Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

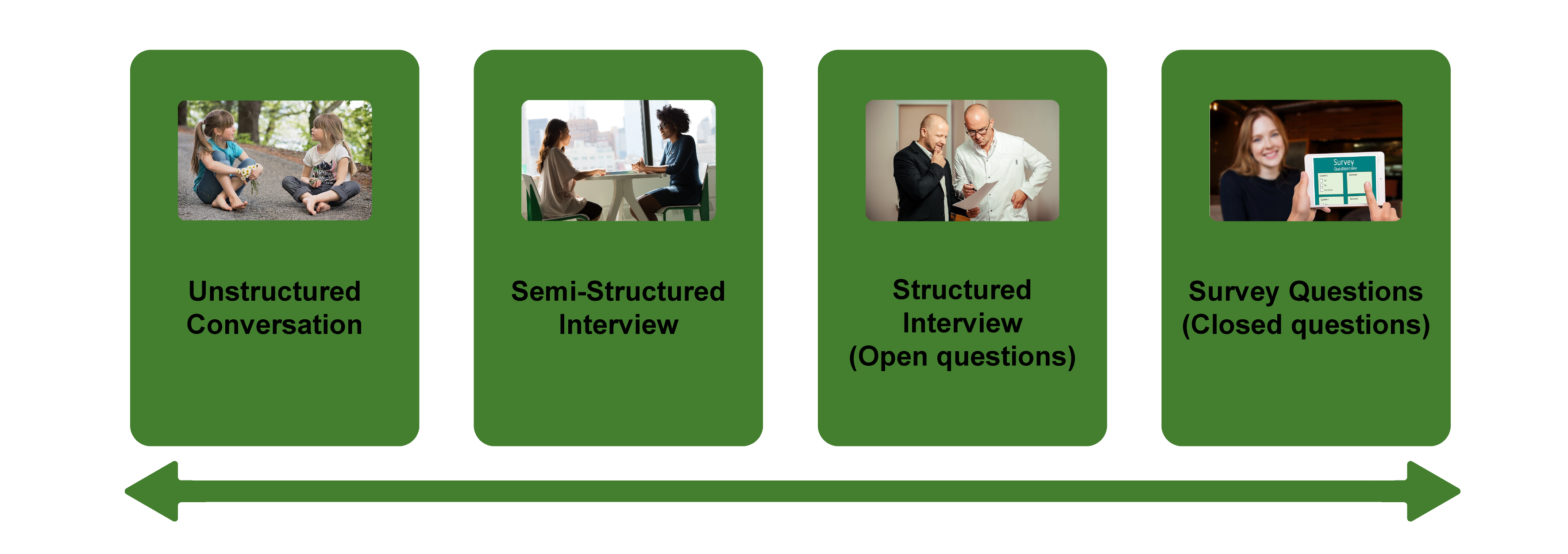

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

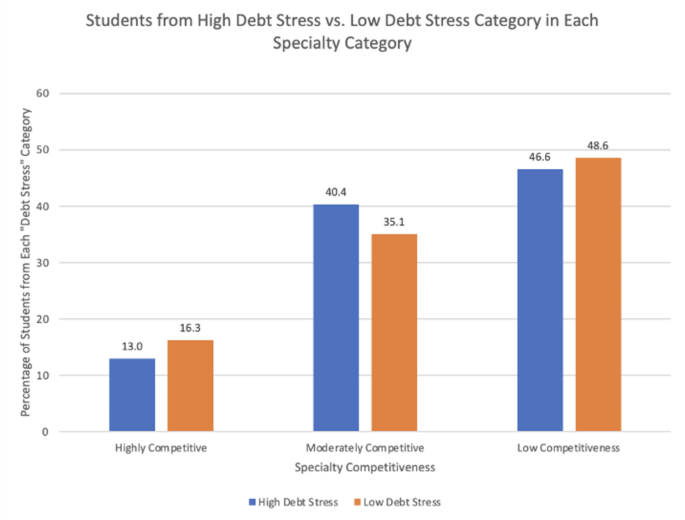

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on March 10, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure.

- Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order.

- Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing.

- Semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research .

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate research biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyze because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered “the best of both worlds.”

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalizability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualize your initial hypotheses.

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions.

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behavior, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large surveys . However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to “cherry-pick” responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic.

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no.”

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas.

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilize this research method.

| Type of interview | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Structured interview | ||

| Semi-structured interview | , , , and | |

| Unstructured interview | , , , and | |

| Focus group | , , and , since there are multiple people present |

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/interviews-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, semi-structured interview | definition, guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

A comprehensive guide to in-depth interviews (IDIs)

UserTesting

You might have user data. But do you fully understand the why behind the data? Do you know who they are as people? If the answer is no, you're not alone.

A 2019 study found that more than half of researchers would like to use more in-person interviews as a UX research method . The good news? Most people are actually willing to give you their undivided attention to actively improve your app, site, or service user experience. As a UX researcher, you’re sitting on a potential goldmine of information and insights from your customer base.

To pull that insightful data from participants, you’ll need to conduct in-depth interviews (IDIs) . These interviews require more planning and resources than other data collection methods. You’re also asking for more of your user’s time.

For those reasons, it's essential to ensure you go into the process with a clear idea of what data you hope to get out of one.

What is an in-depth interview?

An in-depth interview is a qualitative research technique that involves conducting multiple individual interviews. They involve one-on-one engagement with participants, usually taking place face-to-face, either remotely or in-person.

Unlike other research methods, in-depth interviews have a more flexible structure than moderated usability studies .

IDIs are used to get a more detailed and well-rounded perspective of users’ opinions, experiences, and feelings about a product's UX.

Instead of more general qualitative or quantitative questionnaires that are sent out to a larger group of customers, IDI questions can be tailored to the interviewee and their individual usage.

In these more intensive interviews, organizations usually ask a smaller number of customers to take part. This means that responses to different ideas, features, services, or future plans are more deeply investigated.

You could consider using in-depth interviews for the following reasons:

- To get feedback on a new product or service your business has launched

- As a way of understanding the needs and expectations of your customers during persona gathering sessions

- For coming up with new ideas on how customers would make improvements to an existing product or service

- Following a usability study to better understand how users intend to use your platform

- To get insight into how a customer thinks about design elements on certain pages

As you can see, they’re most effective when used in combination with other research methods like online surveys and usability testing .

Why are in-depth interviews important?

There’s a large gap between the consumer's experience of brands and the marketer's confidence in their own branding. While most marketers are confident they can meet their target market's level of expectation, just under half of consumers say brands fail to meet their expectations.

Most users will switch to a competitor if they have just one bad experience with a brand they typically like.

What does this mean? To put it simply: creating a positive user experience is key for encouraging people to interact with your app, service, or site.

In-depth interviews are one way of bridging this gap between consumer experience and business confidence. You can get insight into a users’ thoughts and feelings—and use that qualitative data to improve design, product launches, and key messaging.

What are the benefits of performing in-depth interviews?

IDIs should show you how users feel about specific elements of your UX. They can also help you gain confidence in making future decisions.

Here are a few of the top benefits of using IDIs in your UX process.

Smaller sample size

Given the higher quality relevant insights, researchers require fewer participants to take part in in-depth interviews.

Lower drop-off rates mean that interviewers can conduct fewer IDIs and still collect rich data. For instance, online questionnaires have a higher drop-off rate, so they require a larger sampling. But with IDIs, you can get a lot of data from each individual participant.

Get honest feedback

One-on-one in-depth interviews are free from possible peer-pressure dynamics or distractions that are sometimes present in larger focus groups . By taking an hour to chat with a participant directly, the two-way conversation leaves zero space for other users’ influence.

Some people may also feel more comfortable providing honest feedback in conversation instead of through a written questionnaire.

Gain a deeper understanding of user behavior

Face-to-face in-depth interviews, whether remote or in-person, allow researchers to interpret body language . Interviewers can also analyze changes in tone of voice and word choice.

These nuances help interviewers build a complete picture of user behavior that isn’t possible through other online or offline feedback channels.

Build a stronger understanding of user expectations and motivations

It’s easier to ask follow-up questions, request more detailed information, and explore particular topics in more depth with an IDI. They’re suited to asking open-ended questions that encourage longer and more detailed responses from the participant.

As a researcher, you should take advantage of having participants’ undivided attention. Take the time to explore their opinions more deeply, beyond the surface level, for the most useful qualitative data .

What are the challenges?

IDIs can give you valuable insight into users’ expectations and actual uses of your site. But, there are some challenges.

They’re time-consuming

Every interview you conduct will need to be transcribed, analyzed, organized, and properly stored. Multiple team members may need to be involved in the process.

While often more informative, IDIs require more time and preparation than other research methods—including simple written surveys.

Interviewers or moderators require thorough training and briefing

You need skilled interviewers to ask the right research questions and properly engage with participants to obtain valuable insights.

Successful IDIs depend on an interviewer's ability to ask thoughtful questions at the right time. They need to give the participants space to think and talk—while making them feel comfortable enough to do so. It takes training for an interviewer to hone in on this skill set.

Participants require careful vetting

To gather valuable and balanced insights, it’s essential to use random sampling to gather a group of participants that accurately represent your organization’s user base. Once you have a random set of participants, you should check that they represent your user base’s different groups.

Depending on the size of your customer base, it likely won’t be possible to interview all your customers. That being said, it's important to interview a variety of different users.

For instance, you may want to interview a group of users who are unfamiliar with your site design, those who have been using your site for six months, and another group who left for a competitor.

The best way to do this would be to segment your customer base , then randomly generate a sample of participants to invite to an IDI.

How do you structure IDIs?

When it comes to how structured your IDIs are, you have several options:

- Structured interviews are fixed in their methodology. The interviewer would only ask predetermined questions and target specific experiences. A structured approach limits the scope for exploring discussed topics in more depth.

- Unstructured interviews aren’t defined and don’t include pre-planned questions. It’s more like a conversation between the researcher and the respondent.

- Semi-structured interviews follow some protocols to guide the process. While it’s a conversation between two individuals, and the interviewer can ask for more details, most of the questions are scripted. Interviewers will plan some initial questions and themes to cover, but allow the respondents’ answers to guide the interview direction.

Generally, the most valuable in-depth interviews are semi-structured.

These IDIs have a loose structure, but remain adaptable to the participant’s issues and ideas. This flexibility enables interviewers to explore each response fully and better engage with the user.

When to use unstructured interviews: "If you’re at the beginning of a design phase, just trying to path-find for innovation, or trying to really dig into another layer of how your users use your product, that's when you're going to want to be more unstructured. When you've already got the product or the prototype, and you're wanting to validate, and you want to make sure that you're designing it the right way." - Julie Strubel, UserZoom Senior UX Researcher

How do you conduct a good in-depth interview?

Some preparation is key for conducting an insightful in-depth interview. Planning topics and conversation starters in advance will help you use your participants’ time more wisely. If your customers feel that their time was wasted or the IDI was simply too long, they may be reluctant to participate in future drives for customer insights.

Keeping your IDIs brief and well-structured will also help your participants maintain focus until the end. Longer interviews with less clear objectives run the risk of tiring customers out and reducing the quality of their answers.

In addition to the tips we just mentioned, we've pulled together 9 best practices to keep in mind when you're running IDIs:

- Know your aims

- Define your scope

- Set a time limit

- Ask the right questions

- Remove bias

- Make questions actionable

- Test your questions

- Create an IDI guide

- Put your insights into action

1. Know your aims

Before you plan on conducting any in-depth interviews, it’s important to know what you’re aiming to get out of the process. This helps guide your questions—and ultimately, the conversation.

Perhaps you’re looking to understand how customers feel about your site’s new design. In that case, you need to ask open-ended questions like, “What do you think of our new site design when compared to our previous version?”

If you want to find out if participants find your checkout page to be intuitive, ask questions like, “How did you feel about the navigation experience of our checkout page?”

When you identify your goals , it’ll be easier to plan questions to help build your understanding of what your end-user is looking to achieve.

For this reason, Hector Harris-Burton of Imaginaire recommends having some structure.

“Have a loose structure so that you can cover topics that you'd like to hear about. While an IDI is supposed to be a freeform conversation, one of the best ways to get the most information out of the interviewee is to ensure that you have talking points and some kind of structure. By having a structure, not only are you able to cover the topics you need, but you can also aid the conversation. No matter who you talk to, there is always the potential for the conversation to run dry. But with a structure and talking points, you're able to lead the conversation and move forward, rather than struggling.”

2. Define your scope

Always clarify the extent of your research before you begin interviewing people.

Decide how much time you have to spend on conducting IDIs, and the minimum number of respondents you need to consider any themes as standard. That should define the number of users you need to interview.

There’s no magic number when it comes to determining the size of your sample . Always prioritize quality over quantity, and check that you can spend a reasonable amount of time in each interview.

For instance, there’s not much point in interviewing 120 people for five minutes each. It would be better to spend the same amount of time interviewing 20 people for 30 minutes each. That way, you’d have time to explore topics more deeply with each participant instead of rushing through a list of questions.

3. Set a time limit

When conducting an IDI, make sure you’re mindful of your participants’ time. Remember: their answer quality may drop off towards the end of the conversation if you’ve been talking for hours.

Let participants know how much time each interview will take and stick to it.

Keeping each interview to a maximum of one hour will allow you to ask participants plenty of questions without going off-topic. It’s also short enough for them to commit to the interview.

4. Ask the right questions

Asking the right questions will encourage respondents to share their honest points of view.

In your in-depth interviews, add in a mix of question types, such as:

- General ice-breaking questions. Ease people into the discussion by asking light-hearted questions first. For example, “Tell me about your biggest challenges right now.”

- More specific detail-oriented questions. Start to explore subjects that are more closely linked to your research goals. For instance, “What are you hoping to achieve by using our app?”

- Insight-based questions. Ask more specific questions about existing or new features. Use your last questions to find out how users feel about your future plans. For example, “How useful would this new calendar function be for you?”

Using the right questions will help you better listen to users and then effectively implement their feedback. You’ll also gather qualitative data that helps you make smarter UX decisions.

5. Remove bias

It’s easy to accidentally influence customers’ answers without intending to. Take care with how you phrase each of your questions to make sure you’re not accidentally influencing their responses.

Consider the following question: “What do you like about this new service?”

The phrasing of the question restricts users to only talking about what they like about the service as opposed to providing a more balanced answer.

To make the question more neutral and bias-free , ask something along the lines of: “What do you think about our new service?”

This simple change of phrasing leaves the customer free to provide an honest perspective (as opposed to just listing what they like about the service).

The key is to collect valuable, actionable feedback that isn’t shaped by your organization’s expectations or agenda. So, always ask users open-ended questions and avoid leading questions that influence participants’ answers.

Read up on other examples of leading questions so you know what to avoid.

Don't ask them leading questions designed to elicit a certain response. You want them to answer truthfully, so it's best to ask questions straight up and don't suggest an answer. For example, avoid questions like “What do you think is helpful in the new package we offered? The new payment methods?” Ask open-ended questions that will lead to expansive responses. Remember, you want to find out what they are trying to do and what their problems are. - Lauri Kinkar, Messente CEO

6. Make questions actionable

When conducting IDIs, only ask users questions that are actionable. That way, you’ll be able to directly use their answers to improve user experience.

Here’s an example of an actionable question: “Is there anything you would change about our checkout page?” Any answers you receive to this question will improve your current page based on users’ current sentiment around it.

If you’re in doubt about asking a particular question, think about whether you could use the answer to improve your UX. If you can’t find a way of using the response to improve your user experience, it’s best to ask another question.

7. Test your interview questions

Test your questions on teammates and ask for feedback on whether your questions are straightforward.

Do they give the answers you were expecting? Or bounce the questions back to you, asking what you meant?

Your users’ responses should give you a clear idea of what needs to be changed or improved moving forwards.

8. Create an IDI guide

IDI guides are an informative document that outlines the interview process from start to finish.

It should act as a to-do list that you refer to throughout the interview process, as UX Specialist Andreas Johansson explains:

"As part of the user research plan, I also create an interview guide. This is basically a rough structure for me to refer to when I do the interviews. I tend to do semi-structured interviews. That means that I refer to the interview guide if I get stuck, but I don't tend to be too rigid about it. Sometimes it's good if the discussions go off on a tangent, for instance."

First, state your objectives and then outline the general flow of the interview. Include all the topics you want to talk about and in what order—remembering why you’re asking them in the first place.

This interview guide will stop you from getting side-tracked during the conversation, helping you create the best possible experience for your participants.

Consider giving your colleagues a copy of the IDI guide, too. They can provide you with feedback on what you’re planning to ask. Knowing what insights you’re planning to pull will also help them anticipate the data they’ll later analyze and store.

9. Put your insights into action

It’s all well and good to have a jam-packed day of IDIs. Once you’ve collected that data, though, you need to turn it into actionable insights.

Olga Kimalana, Senior Conversion Strategist at Scandiweb, explains:

“There’s no point in conducting user interviews if you don’t act upon the insights you gathered, so make sure to present your insights and plans of action to stakeholders to kick off the improvements.”

The simplest way to do this is to listen back through each interview. Create a transcription of the conversion, and flag different parts of the conversation that are interesting. This can include snippets you want to re-listen or pay closer attention to.

We recommend using a professional UX platform (instead of Zoom or Google Meet) for this reason. UserTesting, for example, has a note-taking feature. You can annotate transcripts, and add hashtags to certain topics, to spot themes across several IDIs.

Five in-depth interview best practices

Following a few best practices will ensure you make the most of each interview and collect data for improving your UX. Here are five to start with.

1. Ensure participants feel comfortable

In-depth interviews are voluntary, so it’s important to make customers feel comfortable enough to share their honest opinions.

As an interviewer, you should approach each interview with an approachable, friendly, and open-minded attitude. Avoid making the interview feel too formal–you don’t want users to feel under pressure or stressed.

"You're setting the stage, you want people to feel relaxed. Even if they're just going through and doing a talk-out-loud for a usability session, you want to put them at ease, and that's not just about reading the script. It's about making that human connection in the first three minutes." - Julie Strubel, UserZoom Senior UX Researcher

If customers have a positive experience during your interview, they’ll be more likely to readily offer feedback if you request it again in the future. You’ll also get better data from respondents who were genuinely interested in the conversation.

2. Properly engage with your interviewees

Effectively engaging with interviewees is sometimes easier said than done—especially when you have a busy day full of in-depth interviews.

Taking detailed notes may distract you from what your customer is saying or take you out of the moment, so you may want to use an audio or video recording device instead. That way, you can give your interviewee 100% of your attention and remain responsive to their answers.

Making recordings of each interview will enable you to fully engage with participants without worrying about forgetting critical data or insights later on. Simply refer to your recordings afterward and collect all of the relevant insights.

3. Follow-up on user responses

It’s vital to understand what your customers mean by their responses and what’s behind their opinion of your app, site, or service. Try clarifying their responses by summarizing their thoughts. If you’re not sure, always ask for clarification.

Whenever users share an opinion, follow-up on their response by asking why they feel the way they do.

For instance, if a participant says they don’t find your checkout page intuitive, you should follow-up by asking them what it is that they don’t find user-friendly. Is it the layout? Are the payment instructions unclear? Do they have to click on too many buttons?

Avoid putting words into participants’ mouths, but make sure to find out what it is precisely about the page they find unintuitive.

Alternatively, if a user says they prefer your old site design, make sure to pinpoint why. Was there a specific menu flow they found easy to use? Was the search capability stronger?

Asking why will help you go beyond surface-level responses and genuinely engage with your customer base.

4. Provide consent forms

You should always provide your participants with consent forms that outline the purpose of the interview.

To legally use the participants’ responses and details, you need to make sure that everyone signs an agreement as to how the information gathered from the interview will be used.

Consent always needs to be:

- Based on clearly explained information. Participants need to know what exactly is being researched. Provide a detailed information sheet for them to read before signing.