What is “Assignment of Income” Under the Tax Law?

Gross income is taxed to the individual who earns it or to owner of property that generates the income. Under the so-called “assignment of income doctrine,” a taxpayer may not avoid tax by assigning the right to income to another.

Specifically, the assignment of income doctrine holds that a taxpayer who earns income from services that the taxpayer performs or property that the taxpayer owns generally cannot avoid liability for tax on that income by assigning it to another person or entity. The doctrine is frequently applied to assignments to creditors, controlled entities, family trusts and charities.

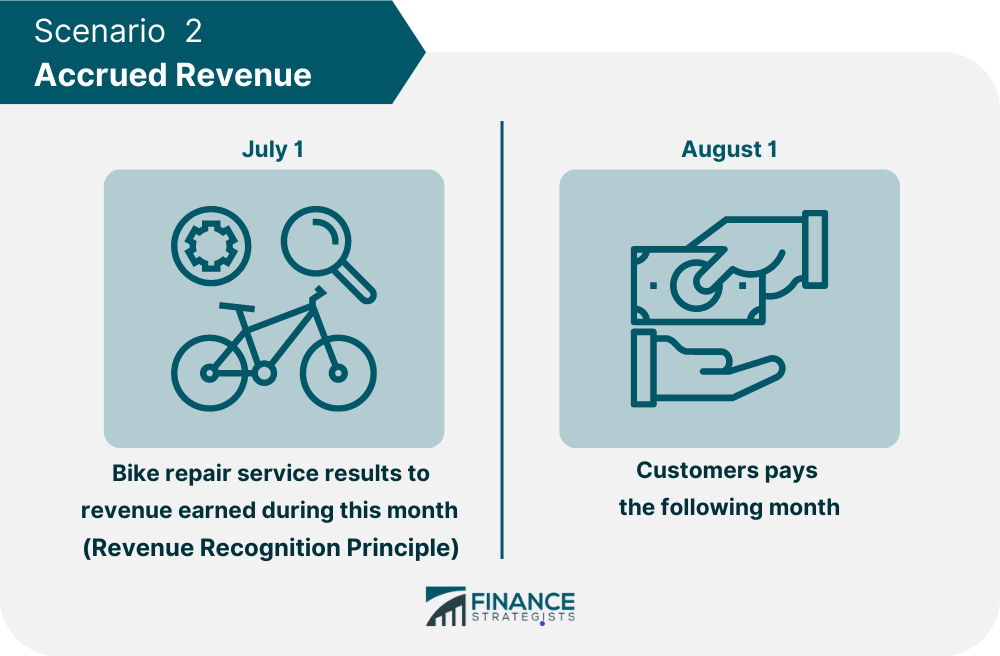

A taxpayer cannot, for tax purposes, assign income that has already accrued from property the taxpayer owns. This aspect of the assignment of income doctrine is often applied to interest, dividends, rents, royalties, and trust income. And, under the same rationale, an assignment of an interest in a lottery ticket is effective only if it occurs before the ticket is ascertained to be a winning ticket.

However, a taxpayer can shift liability for capital gains on property not yet sold by making a bona fide gift of the underlying property. In that case, the donee of a gift of securities takes the “carryover” basis of the donor.

For example, shares now valued at $50 gifted to a donee in which the donor has a tax basis of $10, would yield a taxable gain to the donee of its eventual sale price less the $10 carryover basis. The donor escapes income tax on any of the appreciation.

For guidance on this issue, please contact our professionals at 315.242.1120 or [email protected] .

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Privacy overview.

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.

- [ August 28, 2024 ] LPSA Thematic Working Group on Gender Equity & Women’s Empowerment – Open Meeting – February 2025 LPSA Updates

- [ August 27, 2024 ] LPSA Asia Working Group – Knowledge Sharing Meeting – September 2024 LPSA Updates

- [ August 23, 2024 ] Advancing Sustainable Development Goals at Cambodia’s Subnational Levels ADB

- [ August 22, 2024 ] Financing strategies for inclusive urban development Cities and urban development

- [ August 12, 2024 ] Navigating conflict and fostering cooperation in fiscal federalism Decentralization

3. Revenue Assignments and Local Revenue Administration

3.1 relevance of revenue assignments and own revenue sources.

Although revenue sources are often less decentralized than expenditure responsibilities, tax revenues are an important source of income for subnational governments, accounting for one-third of total subnational government revenue or roughly 3.3 percent of GDP on average (OECD/UCLG 2019: 71, 77). [12] Other (non-tax) own revenue sources such as user charges, fees, and property income, account for another 11 percent of subnational revenue or approximately an additional one percent of GDP. Naturally, the importance of subnational own source revenues, and the breakdown between the different types of own source revenues, vary considerably from one country to another.

3.2 An overview of devolved (local government) revenue assignments and administration

The economics of local taxation under fiscal federalism. Unlike central government taxes (which are generally defined as compulsory payments to the central government for which there is no quid pro quo ), local government taxes in a well-designed intergovernmental fiscal system are more appropriately seen as quasi-user fees for locally-provided services. Indeed, in order to maximize social welfare and improve the allocative efficiency of resources in a decentralized public sector, the goal of local taxation is not to maximize the volume of local revenue collections, but rather, to ensure that local taxpayers in different local jurisdictions only pay local taxes commensurate to the level of locally-provided services that they demand from and get supplied by their local government. [13]

In line with the concept that “finance should follow function,” local taxes and user fees should be considered appropriate funding sources to pay for exclusive local government functions—where the benefits of local government services largely or wholly are received by residents of the local government jurisdiction itself. As noted in Section 3.3 below, to the extent that concurrent functions partially or largely benefit residents outside the local government jurisdiction, it would be conceptually more appropriate to fund such concurrent government functions in part or in whole through intergovernmental fiscal transfers.

Assignment of own revenue sources. Public finance theory prescribes a number of rather stringent conditions to determine which taxes and revenue sources should be considered good candidates for assignment to the local or regional level (Bird 2000). In fact, in line with the subsidiarity principle, the only taxes and revenue sources that could be suitably collected by subnational governments are revenue sources that (a) can be administered efficiently at the local or regional level; (b) are imposed solely or mainly on local residents; [14] and (c) do not raise problems of harmonization or competition between subnational governments or between subnational and national governments. [15]

The only major revenue source usually seen as passing these stringent tests for assignment to the local level is the property tax; the second-largest category of local revenues in many countries tends to be user fees and charges. In fact, for all other high-yielding tax sources—including personal income taxes, corporate income taxes, value-added taxes or sales taxes, and trade taxes—it could reasonably be argued that the central government is the lowest level of government able to collect those revenue sources without causing inefficiency. As a result, it is no surprise that the vast majority of revenues in most countries is collected by the central government.

Tax autonomy and the assignment of shared revenue sources. Because the practical scope for autonomous subnational taxation—in a way that ensures efficiency—is limited, some countries assign local governments the right to collect different revenue sources, while limiting the control of subnational governments over one or more aspects of these taxes. This results in a spectrum ranging from own source revenues fully under the control of local decision-makers to tax sharing arrangements over which local governments have no control (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 A taxonomy of tax autonomy (OECD)

| a.1 | The recipient subcentral government (SCG) sets the tax rate and any tax reliefs without needing to consult a HLG. |

| a.2 | The recipient SCG sets the rate and any reliefs after consulting a HLG. |

| b.1 | The recipient SCG sets the tax rate, and a HLG does not set upper or lower limits on the rate chosen. |

| b.2 | The recipient SCG sets the tax rate, and a HLG does sets upper and/or lower limits on the rate chosen. |

| c.1 | The recipient SCG sets tax reliefs – but it sets tax allowances only. |

| c.2 | The recipient SCG sets tax reliefs – but it sets tax credits only. |

| c.3 | The recipient SCG sets tax reliefs – and it sets both tax allowances and tax credits. |

| d.1 | Tax sharing arrangement in which the SCGs determine the revenue split. |

| d.2 | Tax sharing arrangement in which the revenue split can be changed only with the consent of SCGs. |

| d.3 | Tax sharing arrangement in which the revenue split is determined in HLG legislation (less frequently than once a year). |

| d.4 | Tax -sharing arrangement in which the revenue split is determined annually by a HLG. |

| e. | Other cases in which the central government sets the rate and base of the SCG tax. |

| f. | None of the above categories of a, b, c, d, or e applies. |

For instance, central legislation might provide local governments with the power to collect a certain tax – a corporate income tax, for example – while defining the base of this tax uniformly across the entire national territory in order to limit the administrative burden of local taxation on taxpayers. Similarly, central legislation may limit the tax rates that local governments may impose on local taxpayers for different taxes – for example, by setting lower and upper bounds – in order to prevent territorial or vertical tax competition. Alternatively, central authorities may simply decide to share the revenue collected from certain revenue sources with subnational governments. For example, this may be done on a derivation basis (based on where the revenue is collected) without giving subnational governments any control over the tax base, the tax rate, or the sharing rate. [16]

In addition to property taxation, another area of focus for subnational revenue mobilization efforts could be on user charges and fees. The ability of local governments to collect these types of revenues depends considerably on the assignment of functional powers; local institutions’ ability to deliver local services in way that provides value-for-money; and on the capacity and willingness of users to pay for these services.

3.3 An overview of non-devolved revenue assignments

Traditionally, the discussion of revenue decentralization and the assignment of revenue powers has focused almost exclusively on the local property tax and any other local tax and non-tax revenue funds that are part of the local government budget. Virtually no systematic attention has been paid to the assignment of revenue powers to non-devolved actors in the intergovernmental system. This includes any discussion or analysis of revenues collected by national parastatal entities, authorities and funds—revenues collected by entities that are funders or providers of delegated services. Also overlooked are revenues collected by local government-owned public companies, delegated service providers, and other “last mile” providers such as local water utilities, transit companies, or fee-collecting local health facilities. All these revenues are typically excluded from measures of revenue decentralization, as traditional measures of revenue decentralization focus exclusively on national government revenue collections and local government revenue collections. Any revenues collected by off-budget entities at both the central government and local government levels are often simply overlooked. [17]

While the reliance on non-devolved revenue sources is likely to vary significantly from country to country and from sector to sector, these revenues are likely to play a much more significant role than commonly recognized. For instance, in the provision of public health services, how much do local health facilities collect in terms of user fees or private or social health insurance payments in a way that is not captured by local government accounts? In turn, how much revenue do national or local health insurance schemes collect from the public? Similarly, to the extent that schools collect school fees from parents and/or to the extent that school committees or parent-teacher committees, as quasi-public entities, contribute to the provision of primary education, how significant is this funding? [18]

In the provision of water and sanitation services, what is the total revenue collected each year and subsequently spent for recurrent operation and capital purposes by off-budget urban water utilities? Similarly, in rural areas, what revenues are collected by water user committees which, in many countries, serve as the de facto provider of rural water services? Both of these questions should be answered fully to get a comprehensive picture of water and sanitation revenues. It is not unusual, however, for the accounting of water and sanitation revenue and spending to focus exclusively on capital investment spending, and to ignore the revenues and expenditures needed to operate and maintain water and sanitation infrastructure.

Likewise, to the extent that roads and other transportation infrastructure may be operated in an off-budget manner by a national road fund (often funded by a fuel levy) or by dedicated transportation authorities or public-private partnerships (PPPs), what are the fuel levies or road tolls that are collected by these authorities or entities that operate and/or maintain public sector roads or bridges?

3.4 Common obstacles in domestic revenue mobilization and subnational revenue administration: technical challenges

Local own source revenues are seen by many as a preferred source of funding for local government services. This is not only because there is a stronger conceptual link between the benefits and costs of locally-provided services, [19] but also because local taxpayers are expected to exert stronger oversight over the efficient spending of their own local tax contributions. Furthermore, revenue decentralization gives subnational governments a fiscal stake in the economic success of their jurisdictions. As a result of these factors, the failure to decentralize revenue powers while decentralizing expenditure responsibilities is generally assumed to result in greater local fiscal indiscipline and risk taking.

But, the evidence on this point is mixed. Given the fact that the collection of most major revenue sources—with the exception of property taxes—is generally assigned to the central government in line with the subsidiarity principle in revenue administration, virtually every country in the world faces a significant primary vertical fiscal imbalance. In many countries, the assignment of shared revenue sources on a derivation basis, or the introduction of local surtaxes or piggy-back taxes is often able to reduce the vertical fiscal gap in a way that provides resources to subnational governments without the potential inefficiencies associated with full revenue decentralization (Hunter 1977).

Nonetheless, lackluster collection of local taxes and other own source revenues in many local jurisdictions is common, particularly in developing and transition countries. Analyses of local revenue performance frequently attribute the lack of local revenue effort to an amorphous “weak local revenue administration” which, in turn, is often attributed to a “lack of local political will.” Instead, weak local revenue performance is often caused by a combination of factors, including the fact that local governments are assigned unpopular taxes that are relatively costly to collect, and have weak enforcement powers and weak political incentives and/or the absence of hard budget constraints. [20]

As a result, most real-world interventions related to revenue assignment and local revenues are intended to ensure that subnational governments administer the limited revenue instruments assigned to them as efficiently as possible. Efforts to improve local property tax administration (particularly in urban areas), often play on outsized role in development partner interventions related to local government revenues (Kelly, White, and Anand 2020).

3.5 Political economy considerations: common obstacles in revenue assignments

Empowering intergovernmental (fiscal) systems: revenue assignments. Public sector revenues tend to be much less decentralized when compared to public sector expenditures. As noted in Section 2, when we apply the subsidiarity principle to the function of public taxation and revenue administration, most revenues are efficiently collected at the national level. An additional reason for this pattern is that political economy forces cause revenues to be highly centralized. Most Finance Ministers will be hesitant to give away high-yielding revenue instruments to subnational governments, and thereby reduce the ability of the national fiscus to ensure macro-fiscal stability.

Furthermore, it is common for central government politicians—ahead of their next election—to abolish local taxes that are unpopular with the electorate, allowing central politicians to cut taxes for voters without a negative impact on their own (central) budget. More often than not, these local revenue sources are reinstated after the election, when locally elected leaders appeal to the national party that local revenues are an important foundation for the financial survival of local governments.

Efficient, inclusive and responsive revenue assignment. In response to news that local governments are collecting only x percent of the revenue that they could be collecting (where x is a small number, sometimes even as small as 10 percent), it is not unusual for national-level politicians or policy researchers studying local revenue administration to condemn local government officials for lacking the political will to collect own source revenues.

Such criticism may or may not be warranted, and if nothing else, it does not necessarily point to a problem with local tax administration. It is useful to start by acknowledging the political economy argument that local revenue collections are not intended to be maximized, but rather, that local revenue collections are optimal where the marginal cost to local taxpayers of additional taxation equals the marginal benefits from additional public services. In an effectively decentralized system, if the chain of accountability is working, locally elected officials are the arbiters of the level of local taxation at which this optimum is achieved. The “lack of political will” may simply reflect a rational political response to a situation where it might be politically easier for a mayor to get additional resources as a special grant from central government compared to collecting from local constituents. Local leaders may also exhibit a lack of political will to collect own source revenues results if the efficiency or responsiveness of local government spending is relatively low. A low level of lack of political will is only a real concern if local politicians are setting effective tax rates – through a combination of formal tax rates and weak revenue administration and enforcement – that result in a level of local taxation that falls below what is considered optimal by local constituents.

A bigger concern may actually be when predatory local taxation, the opposite of inadequate revenue mobilization, occurs. [21] Another serious problem occurs when the local government administers local taxes and revenues in a patently inequitable manner for example, enforcing taxes on political opponents, but not on political supporters, or when pervasive inefficiency or corruption exists in local tax administration. It is not just local politicians who are to blame at the local level for weak local revenue administration. As long as local politicians and taxpayers are satisfied to remain at an equilibrium of low taxation and low service delivery performance, the tax administration apparatus does not face strong incentives to improve its collection performance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, most local revenue mobilization efforts focus on other local administration improvement efforts such as improving land administration and property valuation, while basic revenue collection activities, such as billing systems and enforcement and collection of arrears, are frequently overlooked.

Engaged civil society, citizens, and business community: revenue assignments. While the long term success of any public sector depends on its ability to generate revenues from which to fund public sector expenditure, it is equally important to consider the perspective of the (local) taxpayer in determining the assignment of revenue sources and the optimal level of taxation at different levels. In most countries, even under the best of circumstances, taxpayers are unlikely to pay their (local) taxes if payment can be avoided without negative consequences. Tax collection and enforcement issues aside, local taxpayers’ willingness to pay taxes in return for local public services is likely to be limited if the local government’s decision making is unresponsive, or if the local government’s capacity to efficiently deliver services is weak.

A final political economy consideration regarding local revenue collection is how the money gets spent. Wealthier taxpayers might be willing to pay local taxes if they perceive benefits from higher local taxes. However, the willingness of wealthy taxpayers to support pro-poor local services is often limited by the strength of local social contract. Thus, local revenue compliance may decline over time when local governments pursue redistributive policies beyond the level supported by those contributing most to the local treasury.

| – Richard Bird: . – Hansjörg Blöchliger and Maurice Nettley: . – Catherine Farvacque-Vitkovic and Mihaly Kopanyi: . – Roy Kelly, Roland White, and Aanchal Anand: . |

[12] According to the OECD definition used, tax revenue is not made up only of own-source taxes, but includes shared taxes as well. Even with this more expansive definition of subnational government tax revenues, subnational taxes account for only 14.9% of public tax revenues. As discussed further below, the main funding source for subnational governments (on average) is formed by intergovernmental fiscal transfers.

[13] In this sense, decentralized provision of locally-provided goods mimics market-provision of private goods, where consumers opt to consume a private good up to the point where the marginal benefit from the good equals the marginal cost. Basic economic analysis (for instance, in the context of a representative agent or median voter model) suggests that in addition to the local governments’ responsiveness to constituent preferences, other key determinants of the optimal level of local taxation include the relative price (i.e., efficiency or inefficiency) of local service provision and the presence or absence of general-purpose grants.

[14] An efficient assignment of revenue sources should prevent the possibility of “tax exporting”, by which a local or regional government is able to impose a tax burden on residents outside its jurisdiction. For this purpose, it is important to recognize that the burden of a tax may be borne by someone other than the person who pays the tax. For instance, while import duties are paid by the importer, the actual burden of the tax is typically borne by the final consumer (because the cost of the import duty raises the final sales price). As such, assigning the power to levy import duties to local governments (or the practice of charging an octroi on the trans-shipment of goods through a local jurisdiction) would effectively allow local government to tax the residents of other local governments without providing commensurate services to them.

[15] Tax competition between different subnational jurisdictions as well as duplicative taxation by different levels (resulting in cumulative high marginal tax rates) would have the potential for economic distortion and inefficiency.

[16] As noted in Section 3.3 below, economists consider that such shared revenues are in fact intergovernmental fiscal transfers. Nonetheless, it is not unusual for the domestic Chart of Accounts to register such shared revenues as own source revenues rather than as intergovernmental revenues in order to give the appearance of tax autonomy.

[17] Compared to other sectors, the health sector offers a positive example, as the World Health Organization’s accounting of Total Health Expenditures seeks to incorporate different funding flows, including public sources (government spending); private (out of pocket) spending; social health insurance; and donor organization spending. Despite the extensive guidance in the sector, however, it is often still difficult to entangle how much is being collected and spent of health services, and, by whom, at the subnational level.

[18] Boex and Vaillancourt (2014) point to the case of education spending in Madagascar. Primary education is formally a central government responsibility provided in a deconcentrated fashion following a classic French model. In 2010‐2011, centrally hired primary school teachers (either as permanent civil servants or contractual employees) accounted for only 32% of all public school teachers; of the remaining 68% (called FRAM teachers), 48% were hired and paid in part by parental committees and in part by a subsidy paid directly to teachers by the central government and 20% were hired/paid by parent’s committees, often with in kind payment (rice).

[19] The link between local taxes and local expenditures and accountability at the local level is called Wicksellian connection. See Bird and Slack (2013).

[20] National revenue authorities don’t necessarily do any better job when asked to collect local revenues (Fjeldstad, Ali, and Katera 2019).

[21] The definition of predatory taxation is often in the eye of the beholder. However, most people would be concerned about the efficiency and equity of local revenue assignments if a major share of local revenues would benefit tax collectors, or if these local revenues are mainly used to pay for the sitting allowance of local officials.

Copyright 2015-2024. Local Public Sector Alliance.

An official website of the United States Government

- Kreyòl ayisyen

- Search Toggle search Search Include Historical Content - Any - No Include Historical Content - Any - No Search

- Menu Toggle menu

- INFORMATION FOR…

- Individuals

- Business & Self Employed

- Charities and Nonprofits

- International Taxpayers

- Federal State and Local Governments

- Indian Tribal Governments

- Tax Exempt Bonds

- FILING FOR INDIVIDUALS

- How to File

- When to File

- Where to File

- Update Your Information

- Get Your Tax Record

- Apply for an Employer ID Number (EIN)

- Check Your Amended Return Status

- Get an Identity Protection PIN (IP PIN)

- File Your Taxes for Free

- Bank Account (Direct Pay)

- Payment Plan (Installment Agreement)

- Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS)

- Your Online Account

- Tax Withholding Estimator

- Estimated Taxes

- Where's My Refund

- What to Expect

- Direct Deposit

- Reduced Refunds

- Amend Return

Credits & Deductions

- INFORMATION FOR...

- Businesses & Self-Employed

- Earned Income Credit (EITC)

- Child Tax Credit

- Clean Energy and Vehicle Credits

- Standard Deduction

- Retirement Plans

Forms & Instructions

- POPULAR FORMS & INSTRUCTIONS

- Form 1040 Instructions

- Form 4506-T

- POPULAR FOR TAX PROS

- Form 1040-X

- Circular 230

EXEMPT ORGANIZATIONS

Administrative, the irs mission, introduction, ct. d. 2080, rev. rul. 2005-23, rev. proc. 2005-22, reg-147195-04, announcement 2005-24, announcement 2005-25, definition of terms, abbreviations, numerical finding list, finding list of current actions on previously published items, internal revenue bulletin, cumulative bulletins, access the internal revenue bulletin on the internet, internal revenue bulletins on cd-rom, how to order, we welcome comments about the internal revenue bulletin, internal revenue bulletin: 2005-15.

April 11, 2005

Highlights of This Issue

These synopses are intended only as aids to the reader in identifying the subject matter covered. They may not be relied upon as authoritative interpretations.

Ct. D. 2080 Ct. D. 2080

Gross income; litigant’s recovery includes attorney’s contingent fee. The Supreme Court holds that when a litigant’s recovery constitutes income, the litigant’s income includes the portion of the recovery paid to the attorney as a contingent fee. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v . Banks.

Rev. Rul. 2005-23 Rev. Rul. 2005-23

Federal rates; adjusted federal rates; adjusted federal long-term rate and the long-term exempt rate. For purposes of sections 382, 642, 1274, 1288, and other sections of the Code, tables set forth the rates for April 2005.

T.D. 9190 T.D. 9190

Final regulations under section 664 of the Code concern the ordering rule of regulations section 1.664-1(d). The regulations provide rules for characterizing the income distributions from charitable remainder trusts (CRTs) when the income is subject to different federal income tax rates. The regulations reflect changes made to income tax rates, including capital gains and certain dividends, by the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003.

T.D. 9191 T.D. 9191

Final regulations amend regulations under section 163(d) of the Code to provide the rules relating to how and when taxpayers may elect to take qualified dividend income into account as investment income for purposes of calculating the deduction for investment income expense.

T.D. 9192 T.D. 9192

Final regulations under section 1502 of the Code provide guidance concerning the determination of the tax attributes that are available for reduction and the method for reducing those attributes when a member of a consolidated group excludes discharge of indebtedness income from gross income under section 108.

T.D. 9193 T.D. 9193

Final regulations under section 704 of the Code clarify that if section 704(c) property is sold for an installment obligation, the installment obligation is treated as the contributed property for purposes of applying sections 704(c) and 737. Likewise, if the contributed property is a contract, such as an option to acquire property, the property acquired pursuant to the contract is treated as the contributed property for these purposes.

Announcement 2005-25 Announcement 2005-25

This document contains a correction to final regulations (T.D. 9187, 2005-13 I.R.B. 778) that disallow certain losses recognized on sales of subsidiary stock by members of a consolidated group.

Announcement 2005-24 Announcement 2005-24

A list is provided of organizations now classified as private foundations.

T.D. 9188 T.D. 9188

Temporary and proposed regulations under section 6103 of the Code set forth changes to the list of items of return information that the IRS discloses to the Department of Commerce for the purpose of structuring censuses and national economic accounts and conducting related statistical activities authorized by law.

REG–147195–04 REG–147195–04

Rev. proc. 2005-22 rev. proc. 2005-22.

Qualified mortgage bonds; mortgage credit certificates; national median gross income. Guidance is provided concerning the use of the national and area median gross income figures by issuers of qualified mortgage bonds and mortgage credit certificates in determining the housing cost/income ratio described in section 143(f) of the Code. Rev. Proc. 2004-24 obsoleted.

Provide America’s taxpayers top quality service by helping them understand and meet their tax responsibilities and by applying the tax law with integrity and fairness to all.

The Internal Revenue Bulletin is the authoritative instrument of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for announcing official rulings and procedures of the Internal Revenue Service and for publishing Treasury Decisions, Executive Orders, Tax Conventions, legislation, court decisions, and other items of general interest. It is published weekly and may be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents on a subscription basis. Bulletin contents are compiled semiannually into Cumulative Bulletins, which are sold on a single-copy basis.

It is the policy of the Service to publish in the Bulletin all substantive rulings necessary to promote a uniform application of the tax laws, including all rulings that supersede, revoke, modify, or amend any of those previously published in the Bulletin. All published rulings apply retroactively unless otherwise indicated. Procedures relating solely to matters of internal management are not published; however, statements of internal practices and procedures that affect the rights and duties of taxpayers are published.

Revenue rulings represent the conclusions of the Service on the application of the law to the pivotal facts stated in the revenue ruling. In those based on positions taken in rulings to taxpayers or technical advice to Service field offices, identifying details and information of a confidential nature are deleted to prevent unwarranted invasions of privacy and to comply with statutory requirements.

Rulings and procedures reported in the Bulletin do not have the force and effect of Treasury Department Regulations, but they may be used as precedents. Unpublished rulings will not be relied on, used, or cited as precedents by Service personnel in the disposition of other cases. In applying published rulings and procedures, the effect of subsequent legislation, regulations, court decisions, rulings, and procedures must be considered, and Service personnel and others concerned are cautioned against reaching the same conclusions in other cases unless the facts and circumstances are substantially the same.

The Bulletin is divided into four parts as follows:

Part I.—1986 Code. This part includes rulings and decisions based on provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986.

Part II.—Treaties and Tax Legislation. This part is divided into two subparts as follows: Subpart A, Tax Conventions and Other Related Items, and Subpart B, Legislation and Related Committee Reports.

Part III.—Administrative, Procedural, and Miscellaneous. To the extent practicable, pertinent cross references to these subjects are contained in the other Parts and Subparts. Also included in this part are Bank Secrecy Act Administrative Rulings. Bank Secrecy Act Administrative Rulings are issued by the Department of the Treasury’s Office of the Assistant Secretary (Enforcement).

Part IV.—Items of General Interest. This part includes notices of proposed rulemakings, disbarment and suspension lists, and announcements.

The last Bulletin for each month includes a cumulative index for the matters published during the preceding months. These monthly indexes are cumulated on a semiannual basis, and are published in the last Bulletin of each semiannual period.

Part I. Rulings and Decisions Under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986

Commissioner of internal revenue v . banks, certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the sixth circuit.

January 24, 2005 [1]

Respondent Banks settled his federal employment discrimination suit against a California state agency and respondent Banaitis settled his Oregon state case against his former employer, but neither included fees paid to their attorneys under contingent-fee agreements as gross income on their federal income tax returns. In each case petitioner Commissioner of Internal Revenue issued a notice of deficiency, which the Tax Court upheld. In Banks’ case, the Sixth Circuit reversed in part, finding that the amount Banks paid to his attorney was not includable as gross income. In Banaitis’ case, the Ninth Circuit found that because Oregon law grants attorneys a superior lien in the contingent-fee portion of any recovery, that part of Banaitis’ settlement was not includable as gross income.

Held : When a litigant’s recovery constitutes income, the litigant’s income includes the portion of the recovery paid to the attorney as a contingent fee. Pp. 5-12.

(a) Two preliminary observations help clarify why this issue is of consequence. First, taking the legal expenses as miscellaneous itemized deductions would have been of no help to respondents because the Alternative Minimum Tax establishes a tax liability floor and does not allow such deductions. Second, the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004—which amended the Internal Revenue Code to allow a taxpayer, in computing adjusted gross income, to deduct attorney’s fees such as those at issue—does not apply here because it was passed after these cases arose and is not retroactive. Pp. 5-6.

(b) The Code defines “gross income” broadly to include all economic gains not otherwise exempted. Under the anticipatory assignment of income doctrine, a taxpayer cannot exclude an economic gain from gross income by assigning the gain in advance to another party, e.g., Lucas v. Earl , 281 U.S. 111, because gains should be taxed “to those who earn them,” id ., at 114. The doctrine is meant to prevent taxpayers from avoiding taxation through arrangements and contracts devised to prevent income from vesting in the one who earned it. Id ., at 115. Because the rule is preventative and motivated by administrative and substantive concerns, this Court does not inquire whether any particular assignment has a discernible tax avoidance purpose. Pp. 6-7.

(c) The Court agrees with the Commissioner that a contingent-fee agreement should be viewed as an anticipatory assignment to the attorney of a portion of the client’s income from any litigation recovery. In an ordinary case, attribution of income is resolved by asking whether a taxpayer exercises complete dominion over the income in question. However, in the context of anticipatory assignments, where the assignor may not have dominion over the income at the moment of receipt, the question is whether the assignor retains dominion over the income-generating asset. Looking to such control preserves the principle that income should be taxed to the party who earns the income and enjoys the consequent benefits. In the case of a litigation recovery, the income-generating asset is the cause of action derived from the plaintiff’s legal injury. The plaintiff retains dominion over this asset throughout the litigation. Respondents’ counterarguments are rejected. The legal claim’s value may be speculative at the moment of the assignment, but the anticipatory assignment doctrine is not limited to instances when the precise dollar value of the assigned income is known in advance. In these cases, the taxpayer retained control over the asset, diverted some of the income produced to another party, and realized a benefit by doing so. Also rejected is respondents’ suggestion that the attorney-client relationship be treated as a sort of business partnership or joint venture for tax purposes. In fact, that relationship is a quintessential principal-agent relationship, for the client retains ultimate dominion and control over the underlying claim. The attorney can make tactical decisions without consulting the client, but the client still must determine whether to settle or proceed to judgment and make, as well, other critical decisions. The attorney is an agent who is duty bound to act in the principal’s interests, and so it is appropriate to treat the full recovery amount as income to the principal. This rule applies regardless of whether the attorney-client contract or state law confers any special rights or protections on the attorney, so long as such protections do not alter the relationship’s fundamental principal-agent character. The Court declines to comment on other theories proposed by respondents and their amici , which were not advanced in earlier stages of the litigation or examined by the Courts of Appeals. Pp. 7-10.

(d) This Court need not address Banks’ contention that application of the anticipatory assignment principle would be inconsistent with the purpose of statutory fee-shifting provisions, such as those applicable in his case brought under 42 U.S.C. Secs. 1981, 1983, and 2000(e) et seq . He settled his case, and the fee paid to his attorney was calculated based solely on the contingent-fee contract. There was no court-ordered fee award or any indication in his contract with his attorney or the settlement that the contingent fee paid was in lieu of statutory fees that might otherwise have been recovered. Also, the American Jobs Creation Act redresses the concern for many, perhaps most, claims governed by fee-shifting statutes. P. 11.

No. 03-892, 345 F.3d 373; No. 03-907, 340 F.3d 1074, reversed and remanded.

KENNEDY, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which all other Members joined, except REHNQUIST, C.J., who took no part in the decision of the cases.

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, PETITIONER v . JOHN W. BANKS, II

On writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the sixth circuit, commissioner of internal revenue, petitioner v . sigitas j. banaitis, on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the ninth circuit.

January 24, 2005

JUSTICE KENNEDY delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question in these consolidated cases is whether the portion of a money judgment or settlement paid to a plaintiff’s attorney under a contingent-fee agreement is income to the plaintiff under the Internal Revenue Code, 26 U.S.C. Sec. 1 et seq . (2000 ed. and Supp. I). The issue divides the courts of appeals. In one of the instant cases, Banks v. Commissioner , 345 F.3d 373 (2003), the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held the contingent-fee portion of a litigation recovery is not included in the plaintiff’s gross income. The Courts of Appeals for the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits also adhere to this view, relying on the holding, over Judge Wisdom’s dissent, in Cotnam v. Commissioner , 263 F.2d 119, 125-126 (CA5 1959). Srivastava v. Commissioner , 220 F.3d 353, 363-365 (CA5 2000); Foster v. United States , 249 F.3d 1275, 1279-1280 (CA11 2001). In the other case under review, Banaitis v. Commissioner , 340 F.3d 1074 (2003), the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that the portion of the recovery paid to the attorney as a contingent fee is excluded from the plaintiff’s gross income if state law gives the plaintiff’s attorney a special property interest in the fee, but not otherwise. Six Courts of Appeals have held the entire litigation recovery, including the portion paid to an attorney as a contingent fee, is income to the plaintiff. Some of these Courts of Appeals discuss state law, but little of their analysis appears to turn on this factor. Raymond v. United States , 355 F.3d 107, 113-116 (CA2 2004); Kenseth v. Commissioner , 259 F.3d 881, 883-884 (CA7 2001); Baylin v. United States , 43 F.3d 1451, 1454-1455 (CA Fed. 1995). Other Courts of Appeals have been explicit that the fee portion of the recovery is always income to the plaintiff regardless of the nuances of state law. O’Brien v. Commissioner , 38 T.C. 707, 712 (1962), aff’d, 319 F.2d 532 (CA3 1963) ( per curiam ); Young v. Commissioner , 240 F.3d 369, 377-379 (CA4 2001); Hukkanen-Campbell v. Commissioner , 274 F.3d 1312, 1313-1314 (CA10 2001). We granted certiorari to resolve the conflict. 541 U.S. 958 (2004).

We hold that, as a general rule, when a litigant’s recovery constitutes income, the litigant’s income includes the portion of the recovery paid to the attorney as a contingent fee. We reverse the decisions of the Courts of Appeals for the Sixth and Ninth Circuits.

A. Commissioner v. Banks

In 1986, respondent John W. Banks, II, was fired from his job as an educational consultant with the California Department of Education. He retained an attorney on a contingent-fee basis and filed a civil suit against the employer in a United States District Court. The complaint alleged employment discrimination in violation of 42 U.S.C. Secs. 1981 and 1983, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e et seq ., and Cal. Govt. Code Ann. Sec. 12965 (West 1986). The original complaint asserted various additional claims under state law, but Banks later abandoned these. After trial commenced in 1990, the parties settled for $464,000. Banks paid $150,000 of this amount to his attorney pursuant to the fee agreement.

Banks did not include any of the $464,000 in settlement proceeds as gross income in his 1990 federal income tax return. In 1997 the Commissioner of Internal Revenue issued Banks a notice of deficiency for the 1990 tax year. The Tax Court upheld the Commissioner’s determination, finding that all the settlement proceeds, including the $150,000 Banks had paid to his attorney, must be included in Banks’ gross income.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed in part. 345 F.3d 373 (2003). It agreed the net amount received by Banks was included in gross income but not the amount paid to the attorney. Relying on its prior decision in Estate of Clarks v. Commissioner, 202 F.3d 854 (2000), the court held the contingent-fee agreement was not an anticipatory assignment of Banks’ income because the litigation recovery was not already earned, vested, or even relatively certain to be paid when the contingent-fee contract was made. A contingent-fee arrangement, the court reasoned, is more like a partial assignment of income-producing property than an assignment of income. The attorney is not the mere beneficiary of the client’s largess, but rather earns his fee through skill and diligence. 345 F.3d, at 384-385 (quoting Estate of Clarks , supra , at 857-858). This reasoning, the court held, applies whether or not state law grants the attorney any special property interest ( e.g. , a superior lien) in part of the judgment or settlement proceeds.

B. Commissioner v. Banaitis

After leaving his job as a vice president and loan officer at the Bank of California in 1987, Sigitas J. Banaitis retained an attorney on a contingent-fee basis and brought suit in Oregon state court against the Bank of California and its successor in ownership, the Mitsubishi Bank. The complaint alleged that Mitsubishi Bank willfully interfered with Banaitis’ employment contract, and that the Bank of California attempted to induce Banaitis to breach his fiduciary duties to customers and discharged him when he refused. The jury awarded Banaitis compensatory and punitive damages. After resolution of all appeals and post-trial motions, the parties settled. The defendants paid $4,864,547 to Banaitis; and, following the formula set forth in the contingent-fee contract, the defendants paid an additional $3,864,012 directly to Banaitis’ attorney.

Banaitis did not include the amount paid to his attorney in gross income on his federal income tax return, and the Commissioner issued a notice of deficiency. The Tax Court upheld the Commissioner’s determination, but the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed. 340 F.3d 1074 (2003). In contrast to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the Banaitis court viewed state law as pivotal. Where state law confers on the attorney no special property rights in his fee, the court said, the whole amount of the judgment or settlement ordinarily is included in the plaintiff’s gross income. Id ., at 1081. Oregon state law, however, like the law of some other States, grants attorneys a superior lien in the contingent-fee portion of any recovery. As a result, the court held, contingent-fee agreements under Oregon law operate not as an anticipatory assignment of the client’s income but as a partial transfer to the attorney of some of the client’s property in the lawsuit.

To clarify why the issue here is of any consequence for tax purposes, two preliminary observations are useful. The first concerns the general issue of deductibility. For the tax years in question the legal expenses in these cases could have been taken as miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the ordinary requirements, 26 U.S.C. Secs. 67-68 (2000 ed. and Supp. I), but doing so would have been of no help to respondents because of the operation of the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). For noncorporate individual taxpayers, the AMT establishes a tax liability floor equal to 26 percent of the taxpayer’s “alternative minimum taxable income” (minus specified exemptions) up to $175,000, plus 28 percent of alternative minimum taxable income over $175,000. Secs. 55(a), (b) (2000 ed.). Alternative minimum taxable income, unlike ordinary gross income, does not allow any miscellaneous itemized deductions. Secs. 56(b)(1)(A)(i).

Second, after these cases arose Congress enacted the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, 118 Stat. 1418. Section 703 of the Act amended the Code by adding Sec. 62(a)(19). Id ., at 1546. The amendment allows a taxpayer, in computing adjusted gross income, to deduct “attorney fees and court costs paid by, or on behalf of, the taxpayer in connection with any action involving a claim of unlawful discrimination.” Ibid . The Act defines “unlawful discrimination” to include a number of specific federal statutes, Secs. 62(e)(1) to (16), any federal whistle-blower statute, Sec. 62(e)(17), and any federal, state, or local law “providing for the enforcement of civil rights” or “regulating any aspect of the employment relationship . . . or prohibiting the discharge of an employee, the discrimination against an employee, or any other form of retaliation or reprisal against an employee for asserting rights or taking other actions permitted by law,” Sec. 62(e)(18). Id ., at 1547-1548. These deductions are permissible even when the AMT applies. Had the Act been in force for the transactions now under review, these cases likely would not have arisen. The Act is not retroactive, however, so while it may cover future taxpayers in respondents’ position, it does not pertain here.

The Internal Revenue Code defines “gross income” for federal tax purposes as “all income from whatever source derived.” 26 U.S.C. Sec. 61(a). The definition extends broadly to all economic gains not otherwise exempted. Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co. , 348 U.S. 426, 429-430 (1955); Commissioner v. Jacobson, 336 U.S. 28, 49 (1949). A taxpayer cannot exclude an economic gain from gross income by assigning the gain in advance to another party. Lucas v. Earl , 281 U.S. 111 (1930); Commissioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591, 604 (1948); Helvering v. Horst , 311 U.S. 112, 116-117 (1940). The rationale for the so-called anticipatory assignment of income doctrine is the principle that gains should be taxed “to those who earn them,” Lucas, supra , at 114, a maxim we have called “the first principle of income taxation,” Commissioner v. Culbertson , 337 U.S. 733, 739-740 (1949). The anticipatory assignment doctrine is meant to prevent taxpayers from avoiding taxation through “arrangements and contracts however skillfully devised to prevent [income] when paid from vesting even for a second in the man who earned it.” Lucas , 281 U.S., at 115. The rule is preventative and motivated by administrative as well as substantive concerns, so we do not inquire whether any particular assignment has a discernible tax avoidance purpose. As Lucas explained, “no distinction can be taken according to the motives leading to the arrangement by which the fruits are attributed to a different tree from that on which they grew.” Ibid .

Respondents argue that the anticipatory assignment doctrine is a judge-made antifraud rule with no relevance to contingent-fee contracts of the sort at issue here. The Commissioner maintains that a contingent-fee agreement should be viewed as an anticipatory assignment to the attorney of a portion of the client’s income from any litigation recovery. We agree with the Commissioner.

In an ordinary case, attribution of income is resolved by asking whether a taxpayer exercises complete dominion over the income in question. Glenshaw Glass Co., supra , at 431; see also Commissioner v. Indianapolis Power & Light Co ., 493 U.S. 203, 209 (1990); Commissioner v. First Security Bank of Utah , N.A. , 405 U.S. 394, 403 (1972). In the context of anticipatory assignments, however, the assignor often does not have dominion over the income at the moment of receipt. In that instance, the question becomes whether the assignor retains dominion over the income-generating asset, because the taxpayer “who owns or controls the source of the income, also controls the disposition of that which he could have received himself and diverts the payment from himself to others as the means of procuring the satisfaction of his wants.” Horst, supra , at 116-117. See also Lucas, supra , at 114-115; Helvering v. Eubank , 311 U.S. 122, 124-125 (1940); Sunnen, supra , at 604. Looking to control over the income-generating asset, then, preserves the principle that income should be taxed to the party who earns the income and enjoys the consequent benefits.

In the case of a litigation recovery, the income-generating asset is the cause of action that derives from the plaintiff’s legal injury. The plaintiff retains dominion over this asset throughout the litigation. We do not understand respondents to argue otherwise. Rather, respondents advance two counterarguments. First, they say that, in contrast to the bond coupons assigned in Horst , the value of a legal claim is speculative at the moment of assignment, and may be worth nothing at all. Second, respondents insist that the claimant’s legal injury is not the only source of the ultimate recovery. The attorney, according to respondents, also contributes income-generating assets—effort and expertise—without which the claimant likely could not prevail. On these premises respondents urge us to treat a contingent-fee agreement as establishing, for tax purposes, something like a joint venture or partnership in which the client and attorney combine their respective assets—the client’s claim and the attorney’s skill—and apportion any resulting profits.

We reject respondents’ arguments. Though the value of the plaintiff’s claim may be speculative at the moment the fee agreement is signed, the anticipatory assignment doctrine is not limited to instances when the precise dollar value of the assigned income is known in advance. Lucas, supra; United States v. Bayse , 410 U.S. 441, 445, 450-452 (1973). Though Horst involved an anticipatory assignment of a predetermined sum to be paid on a specific date, the holding in that case did not depend on ascertaining a liquidated amount at the time of assignment. In the cases before us, as in Horst , the taxpayer retained control over the income-generating asset, diverted some of the income produced to another party, and realized a benefit by doing so. As Judge Wesley correctly concluded in a recent case, the rationale of Horst applies fully to a contingent-fee contract. Raymond v. United States , 355 F.3d, at 115-116. That the amount of income the asset would produce was uncertain at the moment of assignment is of no consequence.

We further reject the suggestion to treat the attorney-client relationship as a sort of business partnership or joint venture for tax purposes. The relationship between client and attorney, regardless of the variations in particular compensation agreements or the amount of skill and effort the attorney contributes, is a quintessential principal-agent relationship. Restatement (Second) of Agency Sec. 1, Comment e (1957) (hereinafter Restatement); ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct Rule 1.3, Comments 1, 1.7 1 (2002). The client may rely on the attorney’s expertise and special skills to achieve a result the client could not achieve alone. That, however, is true of most principal-agent relationships, and it does not alter the fact that the client retains ultimate dominion and control over the underlying claim. The control is evident when it is noted that, although the attorney can make tactical decisions without consulting the client, the plaintiff still must determine whether to settle or proceed to judgment and make, as well, other critical decisions. Even where the attorney exercises independent judgment without supervision by, or consultation with, the client, the attorney, as an agent, is obligated to act solely on behalf of, and for the exclusive benefit of, the client-principal, rather than for the benefit of the attorney or any other party. Restatement Secs. 13, 39, 387.

The attorney is an agent who is duty bound to act only in the interests of the principal, and so it is appropriate to treat the full amount of the recovery as income to the principal. In this respect Judge Posner’s observation is apt: “[T]he contingent-fee lawyer [is not] a joint owner of his client’s claim in the legal sense any more than the commission salesman is a joint owner of his employer’s accounts receivable. Kenseth , 259 F.3d, at 883. In both cases a principal relies on an agent to realize an economic gain, and the gain realized by the agent’s efforts is income to the principal. The portion paid to the agent may be deductible, but absent some other provision of law it is not excludable from the principal’s gross income.

This rule applies whether or not the attorney-client contract or state law confers any special rights or protections on the attorney, so long as these protections do not alter the fundamental principal-agent character of the relationship. Cf. Restatement Sec. 13, Comment b , and Sec. 14G, Comment a (an agency relationship is created where a principal assigns a chose in action to an assignee for collection and grants the assignee a security interest in the claim against the assignor’s debtor in order to compensate the assignee for his collection efforts). State laws vary with respect to the strength of an attorney’s security interest in a contingent fee and the remedies available to an attorney should the client discharge or attempt to defraud the attorney. No state laws of which we are aware, however, even those that purport to give attorneys an “ownership” interest in their fees, e.g. , 340 F.3d, at 1082-1083 (discussing Oregon law); Cotnam , 263 F.2d, at 125 (discussing Alabama law), convert the attorney from an agent to a partner.

Respondents and their amici propose other theories to exclude fees from income or permit deductibility. These suggestions include: (1) The contingent-fee agreement establishes a Subchapter K partnership under 26 U.S.C. Secs. 702 704, and 761, Brief for Respondent Banaitis in No. 03-907, p. 5-21; (2) litigation recoveries are proceeds from disposition of property, so the attorney’s fee should be subtracted as a capital expense pursuant to Secs. 1001, 1012, and 1016, Brief for Association of Trial Lawyers of America as Amicus Curiae 23-28, Brief for Charles Davenport as Amicus Curiae 3-13; and (3) the fees are deductible reimbursed employee business expenses under Sec. 62(a)(2)(A) (2000 ed. and Supp. I), Brief for Stephen Cohen as Amicus Curiae . These arguments, it appears, are being presented for the first time to this Court. We are especially reluctant to entertain novel propositions of law with broad implications for the tax system that were not advanced in earlier stages of the litigation and not examined by the Courts of Appeals. We decline comment on these supplementary theories. In addition, we do not reach the instance where a relator pursues a claim on behalf of the United States. Brief for Taxpayers Against Fraud Education Fund as Amicus Curia e 10-20.

The foregoing suffices to dispose of Banaitis’ case. Banks’ case, however, involves a further consideration. Banks brought his claims under federal statutes that authorize fee awards to prevailing plaintiffs’ attorneys. He contends that application of the anticipatory assignment principle would be inconsistent with the purpose of statutory fee shifting provisions. See Venegas v. Mitchell , 495 U.S. 82, 86 (1990) (observing that statutory fees enable “plaintiffs to employ reasonably competent lawyers without cost to themselves if they prevail”). In the federal system statutory fees are typically awarded by the court under the lodestar approach, Hensley v. Eckerhart , 461 U.S. 424, 433 (1983), and the plaintiff usually has little control over the amount awarded. Sometimes, as when the plaintiff seeks only injunctive relief, or when the statute caps plaintiffs’ recoveries, or when for other reasons damages are substantially less than attorney’s fees, court-awarded attorney’s fees can exceed a plaintiff’s monetary recovery. See, e.g. , Riverside v. Rivera , 477 U.S. 561, 564-565 (1986) (compensatory and punitive damages of $33,350; attorney’s fee award of $245,456.25). Treating the fee award as income to the plaintiff in such cases, it is argued, can lead to the perverse result that the plaintiff loses money by winning the suit. Furthermore, it is urged that treating statutory fee awards as income to plaintiffs would undermine the effectiveness of fee-shifting statutes in deputizing plaintiffs and their lawyers to act as private attorneys general.

We need not address these claims. After Banks settled his case, the fee paid to his attorney was calculated solely on the basis of the private contingent-fee contract. There was no court-ordered fee award, nor was there any indication in Banks’ contract with his attorney, or in the settlement agreement with the defendant, that the contingent fee paid to Banks’ attorney was in lieu of statutory fees Banks might otherwise have been entitled to recover. Also, the amendment added by the American Jobs Creation Act redresses the concern for many, perhaps most, claims governed by fee-shifting statutes.

For the reasons stated, the judgments of the Courts of Appeals for the Sixth and Ninth Circuits are reversed, and the cases are remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE took no part in the decision of these cases.

[1] Together with No. 03–907, Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Banaitis, on certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Time and Manner of Making §163(d)(4)(B) Election to Treat Qualified Dividend Income as Investment Income

Department of the treasury internal revenue service 26 cfr part 1.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Treasury.

Final regulations and removal of temporary regulations.

This document contains final regulations relating to an election that may be made by noncorporate taxpayers to treat qualified dividend income as investment income for purposes of calculating the deduction for investment interest. The regulations reflect changes to the law made by the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003. The regulations affect taxpayers making the election under section 163(d)(4)(B) to treat qualified dividend income as investment income.

Effective Date : These regulations are effective March 18, 2005.

Applicability Dates : For dates of applicability, see §1.163(d)-1(d).

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Amy Pfalzgraf, (202) 622-4950 (not a toll-free number).

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

This document contains amendments to 26 CFR part 1 under section 163(d) of the Internal Revenue Code (Code). On August 5, 2004, temporary regulations (T.D. 9147, 2004-37 I.R.B. 461) were published in the Federal Register (69 FR 47364) relating to an election that may be made by noncorporate taxpayers to treat qualified dividend income as investment income for purposes of calculating the deduction for investment interest. A notice of proposed rulemaking (REG-171386-03, 2004-37 I.R.B. 477) cross-referencing the temporary regulations also was published in the Federal Register (69 FR 47395) on August 5, 2004. No comments in response to the notice of proposed rulemaking or requests to speak at a public hearing were received, and no hearing was held. This Treasury decision adopts the proposed regulations and removes the temporary regulations.

Special Analyses

It has been determined that this Treasury decision is not a significant regulatory action as defined in Executive Order 12866. Therefore, a regulatory assessment is not required. It also has been determined that section 553(b) of the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. chapter 5) does not apply to these regulations, and because the regulations do not impose a collection of information on small entities, the Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. chapter 6) does not apply. Pursuant to section 7805(f) of the Code, the proposed regulations preceding these regulations were submitted to the Chief Counsel for Advocacy of the Small Business Administration for comment on their impact on small business.

Adoption of Amendments to the Regulations

Accordingly, 26 CFR part 1 is amended as follows:

Part 1—INCOME TAXES

Paragraph 1. The authority citation for part 1 continues to read, in part, as follows:

Authority: 26 U.S.C. 7805 * * *

Par. 2. Section 1.163(d)-1 is revised to read as follows:

§1.163(d)-1 Time and manner for making elections under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003.

(a) Description . Section 163(d)(4) (B)(iii), as added by section 13206(d) of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (Public Law 103-66, 107 Stat. 467), allows an electing taxpayer to take all or a portion of certain net capital gain attributable to dispositions of property held for investment into account as investment income. Section 163(d)(4)(B), as amended by section 302(b) of the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (Public Law 108-27, 117 Stat. 762), allows an electing taxpayer to take all or a portion of qualified dividend income, as defined in section 1(h)(11)(B), into account as investment income. As a consequence, the net capital gain and qualified dividend income taken into account as investment income under these elections are not eligible to be taxed at the capital gains rates. An election may be made for net capital gain recognized by noncorporate taxpayers during any taxable year beginning after December 31, 1992. An election may be made for qualified dividend income received by noncorporate taxpayers during any taxable year beginning after December 31, 2002, but before January 1, 2009.

(b) Time and manner for making the elections . The elections for net capital gain and qualified dividend income must be made on or before the due date (including extensions) of the income tax return for the taxable year in which the net capital gain is recognized or the qualified dividend income is received. The elections are to be made on Form 4952, “ Investment Interest Expense Deduction ,” in accordance with the form and its instructions.

(c) Revocability of elections . The elections described in this section are revocable with the consent of the Commissioner.

(d) Effective date . The rules set forth in this section regarding the net capital gain election apply beginning December 12, 1996. The rules set forth in this section regarding the qualified dividend income election apply to any taxable year beginning after December 31, 2002, but before January 1, 2009.

Par. 3. Section 1.163-1T is removed.

Approved March 10, 2005.

(Filed by the Office of the Federal Register on March 17, 2005, 8:45 a.m., and published in the issue of the Federal Register for March 18, 2005, 70 F.R. 13100)

Drafting Information

The principal author of these regulations is Amy Pfalzgraf of the Office of Associate Chief Counsel (Income Tax & Accounting). However, other personnel from the IRS and Treasury Department participated in their development.

Charitable Remainder Trusts; Application of Ordering Rule

Final regulations.

This document contains final regulations on the ordering rules of section 664(b) of the Internal Revenue Code for characterizing distributions from charitable remainder trusts (CRTs). The final regulations reflect changes made to income tax rates, including the rates applicable to capital gains and certain dividends, by the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003. The final regulations provide guidance needed to comply with these changes and affect CRTs and their beneficiaries.

Effective Date : These regulations are effective on March 16, 2005.

Applicability Dates : For dates of applicability, see §1.664-1(d)(1)(ix).

Theresa M. Melchiorre, (202) 622-7830 (not a toll-free number).

This document contains amendments to the Income Tax Regulations (26 CFR part 1) under section 664(b) of the Internal Revenue Code. On November 20, 2003, the Treasury Department and the IRS published a notice of proposed rulemaking (REG-110896-98, 2003-2 C.B. 1226) in the Federal Register (68 FR 65419). The public hearing scheduled for March 9, 2004, was cancelled because no requests to speak were received. Several written comments responding to the notice of proposed rulemaking were received. After consideration of the written comments, the proposed regulations are adopted as revised by this Treasury decision. The revisions and a summary of the comments are discussed below.

The proposed regulations reflected changes made to income tax rates, including the rates applicable to capital gains and certain dividends, by the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (TRA), Public Law 105-34 (111 Stat. 788), and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA), Public Law 108-27 (117 Stat. 752). These changes affect the ordering rules of section 664(b) for characterizing distributions from CRTs.

Prior to the TRA, long-term capital gains were generally subject to the same Federal income tax rate. The TRA provided, however, that gain from certain types of long-term capital assets would be subject to different Federal income tax rates. Accordingly, after May 6, 1997, a CRT could have at least three classes of long-term capital gains and losses: a class for 28-percent gain (gains and losses from collectibles and section 1202 gains); a class for unrecaptured section 1250 gain (long-term gains not treated as ordinary income that would be treated as ordinary income if section 1250(b)(1) included all depreciation); and a class for all other long-term capital gain. In addition, the TRA provided that qualified 5-year gain (as defined in section 1(h)(9) prior to amendment by the JGTRRA) would be subject to reduced capital gains tax rates under certain circumstances for certain taxpayers. For taxpayers subject to a 10-percent capital gains tax rate, qualified 5-year gain would be taxed at an 8-percent capital gains tax rate effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2000. For taxpayers subject to a 20-percent capital gains tax rate, qualified 5-year gain would be taxed at an 18-percent capital gains tax rate provided the holding period for the property from which the gain was derived began after December 31, 2000. As a result, a CRT could also have a class for qualified 5-year gain.

Prior to the JGTRRA, a CRT’s ordinary income was generally subject to the same Federal income tax rate. The JGTRRA provided, however, that qualified dividend income as defined in section 1(h)(11) would be subject to the Federal income tax rate applicable to the class for all other long-term capital gain. As a result, after December 31, 2002, a CRT could have a qualified dividend income class that would be subject to a different Federal income tax rate than that applicable to the CRT’s other types of ordinary income. In addition, the JGTRRA provided that qualified 5-year gain would cease to exist after May 5, 2003, but that it would return after December 31, 2008.

In response to the changes made by the TRA and the technical corrections to the TRA made by the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, Public Law 105-206 (112 Stat. 685), the IRS issued guidance on the treatment of capital gains under section 664(b)(2) in Notice 98-20, 1998-1 C.B. 776, as modified by Notice 99-17, 1999-1 C.B. 871. The proposed regulations incorporated the guidance provided in Notice 98-20 and Notice 99-17. In addition, the proposed regulations provided additional guidance on the treatment of qualified dividend income under section 664(b)(1) and the treatment of a class of income that temporarily ceases to exist, like the qualified 5-year gain class.

Explanation of Provisions

The proposed regulations provided that trusts must maintain separate classes within a category of income when two classes are only temporarily subject to the same tax rate (for example, if the current tax rate applicable to one class sunsets in a future year). In the preamble to the proposed regulations, comments were requested on the degree of administrative burden and potential tax benefit or detriment of this requirement. Only one comment was received in response to this request. The commentator pointed out that maintaining a class during a temporary period of suspension could be favorable to taxpayers in one situation and unfavorable in another. For example, maintaining the qualified 5-year gain class during a temporary period of suspension would be advantageous because when the class is again in existence, gain distributed from the class probably would be taxed at a rate lower than the rates applicable to other classes of long-term capital gain. On the other hand, if the 28-percent long-term capital gain class is taxed at 15 percent during a temporary period, gain distributed from that class after the expiration of that temporary period is likely to be taxed at a rate higher than the rates applicable to other classes of long-term capital gain.

The IRS and Treasury Department continue to believe that it is appropriate for CRTs to maintain separate classes for income only temporarily taxed at the same rate, and no comment received indicated that this requirement would be unduly burdensome. Therefore, this requirement remains unchanged in the final regulations.

The proposed regulations provided that, to be eligible for inclusion in the class of qualified dividend income, dividends must meet the definition of section 1(h)(11) and must be received by the trust after December 31, 2002. Several commentators suggested that the final regulations should provide that undistributed dividends received by a CRT prior to January 1, 2003, that would otherwise meet the definition of qualified dividends under section 1(h)(11), be treated as qualified dividends.

Subsequent to the issuance of the proposed regulations, a technical correction was made to the JGTRRA by the Working Families Tax Relief Act of 2004, Public Law 108-311 (118 Stat. 1166), to provide that dividends received by a trust on or before December 31, 2002, shall not be treated as qualified dividend income as defined in section 1(h)(11). Accordingly, this suggestion has not been adopted in the final regulations.

The proposed regulations provided that, in netting capital gains and losses, a net short-term capital loss is first netted against the net long-term capital gain in each class before the long-term capital gains and losses in each class are netted against each other. One commentator suggested that this netting rule be revised to provide that the gains and losses of the long-term capital gain classes be netted prior to netting short-term capital loss against any class of long-term capital gain.

The IRS and Treasury Department believe that the netting rules for CRTs should be consistent with the netting rules applicable generally to other noncorporate taxpayers. Accordingly, the final regulations adopt this suggested change.

The proposed regulations provided that items of income within the ordinary income and capital gains categories are assigned to different classes based on the Federal income tax rate applicable to each type of income in that category in the year the items are required to be taken into account by the CRT. One commentator suggested that the assignment of items of income to different classes in the year the items are required to be taken into account by the CRT should be based on the Federal income tax rate that is likely to apply to that item in the hands of the recipient (for example, depending on the recipient’s marginal income tax rate bracket) in the year in which the item is distributed.

The final regulations do not adopt this change. It is not feasible in many instances for trustees to determine the tax bracket of beneficiaries. The IRS and Treasury Department believe that the assignment of an item to a particular class should be based upon the tax rate applicable to each class when the item is received by the CRT, and not the various tax rates applicable to the classes at the time of a distribution to the beneficiary.

The proposed regulations provided that the determination of the tax character of amounts distributed by a CRT shall be made as of the end of the taxable year of the CRT. One commentator recommended that the language in the proposed regulations be reworded to make it clear that this rule applies to all distributions made by the CRT to recipients throughout the calendar year. In response to the comment, the second sentence in §1.664-1(d)(1)(ii)( a ) is revised in the final regulations to read, “[t]he determination of the character of amounts distributed or deemed distributed at any time during the taxable year of the trust shall be made as of the end of that taxable year.”

The proposed regulations provided that the annuity or unitrust recipient is taxed on the distribution from the CRT based on the tax rates applicable in the year of the distribution to the classes of income that are deemed distributed from the trust. One commentator suggested that the language in the proposed regulations be reworded to make it clear that the tax rates applicable to a distribution or deemed distribution from a CRT to a recipient are the tax rates applicable to the classes of income from which the distribution is derived in the year of distribution, and not the tax rates applicable to the income in the year it is received by the CRT. This suggestion has been adopted. In the final regulations, the third sentence in §1.664-1(d)(1)(ii)( a ) is revised to read as follows:

The tax rate or rates to be used in computing the recipient’s tax on the distribution shall be the tax rates that are applicable, in the year in which the distribution is required to be made, to the classes of income deemed to make up that distribution, and not the tax rates that are applicable to those classes of income in the year the income is received by the trust.