Welcome to Quest Quest provides tools to incorporate online multimedia content and assessments into your course. This hybrid of in-class and online teaching can take on many forms:

Flipped Classroom Quest provides lecture content to students online before class and the classroom time is saved for case studies, problem solving, demonstrations, etc. The linked assessment feature assures students have seen the content and reveals their level of understanding of the material.

Online Content Quest prepares students for lectures with prerequisite knowledge. Feedback from the assessment highlights areas that may need emphasis.

Pre-Lab Quest can offer pre-laboratory exercises that demonstrate what occurs in experiments. This preparation and assessment can increase safety in the laboratory also.

Search Results

Assignments | monster hunter world wiki.

- Create new page

- Recent Changes

- Permissions

- Edit Open Graph

- Clear page cache

- Clear comments cache

- File Manager

- Page Manager

- Wiki Templates

- Comments Approval

- Wiki Settings

- Wiki Manager

Assignments are story Quests in Monster Hunter World (MHW) . Players will need to complete these quest to progress the story, access the game, and increase their Hunter Rank (HR).

MHW Assignments

These are the story quests of the base game. Players do not need the expansion to complete these quests, that go from Low Rank to High Rank.

All assignments have a 50 minutes time limit and the "Faint 3 times" failure conditions.

| 1 | ★1 | Slay 7 | 720 | |

| 1 | ★2 | Slay 5 Female & 3 Male | 1200 | |

| 1 | ★2 | Hunt a | 1200 | |

| 2 | ★2 | Hunt a | 1800 | |

| 2 | ★3 | Hunt a | 2520 | |

| 3 | ★3 | Hunt a | 2520 | |

| 3 | ★3 | Hunt a | 3240 | |

| 4 | ★3 | Hunt a | 3240 | |

| 4 | ★4 | Hunt an | 4320 | |

| 5 | ★4 | Capture | 4320 | |

| 6 | ★4 | Hunt a | 4320 | |

| 7 | ★4 | Hunt a | 4320 | |

| 8 | ★5 | Hunt a | 5400 | |

| 8 | ★5 | Hunt an | 5400 | |

| 8 | ★5 | Hunt a | 5400 | |

| 8 | ★5 | Hunt a | 5400 | |

| 10 | ★6 | Repel | 8280 | |

| 11 | ★6 | Hunt a | 7200 | |

| 12 | ★6 | Hunt an | 9000 | |

| 13 | ★7 | Hunt a | 12600 | |

| 14 | ★8 | Slay | 18000 | |

| 14 | ★8 | Slay | 18000 | |

| 14 | ★8 | Slay | 18000 | |

| 14 | ★8 | Slay | 18000 | |

| 15 | ★9 | Slay | 19800 | |

| 29 | ★9 | Hunt two tempered | 27720 | |

| 49 | ★9 | Slay a tempered | 21600 |

Master Rank Assignments

| 1 | Hunt a | 14400 | ||

| 2 | Hunt a | 14400 | ||

| 3 | Hunt a | 18000 | ||

| 4 | Hunt a | 18000 | ||

| 4 | Hunt a | 18000 | ||

| 6 | Hunt a | 25200 | ||

| 7 | Hunt a | 25200 | ||

| 7 | Hunt a | 25200 | ||

| 9 | Hunt a | 25200 | ||

| 9 | Hunt a | 25200 | ||

| 11 | Repel | 28800 | ||

| 12 | Hunt a | 28800 | ||

| 13 | Hunt a | 28800 | ||

| 14 | Hunt an | 28800 | ||

| 14 | Hunt an | 28800 | ||

| 16 | Repel | 28800 | ||

| 17 | Slay | 28800 | ||

| 18 | Hunt a | 36000 | ||

| 19 | Slay | 36000 | ||

| 20 | Slay | 36000 | ||

| 21 | Slay | 14400 | ||

| 22 | Slay | 43200 | ||

| 24 | Hunt a | 28800 | ||

| 49 | Hunt Tempered + Tempered | 34560 | ||

| 69 | Hunt Tempered + Tempered | 48600 | ||

| 99 | Slay | 36000 |

Yo could someone tell me if dragonbone stabber is any good for the kushala daora quest

Help me with nergigante pls

Ik this isn't the topic but can I have tips on pink rathian fight

Ich check es nicht. Ich habe iceborn komplett durch alle quest fertig aber bleibe auf Mr 49 hängen, und es steigt einfach nicht

With the kirin quest for base game are you sure there's nothing else cause I can't get past 50 so...

Did y'all know you can "fix the website" yourselves if you know what is wrong with one of the pages since this is a wiki? Lots of people put lots of paidless effort into this, don't be a ****ing Customer when you're not even paying to use the website. Please.

Love how we chase nergigante the complete history of the game, even in iceborne.

can't understand why the game tried to give you a feeling that it kind of ended once zora was send into the sea, when that aint even half of it

You don’t have to because it’s pretty much complete unless I’m wrong but adding the parts where you look for tracks. Again I don’t really see the point but why not

I can defeat a great jagras in 20 sec. also I'm star 7 but I am trying to defeat nergigante

Good job! If possible, add more details to the "Big Burly Bash" quest, because it seems kinda incomplete. Thanks!

You missed Shara ishvalda

THEIR ARE NO MISTAKES ANYMORE SO NO NEED TO KEEP COMPLAINING

Missed hunt a tzi tzi yaku between a ballooning problem and one for history book

Forgot the Beotoadus mission. Don't be incompitent. Fix your website. Add the proper information.

So there are no more quests after the tempered Kirin? What do I do now?

No hunt you can kill or capture where slay is you can only kill it meaning the monster is uncapture able

Aren't slay and hunt the same thing tho

I still think they made a mistake by making Legiana AFTER Radobaan, like we already been to Rotten Vale but then before Legiana quest they keep saying stuffs like they've never been there

Old monster in the new world is pink rathian

Into the Bowels of the Vale is the odogaron mission

Hunt assignment for the odogaron is missing.

Are quest HR ranks accurate here? Been looking for an assigned quest guide/list with the ranks and some pages i've looked at have been slightly different. As far as I can tell they are accurate but i'm only on the sixth story mission so don't know any farther than that. Thanks.

I took the liberty to redo the entire page, now to fill all these quests...

Who picked the format for this page? Its totally asinine to try to split the quests up this way. Whats wrong with just 2 columns of "low rank" and "high rank"?

- Hunters Online

- Recent Changes +

- File Manager +

- Page Manager +

- Create Wiki +

- ⇈ Back to top ⇈

Using Quests in Project-Based Learning

Questlines—learning pathways that are both personalized and differentiated—build choice into any lesson.

Your content has been saved!

Student choice and voice are components of what the Buck Institute for Education considers the gold standard of a project-based learning unit because giving students choice can pique motivation and engagement.

Student choice also connects to self-determination theory. According to Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, there are three drivers of self-determination : autonomy (the perception of being in control), competence (feeling capable to achieve), and relatedness (social belongingness).

Choice-based learning is an approach some teachers use to apply self-determination theory to motivate students. More than giving students a menu of assignments to select from, choice-based learning is a flavor of gamification that uses a questline structure to present learning as a series of pathways. (Questlines are common in video games—players unlock parts of a map as they achieve goals or master levels. The map may unlock in nonlinear paths that lead to one or a few end goals.)

Student Choice and Questlines

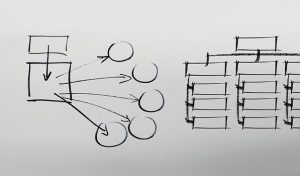

Basically, questlines are learning pathways that are both personalized and differentiated. In a lesson plan, questlines should resemble an upside-down tree (like a family tree), starting with limited choices which then branch outward with more choices—in other words, choices are scaffolded so you don’t overwhelm your students.

To build questlines, start small. Try a project-based learning lesson that already has a menu of options or choices. For example, if you’re an English language arts teacher, you can create quests themed on genres of fiction or literary devices. Science and math teachers can begin by teaching facts and then branch off to quests in which students can apply what they’ve learned and mastered to real world contexts.

It’s easy to create questlines for students if you already have assignments that break down topics into a menu of choices. For example, you can convert a project-based learning lesson into a mission—perhaps students become time-traveling detectives, miniaturized doctors inside a human body, or Cold War spies.

I adapted a unit designed to teach about life in the Middle Ages in Europe. Because I had already written it as a project-based learning unit, it was simple to adapt to a questline structure. To start, all students were given the same narrative hook. They then watched a content-aligned BrainPOP video and answered basic, fundamental questions. Next, they selected subtopics to explore, ranging from the feudal system to the Crusades to the role of the Church in daily life. Subsequent questline branches then fanned outward (again, like a family tree) as students were given even more choices on what they wanted to learn about and what they wanted to make for their culminating projects. These ranged from building worlds in Minecraft to recording podcasts to writing historical fiction stories.

Tools and Platforms

With choice-based lessons, you can do low-tech planning with Post-it notes, or digital planning using mind-mapping tools such as Popplet or Bubbl.us . Then branch out with different activities and reflections pertaining to your content. Students should turn in reflections at the end of each quest.

There are quite a few tools and platforms to help teachers create choice-based learning. Educator Enrique Cachafeiro uses hyperlinks (links that jump to different webpages) to create questlines. For instance, he combined ThingLink—which lets users pin links to digital images—with the learning management system Canvas to create assignments such as a biology-themed quest . Cachafeiro has also shared the lessons he has learned about gamification.

There are several learning management systems that include quests. Rezzly (formerly 3D GameLab) was one of the first to include branched quests. It features an area where teachers can share and remix lessons. Deck.Toys , another platform, is highly visual. There are free and paid options, and a gallery of lessons shared.

Classcraft , which has both Google Classroom and Microsoft Office 365 integration, just added quests this past fall. Easy to set up, its quests feature colorful maps that allow teachers to drag and drop pins (a capability similar to the one in Google Maps) as assignments. These pins can then be connected with arrows. Teachers can also share and remix lessons via peer-to-peer links.

A choice-based approach puts learners in the driver’s seat. The structure of branching pathways gives learners a sense of agency or autonomy. What’s more, quests offer a way to gamify learning that avoids many of the extrinsic trappings sometimes associated with gamification, like point-based leaderboards, that can lead to artificial competition.

Interestingly, some students—more than you might think—will binge quests, completing more than the minimum amount of work (perhaps completing more than one questline, for instance). For fast-finishers, consider side quests. In video games, side quests are mini-missions that accrue points but are peripheral to the overall game story.

Giving students choice by adding quests to lessons is a game-like approach intended to add a sense of autonomy to learning.

Email Newsletter

Receive free lesson plans, printables, and worksheets by email:

What is a Web Quest? How Do Teachers Use Them?

What's All the Hype?

It seems as if educators are striving to get an Internet connection in their classroom these days. The most common rationale for this movement is to provide students passive access to valuable information. Traditionally, most schools have used libraries as a main source of access and still do.

More recently, schools have discovered the Internet as a source which obviously breaks away from traditionalism. The question remains: Does digital/electronic access to information make a difference in fostering higher order thinking?

The Quest for Knowledge

The Internet, unlike any other medium before it, is interactive and accessible to a great deal of people at once. It has the ability to provide endless amounts of information that can be used to motivate students to conduct investigations on any given topic. As an interactive tool for learning, teachers can use the Internet to stimulate creative thought and guide students to develop critical thinking in their "quest" for knowledge. But, how does a teacher tame the nature of the Internet to provide his/her students with a beneficial learning environment?

The Nature of a Web Quest

One model approach for this dilemma is called a Web Quest developed in 1995 by Bernie Dodge of San Diego State University. Simply put, a Web Quest is an inquiry-based activity where students are given a task and provided with access to on-line resources to help them complete the task. It is an ideal way to deliver a lesson over the web. Web Quests are discovery learning tools; they are usually used to either begin or finish a unit of study.

When creating a Web Quest, it is beneficial to be able to make your own web pages. But, it is not necessary. Teachers have delivered fantastic Web Quests in hard copy format.

Over the last five years, the TeAch-nology.com staff has seen a great deal of Web Quests. Some are good, some are great, and some are not worth the time it takes to download. In this tutorial, we will examine the use of Web Quests and qualities of effective Web Quests.

Six Reasons Teachers To Use Web Quests

1. To begin a unit as an anticipatory set (as per Madeline Hunter);

2. To conclude a unit as a summation;

3. As a collaborative activity in which students create a product (fostering cooperative learning);

4. To teach students how to be independent thinkers since most of the problems encountered in a Web Quest are real-world problems;

5. To increase competency in the use of technology; and

6. As a motivational techniques to keep students on task. However, if it proves to be an inefficient method of learning for your particular students (for whatever reasons), don't use it!

Qualities of Effective Web Quests

The Beauty of Web Quests are their flexibility since they can be anything to anyone. This makes it hard to identify a typically effective Web Quest. Nonetheless, we have found that Web Quests that promote learning typically have 6 common attributes.

1. Introduction:

The introduction is a means of providing the students with background information that is intended to be a springboard for them to begin the process of inquiry. One way is to present a simulation that leads students to develop a product/service, evaluate a time period, give advice on a given issue, manage a business situation, engage in a debate, or tackle one of life's challenges.

Formulating challenging questions is the difficult part of developing an effective Web Quest. In most cases, a single question is posed that requires students to analyze a vast array of information. For example, "Compare the leadership styles of George Washington and George Bush," or "You just made a revolutionary invention, what steps would you take to insure that no one can steal your ideas for profit?"

3. Process:

In this section, the teacher leads the student through the task. The teacher offers advice on how to manage time, collect data, and provides strategies for working in group situations. Teachers sometimes label this section: learning objectives or advice. In some cases the section is replaced with a complete time line for the project.

4. Resources:

Students are provided with tools (usually web sites), or leads to tools that can help them complete the task. In order for this to be valuable, a teacher must thoroughly review each source. When deciding on sources consider the following:

a. Only list sites that support the proper view for which you are aiming. For every site that explains how > helpful the rain forest is, there are two sites to explain how bad it is.

b. Make sure all the sites you choose are appropriate and do not link to any inappropriate sites.

c. Make sure the source is credible. Anybody can create a web page. Try to use a commercial (.com), non-profit (.org), or educational organization (.edu) site. These sites have something to lose by providing you with poor content.

d. Make sure the site is up to date.

5. Evaluation:

The outcome for Web Quests is usually a product, in most cases, in form of a written/oral report or multimedia presentation. An effective assessment tool to evaluate a product of a Web Quest is a rubric. Rubrics help make the teacher's expectations clear for students. Ideally, rubrics can be created collaboratively with students' input.

6. Conclusion:

Effective Web Quests have a built in mechanism for student reflections. To receive feedback, you can survey your students about their experience, or have the students send you an e-mail sharing their thoughts.

Where to find Web Quests Resources

Click here for TeAch-nology.com's in-depth review of available Web Quest resources on the Internet.

Make your own FREE web quest either on the web or in hard copy format with TeAch-nology.com web tools. To make a web site click here . To make your own hard copy web quest click here .

- Professional

- International

Select a product below:

- Connect Math Hosted by ALEKS

- My Bookshelf (eBook Access)

Sign in to Shop:

My Account Details

- My Information

- Security & Login

- Order History

- My Digital Products

Log In to My PreK-12 Platform

- AP/Honors & Electives

- my.mheducation.com

- Open Learning Platform

Log In to My Higher Ed Platform

- Connect Math Hosted by Aleks

Business and Economics

Accounting Business Communication Business Law Business Mathematics Business Statistics & Analytics Computer & Information Technology Decision Sciences & Operations Management Economics Finance Keyboarding Introduction to Business Insurance & Real Estate Management Information Systems Management Marketing

Humanities, Social Science and Language

American Government Anthropology Art Career Development Communication Criminal Justice Developmental English Education Film Composition Health and Human Performance

History Humanities Music Philosophy and Religion Psychology Sociology Student Success Theater World Languages

Science, Engineering and Math

Agriculture & Forestry Anatomy & Physiology Astronomy & Physical Science Biology - Majors Biology - Non-Majors Chemistry Cell/Molecular Biology & Genetics Earth & Environmental Science Ecology Engineering/Computer Science Engineering Technologies - Trade & Tech Health Professions Mathematics Microbiology Nutrition Physics Plants & Animals

Digital Products

Connect® Course management , reporting , and student learning tools backed by great support .

McGraw Hill GO Greenlight learning with the new eBook+

ALEKS® Personalize learning and assessment

ALEKS® Placement, Preparation, and Learning Achieve accurate math placement

SIMnet Ignite mastery of MS Office and IT skills

McGraw Hill eBook & ReadAnywhere App Get learning that fits anytime, anywhere

Sharpen: Study App A reliable study app for students

Virtual Labs Flexible, realistic science simulations

Inclusive Access Reduce costs and increase success

LMS Integration Log in and sync up

Math Placement Achieve accurate math placement

Content Collections powered by Create® Curate and deliver your ideal content

Custom Courseware Solutions Teach your course your way

Professional Services Collaborate to optimize outcomes

Remote Proctoring Validate online exams even offsite

Institutional Solutions Increase engagement, lower costs, and improve access for your students

General Help & Support Info Customer Service & Tech Support contact information

Online Technical Support Center FAQs, articles, chat, email or phone support

Support At Every Step Instructor tools, training and resources for ALEKS , Connect & SIMnet

Instructor Sample Requests Get step by step instructions for requesting an evaluation, exam, or desk copy

Platform System Check System status in real time

What is Quest: Journey Through the Lifespan?

Quest: Journey Through the Lifespan is an engaging and innovative auto-graded learning game providing students with opportunities to apply content from their human development curriculum to real life whether you are teaching face-to-face or online.

What are students saying about Quest: Journey Through the Lifespan?

Did you recognize content you were learning about in class, did quest: journey through the lifespan help make content and theories relevant to daily life, is quest: journey through the lifespan engaging.

It was enjoyable and I feel like I learned a lot from it because of how it relates to real-life experiences.

Autumn W. Forsyth Technical Community College Student

I loved this learning tool. It is way more engaging than anything I’ve ever used. It made learning fun! 10/10!

Cedtazia M. Florida International University Student

What are Instructors Saying about Quest: Journey Through the Lifespan?

Want to enhance your course with Quest: Journey Through the Lifespan?

Let's talk - book a call.

Complete the form below, and we’ll reach out to schedule a call.

Fields marked by * are required.

Your information will be used to provide you with the requested information and other information about McGraw Hill’s products and services. You may opt out at any time by contacting McGraw Hill’s local privacy officer or selecting “unsubscribe” at the bottom of any email you receive from us.

- Accessibility

It is the first learning game designed with inclusivity and accessibility at the forefront of development. Each stage of development was designed, developed, and tested against WCAG standards to ensure all learners will benefit from this amazing new learning resource!

Application

A learning game designed to help students apply course content and theories into real-life scenarios. Each quest is auto-graded and carefully designed to optimize student learning and efficiency. Follow-up analytical questions are available for further critical thinking.

Each character, environment, and task bring in real-life scenarios, questions, and factors to keep students engaged while helping them understand how what they are learning about is important to everyday life!

Culture and Diversity

Students play in the first person as 14 different characters who vary in age from 9 months to 80 years, as well as range in gender, race, and nationality. By taking on the perspectives of their characters, students experience human development concepts and theories—as well as real-world problems and situations—through the eyes of others, developing skills related to understanding others’ motivations, intentions, and behaviors.

Higher-Level Assessment

In addition to completing content-related objectives during game play, follow-up higher-level assessment is available for each of the 14 quests. Instructors can choose from 17 multiple choice and three short-answer questions to assign and assess students’ understanding of content applied during the game play experience.

Course Offerings

Included with Connect when using a McGraw Hill textbook at no additional charge in:

- Lifespan Development

- Child Development

- Adolescence

Life: The Essentials of Human Development , Link will open in a new window

By: Gabriela Martorell

Essentials of Life-Span Development , Link will open in a new window

By: John W. Santrock

A Topical Approach to Lifespan Development , Link will open in a new window

Life-Span Development , Link will open in a new window

Experience Human Development , Link will open in a new window

By: Diane E. Papalia and Gabriela Martorell

By: John Santrock

Child , Link will open in a new window

Children , Link will open in a new window

Child Development , Link will open in a new window

Adolescence , Link will open in a new window

By: Laurence Steinberg

Company Info

- Contact & Locations

- Trust Center

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Social Responsibility

- Investor Relations

- Social Media Directory

- Place an Order

- Get Support

- Contact Customer Service

- Contact Sales Rep

- Check System Status

Additional Resources

- Permissions

- Author Support

- International Rights

- Purchase Order

- Our AI Approach

Follow McGraw Hill:

©2024 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved.

Welcome to the University Wiki Service! Please use your IID ([email protected]) when prompted for your email address during login or click here to enter your EID . If you are experiencing any issues loading content on pages, please try these steps to clear your browser cache .

.css-1lrpez4{margin-top:unset;}.css-1lrpez4:hover > span,.css-1lrpez4:focus-within > span{opacity:1;-webkit-transform:none;-ms-transform:none;transform:none;-webkit-transform-duration:0.1s;-ms-transform-duration:0.1s;transform-duration:0.1s;} Numbers and Scientific Notation .css-14vda7h{font-size:15px;margin-inline-start:0.5rem;opacity:0;position:absolute;-webkit-transform:translateX(-4px);-ms-transform:translateX(-4px);transform:translateX(-4px);-webkit-transition:opacity 0.2s ease-out 0s,-webkit-transform 0.2s ease-out 0s;-webkit-transition:opacity 0.2s ease-out 0s,transform 0.2s ease-out 0s;transition:opacity 0.2s ease-out 0s,transform 0.2s ease-out 0s;}

Help Awaits

At any point you can email [email protected] with questions or concerns regarding technical difficulties using the system.

Some questions you may encounter in Quest will use numeric free response answers that you type in. The following example is a numeric type question on a learning module slide, but these questions can appear on all types of Quest assignments.

- If your instructor has allowed retries, you will be given 7 attempts

- Most solution answers are at least six digits (unless significant figures are relevant to the question/otherwise denoted)

- For credit your answer must be within 1% of the correct answer, unless tolerance is otherwise denoted (so entering in four digits to the right of the decimal is usually sufficient)

- Start with at least four significant digits for numeric entry; your response must be within 1% of the correct answer unless otherwise designated

- Scientific notation may use the format of "e" or "x10^"

- Comma use is fine.

- Do not use symbols in solutions (ie do not use $ in monetary solutions, but you can write 'dollars'-or the specified 'answer in units of ---- ' stated in the question, after your numeric answer).

- If offered, use the function pallet. If you don't see the pallet, plan on entering an actual number calculated out or simple expression (ex: 3x-5).

For applicable practice, your professor may opt to include a short 3 part question ( sig fig practice , #222082 ) for you to get use to what is and is not acceptable:

Note that if you get a 'that response has already been entered' message, try to use another way to say the same thing (ie, if used 10^, try e). If you continue to get the 'that response has already been entered' accept that it is not correct and try again. This is a safeguard in place so you don't spend all your tries insisting on an answer that is incorrect.

Confluence Documentation | Web Privacy Policy | Web Accessibility

Task Search

Iceborne walkthrough: assigned quests.

This page contains a full list of every assigned quest to be found within Iceborne. Information on assigned quests can be found on the corresponding monster page that Assigned Quest has you fighting, with the links in the table leading to those monster pages.

Also see: Clutch Claw - Tips, Tutorial , or watch the video above!

| Assigned Quest | Master Rank Level | Hunter Master Rank Requirement | Monster | Area | Unlocks | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR 1 | MR 1 or Higher | This quest is triggered in an Expedition into the Hoarfrost Reach | ||||

| MR 1 | MR 2 or Higher | This quest is triggered in an Expedition into the Hoarfrost Reach | ||||

| MR 2 | MR 3 or Higher | |||||

| MR 2 | MR 4 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 2 | MR 4 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 3 | MR 6 or Higher | Your next objective following this quest will be an investigation into the Ancient Forest, this investigation will unlock and | ||||

| MR 3 | MR 7 or Higher | to unlock and | This quest only appears once you've gone on an investigation into the Ancient Forest after finishing | |||

| MR 3 | MR 7 or Higher | to unlock and | This quest only appears once you've gone on an investigation into the Ancient Forest after finishing . | |||

| MR 3 | MR 9 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 3 | MR 9 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 3 | MR 11 or Higher | This quest is a repel mission for | ||||

| MR 4 | MR 12 or Higher | |||||

| MR 4 | MR 13 or Higher | |||||

| MR 4 | MR 14 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 4 | MR 14 or Higher | to unlock | ||||

| MR 4 | MR 16 or Higher | Seliana Supply Cache | This is another repel mission for Velkhana centered in a special arena map near Seliana called the Seliana Supply Cache. | |||

| MR 5 | MR 17 or Higher | |||||

| MR 5 | MR 18 or Higher | You'll need to enter into an expedition into the Elder's Recess after completing to unlock this quest. After completion, you'll need to look for tracks for the monster in the next quest, before the quest will trigger. | ||||

| MR 5 | MR 19 or Higher | You'll need to look for tracks for the monster in the next quest, before the quest will trigger. Similarly, after the quest, you'll need to find tracks of the monster in for that quest to trigger as well. | ||||

| MR 5 | MR 20 or Higher | Namielle | You'll need to find tracks of the monster in for the quest to trigger. | |||

| MR 6 | MR 21 or Higher | Origin Isle | and technically constitute the same quest, however, dying on once you've completed does not result in starting from the beginning of both quests. | |||

| MR 6 | MR 22 or Higher | Origin Isle | and technically constitute the same quest, however, dying on once you've completed does not result in starting from the beginning of both quests. | |||

| Quests below this constitute as post-credits, endgame content. | ||||||

| MR 6 | MR 24 or Higher | The quest for this monster is triggered by leveling up the Ancient Forest Section of the Guiding Lands. | ||||

| Sleep Now in the Fire | MR 6 | MR 49 or Higher | Master Rank: Tempered and Tempered | This quest triggers one you've leveled your Master rank up to level 49 and acts as a level cap holding you at MR49 until completed. | ||

Up Next: A Guide to the Guiding Lands - Monster Hunter World: Iceborne's End Game

Top guide sections.

- Beginner's Guide to Monster Hunter World

- How to get the Frozen Speartuna Greatsword - Trophy Fishin' Event Quest

- Iceborne Expansion

- Iceborne Changes - Update Ver. 10.11 and More

Was this guide helpful?

In this guide.

WebQuest: An Inquiry-oriented Approach in Learning

The rise in online learning brings renewed interest in WebQuests. As an authentic, scaffolded, and inquiry-based activity, a WebQuest is an educational superstar. It utilizes essential resources and captures the attention of the students. Not only are students able to reflect on their own learning, but they also develop a richer understanding between topics.

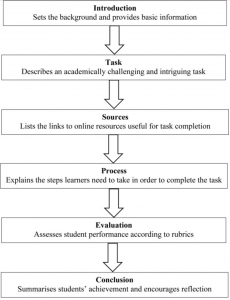

The origins of WebQuest can be traced all the way back to 1995, when Bernie Dodge, a professor at San Diego State University, dreamed of using the newly accessible Internet as a tool in education. He thought that students could research ideas online in order to solve problems by summarizing the information found. WebQuest is treated as “an inquiry-oriented activity in which some or all of the information that learners interact with comes from resources on the Internet, optionally supplemented with videoconferencing” (Dodge, 1997). He believed that they would need to follow six modules in order for this technological application to be successful: Introduction, Task, Resources, Process, Evaluation, and Conclusion . The instructor will first present the topic (Introduction) while providing details of the activities to be completed by the students (Task). Then, web links will be provided to ensure that all information is accurate and reliable (Resources), and the instructor will list the steps to complete the task successfully (Process). Finally, instructors provide a rubric to evaluate a student’s performance on the task (Evaluation), and the outcomes are summarized after everyone reflects on their learning journey (Conclusion). As March (2004) put it:

A WebQuest is a scaffolded learning structure that uses links to essential resources on the World Wide Web and an authentic task to motivate students’ investigation of a central, open-ended question, development of individual expertise and participation in a final group process that attempts to transform newly acquired information into a more sophisticated understanding. The best WebQuests do this in a way that inspires students to see richer thematic relationships, facilitate a contribution to the real world of learning and reflect on their own metacognitive processes (p. 2).

See also: Teaching with Blogs

WebQuest Types

This process can be lengthy, so Dodge classified WebQuests into two levels: long-term and short-term WebQuests.

Long-term WebQuests can be used for:

- Summative evaluation

- One specific idea within a bigger concept

- In-depth analysis of one topic

- End of unit assessment

A long-term WebQuest is a big project that would usually be assigned towards the end of a unit. The learner should have had the opportunity to thoroughly analyze information and make conclusions on the topic. They will typically demonstrate their understanding with an essay, an assignment, or a creative artifact.

As the name suggests, Short-term WebQuests were meant to be completed in a smaller amount of time. They are used for a brief review of a large amount of information or as an introduction to new topics in class.

Short-term WebQuests can be used for:

- Technology skill building

- Link analysis and reflection

- To introduce a new topic

- To explore a new idea

- Review of anterior knowledge

- Review for an evaluation

See also: Using Wikis in Education

WebQuest benefits

Why should you want to use Webquests? There are three invaluable benefits to implementing a WebQuest in your classroom.

- WebQuests promote collaboration. They are often done in small groups and students must share the responsibility in order to complete the task. Students learn conflict-resolution strategies as well as critical thinking skills, which is currently a key goal of the American state standards in public education.

- WebQuests are versatile. This tool can be used in many ways: as a review, a summative evaluation, or an exploratory activity. Students become more competent at using technology and are motivated to complete the work. WebQuests also eliminate the need for some pre-teaching of skills, as the web links and resources have already been vetted.

- WebQuests can easily be differentiated to support various students . As inclusive classrooms become the norm, the instructor may find that their class consists of students with various levels of exceptionalities. WebQuests can be modified to accommodate basic tasks for some students and expand on the expectations for others.

Building a WebQuest

Section 1 – Introduction

Just as an author would write a juicy introduction to hook their audience, the instructor is attempting to pique the attention of their students with a small paragraph. This is where they would outline the Guiding Question (also known as Essential Question or Big Question) that will direct the course of the WebQuest. One way to pique the interest of the students is by creating a scenario that they must solve, which draws them into the lesson. For example, the instructor might set the scene by stating that the students are now detectives looking to find the author of this mysterious and compelling poetry.

Section 2 – Task

The task is essentially the learning goal that the students are trying to achieve. After the instructor captures their interest in the first section, they outline the task, which is the performance that will guide the entire learning journey. It is important that the instructor clearly describes the expectations for the activities. If the learner is unsure of what the final result should look like, they will not be successful.

Section 3 – Process

This section outlines the steps that the students will take in order to achieve the WebQuest. In order to answer the Guiding Question, learners must research online using the resources supplied by the instructor. This means that the process itself must include clear explanations, steps, and the appropriate tools for them to accomplish the task. Students will not be successful in this step unless the teacher also provides instructions on how to appropriately organize their research.

Section 4 – Evaluation

If the instructor explicitly stated the criteria for the task in section two, there should be no surprises when the students arrive at the evaluation section. The instructor will have already prepared a rubric or a set of standards by which a student’s performance will be marked. Students should be aware if their grade is dependent on a group or an individual performance, and know what needs to be demonstrated in order to meet the standards. Gaps in learning should be clearly outlined, and both the student and the instructor should be aware of the next steps in order to meet the learning goal .

Section 5 – Conclusion

The WebQuest finishes with a conclusion, which offers both the teacher and the learners a chance for reflection. They are able to review the knowledge gained throughout the process and summarize their newfound understanding. It is possible to extend the activity with further questioning, but a simpler option would be to encourage them to make connections to other ideas.

Optional Section – Teacher Page

At the end of the WebQuest, an instructor may choose to add information related to the lesson that may help other teachers implement the same activity. This could include rubrics, possible learning goals , student work, and challenges that came up throughout the learning journey.

See also: How to Use Concept Maps

- Dodge, B. (1997). Some thoughts about WebQuests. https://webquest.org/sdsu/about_webquests.html

- March, T. (2004). What are WebQuests (really)?

I am a professor of Educational Technology. I have worked at several elite universities. I hold a PhD degree from the University of Illinois and a master's degree from Purdue University.

Similar Posts

Problem-based learning (pbl).

What is Problem-Based Learning (PBL)? PBL is a student-centered approach to learning that involves groups of students working to solve a real-world problem, quite different from the direct teaching method of a teacher…

Definitions of Instructional Technology

What is instructional technology? What is instructional design? Are the term Instructional Technology and Educational Technology considered synonymous? Instructional technology is the branch of education concerned with the scientific study of instructional design and development. The…

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Together with Edward Gurst, David Krathwohl, Max Englehart and Walter Hill, psychologist Benjamin Bloom released Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in 1956. This framework would prove to be valuable to teachers and instructors everywhere…

Scaffolding in Education

What is Scaffolding? Scaffolding in instruction is when a teacher supports students throughout the learning process. The instructor gradually introduces new ideas, building on each prior step and knowledge. As students learn new…

Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction

Heralded as a pioneer in educational instruction, Robert M. Gagné revolutionized instructional design principles with his WW II-era systematic approach, often referred to as the Gagné Assumption. The general idea, which seems familiar…

How to Create Effective Multiple Choice Questions

There are many advantages to using multiple choice (MC) questions as an evaluation / assessment strategy. They are easy to set up, easy to mark, and allow teachers to cover a wide range…

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply —use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Assignments

Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine

Introduction

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

- You may be returning to study after a break

- You may have come from an exam based assessment system and never written an assignment before

- Maybe you have written assignments but would like to improve your processes and strategies

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write and edit your assignments. It begins with an explanation of how to analyse an assignment task and start putting your ideas together. It continues by breaking down the components of academic writing and exploring the elements you will need to master in your written assignments. This is followed by a discussion of paraphrasing and synthesis, and how you can use these strategies to create a strong, written argument. The chapter concludes with useful checklists for editing and proofreading to help you get the best possible mark for your work.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that before you begin researching and writing your assignments you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements. This will help make your research process more efficient and effective. Check your subject information such as task sheets, criteria sheets and any additional information that may be in your subject portal online. Seek clarification from your lecturer or tutor if you are still unsure about how to begin your assignments.

The task sheet typically provides key information about an assessment including the assignment question. It can be helpful to scan this document for topic, task and limiting words to ensure that you fully understand the concepts you are required to research, how to approach the assignment, and the scope of the task you have been set. These words can typically be found in your assignment question and are outlined in more detail in the two tables below (see Table 19.1 and Table 19.2 ).

Table 19.1 Parts of an Assignment Question

| Topic words | These are words and concepts you have to research and write about. |

| Task words | These will tell you how to approach the assignment and structure the information you find in your research (e.g., discuss, analyse). |

| Limiting words | These words define the scope of the assignment, e.g., Australian perspectives, relevant codes or standards or a specific timeframe. |

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

Table 19.2 Task words

| Give reasons for or explain something has occurred. This task directs you to consider contributing factors to a certain situation or event. You are expected to make a decision about why these occurred, not just describe the events. | the factors that led to the global financial crisis. | |

| Consider the different elements of a concept, statement or situation. Show the different components and show how they connect or relate. Your structure and argument should be logical and methodical. | the political, social and economic impacts of climate change. | |

| Make a judgement on a topic or idea. Consider its reliability, truth and usefulness. In your judgement, consider both the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing arguments to determine your topic’s worth (similar to evaluate). | the efficacy of cogitative behavioural therapy (CBT) for the treatment of depression. | |

| Divide your topic into categories or sub-topics logically (could possibly be part of a more complex task). | the artists studied this semester according to the artistic periods they best represent. Then choose one artist and evaluate their impact on future artists. | |

| State your opinion on an issue or idea. You may explain the issue or idea in more detail. Be objective and support your opinion with reliable evidence. | the government’s proposal to legalise safe injecting rooms. | |

| Show the similarities and differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments or events. You are expected to provide a balanced response, highlighting similarities and differences. | the efficiency of wind and solar power generation for a construction site. | |

| Point out only the differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments or events. | virtue ethics and utilitarianism as models for ethical decision making. | |

| (this is often used with another task word, e.g. critically evaluate, critically analyse, critically discuss) | It does not mean to criticise, instead you are required to give a balanced account, highlighting strengths and weaknesses about the topic. Your overall judgment must be supported by reliable evidence and your interpretation of that evidence. | analyse the impacts of mental health on recidivism within youth justice. |

| Provide a precise meaning of a concept. You may need to include the limits or scope of the concept within a given context. | digital disruption as it relates to productivity. | |

| Provide a thorough description, emphasising the most important points. Use words to show appearance, function, process, events or systems. You are not required to make judgements. | the pathophysiology of Asthma. | |

| Highlight the differences between two (possibly confusing) items. | between exothermic and endothermic reactions. | |

| Provide an analysis of a topic. Use evidence to support your argument. Be logical and include different perspectives on the topic (This requires more than a description). | how Brofenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory applies to adolescence. | |

| Review both positive and negative aspects of a topic. You may need to provide an overall judgement regarding the value or usefulness of the topic. Evidence (referencing) must be included to support your writing. | the impact of inclusive early childhood education programs on subsequent high school completion rates for First Nations students. | |

| Describe and clarify the situation or topic. Depending on your discipline area and topic, this may include processes, pathways, cause and effect, impact, or outcomes. | the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the film industry in Australia. | |

| Clarify a point or argument with examples and evidence. | how society’s attitudes to disability have changed from a medical model to a wholistic model of disability. | |

| Give evidence which supports an argument or idea; show why a decision or conclusions were made. Justify may be used with other topic words, such as outline, argue. | Write a report outlining the key issues and implications of a welfare cashless debit card trial and make three recommendations for future improvements. your decision-making process for the recommendations. | |

| A comprehensive description of the situation or topic which provides a critical analysis of the key issues. | Provide a of Australia's asylum policies since the Pacific Solution in 2001. | |

| An overview or brief description of a topic. (This is likely to be part of a larger assessment task.) | the process for calculating the correct load for a plane. |

The criteria sheet , also known as the marking sheet or rubric, is another important document to look at before you begin your assignment. The criteria sheet outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The task or criteria sheet will also include the:

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

Task analysis and criteria sheets are also discussed in the chapter Managing Assessments for a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation .

What is academic writing?

Academic writing tone and style.

Many of the assessment pieces you prepare will require an academic writing style. This is sometimes called ‘academic tone’ or ‘academic voice’. This section will help you to identify what is required when you are writing academically (see Table 19.3 ). The best way to understand what academic writing looks like, is to read broadly in your discipline area. Look at how your course readings, or scholarly sources, are written. This will help you identify the language of your discipline field, as well as how other writers structure their work.

Table 19.3 Comparison of academic and non-academic writing

| Is clear, concise and well-structured | Is verbose and may use more words than are needed |

| Is formal. It writes numbers under twenty in full. | Writes numbers under twenty as numerals and uses symbols such as “&” instead of writing it in full |

| Is reasoned and supported (logically developed) | Uses humour (puns, sarcasm) |

| Is authoritative (writes in third person- This essay argues…) | Writes in first person (I think, I found) |

| Utilises the language of the field/industry/subject | Uses colloquial language e.g., mate |

Thesis statements

Essays are a common form of assessment that you will likely encounter during your university studies. You should apply an academic tone and style when writing an essay, just as you would in in your other assessment pieces. One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. A thesis statement may not be relevant for some questions, if you are unsure check with your lecturer. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task . Your thesis statement may even contain some of the key words or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Let’s your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The contention is the position you are taking in relation to the chosen content.

Your thesis statement helps you to structure your essay. It plays a part in each key section: introduction, body and conclusion.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task, this is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement. These tips below are based on the requirements usually needed for an essay assignment, however, they can be applied to other assignment types.

Writing introductions

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Usually, your introduction is approximately 10% of your total assignment word count. It is much easier to write your introduction once you have drafted your body paragraphs and conclusion, as you know what your assignment is going to be about. An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic things:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic

- A thesis statement (see section above)

- An outline of your essay structure

- An indication of any parameters or scope that will/ will not be covered, e.g. From an Australian perspective.

The below example demonstrates the four different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) This essay will discuss the impact of information technology on the communication of health professionals. 3) First, the provision of information technology for the educational needs of nurses will be discussed. 4) This will be followed by an explanation of the significant effects that information technology can have on the role of general practitioner in the area of public health. 5) Considerations will then be made regarding the lack of knowledge about the potential of computers among hospital administrators and nursing executives. 6) The final section will explore how information technology assists health professionals in the delivery of services in rural areas . 7) It will be argued that information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/ overview | 2 Indicates the scope of what will be covered | 3-6 Outline of the main ideas (structure) | 7 The thesis statement

Note : The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. Similar to your introduction, your conclusion should be approximately 10% of the total assignment word length. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Remember, do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) It is evident, therefore, that not only do employees need to be trained for working in the Australian multicultural workplace, but managers also need to be trained. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for migrant workers, so that they become more familiar with the English language, Australian communication norms and the Australian work culture. 3) In addition, Australian native English speakers need to be made aware of the differing cultural values of their workmates; particularly the different forms of non-verbal communication used by other cultures. 4) Furthermore, all employees must be provided with clear and detailed guidelines about company expectations. 5) Above all, in order to minimise communication problems and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance, understanding and cooperation in the multicultural workplace, managers need to have an effective knowledge about their employees. This will help employers understand how their employee’s social conditioning affects their beliefs about work. It will develop their communication skills to develop confidence and self-esteem among diverse work groups. 6) The culturally diverse Australian workplace may never be completely free of communication problems, however, further studies to identify potential problems and solutions, as well as better training in cross cultural communication for managers and employees, should result in a much more understanding and cooperative environment.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers . | 2-5 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 6 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs