Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

97k Accesses

44 Citations

71 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

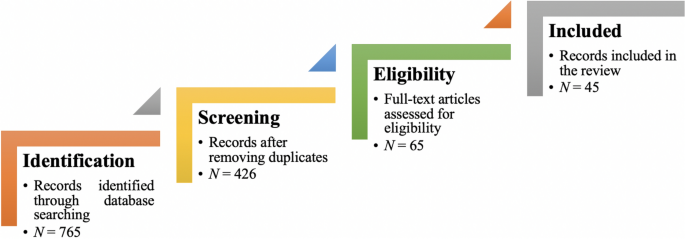

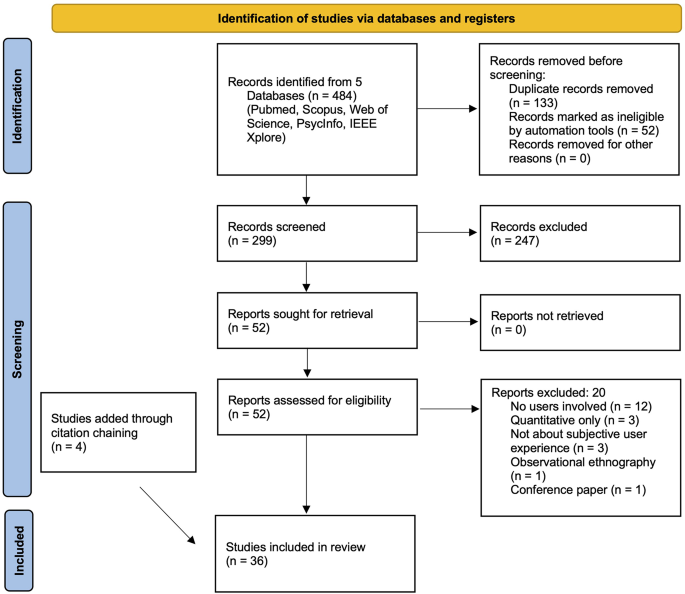

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

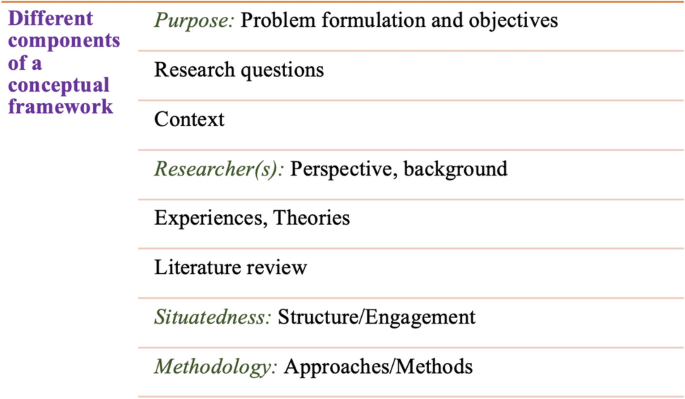

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

768k Accesses

348 Citations

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

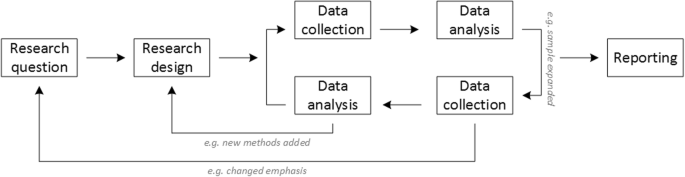

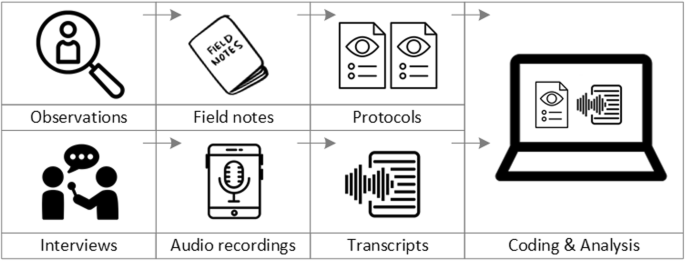

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

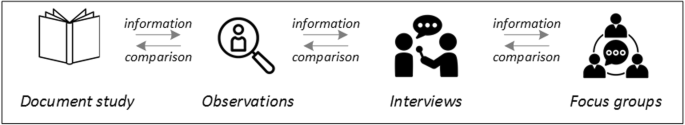

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

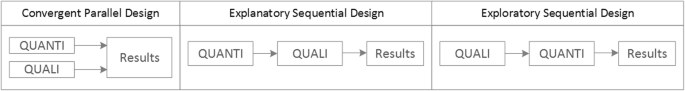

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]