PhD students’ mental health is poor and the pandemic made it worse – but there are coping strategies that can help

Senior Lecturer in Technology Enhanced Learning, The Open University

Assistant Professor in Strategy and Entrepreneurship, UCL

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University College London and The Open University provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A pre-pandemic study on PhD students’ mental health showed that they often struggle with such issues. Financial insecurity and feelings of isolation can be among the factors affecting students’ wellbeing.

The pandemic made the situation worse. We carried out research that looked into the impact of the pandemic on PhD students, surveying 1,780 students in summer 2020. We asked them about their mental health, the methods they used to cope and their satisfaction with their progress in their doctoral study.

Unsurprisingly, the lockdown in summer 2020 affected the ability to study for many. We found that 86% of the UK PhD students we surveyed reported a negative impact on their research progress.

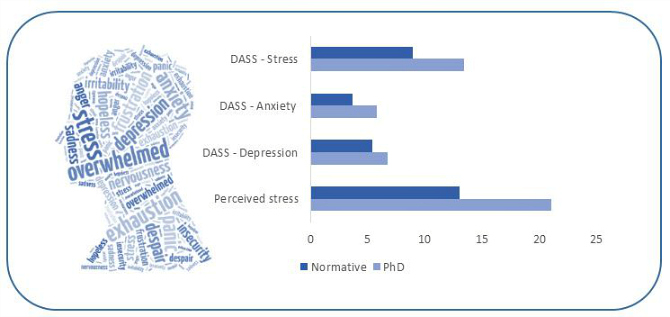

But, alarmingly, 75% reported experiencing moderate to severe depression. This is a rate significantly higher than that observed in the general population and pre-pandemic PhD student cohorts .

Risk of depression

Our findings suggested an increased risk of depression among those in the research-heavy stage of their PhD – for example during data collection or laboratory experiments. This was in contrast to those in the initial stages, or who were nearing the end of their PhD and writing up their research. The data collection stage was more likely to have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Our research also showed that PhD students with caring responsibilities faced a greatly increased risk of depression. In our our study , we found that PhD students with childcare responsibilities were 14 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than PhD students without children.

This does align with findings on people in the general UK population with childcare responsibilities during the pandemic. Adults with childcare responsibilities were 1.4 times more likely to develop depression or anxiety compared to their counterparts without children or childcare duties.

It was also interesting to find that PhD students facing the disruption caused by the pandemic who did not receive an extension – extra financial support and time beyond the expected funding period – or were uncertain about whether they would receive an extension at the time of our study, were 5.4 times more likely to experience significant depression.

Our research also used a questionnaire designed to measure effective and ineffective ways to cope with stressful life events. We used this to look at which coping skills – strategies to deal with challenges and difficult situations — used by PhD students were associated with lower depression levels. These “good” strategies included “getting comfort and understanding from someone” and “taking action to try to make the situation better”.

Interestingly, female PhD students, who were slightly less likely than men to experience significant depression, showed a greater tendency to use good coping approaches compared to their counterparts. Specifically, they favoured the above two coping strategies that are associated with lower levels of depression.

On the other hand, certain coping strategies were associated with higher depression levels. Prominent among these were self-critical tendencies and the use of substances like alcohol or drugs to cope with challenging situations.

A supportive environment

Creating a supportive environment is not solely the responsibility of individual students or academic advisors. Universities and funding bodies must play a proactive role in mitigating the challenges faced by PhD students.

By taking proactive steps, universities could create a more supportive environment for their students and help to ensure their success.

Training in coping skills could be extremely beneficial for PhD students. For instance, the University of Cambridge includes this training as part of its building resilience course .

A focus on good strategies or positive reframing – focusing on positive aspects and potential opportunities – could be crucial. Additionally, encouraging PhD students to seek emotional support may also help reduce the risk of depression.

Another example is the establishment of PhD wellbeing support groups , an intervention funded by the Office for Students and Research England Catalyst Fund .

Groups like this serve as a platform for productive discussions and meaningful interactions among students, facilitated by the presence of a dedicated mental health advisor.

Our research showed how much financial insecurity and caring responsibilities had an effect on mental health. More practical examples of a supportive environment offered by universities could include funded extensions to PhD study and the availability of flexible childcare options.

By creating supportive environments, universities can invest in the success and wellbeing of the next generation of researchers.

- Higher education

- Mental health

- Coping strategies

- PhD students

- Give me perspective

Service Centre Senior Consultant

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

Managing While and Post-PhD Depression And Anxiety: PhD Student Survival Guide

Embarking on a PhD journey can be as challenging mentally as it is academically. With rising concerns about depression among PhD students, it’s essential to proactively address this issue. How to you manage, and combat depression during and after your PhD journey?

In this post, we explore the practical strategies to combat depression while pursuing doctoral studies.

From engaging in enriching activities outside academia to finding supportive networks, we describe a variety of approaches to help maintain mental well-being, ensuring that the journey towards academic excellence doesn’t come at the cost of your mental health.

How To Manage While and Post-Phd Depression

| – Participate in sports, arts, or social gatherings. – Temporarily remove the weight of your studies from your mind. | |

| – Find a mentor who is encouraging and positive. – Look for a ‘yes and’ approach to boost morale. | |

| – Regular exercise like walking, swimming, gym combats depression – Improves mood and overall wellbeing. | |

| – Choose a graduate program that fosters community. – Ensure open discussion and support for mental health. – Select a university with the right support system. | |

| – Understand your choices in the PhD journey. – Consider deferment, pause, or quitting if needed. |

Why PhD Students Are More Likely To Experience Depression Than Other Students

The journey of a PhD student is often romanticised as one of intellectual rigour and eventual triumph.

However, beneath this veneer lies a stark reality: PhD students are notably more susceptible to experiencing depression and anxiety.

This can be unfortunately, quite normal in many PhD students’ journey, for several reasons:

Grinding Away, Alone

Imagine being a graduate student, where your day-to-day life is deeply entrenched in research activities. The pressure to consistently produce results and maintain productivity can be overwhelming.

For many, this translates into long hours of isolation, chipping away at one’s sense of wellbeing. The lack of social support, coupled with the solitary nature of research, often leads to feelings of isolation.

Mentors Not Helping Much

The relationship with a mentor can significantly affect depression levels among doctoral researchers. An overly critical mentor or one lacking in supportive guidance can exacerbate feelings of imposter syndrome.

Students often find themselves questioning their capabilities, feeling like they don’t belong in their research areas despite their achievements.

Nature Of Research Itself

Another critical factor is the nature of the research itself. Students in life sciences, for example, may deal with additional stressors unique to their field.

Specific aspects of research, such as the unpredictability of experiments or the ethical dilemmas inherent in some studies, can further contribute to anxiety and depression among PhD students.

Competition Within Grad School

Grad school’s competitive environment also plays a role. PhD students are constantly comparing their progress with peers, which can lead to a mental health crisis if they perceive themselves as falling behind.

This sense of constant competition, coupled with the fear of failure and the stigma around mental health, makes many hesitant to seek help for anxiety or depression.

How To Know If You Are Suffering From Depression While Studying PhD?

If there is one thing about depression, you often do not realise it creeping in. The unique pressures of grad school can subtly transform normal stress into something more insidious.

As a PhD student in academia, you’re often expected to maintain high productivity and engage deeply in your research activities. However, this intense focus can lead to isolation, a key factor contributing to depression and anxiety among doctoral students.

Changes in Emotional And Mental State

You might start noticing changes in your emotional and mental state. Feelings of imposter syndrome, where you constantly doubt your abilities despite evident successes, become frequent.

This is especially true in competitive environments like the Ivy League universities, where the bar is set high. These feelings are often exacerbated by the lack of positive reinforcement from mentors, making you feel like you don’t quite belong, no matter how hard you work.

Lack Of Pleasure From Previously Enjoyable Activities

In doctoral programs, the stressor of overwork is common, but when it leads to a consistent lack of interest or pleasure in activities you once enjoyed, it’s a red flag. This decline in enjoyment extends beyond one’s research and can pervade all aspects of life.

The high rates of depression among PhD students are alarming, yet many continue to suffer in silence, afraid to ask for help or reveal their depression due to the stigma associated with mental health issues in academia.

Losing Social Connections

Another sign is the deterioration of social connections. Graduate student mental health is significantly affected by social support and isolation.

You may find yourself withdrawing from friends and activities, preferring the solitude that ironically feeds into your sense of isolation.

Changes In Appetite And Weight

Changes in appetite and weight can be a significant indicator of depression. As they navigate the demanding PhD study, students might experience fluctuations in their eating habits.

Some may find themselves overeating as a coping mechanism, leading to weight gain. Others might lose their appetite altogether, resulting in noticeable weight loss.

These changes are not just about food; they reflect deeper emotional and mental states.

Such shifts in appetite and weight, especially if sudden or severe, warrant attention as they may signal underlying depression, a common issue in the high-stress environment of PhD studies.

Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

PhD students grappling with depression often feel immense pressure to excel academically while battling isolation and imposter syndrome. Lacking adequate mental health support, some turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms like substance abuse. These may include:

- Overeating,

- And many more.

These provide temporary relief from overwhelming stress and emotional turmoil. However, such methods can exacerbate their mental health issues, creating a vicious cycle of dependency and further detachment from healthier coping strategies and support systems.

It’s essential for PhD students experiencing depression to recognise these signs and seek professional help. Resources like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are very helpful in this regard.

Suicidal Thoughts Or Attempts

Suicidal thoughts or attempts may sound extreme, but they can happen in PhD studies. This is because of the high-pressure environment of PhD studies.

Doctoral students, often grappling with intense academic demands, social isolation, and imposter syndrome, can be susceptible to severe mental health crises.

When the burden becomes unbearable, some may experience thoughts of self-harm or suicide as a way to escape their distress. These thoughts are a stark indicator of deep psychological distress and should never be ignored.

It’s crucial for academic institutions and support networks to provide robust mental health resources and create an environment where students feel safe to seek help and discuss their struggles openly.

How To Prevent From Depression During And After Ph.D?

A PhD student’s experience is often marked by high rates of depression, a concern echoed in studies from universities like the University of California and Arizona State University. If you are embarking on a PhD journey, make sure you are aware of the issue, and develop strategies to cope with the stress, so you do not end up with depression.

Engage With Activities Outside Academia

One effective strategy is engaging in activities outside academia. Diverse interests serve as a lifeline, breaking the monotony and stress of grad school. Some activities you can consider include:

- Social gatherings.

These activities provide a crucial balance. For instance, some students highlighted the positive impact of adopting a pet, which not only offered companionship but also a reason to step outside and engage with the world.

Seek A Supportive Mentor

The role of a supportive mentor cannot be overstated. A mentor who adopts a ‘yes and’ approach rather than being overly critical can significantly boost a doctoral researcher’s morale.

This positive reinforcement fosters a healthier research environment, essential for good mental health.

Stay Active Physically

Physical exercise is another key element. Regular exercise has been shown to help cope with symptoms of moderate to severe depression. It’s a natural stress reliever, improving mood and enhancing overall wellbeing. Any physical workout can work here, including:

- Brisk walking

- Swimming, or

- Gym sessions.

Seek Positive Environment

Importantly, the graduate program environment plays a critical role. Creating a community where students feel comfortable to reveal their depression or seek help is vital.

Whether it’s through formal support groups or informal peer networks, building a sense of belonging and understanding can mitigate feelings of isolation and imposter syndrome.

This may be important, especially in the earlier stage when you look and apply to universities study PhD . When possible, talk to past students and see how are the environment, and how supportive the university is.

Choose the right university with the right support ensures you keep depression at bay, and graduate on time too.

Remember You Have The Power

Lastly, acknowledging the power of choice is empowering. Understanding that continuing with a PhD is a choice, not an obligation. If things become too bad, there is always an option to seek a deferment, pause. You can also quit your studies too.

Work on fixing your mental state, and recover from depression first, before deciding again if you want to take on Ph.D studies again. There is no point continuing to push yourself, only to expose yourself to self-harm, and even suicide.

Wrapping Up: PhD Does Not Need To Ruin You

Combating depression during PhD studies requires a holistic approach. Engaging in diverse activities, seeking supportive mentors, staying physically active, choosing positive environments, and recognising one’s power to make choices are all crucial.

These strategies collectively contribute to a healthier mental state, reducing the risk of depression. Remember, prioritising your mental well-being is just as important as academic success. This helps to ensure you having a more fulfilling and sustainable journey through your PhD studies.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Self-reported depression and anxiety among graduate students during the covid-19 pandemic: examining risk and protective factors.

1. Introduction

1.1. the current study, 1.2. theoretical framework, 2. materials and methods, 2.1. recruitment and sampling, 2.2. measures, outcome variables, 2.3. independent variables, 2.4. sociodemographic factors, statistical analysis, 3.1. depression, 3.2. anxiety, 4. discussion, 4.1. implications for higher education research and practice, limitations, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Mistler, B.J.; Director; Reetz, D.R.; Krylowicz, B.; Barr, V. The AUCCCD Annual Survey and Report Overview. 2013. Available online: http://files.cmcglobal.com/Monograph_2012_AUCCCD_Public.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Spring. Reference Group Data Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II%20SPRING%202016%20US%20REFERENCE%20GROUP%20DATA%20REPORT.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Feng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, X.; Geng, W. Change in the level of depression among Chinese college students from 2000 to 2017: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2020 , 48 , 1–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Impact of COVID-19 on College Student Well-Being. Available online: https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/Healthy_Minds_NCHA_COVID_Survey_Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Abelson, S.; Heinze, J.; Jirsa, M.; Morigney, J.; Patterson, A.; Singh, M.; Eisenberg, D. Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013–2021. J. Affect. Disord. 2022 , 306 , 138–147. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Farrer, L.M.; Gulliver, A.; Bennett, K.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Griffiths, K.M. Demographic and psychosocial predictors of major depression and generalised anxiety disorder in Australian university students. BMC Psychiatry 2016 , 16 , 241. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- National Center for Education Statistics. The NCES Fast Facts Tool Provides Quick Answers to Many Education Questions. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372#Postsecondary-enrollment (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E.; Hefner, J.L. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007 , 77 , 534–542. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lederer, A.M.; Hoban, M.T.; Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Eisenberg, D. More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ. Behav. 2021 , 48 , 14–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- ACHA. American College Health Association-national college health assessment II: Graduate and professional student executive summary spring 2019 ; American College Health Association: Hanover, MD, USA, 2019; Available online: https://dev.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_GRADUATE_AND_PROFESSIONAL_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Evans, T.M.; Bira, L.; Gastelum, J.B.; Weiss, L.T.; Vanderford, N.L. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018 , 36 , 282–284. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-has-the-pandemic-affected-graduate-students-this-study-has-answers (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Alonzi, S.; La Torre, A.; Silverstein, M.W. The psychological impact of preexisting mental health and physical health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020 , 12 , 236–238. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Qui, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020 , 33 , e100213. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Moayed, M.S.; Rahimibashar, F.; Shojaei, S.; Ashtari, S.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A. Comparison of the severity of psychological distress among four groups of an Iranian population regarding COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2020 , 20 , 402. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Women Earned Majority of Doctoral Degrees in 2016 for 8th Straight Year and Outnumber Men in Grad School 135 to 100. American Enterprise Institute—AEI. Available online: https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/women-earned-majority-of-doctoral-degrees-in-2016-for-8th-straight-year-and-outnumber-men-in-grad-school-135-to-100/#:~:text=13)%2C%20showing%20tht%20there%20is (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Aloufi, F.; Ibrahim, A.L.; Elsayed, A.M.A.; Wardat, Y.; Ahmed, A.O. Virtual mathematics education during COVID-19: An exploratory study of teaching practices for teachers in simultaneous virtual classes. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021 , 20 , 85–113. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wardat, Y.; Belbase, S.; Tairab, H. Mathematics Teachers’ perceptions of trends in international mathematics and science study (TIMSS)-Related practices in Abu Dhabi Emirate schools. Sustainability 2022 , 14 , 5436. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hamad, S.; Tairab, H.; Wardat, Y.; Rabbani, L.; AlArabi, K.; Yousif, M.; Abu-Al-Aish, A.; Stoica, G. Understanding science teachers’ implementations of integrated STEM: Teacher perceptions and practice. Sustainability 2022 , 14 , 3594. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Chronicle of Higher Education. For Many Graduate Students, Covid-19 Pandemic Highlights Inequities. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/for-many-graduate-students-covid-19-pandemic-highlights-inequities/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- The American Associations for the Advancement of Science. As the Pandemic Erodes Grad Student Mental Health, Academics Sounds the Alarm. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2020/09/pandemic-erodes-grad-student-mental-health-academics-sound-alarm (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Harrison, D.; Rowland, S.; Wood, G.; Bakewell, L.; Petridis, I.; Long, K.; Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Barreto, M.; Wilson, M.; et al. Designing Technology-Mediated Peer Support for Postgraduate Research Students at Risk of Loneliness and Isolation. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2023 , 30 , 1–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Loneliness and depression among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 outbreak: A moderated mediation model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020 , 112 , 1392–1406. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rahman, R.; Ross, A.; Pinto, R. The critical importance of community health workers as first responders to COVID-19 in USA. Health Promot. Int. 2021 , 36 , 1498–1507. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Davies, H.; Cheung, M. COVID-19 and first responder social workers: An unexpected mental health storm. Soc. Work. 2022 , 67 , 114–122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Burns, K.F.; Strickland, C.J.; Horney, J.A. Public health student response to COVID-19. J. Community Health 2021 , 46 , 298–303. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Prince, J.P. University student counseling and mental health in the United States: Trends and challenges. Ment. Health Prev. 2015 , 3 , 5–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vidourek, R.A.; King, K.A.; Nabors, L.A.; Merianos, A.L. Students’ benefits and barriers to mental health help-seeking. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. Open Access J. 2014 , 2 , 1009–1022. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Duffy, A.; Saunders, K.E.; Malhi, G.S.; Patten, S.; Cipriani, A.; McNevin, S.H.; MacDonald, E.; Geddes, J. Mental health care for university students: A way forward? Lancet Psychiatry 2019 , 6 , 885–887. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Amendola, S.; Spensieri, V.; Hengartner, M.P.; Cerutti, R. Mental health of Italian adults during COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021 , 26 , 644–656. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ren, X.; Huang, W.; Pan, H.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Mental health during the Covid-19 outbreak in China: A meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020 , 91 , 1033–1045. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wang, Y.; Kala, M.P.; Jafar, T.H. Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020 , 15 , e0244630. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Larson, L.R.; Sharaievska, I.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Mullenback, L.; Cloutier, S.; Vu, T.M.; Thomsen, H.; Reigner, N.; et al. Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021 , 16 , e0245327. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Yang, D.; Tu, C.; Dai, X. The effect of the 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic on college students in Wuhan. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020 , 12 , 6–14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Posselt, J. Discrimination, Competitiveness, and Support in US Graduate Student Mental Health ; Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, Rossier School of Education, University of Southern California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014 , 129 (Suppl. 2), 19–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1990 , 43 , 1241. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001 , 16 , 606–613. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- American Psychological Association. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2), Construct: Depressive symptoms. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Sun, Y.; Fu, Z.; Bo, Q.; Mao, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry 2020 , 20 , 474. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care 2008 , 46 , 266–274. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging 2004 , 26 , 655–672. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980 , 39 , 472. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Hefner, J.; Eisenberg, D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009 , 79 , 491–499. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Taylor, S.E.; Stanton, A.L. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007 , 3 , 377–401. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/college-students-and-mental-health/index.shtml (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Awiphan, R.; Phosuya, C.; Ruanta, Y.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021 , 11 , 10173. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vahratian, A.; Blumberg, S.J.; Terlizzi, E.P.; Schiller, J.S. Symptoms of Anxiety or Depressive Disorder and Use of Mental Health Care Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, August 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021 , 70 , 490–494. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aucejo, E.M.; French, J.; Araya, M.P.U.; Zafar, B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Public Econ. 2020 , 191 , 104271. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, C.H.; Pinder-Amaker, S.; Hahm, H.C.; Chen, J.A. Priorities for addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022 , 70 , 1356–1358. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Faura-Martínez, U.; Lafuente-Lechuga, M.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Sustainability of the Spanish university system during the pandemic caused by COVID-19. Educ. Rev. 2021 , 74 , 645–663. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chakraborty, P.; Mittal, P.; Gupta, M.S.; Yadav, S.; Arora, A. Opinion of students on online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021 , 3 , 357–365. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jabbari, J.; Ferris, D.; Frank, T.; Malik, S.; Bessaha, M.L. Intersecting race and gender across hardships and mental health during COVID-19: A moderated-mediation model of graduate students at two universities. Race Soc. Probl. 2022 , 2022 , 1–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alismaiel, O.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Al-Rahmi, W. Online Learning, Mobile Learning and social media technologies: An Empirical Study on Constructivism Theory during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022 , 14 , 11134. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Variable | N | % | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.88 (10.00) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 91 | 26.7 | |

| Female | 233 | 68.3 | |

| Non-binary/third gender | 11 | 3.2 | |

| Not specified | 6 | 1.8 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 216 | 63.3 | |

| Black | 21 | 6.2 | |

| Asian | 66 | 19.4 | |

| Multiracial/biracial | 12 | 3.5 | |

| Other | 11 | 3.2 | |

| Not specified | 15 | 4.4 | |

| Hispanic | |||

| No | 289 | 84.8 | |

| Yes | 44 | 12.9 | |

| Unspecified | 8 | 2.3 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 248 | 77.3 | |

| Identifies as gay/lesbian/bisexual | 73 | 22.7 | |

| Not specified | 20 | 5.9 | |

| Transgender | |||

| No | 325 | 95.3 | |

| Yes | 10 | 2.9 | |

| Not specified | 6 | 1.8 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single, never married | 234 | 68.6 | |

| Married/living common-law | 86 | 25.2 | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 21 | 6.2 | |

| Children | |||

| No | 266 | 78.0 | |

| Yes | 74 | 21.7 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Country of birth | |||

| United States | 232 | 74.9 | |

| Other | 102 | 29.9 | |

| Not specified | 7 | 2.1 | |

| Household income | |||

| <$20,000 | 52 | 15.2 | |

| $20,000 to $39,999 | 85 | 24.9 | |

| $40,000 to $59,999 | 37 | 10.9 | |

| $60,000 to $79,999 | 43 | 12.6 | |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 34 | 10.0 | |

| >$100,000 | 84 | 24.6 | |

| Not specified | 6 | 1.8 | |

| Coping, scale of 1–10 (not coping to coping well) | 6.15 (2.17) | ||

| Emotional support, scale of 1–10 (none to a lot) | 7.62 (2.19) | ||

| Physical health, perceived | |||

| Poor | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Fair | 18 | 5.3 | |

| Good | 81 | 23.9 | |

| Very good | 160 | 46.9 | |

| Excellent | 76 | 22.3 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Mental/emotional health, perceived | |||

| Poor | 31 | 9.1 | |

| Fair | 106 | 31.3 | |

| Good | 117 | 34.5 | |

| Very good | 63 | 18.6 | |

| Excellent | 22 | 6.5 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Loneliness | |||

| Never lonely | 63 | 18.5 | |

| Sometimes lonely | 184 | 54.1 | |

| Often or always lonely | 93 | 27.4 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Increased pressure to be productive due to COVID-19 | |||

| Strongly disagree | 20 | 5.9 | |

| Disagree | 26 | 7.6 | |

| Neither agree or disagree | 75 | 22.0 | |

| Agree | 135 | 39.6 | |

| Strongly agree | 78 | 22.9 | |

| Not specified | 7 | 2.1 | |

| Inability to pay full rent/mortgage, previous 3 months | |||

| No | 312 | 91.5 | |

| Yes | 27 | 7.9 | |

| Not specified | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Close family/friend test positive for COVID-19 | |||

| No | 206 | 60.4 | |

| Yes, one person | 44 | 12.9 | |

| Yes, more than 1 | 90 | 26.4 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Close family/friend die from COVID-19 | |||

| No | 309 | 90.6 | |

| Yes, one person | 16 | 4.7 | |

| Yes, more than one | 15 | 4.4 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Time spent searching for COVID-19 information | |||

| Never or almost never | 21 | 6.2 | |

| A few times a month | 49 | 14.4 | |

| A few times a week | 112 | 32.8 | |

| Once a day | 84 | 24.6 | |

| A few times a day | 43 | 12.6 | |

| I try to stay updated all the time | 31 | 9.1 | |

| Not specified | 1 | 0.3 |

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | OR | CI | |

| Age | 0.95 *** | 0.93, 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.04 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | ref | ref | ||

| Female | 0.90 | 0.56, 1.46 | 0.57 | 0.28, 1.14 |

| Non-binary | 6.92 | 0.85, 56.20 | 4.41 | 0.24, 81.64 |

| Race | ||||

| White | ref | ref | ||

| Black | 0.69 | 0.29, 1.65 | 0.52 | 0.12, 2.24 |

| Asian | 0.95 | 0.55, 1.64 | 1.02 | 0.40, 2.60 |

| Multi/biracial | 3.26 | 0.70, 15.26 | 2.72 | 0.39, 19.20 |

| Other | 1.21 | 0.35, 4.15 | 0.91 | 0.16, 5.08 |

| Hispanic | 0.98 | 0.52, 1.84 | 0.88 | 0.30, 2.62 |

| Identifies as LGB | 1.92 * | 1.12, 3.30 | 1.60 | 0.73, 3.48 |

| Transgender | 1.23 | 0.36, 4.12 | 0.35 | 0.04, 2.74 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single, never married | ref | ref | ||

| Married/common-law | 0.42 *** | 0.26, 0.69 | 1.36 | 0.50, 3.70 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.43 *** | 0.17, 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.16, 6.00 |

| Has children | 0.32 *** | 0.19, 0.52 | 0.30 * | 0.10, 0.93 |

| Born outside the U.S. | 1.01 | 0.64, 1.61 | 1.50 | 0.66, 3.40 |

| Household income | 0.74 | 0.66, 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.78, 1.15 |

| Loneliness | ||||

| Never lonely | ref | ref | ||

| Sometimes lonely | 5.78 *** | 3.20, 10.44 | 2.83 ** | 1.32, 6.03 |

| Often or always lonely | 23.71 | 10.88, 51.64 | 6.33 *** | 2.17, 18.47 |

| Coping | 0.61 *** | 0.54, 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.70, 1.02 |

| Emotional support | 0.77 *** | 0.69, 0.85 | 0.84 * | 0.72, 0.99 |

| Physical health, perceived | 0.50 *** | 0.38, 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.46, 1.02 |

| Mental/emotional health, perceived | 0.30 *** | 0.23, 0.39 | 0.52 *** | 0.36, 0.76 |

| Someone close test positive COVID | 0.93 | 0.73, 1.18 | 0.89 | 0.61, 1.28 |

| Someone close died from COVID | 1.19 | 0.74, 1.92 | 1.42 | 0.70, 2.88 |

| Time searching for COVID-19 info | 1.37 *** | 1.15, 1.62 | 1.28 * | 1.01, 1.62 |

| Pressure to be productive | 0.58 *** | 0.48, 0.72 | 1.13 | 0.86, 1.49 |

| Inability to pay mortgage/rent | 2.18 | 0.91, 5.26 | 7.98 * | 1.11, 57.36 |

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | OR | CI | |

| Age | 0.95 | 0.93, 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.95, 1.03 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | ref | ref | ||

| Female | 1.03 | 0.66, 1.62 | 0.77 | 0.42, 1.42 |

| Non-binary | 2.88 | 0.82, 10.16 | 3.21 | 0.23, 45.67 |

| Race | ||||

| White | ref | Ref | ||

| Black | 0.80 | 0.35, 1.86 | 1.25 | 0.33, 4.78 |

| Asian | 0.73 | 0.44, 1.21 | 1.25 | 0.53, 2.95 |

| Multi/biracial | 1.86 | 0.59, 5.88 | 1.11 | 0.24, 5.14 |

| Other | 0.79 | 0.26, 2.43 | 1.01 | 0.21, 4.90 |

| Hispanic | 0.96 | 0.52, 1.75 | 1.06 | 0.40, 2.78 |

| Identifies as LGB | 2.44 *** | 1.49, 4.01 | 2.33 * | 1.16, 4.67 |

| Transgender | 1.09 | 0.35, 3.44 | 0.25 | 0.04, 1.73 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, never married | ref | ref | ||

| Married/common-law | 0.47 *** | 0.29, 0.75 | 2.24 | 0.88, 5.70 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.49 | 0.21, 1.15 | 2.97 | 0.58, 15.29 |

| Has children | 0.35 *** | 0.22, 0.58 | 0.33 * | 0.12, 0.94 |

| Born outside the U.S. | 0.68 | 0.44, 1.04 | 0.34 ** | 0.16, 0.72 |

| Household income | 0.77 *** | 0.69, 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.73, 1.04 |

| Loneliness | ||||

| Never lonely | ref | ref | ||

| Sometimes lonely | 3.92 *** | 2.23, 6.87 | 1.77 | 0.84, 3.72 |

| Often or always lonely | 13.45 *** | 6.92, 26.15 | 3.65 ** | 1.43, 9.34 |

| Coping | 0.57 *** | 0.50, 0.64 | 0.78 ** | 0.66, 0.92 |

| Emotional support | 0.81 *** | 0.74, 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.84, 1.10 |

| Physical health, perceived | 0.55 *** | 0.43, 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.67, 1.31 |

| Mental/emotional health, perceived | 0.25 *** | 0.19, 0.32 | 0.41 *** | 0.29, 0.59 |

| Someone close test positive COVID | 1.00 | 0.80, 1.26 | 0.97 | 0.70, 1.36 |

| Someone close died from COVID | 0.96 | 0.63, 1.47 | 0.90 | 0.47, 1.70 |

| Time searching for COVID-19 info | 1.38 *** | 1.18, 1.62 | 1.26 * | 1.02, 1.57 |

| Increased pressure to be productive | 1.85 *** | 1.51, 2.26 | 1.18 | 0.91, 1.52 |

| Inability to pay mortgage/rent | 2.01 | 0.94, 4.31 | 2.17 | 0.60, 7.86 |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Malik, S.; Bessaha, M.; Scarbrough, K.; Younger, J.; Hou, W. Self-Reported Depression and Anxiety among Graduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Risk and Protective Factors. Sustainability 2023 , 15 , 6817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086817

Malik S, Bessaha M, Scarbrough K, Younger J, Hou W. Self-Reported Depression and Anxiety among Graduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Risk and Protective Factors. Sustainability . 2023; 15(8):6817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086817

Malik, Sana, Melissa Bessaha, Kathleen Scarbrough, Jessica Younger, and Wei Hou. 2023. "Self-Reported Depression and Anxiety among Graduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Risk and Protective Factors" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086817

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychol Res Behav Manag

Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among doctoral students: the mediating effect of mentoring relationships on the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety

1 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China, gro.latipsoh-js@hyoahz

2 Department of Library and Medical Information, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

3 Department of Social Medicine, School of Public Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

4 Key Laboratory of Immunodermatology, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

5 Department of Dermatology, First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Weiqiu Wang

Shanshan jia.

6 Key Laboratory of Health Ministry for Congenital Malformation, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Deshu Shang

7 Department of Developmental Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Medical Cell Biology, Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

8 Department of Developmental Cell Biology, Cell Biology Division, Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, Ministry of Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Yangguang Shao

9 Department of Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, National Health Commission of the PRC, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

10 Department of Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Medical Cell Biology, Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Xinwang Zhu

11 Department of Nephrology, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Shengnan Yan

12 Graduate Division, School of Public Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Yuhong Zhao

Although the mental health status of doctoral students deserves attention, few scholars have paid attention to factors related to their mental health problems. We aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in doctoral students and examine possible associated factors. We further aimed to assess whether mentoring relationships mediate the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 325 doctoral students in a medical university. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 scale were used to assess depression and anxiety. The Research Self-Efficacy Scale was used to measure perceived ability to fulfill various research-related activities. The Advisory Working Alliance Inventory-student version was used to assess mentoring relationships. Linear hierarchical regression analyses were performed to determine if any factors were significantly associated with depression and anxiety. Asymptotic and resampling methods were used to examine whether mentoring played a mediating role.

Approximately 23.7% of participants showed signs of depression, and 20.0% showed signs of anxiety. Grade in school was associated with the degree of depression. The frequency of meeting with a mentor, difficulty in doctoral article publication, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program was associated with both the level of depression and anxiety. Moreover, research self-efficacy and mentoring relationships had negative relationships with levels of depression and anxiety. We also found that mentoring relationships mediated the correlation between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

The findings suggest that educational experts should pay close attention to the mental health of doctoral students. Active strategies and interventions that promote research self-efficacy and mentoring relationships might be beneficial in preventing or reducing depression and anxiety.

Introduction

Recently, the mental health status of students has become a hot topic in public health, higher education, and research policy. 1 – 3 Depression and anxiety are two of the most common psychological disorders. Researchers have reported depression and anxiety among students in several countries and in numerous disciplines, such as counseling, medicine, law, and psychology. 4 – 14 Depression is defined as a mood that includes a feeling of hopelessness, helplessness, or worthlessness. 2 Anxiety is an emotion characterized by unpleasant inner feelings, which is accompanied by caution, complaints, meditation, nervousness, and worry. 5 Depression and anxiety can affect a person’s behavior, academic performance, and general health, as well as quality of sleep, eating habits, and well-being. 8 In addition, it has been confirmed that depression and psychological distress influence suicidal ideation in undergraduate and graduate students. 15 – 18 However, mental health among doctoral students has been relatively ignored by researchers and educational experts. It has only been in the last 2 years that this topic has begun to attract more and more attention.

A doctoral student’s school career is full of hardships and happiness. Doctoral students frequently feel a sense of urgency, worry, and stress as they work toward their doctoral degrees. In addition to financial support and future employment, doctoral students worry about writing a thesis, publishing papers, and handling relationships with advisors. In recent years, a few scholars have explored the prevalence of mental health problems among PhD students. 3 , 12 , 19 – 21 In 2013, Levecquea et al investigated PhD students in Belgium. They concluded that approximately half the PhD students in Flanders had at least two symptoms, and 32% reported at least four symptoms on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12). 3 According to a 2015 survey at the University of California, approximately half the PhD students in science and engineering were depressed. 12 Springer Nature did a survey of PhD students in 2017, and confirmed that 12% reported seeking help for anxiety or depression caused by PhD studies. 20 A 2018 survey of graduate students via social media revealed that 41% of graduate students scored in the moderate–severe range for anxiety and 39% scored in the moderate–severe range for depression. 21 Doctoral students with mental health issues are more likely to drop out of PhD programs. 22 The high attrition rate in PhD programs caused by the dropout of PhD students with psychological illness is damaging to research institutions and the whole research industry. 23 However, there have been few reports on the mental health of doctoral students in medical universities.

Students in medical schools engage in rigorous medical training. 24 , 25 Previous studies have demonstrated that medical students have more pressure, more burnout, and a greater prevalence of mental health disorders than the general population or students in other disciplines. 26 – 31 Medical training varies considerably by discipline, institution, and country. US and Canadian medical students enter medical education systems after they receive a bachelor’s degree. 32 , 33 In China, students can enter medical schools after graduating from high school (similarly to the UK and France). In general, there is an entrance examination required for students with a master’s degree who would like to study for doctoral degrees. Doctoral students need another 3 years to earn a doctoral degree, allowing for an extension of 3 years. Master’s degree candidates in grade two have the choice to apply for a master–doctor combined-training program (a total of 5 years for a doctoral degree, allowing an extension of 3 years). Doctoral students can be either full-time or part-time students. Part-time doctoral students are those who are studying doctoral courses while working in clinical settings or having another job. As such, for clinical doctoral students, some are still fully engaged in clinical work while earning their doctoral degree, whereas others are temporarily away from clinical work to concentrate on the doctoral program research. It is a bit too much to expect clinical doctoral students to do clinical work and research at the same time throughout their doctoral training.

Sociodemographic variables, such as age, sex, and marital status, have been reported to be associated with the mental health of postgraduate students. 8 , 10 However, sex differences in depression among medical students have also yielded mixed results, showing either no difference or high prevalence among female or male medical students. 27 , 29 , 33 Further exploration among doctoral students is still needed. The execution phase during doctoral study has been shown to be prone to mental health problems among doctoral students. 3 Additionally, researchers have suggested that work–life balance is the key factor related to the mental health problems of postgraduate students. 3 , 21 Employed doctoral students work full time or part time while they are studying for their doctoral degree. In this case, conflict concerns not only balancing family and work but also completing the doctoral program itself. Few scholars have focused on the conflicts among family, work, and a doctoral program. Getting married and raising children also puts a strain on doctoral students. Doing experiments, writing a doctoral thesis, and publishing doctoral qualification papers requires considerable time, energy, and financial resources.

Mentorship effectiveness and mentoring functions are thought to be vital to graduate-student programs. 34 , 35 Mentors have a great responsibility to guide their doctoral students through the doctoral program. Advisor mentoring affects student-research self-efficacy, productivity, and development as a scientist. 36 – 38 Recently, a study explored the effect of a supervisor’s leadership style on the mental health of graduate students. 3 Nearly half the doctoral students who withdrew from the doctoral program reported experiencing insufficient supervision, highlighting the fact that good supervision was important for completing the doctoral program. 39 , 40 A survey in 2018 indicated that a weak relationship with a mentor is a common characteristic of most graduate students who experience anxiety and/or depression. 21

Research self-efficacy refers to the individual’s confidence in the successful completion of various aspects of the scientific research process, 41 such as data collection, performing experimental procedures, and writing papers. 42 Studies have evaluated the important role of research self-efficacy in research training. Self-efficacy is a factor that affects how much effort students spend on research tasks and how long they persist when they experience difficulties. 43 Some universities in the US have used research self-efficacy to evaluate the effects of degree programs on graduate research ability. 44 A study has shown that research self-efficacy can predict the research interest and knowledge of doctoral students. 45 Some researchers have reported that high research self-efficacy is correlated with future research involvement and research productivity. 46 , 47 It was suggested that research self-efficacy could play a mediating role between the research-training environment and scientific research output. Furthermore, the relationship between stress and depression has been shown to be mediated by stress management self-efficacy. 48 Interestingly, the length of student–advisor relationships has been reported to be significantly correlated with student research self-efficacy. 36 Moreover, among agricultural students, research self-efficacy has been found to be negatively associated with research anxiety. 49 Therefore, the higher the students’ research self-efficacy, the lower their research anxiety. However, it is not clear whether scientific research self-efficacy is correlated with levels of generalized anxiety.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety among doctoral students in a medical university in China, determine factors that are associated with depression and anxiety, determine whether mentoring relationships and research self-efficacy are associated with depression and anxiety, and test whether mentoring relationships mediate the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

Participants

We recruited doctoral students from October to November 2017 using a combination of snowball sampling and stratified sampling from five medical schools and four affiliated clinical hospitals at a medical university in northeast China. This university has the authority to grant doctoral degrees in six major disciplines (basic medicine, clinical medicine, biology, stomatology, public health and preventive medicine, and nursing), including 49 different majors. Our inclusion criteria were still studying at the medical university, had not yet earned a PhD degree, enrollment in a successive postgraduate and doctoral program, and no history of depression or anxiety before entering medical school. A total of 437 doctoral students (218 male, 219 female) were enrolled. This study received approval from the Committee for Human Trials of China Medical University (CMU17/375/R). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they entered the experiment. All questionnaires were filled out anonymously and confidentially.

Sociodemographic and doctoral factors

Doctoral students’ sociodemographic status included age, sex, marital status, children, and income. In addition, we selected some doctoral characteristics that might affect the mental health of doctoral students. We asked participants whether they had been employed before doctoral enrollment. Clinical doctoral students refers to students who were doing clinical work while earning their doctoral degree. Grade was measured assigned to one of four categories (1, first year; 2, second year; 3, third year; 4, fourth year or above). Mentors meet with their doctoral students regularly or irregularly. They come together and analyze the latest literature, discuss the research direction or experimental methods, and revise the thesis. Therefore, the frequency of these meetings can reflect the strength of the relationship from a certain quantitative angle. The frequency with which doctoral students met with mentors was measured with one item: “On average, how often do you meet with your advisor? (1, at least once a week; 2, at least once a month; 3, seldom)”. In most medical universities, doctoral students are required to publish at least one academic paper indexed by the Science Citation Index or Social Science Citation Index. Only when this qualification has been reached are doctoral students able to apply for a doctoral degree. The perceived difficulty in publishing a doctoral qualification paper was assessed by one item: “How much effort do you think it takes to publish doctoral qualification papers? (1, a little bit of effort; 2, some effort; 3, a lot of effort). Considering that the total time and energy of doctoral students is limited, we asked the doctoral students, “Do you have difficulty in balancing work, family, and the PhD program? (1, almost no difficulty; 2, some difficulty; 3, great difficulty)”.

Depression questionnaire

We chose the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) 50 to evaluate depression among doctoral students. Each item is measured on a 4-point Likert-like scale (0, not at all; 3, almost every day) based on the frequency of depression symptoms over the last 2 weeks. Total scores range from 0 to 27. A higher PHQ-9 score represents more serious depression (0–4, none–minimal; 5–9, mild; 10–14, moderate; 15–19, moderately severe; 20–27, severe). In general, a diagnosis of depression can only be arrived at after clinical assessment by a mental health professional. With such questionnaires as the PHQ-9, it has been shown that at certain cutoffs there is good correlation with diagnostic interviews. PHQ-9 scores of 10 or above had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depressive disorder. 50 The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 has been used in older people and hospital inpatients, with sound reliability. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-9 scale was 0.918.

Anxiety questionnaire

We used the seven item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to indicate the degree of anxiety among doctoral students. 51 The GAD-7 contains seven items that are rated on a 4-point Likert-like scale (0, not at all; 3, almost every day). The total score ranges from 0 to 21. A higher GAD-7 score indicates more serious anxiety (0–4, none–minimal; 5–9, mild; 10–14, moderate; 15–21, severe). Using a threshold score of 10, the GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% for major generalized anxiety disorder. 51 The Chinese version of the GAD-7 has been used in outpatients with satisfactory reliability. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 scale was 0.946.

Mentoring-relationship questionnaire

The 30-item Advisory Working Alliance Inventory-student version (AWAI-S) was used to assess the mentoring relationship from the student’s perspective. 36 This scale is a brief, self-reported measure designed on the basis of the Working Alliance model. Its developer, Schlosser, believed that a favorable supervisory alliance was vital to outcomes. 52 The scale has had good reliability in previous studies. 53 The AWAI-S consists of three domains: rapport (11 items), apprenticeship (14 items), and identification-individuation (5 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). The AWAI-S scale contains 16 reverse-scoring questions. High scores (after reverse scoring) suggest that the advisee has a strong mentoring relationship with the advisor. The internal consistency of AWAI-S scores from previous studies ranged from 0.84 to 0.95 36 , 54 and was 0.95 in this study.

Research Self-Efficacy Scale

The Research Self-Efficacy Scale (RSES) was used to measure the doctoral students’ perceived ability to fulfill various research-related tasks. 55 The RSES comprises 50 items with four subscales: conceptualization (18 items), implementation (19 items), early tasks (5 items), and presenting the results (8 items). Individuals were asked to mark the tasks they perceived they could perform. The strength of each item was rated on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (complete confidence). A total RSES score was calculated, ranging from 75 to 500. A higher score indicates higher self-efficacy. The internal consistency of RSES scores was 0.98 in the present study.

Data analysis

We used SPSS 17.0 for all statistical analyses. We investigated demographic and doctoral characteristics using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-squared for categorical data. Correlations among depression, anxiety, mentoring relationships, and research self-efficacy were examined by Pearson correlation. We performed hierarchical linear regression analysis to explore the association of mentoring relationship and research self-efficacy with depression/anxiety. In this study, depression and anxiety were modeled as dependent variables, RSES as an independent variable, AWAI-S as a mediator, and sociodemographic and doctoral variables as controlled variables. In step 1 of the regression, sociodemographic and doctoral variables were entered as controlled variables. Because linear hierarchical regression analysis requires continuous variables, the grade, frequency of meeting with a mentor, difficulty in publishing a doctoral qualification paper, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program was dummy coded. In step 2 of the regression, research self-efficacy was added. In step 3, the mentoring relationship was added. The asymptotic and resampling method was used to examine mentoring relationship as potential mediator in the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety, based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. 56 A bias-corrected and accelerated (BC a ) 95% CI was used to estimate mediation. If the BC a 95% CI excludes 0, this indicates that the mediation is significant. All statistical tests were two-sided (α=0.05). P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics of respondents

After exclusion of 45 doctoral students who refused to fill out questionnaires, the 392 who completed the questionnaires were included. A total of 67 questionnaires with missing values >10% were deemed invalid. As such, we collected 325 valid responses. The effective response rate was 74.37%. The mean age of the participants was 31.1±5.3 (23–47) years. Of the 325 respondents, 60.3% were female, 50.8% married or lived with a partner, and 40% had one or more child. The monthly income for 56.6% of respondents was <CN¥3,000 per month (equivalent of local per capita income), 50.8% had been employed before doctoral enrollment, and 40.6% were clinical doctoral students. Furthermore, 13.8% seldom met with their mentors, 37.2% thought they should try their best to publish a PhD qualification paper, and 31.1% reported that they had difficulty in balancing work–family–PhD ( Table 1 ).

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics of respondents (n=325)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 325 | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤25 | 30 | 9.2 |

| 26–30 | 151 | 46.5 |

| ≥31 | 144 | 44.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 129 | 39.7 |

| Female | 196 | 60.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 165 | 50.8 |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 160 | 49.2 |

| Have children | ||

| No | 195 | 60 |

| One or more | 130 | 40 |

| Income (CN¥ per month) | ||

| ≤3,000 | 184 | 56.6 |

| 3,001–5,000 | 30 | 9.2 |

| ≥5,001 | 111 | 34.2 |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment | ||

| No | 160 | 49.2 |

| Yes | 165 | 50.8 |

| Clinical doctoral student | ||

| No | 193 | 59.4 |

| Yes | 132 | 40.6 |

| Grade | ||

| First year | 71 | 21.8 |

| Second year | 121 | 37.2 |

| Third year | 116 | 35.7 |

| Fourth year or above | 17 | 5.23 |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor | ||

| At least once a week | 193 | 59.4 |

| At least once a month | 87 | 26.8 |

| Seldom | 45 | 13.8 |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper | ||

| A little bit of effort | 56 | 17.2 |

| Some effort | 148 | 45.5 |

| A lot of effort | 121 | 37.2 |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program | ||

| Almost no difficulty | 98 | 30.2 |

| Some difficulty | 126 | 38.8 |

| Great difficulty | 101 | 31.1 |

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by depression and anxiety

The prevalence of clinical depression was 23.7% (moderate, moderately severe, and severe) and the prevalence of clinical anxiety was 20.0% (moderate and severe; Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). Factors that were significantly different among respondents at varying levels of depression included age, marital status, having children, employment, grade, frequency of meeting with mentors, difficulty in publishing, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program. Factors that were significantly different among respondents at varying levels of anxiety included being a clinical doctoral student, frequency of meeting with mentors, difficulty in publishing, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program.

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by depression (n=325)

| Characteristics | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None–minimal (n=114) | Mild (n=134) | Moderate (n=38) | Moderately severe (n=26) | Severe (n=13) | -value | |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.023 | |||||

| ≤25 | 15 (50.0) | 11 (36.7) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| 26–30 | 57 (37.7) | 60 (39.7) | 21 (13.9) | 7 (4.6) | 6 (4.0) | |

| ≥31 | 42 (29.2) | 63 (43.8) | 14 (9.7) | 18 (12.5) | 7 (4.9) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.475 | |||||

| Male | 45 (34.9) | 51 (39.5) | 20 (15.5) | 9 (7.0) | 4 (3.1) | |

| Female | 69 (35.2) | 83 (42.3) | 18 (9.2) | 17 (8.7) | 9 (4.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.016 | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 52 (31.5) | 71 (43.0) | 14 (8.5) | 20 (12.1) | 8 (4.8) | |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 62 (38.8) | 63 (39.4) | 24 (15.0) | 6 (3.8) | 5 (3.1) | |

| Have children, n (%) | 0.002 | |||||

| No | 79 (40.5) | 74 (37.9) | 27 (13.8) | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.6) | |

| One or more | 35 (26.9) | 60 (46.2) | 11 (8.5) | 18 (13.8) | 6 (4.6) | |

| Income (CN¥ per month), n (%) | 0.982 | |||||

| ≤3,000 | 69 (37.5) | 72 (39.1) | 25 (13.6) | 11 (6.0) | 7 (3.8) | |

| 3,001–5,000 | 13 (43.3) | 10 (33.3) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10.0) | |

| ≥5,001 | 32 (28.8) | 52 (46.8) | 11 (9.9) | 13 (11.7) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment, n (%) | 0.021 | |||||

| No | 68 (42.5) | 57 (35.6) | 21 (13.1) | 8 (5.0) | 6 (3.8) | |

| Yes | 46 (27.9) | 77 (46.7) | 17 (10.3) | 18 (10.9) | 7 (4.2) | |

| Clinical doctoral students, n (%) | 0.221 | |||||

| No | 74 (38.3) | 79 (40.9) | 23 (11.9) | 12 (6.2) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Yes | 40 (30.3) | 55 (41.7) | 15 (11.4) | 14 (10.6) | 8 (6.0) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.040 | |||||

| First year | 37 (52.1) | 20 (28.2) | 10 (14.1) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Second year | 42 (34.7) | 54 (44.6) | 11 (9.1) | 9 (7.4) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Third year | 32 (27.6) | 53 (45.7) | 14 (12.1) | 13 (11.2) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Fourth year or above | 3 (17.6) | 7 (41.2) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor, n (%) | 0.090 | |||||

| At least once a week | 79 (40.9) | 78 (40.4) | 20 (10.4) | 10 (5.2) | 6 (3.1) | |

| At least once a month | 25 (28.7) | 38 (43.7) | 10 (11.5) | 9 (10.3) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Seldom | 10 (22.2) | 18 (40.0) | 8 (17.8) | 7 (15.6) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| A little bit of effort | 33 (58.9) | 19 (33.9) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.4) | 0 | |

| Some effort | 52 (35.1) | 66 (44.6) | 19 (12.8) | 6 (4.1) | 5 (3.4) | |

| A lot of effort | 29 (24.0) | 49 (40.5) | 18 (14.9) | 17 (14.0) | 8 (6.6) | |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program, n (%) | 0.001 | |||||

| Almost none | 51 (52.0) | 35 (35.7) | 7 (7.1) | 4 (4.1) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Some | 36 (28.6) | 59 (46.8) | 18 (14.3) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (4.0) | |

| Great | 27 (26.7) | 40 (39.6) | 13 (12.9) | 14 (13.9) | 7 (6.9) | |

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by anxiety (n=325)

| Characteristics | Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None–minimal (n=151) | Mild (n=109) | Moderate (n=42) | Severe (n=23) | -value | |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.114 | ||||

| ≤25 | 18 (60.0) | 9 (30.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0 | |

| 26–30 | 68 (45.0) | 55 (36.4) | 19 (12.6) | 9 (6.0) | |

| ≥31 | 65 (45.1) | 45 (31.3) | 20 (13.9) | 14 (9.7) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.801 | ||||

| Male | 61 (47.3) | 41 (31.8) | 19 (14.7) | 8 (6.2) | |

| Female | 90 (45.9) | 68 (34.7) | 23 (11.7) | 15 (7.7) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.249 | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 74 (44.8) | 52 (31.5) | 23 (13.9) | 16 (9.7) | |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 77 (48.1) | 57 (35.6) | 19 (11.9) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Have children, n (%) | 0.265 | ||||

| No | 95 (48.7) | 68 (34.9) | 21 (10.8) | 11 (5.6) | |

| One or more | 56 (43.1) | 41 (31.5) | 21 (16.2) | 12 (9.2) | |

| Income (CN¥ per month), n (%) | 0.883 | ||||

| ≤3,000 | 87 (47.3) | 61 (33.2) | 25 (13.6) | 11 (6.0) | |

| 3,001–5,000 | 13 (43.3) | 10 (33.3) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | |

| ≥5,001 | 51 (45.9) | 38 (34.2) | 14 (12.6) | 8 (7.2) | |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment, n (%) | 0.429 | ||||

| No | 79 (49.4) | 54 (33.8) | 19 (11.9) | 8 (5.0) | |

| Yes | 72 (43.6) | 55 (33.3) | 23 (13.9) | 15 (9.1) | |

| Clinical doctoral students, n (%) | 0.030 | ||||

| No | 97 (50.3) | 67 (34.7) | 21 (10.9) | 8 (4.1) | |

| Yes | 54 (40.9) | 42 (31.8) | 21 (15.9) | 15 (11.4) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.525 | ||||

| First year | 41 (57.7) | 19 (26.7) | 8 (11.3) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Second year | 54 (44.6) | 43 (35.5) | 14 (11.6) | 10 (8.3) | |

| Third year | 49 (42.2) | 43 (37.1) | 16 (13.8) | 8 (6.9) | |

| Fourth year or above | 7 (41.2) | 4 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor, n (%) | 0.017 | ||||

| At least once a week | 106 (54.9) | 58 (30.1) | 19 (9.8) | 10 (5.2) | |

| At least once a month | 28 (32.2) | 34 (39.1) | 16 (18.4) | 9 (10.3) | |

| Seldom | 17 (37.8) | 17 (37.8) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (8.9) | |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| A little bit of effort | 36 (64.3) | 17 (30.4) | 3 (5.4) | 0 | |

| Some effort | 73 (49.3) | 54 (36.5) | 14 (9.5) | 7 (4.7) | |

| A lot of effort | 42 (34.7) | 38 (31.4) | 25 (20.7) | 16 (13.2) | |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program (n,%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Almost none | 58 (59.2) | 30 (30.6) | 9 (9.2) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Some | 58 (46.0) | 45 (35.7) | 16 (12.7) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Great | 35 (34.7) | 34 (33.7) | 17 (16.8) | 15 (14.9) | |

Means and correlations among age and PHQ-9, GAD-7, AWAI-S, and RSES scores

Mean scores for the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and AWAI-S and their correlations with each other and age are presented in Table 4 . Age was positively associated with the PHQ-9. However, there was no significant effect of age on the GAD-7. Both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores were negatively associated with AWAI-S and RSES scores.

Correlations among age, AWAI-S, RSES, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 scores

| Continuous variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.09 | 5.27 | 1 | ||||

| AWAI-S | 113.9 | 18.53 | −0.046 | 1 | |||

| RSES | 329.8 | 68.74 | −0.153 | 0.300 | 1 | ||

| PHQ-9 | 7.32 | 5.92 | 0.110 | −0.328 | −0.293 | 1 | |

| GAD-7 | 5.85 | 5.44 | 0.061 | −0.311 | −0.325 | 0.880 | 1 |

Abbreviations: AWAI-S, Advisory Working Alliance Inventory-student version; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; RSES, Research Self-Efficacy Scale.

Associations of mentoring relationship and research self-efficacy with depression/anxiety

As shown in Tables 5 and and6, 6 , sociodemographic and doctoral variables contributed to 17.7% of the variance in PHQ-9 scores and to 18.3% of the variance in GAD-7 scores. Doctoral students in their fourth year had greater PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores than first-year doctoral students. Compared with those who met with their mentors at least once a week, doctoral students who met with their mentors only once a month had higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores. Moreover, respondents who reported that they had to try their best to publish doctoral qualification papers had higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores than those who felt they only had to put forth a little effort. Finally, doctoral students who had great difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program exhibited a higher level of depression and anxiety than those who had almost no difficulty.

Factors related to depression using hierarchical regression analysis

| Controlled, dependent and mediating variables in the three Step Regression | PHQ-9 scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 (b) | Step 2 (b) | Step 3 (b) | |

| Age (years) | −0.105 | −0.078 | −0.098 |

| Have children | 0.035 | 0.044 | 0.112 |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment | −0.024 | −0.071 | −0.080 |

| Clinical doctoral students | 0.067 | 0.042 | 0.063 |

| Grade | |||

| Second year vs first year | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.011 |

| Third year vs first year | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.008 |

| Fourth year or above vs first year | 0.136 | 0.147 | 0.129 |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor | |||

| At least once a month vs at least once a week | 0.133 | 0.121 | 0.118 |

| Seldom vs at least once a week | 0.119 | 0.093 | 0.049 |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper | |||

| Some effort vs a little bit of effort | 0.141 | 0.130 | 0.084 |

| A lot of effort vs a little bit of effort | 0.325 | 0.276 | 0.265 |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program | |||

| Some vs almost none | 0.161 | 0.141 | 0.118 |

| Great vs almost none | 0.256 | 0.231 | 0.195 |

| RSES | −0.211 | −0.136 | |

| AWAI-S | −0.257 | ||

| 5.054 | 5.958 | 7.419 | |

| Adjusted | 0.142 | 0.179 | 0.232 |

| ∆ | 0.177 | 0.038 | 0.053 |

Abbreviation: PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Factors related to anxiety using hierarchical regression analysis

| Controlled, dependent and mediating variables in the three Step Regression | GAD-7 scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 (b) | Step 2 (b) | Step 3 (b) | |

| Age (years) | −0.170 | −0.139 | −0.158 |

| Have children | −0.003 | 0.007 | 0.072 |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment | 0.008 | −0.046 | −0.055 |

| Clinical doctoral students | 0.107 | 0.078 | 0.099 |

| Grade | |||

| Second year vs first year | 0.007 | 0.015 | −0.003 |

| Third year vs first year | 0.011 | 0.009 | −0.024 |

| Fourth year or above vs first year | 0.129 | 0.142 | 0.125 |

| Frequency of meeting mentor | |||

| At least once a month vs at least once a week | 0.163 | 0.150 | 0.147 |

| Seldom vs at least once a week | 0.091 | 0.060 | 0.018 |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper | |||

| Some effort vs a little bit of effort | 0.128 | 0.115 | 0.072 |

| A lot of effort vs a little bit of effort | 0.314 | 0.258 | 0.247 |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program | |||

| Some vs almost none | 0.151 | 0.128 | 0.107 |

| Great vs almost none | 0.288 | 0.260 | 0.225 |

| RSES | −0.242 | −0.170 | |

| AWAI-S | −0.246 | ||

| 5.262 | 6.614 | 7.940 | |

| Adjusted | 0.148 | 0.198 | 0.247 |

| ∆ | 0.183 | 0.050 | 0.049 |

Abbreviation: GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

After adjustment for controlled variables, the RSES was negatively associated with depression ( b =−0.211, P <0.001) and anxiety ( b =−0.242, P <0.001), and accounted for 3.8% of the variance for depression and 5.0% of the variance for anxiety. In step 3, the AWAI-S was negatively associated with depression ( b =−0.257, P <0.001) and anxiety ( b =−0.246, P <0.001), and accounted for 5.3% of the variance for depression and 4.9% of the variance for anxiety. In step 3, when the AWAI-S was added, the absolute value of RSES b was diminished. Therefore, the AWAI-S might be a mediator in the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

Mediating role of mentoring relationship