What Is Reflective Writing? (Explained W/ 20+ Examples)

I’ll admit, reflecting on my experiences used to seem pointless—now, I can’t imagine my routine without it.

What is reflective writing?

Reflective writing is a personal exploration of experiences, analyzing thoughts, feelings, and learnings to gain insights. It involves critical thinking, deep analysis, and focuses on personal growth through structured reflection on past events.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about reflective writing — with lots of examples.

What Is Reflective Writing (Long Description)?

Table of Contents

Reflective writing is a method used to examine and understand personal experiences more deeply.

This kind of writing goes beyond mere description of events or tasks.

Instead, it involves looking back on these experiences, analyzing them, and learning from them.

It’s a process that encourages you to think critically about your actions, decisions, emotions, and responses.

By reflecting on your experiences, you can identify areas for improvement, make connections between theory and practice, and enhance your personal and professional development. Reflective writing is introspective, but it should also be analytical and critical.

It’s not just about what happened.

It’s about why it happened, how it affected you, and what you can learn from it.

This type of writing is commonly used in education, professional development, and personal growth, offering a way for individuals to gain insights into their personal experiences and behaviors.

Types of Reflective Writing

Reflective writing can take many forms, each serving different purposes and providing various insights into the writer’s experiences.

Here are ten types of reflective writing, each with a unique focus and approach.

Journaling – The Daily Reflection

Journaling is a type of reflective writing that involves keeping a daily or regular record of experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

It’s a private space where you can freely express yourself and reflect on your day-to-day life.

Example: Today, I realized that the more I try to control outcomes, the less control I feel. Letting go isn’t about giving up; it’s about understanding that some things are beyond my grasp.

Example: Reflecting on the quiet moments of the morning, I realized how much I value stillness before the day begins. It’s a reminder to carve out space for peace in my routine.

Learning Logs – The Educational Tracker

Learning logs are used to reflect on educational experiences, track learning progress, and identify areas for improvement.

They often focus on specific learning objectives or outcomes.

Example: This week, I struggled with understanding the concept of reflective writing. However, after reviewing examples and actively engaging in the process, I’m beginning to see how it can deepen my learning.

Example: After studying the impact of historical events on modern society, I see the importance of understanding history to navigate the present. It’s a lesson in the power of context.

Critical Incident Journals – The Turning Point

Critical incident journals focus on a significant event or “critical incident” that had a profound impact on the writer’s understanding or perspective.

These incidents are analyzed in depth to extract learning and insights.

Example: Encountering a homeless person on my way home forced me to confront my biases and assumptions about homelessness. It was a moment of realization that has since altered my perspective on social issues.

Example: Missing a crucial deadline taught me about the consequences of procrastination and the value of time management. It was a wake-up call to prioritize and organize better.

Project Diaries – The Project Chronicle

Project diaries are reflective writings that document the progress, challenges, and learnings of a project over time.

They provide insights into decision-making processes and project management strategies.

Example: Launching the community garden project was more challenging than anticipated. It taught me the importance of community engagement and the value of patience and persistence.

Example: Overcoming unexpected technical issues during our project showed me the importance of adaptability and teamwork. Every obstacle became a stepping stone to innovation.

Portfolios – The Comprehensive Showcase

Portfolios are collections of work that also include reflective commentary.

They showcase the writer’s achievements and learning over time, reflecting on both successes and areas for development.

Example: Reviewing my portfolio, I’m proud of how much I’ve grown as a designer. Each project reflects a step in my journey, highlighting my evolving style and approach.

Example: As I added my latest project to my portfolio, I reflected on the journey of my skills evolving. Each piece is a chapter in my story of growth and learning.

Peer Reviews – The Collaborative Insight

Peer reviews involve writing reflectively about the work of others, offering constructive feedback while also considering one’s own learning and development.

Example: Reviewing Maria’s project, I admired her innovative approach, which inspired me to think more creatively about my own work. It’s a reminder of the value of diverse perspectives.

Example: Seeing the innovative approach my peer took on a similar project inspired me to rethink my own methods. It’s a testament to the power of sharing knowledge and perspectives.

Personal Development Plans – The Future Blueprint

Personal development plans are reflective writings that outline goals, strategies, and actions for personal or professional growth.

They include reflections on strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Example: My goal to become a more effective communicator will require me to step out of my comfort zone and seek opportunities to speak publicly. It’s daunting but necessary for my growth.

Example: Identifying my fear of public speaking in my plan pushed me to take a course on it. Acknowledging weaknesses is the first step to turning them into strengths.

Reflective Essays – The Structured Analysis

Reflective essays are more formal pieces of writing that analyze personal experiences in depth.

They require a structured approach to reflection, often including theories or models to frame the reflection.

Example: Reflecting on my leadership role during the group project, I applied Tuckman’s stages of group development to understand the dynamics at play. It helped me appreciate the natural progression of team development.

Example: In my essay, reflecting on a failed project helped me understand the role of resilience in success. Failure isn’t the opposite of success; it’s part of its process.

Reflective Letters – The Personal Correspondence

Reflective letters involve writing to someone (real or imagined) about personal experiences and learnings.

It’s a way to articulate thoughts and feelings in a structured yet personal format.

Example: Dear Future Self, Today, I learned the importance of resilience. Faced with failure, I found the strength to persevere a nd try again. This lesson, I hope, will stay with me as I navigate the challenges ahead.

Example: Writing a letter to my past self, I shared insights on overcoming challenges with patience and persistence. It’s a reminder of how far I’ve come and the hurdles I’ve overcome.

Blogs – The Public Journal

Blogs are a form of reflective writing that allows writers to share their experiences, insights, and learnings with a wider audience.

They often combine personal narrative with broader observations about life, work, or society.

Example: In my latest blog post, I explored the journey of embracing vulnerability. Sharing my own experiences of failure and doubt not only helped me process these feelings but also connected me with readers going through similar struggles. It’s a powerful reminder of the strength found in sharing our stories.

Example: In a blog post about starting a new career path, I shared the fears and excitement of stepping into the unknown. It’s a journey of self-discovery and embracing new challenges.

What Are the Key Features of Reflective Writing?

Reflective writing is characterized by several key features that distinguish it from other types of writing.

These features include personal insight, critical analysis, descriptive narrative, and a focus on personal growth.

- Personal Insight: Reflective writing is deeply personal, focusing on the writer’s internal thoughts, feelings, and reactions. It requires introspection and a willingness to explore one’s own experiences in depth.

- Critical Analysis: Beyond simply describing events, reflective writing involves analyzing these experiences. This means looking at the why and how, not just the what. It involves questioning, evaluating, and interpreting your experiences in relation to yourself, others, and the world.

- Descriptive Narrative: While reflective writing is analytical, it also includes descriptive elements. Vivid descriptions of experiences, thoughts, and feelings help to convey the depth of the reflection.

- Focus on Growth: A central aim of reflective writing is to foster personal or professional growth. It involves identifying lessons learned, recognizing patterns, and considering how to apply insights gained to future situations.

These features combine to make reflective writing a powerful tool for learning and development.

It’s a practice that encourages writers to engage deeply with their experiences, challenge their assumptions, and grow from their reflections.

What Is the Structure of Reflective Writing?

The structure of reflective writing can vary depending on the context and purpose, but it typically follows a general pattern that facilitates deep reflection.

A common structure includes an introduction, a body that outlines the experience and the reflection on it, and a conclusion.

- Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for the reflective piece. It briefly introduces the topic or experience being reflected upon and may include a thesis statement that outlines the main insight or theme of the reflection.

- Body: The body is where the bulk of the reflection takes place. It often follows a chronological order, detailing the experience before moving into the reflection. This section should explore the writer’s thoughts, feelings, reactions, and insights related to the experience. It’s also where critical analysis comes into play, examining causes, effects, and underlying principles.

- Conclusion: The conclusion wraps up the reflection, summarizing the key insights gained and considering how these learnings might apply to future situations. It’s an opportunity to reflect on personal growth and the broader implications of the experience.

This structure is flexible and can be adapted to suit different types of reflective writing.

However, the focus should always be on creating a coherent narrative that allows for deep personal insight and learning.

How Do You Start Reflective Writing?

Starting reflective writing can be challenging, as it requires diving into personal experiences and emotions.

Here are some tips to help initiate the reflective writing process:

- Choose a Focus: Start by selecting an experience or topic to reflect upon. It could be a specific event, a general period in your life, a project you worked on, or even a book that made a significant impact on you.

- Reflect on Your Feelings: Think about how the experience made you feel at the time and how you feel about it now. Understanding your emotional response is a crucial part of reflective writing.

- Ask Yourself Questions: Begin by asking yourself questions related to the experience. What did you learn from it? How did it challenge your assumptions? How has it influenced your thinking or behavior?

- Write a Strong Opening: Your first few sentences should grab the reader’s attention and clearly indicate what you will be reflecting on. You can start with a striking fact, a question, a quote, or a vivid description of a moment from the experience.

- Keep It Personal: Remember that reflective writing is personal. Use “I” statements to express your thoughts, feelings, and insights. This helps to maintain the focus on your personal experience and learning journey.

Here is a video about reflective writing that I think you’ll like:

Reflective Writing Toolkit

Finding the right tools and resources has been key to deepening my reflections and enhancing my self-awareness.

Here’s a curated toolkit that has empowered my own reflective practice:

- Journaling Apps: Apps like Day One or Reflectly provide structured formats for daily reflections, helping to capture thoughts and feelings on the go.

- Digital Notebooks: Tools like Evernote or Microsoft OneNote allow for organized, searchable reflections that can include text, images, and links.

- Writing Prompts: Websites like WritingPrompts.com offer endless ideas to spark reflective writing, making it easier to start when you’re feeling stuck.

- Mind Mapping Software: Platforms like MindMeister help organize thoughts visually, which can be especially helpful for reflective planning or brainstorming.

- Blogging Platforms: Sites like WordPress or Medium offer a space to share reflective writings publicly, fostering community and feedback. You’ll need a hosting platform. I recommend Bluehost or Hostarmada for beginners.

- Guided Meditation Apps: Apps such as Headspace or Calm can support reflective writing by clearing the mind and fostering a reflective state before writing.

- Audio Recording Apps: Tools like Otter.ai not only allow for verbal reflection but also transcribe conversations, which can then be reflected upon in writing.

- Time Management Apps: Resources like Forest or Pomodoro Technique apps help set dedicated time for reflection, making it a regular part of your routine.

- Creative Writing Software: Platforms like Scrivener cater to more in-depth reflective projects, providing extensive organizing and formatting options.

- Research Databases: Access to journals and articles through databases like Google Scholar can enrich reflective writing with theoretical frameworks and insights.

Final Thoughts: What Is Reflective Writing?

Reflective writing, at its core, is a deeply personal practice.

Yet, it also holds the potential to bridge cultural divides. By sharing reflective writings that explore personal experiences through the lens of different cultural backgrounds, we can foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of diverse worldviews.

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- Why Does Academic Writing Require Strict Formatting?

- What Is A Lens In Writing? (The Ultimate Guide)

- CORE CURRICULUM

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Literature, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Literature, 6-12" aria-label="Into Literature, 6-12"> Into Literature, 6-12

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Reading, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Reading, K-6" aria-label="Into Reading, K-6"> Into Reading, K-6

- INTERVENTION

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > English 3D, 4-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English 3D, 4-12" aria-label="English 3D, 4-12"> English 3D, 4-12

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > Read 180, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Read 180, 3-12" aria-label="Read 180, 3-12"> Read 180, 3-12

- SUPPLEMENTAL

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" aria-label="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12"> A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Amira Learning, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Amira Learning, K-6" aria-label="Amira Learning, K-6"> Amira Learning, K-6

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > JillE Literacy, K-3" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="JillE Literacy, K-3" aria-label="JillE Literacy, K-3"> JillE Literacy, K-3

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable, 3-12" aria-label="Writable, 3-12"> Writable, 3-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > ASSESSMENT" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ASSESSMENT" aria-label="ASSESSMENT"> ASSESSMENT

- CORE CURRICULUM

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" aria-label="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8"> Arriba las Matematicas, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Go Math!, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Go Math!, K-6" aria-label="Go Math!, K-6"> Go Math!, K-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" aria-label="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12"> Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Math, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Math, K-8" aria-label="Into Math, K-8"> Into Math, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math Expressions, PreK-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math Expressions, PreK-6" aria-label="Math Expressions, PreK-6"> Math Expressions, PreK-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math in Focus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math in Focus, K-8" aria-label="Math in Focus, K-8"> Math in Focus, K-8

- SUPPLEMENTAL

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- MATH > INTERVENTION > Math 180, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math 180, 3-12" aria-label="Math 180, 3-12"> Math 180, 3-12

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, K-5" aria-label="Into Science, K-5"> Into Science, K-5

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, 6-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, 6-8" aria-label="Into Science, 6-8"> Into Science, 6-8

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Science Dimensions, K-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science Dimensions, K-12" aria-label="Science Dimensions, K-12"> Science Dimensions, K-12

- SCIENCE > READERS > ScienceSaurus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ScienceSaurus, K-8" aria-label="ScienceSaurus, K-8"> ScienceSaurus, K-8

- SOCIAL STUDIES > CORE CURRICULUM > HMH Social Studies, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="HMH Social Studies, 6-12" aria-label="HMH Social Studies, 6-12"> HMH Social Studies, 6-12

- SOCIAL STUDIES > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable" aria-label="Writable"> Writable

- For Teachers

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Coachly" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Coachly" aria-label="Coachly"> Coachly

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Teacher's Corner" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Teacher's Corner" aria-label="Teacher's Corner"> Teacher's Corner

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Live Online Courses" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Live Online Courses" aria-label="Live Online Courses"> Live Online Courses

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Program-Aligned Courses" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Program-Aligned Courses" aria-label="Program-Aligned Courses"> Program-Aligned Courses

- For Leaders

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Leaders > The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- MORE > undefined > Assessment" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Assessment" aria-label="Assessment"> Assessment

- MORE > undefined > Early Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Early Learning" aria-label="Early Learning"> Early Learning

- MORE > undefined > English Language Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English Language Development" aria-label="English Language Development"> English Language Development

- MORE > undefined > Homeschool" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Homeschool" aria-label="Homeschool"> Homeschool

- MORE > undefined > Intervention" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Intervention" aria-label="Intervention"> Intervention

- MORE > undefined > Literacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Literacy" aria-label="Literacy"> Literacy

- MORE > undefined > Mathematics" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Mathematics" aria-label="Mathematics"> Mathematics

- MORE > undefined > Professional Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Professional Development" aria-label="Professional Development"> Professional Development

- MORE > undefined > Science" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science" aria-label="Science"> Science

- MORE > undefined > undefined" data-element-type="header nav submenu">

- MORE > undefined > Social and Emotional Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social and Emotional Learning" aria-label="Social and Emotional Learning"> Social and Emotional Learning

- MORE > undefined > Social Studies" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Studies" aria-label="Social Studies"> Social Studies

- MORE > undefined > Special Education" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Special Education" aria-label="Special Education"> Special Education

- MORE > undefined > Summer School" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Summer School" aria-label="Summer School"> Summer School

- BROWSE RESOURCES

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Classroom Activities" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classroom Activities" aria-label="Classroom Activities"> Classroom Activities

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Customer Success Stories" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Success Stories" aria-label="Customer Success Stories"> Customer Success Stories

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Digital Samples" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Digital Samples" aria-label="Digital Samples"> Digital Samples

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Events" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Events" aria-label="Events"> Events

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Grants & Funding" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Grants & Funding" aria-label="Grants & Funding"> Grants & Funding

- BROWSE RESOURCES > International" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="International" aria-label="International"> International

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Research Library" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Research Library" aria-label="Research Library"> Research Library

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Shaped - HMH Blog" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Shaped - HMH Blog" aria-label="Shaped - HMH Blog"> Shaped - HMH Blog

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Webinars" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Webinars" aria-label="Webinars"> Webinars

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Contact Sales" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Contact Sales" aria-label="Contact Sales"> Contact Sales

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" aria-label="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal"> Customer Service & Technical Support Portal

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Platform Login" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Platform Login" aria-label="Platform Login"> Platform Login

- Learn about us

- Learn about us > About" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="About" aria-label="About"> About

- Learn about us > Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" aria-label="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion"> Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Learn about us > Environmental, Social, and Governance" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Environmental, Social, and Governance" aria-label="Environmental, Social, and Governance"> Environmental, Social, and Governance

- Learn about us > News Announcements" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="News Announcements" aria-label="News Announcements"> News Announcements

- Learn about us > Our Legacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Our Legacy" aria-label="Our Legacy"> Our Legacy

- Learn about us > Social Responsibility" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Responsibility" aria-label="Social Responsibility"> Social Responsibility

- Learn about us > Supplier Diversity" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Supplier Diversity" aria-label="Supplier Diversity"> Supplier Diversity

- Join Us > Careers" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Careers" aria-label="Careers"> Careers

- Join Us > Educator Input Panel" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Educator Input Panel" aria-label="Educator Input Panel"> Educator Input Panel

- Join Us > Suppliers and Vendors" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Suppliers and Vendors" aria-label="Suppliers and Vendors"> Suppliers and Vendors

- Divisions > Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- Divisions > Heinemann" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Heinemann" aria-label="Heinemann"> Heinemann

- Divisions > NWEA" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="NWEA" aria-label="NWEA"> NWEA

- Platform Login

HMH Support is here to help you get back to school right. Get started

SOCIAL STUDIES

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Teaching Students How to Write a Reflective Narrative Essay

What Is a Reflective Narrative?

In The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin , Franklin reflects on different formative periods throughout his life. The literary work is divided into four parts: his childhood; his apprenticeship; his career and accomplishments as a printer, writer, and scientist; and a brief section about his civic involvements in Pennsylvania.

Franklin’s Autobiography is a historical example of a reflective narrative. A reflective narrative is a type of personal writing that allows writers to look back at incidents and changes in their lives. Writing a reflective narrative enables writers to not only recount experiences but also analyze how they’ve changed or learned lessons.

Reflective Narrative Essay Example

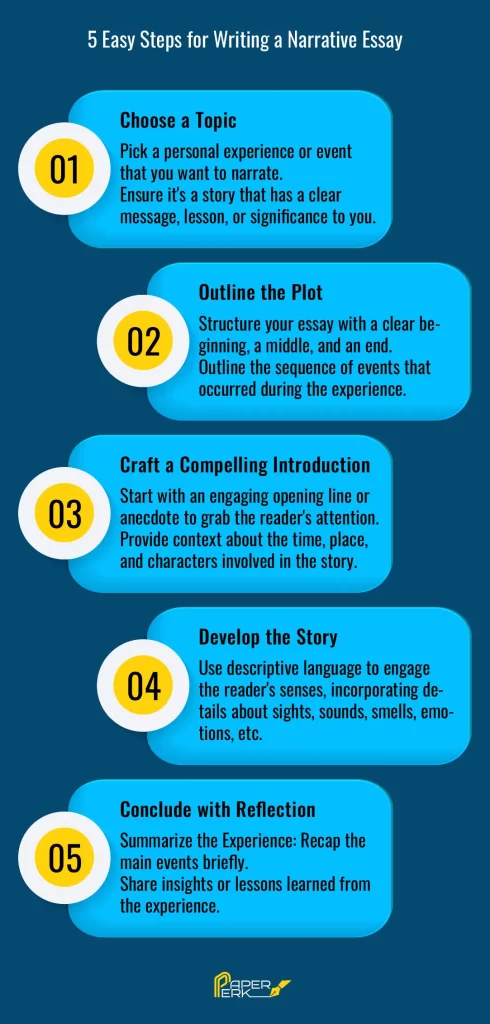

A reflective narrative essay consists of a beginning, middle, and ending. The beginning, or introduction, provides background and introduces the topic. The middle paragraphs provide details and events leading up to the change. Finally, the ending, or conclusion, sums up the writer’s reflection about the change.

The following is an excerpt from a reflective narrative essay written by a student entitled “Not Taken for Granted” (read the full essay in our “Reflective Narrative Guide” ). In the writing piece, the writer reflects on his changing relationship with his little brother:

I guess I was spoiled. At first, I was an only child, cuddled and cooed over by parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Up until I was eight years old, life was sweet. Then along came Grant, and everything changed.

Grant is my little brother. I don’t remember all the details, but he was born a month prematurely, so he needed a lot of extra attention, especially from Mom. My mom and dad didn’t ignore me, but I was no longer the center of their universe, and I resented the change in dynamics. And at first, I also resented Grant.

Fortunately, Grant’s early birth didn’t cause any real problems in his growth, and he crawled, toddled, and talked pretty much on schedule. My parents were still somewhat protective of him, but as he got older, he developed the obnoxious habit of attaching himself to me, following my every move. My parents warned me to be nice to him, but I found him totally annoying. By the time I became a teenager, he was, at five, my shadow, following me around, copying my every move, asking questions, and generally being a pest.

Steps to Writing a Reflective Narrative Essay

How can Grades 3 and up students write a reflective narrative essay consisting of an engaging introduction, supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion that sums up the essay? Have your students follow these seven steps:

1. Select a Topic

The first step in prewriting is for students to select a topic. There is plenty for them to choose from, including life-altering events (such as a new experience or failing or succeeding at a new task or activity) or people or moments that made an impact and caused a change in your students’ lives (a teacher or a trip to a new city or country). Another way students can choose their topics is to think of ways they have changed and explore the reasons for those changes.

A Then/Now Chart can help students brainstorm changes in their lives. In this chart, they should list how things used to be and how they are now. Afterward, they’ll write why they changed. After brainstorming various changes, students can mark the one change they wish to write about. See below for an example of this type of chart:

| Now | ||

|---|---|---|

2. Gather Relevant Details

After your students choose their topic, they must gather details that’ll help them outline their essay. A T-Chart is a tool that can help collect those details about their lives before and after the change took place.

3. Organize Details

The last step in prewriting consists of your students organizing the details of their essays. A reflective narrative may cover an extended period, so students should choose details that demonstrate their lives before, during, and after the change. A third tool students can use to help plot the narrative is a Time Line , where they focus on the background (before the change), realization (during the change), and finally, reflection (after the change).

4. Write the First Draft

Now, it’s time for your students to write their first drafts. The tools they used to brainstorm will come in handy! However, though their notes should guide them, they should remain open to any new ideas they may have during this writing step. Their essays should consist of a beginning, middle, and ending. The beginning, or introduction paragraph, provides background details and events that help build the narrative and lead to the change.

The middle, or body paragraphs, should include an anecdote that helps demonstrate the change. Your students should remember to show readers what is happening and use dialogue. Finally, the ending, or conclusion paragraph, should reflect on events after the change.

Allow your students to write freely—they shouldn’t worry too much about spelling and grammar. Freewriting consists of 5–10 minutes of writing as much as possible. For more information on freewriting, check out our lesson !

5. Revise and Improve Draft

Revising allows students to think about what they wrote and ways they can improve their drafts. When revising, students should check for: ideas, organization, voice, word choice, and sentence fluency . Here’s a list of questions they can ask themselves when reading their drafts:

- Is the topic interesting?

- Are there enough details and events to support the topic?

Organization

- Does the beginning provide background and introduce the topic?

- Do the middle paragraphs show how I changed?

- Does the ending reflect on how my life was altered by this experience?

- Do I sound interested in the topic?

- Does the dialogue sound natural?

Word Choice

- Have I used specific nouns and vivid verbs?

- Have I used descriptive modifiers?

Sentence Fluency

- Do the sentences read smoothly?

- Have I varied the lengths and beginnings of my sentences?

After identifying the parts of their drafts that need reworking, students should make another draft.

6. Edit as Needed

After revising their drafts, students should edit for conventions (spelling, capitalization, grammar, clarity, and punctuation errors). They could even exchange essays with one another to check each other’s work. Finally, after editing, they’ll have a final copy to proofread for any minor errors they or the other student might’ve missed.

7. Share with an Audience

Writing a reflective narrative essay is a meaningful way for students to reflect on their lives. Additionally, their writing pieces could help others understand more about them. Therefore, consider having your students share their essays. They could publish their writing pieces by making a class eBook or submitting them to relevant writing contests. Or students can read them aloud to their classmates or family members.

More Reflective Narrative Essay Writing Tips

Essay writing can be challenging as it requires proper brainstorming, organization, and creativity. That’s why it’s great for students to have writing guides to aid them in the writing process. This downloadable PDF handout for students provides tips for how to write a reflective narrative essay.

Try Writable to support your ELA curriculum, district benchmarks, and state standards with more than 600 fully customizable writing assignments and rubrics for students in Grades 3–12. Learn more .

- Grades 9-12

Related Reading

Why Is Writing Important for Students?

Shaped Contributor

August 19, 2024

11 Classroom Community-Building Activities for Elementary Students

Brenda Iasevoli Shaped Executive Editor

August 16, 2024

What Teachers Really Think about the Science of Reading and the Role of AI in Education

NWEA VP, Content Advocacy-Literacy, HMH

August 8, 2024

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Storyteller's Sale

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Critique Report

- Writing Reports

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Telling the Story of Yourself: 6 Steps to Writing Personal Narratives

By Jennifer Xue

Table of Contents

Why do we write personal narratives, 6 guidelines for writing personal narrative essays, inspiring personal narratives, examples of personal narrative essays, tell your story.

First off, you might be wondering: what is a personal narrative? In short, personal narratives are stories we tell about ourselves that focus on our growth, lessons learned, and reflections on our experiences.

From stories about inspirational figures we heard as children to any essay, article, or exercise where we're asked to express opinions on a situation, thing, or individual—personal narratives are everywhere.

According to Psychology Today, personal narratives allow authors to feel and release pains, while savouring moments of strength and resilience. Such emotions provide an avenue for both authors and readers to connect while supporting healing in the process.

That all sounds great. But when it comes to putting the words down on paper, we often end up with a list of experiences and no real structure to tie them together.

In this article, we'll discuss what a personal narrative essay is further, learn the 6 steps to writing one, and look at some examples of great personal narratives.

As readers, we're fascinated by memoirs, autobiographies, and long-form personal narrative articles, as they provide a glimpse into the authors' thought processes, ideas, and feelings. But you don't have to be writing your whole life story to create a personal narrative.

You might be a student writing an admissions essay , or be trying to tell your professional story in a cover letter. Regardless of your purpose, your narrative will focus on personal growth, reflections, and lessons.

Personal narratives help us connect with other people's stories due to their easy-to-digest format and because humans are empathising creatures.

We can better understand how others feel and think when we were told stories that allow us to see the world from their perspectives. The author's "I think" and "I feel" instantaneously become ours, as the brain doesn't know whether what we read is real or imaginary.

In her best-selling book Wired for Story, Lisa Cron explains that the human brain craves tales as it's hard-wired through evolution to learn what happens next. Since the brain doesn't know whether what you are reading is actual or not, we can register the moral of the story cognitively and affectively.

In academia, a narrative essay tells a story which is experiential, anecdotal, or personal. It allows the author to creatively express their thoughts, feelings, ideas, and opinions. Its length can be anywhere from a few paragraphs to hundreds of pages.

Outside of academia, personal narratives are known as a form of journalism or non-fiction works called "narrative journalism." Even highly prestigious publications like the New York Times and Time magazine have sections dedicated to personal narratives. The New Yorke is a magazine dedicated solely to this genre.

The New York Times holds personal narrative essay contests. The winners are selected because they:

had a clear narrative arc with a conflict and a main character who changed in some way. They artfully balanced the action of the story with reflection on what it meant to the writer. They took risks, like including dialogue or playing with punctuation, sentence structure and word choice to develop a strong voice. And, perhaps most important, they focused on a specific moment or theme – a conversation, a trip to the mall, a speech tournament, a hospital visit – instead of trying to sum up the writer’s life in 600 words.

In a nutshell, a personal narrative can cover any reflective and contemplative subject with a strong voice and a unique perspective, including uncommon private values. It's written in first person and the story encompasses a specific moment in time worthy of a discussion.

Writing a personal narrative essay involves both objectivity and subjectivity. You'll need to be objective enough to recognise the importance of an event or a situation to explore and write about. On the other hand, you must be subjective enough to inject private thoughts and feelings to make your point.

With personal narratives, you are both the muse and the creator – you have control over how your story is told. However, like any other type of writing, it comes with guidelines.

1. Write Your Personal Narrative as a Story

As a story, it must include an introduction, characters, plot, setting, climax, anti-climax (if any), and conclusion. Another way to approach it is by structuring it with an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should set the tone, while the body should focus on the key point(s) you want to get across. The conclusion can tell the reader what lessons you have learned from the story you've just told.

2. Give Your Personal Narrative a Clear Purpose

Your narrative essay should reflect your unique perspective on life. This is a lot harder than it sounds. You need to establish your perspective, the key things you want your reader to take away, and your tone of voice. It's a good idea to have a set purpose in mind for the narrative before you start writing.

Let's say you want to write about how you manage depression without taking any medicine. This could go in any number of ways, but isolating a purpose will help you focus your writing and choose which stories to tell. Are you advocating for a holistic approach, or do you want to describe your emotional experience for people thinking of trying it?

Having this focus will allow you to put your own unique take on what you did (and didn't do, if applicable), what changed you, and the lessons learned along the way.

3. Show, Don't Tell

It's a narration, so the narrative should show readers what happened, instead of telling them. As well as being a storyteller, the author should take part as one of the characters. Keep this in mind when writing, as the way you shape your perspective can have a big impact on how your reader sees your overarching plot. Don't slip into just explaining everything that happened because it happened to you. Show your reader with action.

You can check for instances of telling rather than showing with ProWritingAid. For example, instead of:

"You never let me do anything!" I cried disdainfully.

"You never let me do anything!" To this day, my mother swears that the glare I levelled at her as I spat those words out could have soured milk.

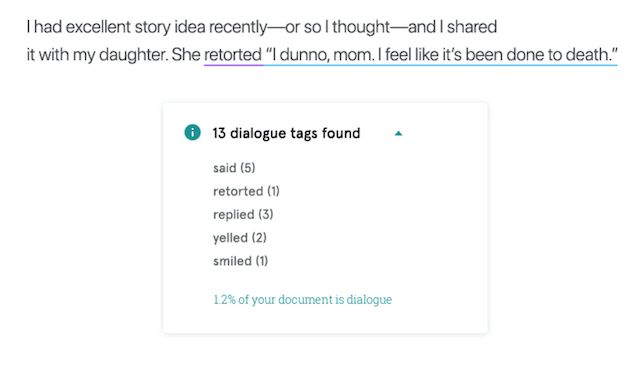

Using ProWritingAid will help you find these instances in your manuscript and edit them without spending hours trawling through your work yourself.

4. Use "I," But Don't Overuse It

You, the author, take ownership of the story, so the first person pronoun "I" is used throughout. However, you shouldn't overuse it, as it'd make it sound too self-centred and redundant.

ProWritingAid can also help you here – the Style Report will tell you if you've started too many sentences with "I", and show you how to introduce more variation in your writing.

5. Pay Attention to Tenses

Tense is key to understanding. Personal narratives mostly tell the story of events that happened in the past, so many authors choose to use the past tense. This helps separate out your current, narrating voice and your past self who you are narrating. If you're writing in the present tense, make sure that you keep it consistent throughout.

6. Make Your Conclusion Satisfying

Satisfy your readers by giving them an unforgettable closing scene. The body of the narration should build up the plot to climax. This doesn't have to be something incredible or shocking, just something that helps give an interesting take on your story.

The takeaways or the lessons learned should be written without lecturing. Whenever possible, continue to show rather than tell. Don't say what you learned, narrate what you do differently now. This will help the moral of your story shine through without being too preachy.

GoodReads is a great starting point for selecting read-worthy personal narrative books. Here are five of my favourites.

Owl Moon by Jane Yolen

Jane Yolen, the author of 386 books, wrote this poetic story about a daughter and her father who went owling. Instead of learning about owls, Yolen invites readers to contemplate the meaning of gentleness and hope.

Night by Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel was a teenager when he and his family were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944. This Holocaust memoir has a strong message that such horrific events should never be repeated.

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

This classic is a must-read by young and old alike. It's a remarkable diary by a 13-year-old Jewish girl who hid inside a secret annexe of an old building during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1942.

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

This is a personal narrative written by a brave author renowned for her clarity, passion, and honesty. Didion shares how in December 2003, she lost her husband of 40 years to a massive heart attack and dealt with the acute illness of her only daughter. She speaks about grief, memories, illness, and hope.

Educated by Tara Westover

Author Tara Westover was raised by survivalist parents. She didn't go to school until 17 years of age, which later took her to Harvard and Cambridge. It's a story about the struggle for quest for knowledge and self-reinvention.

Narrative and personal narrative journalism are gaining more popularity these days. You can find distinguished personal narratives all over the web.

Curating the best of the best of personal narratives and narrative essays from all over the web. Some are award-winning articles.

Narratively

Long-form writing to celebrate humanity through storytelling. It publishes personal narrative essays written to provoke, inspire, and reflect, touching lesser-known and overlooked subjects.

Narrative Magazine

It publishes non,fiction narratives, poetry, and fiction. Among its contributors is Frank Conroy, the author of Stop-Time , a memoir that has never been out of print since 1967.

Thought Catalog

Aimed at Generation Z, it publishes personal narrative essays on self-improvement, family, friendship, romance, and others.

Personal narratives will continue to be popular as our brains are wired for stories. We love reading about others and telling stories of ourselves, as they bring satisfaction and a better understanding of the world around us.

Personal narratives make us better humans. Enjoy telling yours!

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Jennifer Xue

Jennifer Xue is an award-winning e-book author with 2,500+ articles and 100+ e-books/reports published under her belt. She also taught 50+ college-level essay and paper writing classes. Her byline has appeared in Forbes, Fortune, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Business.com, Business2Community, Addicted2Success, Good Men Project, and others. Her blog is JenniferXue.com. Follow her on Twitter @jenxuewrites].

Get started with ProWritingAid

It's A Steal

Bring your story to life for less. Get 25% off yearly plans in our Storyteller's Sale. Grab the discount while it lasts.

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Narration: Writing to Reflect

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Narration is one of the most common types of communication in our world. It seems we are either telling about something we did or hearing about something that happened to others on an almost hourly basis. This constant practice makes narrative writing--also called reflective writing--natural for us and a common writing assignment in school.

It seemed only logical that we ask a successful student to reflect upon and narrate her experience with narrative writing.

Meet Kris Nelson

Kris is a typical adult student: returning to school to complete degree work while holding down a job and raising a family. Her approach to this writing assignment was meticulous and thorough. Her description of the writing process, from pre-writing to final draft, also provides an excellent model for both beginning and experienced writers.

What follows is Kris' answers during an interview in which we asked how she went about producing an effective narrative or reflective essay.

How Did You Begin?

The first thing I did was to review the assignment instructions and make sure I understood everything my professor wanted. Then I looked up a definition of a narrative or reflection essay. The definition I liked was simple: an essay that shares a significant personal discovery . The discovery could be about anything—something you found out about yourself, about other people, even the world. In reflection writing you tell a story. Everybody loves a good story. Once I put those two things together--a good story about finding out something—the assignment came together for me.

I also tried to find a way to relate the assignment to the real world. I thought about how often I use narrative writing in the real world. I work in the medical field and we have to write patient histories that tell a story about that patient, including their presenting complaints, the doctor's treatment, the patient outcomes, and follow-ups. Sometimes we've been in legal depositions where we had to narrate our version of what happened in a certain patient's case. Knowing that I was practicing a skill that I needed at work gave me more motivation.

How Is a Reflection/Narration Organized?

There are usually five parts in this type of essay. First the introduction . You set the scene, but with a little mystery or something exciting or spicy to make it interesting. Next is conflict . There has to be some complication. Some drama, problem to be solved, or decision to be made. Then you present the effects of the problem or conflict. What happened? This is where the reader’s interest is usually most intense. Finally, the problem is over. There’s a solution . That’s why this section is usually called the resolution. Many reflections also have a conclusion. This part reinforces the point and circles back to the beginning, closing the loop, so to speak.

Describe Your Writing Process

I try to follow pretty much the same process, no matter what I'm writing. Sometimes there is stronger emphasis in one area because of the type of writing. In this narrative essay, for example, I really relied on my outline.

- Prewriting : I start with a list of possible topics. I brainstorm them as fast as I can and do not worry about what is coming out. I want quantity, not quality. Then I pick one or two to play with. I brainstorm about it. For this topic, I tried to remember as much as I could about the summer of the infamous cookie dough incident.

- Outlining : After the topic is set, I outline. I’m a big believer in outlines. My motto is: If I can outline it, I can write it . The writing just seems to take care of itself with a good outline. On one side of the page I put the five parts— intro, complication, effects, resolution and conclusion . Then I filled in each part with as much detail as I could as fast as I could. I ended up with more detail than I needed, but that’s a great position to be in! Then I did a last outline, the one I try to follow when writing.

- Drafting : On a first draft, I write fast and don’t worry about anything except getting down my thoughts. I stick to the outline, but if I need to go in a different direction I will. It’s just a draft.

- Revising : After the first draft, I go back and throw out anything that takes away from my point or the effect I’m going for. Then I find somebody else to read it and give me their reactions. That really helps me to understand how well I communicated the ideas and feelings I wanted to get across, what belongs and what doesn't.

- Editing/Proofing : On the final draft, I edit and proofread. I like to use the spelling and grammar checker on my computer, then get someone else to look it over again for errors. For this essay, I felt like my cousins and my grandmother deserved my best writing so I really tried to make it shine.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- What Is an Internship? Everything You Should Know

How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

- How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

- Best Colours for Your PowerPoint Presentation: How to Choose

- How to Write a Nursing Essay

- Top 5 Essential Skills You Should Build As An International Student

- How Professional Editing Services Can Take Your Writing to the Next Level

- How to Write an Effective Essay Outline

- How to Write a Law Essay: A Comprehensive Guide with Examples

- What Are the Limitations of ChatGPT?

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

A complete guide to writing a reflective essay

(Last updated: 3 June 2024)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

“The overwhelming burden of writing my first ever reflective essay loomed over me as I sat as still as a statue, as my fingers nervously poised over the intimidating buttons on my laptop keyboard. Where would I begin? Where would I end? Nerve wracking thoughts filled my mind as I fretted over the seemingly impossible journey on which I was about to embark.”

Reflective essays may seem simple on the surface, but they can be a real stumbling block if you're not quite sure how to go about them. In simple terms, reflective essays constitute a critical examination of a life experience and, with the right guidance, they're not too challenging to put together. A reflective essay is similar to other essays in that it needs to be easily understood and well structured, but the content is more akin to something personal like a diary entry.

In this guide, we explore in detail how to write a great reflective essay , including what makes a good structure and some advice on the writing process. We’ve even thrown in an example reflective essay to inspire you too, making this the ultimate guide for anyone needing reflective essay help.

Types of Reflection Papers

There are several types of reflective papers, each serving a unique purpose. Educational reflection papers focus on your learning experiences, such as a course or a lecture, and how they have impacted your understanding. Professional reflection papers often relate to work experiences, discussing what you have learned in a professional setting and how it has shaped your skills and perspectives. Personal reflection papers delve into personal experiences and their influence on your personal growth and development.

Each of these requires a slightly different approach, but all aim to provide insight into your thoughts and experiences, demonstrating your ability to analyse and learn from them. Understanding the specific requirements of each type can help you tailor your writing to effectively convey your reflections.

Reflective Essay Format

In a reflective essay, a writer primarily examines his or her life experiences, hence the term ‘reflective’. The purpose of writing a reflective essay is to provide a platform for the author to not only recount a particular life experience, but to also explore how he or she has changed or learned from those experiences. Reflective writing can be presented in various formats, but you’ll most often see it in a learning log format or diary entry. Diary entries in particular are used to convey how the author’s thoughts have developed and evolved over the course of a particular period.

The format of a reflective essay may change depending on the target audience. Reflective essays can be academic, or may feature more broadly as a part of a general piece of writing for a magazine, for instance. For class assignments, while the presentation format can vary, the purpose generally remains the same: tutors aim to inspire students to think deeply and critically about a particular learning experience or set of experiences. Here are some typical examples of reflective essay formats that you may have to write:

A focus on personal growth:

A type of reflective essay often used by tutors as a strategy for helping students to learn how to analyse their personal life experiences to promote emotional growth and development. The essay gives the student a better understanding of both themselves and their behaviours.

A focus on the literature:

This kind of essay requires students to provide a summary of the literature, after which it is applied to the student’s own life experiences.

Pre-Writing Tips: How to Start Writing the Reflection Essay?

As you go about deciding on the content of your essay, you need to keep in mind that a reflective essay is highly personal and aimed at engaging the reader or target audience. And there’s much more to a reflective essay than just recounting a story. You need to be able to reflect (more on this later) on your experience by showing how it influenced your subsequent behaviours and how your life has been particularly changed as a result.

As a starting point, you might want to think about some important experiences in your life that have really impacted you, either positively, negatively, or both. Some typical reflection essay topics include: a real-life experience, an imagined experience, a special object or place, a person who had an influence on you, or something you have watched or read. If you are writing a reflective essay as part of an academic exercise, chances are your tutor will ask you to focus on a particular episode – such as a time when you had to make an important decision – and reflect on what the outcomes were. Note also, that the aftermath of the experience is especially important in a reflective essay; miss this out and you will simply be storytelling.

What Do You Mean By Reflection Essay?

It sounds obvious, but the reflective process forms the core of writing this type of essay, so it’s important you get it right from the outset. You need to really think about how the personal experience you have chosen to focus on impacted or changed you. Use your memories and feelings of the experience to determine the implications for you on a personal level.

Once you’ve chosen the topic of your essay, it’s really important you study it thoroughly and spend a lot of time trying to think about it vividly. Write down everything you can remember about it, describing it as clearly and fully as you can. Keep your five senses in mind as you do this, and be sure to use adjectives to describe your experience. At this stage, you can simply make notes using short phrases, but you need to ensure that you’re recording your responses, perceptions, and your experience of the event(s).

Once you’ve successfully emptied the contents of your memory, you need to start reflecting. A great way to do this is to pick out some reflection questions which will help you think deeper about the impact and lasting effects of your experience. Here are some useful questions that you can consider:

- What have you learned about yourself as a result of the experience?

- Have you developed because of it? How?

- Did it have any positive or negative bearing on your life?

- Looking back, what would you have done differently?

- Why do you think you made the particular choices that you did? Do you think these were the right choices?

- What are your thoughts on the experience in general? Was it a useful learning experience? What specific skills or perspectives did you acquire as a result?

These signpost questions should help kick-start your reflective process. Remember, asking yourself lots of questions is key to ensuring that you think deeply and critically about your experiences – a skill that is at the heart of writing a great reflective essay.

Consider using models of reflection (like the Gibbs or Kolb cycles) before, during, and after the learning process to ensure that you maintain a high standard of analysis. For example, before you really get stuck into the process, consider questions such as: what might happen (regarding the experience)? Are there any possible challenges to keep in mind? What knowledge is needed to be best prepared to approach the experience? Then, as you’re planning and writing, these questions may be useful: what is happening within the learning process? Is the process working out as expected? Am I dealing with the accompanying challenges successfully? Is there anything that needs to be done additionally to ensure that the learning process is successful? What am I learning from this? By adopting such a framework, you’ll be ensuring that you are keeping tabs on the reflective process that should underpin your work.

How to Strategically Plan Out the Reflective Essay Structure?

Here’s a very useful tip: although you may feel well prepared with all that time spent reflecting in your arsenal, do not, start writing your essay until you have worked out a comprehensive, well-rounded plan . Your writing will be so much more coherent, your ideas conveyed with structure and clarity, and your essay will likely achieve higher marks.

This is an especially important step when you’re tackling a reflective essay – there can be a tendency for people to get a little ‘lost’ or disorganised as they recount their life experiences in an erratic and often unsystematic manner as it is a topic so close to their hearts. But if you develop a thorough outline (this is the same as a ‘plan’) and ensure you stick to it like Christopher Columbus to a map, you should do just fine as you embark on the ultimate step of writing your essay. If you need further convincing on how important planning is, we’ve summarised the key benefits of creating a detailed essay outline below:

An outline allows you to establish the basic details that you plan to incorporate into your paper – this is great for helping you pick out any superfluous information, which can be removed entirely to make your essay succinct and to the point.

Think of the outline as a map – you plan in advance the points you wish to navigate through and discuss in your writing. Your work will more likely have a clear through line of thought, making it easier for the reader to understand. It’ll also help you avoid missing out any key information, and having to go back at the end and try to fit it in.

It’s a real time-saver! Because the outline essentially serves as the essay’s ‘skeleton’, you’ll save a tremendous amount of time when writing as you’ll be really familiar with what you want to say. As such, you’ll be able to allocate more time to editing the paper and ensuring it’s of a high standard.

Now you’re familiar with the benefits of using an outline for your reflective essay, it is essential that you know how to craft one. It can be considerably different from other typical essay outlines, mostly because of the varying subjects. But what remains the same, is that you need to start your outline by drafting the introduction, body and conclusion. More on this below.

Introduction

As is the case with all essays, your reflective essay must begin within an introduction that contains both a hook and a thesis statement. The point of having a ‘hook’ is to grab the attention of your audience or reader from the very beginning. You must portray the exciting aspects of your story in the initial paragraph so that you stand the best chances of holding your reader’s interest. Refer back to the opening quote of this article – did it grab your attention and encourage you to read more? The thesis statement is a brief summary of the focus of the essay, which in this case is a particular experience that influenced you significantly. Remember to give a quick overview of your experience – don’t give too much information away or you risk your reader becoming disinterested.

Next up is planning the body of your essay. This can be the hardest part of the entire paper; it’s easy to waffle and repeat yourself both in the plan and in the actual writing. Have you ever tried recounting a story to a friend only for them to tell you to ‘cut the long story short’? They key here is to put plenty of time and effort into planning the body, and you can draw on the following tips to help you do this well:

Try adopting a chronological approach. This means working through everything you want to touch upon as it happened in time. This kind of approach will ensure that your work is systematic and coherent. Keep in mind that a reflective essay doesn’t necessarily have to be linear, but working chronologically will prevent you from providing a haphazard recollection of your experience. Lay out the important elements of your experience in a timeline – this will then help you clearly see how to piece your narrative together.

Ensure the body of your reflective essay is well focused and contains appropriate critique and reflection. The body should not only summarise your experience, it should explore the impact that the experience has had on your life, as well as the lessons that you have learned as a result. The emphasis should generally be on reflection as opposed to summation. A reflective posture will not only provide readers with insight on your experience, it’ll highlight your personality and your ability to deal with or adapt to particular situations.

In the conclusion of your reflective essay, you should focus on bringing your piece together by providing a summary of both the points made throughout, and what you have learned as a result. Try to include a few points on why and how your attitudes and behaviours have been changed. Consider also how your character and skills have been affected, for example: what conclusions can be drawn about your problem-solving skills? What can be concluded about your approach to specific situations? What might you do differently in similar situations in the future? What steps have you taken to consolidate everything that you have learned from your experience? Keep in mind that your tutor will be looking out for evidence of reflection at a very high standard.

Congratulations – you now have the tools to create a thorough and accurate plan which should put you in good stead for the ultimate phase indeed of any essay, the writing process.

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Your Reflective Essay

As with all written assignments, sitting down to put pen to paper (or more likely fingers to keyboard) can be daunting. But if you have put in the time and effort fleshing out a thorough plan, you should be well prepared, which will make the writing process as smooth as possible. The following points should also help ease the writing process:

- To get a feel for the tone and format in which your writing should be, read other typically reflective pieces in magazines and newspapers, for instance.

- Don’t think too much about how to start your first sentence or paragraph; just start writing and you can always come back later to edit anything you’re not keen on. Your first draft won’t necessarily be your best essay writing work but it’s important to remember that the earlier you start writing, the more time you will have to keep reworking your paper until it’s perfect. Don’t shy away from using a free-flow method, writing and recording your thoughts and feelings on your experiences as and when they come to mind. But make sure you stick to your plan. Your plan is your roadmap which will ensure your writing doesn’t meander too far off course.

- For every point you make about an experience or event, support it by describing how you were directly impacted, using specific as opposed to vague words to convey exactly how you felt.

- Write using the first-person narrative, ensuring that the tone of your essay is very personal and reflective of your character.

- If you need to, refer back to our notes earlier on creating an outline. As you work through your essay, present your thoughts systematically, remembering to focus on your key learning outcomes.

- Consider starting your introduction with a short anecdote or quote to grasp your readers’ attention, or other engaging techniques such as flashbacks.

- Choose your vocabulary carefully to properly convey your feelings and emotions. Remember that reflective writing has a descriptive component and so must have a wide range of adjectives to draw from. Avoid vague adjectives such as ‘okay’ or ‘nice’ as they don’t really offer much insight into your feelings and personality. Be more specific – this will make your writing more engaging.

- Be honest with your feelings and opinions. Remember that this is a reflective task, and is the one place you can freely admit – without any repercussions – that you failed at a particular task. When assessing your essay, your tutor will expect a deep level of reflection, not a simple review of your experiences and emotion. Showing deep reflection requires you to move beyond the descriptive. Be extremely critical about your experience and your response to it. In your evaluation and analysis, ensure that you make value judgements, incorporating ideas from outside the experience you had to guide your analysis. Remember that you can be honest about your feelings without writing in a direct way. Use words that work for you and are aligned with your personality.

- Once you’ve finished learning about and reflecting on your experience, consider asking yourself these questions: what did I particularly value from the experience and why? Looking back, how successful has the process been? Think about your opinions immediately after the experience and how they differ now, so that you can evaluate the difference between your immediate and current perceptions. Asking yourself such questions will help you achieve reflective writing effectively and efficiently.

- Don’t shy away from using a variety of punctuation. It helps keeps your writing dynamic! Doesn’t it?

- If you really want to awaken your reader’s imagination, you can use imagery to create a vivid picture of your experiences.

- Ensure that you highlight your turning point, or what we like to call your “Aha!” moment. Without this moment, your resulting feelings and thoughts aren’t as valid and your argument not as strong.

- Don’t forget to keep reiterating the lessons you have learned from your experience.

Bonus Tip - Using Wider Sources

Although a reflective piece of writing is focused on personal experience, it’s important you draw on other sources to demonstrate your understanding of your experience from a theoretical perspective. It’ll show a level of analysis – and a standard of reliability in what you’re claiming – if you’re also able to validate your work against other perspectives that you find. Think about possible sources, like newspapers, surveys, books and even journal articles. Generally, the additional sources you decide to include in your work are highly dependent on your field of study. Analysing a wide range of sources, will show that you have read widely on your subject area, that you have nuanced insight into the available literature on the subject of your essay, and that you have considered the broader implications of the literature for your essay. The incorporation of other sources into your essay also helps to show that you are aware of the multi-dimensional nature of both the learning and problem-solving process.

Reflective Essay Example

If you want some inspiration for writing, take a look at our example of a short reflective essay , which can serve as a useful starting point for you when you set out to write your own.

Some Final Notes to Remember

To recap, the key to writing a reflective essay is demonstrating what lessons you have taken away from your experiences, and why and how you have been shaped by these lessons.

The reflective thinking process begins with you – you must consciously make an effort to identify and examine your own thoughts in relation to a particular experience. Don’t hesitate to explore any prior knowledge or experience of the topic, which will help you identify why you have formed certain opinions on the subject. Remember that central to reflective essay writing is the examination of your attitudes, assumptions and values, so be upfront about how you feel. Reflective writing can be quite therapeutic, helping you identify and clarify your strengths and weaknesses, particularly in terms of any knowledge gaps that you may have. It’s a pretty good way of improving your critical thinking skills, too. It enables you to adopt an introspective posture in analysing your experiences and how you learn/make sense of them.

If you are still having difficulties with starting the writing process, why not try mind-mapping which will help you to structure your thinking and ideas, enabling you to produce a coherent piece. Creating a mind map will ensure that your argument is written in a very systematic way that will be easy for your tutor to follow. Here’s a recap of the contents of this article, which also serves as a way to create a mind map:

1. Identify the topic you will be writing on.

2. Note down any ideas that are related to the topic and if you want to, try drawing a diagram to link together any topics, theories, and ideas.

3. Allow your ideas to flow freely, knowing that you will always have time to edit your reflective essay .

4. Consider how your ideas are connected to each other, then begin the writing process.

And finally, keep in mind that although there are descriptive elements in a reflective essay, we can’t emphasise enough how crucial it is that your work is critical, analytical, and adopts a reflective posture in terms of your experience and the lessons you have learned from it.

Essay exams: how to answer ‘To what extent…’

How to write a master’s essay.

- essay writing

- reflective essays

- study skills

- writing a good essay

- writing tips

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

- Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- How it works

- Frequently asked questions

- Essay Writing Services

- Dissertation writing services

- Dissertation chapter

- Primary research

- Law services

- PhD writing services

- Urgent Deadlines Service

- Referral Welcome

- Download PDF Example

- Welcome to Our Blog

- Become a writer

- Fair use policy

- Student Policy England

- Terms and conditions

- Promotion Terms and Conditions

- Privacy policy

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

The Ultimate Narrative Essay Guide for Beginners

A narrative essay tells a story in chronological order, with an introduction that introduces the characters and sets the scene. Then a series of events leads to a climax or turning point, and finally a resolution or reflection on the experience.

Speaking of which, are you in sixes and sevens about narrative essays? Don’t worry this ultimate expert guide will wipe out all your doubts. So let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Everything You Need to Know About Narrative Essay

What is a narrative essay.

When you go through a narrative essay definition, you would know that a narrative essay purpose is to tell a story. It’s all about sharing an experience or event and is different from other types of essays because it’s more focused on how the event made you feel or what you learned from it, rather than just presenting facts or an argument. Let’s explore more details on this interesting write-up and get to know how to write a narrative essay.

Elements of a Narrative Essay

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements of a narrative essay:

A narrative essay has a beginning, middle, and end. It builds up tension and excitement and then wraps things up in a neat package.

Real people, including the writer, often feature in personal narratives. Details of the characters and their thoughts, feelings, and actions can help readers to relate to the tale.

It’s really important to know when and where something happened so we can get a good idea of the context. Going into detail about what it looks like helps the reader to really feel like they’re part of the story.

Conflict or Challenge