Young people are key to a nicotine-free future: five steps to stop them smoking

Research Officer, Research on the Economics of Excisable Products,, University of Cape Town

Professor at the School of Economics and Principal Investigator of the Economics of Tobacco Control Project, University of Cape Town

Disclosure statement

Sam Filby works for the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) at the University of Cape Town.

Corné van Walbeek is the Director of the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) at the University of Cape Town. The unit receives funding from a variety of health foundations, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the African Capacity Research Foundation, Cancer Research UK and the International Development Research Centre. The unit has never received funding from the tobacco industry, or any of its front groups.

University of Cape Town provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Tobacco use kills more than 8 million people each year. Most adult smokers start smoking before the age of 20 . This implies that if one can get through adolescence without smoking , the likelihood of being a smoker in adulthood is greatly reduced.

Preventing young people from becoming addicted to tobacco and related products is therefore key to a smoke-free future.

With the advent of novel tobacco products and the tobacco industry falsely marketing them as less harmful than their combustible counterparts, the adage “prevention is better than cure” has never been more important for governments to heed if we are to achieve a smoke-free future.

Here are five things that governments need to do to ensure that a smoke-free future is realised.

1. Raise taxes on tobacco products

Tobacco taxation is one of the most effective population-based strategies for decreasing tobacco consumption. On average, a 10% increase in the price of cigarettes reduces demand for cigarettes by between 4% and 6% for the general adult population.

Because they lack disposable income and have a limited smoking history, young people are more responsive to price increases than their adult counterparts. Young people’s price responsiveness is also explained by the fact that they are also more likely to smoke if their peers smoke. This suggests that an increase in tobacco taxes also indirectly reduces youth smoking by decreasing smoking among their peers.

2. Introduce 100% smoke-free environments

Smoke-free policies reduce opportunities to smoke and erode societal acceptance of smoking. Most countries have some form of smoke-free policy in place. But there are still many public spaces where smoking happens. Many of these places are frequented by young people – or example, smoking sections in nightclubs and bars – contributing to the idea that smoking is acceptable and “normal”.

Research from the United States shows that creating smoke-free spaces reduces youth smoking uptake and the likelihood of youth progressing from experimental to established smokers. In the United Kingdom , smoke-free places have been linked to a reduction in regular smoking among teenagers, and research from Australia finds that smoke-free policies were directly related to a drop in youth smoking prevalence between 1990 and 2015 . By adopting 100% smoke-free policies governments can denormalise smoking and turn youth away from tobacco and related products.

3. Adopt plain packaging and graphic health warnings

The tobacco industry uses sleek and attractive designs to market its dangerous products to young people . All tobacco products should therefore be subject to plain packaging and graphic health warnings so that their attractive packaging designs do not lead youth to underestimate the harm of using these products. Currently 125 countries require graphic images on the packaging of tobacco products. Countries like South Africa that rely on a text warning message are far behind the curve. Plain packaging on tobacco products has been adopted in 13 countries to date and, in January 2020, Israel became the first country to apply plain packaging to e-cigarettes.

4. Outlaw tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

Traditional advertising and promotion of tobacco products has been banned in most parts of the world. But the tobacco industry has developed novel ways of keeping its products in the public eye.

Some common strategies used by the industry to target youth include hiring “influencers” to promote tobacco and nicotine products on social media, sponsoring events, and launching new flavours that are appealing to youth, such as bubble gum and cotton candy, which encourages young people to underestimate the potential harm of using them. Evidence also shows how the tobacco industry uses point-of-sale marketing to target children by encouraging vendors to position tobacco and related products near sweets, snacks and cooldrinks, especially in outlets close to schools.

Governments need to outlaw these tactics and impose hefty fines on tobacco companies that make any attempt to circumvent the law.

5. Educate young people

Given that tobacco kills half of its long-term users, the tobacco industry needs to get young people addicted to its products to ensure its survival. Young people need to be made aware of this. Governments should launch counter-advertising campaigns that educate young people on the tactics employed by the industry to target them so that they do not fall prey to them.

- Public health

- World No Tobacco Day

- Smoking ban

- Tobacco tax

- Tobacco products

Head of Evidence to Action

Supply Chain - Assistant/Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Education Research Fellow

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2019

A descriptive study of a Smoke-free Teens Programme to promote smoke-free culture in schools and the community in Hong Kong

- Oi Kwan Chung 1 ,

- William Ho Cheung Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2562-769X 1 ,

- Ka Yan Ho 1 ,

- Antonio Cho Shing Kwong 2 ,

- Vienna Wai Yin Lai 2 ,

- Man Ping Wang 1 ,

- Katherine Ka Wai Lam 1 ,

- Tai Hing Lam 3 &

- Sophia Siu Chee Chan 1

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 23 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5334 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Youth smoking continues to be a significant global public health concern. To ensure healthier lives for youths, healthcare professionals need to increase awareness among the youth of the health risks and addictive nature of smoking, strengthen their ability to resist negative peer influence and curiosity, and help those who smoked to quit. The Smoke-free Teens Programme was launched in 2012 to equip youngsters with up-to-date information about smoking and global trends in tobacco control and to encourage them to play a pioneering role in tobacco control. This paper describes the process and outcomes of this programme for youths in Hong Kong.

The Smoke-free Teens Programme contained three major components: (i) a 2-day-1-night training camp; (ii) creative activities to promote smoke-free messages in schools and the community; and (iii) an award presentation ceremony to recognize the efforts of outstanding Smoke-free Teens in establishing a smoke-free culture. All secondary school students or teenagers aged 14 to 18 years from secondary schools, youth centres and uniform groups were invited to join the programme. The outcome measures were changes in (1) knowledge about smoking hazards; (2) attitudes towards smoking, tobacco control, and smoking cessation; and (3) practices for promoting smoking cessation.

A total of 856 teenagers were recruited during the study period (July 2014 to March 2017). The results showed statistically significant changes in participants’ knowledge about smoking hazards, attitudes towards tobacco control, and practice for promoting smoking cessation.

Conclusions

The Smoke-free Teens Programme demonstrated effectiveness in equipping youngsters with up-to-date information about smoking and global trends in tobacco control and in encouraging them to play a pioneering role in tobacco control. The trained Smoke-free Teens not only promoted the smoke-free messages among their schoolmates, friends, and families, but also gathered community support for a smoke-free Hong Kong. The programme has been instrumental in fostering a new batch of Smoke-free Teens to advocate smoke-free culture and protect public health.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT03291132 (retrospectively registered on September 19, 2017).

Peer Review reports

With an annual death toll of almost 7 million worldwide, cigarette smoking is the biggest preventable cause of premature death and disease [ 1 ]. Two-thirds of all premature deaths of smokers can be directly attributed to smoking, and smoking is especially hazardous for those who start smoking at a young age [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. There is evidence that smoking cessation before the age of 40 can reduce the death rate by more than 90% [ 2 ]. Even though early cessation is critical to reducing the hazard that smoking poses to an individual’s health, young people who, driven by curiosity and peer pressure, begin to experiment with smoking are likely to continue the habit into adulthood [ 7 ]. Most adult smokers started smoking when they were young [ 8 ]. It is therefore essential that healthcare professionals should increase awareness among the young of the health risks and addictive nature of smoking, strength their ability to resist negative peer influence and curiosity, and help those who smoked to quit.

Over the past 30 years, enormous efforts have been made by the Hong Kong government to raise tobacco tax and introduce legislation, law enforcement, and smoke-free campaigns, which have led to remarkable success in tobacco control [ 9 , 10 ]. The prevalence of daily cigarette smoking in Hong Kong decreased from 23.3% in 1982 to 10.5% in 2015 [ 11 , 12 ]. Nevertheless, 641,300 people aged 15 years or above still smoke daily [ 12 ] and this remains an important public health concern in Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health (COSH) was established under its own ordinance in 1987. This is a statutory body vested with various functions, as set out in the Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health Ordinance ( http://smokefree.hk/UserFiles/resources/about_us/CAP_389_Eng.pdf ), to protect and improve the health of the community by (1) informing and educating the public about smoking and health matters; (2) conducting and coordinating research into the cause, prevention, and cure of tobacco dependence; and (3) advising government, community health organizations, or any public body on matters related to smoking and health. Under this charter, COSH has been an active player and commentator on all issues related to tobacco control. To educate youngsters about smoking hazards and the latest trends in tobacco control, and to encourage them to play a pioneering role in spreading smoke-free messages, COSH launched the Smoke-free Teens Programme in 2012 (formerly named Smoke-free Youth Ambassador Leadership Training Programme). The objectives of the programme are to (1) equip a group of young leaders with up-to-date information about smoking hazards and global trends in tobacco control and to encourage them to play a pioneering role in tobacco control; (2) penatrate the smoke-free message into schools and the community via the Smoke-free Teens; (3) encourage the Smoke-free Teens to act as role models and develop a smoke-free healthy lifestyle; and (4) equip the young leaders with basic smoking cessation counseling skills. In fact, training teenagers to serve as behavior change agents has been widely suggested in the literature [ 13 ], and has been proven effective to combat alcohol use and substance abuse [ 14 , 15 ]. Yet, this strategy has not been applied to establish a smoke-free culture. To address the gap in existing literature, this paper describes an evaluation of this programme’s effectiveness in promoting the smoke-free culture among youths. However, the evaluation was carried in relation to the first three objectives, but not the fourth. This is because, some participants might not encounter any smoker during the study period; it would be difficult for us to assess their smoking cessation counseling skills.

The study evaluated the Smoke-free Teens Programme from July 2014 to March 2017. The study design and the procedure to obtain informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference UW14–412). Written consent was obtained from the participants’ parents after fully informing them of the study’s purpose and details. They were told that the participation of their child was totally voluntary and without any prejudice.

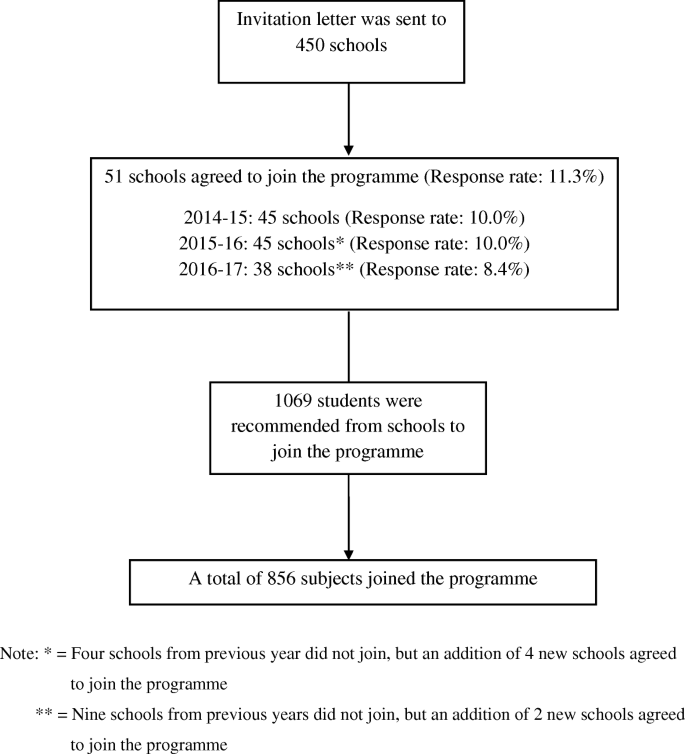

Design and participants

All students or teenagers aged 14 to 18 years from secondary schools, youth centres and uniform groups were eligible to join the Smoke-free Teens Programme. The uniform groups referred to any organization with their members wearing uniforms to signify the mission of serving different members in the community [ 16 ]. Promotion and recruitment was conducted early in each year and the programme was implemented from July to March of the next year. To recruit eligible participants, invitation letters were sent to around 450 secondary schools every year. For those schools that showed interested to join could contact us via the reply mail. Due to the limited capacity and resources., each school could only nominate around 10 students to join the programme every year. A total of 51 schools agreed to join this programme over the past 3 years. This gave an overall response rate of 11.3%. Figure 1 summarizes the recruitment process. The programme contained three major components. The first component was a 2-day-1-night training camp that aimed to train participants as Smoke-free Teens to promote a smoke-free culture. For the second component, participants were asked to organize creative activities to promote smoke-free messages in their schools and community. The third component included an award presentation ceremony to recognize the efforts of outstanding Smoke-free Teens in establishing a smoke-free culture. To publicize the Smoke-free Teens Programme, COSH produced publicity materials such as posters for display in secondary schools, youth centres, and uniform group meetings. Advertisements were placed in newspapers and magazines, on the radio, television and social media platforms. Programme webpage was set up to promote the programme and allow extended learning for the participants. COSH also organized a series of camp briefing sessions, communication skills training workshops, health talks and seminars. To evaluate the effectiveness of the training programme, a one-group pretest–posttest, within-subjects design was used.

Summary of the recruitment process

Details of the programme

Smoke-free teens training camp.

Approximately four Smoke-free Teens Training Camps were held during each summer holiday. Participants were invited to join the 2-day-1-night training camp between July and August of each year. The camp provided a wide range of adventurous and experiential indoor and outdoor activities, which were implemented by COSH and campsite coaches. In addition, health education talks were delivered by COSH staff and a registered nurse with more than 5 years’ experience in smoking cessation. The talks covered a variety of topics, including the hazardous effects of smoking, tobacco control policies, existing cessation services in Hong Kong, and basic counseling skills, etc. In addition, the participants were taught to deliver brief smoking cessation advice using the AWARD model: A sking about smoking history; W arning about the high risk that one out of every two smokers will be killed prematurely by smoking, which is the mortality risk for smokers in general suggested by World Health Organization; A dvising to quit as soon as possible; R eferring to smoking cessation clinics or hotlines; D oing it again until smokers quit smoking. The AWARD model was developed according to the clinical practice guideline for smoking cessation. It aids quitting by warning smokers of the high mortality risk of smoking and referring those in need of more intensive counseling to smoking cessation services [ 17 ]. This model has been tested in our previous studies on smoking cessation. The findings of these studies indicated that this model is effective in helping smokers in community settings quit smoking [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. By engaging in the 2-day-1-night camp activities, participants obtained the latest information about tobacco hazards and tobacco control. To help them effectively design and execute their smoke-free advocacy activities, participants were trained in a broad array of skills, including leadership, creative and critical thinking, communication, problem solving, team building, programme planning, smoking cessation counseling techniques, and social media marketing techniques.

Promoting smoke-free messages in schools and the community

After completing the training camp, participants were asked to apply the various skills they had learned to design and implement at least one smoke-free activity in their schools or the community during September–December in small groups to promote smoke-free messages. They also encouraged their friends, families, and neighbors to quit smoking and promote the concept of a smoke-free Hong Kong.

Award presentation ceremony

To commend the outstanding Smoke-free Teens and schools/organizations for their efforts in establishing a smoke-free culture, an award presentation ceremony was held in March of the following year. Smoke-free Teens who had shown outstanding performances were presented with a trophy and book voucher as encouragement. In addition, certificates were presented to Smoke-free Teens who had completed the entire programme.

To evaluate the Smoke-free Teens Programme, teenagers who participated in the programme between July 2014 and March 2017, and whose parents had signed the consent forms, were included in this evaluation study. The outcome measures were changes in (1) knowledge about smoking hazards; (2) attitudes towards smoking, tobacco control, and smoking cessation; and (3) practices for promoting smoking cessation.

Data collection

A structured questionnaire was administered by a research assistant at baseline, immediately after the training camp, and 3 and 6 months later to assess changes in participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding smoking and tobacco control. At baseline, participants were asked whether they had experienced in promoting smoking cessation in the previous 6 months. At 3- and 6-month follow-ups after attending the training camp, participants were asked to report their practice of promoting smoking cessation for the past 3 months.

Data analyses

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS: Version 23; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participant demographic characteristics. The paired samples t-test and McNemar’s test were used to assess any changes in participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding smoking and tobacco control before and after the training camp. One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA was used to assess any changes in participants’ cessation practice before and after the training camp. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the purposes of the smoke-free activities organized by the participants. Missing values were handled by the baseline-observation-carried-forward.

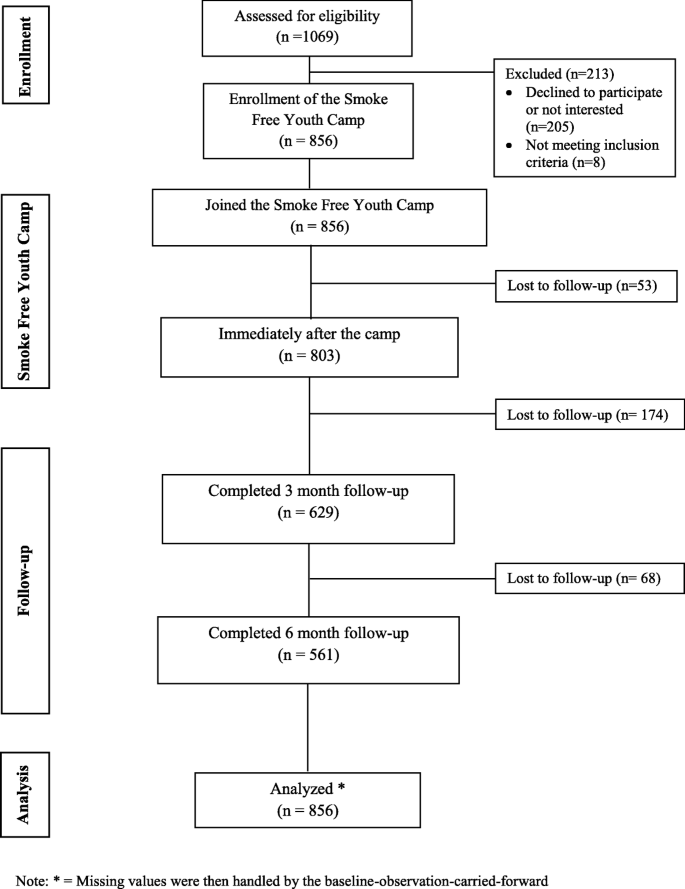

A total of 856 teenagers were recruited during the study period. However, 26.5% (227/856) and 34.5% (295/856) lost to follow-up at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Figure 2 is a CONSORT diagram tracking how the participants flowed in this evaluation study.

The CONSORT diagram showing how participants flowed in the study

Table 1 shows the participant demographic characteristics at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 15.2 (SD = 1.1) years. About 65.0% (556/856) of the participants were female and 33.2% (284/856) were male. About 46.0% (394/856) of the participants were Secondary 4 students and 82.1% (703/856) were never smokers. About 53.5% (458/856) of the participants lived with at least one smoker. Of these participants, 65.9% (302/458) lived with smokers who were their fathers.

Table 2 shows the changes in knowledge about smoking hazards. When compared with baseline, a significant improvement was observed in knowledge about smoking hazards (58.0% versus 75.0%; p = .016; correctly answered all items) at 6-month follow-up. Table 3 shows the changes in attitudes towards smoking cessation and tobacco control. Compared with baseline, significant improvements were observed in several areas at 6 months, including advising their friends to quit smoking (4.43 ± 0.68 versus 4.49 ± 0.61; p = .012), asking people not to smoke around them (4.39 ± 0.75 versus 4.50 ± 0.66; p < .001), reminding others not to smoke in non-smoking areas (4.12 ± 0.85 versus 4.29 ± 0.77; p < .001), supporting expanding non-smoking areas (4.31 ± 1.05 versus 4.50 ± 0.78; p < .001), increasing tobacco tax (4.14 ± 0.94 versus 4.39 ± 0.82 ; p < .001), and a total ban of the sale of tobacco products (4.08 ± 0.99 versus 4.43 ± 0.82; p < .001). Table 4 shows statistically significant changes in practice towards smoking cessation and tobacco control. Compared with baseline, participants reported that they had provided smoking cessation advice to more smokers (1.6 ± 1.5 versus 2.3 ± 4.3; p < .001) at 6-month follow-up. All of them also reported making more smoker referrals to existing smoking cessation services (2.2 ± 2.2 versus 3.3 ± 7.7, p < .001) at 6 months.

Over the course of the 3-year study, Smoke-free Teens organized 552 smoke-free programmes, with each group conducting 3.2 programmes on average. These programmes reached 144,528 people in schools and the community. The highly diverse programmes included among the many activities exhibitions, mosaic art and microfilm production, game booths, debate and poster design competitions, as well as the promotion of a smoke-free culture on busy streets. An outstanding example was the team that won the 2014 championship. It organized a wide range of activities including a slogan competition, game booths, an anti-cancer health talk, and video production. To enforce the smoke-free message to primary school students and the public, they also invited people to make a smoke-free pledge, distributed bookmarks and cards with smoking cessation hotline numbers to smokers, as well as hung a banner with a smoke-free slogan at a minibus terminal. Over 2000 citizens were reached by their activities.

Table 5 shows the aim of the smoke-free activities organized by the participants. Of the organized smoke-free activities, 73.6% (406/552) publicized smoke-free messages, 61.4% (339/552) educated the public about the hazardous effects of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure, 35.3% (195/552) promoted smoking cessation, 1.6% (9/552) introduced our training programme to the public, and 0.7% (4/552) discussed the economic losses caused by smoking.

Youth smoking is a global public health concern that has been regarded as a “pediatric epidemic” [ 20 ]. Building an awareness of tobacco control and smoking cessation among youths is very important in reducing smoking initiation, which in turn can lower the prevalence of cigarette use. This paper reports a study to promote a smoke-free lifestyle and smoking cessation in the community by mobilizing teenagers from secondary schools, youth centres, and uniform groups to serve as smoke-free ambassadors. In addition, we evaluated the effectiveness of the training programme by assessing changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices of tobacco control and cessation among the ambassadors.

The present study demonstrated that the training programme was effective in enhancing the knowledge of smoking hazards among youths. This is evidenced by the fact that 75.0% of participants were able to correctly answer all items at 6-month follow-up compared with only 58.0% at baseline. Moreover, there were statistically significant improvements in participants’ attitudes towards tobacco control policies, such as expanding non-smoking areas, increasing tobacco tax, and a total ban of the sale of tobacco products. In addition, the results supported the effectiveness of the training programme in changing Smoke-free Teens’ practice of smoking cessation promotion. There were statistically significant increase in the mean number of smokers who received smoking cessation advice and who were referred to smoking cessation services by participants at 6-month follow-up compared with baseline. However, caution must be taken when interpreting these findings. The results might be highly confounded by the number of smokers that the participants had encountered before and during the study. Furthermore, the results could be misleading if the participants only encountered a few smokers at baseline, but more smokers during the period of evaluation. Nevertheless, the results demonstrated that the trained Smoke-free Teens could successfully promote cessation among smokers using the AWARD model. One advantage of the AWARD model is that it can be easily learned and used by teenagers with minimal training. In addition, it takes only a minute or slightly longer to communicate advice based on the AWARD model. This makes it very useful in promoting smoking cessation in community settings and permits a sizeable number of smokers to be reached at low cost.

Following the intensive training, the Smoke-free Teens formed into groups and applied the various skills they had learned to design and implement creative projects to disseminate smoke-free messages in their schools or the community. During the study period, 552 smoke-free activities were held, which reached 144,528 people. These smoke-free activities were effective in raising public awareness about smoking hazards and obtaining support for public health policies. In addition, the activities allowed the promotion of smoke-free messages to a segment of smokers who are difficult to be reached by existing smoking cessation services. When compared with other methods in health promotion, such as educational talks and self-help materials, these activities are a practical and effective way to rapidly disseminate health messages to a large number of people.

We received much positive feedback from the trained Smoke-free Teens. One group of Smoke-free Teens commented that they found the experience of organizing such a large-scale event valuable. They felt that the experience helped them realize the importance of group unity and planning, and that the activities had fully utilized the potential of every teammate. They hoped that everyone might develop a smoke-free healthy lifestyle. Most importantly, by joining this programme, participants were not only equipped with knowledge about tobacco control and smoking hazards, but were also more likely to refrain from trying smoking in the future. One trained Smoke-free Teen of the 2016–2017 champion team stated that “I spent half a year planning and organizing the smoke-free activities and promoting a smoke-free lifestyle. I never regretted joining the programme, as what I learned and experienced was invaluable and could not be acquired at school. It is a very precious memory. Besides, my father reduced his tobacco consumption with my support and encouragement.”

There are several benefits in mobilizing secondary school students to serve as ambassadors of smoking cessation in the community. First, they may encounter smokers in their social circles. Young smokers, particularly those who are reluctant to access smoking cessation services, may be more willing (and may find it easier) to receive brief advice on smoking cessation from the ambassadors owing to the established rapport between them. Second, there are more than 300,000 secondary school students in Hong Kong [ 21 ]. Trained Smoke-free Teens could play an important role in helping to widely disseminate smoke-free messages in the community. In particular, they can motivate their smoking peers to quit by being healthy role models.

Despite only small changes in participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding smoking and tobacco control after the programme, it is meaningful and relevant to public health practice. In particular, within a 6-month period of evaluation, 856 ambassadors were able to deliver brief cessation advice to 1968 smokers in their social circles. The ambassadors also referred 2824 smokers to smoking cessation services. It was expected that the ambassadors would continue such practice after the evaluation. The running cost of this programme is low in comparison to the healthcare cost resulted from treating tobacco-related diseases of a smoker. Therefore, this innovative, inexpensive and sustainable approach can make an important contribution to establishing a smoke-free culture in schools and the community in Hong Kong, consequently saving more lives.

Limitations

There were some limitations of this study. Frist, this study was limited because only 51 out of 450 schools joined the Smoke-free Teens Programme over the past 3 years. The low response rate might be due the Hong Kong education system is exam-oriented and the schools in Hong Kong are highly academic-oriented. Majority schools in Hong Kong are mainly focused on academic results, but neglect the importance of having extra-curricular activities and building students’ personal characters. Consequently, students are busy with attending different tutorial classes after school but no more extra time for joining activities. Given the significant health impact of the Smoke-free Teens Programme on our new generation, more resources and efforts should be allocated to this area to create a rapport with schools and parents with regard to tobacco control advocacy. The second limitation was that we did not follow up smokers who had received brief smoking cessation advice from Smoke-free Teens, and hence could not evaluate the long-term impact of the training programme in the community, particularly in terms of smoking cessation outcomes. Studies with longer follow-ups are therefore warranted to examine the sustainability of the training effects. Furthermore, a comprehensive evaluation is needed to determine whether the training effects are translated into smoking cessation at an individual level. Additional measures, including (1) how many family members and friends are invited to make a quit attempt, (2) whether local quitlines receive more referrals, and (3) whether friends of ambassadors are more willing to receive cessation advices from the ambassadors in comparison to other sources could be assessed in future evaluation. The third limitation was that participation in this study was on a voluntary basis. It was expected that participants and their families were more negative towards cigarette smoking, consequently might bias the results. Despite the family background might influence the participants’ attitudes towards smoking and their smoking status [ 22 ], we did not observe any significant difference in these two variables with different family backgrounds in subgroup analyses. Future studies with more stringent design are necessary to confirm our findings.

Implications for practice

The findings from this project have important implications for future practice. The project enhanced the community’s capacity to promote smoking cessation because there was a significant improvement in the knowledge, attitudes, and smoking cessation practices of the trained Smoke-free Teens. Moreover, trained Smoke-free Teens can continue to help promote smoking cessation after training. Participants were encouraged to join the Smoke-free Teens Alumni Programme and they continue to promote a smoke-free message by attending sharing sessions, managing game booths and exhibitions in the community, and participating in other tobacco control activities organized by COSH. The World Health Organization [ 23 ] emphasizes the importance of member states implementing multisectoral control measures against the tobacco industry. By joining the Smoke-free Teens Programme, the activities of trained Smoke-free Teens could become one of the main ways of implementing the government’s tobacco control policies in Hong Kong.

Notwithstanding some limitations, the overall results of this study suggest the effectiveness of the training programme in changing knowledge about smoking hazards, attitudes towards smoking, and tobacco control and smoking cessation practices. It is encouraging that the trained Smoke-free Teens not only promoted smoke-free messages among their schoolmates, friends, and families, but also began to gather community support for a smoke-free Hong Kong. The Smoke-free Teens Programme has been instrumental in fostering a new batch of Smoke-free Teens to advocate a smoke-free culture and protect the health of the public.

Abbreviations

Ask, Warn, Advise, Refer and Do-it-again

The Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health

World Health Organization. Tobacco fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/ . Accessed 22 Oct 2018.

Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):133–41.

Article Google Scholar

Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–50.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):351–64.

Lam TH, He Y. Lam, and He respond to “the Challenge of Tobacco Control in China”. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(9):1074–5.

Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, Egger S, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Med. 2015;13:38.

Winkleby MA, Fortmann SP, Rockhill B. Cigarette smoking trends in adolescents and young adults: the Standford Five-City Project. Prev Med. 1993;22:325–34.

Li HCW, Chan SCS, Lam TH. Smoking among Hong Kong Chinese women: behavior, attitudes and experience. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:183.

Cheng MH. WHO’s Western Pacific region agrees tobacco-control plan. Lancet. 2009;374(9697):1227–8.

Koplan JP, An WK, Lam RMK. Hong Kong: a model of successful tobacco control in China. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1330–1.

Census & Statistics Department. Pattern of smoking, Thematic Household Survey Report No:26. Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong SAR Government; 2006.

Google Scholar

Census & Statistics Department. Pattern of smoking, Thematic Household Survey Report No:59. Hong Kong: Hong Kong SAR Government; 2016.

Makhoul J, Alameddine M, Afifi RA. ‘I felt that I was benefiting someone’: youth as agents of change in a refugee community project. Health Educ Res. 2011;27(5):914–26.

Chico-Jarillo TM, Crozier A, Teufel-Shone NI, Hutchens T, George M. A brief evaluation of a project to engage American Indian young people as agents of change in health promotion through radio programming, Arizona, 2009–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E23.

Black DR, Tobler NS, Sciacca JP. Peer helping/involvement: an efficacious way to meet the challenge of reducing alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among youth. J Sch Health. 1998;68(3):87–93.

Joseph N, Alex N. The uniform: a sociological perspective. Am J Sociol. 1972;77(4):719–30.

Suen YN, Wang MP, Li WHC, Kwong ACS, Lai VWY, Chan SSC, Lam TH. Brief advice and active referral for smoking cessation services among community smokers: a study protocol for randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):387.

Wang MP, Li WH, Cheung YT, Lam OB, Wu Y, Kwong AC, Lai VW, Chan SS, Lam TH. Brief Advice on Smoking Reduction Versus Abrupt Quitting for Smoking Cessation in Chinese Smokers: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Nicotine Tob Res. in press.

Wang MP, Suen YN, Li WHC, Lam OB, Wu Y, Kwong A, Lai V, Chan SSC, Lam TH. Intervention with brief cessation advice plus active referral for proactively recruited community smokers: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. in press.

Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Substance Abuse, Committee on Adolescence, & Committee on Native American Child Health. Tobacco use: a pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1474–84.

Education Bureau. Secondary Education. 2017. http://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/publications-stat/figures/sec.html . Accessed 23 Oct 2018.

McGee CE, Trigwell J, Fairclough SJ, et al. Influence of family and friend smoking on intentions to smoke and smoking-related attitudes and refusal self-efficacy among 9–10 year old children from deprived neighbourhoods: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:225.

World Health Organization. Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI). 2017. http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/ . Accessed 23 Oct 2018.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Diane Williams, PhD, from Edanz Group ( www.edanzediting.com/ac ) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

This study is funded by the Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health (#260007591). We would like to declare that the funding body did not have any role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, the interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, The University of Hong Kong, 4/F, William M.W. Mong Block, 21 Sassoon Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China

Oi Kwan Chung, William Ho Cheung Li, Ka Yan Ho, Man Ping Wang, Katherine Ka Wai Lam & Sophia Siu Chee Chan

The Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China

Antonio Cho Shing Kwong & Vienna Wai Yin Lai

School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China

Tai Hing Lam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

OKC, WHCL, KYH, KKWL, MPW, ACSK, VWYL, THL and SSCC contributed in study concept and design. OKC, WHCL, KYH participated in acquisition of data. OKC, KYH, WHCL, KKWL analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors participated in drafting, reading and approving the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to William Ho Cheung Li .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference UW14-412). Written consent was obtained from the participants’ parents after fully informing them of the study’s purpose and details.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chung, O.K., Li, W.H.C., Ho, K.Y. et al. A descriptive study of a Smoke-free Teens Programme to promote smoke-free culture in schools and the community in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health 19 , 23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6318-4

Download citation

Received : 17 January 2018

Accepted : 12 December 2018

Published : 07 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6318-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ambassadors

- Tobacco control

- Youth smoking

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

U.S. RESOURCES

Global resources.

- ADVOCACY TOOLS

President Biden: Finalize Rule to Ban Menthol Cigarettes

Meet Yolonda Richardson, Our New President & CEO

FDA: Protect Kids by Eliminating All Flavored E-Cigarettes

Big Tobacco Must Post Signs About Smoking Risks at 220,000 U.S. Stores

Report “Corrective Statement” violations using tipline

Youth Advocates of the Year Awards – 2024 Honorees

Meet our honorees – young leaders and public health champions from the U.S. and around the world

#SponsoredByBigTobacco

New report on tobacco and nicotine marketing on social media.

India Requires Tobacco Warnings On Streaming Services

Rules apply to movies and programs with tobacco depictions

Campaign for the Culture

Learn about our new initiative to educate and engage communities most impacted by tobacco use

Mexico Passes Comprehensive Smoke-Free Law

Historic measure will protect 130 million people from secondhand smoke, reduce tobacco use and save lives

Help us protect kids and save lives

JOIN THE FIGHT

Get action alerts and updates

TOOLS TO WIN THE FIGHT

Get the facts on key issues and tobacco’s toll in the U.S. and by state.

VIEW RESOURCES

Get the facts on key issues and tobacco’s toll worldwide and in countries where we work.

INDUSTRY WATCH

Find out how the tobacco industry targets kids, deceives the public and fights life-saving policies across the globe.

LEARN MORE

YOUTH INITIATIVES

Find out how we’re training and mobilizing youth to create the first tobacco-free generation.

Building on the successes and lessons learned in the global fight against tobacco, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids launched the Global Health Advocacy Incubator in 2014 to address other critical public health challenges around the globe.

LATEST NEWS

- Tobacco Giant British American Tobacco Lobbying for “Kiddie” Cigarette Packs, Pakistan Government Must Reject Alarming Proposal Press Release | Jul 31, 2024

- New Tobacco Control Regulations for Indonesia Will Drive Down Tobacco Use Rates if Strongly Implemented Press Release | Jul 31, 2024

- Health Equity and Accountability Act of 2024 Addresses Glaring Health Disparities, Including Those Caused by Tobacco Press Release | Jul 25, 2024

- FDA Reports Progress in Reviewing E-Cigarette Marketing Applications, But Must Step Up Enforcement Against Illegal Products that Harm Kids Press Release | Jul 23, 2024

- U.S. Supreme Court Agrees to Hear Case Involving FDA Marketing Denial Orders for Flavored E-Cigarettes Press Release | Jul 02, 2024

- Tobacco Giant Reynolds Introduces New Fruity E-Cigarettes to Confuse Kids and Evade Regulation Press Release | Jul 01, 2024

© 2024 Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Tobacco-Free Future

Related Papers

Archives of Disease in Childhood

Zubair Kabir , L. Clancy

Anne O'Farrell

Child: Care, Health and Development

Institute of Public Health in Ireland

JOANNA PURDY

European Journal of Pediatrics

susan bewley

Michal Molcho

Archives of disease in childhood

Aziz Sheikh

Pediatric allergy, immunology, and pulmonology

Alexander Prokhorov

Tobacco use currently claims >5 million deaths per year worldwide and this number is projected to increase dramatically by 2030. The burden of death and disease is shifting to low- and middle-income countries. Tobacco control initiatives face numerous challenges including not being a high priority in many countries, government dependence upon immediate revenue from tobacco sales and production, and opposition of the tobacco industry. Tobacco leads to environmental harms, exploitation of workers in tobacco farming, and increased poverty. Children are especially vulnerable. Not only do they initiate tobacco use themselves, but also they are victimized by exposure to highly toxic secondhand smoke. Awareness of tobacco adverse health effects is often superficial even among health professionals. The tobacco industry continues to aggressively promote its products and recognizes that children are its future. The tools and knowledge exist, however, to dramatically reduce the global burde...

Tobacco Prevention & Cessation

Diane O Doherty

Tobacco Control

Michelle Sims

"Objective To examine the impact of the ban on smoking in enclosed public places implemented in England in July 2007 on children's exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke. Design Repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population in England. Setting The Health Survey for England. Participants Confirmed non-smoking children aged 4–15 with measured saliva cotinine participating in surveys from 1998 to 2008, a total of 10 825 children across years. Main outcome measures The proportion of children living in homes reported to be smoke-free; the proportion of children with undetectable concentrations of cotinine; geometric mean cotinine as an objective indicator of overall exposure. Results Significantly more children with smoking parents lived in smoke-free homes in 2008 (48.1%, 95% CI 43.0% to 53.1%) than in either 2006 (35.5%, 95% CI 29.7% to 41.7%) or the first 6 months of 2007, immediately before the ban came into effect (30.5%, 95% CI 19.7% to 43.9%). A total of 41.1% (95% CI 38.9% to 43.4%) of children had undetectable cotinine in 2008, up from 34.0% (95% CI 30.8% to 37.3%) in 2006. Geometric mean cotinine in all children combined was 0.21 ng/ml (95% CI 0.20 to 0.23) in 2008, slightly lower than in 2006, 0.24 ng/ml (95% CI 0.21 to 0.26). Conclusions Predictions that the 2007 legislative ban on smoking in enclosed public places would adversely affect children's exposure to tobacco smoke were not confirmed. While overall exposure in children has not been greatly affected by the ban, the trend towards the adoption of smoke-free homes by parents who themselves smoke has received fresh impetus."

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Ruairi Brugha

Manfred Neuberger

British Medical Journal

Dorothy Currie

Tobacco control

Laura Currie Murphy

Lai-ming Ho

Christine Godfrey

BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Zubair Kabir

Ron Borland

The British Journal of Psychiatry

Rosaria Galanti

marjeta majer

Preventive Medicine

Martin Jarvis

Ricardo Almon

udaya bhaskar

Primary Care at a Glance - Hot Topics and New Insights

Elisa Puigdomenech-puig

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

Naomi Priest

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The dangers of smoking, possible pro-tobacco arguments, annotated bibliography.

Tobacco use, including smoking, has become a universally recognized issue that endangers the health of the population of our entire planet through both active and second-hand smoking. Pro-tobacco arguments are next to non-existent, while its harm is well-documented and proven through past and contemporary studies (Jha et al., 2013). Despite this fact, smoking remains a widespread habit that involves about one billion smokers all over the world, even though lower-income countries are disproportionally affected (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). In this essay, I will review the dangers of tobacco use and consider some of the remaining pro-tobacco arguments to demonstrate that no reason can explain or support the choice to smoke, which endangers the smoker and other people.

Almost every organ and system in the human body is negatively affected by tobacco, which is why smoking is reported to cause up to six million deaths on an annual basis (WHO, 2016, para. 2). The figure is expected to grow and increase by two million within the next fifteen years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016a). Smoking can cause cancer in at least sixteen organs (including the respiratory and digestive systems), autoimmune diseases (including diabetes), numerous heart and blood problems (including stroke and hypertension); in addition, it damages lungs, vision, and bones, and leads to reproductive issues (including stillbirth) (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016).

Moreover, nicotine is addictive, and its withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, which tends to cumulate and contribute to stress (Parrott & Murphy, 2012). Other symptoms may involve mood swings and increased hunger, as well as thinking difficulties (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016b). Sufficient evidence also indicates that smoking is correlated with alcohol use and that it is capable of affecting one’s mental state to the point of heightening the risks of development of disorders (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014).

In the end, smoking reduces the human lifespan, as a result of which smokers are twice as likely as non-smokers to die between the ages of 25 and 79 (Jha et al., 2013, p. 341). Fortunately, smoking cessation tends to add up to ten years of life for former smokers, if they were to give up smoking before they turned 40 (Jha et al., 2013, p. 349). Similarly, the risk of developing mental issues also tends to be reversed to an extent, but it is not clear if it becomes completely eliminated or not (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014). The CDC (2016b) also reports that smoking cessation results in an improved respiratory condition and lower risks of developing cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and infertility.

At the same time, Cavazos-Rehg et al. (2014) state that there is not sufficient evidence to indicate that smoking cessation may cause mental issues, which implies that ceasing to smoke is likely to be a very good decision. Unfortunately, it is not always easy; many people make several attempts at quitting, experiencing difficulties because of abstinence symptoms, and in the process may gain weight and may require the help of professional doctors and counselors (CDC, 2016b). It is also noteworthy that only twenty-four countries in the world have comprehensive services aimed specifically at smoking cessation assistance (WHO, 2016, para. 18).

To sum up, tobacco is a drug that is harmful to people’s health, but it is also the basis of a gigantic industry that is subject to taxes, which implies that governments are typically interested in its development (CDC, 2016a). As a result, their spending in the field of prevention and cessation activities may not live up to expectations, despite the fact that governments have multiple means of reducing tobacco consumption, in particular, banning ads, adding taxes, and eliminating illicit trade (WHO, 2016). In the meantime, people who smoke search for arguments in order to rationalize their choice, which contributes to the deterioration of their own health and that of their communities.

It Is Not That Dangerous

It is admittedly difficult to find a reputable source that would promote smoking, which is understandable. However, certain pro-tobacco arguments can be suggested for the sake of attempting to understand the reasons for the phenomenon. For example, given the obvious lack of positive judgments, it may be hinted that the problem is overrated and the horrors of tobacco use are exaggerated. In this case, it is implied that scientific studies that highlight the dangers of smoking are not trustworthy to some extent. In fact, it cannot be denied that untrustworthy studies exist, but the scientific community does its best to eliminate them.

For example, the article by Moylan, Jacka, Pasco, and Berk (2012) contains a critique of 47 studies, which allows the authors to conclude that some research studies do not introduce sufficient controls. Despite this, the authors maintain that there is satisfactory evidence that indicates a correlation between certain mental disorders and smoking. They also admit that the evidence is less homogenous for some disorders, and suggest carrying out a further examination. As a result, it appears possible to consider the effects of tobacco use that are described by reputable organizations and peer-reviewed articles to be correct, which implies that all the horrible outcomes are indeed a possibility.

Tobacco Has Positive Effects

Given the information about tobacco’s negative effects, any number of positive ones that it may have appears insignificant. However, these may still be regarded as a pro-tobacco argument. One example is a calming, “feeling-good” effect that smokers tend to report. Parrott and Murphy (2012) explore this phenomenon, along with other mood-related effects of tobacco use, and explain that the feeling of calmness is the result of abstinence symptoms abatement.

In other words, smokers do not experience calmness when they get a cigarette; instead, they just stop experiencing abstinence-related anxiety. Moreover, apart from causing anxiety as an abstinence symptom, smoking tends to heighten the risks of various mental disorders, including anxiety disorder (Moylan et al., 2012), and alcohol use disorder (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014). It may be suggested that the belief in the positive effects of smoking is likely to result from the lack of education on the matter (WHO, 2016).

It Is My Free Choice

The freedom of choice is important to defend, and some may argue that they like the taste of the smoke or enjoy some of its effects (like the above-mentioned calming one), and they have the right to make a choice with regard to what they are going to do with their lives. Unfortunately, there is a factor that makes their choice more socially significant: Second-hand smoke intake also can affect people’s health in a negative way.

WHO (2016) estimates that about 600,000 non-smoking people, who never chose to smoke but were forced to inhale some second-hand smoke, die every year because of smoking-related issues (para. 2). In 2004, twenty-eight percent of second-hand smoke victims were children (WHO, 2016, para. 14). In other words, a smoker needs to be cautious and attempt to ensure that no deaths are caused by his or her free choice.

Moreover, even the freedom of the choice to smoke is sometimes questionable. In particular, the media has been accused of creating alluring images of smoking, which impairs the ability of people to make their own decisions (Malaspina, 2014). Similarly, the phenomenon of social smoking is explained by the wish to fit in within a community, to which teenage persons are especially prone (Nichter, 2015). As a result, the free choice argument may be regarded as typically invalid, which makes tobacco smoking even less reasonable or defensible.

It is extremely simple to argue against tobacco use: The activity has virtually no pluses, and any advantage that can be discovered by a diligent researcher would probably seem insignificant when contrasted to all the problems that smoking tends to cause. Despite this, people proceed to smoke as a result of the lack of education on the matter (WHO, 2016), harmful media images (Malaspina, 2014), and probably a number of other factors.

It is noteworthy, though, that since 2002, the number of people who have managed to quit smoking exceeds that of active smokers (CDC, 2016b, para. 22). Given the pressure of WHO (2016) in urging governments to do more to improve the situation, we may hope that tobacco use will be greatly reduced in the future, and people will stop engaging in this kind of self-harm.

Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Breslau, N., Hatsukami, D., Krauss, M. J., Spitznagel, E. L., Grucza, R. A.,… & Bierut, L. J. (2014). Smoking cessation is associated with lower rates of mood/anxiety and alcohol use disorders . Psychological Medicine , 44 (12), 2523-2535. Web.

The article investigates the correlation between smoking cessation and certain mental disorders with the help of data from a national longitudinal study that was carried out in the United States between 2001 and 2006 by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The article concludes that there is a drop in anxiety disorder as well as the use of alcohol that is related to giving up smoking. The authors highlight the fact that the conclusion is not final and suggest that additional investigation is required. However, in their view, the idea that smoking cessation is related to an increased risk of anxiety disorders remains unproven and even contradicted by the results of their research.

For this essay, the article contributes information about the relationships between smoking and mood issues, which contradicts the myth about nicotine calming people. Also, it demonstrates the positive effects of giving up smoking, which is an argument against continued smoking.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Smoking & tobacco use. Web.

The website offers fast facts on tobacco use, including those for the world and the United States, and illustrates them with the help of statistics. The facts demonstrate that smoking has a negative impact on human health (limiting the lifespan and causing diseases) and results in significant costs for countries (primarily as healthcare expenditures). Also, the website mentions that tobacco prevention expenditures and efforts are often limited. The website finishes with statistics that illustrate the scope of the problem, that is, the number of smokers in the United States.

For this essay, the website contributes useful information and statistics on smoking and its consequences, including data on costs. Also, it mentions the profitability of the tobacco industry, and the issue of preventive measures, arguments that are capable of explaining the phenomenon of the continued existence of the problem of smoking.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). Quitting smoking . Web.

The website contains information on the difficulties in quitting, provides relevant statistics, and suggests informative and supportive resources for those who wish to quit. It also highlights the dangers of smoking, the benefits of quitting, and the specifics of nicotine dependence.

For this essay, the website contributes some information on the dangers of smoking with a particular emphasis on the dependence and its consequences. The statistics can be used for illustrative purposes, in particular, with respect to quitting difficulties. However, the website also demonstrates that quitting is possible and beneficial, which is an argument against continued smoking that can be employed in the essay.

Jha, P., Ramasundarahettige, C., Landsman, V., Rostron, B., Thun, M., Anderson, R. N.,… & Peto, R. (2013). 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States . New England Journal of Medicine , 368 (4), 341-350. Web.

The article is devoted to conducting a new research on life expectancy in smokers in order to take into account new factors of the changing environment. Also, the authors consider the life expectancy of the people who have quitted smoking. The study has an impressive sample size: It uses 202,248 histories of smoking cessation. The authors conclude that smokers’ lives are shorter while ceasing to smoke can help to “gain” several years, especially if it is done before the age of 40.

The article offers evidence on lifespan reduction as a result of smoking, and some data on smoking cessation benefits that can be used in the essay as arguments and illustrations. Also, the sample size of the article implies its credibility, making it a more attractive source.

Malaspina, A. (2014). False images, deadly promises . Broomall, Pa.: Mason Crest.

The book contains much information on smoking risks, but it focuses on the role of the media in popularizing this habit. Also, it considers other reasons for taking up smoking, including peer pressure, and mentions the problem of the profitability of the tobacco industry, which hinders the process of smoking eradication.

The book offers a comprehensive overview of the costs of tobacco, which makes it a very useful source. For the essay, the book contributes the study of media tobacco images, which is an interesting perspective. It can be used to demonstrate the question of free choice and the effect of the media on that choice.

Moylan, S., Jacka, F., Pasco, J., & Berk, M. (2012). Cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of population-based, epidemiological studies . BMC Medicine , 10 (1), 123. Web.

The article reviews studies that are devoted to the correlation between anxiety and other mental disorders and smoking. The authors criticize some of the studies, demonstrating that there is limited evidence in some of them, but still conclude that the correlation between smoking and the risk of developing some disorders (in particular, generalized anxiety disorder) is sufficiently proven.

For the essay, the article provides direct information on tobacco use and its consequences and also demonstrates that unscrupulous studies are not unlikely to be produced, but this fact does not prove the lack of dangers in smoking. The existence of unscrupulous studies can be used as a pro-tobacco argument. Given the fact that it is difficult to find reputable sources that contain an alternative (approving) perspective on tobacco, it is a very important contribution to an argumentative essay.

Nichter, M. (2015). Lighting up . New York, NY: NYU Press.

The book contains a significant amount of information on tobacco-related issues, and it specifically focuses on the phenomenon of social smoking in college students. In particular, it discusses the issue of peer pressure as well as wrong perceptions, which are, in part, caused by the media. For example, it examines the harmful stereotype of smoking having a calming effect, which tends to attract youngsters who are experiencing a crisis.

The book is quite comprehensive and contains much useful information on smoking myths. For the essay, the book offers an explanation of one of the reasons for taking up smoking and demonstrates its harmfulness. It can be used to prove a pro-tobacco argument to be false and destructive.

Parrott, A. & Murphy, R. (2012). Explaining the stress-inducing effects of nicotine to cigarette smokers . Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental , 27 (2), 150-155. Web.

The authors explain the mechanism of the abstinence symptoms in smokers, relate it to resulting anxiety disorders, and demonstrate that the perceived calming effect of smoking consists of addiction consequences. In other words, the authors demonstrate that tobacco is only capable of removing the abstinence-related anxiety caused by smoking tobacco, which makes the effect pointless. The authors also review prior studies and show that non-smokers or quitters are less likely to report irritability, stress, depression, and anxiety than smokers.

For the essay, the article explains one of the few pro-tobacco arguments (that smoking has a calming effect) and proves that it is false and harmful. As a result, the article is an important contribution that provides some information on the opposite point of view, according to which there are benefits to smoking, and proves it wrong.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2016). Effects of smoking on your health .

The website contains detailed information on health-related smoking effects. It demonstrates that there is hardly a part of a smoker’s body that remains unaffected. Also, the website describes particular issues that are caused by smoking, with respect to every specific part of a human body.

The website is the most comprehensive yet concise source in this bibliography with respect to smoking-related health issues. It presents information in the form of lists and pictures, which helps it to provide more details while taking up less space and readers’ time. For the essay, the website offers information on the health problems that are caused by smoking and describes them in greater detail than the rest of the sources.

World Health Organization. (2016). Tobacco fact sheet . Web.

The website offers limited statistics and information on the dangers of smoking and the process of quitting. Among other things, it describes the dangers of “second-hand” smoke with relevant statistics and an emphasis on the consequences for young children. Also, its states the WHO’s position on the matter, as well as the organization’s recommendations for government-level anti-tobacco activities.

For the essay, the website provides useful tobacco-related information that includes global statistics; the “second-hand” smoke information is also a very important argument that should be used in the paper. Moreover, the website creates a sense of urgency by demonstrating that the issue of tobacco smoking requires the attention of governments and healthcare organizations all over the world.

- Ethiopia's Health Concerns

- Tobacco Use Prevention Programs in Atlanta

- Luxury Perspectives: Second-Hand Exclusivity

- Quitting Smoking and Related Health Benefits

- Lifestyle Management While Quitting Smoking

- Occupational Health and Toxicology in the UAE

- Obesity: Predisposing Factors and Treatment

- Equality, Diversity and Human Rights in Healthcare

- Cell Phones and Health Dangers

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 28). Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tobacco-smoking-and-its-dangers/

"Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers." IvyPanda , 28 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/tobacco-smoking-and-its-dangers/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers'. 28 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers." August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tobacco-smoking-and-its-dangers/.

1. IvyPanda . "Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers." August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tobacco-smoking-and-its-dangers/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Tobacco Smoking and Its Dangers." August 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tobacco-smoking-and-its-dangers/.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Anniversary

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 3

- Human rights and ethical considerations for a tobacco-free generation

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Yvette van der Eijk 1 ,

- Gerard Porter 2

- 1 Centre for Biomedical Ethics , National University of Singapore , Singapore , Singapore

- 2 School of Law , University of Edinburgh , Edinburgh , UK

- Correspondence to Yvette van der Eijk, Centre for Biomedical Ethics, National University of Singapore, 10 Medical Drive 02-01, Singapore 117597, Singapore; y.vandereijk{at}nus.edu.sg

In recent years, a new tobacco ‘endgame’ has been proposed: the denial of tobacco sale to any citizen born after a certain year, thus creating new tobacco-free generations. The proposal would not directly affect current smokers, but would impose a restriction on potential future generations of smokers. This paper examines some key legal and ethical issues raised by this proposal, critically assessing how an obligation to protect human rights might limit or support a state's ability to phase out tobacco.

- Human rights

- Priority/special populations

- Public policy

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051125

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Most anti-tobacco policies and legislation ratified under the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) aim to reduce smoking prevalence. Recent years, however, have seen the rise of tobacco ‘endgame’ proposals that aim to end smoking altogether. 1 One such proposal, termed the ‘Tobacco Free Generation 2000’ (TFG2000) would deny tobacco supply to any citizen born on or after a certain date (in this case, 1 January 2000) in addition to current restrictions, thus phasing out tobacco consumption for good. Public support would be sought through education initiatives and promotion of TFG2000 to the post-2000 birth cohorts. Regions most involved in this specific movement so far include Singapore, Tasmania (Australia), and Guernsey (UK). The rationale is that current policies based on the WHO FCTC have been able to reduce smoking prevalence, depending on the country, to roughly 15–25%, but no further. 2 Smoking continues to kill roughly 6 million people per year worldwide, a significant proportion of whom have never smoked. 2 Moreover, in places such as Singapore, smoking among younger generations is on the rise. 3 Together, this suggests that measures beyond the FCTC, that target youth in particular, are necessary to further reduce the public health burdens of smoking.

In 2010, a Singaporean TFG2000 proposal was published in this journal. 3 Population surveys conducted in Singapore indicate strong public support: 60.0% of smokers and 72.7% of non-smokers surveyed would endorse TFG2000. The authors argued that their proposal more correctly conveys the message to young people that smoking is not an appropriate social behaviour at any age. It also allows governments to continue to collect tobacco tax revenue for several decades and does not create further impositions on current smokers. Implementing the ban only for citizens and Permanent Residents (PRs) ensures tourism and foreign employment trades are unaffected. Hence, given the public support, the phase out was regarded as ‘a feasible next step in reducing tobacco consumption’. 3

The TFG2000 proposal also caught on elsewhere. Earlier this year, a unanimous vote in Tasmania's Upper House passed the same proposal. 4 In Guernsey, the idea is also being considered. 5 Finland 6 and New Zealand 7 also share visions of a tobacco endgame, but their exact strategies for achieving it have not been determined yet. It is worth noting that the five places mentioned all have tough anti-tobacco policies that also target smoking uptake in youth, and no tobacco growers. Hence, they are more likely candidates for TFG2000 than countries where tobacco growing contributes substantially towards the economy, or where smoking is a highly accepted part of the culture. The proposal, however, also raises important questions about whether its goal—to fully phase out tobacco consumption—is ethical and legally defensible in light of the current human rights debate, and whether certain practical challenges to its implementation could be overcome. Concerns about loss of tax revenue and compatibility with world trade and investment law are also relevant, but beyond the scope of this paper, which focuses on the human rights issues involved.

Our central argument is that TFG2000 is compatible with human rights principles, and may even form part of a successful human rights-based strategy for tobacco control.

The relationship between human rights and tobacco control

Human rights were established to protect fundamental values such as the ability to live, have a family and be free from cruel treatment. In this paper, we will analyse the TFG2000 proposal in reference to four international human rights documents: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 8 (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 9 (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 10 (ICESCR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child 11 (CRC). These instruments themselves have no direct legal effect; the idea is that states that have signed the document incorporate these rights into their own legal systems. Thus, aggrieved individuals may make human rights arguments in their state's domestic courts or similar systems. State compliance with the principles outlined in human rights treaties is tracked using periodical shadow reports, submitted to the UN by non-state bodies such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Previously, it was suggested in this journal that the human rights to life, health and a healthy environment should be used as the basis for a ‘right to tobacco control’. 12 This would impose a corresponding duty on the state to pursue various means of restricting tobacco use. Human rights rhetoric, however, has been used on both sides of the debate. Pro-smoking advocates have drawn upon the rights to liberty, self-determination and privacy in support of a ‘right to smoke’. Would ‘tobacco-free generation’ legislation violate or support these rights?

Below, we examine some key human rights debates and their relevance to the TFG2000 proposal: the rights to life and health, the rights to liberty and self-determination, the right to privacy and rights to equality and non-discrimination. We finish with some practical indications for the future.

Human rights to life and health: protecting children from second-hand smoke

The human right to life is a fundamental right recognised in UDHR article 3, ICCPR article 6 and for children in CRC article 6. The human right to health is recognised in ICESCR article 12. Human rights may be ‘positive’ or ‘negative’: for example, an entitlement to state provision and funding for programmes that contribute to good health (positive) or a right to be free from the actions of others that may impair health (negative). 13 Thus, the dangers posed to non-smokers by second-hand smoke (SHS) can be construed as an infringement of a non-smoker's negative rights. The effects of SHS, especially in children, are worth noting: passive exposure to parental smoking leads to middle ear infections, respiratory diseases including asthma, the worsening of serious conditions such as cystic fibrosis and asthma, and in some cases, death. 14 Given these clear risks, it could be argued that failing to prevent child exposure to SHS affects their basic rights to life and health, and their right to ‘a clean and safe environment’ (CRC article 14). 11

Arguably, governments already protect non-smokers to some extent through public smoking restrictions. Such measures are helpful, but cannot eliminate SHS completely, leaving many non-smokers, especially children, at risk in private places such as the home. Children with asthma in particular are at risk of developing respiratory conditions; but even in countries such as the USA, where public smoking bans are common, the majority (53.2%) of children with asthma are still exposed to SHS. 15 Governments could go one step further by banning smoking inside family homes, but enforcing such a rule would be difficult. In other words, so long as cigarettes are freely available, and contact with SHS is possible, it is practically impossible to eliminate SHS exposure to children, even with very stringent laws against SHS.

The TFG2000 proposal would not immediately protect all children from SHS, because those born just after 2000 may still be exposed to the SHS of smokers born before 2000. However, full child protection from SHS, and thus the right to be free from the health effects of SHS, may be realised in the long run, as tobacco is phased out and later generations that follow are no longer exposed to SHS by their elders born after 2000.

Human rights to life and health: protection from active smoking and addiction