The Causes of the Economic Crisis, and Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression

- View HTML Version

- The Causes of the Economic Crisis, and Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression.pdf

- The Causes of the Economic Crisis, and Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression.epub

Stimulus or laissez-faire? That’s the essential debate about what to about financial crisis in our time. It was the same in the 1930s.

In this world before and after the Great Depression, there was a lone voice for sanity and freedom: Ludwig von Mises. He speaks in The Causes of the Economic Crisis , a collection of newly in print essays by Mises that have been very hard to come by, and are published for the first time in this format.

Here we have the evidence that the master economist foresaw and warned against the breakdown of the German mark, as well as the market crash of 1929 and the depression that followed.

He presents his business cycle theory in its most elaborate form, applies it to the prevailing conditions, and discusses the policies that governments undertake that make recessions worse. He recommends a path for monetary reform that would eliminate business cycles and provide the basis for a sustainable prosperity.

In foreseeing the interwar economic breakdown, Mises was nearly alone among his contemporaries. In 1923, he warned that central banks will not “stabilize” money; they will distort credit markets and generate booms and busts. In 1928, he departed dramatically from the judgment of his contemporaries and sounded an alarm: “every boom must one day come to an end.”

Then after the Great Depression hit, he wrote again in 1931. His essay was called: “The Causes of the Economic Crisis.” And the essays kept coming, in 1933 and 1946, each explaining that the business cycle results from central-bank generated loose money and cheap credit, and that the cycle can only be made worse by intervention.

Credit expansion cannot increase the supply of real goods. It merely brings about a rearrangement. It diverts capital investment away from the course prescribed by the state of economic wealth and market conditions. It causes production to pursue paths which it would not follow unless the economy were to acquire an increase in material goods. As a result, the upswing lacks a solid base. It is not real prosperity. It is illusory prosperity. It did not develop from an increase in economic wealth. Rather, it arose because the credit expansion created the illusion of such an increase. Sooner or later it must become apparent that this economic situation is built on sand.

Did the world listen? The German-speaking world knew his essays well, and he was considered a prophet, until the Nazis came to power and wiped out his legacy. In England, his student F.A. Hayek made the Austrian theory a presence in academic life.

In the popular mind, the media, and politics, however, it was Keynes who held sway, with his claim that the depression was the fault of the market, and that it can only be solved through government planning.

Just at the time he wanted to be fighting, Mises had to leave Austria, forced out by political events and the rising of the Nazis. He wrote from Geneva, his writings accessible to too few people. They were never translated into English until after his death. Even then, they were not circulated widely.

The sad result is that Mises is not given the credit he deserves for having warned about the coming depression, and having seen the solution. His writings were prolific and profound, but they were swallowed up in the rise of the total state and total war.

But today, we hear him speak again in this book.

Bettina B. Greaves did the translations. It is her view that in the essays, Mises provides the clearest explanation of the Great Depression ever written. Indeed, he is crystal clear: precise, patient, and thorough. It makes for a gripping read, especially given that we face many of the same problems today.

This book refutes the socialists and Keynesian, as well as anyone who believes that the printing press can provide a way out of trouble. Mises shows who was responsible for driving the world into economic calamity. It was the inevitable effects of the government’s monopoly over money and banking.

Just as in his attack on socialism, here he was brilliant and brave and prescient. Mises was there, before and after. He was writing about contemporary events. He issued the warnings that the world did not heed, the warnings we must heed today.

No content found

Ludwig von Mises was the acknowledged leader of the Austrian school of economic thought, a prodigious originator in economic theory, and a prolific author. Mises’s writings and lectures encompassed economic theory, history, epistemology, government, and political philosophy. His contributions to economic theory include important clarifications on the quantity theory of money, the theory of the trade cycle, the integration of monetary theory with economic theory in general, and a demonstration that socialism must fail because it cannot solve the problem of economic calculation. Mises was the first scholar to recognize that economics is part of a larger science in human action, a science that he called praxeology .

Wages, Unemployment, and Inflation 06/20/2024 • Mises Daily • Ludwig von Mises There is only one way that leads to an improvement of the standard of living for the wage-earning masses, viz., the increase in the amount of capital invested. All other methods, however popular they may be, are not only futile, but are actually detrimental to the well-being of those they allegedly want to benefit.

Governments Never Give Up Power Voluntarily 03/01/2024 • Mises Wire • Ludwig von Mises [A selection from Liberalism .] All those in positions of political power, all governments, all kings, and all republican authorities have always looked askance at private property. There is an...

The Real Meaning of Inflation and Deflation 01/02/2024 • Mises Daily • Ludwig von Mises [Excerpted from Chapter 17 of Human Action.] The services money renders are conditioned by the height of its purchasing power. Nobody wants to have in his cash holding a definite number of pieces of...

Auburn: Mises Institute, 2006

The Mises Institute is a non-profit organization that exists to promote teaching and research in the Austrian School of economics, individual freedom, honest history, and international peace, in the tradition of Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard.

Non-political, non-partisan, and non-PC, we advocate a radical shift in the intellectual climate, away from statism and toward a private property order. We believe that our foundational ideas are of permanent value, and oppose all efforts at compromise, sellout, and amalgamation of these ideas with fashionable political, cultural, and social doctrines inimical to their spirit.

Essay · Financial crises

The slumps that shaped modern finance

Finance is not merely prone to crises, it is shaped by them. Five historical crises show how aspects of today’s financial system originated—and offer lessons for today’s regulators

What is mankind’s greatest invention? Ask people this question and they are likely to pick familiar technologies such as printing or electricity. They are unlikely to suggest an innovation that is just as significant: the financial contract. Widely disliked and often considered grubby, it has nonetheless played an indispensable role in human development for at least 7,000 years.

At its core, finance does just two simple things. It can act as an economic time machine, helping savers transport today’s surplus income into the future, or giving borrowers access to future earnings now. It can also act as a safety net, insuring against floods, fires or illness. By providing these two kinds of service, a well-tuned financial system smooths away life’s sharpest ups and downs, making an uncertain world more predictable. In addition, as investors seek out people and companies with the best ideas, finance acts as an engine of growth.

Yet finance can also terrorise. When bubbles burst and markets crash, plans paved years into the future can be destroyed. As the impact of the crisis of 2008 subsides, leaving its legacy of unemployment and debt, it is worth asking if the right things are being done to support what is good about finance, and to remove what is poisonous.

History is a good place to look for answers. Five devastating slumps—starting with America’s first crash, in 1792, and ending with the world’s biggest, in 1929—highlight two big trends in financial evolution. The first is that institutions that enhance people’s economic lives, such as central banks, deposit insurance and stock exchanges, are not the products of careful design in calm times, but are cobbled together at the bottom of financial cliffs. Often what starts out as a post-crisis sticking plaster becomes a permanent feature of the system. If history is any guide, decisions taken now will reverberate for decades.

This makes the second trend more troubling. The response to a crisis follows a familiar pattern. It starts with blame. New parts of the financial system are vilified: a new type of bank, investor or asset is identified as the culprit and is then banned or regulated out of existence. It ends by entrenching public backing for private markets: other parts of finance deemed essential are given more state support. It is an approach that seems sensible and reassuring.

Advertisement

But it is corrosive. Walter Bagehot, editor of this newspaper between 1860 and 1877, argued that financial panics occur when the “blind capital” of the public floods into unwise speculative investments. Yet well-intentioned reforms have made this problem worse. The sight of Britons stuffing Icelandic banks with sterling, safe in the knowledge that £35,000 of deposits were insured by the state, would have made Bagehot nervous. The fact that professional investors can lean on the state would have made him angry.

These five crises reveal where the titans of modern finance—the New York Stock Exchange, the Federal Reserve, Britain’s giant banks—come from. But they also highlight the way in which successive reforms have tended to insulate investors from risk, and thus offer lessons to regulators in the current post-crisis era.

1792: The foundations of modern finance

If one man deserves credit for both the brilliance and the horrors of modern finance it is Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary of the United States. In financial terms the young country was a blank canvas: in 1790, just 14 years after the Declaration of Independence, it had five banks and few insurers. Hamilton wanted a state-of-the-art financial set-up, like that of Britain or Holland. That meant a federal debt that would pull together individual states’ IOUs. America’s new bonds would be traded in open markets, allowing the government to borrow cheaply. And America would also need a central bank, the First Bank of the United States (BUS), which would be publicly owned.

This new bank was an exciting investment opportunity. Of the $10m in BUS shares, $8m were made available to the public. The initial auction, in July 1791, went well and was oversubscribed within an hour. This was great news for Hamilton, because the two pillars of his system—the bank and the debt—had been designed to support each other. To get hold of a $400 BUS share, investors had to buy a $25 share certificate or “scrip”, and pay three-quarters of the remainder not in cash, but with federal bonds. The plan therefore stoked demand for government debt, while also furnishing the bank with a healthy wedge of safe assets. It was seen as a great deal: scrip prices shot up from $25 to reach more than $300 in August 1791. The bank opened that December.

Two things put Hamilton’s plan at risk. The first was an old friend gone bad, William Duer. The scheming old Etonian was the first Englishman to be blamed for an American financial crisis, but would not be the last. Duer and his accomplices knew that investors needed federal bonds to pay for their BUS shares, so they tried to corner the market. To fund this scheme Duer borrowed from wealthy friends and, by issuing personal IOUs, from the public. He also embezzled from companies he ran.

The other problem was the bank itself. On the day it opened it dwarfed the nation’s other lenders. Already massive, it then ballooned, making almost $2.7m in new loans in its first two months. Awash with credit, the residents of Philadelphia and New York were gripped by speculative fever. Markets for short sales and futures contracts sprang up. As many as 20 carriages a week raced between the two cities to exploit opportunities for arbitrage.

The jitters began in March 1792. The BUS began to run low on the hard currency that backed its paper notes. It cut the supply of credit almost as quickly as it had expanded it, with loans down by 25% between the end of January and March. As credit tightened, Duer and his cabal, who often took on new debts in order to repay old ones, started to feel the pinch.

Rumours of Duer’s troubles, combined with the tightening of credit by the BUS, sent America’s markets into sharp descent. Prices of government debt, BUS shares and the stocks of the handful of other traded companies plunged by almost 25% in two weeks. By March 23rd Duer was in prison. But that did not stop the contagion, and firms started to fail. As the pain spread, so did the anger. A mob of angry investors pounded the New York jail where Duer was being held with stones.

Hamilton knew what was at stake. A student of financial history, he was aware that France’s crash in 1720 had hobbled its financial system for years. And he knew Thomas Jefferson was waiting in the wings to dismantle all he had built. His response, as described in a 2007 paper by Richard Sylla of New York University, was America’s first bank bail-out. Hamilton attacked on many fronts: he used public money to buy federal bonds and pep up their prices, helping protect the bank and speculators who had bought at inflated prices. He funnelled cash to troubled lenders. And he ensured that banks with collateral could borrow as much as they wanted, at a penalty rate of 7% (then the usury ceiling).

Even as the medicine was taking effect, arguments about how to prevent future slumps had started. Everyone agreed that finance had become too frothy. Seeking to protect naive amateurs from risky investments, lawmakers sought outright bans, with rules passed in New York in April 1792 outlawing public futures trading. In response to this aggressive regulation a group of 24 traders met on Wall Street—under a Buttonwood tree, the story goes—to set up their own private trading club. That group was the precursor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Hamilton’s bail-out worked brilliantly. With confidence restored, finance flowered. Within half a century New York was a financial superpower: the number of banks and markets shot up, as did GDP. But the rescue had done something else too. By bailing out the banking system, Hamilton had set a precedent. Subsequent crises caused the financial system to become steadily more reliant on state support.

1825: The first emerging-markets crisis

Crises always start with a new hope. In the 1820s the excitement was over the newly independent Latin American countries that had broken free from Spain. Investors were especially keen in Britain, which was booming at the time, with exports a particular strength. Wales was a source of raw materials, cutting 3m tonnes of coal a year, and sending pig iron across the globe. Manchester was becoming the world’s first industrial city, refining raw inputs into higher-value wares like chemicals and machinery. Industrial production grew by 34% between 1820 and 1825.

As a result, cash-rich Britons wanted somewhere to invest their funds. Government bonds were in plentiful supply given the recent Napoleonic wars, but with hostilities over (and risks lower) the exchequer was able to reduce its rates. The 5% return paid on government debt in 1822 had fallen to 3.3% by 1824. With inflation at around 1% between 1820 and 1825 gilts offered only a modest return in real terms. They were safe but boring.

Luckily investors had a host of exotic new options. By the 1820s London had displaced Amsterdam as Europe’s main financial hub, quickly becoming the place where foreign governments sought funds. The rise of the new global bond market was incredibly rapid. In 1820 there was just one foreign bond on the London market; by 1826 there were 23. Debt issued by Russia, Prussia and Denmark paid well and was snapped up.

But the really exciting investments were those in the new world. The crumbling Spanish empire had left former colonies free to set up as independent nations. Between 1822 and 1825 Colombia, Chile, Peru, Mexico and Guatemala successfully sold bonds worth £21m ($2.8 billion in today’s prices) in London. And there were other ways to cash in: the shares of British mining firms planning to explore the new world were popular. The share price of one of them, Anglo Mexican, went from £33 to £158 in a month.

The big problem with all this was simple: distance. To get to South America and back in six months was good going, so deals were struck on the basis of information that was scratchy at best. The starkest example were the “Poyais” bonds sold by Gregor MacGregor on behalf of a new country that did not, in fact, exist. This shocking fraud was symptomatic of a deeper rot. Investors were not carrying out proper checks. Much of the information about new countries came from journalists paid to promote them. More discerning savers would have asked tougher questions: Mexico and Colombia were indeed real countries, but had only rudimentary tax systems, so they stood little chance of raising the money to make the interest payments on their new debt.

Investors were also making outlandish assumptions. Everyone knew that rivalry with Spain meant that Britain’s government supported Latin American independence. But the money men took another step. Because Madrid’s enemy was London’s friend, they reasoned, the new countries would surely be able to lean on Britain for financial backing. With that backstop in place the Mexican and Colombian bonds, which paid 6%, seemed little more risky than 3% British gilts. Deciding which to buy was simple.

But there would be no British support for these new countries. In the summer of 1823 it became clear that Spain was on the verge of default. As anxiety spread, bond prices started to plummet. Research by Marc Flandreau of the Geneva Graduate Institute and Juan Flores of the University of Geneva shows that by the end of 1825 Peru’s bonds had fallen to 40% of their face value, with others following them down.

Britain’s banks, exposed to the debt and to mining firms, were hit hard. Depositors began to scramble for cash: by December 1825 there were bank runs. The Bank of England jumped to provide funds both to crumbling lenders and directly to firms in a bail-out that Bagehot later regarded as the model for crisis-mode central banking. Despite this many banks were unable to meet depositors’ demands. In 1826 more than 10% of the banks in England and Wales failed. Britain’s response to the crash would change the shape of banking.

The most remarkable thing about the crisis of 1825 was the sharp divergence in views on what should be done about it. Some blamed investors’ sloppiness: they had invested in unknown countries’ debt, or in mining outfits set up to explore countries that contained no ores. A natural reaction to this emerging-markets crisis might have been to demand that investors conduct proper checks before putting money at risk.

But Britain’s financial chiefs, including the Bank of England, blamed the banks instead. Small private partnerships akin to modern private-equity houses, they were accused of stoking up the speculative bubble with lax lending. Banking laws at the time specified that a maximum of six partners could supply the equity, which ensured that banks were numerous but small. Had they only been bigger, it was argued, they would have had sufficient heft to have survived the inevitable bust.

Mulling over what to do, the committees of Westminster and Threadneedle Street looked north, to Scotland. Its banks were “joint stock” lenders that could have as many partners as they wanted, issuing equity to whoever would buy it. The Scottish lenders had fared much better in the crisis. Parliament passed a new banking act copying this set-up in 1826. England was already the global hub for bonds. With ownership restrictions lifted, banks like National Provincial, now part of RBS, started gobbling up rivals, a process that has continued ever since.

The shift to joint-stock banking is a bittersweet moment in British financial history. It had big upsides: the ancestors of the modern megabank had been born, and Britain became a world leader in banking as well as bonds. But the long chain of mergers it triggered explains why RBS ended up becoming the world’s largest bank—and, in 2009, the largest one to fail. Today Britain’s big four banks hold around 75% of the country’s deposits, and the failure of any one of them would still pose a systemic risk to the economy.

1857: Panics go global

By the mid-19th century the world was getting used to financial crises. Britain seemed to operate on a one-crash-per-decade rule: the crisis of 1825-26 was followed by panics in 1837 and 1847. To those aware of the pattern, the crash of 1857 seemed like more of the same. But this time things were different. A shock in America’s Midwest tore across the country and jumped from New York to Liverpool and Glasgow, and then London. From there it led to crashes in Paris, Hamburg, Copenhagen and Vienna. Financial collapses were not merely regular—now they were global, too.

On the surface, Britain was doing well in the 1850s. Exports to the rest of the world were booming, and resources increased with gold discoveries in Australia. But beneath the surface two big changes were taking place. Together they would create what this newspaper, writing in 1857, called “a crisis more severe and more extensive than any which had preceded it”.

The first big change was that a web of new economic links had formed. In part, they were down to trade. By 1857 America was running a $25m current-account deficit, with Britain and its colonies as its major trading partners. Americans bought more goods than they sold, with Britain buying American assets to provide the funds, just as China does today. By the mid-1850s Britain held an estimated $80m in American stocks and bonds.

Railway companies were a popular investment. Shares of American railway firms such as the Illinois Central and the Philadelphia and Reading were so widely held by British investors that Britons sat on their boards. That their earnings did not justify their valuations did not matter much: they were a bet on future growth.

The second big change was a burst of financial innovation. As Britain’s aggressive joint-stock banks gobbled up rivals, deposits grew by almost 400% between 1847 and 1857. And a new type of lender—the discount house—was mushrooming in London. These outfits started out as middlemen, matching investors with firms that needed cash. But as finance flowered the discount houses morphed, taking in investors’ cash with the promise that it could be withdrawn at will, and hunting for firms to lend to. In short, they were banks in all but name.

Competition was fierce. Because joint-stock banks paid depositors the Bank of England’s rate less one percentage point, any discount house paying less than this would fail to attract funds. But because the central bank was also an active lender, discounting the best bills, its rate put a cap on what the discount houses could charge borrowers. With just one percentage point to play with, the discount houses had to be lean. Since cash paid zero interest, they cut their reserves close to zero, relying on the fact that they could always borrow from the Bank of England if they faced large depositor withdrawals. Perennially facing the squeeze, London’s new financiers trimmed away their capital buffers.

Meanwhile in America, Edward Ludlow, the manager of Ohio Life, an insurance company, became caught up in railway fever. New lines were being built to link eastern cities with new frontier towns. Many invested heavily but Ludlow went all in, betting $3m of Ohio Life’s $4.8m on railway companies. One investment alone, in the Cleveland and Pittsburgh line, accounted for a quarter of the insurer’s capital.

In late spring 1857, railroad stocks began to drop. Ohio Life, highly leveraged and overexposed, fell faster, failing on August 24th. As research by Charles Calomiris of Columbia University and Larry Schweikart of Dayton University shows, problems spread eastwards, dragging down stockbrokers that had invested in railways. When banks dumped their stock, prices fell further, magnifying losses. By October 13th Wall Street was packed with depositors demanding their money. The banks refused to convert deposits into currency. America’s financial system had failed.

As the financial dominoes continued to topple, the first British cities to suffer were Glasgow and Liverpool. Merchants who traded with American firms began to fail in October. There were direct financial links, too. Dennistoun, Cross and Co., an American bank that had branches in Liverpool, Glasgow, New York and New Orleans, collapsed on November 7th, taking with it the Western Bank of Scotland. That made the British crisis systemic: the bank had 98 branches and held £5m in deposits. There was “wild panic” with troops needed to calm the crowds.

The discount houses magnified the problem. They had become a vital source of credit for firms. But investors were suspicious of their balance-sheets. They were right to be: one reported £10,000 of capital supporting risky loans of £900,000, a leverage ratio that beats even modern excesses. As the discount houses failed, so did ordinary firms. In the last three months of 1857 there were 135 bankruptcies, wiping out investor capital of £42m. Britain’s far-reaching economic and financial tentacles meant this caused panics across Europe.

As well as being global, the crash of 1857 marked another first: the recognition that financial safety nets can create excessive risk-taking. The discount houses had acted in a risky way, holding few liquid assets and small capital buffers in part because they knew they could always borrow from the Bank of England. Unhappy with this, the Bank changed its policies in 1858. Discount houses could no longer borrow on a whim. They would have to self-insure, keeping their own cash reserves, rather than relying on the central bank as a backstop. That step made the 1857 crisis an all-too-rare example of the state attempting to dial back its support. It also shows how unpopular cutting subsidies can be.

The Bank of England was seen to be “obsessed” by the way discount houses relied on it, and to have rushed into its reforms. The Economist thought its tougher lending policy unprincipled: we argued that decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis, rather than applying blanket bans. Others thought the central bank lacked credibility, as it would never allow a big discount house to fail. They were wrong. In 1866 Overend & Gurney, by then a huge lender, needed emergency cash. The Bank of England refused to rescue it, wiping out its shareholders. Britain then enjoyed 50 years of financial calm, a fact that some historians reckon was due to the prudence of a banking sector stripped of moral hazard.

1907: Emergency money

As the 20th century dawned America and Britain had very different approaches to banking. The Bank of England was all-powerful, a tough overseer of a banking system it had helped design. America was the polar opposite. Hamilton’s BUS had closed in 1811 and its replacement, just around the corner in Philadelphia, was shut down in 1836. An atomised, decentralised system developed. Americans thought banks could look after themselves—until the crisis of 1907.

The absence of a lender of last resort had certainly not crimped the expansion of banking. The period after the civil war saw an explosion in the number of banks. By 1907 America had 22,000 banks—one for every 4,000 people. In most towns, there was a choice of local banks or state-owned lenders.

Despite all these options, savvy metropolitan investors tended to go elsewhere—to the trust companies. These outfits appeared in the early 1890s to act as “trustees”, holding their customers’ investments in bonds and stocks. By 1907 they were combining this safehouse role with riskier activities: underwriting and distributing shares, and owning and managing property and railways. They also took in deposits. The trust companies had, in short, become banks.

And they were booming. Compared with ordinary banks, they invested in spicier assets and were more lightly regulated. Whereas banks had to hold 25% of their assets as cash (in case of sudden depositor demands) the trusts faced a 5% minimum. Able to pay higher rates of interest to depositors, they became a favourite place to park large sums. By 1907 they were almost as big as the national banks, having grown by nearly 250% in ten years.

America was buzzing too. Between 1896 and 1906 its average annual growth rate was almost 5%. This was extraordinary, given that America faced catastrophes such as the Baltimore fire of 1904 and San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which alone wiped out around 2% of GDP. All Americans, you might think, would have been grateful that things stayed on track.

But two greedy scammers—Augustus Heinze and Charles Morse—wanted more, as a 1990 paper by Federal Reserve economists Ellis Tallman and Jon Moen shows. The two bankers had borrowed and embezzled vast sums in an attempt to corner the market in the shares of United Copper. But the economy started to slow a little in 1907, depressing the prices of raw materials, including metals. United Copper’s shares fell in response. With the prices of their stocks falling Heinze and Morse faced losses magnified by their huge leverage. To prop up the market, they began to tap funds from the banks they ran. This whipped up trouble for a host of smaller lenders, sparking a chain of losses that eventually embroiled a trust company, the Knickerbocker Trust.

A Manhattan favourite located on the corner of 34th Street and 5th Avenue, its deposits had soared from $10m in 1897 to over $60m in 1907, making it the third-largest trust in America. Its Corinthian columns stood out even alongside its neighbour, the Waldorf Astoria. The exterior marble was from Vermont; the interior marble was from Norway. It was a picture of wealth and solidity.

Yet on the morning of October 22nd the Knickerbocker might as well have been a tin shack. When news emerged that it was caught up in the Heinze-Morse financial contagion, depositors lined the street demanding cash. The Knickerbocker paid out $8m in less than a day, but had to refuse some demands, casting a pall over other trusts. The Trust Company of America was the next to suffer a depositor run, followed by the Lincoln Trust. Some New Yorkers moved cash from one trust to another as they toppled. When it became clear that the financial system was unsafe, Americans began to hoard cash at home.

For a while it looked as though the crisis could be nipped in the bud. After all, the economic slowdown had been small, with GDP still growing by 1.9% in 1907. And although there were crooks like Heinze and Morse causing trouble, titans like John Pierpont Morgan sat on the other side of the ledger. As the panic spread and interest rates spiked to 125%, Morgan stepped in, organising pools of cash to help ease the strain. At one point he locked the entire New York banking community in his library until a $25m bail-out fund had been agreed.

But it was not enough. Depositors across the country began runs on their banks. Sensing imminent collapse, states declared emergency holidays. Those that remained open limited withdrawals. Despite the robust economy, the crash in New York led to a nationwide shortage of money. This hit business hard, with national output dropping a staggering 11% between 1907 and 1908.

With legal tender so scarce alternatives quickly sprang up. In close to half of America’s large towns and cities, cash substitutes started to circulate. These included cheques and small-denomination IOUs written by banks. The total value of this private-sector emergency cash—all of it illegal—was around $500m, far bigger than the Morgan bail-out. It did the trick, and by 1909 the American economy was growing again.

The earliest proposals for reform followed naturally from the cash shortage. A plan for $500m of official emergency money was quickly put together. But the emergency-money plan had a much longer-lasting impact. The new currency laws included a clause to set up a committee—the National Monetary Commission—that would discuss the way America’s money worked. The NMC sat for four years, examining evidence from around the world on how best to reshape the system. It concluded that a proper lender of last resort was needed. The result was the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, which established America’s third central bank in December that year. Hamilton had belatedly got his way after all.

1929-33: The big one

Until the eve of the 1929 slump—the worst America has ever faced—things were rosy. Cars and construction thrived in the roaring 1920s, and solid jobs in both industries helped lift wages and consumption. Ford was making 9,000 of its Model T cars a day, and spending on new-build homes hit $5 billion in 1925. There were bumps along the way (1923 and 1926 saw slowdowns) but momentum was strong.

Banks looked good, too. By 1929 the combined balance-sheets of America’s 25,000 lenders stood at $60 billion. The assets they held seemed prudent: just 60% were loans, with 15% held as cash. Even the 20% made up by investment securities seemed sensible: the lion’s share of holdings were bonds, with ultra-safe government bonds making up more than half. With assets of such high quality the banks allowed the capital buffers that protected them from losses to dwindle.

But as the 1920s wore on the young Federal Reserve faced a conundrum: share prices and prices in the shops started to move in opposite directions. Markets were booming, with the shares of firms exploiting new technologies—radios, aluminium and aeroplanes—particularly popular. But few of these new outfits had any record of dividend payments, and investors piled into their shares in the hope that they would continue to increase in value. At the same time established businesses were looking weaker as consumer prices fell. For a time the puzzle—whether to raise rates to slow markets, or cut them to help the economy—paralysed the Fed. In the end the market-watchers won and the central bank raised rates in 1928.

It was a catastrophic error. The increase, from 3.5% to 5%, was too small to blunt the market rally: share prices soared until September 1929, with the Dow Jones index hitting a high of 381. But it hurt America’s flagging industries. By late summer industrial production was falling at an annualised rate of 45%. Adding to the domestic woes came bad news from abroad. In September the London Stock Exchange crashed when Clarence Hatry, a fraudulent financier, was arrested. A sell-off was coming. It was huge: over just two days, October 28th and 29th, the Dow lost close to 25%. By November 13th it was at 198, down 45% in two months.

Worse was to come. Bank failures came in waves. The first, in 1930, began with bank runs in agricultural states such as Arkansas, Illinois and Missouri. A total of 1,350 banks failed that year. Then a second wave hit Chicago, Cleveland and Philadelphia in April 1931. External pressure worsened the domestic worries. As Britain dumped the Gold Standard its exchange rate dropped, putting pressure on American exporters. There were banking panics in Austria and Germany. As public confidence evaporated, Americans again began to hoard currency. A bond-buying campaign by the Federal Reserve brought only temporary respite, because the surviving banks were in such bad shape.

This became clear in February 1933. A final panic, this time national, began to force more emergency bank holidays, with lenders in Nevada, Iowa, Louisiana and Michigan the first to shut their doors. The inland banks called in inter-bank deposits placed with New York lenders, stripping them of $760m in February 1933 alone. Naturally the city bankers turned to their new backstop, the Federal Reserve. But the unthinkable happened. On March 4th the central bank did exactly what it had been set up to prevent. It refused to lend and shut its doors. In its mission to act as a source of funds in all emergencies, the Federal Reserve had failed. A week-long bank holiday was called across the nation.

It was the blackest week in the darkest period of American finance. Regulators examined banks’ books, and more than 2,000 banks that closed that week never opened again. After this low, things started to improve. Nearly 11,000 banks had failed between 1929 and 1933, and the money supply dropped by over 30%. Unemployment, just 3.2% on the eve of the crisis, rose to more than 25%; it would not return to its previous lows until the early 1940s. It took more than 25 years for the Dow to reclaim its peak in 1929.

Reform was clearly needed. The first step was to de-risk the system. In the short term this was done through a massive injection of publicly supplied capital. The $1 billion boost—a third of the system’s existing equity—went to more than 6,000 of the remaining 14,000 banks. Future risks were to be neutralised by new legislation, the Glass-Steagall rules that separated stockmarket operations from more mundane lending and gave the Fed new powers to regulate banks whose customers used credit for investment.

A new government body was set up to deal with bank runs once and for all: the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC), established on January 1st 1934. By protecting $2,500 of deposits per customer it aimed to reduce the costs of bank failure. Limiting depositor losses would protect income, the money supply and buying power. And because depositors could trust the FDIC, they would not queue up at banks at the slightest financial wobble.

In a way, it worked brilliantly. Banks quickly started advertising the fact that they were FDIC insured, and customers came to see deposits as risk-free. For 70 years, bank runs became a thing of the past. Banks were able to reduce costly liquidity and equity buffers, which fell year on year. An inefficient system of self-insurance fell away, replaced by low-cost risk-sharing, with central banks and deposit insurance as the backstop.

Yet this was not at all what Hamilton had hoped for. He wanted a financial system that made government more stable, and banks and markets that supported public debt to allow infrastructure and military spending at low rates of interest. By 1934 the opposite system had been created: it was now the state’s job to ensure that the financial system was stable, rather than vice versa. By loading risk onto the taxpayer, the evolution of finance had created a distorting subsidy at the heart of capitalism.

The recent fate of the largest banks in America and Britain shows the true cost of these subsidies. In 2008 Citigroup and RBS Group were enormous, with combined assets of nearly $6 trillion, greater than the combined GDP of the world’s 150 smallest countries. Their capital buffers were tiny. When they ran out of capital, the bail-out ran to over $100 billion. The overall cost of the banking crisis is even greater—in the form of slower growth, higher debt and poorer employment prospects that may last decades in some countries.

But the bail-outs were not a mistake: letting banks of this size fail would have been even more costly. The problem is not what the state does, but that its hand is forced. Knowing that governments must bail out banks means parts of finance have become a one-way bet. Banks’ debt is a prime example. The IMF recently estimated that the world’s largest banks benefited from implicit government subsidies worth a total of $630 billion in the year 2011-12. This makes debt cheap, and promotes leverage. In America, meanwhile, there are proposals for the government to act as a backstop for the mortgage market, covering 90% of losses in a crisis. Again, this pins risk on the public purse. It is the same old pattern.

To solve this problem means putting risk back into the private sector. That will require tough choices. Removing the subsidies banks enjoy will make their debt more expensive, meaning equity holders will lose out on dividends and the cost of credit could rise. Cutting excessive deposit insurance means credulous investors who put their nest-eggs into dodgy banks could see big losses.

As regulators implement a new round of reforms in the wake of the latest crisis, they have an opportunity to reverse the trend towards ever-greater entrenchment of the state’s role in finance. But weaning the industry off government support will not be easy. As the stories of these crises show, hundreds of years of financial history have been pushing in the other direction.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

How the 2008 financial crisis crashed the economy and changed the world.

Paul Solman Paul Solman

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-the-2008-financial-crisis-crashed-the-economy-and-changed-the-world

Ten years ago this week, the collapse of Lehman Brothers became the signal event of the 2008 financial crisis. Its effects and the recession that followed, on income, wealth, disparity and politics are still with us. Economics correspondent Paul Solman walks through those events and consequences with historian Adam Tooze, author of "Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World."

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

It was one of the most profound events in generations, with huge consequences for on the American economy and households throughout the country.

This was the time a decade ago when the financial crisis erupted, a crash that most experts didn't foresee.

Its effects, and of the recession that followed, on income, wealth inequality, and our politics are still with us.

Tonight, our economics correspondent, Paul Solman, revisits how it all went down, and the impact today of decisions made then.

It's part of our weekly series, Making Sense.

Paul Solman:

So, this is where, in some sense, the crisis began.

Adam Tooze:

Yes, this was the place where people were stumbling out of offices on the 15th of September, 2008, the world having ended.

The midtown Manhattan headquarters of Lehman Brothers, whose collapse 10 years ago this week was the signal event of the 2008 financial crisis.

It started in real estate, and it started with subprime, and that's the story everyone knows. How does that crisis in the suburbs of America move all the way back to the center of finance in New York?

OK. How does it?

Banks are fragile things. Classically, we think of them as being funded by deposits, with households putting their savings into the bank, and then the householders begin to get panicked and take all their money out.

But, says economist and historian Adam Tooze, author of the new book "Crashed".

Banks like Lehman don't have deposits. What they do is borrow money from other banks, and that money runs faster than any depositor can run.

So subprime mortgages begin to default. Lots of people are invested in those mortgages. Banks have a big stake. And so suddenly, when banks look vulnerable, then they don't lend to each other anymore, investors pull back. That's what happened?

Yes, that's the crucial thing. Afterwards, there was a congressional inquiry that went after the banks for selling the bad securities to investors who ended up being ripped off. That wasn't in fact the dangerous bit. The real problem were the bad debts, the securities that America's banks kept on their balance sheets.

In other word, Lehman not only created debt securities, bonds, backed by iffy subprime mortgages. It held on to them. When the debts started going bad, faith in Lehman collapsed.

No faith, no credit. No credit, no Lehman.

We came as close as we have ever come in history to a total cardiac arrest, not just of the American economy, but the entire world economy.

Meaning everybody is afraid to lend to everybody else. Credit simply freezes, and an economy, a modern economy can't function that way?

A modern economy can't function without credit for more than even a couple of hours, frankly, seconds. G.E., the pillar of American manufacturing, was having a hard time getting short-term credit. So was Harvard University. Wage bills were not being paid.

And soon enough, the whole world was watching, and enmeshed.

To illustrate your point about how the crisis spread globally, I thought we'd go to a Greek food stand. But you said, no, no, an Irish pub. And, lo and behold, there's one right across the street from the old Lehman.

Yes, because 2008 is all about banks. And the failure of the Irish banks in September 2008 is really the moment when the panic spreads to Europe in a way that the European states ultimately find almost impossible to handle.

Because European banks have a stake in Irish banks?

All of Europe is tied up with the Irish banking boom, as using Dublin as an offshore financial center. And Dublin finds itself in a position on the 29th of September of having to guarantee the entire balance sheet of the Irish banking system.

Back in the U.S. of A., September 29 was also the day Congress rejected President Bush's bailout bill.

The motion is not adopted.

And the Dow fell a record 777 points.

This is where the crisis goes from being a banking crisis to a crisis of the American economy as a whole, with stock market values crashing in September 2008.

We were now in the belly of the beast.

So, here we have Wall Street with all the global banks, and then over here, the New York Stock Exchange.

Which is where we are now.

And the heart of the crisis-fighting effort, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Ground zero 9/29, the New York Fed. Here is where the system was saved.

And what the New York Fed decided to do, what the United States Federal Reserve system decided to do was play the classic role it's always intended to play, to be the lender of last resort to American financial institutions.

Yes. There's a lot of emphasis, for obvious reasons, on the unconventional side of Fed policy in '08, the bailouts, taking equity stakes in banks or quantitative easing.

But what really made the difference in the survival of the American and the global banking system in September 2008 was indeed liquidity provision, to take an asset which is very unattractive to sell in the moment of the crisis because its value may be suspect.

Assets like loans backed by failing mortgages, which the Fed took off the hands of the banks.

And to give you in exchange a cash loan that will tide you over for a matter of days, weeks or months.

Ready cash. liquidity.

And this saved the American financial system?

This didn't just save the American financial system. It saved the financial system of the world. More than half of the liquidity provision to large banks in the United States was to European banks in the United States, and then on top of that, the Fed lent $4.5 trillion to European and Asian central banks, who indirectly provided dollars to their local banks in Europe and in Japan.

And this, says Adam Tooze, is the key to understanding the crash of '08, a global financial crisis because of global financial interconnectedness, a crisis that would have been far worse had the U.S. not dispensed dollars worldwide.

Wall Street is a global banking center. So you have banks from all over the world. And the Fed is providing them liquidity not out of the goodness of its heart, but to stabilize the American financial system, to stabilize the American housing market.

And to stabilize the intricately interconnected global financial system, with players like Barclays of London, which bought the remains of Lehman.

Yes, Barclays got hundreds of billions in liquidity too.

So, in the end, the system worked, right? I mean, we're on Wall Street, stock market almost double what it was before the crash.

Well, it did, if you happened to be one of the minority of Americans who actually has stock. Most Americans don't. And large parts of America have not recovered from the crisis.

The San Francisco Fed was estimating that, as a result of the lost growth in the U.S. economy, the decade in which America grew below where it might otherwise have been, the recession probably cost the average American about $70,000.

Seventy thousand dollars in lifetime income, that is.

So that is not something we're ever going to get back, regardless of what happens in the stock market.

Which prompted a final question, about the political ramifications of the crash of '08, at a final location.

This is Zuccotti Park, just by Wall Street, the site of the famous encampment in 2011 that spawned Occupy and the discourse of the 1 percent against the 99 percent, the place where inequality in America today was really put back on the political map.

Huge rage against bailing out the banks. And the other great political reaction to the crisis came two years earlier in the form of the Tea Party, the idea that irresponsible borrowers who had taken on debts they couldn't afford were now going to be rescued by the federal government.

One opens, if you like, the door to a more radical politics on the right. The other opens the door to a more radical politics on the left.

Which is, of course, just where we are on the 10th anniversary of the crash of '08.

For the "PBS NewsHour," this is economics correspondent Paul Solman, reporting from New York.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

Paul Solman has been a correspondent for the PBS News Hour since 1985, mainly covering business and economics.

Support Provided By: Learn more

More Ways to Watch

Educate your inbox.

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

The Global Financial Crisis has been a watershed event not only for many advanced economies but also emerging markets around the world. This book brings together research and policy work over the last nine years from staff at the IMF. It covers a wide range of issues such as the origins of the financial crisis, the policy response, spillovers and contagion, case studies, bank stress testing, and debt sustainability and sovereign debt restructuring.

International Monetary Fund Copyright © 2010-2021. All Rights Reserved.

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

Chapter 1. The economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic sent shock waves through the world economy and triggered the largest global economic crisis in more than a century. The crisis led to a dramatic increase in inequality within and across countries. Preliminary evidence suggests that the recovery from the crisis will be as uneven as its initial economic impacts, with emerging economies and economically disadvantaged groups needing much more time to recover pandemic-induced losses of income and livelihoods . 1

In contrast to many earlier crises, the onset of the pandemic was met with a large, decisive economic policy response that was generally successful in mitigating its worst human costs in the short run. However, the emergency response also created new risks—such as dramatically increased levels of private and public debt in the world economy—that may threaten an equitable recovery from the crisis if they are not addressed decisively.

Worsening inequality within and across countries

The economic impacts of the pandemic were especially severe in emerging economies where income losses caused by the pandemic revealed and worsened some preexisting economic fragilities. As the pandemic unfolded in 2020, it became clear that many households and firms were ill-prepared to withstand an income shock of that scale and duration. Studies based on precrisis data suggest, for example, that more than 50 percent of households in emerging and advanced economies were not able to sustain basic consumption for more than three months in the event of income losses . 2 Similarly, the average business could cover fewer than 55 days of expenses with cash reserves . 3 Many households and firms in emerging economies were already burdened with unsustainable debt levels prior to the crisis and struggled to service this debt once the pandemic and associated public health measures led to a sharp decline in income and business revenue.

The crisis had a dramatic impact on global poverty and inequality. Global poverty increased for the first time in a generation, and disproportionate income losses among disadvantaged populations led to a dramatic rise in inequality within and across countries. According to survey data, in 2020 temporary unemployment was higher in 70 percent of all countries for workers who had completed only a primary education. 4 Income losses were also larger among youth, women, the self-employed, and casual workers with lower levels of formal education . 5 Women, in particular, were affected by income and employment losses because they were likelier to be employed in sectors more affected by lockdown and social distancing measures . 6

Similar patterns emerge among businesses. Smaller firms, informal businesses, and enterprises with limited access to formal credit were hit more severely by income losses stemming from the pandemic. Larger firms entered the crisis with the ability to cover expenses for up to 65 days, compared with 59 days for medium-size firms and 53 and 50 days for small and microenterprises, respectively. Moreover, micro-, small, and medium enterprises are overrepresented in the sectors most severely affected by the crisis, such as accommodation and food services, retail, and personal services.

The short-term government responses to the crisis

The short-term government responses to the pandemic were extraordinarily swift and encompassing. Governments embraced many policy tools that were either entirely unprecedented or had never been used on this scale in emerging economies. Examples are large direct income support measures, debt moratoria, and asset purchase programs by central banks. These programs varied widely in size and scope (figure 1.1), in part because many low-income countries were struggling to mobilize resources given limited access to credit markets and high precrisis levels of government debt. As a result, the size of the fiscal response to the crisis as a share of the gross domestic product (GDP) was almost uniformly large in high-income countries and uniformly small or nonexistent in low-income countries. In middle-income countries, the fiscal response varied substantially, reflecting marked differences in the ability and willingness of governments to spend on support programs.

Figure 1.1 Fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis, selected countries, by income group

: WDR 2022 team, based on IMF (2021). Data from International Monetary Fund, “Fiscal Monitor Update,” . : The figure reports, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), the total fiscal support, calculated as the sum of “above-the-line measures” that affect government revenue and expenditures and the subtotal of liquidity support measures. Data are as of September 27, 2021. |

Similarly, the combination of policies chosen to confront the short-term impacts differed significantly across countries, depending on the availability of resources and the specific nature of risks the countries faced (figure 1.2). In addition to direct income support programs, governments and central banks made unprecedented use of policies intended to provide temporary debt relief, including debt moratoria for households and businesses. Although these programs mitigated the short-term liquidity problems faced by households and businesses, they also had the unintended consequence of obscuring the true financial condition of borrowers, thereby creating a new problem: lack of transparency about the true extent of credit risk in the economy.

Figure 1.2 Fiscal, monetary, and financial sector policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis, by country income group

: WDR 2022 team, based on Erik H. B. Feyen, Tatiana Alonso Gispert, Tatsiana Kliatskova, and Davide S. Mare, “Taking Stock of the Financial Sector Policy Response to COVID-19 around the World,” Policy Research Working Paper 9497, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2020; Eric Lacey, Joseph Massad, and Robert Utz, “A Review of Fiscal Policy Responses to COVID-19,” Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment Insight 7, Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions Insight Series, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2021; World Bank, COVID-19 Crisis Response Survey, 2021, . : The figure shows the percentage of countries in which each of the listed policies was implemented in response to the pandemic. Data for the financial sector measures are as of June 30, 2021. |

The large crisis response, while necessary and effective in mitigating the worst impacts of the crisis, led to a global increase in government debt that gave rise to renewed concerns about debt sustainability and added to the widening disparity between emerging and advanced economies. In 2020, 51 countries—including 44 emerging economies—experienced a downgrade in their government debt risk rating (that is, the assessment of a country’s creditworthiness) . 7

Emerging threats to an equitable recovery

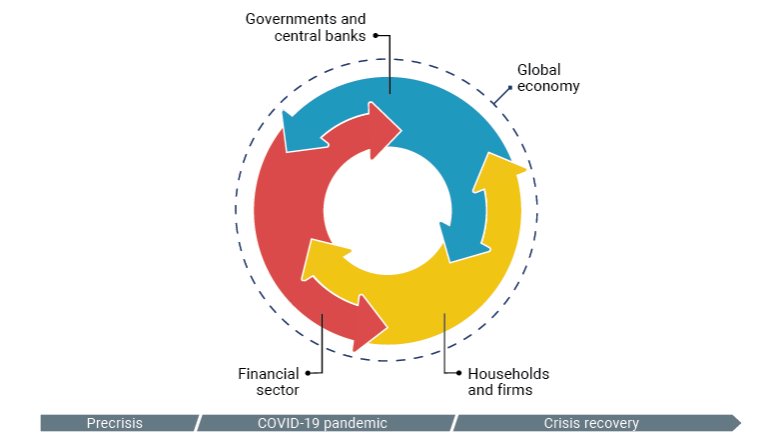

Although households and businesses have been most directly affected by income losses stemming from the pandemic, the resulting financial risks have repercussions for the wider economy through mutually reinforcing channels that connect the financial health of households, firms, financial institutions, and governments (figure 1.3). Because of this interconnection, elevated financial risk in one sector can spill over and destabilize the economy as a whole. For example, if households and firms are under financial stress, the financial sector faces a higher risk of loan defaults and is less able to provide credit. Similarly, if the financial position of the public sector deteriorates (for example, as a result of higher government debt and lower tax revenue), the ability of the public sector to support the rest of the economy is weakened.

Figure 1.3 Conceptual framework: Interconnected balance sheet risks

WDR 2022 team. The figure shows the links between the main sectors of an economy through which risks in one sector can affect the wider economy. |

This relationship is, however, not predetermined. Well-designed fiscal, monetary, and financial sector policies can counteract and reduce these intertwined risks and can help transform the links between sectors of the economy from a vicious doom loop into a virtuous cycle.

One example of policies that can make a critical difference are those targeting the links between the financial health of households, businesses, and the financial sector. In response to the first lockdowns and mobility restrictions, for example, many governments supported households and businesses using cash transfers and financial policy tools such as debt moratoria. These programs provided much-needed support to households and small businesses and helped avert a wave of insolvencies that could have threatened the stability of the financial sector.

Similarly, governments, central banks, and regulators used various policy tools to assist financial institutions and prevent risks from spilling over from the financial sector to other parts of the economy. Central banks lowered interest rates and eased liquidity conditions, making it easier for commercial banks and nonbank financial institutions such as microfinance lenders to refinance themselves, thereby allowing them to continue to supply credit to households and businesses.

The crisis response will also need to include policies that address the risks arising from high levels of government debt to ensure that governments preserve their ability to effectively support the recovery. This is an important policy priority because high levels of government debt reduce the government’s ability to invest in social safety nets that can counteract the impact of the crisis on poverty and inequality and provide support to households and firms in the event of setbacks during the recovery.

By 2021, after the collapse in per capita incomes across the globe in 2020, 40 percent of advanced economies had recovered and, in some cases, exceeded their 2019 output levels. The comparable share of countries achieving per capita income in 2021 that surpassed 2019 output is far lower among middle-income countries, at 27 percent, and lower still among low-income countries, at only 21 percent. Cristian Badarinza, Vimal Balasubramaniam, and Tarun Ramadorai, “The Household Finance Landscape in Emerging Economies,” 11 (December 2019): 109–29, . Data from World Bank, COVID-19 Business Pulse Surveys Dashboard, . The difference in the rate of work stoppage between less well-educated and more well-educated workers was statistically significant in 23 percent of the countries. See Maurice Kugler, Mariana Viollaz, Daniel Vasconcellos Archer Duque, Isis Gaddis, David Locke Newhouse, Amparo Palacios-López, and Michael Weber, “How Did the COVID-19 Crisis Affect Different Types of Workers in the Developing World?” Policy Research Working Paper 9703, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2021, . Tom Bundervoet, María Eugenia Dávalos, and Natalia Garcia, “The Short-Term Impacts of COVID-19 on Households in Developing Countries: An Overview Based on a Harmonized Data Set of High-Frequency Surveys,” Policy Research Working Paper 9582, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2021, . Markus P. Goldstein, Paula Lorena Gonzalez Martinez, Sreelakshmi Papineni, and Joshua Wimpey, “The Global State of Small Business during COVID-19: Gender Inequalities,” (blog), September 8, 2020, . Carmen M. Reinhart, “From Health Crisis to Financial Distress,” Policy Research Working Paper 9616, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2021, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35411. Data from Trading Economics, Credit Rating (database), . |

➜ Read the Full Chapter (.pdf) : English ➜ Read the Full Report (.pdf) : English ➜ WDR 2022 Home

CHAPTER SUMMARIES

➜ Chapter 1 ➜ Chapter 2 ➜ Chapter 3 ➜ Chapter 4 ➜ Chapter 5 ➜ Chapter 6

RELATED LINKS

➜ Blog Posts ➜ Press and Media ➜ Consultations ➜ WDR 2022 Core Team

WDR 2022 Video | Michael Schlein: President & CEO of Accion

Wdr 2022 video | chatib basri: former minister of finance of indonesia.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Geography & Travel

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Introduction

Causes of the crisis

- Key events of the crisis

- Effects and aftermath of the crisis

financial crisis of 2007–08

financial crisis of 2007–08 , severe contraction of liquidity in global financial markets that originated in the United States as a result of the collapse of the U.S. housing market . It threatened to destroy the international financial system; caused the failure (or near-failure) of several major investment and commercial banks , mortgage lenders, insurance companies, and savings and loan associations ; and precipitated the Great Recession (2007–09), the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression (1929– c. 1939).

Although the exact causes of the financial crisis are a matter of dispute among economists, there is general agreement regarding the factors that played a role (experts disagree about their relative importance).

First, the Federal Reserve (Fed), the central bank of the United States, having anticipated a mild recession that began in 2001, reduced the federal funds rate (the interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds—i.e., balances held at a Federal Reserve bank) 11 times between May 2000 and December 2001, from 6.5 percent to 1.75 percent. That significant decrease enabled banks to extend consumer credit at a lower prime rate (the interest rate that banks charge to their “prime,” or low-risk, customers, generally three percentage points above the federal funds rate) and encouraged them to lend even to “subprime,” or high-risk, customers, though at higher interest rates ( see subprime lending ). Consumers took advantage of the cheap credit to purchase durable goods such as appliances, automobiles, and especially houses. The result was the creation in the late 1990s of a “housing bubble” (a rapid increase in home prices to levels well beyond their fundamental, or intrinsic, value, driven by excessive speculation).

Second, owing to changes in banking laws beginning in the 1980s, banks were able to offer to subprime customers mortgage loans that were structured with balloon payments (unusually large payments that are due at or near the end of a loan period) or adjustable interest rates (rates that remain fixed at relatively low levels for an initial period and float, generally with the federal funds rate, thereafter). As long as home prices continued to increase, subprime borrowers could protect themselves against high mortgage payments by refinancing, borrowing against the increased value of their homes, or selling their homes at a profit and paying off their mortgages. In the case of default, banks could repossess the property and sell it for more than the amount of the original loan. Subprime lending thus represented a lucrative investment for many banks. Accordingly, many banks aggressively marketed subprime loans to customers with poor credit or few assets, knowing that those borrowers could not afford to repay the loans and often misleading them about the risks involved. As a result, the share of subprime mortgages among all home loans increased from about 2.5 percent to nearly 15 percent per year from the late 1990s to 2004–07.

Third, contributing to the growth of subprime lending was the widespread practice of securitization , whereby banks bundled together hundreds or even thousands of subprime mortgages and other, less-risky forms of consumer debt and sold them (or pieces of them) in capital markets as securities (bonds) to other banks and investors, including hedge funds and pension funds. Bonds consisting primarily of mortgages became known as mortgage-backed securities , or MBSs, which entitled their purchasers to a share of the interest and principal payments on the underlying loans. Selling subprime mortgages as MBSs was considered a good way for banks to increase their liquidity and reduce their exposure to risky loans, while purchasing MBSs was viewed as a good way for banks and investors to diversify their portfolios and earn money. As home prices continued their meteoric rise through the early 2000s, MBSs became widely popular, and their prices in capital markets increased accordingly.

Fourth, in 1999 the Depression-era Glass-Steagall Act (1933) was partially repealed, allowing banks, securities firms, and insurance companies to enter each other’s markets and to merge, resulting in the formation of banks that were “too big to fail” (i.e., so big that their failure would threaten to undermine the entire financial system). In addition, in 2004 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) weakened the net-capital requirement (the ratio of capital, or assets, to debt, or liabilities, that banks are required to maintain as a safeguard against insolvency), which encouraged banks to invest even more money into MBSs. Although the SEC’s decision resulted in enormous profits for banks, it also exposed their portfolios to significant risk, because the asset value of MBSs was implicitly premised on the continuation of the housing bubble.

Fifth, and finally, the long period of global economic stability and growth that immediately preceded the crisis, beginning in the mid- to late 1980s and since known as the “Great Moderation,” had convinced many U.S. banking executives, government officials, and economists that extreme economic volatility was a thing of the past. That confident attitude—together with an ideological climate emphasizing deregulation and the ability of financial firms to police themselves—led almost all of them to ignore or discount clear signs of an impending crisis and, in the case of bankers, to continue reckless lending, borrowing, and securitization practices.

The Global Economic Crisis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

I could never have thought that the world’s economy could be brought down on its knees in such a short while if you would have asked me before the economic crisis hit. Yet again, it’s not like there was a war looming in the air to contribute to this or anything. My view is that the great depression of the 1930s could be excused because the globe was just coming to form the repercussions of the First World War, and again the Second World War was just lingering in the air.

Many parties are to blame for the global economic crisis. These range from the economists with their low forecasts to central banks with poor policies through regulatory institutions that could not develop proper frameworks to govern the innovations in the financial markets. Financial institutions are also to blame for entering into hapless deals that almost brought the global economy tumbling in doom.

Blame time is over, and the blame game is not equally going to take the global economy to higher heights. Lessons and a myriad of them, for that matter, have been drawn to our attention as individuals, governments, institutions, and businesses. However, these lessons can only be beneficial when a proper review of the leading causes, effects, and effectiveness of the remedies is evaluated. My honest opinion would then be that teams of professionals be set up to look at all these items and then come up with policies that will be able to maneuver around such challenges in the future.

I have personally been able to make several inferences from the causes of the effects and the strategies that governments tried to apply to alleviate the situation. My approach to personal finances, business approach, and home establishments has been renewed. For example, at my privately owned equity firm where I work, I realized that the types of assets held by an organization are fundamental. I would not have made this statement this authoritatively had the financial crisis not occurred. Financial institutions lost a great deal as relates to toxic assets and bad loans. In as much as a business and as an individual, I do have assets; I believe the levels of asset volatility need to be weighed first. In as much as toxic assets need to form the asset structure, they should be held in moderation.

Being in a buy out firm in France, I noted with keen interest that speculators were venturing into buyouts at this particular time. This was the case because some investors could not foresee that this crunch was going to last long. This speculation made persons buy firms at an overvalued price only to realize that the crisis was ongoing and were making losses. From this, I believed that during such swings in the economic cycle, getting into buy out was tantamount to gambling. Further, organizations venturing into the buyout would end up in worse situations since they would have to offset the debt they had incurred before launching the buyout. Secondly, they would have to bear the losses that the firms that they were acquiring were making.

This also applies to real-life scenarios in my life. As a person, I have come to realize that I should not make snap decisions, especially when conditions are so volatile. There are moments when I am faced with challenges, and I have to come up with solutions. Say when I have argued with a close friend and I need to decide on the direction of our friendship, I have learned that emotions or short term excitements are not meant to inform the kind of decisions that I am to take in life. Integrity, to me, is core. I hold on to it so dearly. However, the global economic crisis occurrences just worked to open my eyes to how much our society currently lacks integrity. Talk of the banks that would offer loans at adjustable interest rates, which is not brought to the full attention of the customers who ended up suffering in the long run. This has worked to change my perception of banks and other financial institutions. My dealings with them are now with much more caution.

Another aspect of my perception that has been influenced is that investments that people make in the company stocks are beneficial but face much more vulnerabilities than when persons invest in government bonds and bills. This thought has been influenced because the wealth levels of individuals met a nose dive as the S&P 500 was down by 45% in early November of 2008 from the high experienced in 2007. I there tend to be more risk-averse in my dealings and trades more than a risk-taker. In a nutshell, my risk attitudes have since changed. As I trade currencies, for example, I would love to use small margins and small lot sizes so that if I was to incur a loss, then it is totally minimized. This means that the profits that I take in these trades are also little. However, this does not mean that as a person, I am not rational so as to prefer small to more. On the contrary, I am very reasonable, but I would love to consider caution in my rationality.

Basing on the movement of savings and investments droning the onset of the economic crisis, I have determined that persons need to indulge in proper budgetary allocations. This will involve persons setting aside funds for investments, savings, and consumption. This setting aside of funds, as I later came to realize, should be well determined by taking into account the inflationary tendencies and price level changes. This is because savings and investments were also falling drastically at the onset of the credit crunch. The fed reserve has experienced a shift in role from the lender of last resort to be the lender of only resort. The downfall of the S&P 500 influenced my perception of equity sources of finance. To some point, I have come to believe that debt capital should be considered just as equally as equity is.

The way warning signs should be treated in organizations, for me, was much influenced by the happenings of the global economic crisis. I have come to form the opinion that however baseless allegations in an institution seem to be, consideration for them should be given. This is because effects at first were sidelined with governments and ministers of finance while political leaders were working to alleviate fears of the magnitude of the ramifications to be expected. In as much as some sideshows in an organization may serve to waste organization time, I am now of the opinion that firms need to set up ad hoc committees that will spare some time to handle any issues coming up in the organization; however small they may appear. With the effects of this economic crisis, other countries could not get an opportunity to sell their consumer products. The previous perception I had was that the trickle-down result of a financial mishap could not affect other countries as gravely as it did affect countries like Cambodia. This has made me view partners and other stakeholders carefully in terms of what happens in their realm and the possible ramifications in the whole industry that as a business I operate in.

The unemployment that followed the global economic crisis kept me thinking of ways that firms may engage in so as to limit the cases of unemployment. I was an ardent supporter of job specialization and the benefits thereof. I have to mention now that I consider that to be a cause of unemployment at times. My view is that once one joins a firm, there needs to be continuous training and job rotation so that in cases when some units or departments have to be closed, still the employees will have something to do other than remaining redundant. Further, I have come to realize that sustainable employment is essential in an organization. My thinking has been changed from job specialization to job diversification. As an organization, we should be in a position to employ multi-skilled workers and reduce job losses that are created by economic downturns.

The world was caught off guard by the global economic crisis. Leaders and policymakers had to keep shoving in the dark, trying to find solutions; some of them ended up deepening the already gross state of the economies. This got me thinking; what if, as a business, we did simulate possible grave positions and the solutions that would relate to them? Won’t that make it much more straightforward when faced with such challenges? For me, the answers to the two questions were yes and yes. The government of the US came in to bail out the central banks. As a business, my thought was if there was going to be another institution that would bail us out if we went crumbling. This placed an idea of having to diversify investments in various places and industries so that one sector would help should the other in times of financial crises.