Showing papers on "Object-oriented programming published in 2019"

The functional perspective.

36 citations

Hoobas: A highly object-oriented builder for molecular dynamics

23 citations

Invited: Actors Revisited for Time-Critical Systems

20 citations

Programmers do not favor lambda expressions for concurrent object-oriented code

19 citations

FluidSim: Modular, Object-Oriented Python Package for High-Performance CFD Simulations

13 citations

SDNSOC: Object Oriented SDN Framework

12 citations

A Brief Overview of Software Reuse and Metrics in Software Engineering

11 citations

Validating object-oriented software at design phase by achieving MC/DC

10 citations

Ant Lion optimizer for state based object oriented testing

Collaborative strategy for teaching and learning object-oriented programming course: a case study at mostafa stambouli mascara university, algeria.

9 citations

Object-oriented model of the seismic vulnerability of the fuel distribution network in coastal British Columbia

Lessons in persisting object data using object-relational mapping, on attributes of objects in object-oriented software analysis, an object-oriented semantic slam system towards dynamic environments for mobile manipulation, design decisions under object-oriented approach: a thematic analysis from the abstraction point of view, induction, coinduction, and fixed points in pl type theory., a new object-oriented framework for solving multiphysics problems via combination of different numerical methods, backus: comprehensive high-performance research software engineering approach for simulations in supercomputing systems., model based object-oriented software testing, godexpo: an automated god structure detection tool for golang, seamless object-oriented requirements, creation of biological databases using object-oriented system analysis, implementation of phpmailer with smtp protocol in the development of web-based e-learning prototype, does cyclic learning have positive impact on teaching object-oriented programming, to be, or not to be: that is the recursive question, an automatic and intelligent approach for supporting teaching and learning of software engineering considering design smells in object-oriented programming, on the students’ misconceptions in object-oriented language constructs, serialization in object-oriented programming languages, estimation of complexity by using an object oriented metrics approach and its proposed algorithm and models.

On the site

- Computer Systems Series

Research Directions in Object-Oriented Programming

Edited by Gul Agha , David Beech , Daniel G. Bobrow , Ole-Johan Dahl , Joseph A. Goguen , Brent Hailpern , Kenneth M. Kahn , Ole Lehrmann Madsen , David Maier , Andrea Skarra , Harold L. Ossher , Steven Reiss , Herbert Schwetman , Reid Smith , Alan Snyder , Peter Wegner and Stanley Zdonik

ISBN: 9780262192644

Pub date: October 9, 1987

- Publisher: The MIT Press

- 9780262192644

- Published: October 1987

Out of print

Other Retailers:

- MIT Press Bookstore

- Penguin Random House

- Barnes and Noble

- Bookshop.org

- Books a Million

- Amazon.co.uk

- Waterstones

- Description

Once a radical notion, object-oriented programming is one of today's most active research areas.

Once a radical notion, object-oriented programming is one of today's most active research areas. It is especially well suited to the design of very large software projects involving many programmers all working on the same project. The original contributions in this book will provide researchers and students in programming languages, databases, and programming semantics with the most complete survey of the field available. Broad in scope and deep in its examination of substantive issues, the book focuses on the major topics of object-oriented languages, models of computation, mathematical models, object-oriented databases, and object-oriented environments. The object-oriented languages include Beta, the Scandinavian successor to Simula (a chapter by Bent Kristensen, whose group has had the longest experience with object-oriented programming, reveals how that experience has shaped the group's vision today); CommonObjects, a Lisp-based language with abstraction; Actors, a low-level language for concurrent modularity; and Vulcan, a Prolog-based concurrent object-oriented language. New computational models of inheritance, composite objects, block-structure layered systems, and classification are covered, and theoretical papers on functional object-oriented languages and object-oriented specification are included in the section on mathematical models. The three chapters on object-oriented databases (including David Maier's "Development and Implementation of an Object-Oriented Database Management System," which spans the programming and database worlds by integrating procedural and representational capability and the requirements of multi-user persistent storage) and the two chapters on object-oriented environments provide a representative sample of good research in these two important areas.

Research Directions in Object-Oriented Programming is included in the Computer Systems series, edited by Herb Schwetman.

Gul Agha is Director of the Open Systems Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science.

Daniel G. Bobrow is a Research Fellow in the Intelligent Systems Laboratory, Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, editor-in-chief of the Journal of Artificial Intelligence , and Chair of the Governing Board of the Cognitive Science Society.

Reid Smith is Director of the Schlumberger Laboratory for Computer Science.

Peter Wegner is Professor in the Department of Computer Science at Brown University.

Related Books

- DOI: 10.36227/techrxiv.16677259

- Corpus ID: 246871888

Object Oriented Programming: Concepts, Limitations and Application Trends

- Nehul Singh , S. Chouhan , Karan Verma

- Published in 5th International Conference… 25 September 2021

- Computer Science

- 2021 5th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Networks (ISCON)

Figures from this paper

2 Citations

Exploring polymorphism: flexibility and code reusability in object-oriented programming, a new data structure for digital optimization of the educational profile of the state universities in bulgaria, 23 references, object oriented programming, python as a first programming language, object-oriented programming: some history, and challenges for the next fifty years, using c++ to write automation controller software, an evaluation framework and comparative analysis of the widely used first programming languages, object-oriented programming applied to the development of structural analysis and optimization software, current challenges in practical object-oriented software design, cognitive differences between procedural programming and object oriented programming, achievements and weaknesses of object-oriented databases, the c++ programming language in cheminformatics and computational chemistry, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Ranking of problems and solutions in the teaching and learning of object-oriented programming

- Published: 08 February 2022

- Volume 27 , pages 7205–7239, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Luz E. Gutiérrez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8229-7175 1 ,

- Carlos A. Guerrero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8164-9650 2 &

- Héctor A. López-Ospina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8144-6394 3

4710 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

This study describes the most relevant problems and solutions found in the literature on teaching and learning of object-oriented programming (OOP). The identification of the problem was based on tertiary studies from the IEEE Xplore, Scopus, ACM Digital Library and Science Direct repositories. The problems and solutions identified were ranked through the multi-criteria decision methods DEMATEL and TOPSIS in order to determine the best solutions to the problems found and to apply these results in the academic context. The main contribution of this study was the categorization of OOP problems and solutions, as well as the proposal of strategies to improve the problem. Among the most relevant problems it was found: 1) difficulty in understanding, teaching and implementing object-orientation, 2) difficulties related to understanding classes and 3) difficulty in understanding object-oriented relationships. After doing the multicriteria analysis, it was found that the most important solutions to face the problems found in the teaching of OOP were: 1) use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards and 2) emphasize on basic programming concepts and introduce the object-oriented paradigm at an early point in the curriculum. As a conclusion, it was evidenced that there is coherence between the literary guarantee that gives support to the problems and solutions in the teaching of OOP presented in this study and the approaches that experts in the area of development highlight as relevant when they identify weaknesses in the process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Modelling Competency in the Field of OOP: From Investigating Computer Science Curricula to Developing Test Items

Contribution to Teaching Programming Based on “Object-First” Style at College of Polytechnics Jihlava

Teachers’ Perspectives on Learning and Programming Environments for Secondary Education

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

For Martins et al. ( 2018 ) programming is the basis of a professional on systems. For such reason, it is required that programming courses are based on a model that allows putting into practice all the proposed theoretical approach. According to Popat and Starkey ( 2019 ) programming skills are 21st-century competences every person should enhance.

Martins et al. ( 2018 ) state that a learning process in the programming area should allow the student to identify a real problem and transform it into a sequence of activities that will finally be translated into a language. According to Qian et al. ( 2020 ) the teacher is the one in charge of guiding the students in this process of problem transformation, making the complexity implicit in the programming decrease and motivate them to continue. In addition, Dorn et al. ( 2018 ) affirm that although the teachers are facilitators, knowing the difficulties of a programming teaching process can allow them to implement pedagogical strategies that help the students in their training process.

Now, for Azmi et al. ( 2016 ) facilitating the teaching of algorithm design and programming is an activity that not only requires technical knowledge from the teacher, but also skills to motivate the students to overcome the obstacles that arise in their training. According to Martins et al. ( 2018 ) a non-motivated student is likely to increase the dropout statistics.

Ismail et al. ( 2018 ) state that the current teaching processes are not the most adequate, as is the case of “Teaching based solely on referring to the books seen to fail to attract the students’ interest in learning”, the authors state that “every educator should practice effective teaching methods to produce optimum outcomes. The success of a student lies in the way of teaching. Thus, it is important for teachers to study appropriate teaching methods that suit with the targeted students." Therefore, according with Draz et al. ( 2016 ) and Sarkar et al. ( 2016 ) traditional methods can create resistance in the student that will eventually be transformed into fear of programming.

In the work by Yang et al. ( 2015 ) and Qian and Lehman ( 2017 ) concepts such as variables, cycles and conditional structures are challenges for a student in training. However, in programming the most critical points are in abstract thinking and object-oriented programming (Hadar, 2013 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Krpan et al., 2015 ). A wrong training process leads the students to take a reactive attitude and to develop the idea that they do not have the ability or competences to continue in software development (Dorn et al., 2018 ).

More recent research work suggests that a deep knowledge of the teaching programming problems could allow the establishment of processes based on emerging methodologies such as the case of video games (Guerrero et al., 2020 ). These new teaching processes seek that the student generates a commitment and motivation to address the topics of study (Piteira et al., 2017 ).

Several paradigms such as structural programming, object-oriented programming, aspect-oriented programming, and reactive programming are identified in the programming area. This article will focus primarily on the object-oriented paradigm OOP.

Therefore, it is important to explore what factors affect the teaching and learning process of OOP within the context of every student and their environment. Thus, the following research question arises: What solutions could be prioritized in the resolution of problems in the teaching and learning of OOP?

The second section of this article describes the methods and materials used to identify and prioritize the OOP problem. The results section presents the most important findings related to the problem. The discussion section relates the observations of experts involved in the research and analysis of the results. Finally, the conclusions consolidate the contributions of the study.

2 Material and methods

2.1 procedure for identifying oop problems and solutions.

A systematic literature review was carried out in order to identify the problems and solutions present in the teaching-learning process of object-oriented programming This review took as a reference the guidelines of the protocol proposed by Kitchenham et al. ( 2007 ). The PICOC strategy (Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ) used in this research is presented below.

2.1.1 PICOC

According to Kitchenham and Charters ( 2007 ) the use of 5 criteria is suggested to define the research questions that will guide the search for the studies which will be part of the research: population, intervention, comparison, results, and context. These criteria are generally used in medicine and can be applied in the systems area. Population refers to the people affected by the intervention. The interventions which are usually a comparison between two or more alternative treatments. The outcomes are the clinical and economic factors that will be used to compare the interventions. The comparison refers to what the intervention is being compared with. The context refers to what is the context in which the intervention is delivered. The definition of each concept in the framework of this research is presented below:

Population: Corresponds to the literature related to topics that address the problems and solutions in the teaching-learning processes of object-oriented programming.

Intervention: The search string displayed in each one of the repositories made it possible to delimit the work to be done and established the field of intervention of the research.

Comparison: This concept was used in the present investigation when comparing the problems found.

Results: Identification of problems and solutions in the teaching-learning process of object-oriented programming.

Context: It is made up of the works that have as their foundation the study of object-oriented programming.

2.1.2 SLR Research Questions

The research questions proposed for carrying out the systematic literature review, which are supported by the PICOC criteria, are presented below.

Q1: What are the problems related to the learning and teaching of object-oriented programming?

Q2: What are the solutions to the problems found in the teaching and learning of object-oriented programming?

2.1.3 Search process

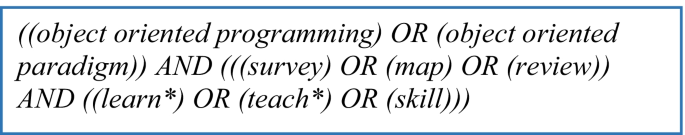

Once the research questions were defined and the keywords were identified, the generic search string was established to obtain the primary sources of the study. Fig. 1 presents the defined query string. This string is intended to identify tertiary papers that focus their studies towards teaching, learning or object-oriented paradigm skills. The "*" is used as a catch-all symbol to replace any combination of the words learn and teach, for example, it would apply learning and teaching.

Search string

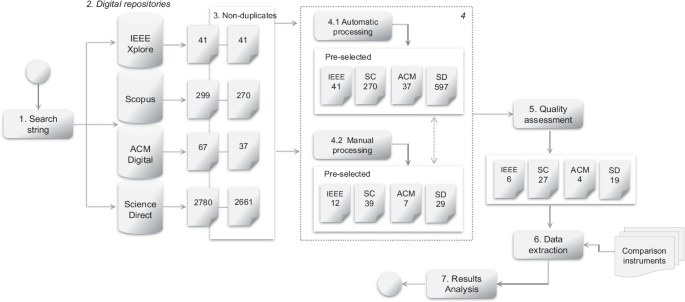

The work carried out by Brereton et al. ( 2007 ) and Kitchenham and Charters ( 2007 ) was established as a reference for the selection of the search repositories. The selected repositories were IEEE Xplore, Scopus, ACM Digital Library and Science Direct.

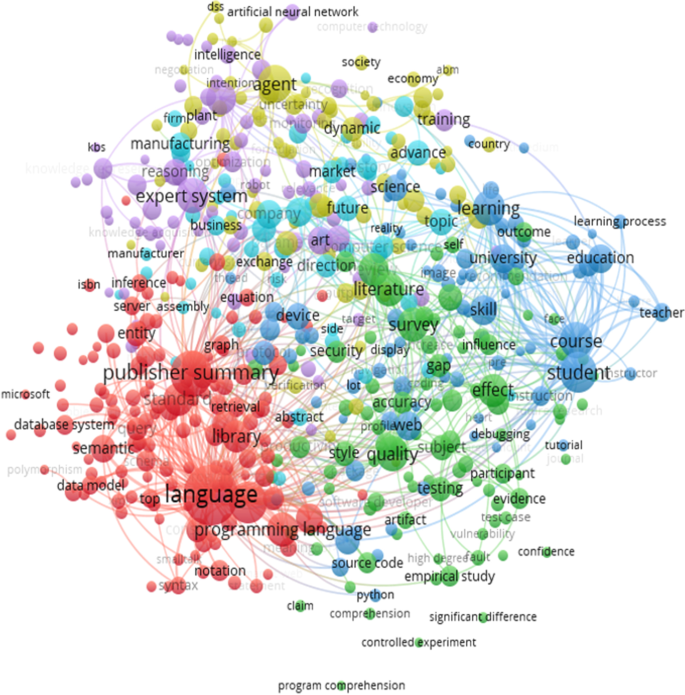

3009 non-duplicate studies were found with the execution of the search string. For the Science Direct repository, an automatic filtering of the identified papers was performed with the VOSviewer tool (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010 ). The data obtained with the processing tool allowed to generate a term co-occurrence map that defines the most important topics for the present study in the Science Direct repository. The topics classified by the VOSviewer tool are shown in Fig. 2 .

Science Direct terms co-occurrence network map

Due to the limited number of papers, automatic processing was not performed with the VOSviewer tool in the IEEE, Scopus and ACM repositories. The automatic processing performed with VOSviewer significantly reduced the number of pre-selected studies, identifying 945 relevant investigations for the present study.

2.1.4 Selection and exclusion criteria

The following selection criteria were applied to the title and abstract metadata of the 945 articles preselected in the previous stage.

SC1: Studies that address problems in the teaching-learning of object-oriented programming.

SC2: Studies that reference bibliography where the problems of object-oriented programming are identified.

After applying the selection criteria 87 papers remained. Then, exclusion criteria were applied to these 87 papers. As a result of this process 56 studies remained which formed the conceptual basis of the present investigation. The applied exclusion criteria are shown below:

EC1: Incomplete studies that do not present the details of the research.

EC2: Articles that do not allow access to their information.

The complete process from definition of the search string, selection of repositories and selection and exclusion criteria application, is presented in Fig. 3 and Table 1 .

Search and selection process

2.2 Identified problems

A comparison matrix was made after analyzing the 56 selected studies. It allowed the identification of 14 problems related to the teaching and learning process of object-oriented programming. Each of these problems is described below.

Difficulty in understanding object and its dynamic nature (D01) . This problem is referred as the students’ conception of the term object as a simple record of a database. The students do not understand the aspect of behavior and variation as a function of the object’s state (Hadar, 2013 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; Xinogalos, 2015 ; Yang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulties related to understanding classes (D02). This difficulty is described as the complexity presented by the students when assimilating the static nature and depth of classes. It is challenging for them to understand the hierarchy and the identification of correct classes. The students even refer to the difficulty in distinguishing between class and object. They generally assimilate class as a collection of objects, rather than an abstraction (Benander et al., 2004 ; Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Gorschek et al., 2010 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hubwieser & Mühling, 2011 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Musil & Richta, 2017 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 , Sien, 2011 , Sien & Chong, 2011 , Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 , Thomasson et al., 2006 ; Xinogalos, 2015 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulty in understanding the concept of method (D03). In this case it is referred as the complexity presented when assimilating the concept of method, there is no clarity on how to make the method calls. The students do not know how to determine the number of methods needed or what labels or names to assign to them. They do not understand how to reuse methods or their proper placement (Berges et al., 2012 ; Gorschek et al., 2010 ; Hubwieser & Mühling, 2011 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

Difficulty in understanding, teaching and implementing object-orientation (D04). This problem is specified as the challenge of performing object-oriented analysis, design, and programming. The students present difficulties when adopting the object-oriented paradigm, because their initial formative process is generally based on purely structural programming. The modular nature of the object-oriented paradigm is conceived as a challenge for educators, since in this process it is common for students to assimilate erroneous conceptions and to present problems in understanding and implementing object-oriented standards (Abbasi et al., 2017 ; Anniroot & de Villiers, 2012 ; Arif, 2000 ; Barr et al., 1999 ; Benander et al., 2004 ; Black et al., 2013 ; Cetin, 2013 ; Dale, 2006 ; Fedorowicz & Villeneuve, 1999 ; García Perez-Schofield et al., 2008 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hosanee & Panchoo, 2015 ; Hubwieser & Mühling, 2011 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Tahat, 2014 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Kunkle & Allen, 2016 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Mazaitis, 1993 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Pei et al., 2010 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Seng & Yatim, 2014 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien, 2011 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Streib & Soma, 2010 ; Tan et al., 2014 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; Turner et al., 2010 ; Xinogalos, 2015 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulty in understanding object-oriented relationships (D05). It refers to the difficulty that the students have when understanding and implementing object-oriented relationships, such as association, dependency, generalization / specialization-inheritance, composition and aggregation. These problems are common due to the learners’ lack of experience in relation to the object-oriented programming paradigm. The students generally present difficulties in the process of modeling these relationships, and consequently in the implementation and application of concepts that are often conceived as complex (Barr et al., 1999 ; Benander et al., 2004 ; Berges et al., 2012 ; Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Dale, 2006 ; Gorschek et al., 2010 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hosanee & Panchoo, 2015 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Musil & Richta, 2017 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien, 2011 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2013 ).

Difficulty in understanding polymorphism and overload (D06). In this case it is indicated the high level of complexity the concepts of polymorphism and overload have at the moment of initiating a student into the programming area (Benander et al., 2004 ; Dale, 2006 ; Hosanee & Panchoo, 2015 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulty in understanding encapsulation (D07). This problem is related to the assimilation of several misconceptions related to understanding encapsulation, modularity and information hiding (Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Gorschek et al., 2010 ; Hubwieser & Mühling, 2011 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Turner et al., 2010 ; Xinogalos, 2015 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ).

Complexity with the programming languages and tools used in the teaching and learning of object-orientation (D08). This problem is specified as the difficulty that students present with the use of debugging, navigation, testing and documentation tools. The change in technologies, paradigms and languages makes the learning process even more difficult (Barr et al., 1999 ; Benander et al., 2004 ; Bishop-Clark, 1995 ; García Perez-Schofield et al., 2008 ; Jiang et al., 2004 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 , Kiss, 2013 , Mazaitis, 1993 , Moons & De Backer, 2009 , Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Radenski, 2006 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ; T.-C. Yang et al., 2015 ; Zainal et al., 2012 ; X. Zhang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulty in teaching and understanding general programming topics (D09). This difficulty refers to the challenges that the students face when understanding algorithms and basic programming concepts. Concepts such as variables, parameters, functions, and control structures are often considered difficult topics (Benander et al., 2004 ; Berges et al., 2012 ; Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Cetin, 2013 ; Dale, 2006 ; Govender, 2009 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hubwieser & Mühling, 2011 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Jiang et al., 2004 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Kiss, 2013 ; Krpan et al., 2015 ; Kunkle & Allen, 2016 ; Mazaitis, 1993 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Moussa et al., 2016 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Radenski, 2006 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien, 2011 ; Tan et al., 2014 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; T.-C. Yang et al., 2015 ; Zainal et al., 2012 ; J. Zhang et al., 2013 ).

Difficulty in developing abstract thinking (D10). This problem is related to the difficulty when understanding and solving real-world problems. The students frequently face processes where they must coordinate the acquired abstract thinking skills and the assimilated knowledge. This integration of skills and concepts challenges the student and, in many cases, makes the training process difficult (Anniroot & de Villiers, 2012 ; Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Black et al., 2013 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Krpan et al., 2015 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien, 2011 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ).

Difficulty in understanding software analysis and design (D11). It refers to the inability the students have to represent and design real-world problems. Students find challenges when using analysis and design techniques. They find it difficult to apply design concepts in Unified Modeling Language (UML) and to make use of related techniques and patterns (Anniroot & de Villiers, 2012 ; Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Bishop-Clark, 1995 ; Black et al., 2013 ; Hadar, 2013 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Tahat, 2014 ; Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Rajashekharaiah et al., 2016 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Sien, 2011 ; Sien & Chong, 2011 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; Turner et al., 2010 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ).

Difficulty in understanding reuse (D12) . This is a quite recurrent problem. The learners do not understand when and where to reuse and they confuse this concept with the tendency to copy code, generating redundancy and duplication of information (Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

Difficulty with project administration and management methodologies and techniques (D13). This problem refers to understanding activities that include time and resource restrictions. It is confusing for the learners to know when to stop, advance or finish the project (Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Sheetz, 2002 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

Difficulty in software implementation and maintenance (D14). This last problem is related to the difficulty students have in starting the software and in adding, subtracting or modifying the code to be adapted. These challenges demand significant amounts of time and effort, which generally causes apathy and disinterest in the process (Karahasanović et al., 2007 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

2.3 Identified solutions

According to the literature review, six possible solutions to the problems of teaching-learning of object-oriented programming were found. Each of the possible solutions is described below.

Use of tools that support knowledge transfer (S01). This solution is described as an emerging proposal where virtualization, animation, online sessions and more channels that support knowledge transfer are used. Additionally, it is emphasized on the use of game-related tools and more suitable languages for teaching (Abbasi et al., 2017 ; Govender, 2009 ; Jordine et al., 2015 ; Kiss, 2013 ; Mazaitis, 1993 ; Moons & De Backer, 2009 ; Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Olsson & Mozelius, 2015 ; Radenski, 2006 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Seng & Yatim, 2014 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; Tan et al., 2014 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ; T.-C. Yang et al., 2015 ).

Emphasize basic programming concepts and introduce the object-oriented paradigm at an early point in the curriculum (S02). It is considered that introducing the object-oriented paradigm at an early point in the curriculum make the students better understand the associated concepts. In addition, the basic concepts, such as class and object, must be emphasized, because they tend to be confused (Biddle & Tempero, 1998 ; Hundley, 2008 ; Mazaitis, 1993 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

Make use of UML diagrams, design patterns and simplified methodologies (S03). The use of the unified modeling language helps the students visualize and formulate programming concepts (Hundley, 2008 ; Jiang et al., 2004 ; Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Sheetz et al., 1997 ; J. Yang et al., 2018 ).

Minimize aspects of the problem mastery, while learning object-oriented fundamentals (S04). This solution refers to emphasizing the resolution and mastery of the problem, putting aside the complexity of programming languages or development environments (Tegarden & Sheetz, 2001 ).

Use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards (S05). This solution is referred as the use of active learning techniques that involves peer tutoring, role-play activities, workshops, exemplifications, use of metaphors, and concept mapping (Jordine et al., 2015 ; Mazaitis, 1993 ; Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Nelson et al., 1997 ; Sajaniemi et al., 2007 ; Sanders et al., 2008 ; Sien, 2011 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; T.-C. Yang et al., 2015 ; Zainal et al., 2012 ).

Change the way of teaching (S06). This solution refers to the change of teaching strategies, adapting the approach to the difficulties, achievements and mistakes of others. Thus, the learning is based on the students’ experiences (Govender, 2009 ; Moons & De Backer, 2013 ; Tan et al., 2014 ; Thomasson et al., 2006 ; T.-C. Yang et al., 2015 ).

2.4 Prioritization of the identified problems

The DEMATEL (Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) multi-criteria method is used for the prioritization and classification of the most relevant OOP problems (Espinosa & Salinas, 2013 ; Jeong & Ramírez-Gómez, 2018 ; López-Ospina et al., 2017 ). This method allows finding the relationships between the problems of this study, as well as their hierarchization depending on the decision-making context. In other words, it is assumed that there is a relationship between the problems. DEMATEL is a method that is considered effective for identifying the key components of the cause-effect chain of a complex system. It seeks to evaluate the interdependent relationships between factors and find the most critical or relevant ones through a visual structural model. This method provided the causal relationship between OOP problems and their importance ranking (Alzahrani et al., 2018 ; Aldowah et al., 2020 ). The steps of the DEMATEL method that were carried out in the present study are detailed below.

2.4.1 Step 1: Generation of the direct relationship matrix

The evaluation of the direct relationships of the problems was carried out by three experts in the field of object-oriented programming. The selected profiles were those who met: 1) experience of more than 5 years in the academic environment, 2) experience of more than 5 years in application development in the business sector and 3) professionals from different universities. Table 2 describes the experts’ profiles.

The scale defined in Table 3 was used for the evaluation of the problems in order to find the influence relationship of the 14 problems identified in the teaching and learning of OOP. This scale is the one generally used in the applications of the DEMATEL method.

The 14 x 14 direct relationships matrix A was generated based on the information recorded by the experts (the problems have been described in section 2.2 Identified problems). Each expert evaluated the influence of each problem against the other ones to define the scale of influence among them. From this process, 3 evaluation matrices emerged, which later were averaged to generate the consolidated initial relationships matrix. Table 4 presents matrix A with the averages obtained.

2.4.2 Step 2: Normalization of the direct relationships matrix

The normalized matrix M was generated using equations ( 1 ) and ( 2 ). The objective of the transformation is to have a matrix with a norm less than 1. The results of M are presented in Table 5 .

2.4.3 Step 3: Obtaining the total relationship matrix

Subsequently, the total relationship matrix S was generated using equation ( 3 ). Table 6 presents the data of matrix S . It contains the direct and indirect relationships between the problems.

2.4.4 Step 4: Determine the cause group and effect group

Based on equations ( 4 ), ( 5 ) and ( 6 ) a vector with the sum of the elements per rows of the matrix S , named D , was generated; then a vector with the sum of the elements per columns of S , named R , was generated.

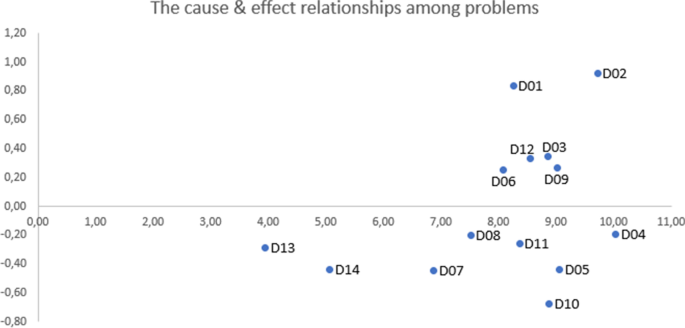

Table 7 presents the calculation values of D+R and D-R. The positive values of D-R represent causes and the negative values are interpreted as the problems that are effect. A problem that is a Cause is one that originates or initiates the problem, whereas if a problem is an Effect, it means that it is the consequence of another problem. These results can be seen in Table 8 .

2.4.5 Step 5: Set the threshold value and obtain the impact diagram

The threshold value was set at 0.2863 for matrix S based on equation ( 7 ).

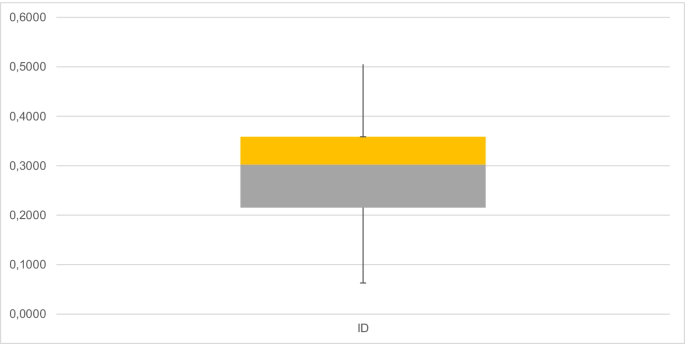

The diagram in Fig. 4 shows the distribution of the matrix S values. The minimum value is 0.063, 1st quartile is 0.2154, 2nd quartile is 0.3027, 3rd quartile is 0.3586 and the maximum value is 0.5049. As it can be seen in Fig. 4 , there are no outliers of the S values. Additionally, the threshold value is less than the median and corresponds to the 41st percentile. It means that 41% of the scores are less than or equal to the threshold. This implies that 80 relationships among problems should be analyzed as key in the teaching-learning process. Given this number of relationships, it is proposed to do the aggregate causality analysis of Fig. 5 .

Box plot of matrix S

D+R vs D-R relationship

Fig. 5 describes the causal diagram is built with the horizontal axis (D + R) called "Prominence" and the vertical axis (D - R) called “Relation”. The horizontal axis shows the relative importance of each problem. On the other hand, vertical axis, splits problems into cause or effect. If (D - R) is positive, is a cause problem. Otherwise, it is an effect problem. For that reason, causal diagrams can visualize the causal relationships of problems into a visible structural model. According to the results obtained, D02’s problem is the cause factor with the highest importance. On the other hand, D10’s problem is the strongest effect factor and has a high weight. The problems classified as cause (D01, D02, D03, D06, D09, D12) have high weighting. However, some effect problems have a low importance.

2.4.6 Step 6: Weighting of problems

In this step, the problems that have the greatest weight in the teaching and learning process of OOP were identified. Equations ( 8 ) and ( 9 ) were used to weight the problems (Jeong & Ramírez-Gómez, 2018 ). The result of applying the equations is presented in Table 9 and Table 10 .

After applying the weighting and standardization coefficients, the problems with the greatest weight in the teaching and learning process of OOP were identified (see Table 11 ).

2.5 Selection of solutions strategies

It is important to identify the possible solutions for the problems found in the process of teaching and learning of OOP. There is evidence in the analyzed literature where authors such as Gómez et al. ( 2020 ); Zhang et al. ( 2019 ) and Yi and Fang ( 2018 ) presented significant results when selecting solution strategies through multi-criteria methods such as TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution). The TOPSIS method handles the concept of the ideal solution and the anti-ideal solution when choosing decision alternatives. Its premise is based on the fact that a given alternative is located at the shortest distance from a positive ideal solution and at the greatest distance from a negative ideal solution. An ideal solution is defined as an ideal set of levels with respect to all the considered attributes of a given problem, even when the ideal solution is usually impossible or not feasible to obtain (Sun et al., 2016 ). The steps used in the implementation of the TOPSIS method during the selection process of solution strategies analyzed in this study are listed below.

2.5.1 Step 1: Construction of the decision matrix

The same experts who supported the application process of the DEMATEL method were consulted for the evaluation of the matrix of solutions vs problems with the TOPSIS method. Each expert evaluated it based on the following guidelines: 1) identify how much influence a solution could have on each problem, 2) identify how much it could contribute to solving the problem and 3) how feasible it was to implement that solution. Each expert evaluated the influence of the solutions in each of the 14 problems, with values from 0 to 4, where 0 represents that there is no influence and 4 that there is a total influence of the solution to address the problem. The scale used is found in Table 3 . From this process 3 matrices emerge, one for each evaluator. These matrices are averaged and the decision matrix presented in Table 12 is obtained.

2.5.2 Step 2: Normalization of the decision matrix

Subsequently, the decision matrix was normalized based on Equation ( 10 ). Table 13 presents the results of the normalized matrix.

2.5.3 Step 3: Construction of the weighted normalized decision matrix

The weighting vector was obtained with the DEMATEL method. The weighted normalized decision matrix was calculated by multiplying each W j by each V ij . Where W is the weight vector for each problem (Table 14 ), and V is the normalized decision matrix (Table 13 ). The results of this calculation are presented in Table 15 .

2.5.4 Step 4: Determination of the ideal positive and negative solution

The objective of this step was to identify the positive and negative ideal solution, in order to calculate how close the OOP solutions were to the ideal ones. Formulas ( 11 ) and ( 12 ) were used for this process.

The results of Table 16 were obtained after applying formulas ( 11 ) and ( 12 ). For the case study of this article, the objective was to maximize the values of OOP solutions.

2.5.5 Step 5: Calculation of distance measurements

In this step the positive and negative distance measures were calculated for each solution applying formulas ( 13 ) and ( 14 ).

The results of this arithmetic procedure are presented in Table 17 .

2.5.6 Step 6: Calculation of relative proximity

The last step in the TOPSIS method was the calculation of relative proximity, a procedure based on equation ( 15 ).

Table 18 presents the results of the application of the relative proximity equation. Subsequently, the values were organized from the highest to the lowest weight, in order to identify the solutions that were closest to the solution ideal as described in Table 20 .

3.1 Influence relationship between the OOP problems

According to the DEMATEL results, Table 19 describes how much one problem affects another and how much it is affected by another. For the case of problem "D02 - Difficulties related to the understanding classes", it influences to a high degree problem "D04 - Difficulty in understanding, teaching and implementing object-orientation". This would be an expected result because, if a student does not handle the concept of classes correctly, it will be reflected when understanding the object-oriented paradigm.

Ten problems affect problem "D04 - Difficulty in understanding, teaching and implementing object orientation", indicating that this problem is the one that receives the most influence from the other factors. The problem that most affects the other problems is “D02 - Difficulties related to understanding classes”, with an occurrence of 11 out of 14.

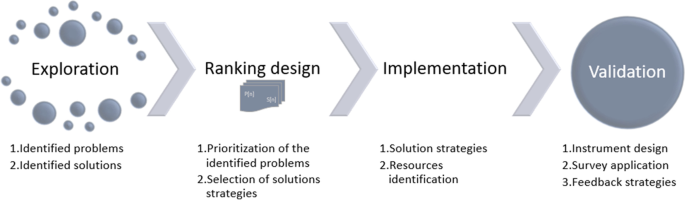

3.2 Towards a generic framework

The construction of the Ranking allowed to define a framework for implementing solutions to problems in the object-oriented programming teaching. As a general contribution of this research, the steps to implement strategies that help in the object-oriented programming teaching-learning process are presented. Fig. 6 describes the stages and activities to be carried out for this purpose.

Generic framework

The validation stage is part of the next phase of this research in which instruments to evaluate the perception of students and teachers after applying the suggested strategies will be built. From this activity a feedback process will emerge for the proper calibration of such instruments and strategies.

3.3 Strategies to implement the best solutions

As it can be seen in Table 20 , the top ranked solutions is “S05 - Use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards”, followed by “S02 - Emphasize basic programming concepts and introduce the object-oriented paradigm at an early point in the curriculum”, and in the third position “S01 - Use of tools that support knowledge transfer”.

The solutions that are closest to the ideal are the best strategies to help minimize the 14 problems in this study (Table 20 ). Recommendations for the implementation of the solutions ranked in the top 3 positions are provided below.

3.3.1 Strategies for the use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards (S05)

For the implementation of the solution "Use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards", three strategies are proposed as it can be seen in Table 21 .

3.3.2 Strategies to emphasize basic programming concepts and introduce the object-oriented paradigm at an early in the curriculum (S02).

For the implementation of the solution "Emphasize basic programming concepts and introduce the object-oriented paradigm at an early point in the curriculum", four strategies are proposed as it can be seen in Table 22 .

3.3.3 Strategies for the use of tools that support knowledge transfer (S01).

For the implementation of the solution "Use of tools that support knowledge transfer", three strategies are proposed as it can be seen in Table 23 .

4 Discussion

The problems and solutions identified in the literature review phase present some suggestions by the panel of experts. For expert 1 problems D11, D13 and D14 are not part of the scope of OOP teaching and learning. Based on this statement, he recommends that these problems should not be taken into account in future research. He also mentions that there are relevant problems that were not explicitly identified in the findings, such as the programming language syntax requirement. By having a diversity of programming languages, each one will have its own statements and typing rules, making the teaching-learning process of OOP difficult. Another factor that influences the teaching of OOP is the pedagogical preparation of teachers. Instructors are usually experts in informatics or computer science; however, teaching methodology is not an area of their expertise.

On the other hand, expert 2 affirms that, although problems D13 and D14 are not directly related to the teaching and learning of OOP, it is important to evaluate them within the framework of a complete process of analysis of this problem. For expert 2, the problems identified group together the OOP universe.

Regarding the level of complexity of each problem, expert 3 states that the problems identified in the literature review are at different levels, it means that there are generic problems and other more specific ones. In this regard, he recommends working with problems D01 to D10.

Regarding the solutions found, Expert 1 considers that appropriate preparation in methodological and pedagogical issues is important in the teaching staff that guides programming topics.

Experts 1 and 2 suggest that ideally solution "S06 - Change the way of teaching" would be the optimal solution for the OOP teaching and learning problems. However, in the practice it is not feasible to implement it, because it implies the construction of individual and personalized teaching activities.

Expert 3 considers that solutions S01 and S05 have a great similarity in their concept, for this reason, they can be considered as the same solution when implementing them.

When analyzing the results of Table 11 , it is possible to see that the problem with the greatest weight is D04 “Difficulty in understanding, teaching and implementing object orientation”. According to the decision matrix of the TOPSIS method this problem may be solved by implementing S02 solution. This solution is very important, because the basis of OOP lies in understanding the concept of class and object; and as this research has proved these concepts are often confused.

The second most important problem was D02 “Difficulties related to understanding classes”. This problem, according to the matrix in Table 12 , can be addressed from 3 solutions: S02, S03 and S05 where only S03 did not appear in the ranking of solutions provided by the TOPSIS. However, it must be taken into account for this specific problem.

In general, the solutions of the ranking have in common that the change in the teaching and learning methodologies of OOP is prevailing. It is not advisable to maintain the same strategies for lectures and to present merely theoretical concepts. It is important to have students involved directly in the process and not continue thinking that they are actors who only receive information. As Ismail et al. ( 2018 ) well stated it, “This gamification approach to education is considered as one of the new teaching era that it is capable of improving students' achievement”.

5 Conclusions

This article presents an analysis of the OOP problem in 3 phases. The first phase of the study sought to identify the problems and solutions of OOP. This process of problem recognition was carried out through a systematic literature review in high-impact repositories. The second phase was the hierarchization of the OOP problems by means of the DEMATEL method; with this method, it was possible to identify the most relevant problems in the teaching-learning process of OOP and the relationship level between these problems. The third phase was the making up of the solutions ranking that was developed through the TOPSIS method, as well as the proposal of implementing strategies for each of the solutions located in the first three positions of the ranking. The contribution of this research can be focused on 3 aspects: 1) List of problems categorized from the greatest to the least relevance. 2) Ranking of solutions and 3) Strategies to implement the best solutions. The conclusions of this work according to the phases of the investigation are listed below.

It was possible to obtain information about the problems, causes and solutions of the teaching-learning process of object-oriented programming from the systematic literature review process carried out. These results show the interest of the academic community in presenting alternatives to implement strategies to improve this process.

According to the results obtained when applying the multicriteria techniques, the problem “D02 - Difficulties related to understanding classes” was identified as a cause in the DEMATEL method and had a high weighting value. This indicates the importance of emphasizing this subject in the classes, in order to generate adequate conceptual bases for programming students.

Based on the TOPSIS method results, it is found that the top ranked solution is "Strategies for the use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards". This finding reinforces the need for a change in OOP teaching strategies. For such reason, the use of tools related to computer games and the search for new teaching strategies that motivate students in their formative process can support the learning of object-oriented programming.

It was evidenced that there is coherence between the literary guarantee that supports the problems and solutions in the teaching of OOP presented in this study and the approaches that experts in the development area highlight as relevant when identifying weaknesses in the process.

The use of multi-criteria decision methods made it possible to identify the relationships between the OOP problems, as well as to prioritize the problems and solutions.

Taking into account the current world situation with the Covid-19 pandemic, the application of different teaching-learning strategies in all areas of study is imperative. In the case of OOP, strategies aimed at the use of tools that support knowledge transfer (S01) and the use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards (S05) are particularly important. It is because work mediated by technology and strengthening of individual skills is a priority with the current situation, where remote work and virtuality will be the new study scenarios.

6 Future research direction

This study laid the conceptual foundations in the identification of problems and solutions based on literature review. For this reason, it is necessary to carry out an analysis with a representative sample group, where OOP teachers and students of this subject help to identify which, from their experience, are the problems and solutions for the teaching of OOP by means of an evaluation instrument.

At the university where the authors belong, teacher evaluation processes are carried out twice each year, specifically, once for each academic semester. These results can feed the problems database that arise in the teaching of OOP.

The next phase of this research consists of implementing strategies to respond to the solution “Strategies for the use of active learning techniques and intrinsic rewards (S05)”. At this stage, a video game will be developed at the University of origin to teach concepts such as method, polymorphism, and encapsulation.

Abbasi, S., Kazi, H., & Khowaja, K. (2017). A systematic review of learning object oriented programming through serious games and programming approaches. 2017 4th IEEE International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS) , 2018 - Janua , 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETAS.2017.8277894

Aldowah, H., Al-Samarraie, H., Alzahrani, A. I., & Alalwan, N. (2020). Factors affecting student dropout in MOOCs: a cause and effect decision-making model. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 32 (2), 429–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-019-09241-y

Article Google Scholar

Alzahrani, A. I., Al-Samarraie, H., Eldenfria, A., & Alalwan, N. (2018). A DEMATEL method in identifying design requirements for mobile environments: students’ perspectives. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 30 (3), 466–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9176-2

Anniroot, J., & de Villiers, M. R. (2012). A study of Alice: A visual environment for teaching object-oriented programming. Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference on Information Systems 2012 , 2 , 251–258.

Arif, E. M. (2000). A methodology for teaching object-oriented programming concepts in an advanced programming course. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 32 (2), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/355354.355367

Azmi, S., Iahad, N. A., & Ahmad, N. (2016). Attracting students’ engagement in programming courses with gamification. 2016 IEEE Conference on E-Learning, e-Management and e-Services (IC3e) , 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1109/IC3e.2016.8009050

Barr, M., Holden, S., Phillips, D., & Greening, T. (1999). An exploration of novice programming errors in an object-oriented environment. Working Group Reports from ITiCSE on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education - ITiCSE-WGR ’99 , Part F1291 (4), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1145/349316.349392

Benander, A., Benander, B., & Sang, J. (2004). Factors related to the difficulty of learning to program in Java—an empirical study of non-novice programmers. Information and Software Technology, 46 (2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-5849(03)00112-5

Berges, M., Mühling, A., & Hubwieser, P. (2012). The gap between knowledge and ability. Proceedings of the 12th Koli Calling International Conference on Computing Education Research - Koli Calling ’12 , 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1145/2401796.2401812

Biddle, R., & Tempero, E. (1998). Teaching programming by teaching principles of reusability. Information and Software Technology, 40 (4), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-5849(98)00040-8

Bishop-Clark, C. (1995). Cognitive style, personality, and computer programming. Computers in Human Behavior, 11 (2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0747-5632(94)00034-F

Black, A. P., Bruce, K. B., Homer, M., Noble, J., Ruskin, A., & Yannow, R. (2013). Seeking Grace: A New Object-Oriented Language for Novices. Proceeding of the 44th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education - SIGCSE ’13 , 129. https://doi.org/10.1145/2445196.2445240

Brereton, P., Kitchenham, B. A., Budgen, D., Turner, M., & Khalil, M. (2007). Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. Journal of Systems and Software, 80 (4), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.009

Cetin, I. (2013). Visualization: a tool for enhancing students’ concept images of basic object-oriented concepts. Computer Science Education, 23 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08993408.2012.760903

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Dale, N. B. (2006). Most difficult topics in CS1: Results of an Online Survey of Educators. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 38 (2), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/1138403.1138432

Dorn, N., Berges, M., Capovilla, D., & Hubwieser, P. (2018). Talking at Cross Purposes - Perceived Learning Barriers by Students and Teachers in Programming Education. Proceedings of the 13th Workshop in Primary and Secondary Computing Education , 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1145/3265757.3265769

Draz, A., Abdennadher, S., & Abdelrahman, Y. (2016). Kodr: A Customizable Learning Platform for Computer Science Education. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics): Vol. 9891 LNCS (pp. 579–582). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45153-4_67

Espinosa, F. F., & Salinas, G. E. (2013). Selección de Estrategias de Mejoramiento de las Condiciones de Trabajo para la Función Mantenimiento Utilizando la Metodología MCDA Constructivista. Información Tecnológica, 24 (3), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642013000300008

Fedorowicz, J., & Villeneuve, A. O. (1999). Surveying object technology usage and benefits: A test of conventional wisdom. Information & Management, 35 (6), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(98)00098-6

García Perez-Schofield, J. B., García Roselló, E., Ortín Soler, F., & Pérez Cota, M. (2008). Visual Zero: A persistent and interactive object-oriented programming environment. Journal of Visual Languages & Computing, 19 (3), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvlc.2007.11.002

Gómez, J. C. O., Tabares-Urrea, N., & Ramírez-Flórez, G. (2020). AHP difuso para la selección de un proveedor 3PL considerando el riesgo operacional. Revista EIA , 17 (33), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.24050/reia.v17i33.1329

Gorschek, T., Tempero, E., & Angelis, L. (2010). A large-scale empirical study of practitioners’ use of object-oriented concepts. Proceedings of the 32nd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering - ICSE ’10 , 1 , 115. https://doi.org/10.1145/1806799.1806820

Govender, I. (2009). The learning context: Influence on learning to program. Computers & Education, 53 (4), 1218–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.005

Guerrero, C. A., Gutiérrez, L. E., & Cuervo, K. D. (2020). Los videojuegos como estrategia para incrementar la motivación y alcance de logros en procesos de aprendizaje. Memorias La Formación de Ingenieros: Un Compromiso Para El Desarrollo y La Sostenibilidad , 1–9. https://acofipapers.org/index.php/eiei/article/view/750/755

Hadar, I. (2013). When intuition and logic clash: The case of the object-oriented paradigm. Science of Computer Programming, 78 (9), 1407–1426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scico.2012.10.006

Hosanee, Y., & Panchoo, S. (2015). An enhanced software tool to aid novices in learning Object Oriented Programming (OOP). 2015 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS) , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCCS.2015.7374197

Hubwieser, P., & Mühling, A. (2011). What students (should) know about object oriented programming. Proceedings of the Seventh International Workshop on Computing Education Research - ICER ’11 , 77. https://doi.org/10.1145/2016911.2016929

Hundley, J. (2008). A review of using design patterns in CS1. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Southeast Regional Conference on XX - ACM-SE 46 , 30. https://doi.org/10.1145/1593105.1593113

Ismail, M. E., Sa’adan, N., Samsudin, M. A., Hamzah, N., Razali, N., & Mahazir, I. I. (2018). Implementation of The Gamification Concept Using KAHOOT! Among TVET Students: An Observation. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1140 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1140/1/012013

Jeong, J. S., & Ramírez-Gómez, Á. (2018). Optimizing the location of a biomass plant with a fuzzy-DEcision-MAking Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (F-DEMATEL) and multi-criteria spatial decision assessment for renewable energy management and long-term sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182 , 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.072

Jiang, K., Maniotes, J., & Kamali, R. (2004). A different approach of teaching introductory visual basic course. Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Information Technology Education - CITC5 ’04 , 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1145/1029533.1029586

Jordine, T., Liang, Y., & Ihler, E. (2015). A Mobile Device Based Serious Gaming Approach for Teaching and Learning Java Programming. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (IJIM), 9 (1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v9i1.4380

Karahasanović, A., Levine, A. K., & Thomas, R. (2007). Comprehension strategies and difficulties in maintaining object-oriented systems: An explorative study. Journal of Systems and Software, 80 (9), 1541–1559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.10.041

Kiss, G. (2013). Teaching Programming in the Higher Education not for Engineering Students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103 , 922–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.414

Kitchenham, B., Brereton, P., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., & Linkman, S. (2007). Protocol for a Tertiary study of Systematic Literature Reviews and Evidence-based Guidelines in IT and Software Engineering . https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Protocol-for-a-Tertiary-study-of-Systematic-Reviews-Kitchenham-Brereton/bf3910a40028240b821790738896954638932e33#paper-header

Kitchenham, B., & Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering . https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/525444systematicreviewsguide.pdf

Krpan, D., Mladenović, S., & Rosić, M. (2015). Undergraduate Programming Courses, Students’ Perception and Success. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174 , 3868–3872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1126

Kunkle, W. M., & Allen, R. B. (2016). The Impact of Different Teaching Approaches and Languages on Student Learning of Introductory Programming Concepts. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 16 (1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/2785807

Lewis, T. L., Rosson, M. B., & Pérez-Quiñones, M. A. (2004). What do the experts say? Teaching Introductory Design from an Expert’s Perspective. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 36 (1), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1145/1028174.971405

López-Ospina, H., Quezada, L. E., Barros-Castro, R. A., Gonzalez, M. A., & Palominos, P. I. (2017). A method for designing strategy maps using DEMATEL and linear programming. Management Decision, 55 (8), 1802–1823. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2016-0597

Martins, V. F., de Almeida Souza Concilio, I., & de Paiva Guimarães, M. (2018). Problem based learning associated to the development of games for programming teaching. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 26 (5), 1577–1589. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.21968

Mazaitis, D. (1993). The object-oriented paradigm in the undergraduate curriculum: a survey of implementations and issues. ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 25 (3), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1145/165408.165432

Moons, J., & De Backer, C. (2009). Rationale Behind the Design of the EduVisor Software Visualization Component. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science, 224 (C), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcs.2008.12.049

Moons, J., & De Backer, C. (2013). The design and pilot evaluation of an interactive learning environment for introductory programming influenced by cognitive load theory and constructivism. Computers & Education, 60 (1), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.08.009

Moussa, W. E., Almalki, R. M., Alamoudi, M. A., & Allinjawi, A. (2016). Proposing a 3d interactive visualization tool for learning oop concepts. 2016 13th Learning and Technology Conference (L&T) , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/LT.2016.7562861

Musil, M., & Richta, K. (2017). Contribution to Teaching Programming Based on “Object-First” Style at College of Polytechnics Jihlava. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing , 511 AISC , 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46535-7_17

Nelson, H. J., Irwin, G., & Monarchi, D. E. (1997). Journeys up the mountain: Different paths to learning object-oriented programming. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 7 (2), 53–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8022(96)00024-0

Olsson, M., & Mozelius, P. (2015). Visualization of concepts and algorithms in programming education - A design theoretic multimodal perspective. Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Learning, ICEL , 2015 - Janua (June), 257–264.

Pei, T., Shih, H., Zheng, W., Skelton, G., & Leggette, E. (2010). Integrating Self Regulating Learning With An Object Oriented Programming Course. 2010 Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings , 15.770.1-15.770.13. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2--16444

Piteira, M., Costa, C. J., & Aparicio, M. (2017). CANOE e Fluxo: Determinantes na adoção de curso de programação online gamificado. RISTI - Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação , 25 (25), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.17013/risti.25.34-53

Popat, S., & Starkey, L. (2019). Learning to code or coding to learn? A systematic review. Computers & Education, 128 (October 2018), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.005

Qian, Y., Hambrusch, S., Yadav, A., Gretter, S., & Li, Y. (2020). Teachers’ Perceptions of Student Misconceptions in Introductory Programming. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58 (2), 364–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633119845413

Qian, Y., & Lehman, J. (2017). Students’ Misconceptions and Other Difficulties in Introductory Programming. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 18 (1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3077618

Radenski, A. (2006). “Python First”: A Lab-Based Digital Introduction to Computer Science. Proceedings of the 11th Annual SIGCSE Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education - ITICSE ’06 , 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1145/1140124.1140177

Rajashekharaiah, K. M. M., Pawar, M., Patil, M. S., Kulenavar, N., & Joshi, G. H. (2016). Design Thinking Framework to Enhance Object Oriented Design and Problem Analysis Skill in Java Programming Laboratory: An Experience. 2016 IEEE 4th International Conference on MOOCs, Innovation and Technology in Education (MITE) , February 2018 , 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITE.2016.048

Sajaniemi, J., Byckling, P., & Gerdt, P. (2007). Animation Metaphors for Object-Oriented Concepts. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science, 178 (1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcs.2007.01.037

Sanders, K., Boustedt, J., Eckerdal, A., McCartney, R., Moström, J. E., Thomas, L., & Zander, C. (2008). Student understanding of object-oriented programming as expressed in concept maps. Proceedings of the 39th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education - SIGCSE ’08 , 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1145/1352135.1352251

Sarkar, S. P., Sarker, B., & Hossain, S. K. A. (2016). Cross platform interactive programming learning environment for kids with edutainment and gamification. 2016 19th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT) , 218–222. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCITECHN.2016.7860198

Seng, W. Y., & Yatim, M. H. M. (2014). Computer Game as Learning and Teaching Tool for Object Oriented Programming in Higher Education Institution. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 123 , 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1417

Sheetz, S. D. (2002). Identifying the difficulties of object-oriented development. Journal of Systems and Software, 64 (1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0164-1212(02)00019-5

Sheetz, S. D., Irwin, G., Tegarden, D. P., Nelson, H. J., & Monarchi, D. E. (1997). Exploring the Difficulties of Learning Object-Oriented Techniques. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14 (2), 103–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1997.11518167

Sien, V. Y. (2011). Implementation of the Concept-Driven Approach in an Object-Oriented Analysis and Design Course. In 2013 12th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering: Vol. 6627 LNCS (pp. 55–69). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21210-9_6

Sien, V. Y., & Chong, D. W. K. (2011). Threshold concepts in object-oriented modelling. Electronic Communications of the EASST , 52 , 1–11. https://doi.org/10.14279/tuj.eceasst.52.763

Streib, J. T., & Soma, T. (2010). Using contour diagrams and JIVE to illustrate object-oriented semantics in the Java programming language. Proceedings of the 41st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education - SIGCSE ’10 , 510–514. https://doi.org/10.1145/1734263.1734435

Sun, R., Zhang, B., & Liu, T. (2016). Ranking web service for high quality by applying improved Entropy-TOPSIS method. 2016 17th IEEE/ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD) , 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1109/SNPD.2016.7515909

Tahat, K. (2014). An Innovative Instructional Method for Teaching Object-Oriented Modelling. International Arab Journal of Information Technology, 11 (November), 540–549.

Google Scholar

Tan, J., Guo, X., Zheng, W., & Zhong, M. (2014). Case-based teaching using the Laboratory Animal System for learning C/C++ programming. Computers & Education, 77 , 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.003

Tegarden, D. P., & Sheetz, S. D. (2001). Cognitive activities in OO development. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 54 (6), 779–798. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.1999.0462

Article MATH Google Scholar

Thomasson, B. J., Ratcliffe, M. B., & Thomas, L. A. (2006). Improving the tutoring of software design using case-based reasoning. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 20 (4), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2006.07.002

Turner, S., Pérez-Quiñones, M. A., Edwards, S., & Chase, J. (2010). Peer Review in CS2: Conceptual Learning. Proceedings of the 41st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education - SIGCSE ’10 , 331. https://doi.org/10.1145/1734263.1734379

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84 (2), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Xinogalos, S. (2015). Object-Oriented Design and Programming. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 15 (3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/2700519

Yang, J., Lee, Y., & Chang, K. H. (2018). Evaluations of JaguarCode: A web-based object-oriented programming environment with static and dynamic visualization. Journal of Systems and Software, 145 (May), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.07.037

Yang, T.-C., Chen, S. Y., & Hwang, G.-J. (2015). The influences of a two-tier test strategy on student learning: A lag sequential analysis approach. Computers & Education, 82 (1), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.021

Yi, T., & Fang, C. (2018). A Novel Method of Complexity Metric for Object-Oriented Software. International Journal of Digital Multimedia Broadcasting, 2018 (6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7624768

Zainal, N. F. A., Shahrani, S., Yatim, N. F. M., Rahman, R. A., Rahmat, M., & Latih, R. (2012). Students’ Perception and Motivation Towards Programming. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 59 , 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.276

Zhang, J., Caldwell, E. R., & Smith, E. (2013). Learning the concept of Java inheritance in a game. Proceedings of CGAMES’2013 USA , 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/CGames.2013.6632635

Zhang, X., Crabtree, J. D., Terwilliger, M. G., & Redman, T. T. (2018). Assessing Students’ Object-Oriented Programming Skills with Java: The “Department-Employee” Project. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 60 (3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2018.1467243

Zhang, Y., Zhang, F., Zhu, H., & Guo, P. (2019). An Optimization-Evaluation Agricultural Water Planning Approach Based on Interval Linear Fractional Bi-Level Programming and IAHP-TOPSIS. Water, 11 (5), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11051094

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the assistance provided by Universidad Santo Tomás, Universidad del Norte and the program "Convocatoria de Doctorados Nacionales 785 de 2017". The authors would like to thank Universidad Santo Tomás and Universidad del Norte for allowing the articulation of an interdisciplinary team for the research project development. Thanks are extended to the experts who provided their valuable contributions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Universidad Santo Tomás. CAFP 002 SIST.2018-2 and Convocatoria Doctorados Nacionales 785. The funding bodies participated in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of System Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia

Luz E. Gutiérrez

Faculty of System Engineering, Universidad Santo Tomás, Tunja, Colombia

Carlos A. Guerrero

Department of Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia

Héctor A. López-Ospina

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Luz E. Gutiérrez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Carlos A. Guerrero: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Héctor A. López-Ospina: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luz E. Gutiérrez .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Consent to participate, consent for publication, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gutiérrez, L.E., Guerrero, C.A. & López-Ospina, H.A. Ranking of problems and solutions in the teaching and learning of object-oriented programming. Educ Inf Technol 27 , 7205–7239 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10929-5

Download citation

Received : 04 August 2021

Accepted : 31 January 2022

Published : 08 February 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10929-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Object-oriented programming

- Teaching-Learning

- Multi-criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Inheritance and Its Type in Object Oriented Programming Using C++

13 Pages Posted: 18 Sep 2019

Dr Mehul Patel

C P PATEL & F H SHAH COMMERCE COLLEGE

Date Written: September 10, 2019

Reusability is one of most important advantage of C++ programming language. C++ classes can be reused in several ways. Once the parent (Base) class has been written it can be modified by another programmer to suit their requirements. The main idea of inheritance is creating new classes, reusing the properties of the existing base class. The mechanism of deriving a new class (Child/Derived Class) from an Existing class (Base/Parent Class) is called inheritance. The old class is referred to as the base (Parent) class and the new class is called the derived class (Child) or subclass. A derived class includes all features of the generic base class and then adds qualities specific to the derived class. This paper reflects the study of the Inheritance concept and its types using C++ (oops).

Keywords: Base (Parent) class, Reusability, Sub (Derived/Child) Class, Visibility Modes and Types of Inheritance

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Dr Mehul Patel (Contact Author)

C p patel & f h shah commerce college ( email ).

NEAR N S PATEL CIRCLE B/H OVERBRIDGE ANAND, GA GUJARAT 388001 India 8200593797 (Phone) 388001 (Fax)

HOME PAGE: http://www.cppfhscc.org

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, applied computing ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Object Oriented Programming Concepts Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Objects and object oriented programing, classes, structures and unions, inheritance, polymorphism.

Object oriented programming (OOP) is a programming concept that was invented to solve limitations of earlier programming paradigms. Therefore, it may be argued that OOP is a new approach to developing software. Whether OOP is an old or modern idea is open for debate. However, this paper focuses on the concepts that make up object oriented programming. It summarizes the relationship between structures, classes and unions, and OOP, and mentions the concepts of inheritance, objects, and polymorphism in OOP.

In the programming world, things are often viewed into two perspectives – data and actions or operations on these data. This viewpoint is inherent in object oriented programing. However, in OOP and unlike in a procedural programming approach, data and actions on data are further organized into modular units. These modular units are what is often referred to as objects. To develop a complete program, a programmer has to connect these objects. Therefore, the basic aspect of OOP design involves objects and interactions of these objects.

An object in OOP can be described simply as a group of data and operations on these data. As Horton (2010, p.507) has highlighted, an object is a data structure. An object in OOP sense is more or less like a physical or real-world object. Keogh, Keogh, and Giannini, (2004, p.230 ) have mentioned that an object is characterized by both state and behaviour. This similarities of objects to real things makes OOP a very powerful programming approach (Keogh, Keogh and Giannini, 2004, p.123).