The global education challenge: Scaling up to tackle the learning crisis

- Download the policy brief

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alice albright alice albright chief executive officer - global partnership for education.

July 25, 2019

The following is one of eight briefs commissioned for the 16th annual Brookings Blum Roundtable, “2020 and beyond: Maintaining the bipartisan narrative on US global development.”

Addressing today’s massive global education crisis requires some disruption and the development of a new 21st-century aid delivery model built on a strong operational public-private partnership and results-based financing model that rewards political leadership and progress on overcoming priority obstacles to equitable access and learning in least developed countries (LDCs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Success will also require a more efficient and unified global education architecture. More money alone will not fix the problem. Addressing this global challenge requires new champions at the highest level and new approaches.

Key data points

In an era when youth are the fastest-growing segment of the population in many parts of the world, new data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) reveals that an estimated 263 million children and young people are out of school, overwhelmingly in LDCs and LMICs. 1 On current trends, the International Commission on Financing Education Opportunity reported in 2016 that, a far larger number—825 million young people—will not have the basic literacy, numeracy, and digital skills to compete for the jobs of 2030. 2 Absent a significant political and financial investment in their education, beginning with basic education, there is a serious risk that this youth “bulge” will drive instability and constrain economic growth.

Despite progress in gender parity, it will take about 100 years to reach true gender equality at secondary school level in LDCs and LMICs. Lack of education and related employment opportunities in these countries presents national, regional, and global security risks.

Related Books

Amar Bhattacharya, Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

November 15, 2023

Geoffrey Gertz, Homi Kharas, Johannes F. Linn

September 12, 2017

Esther Care, Patrick Griffin

April 11, 2017

Among global education’s most urgent challenges is a severe lack of trained teachers, particularly female teachers. An additional 9 million trained teachers are needed in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030.

Refugees and internally displaced people, now numbering over 70 million, constitute a global crisis. Two-thirds of the people in this group are women and children; host countries, many fragile themselves, struggle to provide access to education to such people.

Highlighted below are actions and reforms that could lead the way toward solving the crisis:

- Leadership to jump-start transformation. The next U.S. administration should convene a high-level White House conference of sovereign donors, developing country leaders, key multilateral organizations, private sector and major philanthropists/foundations, and civil society to jump-start and energize a new, 10-year global response to this challenge. A key goal of this decadelong effort should be to transform education systems in the world’s poorest countries, particularly for girls and women, within a generation. That implies advancing much faster than the 100-plus years required if current programs and commitments remain as is.

- A whole-of-government leadership response. Such transformation of currently weak education systems in scores of countries over a generation will require sustained top-level political leadership, accompanied by substantial new donor and developing country investments. To ensure sustained attention for this initiative over multiple years, the U.S. administration will need to designate senior officials in the State Department, USAID, the National Security Council, the Office of Management and Budget, and elsewhere to form a whole-of-government leadership response that can energize other governments and actors.

- Teacher training and deployment at scale. A key component of a new global highest-level effort, based on securing progress against the Sustainable Development Goals and the Addis 2030 Framework, should be the training and deployment of 9 million new qualified teachers, particularly female teachers, in sub-Saharan Africa where they are most needed. Over 90 percent of the Global Partnership for Education’s education sector implementation grants have included investments in teacher development and training and 76 percent in the provision of learning materials.

- Foster positive disruption by engaging community level non-state actors who are providing education services in marginal areas where national systems do not reach the population. Related to this, increased financial and technical support to national governments are required to strengthen their non-state actor regulatory frameworks. Such frameworks must ensure that any non-state actors operate without discrimination and prioritize access for the most marginalized. The ideological divide on this issue—featuring a strong resistance by defenders of public education to tap into the capacities and networks of non-state actors—must be resolved if we are to achieve a rapid breakthrough.

- Confirm the appropriate roles for technology in equitably advancing access and quality of education, including in the initial and ongoing training of teachers and administrators, delivery of distance education to marginalized communities and assessment of learning, strengthening of basic systems, and increased efficiency of systems. This is not primarily about how various gadgets can help advance education goals.

- Commodity component. Availability of appropriate learning materials for every child sitting in a classroom—right level, right language, and right subject matter. Lack of books and other learning materials is a persistent problem throughout education systems—from early grades through to teaching colleges. Teachers need books and other materials to do their jobs. Consider how the USAID-hosted Global Book Alliance, working to address costs and supply chain issues, distribution challenges, and more can be strengthened and supported to produce the model(s) that can overcome these challenges.

Annual high-level stock take at the G-7. The next U.S. administration can work with G-7 partners to secure agreement on an annual stocktaking of progress against this new global education agenda at the upcoming G-7 summits. This also will help ensure sustained focus and pressure to deliver especially on equity and inclusion. Global Partnership for Education’s participation at the G-7 Gender Equality Advisory Council is helping ensure that momentum is maintained to mobilize the necessary political leadership and expertise at country level to rapidly step up progress in gender equality, in and through education. 3 Also consider a role for the G-20, given participation by some developing country partners.

Related Content

Jenny Perlman Robinson, Molly Curtiss Wyss

July 3, 2018

Michelle Kaffenberger

May 17, 2019

Ramya Vivekanandan

February 14, 2019

- “263 Million Children and Youth Are Out of School.” UNESCO UIS. July 15, 2016. http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school.

- “The Learning Generation: Investing in education for a changing world.” The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. 2016. https://report.educationcommission.org/downloads/.

- “Influencing the most powerful nations to invest in the power of girls.” Global Partnership for Education. March 12, 2019. https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/influencing-most-powerful-nations-invest-power-girls.

Global Education

Global Economy and Development

Christine Apiot Okudi, Atenea Rosado-Viurques, Jennifer L. O’Donoghue

August 23, 2024

Sudha Ghimire

August 22, 2024

Online only

11:00 am - 12:00 pm EDT

The Education Crisis: Being in School Is Not the Same as Learning

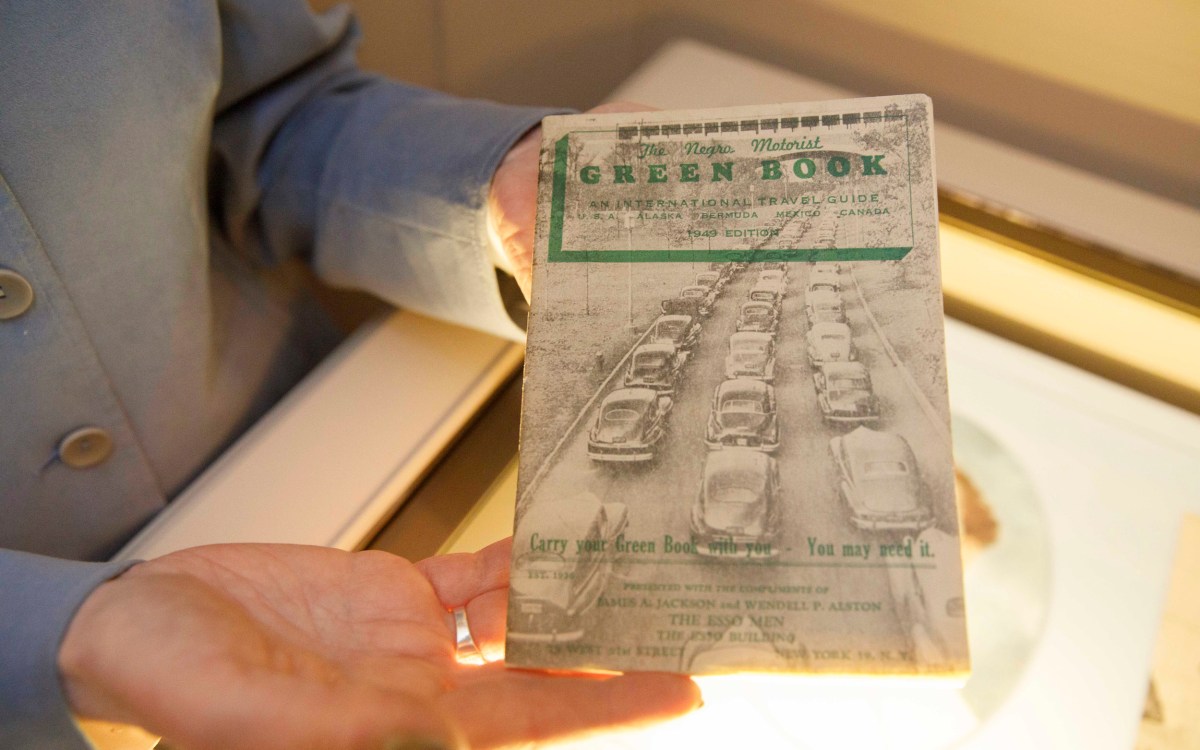

First grade students in Pakistan’s Balochistan Province are learning the alphabet through child-friendly flash cards. Their learning materials help educators teach through interactive and engaging activities and are provided free of charge through a student’s first learning backpack. © World Bank

THE NAME OF THE DOG IS PUPPY. This seems like a simple sentence. But did you know that in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, three out of four third grade students do not understand it? The world is facing a learning crisis . Worldwide, hundreds of millions of children reach young adulthood without even the most basic skills like calculating the correct change from a transaction, reading a doctor’s instructions, or understanding a bus schedule—let alone building a fulfilling career or educating their children. Education is at the center of building human capital. The latest World Bank research shows that the productivity of 56 percent of the world’s children will be less than half of what it could be if they enjoyed complete education and full health. For individuals, education raises self-esteem and furthers opportunities for employment and earnings. And for a country, it helps strengthen institutions within societies, drives long-term economic growth, reduces poverty, and spurs innovation.

One of the most interesting, large scale educational technology efforts is being led by EkStep , a philanthropic effort in India. EkStep created an open digital infrastructure which provides access to learning opportunities for 200 million children, as well as professional development opportunities for 12 million teachers and 4.5 million school leaders. Both teachers and children are accessing content which ranges from teaching materials, explanatory videos, interactive content, stories, practice worksheets, and formative assessments. By monitoring which content is used most frequently—and most beneficially—informed decisions can be made around future content.

In the Dominican Republic, a World Bank supported pilot study shows how adaptive technologies can generate great interest among 21st century students and present a path to supporting the learning and teaching of future generations. Yudeisy, a sixth grader participating in the study, says that what she likes doing the most during the day is watching videos and tutorials on her computer and cell phone. Taking childhood curiosity as a starting point, the study aimed to channel it towards math learning in a way that interests Yudeisy and her classmates.

Yudeisy, along with her classmates in a public elementary school in Santo Domingo, is part of a four-month pilot to reinforce mathematics using software that adapts to the math level of each student. © World Bank

Adaptive technology was used to evaluate students’ initial learning level to then walk them through math exercises in a dynamic, personalized way, based on artificial intelligence and what the student is ready to learn. After three months, students with the lowest initial performance achieved substantial improvements. This shows the potential of technology to increase learning outcomes, especially among students lagging behind their peers. In a field that is developing at dizzying speeds, innovative solutions to educational challenges are springing up everywhere. Our challenge is to make technology a driver of equity and inclusion and not a source of greater inequality of opportunity. We are working with partners worldwide to support the effective and appropriate use of educational technologies to strengthen learning.

When schools and educations systems are managed well, learning happens

Successful education reforms require good policy design, strong political commitment, and effective implementation capacity . Of course, this is extremely challenging. Many countries struggle to make efficient use of resources and very often increased education spending does not translate into more learning and improved human capital. Overcoming such challenges involves working at all levels of the system.

At the central level, ministries of education need to attract the best experts to design and implement evidence-based and country-specific programs. District or regional offices need the capacity and the tools to monitor learning and support schools. At the school level, principals need to be trained and prepared to manage and lead schools, from planning the use of resources to supervising and nurturing their teachers. However difficult, change is possible. Supported by the World Bank, public schools across Punjab in Pakistan have been part of major reforms over the past few years to address these challenges. Through improved school-level accountability by monitoring and limiting teacher and student absenteeism, and the introduction of a merit-based teacher recruitment system, where only the most talented and motivated teachers were selected, they were able to increase enrollment and retention of students and significantly improve the quality of education. "The government schools have become very good now, even better than private ones," said Mr. Ahmed, a local villager.

The World Bank, along with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the UK’s Department for International Development, is developing the Global Education Policy Dashboard . This new initiative will provide governments with a system for monitoring how their education systems are functioning, from learning data to policy plans, so they are better able to make timely and evidence-based decisions.

Education reform: The long game is worth it

In fact, it will take a generation to realize the full benefits of high-quality teachers, the effective use of technology, improved management of education systems, and engaged and prepared learners. However, global experience shows us that countries that have rapidly accelerated development and prosperity all share the common characteristic of taking education seriously and investing appropriately. As we mark the first-ever International Day of Education on January 24, we must do all we can to equip our youth with the skills to keep learning, adapt to changing realities, and thrive in an increasingly competitive global economy and a rapidly changing world of work.

The schools of the future are being built today. These are schools where all teachers have the right competencies and motivation, where technology empowers them to deliver quality learning, and where all students learn fundamental skills, including socio-emotional, and digital skills. These schools are safe and affordable to everyone and are places where children and young people learn with joy, rigor, and purpose. Governments, teachers, parents, and the international community must do their homework to realize the promise of education for all students, in every village, in every city, and in every country.

The Bigger Picture: In-depth stories on ending poverty

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

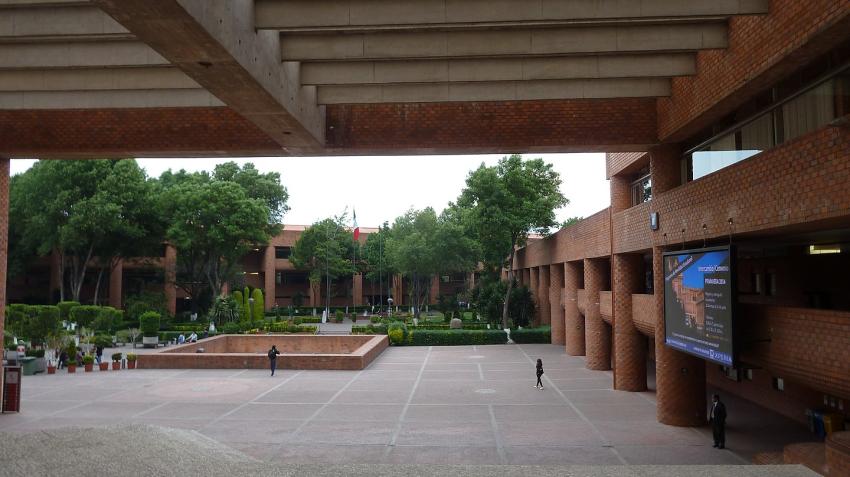

Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education

About the author, sylvia schmelkes.

Sylvia Schmelkes is Provost of the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

22 January 2020 Introduction

I nequity is perhaps the most serious problem in education worldwide. It has multiple causes, and its consequences include differences in access to schooling, retention and, more importantly, learning. Globally, these differences correlate with the level of development of various countries and regions. In individual States, access to school is tied to, among other things, students' overall well-being, their social origins and cultural backgrounds, the language their families speak, whether or not they work outside of the home and, in some countries, their sex. Although the world has made progress in both absolute and relative numbers of enrolled students, the differences between the richest and the poorest, as well as those living in rural and urban areas, have not diminished. 1

These correlations do not occur naturally. They are the result of the lack of policies that consider equity in education as a principal vehicle for achieving more just societies. The pandemic has exacerbated these differences mainly due to the fact that technology, which is the means of access to distance schooling, presents one more layer of inequality, among many others.

The dimension of educational inequity

Around the world, 258 million, or 17 per cent of the world’s children, adolescents and youth, are out of school. The proportion is much larger in developing countries: 31 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa and 21 per cent in Central Asia, vs. 3 per cent in Europe and North America. 2 Learning, which is the purpose of schooling, fares even worse. For example, it would take 15-year-old Brazilian students 75 years, at their current rate of improvement, to reach wealthier countries’ average scores in math, and more than 260 years in reading. 3 Within countries, learning results, as measured through standardized tests, are almost always much lower for those living in poverty. In Mexico, for example, 80 per cent of indigenous children at the end of primary school don’t achieve basic levels in reading and math, scoring far below the average for primary school students. 4

The causes of educational inequity

There are many explanations for educational inequity. In my view, the most important ones are the following:

- Equity and equality are not the same thing. Equality means providing the same resources to everyone. Equity signifies giving more to those most in need. Countries with greater inequity in education results are also those in which governments distribute resources according to the political pressure they experience in providing education. Such pressures come from families in which the parents attended school, that reside in urban areas, belong to cultural majorities and who have a clear appreciation of the benefits of education. Much less pressure comes from rural areas and indigenous populations, or from impoverished urban areas. In these countries, fewer resources, including infrastructure, equipment, teachers, supervision and funding, are allocated to the disadvantaged, the poor and cultural minorities.

- Teachers are key agents for learning. Their training is crucial. When insufficient priority is given to either initial or in-service teacher training, or to both, one can expect learning deficits. Teachers in poorer areas tend to have less training and to receive less in-service support.

- Most countries are very diverse. When a curriculum is overloaded and is the same for everyone, some students, generally those from rural areas, cultural minorities or living in poverty find little meaning in what is taught. When the language of instruction is different from their native tongue, students learn much less and drop out of school earlier.

- Disadvantaged students frequently encounter unfriendly or overtly offensive attitudes from both teachers and classmates. Such attitudes are derived from prejudices, stereotypes, outright racism and sexism. Students in hostile environments are affected in their disposition to learn, and many drop out early.

It doesn’t have to be like this

When left to inertial decision-making, education systems seem to be doomed to reproduce social and economic inequity. The commitment of both governments and societies to equity in education is both necessary and possible. There are several examples of more equitable educational systems in the world, and there are many subnational examples of successful policies fostering equity in education.

Why is equity in education important?

Education is a basic human right. More than that, it is an enabling right in the sense that, when respected, allows for the fulfillment of other human rights. Education has proven to affect general well-being, productivity, social capital, responsible citizenship and sustainable behaviour. Its equitable distribution allows for the creation of permeable societies and equity. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Sustainable Development Goal 4, which aims to ensure “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. One hundred eighty-four countries are committed to achieving this goal over the next decade. 5 The process of walking this road together has begun and requires impetus to continue, especially now that we must face the devastating consequences of a long-lasting pandemic. Further progress is crucial for humanity.

Notes 1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , Inclusive Education. All Means All , Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 (Paris, 2020), p.8. Available at https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2020/inclusion . 2 Ibid., p. 4, 7. 3 World Bank Group, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise (Washington, DC, 2018), p. 3. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018 . 4 Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, "La educación obligatoria en México", Informe 2018 (Ciudad de México, 2018), p. 72. Available online at https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/P1I243.pdf . 5 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , “Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4” (2015), p. 23. Available at https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Voices for Peace: The Crucial Role of Victims of Terrorism as Peace Advocates and Educators

In the face of unimaginable pain and trauma, victims and survivors of terrorism emerge as strong advocates for community resilience, solidarity and peaceful coexistence.

Sailors for Sustainability: Sailing the Globe to Document Proven Solutions for Sustainable Living

Most of the solutions we have described are tangible examples of sustainability in action. Yet our sailing journey also made us realize that the most important ingredient for a sustainable future is sustainability from within. By that we mean adopting a different way of perceiving the Earth and our role in it.

What if We Could Put an End to Loss of Precious Lives on the Roads?

Road safety is neither confined to public health nor is it restricted to urban planning. It is a core 2030 Agenda matter. Reaching the objective of preventing at least 50 per cent of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030 would be a significant contribution to every SDG and SDG transition.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

Educational challenges and opportunities of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

Jaime saavedra.

We are living amidst what is potentially one of the greatest threats in our lifetime to global education, a gigantic educational crisis. As of March 28, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing more than 1.6 billion children and youth to be out of school in 161 countries. This is close to 80% of the world’s enrolled students. We were already experiencing a global leaning crisis, as many students were in school, but were not learning the fundamental skills needed for life. The World Bank’s “ Learning Poverty ” indicator – the % of children who cannot read and understand at age 10 – stood at 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries – before the outbreak started. This pandemic has the potential to worsen these outcomes even more if we do not act fast.

What should we be worried about in this phase of the crisis that might have an immediate impact on children and youth? (1) Losses in learning (2) Increased dropout rates (3) Children missing their most important meal of the day. Moreover, most countries have very unequal education systems, and these negative impacts will be felt disproportionately by poor children. When it rains, it pours for them.

Learning . Starting the school year late or interrupting it (depending on if they live in the southern or northern hemisphere) completely disrupts the lives of many children, their parents, and teachers. A lot can be done to at least reduce the impact through remote learning strategies. Richer countries are better prepared to move to online learning strategies, although with a lot of effort and challenges for teachers and parents. In middle-income and poorer countries, the situation is very mixed and if we do not act appropriately, the vast inequality of opportunities that exists – egregious and unacceptable to start with – will be amplified. Many children do not have a desk, books, internet connectivity, a laptop at home, or supportive parents. Others do. What we need to avoid – or minimize as much as possible – is for those differences in opportunities to expand and cause the crisis to have an even larger negative effect on poor children’s learning.

Fortunately, we are seeing a lot of creativity in many countries. Rightly so, many ministries of education are worried that relying exclusively on online strategies will imply reaching only children from better-off families. The appropriate strategy in most countries is to use all possible delivery modes with the infrastructure that exists today. Use online tools to assure that lesson plans, videos, tutorials, and other resources are available for some students and probably, most teachers. But also, podcasts and other resources that require less data usage. Working with telecommunication companies to apply zero-rate policies can also facilitate learning material to be downloaded on a smartphone, which more students are likely to have.

Radio and TV are also very powerful tools. The advantage we have today, is that through social networks, WhatsApp or SMS, ministries of education can communicate effectively with parents and teachers and provide guidelines, instructions and structure to the learning process, using content delivered by radio or TV. Remote learning is not only about online learning, but about mixed media learning, with the objective of reaching as many students as possible, today.

Staying engaged. Maintaining the engagement of children, particularly young secondary school students is critical. Dropout rates are still very high in many countries, and a long period of disengagement can result in a further increase. Going to school is not only about learning math and science, but also about social relationships and peer-to-peer interactions. It is about learning to be a citizen and developing social skills. That is why it is important to stay connected with the school by any means necessary. For all students, this is also a time to develop socio-emotional skills and learn more about how to contribute to society as a citizen. The role of parents and family, which has always been extremely important, is critical in that task. So, a lot of the help that ministries of education provide, working through mass media, should also go to parents. Radio, TV, SMS messages can all be used to provide tips and advice to them on how to better support their children.

Meals. In many parts of the world, school feeding programs provide children with their most nutritious meal of the day. They are essential for the cognitive development and well-being. These programs are complex logistical and administrative endeavors. It is not easy, but countries should find the way to provide those meals using the school buildings in an organized fashion, community buildings or networks, or, if needed, distribute directly to the families. If delivering meals or food is not feasible logistically, cash transfer programs should be expanded or implemented to compensate the parents. Planning is needed, but one has to be ready to flexibly adjust plans, as the information we have about the likely paths of the pandemic change day by day, influenced by the uncertainty around which mitigation measures countries are taking. The process of reopening of schools might be gradual, as authorities will want to reduce agglomeration or the possibility of a second wave of the pandemic, which can affect some countries. In that uncertain context, it might be better to make decisions assuming a longer, rather than a shorter scenario. The good news is that many of the improvements, initiatives, and investments that school systems will have to make might have a positive long-lasting effect.

Some countries will be able to increase their teachers’ digital skills. Radio and TV stations will recognize their key role in supporting national education goals – and hopefully, improve the quality of their programming understanding their immense social responsibility. Parents will be more involved in their children’s education process, and ministries of education will have a much clearer understanding of the gaps and challenges (in connectivity, hardware, integration of digital tools in the curriculum, teacher’s readiness) that exist in using technology effectively and act upon that. All of this can strengthen the future education system in a country.

The mission of all education systems is the same. It is to overcome the learning crisis we were already living and respond to the pandemic we are all facing. The challenge today is to reduce as much as possible the negative impact this pandemic will have on learning and schooling and build on this experience to get back on a path of faster improvement in learning. As education systems cope with this crisis, they must also be thinking of how they can recover stronger, with a renewed sense of responsibility of all actors and with a better understanding and sense of urgency of the need to close the gap in opportunities and assuring that all children have the same chances for a quality education.

- The World Region

- COVID-19 (coronavirus)

Get updates from Education for Global Development

Thank you for choosing to be part of the Education for Global Development community!

Your subscription is now active. The latest blog posts and blog-related announcements will be delivered directly to your email inbox. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Human Development Director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About How to Improve American Education

An international exam shows that American 15-year-olds are stagnant in reading and math. Teenagers told us what’s working and what’s not in the American education system.

By The Learning Network

Earlier this month, the Program for International Student Assessment announced that the performance of American teenagers in reading and math has been stagnant since 2000 . Other recent studies revealed that two-thirds of American children were not proficient readers , and that the achievement gap in reading between high and low performers is widening.

We asked students to weigh in on these findings and to tell us their suggestions for how they would improve the American education system.

Our prompt received nearly 300 comments. This was clearly a subject that many teenagers were passionate about. They offered a variety of suggestions on how they felt schools could be improved to better teach and prepare students for life after graduation.

While we usually highlight three of our most popular writing prompts in our Current Events Conversation , this week we are only rounding up comments for this one prompt so we can honor the many students who wrote in.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Your kid can’t name three branches of government? He’s not alone.

‘We have the most motivated people, the best athletes. How far can we take this?’

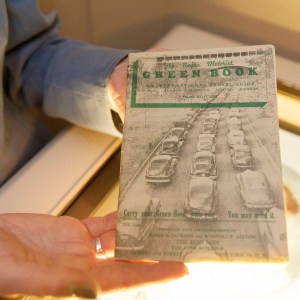

Harvard Library acquires copy of ‘Green Book’

Bridget Long, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, addresses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in the field of education.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Post-pandemic challenges for schools

Harvard Staff Writer

Ed School dean says flexibility, more hours key to avoid learning loss

With the closing of schools, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many of the injustices facing schoolchildren across the country, from inadequate internet access to housing instability to food insecurity. The Gazette interviewed Bridget Long, A.M. ’97, Ph.D. ’00, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Saris Professor of Education and Economics, regarding her views on the impact the public health crisis has had on schools, the lessons learned from the pandemic, and the challenges ahead.

Bridget Long

GAZETTE: The pandemic exposed many inequities that already existed in the education landscape. Which ones concern you the most?

LONG: Persistent inequities in education have always been a concern, but with the speed and magnitude of the changes brought on by the pandemic, it underscored several major problems. First of all, we often think about education as being solely an academic enterprise, but our schools really do so much more. Immediately, we saw children and families struggling with basic needs, such as access to food and health care, which our schools provide but all of a sudden were removed. We also shifted our focus, once we had to be in lockdown, to the differences in students’ home environments, whether it was lack of access to technology and the other commitments and demands on their time in terms of family situations, space, basic needs, and so forth. The focus had to shift from leveling the playing field within school or within college to instead what are the differences in inequities inside students’ homes and neighborhoods and the differences in the quality and rigor and supports available to students of different backgrounds. All of this was just exacerbated with the pandemic. There are concerns about learning loss and how that will vary across different income groups, communities, and neighborhoods. But there are also concerns about trauma and the mental health strain of the pandemic and how the strain of racial injustice and political turmoil has also been experienced — no doubt differently by different parts of population. And all of that has impacted students’ well-being and academic performance. The inequities we have long seen have become worse this year.

GAZETTE: Now that those inequities have been exposed, what can leaders in education do to navigate those issues? Are there any specific lessons learned?

LONG: Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet. The solution depends on the individual, the community, and the classroom.

At first, the public health crisis underscored that we needed to meet students where they are. This has been a long-held lesson among experienced education professionals, but it became even more important. In many respects, it butted up against some of our systems, which tried to come up with across-the-board approaches when instead what we needed was a bit of nimbleness depending on the context of the particular school or classroom and the individual needs of students.

Where you have seen some success and progress is where principals and teachers have been proactive and creative in how they can meet the needs of their students. What’s underneath all of this, regardless of whether we’re face-to-face or on technology, is the importance of people and personal connections. Education is a labor-intensive industry. Technology can help us in many respects to supplement or complement what we do, but the key has always been individual personal connection. Some teachers have been able to connect with their students, whether by phone or on Zoom, or schools, where they put concerted effort into doing outreach in the community to check on families to make sure they had basic needs. Some schools were able to understand what challenges their students were facing and were somewhat flexible and proactive to address those challenges, especially if they already had strong parental engagement. That’s where you have continued to see progress and growth.

“In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before.”

GAZETTE: You spoke about concerns about learning loss. What can we do to avoid a lost year?

LONG: One of the difficulties is that the experience has differed tremendously. For some students, their parents have been able to supplement or their schools have been able to react. The hope is that they will not lose much learning time, while other students effectively haven’t been in school for almost a year; they have lost quite a bit of ground. As a teacher, you can imagine your students come back to school, and all of a sudden, students of the same chronological age are actually in very different places, depending on their individual family situation and what accommodations were able to be made. I think there’s a great deal we can do to try to address that. First of all, we have to have some understanding of what gains students have made as well as things they haven’t learned yet. That means taking a moment to see where a student is in their learning. The second thing is to make sure we’re capturing the lessons learned from this pandemic by identifying places where teachers and schools used a combination of technology, outreach, personal instruction, and tutors and mentors, and helped students make progress in their learning. We need to share those lessons more broadly so that other districts can see examples that have worked.

As we look ahead, I think it will take extending learning time to close the gaps. Schools will have to decide whether that is after school, weekends, or summer, and whether or not that’s going to involve the teachers themselves, or if it’s going to be using the best tools that are out there, such as videos and technology platforms that students and families use themselves. There has already been talk by some districts of extending the school year into summer or having summer-camp-type programs to give students additional time to work through some of the material.

The other important piece is partnerships. Schools oftentimes work with members of the community or nonprofit organizations, and that’s a really important layer in our system. After-school programs, enrichment programs, tutors, and mentors are essential, and we really want to continue with that expanded sense of capacity and partnership. It’s going to have an impact on all of us if we lose a generation, or if this generation goes backwards in terms of their learning. It certainly is in all of our best interests to try to contribute to the solution.

GAZETTE: Many parents gained renewed appreciation of the work teachers do. Do you think the pandemic would lead to a reappraisal of the profession?

LONG: Certainly, in the beginning, there was so much more appreciation for what teachers do. As parents needed to start doing homeschooling, there was a new understanding of just how difficult teaching is. Imagine having a classroom with different personalities, different strengths and assets, and also different weaknesses, and somehow being nimble enough to continue that class moving forward. As time has gone on, I worry a little bit about the level of contentiousness in some communities as schools haven’t reopened. There is the balancing act between caring for children’s learning and the fact that we have to make sure that the adults are safe and supported. You hear stories of teachers trying to teach from home while they are also homeschooling their own children. I would hope that coming out of this would be an appreciation of the amazing things teachers do in the classroom, as well as also some acknowledgement that these are people who are also living through a devastating pandemic with all the stress and strain that every individual is going through.

One other point is that given that we know that teachers do more than just academics, we need to make sure our teachers are trained to be able to provide social emotional support to students. As some of the students come back into the classroom, we need to acknowledge that they may be dealing with devastating losses, or the frustration of being kept inside, or the violence that is happening in their homes and neighborhoods. It’s very hard to learn if you’re first dealing with those kinds of issues. Our teachers already do so much, and we need to support them more and provide even more training to help them address that wide-ranging set of challenges their students may be facing even before they can get to the learning part.

“Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet.”

GAZETTE: Are there any silver linings in education brought on by the pandemic?

LONG: The first one is when we all needed to pivot last spring, and especially this fall, many educators took a moment to pause and reflect on their learning goals and priorities. There was a great deal of discussion, both in K‒12 and higher education, to think carefully and deliberately about the ways in which we could make sure our teaching was engaging and active and how we could bring in different voices and perspectives. In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before. The second silver lining is the innovation and creativity. Because there wasn’t necessarily one right answer, you saw a lot of experimentation. We have seen an explosion of different approaches to teaching, and many more people got involved in that process, not just some small 10 percent of the teaching force. We’ve identified new ways of engaging with our students, and we’ve also increased the capacity of our educators to be able to deliver new ways of engagement. From this process, my hope is that we’ll walk away with even more tools and approaches to how we engage our students, so that we can then make choices about what to do face-to-face, how to use technology, and what to do in more of an asynchronous sort of way. But key to this is being able to share those lessons learned with others, how you were able to still maintain connection, how you were better able to teach certain material, and perhaps even build better relationships with parents and families during this process. Just the innovation, experimentation, and growth of instructors in many places has been very positive in so many respects.

GAZETTE: In which ways do you think the education system should be transformed after this year? How should it be rebuilt?

LONG: First, we’ve all had to understand that education and schools are not a spot on a map. They are actually communities; they have to include families, nonprofit organizations, and community-based organizations. For a university in particular, it’s not just about coming to campus; it’s actually about the people coming together, and how they are involved in learning from each other. It’s great to push on this reconceptualization and to be clear that education is an exchange of information, of perspective, of content, and making connections, regardless of the age of the student. The crisis has also forced us to go back to some of the fundamentals of what do we need students to learn, and how are we going to accomplish those goals. That has been a very important discussion for education. And the third part is realizing that education is not a one-size-fits-all. The best educators use multiple methods and approaches to be able to connect with their students, to be able to present material, and to provide support. That’s always been the case. How do we meet students where they are? That framing is one that I hope will not go away because all students have the potential to learn, and it’s a matter of how to personalize the learning experience to meet their needs, how we notice and provide supports to help learners who are struggling. That really is at the core of education, and I hope that we will take away that lesson as we look ahead.

GAZETTE: What do you think the role of higher education should be in this new educational landscape?

LONG: Higher education has an incredibly important role, and in particular given the economic recession. Traditionally, this is when many more people go into higher education to learn new skills, given what’s happening in the labor market. We have yet to see what the long-term impact is going to be, but in the short term, one thing we’ve noticed is that college enrollments are down. That’s very alarming and may have to do with how suddenly and how quickly the pandemic affected society. The first thing that higher education is going to have to think about is increasing proactive outreach — how to connect with potential students and how to help them get into programs that are going to give them skills necessary for this changing economy. Unfortunately, they’ll be doing this in a context where students are going to have greater needs, and where it’s not quite clear if funding from state and local governments is going to be declining. That’s the challenge that higher education will have to face. While it’s an amazing instrument in helping individuals further their skills or retool their skills, we need to make investments and make sure individuals can actually access the training available in our colleges and universities.

More like this

With revamped master’s program, School of Education faces fresh challenges

Seeded amid the many surprises of COVID times, some unexpected positives

Dental students fill the gap in online learning

GAZETTE: What are your hopes for the Biden administration in the area of education?

LONG: Government has a very important role in education, but it has to be balanced with the importance of local control and the fact that the context of every community is slightly different. Certainly, as we’ve been in the middle of a public health crisis, this has been incredibly challenging for schools. Schools had been trying to continue providing food and health care and connect with their students and, all of a sudden, they had to become experts in public health and buildings. This is something that falls under the purview of the federal government. Having access to the best doctors, the best public health officials, and people who think about buildings, and how to make things safe, the government needs to put that information together to give guidance to schools, principals, and teachers. It’s the government that can say, “Here are the risks, and here are the things you can do to mitigate those risks. Here are the conditions that are necessary for buildings. Here is what we know in terms of preventing spread, and here is what we know about the impact on children of different ages, and how we can protect the adults.” That kind of guidance would be incredibly helpful, as you have all of these individual school districts trying to sort through complex information and what the science says and how it applies to their particular context. Guidance is No. 1.

No. 2 is data. It’s very important having some understanding about where we stand in terms of learning loss, what we need to prioritize, and what areas of the country perhaps need more help than others. The other key component is to gauge what lessons have been learned and share the best practices across all school districts. The idea is to use the federal government as a central information bank with proactive outreach to schools. Government also plays a critical role in funding the research that will document the lessons from this pandemic.

It’s going to be incredibly helpful to have a more active federal government. As we have a better sense about where our students are the most vulnerable, and what are the kinds of high-impact practices that would be most beneficial, it’s going to be critical having the funding to support those kinds of investments because they will most certainly pay off. That possibility, I’m much more optimistic about now.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity

Share this article

You might like.

Efforts launched to turn around plummeting student scores in U.S. history, civics, amid declining citizen engagement across nation

Six members of Team USA train at Newell Boat House for 2024 Paralympics in Paris

Rare original copy of Jim Crow-era travel guide ‘key document in Black history’

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Examining new weight-loss drugs, pediatric bariatric patients

Researcher says study found variation in practices, discusses safety concerns overall for younger users

Shingles may increase risk of cognitive decline

Availability of vaccine offers opportunity to reduce burden of shingles and possible dementia

- Our Mission

Using an Inquiry Process to Solve Persistent Classroom Problems

Teachers can resolve challenges that come up over and over by using data to keep testing strategies until they find what works.

The start of a new school year is always filled with anticipation. Teachers hope for engaged students who want to attain success. Students set personal goals and often hope that this year will be better than last year. Parents want their children to try hard, do well, and they want their children’s teachers to be supportive and offer a safe learning space. The new school year is often filled with hope.

However, despite all the best intentions, at some point, the teacher will encounter a problem. Many problems can be resolved with the knowledge acquired through a teacher’s experience. Students may forget to bring a pencil to class, so you just keep a jar of sharpened pencils on your desk. Students who are English language learners struggle to read Shakespeare, so you provide them and all the other students with a link to the audio version of the play that they can listen to. These impromptu decisions have the potential to swiftly address the problem, thereby eliminating the need for further investigation.

What is Teacher Inquiry?

But what is a teacher supposed to do if a problem persists over time? Some students are always late to class right after lunch. Some students never raise their hand to participate in a class discussion. Some students don’t effectively edit their work prior to handing it in. How can a teacher work to identify strategies that can solve these persistent classroom problems? This is where teacher inquiry becomes a valuable tool.

As Marilyn Cochran-Smith and Susan L. Lytle discuss in their book Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation , teacher inquiry is a process of questioning, exploring, and implementing strategies to address persistent classroom challenges. It mirrors the active learning process we encourage in students and can transform recurring problems into opportunities for growth. Most important, it also creates space for students to share their voices and perspectives—allowing them to play a role in guiding the changes that are implemented in the classroom.

How to Start the Inquiry Process

Identify the problem. Begin by clearly defining the issue. For example, if students are frequently late after lunch, consider this as your inquiry focus.

Gather action information. Before rushing to solutions, gather insights from blogs, research, books, or colleagues. For instance, if the problem is tardiness, you might explore strategies like greeting students at the door or starting the class with a high-energy, collaborative activity that is engaging for students .

Frame your inquiry question. Craft a focused question using the format: What impact does X have on Y? Here X is the planned intervention, and Y is the behavior.

- What impact does greeting students at the classroom door have on their punctuality?

- What impact does a sharing circle have on students’ presentation anxiety?

This approach shifts the perspective from seeing students as the problem to exploring solutions to unwanted behaviors. Rather than saying, “Students are always late to class right after lunch,” we can ask, “What impact does an engaging collaborative activity at the start of class have on students’ punctuality?”

Implementing and Assessing the Strategy

Plan data collection. Before implementing your strategy, decide how you’ll measure its effectiveness. This could involve the following:

Quantitative data: Use attendance records, test scores, or quick surveys—whether digital or paper-based—to track student engagement. For example, monitor the number of students arriving on time before and after you start greeting them. Choose the survey method that best fits your classroom’s needs, whether it’s a digital link or QR code for students with technology, or a paper survey for those without.

Qualitative data: Collect student feedback through informal interviews or reflective journals to understand their experiences.

Mixed methods: You can collect a combination of quantitative and qualitative data to allow for quick, easy-to-read facts (quantitative) with an understanding of the why (qualitative) for the data.

Tip: To avoid overwhelming yourself, use data that you’re already collecting and analyze it with your inquiry question in mind.

Implement the strategy. Start with a small, manageable change. If you’re trying to improve punctuality, greet students at the door for a week and note any changes.

Evaluating the Results

Analyze the data . Review your collected data to see if there’s a noticeable effect. Did more students arrive on time? If you used a survey, what do the results indicate about students’ attitudes?

Reflect on the outcome. If the strategy worked, consider how it can be sustained or adapted for other challenges. If it didn’t, reflect on why. Did the strategy need more time, or should a different approach be tried?

Example: If greeting students didn’t improve punctuality, consider if greeting needs to be combined with another intervention, like a change in seating arrangements or communicating with students’ families to remind them about the importance of punctuality.

What if the Strategy Doesn’t Work?

Not all inquiries lead to success, and that’s OK. If your initial strategy doesn’t yield the desired results, reflect on the process.

- What could be adjusted? Perhaps the data collection method wasn’t effective, or the strategy needs more time to show results.

- What did you learn? Even if the strategy didn’t solve the problem, what insights did you gain that could inform future inquiries?

Adopt the same growth mindset you encourage in your students in order to view setbacks as learning opportunities . Inquiry is a cycle of continuous improvement, not a onetime fix.

Embracing the Inquiry Mindset

Inquiry empowers teachers to approach challenges with curiosity and adaptability. By framing problems as opportunities to learn, gathering and analyzing data, and reflecting on outcomes, teachers model the persistence and growth mindset we aim to instill in our students. Even when results aren’t immediate, the process fosters a culture of continuous learning and improvement, benefiting teachers and students alike.

Asian Development Blog Straight Talk from Development Experts

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Education is in Crisis: How Can Technology be Part of the Solution?

By Paul Vandenberg , Kirsty Newman , Milan Thomas

Digital technologies and EdTech could play a role in addressing the learning crisis underway in Asia and the Pacific.

A learning crisis affects many developing countries in Asia. Millions of children attend school but are not learning enough. They cannot read, write, or do mathematics at their grade level, and yet they pass to the next grade, learning even less because they have not grasped the previous material. The magnitude of the crisis is staggering: in low- and middle-income countries more than half of children are not learning to read by age 10.

At the same time, there is an emerging revolution in learning brought on by digital technologies . These are collectively referred to as educational technology or EdTech . The coincident emergence of a problem in education and a new approach to learning naturally makes us ask how one may be a solution for the other.

Edtech may be one part of the solution – but it should be a means not an end. Our guiding principle should be to first diagnose what is going wrong in a system and then identify which solutions are best suited to solve those problems.

Some causes of the learning crisis are well understood. The poor quality of teaching is a key factor. Teachers often lack subject knowledge and have not had adequate training. There are ways in which technology could address this – and so EdTech may be equally valuable in teaching teachers as it is in teaching students. By offering distance learning, EdTech can provide in-service training or combine online and in-person training (blended learning).

There is also evidence that teachers need better incentives. The idea is that that they can teach well but are not motivated to do so. It is not clear how EdTech can address this problem. Digitized school management systems could better track teacher performance (by tracking their students’ performance) and then linking to pay or other incentives. However, the main need is to design the incentive system; digital applications may only make that system more efficient.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students. It can be seen as a partial solution for two fundamental learning crisis problems: addressing students at different learning levels and completing the syllabus. A classroom contains students with a range of baseline learning levels and teachers are often incentivized to teach to the upper stratum, leaving many students behind. Furthermore, teachers are pressured to cover the syllabus by year’s end. They move on to new material even if students have not mastered previous lessons. This also leaves students behind.

The solution to both problems is, of course, more tailored teaching, but a teacher is hard-pressed to provide one-on-one tutoring to 30 or 40 kids. EdTech might help provide one-to-one instruction (e.g., one student to one tablet) so pupils can learn at their own level and pace. The evidence from rigorous assessments (largely in the United States) is that packages that use artificial intelligence to adjust to a student’s level can improve results, especially in math.

However, we need to be cautious. Most of the evidence comes from contexts in which the quality of teaching is already quite good and is much above the average in developing countries. Digital systems can also help increase the efficiency of formative assessment and make it more likely that such assessment will be conducted. Tracking of students’ learning, through data collection and analysis, can help to better monitor a student’s learning level and provide level-appropriate teaching and remediation.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students.

Edtech software, introduced in conjunction with other reforms, holds some promise. One notable success is Mindspark in India , which improves math and Hindi learning. It has been evaluated as an after-hours supplement and combined with human teaching assistance. More assessments of programs would be helpful.

There is also evidence that low-tech interventions for “teaching at the right level" can also have large impacts on learning. Careful analysis is needed to determine whether high-tech or low-tech solutions are best, given that low tech is less costly, and finance is a constraint in poor countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given a big push to EdTech. We can learn from these experiences but need to keep them in context. EdTech is being used to overcome the need to social distance. Teachers are teaching by video but not necessarily teaching better than when standing in front of a classroom. Zoom fatigue is a problem. More mass open online courses are being offered and are being taken up – but much of this is not for basic education and therefore does not address the learning crisis.

Supporting EdTech solutions comes with four caveats. First, new initiatives need to be well-designed to address specific weaknesses. Low-quality teacher training delivered partially online is no better than low-quality in-person training. The same applies to computer-assisted learning.

Second, computer-assisted learning is often used in schools or in after-hours programs at or near schools. Delivering as distance learning is trickier. It requires hardware and connectivity at home, which is not available to children in low-income households in developing countries and even developed ones.

Third, EdTech programs used outside normal classroom hours adds to the time children spend learning. This is good but it is not always clear whether the benefits are coming from EdTech, per se, or simply more time spent learning. Nonetheless, gamification and other techniques may make children want to spend more time learning.

Finally, let us keep in mind that good learning outcomes can be achieved without EdTech. Developed countries got results before the advent of EdTech. So too did good schools in developing countries.

To be effective, EdTech must address key causes of the crisis and be part of a larger package of reforms. Those reforms include teacher training, incentives, monitoring, teaching at the right level, remediation for underperforming students, and others.

Digital technologies have changed our lives in many ways, mostly for the good. EdTech could do the same by playing a role in addressing the learning crisis.

Published: 23 July 2021

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Never miss a blog post. Get updates on development in Asia and the Pacific into your mailbox.

Straight Talk in Your Inbox

Adb blog team, browse adb.org, other adb sites.

ADB encourages websites and blogs to link to its web pages.

Seven Solutions for Education Inequality

Giving compass' take:.

- Jermeelah Martin shares seven solutions that can reduce and help to eliminate education inequality in the United States.

- What role are you ready to take on to address education inequality? What does education inequality look like in your community?

- Read about comprehensive strategies for promoting educational equity .

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us .

Systemic issues in funding drives education inequality and has detrimental effects primarily on low-income Black and Brown students. These students receive lower quality of education which is reflected through less qualified teachers,not enough books, technologies and special support like counselors and disability services. The lack of access to fair, quality education creates the broader income and wealth gaps in the U.S. Black and brown students face more hurdles to going to college and will be three times more likely to experience poverty as a American with only a highschool degree than an American with a college degree. Income inequality worsens the opportunity for building wealth for Black and Brown families because home and asset ownership will be more difficult to attain.

- Concretely, the first solution would be to reduce class distinctions among students by doing away with the property tax as a primary funding source. This is a significant driver for education inequality because low-income students, by default, will receive less. Instead, the state government should create more significant initiatives and budgets for equitable funding.

- Stop the expansion of charter and private schools as it is not affordable for all students and creates segregation.

- Deprioritize test based funding because it discriminates against disadvantaged students.

- Support teachers financially, as in offering higher salaries and benefits for teachers to improve retention.

- Invest more resources for support in low-income, underfunded schools such as, increased special education specialists and counselors.

- Dismantle the school to prison pipeline for students by adopting more restorative justice efforts and fewer funds for cops in schools. This will create more funds for education justice initiatives and work to end the over policing of minority students.

- More broadly, supporting efforts to dismantle the influence of capitalism in our social sector and supporting an economy that taxes the wealthy at a higher rate will allow for adequate support and funding of public sectors like public education and support for low-income families.

Read the full article about solutions for education inequality by Jermeelah Martin at United for a Fair Economy.

More Articles

Our education funding system is broken. we can fix it., learning policy institute, nov 21, 2022, the funding gap between charter schools and traditional public schools, may 22, 2019.

Become a newsletter subscriber to stay up-to-date on the latest Giving Compass news.

Donate to Giving Compass to help us guide donors toward practices that advance equity.

Partnerships

© 2024 Giving Compass Network

A 501(c)(3) organization. EIN: 85-1311683

Livelihoods

Health and nutrition

Climate and environment

Emergencies

Gender equality

Policy and advocacy

View all countries

View all publications

View all news

What we stand for

Our history

Why partner with Concern?

Public donations

Institutions and Partnerships

Trusts and foundations

Corporate donations

Donations over £1,000

How money is spent

Annual reports

How we are governed

Codes and policies

Supply chain

Through to 2

Hunger crisis appeal

Donating by post and phone

Corporate giving

Emergency support

Concern Philanthropic Circle

Donate in memory

Leave a gift in your will

Wedding favours

Your donation and Gift Aid

Volunteer in Northern Ireland

Volunteer internationally

- Ration Challenge

London Marathon

London Landmarks Half Marathon

Skydive for Concern

Start your own fundraiser

Charity fundraising tips

FAST Youth Ambassador

Knowledge Matters Magazine

Global Hunger Index

Learning Papers

Where we work

Research and reports

Latest news

Our annual report

How we raise money

Transparency and accountability

Donate today

Donate to Concern

Partner with us

Campaign with us

Buy an alternative gift

Other ways to support

Events and challenges

Schools and youth

Our Northern Ireland shops

Knowledge Hub

Knowledge Hub resources

- Debating at school

- Volunteer with us

- Job vacancies

10 of the biggest problems facing education

Children across the UK are heading back to school in the coming weeks. However, 250 million children around the world will be left out of the classroom. Revised for 2024, here are 10 of the biggest problems facing education around the world.

Education can help us end poverty. It gives kids the skills they need to survive and thrive, opening the door to jobs, resources, and everything else that they need to live full, creative lives. In fact, UNESCO reports that if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, an estimated 171 million people could escape the cycle of poverty . And if all adults completed their secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

So why are 250 million children around the world currently out of school? We aren’t at a loss for reasons after the last few years. Here are the top 10 problems facing education in 2024.

1. Conflict and violence

Conflict is one of the main reasons that kids are kept out of the classroom, with USAID estimating that half of all children not attending school are living in a conflict zone — some 125 million in total. To get a sense of this as a growing issue, in 2013, UNESCO reported that conflict was keeping 50 million students out of the classroom. Last year alone, 19 million children in Sudan were out of school due to renewed conflict.

Education is a lifeline during a conflict, protecting children from forced recruitment and potential attacks, while giving them a sense of normalcy in times that are anything but. It’s also a critical element in reducing the chance of future conflicts in certain areas. However, despite international humanitarian law, schools have become targets of attacks in many recent conflicts. Many parents have opted to keep their children at home as a result. However, these are not easy years to make up. According to UNESCO, the first two years of the Syria crisis erased all the country's educational progress since the start of the 21st century. Recovering these missed years also takes more time and effort, with many Syrian children requiring psychosocial care that hinders a "normal" learning curve. Unfortunately, as conflicts become more protracted, they are also threatening to create multiple lost generations.

2. Violence and bullying in the classroom

Violence can also carry over into the classroom. One UN study found that, while 102 countries have banned corporal punishment in schools, that ban isn’t always enforced. Many children have faced sexual violence and bullying in the classroom, either from fellow pupils or faculty and staff.

Children will often drop out of school altogether to avoid these situations. Even when they stay in school, the violence they experience can affect their social skills and self-esteem. It also has a negative impact on their educational achievement. Concern has addressed this head-on in Sierra Leone with our Safe Learning Model .

3. Climate change

Climate change is another major threat to education. Extreme weather events and related natural disasters destroy schools and other infrastructure key to accessing education (such as roads), and rebuilding damaged classrooms doesn’t happen overnight.

Climate change also affects children’s health, both physical and emotional, making it hard to keep up with school (and at times making it hard for teachers themselves to focus on delivering a quality education). With climate change linked so tightly to poverty, it also leads families to withdraw their children from school when they can no longer afford the fees or need their children to contribute to the household income.

4. Harvest seasons and market days

In agricultural communities, the harvest is both a vital source of food and income. During these periods, children are often required to skip school to help their families harvest and sell crops. Sometimes they'll be out of school for weeks at a stretch. Families who make their living from farming may also have to move around if they have herds that graze, or to harvest crops planted in different areas. This is also disruptive for children and their education.

5. Unpaid and underqualified teachers

When governments are dysfunctional, public servants aren’t paid. That includes teachers. In some countries, teachers aren’t paid for months at a time. Many have no choice but to quit their posts to find other sources of income or are moved to other districts.

As a result, schools often struggle to find qualified teachers to replace those who have left. But, without qualified teachers in the classrooms, children suffer the most. In sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank estimates that the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 (with no updates yet as to how the pandemic may have affected these numbers). The World Bank adds that teachers in STEM are especially hard to come by in low-income countries.

6. The cost of supplies and uniforms

Although many countries provide free primary education, attending school still comes at a cost. Parents and caretakers often pay for mandatory uniforms and other fees. School supplies are also necessary. These costs alone can keep students out of the classroom.

7. Being an older student

According to UNICEF, adolescents are twice as likely to be out of school compared to younger children. Globally, that means one in five students between the ages of 12 and 15 is out of school. As children get older, they face increased pressure to drop out so that they can work and contribute to their family income.

One solution we’ve adopted at Concern is to help those who didn't complete their education learn many of the things they missed out on, including financial literacy, business management, and vocational skills.

8. Being female

In many countries around the world, girls are more likely to be excluded from education than boys. This is despite all the efforts and progress made in recent years to increase the number of girls in school. According to UNESCO, up to 80% of school-aged girls who are currently out of school are unlikely to ever start. For boys, that same figure is just 16%. This rate is highest in emergency situations and fragile contexts.

Many schools have no toilets (let alone separate bathrooms for boys and girls). This usually means more missed days for girls when they get their period. The World Bank estimates that girls around the world miss up to 20% of their school days due to period poverty and stigma.

Girls may also be pressured to drop out of school to help out their family, as we mentioned above with regards to taking a job. However, in many countries where Concern works, they may also be forced out of school to get married. Girls who enter into an early or forced marriage usually leave school to take care of their new families. According to the UN, 33% of girls in low-income countries wed before the age of 18. Just over 11% get married before the age of 15. In most instances, marriage and having children mean the end of a girl’s formal education.

9. Outbreaks and epidemics

We learned this the hard way with COVID-19. Even if the student body is healthy, they may be kept out of school if an epidemic has hit their area. Teachers might get sick, and families with sick parents may need their children to stay home and help out. Quarantines often go into effect.

The 2014-16 West African Ebola outbreak was a severe problem for education in countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone . Ebola put the education of 3 million children in these countries on hold. As a response, we worked with the governments of both countries to deliver lessons by radio. We also trained community members to work with small groups of children on basic reading and maths. As schools reopened, we shifted our focus to helping children get back into classrooms safely, but many kids still had a lot of catching up to do.

10. Language and literacy barriers

Even if a child goes to school in the town where they were born and grew up their entire life, they may face a language barrier in the classroom between their mother tongue and the official lingua franca used in education systems. In Marsabit county, Kenya , the first language for most children is Borana. Once students start school, they must learn two new languages to understand their teachers: Swahili and English.

UNESCO estimates that 40% of school-aged children don’t have access to education in a language that they understand. This is especially difficult for students who have migrated to a new country, such as Syrian refugee children being hosted in Türkiye : Not only do they have to switch from Levantine Arabic to Turkish, but they also have to learn an entirely new alphabet.

This dovetails with literacy, another key issue in education. If a student struggles with reading (even in their mother tongue), it can have a ripple effect on their ability to learn in all other subjects. Many students drop out if they feel like they can’t keep up, either due to the quality of the teaching or to a special accommodation they need for their learning that can’t be made.