About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

How does education affect poverty?

For starters, it can help end it.

Aug 10, 2023

Access to high-quality primary education and supporting child well-being is a globally-recognized solution to the cycle of poverty. This is, in part, because it also addresses many of the other issues that keep communities vulnerable.

Education is often referred to as the great equalizer: It can open the door to jobs, resources, and skills that help a person not only survive, but thrive. In fact, according to UNESCO, if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills (nothing else), an estimated 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. If all adults completed secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

At its core, a quality education supports a child’s developing social, emotional, cognitive, and communication skills. Children who attend school also gain knowledge and skills, often at a higher level than those who aren’t in the classroom. They can then use these skills to earn higher incomes and build successful lives.

Here’s more on seven of the key ways that education affects poverty.

Go to the head of the class

Get more information on Concern's education programs — and the other ways we're ending poverty — delivered to your inbox.

1. Education is linked to economic growth

Education is the best way out of poverty in part because it is strongly linked to economic growth. A 2021 study co-published by Stanford University and Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University shows us that, between 1960 and 2000, 75% of the growth in gross domestic product around the world was linked to increased math and science skills.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] rowth rate is extraordinarily strong,” the study’s authors conclude. This is just one of the most recent studies linking education and economic growth that have been published since 1990.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] growth rate is extraordinarily strong.” — Education and Economic Growth (2021 study by Stanford University and the University of Munich)

2. Universal education can fight inequality

A 2019 Oxfam report says it best: “Good-quality education can be liberating for individuals, and it can act as a leveler and equalizer within society.”

Poverty thrives in part on inequality. All types of systemic barriers (including physical ability, religion, race, and caste) serve as compound interest against a marginalization that already accrues most for those living in extreme poverty. Education is a basic human right for all, and — when tailored to the unique needs of marginalized communities — can be used as a lever against some of the systemic barriers that keep certain groups of people furthest behind.

For example, one of the biggest inequalities that fuels the cycle of poverty is gender. When gender inequality in the classroom is addressed, this has a ripple effect on the way women are treated in their communities. We saw this at work in Afghanistan , where Concern developed a Community-Based Education program that allowed students in rural areas to attend classes closer to home, which is especially helpful for girls.

Four ways that girls’ education can change the world

Gender discrimination is one of the many barriers to education around the world. That’s a situation we need to change.

3. Education is linked to lower maternal and infant mortality rates

Speaking of women, education also means healthier mothers and children. Examining 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, researchers from the World Bank and International Center for Research on Women found that educated women tend to have fewer children and have them later in life. This generally leads to better outcomes for both the mother and her kids, with safer pregnancies and healthier newborns.

A 2017 report shows that the country’s maternal mortality rate had declined by more than 70% in the last 25 years, approximately the same amount of time that an amendment to compulsory schooling laws took place in 1993. Ensuring that girls had more education reduced the likelihood of maternal health complications, in some cases by as much as 29%.

4. Education also lowers stunting rates

Children also benefit from more educated mothers. Several reports have linked education to lowered stunting , one of the side effects of malnutrition. Preventing stunting in childhood can limit the risks of many developmental issues for children whose height — and potential — are cut short by not having enough nutrients in their first few years.

In Bangladesh , one study showed a 50.7% prevalence for stunting among families. However, greater maternal education rates led to a 4.6% decrease in the odds of stunting; greater paternal education reduced those rates by 2.9%-5.4%. A similar study in Nairobi, Kenya confirmed this relationship: Children born to mothers with some secondary education are 29% less likely to be stunted.

What is stunting?

Stunting is a form of impaired growth and development due to malnutrition that threatens almost 25% of children around the world.

5. Education reduces vulnerability to HIV and AIDS…

In 2008, researchers from Harvard University, Imperial College London, and the World Bank wrote : “There is a growing body of evidence that keeping girls in school reduces their risk of contracting HIV. The relationship between educational attainment and HIV has changed over time, with educational attainment now more likely to be associated with a lower risk of HIV infection than earlier in the epidemic.”

Since then, that correlation has only grown stronger. The right programs in schools not only reduce the likelihood of young people contracting HIV or AIDS, but also reduce the stigmas held against people living with HIV and AIDS.

6. …and vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change

As the number of extreme weather events increases due to climate change, education plays a critical role in reducing vulnerability and risk to these events. A 2014 issue of the journal Ecology and Society states: “It is found that highly educated individuals are better aware of the earthquake risk … and are more likely to undertake disaster preparedness.… High risk awareness associated with education thus could contribute to vulnerability reduction behaviors.”

The authors of the article went on to add that educated people living through a natural disaster often have more of a financial safety net to offset losses, access to more sources of information to prepare for a disaster, and have a wider social network for mutual support.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to education — and growing

Last August, UNICEF reported that half of the world’s 2.2 billion children are at “extremely high risk” for climate change, including its impact on education. Here’s why.

7. Education reduces violence at home and in communities

The same World Bank and ICRW report that showed the connection between education and maternal health also reveals that each additional year of secondary education reduced the chances of child marriage — defined as being married before the age of 18. Because educated women tend to marry later and have fewer children later in life, they’re also less likely to suffer gender-based violence , especially from their intimate partner.

Girls who receive a full education are also more likely to understand the harmful aspects of traditional practices like FGM , as well as their rights and how to stand up for them, at home and within their community.

Fighting FGM in Kenya: A daughter's bravery and a mother's love

Marsabit is one of those areas of northern Kenya where FGM has been the rule rather than the exception. But 12-year-old student Boti Ali had other plans.

Education for all: Concern’s approach

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. Last year, our work to promote education for all reached over 676,000 children. Over half of those students were female.

We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Concern has brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers.

More on how education affects poverty

6 Benefits of literacy in the fight against poverty

Child marriage and education: The blackboard wins over the bridal altar

Project Profile

Right to Learn

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

- Get involved

The transformative power of education in the fight against poverty

October 16, 2023.

Zubair Junjunia, a Generation17 young leader and the Founder of ZNotes, presents at EdTechX.

Zubair Junjunia

Generation17 Young Leader and founder of ZNotes

Time and again, research has proven the incredible power of education to break poverty cycles and economically empower individuals from the most marginalized communities with dignified work and upward social mobility.

Research at UNESCO has shown that world poverty would be more than halved if all adults completed secondary school. And if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, almost 171 million people could escape extreme poverty.

With such irrefutable evidence, how do we continue to see education underfunded globally? Funding for education as a share of national income has not changed significantly over the last decade for any developing country. And to exacerbate that, the COVID-19 shock pushed the level of learning poverty to an estimated 70 percent .

I have devoted the past decade of my life to fighting educational inequality, a journey that began during my school years. This commitment led to the creation of ZNotes , an educational platform developed for students, by students. ZNotes was born out of the problem I witnessed first-hand; the inequities in end-of-school examination, which significantly influence access to higher education and career opportunities. It is designed as a platform where students can share their notes and access top-quality educational materials without any limitations. ZNotes fosters collaborative learning through student-created content within a global community and levels the academic playing field with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach to content creation and peer learning.

Although I started ZNotes as a solo project, today, it has touched the lives of over 4.5 million students worldwide, receiving an impressive 32 million hits from students across more than 190 countries, especially serving students from emerging economies. We’re proud to say that today, more than 90 percent of students find ZNotes resources useful and feel more confident entering exams , regardless of their socio-economic background. These globally recognized qualifications empower our learners to access tertiary education and enter the world of work.

Sixteen-year-old Zubair set up a blog to share the resources he created for his IGCSE exams. Through word of mouth, his revision notes were discovered by students all over the world and ZNotes was born.

In rapidly changing job market, young people must cultivate resilience and adaptability. World Economic Forum highlights the importance of future skills, encompassing technical, cognitive, and interpersonal abilities. Unfortunately, many educational systems, especially in under-resourced regions, fall short in equipping youth with these vital skills.

To address this challenge, I see innovative technology as a crucial tool both within and beyond traditional school systems. As the digital divide narrows and access to devices and internet connectivity becomes more affordable, delivering quality education and personalized support is increasingly achievable through technology. At ZNotes, we are reshaping the role of students, transforming them from passive consumers to active creators and proponents of education. Empowering youth through a community-driven approach, students engage in peer learning and generate quality resources on an online platform.

Participation in a global learning community enhances young people's communication and collaboration skills. ZNotes fosters a sense of global citizenship, enabling learners to communicate with a diverse range of individuals across race, gender, and religion. Such spaces also result in redistributing social capital as students share advice for future university, internship and career pathways.

“Studying for 14 IGCSE subjects wasn't easy, but ZNotes helped me provide excellent and relevant revision material for all of them. I ended up with 7 A* 7 A, and ZNotes played a huge role. I am off to Cornell University this fall now. A big thank you to the ZNotes team!"

Alongside ensuring our beneficiaries are equipped with the resources and support they need to be at a level playing field for such high stakes exams, we also consider the skills that will set them up for success in life beyond academics. Especially for the hundreds of young people who join our internship and contribution programs , they become part of a global social impact startup and develop both academic skills and also employability skills. After engaging with our internship programs, 77% of interns reported improved candidacy for new jobs and internships.

ZNotes addresses the uneven playing field of standardized testing with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach for content creation and peer learning.

A few years ago, Jess joined our team as a Social Impact Analyst intern having just completed her university degree while she continued to search for a full-time role. She was able to apply her data analytics skills from a theoretical degree into a real-world scenario and was empowered to play an instrumental role in understanding and developing a Theory of Change model for ZNotes. In just 6 months, she had been able to develop the skills and gain experiences that strengthened her profile. At the end of internship, she was offered a full-time role at a major news and media agency that she is continuing to grow in!

Jess’s example applies to almost every one of our interns . As another one of them, Alexa, said “ZNotes offers the rare and wonderful opportunity to be at the center of meaningful change”.

Being part of an organization making a significant impact is profoundly inspiring and empowering for young people, and assuming high-responsibility roles within such organizations accelerates their skills development and sets them apart in the eyes of prospective employers.

On the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, it is a critical moment to reflect and enact on the opportunity that we have to achieving two key SDGs, Goal 1 and 4, by effectively funding and enabling access to quality education globally.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thanks for signing up as a global citizen. In order to create your account we need you to provide your email address. You can check out our Privacy Policy to see how we safeguard and use the information you provide us with. If your Facebook account does not have an attached e-mail address, you'll need to add that before you can sign up.

This account has been deactivated.

Please contact us at [email protected] if you would like to re-activate your account.

Lack of access to education is a major predictor of passing poverty from one generation to the next, and receiving an education is one of the top ways to achieve financial stability.

In other words: education and poverty are directly linked.

Increasing access to education can equalize communities, improve the overall health and longevity of a society , and help save the planet .

The problem is that about 258 million children and youth are out of school around the world, according to UNESCO data released in 2018.

Children do not attend school for many reasons — but they all stem from poverty.

Here are all the statistics, facts, and answers to questions you might have that shed light on the connection between poverty and education.

How does poverty affect education?

Families living in poverty often have to choose between sending their child to school or providing other basic needs. Even if families do not have to pay tuition fees, school comes with the added costs of uniforms, books, supplies, and/or exam fees.

Countries across sub-Saharan Africa, where the world’s poorest children live, have made a concerted effort to abolish school fees . While the ratio of students completing lower secondary school increased in the region from 23% in 1990 to 42% in 2014, enrollment is low compared to the 75% global ratio. School remains too expensive for the poorest families. Some children are forced to stay at home doing chores or need to work. In other places, especially in crisis and conflict areas with destroyed infrastructure and limited resources, unaffordable private schools are sometimes the only option .

Why does poverty stop girls from going to school?

Poverty is the most important factor that determines whether or not a girl can access education, according to the World Bank. If families cannot afford the costs of school, they are more likely to send boys than girls. Around 15 million girls will never get the chance to attend school, compared to 10 million boys.

Read More: These Are the Top 10 Best and Worst Countries for Education in 2016

Gender inequality is more prevalent in low-income countries. Women often perform more unpaid work, have fewer assets, are exposed to gender-based violence, and are more likely to be forced into early marriage, all limiting their ability to fully participate in society and benefit from economic growth.

When girls face barriers to education early on, it is difficult for them to recover. Child marriage is one of the most common reasons a girl might stop going to school. More than 650 million women globally have already married under the age of 18. For families experiencing financial hardship, child marriage reduces their economic burden , but it ends up being more difficult for girls to gain financial independence if they are unable to access a quality education.

Lack of access to adequate menstrual hygiene management also stops many girls from attending school. Some girls cannot afford to buy sanitary products or they do not have access to clean water and sanitation to clean themselves and prevent disease. If safety is a concern due to lack of separate bathrooms, girls will stay home from school to avoid putting themselves at risk of sexual assault or harassment.

Read More: 10 Barriers to Education Around the World

An educated girl is not only likely to increase her personal earning potential but can help reduce poverty in her community, too.

“Educated girls have fewer, healthier, and better-educated children,” according to the Global Partnership for Education.

When countries invest in girls’ education, it sees an increase in female leaders, lower levels of population growth, and a reduction of contributions to climate change.

Can education help break the cycle of poverty?

Education promotes economic growth because it provides skills that increase employment opportunities and income. Nearly 60 million people could escape poverty if all adults had just two more years of schooling, and 420 million people could be lifted out of poverty if all adults completed secondary education, according to UNESCO.

Education increases earnings by roughly 10% per each additional year of schooling. For each $1 invested in an additional year of schooling, earnings increase by $5 in low-income countries and $2.5 in lower-middle income countries.

Read More: 264 Million Children Are Denied Access To Education, New Report Says

Education reduces many issues that stop people from living healthy lives, including infant and maternal deaths, stunting, infant and maternal deaths, vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, and violence.

How can we end extreme poverty through education?

There are more children enrolled in school than ever before — developing countries reached a 91% enrollment rate in 2015 — but we must fully close the gap.

World leaders gathered at the United Nations headquarters to address the disparity in 2015 and set 17 Global Goals to end extreme poverty by 2030. Global Goal 4: Quality Education aims to "end poverty in all its forms everywhere."

Read More: How We Can Be the Generation to End Extreme Poverty

The first step to achieving quality education for all is acknowledging that it is a vital part of sustainable development. Citizens, governments, corporations, and philanthropists all have an important role to play. Learn how to ensure global access to education to end poverty by taking action here .

Global Citizen Explains

Defeat Poverty

Understanding How Poverty is the Main Barrier to Education

Feb. 7, 2020

A World of Hardship: Deep Poverty and the Struggle for Educational Equity

This post is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores evidence-based and equity-focused strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

One day you get out there and actually see where the children you serve on a daily basis come from. Several teachers came back after delivering food and broke down in tears telling me what they saw. A student was living in a home with no roof; they’ve got a tarp for a roof kept on by bricks and tires. Homes didn’t have doors. —Principal of a rural high-poverty elementary school

As this quote powerfully conveys, families living in deep poverty face profound material, social, and emotional hardships. Households in deep poverty suffer from food shortages, unemployment, unstable housing, inadequate medical care , electrical shutoffs, and isolation.

Children living in households in deep poverty are often “invisible” to more affluent community members—and likely to many educators as well. Too often, the plight of students living in deep poverty is subsumed under the broad definition of poverty, which does not reveal the unique hardships that are endured by those families and children with virtually no material resources . For those of us who believe in educational equity, making the invisible visible is the first step in overcoming deep disadvantage.

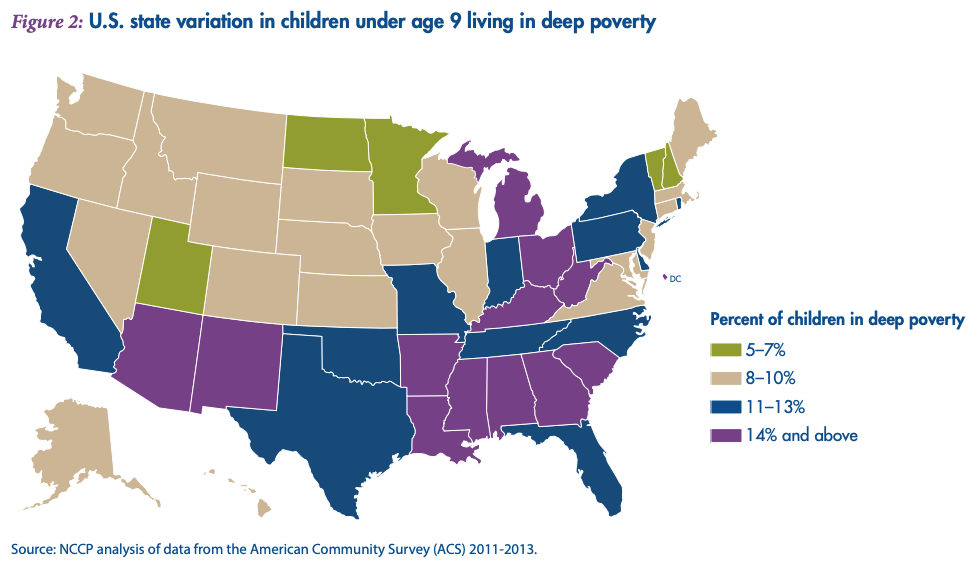

The U.S. Census Bureau defines deep poverty as living in a household with total cash income that is below 50% of the poverty threshold. As the National Center for Children in Poverty map below indicates, no state is without children living in deep poverty. Although the percentage varies considerably across states, all states have at least 5% of their children living far below the poverty line. In total, more than 5 million children in the United States live in deep poverty, including nearly 1 in 5 Black children under the age of 5.

With the explosion of the health and economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, households living in deep poverty have been pushed to the edge of survival: Nearly 4 in 10 Black and Latino households with children are struggling to feed their families . These numbers will no doubt grow as job losses mount, as do the numbers of children and adults of color who are contracting—and, in a disproportionate number of cases, dying from—COVID-19.

Why Deep Poverty Matters for Educators

Recently, Stanford researcher Sean Reardon and his colleagues conducted a national study on racial segregation and achievement gaps. In describing the findings he noted, “While racial segregation is important, it’s not the race of one’s classmates that matters, per se. It’s the fact that in America today, racial segregation brings with it very unequal concentrations of students in high- and low-poverty schools.” Another recent study of poverty and its effects on learning determined that levels of poverty matter in the abilities of students to succeed in school. According to the authors, “The experiences of children living in families with incomes just below the poverty line are likely quite different from those living in extreme poverty. Parents’ struggles to provide sufficient food and shelter for children may affect child academic achievement.”

The authors go on to note that the “depth of the poverty” matters both for the day-to-day life of students and families, and for public policy. “To determine appropriate subsidy levels and the types of services needed by children and families, policymakers need detailed data about the depth of family poverty. Studies have shown that simply classifying people as ‘in poverty’ or ‘not in poverty’ is not sufficient. The diversity in access to economic resources due to the depth of poverty helps explain the gaps in family investment in children’s education.”

The impact of poverty on children’s ability to learn is profound and occurs at an early age. A recent study of the neurological effects of deep poverty on young children’s development found that “poverty is tied to structural differences in several areas of the brain associated with school readiness skills, with the largest influence observed among children from the poorest households…. As much as 20% of the gap in test scores could be explained by maturational lags in the frontal and temporal lobes.” These effects were found to be associated with the consequences of living in deep poverty at an early age, some of which include premature and low-birthweight babies; poor nutrition and living without sufficient food; exposure to toxins, such as lead paint or contaminated drinking water; and lack of access to early learning opportunities.

If we are to educate the whole child , regardless of their family’s income, it is essential to provide an array of academic and social services that ensures that equity of opportunity reaches those students living in deep poverty.

The Importance of Accurately Determining Eligibility for Increased Services

In May 2020, the Learning Policy Institute published Measuring Student Socioeconomic Status: Toward a Comprehensive Approach . This report analyzes the limitations of the current methods used by school systems for measuring students’ socioeconomic status for purposes of allocating resources to meet their needs. Noting the limitations of determining a student’s level of poverty by her or his eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch—even when this measure is enhanced through direct certification of eligibility for other poverty-related programs—the report concludes that the development of new student poverty measures is urgently needed.

Blog Series: Learning in the Time of COVID-19

This blog series explores strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity. View all blogs >

The report also notes that researchers have suggested alternative measures of student poverty, some of which include parental education, student mobility, and community income as proxy measures. These strategies, however, do not appear to be capable of capturing the depth of an individual student’s poverty with the accuracy required to create and maintain academic and social programs designed and funded to meet the needs of students living in households in deep poverty. A more robust, reliable, and valid measure of students experiencing deep poverty is needed.

For several years, researchers at the Bendheim-Thomas Center for Research on Child Wellbeing at Princeton University have felt the pressing need to “move beyond income-based measures of poverty, ” according to Center Co-Director Kathryn Edin. She and her colleagues are currently utilizing measures of hardship that are more likely to reveal depth of poverty beyond income measures alone.

While there are a number of measures that identify deep poverty, perhaps the most direct, reliable, and valid measure available is a survey of a household’s ability to take care of the basic necessities of life. Households in deep poverty regularly experience food and housing insecurity, often can’t pay their bills, and are unable to access health care when they need it. At a time when access to the internet is essential for a student’s ability to learn online, families living in deep poverty often have their electricity shut off for lack of payment.

One of the most valid and reliable of these “material hardship” types of surveys has been used by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and, later, the Fragile Families Challenge . Material hardship measures ask direct questions about forgone consumption—that is, what families have had to do without when they may have to live on as little as two dollars a day .

Generally, surveys of material hardship consist of 10 or more questions. Below are some of the types of questions that might be included in a school-based survey to better understand the day-to-day realities for students and families:

- In the past 12 months, were you ever hungry, but didn’t eat because you couldn’t afford enough food?

- In the past 12 months, did you move in with other people even for a little while because of financial problems?

- In the past 12 months, was there anyone in your household who needed to see a doctor or go to the hospital but couldn’t go because of the cost?

- In the past 12 months, did you receive free food or meals?

- In the past 12 months, did you not pay the full amount of a gas, oil, or electricity bill?

These measures do not replace income measures; they supplement them in order to get a fuller understanding of the lived experience of families living in deep poverty. For example, as a supplementary measure, a survey of material hardship could be incorporated into the free and reduced-price lunch forms sent to families to determine their eligibility to receive meals at school. When the material hardship surveys are returned, school administrators would have a clear indication of which students are living in deep poverty.

This recommendation can be seen as a first step in a more comprehensive approach to measuring deep poverty of students. Undocumented or mixed-status families might hesitate to complete government forms for fear of deportation; some families might not complete the material hardship survey due to privacy or other concerns. Some of these concerns could be addressed in community school settings, where the ties between families and the school are often close and continuous. The establishment of trust is a bond that can help to overcome the fear of government.

More From the Blog Series

- In the Fallout of the Pandemic, Community Schools Show a Way Forward for Education

- School-Based Health Centers: Trusted Lifelines in a Time of Crisis

- County-Level Coordination Provides Infrastructure, Funding for Community Schools Initiative

To some busy school administrators, adding any survey might seem burdensome, but the returns on a short material hardship survey are very high. With this information, schools and school systems will be able to tailor programs to meet the needs of children and young adults living in families in deep poverty. These programs should support students’ health and well-being, as well as include academic enhancement and enrichment. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, waiting for the perfect measure could result in increased hardship for students trapped in deep poverty.

Toward Educational Equity

Since the 1990s, the social safety net has been basically shredded. As a result, in many communities, the local public school system is often the only entity situated to meet the needs of students from families in deep poverty by providing meals as well as a safe place to be during the day. Early intervention programs, such a free and high-quality early childhood programs , are a very promising approach to mitigating the effects of deep poverty on young children. Community schools , which provide students and families with a range of supports and services to mitigate the impact of deep poverty—from health and mental health care to before- and after-school care and social service supports—are another promising example. Ensuring that these services are available to children in deep poverty can literally mean the difference between life and death—and between a chance in life and none—for many of these young people.

These are just two examples of how information about students’ level of poverty can lead to improved and expanded services and supports to meet their needs. Of course, schools alone cannot reverse the impact of deep poverty on children, families, and communities. But without well-financed schools with the targeted resources needed to enable students’ learning, the negative effects of deep poverty on children will remain, now and in the future.

Sign up for our mailing list

Poverty and Its Impact on Students’ Education

The purpose of this position statement is to highlight the impact poverty has on students and their ability to succeed in the classroom as well as offer policy recommendations on how to best support the academic, social, emotional, and physical success of these students.

Each day countless students come to school, each with their own set of unique gifts, abilities, and challenges. Recent data has found that students living in poverty often face far more challenges than their peers. According to the National Center of Education Statistics, 19 percent of individuals under 18 lived in poverty during the 2015–16 school year. Furthermore, 24.4 percent of students attended high-poverty schools during that same year. The data also show that higher percentages of Hispanic, African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Pacific Islander students attended high-poverty schools than white students, underscoring that poverty is also an issue of equity that must be addressed.

These data show the reality of what our public education system is facing today. Nearly one-fifth of students nationwide are either living in poverty, attending a high-poverty school, or both. Poverty negatively impacts students in a variety of ways within K–12 education and beyond. This can be through a variety of different factors that are often symptoms of poverty, like health issues stemming from a nonnutritional diet, homelessness, lack of food, or the inability to receive medical treatment for illnesses. These factors often place more stress on a student, which can negatively impact the student’s ability to succeed in a school.

Students living in poverty often have fewer resources at home to complete homework, study, or engage in activities that helps equip them for success during the school day. Many impoverished families lack access to computers, high-speed internet (three-fourths of households currently have access to high-speed broadband), and other materials that can aid a student outside of school. Parents of these families often work longer hours or multiple jobs, meaning they may not be available to assist their children with their schoolwork.

Furthermore, in many high-poverty school districts, resources are sorely lacking in schools. Nearly every state has its own division of funding for school districts and education based on property taxes. Unfortunately, this system unfairly affects individuals living in poverty and the students attending school in those areas. Because property taxes are often much lower in high-poverty areas, schools in those areas receive much less than their more affluently-located counterparts. Recent data from the U.S. Department of Education state that 40 percent of high-poverty schools are not getting a fair share of state and local funds. This often leaves schools with limited budgets to address a multitude of issues, including hiring educators, updating resources for students, preparing students for postsecondary education or the workforce, dealing with unsafe infrastructure, and much more. There are often instructional gaps for those attending high-poverty schools as well. Data from the 2015–16 National Teacher and Principal Survey show that students from low-income families “are consistently, albeit modestly, more likely to be taught by lower-credentialed and novice teachers” (Garcia and Weiss). Research has also shown that many teachers in high-poverty schools are inexperienced and often less effective than their more experienced peers who are often targeted for hire by higher-income schools and districts. The lack of high-quality instruction serves to only further separate academic achievement levels for students in high-poverty schools from peers in high-income schools or districts.

Guiding Principles

- All students, regardless of income level or background, are capable of and should receive the support and resources necessary for success.

- Students from low-income families often face additional barriers that can impede academic success compared to their peers from higher-income households.

- Principals provide leadership for instilling a culture of success and support within their school and should strive to provide each student with the supports necessary to achieve this success. Principals should strive to achieve this through all available avenues, including through strategic partnerships.

- The 2015 Professional Standards for Educational Leaders state that effective educational leaders strive for equity of educational opportunity and culturally responsive practices to promote each student’s academic success and well-being.

- NASSP has previously adopted position statements on the achievement gap and preparing all students for postsecondary success that offer policy recommendations to promote equitable support for all students and adequate preparation to enter the workforce or a postsecondary institution following high school.

- NASSP developed the Building Ranks™ framework to reflect the principal’s responsibility for building culture and leading learning to foster lifelong success for each child in a rapidly changing world.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Federal Policymakers

- Advance policies that incentivize and support well-trained teachers, principals, and other educators to work and remain in high-poverty schools.

- Provide additional federal funds and resources for programs, such as Title I and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, aimed at supporting students from low-income families.

- Ensure federal funds are divided equitably so that high-poverty districts are guaranteed a fairer share of federal dollars.

- Invest in school leadership required to hire and retain well-trained school leaders, recognizing the critical role principals play in establishing a culture and learning environment that students need to be successful in a global society.

- Prioritize school improvement strategies—such as community schools—that include resources and supports to address the barriers poverty creates to student success.

- Provide additional resources and invest in programs for students from low-income families to enter postsecondary education or the workforce.

- Enact legislation aimed at improving school infrastructure, with a particular focus on buildings in high-poverty districts that pose potential health threats to students, educators, and other faculty in the school.

- Expand the maximum allowance of Pell Grants, and share information with states, local education agencies, and universities on application eligibility and processes.

- Fully fund federal programs that increase connectivity for all students, like the E-Rate Program which provides discounted telecommunications services to schools.

Recommendations for State Policymakers

- Ensure state funding formulas are properly balanced so all districts receive an equitable and sufficient share of funds based on student poverty levels, property tax revenue per district, or other evidence-based indicators of poverty.

- Reevaluate state investments in education to ensure school districts are receiving the funds necessary to promote student success.

- Prioritize school improvement strategies—such as community schools—that include resources and supports to address the barriers to student success that poverty creates.

- Invest in curriculum that prepares students for 21st-century employment and participation in a democracy. This will prepare students for life beyond secondary education and better enable them to be successful in the workforce and financially secure.

- Prioritize and invest in state financial aid for school districts based on need instead of merit, which disproportionately helps high-income and white students.

- Make investments over a long-term basis rather than short term, as long-term investments have a proven track record of improving high-poverty school districts.

Recommendations for District Leaders

- Make sure that your district and school funding systems ensure equal access to core educational services for each student in K–12 education.

- Ensure that school funding systems provide additional resources for low-income students to ensure they have a more level playing field for achieving success.

- Use per-pupil expenditure (PPE) data to evaluate district funding decisions and make changes based on this data when inequities are presented.

- Support ongoing learning for school leaders, recognizing that their role is changing and that the demands of a high-poverty schools are expanding, requiring continual development.

- Advance policies that ensure highly-qualified educators are working in high-poverty schools.

- Urge state policymakers to reevaluate unfair funding practices that negatively impact high-poverty districts.

Recommendations for School Leaders

- Instill a culture of growth and success in your school that effectively educates all students about the opportunities available to them following secondary education.

- Provide benefits and resources within schools to all students so those living in poverty have the necessary supports to succeed, with the assistance of outside partners such as internet providers, food suppliers, or healthcare organizations. Examples include: free breakfast, extended library or lab hours after school, allowing students to take home wifi hotspots, etc.

- Provide professional development for teachers and staff to assist them in working effectively with students in poverty and address the impact of associated trauma and chronic stress.

- Provide students with access to college admissions, scholarships, financial aid information, and personnel to help students with these discussions so students are properly educated on postsecondary education opportunities.

- Ensure that budget discussions and requests are conducted in a transparent process that allows for input from a variets of groups and stakeholders in the school community.

Amerikaner, A., & Morgan, I. (2018, February 27). Funding gaps 2018: An analysis of school funding equity across the U.S. and within each state. Retrieved from https://edtrust.org/resource/funding-gaps-2018/ .

Carey, K., & Harris, E. (2016). It turns out spending more probably does improve education. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/12/nyregion/it-turns-out-spending-more-probably-does-improve-education.html?_r=0 .

Carr, S. (2013, February 26). The real reasons many low-income students don’t go to college. Retrieved from https://hechingerreport.org/the-real-reasons-many-low-income-students-dont-go-to-college/ .

College for America. (2017, June 7). Addressing the college completion gap among low-income students. Retrieved from https://collegeforamerica.org/college-completion-low-income-students/ .

Dynarski, M. (2017, March 1). It’s not nothing: The role of money in improving education. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/its-not-nothing-the-role-of-money-in-improving-education/ .

Garcia, E., & Weiss, E. (2019, March 26). The teacher shortage is real, large and growing, and worse than we thought: The first report in ‘The Perfect Storm in the Teacher Labor Market’ series. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/the-teacher-shortage-is-real-large-and-growing-and-worse-than-we-thought-the-first-report-in-the-perfect-storm-in-the-teacher-labor-market-series/.

Jensen, E. (2013, May). How poverty affects classroom engagement. ASCD. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may13/vol70/num08/How-Poverty-Affects-Classroom-Engagement.aspx .

Johnston, K. (2019, June 20). 7 ways poverty affects education. Retrieved from https://moneywise.com/a/ways-poverty-affects-education .

Jackson, K., Johnson, R., & Persico, C. (2016). The effects of school spending on education and economic outcomes: Evidence from school finance reforms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (1), pp. 157–218.

LaFortune, J., Rothstein, J., & Schanzenbach, D.W. (2016). School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 22011, February 2016.

Martin, C., Boser, U., Benner, M., & Baffour, P. (2018, November 13). A quality approach to school funding. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2018/11/13/460397/quality-approach-school-funding/

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Wang, K., Rathbun, A., Barmer, A., Forrest Cataldi, E., and Bullock Mann, F. (2018). The Condition of Education 2018 (NCES 2018-144). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018144.pdf.

National Association of Secondary School Principals. (2019, March 19). Using PPE data to advocate for your school. School of Thought blog. Retrieved from http://blog.nassp.org/2019/03/22/using-ppe-data-to-advocate-for-your-school/.

Parrett, W., & Budge, K. (2016, January 13). How does poverty influence learning? Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/how-does-poverty-influence-learning-william-parrett-kathleen-budge .

Pascoe, M.C., Hetrick, S.E. & Parker., A.G. (2019). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823 .

Taylor, K. (2019, July 25). Poverty’s long-lasting effects on students’ education and success. Retrieved from https://www.insightintodiversity.com/povertys-long-lasting-effects-on-students-education-and-success/ .

Turner, C., Khrais, R., Lloyd, T., Olgin, A., Isensee, L., Vevea, B., & Carsen, D. (2016, April 18). Why America’s schools have a money problem. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2016/04/18/474256366/why-americas-schools-have-a-money-problem .

- More Networks

Poverty and Education

- Conference: Poverty and Education

- At: Leeds Trinity University

- University of Cambridge

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Edmos Mtetwa

- Watch Ruparanganda

- Hope Amba Neji

- Richard Ekonesi Orim

- Rita Asu Ndifon

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Reducing Poverty Through Education - and How

About the author, idrissa b. mshoro.

There is no strict consensus on a standard definition of poverty that applies to all countries. Some define poverty through the inequality of income distribution, and some through the miserable human conditions associated with it. Irrespective of such differences, poverty is widespread and acute by all standards in sub-Saharan Africa, where gross domestic product (GDP) is below $1,500 per capita purchasing power parity, where more than 40 per cent of their people live on less than $1 a day, and poor health and schooling hold back productivity. According to the 2009 Human Development Report, sub-Saharan Africa's Human Development Index, which measures development by combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income lies in the range of 0.45-0.55, compared to 0.7 and above in other regions of the world. Poverty in sub-Saharan Africa will continue to rise unless the benefits of economic development reach the people. Some sub-Saharan countries have therefore formulated development visions and strategies, identifying respective sources of growth.

Tanzania case study

The Tanzania Development Vision 2025, for example, aims at transforming a low productivity agricultural economy into a semi-industrialized one through medium-term frameworks, the latest being the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP). A review of NSGRP implementation, documented in Tanzania's Poverty and Human Development Report 2009, attributed the falling GDP -- from 7.8 per cent in 2004 to 6.7 per cent in 2006 -- to the prolonged drought during 2005/06. A further fall to 5 per cent was projected by 2009 due to the global financial crisis. While the proportion of households living below the poverty line reduced slightly from 35.7 per cent in 2000 to 33.6 per cent in 2007, the actual number of poor Tanzanians is increasing because the population is growing at a faster rate. The 2009 HDR showed a similar trend whereby the Human Development Index in Tanzania shot up from 0.436 to 0.53 between 1990 and 2007, and in the same year the GDP reached $1,208 per capita purchasing power parity. Again, the improvements, though commendable, are still modest when compared with the goal of NSGRP and Millennium Development Goal 1 to reduce by 50 per cent the number of people whose income is less than $1 a day by 2010 and 2015.

More deliberate efforts are therefore required to redress the situation, with more emphasis placed particularly on education, as most poverty-reduction interventions depend on the availability of human capital for spearheading them. The envisaged economic growth depends on the quantity and quality of inputs, including land, natural resources, labour, and technology. Quality of inputs to a great extent relies on embodied knowledge and skills, which are the basis for innovation, technology development and transfer, and increased productivity and competitiveness.

A quick assessment in June 2010 of education statistics in Tanzania indicated that primary school enrolment increased by 5.8 per cent, from 7,959,884 pupils in 2006 to 8,419,305 in 2010. The Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) was 106.4 per cent. The transition rate from primary to secondary schools, however, decreased by 6.6 per cent from 49.3 per cent in 2005 to 43.9 per cent in 2009. On an annual average, out of 789,739 pupils who completed primary education, only 418,864 continued on to secondary education, notwithstanding the expansion of secondary school enrolment, from 675,672 students in 2006 to 1,638,699 in 2010, a GER increase from 14.8 to 34.0 percent. Moreover, the observed expansion in secondary school education mainly took place from grades one through four, where the number increased from 630,245 in 2006 to 1,566,685 students in 2010. As such, out of 141,527 students who on an annual average completed ordinary secondary education, only 36,014 proceeded to advanced secondary education. Some improvements have also been recorded at the tertiary level. While enrolment in universities was 37,667 students in 2004/05, there were 118,951 in 2009/10.

Adding to this number the students in non-university tertiary institutions totalled 50,173 in 2009/10 and the overall tertiary enrolment reached 169,124 students, providing a GER of 5.3 percent, which is very low.

The observed transition rates imply that, on average, 370,875 primary school children terminate their education journey every year at 13 to 14 years of age in Tanzania. The 17- to 19-year-old secondary school graduates, unable to obtain opportunities for further education, worsen the situation and the overall negative impact on economic growth is very apparent, unless there are other opportunities to develop and empower the secondary school graduates. Vocational education and training could be one such opportunity, but the total current enrolment in vocational education in Tanzania is about 117,000 trainees, which is still far from actual needs. A long-term strategy is therefore critical to expand the capacity for vocational education and training so as to increase the employability of the rising numbers of out-of-school youths. This fact was also apparent in the 2006 Tanzania Integrated Labour Force Survey, which indicated that youth between 15 and 24 years were more likely to be unemployed compared to other age groups because they were entering the labour market for the first time without any skills or work experience. The NSGRP target was to reduce unemployment from 12.9 per cent in 2000/01 to 6.9 per cent by 2010; hence the unemployment rate of 11 per cent in 2006 was disheartening.

One can easily notice that while enrolment in basic education is promising, the situation at other levels remains bleak in meeting poverty reduction targets. Moreover, apart from the noticeably low university enrolment in Tanzania, only 29 per cent of students are taking science and technology courses, probably due to the small catchment pool at lower levels. While this is so, sustainable and broad-based growth requires strengthening of the link between agriculture and industry. Agriculture needs to be modernized for increased productivity and profitability; small and medium enterprises, promoted, with particular emphasis on agro-processing, technology innovation, and upgrading the use of technologies for value addition; and all, with no or minimum negative impact on the environment. Increased investments in human and physical capital are also highly advocated, focusing on efficient and cost-effective provision of infrastructure for energy, information and communication technologies, and transport with special attention to opening up rural and other areas with economic potential. All these point to the promotion of education in science and technology. Special incentives for attracting investments towards accelerating growth are also emphasized. Experience from elsewhere indicates that foreign direct investment contributes effectively to economic growth when the country has a highly-educated workforce. Domestic firms also need to be supported and encouraged to pay attention to product development and innovation for ensuring quality and appropriate marketing strategies that make them competitive and capable of responding to global market conditions.

It is therefore very apparent from the Tanzania example that most of the required interventions for growth and the reduction of poverty require a critical mass of high-quality educated people at different levels to effectively respond to the sustainable development challenges of nations.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Sailors for Sustainability: Sailing the Globe to Document Proven Solutions for Sustainable Living

Most of the solutions we have described are tangible examples of sustainability in action. Yet our sailing journey also made us realize that the most important ingredient for a sustainable future is sustainability from within. By that we mean adopting a different way of perceiving the Earth and our role in it.

What if We Could Put an End to Loss of Precious Lives on the Roads?

Road safety is neither confined to public health nor is it restricted to urban planning. It is a core 2030 Agenda matter. Reaching the objective of preventing at least 50 per cent of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030 would be a significant contribution to every SDG and SDG transition.

Promoting Evidence-Based Prevention Strategies to Mitigate the Harms of Drug Use: The Role of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The engagement of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime with Member States is particularly focused on interventions addressing early adolescence through schools and families by piloting evidence-based, manualized programmes worldwide.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 94 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed.

Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world.

In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022.

However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school.

The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss.

Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems.

Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024

The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives.

Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone.

Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice.

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio.

The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio.

World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank’s Approach to Education

Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars.

Our Principles:

- We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future

Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems.

Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system.

Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels.

The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative.

- Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead

We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth.

Accelerating Improvements

Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals.

Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges.

Universalizing Foundational Literacy

Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects.

The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading.

Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary

Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment.

Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development.

The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems.

Addressing Climate Change

Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks.

Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change.

Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters).

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively.

The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include:

(1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics.

- Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024.

(2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning.

Supporting Successful Teachers

Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers.

Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students.

While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD).

Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability.

Supporting Education Finance Systems

Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education.

Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts.

Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts

The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio.

Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term.

Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle

Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone.

The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021.

In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students.

Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs.

From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school.