- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

gender binary

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

gender binary , system that classifies sex and gender into a pair of opposites, often imposed by culture , religion , or other societal pressures. Within the gender binary system, all of the human population fits into one of two genders: man or woman. Proponents of the system consider the gender binary to be a useful and accurate system of classification; however, critics often view it as a system that discriminates against individuals who identify as transgender or gender nonconforming (by definition, the model does not include gender identities that exist outside the binary system). Some critics also consider the gender binary system to be harmful toward cisgender individuals (those who identify with the sex and gender assigned to them at birth ), because of its perceived tendency to reinforce gender roles and stereotypes .

Increasingly, gender and sex are treated as separate concepts. In discussions about gender identity and the gender binary system, sex is often used to refer to genetic and biological characteristics , such as sexual anatomy and chromosomes . This contrasts with gender , which may be understood as referring to the social consequences of these biological characteristics, an amalgamation of cultural influence and pressure; thus, gender can be considered a social construct. Gender essentialists—those who believe that gender functions as a binary system—hold the position that one’s biological sex, or sex assigned at birth, determines gender and that the two concepts cannot be separated. In other words, a child born with the sexual anatomy and chromosomes of a female should be raised as a woman, and a child born with the sexual anatomy and chromosomes of a male should be raised as a man.

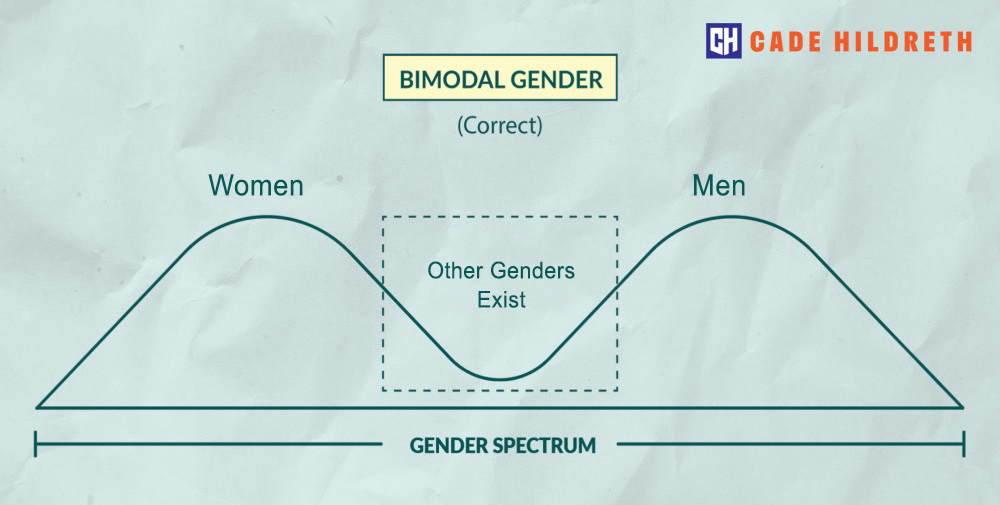

Many critics of the gender binary system argue that gender essentialism is rooted in cisnormativity, a term that refers to the assumption that everyone is cisgender, and so it discriminates against individuals who identify as transgender or gender nonconforming. An alternative to the gender binary system, which is known as the gender continuum , is a non-essentialist, multiaxial model (a framework that considers several categories of factors) that allows gender identity to be understood along scales of mental, biological, and behavioral traits. Many find this model to be more inclusive toward transgender individuals (those who identify with a gender other than that assigned at birth) and nonbinary individuals (those who identify themselves as being outside the gender binary system and who may not identify with a single gender at all).

In Western cultures , the gender binary system can be understood as constituting an invisible foundation upon which much of everyday life is built. Gendered public restrooms are a universal example of how the gender binary system manifests in the world, and thus they may present obstacles for individuals who identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming. Gendered public restrooms are also problematic because many transgender individuals have faced discrimination and violence when using the public restrooms that correspond to their gender identity. This gender separation also persists in prisons , military services , schools, and sports . The gender binary system permeates the commercial world, where retail items such as clothing, toys , and toiletries are often classified by gender, and even advertisement campaigns, television shows, and other media are gender-coded. Critics of the gender binary system often see these dichotomies as being harmful, as they are thought to push the performance of either male or female gender. For example, women and girls are expected to prefer “girly” items and media, whereas men and boys are expected to prefer what is marketed as masculine and tough. These expectations may perpetuate damaging stereotypes toward both men and women. The concept of toxic masculinity (social guidelines associated with stereotypes of manliness that incentivize looking and acting tough and powerful, which can lead to negative outcomes), for example, may be considered a consequence of the strict opposition between femininity and masculinity that the gender binary system enforces. In turn, women have historically been considered weaker and less capable than men due to their femininity, which has resulted in inequalities such as wage gaps and fewer employment opportunities.

That the gender binary system seems so fundamental to everyday life may lead some to believe that it is intrinsic to human nature . However, critics often refute the purported universal nature of the gender binary system by pointing to the many non-Western cultures and civilizations that have embraced multigender systems for millennia. Among non-Western cultures, the categories of “two-spirit” in some North American Indigenous cultures and hijra in India are, in simplified terms, examples of third gender identities that are accepted within their respective cultures.

Has Gender Always Been Binary?

Gender has historically been viewed in a more fluid manner..

Posted September 16, 2018 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

The extent to which men conform to stereotypical masculine behaviors and interests and the extent to which women conform to stereotypical feminine behaviors and interests can be described as gender conformity . When individuals stray from their expected gender roles—or behave in gender non-conforming ways—they tend to be evaluated negatively, although such negative views are not meted out equally. For example, men who possess feminine qualities or interests are often evaluated much more harshly than women who possess masculine interests or qualities. One does not need to look any further than the differing connotations applied to the concepts of a tomboy girl versus a sissy boy to see how society responds differently to gender nonconformity as a function of whether one is adopting or abandoning masculinity.

The very notion of gender non-conformity is predicated upon a concept known as the gender binary.

The gender binary refers to the notion that gender comes in two distinct flavors: men and women, in which men are masculine, women are feminine, and, importantly, men are of the male sex and women are of the female sex. Much of the world around us is based upon this binary understanding of sex and gender, such as the clothing we buy, barbershops vs. salons, and men’s rooms vs. women’s rooms. In fact, one of the first things new parents often learn about their future child is their sex, based on a grainy ultrasound image of tiny little genitals. From this point forward, a parent’s idea of who their child will grow up to be is significantly shaped by the sex, represented through the color of the nursery room, the types of clothing purchased, and of course, the list of potential baby names. Our expectations based on gender do not stop there. When we find out that a baby is a boy, we are more likely to describe him as strong, tough or handsome, whereas we will view baby girls as sweet, gentle and kind.

The gender binary is such a prevalent and well-accepted concept within our society that we tend to get upset when we are unable to place something or someone into one box or the other. We even extend this binary to our pets , often getting upset if people mistake our handsome boy dog for a girl, quickly correcting the offending stranger by emphasizing our response to “Ohhhh what a cute little puppy, what is her name?” with “ His name is Buddy!” This isn't to say that there is no such thing as a male dog or a female dog, but rather, it emphasizes our cultural investment in perceiving someone's (or some dog's) gender correctly and using that piece of information as an overarching tool through which to understand the person or dog that we have just encountered.

Yet, while the gender binary is certainly well anchored within society and our social mores, there is actually a long history of gender not being viewed in such a black and white manner. Indeed, many indigenous cultures around the globe held more fluid and dynamic understandings of gender before encountering Western theories of gender. Even within Western cultures, the characteristics associated with one gender or the other have changed stripes so many times through history that it is almost surprising how adamantly we now argue that heels , wigs, makeup , and the color pink are only for women and girls, when all of these things were previously reserved only for men and boys.

Thus, while it may seem like discussions about non-binary understandings of gender and acceptance of gender nonconforming behavior are new additions to the daily dialogue, there is perhaps more in our collective past to point us towards a more diverse understanding of gender than there is to keep us focused on rigidly defined, binary gender roles.

While these topics seem to come up most frequently when discussing transgender and non-binary individuals and their respective rights, as well as the controversies that surround their ability to access those rights, the concept of dismantling a binary view of gender is actually one that applies to everyone, whether you identify as cisgender (someone whose gender identity and expression is the same as the sex they were assigned at birth), transgender (someone whose gender identity and/or expression is different from the sex they were assigned at birth), non-binary (someone who does not define their gender based on the binaries of men and women) or agender (someone who identifies as not having a gender). Adopting a more open and fluid understanding of gender certainly makes it easier to accept transgender, non-binary and agender individuals, but it also makes it easier to be accepting of anyone who possesses, expresses, or desires qualities that have previously been earmarked as being the prevue of only one gender or the other.

In my next few posts, I will be exploring some recent research related to the gender binary, including a study that examined whether an individual’s gender non-conforming behavior is seen as more or less threatening when the individual is transgender vs. cisgender and a recent symposium that explored the experiences of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals around the globe.

Hoskin, R. A. (2017). Femme theory: Refocusing the intersectional lens . Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice, 38 (1), 95-109.

Vasey, P. L., & Bartlett, N. H. (2007). What can the Samoan" fa'afafine " teach us about the Western concept of gender identity disorder in childhood? . Perspectives in biology and medicine, 50 (4), 481-490.

Sheppard, M., & Mayo Jr, J. B. (2013). The social construction of gender and sexuality: Learning from two spirit traditions . The Social Studies, 104 (6), 259-270.

Nanda, S. (1986). The Hijras of India: Cultural and individual dimensions of an institutionalized third gender role . Journal of Homosexuality, 11 (3-4), 35-54.

Aznar, A., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2015). Gender and age differences in parent–child emotion talk . British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33 (1), 148-155.

Lindgren, C. (2010). Pink Brain Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps . Acta Paediatrica, 99 (7), 1108-1108.

Karen Blair, Ph.D. , is an assistant professor of psychology at Trent University. She researches the social determinants of health throughout the lifespan within the context of relationships.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Get More Zócalo

Eclectic but curated. Smart without snark. Ideas journalism with a head and heart.

Zócalo Podcasts

Parenting Beyond the Gender Binary

Neutrality guided me through their childhood. but did i prepare my trans kid for life outside our family’s orbit.

When Erinn M. Eichinger listened to the ’70s album Free to Be You and Me , she recognized a message about gender-neutral parenting at the heart of it. It guided her when, decades later, her own child came out as transgender. Eichinger and her child Skylar. Courtesy of author.

by Erinn M. Eichinger | August 5, 2024

Can we, and should we, ever really be neutral? In a new series, Zócalo explores the idea of neutrality —in politics, sports, gender, journalism, international law, and more. In this essay, writer Erinn M. Eichinger reflects on how gender-neutral parenting prepared her to raise her kids, especially her trans child.

Skylar was born a girl, meaning they were assigned female at birth by their doctors. Today, Skylar identifies as male. Their preferred pronouns are he/him or they/them.

I raised Skylar as a girl. Up until a few years ago, they were, in my mind, unequivocally my daughter. Long hair and pretty dresses were their thing, but so were hunting for bugs, dreaming of dinosaurs, and digging in the dirt. I didn’t expect Skylar to play with dolls, or for them to be a princess on Halloween when they preferred Legos and Dracula costumes. Skylar’s preferences often swung toward what society might deem boyish things, but then again, they were a sucker for a skirt they could really twirl in.

Skylar didn’t come to me as a young child and proclaim that they were not a girl or that they felt like they were born into the wrong body. In fact, there were no conversations with Skylar regarding them not feeling in alignment with the sex and gender of their birth until puberty.

When Skylar did begin to express feelings of being transgender, it wasn’t easy for me. I felt incredible internal resistance, even loss. But I also knew that Skylar did feel safe enough to explore these feelings and to lean on me for guidance and support.

Now, Skylar is moving out, leaving California for Oregon. As they get ready to launch, it makes me question if my parenting, which looking back, might be labeled gender neutral , has prepared them for a world outside our family’s orbit—a world where gender roles are fraught with divisiveness.

The word neutral has many meanings: indifferent, impartial, disengaged. When you talk about neutrality in terms of parenting, it means something completely different. In the past few years, there has been a growing resurrection of the conversation around gender-neutral or gender-responsive parenting.

This kind of parenting was already a thing by the early ’70s, when I was a quintessential girl: shy and bookish, I hated sports, loved my dolls, and could spend a perfect summer afternoon watching soap operas with my grandma. My mom was an interesting mix of traditional and hippie who insisted on good manners and “ladylike” behavior, but who also wanted me and my sister to be original thinkers and stand on our own two feet.

When Skylar was growing up, Erin M. Eichinger writes that she always encouraged them to be “free” to be themselves: someone who loved to twirl in skirts and hunt for bugs.

Eichinger set out to raise Skylar (pictured) and her other three children with an awareness of gender identities that are “unique, fluid, and complex.”

Looking back, Eichinger writes that she wouldn’t change much about her parenting style, aside from being even more conscious and intentional around language and her attitudes surrounding gender roles.

When I was around 5, Mom gave me a copy of the children’s album Free to Be You and Me, which came out in 1972.

At the heart of the album was a message about gender-neutral parenting that encouraged kids and adults to see themselves in ways that broke loose from rigid notions of what it meant to be a boy or a girl. Boys can play with dolls. Girls can run fast. And, it’s okay for all of us to cry. Tapping into the Gloria Steinem-style feminism of the time, the album was a reaction to a hyper-gendered postwar America, where marketers painted everything in shades of pink or blue.

Free to Be You and Me provided a new vision of how things could be. I wore that record out, playing it on my white suitcase record player until I knew every song and story by heart.

About 25 years passed from the first time I listened to the album to when I became a mom myself. My approach to parenting my three step kids and Skylar, my first and only born, turned out to be fairly gender neutral. I taught my kids that boys and girls are a lot more alike than they are different. I encouraged them to be “free” to wear whatever they like; play however they like and be however they like.

I was winging it, with Free to Be You and Me as my compass.

Skylar hopes to be a parent themselves one day, and their thoughts on gender-neutral parenting are interesting: “I would keep things neutral when it comes to my child. I would use neutral pronouns, names, toys, and clothes.”

While Skylar realizes that total neutrality would be an impossibility, they would try, at least with those in the child’s inner circle, to maintain as neutral an environment as possible.

If this caused confusion, once the child had more contact with people outside their family group, Skylar feels that it could be a launching point for communication. “It would be a way to talk to them about gender from a young age, like kids who are raised always knowing they are adopted. They may not understand the concept when they are little, but once they do, there is no fear around it.”

Many people seem to think gender neutrality is something completely new and foreign.

What I’ve come to believe is that we have a generation of young people who are giving us a new lexicon surrounding gender. They are not describing a new phenomenon; they are, as historian Laura Lovett has noted, “resuscitating an old movement, not creating a new one.”

As far as public discussions around gender go, we have made great strides, and yet with that, comes pushback. In 2024, there have been more than 600 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in 43 states. In Florida, the state board of medicine is acting to block any kind of gender-affirming care for people under the age of 18, even with parental consent. In California, Elon Musk announced he’d be moving his Space X headquarters out of the state. This, in response to a bill that bans teachers from forcibly outing transgender students to their families. Musk is the father of a transgender daughter from whom he is estranged, and he blames her California private school education for “making her trans.”

Gender roles are imprecise, constantly changing, and ever-evolving. Because of this nebulous quality, they are often confusing and even misleading. As a pushback to what they see as socially imposed rules, some parents today are taking the concept of neutrality in parenting even further, a strict concealment of their baby’s gender from all but a small circle of caretakers. In doing so, they aim to make the child’s formative years completely free of gender markers or stereotypes. Think gender-neutral names, clothing, and toys. Definitely no gender-reveal parties. At some point, the thinking goes, the child will naturally express their gender with no need for any outside influence.

This reminds me of the widely read short story about “Baby X,” a fictional child whose gender is revealed to only a select few. The piece was published in Ms. magazine in 1978, just a few years after Free to Be You and Me —and it pushed readers to question the impact gender roles have on children and society at large.

While my approach of raising children with an awareness of gender identities that are unique, fluid, and complex feels right, the idea of raising kids with total neutrality seems unnecessary to me. I wonder if the practice could be needlessly confusing, leading to misinterpretations and misunderstanding for the child and those who love them, not to mention the level of watchfulness required on the parent’s part.

If I had the chance to raise Skylar again, I am not sure I would change my parenting style. Maybe I would be more conscious around language or more intentional about my attitudes surrounding gender roles.

Here’s the tricky part about raising kids: If you do a good job, the reward is that they become one of your favorite people in the whole world. The other reward is that they learn to stand on their own two feet. And then, they leave you.

So, you help them leave. You break your own heart in service of their future and you wonder if you have prepared them for the world out there.

So, here I am, helping my child take their next step. As I look into the proverbial rearview mirror, to the kid Skylar was, and to the adult they are becoming, I can only hope I prepared them well. I hope too, that when they look into the mirror, they see what I see: a funny, loving, wicked smart, and compassionate person.

What else could a parent want for their child?

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

The Classic Journal

A journal of undergraduate writing and research, from wip at uga, feminist thought and transcending the gender binary: a discussion, feminist thought and transcending the gender binary, a discussion.

by Rowan Thompson

I analyze the role and influence of people identifying outside of the traditional gender binary within modern feminist discourse. Using concepts discussed in feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal book The Second Sex , I argue that the traditional gender binary is a tool with which cisgender men uphold their own supremacy and that wider acceptance of non-binary people into feminist circles will serve to challenge this power dynamic. To illustrate the value of non-binary peoples’ lived experiences to feminist philosophy, I will discuss hormonal, surgical, and social transitioning; differences in experiences depending on gender assigned at birth; and my own experience living as non-binary. It is my hope that my research and discussion will improve the reader’s understanding of non-binary identities and help to challenge the primacy of cisgender males, thereby breaking down gender essentialism and fostering a culture of acceptance for all genders.

KEYWORDS: non-binary, assigned male at birth, assigned female at birth, transition, gender binary

Since the inception of modern feminism, its leaders have made a name for themselves by breaking rules. As it rose out of aggressively patriarchal and colonialist Europe and the Americas, women fought for suffrage and rebelled against laws confining them to home and hearth. Later, with the advent of the birth-control pill, feminists rallied for women’s reproductive rights, flying in the face of ancient attitudes about women’s roles as child-bearers. Later still, feminism challenged hierarchies centering white men and sought to address the lived experiences of women of color, disabled women, and queer women. Even today, popular culture is facing a reckoning wherein men are being held accountable for sexual assault, and the common expectation that women should tolerate sexual abuse is being dismantled. However, a certain rule lies more or less unbroken by popular feminism, and even the most radical thinkers have only managed to chip away at it. The binary of man and woman originated in pre-Biblical times and mostly centered around observable biological sex, but we as a society have constructed a highly limiting set of roles hinging on this binary that does not allow room for the infinite range of human self-expression. While the concept of people identifying and living entirely outside of the gender binary is an ancient one, dualist and hierarchical thought, especially in the West, has all but erased it. Transgender people have made great strides in recent years, but those in the public eye are typically gender-conforming and fit neatly into this binary. More recently, however, societies worldwide have seen a boom in people identifying as non-binary, a broad identity encompassing genders that are neither wholly male nor female, including but not limited to genderqueer, gender fluid, and agender (Richards 2016). Much has been said about these people and their place within feminist activism. I argue that the gender binary is a tool used by cisgender men to establish their own primacy at the expense of other genders and that, by embracing non-binary identities in all their forms, feminists can challenge and dismantle a power structure that stifles every person’s right to self-determination.

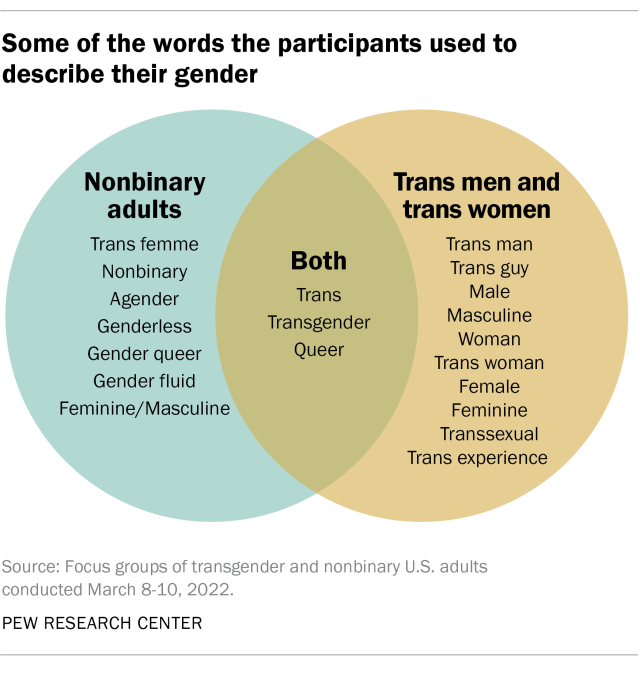

As it is understood today, to be non-binary simply means to identify as neither male nor female. This identity falls under the transgender label, though not all non-binary individuals refer to themselves as trans. It is a common mistake to equate this identity to gender non-conformity, as cisgender people can be gender-nonconforming. Furthermore, like trans people who fall within the binary, non-binary people frequently undergo hormone replacement therapy and surgery with the intent of removing their original secondary-sex characteristics rather than obtaining those of the “opposite” sex. However, unlike those who consider themselves strictly man or woman, whether cis or trans, non-binary people frequently employ intentional androgyny and the blending of gender signifiers such as fashion and makeup. To complicate matters further, not all non-binary individuals are digestibly genderless in their presentation; some align very closely in their dress and mannerisms with their assigned gender at birth. The mere existence of this identity dismantles much of what we have been taught from a very young age—that genitals determine gender and that the clothes we choose reflect it. However, cursory research shows that this binary is not the natural law that the popular paradigm says it is. Rather than assuming gender roles by sex assigned at birth, many cultures around the world have specific terms for people that fill gender-variant roles. Examples include “two-spirit,” meaning that one embodies the masculine and the feminine, which can be found in multiple Native American societies; or hijras, which in Hindu culture is a blanket term for trans and gender non-conforming individuals. Thus, the gender binary is both Western and colonialist in its application, and it effectively erases everything outside the archetypal cisgender male and what we perceive as its inverse.

A dualist model of the mind versus the body was originally conceived by the philosopher Rene Descartes, but the feminist scholar Simone de Beauvoir further modified and expounded upon dualist concepts in her seminal work The Second Sex. De Beauvoir famously stated that, in their power as knowledge-makers, men established themselves as the Self, the Absolute, and made women the Other. However, she specifically contrasted her model with that of poles, stating “man represents both positive and the neutral,” while women are relegated to the negative, defined only in terms of their non-maleness (163). When we expand our definition of gender to include a sliding scale between male and female as well as genders that fall off that scale entirely, the cisgender man does not lose his status as the Self, but the Other only grows larger until it swallows easily over half of humanity. It then becomes difficult to deny that Selfhood does not represent the total of the human experience but is rather manufactured by unearned power and deliberate erasure of the Other. This power dynamic born out of a social construct, much like racism and colonialism, is exactly the type that feminism should concern itself with dismantling, so that we may gain a clearer image of humankind’s true nature.

As feminism seeks to liberate women from sexist oppression, few would dispute that those designated “female” by society belong within the movement and indeed have a vested interest in its success. However, while much of misogyny intertwines with sexism—that is, discrimination based on natal sex—not every person with a uterus, ovaries, and the typically corresponding anatomy identifies as female or wants to assume a “feminine” role. These two statements are not at odds with each other, as it may seem, and feminism should aim to eliminate oppression rooted in both sex assigned at birth and the roles we assume as a result of it. However, non-binary people assigned female at birth (or “AFAB,” as it is known in the trans community) often find themselves in a cruel double bind; they can either present as typical women to their comfort level and face misogyny or they can transition away from female to affirm their genders and face transphobia. While misogyny is a far broader issue than can be adequately discussed here, we can at least mitigate transphobic attitudes with discussion of what it means to transition from female to something else.

A common misconception around non-binary AFAB people is that they are simply gender non-conforming women, butch lesbians, or “tomboys.” While all these identities are perfectly valid, they do not capture the AFAB’s lack of connection to womanhood in general. Some do refer to themselves as lesbians if they are attracted to women, and they may consider “lesbian” to be both their sexuality and their gender. However, they do not think of themselves as women in the way cisgender women do, and they may transition, even to the same degree that a trans man might, without identifying as male. Common but non-permanent methods of transitioning include breast-binding, short haircuts, and face-contouring to create a more masculine appearance. (I personally employ face-contouring and binding on a daily basis.) Less commonly, double mastectomies (“top surgeries”) are performed on such individuals, and testosterone can be taken in widely varying doses to achieve as androgynous or as masculine a body and voice as one desires. All in all, this identity is a complex one with an even more complex relationship with feminism.

One might think that AFAB individuals would be wholeheartedly welcome in feminist circles regardless of identity, but some unfortunate blind spots have led to rifts between the two groups. Namely, mainstream feminism has a tendency toward cissexism, using imagery of vaginas and uteri alongside slogans about “girl power” and “sisterhood.” AFAB non-binary people also frequently find themselves tacked onto “women-only” gatherings, as if they still fundamentally count as women. As stated by Deidre Olsen for Argot Magazine, “genital-based catchphrases like “The Future Is Female,” “Viva la Vulva” and “Pussy Grabs Back” in activism only forward the interests of cisgender women” (2017). This aggressively gendered atmosphere leaves AFABs feeling alienated and shoved into an ill-fitting box for the convenience of others. Feminists have a great deal to learn from such people. Those perceived as women by wider society face immense pressure to fall in line, be “ladylike,” submit to men, and not make waves. Those who not only reject womanhood but identify and present as something neither male nor female are helping to deconstruct what it means to be either. The self-knowledge needed to forgo roles entirely and write one’s own script, especially in the face of constant societal shame, is a skill that feminism as a whole can use. To exist outside the binary in a society that expects one’s compliance and submission is a radical show of self-determination, a refusal to uphold the societal Self by playing the traditional role of the Other. By uplifting their AFAB friends, feminists can show people of all genders that their bodies and minds are theirs alone and can be molded in whatever way affirms them.

Contrariwise, people assigned male at birth (AMAB) can be non-binary in as wide a variety of ways as those assigned female. However, in feminist circles, they occupy a much more fragile space. While the people assigned female are generally embraced by feminism, regardless of their identity, even open-minded activists may regard AMABs with some suspicion and unease. However, further education on the lives of such people is the key to easing the tensions and dispelling the confusion that contribute to this divide. Non-binary AMABs and AFABs typically feel similarly about their gender presentation; they most often want to hide or to remove secondary-sex characteristics without necessarily taking on others. However, we already conceive of androgyny as being slightly masculine, harkening back to de Beauvoir and the status of male as neutral. Someone already assigned male but who feels disconnected from manhood must reckon with this dissonance, and, in expressing their gender through traditionally feminine dress or mannerisms, they will likely be read as a transgender woman. It is perhaps for this reason that a small majority of those who identify as non-binary are AFAB, while AMAB individuals find it much harder to settle on a comfortable middle ground in their presentation. That said, many such people embrace a more masculine presentation, are highly feminine, or balance the two to their comfort level; they are no less non-binary for it. To accentuate their style, some wear makeup or jewelry as well as more overtly feminine dress such as skirts and high heels. Options for medical transition are as varied as they are for AFAB people (perhaps more so, as vaginoplasty is more possible with current medicine than phalloplasty), including any combination of estrogen treatment, breast implants, facial surgeries, and laser hair removal.

A non-binary AMAB is distinct from a trans woman and should not be referred to as such, regardless of one’s degree of transition, but both groups would, in an ideal world, be welcomed by feminist circles. The reality, unfortunately, is that feminists tend to cast a critical eye on people who lived most of their life as male entering their spaces, as trans activist Emi Koyama details in her essay “A Transfeminist Manifesto,” citing the widespread rejection of trans women by radical feminist circles (2001). To a small degree this is understandable, as AMABs do not experience oppression based on their assigned sex at birth. However, some of the basic goals of feminism, such as undoing of toxic masculinity and reducing the stigma around “feminine” clothing and mannerisms, are hard at work in the non-binary community. Wider society has a difficult time digesting the fact that anyone born male would “step down” from that place of privilege, so making oneself undefinable by gender and the power vested in maleness is a radical act. Feminism promotes the same self-confidence and willingness to push boundaries that enable non-binary AMABs to live their truth. Bringing more of them into the fold and welcoming them would signify feminism’s ability to adapt and to address its own preconceptions and to become a place from which people can draw the strength to live authentically.

While the endgame for many non-binary people is medical transition to ease bodily dysphoria, surgery is prohibitively expensive. Thus, most rely on clothing and general personal style to express their detachment from the binary and to present in the way they feel comfortable. For example, as an obviously female non-binary person, I avoid short skirts and tight dresses and specifically choose loose-fitting, more masculine clothes. However, because the non-binary community is, almost as a rule, layered with contradictions, not everybody dresses in an entirely non-conforming manner, and it is popular to combine highly masculine and highly feminine components in a single outfit. For another personal example, I frequently accentuate very masculine outfits with nail polish and makeup, solely because I find it aesthetically pleasing. Other people may bind their breasts and wear a dress at the same time or wear both a skirt and a full beard. To further complicate the matter, some non-binary people are indistinguishable from cisgender men and women and conform more or less completely to their assigned genders. I have known such people personally, and all were equally non-binary. However, under patriarchy, such people would never have a choice in the matter, and all deviation from gendered fashion would be ruthlessly punished, as it is to varying degrees today. If feminism aims to combat gendered expectations of self-expression, feminists must un-gender clothing for themselves and learn not to assume gender based on appearance. This will take away the power of categorization and the ability of men to identify Selves and Others on sight, fostering an environment of deeper engagement with one another free of assumptions.

I do not argue lightly for dispensing with the gender binary. Not only is this particular binary ingrained in nearly every facet of our society, but human beings are heavily geared towards simplicity. As de Beauvoir put it, “Otherness is a fundamental category of human thought” (163). Dismantling this system would be radical, and, as it stands, it seems impossible. Indeed, it is rooted in a biological reality we cannot deny—that there are people with one reproductive system and people with another, people we named males and females. It is to this concept that the hardline traditionalists point when the topic of trans identity is at hand, asserting that gender is as immutable as sex. Radical feminists, ironically, take a similarly essentialist stance when discussing trans identities. Rebecca Reilly-Cooper at the University of Warwick argues that gender is entirely socially constructed to oppress women, and that “To call yourself non-binary or genderfluid while demanding that others call themselves cisgender is to insist that the vast majority of humans must stay in their boxes, because you identify as boxless” (2016.)

These arguments, however, unravel upon closer examination. For example, recent discoveries have found that chromosomes are not nearly as unambiguous as we once thought, with countless variations possible among people with the same external anatomy. In addition, as with all things in biology, external sex is not an absolute, considering intersex conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia or androgen insensitivity syndrome (Jones 2018). Furthermore, the radical feminist concept of gender as a weapon used against women is harshly limiting. Gender, while complex and intimidating to explore, can be a powerful source of self-love and happiness. It stems not from genitals or a patriarchal society, but from every message about gender we retain as we grow, how we come to think about our bodies, and how we want to present ourselves to the world.

With the advent of social media and with information constantly available at our fingertips, it should come as no surprise that people are finding gender identity to be far more complicated than in decades past. The author and philosopher Donna Haraway imagined that all types of binaries would be broken down as technology advanced and that now “the dichotomies between mind and body, nature and culture, men and women…are all in question ideologically” (347). It should come as no surprise that, as people reach out to one another and discover countless new ways of being, they also reflect upon what they learn and explore their identities without fear.

Feminism was originally, and in some cases still is, considered to stand for the political, social, and economic equality of the sexes. While the sexes become more and more equal on paper, the public does not always follow; therefore, it has become important to remake feminism routinely in order to fix whatever problems present themselves. Now, as the binary between men and women blurs, it is necessary to rethink how feminism conceives gender, how gender is used to grant power, and how we as feminists can ally ourselves with those who have been Othered by a society in which the cisgender man is the Self. Even while vocal minorities protest and hold fast to their feminist theory rooted in dualism and bio-essentialism, feminism as a whole must embrace non-binary existence. Doing so will pave the way for freedom of all people to live as their fullest, most authentic selves.

Works Cited

De Beauvoir, Simone. “The Second Sex.” Feminist Theory: A Reader. Eds. Wendy Kolmar and Frances Bartowski. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2013.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” Feminist Theory: A Reader. Eds. Wendy Kolmar and Frances Bartowski. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2013.

Jones, Tiffany. “Intersex Studies: A Systematic Review of International Health Literature.” SAGE OPEN , vol. 8, no. 2. EBSCOhost , doi:10.1177/2158244017745577.

Koyama, Emi. “The Transfeminist Manifesto.” Catching A Wave: Reclaiming Feminism for the 21 st Century. Eds. Rory Dicker and Alison Piepmeier. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001.

Olsen, Deidre. “The Future Is Not Female – It Is Two-Spirit, Trans and Non-Binary.” Argot Magazine , Argot Magazine, 5 June 2017, www.argotmagazine.com/first-person-and-perspectives/the-future-is-not-female-it-is-two-spirit-trans-and-non-binary .

Reilly-Cooper, Rebecca. “The Idea That Gender Is a Spectrum Is a New Gender Prison.” Aeon . Ed. Nigel Warburton. Aeon, 28 June 2016, aeon.co/essays/the-idea-that-gender-is-a-spectrum-is-a-new-gender-prison .

Richards, Christina, et al. “Non-Binary or Genderqueer Genders.” International Review of Psychiatry , vol. 28, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 95–102. EBSCOhost , doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446.

Citation Style: MLA

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender

Feminism is said to be the movement to end women’s oppression (hooks 2000, 26). One possible way to understand ‘woman’ in this claim is to take it as a sex term: ‘woman’ picks out human females and being a human female depends on various biological and anatomical features (like genitalia). Historically many feminists have understood ‘woman’ differently: not as a sex term, but as a gender term that depends on social and cultural factors (like social position). In so doing, they distinguished sex (being female or male) from gender (being a woman or a man), although most ordinary language users appear to treat the two interchangeably. In feminist philosophy, this distinction has generated a lively debate. Central questions include: What does it mean for gender to be distinct from sex, if anything at all? How should we understand the claim that gender depends on social and/or cultural factors? What does it mean to be gendered woman, man, or genderqueer? This entry outlines and discusses distinctly feminist debates on sex and gender considering both historical and more contemporary positions.

1.1 Biological determinism

1.2 gender terminology, 2.1 gender socialisation, 2.2 gender as feminine and masculine personality, 2.3 gender as feminine and masculine sexuality, 3.1.1 particularity argument, 3.1.2 normativity argument, 3.2 is sex classification solely a matter of biology, 3.3 are sex and gender distinct, 3.4 is the sex/gender distinction useful, 4.1.1 gendered social series, 4.1.2 resemblance nominalism, 4.2.1 social subordination and gender, 4.2.2 gender uniessentialism, 4.2.3 gender as positionality, 5. beyond the binary, 6. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the sex/gender distinction..

The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ mean different things to different feminist theorists and neither are easy or straightforward to characterise. Sketching out some feminist history of the terms provides a helpful starting point.

Most people ordinarily seem to think that sex and gender are coextensive: women are human females, men are human males. Many feminists have historically disagreed and have endorsed the sex/ gender distinction. Provisionally: ‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features (chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features); ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors (social role, position, behaviour or identity). The main feminist motivation for making this distinction was to counter biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny.

A typical example of a biological determinist view is that of Geddes and Thompson who, in 1889, argued that social, psychological and behavioural traits were caused by metabolic state. Women supposedly conserve energy (being ‘anabolic’) and this makes them passive, conservative, sluggish, stable and uninterested in politics. Men expend their surplus energy (being ‘katabolic’) and this makes them eager, energetic, passionate, variable and, thereby, interested in political and social matters. These biological ‘facts’ about metabolic states were used not only to explain behavioural differences between women and men but also to justify what our social and political arrangements ought to be. More specifically, they were used to argue for withholding from women political rights accorded to men because (according to Geddes and Thompson) “what was decided among the prehistoric Protozoa cannot be annulled by Act of Parliament” (quoted from Moi 1999, 18). It would be inappropriate to grant women political rights, as they are simply not suited to have those rights; it would also be futile since women (due to their biology) would simply not be interested in exercising their political rights. To counter this kind of biological determinism, feminists have argued that behavioural and psychological differences have social, rather than biological, causes. For instance, Simone de Beauvoir famously claimed that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, and that “social discrimination produces in women moral and intellectual effects so profound that they appear to be caused by nature” (Beauvoir 1972 [original 1949], 18; for more, see the entry on Simone de Beauvoir ). Commonly observed behavioural traits associated with women and men, then, are not caused by anatomy or chromosomes. Rather, they are culturally learned or acquired.

Although biological determinism of the kind endorsed by Geddes and Thompson is nowadays uncommon, the idea that behavioural and psychological differences between women and men have biological causes has not disappeared. In the 1970s, sex differences were used to argue that women should not become airline pilots since they will be hormonally unstable once a month and, therefore, unable to perform their duties as well as men (Rogers 1999, 11). More recently, differences in male and female brains have been said to explain behavioural differences; in particular, the anatomy of corpus callosum, a bundle of nerves that connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres, is thought to be responsible for various psychological and behavioural differences. For instance, in 1992, a Time magazine article surveyed then prominent biological explanations of differences between women and men claiming that women’s thicker corpus callosums could explain what ‘women’s intuition’ is based on and impair women’s ability to perform some specialised visual-spatial skills, like reading maps (Gorman 1992). Anne Fausto-Sterling has questioned the idea that differences in corpus callosums cause behavioural and psychological differences. First, the corpus callosum is a highly variable piece of anatomy; as a result, generalisations about its size, shape and thickness that hold for women and men in general should be viewed with caution. Second, differences in adult human corpus callosums are not found in infants; this may suggest that physical brain differences actually develop as responses to differential treatment. Third, given that visual-spatial skills (like map reading) can be improved by practice, even if women and men’s corpus callosums differ, this does not make the resulting behavioural differences immutable. (Fausto-Sterling 2000b, chapter 5).

In order to distinguish biological differences from social/psychological ones and to talk about the latter, feminists appropriated the term ‘gender’. Psychologists writing on transsexuality were the first to employ gender terminology in this sense. Until the 1960s, ‘gender’ was often used to refer to masculine and feminine words, like le and la in French. However, in order to explain why some people felt that they were ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’, the psychologist Robert Stoller (1968) began using the terms ‘sex’ to pick out biological traits and ‘gender’ to pick out the amount of femininity and masculinity a person exhibited. Although (by and large) a person’s sex and gender complemented each other, separating out these terms seemed to make theoretical sense allowing Stoller to explain the phenomenon of transsexuality: transsexuals’ sex and gender simply don’t match.

Along with psychologists like Stoller, feminists found it useful to distinguish sex and gender. This enabled them to argue that many differences between women and men were socially produced and, therefore, changeable. Gayle Rubin (for instance) uses the phrase ‘sex/gender system’ in order to describe “a set of arrangements by which the biological raw material of human sex and procreation is shaped by human, social intervention” (1975, 165). Rubin employed this system to articulate that “part of social life which is the locus of the oppression of women” (1975, 159) describing gender as the “socially imposed division of the sexes” (1975, 179). Rubin’s thought was that although biological differences are fixed, gender differences are the oppressive results of social interventions that dictate how women and men should behave. Women are oppressed as women and “by having to be women” (Rubin 1975, 204). However, since gender is social, it is thought to be mutable and alterable by political and social reform that would ultimately bring an end to women’s subordination. Feminism should aim to create a “genderless (though not sexless) society, in which one’s sexual anatomy is irrelevant to who one is, what one does, and with whom one makes love” (Rubin 1975, 204).

In some earlier interpretations, like Rubin’s, sex and gender were thought to complement one another. The slogan ‘Gender is the social interpretation of sex’ captures this view. Nicholson calls this ‘the coat-rack view’ of gender: our sexed bodies are like coat racks and “provide the site upon which gender [is] constructed” (1994, 81). Gender conceived of as masculinity and femininity is superimposed upon the ‘coat-rack’ of sex as each society imposes on sexed bodies their cultural conceptions of how males and females should behave. This socially constructs gender differences – or the amount of femininity/masculinity of a person – upon our sexed bodies. That is, according to this interpretation, all humans are either male or female; their sex is fixed. But cultures interpret sexed bodies differently and project different norms on those bodies thereby creating feminine and masculine persons. Distinguishing sex and gender, however, also enables the two to come apart: they are separable in that one can be sexed male and yet be gendered a woman, or vice versa (Haslanger 2000b; Stoljar 1995).

So, this group of feminist arguments against biological determinism suggested that gender differences result from cultural practices and social expectations. Nowadays it is more common to denote this by saying that gender is socially constructed. This means that genders (women and men) and gendered traits (like being nurturing or ambitious) are the “intended or unintended product[s] of a social practice” (Haslanger 1995, 97). But which social practices construct gender, what social construction is and what being of a certain gender amounts to are major feminist controversies. There is no consensus on these issues. (See the entry on intersections between analytic and continental feminism for more on different ways to understand gender.)

2. Gender as socially constructed

One way to interpret Beauvoir’s claim that one is not born but rather becomes a woman is to take it as a claim about gender socialisation: females become women through a process whereby they acquire feminine traits and learn feminine behaviour. Masculinity and femininity are thought to be products of nurture or how individuals are brought up. They are causally constructed (Haslanger 1995, 98): social forces either have a causal role in bringing gendered individuals into existence or (to some substantial sense) shape the way we are qua women and men. And the mechanism of construction is social learning. For instance, Kate Millett takes gender differences to have “essentially cultural, rather than biological bases” that result from differential treatment (1971, 28–9). For her, gender is “the sum total of the parents’, the peers’, and the culture’s notions of what is appropriate to each gender by way of temperament, character, interests, status, worth, gesture, and expression” (Millett 1971, 31). Feminine and masculine gender-norms, however, are problematic in that gendered behaviour conveniently fits with and reinforces women’s subordination so that women are socialised into subordinate social roles: they learn to be passive, ignorant, docile, emotional helpmeets for men (Millett 1971, 26). However, since these roles are simply learned, we can create more equal societies by ‘unlearning’ social roles. That is, feminists should aim to diminish the influence of socialisation.

Social learning theorists hold that a huge array of different influences socialise us as women and men. This being the case, it is extremely difficult to counter gender socialisation. For instance, parents often unconsciously treat their female and male children differently. When parents have been asked to describe their 24- hour old infants, they have done so using gender-stereotypic language: boys are describes as strong, alert and coordinated and girls as tiny, soft and delicate. Parents’ treatment of their infants further reflects these descriptions whether they are aware of this or not (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 32). Some socialisation is more overt: children are often dressed in gender stereotypical clothes and colours (boys are dressed in blue, girls in pink) and parents tend to buy their children gender stereotypical toys. They also (intentionally or not) tend to reinforce certain ‘appropriate’ behaviours. While the precise form of gender socialization has changed since the onset of second-wave feminism, even today girls are discouraged from playing sports like football or from playing ‘rough and tumble’ games and are more likely than boys to be given dolls or cooking toys to play with; boys are told not to ‘cry like a baby’ and are more likely to be given masculine toys like trucks and guns (for more, see Kimmel 2000, 122–126). [ 1 ]

According to social learning theorists, children are also influenced by what they observe in the world around them. This, again, makes countering gender socialisation difficult. For one, children’s books have portrayed males and females in blatantly stereotypical ways: for instance, males as adventurers and leaders, and females as helpers and followers. One way to address gender stereotyping in children’s books has been to portray females in independent roles and males as non-aggressive and nurturing (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 35). Some publishers have attempted an alternative approach by making their characters, for instance, gender-neutral animals or genderless imaginary creatures (like TV’s Teletubbies). However, parents reading books with gender-neutral or genderless characters often undermine the publishers’ efforts by reading them to their children in ways that depict the characters as either feminine or masculine. According to Renzetti and Curran, parents labelled the overwhelming majority of gender-neutral characters masculine whereas those characters that fit feminine gender stereotypes (for instance, by being helpful and caring) were labelled feminine (1992, 35). Socialising influences like these are still thought to send implicit messages regarding how females and males should act and are expected to act shaping us into feminine and masculine persons.

Nancy Chodorow (1978; 1995) has criticised social learning theory as too simplistic to explain gender differences (see also Deaux & Major 1990; Gatens 1996). Instead, she holds that gender is a matter of having feminine and masculine personalities that develop in early infancy as responses to prevalent parenting practices. In particular, gendered personalities develop because women tend to be the primary caretakers of small children. Chodorow holds that because mothers (or other prominent females) tend to care for infants, infant male and female psychic development differs. Crudely put: the mother-daughter relationship differs from the mother-son relationship because mothers are more likely to identify with their daughters than their sons. This unconsciously prompts the mother to encourage her son to psychologically individuate himself from her thereby prompting him to develop well defined and rigid ego boundaries. However, the mother unconsciously discourages the daughter from individuating herself thereby prompting the daughter to develop flexible and blurry ego boundaries. Childhood gender socialisation further builds on and reinforces these unconsciously developed ego boundaries finally producing feminine and masculine persons (1995, 202–206). This perspective has its roots in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, although Chodorow’s approach differs in many ways from Freud’s.

Gendered personalities are supposedly manifested in common gender stereotypical behaviour. Take emotional dependency. Women are stereotypically more emotional and emotionally dependent upon others around them, supposedly finding it difficult to distinguish their own interests and wellbeing from the interests and wellbeing of their children and partners. This is said to be because of their blurry and (somewhat) confused ego boundaries: women find it hard to distinguish their own needs from the needs of those around them because they cannot sufficiently individuate themselves from those close to them. By contrast, men are stereotypically emotionally detached, preferring a career where dispassionate and distanced thinking are virtues. These traits are said to result from men’s well-defined ego boundaries that enable them to prioritise their own needs and interests sometimes at the expense of others’ needs and interests.

Chodorow thinks that these gender differences should and can be changed. Feminine and masculine personalities play a crucial role in women’s oppression since they make females overly attentive to the needs of others and males emotionally deficient. In order to correct the situation, both male and female parents should be equally involved in parenting (Chodorow 1995, 214). This would help in ensuring that children develop sufficiently individuated senses of selves without becoming overly detached, which in turn helps to eradicate common gender stereotypical behaviours.

Catharine MacKinnon develops her theory of gender as a theory of sexuality. Very roughly: the social meaning of sex (gender) is created by sexual objectification of women whereby women are viewed and treated as objects for satisfying men’s desires (MacKinnon 1989). Masculinity is defined as sexual dominance, femininity as sexual submissiveness: genders are “created through the eroticization of dominance and submission. The man/woman difference and the dominance/submission dynamic define each other. This is the social meaning of sex” (MacKinnon 1989, 113). For MacKinnon, gender is constitutively constructed : in defining genders (or masculinity and femininity) we must make reference to social factors (see Haslanger 1995, 98). In particular, we must make reference to the position one occupies in the sexualised dominance/submission dynamic: men occupy the sexually dominant position, women the sexually submissive one. As a result, genders are by definition hierarchical and this hierarchy is fundamentally tied to sexualised power relations. The notion of ‘gender equality’, then, does not make sense to MacKinnon. If sexuality ceased to be a manifestation of dominance, hierarchical genders (that are defined in terms of sexuality) would cease to exist.

So, gender difference for MacKinnon is not a matter of having a particular psychological orientation or behavioural pattern; rather, it is a function of sexuality that is hierarchal in patriarchal societies. This is not to say that men are naturally disposed to sexually objectify women or that women are naturally submissive. Instead, male and female sexualities are socially conditioned: men have been conditioned to find women’s subordination sexy and women have been conditioned to find a particular male version of female sexuality as erotic – one in which it is erotic to be sexually submissive. For MacKinnon, both female and male sexual desires are defined from a male point of view that is conditioned by pornography (MacKinnon 1989, chapter 7). Bluntly put: pornography portrays a false picture of ‘what women want’ suggesting that women in actual fact are and want to be submissive. This conditions men’s sexuality so that they view women’s submission as sexy. And male dominance enforces this male version of sexuality onto women, sometimes by force. MacKinnon’s thought is not that male dominance is a result of social learning (see 2.1.); rather, socialization is an expression of power. That is, socialized differences in masculine and feminine traits, behaviour, and roles are not responsible for power inequalities. Females and males (roughly put) are socialised differently because there are underlying power inequalities. As MacKinnon puts it, ‘dominance’ (power relations) is prior to ‘difference’ (traits, behaviour and roles) (see, MacKinnon 1989, chapter 12). MacKinnon, then, sees legal restrictions on pornography as paramount to ending women’s subordinate status that stems from their gender.

3. Problems with the sex/gender distinction

3.1 is gender uniform.

The positions outlined above share an underlying metaphysical perspective on gender: gender realism . [ 2 ] That is, women as a group are assumed to share some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines their gender and the possession of which makes some individuals women (as opposed to, say, men). All women are thought to differ from all men in this respect (or respects). For example, MacKinnon thought that being treated in sexually objectifying ways is the common condition that defines women’s gender and what women as women share. All women differ from all men in this respect. Further, pointing out females who are not sexually objectified does not provide a counterexample to MacKinnon’s view. Being sexually objectified is constitutive of being a woman; a female who escapes sexual objectification, then, would not count as a woman.

One may want to critique the three accounts outlined by rejecting the particular details of each account. (For instance, see Spelman [1988, chapter 4] for a critique of the details of Chodorow’s view.) A more thoroughgoing critique has been levelled at the general metaphysical perspective of gender realism that underlies these positions. It has come under sustained attack on two grounds: first, that it fails to take into account racial, cultural and class differences between women (particularity argument); second, that it posits a normative ideal of womanhood (normativity argument).

Elizabeth Spelman (1988) has influentially argued against gender realism with her particularity argument. Roughly: gender realists mistakenly assume that gender is constructed independently of race, class, ethnicity and nationality. If gender were separable from, for example, race and class in this manner, all women would experience womanhood in the same way. And this is clearly false. For instance, Harris (1993) and Stone (2007) criticise MacKinnon’s view, that sexual objectification is the common condition that defines women’s gender, for failing to take into account differences in women’s backgrounds that shape their sexuality. The history of racist oppression illustrates that during slavery black women were ‘hypersexualised’ and thought to be always sexually available whereas white women were thought to be pure and sexually virtuous. In fact, the rape of a black woman was thought to be impossible (Harris 1993). So, (the argument goes) sexual objectification cannot serve as the common condition for womanhood since it varies considerably depending on one’s race and class. [ 3 ]

For Spelman, the perspective of ‘white solipsism’ underlies gender realists’ mistake. They assumed that all women share some “golden nugget of womanness” (Spelman 1988, 159) and that the features constitutive of such a nugget are the same for all women regardless of their particular cultural backgrounds. Next, white Western middle-class feminists accounted for the shared features simply by reflecting on the cultural features that condition their gender as women thus supposing that “the womanness underneath the Black woman’s skin is a white woman’s, and deep down inside the Latina woman is an Anglo woman waiting to burst through an obscuring cultural shroud” (Spelman 1988, 13). In so doing, Spelman claims, white middle-class Western feminists passed off their particular view of gender as “a metaphysical truth” (1988, 180) thereby privileging some women while marginalising others. In failing to see the importance of race and class in gender construction, white middle-class Western feminists conflated “the condition of one group of women with the condition of all” (Spelman 1988, 3).

Betty Friedan’s (1963) well-known work is a case in point of white solipsism. [ 4 ] Friedan saw domesticity as the main vehicle of gender oppression and called upon women in general to find jobs outside the home. But she failed to realize that women from less privileged backgrounds, often poor and non-white, already worked outside the home to support their families. Friedan’s suggestion, then, was applicable only to a particular sub-group of women (white middle-class Western housewives). But it was mistakenly taken to apply to all women’s lives — a mistake that was generated by Friedan’s failure to take women’s racial and class differences into account (hooks 2000, 1–3).

Spelman further holds that since social conditioning creates femininity and societies (and sub-groups) that condition it differ from one another, femininity must be differently conditioned in different societies. For her, “females become not simply women but particular kinds of women” (Spelman 1988, 113): white working-class women, black middle-class women, poor Jewish women, wealthy aristocratic European women, and so on.

This line of thought has been extremely influential in feminist philosophy. For instance, Young holds that Spelman has definitively shown that gender realism is untenable (1997, 13). Mikkola (2006) argues that this isn’t so. The arguments Spelman makes do not undermine the idea that there is some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines women’s gender; they simply point out that some particular ways of cashing out what defines womanhood are misguided. So, although Spelman is right to reject those accounts that falsely take the feature that conditions white middle-class Western feminists’ gender to condition women’s gender in general, this leaves open the possibility that women qua women do share something that defines their gender. (See also Haslanger [2000a] for a discussion of why gender realism is not necessarily untenable, and Stoljar [2011] for a discussion of Mikkola’s critique of Spelman.)

Judith Butler critiques the sex/gender distinction on two grounds. They critique gender realism with their normativity argument (1999 [original 1990], chapter 1); they also hold that the sex/gender distinction is unintelligible (this will be discussed in section 3.3.). Butler’s normativity argument is not straightforwardly directed at the metaphysical perspective of gender realism, but rather at its political counterpart: identity politics. This is a form of political mobilization based on membership in some group (e.g. racial, ethnic, cultural, gender) and group membership is thought to be delimited by some common experiences, conditions or features that define the group (Heyes 2000, 58; see also the entry on Identity Politics ). Feminist identity politics, then, presupposes gender realism in that feminist politics is said to be mobilized around women as a group (or category) where membership in this group is fixed by some condition, experience or feature that women supposedly share and that defines their gender.

Butler’s normativity argument makes two claims. The first is akin to Spelman’s particularity argument: unitary gender notions fail to take differences amongst women into account thus failing to recognise “the multiplicity of cultural, social, and political intersections in which the concrete array of ‘women’ are constructed” (Butler 1999, 19–20). In their attempt to undercut biologically deterministic ways of defining what it means to be a woman, feminists inadvertently created new socially constructed accounts of supposedly shared femininity. Butler’s second claim is that such false gender realist accounts are normative. That is, in their attempt to fix feminism’s subject matter, feminists unwittingly defined the term ‘woman’ in a way that implies there is some correct way to be gendered a woman (Butler 1999, 5). That the definition of the term ‘woman’ is fixed supposedly “operates as a policing force which generates and legitimizes certain practices, experiences, etc., and curtails and delegitimizes others” (Nicholson 1998, 293). Following this line of thought, one could say that, for instance, Chodorow’s view of gender suggests that ‘real’ women have feminine personalities and that these are the women feminism should be concerned about. If one does not exhibit a distinctly feminine personality, the implication is that one is not ‘really’ a member of women’s category nor does one properly qualify for feminist political representation.

Butler’s second claim is based on their view that“[i]dentity categories [like that of women] are never merely descriptive, but always normative, and as such, exclusionary” (Butler 1991, 160). That is, the mistake of those feminists Butler critiques was not that they provided the incorrect definition of ‘woman’. Rather, (the argument goes) their mistake was to attempt to define the term ‘woman’ at all. Butler’s view is that ‘woman’ can never be defined in a way that does not prescribe some “unspoken normative requirements” (like having a feminine personality) that women should conform to (Butler 1999, 9). Butler takes this to be a feature of terms like ‘woman’ that purport to pick out (what they call) ‘identity categories’. They seem to assume that ‘woman’ can never be used in a non-ideological way (Moi 1999, 43) and that it will always encode conditions that are not satisfied by everyone we think of as women. Some explanation for this comes from Butler’s view that all processes of drawing categorical distinctions involve evaluative and normative commitments; these in turn involve the exercise of power and reflect the conditions of those who are socially powerful (Witt 1995).

In order to better understand Butler’s critique, consider their account of gender performativity. For them, standard feminist accounts take gendered individuals to have some essential properties qua gendered individuals or a gender core by virtue of which one is either a man or a woman. This view assumes that women and men, qua women and men, are bearers of various essential and accidental attributes where the former secure gendered persons’ persistence through time as so gendered. But according to Butler this view is false: (i) there are no such essential properties, and (ii) gender is an illusion maintained by prevalent power structures. First, feminists are said to think that genders are socially constructed in that they have the following essential attributes (Butler 1999, 24): women are females with feminine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at men; men are males with masculine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at women. These are the attributes necessary for gendered individuals and those that enable women and men to persist through time as women and men. Individuals have “intelligible genders” (Butler 1999, 23) if they exhibit this sequence of traits in a coherent manner (where sexual desire follows from sexual orientation that in turn follows from feminine/ masculine behaviours thought to follow from biological sex). Social forces in general deem individuals who exhibit in coherent gender sequences (like lesbians) to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ and they actively discourage such sequencing of traits, for instance, via name-calling and overt homophobic discrimination. Think back to what was said above: having a certain conception of what women are like that mirrors the conditions of socially powerful (white, middle-class, heterosexual, Western) women functions to marginalize and police those who do not fit this conception.

These gender cores, supposedly encoding the above traits, however, are nothing more than illusions created by ideals and practices that seek to render gender uniform through heterosexism, the view that heterosexuality is natural and homosexuality is deviant (Butler 1999, 42). Gender cores are constructed as if they somehow naturally belong to women and men thereby creating gender dimorphism or the belief that one must be either a masculine male or a feminine female. But gender dimorphism only serves a heterosexist social order by implying that since women and men are sharply opposed, it is natural to sexually desire the opposite sex or gender.

Further, being feminine and desiring men (for instance) are standardly assumed to be expressions of one’s gender as a woman. Butler denies this and holds that gender is really performative. It is not “a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts follow; rather, gender is … instituted … through a stylized repetition of [habitual] acts ” (Butler 1999, 179): through wearing certain gender-coded clothing, walking and sitting in certain gender-coded ways, styling one’s hair in gender-coded manner and so on. Gender is not something one is, it is something one does; it is a sequence of acts, a doing rather than a being. And repeatedly engaging in ‘feminising’ and ‘masculinising’ acts congeals gender thereby making people falsely think of gender as something they naturally are . Gender only comes into being through these gendering acts: a female who has sex with men does not express her gender as a woman. This activity (amongst others) makes her gendered a woman.

The constitutive acts that gender individuals create genders as “compelling illusion[s]” (Butler 1990, 271). Our gendered classification scheme is a strong pragmatic construction : social factors wholly determine our use of the scheme and the scheme fails to represent accurately any ‘facts of the matter’ (Haslanger 1995, 100). People think that there are true and real genders, and those deemed to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ are not socially sanctioned. But, genders are true and real only to the extent that they are performed (Butler 1990, 278–9). It does not make sense, then, to say of a male-to-female trans person that s/he is really a man who only appears to be a woman. Instead, males dressing up and acting in ways that are associated with femininity “show that [as Butler suggests] ‘being’ feminine is just a matter of doing certain activities” (Stone 2007, 64). As a result, the trans person’s gender is just as real or true as anyone else’s who is a ‘traditionally’ feminine female or masculine male (Butler 1990, 278). [ 5 ] Without heterosexism that compels people to engage in certain gendering acts, there would not be any genders at all. And ultimately the aim should be to abolish norms that compel people to act in these gendering ways.