“Inductive” vs. “Deductive”: How To Reason Out Their Differences

- What Does Inductive Mean?

- What Does Deductive Mean?

- Inductive Reasoning Vs. Deductive Reasoning

Inductive and deductive are commonly used in the context of logic, reasoning, and science. Scientists use both inductive and deductive reasoning as part of the scientific method . Fictional detectives like Sherlock Holmes are famously associated with methods of deduction (though that’s often not what Holmes actually uses—more on that later). Some writing courses involve inductive and deductive essays.

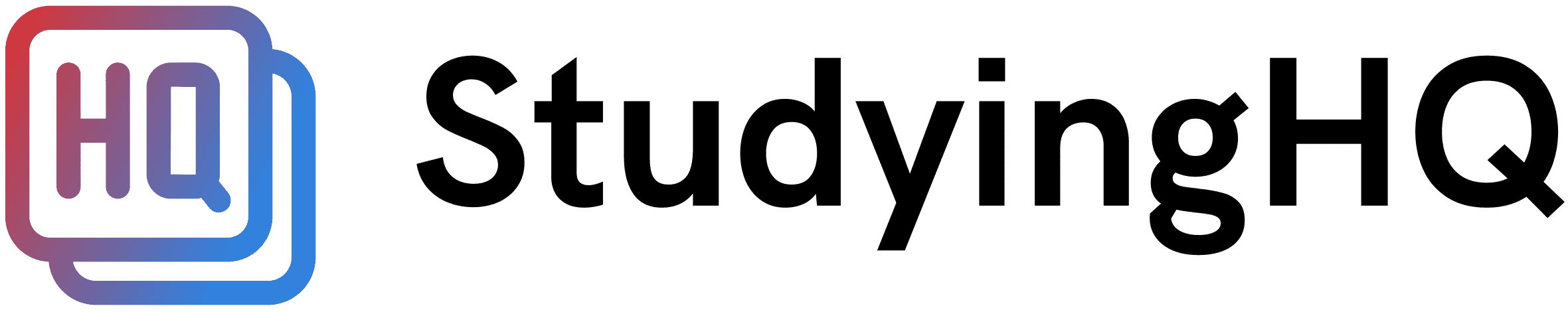

But what’s the difference between inductive and deductive ? Broadly speaking, the difference involves whether the reasoning moves from the general to the specific or from the specific to the general. In this article, we’ll define each word in simple terms, provide several examples, and even quiz you on whether you can spot the difference.

⚡ Quick summary

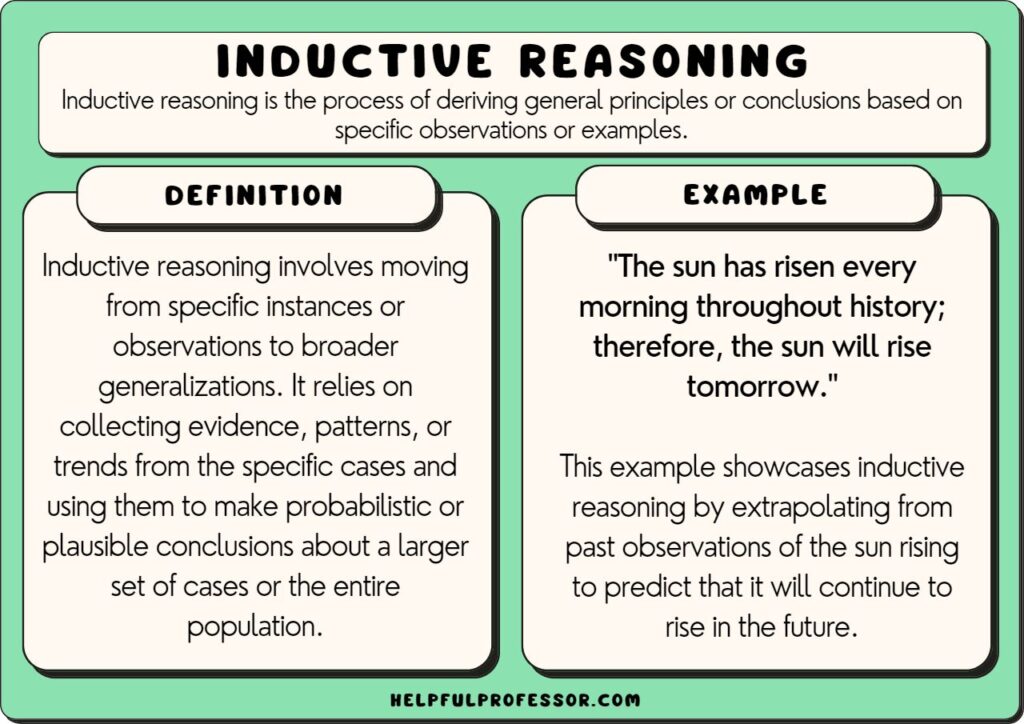

Inductive reasoning (also called induction ) involves forming general theories from specific observations. Observing something happen repeatedly and concluding that it will happen again in the same way is an example of inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning (also called deduction ) involves forming specific conclusions from general premises, as in: everyone in this class is an English major; Jesse is in this class; therefore, Jesse is an English major.

What does inductive mean?

Inductive is used to describe reasoning that involves using specific observations, such as observed patterns, to make a general conclusion. This method is sometimes called induction . Induction starts with a set of premises , based mainly on experience or experimental evidence. It uses those premises to generalize a conclusion .

For example, let’s say you go to a cafe every day for a month, and every day, the same person comes at exactly 11 am and orders a cappuccino. The specific observation is that this person has come to the cafe at the same time and ordered the same thing every day during the period observed. A general conclusion drawn from these premises could be that this person always comes to the cafe at the same time and orders the same thing.

While inductive reasoning can be useful, it’s prone to being flawed. That’s because conclusions drawn using induction go beyond the information contained in the premises. An inductive argument may be highly probable , but even if all the observations are accurate, it can lead to incorrect conclusions.

Follow up this discussion with a look at concurrent vs. consecutive .

In our basic example, there are a number of reasons why it may not be true that the person always comes at the same time and orders the same thing.

Additional observations of the same event happening in the same way increase the probability that the event will happen again in the same way, but you can never be completely certain that it will always continue to happen in the same way.

That’s why a theory reached via inductive reasoning should always be tested to see if it is correct or makes sense.

What else does inductive mean?

Inductive can also be used as a synonym for introductory . It’s also used in a more specific way to describe the scientific processes of electromagnetic and electrostatic induction —or things that function based on them.

What does deductive mean?

Deductive reasoning (also called deduction ) involves starting from a set of general premises and then drawing a specific conclusion that contains no more information than the premises themselves. Deductive reasoning is sometimes called deduction (note that deduction has other meanings in the contexts of mathematics and accounting).

Here’s an example of deductive reasoning: chickens are birds; all birds lay eggs; therefore, chickens lay eggs. Another way to think of it: if something is true of a general class (birds), then it is true of the members of the class (chickens).

Deductive reasoning can go wrong, of course, when you start with incorrect premises. For example, look where this first incorrect statement leads us: all animals that lay eggs are birds; snakes lay eggs; therefore, snakes are birds.

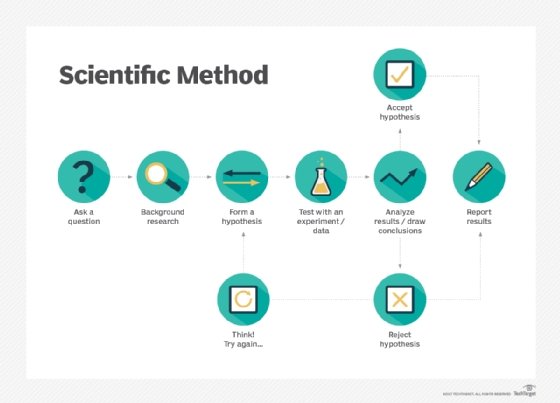

The scientific method can be described as deductive . You first formulate a hypothesis —an educated guess based on general premises (sometimes formed by inductive methods). Then you test the hypothesis with an experiment . Based on the results of the experiment, you can make a specific conclusion as to the accuracy of your hypothesis.

You may have deduced there are related terms to this topic. Start with a look at interpolation vs. extrapolation .

Deductive reasoning is popularly associated with detectives and solving mysteries. Most famously, Sherlock Holmes claimed to be among the world’s foremost practitioners of deduction , using it to solve how crimes had been committed (or impress people by guessing where they had been earlier in the day).

However, despite this association, reasoning that’s referred to as deduction in many stories is actually more like induction or a form of reasoning known as abduction , in which probable but uncertain conclusions are drawn based on known information.

Sherlock’s (and Arthur Conan Doyle ’s) use of the word deduction can instead be interpreted as a way (albeit imprecise) of referring to systematic reasoning in general.

What is the difference between inductive vs. deductive reasoning?

Inductive reasoning involves starting from specific premises and forming a general conclusion, while deductive reasoning involves using general premises to form a specific conclusion.

Conclusions reached via deductive reasoning cannot be incorrect if the premises are true. That’s because the conclusion doesn’t contain information that’s not in the premises. Unlike deductive reasoning, though, a conclusion reached via inductive reasoning goes beyond the information contained within the premises—it’s a generalization , and generalizations aren’t always accurate.

The best way to understand the difference between inductive and deductive reasoning is probably through examples.

Go Behind The Words!

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Examples of inductive and deductive reasoning

Examples of inductive reasoning.

Premise: All known fish species in this genus have yellow fins. Conclusion: Any newly discovered species in the genus is likely to have yellow fins.

Premises: This volcano has erupted about every 500 years for the last 1 million years. It last erupted 499 years ago. Conclusion: It will erupt again soon.

Examples of deductive reasoning

Premises: All plants with rainbow berries are poisonous. This plant has rainbow berries. Conclusion: This plant is poisonous.

Premises: I am lactose intolerant. Lactose intolerant people get sick when they consume dairy. This milkshake contains dairy. Conclusion: I will get sick if I drink this milkshake.

Reason your way to the best score by taking our quiz on "inductive" vs. "deductive" reasoning!

Science & Technology

Hobbies & Passions

Word Origins

Current Events

[ kahf-k uh - esk ]

Inductive Essays: Tips, Examples, and Topics

- Carla Johnson

- June 14, 2023

- How to Guides

Inductive essays are a common type of academic writing. To come to a conclusion, you have to look at the evidence and figure out what it all means. Inductive essays start with a set of observations or evidence and then move toward a conclusion. Deductive essays start with a thesis statement and then give evidence to support it. This type of essay is often used in the social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences.

The goal of an inductive essay is to look at the evidence and draw a conclusion from it. It requires carefully analyzing and interpreting the evidence and being able to draw logical conclusions from it. Instead of starting with a conclusion in mind and trying to prove it, the goal is to use the evidence to build a case for that conclusion.

You can’t say enough about how important it is to look at evidence before coming to a conclusion. In today’s world, where information is easy to find and often contradictory, it is important to be able to sort through the facts to come to a good decision. It is also important to be able to tell when the evidence isn’t complete or doesn’t prove anything, and to be able to admit when there is uncertainty.

In the sections that follow, we’ll talk about some tips for writing good inductive essays, show you some examples of good inductive essays, and give you some ideas for topics for your next inductive essay. By the end of this article, you’ll know more about how to write an inductive essay well.

What You'll Learn

Elements of an Inductive Essay

Most of the time, an inductive essay has three main parts: an intro, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

The introduction should explain what the topic is about and show the evidence that will be looked at in the essay . It should also have a thesis statement that sums up the conclusion that will be drawn from the evidence.

In the body paragraphs, you should show and explain the evidence. Each paragraph should focus on one piece of evidence and explain how it supports the thesis statement . The analysis should make sense and be well-supported, and there should be a clear link between the evidence and the conclusion.

In the conclusion, you should sum up the evidence and the conclusion you came to based on it. It should also put the conclusion in a bigger picture by explaining why it’s important and what it means for the topic at hand.

How to Choose a Topic for an Inductive Essay

It can be hard to choose a topic for an inductive essay, but there are a few things you can do that will help.

First, it’s important to look at the assignment prompt carefully. What’s the question you’re supposed to answer? What evidence do you have to back up your claim? To choose a topic that is both possible and interesting , you need to understand the prompt and the evidence you have.

Next, brainstorming can be a good way to come up with ideas. Try writing down all the ideas that come to mind when you think about the prompt. At this point, it doesn’t matter if the ideas are good or not. The goal is to come up with as many ideas as possible.

Once you have a list of possible topics , it’s important to pick one that you can handle and that you’re interested in. Think about how big the topic is and if you will have enough time to analyze the evidence in enough depth for the assignment . Also, think about your own passions and interests. If you choose a topic that really interests you, you are more likely to write a good essay .

Some potential topics for an inductive essay include:

– The impact of social media on mental health

– The effectiveness of alternative medicine for treating chronic pain

– The causes of income inequality in the United States

– The relationship between climate change and extreme weather events

– The effects of video game violence on children

By following these tips for choosing a topic and understanding the elements of an inductive essay, you can master the art of this type of academic writing and produce compelling and persuasive essays that draw on evidence to arrive at sound conclusions.

Inductive Essay Outline

An outline can help you to organize your thoughts and ensure that your essay is well-structured. An inductive essay outline typically includes the following sections:

– Introduction: The introduction should provide background information on the topic and present the evidence that will be analyzed in the essay . It should also include a thesis statement that summarizes the conclusion that will be drawn from the evidence.

– Body Paragraphs: The body paragraphs should present the evidence and analyze it in depth. Each paragraph should focus on a specific piece of evidence and explain how it supports the thesis statement . The analysis should be logical and well-supported, with clear connections made between the evidence and the conclusion.

– Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the evidence and the conclusion that was drawn from it. It should also provide a broader context for the conclusion, explaining why it matters and what implications it has for the topic at hand.

Inductive Essay Structure

The structure of an inductive essay is similar to that of other types of academic essays. It typically includes the following elements:

– Thesis statement: The thesis statement should summarize the conclusion that will be drawn from the evidence and provide a clear focus for the essay .

– Introduction: The introduction should provide background information on the topic and present the evidence that will be analyzed in the essay. It should also include a thesis statement that summarizes the conclusion that will be drawn from the evidence.

– Body Paragraphs: The body paragraphs should present the evidence and analyze it in depth. Each paragraph should focus on a specific piece of evidence and explain how it supports the thesis statement. The analysis should be logical and well-supported, with clear connections made between the evidence and the conclusion.

It is important to note that the body paragraphs can be organized in different ways depending on the nature of the evidence and the argument being made. For example, you may choose to organize the paragraphs by theme or chronologically. Regardless of the organization, each paragraph should be focused and well-supported with evidence.

By following this structure, you can ensure that your inductive essay is well-organized and persuasive, drawing on evidence to arrive at a sound conclusion. Remember to carefully analyze the evidence, and to draw logical connections between the evidence and the conclusion. With practice, you can master the art of inductive essays and become a skilled academic writer.

Inductive Essay Examples

Examples of successful inductive essays can provide a helpful model for your own writing. Here are some examples of inductive essay topics:

– Example 1: The Link Between Smoking and Lung Cancer: This essay could look at the studies and statistics that have been done on the link between smoking and lung cancer and come to a conclusion about how strong it is.

– Example 2: The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health: This essay could look at the studies and personal experiences that have been done on the effects of social media on mental health to come to a conclusion about the effects of social media on mental health.

– Example 3: The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture: This essay could look at the studies and expert opinions on the effects of climate change on agriculture to come to a conclusion about how it might affect food production..

– Example 4: The Benefits of a Plant-Based Diet: This essay could look at the available evidence about the benefits of a plant-based diet, using studies and dietary guidelines to come to a conclusion about the health benefits of this type of diet.

– Example 5: The Effects of Parenting Styles on Child Development: This essay could look at the studies and personal experiences that have been done on the effects of parenting styles on child development and come to a conclusion about the best way to raise a child.

Tips for Writing an Effective Inductive Essay

Here are some tips for writing acompelling and effective inductive essay:

1. Presenting evidence in a logical and organized way: It is important to present evidence in a clear and organized way that supports the thesis statement and the conclusion. Use topic sentences and transitions to make the connections between the evidence and the conclusion clear for the reader.

2. Considering alternative viewpoints: When analyzing evidence, it is important to consider alternative viewpoints and opinions. Acknowledge counterarguments and address them in your essay, demonstrating why your conclusion is more compelling.

3. Using strong and credible sources: Use credible sources such as peer-reviewed journal articles , statistics, and expert opinions to support your argument. Avoid relying on unreliable sources or anecdotal evidence.

4. Avoiding fallacies and biases: Be aware of logical fallacies and biases that can undermine the credibility of your argument. Avoid making assumptions or jumping to conclusions without sufficient evidence.

By following these tips, you can write an effective inductive essay that draws on evidence to arrive at a sound conclusion. Remember to carefully analyze the evidence, consider alternative viewpoints, and use credible sources to support your argument. With practice and dedication, you can master the art of inductive essays and become a skilled academic writer.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is an inductive essay.

An inductive essay is an academic writing that starts with a set of observations or evidence and then works towards a conclusion. The essay requires careful analysis and interpretation of evidence, and the ability to draw logical conclusions based on that evidence.

2. What are the elements of an inductive essay?

An inductive essay typically consists of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction provides background information and presents the thesis statement. The body paragraphs present the evidence and analyze it in depth. The conclusion summarizes the evidence and the conclusion drawn from it.

3. How do I choose a topic for an inductive essay?

To choose a topic for an inductive essay, carefully analyze the assignment prompt, brainstorm ideas, narrow down the topic, and select a topic that interests you.

4. What is the difference between an inductive essay and a deductive essay?

An inductive essay starts with evidence and works towards a conclusion, while a deductive essay starts with a thesis statement and provides arguments to support it.

5. How do I structure an inductive essay?

An inductive essay typically follows a structure that includes a thesis statement, introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

Inductive essays are an important type of academic writing that require careful analysis and interpretation of evidence to come to a conclusion. By using the advice in this article, you can become a good inductive essay writer. Remember to carefully look at the evidence, think about other points of view, use reliable sources, and stay away from logical errors and biases. In conclusion , learning how to write inductive essays is important for developing critical thinking skills and making arguments that are compelling and convincing. You can make a valuable contribution to your field of study and to society as a whole by looking at the facts and coming to logical conclusions. With practice and hard work , you can learn to write good inductive essays that will help you in school and in your career.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Yet to start your paper have a subject expert write for you now, test our paper writing service for less, already began delegate the remaining part to our professional writers.

📕 Studying HQ

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

- Academic Writing / Online Writing Instruction

Inductive vs. Deductive Writing

by Purdue Global Academic Success Center and Writing Center · Published February 25, 2015 · Updated February 24, 2015

Dr. Tamara Fudge, Kaplan University professor in the School of Business and IT

There are several ways to present information when writing, including those that employ inductive and deductive reasoning . The difference can be stated simply:

- Inductive reasoning presents facts and then wraps them up with a conclusion .

- Deductive reasoning presents a thesis statement and then provides supportive facts or examples.

Which should the writer use? It depends on content, the intended audience , and your overall purpose .

If you want your audience to discover new things with you , then inductive writing might make sense. Here is n example:

My dog Max wants to chase every non-human living creature he sees, whether it is the cats in the house or rabbits and squirrels in the backyard. Sources indicate that this is a behavior typical of Jack Russell terriers. While Max is a mixed breed dog, he is approximately the same size and has many of the typical markings of a Jack Russell. From these facts along with his behaviors, we surmise that Max is indeed at least part Jack Russell terrier.

Within that short paragraph, you learned about Max’s manners and a little about what he might look like, and then the concluding sentence connected these ideas together. This kind of writing often keeps the reader’s attention, as he or she must read all the pieces of the puzzle before they are connected.

Purposes for this kind of writing include creative writing and perhaps some persuasive essays, although much academic work is done in deductive form.

If your audience is not likely going to read the entire written piece, then deductive reasoning might make more sense, as the reader can look for what he or she wants by quickly scanning first sentences of each paragraph. Here is an example:

My backyard is in dire need of cleaning and new landscaping. The Kentucky bluegrass that was planted there five years ago has been all but replaced by Creeping Charlie, a particularly invasive weed. The stone steps leading to the house are in some disrepair, and there are some slats missing from the fence. Perennials were planted three years ago, but the moles and rabbits destroyed many of the bulbs, so we no longer have flowers in the spring.

The reader knows from the very first sentence that the backyard is a mess! This paragraph could have ended with a clarifying conclusion sentence; while it might be considered redundant to do so, the scientific community tends to work through deductive reasoning by providing (1) a premise or argument – which could also be called a thesis statement, (2) then evidence to support the premise, and (3) finally the conclusion.

Purposes for this kind of writing include business letters and project documents, where the client is more likely to skim the work for generalities or to hunt for only the parts that are important to him or her. Again, scientific writing tends to follow this format as well, and research papers greatly benefit from deductive writing.

Whether one method or another is chosen, there are some other important considerations. First, it is important that the facts/evidence be true. Perform research carefully and from appropriate sources; make sure ideas are cited properly. You might need to avoid absolute words such as “always,” “never,” and “only,” because they exclude any anomalies. Try not to write questions: the writer’s job is to provide answers instead. Lastly, avoid quotes in thesis statements or conclusions, because they are not your own words – and thus undermine your authority as the paper writer.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Tags: Critical thinking Reasoning

- Next story Winter Reading for Online Faculty

- Previous story Your Students are 13 Minutes Away From Avoiding Plagiarism

You may also like...

Brexit voters broke it and now regret it-part i: establishing the importance of teaching and learning in developing an educated, global electorate.

October 26, 2016

by Purdue Global Academic Success Center and Writing Center · Published October 26, 2016 · Last modified April 8, 2020

The Big Misconception about Writing to Learn

June 10, 2015

by Purdue Global Academic Success Center and Writing Center · Published June 10, 2015

Why Not Finally Answer “Why?”

April 29, 2015

by Purdue Global Academic Success Center and Writing Center · Published April 29, 2015 · Last modified April 28, 2015

11 Responses

- Pingbacks 2

thanks for this article because I can improve our reading skills

Thank you. The article very interesting and I can learn to improve our English skill in here.

Study is good for get science t

I want sudy feends

Helpful Thanks

Great article! This was helpful and provided great information.

Very helpful

very helpful . thank you

Very helpful.

[…] + Read More Here […]

[…] begin with alarming statistics and the urgency of action. However, articles often transition into inductive storytelling by featuring firsthand accounts of climate-related events or interviews with affected communities. […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Inductive VS Deductive Reasoning – The Meaning of Induction and Deduction, with Argument Examples

If you're conducting research on a topic, you'll use various strategies and methods to gather information and come to a conclusion.

Two of those methods are inductive and deductive reasoning.

So what's the difference between inductive and deductive reasoning, when should you use each method, and is one better than the other?

We'll answer those questions and give you some examples of both types of reasoning in this article.

What is Inductive Reasoning?

The method behind inductive reasoning.

When you're using inductive reasoning to conduct research, you're basing your conclusions off your observations. You gather information - from talking to people, reading old newspapers, observing people, animals, or objects in their natural habitat, and so on.

Inductive reasoning helps you take these observations and form them into a theory. So you're starting with some more specific information (what you've seen/heard) and you're using it to form a more general theory about the way things are.

What does the inductive reasoning process look like?

You can think of this process as a reverse funnel – starting with more specifics and getting broader as you reach your conclusions (theory).

Some people like to think of it as a "bottom up" approach (meaning you're starting at the bottom with the info and are going up to the top where the theory forms).

Here's an example of an inductive argument:

Observation (premise): My Welsh Corgis were incredibly stubborn and independent (specific observation of behavior). Observation (premise): My neighbor's Corgis are the same way (another specific observation of behavior). Theory: All Welsh Corgis are incredibly stubborn and independent (general statement about the behavior of Corgis).

As you can see, I'm basing my theory on my observations of the behavior of a number of Corgis. Since I only have a small amount of data, my conclusion or theory will be quite weak.

If I was able to observe the behavior of 1000 Corgis (omg that would be amazing), my conclusion would be stronger – but still not certain. Because what if 10 of them were extremely well-behaved and obedient? Or what if the 1001st Corgi was?

So, as you can see, I can make a general statement about Corgis being stubborn, but I can't say that ALL of them are.

What can you conclude with inductive reasoning?

As I just discussed, one of the main things to know about inductive reasoning is that any conclusions you make from inductive research will not be 100% certain or confirmed.

Let's talk about the language we use to describe inductive arguments and conclusions. You can have a strong argument (if your premise(s) are true, meaning your conclusion is probably true). And that argument becomes cogent if the conclusion ends up being true.

Still, even if the premises of your argument are true, and that means that your conclusion is probably true, or likely true, or true much of the time – it's not certain.

And – weirdly enough – your conclusion can still be false even if all your premises are true (my Corgis were stubborn, my neighbor's corgis were stubborn, perhaps a friend's Corgis and the Queen of England's Corgis were stubborn...but that doesn't guarantee that all Corgis are stubborn).

How to make your inductive arguments stronger

If you want to make sure your inductive arguments are as strong as possible, there are a couple things you can do.

First of all, make sure you have a large data set to work with. The larger your sample size, the stronger (and more certain/conclusive) your results will be. Again, thousands of Corgis are better than four (I mean, always, amiright?).

Second, make sure you're taking a random and representative sample of the population you're studying. So, for example, don't just study Corgi puppies (cute as they may be). Or show Corgis (theoretically they're better trained). You'd want to make sure you looked at Corgis from all walks of life and of all ages.

If you want to dig deeper into inductive reasoning, look into the three different types – generalization, analogy, and causal inference. You can also look into the two main methods of inductive reasoning, enumerative and eliminative. But those things are a bit out of the scope of this beginner's guide. :)

What is Deductive Reasoning?

The method behind deductive reasoning.

In order to use deductive reasoning, you have to have a theory to begin with. So inductive reasoning usually comes before deductive in your research process.

Once you have a theory, you'll want to test it to see if it's valid and your conclusions are sound. You do this by performing experiments and testing your theory, narrowing down your ideas as the results come in. You perform these tests until only valid conclusions remain.

What does the deductive reasoning process look like?

You can think of this as a proper funnel – you start with the broad open top end of the funnel and get more specific and narrower as you conduct your deductive research.

Some people like to think of this as a "top down" approach (meaning you're starting at the top with your theory, and are working your way down to the bottom/specifics). I think it helps to think of this as " reductive " reasoning – you're reducing your theories and hypotheses down into certain conclusions.

Here's an example of a deductive argument:

We'll use a classic example of deductive reasoning here – because I used to study Greek Archaeology, history, and language:

Theory: All men are mortal Premise: Socrates is a man Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal

As you can see here, we start off with a general theory – that all men are mortal. (This is assuming you don't believe in elves, fairies, and other beings...)

Then we make an observation (develop a premise) about a particular example of our data set (Socrates). That is, we say that he is a man, which we can establish as a fact.

Finally, because Socrates is a man, and based on our theory, we conclude that Socrates is therefore mortal (since all men are mortal, and he's a man).

You'll notice that deductive reasoning relies less on information that could be biased or uncertain. It uses facts to prove the theory you're trying to prove. If any of your facts lead to false premises, then the conclusion is invalid. And you start the process over.

What can you conclude with deductive reasoning?

Deductive reasoning gives you a certain and conclusive answer to your original question or theory. A deductive argument is only valid if the premises are true. And the arguments are sound when the conclusion, following those valid arguments, is true.

To me, this sounds a bit more like the scientific method. You have a theory, test that theory, and then confirm it with conclusive/valid results.

To boil it all down, in deductive reasoning:

"If all premises are true, the terms are clear , and the rules of deductive logic are followed, then the conclusion reached is necessarily true ." ( Source )

So Does Sherlock Holmes Use Inductive or Deductive Reasoning?

Sherlock Holmes is famous for using his deductive reasoning to solve crimes. But really, he mostly uses inductive reasoning. Now that we've gone through what inductive and deductive reasoning are, we can see why this is the case.

Let's say Sherlock Holmes is called in to work a case where a woman was found dead in her bed, under the covers, and appeared to be sleeping peacefully. There are no footprints in the carpet, no obvious forced entry, and no immediately apparent signs of struggle, injury, and so on.

Sherlock observes all this as he looks in, and then enters the room. He walks around the crime scene making observations and taking notes. He might talk to anyone who lives with her, her neighbors, or others who might have information that could help him out.

Then, once he has all the info he needs, he'll come to a conclusion about how the woman died.

That pretty clearly sounds like an inductive reasoning process to me.

Now you might say - what if Sherlock found the "smoking gun" so to speak? Perhaps this makes his arguments and process seem more deductive.

But still, remember how he gets to his conclusions: starting with observations and evidence, processing that evidence to come up with a hypothesis, and then forming a theory (however strong/true-seeming) about what happened.

How to Use Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Together

As you might be able to tell, researchers rarely just use one of these methods in isolation. So it's not that deductive reasoning is better than inductive reasoning, or vice versa – they work best when used in tandem.

Often times, research will begin inductively. The researcher will make their observations, take notes, and come up with a theory that they want to test.

Then, they'll come up with ways to definitively test that theory. They'll perform their tests, sort through the results, and deductively come to a sure conclusion.

So if you ever hear someone say "I deduce that x happened", they better make sure they're working from facts and not just observations. :)

TL;DR: Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning – What are the Main Differences?

Inductive reasoning:.

- Based on observations, conversations, stuff you've read

- Starts with information/evidence and works towards a broader theory

- Arguments can be strong and cogent, but never valid or sound (that is, certain)

- Premises can all be true, but conclusion doesn't have to be true

Deductive reasoning:

- Based on testing a theory, narrowing down the results, and ending with a conclusion

- Starts with a broader theory and works towards certain conclusion

- Arguments can be valid/invalid or sound/unsound, because they're based on facts

- If premises are true, conclusion has to be true

And here's a cool and helpful chart if you're a visual learner:

That's about it!

Now, if you need to conduct some research, you should have a better idea of where to start – and where to go from there.

Just remember that induction is all about observing, hypothesizing, and forming a theory. Deducing is all about taking that (or any) theory, boiling it down, and testing until a certain conclusion(s) is all that remains.

Happy reasoning!

I love editing articles and working with contributors. I also love the outdoors and good food.

If you read this far, thank the author to show them you care. Say Thanks

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp's open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

Inductive and Deductive Assignment (McMahon)

The next writing assignment we will be concentrating on will be the construction of persuasive passages using induction, deduction, and expressive language or analogy. These passages should be used to further strengthen and develop your Pro/Con and/or your Rogerian essays.

1. Inductive reasoning is the process of reasoning from specifics to the general. We draw general conclusions based on discrete, specific everyday experiences. Because both writers and readers share this reasoning process, induction can be a highly effective strategy for persuasion. A truly persuasive and effective inductive argument proceeds through an accumulation of many specifics. Within your own essays you should use support from outside sources, personal experience, and specific examples to fully develop your inductive passages. Also, keep in mind that conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning are always only probable. To use induction effectively, a writer must demonstrate that the specifics are compelling and thus justify the conclusion but never claim that the conclusion is guaranteed in all situations. In addition, a writer must keep in mind who his/her audience is and what specifics or evidence will persuade the audience to accept the conclusion. Finally, a writer who is reasoning inductively must be cautious of hasty generalizations in which the specifics are inadequate to justify the conclusions.

2. Deductive reasoning is the process of reasoning from general statements agreed to be true to a certain and logical conclusion. Again, like inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning is a familiar strategy we use in our everyday lives and is a potentially effective persuasive strategy. However, unlike inductive reasoning when the conclusion may be justified but is always only probable, the conclusion reached deductively must be logically certain. Most deductive arguments begin with a general statement that has already been "proven" inductively and is now accepted by most people as true. Today, most deductive general statements involve commonly held values or established scientific fact. A writer who uses deduction to frame an argument must be absolutely certain that the general statement is accepted as true and then must demonstrate the relationship between this general statement and the specific claim, thus proving beyond a doubt the conclusion. An effective deductive argument is one in which your audience accepts the general statement and is then logically compelled by the development of the argument to accept your conclusion.

3. An analogy helps a writer further develop and support an idea he/she is trying to convey to a reader. In an analogy a comparison is drawn between the principle idea and something else a reader is familiar with. Thus, the comparison clarifies the principle idea. Analogies within persuasive writing appeal to either a reader's value system or to a reader's reason and logic. Asking a reader to consider an idea, issue, or problem in the context of something else can both clarify the idea and persuade the reader to accept our interpretation of the idea. Please note: analogies only work when the subjects you are comparing have some similarities. If the things you compare are too dissimilar, your readers will dismiss the analogy and fail to be persuaded of your idea.

- Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Two Ways of Understanding

We have two basic approaches for how we come to believe something is true.

The first way is that we are exposed to several different examples of a situation, and from those examples, we conclude a general truth. For instance, you visit your local grocery store daily to pick up necessary items. You notice that on Friday, two weeks ago, all the clerks in the store were wearing football jerseys. Again, last Friday, the clerks wore their football jerseys. Today, also a Friday, they’re wearing them again. From just these observations, you can conclude that on all Fridays, these supermarket employees will wear football jerseys to support their local team.

This type of pattern recognition, leading to a conclusion, is known as inductive reasoning .

Knowledge can also move the opposite direction. Say that you read in the news about a tradition in a local grocery store, where employees wore football jerseys on Fridays to support the home team. This time, you’re starting from the overall rule, and you would expect individual evidence to support this rule. Each time you visited the store on a Friday, you would expect the employees to wear jerseys.

Such a case, of starting with the overall statement and then identifying examples that support it, is known as deductive reasoning .

The Power of Inductive Reasoning

You have been employing inductive reasoning for a very long time. Inductive reasoning is based on your ability to recognize meaningful patterns and connections. By taking into account both examples and your understanding of how the world works, induction allows you to conclude that something is likely to be true. By using induction, you move from specific data to a generalization that tries to capture what the data “mean.”

Imagine that you ate a dish of strawberries and soon afterward your lips swelled. Now imagine that a few weeks later you ate strawberries and soon afterwards your lips again became swollen. The following month, you ate yet another dish of strawberries, and you had the same reaction as formerly. You are aware that swollen lips can be a sign of an allergy to strawberries. Using induction, you conclude that, more likely than not, you are allergic to strawberries.

Data : After I ate strawberries, my lips swelled (1st time).

Data : After I ate strawberries, my lips swelled (2nd time).

Data : After I ate strawberries, my lips swelled (3rd time).

Additional Information : Swollen lips after eating strawberries may be a sign of an allergy.

Conclusion : Likely I am allergic to strawberries.

The results of inductive thinking can be skewed if relevant data are overlooked. In the previous example, inductive reasoning was used to conclude that I am likely allergic to strawberries after suffering multiple instances of my lips swelling. Would I be as confident in my conclusion if I were eating strawberry shortcake on each of those occasions? Is it reasonable to assume that the allergic reaction might be due to another ingredient besides strawberries?

This example illustrates that inductive reasoning must be used with care. When evaluating an inductive argument, consider

- the amount of the data,

- the quality of the data,

- the existence of additional data,

- the relevance of necessary additional information, and

- the existence of additional possible explanations.

Inductive Reasoning Put to Work

A synopsis of the features, benefits, and drawbacks of inductive reasoning can be found in this video.

The Power of Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning is built on two statements whose logical relationship should lead to a third statement that is an unquestionably correct conclusion, as in the following example.

All raccoons are omnivores. This animal is a raccoon. This animal is an omnivore.

If the first statement is true (All raccoons are omnivores) and the second statement is true (This animal is a raccoon), then the conclusion (This animal is an omnivore) is unavoidable. If a group must have a certain quality, and an individual is a member of that group, then the individual must have that quality.

Going back to the example from the opening of this page, we could frame it this way:

Grocery store employees wear football jerseys on Fridays. Today is Friday. Grocery store employees will be wearing football jerseys today.

Unlike inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning allows for certainty as long as certain rules are followed.

Evaluating the Truth of a Premise

A formal argument may be set up so that, on its face, it looks logical. However, no matter how well-constructed the argument is, the additional information required must be true. Otherwise any inferences based on that additional information will be invalid.

Inductive reasoning can often be hidden inside a deductive argument. That is, a generalization reached through inductive reasoning can be turned around and used as a starting “truth” a deductive argument. For instance,

Most Labrador retrievers are friendly. Kimber is a Labrador retriever. Therefore, Kimber is friendly.

In this case we cannot know for certain that Kimber is a friendly Labrador retriever. The structure of the argument may look logical, but it is based on observations and generalizations rather than indisputable facts.

Methods to Evaluate the Truth of a Premise

One way to test the accuracy of a premise is to apply the same questions asked of inductive arguments. As a recap, you should consider

- the relevance of the additional data, and

- the existence of additional possible explanations.

Determine whether the starting claim is based upon a sample that is both representative and sufficiently large, and ask yourself whether all relevant factors have been taken into account in the analysis of data that leads to a generalization.

Another way to evaluate a premise is to determine whether its source is credible.

- Are the authors identified?

- What is their background?

- Was the claim something you found on an undocumented website?

- Did you find it in a popular publication or a scholarly one?

- How complete, how recent, and how relevant were the studies or statistics discussed in the source?

Overview and Recap

A synopsis of the features, benefits, and drawbacks of deductive reasoning can be found in this video.

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Inductive Reasoning. Authored by : Chuck Creager Jr.. Located at : https://youtu.be/wzEOwleZNnA . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Deductive Reasoning. Authored by : Chuck Creager Jr.. Located at : https://youtu.be/oBnKgxcdSyM . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- The Logical Structure of Arguments. Provided by : Radford University. Located at : http://lcubbison.pressbooks.com/chapter/core-201-analyzing-arguments/ . Project : Core Curriculum Handbook. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Table of Contents

Instructor Resources (available upon sign-in)

- Overview of Instructor Resources

- Quiz Survey

Reading: Types of Reading Material

- Introduction to Reading

- Outcome: Types of Reading Material

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 1

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 2

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 3

- Characteristics of Texts, Conclusion

- Self Check: Types of Writing

Reading: Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Reading Strategies

- The Rhetorical Situation

- Academic Reading Strategies

- Self Check: Reading Strategies

Reading: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Online Reading Comprehension

- How to Read Effectively in Math

- How to Read Effectively in the Social Sciences

- How to Read Effectively in the Sciences

- 5 Step Approach for Reading Charts and Graphs

- Self Check: Specialized Reading Strategies

Reading: Vocabulary

- Outcome: Vocabulary

- Strategies to Improve Your Vocabulary

- Using Context Clues

- The Relationship Between Reading and Vocabulary

- Self Check: Vocabulary

Reading: Thesis

- Outcome: Thesis

- Locating and Evaluating Thesis Statements

- The Organizational Statement

- Self Check: Thesis

Reading: Supporting Claims

- Outcome: Supporting Claims

- Types of Support

- Supporting Claims

- Self Check: Supporting Claims

Reading: Logic and Structure

- Outcome: Logic and Structure

- Rhetorical Modes

- Diagramming and Evaluating Arguments

- Logical Fallacies

- Evaluating Appeals to Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

- Self Check: Logic and Structure

Reading: Summary Skills

- Outcome: Summary Skills

- How to Annotate

- Paraphrasing

- Quote Bombs

- Summary Writing

- Self Check: Summary Skills

- Conclusion to Reading

Writing Process: Topic Selection

- Introduction to Writing Process

- Outcome: Topic Selection

- Starting a Paper

- Choosing and Developing Topics

- Back to the Future of Topics

- Developing Your Topic

- Self Check: Topic Selection

Writing Process: Prewriting

- Outcome: Prewriting

- Prewriting Strategies for Diverse Learners

- Rhetorical Context

- Working Thesis Statements

- Self Check: Prewriting

Writing Process: Finding Evidence

- Outcome: Finding Evidence

- Using Personal Examples

- Performing Background Research

- Listening to Sources, Talking to Sources

- Self Check: Finding Evidence

Writing Process: Organizing

- Outcome: Organizing

- Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Theme

- Introduction to Argument

- The Three-Story Thesis

- Organically Structured Arguments

- Logic and Structure

- The Perfect Paragraph

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Self Check: Organizing

Writing Process: Drafting

- Outcome: Drafting

- From Outlining to Drafting

- Flash Drafts

- Self Check: Drafting

Writing Process: Revising

- Outcome: Revising

- Seeking Input from Others

- Responding to Input from Others

- The Art of Re-Seeing

- Higher Order Concerns

- Self Check: Revising

Writing Process: Proofreading

- Outcome: Proofreading

- Lower Order Concerns

- Proofreading Advice

- "Correctness" in Writing

- The Importance of Spelling

- Punctuation Concerns

- Self Check: Proofreading

- Conclusion to Writing Process

Research Process: Finding Sources

- Introduction to Research Process

- Outcome: Finding Sources

- The Research Process

- Finding Sources

- What are Scholarly Articles?

- Finding Scholarly Articles and Using Databases

- Database Searching

- Advanced Search Strategies

- Preliminary Research Strategies

- Reading and Using Scholarly Sources

- Self Check: Finding Sources

Research Process: Source Analysis

- Outcome: Source Analysis

- Evaluating Sources

- CRAAP Analysis

- Evaluating Websites

- Synthesizing Sources

- Self Check: Source Analysis

Research Process: Writing Ethically

- Outcome: Writing Ethically

- Academic Integrity

- Defining Plagiarism

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Using Sources in Your Writing

- Self Check: Writing Ethically

Research Process: MLA Documentation

- Introduction to MLA Documentation

- Outcome: MLA Documentation

- MLA Document Formatting

- MLA Works Cited

- Creating MLA Citations

- MLA In-Text Citations

- Self Check: MLA Documentation

- Conclusion to Research Process

Grammar: Nouns and Pronouns

- Introduction to Grammar

- Outcome: Nouns and Pronouns

- Pronoun Cases and Types

- Pronoun Antecedents

- Try It: Nouns and Pronouns

- Self Check: Nouns and Pronouns

Grammar: Verbs

- Outcome: Verbs

- Verb Tenses and Agreement

- Non-Finite Verbs

- Complex Verb Tenses

- Try It: Verbs

- Self Check: Verbs

Grammar: Other Parts of Speech

- Outcome: Other Parts of Speech

- Comparing Adjectives and Adverbs

- Adjectives and Adverbs

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

- Try It: Other Parts of Speech

- Self Check: Other Parts of Speech

Grammar: Punctuation

- Outcome: Punctuation

- End Punctuation

- Hyphens and Dashes

- Apostrophes and Quotation Marks

- Brackets, Parentheses, and Ellipses

- Semicolons and Colons

- Try It: Punctuation

- Self Check: Punctuation

Grammar: Sentence Structure

- Outcome: Sentence Structure

- Parts of a Sentence

- Common Sentence Structures

- Run-on Sentences

- Sentence Fragments

- Parallel Structure

- Try It: Sentence Structure

- Self Check: Sentence Structure

Grammar: Voice

- Outcome: Voice

- Active and Passive Voice

- Using the Passive Voice

- Conclusion to Grammar

- Try It: Voice

- Self Check: Voice

Success Skills

- Introduction to Success Skills

- Habits for Success

- Critical Thinking

- Time Management

- Writing in College

- Computer-Based Writing

- Conclusion to Success Skills

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Inductive vs Deductive Research Approach (with Examples)

Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning | Difference & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 10 October 2022.

The main difference between inductive and deductive reasoning is that inductive reasoning aims at developing a theory while deductive reasoning aims at testing an existing theory .

Inductive reasoning moves from specific observations to broad generalisations , and deductive reasoning the other way around.

Both approaches are used in various types of research , and it’s not uncommon to combine them in one large study.

Table of contents

Inductive research approach, deductive research approach, combining inductive and deductive research, frequently asked questions about inductive vs deductive reasoning.

When there is little to no existing literature on a topic, it is common to perform inductive research because there is no theory to test. The inductive approach consists of three stages:

- A low-cost airline flight is delayed

- Dogs A and B have fleas

- Elephants depend on water to exist

- Another 20 flights from low-cost airlines are delayed

- All observed dogs have fleas

- All observed animals depend on water to exist

- Low-cost airlines always have delays

- All dogs have fleas

- All biological life depends on water to exist

Limitations of an inductive approach

A conclusion drawn on the basis of an inductive method can never be proven, but it can be invalidated.

Example You observe 1,000 flights from low-cost airlines. All of them experience a delay, which is in line with your theory. However, you can never prove that flight 1,001 will also be delayed. Still, the larger your dataset, the more reliable the conclusion.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

When conducting deductive research , you always start with a theory (the result of inductive research). Reasoning deductively means testing these theories. If there is no theory yet, you cannot conduct deductive research.

The deductive research approach consists of four stages:

- If passengers fly with a low-cost airline, then they will always experience delays

- All pet dogs in my apartment building have fleas

- All land mammals depend on water to exist

- Collect flight data of low-cost airlines

- Test all dogs in the building for fleas

- Study all land mammal species to see if they depend on water

- 5 out of 100 flights of low-cost airlines are not delayed

- 10 out of 20 dogs didn’t have fleas

- All land mammal species depend on water

- 5 out of 100 flights of low-cost airlines are not delayed = reject hypothesis

- 10 out of 20 dogs didn’t have fleas = reject hypothesis

- All land mammal species depend on water = support hypothesis

Limitations of a deductive approach

The conclusions of deductive reasoning can only be true if all the premises set in the inductive study are true and the terms are clear.

- All dogs have fleas (premise)

- Benno is a dog (premise)

- Benno has fleas (conclusion)

Many scientists conducting a larger research project begin with an inductive study (developing a theory). The inductive study is followed up with deductive research to confirm or invalidate the conclusion.

In the examples above, the conclusion (theory) of the inductive study is also used as a starting point for the deductive study.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is a method of drawing conclusions by going from the specific to the general. It’s usually contrasted with deductive reasoning, where you proceed from general information to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is also called inductive logic or bottom-up reasoning.

Deductive reasoning is a logical approach where you progress from general ideas to specific conclusions. It’s often contrasted with inductive reasoning , where you start with specific observations and form general conclusions.

Deductive reasoning is also called deductive logic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2022, October 10). Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning | Difference & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/inductive-vs-deductive-reasoning/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, inductive reasoning | types, examples, explanation, what is deductive reasoning | explanation & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

Deductive, Inductive, and Abductive Reasoning (with Examples)

Understanding different types of arguments is an important skill for philosophy as it enables us to assess the strength of the conclusions drawn. In this blog post, we’ll explore the characteristics of three different types of argument and look at some examples:

- Deductive arguments

- Inductive arguments

- Abductive arguments

Deductive Arguments: The Conclusion is Certainly True

Deductive arguments operate on the principle of logical necessity , aiming to provide conclusions that follow necessarily from the premises.

These arguments seek to establish the truth of specific claims based on the truth of general principles or premises. Deductive reasoning allows for definitive and conclusive outcomes if the premises are true.

In other words, deductive arguments are logically watertight: If the premises are true, it’s logically impossible for the conclusion to be false.

General Format of a Deductive Argument:

- Premise 1: General Principle A is true.

- Premise 2: General Principle B is true.

- Premise 3: General Principle C is true.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Specific Claim X is true.

- Premise 1: All dogs are mammals.

- Premise 2: Rex is a dog.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Rex is a mammal.

In this deductive argument, the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises. If we accept the truth of the general principle that all dogs are mammals (1) and the premise that Rex is a dog (2), we are logically compelled to accept the conclusion that Rex is a mammal (3).

Other examples of deductive argument formats include modus ponens and modus tollens .

Note: A deductively valid argument means the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises and so, if the premises of the argument are true, the conclusion must also be true. However, the premises may be false , in which case the conclusion may be false too. For example:

- Premise 1: If today is Monday, the moon is made of green cheese.

- Premise 2: Today is Monday.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the moon is made of green cheese.

This argument is still deductively valid – the conclusion does follow necessarily from the premises – but the conclusion is false because one or more of the premises are false . For more detail on valid reasoning (including the difference between a valid and sound argument) see this post .

Inductive Arguments: The Conclusion is Probably True

Inductive arguments involve reasoning from specific instances or observations to general conclusions or generalisations.

They aim to make general claims based on limited evidence, seeking to establish patterns, trends, or probabilities. While inductive arguments do not guarantee absolute certainty, they offer insights and probabilistic reasoning.

In other words, inductive arguments are not logically watertight – but they nevertheless provide support for the conclusion .

General Format of an Inductive Argument:

- Premise 1: Observation A is true.

- Premise 2: Observation B is true.

- Premise 3: Observation C is true.

- Conclusion: Therefore, it is likely that Generalisation X is true.

- Premise 1: Every bird I have observed can fly.

- Premise 2: The next bird I encounter will likely be able to fly.

- Premise 3: The bird species documented so far exhibit the ability to fly.

- Conclusion: Therefore, it is probable that all birds can fly.

This example illustrates an inductive argument where the conclusion is based on observed instances and generalises the ability of flight to all birds. While the conclusion is likely to be true, it is possible to encounter a bird species that cannot fly (e.g. an ostrich or a penguin), which weakens the argument’s strength.

Another type of inductive argument is an argument from analogy , where because two things are similar in one way they are likely to be similar in another way. For example, if your friend likes the same music as you, this may suggest they will like the same art as you.

Abductive Arguments: The Conclusion is the Best Explanation

Abductive arguments focus on finding the best or most plausible explanation for a given observation or phenomenon.

They involve reasoning from evidence to a hypothesis or explanation that provides the most likely account of the observed facts. An explanation may be considered more likely or plausible because it fits more neatly with the observed data, for example, or because it is the simplest explanation with the fewest assumptions (a principle known as Ockham’s Razor ).

Like inductive arguments, abductive arguments are not logically watertight. Although a hypothesis may seem to be the best explanation, other explanations are still logically possible.

General Format of an Abductive Argument:

- Observation: There is a certain observation or phenomenon.

- Evidence: Supporting evidence related to the observation.

- Hypothesis: A proposed explanation or claim that best accounts for the evidence.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Claim X is the most plausible explanation.

- Observation: The grass in the garden is wet.

- Evidence: There are water droplets on the leaves, and the ground is damp.

- Hypothesis: It rained last night.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the wet grass is most likely due to rain.

In this abductive argument, the wet grass and the presence of water droplets on the leaves and damp ground are the observed evidence. The hypothesis that it rained provides the best explanation for the observed evidence. However, other explanations, such as sprinklers or a hose, are also possible.

Applied to A Level Philosophy

There are various examples of deductive arguments, inductive arguments, and abductive arguments in A level philosophy .

Examples of deductive arguments in A level philosophy:

- The logical problem of evil

- Ontological arguments (e.g. Anselm’s or Malcolm’s )

- Descartes’ trademark argument

Examples of inductive arguments in A level philosophy:

- The evidential problem of evil

- Hume’s teleological argument

- Mill’s response to the problem of other minds

Examples of abductive arguments in A level philosophy:

- Russell’s argument that the external world is the best hypothesis

- Swinburne’s teleological argument

Identifying whether an argument is deductive, inductive, or abductive is a great way to demonstrate detailed and precise knowledge of philosophy and pick up those AO1 marks .

Further, knowing the difference between these types of arguments can also be useful to help evaluate ( AO2 ) the strengths and weaknesses of the various arguments you consider in the 25 mark essay questions.

- Straightforward explanations of syllabus topics for all 4 modules

- Bullet point summaries at the end of each module

- Exam blueprint for each question type (with example answers)

- Essay 25 mark essay plans for every major topic

- Glossary of key terms

Skip to Content

Massey University

- Search OWLL

- Handouts (Printable)

- Pre-reading Service

- StudyUp Recordings

- StudyUp Postgraduate

- Academic writing

- Intro to academic writing

- What is academic writing?

- Writing objectively

- Writing concisely

- 1st vs. 3rd person

- Inclusive language

- Te Reo Māori

- Assignment planning

- Assignment planning calculator

- Interpreting the assignment question

- Command words

- Organising points

- Researching

- Identifying academic sources

- Evaluating source quality

- Editing & proofreading

- Apostrophes

- Other punctuation

- Active voice

- American vs. British spelling

- Conditionals

- Prepositions

- Pronoun Reference

- Sentence fragments

- Sentence Structure

- Subject-verb agreement

- Formatting and layout

- Word limits and assignment length

- Commonly confused words

- How assignments are marked

- Marking guides

- Getting an A

- Levels of assessment

- Using feedback

- Professional emails

- Forum posts

- Forum netiquette guidelines

- Sharing personal information

- Writing about personal experiences

- Assignment types

- What is an essay?

- Essay planning and structure

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Body paragraphs

- Essay revision

- Essay writing resources

- What is a report?

- Report structure

- Analysing issues for a report

- Business report

- What is a business report?

- Business report structure

Inductive vs. deductive reports

- Other kinds of business communication

- Business report format and layout

- What is a lab report?

- Lab report structure

- Science lab report writing resources

- Psychology lab report writing resources

- Lab report body paragraphs

- Literature review

- What is a literature review?

- Writing a literature review

- Literature review structure

- Literature review writing resources

- Research proposal

- Writing a research proposal

- Research proposal structure

- Other types

- Article critique

- Book review

- Annotated bibliography

- Reflective writing

- Oral presentation

- Thesis / dissertation

- Article / conference paper

- Shorter responses

- PhD confirmation report

- Computer skills

- Microsoft Word

- Basic formatting

- Images, tables, & figures

- Long documents

- Microsoft Excel

- Basic spreadsheets

- Navigating & printing spreadsheets

- Charts / graphs & formulas

- Microsoft PowerPoint

- Basic skills

- Advanced skills

- Distance study

- Getting started

- How to study

- Online study techniques

- Distance support

- Reading & writing

- Reading strategies

- Writing strategies

- Grammar resources

- Listening & speaking

- Listening strategies

- Speaking strategies

- Maths & statistics

- Trigonometry

- Finance formulas

- Postgraduate study

- Intro to postgrad study

- Planning postgrad study

- Postgrad resources

- Postgrad assignment types

- Referencing

- Intro to referencing

- What is referencing?

- Why reference?

- Common knowledge

- Referencing styles

- What type of source is this?

- Reference list vs. bibliography

- Referencing software

- Quoting & paraphrasing

- Paraphrasing & summarising

- Paraphrasing techniques

- APA Interactive

- In-text citation

- Reference list

- Online material

- Other material

- Headings in APA

- Tables and Figures

- Referencing elements

- 5th vs. 6th edition

- 6th vs. 7th edition

- APA quick guides

- Chicago style

- Chicago Interactive

- About notes system

- Notes referencing elements

- Quoting and paraphrasing

- Author-date system

- MLA Interactive

- Abbreviations

- List of works cited

- Captions for images

- 8th vs 9th edition

- Oxford style

- Other styles

- Harvard style

- Vancouver style

- Legal citations

- Visual material

- Sample assignments

- Sample essay 1

- Sample essay 2

- Sample annotated bibliography

- Sample book review

- Study skills

- Time management

- Intro to time management

- Procrastination & perfectionism

- Goals & motivation

- Time management for internal students

- Time management for distance students

- Memory skills

- Principles of good memory

- Memory strategies

- Note-taking

- Note-taking methods

- Note-taking in lectures

- Note-taking while reading

- Digital note-taking

- Reading styles

- In-depth reading

- Reading comprehension

- Reading academic material

- Reading a journal article

- Reading an academic book

- Critical thinking

- What is critical thinking?

- Constructing an argument

- Critical reading

- Logical fallacies

- Tests & exams

- Exam & test study

- Planning exam study

- Gathering & sorting information

- Reviewing past exams

- Phases of revision

- Last-minute study strategies

- Question types

- Short answer

- Multi-choice

- Problem / computational

- Case-study / scenario

- Open book exam

- Open web exam or test

- Take home test

- In the exam

- Online exam

- Physical exam

The order of the report sections will depend on whether you are required to write an inductive or deductive report. Your assignment question should make this clear.

Inductive report

An inductive report involves moving from the specific issues, as outlined in the discussion, to the more general, summarised information, as displayed in the conclusions and recommendations:

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

Such reports are ideal for an audience who has the time to read the report from cover to cover, and also in instances where the findings may be somewhat controversial, hence, the need to demonstrate your reasoning and evidence, as laid out in the discussion, for the recommendations decided upon.

Deductive report

In contrast, in a deductive report you move from the general to the specific:

This type of order is effective when faced with an audience who does not have time to read the whole document, but can access the conclusions and recommendations. Consequently, such an order is also appropriate for reports which are not contentious or unexpected in their decision outcomes and recommendations.

Page authorised by Director - Centre for Learner Success Last updated on 25 October, 2012

- Academic Q+A

Have a study or assignment writing question? Ask an expert at Academic Q+A

Live online workshops

- StudyUp (undergraduate)

- Campus workshops

- Albany (undergraduate)

- Albany (postgraduate)

- Albany (distance)

- Manawatu (undergraduate)

- Manawatu (postgraduate)

Upcoming events

- All upcoming events

- Academic writing and learning support

- 0800 MASSEY | (+64 6 350 5701)

- [email protected]

- Online form

- Data analytics and AI

inductive argument

- Rahul Awati

What is an inductive argument?

An inductive argument is an assertion that uses specific premises or observations to make a broader generalization. Inductive arguments, by their nature, possess some degree of uncertainty. They are used to show the likelihood that a conclusion drawn from known premises is true.

Logic plays a big role in inductive arguments. In these arguments, the conclusion is supported by information that is known to be true or could be true in the future. Another way of saying this is that the truth of the premises supports the truth of the conclusion. The goal is to arrive at the most likely conclusion or the strongest possible explanation , given a set of circumstances and observations.

Inductive arguments -- also known as reasoning by induction -- are assessed as strong or weak, rather than as valid or invalid. In a strong inductive argument, if the premises are true, it would be highly unlikely that the conclusion would be false. A strong inductive conclusion contains reliable beliefs that are backed by strong evidence (even though there is no guarantee that the beliefs are indisputable). But if an inductive argument is weak, the logic between the premises and the conclusion would be incorrect, indicating weak beliefs and a possible unsound conclusion.

Inductive arguments vs. deductive arguments

Both inductive and deductive arguments are based on logic, facts and evidence. Where they differ is that an inductive argument is a type of bottom-up logic because it aims to widen specific premises into a broader generalization. In contrast, a deductive argument is a top-down argument that produces an irrefutable conclusion (as long as its premises are true).

When making an inductive argument, the arguer uses logic to establish a conclusion that is most likely to be valid, based on the given facts. But in a deductive argument, the arguer's goal is to provide a conclusion that guarantees the truth . Thus, the conclusion of a deductive argument is either true or false, provided that its premises are true. It cannot be partly valid or partly invalid, so there is no possibility of doubt. So, if the premises are known to be true, it's impossible for the conclusion of a deductive argument to be false.

When the premises guarantee the conclusion, the deductive argument is said to be deductively valid or sound. In contrast, the conclusion of an inductive argument is evaluated using terms like strong or most likely .

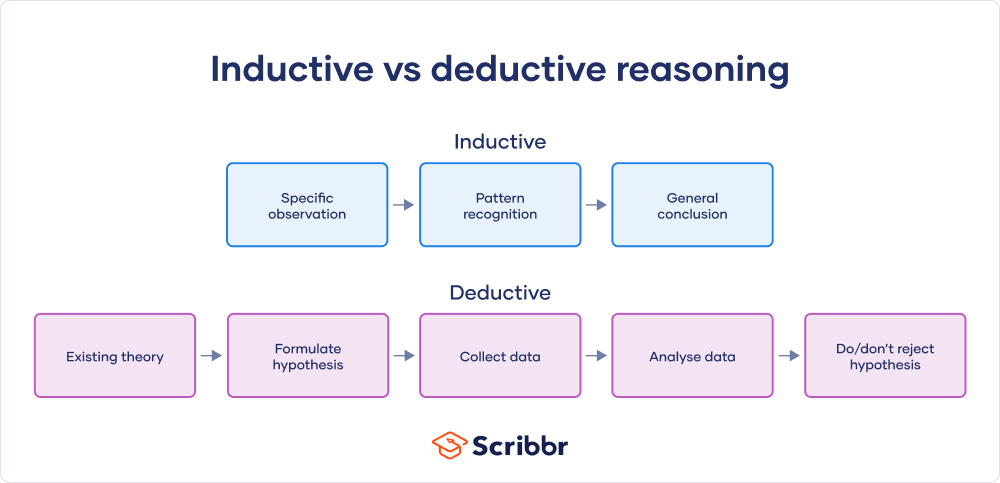

Inductive arguments with examples

The following example illustrates how an inductive argument uses specific facts to make a broader conclusion:

- Premise: All the tigers I saw on my safari trip to South Africa were orange.

- Conclusion: Therefore, all tigers are orange.

This is an example of a weak inductive argument because even though the premise is true (the observer saw only orange tigers on their trip), the conclusion cannot be true. This is because white tigers also exist, even though the observer didn't see them.

It is possible to strengthen this inductive argument and its conclusion:

- Conclusion: Hence, most tigers are probably orange.

Although the conclusion is not 100% true (white tigers still do exist), it is much stronger than the previous argument due to the words most and probably .

Applications of inductive reasoning

Almost everyone uses inductive reasoning every day to make sense of the world and to communicate their opinions and conclusions to others. Inductive arguments are also the foundation of scientific observations and research experiments. Scientists and researchers gather data, create hypotheses based on that data and then test their theories to prove or disprove those hypotheses.

Inductive arguments are also used frequently and very effectively in academia and in the practice of law. In fact, lawyers almost always use inductive arguments and provide evidence that seems irrefutable to support those arguments. Their reasoning is aimed at establishing a logical relationship between known facts. They are able to draw a strong conclusion and support it with the available evidence.

Depending on the strength of the lawyers' arguments and the validity of the evidence they present, the listener (such as the judge or jury) will assess which argument is sound and which one is unsound. These factors determine whether the defense or prosecution will win the case.

Types of inductive reasoning

There are many types of inductive arguments, such as the following:

Generalized reasoning

A generalized inductive argument uses premises about a sample set to draw general conclusions about a larger population. The tiger example from the earlier section is an example of a generalized inductive argument.

- Premise: The right-handed musicians I have seen play right-handed guitars.

- Conclusion: All right-handed musicians probably play right-handed guitars.

Statistical generalization

In this type of argument, statistics based on a large (and usually random) sample set are used to support conclusions. Since the statistics are quantifiable and not vague or unsupported, such generalizations usually strengthen the conclusion.

- Premise: Worldwide, about 2% of people are born with red hair.