- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

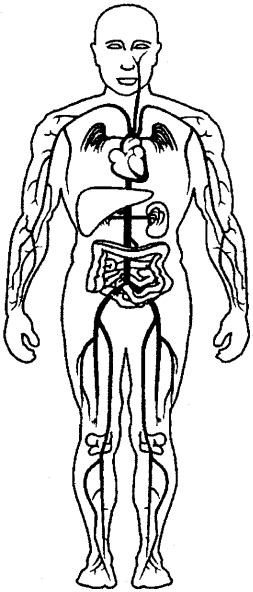

Chemical composition of the body

Organization of the body.

- Basic form and development

- Effects of aging

- Change incident to environmental factors

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Biology LibreTexts - Introduction to the Human Body

- Healthline - The Human Body

- National Institutes of Health - National Cancer Institute - Introduction to the Human Body

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Thoughts on the Human Body

- MSD Manual - Consumer Version - The Human Body

- LiveScience - The Human Body: Anatomy, Facts and Functions

- human body - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- human body - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

What is the chemical composition of the human body?

Chemically, the human body consists mainly of water and organic compounds—i.e., lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. The human body is about 60 percent water by weight.

What are the four main types of tissue in the human body?

The four main types of tissue in the human body are epithelial , muscle , nerve , and connective .

What are the nine major organ systems in the human body?

The nine major organ systems in the human body are the integumentary system, the musculoskeletal system, the respiratory system, the circulatory system, the digestive system, the excretory system, the nervous system, the endocrine system, and the reproductive system.

Recent News

human body , the physical substance of the human organism, composed of living cells and extracellular materials and organized into tissues , organs , and systems.

Human anatomy and physiology are treated in many different articles. For detailed discussions of specific tissues, organs, and systems, see human blood ; cardiovascular system ; human digestive system ; human endocrine system ; renal system ; skin ; human muscle system ; nervous system ; human reproductive system ; human respiration ; human sensory reception ; and human skeletal system . For a description of how the body develops, from conception through old age , see aging ; growth ; prenatal development ; and human development .

For detailed coverage of the body’s biochemical constituents , see protein ; carbohydrate ; lipid ; nucleic acid ; vitamin ; and hormone . For information on the structure and function of the cells that constitute the body, see cell .

Many entries describe the body’s major structures. For example, see abdominal cavity ; adrenal gland ; aorta ; bone ; brain ; ear ; eye ; heart ; kidney ; large intestine ; lung ; nose ; ovary ; pancreas ; pituitary gland ; small intestine ; spinal cord ; spleen ; stomach ; testis ; thymus ; thyroid gland ; tooth ; uterus ; and vertebral column .

Humans are, of course, animals —more particularly, members of the order Primates in the subphylum Vertebrata of the phylum Chordata. Like all chordates , the human animal has a bilaterally symmetrical body that is characterized at some point during its development by a dorsal supporting rod (the notochord ), gill slits in the region of the pharynx , and a hollow dorsal nerve cord. Of these features, the first two are present only during the embryonic stage in the human; the notochord is replaced by the vertebral column, and the pharyngeal gill slits are lost completely. The dorsal nerve cord is the spinal cord in humans; it remains throughout life.

Characteristic of the vertebrate form, the human body has an internal skeleton that includes a backbone of vertebrae. Typical of mammalian structure, the human body shows such characteristics as hair , mammary glands , and highly developed sense organs.

Beyond these similarities, however, lie some profound differences. Among the mammals , only humans have a predominantly two-legged ( bipedal ) posture, a fact that has greatly modified the general mammalian body plan. (Even the kangaroo , which hops on two legs when moving rapidly, walks on four legs and uses its tail as a “third leg” when standing.) Moreover, the human brain, particularly the neocortex, is far and away the most highly developed in the animal kingdom. As intelligent as are many other mammals—such as chimpanzees and dolphins —none have achieved the intellectual status of the human species.

Chemically, the human body consists mainly of water and of organic compounds —i.e., lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. Water is found in the extracellular fluids of the body (the blood plasma , the lymph , and the interstitial fluid) and within the cells themselves. It serves as a solvent without which the chemistry of life could not take place. The human body is about 60 percent water by weight.

Lipids —chiefly fats , phospholipids , and steroids —are major structural components of the human body. Fats provide an energy reserve for the body, and fat pads also serve as insulation and shock absorbers. Phospholipids and the steroid compound cholesterol are major components of the membrane that surrounds each cell.

Proteins also serve as a major structural component of the body. Like lipids, proteins are an important constituent of the cell membrane . In addition, such extracellular materials as hair and nails are composed of protein. So also is collagen , the fibrous, elastic material that makes up much of the body’s skin, bones, tendons, and ligaments. Proteins also perform numerous functional roles in the body. Particularly important are cellular proteins called enzymes , which catalyze the chemical reactions necessary for life.

Carbohydrates are present in the human body largely as fuels, either as simple sugars circulating through the bloodstream or as glycogen , a storage compound found in the liver and the muscles. Small amounts of carbohydrates also occur in cell membranes, but, in contrast to plants and many invertebrate animals, humans have little structural carbohydrate in their bodies.

Nucleic acids make up the genetic materials of the body. Deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA ) carries the body’s hereditary master code, the instructions according to which each cell operates. It is DNA, passed from parents to offspring, that dictates the inherited characteristics of each individual human. Ribonucleic acid ( RNA ), of which there are several types, helps carry out the instructions encoded in the DNA.

Along with water and organic compounds , the body’s constituents include various inorganic minerals. Chief among these are calcium , phosphorus , sodium , magnesium , and iron . Calcium and phosphorus, combined as calcium-phosphate crystals, form a large part of the body’s bones. Calcium is also present as ions in the blood and interstitial fluid , as is sodium. Ions of phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium, on the other hand , are abundant within the intercellular fluid. All of these ions play vital roles in the body’s metabolic processes. Iron is present mainly as part of hemoglobin , the oxygen-carrying pigment of the red blood cells . Other mineral constituents of the body, found in minute but necessary concentrations, include cobalt , copper , iodine , manganese , and zinc .

The cell is the basic living unit of the human body—indeed, of all organisms. The human body consists of trillions of cells, each capable of growth, metabolism , response to stimuli , and, with some exceptions, reproduction. Although there are some 200 different types of cells in the body, these can be grouped into four basic classes. These four basic cell types, together with their extracellular materials, form the fundamental tissues of the human body:

- epithelial tissues, which cover the body’s surface and line the internal organs, body cavities, and passageways

- muscle tissues, which are capable of contraction and form the body’s musculature

- nerve tissues, which conduct electrical impulses and make up the nervous system

- connective tissues , which are composed of widely spaced cells and large amounts of intercellular matrix and which bind together various body structures

Bone and blood are considered specialized connective tissues, in which the intercellular matrix is, respectively, hard and liquid.

The next level of organization in the body is that of the organ . An organ is a group of tissues that constitutes a distinct structural and functional unit. Thus, the heart is an organ composed of all four tissues, whose function is to pump blood throughout the body. Of course, the heart does not function in isolation; it is part of a system composed of blood and blood vessels as well. The highest level of body organization, then, is that of the organ system.

The body includes nine major organ systems, each composed of various organs and tissues that work together as a functional unit. The chief constituents and prime functions of each system are:

- The integumentary system , composed of the skin and associated structures, protects the body from invasion by harmful microorganisms and chemicals; it also prevents water loss from the body.

- The musculoskeletal system (also referred to separately as the muscle system and the skeletal system ), composed of the skeletal muscles and bones (with about 206 of the latter in adults), moves the body and protectively houses its internal organs.

- The respiratory system , composed of the breathing passages, lungs, and muscles of respiration , obtains from the air the oxygen necessary for cellular metabolism; it also returns to the air the carbon dioxide that forms as a waste product of such metabolism.

- The circulatory system , composed of the heart, blood, and blood vessels, circulates a transport fluid throughout the body, providing the cells with a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients and carrying away waste products such as carbon dioxide and toxic nitrogen compounds.

- The digestive system , composed of the mouth, esophagus , stomach, and intestines, breaks down food into usable substances (nutrients), which are then absorbed from the blood or lymph; this system also eliminates the unusable or excess portion of the food as fecal matter.

- The excretory system , composed of the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder , and urethra , removes toxic nitrogen compounds and other wastes from the blood.

- The nervous system , composed of the sensory organs, brain, spinal cord, and nerves, transmits, integrates , and analyzes sensory information and carries impulses to effect the appropriate muscular or glandular responses.

- The endocrine system , composed of the hormone -secreting glands and tissues, provides a chemical communications network for coordinating various body processes.

- The reproductive system , composed of the male or female sex organs, enables reproduction and thereby ensures the continuation of the species.

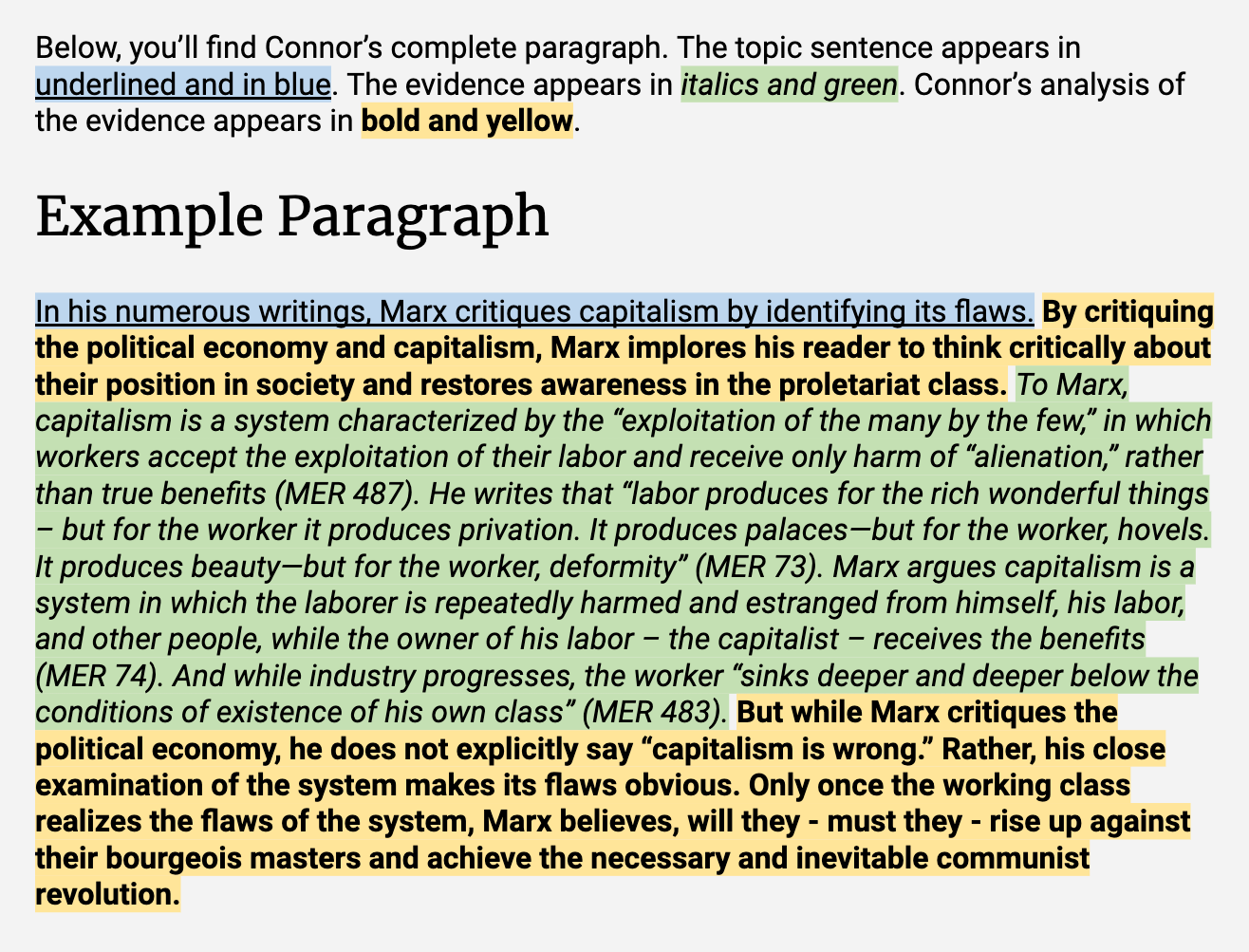

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

Human Body Essay

Introduction.

It is surprising to see how a human body functions with maximum capability. Whether we are talking, walking or seeing, there are distinct parts in our body that are destined to perform a particular function. The importance of each part is discussed in this human body essay. When we feel tired, we often take a rest and lie down for a moment. But our body continues to work, even when we take a break. Even if you are tired, your heart will not stop beating. It pumps blood and transports nutrients to your body.

The human body is made up of many parts and organs that work together to sustain life in our body. No organ or body part is more important than the other, and if you ignore one of them, then the whole body will be in pain. So, let us teach the significance of different parts of the body to our children through this essay on human body parts in English. To explore other exciting content for kids learning , head to our website.

Different Systems in the Human Body

The human body looks very simple from the outside with hands, legs, face, eyes, ears and so on. But, there is a more complex and significant structure inside the body that helps us to live. The human body is made up of many small structures like cells, tissues, organs and systems. It is covered by the skin, beneath which you could find muscles, veins, and blood. This structure is formed on the base of a skeleton, which consists of many bones. All these are arranged in a specific way to help the body function effectively. In this human body essay, we will see the different systems in the human body and their functions.

The circulatory system, respiratory system, digestive system and nervous system are the main systems of the human body. Each system has different organs, and they function together to accomplish several tasks. The circulatory system consists of organs like the heart, blood and blood vessels, and its main function is to pump blood from the heart to the lungs and carry oxygen to different parts of the body.

Next, we will understand the importance of the respiratory system through this human body essay in English. The respiratory system enables us to breathe easily, and it includes organs like the lungs, airways, windpipe, nose and mouth. While the digestive system helps in breaking down the food we eat and gives the energy to work with the help of organs like the mouth, food pipe, stomach, intestines, pancreas, liver, and anus, the nervous system controls our actions, thoughts and movements. It mainly consists of organs like the brain, spinal cord and nerves.

All these systems are necessary for the proper functioning of the human body, which is discussed in this essay on human body parts in English. By inculcating good eating habits, maintaining proper hygiene and doing regular exercises, we can look after our bodies. You can refer to more essays for kids on our website.

Frequently Asked Questions on Human Body Essay

Why should we take care of our bodies.

Most of the tasks we do like walking, running, eating etc., are only possible if we have a healthy body. To ensure we have a healthy body, all the systems must function properly, which is determined by our lifestyle and eating habits. Only a healthy body will have a healthy mind, and hence, we must take good care of our bodies.

What are some of the body parts and their functions?

We see with our eyes, listen with our ears, walk with our legs, touch with our hands, breathe through our nose and taste with our tongue.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Essay on My Body

Students are often asked to write an essay on My Body in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on My Body

Introduction.

My body is a complex system that allows me to live, learn, and grow. It is made up of many different parts, all working together to keep me healthy.

Parts of My Body

The main parts of my body are the head, trunk, and limbs. My head houses my brain, eyes, and mouth. The trunk includes my chest and abdomen, containing vital organs. My limbs help me move around.

Importance of My Body

My body is important because it helps me interact with the world. It allows me to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell. It’s also my responsibility to keep it healthy.

Understanding my body helps me appreciate how amazing it is. It’s a wonderful system that deserves care and respect.

250 Words Essay on My Body

The human body, a complex and intricate system, is the physical manifestation of our existence. It’s a marvel of biological engineering, housing billions of cells working in perfect harmony to ensure our survival and well-being.

The Body as a Biological Masterpiece

Our bodies are a collection of systems, each playing a vital role. The circulatory system, for instance, ensures oxygen and nutrients reach every cell. The nervous system, a network of nerves and neurons, serves as our communication hub, while the immune system protects us from foreign invaders.

Body and Mind Connection

The body is not just a physical entity but also an extension of our mind. The mind-body connection is a profound concept, where emotions and thoughts can influence our physical health. Stress, for instance, can trigger physical symptoms like headaches or stomach issues.

Body Autonomy and Respect

Body autonomy, the right to control one’s body, is a fundamental human right. It’s essential to respect our bodies, acknowledging their capabilities and limitations. This includes maintaining a healthy lifestyle and making informed choices about our bodies.

In conclusion, our bodies are more than just physical structures. They are a testament to nature’s ingenuity, a bridge connecting us to our minds, and a personal domain demanding respect and care. Recognizing this multifaceted nature of our bodies can help us better appreciate and take care of them.

500 Words Essay on My Body

Introduction: the marvel of the human body, the body as a system of systems.

The body is made up of multiple systems, each with a specific role. The nervous system acts as the body’s command center, sending and receiving signals to and from different parts of the body. The circulatory system, with the heart as its key player, ensures the efficient distribution of oxygen and nutrients throughout the body. The respiratory system, comprising the lungs, takes in oxygen and expels carbon dioxide, a waste product of metabolism. The digestive system breaks down food into simpler substances that the body can use for energy, growth, and cell repair. The skeletal and muscular systems provide structure and mobility, while the endocrine system regulates the body’s metabolism and energy levels.

Cells: The Building Blocks of the Body

At the microscopic level, the body is composed of trillions of cells, each performing specific functions. Cells are the basic building blocks of life, and their collective action ensures the smooth functioning of the body. They are responsible for everything from absorbing nutrients and producing energy to fighting off infections and healing wounds.

The Body’s Adaptability and Resilience

The importance of taking care of our body.

Our body is our most precious asset, and it is essential to take care of it. A healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet, regular exercise, adequate sleep, and stress management, can enhance the body’s functioning and longevity. Regular medical check-ups can help detect potential problems early and keep the body in optimal condition.

Conclusion: The Body as a Reflection of Self

In conclusion, the human body is not just a biological entity; it is a reflection of who we are. It embodies our experiences, our actions, and our choices. It is a testament to the miracle of life and the complexity of nature. By understanding and appreciating our body, we can develop a more profound sense of self-awareness and respect for our own existence.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

11 Reasons to Worship Your Body (and His)

- O 's 3-step guide to making peace with your body

- How much time do you waste obsessing about...your thighs, your stomach, your self?

- How men really feel about their bodies

WATCH OWN APP

Download the Watch OWN app and access OWN anytime, anywhere. Watch full episodes and live stream OWN whenever and wherever you want. The Watch OWN app is free and available to you as part of your OWN subscription through a participating TV provider.

NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS TODAY AND ENJOY THE BENEFITS.

- Stay up to date with the latest trends that matter to you most.

- Have top-notch advice and tips delivered directly to you.

- Be in the know on current and upcoming trends.

OPRAH IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF HARPO, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2024 HARPO PRODUCTIONS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. OWN: OPRAH WINFREY NETWORK

The Anatomy of the Human Body Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The Institute of Human Anatomy’s YouTube video, “ The Anatomy of Pain ,” visually explores the structures involved in pain’s transmission and processing. The video was selected because it provides an excellent illustration of the physical basis for pain. The new knowledge acquired is that there are two facets to every person’s experience of pain, and they work together to make the experience unique (“Institute of Human”, 2021). One is a specific, localized feeling in a section of the body, while the other is a more generalized, unpleasant quality of varied intensity that is typically accompanied by actions meant to alleviate or end the experience.

Most directly related to the video was a concept from the unit’s textbook readings on developmental psychology: a complicated matrix of peripheral and visceral neurons, the central nervous system, and the brain serve the perception of pain. While pain is the leading cause of patient visits to the doctor, it defies precise categorization since only the person experiencing it can fully understand and articulate it (Santrock, 2022). Pain is characterized by a combination of a noxious sensory experience and an unpleasant physiochemical and emotional response. Either way, it is meant to alert the person to the impending danger. It is the clinician’s responsibility to both identify and address the origins of the patient’s discomfort.

To explain the link further, various modifying elements within the neural system influence pain transmission. Many factors contribute to pain perception, including chemical modulation, the additive effects of inflammatory byproducts, and the inhibitory impact of large-diameter sensory afferent fibers. Pain is a multifaceted, biopsychosocial experience involving a wide range of neural circuits, neurochemicals, mental operations, and emotional responses (Santrock, 2022). The brain does not only take in pain signals from the body; it actively controls sensory output by descending extensions from the medulla that sway the spinal dorsal horn.

Institute of Human Anatomy. (2021). The anatomy of pain [Video]. YouTube. Web.

Santrock, J. W. (2022). A topical approach to life-span development (11 th ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- How the Respiratory System Works to Adjust Blood pH

- Stress and Its Influence on Human Body

- Nk Cells, Activating and Inhibitory Receptors in Influenza Virus Life Cycle

- Human Anatomy and Physiology

- Inhibitory Influence of Salt on Grass Growth

- Dove Care & Protect Antibacterial Body Wash

- The Urine Volume and Composition Experiment

- The Impact of Caffeine on Athletic Performance

- Stages of Sleep, Brain Waves, and the Neural Mechanisms of Sleep

- Wounds, Their Types and Healing Stages

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 22). The Anatomy of the Human Body. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-anatomy-of-the-human-body/

"The Anatomy of the Human Body." IvyPanda , 22 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-anatomy-of-the-human-body/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Anatomy of the Human Body'. 22 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Anatomy of the Human Body." January 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-anatomy-of-the-human-body/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Anatomy of the Human Body." January 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-anatomy-of-the-human-body/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Anatomy of the Human Body." January 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-anatomy-of-the-human-body/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Human Body Essay | Essay on Human Body in Life for Students and Children in English

February 12, 2024 by sastry

Human Body Essay: Human body is truly a marvel. It is perhaps the most evolved living thing. It is, in fact, like a highly sophisticated machine.

You can read more Essay Writing about articles, events, people, sports, technology many more.

Short Essay on Human Body 200 Words for Kids and Students in English

Below we have given a short essay on Human Body is for Classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. This short essay on the topic is suitable for students of class 6 and below.

To prevent it from diseases and illnesses, a thorough knowledge of the human body is necessary. Medical science has unravelled many mysteries of the functions of our body. And, the more we find out, the more fascinating the human body appears to be. But there is still a lot that we don’t know or can’t explain.

The human skeleton is like a cage. It provides the necessary support to the body. It also helps in protecting our vital organs. There are 206 bones in an adult human body. These bones are made up of calcium and phosphorus. The box-like skull structure protects our brain.

The muscles constitute the flesh. There are over 600 muscles in our body. All our movements are the direct result of the contraction and expansion of these muscles.

A cell is the basic unit of the body and there are millions of cells in each human body. These cells get nourishment through food, drink and oxygen. The cell suffer wear and tear during work. But through adequate rest and food the damage to the cell is repaired.

Then, there are the circulatory, respiratory, disgestive and nervous systems in our body. They are all highly complex systems but each is wonderful in its own way. Human heart and brain must be two of the most wonderful creations ever. They are extremely complicated but also very efficient parts of our body.

For us to live and remain healthy, it is important for all these parts and systems to work well together, in harmony with each other.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

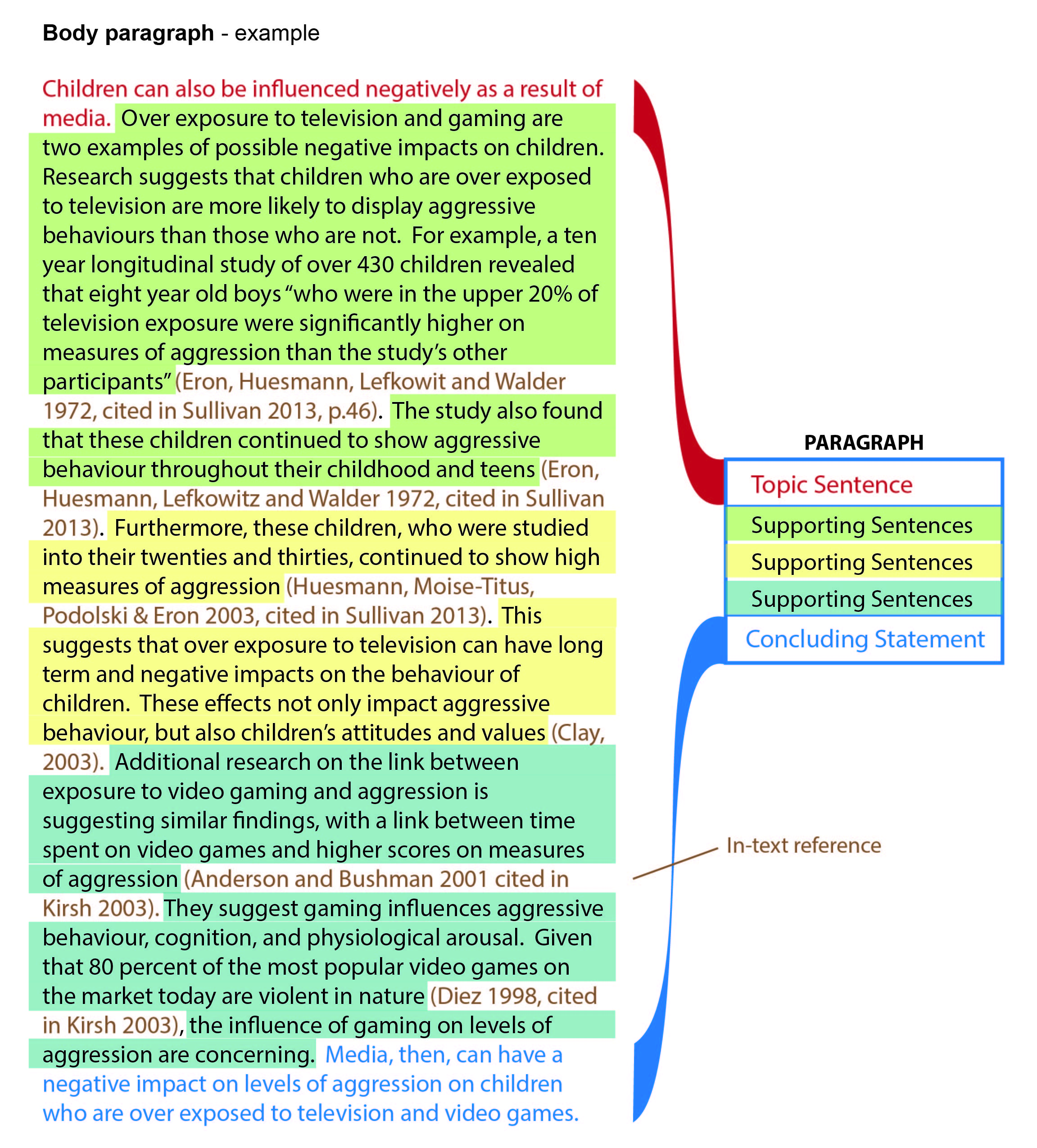

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

'We Sweat, Crave, and Itch All Day': Why Writing About Bodies Is Vital

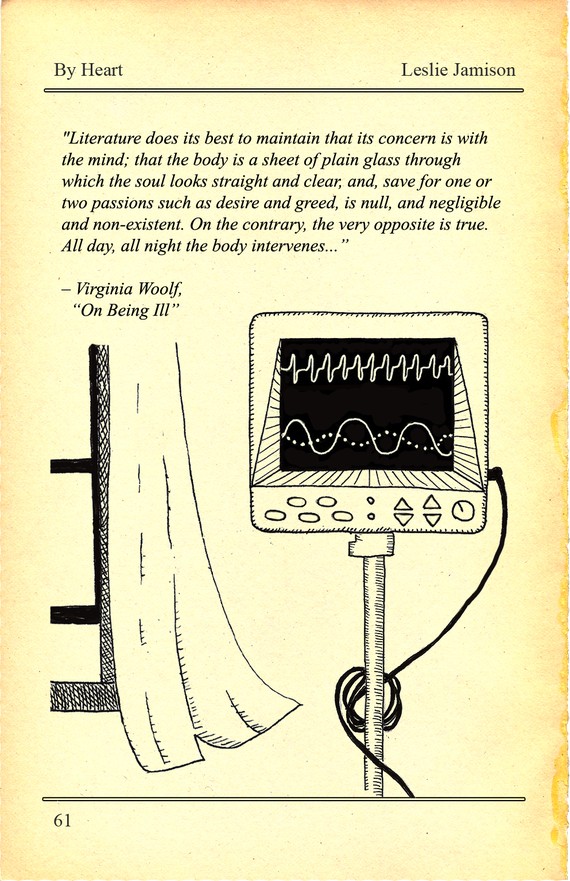

The Empathy Exams author Leslie Jamison felt ashamed of writing about the physical form until a Virginia Woolf essay vindicated her interest in the fluids and muscles that make us human.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Claire Messud, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Virginia Woolf was no stranger to doctors: For much of her life she suffered from fevers, migraines, fainting spells, and the stark depressive episodes for which she’s well-known. In her essay “On Being Ill,” first published in T.S. Eliot’s journal The Criterion in 1926, Woolf taught a lesson learned from a life in sickbeds—that illness is epic, as worthy a topic as love and battle. But while warriors have the Greeks, and lovers have Keats and Shakespeare, she says, the sick lack a great bard. She implores readers to develop a poetic vocabulary for the body out of order, and calls us to pay attention to the ways pathology elevates our senses and enlivens our language.

When she discovered “On Being Ill,” The Empathy Exams author Leslie Jamison found welcome license in Woolf’s directive. In her essay for this series, Jamison explains how she felt pressure to steer clear of physicality in her work—to be ashamed of her fascination with the body and its many states of illness. She recalled how an accident left her physically speechless—a dramatic demonstration of Woolf’s proposition that the sick become mute—and explained why she wants to learn to utter, in her work, the many things a body can endure.

Recommended Reading

Go Ahead and Fail

The Cost of Engaging With the Miserable

Cancel Earthworms

In The Empathy Exams , a nonfiction collection, we see this tendency at work. Jamison’s essays continually seek language to express her body’s history—a broken nose, a broken jaw, a fluky ventricle, a surprise pregnancy—to make her experiences brilliantly visible and thereby understood. But the exploration moves beyond her own wounds towards the suffering of others. In essays about poverty and its tourists, medical actors and career malingerers, wrongfully imprisoned convicts and the prison of the body, Jamison asks urgent questions about the nature of empathy itself: How can we say “I hurt” and be heard? How much of empathy is rooted in selfishness? And how might we, all of us, broaden the capacity of our hearts?

The Empathy Exams is winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize. Jamison’s first book, The Gin Closet , a novel, was finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize . Her essays have appeared in Harper’s , The Believer , Oxford American , and A Public Space. She lives in Brooklyn.

From Virginia Woolf’s “ On Being Ill ” :

“…strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. Novels, one would have thought, would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia; lyrics to toothache. But no, with a few exceptions … literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear, and, save for one or two passions such as desire and greed, is null, and negligible and non-existent. On the contrary, the very opposite is true. All day, all night the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February. The creature within can only gaze through the pane—smudged or rosy; it cannot separate off from the body like the sheath of a knife or the pod of a pea for a single instant; it must go through the whole unending procession of changes, heat and cold, comfort and discomfort, hunger and satisfaction, health and illness, until there comes the inevitable catastrophe; the body smashes itself to smithereens, and the soul (it is said) escapes. But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record.”

Leslie Jamison: “On Being Ill” isn’t just making a case for illness as a literary subject, but for the brute, bare fact of the body itself. By insisting we acknowledge that we sweat and crave and itch all day (“all day, all night”), Woolf reminds us we have the right to speak about these things—to make them lyric and epic—and that we should seek a language that honors them. The man who suffers a migraine, she writes, is “forced to coin words himself, taking his pain in one hand and a lump of pure sound in the other.” What does it sound like, this strange, unholy language of nerves and excretions? How do we articulate the kind of pain that refuses language? We throw up our hands, or we hurl our charts: one through ten, bad to worse, from the smiley face to its wretched, frowning cousin.

Woolf’s argument may have been more urgent in her time than in ours—we have more records of the “daily drama of the body” now than we did then—but when I first read her battle cry, her call to arms (not just arms but legs and teeth and bones), it felt like encountering a long-lost relative: the banner I’d never known I’d always been fighting under: Bodies matter—we can ’ t escape them—they ’ re full of stories—how do we tell them? Her argument might have the urgency of a battle cry but it’s also vulnerable; it’s posing questions; it’s got mess and nerve—it’s leaking some strange fluid from beneath its garments, hard to tell in the twilight, maybe pus or tears or blood. Even her syntax feels bodily—full of curves and joints and twists, shifting and stretching the skin of her sentences.

People have often told me my own writing seems to be all about bodies. A woman from a writing workshop once suggested I call my collection of stories Body Issues. (I didn’t have a collection of stories: If I did, I wouldn’t have called it that.) But I’ve never wanted to write about “the body,” by which I mean I’ve never set out with that explicit intention; I’ve only ever wanted to write about what it feels like to be alive, and it turns out being alive is always about being in a body. We’re never not in bodies: that’s just our fate and our assignment. (In her beautiful memoir The Two Kinds of Decay, Sarah Manguso writes that she despises “the body” whenever it describes anything but a corpse, and I love that, though I use the phrase constantly anyway.) To my mind, the more aggressive choice is writing that isn’t physical; this insistence carries the burden of intentional absence.

All that said, I’ve always felt a certain shame about the ways my writing keeps coming back to bodies, which is why I loved finding Woolf. My shame felt such relief at the prospect of her company. My first novel was all about addiction and eating disorders and sex, and there was food everywhere, some of it gone rotten. I used the word “sweat” too many times (my editor told me); there were too many fluids (my editor told me) and far too many bruises (my editor told me) and even worse, too many of these bruises were “plum-colored”—for this last one (my editor told me), we would both get mocked , if we didn’t get rid of some of these plum-colored bruises right away. A certain shame hung over the whole narrative, like a faint body odor I couldn’t smell because it was mine: There was too much body, and this too-much-body risked banality and melodrama at once. I’ve always wondered if this shame about writing about the body is connected to the shame of quasi-autobiographical writing, that sense of failing to imagine beyond one’s own experience. Is writing about bodily experience somehow the extreme form of this failure, the ultimate solipsism? You haven’t even gotten beyond your own nerve endings; it’s no accident they call it navel gazing.

I often think of an old painting I once saw that shows an injured body pointing at its own open wounds. The most graceful victim, of course, is the one who doesn’t need to point at his holes or ask for sympathy—who doesn’t take up the lump of pure sound, who just keeps quiet. The way I imagine being scolded goes something like this: There’s something selfish about talking about bodies too much if the bodily experience fueling everything is your own.

I often think, also, of a cross-country race I ran in 10th grade: I tripped on a slab of concrete sticking up from the dirt, about a hundred meters after the start, when the pack was still dense; and I was trampled by the horde of 15-year-old girls running behind me. It was pretty minor, as tramplings go. But still, it was a trampling. I got up to run the next three miles of the race but I was shaken up and bleeding. I wasn’t running well at all—nothing close to what I’d need to do to place well for our team.

When I reached my coach, who was calling out our one-mile splits, she said something to the effect of “Why are you running so slow?”—only perhaps not so delicately phrased. I remember the awkward way I tried to point at my own wounds without slowing my (turtle) pace; and I remember how badly I wanted her to see the streaks of dirt-clotted blood; I almost stumbled again in my urgent need to show her the proof of my stumbling.

That memory has become the vessel for a certain kind of shame—the shame of pointing too overtly at what hurts, jamming the laser-pointer of language at some wound and then expecting it to yield wisdom or explanation. My coach didn’t want the epic or lyric account of my damaged body, she just wanted me to keep running , and hopefully pick up the pace.

I’m still haunted by the specter of myself in this moment—a mute form pointing, bleeding. A few years after that race I spent a couple months actually mute: I’d gotten jaw surgery and they’d wired my jaw shut to help it heal. During those months I wrote quite frequently but it was mainly practical, because I couldn’t talk. I requested things by scribbling them in a little notebook: vicodin, please; okay ensure (my mom was always foisting Ensure on me) , but are there any cans of dark chocolate left? HATE butter pecan. I asked for sheets draped over the mirrors, so I wouldn’t see my swollen face; I asked for the pair of scissors that I was supposed to keep on-hand in case I vomited and needed to cut the wires between my teeth.

Eventually I started writing poems about those quiet weeks, and the surgery before them, the days in the hospital. The poems were full of IV lines and numbness and feeling returning after numbness like water oozing back into crab holes in damp sand (“crackling lines of hurt,” I wrote). I imagined myself the bard of swelling; I wanted to write toothache lyrics for swelling—to evoke the chronic panic of its deforming sculptural practice: it shapes you into something like you, but not you. I wanted to bring that aching knowledge to my nonexistent reading public.

I turned the poems into a series and then I turned them in to my undergraduate writing workshop. The series was called “Waiting Room,” meaning the waiting room before surgery but also the injury afterward as a waiting room—get it?—the aftermath as the cramped little chamber where you wait to get better; where you have to keep waiting even once it seems like you should already be there.

I wasn’t satisfied with the poems. Pain was hard to describe. I encountered Elaine Scarry’s famous formulation—“pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it”—which recognized but did not solve the problem. My workshop wasn’t satisfied with the poems either. Everyone wanted to know: What were they about? I thought it was pretty fucking self-evident , but no, it was a different problem: My classmates got that these poems were about pain and injury—maybe in a dental office?—but what were they really about? My workshop was thinking everything must be a metaphor for something else: the cut lines on raw gums, the self-quieting sparkle of anesthesia. But in truth, nothing was a metaphor for anything. It was more or less this happened, and it hurt. There was nothing below the surface.

At the time I took this as a verdict of poverty and lack—which is why I loved finding Woolf, so many years later, who seemed to be saying, the surface of the body isn ’ t poverty; it isn ’t lack. She rose from the dead for the express purpose of silencing that workshop, or at least arguing against the notion that there had to be something besides bodies for these poems to matter. She was saying the surface is poetry; bodies are poetry; or poetry can be made of what these bodies need and crave and bleed and feel.

I felt her summoning an army, everyone I’d ever read whose language does some justice to the way our bodies are , the ways they betray us or bind us together: Walt Whitman’s greed to catalogue the physical forms of his countrymen, William Faulkner’s fixation on muddy drawers and the waft of honeysuckle; Marcel Merleau-Ponty’s insistence on the body as an “eloquent relic of existence.”

Woolf writes: “It is not only a new language that we need, more primitive, more sensual, more obscene, but a new hierarchy of the passions; love must be deposed in favour of a temperature of 104; jealousy give place to the pangs of sciatica.” I can see the way these marching orders have infected my own prose—even this piece, with its twisting, bodily contortions—and the way they’ve helped me claim a dialect I’d been afraid was junk, a ledger of the body’s travails, not the “Waiting Room” poems (which weren’t really that great) but the notebooks I kept when my jaw was wired silent, full of their banal complaints and requests: Vicodin, please. Where are the vomit scissors? These are daily dramas of the body, charged with force and longing; the record Woolf never found, the words that pain and pure sound made.

About the Author

More Stories

The Future of Recycling Is Sorty McSortface

What Stories About Racial Trauma Leave Out

Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — Body Image — The Importance of Body Positivity

The Importance of Body Positivity

- Categories: Body Body Image

About this sample

Words: 669 |

Published: Aug 31, 2023

Words: 669 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2378 words

3 pages / 1439 words

3 pages / 1249 words

2 pages / 963 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Body Image

Ballaro, B., & Wagner, A. (n.d.). Body Image in the Media. In Media and Society (pp. 72-83). Retrieved from [...]

Body image is a complex and multi-faceted concept that encompasses a person's thoughts, feelings, and perceptions about their physical appearance. It is influenced by a variety of factors, including societal standards of beauty, [...]

Physical appearance and personality are two interconnected aspects of an individual's identity, each playing a significant role in shaping how we perceive ourselves and others. While physical appearance is the immediate visual [...]

Mary Maxfield is a renowned author and scholar whose essay "Food as Thought: Resisting the Moralization of Eating" delves into the complex relationship between food, morality, and individual identity. Through her [...]

The body image has passed through history, where it has been concerned with the beauty of the human body. Every change in the society around it, the emergence of the media, the change of culture, and its impact on other cultures [...]

The 1950s were a time of significant change in American society, particularly when it came to body image. This era marked the beginning of the modern obsession with thinness, as the hourglass figure of the 1940s gave way to a [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Center for Literary Publishing

Colorado review, a college of liberal arts center.

Book Reviews

You Feel So Mortal: Essays on the Body

About the book.

- Author: Peggy Shinner

- Reviewed By: Jennifer Wisner Kelly

- Genre: Nonfiction

- Publisher: University of Chicago Press

- Published: 2014

Book Review

Shinner is in her sixties and like so many of us still struggles to be at peace with her body, with all its slouchiness, its “Jewish feet,” its bosom in need of ample support. Yet, she has gained the maturity and wisdom to take pride in her body, too. After all, she couldn’t get around without it. She couldn’t be a martial arts expert without it. She wouldn’t be Peggy Shinner without this particular corporeal form. And in each essay she wittily argues that our bodies forge our identities, with proof from her own experiences and those of the beloved people in her life: her partner, Ann; her clutch of loyal friends; her mother and father, for whom she still mourns decades after their deaths.

Shinner weaves these personal narratives with curious snippets of history on subjects as diverse as the mythology of women’s hair, the 1950s cult of good posture, and the fate of Nathan Leopold of Leopold and Loeb fame. These interludes of historical curiosities are entertaining, but also elevate Shinner’s personal memories to something more universal. Take “Pocketing,” for example, in which Shinner recounts her single experience of shoplifting—a can of nutmeg from a grocery store back in her twenties—in contrast to nineteenth-century notions of women’s psychology. Women, the old theories went, became kleptomaniacs because of troubles with their wombs and their repressed sexuality. And while we are enjoying this romp through an earlier era—those crazy, sexist psychiatrists!—she asks herself whether, in fact, those ignoramuses might have been onto something. Wasn’t it true that when she shoplifted she was in transition, having proclaimed herself a lesbian but not yet having found a partner with whom to consummate this newly declared sexuality? Her voice shines through as she tells us about her theft:

I stole a jar of nutmeg from the Jewel. . . . Where I had gone grocery shopping. Where I had, in fact, filled the cart with my small stash of weekly necessities. I was the occasional baker, and the nutmeg, I dimly reasoned, could be used in zucchini bread. I concealed the jar in my pocket, which no sooner hidden there seemed exposed, and waited in line to pay for the rest of my groceries. . . . It was a down-at-the-heels Jewel in a modest neighborhood. Many of the shoppers were Latino. I was a diffident white woman not likely to catch anyone’s attention. I left the store unnoticed.

Did I steal the nutmeg as a substitute for sex? Was the desire to be transgressive really the desire to fulfill desire? Did I just need a little nookie? Well, I did need a little nookie, there’s no denying that.

In Shinner’s deft hands, the factual bits woven into her essays feel as organic and essential as her personal stories and reflections. Reading her work is, I imagine, akin to sitting next to her at a dinner party: her ideas a sparkling confluence of anecdote, self-analysis and quirky historical facts.

For Shinner, any discussion of the body must also be a discussion of being Jewish, the two being intertwined in her identity. “History has weighed in on my body, and I have come up . . . Jewish.” I confess that as a mutt of nineteenth-century Ellis Island immigration, my body has never been a strong source of ethnic identity. I have never considered whether my too long nose or my stocky legs are particularly Irish or German, whether others might evaluate my body not just based on its beauty or lack thereof, but on its ethnicity and, thus, assume a package of other traits for me, too. Shinner dissects her love-hate relationship with her stereotypical Jewish bodily traits—her flat feet, her slumping posture, her nose before it was reshaped by surgery—and explains how this tension is central to her sense of self. On one hand, she has pride in her “tribe,” to use her word, and a desire to be recognized as a member of it: She’s resentful when a colleague says, I didn’t know you were Jewish . On the other, she considers the benefits of assimilation that her decidedly gentile name and newly minted snub nose may have granted her, among them, the choice of when and whether to disclose that she is Jewish. “Sure, I want to be taken for who I am, but . . . I don’t want to suffer too much for it.” But Shinner wonders both if there is disloyalty in this assimilation and what price she pays for it. “Anonymity lets others fill in the blanks.”

While the first section of the book is devoted to essays about Shinner and her relationship with her own body, the second section shifts the focus to the bodies of others: Shinner’s mother, who survived breast cancer only to die in her fifties from thyroid cancer; her father, who died after a stroke when Shinner was in her late thirties; and her great-aunt, for whom Shinner had responsibility as the depressed elderly woman neared death. Shinner struggles to understand the relationship between these failing bodies and the souls that they sheltered. As she says in an essay on the disconcerting autopsy of her father’s body, “Postmortem”:

I feel loyal to my body. It is, for better and for worse, for all its betrayals and my abuses, mine. I imagine a final leave-taking, when death comes, and body and soul part ways: Bye-bye, the soul might say to the body…. And the soul takes off. And the body is at rest.

In these smart and engaging essays, Shinner challenges us to reconsider our bodies—in particular women’s bodies, in particular Jewish bodies—but her point is more general, too. Our existence is intricately linked to our ongoing physical health. No matter how much we malign how our bodies look or function, how they regularly disappoint us, we cannot exist on this planet without them. Throughout the collection, Shinner employs a funny, self-deprecating tone as she tells some of the most embarrassing, intimate, and hilarious details of her life: her teenaged nose job, the degradations of a bra-fitting, guiltily eating pigs-in-a-blanket on Rosh Hashanah, her obsession with choosing the just-right burial plot for herself and her partner. Her willingness to share these most private moments with us gives her authority when she shares, too, her wisdom and insights. She stands naked before us, both in body and in mind, fully exposed, fully vulnerable, fully human.

About the Reviewer

Jennifer Wisner Kelly’s stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in the Massachusetts Review, the Greensboro Review, the Beloit Fiction Journal, Poets & Writers Magazine, Colorado Review, and others. She has attended residencies at the Jentel Foundation, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. Kelly is the Book Review Editor for fiction and nonfiction titles at Colorado Review.

You Feel So Mortal

Essays on the body.

Peggy Shinner

See the author’s website .

224 pages | 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 | © 2014

Biography and Letters

Chicago and Illinois

Literature and Literary Criticism: American and Canadian Literature

- Table of contents

- Author Events

Related Titles

“Peggy Shinner writes with self-critical candor and an often rueful wit to combine the intimate with the historical, the deeply private with the Google-able in an engaging, endearing, and wholly unexpected way. This is not a memoir, but we get to know her very well; we emerge feeling we’ve watched a woman grow up and learn some important things about the reach and the limits of her needs and her daring. And, as in the best writing, we thereby discover a great deal that pertains to us.”

Rosellen Brown, author of Half a Heart

“Shinner is a witty and insightful storyteller and brilliant thinker, attentive to the ways the body shapes up in your mind and the world. You Feel So Mortal makes you feel so alive.”

Aleksandar Hemon, author of The Lazarus Project

“Like the transparent pages of fine anatomy books that peel apart the strata of the body, the nested essays in Shinner’s You Feel So Mortal get under our skins. She excavates, in spades, the indicative and intricate nature of our layered and larded corporeal selves. Lyrically adept, she effortlessly reanimates Schwartz’s heavy bear, making the big beast of the body dance the horah , turning the ‘withness’ of our heft into a helium meringue, a gauzy heartache, a lost lost.”

Michael Martone, author of Four for a Quarter

“ You Feel So Mortal is a book I found nearly impossible to put down, and when I was forced to do so, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Shinner’s warm and funny voice, along with her immense, inquiring, humane intelligence, makes the essays in this book—which concern identity, mortality, romantic and filial love, gender—a surpassing intellectual gem that entertains and engages readers with every single word. I adored this book.”

Christine Sneed, author of Little Known Facts

“In her examinations of the body, Shinner frequently makes the mundane poetic, and in her exploration of grief, she finds beauty.”

“The kind of chick lit we can get behind.”

“Throughout the book Peggy Shinner tells you all sorts of things about herself, some factual, some embarrassing, but in just a few words, she shows you the most important thing of all: what a tremendous writer she is.”

Chicago Reader

“A daring collection of 12 thoughtfully crafted and executed essays pertaining to body image and introspective interpretations of one’s multifaceted beauty in relation to its original form. The compilation of personal triumphs and hardships in You Feel So Mortal is dynamically inclined—from reveling in one’s own inner beauty, to bra sizes, shapes, colors, hair configurations, and more. The witty and provocative anthology is poised to turn this passionate project into one unforgettable journey spanning oceans, continents, and heritages.”

Windy City Media

“In You Feel So Mortal: Essays on the Body , Shinner’s smart, witty, bittersweet book of writings about her own body and those of others, the author examines the journey of life inside that most imperfect of vessels. Beginning with acute, often rueful observations and stories about her own body (feet, nose, hair, back, breasts, etc.), Shinner then casts an ever-wider intellectual net that dredges up a host of cultural associations with the body throughout history, from antiquity to the present. In the process, she lays bare the ways in which truth and distortion about our physical selves have intertwined to shape our collective thinking about large groups of people, in particular women and Jews, for good or ill.”

Chicago Tribune

“These essays, even when the topics are ugly, shimmer with Shinner’s intelligence, honesty, and humor. She’s an observer of her body and the world it moves through, but more than that, she’s an affectionate fan: ‘I feel loyal to my body. It is, for better and for worse, for all its betrayals and my abuses, mine.’”

Boston Globe

“Her interests are wide-ranging, fueled by a deep curiosity and a talent for research. The connections she draws between them are frequently surprising and delightful, and sometimes devastating. The intertextuality at times seems randomized, but Shinner’s gracefulness and dexterity with language ties the narrative together in a bundle that reads as wholly intentional, experiential, and warming. And, despite discussing at great length the familiar tropes of the body and self-criticism, her work reconstructs the history of the body as it applies to modernity in a way that retells and reclaims not only the narrative of her own body, but how we might approach ours and the bodies of others, as well.”

Lambda Literary

“You Feel So Mortal is deeply personal, detailed, and thoughtful. Shinner does not apparently set out to take on large, sweeping themes, yet by showing clearly and tenderly how one person navigates this existence her book provides a window into being human—not in an abstract, conceptual way, but concretely and personally, being a specific human being. It is a delight not to be missed.”

Washington Independent Review of Books

"Shinner’s twelve remarkable essays are anything but the usual fare, instead taking as her subject the complicated relationship between our bodies and our souls."

Colorado Review

“A piercingly intimate and personal self-portrait, one that aches with questions, confidences, admissions, and resentments.”

“From discovering her mother’s correspondence with the notorious but aging and imprisoned murderer, Nathan Leopold—of the infamous Leopold and Loeb—to scouting out a site for the eventual interment of her own body, to authorizing—and then facing the unsettling particulars of—her father’s autopsy, she engages us with story-telling that is starkly funny and tender but never sentimental. And because she is a deft essayist—capable of pushing that engine to full throttle—she presses intuitively and ambitiously beyond her own experience to explore the larger, often darker implications emanating from it.”

River Teeth

“I derived as much sheer pleasure from these exquisitely crafted and often mordantly funny essays as from anything else I read this year. This is a book you curl up with in a comfortable chair with a mug of steaming tea, as the world reshapes itself around you.”

Kevin Nance | Printer's Row

Table of Contents

PART ONE Family Feet Pocketing Debutante, Dowager, Beggar The Knife Elective The Fitting(s) Berenice’s Hair PART TWO Leopold and Shinner Tax Time Mood Medicine Intimate Possession Postmortem

Acknowledgments

Doing Style

Constantine V. Nakassis

Of Beards and Men

Christopher Oldstone-Moore

Eating the Enlightenment

E. C. Spary

Dinner with Darwin

Jonathan Silvertown

Be the first to know

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Traditional Academic Essays In Three Parts

Part i: the introduction.

An introduction is usually the first paragraph of your academic essay. If you’re writing a long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to introduce your topic to your reader. A good introduction does 2 things:

- Gets the reader’s attention. You can get a reader’s attention by telling a story, providing a statistic, pointing out something strange or interesting, providing and discussing an interesting quote, etc. Be interesting and find some original angle via which to engage others in your topic.

- Provides a specific and debatable thesis statement. The thesis statement is usually just one sentence long, but it might be longer—even a whole paragraph—if the essay you’re writing is long. A good thesis statement makes a debatable point, meaning a point someone might disagree with and argue against. It also serves as a roadmap for what you argue in your paper.

Part II: The Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you prove your thesis and move you along a compelling trajectory from your introduction to your conclusion. If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay:

Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph. All of the sentences in the paragraph connect to it. Keep in mind that main ideas are…

- like labels. They appear in the first sentence of the paragraph and tell your reader what’s inside the paragraph.

- arguable. They’re not statements of fact; they’re debatable points that you prove with evidence.

- focused. Make a specific point in each paragraph and then prove that point.

Evidence. The parts of a paragraph that prove the main idea. You might include different types of evidence in different sentences. Keep in mind that different disciplines have different ideas about what counts as evidence and they adhere to different citation styles. Examples of evidence include…

- quotations and/or paraphrases from sources.

- facts , e.g. statistics or findings from studies you’ve conducted.

- narratives and/or descriptions , e.g. of your own experiences.

Analysis. The parts of a paragraph that explain the evidence. Make sure you tie the evidence you provide back to the paragraph’s main idea. In other words, discuss the evidence.

Transition. The part of a paragraph that helps you move fluidly from the last paragraph. Transitions appear in topic sentences along with main ideas, and they look both backward and forward in order to help you connect your ideas for your reader. Don’t end paragraphs with transitions; start with them.

Keep in mind that MEAT does not occur in that order. The “ T ransition” and the “ M ain Idea” often combine to form the first sentence—the topic sentence—and then paragraphs contain multiple sentences of evidence and analysis. For example, a paragraph might look like this: TM. E. E. A. E. E. A. A.

Part III: The Conclusion

A conclusion is the last paragraph of your essay, or, if you’re writing a really long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to conclude. A conclusion typically does one of two things—or, of course, it can do both:

- Summarizes the argument. Some instructors expect you not to say anything new in your conclusion. They just want you to restate your main points. Especially if you’ve made a long and complicated argument, it’s useful to restate your main points for your reader by the time you’ve gotten to your conclusion. If you opt to do so, keep in mind that you should use different language than you used in your introduction and your body paragraphs. The introduction and conclusion shouldn’t be the same.

- For example, your argument might be significant to studies of a certain time period .

- Alternately, it might be significant to a certain geographical region .

- Alternately still, it might influence how your readers think about the future . You might even opt to speculate about the future and/or call your readers to action in your conclusion.

Handout by Dr. Liliana Naydan. Do not reproduce without permission.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

You'll Find 12 Fresh And Unforgettable Essays In 'Black Is The Body'

Maureen Corrigan

Black Is the Body

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Before I talk about individual essays in Emily Bernard's new book, Black Is the Body, I want to pay it an all-inclusive tribute. Even the best essay collections routinely contain some filler, but of the 12 essays here, there's not one that even comes close to being forgettable.

Bernard's language is fresh, poetically compact and often witty. She writes about growing up black in the South and living black as an adult in the snow globe state of Vermont. She considers subjects that hit close to the bone like the loving complications of her own interracial marriage and adopting her two daughters from Ethiopia.

In her introduction, Bernard tells us that this book "was conceived in a hospital ... [where I] was recovering from surgery on my lower bowel, which had been damaged in a stabbing" — a "bizarre act of violence" that helped "set me free" as a storyteller.

That's a literary origin tale you don't hear every day, but shock value is the least of the reasons why Bernard shares it with us. Instead, the visceral reality of her scarred, winding intestines becomes an implicit metaphor for the kind of writing she hopes to achieve: contradictory, messy and very personal.

All of these essays are about race and are rooted, autobiographically, in the blackness of Bernard's own body. Through her writing, Bernard says, she wanted:

to contribute something to the American racial drama besides the enduring narrative of black innocence and white guilt. ... [There] are other true stories I needed to explore. ... The only way I knew how to do this was by letting the blood flow, and following the trail of my own ambivalence.

Emily Bernard is a professor of English at the University of Vermont. Her new memoir is Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother's Time, My Mother's Time, and Mine. Alison Segar/Penguin Random House hide caption

Emily Bernard is a professor of English at the University of Vermont. Her new memoir is Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother's Time, My Mother's Time, and Mine.

In a collection full of standouts, one of the best is an essay called "Teaching The N-Word," in which Bernard ushers us into her African-American autobiography class at the University of Vermont. All of her 11 students are white.

The expected way this essay would unfold would be for Bernard to poke gentle fun at these liberal white students, whose refusal to say the "n-word," doesn't absolve them from their own unconscious racism. Tie all this up with an in-class epiphany and you've got yourself a nice essay.

But Bernard has been through that life-altering knife attack; she doesn't do what's expected. Instead, much of this confessional essay focuses on Bernard's own moments of self-deception as a black professor at an overwhelmingly white university. For instance, she says she instructs her students in her African-American studies classes, "not to confuse my body with the body of the book."

In part, she's inviting her white students to have the intellectual courage to criticize novels like Their Eyes Were Watching God and Invisible Man even though she, their professor, is black.

Bernard also tells her (again, mostly white) students that, "This material is not the exclusive property of students of color. ... This is American literature, American experience, after all." But, to us readers Bernard admits feeling claims to this literature that are less democratic: "Sometimes I give this part of my lecture, but not always. Sometimes I give it and then regret it later."

Another essay that complicates thinking about race is called "Interstates." The opening situation reads like an updated version of the film, The Green Book : Bernard, her white then-fiancé, John, and her parents are driving to a family reunion in Mississippi when their car gets a flat. Bernard describes how John, who's behind the wheel, pulls over to change the tire while "[t]here we stand — my black family, as vulnerable as an open window on a hot summer day." A page later, Bernard offers this observation:

John was not ignorant of the root of my father's anxiety. But the danger presented by the flat tire took precedence over any other type of danger. Somewhere between the clarity of [John's] focus and the complexity of my father's anxiety, perhaps, lies the difference between living white and living black in America. ... I see the difference. Mostly I despise it. But my belief that difference can engender pleasure as well as pain made it possible for me to marry a white man.

Those are words capable of sparking one of those halting discussions about race that Bernard conducts in her classrooms. In Black Is the Body, Bernard proves herself to be a revelatory storyteller of race in America who can hold her own with some of those great writers she teaches.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.