- Privacy Policy

Home » Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Descriptive Research Design

Definition:

Descriptive research design is a type of research methodology that aims to describe or document the characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, opinions, or perceptions of a group or population being studied.

Descriptive research design does not attempt to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables or make predictions about future outcomes. Instead, it focuses on providing a detailed and accurate representation of the data collected, which can be useful for generating hypotheses, exploring trends, and identifying patterns in the data.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

Types of Descriptive Research Design are as follows:

Cross-sectional Study

This involves collecting data at a single point in time from a sample or population to describe their characteristics or behaviors. For example, a researcher may conduct a cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of certain health conditions among a population, or to describe the attitudes and beliefs of a particular group.

Longitudinal Study

This involves collecting data over an extended period of time, often through repeated observations or surveys of the same group or population. Longitudinal studies can be used to track changes in attitudes, behaviors, or outcomes over time, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

This involves an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, or situation to gain a detailed understanding of its characteristics or dynamics. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and business to explore complex phenomena or to generate hypotheses for further research.

Survey Research

This involves collecting data from a sample or population through standardized questionnaires or interviews. Surveys can be used to describe attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or demographic characteristics of a group, and can be conducted in person, by phone, or online.

Observational Research

This involves observing and documenting the behavior or interactions of individuals or groups in a natural or controlled setting. Observational studies can be used to describe social, cultural, or environmental phenomena, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

Correlational Research

This involves examining the relationships between two or more variables to describe their patterns or associations. Correlational studies can be used to identify potential causal relationships or to explore the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

Data Analysis Methods

Descriptive research design data analysis methods depend on the type of data collected and the research question being addressed. Here are some common methods of data analysis for descriptive research:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves analyzing data to summarize and describe the key features of a sample or population. Descriptive statistics can include measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and measures of variability (e.g., range, standard deviation).

Cross-tabulation

This method involves analyzing data by creating a table that shows the frequency of two or more variables together. Cross-tabulation can help identify patterns or relationships between variables.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing qualitative data (e.g., text, images, audio) to identify themes, patterns, or trends. Content analysis can be used to describe the characteristics of a sample or population, or to identify factors that influence attitudes or behaviors.

Qualitative Coding

This method involves analyzing qualitative data by assigning codes to segments of data based on their meaning or content. Qualitative coding can be used to identify common themes, patterns, or categories within the data.

Visualization

This method involves creating graphs or charts to represent data visually. Visualization can help identify patterns or relationships between variables and make it easier to communicate findings to others.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing data across different groups or time periods to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help describe changes in attitudes or behaviors over time or differences between subgroups within a population.

Applications of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has numerous applications in various fields. Some of the common applications of descriptive research design are:

- Market research: Descriptive research design is widely used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes. This helps companies to develop new products and services, improve marketing strategies, and increase customer satisfaction.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is used in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population. This helps healthcare providers to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs. This helps educators to improve teaching methods and develop effective educational programs.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs. This helps researchers to understand social behavior and develop effective policies.

- Public opinion research: Descriptive research design is used in public opinion research to understand the opinions and attitudes of the general public on various issues. This helps policymakers to develop effective policies that are aligned with public opinion.

- Environmental research: Descriptive research design is used in environmental research to describe the environmental conditions of a particular region or ecosystem. This helps policymakers and environmentalists to develop effective conservation and preservation strategies.

Descriptive Research Design Examples

Here are some real-time examples of descriptive research designs:

- A restaurant chain wants to understand the demographics and attitudes of its customers. They conduct a survey asking customers about their age, gender, income, frequency of visits, favorite menu items, and overall satisfaction. The survey data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to describe the characteristics of their customer base.

- A medical researcher wants to describe the prevalence and risk factors of a particular disease in a population. They conduct a cross-sectional study in which they collect data from a sample of individuals using a standardized questionnaire. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to identify patterns in the prevalence and risk factors of the disease.

- An education researcher wants to describe the learning outcomes of students in a particular school district. They collect test scores from a representative sample of students in the district and use descriptive statistics to calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation of the scores. They also create visualizations such as histograms and box plots to show the distribution of scores.

- A marketing team wants to understand the attitudes and behaviors of consumers towards a new product. They conduct a series of focus groups and use qualitative coding to identify common themes and patterns in the data. They also create visualizations such as word clouds to show the most frequently mentioned topics.

- An environmental scientist wants to describe the biodiversity of a particular ecosystem. They conduct an observational study in which they collect data on the species and abundance of plants and animals in the ecosystem. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the diversity and richness of the ecosystem.

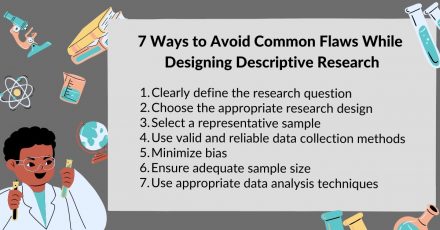

How to Conduct Descriptive Research Design

To conduct a descriptive research design, you can follow these general steps:

- Define your research question: Clearly define the research question or problem that you want to address. Your research question should be specific and focused to guide your data collection and analysis.

- Choose your research method: Select the most appropriate research method for your research question. As discussed earlier, common research methods for descriptive research include surveys, case studies, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies.

- Design your study: Plan the details of your study, including the sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis plan. Determine the sample size and sampling method, decide on the data collection tools (such as questionnaires, interviews, or observations), and outline your data analysis plan.

- Collect data: Collect data from your sample or population using the data collection tools you have chosen. Ensure that you follow ethical guidelines for research and obtain informed consent from participants.

- Analyze data: Use appropriate statistical or qualitative analysis methods to analyze your data. As discussed earlier, common data analysis methods for descriptive research include descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation, content analysis, qualitative coding, visualization, and comparative analysis.

- I nterpret results: Interpret your findings in light of your research question and objectives. Identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data, and describe the characteristics of your sample or population.

- Draw conclusions and report results: Draw conclusions based on your analysis and interpretation of the data. Report your results in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate tables, graphs, or figures to present your findings. Ensure that your report follows accepted research standards and guidelines.

When to Use Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is used in situations where the researcher wants to describe a population or phenomenon in detail. It is used to gather information about the current status or condition of a group or phenomenon without making any causal inferences. Descriptive research design is useful in the following situations:

- Exploratory research: Descriptive research design is often used in exploratory research to gain an initial understanding of a phenomenon or population.

- Identifying trends: Descriptive research design can be used to identify trends or patterns in a population, such as changes in consumer behavior or attitudes over time.

- Market research: Descriptive research design is commonly used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is useful in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs.

Purpose of Descriptive Research Design

The main purpose of descriptive research design is to describe and measure the characteristics of a population or phenomenon in a systematic and objective manner. It involves collecting data that describe the current status or condition of the population or phenomenon of interest, without manipulating or altering any variables.

The purpose of descriptive research design can be summarized as follows:

- To provide an accurate description of a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research design aims to provide a comprehensive and accurate description of a population or phenomenon of interest. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon.

- To identify trends and patterns: Descriptive research design can help researchers to identify trends and patterns in the data, such as changes in behavior or attitudes over time. This can be useful for making predictions and developing strategies.

- To generate hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- To establish a baseline: Descriptive research design can establish a baseline or starting point for future research. This can be useful for comparing data from different time periods or populations.

Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several key characteristics that distinguish it from other research designs. Some of the main characteristics of descriptive research design are:

- Objective : Descriptive research design is objective in nature, which means that it focuses on collecting factual and accurate data without any personal bias. The researcher aims to report the data objectively without any personal interpretation.

- Non-experimental: Descriptive research design is non-experimental, which means that the researcher does not manipulate any variables. The researcher simply observes and records the behavior or characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Quantitative : Descriptive research design is quantitative in nature, which means that it involves collecting numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. This helps to provide a more precise and accurate description of the population or phenomenon.

- Cross-sectional: Descriptive research design is often cross-sectional, which means that the data is collected at a single point in time. This can be useful for understanding the current state of the population or phenomenon, but it may not provide information about changes over time.

- Large sample size: Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Systematic and structured: Descriptive research design involves a systematic and structured approach to data collection, which helps to ensure that the data is accurate and reliable. This involves using standardized procedures for data collection, such as surveys, questionnaires, or observation checklists.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several advantages that make it a popular choice for researchers. Some of the main advantages of descriptive research design are:

- Provides an accurate description: Descriptive research design is focused on accurately describing the characteristics of a population or phenomenon. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the subject of interest.

- Easy to conduct: Descriptive research design is relatively easy to conduct and requires minimal resources compared to other research designs. It can be conducted quickly and efficiently, and data can be collected through surveys, questionnaires, or observations.

- Useful for generating hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- Large sample size : Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Can be used to monitor changes : Descriptive research design can be used to monitor changes over time in a population or phenomenon. This can be useful for identifying trends and patterns, and for making predictions about future behavior or attitudes.

- Can be used in a variety of fields : Descriptive research design can be used in a variety of fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, and education.

Limitation of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design also has some limitations that researchers should consider before using this design. Some of the main limitations of descriptive research design are:

- Cannot establish cause and effect: Descriptive research design cannot establish cause and effect relationships between variables. It only provides a description of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited generalizability: The results of a descriptive study may not be generalizable to other populations or situations. This is because descriptive research design often involves a specific sample or situation, which may not be representative of the broader population.

- Potential for bias: Descriptive research design can be subject to bias, particularly if the researcher is not objective in their data collection or interpretation. This can lead to inaccurate or incomplete descriptions of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited depth: Descriptive research design may provide a superficial description of the population or phenomenon of interest. It does not delve into the underlying causes or mechanisms behind the observed behavior or characteristics.

- Limited utility for theory development: Descriptive research design may not be useful for developing theories about the relationship between variables. It only provides a description of the variables themselves.

- Relies on self-report data: Descriptive research design often relies on self-report data, such as surveys or questionnaires. This type of data may be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Descriptive Research? Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Descriptive research is a methodological approach that seeks to depict the characteristics of a phenomenon or subject under investigation. In scientific inquiry, it serves as a foundational tool for researchers aiming to observe, record, and analyze the intricate details of a particular topic. This method provides a rich and detailed account that aids in understanding, categorizing, and interpreting the subject matter.

Descriptive research design is widely employed across diverse fields, and its primary objective is to systematically observe and document all variables and conditions influencing the phenomenon.

After this descriptive research definition, let’s look at this example. Consider a researcher working on climate change adaptation, who wants to understand water management trends in an arid village in a specific study area. She must conduct a demographic survey of the region, gather population data, and then conduct descriptive research on this demographic segment. The study will then uncover details on “what are the water management practices and trends in village X.” Note, however, that it will not cover any investigative information about “why” the patterns exist.

Table of Contents

What is descriptive research?

If you’ve been wondering “What is descriptive research,” we’ve got you covered in this post! In a nutshell, descriptive research is an exploratory research method that helps a researcher describe a population, circumstance, or phenomenon. It can help answer what , where , when and how questions, but not why questions. In other words, it does not involve changing the study variables and does not seek to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Importance of descriptive research

Now, let’s delve into the importance of descriptive research. This research method acts as the cornerstone for various academic and applied disciplines. Its primary significance lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive overview of a phenomenon, enabling researchers to gain a nuanced understanding of the variables at play. This method aids in forming hypotheses, generating insights, and laying the groundwork for further in-depth investigations. The following points further illustrate its importance:

Provides insights into a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research furnishes a comprehensive overview of the characteristics and behaviors of a specific population or phenomenon, thereby guiding and shaping the research project.

Offers baseline data: The data acquired through this type of research acts as a reference for subsequent investigations, laying the groundwork for further studies.

Allows validation of sampling methods: Descriptive research validates sampling methods, aiding in the selection of the most effective approach for the study.

Helps reduce time and costs: It is cost-effective and time-efficient, making this an economical means of gathering information about a specific population or phenomenon.

Ensures replicability: Descriptive research is easily replicable, ensuring a reliable way to collect and compare information from various sources.

When to use descriptive research design?

Determining when to use descriptive research depends on the nature of the research question. Before diving into the reasons behind an occurrence, understanding the how, when, and where aspects is essential. Descriptive research design is a suitable option when the research objective is to discern characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories without manipulating variables. It is therefore often employed in the initial stages of a study before progressing to more complex research designs. To put it in another way, descriptive research precedes the hypotheses of explanatory research. It is particularly valuable when there is limited existing knowledge about the subject.

Some examples are as follows, highlighting that these questions would arise before a clear outline of the research plan is established:

- In the last two decades, what changes have occurred in patterns of urban gardening in Mumbai?

- What are the differences in climate change perceptions of farmers in coastal versus inland villages in the Philippines?

Characteristics of descriptive research

Coming to the characteristics of descriptive research, this approach is characterized by its focus on observing and documenting the features of a subject. Specific characteristics are as below.

- Quantitative nature: Some descriptive research types involve quantitative research methods to gather quantifiable information for statistical analysis of the population sample.

- Qualitative nature: Some descriptive research examples include those using the qualitative research method to describe or explain the research problem.

- Observational nature: This approach is non-invasive and observational because the study variables remain untouched. Researchers merely observe and report, without introducing interventions that could impact the subject(s).

- Cross-sectional nature: In descriptive research, different sections belonging to the same group are studied, providing a “snapshot” of sorts.

- Springboard for further research: The data collected are further studied and analyzed using different research techniques. This approach helps guide the suitable research methods to be employed.

Types of descriptive research

There are various descriptive research types, each suited to different research objectives. Take a look at the different types below.

- Surveys: This involves collecting data through questionnaires or interviews to gather qualitative and quantitative data.

- Observational studies: This involves observing and collecting data on a particular population or phenomenon without influencing the study variables or manipulating the conditions. These may be further divided into cohort studies, case studies, and cross-sectional studies:

- Cohort studies: Also known as longitudinal studies, these studies involve the collection of data over an extended period, allowing researchers to track changes and trends.

- Case studies: These deal with a single individual, group, or event, which might be rare or unusual.

- Cross-sectional studies : A researcher collects data at a single point in time, in order to obtain a snapshot of a specific moment.

- Focus groups: In this approach, a small group of people are brought together to discuss a topic. The researcher moderates and records the group discussion. This can also be considered a “participatory” observational method.

- Descriptive classification: Relevant to the biological sciences, this type of approach may be used to classify living organisms.

Descriptive research methods

Several descriptive research methods can be employed, and these are more or less similar to the types of approaches mentioned above.

- Surveys: This method involves the collection of data through questionnaires or interviews. Surveys may be done online or offline, and the target subjects might be hyper-local, regional, or global.

- Observational studies: These entail the direct observation of subjects in their natural environment. These include case studies, dealing with a single case or individual, as well as cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, for a glimpse into a population or changes in trends over time, respectively. Participatory observational studies such as focus group discussions may also fall under this method.

Researchers must carefully consider descriptive research methods, types, and examples to harness their full potential in contributing to scientific knowledge.

Examples of descriptive research

Now, let’s consider some descriptive research examples.

- In social sciences, an example could be a study analyzing the demographics of a specific community to understand its socio-economic characteristics.

- In business, a market research survey aiming to describe consumer preferences would be a descriptive study.

- In ecology, a researcher might undertake a survey of all the types of monocots naturally occurring in a region and classify them up to species level.

These examples showcase the versatility of descriptive research across diverse fields.

Advantages of descriptive research

There are several advantages to this approach, which every researcher must be aware of. These are as follows:

- Owing to the numerous descriptive research methods and types, primary data can be obtained in diverse ways and be used for developing a research hypothesis .

- It is a versatile research method and allows flexibility.

- Detailed and comprehensive information can be obtained because the data collected can be qualitative or quantitative.

- It is carried out in the natural environment, which greatly minimizes certain types of bias and ethical concerns.

- It is an inexpensive and efficient approach, even with large sample sizes

Disadvantages of descriptive research

On the other hand, this design has some drawbacks as well:

- It is limited in its scope as it does not determine cause-and-effect relationships.

- The approach does not generate new information and simply depends on existing data.

- Study variables are not manipulated or controlled, and this limits the conclusions to be drawn.

- Descriptive research findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Finally, it offers a preliminary understanding rather than an in-depth understanding.

To reiterate, the advantages of descriptive research lie in its ability to provide a comprehensive overview, aid hypothesis generation, and serve as a preliminary step in the research process. However, its limitations include a potential lack of depth, inability to establish cause-and-effect relationships, and susceptibility to bias.

Frequently asked questions

When should researchers conduct descriptive research.

Descriptive research is most appropriate when researchers aim to portray and understand the characteristics of a phenomenon without manipulating variables. It is particularly valuable in the early stages of a study.

What is the difference between descriptive and exploratory research?

Descriptive research focuses on providing a detailed depiction of a phenomenon, while exploratory research aims to explore and generate insights into an issue where little is known.

What is the difference between descriptive and experimental research?

Descriptive research observes and documents without manipulating variables, whereas experimental research involves intentional interventions to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Is descriptive research only for social sciences?

No, various descriptive research types may be applicable to all fields of study, including social science, humanities, physical science, and biological science.

How important is descriptive research?

The importance of descriptive research lies in its ability to provide a glimpse of the current state of a phenomenon, offering valuable insights and establishing a basic understanding. Further, the advantages of descriptive research include its capacity to offer a straightforward depiction of a situation or phenomenon, facilitate the identification of patterns or trends, and serve as a useful starting point for more in-depth investigations. Additionally, descriptive research can contribute to the development of hypotheses and guide the formulation of research questions for subsequent studies.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when , and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when, and where it happens.

- How has the London housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product Y or product Z?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural, and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analysed for frequencies, averages, and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organisation’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social, and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models, or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event, or organisation). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalisable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/descriptive-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, correlational research | guide, design & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review

MSN, CRNP, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Justine S. Sefcik

MS, RN, Doctoral Candidate, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Christine Bradway

PhD, CRNP, FAAN, Associate Professor of Gerontological Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Qualitative description (QD) is a term that is widely used to describe qualitative studies of health care and nursing-related phenomena. However, limited discussions regarding QD are found in the existing literature. In this systematic review, we identified characteristics of methods and findings reported in research articles published in 2014 whose authors identified the work as QD. After searching and screening, data were extracted from the sample of 55 QD articles and examined to characterize research objectives, design justification, theoretical/philosophical frameworks, sampling and sample size, data collection and sources, data analysis, and presentation of findings. In this review, three primary findings were identified. First, despite inconsistencies, most articles included characteristics consistent with limited, available QD definitions and descriptions. Next, flexibility or variability of methods was common and desirable for obtaining rich data and achieving understanding of a phenomenon. Finally, justification for how a QD approach was chosen and why it would be an appropriate fit for a particular study was limited in the sample and, therefore, in need of increased attention. Based on these findings, recommendations include encouragement to researchers to provide as many details as possible regarding the methods of their QD study so that readers can determine whether the methods used were reasonable and effective in producing useful findings.

Qualitative description (QD) is a label used in qualitative research for studies which are descriptive in nature, particularly for examining health care and nursing-related phenomena ( Polit & Beck, 2009 , 2014 ). QD is a widely cited research tradition and has been identified as important and appropriate for research questions focused on discovering the who, what, and where of events or experiences and gaining insights from informants regarding a poorly understood phenomenon. It is also the label of choice when a straight description of a phenomenon is desired or information is sought to develop and refine questionnaires or interventions ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005 ).

Despite many strengths and frequent citations of its use, limited discussions regarding QD are found in qualitative research textbooks and publications. To the best of our knowledge, only seven articles include specific guidance on how to design, implement, analyze, or report the results of a QD study ( Milne & Oberle, 2005 ; Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 , 2010 ; Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, & Harper, 2005 ; Vaismoradi, Turunen, & Bondas, 2013 ; Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, & Zichi-Cohen, 2016 ). Furthermore, little is known about characteristics of QD as reported in journal-published, nursing-related, qualitative studies. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to describe specific characteristics of methods and findings of studies reported in journal articles (published in 2014) self-labeled as QD. In this review, we did not have a goal to judge whether QD was done correctly but rather to report on the features of the methods and findings.

Features of QD

Several QD design features and techniques have been described in the literature. First, researchers generally draw from a naturalistic perspective and examine a phenomenon in its natural state ( Sandelowski, 2000 ). Second, QD has been described as less theoretical compared to other qualitative approaches ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ), facilitating flexibility in commitment to a theory or framework when designing and conducting a study ( Sandelowski, 2000 , 2010 ). For example, researchers may or may not decide to begin with a theory of the targeted phenomenon and do not need to stay committed to a theory or framework if their investigations take them down another path ( Sandelowski, 2010 ). Third, data collection strategies typically involve individual and/or focus group interviews with minimal to semi-structured interview guides ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). Fourth, researchers commonly employ purposeful sampling techniques such as maximum variation sampling which has been described as being useful for obtaining broad insights and rich information ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). Fifth, content analysis (and in many cases, supplemented by descriptive quantitative data to describe the study sample) is considered a primary strategy for data analysis ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ). In some instances thematic analysis may also be used to analyze data; however, experts suggest care should be taken that this type of analysis is not confused with content analysis ( Vaismoradi et al., 2013 ). These data analysis approaches allow researchers to stay close to the data and as such, interpretation is of low-inference ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ), meaning that different researchers will agree more readily on the same findings even if they do not choose to present the findings in the same way ( Sandelowski, 2000 ). Finally, representation of study findings in published reports is expected to be straightforward, including comprehensive descriptive summaries and accurate details of the data collected, and presented in a way that makes sense to the reader ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ; Sandelowski, 2000 ).

It is also important to acknowledge that variations in methods or techniques may be appropriate across QD studies ( Sandelowski, 2010 ). For example, when consistent with the study goals, decisions may be made to use techniques from other qualitative traditions, such as employing a constant comparative analytic approach typically associated with grounded theory ( Sandelowski, 2000 ).

Search Strategy and Study Screening

The PubMed electronic database was searched for articles written in English and published from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014, using the terms, “qualitative descriptive study,” “qualitative descriptive design,” and “qualitative description,” combined with “nursing.” This specific publication year, “2014,” was chosen because it was the most recent full year at the time of beginning this systematic review. As we did not intend to identify trends in QD approaches over time, it seemed reasonable to focus on the nursing QD studies published in a certain year. The inclusion criterion for this review was data-based, nursing-related, research articles in which authors used the terms QD, qualitative descriptive study, or qualitative descriptive design in their titles or abstracts as well as in the main texts of the publication.

All articles yielded through an initial search in PubMed were exported into EndNote X7 ( Thomson Reuters, 2014 ), a reference management software, and duplicates were removed. Next, titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine if the publication met inclusion criteria; all articles meeting inclusion criteria were then read independently in full by two authors (HK and JS) to determine if the terms – QD or qualitative descriptive study/design – were clearly stated in the main texts. Any articles in which researchers did not specifically state these key terms in the main text were then excluded, even if the terms had been used in the study title or abstract. In one article, for example, although “qualitative descriptive study” was reported in the published abstract, the researchers reported a “qualitative exploratory design” in the main text of the article ( Sundqvist & Carlsson, 2014 ); therefore, this article was excluded from our review. Despite the possibility that there may be other QD studies published in 2014 that were not labeled as such, to facilitate our screening process we only included articles where the researchers clearly used our search terms for their approach. Finally, the two authors compared, discussed, and reconciled their lists of articles with a third author (CB).

Study Selection

Initially, although the year 2014 was specifically requested, 95 articles were identified (due to ahead of print/Epub) and exported into the EndNote program. Three duplicate publications were removed and the 20 articles with final publication dates of 2015 were also excluded. The remaining 72 articles were then screened by examining titles, abstracts, and full-texts. Based on our inclusion criteria, 15 (of 72) were then excluded because QD or QD design/study was not identified in the main text. We then re-examined the remaining 57 articles and excluded two additional articles that did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., QD was only reported as an analytic approach in the data analysis section). The remaining 55 publications met inclusion criteria and comprised the sample for our systematic review (see Figure 1 ).

Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Of the 55 publications, 23 originated from North America (17 in the United States; 6 in Canada), 12 from Asia, 11 from Europe, 7 from Australia and New Zealand, and 2 from South America. Eleven studies were part of larger research projects and two of them were reported as part of larger mixed-methods studies. Four were described as a secondary analysis.

Quality Appraisal Process

Following the identification of the 55 publications, two authors (HK and JS) independently examined each article using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist ( CASP, 2013 ). The CASP was chosen to determine the general adequacy (or rigor) of the qualitative studies included in this review as the CASP criteria are generic and intend to be applied to qualitative studies in general. In addition, the CASP was useful because we were able to examine the internal consistency between study aims and methods and between study aims and findings as well as the usefulness of findings ( CASP, 2013 ). The CASP consists of 10 main questions with several sub-questions to consider when making a decision about the main question ( CASP, 2013 ). The first two questions have reviewers examine the clarity of study aims and appropriateness of using qualitative research to achieve the aims. With the next eight questions, reviewers assess study design, sampling, data collection, and analysis as well as the clarity of the study’s results statement and the value of the research. We used the seven questions and 17 sub-questions related to methods and statement of findings to evaluate the articles. The results of this process are presented in Table 1 .

CASP Questions and Quality Appraisal Results (N = 55)

| CASP Questions • CASP Subquestions | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can’t tell | ||||

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher justify the research design? | 26 | 47.3 | 28 | 50.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher explain how the participants were selected? | 44 | 80 | 6 | 10.9 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | ||||||

| • Was the setting for data collection justified? | 31 | 56.4 | 21 | 38.2 | 3 | 5.4 |

| • Was it clear how data were collected e.g., focus group, semistructured interview etc.? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Did the researcher justify the methods chosen? | 13 | 23.6 | 41 | 74.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher make the methods explicit e.g., for the interview method, was there an indication of how interviews were conducted, or did they use a topic guide? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was the form of data clear e.g., tape recordings, video materials, notes, etc.? | 54 | 98.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher discuss saturation of data? | 20 | 36.4 | 35 | 63.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | ||||||

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias, and influence during data collection, including sample recruitment and choice of location | 4 | 7.3 | 50 | 90.9 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | ||||||

| • Was there sufficient detail about how the research was explained to participants for the reader to assess whether ethical standards were maintained? | 49 | 89.1 | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 3.6 |

| • Was approval sought from an ethics committee? | 51 | 92.7 | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | ||||||

| • Was there an in-depth description of the analysis process? | 46 | 83.6 | 9 | 16.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| • Was thematic or content analysis used. If so, was it clear how the categories/themes derived from the data? | 51 | 92.7 | 3 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias and influence during analysis and selection of data for presentation? | 20 | 36.4 | 30 | 54.5 | 5 | 9.1 |

| Was there a clear statement of findings? | ||||||

| • Were the findings explicit? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Did the researcher discuss the credibility of their findings (e.g., triangulation) | 46 | 83.6 | 8 | 14.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| • Were the findings discussed in relation to the original research question? | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note . The CASP questions are adapted from “10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research,” by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013, retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf . Its license can be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

Once articles were assessed by the two authors independently, all three authors discussed and reconciled our assessment. No articles were excluded based on CASP results; rather, results were used to depict the general adequacy (or rigor) of all 55 articles meeting inclusion criteria for our systematic review. In addition, the CASP was included to enhance our examination of the relationship between the methods and the usefulness of the findings documented in each of the QD articles included in this review.

Process for Data Extraction and Analysis

To further assess each of the 55 articles, data were extracted on: (a) research objectives, (b) design justification, (c) theoretical or philosophical framework, (d) sampling and sample size, (e) data collection and data sources, (f) data analysis, and (g) presentation of findings (see Table 2 ). We discussed extracted data and identified common and unique features in the articles included in our systematic review. Findings are described in detail below and in Table 3 .

Elements for Data Extraction

| Elements | Data Extraction |

|---|---|

| Research objectives | • Verbs used in objectives or aims |

| • Focuses of study | |

| Design justification | • If the article cited references for qualitative description |

| • If the article offered rationale to choose qualitative description | |

| • References cited | |

| • Rationale reported | |

| Theoretical or philosophical frameworks | • If the article has theoretical or philosophical frameworks for study |

| • Theoretical or philosophical frameworks reported | |

| • How the frameworks were used in data collection and analysis | |

| Sampling and sample sizes | • Sampling strategies (e.g., purposeful sampling, maximum variation) |

| • Sample size | |

| Data collection and sources | • Data collection techniques (e.g., individual or focus-group interviews, interview guide, surveys, field notes) |

| Data analysis | • Data analysis techniques (e.g., qualitative content analysis, thematic analysis, constant comparison) |

| • If data saturation was achieved | |

| Presentation of findings | • Statement of findings |

| • Consistency with research objectives |

Data Extraction and Analysis Results

| Authors Country | Research Objectives | Design justification | Theoretical/ philosophical frameworks | Sampling/ sample size | Data collection and data sources | Data analysis | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • USA | • Explore • Responses to communication strategies | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | Not reported (NR) | • Purposive sampling/ maximum variation • 32 family members | • Interviews • Observations • Review of daily flow sheet • Demographics | • Inductive and deductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five themes about family members’ perceptions of nursing communication approaches |

| • Sweden | • Describe • Experiences of using guidelines in daily practice | • (-) Reference • (+) Rationale • Part of a research program | NR | • Unspecified • 8 care providers | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | One theme and seven subthemes about care providers’ experiences of using guidelines in daily practice |

| • USA | • Examine • Culturally specific views of processes and causes of midlife weight gain | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | Health belief model and Kleiman’s explanatory model | • Unspecified • 19 adults | • Semistructured, individual interview | • Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three main categories (from the model) and eight subthemes about causes of weight gain in midlife |

| • Iran | • Explore • Factors initiating responsibility among medical trainees | • (-) Reference • (+) Rationale | NR | • Convenience, snowball, and maximum variation sampling • 15 trainees and other professionals | • Semistructured, individual interview • Interview guide | • Conventional content analysis • Constant comparison • (+) Data saturation | Two themes and individual and non- individual-based factors per theme |

| • Iran | • Explore • Factors related to job satisfaction and dissatisfaction | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sampling • 85 nurses | • Semistructured focus group interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three main themes and associated factors regarding job satisfaction and dissatisfaction |

| • Norway | • Describe • Perceptions on simulation-based team training | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Strategic sampling • 18 registered nurses | • Semistructured individual interviews | • Inductive content analysis • (-) Data saturation | One main category, three categories, and six sub- categories regarding nurses’ perceptions on simulation-based team training |

| • USA | • Determine • Barriers and supports for attending college and nursing school | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Unspecified • 45 students | • Focus-group interviews • Using Photovoice and SHOWeD | • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Five themes about facilitators and barriers |

| • USA | • Explore • Reasons for choosing home birth and birth experiences | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 20 women | • Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide • Field notes | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Five common themes and concepts about reasons for choosing home birth based on their birth experiences |

| • New Zealand | • Explore • Normal fetal activity related to hunger and satiation | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Denzin & Lincoln (2011) | NR | • Purposive sampling • 19 pregnant women | • Semistructured individual interviews • Open-ended questions | • Inductive qualitative content analysis • Descriptive statistical analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four patterns regarding fetal activities in relation to meal anticipation, maternal hunger, maternal meal consummation, and maternal satiety |

| • Italy | • Explore, describe, and compare • perceptions of nursing caring | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 20 nurses and 20 patients | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Field notes during interviews | • Unspecified various analytic strategies including constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Nursing caring from both patients’ and nurses’ perspectives – a summary of data in visible caring and invisible caring |

| • Hong Kong | • Address • How to reduce coronary heart disease risks | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Secondary analysis • • | NR | • Convenience and snowball sampling • 105 patients | • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four categories about patients’ abilities to reduce coronary heart disease |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Reasons for young–old people not killing themselves | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sampling • 31 older adults | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide • Observation with memos/reflective journal | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Six themes regarding reasons for not committing to suicide |

| • USA | • Explore • Neonatal intensive care unit experiences | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposive sampling and convenience sample • 15 mothers | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four themes about participants’ experiences of neonatal intensive care unit |

| • Colombia | • Investigate • Barriers/facilitators to implementing evidence-based nursing | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | Ottawa model for research use: knowledge translation framework | • Convenience sampling • 13 nursing professionals | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive qualitative content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Four main barriers and potential facilitators to evidence-based nursing |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions and utilization of diaries | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Unspecified • 19 patients and families | • Responses to open-ended questions on survey | • Unspecified analysis strategy • (-) Data saturation | Five themes regarding perceptions on use of diaries and descriptive statistics using frequencies of utilization |

| • USA | • Explore • Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about sexual consent | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger mixed-method study | Theory of planned behavior | • Purposive sampling • snowball sampling • 26 women | • Semistructured focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three main categories and subthemes regarding sexual consent |

| • Sweden | • Describe • Experiences of knowledge development in wound management | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale: weak • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 16 district nurses | • Individual interviews • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three categories and eleven sub-categories about knowledge development experiences in wound management |

| • USA | • Describe • Parental-pain journey, beliefs about pain, and attitudes/behaviors related to children’s responses | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • • Part of a larger mixed methods study | NR | • Purposive sampling • 9 parents | • Individual interviews • One open- ended question | • Qualitative content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Two main themes, categories, and subcategories about parents’ experiences of observing children’s pain |

| • USA | • Describe • Challenges and barriers in providing culturally competent care | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Secondary analysis | NR | • Stratified sampling • 253 nurses | • Written responses to 2 open-ended questions on survey | • Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three themes regarding challenges/barriers |

| • Denmark | • Describe • Experiences of childbirth | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • A substudy | NR | • Purposive sampling with maximum variation • Partners of 10 women | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three themes and four subthemes about partners’ experiences of women’s childbirth |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions about medical nutrition and hydration at the end of life | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 10 nurses | • Focus-group interviews | • “analyzed thematically” • (-) Data saturation | One main theme and four subthemes regarding nurses’ perceptions on EOL- related medical nutrition and hydration |

| • USA | • Describe • Reasons for leaving a home visiting program early | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Convenience sample • 32 mothers, nurses, and nurse supervisors | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison approach • (+) Data saturation | Three sets of reasons for leaving a home visiting program |

| • Sweden | • Explore and describe • Beliefs and attitudes around the decision for a caesarean section | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • | NR | • Unspecified • 21 males | • Individual telephone interviews | • Thematic analysis • Constant comparison approach • (-) Data saturation | Two themes and subthemes in relation to the research objective |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Illness experiences of early onset of knee osteoarthritis | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • • Part of a large research series | NR | • Purposive sampling • 17 adults | • Semistructured, Individual interviews • Interview guide • Memo/field notes (observations) | • Inductive content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Three major themes and nine subthemes regarding experiences of early onset-knee osteoarthritis |

| • Australia | • Explore • Perceptions about bedside handover (new model) by nurses | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • | NR | • Purposive sampling • 30 patients | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic content analysis • (-) Data analysis | Two dominant themes and related subthemes regarding patients’ thoughts about nurses’ bedside handover |

| • Sweden | • Identify • Patterns in learning when living with diabetes | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposive sampling with variations in age and sex • 13 participants | • Semistructured, individual interviews (3 times over 3 years) | • analysis process • Inductive qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five main patterns of learning when living with diabetes for three years following diagnosis |

| • Canada | • Evaluate • Book chat intervention based on a novel | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger research project | NR | • Unspecified • 11 long-term- care staff | • Questionnaire with two open- ended questions | • Thematic content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five themes (positive comments) about the book chat with brief description |

| • Taiwan | • Explore • Facilitators and barriers to implementing smoking- cessation counseling services | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Unspecified • 16 nurse- counselors | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Inductive content analysis • Constant comparison • (-) Data saturation | Two themes and eight subthemes about facilitators and barriers described using 2-4 quotations per subtheme |

| • USA | • Identify • Educational strategies to manage disruptive behavior | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Part of a larger study | NR | • Unspecified • 9 nurses | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis procedures • (-) Data saturation | Two main themes regarding education strategies for nurse educators |

| • USA | • Explore • Experiences of difficulty resolving patient- related concerns | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Secondary analysis | NR | • Unspecified • 1932 physician, nursing, and midwifery professionals | • E-mail survey with multiple- choice and free- text responses | • Inductive thematic analysis • Descriptive statistics • (-) Data saturation | One overarching theme and four subthemes about professionals’ experiences of difficulty resolving patient-related concerns |

| • Singapore | • Explicate • Experience of quality of life for older adults | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | Parse’s human becoming paradigm | • Unspecified • 10 elderly residents | • Individual interviews • Interview questions presented (Parse) | • Unspecified analysis techniques • (-) Data saturation | Three themes presented using both participants’ language and the researcher’s language |

| • China | • Explore • Perspectives on learning about caring | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 20 nursing students | • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Four categories and associated subcategories about facilitators and challenges to learning about caring |

| • Poland | • Describe and assess • Components of the patient–nurse relationship and pediatric-ward amenities | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful, maximum variation sampling • 26 parents or caregivers and 22 children | • Individual interviews | • Qualitative content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five main topics described from the perspectives of children and parents |

| • Canada | • Evaluate • Acceptability and feasibility of hand-massage therapy | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale • Secondary to a RCT | Focused on feasibility and acceptability | • Unspecified • 40 patients | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Field notes • Video recording | • Thematic analysis for acceptability • Quantitative ratings of video items for feasibility • (-) Data analysis | Summary of data focusing on predetermined indicators of acceptability and descriptive statistics to present feasibility |

| • USA | • Understand • Challenges occurring during transitions of care | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Part of a larger study | NR | • Convenience sample • 22 nurses | • Focus groups • Interview guide | • Qualitative content analysis methods • (+) Data analysis | Three themes about challenges regarding transitions of care: |

| • Canada | • Understand • Factors that influence nurses’ retention in their current job | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 41 nurses | • Focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Directed content analysis • (+) Data saturation | Nurses’ reasons to stay and leave their current job |

| • Australia | • Extend • Understanding of caregivers’ views on advance care planning | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Grounded theory overtone | NR | • Theoretical sampling • 18 caregivers | • Semistructured focus group and individual interviews • Interview guide • Vignette technique | • Inductive, cyclic, and constant comparative analysis • (-) Data analysis | Three themes regarding caregivers’ perceptions on advance care planning |

| • USA | • Describe • Outcomes older adults with epilepsy hope to achieve in management | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Unspecified • 20 patients | • Individual interview | • Conventional content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Six main themes and associated subthemes regarding what older adults hoped to achieve in management of their epilepsy |

| • The Netherlands | • Gain • Experience of personal dignity and factors influencing it | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | Model of dignity in illness | • Maximum variation sampling • 30 nursing home residents | • Individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • Constant comparison • (+) Data saturation | The threatening effect of illness and three domains being threatened by illness in relation to participants’ experiences of personal dignity |

| • USA | • Identify and describe • Needs in mental health services and “ideal” program | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • There is a primary study | NR | • Unspecified • 52 family members | • Semistructured, individual and focus-group interviews | • “Standard content analytic procedures” with case-ordered meta-matrix • (-) Data saturation | Two main topics – (a) intervention modalities that would fit family members’ needs in mental health services and (b) topics that programs should address |

| • USA | • “What are the perceptions of staff nurses regarding palliative care…?” | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposive, convenience sampling • 18 nurses | • Semistructured and focus-group interviews • Interview guide | • Ritchie and Spencer’s framework for data analysis • (-) Data saturation | Five thematic categories and associated subcategories about nurses’ perceptions of palliative care |

| • Canada | • Describe • Experience of caring for a relative with dementia | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski ( ; ) • Secondary analysis • Phenomenological overtone | NR | • Purposive sampling • 11 bereaved family members | • Individual interviews • 27 transcripts from the primary study | • Unspecified • (-) Data saturation | Five major themes regarding the journey with dementia from the time prior to diagnosis and into bereavement |

| • Canada | • Describe Experience of fetal fibronectin testing | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • | NR | • Unspecified • 17 women | • Semistructured individual interviews • Interview guide | • Conventional content analysis • (+) Data saturation | One overarching theme, three themes, and six subthemes about women’s experiences of fetal fibronectin testing |

| • New Zealand | • Explore • Role of nurses in providing palliative and end-of-life care | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • • Part of a larger study | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 21 nurses | • Semistructured individual interviews | • Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three themes about practice nurses’ experiences in providing palliative and end-of-life care |

| • Brazil | • Understand • Experience with postnatal depression | • (+) Reference • (-) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful, criterion sampling • 15 women with postnatal depression | • Minimally structured, individual interviews | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Two themes – women’s “bad thoughts” and their four types of responses to fear of harm (with frequencies) |

| • Australia | • Understand • Experience of peripherally inserted central catheter insertion | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 10 patients | • Semistructured, individual interviews • Interview guide | • Thematic analysis • (+) Data saturation | Four themes regarding patients’ experiences of peripherally inserted central catheter insertion |

| • USA | • Discover • Context, values, and background meaning of cultural competency | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | Focused on cultural competence | • Purposive, maximum variation, and network • 20 experts | • Semistructured, individual interviews | • Within-case and across-case analysis • (-) Data saturation | Three themes regarding cultural competency |

| • USA | • Explore and describe • Cancer experience | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Unspecified • 15 patients | • Longitudinal individual interviews (4 time points) • 40 interviews | • Inductive content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Processes and themes about adolescent identify work and cancer identify work across the illness trajectory |

| • Sweden | • Explore • Experiences of giving support to patients during the transition | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | Focused on support and transition | • Unspecified (but likely purposeful sampling) • 8 nurses | • Semistructured Individual interviews • Interview guide | • Content analysis • (-) Data saturation | One theme, three main categories, and eight associated categories |

| • Taiwan | • Describe • Process of women’s recovery from stillbirth | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 21 women | • Individual interview techniques | • Inductive analytic approaches ( ) • (+) Data saturation | Three stages (themes) regarding the recovery process of Taiwanese women with stillbirth |

| • Iran | • Describe • Perspectives of causes of medication errors | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 24 nursing students | • Focus-group interviews • Observations with notes | • Content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Two main themes about nursing students’ perceptions on causes of medication errors |

| • Iran | • Explore • Image of nursing | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Purposeful sampling • 18 male nurses | • Semistructured individual, interviews • Field notes | • Content analysis • (-) Data saturation | Two main views (themes) on nursing presented with subthemes per view |

| • Spain | • Ascertain • Barriers to sexual expression | • (-) Reference • (-) Rationale | NR | • Maximum variation • 100 staff and residents | • Semistructured, individual interview | • Content analysis • (-) Data saturation | 40% of participants without identification of barriers and 60% with seven most cited barriers to sexual expression in the long-term care setting |

| • Canada | • Explore • Perceptions of empowerment in academic nursing environments | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski ( , ) | Theories of structural power in organizations and psychological empowerment | • Unspecified • 8 clinical instructors | • Semistructured, individual • interview guide | • Unspecified (but used pre-determined concepts) • (+) Data saturation | Structural empowerment and psychological empowerment described using predetermined concepts |

| • China | • Investigate • Meaning of life and health experience with chronic illness | • (+) Reference • (+) Rationale • Sandelowski ( , ) | Positive health philosophy | • Purposive, convenience sampling • 11 patients | • Individual interviews • Observations of daily behavior with field notes | • Thematic analysis • (-) Data saturation | Four themes regarding the meaning of life and health when living with chronic illnesses |

Note . NR = not reported

Quality Appraisal Results

Justification for use of a QD design was evident in close to half (47.3%) of the 55 publications. While most researchers clearly described recruitment strategies (80%) and data collection methods (100%), justification for how the study setting was selected was only identified in 38.2% of the articles and almost 75% of the articles did not include any reason for the choice of data collection methods (e.g., focus-group interviews). In the vast majority (90.9%) of the articles, researchers did not explain their involvement and positionality during the process of recruitment and data collection or during data analysis (63.6%). Ethical standards were reported in greater than 89% of all articles and most articles included an in-depth description of data analysis (83.6%) and development of categories or themes (92.7%). Finally, all researchers clearly stated their findings in relation to research questions/objectives. Researchers of 83.3% of the articles discussed the credibility of their findings (see Table 1 ).

Research Objectives

In statements of study objectives and/or questions, the most frequently used verbs were “explore” ( n = 22) and “describe” ( n = 17). Researchers also used “identify” ( n = 3), “understand” ( n = 4), or “investigate” ( n = 2). Most articles focused on participants’ experiences related to certain phenomena ( n = 18), facilitators/challenges/factors/reasons ( n = 14), perceptions about specific care/nursing practice/interventions ( n = 11), and knowledge/attitudes/beliefs ( n = 3).

Design Justification

A total of 30 articles included references for QD. The most frequently cited references ( n = 23) were “Whatever happened to qualitative description?” ( Sandelowski, 2000 ) and “What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited” ( Sandelowski, 2010 ). Other references cited included “Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research?” ( Neergaard et al., 2009 ), “Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research” ( Pope & Mays, 1995 ), and general research textbooks ( Polit & Beck, 2004 , 2012 ).

In 26 articles (and not necessarily the same as those citing specific references to QD), researchers provided a rationale for selecting QD. Most researchers chose QD because this approach aims to produce a straight description and comprehensive summary of the phenomenon of interest using participants’ language and staying close to the data (or using low inference).

Authors of two articles distinctly stated a QD design, yet also acknowledged grounded-theory or phenomenological overtones by adopting some techniques from these qualitative traditions ( Michael, O'Callaghan, Baird, Hiscock, & Clayton, 2014 ; Peacock, Hammond-Collins, & Forbes, 2014 ). For example, Michael et al. (2014 , p. 1066) reported:

The research used a qualitative descriptive design with grounded theory overtones ( Sandelowski, 2000 ). We sought to provide a comprehensive summary of participants’ views through theoretical sampling; multiple data sources (focus groups [FGs] and interviews); inductive, cyclic, and constant comparative analysis; and condensation of data into thematic representations ( Corbin & Strauss, 1990 , 2008 ).

Authors of four additional articles included language suggestive of a grounded-theory or phenomenological tradition, e.g., by employing a constant comparison technique or translating themes stated in participants’ language into the primary language of the researchers during data analysis ( Asemani et al., 2014 ; Li, Lee, Chen, Jeng, & Chen, 2014 ; Ma, 2014 ; Soule, 2014 ). Additionally, Li et al. (2014) specifically reported use of a grounded-theory approach.

Theoretical or Philosophical Framework