How to Write a Critical Thinking Essay: Steps & Example

Critical thinking is a powerful skill that helps you analyze information and form well-reasoned arguments. As a matter of fact, the human brain uses more energy when critically thinking than when relaxing. This article will guide you through the steps of writing a successful critical thinking essay.

In this article, you will learn:

- How to craft a strong essay

- The importance of these essays

- The structure with an example

- Valuable bonus tips to strengthen your writing

By following these steps and incorporating the provided information, you'll be well on your way to writing impressive essays. If you need further guidance, always count on our fast essay writing service .

What is Critical Thinking Essay

A critical thinking essay is a type of writing where you analyze a topic thoroughly. You'll consider different viewpoints, evaluate evidence from studies or expert opinions, and form your own well-reasoned conclusion. Here, you need to look at an issue from all angles before deciding where you stand. This type of essay goes beyond memorizing facts. It actively engages with information, questions assumptions, and develops your own thoughtful perspective.

Is Your Essay Giving You a Headache?

Don't call an ambulance; call EssayPro! Let our experts conquer any of your assignments!

Importance of Critical Thinking and Its Use in Writing

Critical thinking is a skill that benefits all types of writing, not just essays. It helps you become a more informed and effective communicator. Here's why it's important:

- Stronger Arguments: Critical thinking helps you build solid arguments. You won't just state your opinion but back it up with evidence and consider opposing viewpoints. This makes your writing more persuasive and convincing.

- Deeper Understanding: When writing a critical thinking essay, you'll analyze information, identify biases, and think about the bigger picture. This leads to a richer understanding of the topic and a more insightful essay.

- Clearer Communication: By organizing your thoughts critically, your writing becomes clearer and more focused. You'll present your ideas in a logical order, making it easier for readers to follow your argument.

- Spotting Fake News: Critical thinking skills help you evaluate the information you encounter online and in the world around you. You'll be better equipped to identify unreliable sources and biased information, making you a more discerning reader and writer.

- Improved Problem-Solving: Critical thinking helps you approach challenges thoughtfully. As you write, you'll learn to analyze complex issues, consider different solutions, and ultimately develop well-reasoned conclusions. This skill extends beyond writing and can be applied to all areas of your life.

For more detailed information on the importance of critical thinking , visit our dedicated article.

Critical Thinking Essay Format

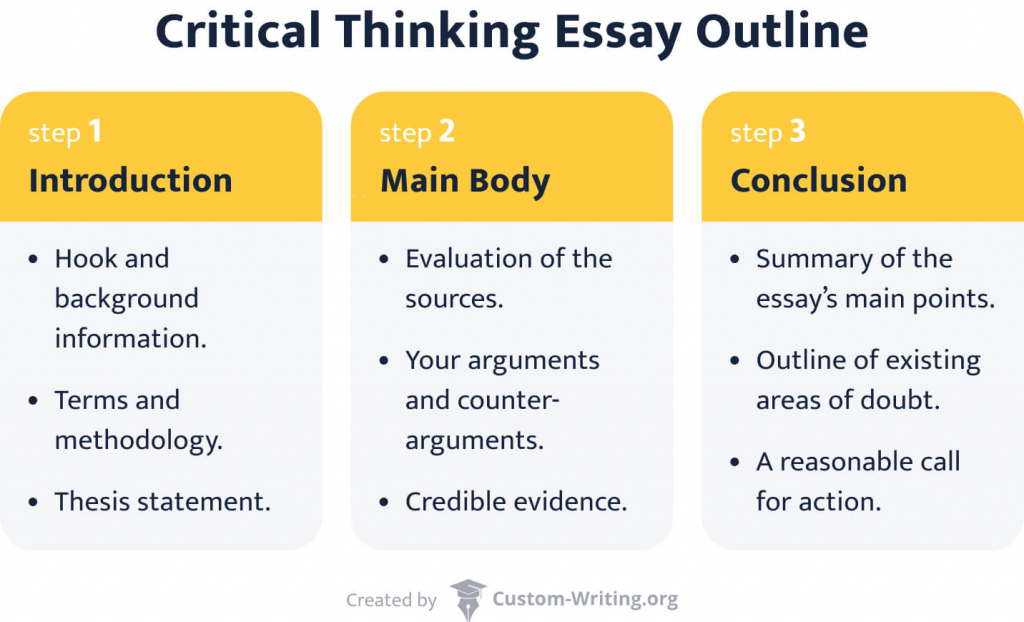

In a critical thinking essay outline, each piece has its place and contributes to the overall picture. Here's a breakdown of the key components:

| Element 🔍 | Content 📝 |

|---|---|

| 1. Title | Should be concise and reflective of your essay's content. |

| 2. Introduction | Introduce the topic's importance. Clearly state your main argument. |

| 3. Body Paragraphs | Each paragraph supports your thesis. Use credible sources for support. Connect evidence and analyze. Address opposing views. |

| 4. Conclusion | Briefly recap the key points. Restate your thesis, highlighting its significance. Leave a final thought or call to action. |

| 5. References/Bibliography | This section lists all your cited sources. Format them in a citation style like APA, MLA, or Chicago to credit original authors. |

Check out our critical analysis example to see how this format comes to life.

Critical Thinking Essay Questions

Now that you understand the structure of this essay, let's get your brain working! Here are some questions to help you generate strong critical thinking essay topics:

- How can you tell if a source of information is reliable?

- What are the potential biases that might influence research or news articles?

- How can you identify logical fallacies in arguments?

- How can you weigh the pros and cons of a complex issue?

- How can your own experiences or background influence your perspective on a topic?

Sample Essay Topics:

- History: Should historical monuments that celebrate controversial figures be removed or repurposed?

- Science: With advancements in gene editing, should we allow parents to choose their children's traits?

- Art & Culture: Does artificial intelligence pose a threat to the creativity and value of human art?

- Space Exploration: Should we prioritize colonizing Mars or focus on solving problems on Earth?

- Business Ethics: Is it ethical for companies to automate jobs and potentially displace workers?

- Education: In a world with readily available information online, is traditional classroom learning still necessary?

- Global Issues: Is focusing solely on national interests hindering efforts to address global challenges like climate change?

Remember, these are just a few ideas to get you started. Choose a topic that interests you and allows you to explore different perspectives critically.

How to Write a Critical Thinking Essay

We've covered the foundation – the structure and key elements of a critical thinking essay. Now, let's dive into the writing process itself! Remember, the steps on how to start a critical thinking essay, such as defining your topic, crafting a thesis, gathering evidence, etc., are all interconnected. As you write, you'll move back and forth between them to refine your argument and build a strong essay.

If you're looking for a hassle-free solution, simply buy cheap argumentative essay from our experts.

.webp)

Understand the Assignment Requirements

Taking some time to understand the assignment from the beginning will save you time and frustration later. Grasping your critical thinking paper instructions ensures you're on the right track and meeting your teacher's expectations. Here's what to focus on:

- The Prompt: This is the core of the assignment, outlining the topic and what you're expected to do. For example, if it asks what critical thinking skills are, Look for keywords like "define," "describe," or "explain." These indicate the type of essay you need to write and the approach you should take.

- Specific Requirements: Pay attention to details like the essay length, formatting style (e.g., MLA, APA), and any specific sources you need to use. Missing these guidelines can lead to point deductions.

- Grading Rubric (if provided): This is a goldmine! The rubric often outlines the criteria your essay will be graded on, like clarity of argument, use of evidence, and proper citation style. Knowing these expectations can help you tailor your writing to excel.

Select a Critical Thinking Topic

Think about the prompt or theme provided by your teacher. Are there any aspects that pique your interest? Perhaps a specific angle you haven't explored much? The best topics are those that spark your curiosity and allow you to engage with the material in a meaningful way.

Here are some tips for selecting a strong critical thinking essay topic:

- Relevance to the Assignment: Make sure your chosen topic directly relates to the prompt and allows you to address the key points. Don't stray too far off course!

- Interest and Engagement: Choose a topic that you find genuinely interesting. Your enthusiasm will show in your writing and make the research and writing process more enjoyable.

- Complexity and Scope: Aim for a topic that's complex enough to provide depth for analysis but not so broad that it becomes overwhelming. You want to be able to explore it thoroughly within the essay's length limitations.

- Availability of Sources: Ensure you have access to credible sources like academic journals, news articles from reputable sources, or books by experts to support your argument.

Remember: Don't be afraid to get creative! While some prompts may seem broad, there's often room to explore a specific angle or sub-topic within the larger theme.

Conduct In-Depth Research

This is where you'll gather the information and evidence when writing a critical thinking essay. However, don't just copy information passively. Critically analyze the sources you find.

- Start with Reliable Sources: Steer clear of unreliable websites or questionable information. Focus on credible sources like academic journals, scholarly articles, reputable news outlets, and books by established experts in the field.

- Use Library Resources: Librarians can guide you towards relevant databases, academic journals, and credible online resources.

- Search Engines Can Be Your Friend: While you shouldn't rely solely on search engines, they can be helpful starting points. Use keywords related to your topic, and be critical of the websites you visit. Look for sites with a clear "About Us" section and reputable affiliations.

- Vary Your Sources: Don't just rely on one type of source. Seek out a variety of perspectives, including research studies, data, historical documents, and even opposing viewpoints. This will give your essay well-roundedness and depth.

Develop a Strong Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement encapsulates your main argument or perspective on the topic. A strong thesis statement tells your readers exactly what your essay will be about and prepares them for the evidence you'll present.

During your critical thinking process, make sure you include these key characteristics:

- Specificity: It goes beyond simply stating the topic and clearly outlines your position on it.

- Focus: It focuses on a single main point that you'll develop throughout the essay.

- Argumentative: It indicates your stance on the issue, not just a neutral observation.

- Clarity: It's clear, concise, and easy for the reader to understand.

For example, here's a weak thesis statement:

Deepfakes are a new technology with both positive and negative implications.

This is too vague and doesn't tell us anything specific about ethics. Here's a stronger version:

While deep lakes have the potential to revolutionize entertainment and education, their ability to create highly convincing misinformation poses a significant threat to democracy and social trust.

This thesis is specific, focused, and clearly states the argument that will be explored in the essay.

Outline the Structure of Your Essay

With a strong thesis statement guiding your way, it's time to create a roadmap for your essay. This outline will serve as a blueprint, ensuring your arguments flow logically and your essay has a clear structure. Here's what a basic outline for a critical thinking essay might look like:

| Section 📚 | Content 📝 |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Briefly introduce the topic and its significance. Clearly state your thesis statement. |

| Body Paragraphs (one for each main point) | Introduce paragraph's point and link to thesis. Use credible sources to support. Explain and analyze evidence. Address opposing views' weaknesses. |

| Conclusion | Briefly summarize the key points of your essay. Restate your thesis in a new way, emphasizing its importance. Leave your reader with a final thought or call to action (optional). |

This is a flexible structure, and you may need to adapt it based on your specific topic and the length of your essay. However, having a clear outline will help you stay organized and ensure your essay flows smoothly from point to point.

Write an Engaging Introduction

The introduction should be captivating and give your reader a taste of what's to come. Here are some tips for crafting a strong introduction:

- Start with a Hook: Use an interesting fact, a thought-provoking question, or a relevant anecdote to grab your reader's attention right from the start. This will pique their curiosity and make them want to read more.

- Introduce the Topic: Briefly introduce the topic you'll be exploring and explain its significance. Why is this topic important to discuss?

- Present Your Thesis: Clearly and concisely state your thesis statement. This tells your reader exactly what your essay will argue and prepares them for the evidence you'll present.

For example, Let's say your essay is about the growing popularity of online learning platforms. Here's an introduction that uses a hook, introduces the topic, and presents a thesis statement:

With millions of students enrolled in online courses worldwide, the way we learn is undergoing a dramatic transformation. Traditionally associated with brick-and-mortar classrooms, education is now readily available through virtual platforms, offering flexibility and accessibility. This essay will examine the advantages and challenges of online learning, ultimately arguing that while it offers valuable opportunities, it cannot entirely replace the benefits of a traditional classroom setting.

Construct Analytical Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs are the heart of your essay, where you develop your argument and convince your reader of your perspective.

- Focus on One Point Per Paragraph: Each paragraph should address a single point that directly relates to your thesis statement. Don't try to cram too much information into one paragraph.

- Start with a Topic Sentence: This sentence introduces the main point of the paragraph and explains how it connects to your thesis.

- Support with Evidence: Back up your claims with credible evidence from your research. This could include facts, statistics, quotes from experts, or relevant examples.

- Analyze and Explain: Don't just list the evidence! Use critical thinking in writing - explain how it supports your argument and analyze its significance. What does this evidence tell you about the issue?

- Consider Counterarguments (Optional): In some cases, it can be effective to acknowledge opposing viewpoints and briefly explain why they're not as strong as your argument. This demonstrates your awareness of the complexity of the issue and strengthens your own position.

For example: Let's revisit the online learning example. Imagine one of your body paragraphs focuses on the flexibility of online learning platforms. Here's a breakdown of how you might structure it:

- Topic Sentence: Online learning platforms offer students unparalleled flexibility in terms of scheduling and pace of learning.

- Evidence: A recent study by the Online Learning Consortium found that 74% of online students reported being able to manage their coursework around their work and personal commitments.

- Analysis: This flexibility allows students who may have work or family obligations to pursue their education without sacrificing other responsibilities. It also empowers students to learn at their own pace, revisiting challenging concepts or accelerating through familiar material.

Craft a Thoughtful Conclusion

The conclusion is your final opportunity to wrap up the story in a satisfying way and leave the audience with something to ponder. Here's how to write a strong conclusion for your critical thinking essay:

- Summarize Key Points: Briefly remind your reader of the main points you've discussed throughout the essay.

- Restate Your Thesis: Restate your thesis statement in a new way, emphasizing its significance.

- Final Thought or Call to Action (Optional): Leave your reader with a final thought that provokes reflection, or consider including a call to action that encourages them to take a particular stance on the issue.

Here's an example conclusion for the online learning essay:

In conclusion, while online learning platforms offer valuable flexibility and accessibility, they cannot entirely replace the benefits of a traditional classroom setting. The social interaction, real-time feedback, and personalized attention offered by in-person learning remain crucial components of a well-rounded educational experience. As technology continues to evolve, future advancements may bridge this gap, but for now, a blended approach that leverages the strengths of both online and traditional learning may be the optimal solution.

Critical Thinking Essay Example

Let's now take a look at a complete critical thinking essay to see how these steps come together. This example will show you how to structure your essay and build a strong argument.

5 Tips on How to Develop Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinking helps you form well-reasoned arguments and make sound decisions. Here are 5 tips to sharpen your critical thinking skills:

.webp)

- Question Everything (Respectfully): Don't just accept information at face value. Ask questions like "Why is this important?" "What evidence supports this claim?" or "Are there other perspectives to consider?". Develop a healthy skepticism (doubt) but be respectful of others' viewpoints.

- Dig Deeper than Headlines: In today's fast-paced world, headlines can be misleading. Go beyond the surface and seek out credible sources that provide in-depth analysis and evidence. Look for articles from reputable news organizations, academic journals, or books by established experts.

- Embrace Different Viewpoints: Exposing yourself to various perspectives strengthens your critical thinking. Read articles that present opposing viewpoints, watch documentaries that explore different sides of an issue, or engage in respectful discussions with people who hold contrasting opinions.

- Spot Logical Fallacies: Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that can lead to flawed conclusions. Learn to identify common fallacies like bandwagon appeals (appealing to popularity), ad hominem attacks (attacking the person instead of the argument), or slippery slope arguments (suggesting a small step will lead to a disastrous outcome).

- Practice Makes Progress: Critical thinking is a skill that improves with practice. Engage in activities that encourage analysis and debate. Write persuasive essays, participate in class discussions, or join a debate club. The more you exercise your critical thinking muscles, the stronger they become.

By incorporating these tips into your daily routine, you'll be well on your way to becoming a more critical thinker. Remember, keep questioning things, explore different ideas, and practice your writing!

Drowning in Research and Thesis Statements that Just Don't Click?

Don't waste another minute battling writer's block. EssayPro's expert writers are here to be your research partner!

What is an Example of Critical Thinking?

How do you start writing a critical thinking essay, how to structure a critical thinking essay.

Annie Lambert

specializes in creating authoritative content on marketing, business, and finance, with a versatile ability to handle any essay type and dissertations. With a Master’s degree in Business Administration and a passion for social issues, her writing not only educates but also inspires action. On EssayPro blog, Annie delivers detailed guides and thought-provoking discussions on pressing economic and social topics. When not writing, she’s a guest speaker at various business seminars.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

- Critical thinking and writing . (n.d.). https://studenthub.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/372818/2.-Critical-thinking-guide_FINAL.pdf

- Lane, J. (2023, September 6). Critical thinking for critical writing | SFU Library . Www.lib.sfu.ca . https://www.lib.sfu.ca/about/branches-depts/slc/writing/argumentation/critical-thinking-writing

.webp)

How to Write a Critical Thinking Essay: Examples & Outline

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating and analyzing information. People who use it in everyday life are open to different opinions. They rely on reason and logic when making conclusions about certain issues.

A critical thinking essay shows how your thoughts change as you research your topic. This type of assignment encourages you to learn rather than prove what you already know. In this article, our custom writing team will:

- explain how to write an excellent critical essay;

- introduce 30 great essay topics;

- provide a critical thinking essay example in MLA format.

- 🤔 Critical Thinking Essay Definition

- 💡 Topics & Questions

- ✅ Step-by-Step Guide

- 📑 Essay Example & Formatting Tips

- ✍️ Bonus Tips

🔍 References

🤔 what is a critical thinking essay.

A critical thinking essay is a paper that analyses an issue and reflects on it in order to develop an action plan. Unlike other essay types, it starts with a question instead of a thesis. It helps you develop a broader perspective on a specific issue. Critical writing aims at improving your analytical skills and encourages asking questions.

Critical Thinking in Writing: Importance

When we talk about critical thinking and writing, the word “critical” doesn’t have any negative connotation. It simply implies thorough investigation, evaluation, and analysis of information. Critical thinking allows students to make objective conclusions and present their ideas logically. It also helps them avoid errors in reasoning.

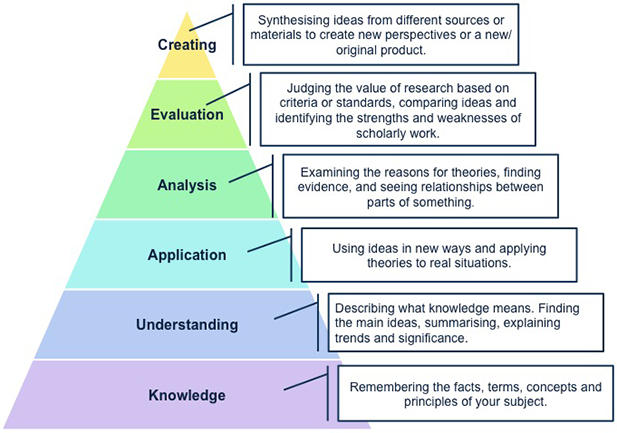

The Basics: 8 Steps of Critical Thinking Psychology

Did you know that the critical thinking process consists of 8 steps? We’ve listed them below. You can try to implement them in your everyday life:

| Identify the issue and describe it. | |

| Decide what you want to do about the problem. | |

| Find sources, analyze them, and draw necessary conclusions. | |

| Come up with creative arguments using the information you’ve gathered and your imagination. | |

| Arrange your ideas in a logical order. | |

| Evaluate your options and alternatives and choose the one you prefer. | |

| Think of how you can express your ideas to others. | |

| Defend your point of view. |

It’s possible that fallacies will occur during the process of critical thinking. Fallacies are errors in reasoning that fail to provide a reasonable conclusion. Here are some common types of fallacies:

- Generalization . It happens when you apply generally factual statements to a specific case.

- Ambiguity . It occurs when the arguments are not clear and are not supported by evidence.

- Appeal to authority . This mistake happens when you claim the statement is valid only because a respected person made it.

- Appeal to emotion . It occurs when you use highly emotive language to convince the audience. Try to stay sensible and rely on the evidence.

- Bifurcation . This mistake occurs when you choose only between two alternatives when more than two exist.

- False analogy . It happens when the examples are poorly connected.

If you want to avoid these mistakes, do the following:

- try not to draw conclusions too quickly,

- be attentive,

- carefully read through all the sources,

- avoid generalizations.

How to Demonstrate Your Critical Thinking in Writing

Critical thinking encourages you to go beyond what you know and study new perspectives. When it comes to demonstrating your critical thinking skills in writing, you can try these strategies:

- Read . Before you start writing an essay, read everything you can find on the subject you are about to cover. Focus on the critical points of your assignment.

- Research . Look up several scholarly sources and study the information in-depth.

- Evaluate . Analyze the sources and the information you’ve gathered. See whether you can disagree with the authors.

- Prove . Explain why you agree or disagree with the authors’ conclusions. Back it up with evidence.

According to Purdue University, logical essay writing is essential when you deal with academic essays. It helps you demonstrate and prove the arguments. Make sure that your paper reaches a logical conclusion.

There are several main concepts related to logic:

| ✔️ | Premise | A statement that is used as evidence in an argument. |

| ✔️ | Conclusion | A claim that follows logically from the premises. |

| ✔️ | Syllogism | A conclusion that follows from two other premises. |

| ✔️ | Argument | A statement based on logical premises. |

If you want your essay to be logical, it’s better to avoid syllogistic fallacies, which happen with certain invalid deductions. If syllogisms are used carelessly, they can lead to false statements and ruin the credibility of your paper.

💡 Critical Thinking Topics & Questions

An excellent critical thinking essay starts with a question. But how do you formulate it properly? Keep reading to find out.

How to Write Critical Thinking Questions: Examples with Answers

Asking the right questions is at the core of critical thinking. They challenge our beliefs and encourage our interest to learn more.

Here are some examples of model questions that prompt critical thinking:

- What does… mean?

- What would happen if…?

- What are the principles of…?

- Why is… important?

- How does… affect…?

- What do you think causes…?

- How are… and… similar/different?

- How do you explain….?

- What are the implications of…?

- What do we already know about…?

Now, let’s look at some critical thinking questions with the answers. You can use these as a model for your own questions:

Question: What would happen if people with higher income paid more taxes?

- Answer: It would help society to prosper and function better. It would also help people out of poverty. This way, everyone can contribute to the economy.

Question: How does eating healthy benefit you?

- Answer: Healthy eating affects people’s lives in many positive ways. It reduces cancer risk, improves your mood and memory, helps with weight loss and diabetes management, and improves your night sleep.

Critical Thinking Essay Topics

Have you already decided what your essay will be about? If not, feel free to use these essay topic examples as titles for your paper or as inspiration. Make sure to choose a theme that interests you personally:

- What are the reasons for racism in healthcare?

- Why is accepting your appearance important?

- Concepts of critical thinking and logical reasoning .

- Nature and spirit in Ralf Waldo Emerson’s poetry.

- How does technological development affect communication in the modern world?

- Social media effect on adolescents.

- Is the representation of children in popular fiction accurate?

- Domestic violence and its consequences.

- Why is mutual aid important in society?

- How do stereotypes affect the way people think?

- The concept of happiness in different cultures.

- The purpose of environmental art.

- Why do people have the need to be praised?

- How did antibiotics change medicine and its development?

- Is there a way to combat inequality in sports?

- Is gun control an effective way of crime prevention?

- How our understanding of love changes through time.

- The use of social media by the older generation.

- Graffiti as a form of modern art.

- Negative health effects of high sugar consumption.

- Why are reality TV shows so popular?

- Why should we eat healthily?

- How effective and fair is the US judicial system?

- Reasons of Cirque du Soleil phenomenon.

- How can police brutality be stopped?

- Freedom of speech: does it exist?

- The effects of vaccination misconceptions.

- How to eliminate New Brunswick’s demographic deficit: action plan.

- What makes a good movie?

- Critical analysis of your favorite book.

- The connection between fashion and identity.

- Taboo topics and how they are discussed in gothic literature.

- Critical thinking essay on the problem of overpopulation.

- Does our lifestyle affect our mental health?

- The role of self-esteem in preventing eating disorders in children.

- Drug abuse among teenagers.

- Rhetoric on assisted suicide.

- Effects of violent video games on children’s mental health.

- Analyze the effect stress has on the productivity of a team member.

- Discuss the importance of the environmental studies.

- Critical thinking and ethics of happy life.

- The effects of human dignity on the promotion of justice.

- Examine the ethics of advertising the tobacco industry.

- Reasons and possible solutions of research misconduct.

- Implication of parental deployment for children.

- Cultural impact of superheroes on the US culture.

- Examine the positive and negative impact of technology on modern society.

- Critical thinking in literature: examples.

- Analyze the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on economic transformation.

- Benefits and drawbacks of mandatory vaccination.

Haven’t found a suitable essay idea? Try using our topic generator !

✅ How to Write a Critical Thinking Essay Step by Step

Now, let’s focus on planning and writing your critical thinking essay. In this section, you will find an essay outline, examples of thesis statements, and a brief overview of each essay part.

Critical Thinking Essay Outline

In a critical thinking essay, there are two main things to consider: a premise and a conclusion :

- A premise is a statement in the argument that explains the reason or supports a conclusion.

- A conclusion indicates what the argument is trying to prove. Each argument can have only one conclusion.

When it comes to structuring, a critical thinking essay is very similar to any other type of essay. Before you start writing it, make sure you know what to include in it. An outline is very helpful when it comes to structuring a paper.

How to Start a Critical Essay Introduction

An introduction gives readers a general idea of an essay’s contents. When you work on the introduction, imagine that you are drawing a map for the reader. It not only marks the final destination but also explains the route.

An introduction usually has 4 functions:

- It catches the reader’s attention;

- It states the essay’s main argument;

- It provides some general information about the topic;

- It shows the importance of the issue in question.

Here are some strategies that can make the introduction writing easier:

- Give an overview of the essay’s topic.

- Express the main idea.

- Define the main terms.

- Outline the issues that you are going to explore or argue about.

- Explain the methodology and why you used it.

- Write a hook to attract the reader’s attention.

Critical Analysis Thesis Statement & Examples

A thesis statement is an integral part of every essay. It keeps the paper organized and guides both the reader and the writer. A good thesis:

- expresses the conclusion or position on a topic;

- justifies your position or opinion with reasoning;

- conveys one idea;

- serves as the essay’s map.

To have a clearer understanding of what a good thesis is, let’s have a look at these examples.

| Bad thesis statement example | Good thesis statement example |

|---|---|

| Exercising is good for your health. | All office workers should add exercising to their daily routine because it helps to maintain a healthy lifestyle and reduce stress levels. |

The statement on the left is too general and doesn’t provide any reasoning. The one on the right narrows down the group of people to office workers and specifies the benefits of exercising.

Critical Thinking Essay Body Paragraphs: How to Write

Body paragraphs are the part of the essay where you discuss all the ideas and arguments. In a critical thinking essay, arguments are especially important. When you develop them, make sure that they:

- reflect the key theme;

- are supported by the sources/citations/examples.

Using counter-arguments is also effective. It shows that you acknowledge different points of view and are not easily persuaded.

In addition to your arguments, it’s essential to present the evidence . Demonstrate your critical thinking skills by analyzing each source and stating whether the author’s position is valid.

To make your essay logically flow, you may use transitions such as:

- Accordingly,

- For instance,

- On the contrary,

- In conclusion,

- Not only… but also,

- Undoubtedly.

How to Write a Critical Thinking Conclusion

In a critical thinking essay, the notion of “conclusion” is tightly connected to the one used in logic. A logical conclusion is a statement that specifies the author’s point of view or what the essay argues about. Each argument can have only one logical conclusion.

Sometimes they can be confused with premises. Remember that premises serve as a support for the conclusion. Unlike the conclusion, there can be several premises in a single argument. You can learn more about these concepts from the article on a logical consequence by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Keeping this in mind, have a look at these tips for finishing your essay:

- Briefly sum up the main points.

- Provide a final thought on the issue.

- Suggest some results or consequences.

- Finish up with a call for action.

📑 Critical Thinking Essays Examples & Formatting Tips

Formatting is another crucial aspect of every formal paper. MLA and APA are two popular formats when it comes to academic writing. They share some similarities but overall are still two different styles. Here are critical essay format guidelines that you can use as a reference:

| APA format | MLA format | |

|---|---|---|

| at the top of the page; | ||

| in the center of a new page in bold; |

Finally, you’re welcome to check out a full critical essay sample in MLA format. Download the PDF file below:

Currently, the importance of critical thinking has grown rapidly because technological progress has led to expanded access to various content-making platforms: websites, online news agencies, and podcasts with, often, low-quality information. Fake news is used to achieve political and financial aims, targeting people with low news literacy. However, individuals can stop spreading fallacies by detecting false agendas with the help of a skeptical attitude.

✍️ Bonus Tips: Critical Thinking and Writing Exercises

Critical thinking is a process different from our regular thinking. When we think in everyday life, we do it automatically. However, when we’re thinking critically, we do it deliberately.

So how do we get better at this type of thinking and make it a habit? These useful tips will help you do it:

- Ask basic questions. Sometimes, while we are doing research, the explanation becomes too complicated. To avoid it, always go back to your topic.

- Question basic assumptions. When thinking through a problem, ask yourself whether your beliefs can be wrong. Keep an open mind while researching your question.

- Think for yourself. Avoid getting carried away in the research and buying into other people’s opinions.

- Reverse things. Sometimes it seems obvious that one thing causes another, but what if it’s the other way around?

- Evaluate existing evidence. If you work with sources, it’s crucial to evaluate and question them.

Another way to improve your reasoning skills is to do critical thinking exercises. Here are some of them:

| Exercise | Technique | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Brainstorming | Free-writing | Choose a topic and write on it for 7-10 minutes straight. Don’t concern yourself with grammar. |

| Clustering | Choose a keyword and write down the words that you associate with it. Keep doing that for 5-10 minutes. | |

| Listing | List down all the ideas that are concerning the subject you are about to explore. | |

| Metaphor writing | Write a metaphor or simile and explain why it works or what it means to you. | |

| Journalistic questions | Write questions such as “Who?” “When?” “Why?” “How?” Answer these questions in relation to your topic. | |

| Organizing | Drawing diagrams | Jot down your main ideas and see if you can make a chart or form a shape depicting their relationship. |

| Rewriting an idea | Try briefly outlining the central idea over the course of several days and see how your thoughts change. | |

| Solution writing | Look at your idea through a problem-solving lens. Briefly describe the problem and then make a list of solutions. | |

| Drafting | Full draft writing | Write a draft of a whole paper to see how you express ideas on paper. |

| Outlining | Outline your essay to structure the ideas you have. | |

| Writing with a timer | Set a timer and write a draft within a set amount of time. | |

| Revising | Analyzing sentences | Analyze your draft at the sentence level and see if your paper makes sense. |

| Underlying the main point | Highlight the main point of your paper. Make sure it’s expressed clearly. | |

| Outlining the draft | Summarize every paragraph of your essay in one sentence. |

Thanks for reading through our article! We hope that you found it helpful and learned some new information. If you liked it, feel free to share it with your friends.

Further reading:

- Critical Writing: Examples & Brilliant Tips [2024]

- How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay: Outline, Steps, & Examples

- How to Write an Analysis Essay: Examples + Writing Guide

- How to Write a Critique Paper: Tips + Critique Essay Examples

- How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Step by Step

- Critical Thinking and Writing: University of Kent

- Steps to Critical Thinking: Rasmussen University

- 3 Simple Habits to Improve Your Critical Thinking: Harvard Business Review

- In-Class Writing Exercises: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Demonstrating Critical Thinking in Writing: University of South Australia

- 15 Questions that Teachers and Parents Can Ask Kids to Encourage Critical Thinking: The Hun School

- Questions to Provoke Critical Thinking: Brown University

- How to Write a College Critical Thinking Essay: Seattle PI

- Introductions: What They Do: Royal Literary Fund

- Thesis Statements: Arizona State University

- Share to Facebook

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Process analysis is an explanation of how something works or happens. Want to know more? Read the following article prepared by our custom writing specialists and learn about: So, let’s start digging deeper into this topic! ♻️ What Is Process Analysis? A process analysis describes and explains the succession of...

A visual analysis essay is an academic paper type that history and art students often deal with. It consists of a detailed description of an image or object. It can also include an interpretation or an argument that is supported by visual evidence. In this article, our custom writing experts...

Want to know how to write a reflection paper for college or school? To do that, you need to connect your personal experiences with theoretical knowledge. Usually, students are asked to reflect on a documentary, a text, or their experience. Sometimes one needs to write a paper about a lesson...

A character analysis is an examination of the personalities and actions of protagonists and antagonists that make up a story. It discusses their role in the story, evaluates their traits, and looks at their conflicts and experiences. You might need to write this assignment in school or college. Like any...

Any literary analysis is a challenging task since literature includes many elements that can be interpreted differently. However, a stylistic analysis of all the figurative language the poets use may seem even harder. You may never realize what the author actually meant and how to comment on it! While analyzing...

As a student, you may be asked to write a book review. Unlike an argumentative essay, a book review is an opportunity to convey the central theme of a story while offering a new perspective on the author’s ideas. Knowing how to create a well-organized and coherent review, however, is...

The difference between an argumentative and persuasive essay isn’t always clear. If you’re struggling with either style for your next assignment, don’t worry. The following will clarify everything you need to know so you can write with confidence. First, we define the primary objectives of argumentative vs. persuasive writing. We...

You don’t need to be a nerd to understand the general idea behind cause and effect essays. Let’s see! If you skip a meal, you get hungry. And if you write an essay about it, your goal is achieved! However, following multiple rules of academic writing can be a tough...

![how to demonstrate critical thinking in an essay How to Write an Argumentative Essay: 101 Guide [+ Examples]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/young-writer-taking-notes-284x153.jpg)

An argumentative essay is a genre of academic writing that investigates different sides of a particular issue. Its central purpose is to inform the readers rather than expressively persuade them. Thus, it is crucial to differentiate between argumentative and persuasive essays. While composing an argumentative essay, the students have to...

![how to demonstrate critical thinking in an essay How to Title an Essay: Guide with Creative Examples [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/close-up-woman-making-greeting-card-new-year-christmas-2021-friends-family-scrap-booking-diy-writing-letter-with-best-wishes-design-her-homemade-card-holidays-celebration-284x153.jpg)

It’s not a secret that the reader notices an essay title first. No catchy hook or colorful examples attract more attention from a quick glance. Composing a creative title for your essay is essential if you strive to succeed, as it: Thus, how you name your paper is of the...

The conclusion is the last paragraph in your paper that draws the ideas and reasoning together. However, its purpose does not end there. A definite essay conclusion accomplishes several goals: Therefore, a conclusion usually consists of: Our experts prepared this guide, where you will find great tips on how to...

![how to demonstrate critical thinking in an essay How to Write a Good Introduction: Examples & Tips [2024 Upd.]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/closeup-shot-woman-working-studying-from-home-with-red-coffee-cup-nearby-284x153.jpg)

A five-paragraph essay is one of the most common academic assignments a student may face. It has a well-defined structure: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Writing an introduction can be the most challenging part of the entire piece. It aims to introduce the main ideas and present...

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic

Gita DasBender

There is something about the term “critical thinking” that makes you draw a blank every time you think about what it means. [1] It seems so fuzzy and abstract that you end up feeling uncomfortable, as though the term is thrust upon you, demanding an intellectual effort that you may not yet have. But you know it requires you to enter a realm of smart, complex ideas that others have written about and that you have to navigate, understand, and interact with just as intelligently. It’s a lot to ask for. It makes you feel like a stranger in a strange land.

As a writing teacher I am accustomed to reading and responding to difficult texts. In fact, I like grappling with texts that have interesting ideas no matter how complicated they are because I understand their value. I have learned through my years of education that what ultimately engages me, keeps me enthralled, is not just grammatically pristine, fluent writing, but writing that forces me to think beyond the page. It is writing where the writer has challenged herself and then offered up that challenge to the reader, like a baton in a relay race. The idea is to run with the baton.

You will often come across critical thinking and analysis as requirements for assignments in writing and upper-level courses in a variety of disciplines. Instructors have varying explanations of what they actually require of you, but, in general, they expect you to respond thoughtfully to texts you have read. The first thing you should remember is not to be afraid of critical thinking. It does not mean that you have to criticize the text, disagree with its premise, or attack the writer simply because you feel you must. Criticism is the process of responding to and evaluating ideas, argument, and style so that readers understand how and why you value these items.

Critical thinking is also a process that is fundamental to all disciplines. While in this essay I refer mainly to critical thinking in composition, the general principles behind critical thinking are strikingly similar in other fields and disciplines. In history, for instance, it could mean examining and analyzing primary sources in order to understand the context in which they were written. In the hard sciences, it usually involves careful reasoning, making judgments and decisions, and problem solving. While critical thinking may be subject-specific, that is to say, it can vary in method and technique depending on the discipline, most of its general principles such as rational thinking, making independent evaluations and judgments, and a healthy skepticism of what is being read, are common to all disciplines. No matter the area of study, the application of critical thinking skills leads to clear and flexible thinking and a better understanding of the subject at hand.

To be a critical thinker you not only have to have an informed opinion about the text but also a thoughtful response to it. There is no doubt that critical thinking is serious thinking, so here are some steps you can take to become a serious thinker and writer.

Attentive Reading: A Foundation for Critical Thinking

A critical thinker is always a good reader because to engage critically with a text you have to read attentively and with an open mind, absorbing new ideas and forming your own as you go along. Let us imagine you are reading an essay by Annie Dillard, a famous essayist, called “Living like Weasels.” Students are drawn to it because the idea of the essay appeals to something personally fundamental to all of us: how to live our lives. It is also a provocative essay that pulls the reader into the argument and forces a reaction, a good criterion for critical thinking.

So let’s say that in reading the essay you encounter a quote that gives you pause. In describing her encounter with a weasel in Hollins Pond, Dillard says, “I would like to learn, or remember, how to live . . . I don’t think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular . . . but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical senses and the dignity of living without bias or motive” (220). You may not be familiar with language like this. It seems complicated, and you have to stop ever so often (perhaps after every phrase) to see if you understood what Dillard means. You may ask yourself these questions:

- What does “mindlessness” mean in this context?

- How can one “learn something of mindlessness?”

- What does Dillard mean by “purity of living in the physical senses?”

- How can one live “without bias or motive?”

These questions show that you are an attentive reader. Instead of simply glossing over this important passage, you have actually stopped to think about what the writer means and what she expects you to get from it. Here is how I read the quote and try to answer the questions above: Dillard proposes a simple and uncomplicated way of life as she looks to the animal world for inspiration. It is ironic that she admires the quality of “mindlessness” since it is our consciousness, our very capacity to think and reason, which makes us human, which makes us beings of a higher order. Yet, Dillard seems to imply that we need to live instinctually, to be guided by our senses rather than our intellect. Such a “thoughtless” approach to daily living, according to Dillard, would mean that our actions would not be tainted by our biases or motives, our prejudices. We would go back to a primal way of living, like the weasel she observes. It may take you some time to arrive at this understanding on your own, but it is important to stop, reflect, and ask questions of the text whenever you feel stumped by it. Often such questions will be helpful during class discussions and peer review sessions.

Listing Important Ideas

When reading any essay, keep track of all the important points the writer makes by jotting down a list of ideas or quotations in a notebook. This list not only allows you to remember ideas that are central to the writer’s argument, ideas that struck you in some way or the other, but it also you helps you to get a good sense of the whole reading assignment point by point. In reading Annie Dillard’s essay, we come across several points that contribute toward her proposal for better living and that help us get a better understanding of her main argument. Here is a list of some of her ideas that struck me as important:

- “The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons” (220).

- “And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel’s: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will” (221).

- “We can live any way we want. People take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—even of silence—by choice. The thing is to stalk your calling in a certain skilled and supple way, to locate the most tender and live spot and plug into that pulse” (221).

- “A weasel doesn’t ‘attack’ anything; a weasel lives as he’s meant to, yielding at every moment to the perfect freedom of single necessity” (221).

- “I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you” (221).

These quotations give you a cumulative sense of what Dillard is trying to get at in her essay, that is, they lay out the elements with which she builds her argument. She first explains how the weasel lives, what she learns from observing the weasel, and then prescribes a lifestyle she admires—the central concern of her essay.

Noticing Key Terms and Summarizing Important Quotes

Within the list of quotations above are key terms and phrases that are critical to your understanding of the ideal life as Dillard describes it. For instance, “mindlessness,” “instinct,” “perfect freedom of a single necessity,” “stalk your calling,” “choice,” and “fierce and pointed will” are weighty terms and phrases, heavy with meaning, that you need to spend time understanding. You also need to understand the relationship between them and the quotations in which they appear. This is how you might work on each quotation to get a sense of its meaning and then come up with a statement that takes the key terms into account and expresses a general understanding of the text:

Quote 1 : Animals (like the weasel) live in “necessity,” which means that their only goal in life is to survive. They don’t think about how they should live or what choices they should make like humans do. According to Dillard, we like to have options and resist the idea of “necessity.” We fight death—an inevitable force that we have no control over—and yet ultimately surrender to it as it is the necessary end of our lives. Quote 2 : Dillard thinks the weasel’s way of life is the best way to live. It implies a pure and simple approach to life where we do not worry about the passage of time or the approach of death. Like the weasel, we should live life in the moment, intensely experiencing everything but not dwelling on the past. We should accept our condition, what we are “given,” with a “fierce and pointed will.” Perhaps this means that we should pursue our one goal, our one passion in life, with the same single-minded determination and tenacity that we see in the weasel. Quote 3 : As humans, we can choose any lifestyle we want. The trick, however, is to go after our one goal, one passion like a stalker would after a prey. Quote 4 : While we may think that the weasel (or any animal) chooses to attack other animals, it is really only surrendering to the one thing it knows: its need to live. Dillard tells us there is “the perfect freedom” in this desire to survive because to her, the lack of options (the animal has no other option than to fight to survive) is the most liberating of all. Quote 5 : Dillard urges us to latch on to our deepest passion in life (the “one necessity”) with the tenacity of a weasel and not let go. Perhaps she’s telling us how important it is to have an unwavering focus or goal in life.

Writing a Personal Response: Looking Inward

Dillard’s ideas will have certainly provoked a response in your mind, so if you have some clear thoughts about how you feel about the essay this is the time to write them down. As you look at the quotes you have selected and your explanation of their meaning, begin to create your personal response to the essay. You may begin by using some of these strategies:

- Tell a story. Has Dillard’s essay reminded you of an experience you have had? Write a story in which you illustrate a point that Dillard makes or hint at an idea that is connected to her essay.

- Focus on an idea from Dillard’s essay that is personally important to you. Write down your thoughts about this idea in a first person narrative and explain your perspective on the issue.

- If you are uncomfortable writing a personal narrative or using “I” (you should not be), reflect on some of her ideas that seem important and meaningful in general. Why were you struck by these ideas?

- Write a short letter to Dillard in which you speak to her about the essay. You may compliment her on some of her ideas by explaining why you like them, ask her a question related to her essay and explain why that question came to you, and genuinely start up a conversation with her.

This stage in critical thinking is important for establishing your relationship with a text. What do I mean by this “relationship,” you may ask? Simply put, it has to do with how you feel about the text. Are you amazed by how true the ideas seem to be, how wise Dillard sounds? Or are you annoyed by Dillard’s let-me-tell-you-how-to-live approach and disturbed by the impractical ideas she so easily prescribes? Do you find Dillard’s voice and style thrilling and engaging or merely confusing? No matter which of the personal response options you select, your initial reaction to the text will help shape your views about it.

Making an Academic Connection: Looking Outward

First year writing courses are designed to teach a range of writing— from the personal to the academic—so that you can learn to express advanced ideas, arguments, concepts, or theories in any discipline. While the example I have been discussing pertains mainly to college writing, the method of analysis and approach to critical thinking I have demonstrated here will serve you well in a variety of disciplines. Since critical thinking and analysis are key elements of the reading and writing you will do in college, it is important to understand how they form a part of academic writing. No matter how intimidating the term “academic writing” may seem (it is, after all, associated with advanced writing and becoming an expert in a field of study), embrace it not as a temporary college requirement but as a habit of mind.

To some, academic writing often implies impersonal writing, writing that is detached, distant, and lacking in personal meaning or relevance. However, this is often not true of the academic writing you will do in a composition class. Here your presence as a writer—your thoughts, experiences, ideas, and therefore who you are—is of much significance to the writing you produce. In fact, it would not be farfetched to say that in a writing class academic writing often begins with personal writing. Let me explain. If critical thinking begins with a personal view of the text, academic writing helps you broaden that view by going beyond the personal to a more universal point of view. In other words, academic writing often has its roots in one’s private opinion or perspective about another writer’s ideas but ultimately goes beyond this opinion to the expression of larger, more abstract ideas. Your personal vision—your core beliefs and general approach to life— will help you arrive at these “larger ideas” or universal propositions that any reader can understand and be enlightened by, if not agree with. In short, academic writing is largely about taking a critical, analytical stance toward a subject in order to arrive at some compelling conclusions.

Let us now think about how you might apply your critical thinking skills to move from a personal reaction to a more formal academic response to Annie Dillard’s essay. The second stage of critical thinking involves textual analysis and requires you to do the following:

- Summarize the writer’s ideas the best you can in a brief paragraph. This provides the basis for extended analysis since it contains the central ideas of the piece, the building blocks, so to speak.

- Evaluate the most important ideas of the essay by considering their merits or flaws, their worthiness or lack of worthiness. Do not merely agree or disagree with the ideas but explore and explain why you believe they are socially, politically, philosophically, or historically important and relevant, or why you need to question, challenge, or reject them.

- Identify gaps or discrepancies in the writer’s argument. Does she contradict herself? If so, explain how this contradiction forces you to think more deeply about her ideas. Or if you are confused, explain what is confusing and why.

- Examine the strategies the writer uses to express her ideas. Look particularly at her style, voice, use of figurative language, and the way she structures her essay and organizes her ideas. Do these strategies strengthen or weaken her argument? How?

- Include a second text—an essay, a poem, lyrics of a song— whose ideas enhance your reading and analysis of the primary text. This text may help provide evidence by supporting a point you’re making, and further your argument.

- Extend the writer’s ideas, develop your own perspective, and propose new ways of thinking about the subject at hand.

Crafting the Essay

Once you have taken notes and developed a thorough understanding of the text, you are on your way to writing a good essay. If you were asked to write an exploratory essay, a personal response to Dillard’s essay would probably suffice. However, an academic writing assignment requires you to be more critical. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, beginning your essay with a personal anecdote often helps to establish your relationship to the text and draw the reader into your writing. It also helps to ease you into the more complex task of textual analysis. Once you begin to analyze Dillard’s ideas, go back to the list of important ideas and quotations you created as you read the essay. After a brief summary, engage with the quotations that are most important, that get to the heart of Dillard’s ideas, and explore their meaning. Textual engagement, a seemingly slippery concept, simply means that you respond directly to some of Dillard’s ideas, examine the value of Dillard’s assertions, and explain why they are worthwhile or why they should be rejected. This should help you to transition into analysis and evaluation. Also, this part of your essay will most clearly reflect your critical thinking abilities as you are expected not only to represent Dillard’s ideas but also to weigh their significance. Your observations about the various points she makes, analysis of conflicting viewpoints or contradictions, and your understanding of her general thesis should now be synthesized into a rich new idea about how we should live our lives. Conclude by explaining this fresh point of view in clear, compelling language and by rearticulating your main argument.

Modeling Good Writing

When I teach a writing class, I often show students samples of really good writing that I’ve collected over the years. I do this for two reasons: first, to show students how another freshman writer understood and responded to an assignment that they are currently working on; and second, to encourage them to succeed as well. I explain that although they may be intimidated by strong, sophisticated writing and feel pressured to perform similarly, it is always helpful to see what it takes to get an A. It also helps to follow a writer’s imagination, to learn how the mind works when confronted with a task involving critical thinking. The following sample is a response to the Annie Dillard essay. Figure 1 includes the entire student essay and my comments are inserted into the text to guide your reading.

Though this student has not included a personal narrative in his essay, his own world-vievvw is clear throughout. His personal point of view, while not expressed in first person statements, is evident from the very beginning. So we could say that a personal response to the text need not always be expressed in experiential or narrative form but may be present as reflection, as it is here. The point is that the writer has traveled through the rough terrain of critical thinking by starting out with his own ruminations on the subject, then by critically analyzing and responding to Dillard’s text, and finally by developing a strongpoint of view of his own about our responsibility as human beings. As readers we are engaged by clear, compelling writing and riveted by critical thinking that produces a movement of ideas that give the essay depth and meaning. The challenge Dillard set forth in her essay has been met and the baton passed along to us.

Building our Lives: The Blueprint Lies Within

We all may ask ourselves many questions, some serious, some less important, in our lifetime. But at some point along the way, we all will take a step back and look at the way we are living our lives, and wonder if we are living them correctly. Unfortunately, there is no solid blueprint for the way to live our lives. Each person is different, feeling different emotions and reacting to different stimuli than the person next to them. Many people search for the true answer on how to live our lives, as if there are secret instructions out there waiting to be found. But the truth is we as a species are given a gift not many other creatures can claim to have: the ability to choose to live as we want, not as we were necessarily designed to. [2] Even so, people look outside of themselves for the answers on how to live, which begs me to ask the question: what is wrong with just living as we are now, built from scratch through our choices and memories? [3]

[Annie Dillard’s essay entitled “Living Like Weasels” is an exploration into the way human beings might live, clearly stating that “We could live any way we want” (Dillard 211). Dillard’s encounter with an ordinary weasel helped her receive insight into the difference between the way human beings live their lives and the way wild animals go about theirs. As a nature writer, Dillard shows us that we can learn a lot about the true way to live by observing nature’s other creations. While we think and debate and calculate each and every move, these creatures just simply act. [4] The thing that keeps human beings from living the purest life possible, like an animal such as the weasel, is the same thing that separates us from all wild animals: our minds. Human beings are creatures of caution, creatures of undeniable fear, never fully living our lives because we are too caught up with avoiding risks. A weasel, on the other hand, is a creature of action and instinct, a creature which lives its life the way it was created to, not questioning his motives, simply striking when the time to strike is right. As Dillard states, “the weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons” (Dillard 210). [5]

It is important to note and appreciate the uniqueness of the ideas Dillard presents in this essay because in some ways they are very true. For instance, it is true that humans live lives of caution, with a certain fear that has been built up continually through the years. We are forced to agree with Dillard’s idea that we as humans “might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical senses and the dignity of living without bias or motive” (Dillard 210). To live freely we need to live our lives with less hesitation, instead of intentionally choosing to not live to the fullest in fear of the consequences of our actions. [6] However, Dillard suggests that we should forsake our ability of thought and choice all together. The human mind is the tool that has allowed a creature with no natural weapons to become the unquestioned dominant species on this plant planet, and though it curbs the spontaneity of our lives, it is not something to be simply thrown away for a chance to live completely “free of bias or motive” (Dillard 210). [7] We are a moral, conscious species, complete with emotions and a firm conscience, and it is the power of our minds that allows us to exist as we do now: with the ability to both think and feel at the same time. It grants us the ability to choose and have choice, to be guided not only by feelings and emotions but also by morals and an understanding of consequence. [8] As such, a human being with the ability to live like a weasel has given up the very thing that makes him human. [9]

Here, the first true flaw of Dillard’s essay comes to light. While it is possible to understand and even respect Dillard’s observations, it should be noted that without thought and choice she would have never been able to construct these notions in the first place. [10] Dillard protests, “I tell you I’ve been in that weasel’s brain for sixty seconds, and he was in mine” (Dillard 210). One cannot cast oneself into the mind of another creature without the intricacy of human thought, and one would not be able to choose to live as said creature does without the power of human choice. In essence, Dillard would not have had the ability to judge the life of another creature if she were to live like a weasel. Weasels do not make judgments; they simply act and react on the basis of instinct. The “mindlessness” that Dillard speaks of would prevent her from having the option to choose her own reactions. Whereas the conscious-‐ thinking Dillard has the ability to see this creature and take the time to stop and examine its life, the “mindless” Dillard would only have the limited options to attack or run away. This is the major fault in the logic of Dillard’s essay, as it would be impossible for her to choose to examine and compare the lives of humans and weasels without the capacity for choice. [11]

Dillard also examines a weasel’s short memory in a positive light and seems to believe that a happier life could be achieved if only we were simple-minded enough to live our lives with absolutely no regret. She claims, “I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel’s: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will” (Dillard 210). In theory, this does sound like a positive value. To be able to live freely without a hint of remembrance as to the results of our choices would be an interesting life, one may even say a care-free life. But at the same time, would we not be denying our responsibility as humans to learn from the mistakes of the past as to not replicate them in the future? [12] Human beings’ ability to remember is almost as important as our ability to choose, because [13] remembering things from the past is the only way we can truly learn from them. History is taught throughout our educational system for a very good reason: so that the generations of the future do not make the mistakes of the past. A human being who chooses to live like a weasel gives up something that once made him very human: the ability to learn from his mistakes to further better himself.

Ultimately, without the ability to choose or recall the past, mankind would be able to more readily take risks without regard for consequences. [14] Dillard views the weasel’s reaction to necessity as an unwavering willingness to take such carefree risks and chances. She states that “it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you” (Dillard 211). Would it then be productive for us to make a wrong choice and be forced to live in it forever, when we as a people have the power to change, to remedy wrongs we’ve made in our lives? [15] What Dillard appears to be recommending is that humans not take many risks, but who is to say that the ability to avoid or escape risks is necessarily a flaw with mankind?

If we had been like the weasel, never wanting, never needing, always “choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will” (Dillard 210), our world would be a completely different place. The United States of America might not exist at this very moment if we had just taken what was given to us, and unwaveringly accepted a life as a colony of Great Britain. But as Cole clearly puts it, “A risk that you assume by actually doing something seems far more risky than a risk you take by not doing something, even though the risk of doing nothing may be greater” (Cole 145). As a unified body of people, we were able to go against that which was expected of us, evaluate the risk in doing so, and move forward with our revolution. The American people used the power of choice, and risk assessment, to make a permanent change in their lives; they used the remembrance of Britain’s unjust deeds to fuel their passion for victory. [16] We as a people chose. We remembered. We distinguished between right and wrong. These are things that a weasel can never do, because a weasel does not have a say in its own life, it only has its instincts and nothing more.

Humans are so unique in the fact that they can dictate the course of their own lives, but many people still choose to search around for the true way to live. What they do not realize is that they have to look no further than themselves. Our power, our weapon, is our ability to have thought and choice, to remember, and to make our own decisions based on our concepts of right and wrong, good and bad. These are the only tools we will ever need to construct the perfect life for ourselves from the ground up. And though it may seem like a nice notion to live a life free of regret, it is our responsibility as creatures and the appointed caretakers of this planet to utilize what was given to us and live our lives as we were meant to, not the life of any other wild animal. [17]

- Write about your experiences with critical thinking assignments. What seemed to be the most difficult? What approaches did you try to overcome the difficulty?

- Respond to the list of strategies on how to conduct textual analysis. How well do these strategies work for you? Add your own tips to the list.

- Evaluate the student essay by noting aspects of critical thinking that are evident to you. How would you grade this essay? What other qualities (or problems) do you notice?

Works Cited

Dillard, Annie. “Living like Weasels.” One Hundred Great Essays . Ed. Robert DiYanni. New York: Longman, 2002. 217–221. Print.

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNoncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States License and is subject to the Writing Spaces’ Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. To view the Writing Spaces’ Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use . ↵

- Comment : Even as the writer starts with a general introduction, he makes a claim here that is related to Dillard’s essay. ↵

- Comment : The student asks what seems like a rhetorical question but it is one he will answer in the rest of his essay. It is also a question that forces the reader to think about a key term from the text— “choices.” ↵

- Comment : Student summarizes Dillard’s essay by explaining the ideas of the essay in fresh words. ↵

- Comment : Up until this point the student has introduced Dillard’s essay and summarized some of its ideas. In the section that follows, he continues to think critically about Dillard’s ideas and argument. ↵

- Comment : This is a strong statement that captures the student’s appreciation of Dillard’s suggestion to live freely but also the ability to recognize why most people cannot live this way. This is a good example of critical thinking. ↵

- Comment : Again, the student acknowledges the importance of conscious thought. ↵

- Comment : While the student does not include a personal experience in the essay, this section gives us a sense of his personal view of life. Also note how he introduces the term “morals” here to point out the significance of the consequences of our actions. The point is that not only do we need to act but we also need to be aware of the result of our actions. ↵

- Comment : Student rejects Dillard’s ideas but only after explaining why it is important to reject them. ↵

- Comment : Student dismantles Dillard’s entire premise by telling us how the very act of writing the essay negates her argument. He has not only interpreted the essay but figured out how its premise is logically flawed. ↵

- Comment : Once again the student demonstrates why the logic of Dillard’s argument falls short when applied to her own writing. ↵

- Comment : This question represents excellent critical thinking. The student acknowledges that theoretically “remembering nothing’ may have some merits but then ponders on the larger socio-‐political problem it presents. ↵

- Comment : The student brings two ideas together very smoothly here. ↵

- Comment : The writer sums up his argument while once again reminding us of the problem with Dillard’s ideas. ↵

- Comment : This is another thoughtful question that makes the reader think along with the writer. ↵

- Comment : The student makes a historical reference here that serves as strong evidence for his own argument. ↵

- Comment : This final paragraph sums up the writer’s perspective in a thoughtful and mature way. It moves away from Dillard’s argument and establishes the notion of human responsibility, an idea highly worth thinking about. ↵

Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic Copyright © 2011 by Gita DasBender is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing to Think: Critical Thinking and the Writing Process

“Writing is thinking on paper.” (Zinsser, 1976, p. vii)

Google the term “critical thinking.” How many hits are there? On the day this tutorial was completed, Google found about 65,100,000 results in 0.56 seconds. That’s an impressive number, and it grows more impressively large every day. That’s because the nation’s educators, business leaders, and political representatives worry about the level of critical thinking skills among today’s students and workers.

What is Critical Thinking?

Simply put, critical thinking is sound thinking. Critical thinkers work to delve beneath the surface of sweeping generalizations, biases, clichés, and other quick observations that characterize ineffective thinking. They are willing to consider points of view different from their own, seek and study evidence and examples, root out sloppy and illogical argument, discern fact from opinion, embrace reason over emotion or preference, and change their minds when confronted with compelling reasons to do so. In sum, critical thinkers are flexible thinkers equipped to become active and effective spouses, parents, friends, consumers, employees, citizens, and leaders. Every area of life, in other words, can be positively affected by strong critical thinking.

Released in January 2011, an important study of college students over four years concluded that by graduation “large numbers [of American undergraduates] didn’t learn the critical thinking, complex reasoning and written communication skills that are widely assumed to be at the core of a college education” (Rimer, 2011, para. 1). The University designs curriculum, creates support programs, and hires faculty to help ensure you won’t be one of the students “[showing]no significant gains in . . . ‘higher order’ thinking skills” (Rimer, 2011, para. 4). One way the University works to help you build those skills is through writing projects.

Writing and Critical Thinking