caste Among South Asian Americans 10 (2018), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58347d04bebafbb1e66df84c/t/603ae9f4cfad7f515281e9bf/1614473732034/Caste_report_2018.pdf [ https://perma.cc/7PW3-DUL5 ] [hereinafter Caste in the United States ].

^ Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents 128 (2020).

^ Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, Opinion, Securing the Rights of India’s “Untouchables ,” The Hill (Feb. 27, 2018, 3:30 PM), https://thehill.com/opinion/international/375851-securing-the-rights-of-indias-untouchables [ https://perma.cc/2L2S-9Z67 ].

^ 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq .

^ 140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020).

^ Id . at 1737.

^ E.g ., A New Dictionary of the Social Sciences 194 (G. Duncan Mitchell ed., 2d ed. 1979) (defining “social stratification” and explaining the concept of “caste”).

^ See generally, e.g ., Elijah Obinna, Contesting Identity: The Osu Caste System Among Igbo of Nigeria , 10 Afr. Identities 111 (2012) (describing the Osu caste system among the Igbo people in Nigeria); Tal Tamari, The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa , 32 J. Afr. Hist . 221 (1991) (explaining endogamous groups that exist in West Africa); Hiroshi Wagatsuma & George A. De Vos , The Ecology of Special Buraku , in Japan’s Invisible Race: Caste in Culture and Personality 113–28 ( George A. De Vos & Hiroshi Wagatsuma eds., 1966) (describing Japan as having a caste system and discussing the position and oppression of the Buraku people); Paul Eckert, North Korea Political Caste System Behind Abuses: Study , Reuters (June 5, 2012, 9:11 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-korea-north-caste/north-korea-political-caste-system-behind-abuses-study-idUSBRE85505T20120606 [ https://perma.cc/NZ9Z-4J3L ] (describing the “Songbun” caste system in North Korea).

^ A New Dictionary of the Social Sciences , supra note 15, at 194 (stating that the “classical Hindu system of India approximated most closely to pure caste”).

^ The caste system continues to exist in some form in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan, among other countries, which collectively have a population of nearly 1.8 billion people. See Population, Total — India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal , World Bank Grp ., https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2019&locations=IN-PK-BD-NP&start=2019&view=bar [ https://perma.cc/8YYT-XN24 ] (searches for country populations); Iftekhar Uddin Chowdhury, Caste-Based Discrimination in South Asia: A Study of Bangladesh 2, 51–55 (Indian Inst. Dalit Stud., Working Paper Vol. III No. 7, 2009), http://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/user_folder/pdf/New_files/Bangladesh/Caste-based_Discrimination_in_Bangladesh__IIDS_working_paper_.pdf [ https://perma.cc/CQ5N-VFHJ ]; Peter Kapuscinski, More “Can and Must Be Done” to Eradicate Caste-Based Discrimination in Nepal , UN News (May 29, 2020), https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/05/1065102 [ https://perma.cc/JZ62-FVUB ]; Rabia Mehmood, Pakistan’s Caste System: The Untouchable’s Struggle , Express Trib . (Mar. 31, 2012), https://tribune.com.pk/story/357765/pakistans-caste-system-the-untouchables-struggle [ https://perma.cc/4H9Z-46SJ ]; Pakistan Dalit Solidarity Network & Int’l Dalit Solidarity Network , Caste-Based Discrimination in Pakistan 2–3 (2017), https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1402076/1930_1498117230_int-cescr-css-pak-27505-e.pdf [ https://perma.cc/77TM-P8WB ]; Mari Marcel Thekaekara, Opinion, India’s Caste System Is Alive and Kicking — And Maiming and Killing , The Guardian (Aug. 15, 2016, 11:55 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/15/india-caste-system-70-anniversary-independence-day-untouchables [ https://perma.cc/ER4H-L4KY ].

^ In one important passage, the Rig Veda describes a four-part social hierarchy — of the brahmana , rajanya (later associated with the kshatriya class), vaishya , and shudra . The Hymns of the Rigveda 10.90.12 (Ralph T.H. Griffith trans., Motilal Banarsidass 1973). The Bhagavad Gita also details the general distinction of caste. The B hagavad-GÎt 4.13 , at 110 (A. Mahâdeva Śâstri trans., 2d ed. 1901) (describing the four-fold division of mankind). The Dharmasastras and Dharmasutras , compilations of texts about various Hindu cultural practices, offer an extremely detailed account of the operation of the caste system. The proper understanding of all of these sources is up for debate. See, e.g ., Dharmasūtras: The Law Codes of Āpastamba, Gautama, Baudhāyana, and Vasiṣṭha , at xlii–xliii (Patrick Olivelle ed., trans., Oxford U. Press 1999) (contending that the Dharmasutras are “normative texts” but contain “[d]ivergent [v]oices,” id . at xlii); J.E. Llewellyn, The Modern Bhagavad Gītā : Caste in Twentieth-Century Commentaries , 23 Int’l J. Hindu Stud . 309, 309–23 (2019) (analyzing differing interpretations of caste by leading Hindu thinkers); M.V. Nadkarni, Is Caste System Intrinsic to Hinduism? Demolishing a Myth , 38 Econ. & Pol. Wkly . 4783, 4783 (2003) (arguing that Hinduism did not support the caste system); Chhatrapati Singh, Dharmasastras and Contemporary Jurisprudence , 32 J. Indian L. Inst . 179, 179–82 (1990) (explaining the various ways of interpreting the Dharmasastras ); Debate Casts Light on Gita & Caste System , Times of India (Apr. 8, 2017, 7:10 PM), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/58072655.cms [ https://perma.cc/Q5XG-MSA9 ] (describing a “heated debate” over interpretations of the Bhagavad Gita ). Regardless, what is clear is that caste was endemic to Hindu practice over time.

^ See generally, e.g ., U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, Islam in Bangladesh 1–64 (1992) (explaining the distinctive nature of Islam in Bangladesh and Bengali communities); Adil Hussain Khan, From Sufism to Ahmadiyya 42–90 (2015) (detailing the rise of the distinctive Ahmadiyya sect of Islam that arose in Punjab); Rowena Robinson, Christians of India 11–38, 103–39 (2003) (explaining the distinctive Christianity that has developed in India, arising from the mixing of Christian theology and practice and regional traditions); Paul Zacharia, The Surprisingly Early History of Christianity in India , Smithsonian Mag . (Feb. 19, 2016), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/how-christianity-came-to-india-kerala-180958117 [ https://perma.cc/KRY4-UN3C ] (describing the traditions of the modern Syrian Christians of Kerala).

^ See generally Chandrashekhar Bhat, Ethnicity and Mobility 1–9 (1984); Declan Quigley, The Interpretation of Caste 4 (1993).

^ Sumeet Jain, Note, Tightening India’s “Golden Straitjacket”: How Pulling the Straps of India’s Job Reservation Scheme Reflects Prudent Economic Policy , 8 Wash. U. Glob. Stud. L. Rev . 567, 568 n.7 (2009) (outlining the four-part varna system).

^ Sean A. Pager, Antisubordination of Whom? What India’s Answer Tells Us About the Meaning of Equality in Affirmative Action , 41 U.C. Davis L. Rev . 289, 325 (2007) (discussing the so-called “untouchables,” outside the four-part varna system).

^ Bhat, supra note 21, at 2–3 (discussing the panchama varna and its traditional Vedic understanding); Varsha Ayyar & Lalit Khandare, Mapping Color and Caste Discrimination in Indian Society , in The Melanin Millennium 71, 75, 83 (Ronald E. Hall ed., 2012) (defining the fifth caste as describing “ex-untouchables,” id . at 83, or those outside of the varna system).

^ See Bhat , supra note 21, at 6–7; Ayyar & Khandare, supra note 25, at 75.

^ See Dalits , Minority Rts. Grp. Int’l , https://minorityrights.org/minorities/dalits [ https://perma.cc/TVV9-UN9R ].

^ Bhat, supra note 21, at 3 (discussing the jati system).

^ Padmanabh Samarendra, Census in Colonial India and the Birth of Caste , 46 Econ. & Pol. Wkly . 51, 52 (2011) (explaining the variety of factors that inform jati identity, based in part on region).

^ Who Are Dalits? , Navsarjan Tr ., https://navsarjantrust.org/who-are-dalits [ https://perma.cc/599J-QEHY ] (detailing the subdivisions based on profession within the Dalit community).

^ “Adivasi” and “scheduled tribe” are the terms for certain tribes in the Subcontinent. The term “Adivasi” itself means “original inhabitants.” Adivasis , Minority Rts. Grp. Int’l , https://minorityrights.org/minorities/adivasis-2 [ https://perma.cc/Q34Q-2L95 ]. They face severe discrimination in India and South Asia. Id .

^ Robert Meister, Discrimination Law Through the Looking Glass , 1985 Wis. L. Rev . 937, 975 (book review).

^ See supra note 19 and accompanying text.

^ See, e.g ., Indian Temple “Purified” After Low-Caste Chief Minister Visits , Reuters (Sept. 30, 2014, 9:10 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-foundation-india-caste/indian-temple-purified-after-low-caste-chief-minister-visits-idUSKCN0HP1DE20140930 [ https://perma.cc/8NHE-MB9T ].

^ Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 10.

^ Dipankar Gupta, Interrogating Caste 54–147 (2000) (observing that individual castes do not necessarily recognize claims of inferiority and thus questioning claims of strict hierarchy between the castes, especially between the “Brahman, Baniya [or vaishya ], [and] Raja [or kshatriya ],” id . at 116).

^ See Jain, supra note 22, at 569 n.7.

^ See sources cited supra note 5.

^ Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, Where Are the Shudras? , Caravan (Sept. 30, 2018), https://caravanmagazine.in/caste/why-the-shudras-are-lost-in-today-india [ https://perma.cc/S6DY-U4BR ] (discussing discrimination against Shudra communities in India); Tapasya, Not Just “Dalits”: Other-Caste Indians Suffer Discrimination Too , Diplomat ( Aug. 27, 2019), https://thediplomat.com/2019/08/not-just-dalits-other-caste-indians-suffer-discrimination-too [ https://perma.cc/M67R-WE9G ].

^ See, e.g ., T.M. Scanlon, Why Does Inequality Matter? 26 (2018) (“Caste systems and societies marked by racial or sexual discrimination are obvious examples of objectionable inequality.”).

^ See generally Kaivan Munshi, Caste and the Indian Economy , 57 J. Econ. Literature 781 (2019) (explaining that “[c]aste plays a role at every stage of an Indian’s economic life,” from school, to university, to the labor market, and into old age, id . at 781).

^ See, e.g ., Nirmala Carvalho, Indian Church Admits Dalits Face Discrimination , Crux (Mar. 24, 2017), https://cruxnow.com/global-church/2017/03/indian-church-admits-dalits-face-discrimination [ https://perma.cc/M8QD-6E28 ]; Dheer, supra note 39 (observing that there were three separate Sikh shrines based on caste identity); Anuj Kumar, Dalit Women Not Allowed to Enter Temple , The Hindu (Nov. 1, 2019, 2:27 AM), https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/dalit-women-not-allowed-to-enter-temple/article29847456.ece [ https://perma.cc/BGJ5-HDA2 ]; Tension over Temple Entry by Dalits , The Hindu (Sept. 2, 2020, 6:08 PM), https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/tension-over-temple-entry-by-dalits/article32505553.ece [ https://perma.cc/29N4-DX85 ]; Shivam Vij, In Allahpur, a Moment of Truth , Pulitzer Ctr . (Sept. 12, 2011), https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/allahpur-moment-truth [ https://perma.cc/G3A4-LRKE ] (detailing different mosques based on caste identity). Surveying the news, the vast majority of reported incidents of caste discrimination in places of worship involve Hindu temples. Many of these are not even reported or openly identified, because they are unspoken but known norms that oppressed castes do not dare transgress. There is reason to believe that such caste discrimination is prevalent across South Asian religions, but that does not absolve Hindu practice. Instead, it seeks acknowledgment of the extent of the evil.

^ See, e.g ., Shamani Joshi, A Community in Gujarat Has Banned Inter-caste Marriage and Mobile Phones for Unmarried Girls , Vice (July 18, 2019, 3:02 AM), https://www.vice.com/en/article/evye5e/a-community-in-gujarat-india-has-banned-inter-caste-marriage-and-mobile-phones-for-unmarried-girls [ https://perma.cc/KCT9-CZK8 ].

^ See, e.g ., Couple, Who Had “Intercaste Marriage,” Killed , Hindustan Times (June 28, 2019, 12:07 AM), https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/couple-who-had-intercaste-marriage-killed/story-3cmlhKaraKeGMwoQ6ytxeL.html [ https://perma.cc/245B-D576 ]; Dalit Man Killed by In-Laws Over Inter-caste Marriage: Gujarat Cops , NDTV (July 9, 2019), https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/dalit-man-killed-by-in-laws-over-inter-caste-marriage-gujarat-cops-2066848 [ https://perma.cc/8YMQ-JD6R ].

^ See, e.g ., Hum. Rts. Watch , supra note 5, at 8 (stating that Dalits are often not allowed to enter the houses of so-called upper-caste people).

^ See, e.g ., Dalits, OBCs Forced to Bury Their Deceased by the Roadside , Sabrangindia (Mar. 21, 2020), https://sabrangindia.in/article/dalits-obcs-forced-bury-their-deceased-roadside [ https://perma.cc/V3GT-759U ]; Karal Marx, Denied Access to Crematorium, Dalits “Airdrop” Dead in Tamil Nadu , Times of India (Aug. 22, 2019, 2:51 PM), http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/70779016.cms [ https://perma.cc/7FKN-JBHF ]; Sanjay Pandey, Crematorium Turns “Casteist” as “Upper Caste” People Forbid Funeral of Dalit Woman in Uttar Pradesh , Deccan Herald (July 28, 2020, 4:58 PM), https://www.deccanherald.com/national/crematorium-turns-casteist-as-upper-caste-people-forbid-funeral-of-dalit-woman-in-uttar-pradesh-866699.html [ https://perma.cc/WC24-EGJ8 ]; Anand Mohan Sahay, Backward Muslims Protest Denial of Burial , Rediff India Abroad (Mar. 6, 2003, 2:58 AM), https://www.rediff.com/news/2003/mar/06bihar.htm [ https://perma.cc/85QM-F4YA ].

^ See, e.g ., Soutik Biswas, Hathras Case: Dalit Women Are Among the Most Oppressed in the World , BBC (Oct. 6, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-54418513 [ https://perma.cc/WW9P-45XH ]; Vineet Khare, The Indian Dalit Man Killed for Eating in Front of Upper-Caste Men , BBC (May 20, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-48265387 [ https://perma.cc/LR9D-T2QU ]; Nilanjana S. Roy, Viewpoint: India Must Stop Denying Caste and Gender Violence , BBC (June 11, 2014), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-27774908 [ https://perma.cc/8VK3-VJN6 ]; Gautham Subramanyam, In India, Dalits Still Feel Bottom of the Caste Ladder , NBC News (Sept. 13, 2020, 4:30 AM), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/india-dalits-still-feel-bottom-caste-ladder-n1239846 [ https://perma.cc/2Z67-BPA5 ].

^ See, e.g ., Ilaiah Shepherd, supra note 44 (discussing lack of representation for Shudra communities in India); Bhola Paswan, Dalits and Women the Most Under-Represented in Parliament , The Record (Mar. 3, 2018), https://www.recordnepal.com/data/dalits-and-women-the-most-under-represented-in-parliament [ https://perma.cc/5C27-Q3D9 ].

^ In India, caste discrimination was explicitly addressed in the Constitution, authored by Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. See Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar , Encyc. Britannica , https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bhimrao-Ramji-Ambedkar [ https://perma.cc/GX6S-AHJZ ]. Article 17 states that “‘Untouchability’ is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘Untouchability’ shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.” India Const. art. 17. These protections were further instantiated in legislation, including primarily in the Untouchability (Offences) Act of 1955, which prohibited and punished discrimination on the basis of untouchability in various arenas including religious institutions and commercial entities. Untouchable , Encyc. Britannica , https://www.britannica.com/topic/untouchable [ https://perma.cc/QLV2-VEW2 ]. In practice, enforcement of these protections has been difficult, especially in rural India. Id .; Kaivan Munshi, Why Does Caste Persist? , Indian Express (Nov. 2, 2013, 3:16 AM), https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/why-does-caste-persist [ https://perma.cc/KZW8-ENHE ] (“Given the segregation along caste lines that continues to characterise the Indian village, most social interactions also occur within the caste.”).

^ One set of “reservation” reforms in India was implemented nationally by the Mandal Commission, tasked with determining how to uplift “backward classes” — primarily through reservations and quotas. Sunday Story: Mandal Commission Report, 25 Years Later , Indian Express (Sept. 1, 2015, 12:54 AM), https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/sunday-story-mandal-commission-report-25-years-later [ https://perma.cc/VM4S-MABP ]; see also E.J. Prior, Constitutional Fairness or Fraud on the Constitution? Compensatory Discrimination in India , 28 Case W. Rsrv. J. Int’l L . 63, 81 (1996) (providing further history on the Mandal Commission); Jagdishor Panday, More Reservation Quotas Sought for Ethnic Groups , Himalayan Times (Feb. 19, 2019, 8:56 AM), https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/more-reservation-quotas-sought-for-ethnic-groups [ https://perma.cc/WBW7-PSK2 ] (discussing reservation on the basis of ethnicity and caste in Nepal).

^ See, e.g ., Shashi Tharoor, Why India Needs a New Debate on Caste Quotas , BBC (Aug. 29, 2015), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-34082770 [ https://perma.cc/H3U6-E3VN ] (“Inevitably, a backlash has set in, with members of the forward castes decrying the unfairness of affirmative action in perpetuity . . . .”).

^ See generally Caste in the United States , supra note 9; Gov. Equals. Off., Caste Discrimination and Harassment in Great Britain, Report , 2010/8 (2010), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/85524/caste-discrimination-summary.pdf [ https://perma.cc/8BPY-YMP5 ] (discussing prevalence of caste discrimination in Great Britain).

^ Babasaheb Ambedkar, 1 Writings and Speeches 5–6 (1979) (quoting Sheridhar V. Ketkar , I The History of Caste in India 4 (1909)).

^ See, e.g ., Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 12.

^ Id . at 10–11.

^ See id . at 11.

^ Wilkerson , supra note 10, at 126. In United States v. Thind , 261 U.S. 204 (1923), the Court considered whether a “high caste Hindu” was “white” for purposes of naturalization under the Immigration Act of 1917, id . at 206, ultimately answering the question in the negative, id . at 215. In support of his position, Thind’s counsel stressed Thind’s common ancestral and linguistic ties to Europe, given his “Aryan” roots. John S.W. Park, Elusive Citizenship: Immigration, Asian Americans, and the Paradox of Civil Rights 124 (2004). Thind’s counsel further wrote: “The high-caste Hindu regards the aboriginal Indian Mongoloid in the same manner as the American regards the Negro, speaking from a matrimonial standpoint.” Id .

^ Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 12.

^ Demographic Information , S. Asian Ams. Leading Together , https://saalt.org/south-asians-in-the-us/demographic-information [ https://perma.cc/4F8R-GKT3 ].

^ South Asians by the Numbers: Population in the U.S. Has Grown by 40% Since 2010 , S. Asian Ams. Leading Together (May 15, 2019), https://saalt.org/south-asians-by-the-numbers-population-in-the-u-s-has-grown-by-40-since-2010 [ https://perma.cc/XD5K-YRSD ].

^ Pub. L. No. 89-236, 79 Stat. 911 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 8 U.S.C.).

^ See Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 13–14.

^ Id . at 13.

^ See id . at 13–14.

^ Pub. L. No. 101-649, 104 Stat. 4978 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 8 U.S.C. and at 29 U.S.C. § 2920).

^ See generally Muzaffar Chishti & Stephen Yale-Loehr, Migration Pol’y Inst., The Immigration Act of 1990: Unfinished Business a Quarter-Century Later (2016), https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/1990-Act_2016_FINAL.pdf [ https://perma.cc/3WQS-SKYR ].

^ Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 14.

^ Tinku Ray, The US Isn’t Safe from the Trauma of Caste Bias , The World (Mar. 8, 2019, 9:00 AM), https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-03-08/us-isn-t-safe-trauma-caste-bias [ https://perma.cc/7LUN-U49T ].

^ See, e.g ., Buck Gee & Denise Peck, Asian Americans Are the Least Likely Group in the U.S. to Be Promoted to Management , Harv. Bus. Rev . (May 31, 2018), https://hbr.org/2018/05/asian-americans-are-the-least-likely-group-in-the-u-s-to-be-promoted-to-management [ https://perma.cc/5RNM-T6YY ]; Matt Schiavenza, Silicon Valley’s Forgotten Minority , New Republic (Jan. 11, 2018), https://newrepublic.com/article/146587/silicon-valleys-forgotten-minority [ https://perma.cc/WTG6-EKBB ].

^ See, e.g ., Ray, supra note 74.

^ Caste in the United States , supra note 9, at 26–27, 39.

^ Id . at 20.

^ See, e.g ., Paresh Dave, Indian Immigrants Are Tech’s New Titans , L.A. Times (Aug. 11, 2015, 8:57 PM), https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-indians-in-tech-20150812-story.html [ https://perma.cc/NYB3-W9QC ]; Riaz Haq, Pakistani-Americans in Silicon Valley , S. Asia Inv. Rev . (May 4, 2014), https://www.southasiainvestor.com/2014/05/pakistani-americans-in-silicon-valley.html [ https://perma.cc/Y7XK-J6HS ] (“Silicon Valley is home to 12,000 to 15,000 Pakistani Americans.”); India’s Engineers and Its Caste System Thrive in Silicon Valley: Report , Am. Bazaar (Oct. 28, 2020, 7:08 PM), https://www.americanbazaaronline.com/2020/10/28/indias-engineers-and-its-caste-system-thrive-in-silicon-valley-report-442920 [ https://perma.cc/MPR8-CYPP ] (“The tech industry has grown increasingly dependent on Indian workers.”).

^ Tiku, supra note 8.

^ 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a).

^ See Bostock v. Clayton County, 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1738–39 (2020).

^ Bostock , 140 S. Ct. at 1739.

^ Id . (citations omitted); see Michael Moore, Causation in the Law , Stan. Encyc. of Phil . (Oct. 3, 2019), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/causation-law [ https://perma.cc/7UDF-5Q5S ] (discussing the but-for test or the sine qua non test).

^ See Bostock , 140 S. Ct. at 1749.

^ See infra section II.E, pp. 479–81.

^ See Koehler v. Infosys Techs. Ltd., 107 F. Supp. 3d 940, 949 (E.D. Wis. 2015) (recognizing South Asian heritage as a national origin); Sharma v. District of Colunbia, 65 F. Supp. 3d 108, 120 (D.D.C. 2014) (same).

^ U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n, National Origin Discrimination , https://www.eeoc.gov/national-origin-discrimination [ https://perma.cc/XK6N-MJU9 ]; see also 29 C.F.R. § 1606.1 (2020) (addressing the definition of national origin under Title VII and stating that “[t]he Commission defines national origin discrimination broadly as including, but not limited to, the denial of equal employment opportunity because of an individual’s, or his or her ancestor’s, place of origin; or because an individual has the physical, cultural or linguistic characteristics of a national origin group”).

^ Michael James & Adam Burgos, Race , Stan. Encyc. of Phil . (May 25, 2020), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/race [ https://perma.cc/4ZZ2-YGWH ].

^ See generally Oliver C. Cox, Race and Caste: A Distinction , 50 Am. J. Soc . 360 (1945) (arguing that caste and race are distinct).

^ Ancestry , Merriam-Webster , https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ancestry [ https://perma.cc/7V5R-7B26 ] (defining “ancestry” as “line of descent”).

^ See supra note 34 and accompanying text.

^ U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n , EEOC-NVTA-2006-1, Questions and Answers About Race and Color Discrimination in Employment (2006) https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/questions-and-answers-about-race-and-color-discrimination-employment [ https://perma.cc/R6XW-BTZ6 ].

^ 481 U.S. 604 (1987).

^ Id . at 606.

^ Id . (quoting Al-Khazraji v. St. Francis Coll., 784 F.2d 505, 517 (3d Cir. 1986)).

^ Id . at 607.

^ Id . at 613 (quoting Al-Khazraji , 784 F.2d at 517).

^ Id .; see also Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 481 U.S. 615, 617 (1987) (holding that a claim for discrimination based on Jewish heritage is cognizable under 42 U.S.C. § 1981, for similar reasons).

^ Al-Khazraji , 481 U.S. at 610 n.4. See also Khiara M. Bridges, The Dangerous Law of Biological Race , 82 Fordham L. Rev . 21, 52–57 (2013) (same); Chinyere Ezie, Deconstructing the Body: Transgender and Intersex Identities and Sex Discrimination — The Need for Strict Scrutiny , 20 Colum. J. Gender & L . 141, 178–80 (2011) (embracing the Al-Khazraji Court’s conception of race).

^ Though the Court acknowledged the limits of biological and genetic conceptions of race, if caste can be shown to pick out “ethnic[]” and “physiognomically distinctive” traits, there may be a strong argument that caste discrimination qualifies as racial discrimination on that alternative basis.

^ One might ask whether the EEOC’s interpretation holds any weight. Even with Chevron deference, we don’t think that answers the question definitively. See Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 843 (1984) (holding that courts give deference to an agency’s interpretations of an abmiguous statute, if the agency’s interpretation is a permissible construction of the statute). Here, the Court may not even find the term “race” to be ambiguous for Chevron deference to be applicable.

^ U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n , supra note 98.

^ See generally S. Chandrasekhar, Caste, Class, and Color in India , 62 Sci. Monthly 151 (1946) (arguing against the proposition that there is a strong relationship between caste and color).

^ See, e.g ., Ayyar & Khandare, supra note 25, at 71; Skin Colour Tied to Caste System, Says Study , Times of India (Nov. 21, 2016), https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/55532665.cms [ https://perma.cc/25X3-M8HX ].

^ At the same time, discrimination on the basis of skin color is prevalent in South Asia and among South Asian populations. See generally Taunya Lovell Banks, C olorism Among South Asians: Title VII and Skin Tone Discrimination , 14 Wash. U. Glob. Stud. L. Rev . 665 (2015) (describing colorism in India and the South Asian diaspora and examining its role in employment discrimination claims filed by South Asians). Thus, certain kinds of discriminatory behavior may entangle both caste and skin color.

^ Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary 924 (1899).

^ Varna , Encyc. Britannica (Mar. 7, 2021), https://www.britannica.com/topic/varna-Hinduism [ https://perma.cc/WP5J-TAZG ] (stating that the idea that varna referenced skin color has been discredited); Neha Mishra, India and Colorism: The Finer Nuances , 14 Wash. U. Glob. Stud. L. Rev . 725, 726 n.6 (2015).

^ Gulitz v. DiBartolo, No. 08-CV-2388, 2010 WL 11712777, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2010) (“What is relevant is that Plaintiff identifies himself as ‘of Jewish heritage’ — an assertion fully supported by the fact that his father is Jewish. That Plaintiff does not practice the Jewish religion does not prevent him from being of Jewish heritage — that is, a descendant of those who did so practice — or from being discriminated against on account of the religion of his forbears.”); Sasannejad v. Univ. of Rochester, 329 F. Supp. 2d 385, 391 (W.D.N.Y. 2004) (recognizing potential religious discrimination claim of a nonpracticing Iranian Muslim, in part because of the interrelationship between national-origin discrimination and religious discrimination).

^ For example, Wilkerson describes how access to religious institutions is a core feature of caste discrimination across caste systems: “Untouchables were not allowed inside Hindu temples . . . . [They] were prohibited from learning Sanskrit and sacred texts.” Wilkerson , supra note 10, at 128.

^ Additionally, it is not easy for individuals to simply withdraw or ignore their religious community — that can come with serious costs and perils. Moreover, as we have seen, moving to another religious community may not remove the mark of caste.

^ See supra note 117 and accompanying text.

^ See Sasannejad , 329 F. Supp. 2d at 391.

^ This Essay emphasizes the cross-religious nature of caste, in order to recognize that caste discrimination can take many forms and is not necessarily confined to those who are (presently) Hindu. At the same time, in particular cases, it may be more salient to recognize the nature of caste discrimination based on the religious identity of those party to the suit. That is, for example, if the employer and employee are both Hindu, then one can appeal to the form of caste discrimination between and among Hindus to strengthen the case of religious discrimination under Title VII.

^ See supra note 33 and accompanying text.

^ Krithika Varagur, Converting to Buddhism as a Form of Political Protest , The Atlantic (Apr. 11, 2018), https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/04/dalit-buddhism-conversion-india-modi/557570 [ https://perma.cc/5G85-R94D ].

^ In any situation where but-for causation isn’t satisfied, we will likely be able to satisfy the conceptual causation test — because the concept of Dalit Buddhist identity depends on the concept of Dalit ancestry.

^ Kimberlé Crenshaw, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics , 1989 U. Chi. Legal F . 139, 140.

^ In some cases, as Crenshaw observed, this may be difficult because of the size of the class, especially if the claim is pursued on a disparate impact theory with use of empirical and statistical evidence. Id . at 143–46 (discussing Moore v. Hughes Helicopter, Inc., 708 F.2d 475 (9th Cir. 1983)). We share Crenshaw’s concerns on this front. We must continue to challenge how we recognize discrimination, beyond the formal models of causation in the law.

^ If they are not treated more severely, they may be able to pursue their claim separately under a disjunctive identity — that is, being Dalit or Buddhist. See Krishnamurthi & Salib, supra note 87 (discussing such examples and showing they are cognizable under Title VII).

^ In the United Kingdom, such legislation was floated but ultimately rejected, due to divides in the South Asian community as to the prevalence of caste discrimination. Prasun Sonwalkar, UK Government Decides Not to Enact Law on Caste Discrimination Among Indians, Community Divided , Hindustan Times (July 24, 2018, 12:22 PM), https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/uk-government-decides-not-to-enact-law-on-caste-discrimination-among-indians/story-HLDMdbZQhrNtoo4NKhxZOO.html [ https://perma.cc/4C9Q-AP98 ]. But of course, if caste discrimination actually doesn’t exist, then making caste discrimination unlawful should do little harm. Indeed, concerns of frivolous lawsuits are not new in Title VII; Title VII allows fee shifting for prevailing defendants “upon a finding that the plaintiff's action was frivolous, unreasonable, or without foundation.” Christiansburg Garment Co. v. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n, 434 U.S. 412, 421 (1978); see also 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k).

^ See supra note 107 for the discussion of understanding race discrimination as a type of caste discrimination.

- Civil Rights

- Discrimination

- Employment Law

June 20, 2021

Essay on Caste Discrimination in India

Students are often asked to write an essay on Caste Discrimination in India in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Caste Discrimination in India

Introduction.

Caste discrimination in India is a long-standing issue. It is a form of bias where people are divided into different social groups, known as castes. This system often leads to inequality and unfair treatment.

Origins of Caste System

The caste system began thousands of years ago in India. It was initially based on occupation, but over time, it became hereditary, causing deep-rooted divisions in society.

Effects of Caste Discrimination

Caste discrimination has negative effects, such as social exclusion, limited opportunities, and violence against lower castes. It hinders social development and unity.

It’s crucial to eradicate caste discrimination for a fair and inclusive society. Education, awareness, and strict laws can play a significant role in this process.

250 Words Essay on Caste Discrimination in India

Manifestations of caste discrimination.

Caste discrimination manifests in various forms, from social ostracism and economic deprivation to physical violence and educational disparities. The lower castes, often referred to as the Scheduled Castes or Dalits, face the brunt of this discrimination. They are denied access to public services, educational institutions, and job opportunities.

Legislative Measures and Their Effectiveness

India has enacted numerous laws to eradicate caste discrimination, such as the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. However, the efficacy of these laws is questionable. Despite the legislation, the caste system remains deeply ingrained in Indian society, perpetuated by cultural norms, political manipulation, and economic disparity.

Caste discrimination in India is a complex issue that requires a multifaceted solution. Legal measures alone are insufficient; they must be supplemented by social reforms and educational initiatives. Moreover, a shift in societal attitudes is needed to truly eradicate caste-based discrimination. The fight against caste discrimination is not just a legal battle but a moral one, a fight for the very soul of India.

500 Words Essay on Caste Discrimination in India

Caste discrimination in India is a deeply rooted social issue that has been prevalent for centuries. This hierarchical system, initially intended for division of labor, has morphed into a tool of oppression, perpetuating inequality and social injustice.

The Caste System: A Historical Perspective

The caste system in India, dating back to around 1500 BCE, was initially based on individuals’ professions. Over time, it evolved into a hereditary system, with four primary castes or ‘Varnas’: Brahmins (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (farmers, traders, and merchants), and Shudras (laborers). Outside of this structure were the ‘Dalits’ or ‘Untouchables’, subjected to the most severe forms of discrimination.

Caste Discrimination and Human Rights