- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Political Science

Volume 24, 2021, review article, open access, the backlash against globalization.

- Stefanie Walter 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: Department of Political Science, University of Zurich, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 24:421-442 (Volume publication date May 2021) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405

- First published as a Review in Advance on February 12, 2021

- Copyright © 2021 by Annual Reviews. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See credit lines of images or other third-party material in this article for license information

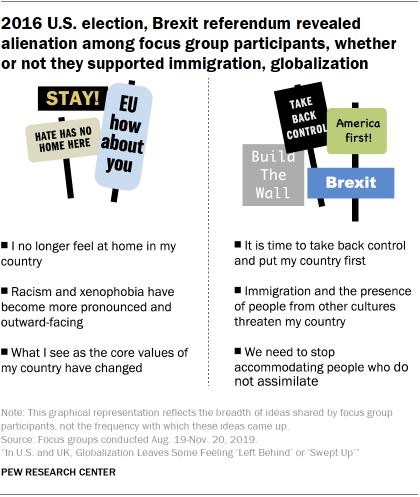

In recent years, the world has seen a rising backlash against globalization. This article reviews the nature, causes, and consequences of the globalization backlash. It shows that, contrary to a popular narrative, the backlash is not associated with a large swing in public opinion against globalization but is rather a result of its politicization. The increasing influence of globalization-skeptic actors has resulted in more protectionist, isolationist, and nationalist policies, some of which fundamentally threaten pillars of the contemporary international order. Both material and nonmaterial causes drive the globalization backlash, and these causes interact and mediate each other. The consequences are shaped by the responses of societal actors, national governments, and international policy makers. These responses can either yield to and reinforce the global backlash or push back against it. Understanding these dynamics will be an important task for future research.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Abou-Chadi T , Helbling M. 2018 . How immigration reforms affect voting behavior. Political Stud 66 : 3 687– 717 [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Chadi T , Krause W. 2018 . The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. Br. J. Political Sci. 50 : 3 829– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist J , Copelovitch M , Walter S. 2020 . The political consequences of external economic shocks: evidence from Poland. Am. J. Political Sci. 64 : 4 904– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Alter KJ , Gathii JT , Helfer LR. 2016 . Backlash against international courts in west, east and southern Africa: causes and consequences. Eur. J. Int. Law 27 : 2 293– 328 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B , Bernauer T , Kachi A. 2019 . Does international pooling of authority affect the perceived legitimacy of global governance?. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 4 661– 83 [Google Scholar]

- Ansell B , Adler D 2019 . Brexit and the politics of housing in Britain. Political Q 90 : S2 105– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Armingeon K , Guthmann K. 2014 . Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. Eur. J. Political Res. 53 : 3 423– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bakker R , De Vries C , Edwards E , Hooghe L , Jolly S et al. 2015 . Measuring party positions in Europe: the Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Politics 21 : 1 143– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Ballard-Rosa C , Malik M , Rickard S , Scheve K 2021 . The economic origins of authoritarian values: evidence from local trade shocks in the United Kingdom. Comp. Political Stud . In press [Google Scholar]

- Bearce DH , Jolliff Scott BJ 2019 . Popular non-support for international organizations: How extensive and what does this represent?. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 2 187– 216 [Google Scholar]

- Beramendi P , Häusermann S , Kitschelt H , Kriesi H. 2015 . The Politics of Advanced Capitalism New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Bisbee J , Mosley L , Pepinsky TB , Rosendorff BP. 2020 . Decompensating domestically: the political economy of anti-globalism. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 7 1090– 102 [Google Scholar]

- Bischof D , Wagner M. 2019 . Do voters polarize when radical parties enter parliament?. Am. J. Political Sci. 63 : 4 888– 904 [Google Scholar]

- Blauberger M , Heindlmaier A , Kramer D , Martinsen DS , Sampson Thierry J et al. 2018 . ECJ Judges read the morning papers. Explaining the turnaround of European citizenship jurisprudence. J. Eur. Public Policy 25 : 10 1422– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Bølstad J. 2014 . Dynamics of European integration: public opinion in the core and periphery. Eur. Union Politics 16 : 1 23– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Bornschier S. 2018 . Globalization, cleavages, and the radical right. The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right J Rydgren 212– 38 Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Bressanelli E , Koop C , Reh C. 2020 . EU Actors under pressure: politicisation and depoliticisation as strategic responses. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 3 329– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Broz L , Frieden J , Weymouth S. 2021 . Populism in place: the economic geography of the globalization backlash. Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- Brutger R , Strezhnev A. 2018 . International disputes, media coverage, and backlash against international law Paper presented at the International Political Economy Society Conference Nov. 2–3 Cambridge, MA: https://www.internationalpoliticaleconomysociety.org/sites/default/files/conference_files/IPES_Proposal_2018_Brutger_Strezhnev_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon B. 2013 . Inequality and anti-globalization backlash by political parties. Eur. Union Politics 14 : 3 408– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon B , Oliver T , Trubowitz P. 2017 . Globalization, domestic politics, and transatlantic relations. Int. Politics 54 : 4 420– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Bursztyn L , Egorov G , Fiorin S. 2017 . From extreme to mainstream: how social norms unravel NBER Work. Pap. 23415 [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie A , Carson A. 2019 . Reckless rhetoric? Compliance pessimism and international order in the age of Trump. J. Politics 81 : 2 739– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Carreras M , Irepoglu Carreras Y , Bowler S 2019 . Long-term economic distress, cultural backlash, and support for Brexit. Comp. Political Stud. 52 : 9 1396– 424 [Google Scholar]

- Chilton AS , Milner HV , Tingley D. 2017 . Reciprocity and public opposition to foreign direct investment. Br. J. Political Sci. 50 : 1 129– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Chopin T , Lequesne C. 2020 . Disintegration reversed: Brexit and the cohesiveness of the EU27. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud . In press [Google Scholar]

- Colantone I , Stanig P. 2018a . The trade origins of economic nationalism: import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. Am. J. Political Sci. 62 : 4 936– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Colantone I , Stanig P. 2018b . Global competition and Brexit. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 112 : 2 201– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Colantone I , Stanig P. 2019 . The surge of economic nationalism in Western Europe. J. Econ. Perspect. 33 : 4 128– 51 [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu C , Mattoo A , Ruta M. 2020 . The global trade slowdown: cyclical or structural?. World Bank Econ. Rev. 34 : 1 121– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Cooley A , Nexon D. 2020 . Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz MML , Damron R. 2009 . Constructing tolerance: how the welfare state shapes attitudes about immigrants. Comp. Political Stud. 42 : 3 437– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Dancygier RM , Donnelly MJ. 2013 . Sectoral economies, economic contexts, and attitudes toward immigration. J. Politics 75 : 1 17– 35 [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C 2017 . Benchmarking Brexit: how the British decision to leave shapes EU public opinion. J. Common. Market Stud. 55 : 38– 53 [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C. 2018 . Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C , Edwards EE. 2009 . Taking Europe to its extremes: extremist parties and public Euroscepticism. Party Politics 15 : 1 5– 28 [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C , Hobolt S. 2020 . Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C , Hobolt S , Walter S. 2021 . Politicizing international cooperation: the mass public, political entrepreneurs and political opportunity structures. Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde P. 2011 . No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration. J. Eur. Integrat. 33 : 5 559– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta D , Andretta M , Calle A , Combes H , Eggert N et al. 2015 . Global Justice Movement: Cross-National and Transnational Perspectives New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth LM , Tallberg J. 2020 . Elite communication and the popular legitimacy of international organizations. Br. J. Political Sci. In press [Google Scholar]

- Dippel C , Gold R , Heblich S. 2015 . Globalization and its (dis-)content: trade shocks and voting behavior NBER Work. Pap. 21812 [Google Scholar]

- Döring H , Manow P. 2019 . Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Modern Democracies Dev. version. http://www.parlgov.org/ . Accessed June 25, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Dorn D , Hanson G , Majlesi K. 2020 . Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. Am . E c on. Rev. 110 : 10 3139– 83 [Google Scholar]

- Drezner DW. 2019 . Present at the destruction: the Trump administration and the foreign policy bureaucracy. J. Politics 81 : 2 723– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Duina F. 2019 . Why the excitement? Values, identities, and the politicization of EU trade policy with North America. J. Eur. Public Policy 26 : 12 1866– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Ecker-Ehrhardt M. 2014 . Why parties politicise international institutions: on globalisation backlash and authority contestation. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 21 : 6 1275– 312 [Google Scholar]

- Ecker-Ehrhardt M. 2018 . International organizations “going public”? An event history analysis of public communication reforms 1950–2015. Int. Stud. Q. 62 : 4 723– 36 [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich SD. 2018 . The Politics of Fair Trade: Moving Beyond Free Trade and Protection Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich SD , Maestas C. 2010 . Risk, risk orientation, and policy opinions: the case of free trade. Political Psychol 5 : 31 657– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni M. 2020 . Death of international organizations. The organizational ecology of intergovernmental organizations, 1815–2015. Rev. Int. Organ. 15 : 1815– 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Engler S , Weisstanner D. 2020 . The threat of social decline: income inequality and radical right support. J. Eur. Public Policy In press [Google Scholar]

- Farrell H , Newman AL. 2019 . Weaponized interdependence: how global economic networks shape state coercion. Int. Secur. 44 : 1 42– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum JJ , Hall AB. 2015 . How legislators respond to localized economic shocks: evidence from Chinese import competition. J. Politics 77 : 4 1012– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer T. 2019 . Did austerity cause Brexit?. Am. Econ. Rev. 109 : 11 3849– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Foster C , Frieden J. 2017 . Crisis of trust: socio-economic determinants of Europeans’ confidence in government. Eur. Union Politics 18 : 4 511– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Frey CB , Berger T , Chen C. 2018 . Political machinery: Did robots swing the 2016 US presidential election?. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 34 : 3 418– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Funke M , Schularick M , Trebesch C. 2016 . Going to extremes: politics after financial crises, 1870–2014. Eur. Econ. Rev. 88 : 227– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Gidron N , Hall P. 2017 . The politics of social status: economic and cultural roots of the populist right. Br. J. Sociol. 68 : S1 S57– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Golder M. 2016 . Far right parties in Europe. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 19 : 477– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SW , Pepinsky T. 2021 . The exclusionary foundations of embedded liberalism. Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin M , Milazzo C. 2017 . Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 19 : 3 450– 64 [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. 2018 . Life, death, or zombie? The vitality of international organizations. Int. Stud. Q. 62 : 1 1– 13 [Google Scholar]

- Gronau J , Schmidtke H. 2016 . The quest for legitimacy in world politics—international institutions’ legitimation strategies. Rev. Int. Stud. 42 : 3 535– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Grynberg C , Walter S , Wasserfallen F. 2019 . Expectations, vote choice, and opinion stability since the 2016 Brexit referendum. Eur. Union Politics 21 : 2 255– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger A , Saunders EN. 2017 . Mapping the boundaries of elite cues: how elites shape mass opinion across international issues. Int. Stud. Q. 61 : 2 425– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Gygli S , Haelg F , Potrafke N , Sturm J-E. 2019 . The KOF globalisation index—revisited. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 3 543– 74 [Google Scholar]

- Gyongyosi G , Verner E. 2018 . Financial crisis, creditor-debtor conflict, and political extremism Paper presented at Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik 2018: Digitale Wirtschaft—Session: International Financial Markets II, No. F19-V3, Sep. 25 Freiburg im Breisgau, Ger: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/181587 [Google Scholar]

- Ha E. 2012 . Globalization, government ideology, and income inequality in developing countries. J. Politics 74 : 2 541– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann S , Hobolt S , Wratil C. 2017 . Government responsiveness in the European Union: evidence from council voting. Comp. Political Stud. 50 : 6 850– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller J , Hopkins DJ. 2014 . Public attitudes toward immigration. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 17 : 225– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Hays J , Ehrlich S , Peinhardt C. 2005 . Government spending and public support for trade in the OECD: an empirical test of the embedded liberalism thesis. Int. Organ. 59 : 2 473– 94 [Google Scholar]

- Hays J , Lim J , Spoon J-J. 2019 . The path from trade to right-wing populism in Europe. Elect. Stud 60 : 102038 [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt S. 2016 . The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. J. Eur. Public Policy 23 : 9 1259– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt S , De Vries C. 2016 . Public support for European integration. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 19 : 413– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt S , Leeper T , Tilley J. 2020 . Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of Brexit. Br. J. Political Sci. In press [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe L , Marks G. 2009 . A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. Br. J. Political Sci. 39 : 1 1– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe L , Marks G. 2018 . Cleavage theory meets Europe's crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. J. Eur. Public Policy 25 : 1 109– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin J , Blyth M. 2019 . The global economics of European populism: growth regimes and party system change in Europe (the Government and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro lecture 2017). Gov. Oppos. 54 : 2 193– 225 [Google Scholar]

- Hutter S , Grande E , Kriesi H. 2016 . Politicising Europe New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hutter S , Kriesi H. 2019 . Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. J. Eur. Public Policy 26 : 7 996– 1017 [Google Scholar]

- Im ZJ , Mayer N , Palier B , Rovny J. 2019 . The “losers of automation”: a reservoir of votes for the radical right?. Res. Politics 6 : 1 https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822395 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- IMF (Int. Monet. Fund) 2019 . World Economic Outlook 2019 Washington, DC: Int. Monet. Fund [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DA. 2017 . The false promise of protectionism: Why Trump's trade policy could backfire. Foreign Aff 96 : 45– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Jedinger A , Burger AM. 2020 . The ideological foundations of economic protectionism: authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and the moderating role of political involvement. Political Psychol 41 : 2 403– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Johns L , Pelc KJ , Wellhausen RL. 2019 . How a retreat from global economic governance may empower business interests. J. Politics 81 : 2 731– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Jurado I , Walter S , Konstantinidis N , Dinas E. 2020 . Keeping the euro at any cost? Explaining preferences for euro membership in Greece. Eur. Union Politics. 21 : 3 383– 405 [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen RD. 2017 . Europe's other democratic deficit: national authoritarianism in Europe's democratic union. Gov. Oppos. 52 : 2 211– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Kiratli OS. 2020 . Together or not? Dynamics of public attitudes on UN and NATO. Political Stud In press [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi H , Grande E , Lachat R , Dolezal M , Bornschier S , Frey T. 2006 . Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: six European countries compared. Eur. J. Political Res. 45 : 6 921– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi H , Grande E , Lachat R , Dolezal M , Bornschier S , Frey T. 2008 . West European Politics in the Age of Globalization New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Kurer T. 2020 . The declining middle: occupational change, social status, and the populist right. Comp. Political Stud. 53 : 10–11 1798– 1835 [Google Scholar]

- Lacewell OP. 2017 . Beyond policy positions: how party type conditions programmatic responses to globalization pressures. Party Politics 23 : 4 448– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Lake D , Martin L , Risse T. 2021 . Challenges to the liberal order: reflections on International Organization . Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- Lang VF , Tavares MMM. 2018 . The Distribution of Gains from Globalization Washington, DC: Int. Monet. Fund [Google Scholar]

- Linardi S , Rudra N. 2020 . Globalization and willingness to support the poor in developing countries: an experiment in India. Comp. Political Stud. 53 : 10–11 1656– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Lü X , Scheve K , Slaughter MJ. 2012 . Inequity aversion and the international distribution of trade protection. Am. J. Political Sci. 56 : 3 638– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Mader M , Steiner ND , Schoen H. 2019 . The globalisation divide in the public mind: belief systems on globalisation and their electoral consequences. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 10 1526– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Madsen MR , Cebulak P , Wiebusch M. 2018 . Backlash against international courts: explaining the forms and patterns of resistance to international courts. Int. J. Law Context 14 : 2 197– 220 [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra N , Margalit Y , Mo CH 2013 . Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. Am. J. Political Sci. 57 : 2 391– 410 [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield E , Rudra N. 2021 . Embedded liberalism in the digital era. Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield ED , Mutz D. 2009 . Support for free trade: self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. Int. Organ. 63 : 2 425– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield ED , Mutz DC. 2013 . US versus them: mass attitudes toward offshore outsourcing. World Politics 65 : 4 571– 608 [Google Scholar]

- Margalit Y. 2012 . Lost in globalization: international economic integration and the sources of popular discontent. Int. Stud. Q. 56 : 3 484– 500 [Google Scholar]

- Meijers MJ. 2017 . Contagious Euroscepticism: the impact of Eurosceptic support on mainstream party positions on European integration. Party Politics 23 : 4 413– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Menendez I , Owen E , Walter S 2018 . Low skill products by high skill workers: the distributive effects of trade in developing countries Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association Aug. 30–Sep. 2 Boston, MA: [Google Scholar]

- Meunier S , Czesana R. 2019 . From back rooms to the street? A research agenda for explaining variation in the public salience of trade policy-making in Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 26 : 12 1847– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Milner H. 2021 . Voting for populism in Europe: globalization, technological change, and the extreme right. Comp. Political Stud . In press [Google Scholar]

- Moschella M , Pinto L , Martocchia Diodati N 2020 . Let's speak more? How the ECB responds to public contestation. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 3 400– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Mudde C. 2013 . Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: So what?. Eur. J. Political Res. 52 : 1 1– 19 [Google Scholar]

- Mutz DC. 2018 . Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. PNAS 115 : 19 E4330– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M. 2020 . Survey experiments in international political economy: what we (don't) know about the backlash against globalization. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 23 : 333– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M , Urata S. 2013 . Free trade agreements and domestic politics: the case of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 8 : 2 326– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q , Spilker G 2019 . The elephant in the negotiation room: PTAs through the eyes of citizens. The Shifting Landscape of Global Trade Governance: World Trade Forum G Spilker, M Elsig, M Hahn 17– 47 New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Nooruddin I , Rudra N. 2014 . Are developing countries really defying the embedded liberalism compact?. World Politics 66 : 4 603– 40 [Google Scholar]

- Norris P , Inglehart R. 2019 . Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke KH. 2019 . Economic history and contemporary challenges to globalization. J. Econ. Hist. 79 : 2 356– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Obstfeld M. 2020 . Globalization cycles. Italian Econ. J. 6 : 1 1– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Owen E. 2017 . Exposure to offshoring and the politics of trade liberalization: debate and votes on free trade agreements in the US House of Representatives, 2001–2006. Int. Stud. Q. 61 : 2 297– 311 [Google Scholar]

- Owen E , Johnston N. 2017 . Occupation and the political economy of trade: job routineness, offshorability and protectionist sentiment. Int. Organ. 71 : 4 665– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Owen E , Walter S. 2017 . Open economy politics and Brexit: insights, puzzles, and ways forward. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 24 : 2 179– 202 [Google Scholar]

- Palmtag T , Rommel T , Walter S. 2018 . International trade and public protest: evidence from Russian regions. Int. Stud. Q. 64 : 4 939– 55 [Google Scholar]

- Peinhardt C , Wellhausen RL. 2016 . Withdrawing from investment treaties but protecting investment. Glob. Policy 7 : 4 571– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Pepinsky T , Walter S. 2019 . Introduction to the debate section: understanding contemporary challenges to the global order. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 7 1074– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Pevehouse JCW , Nordstrom T , McManus RW , Jamison AS. 2019 . Tracking organizations in the world: the Correlates of War IGO Version 3.0 datasets. J. Peace Res. 57 : 3 492– 503 [Google Scholar]

- Reh C , Bressanelli E , Koop C. 2020 . Responsive withdrawal? The politics of EU agenda-setting. J. Eur. Public Policy 27 : 3 419– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Risse T. 2010 . A Community of Europeans? Transnational Identities and Public Spheres Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Rocabert J , Schimmelfennig F , Crasnic L , Winzen T. 2019 . The rise of international parliamentary institutions: purpose and legitimation. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 4 607– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose A. 2018 . The revenge of the places that don't matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge J. Regions Econ. Soc. 11 : 1 189– 209 [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik D. 2018 . Populism and the economics of globalization. J. Int. Business Policy 1 : 12– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik D. 2020 . Why does globalization fuel populism? Economics, culture, and the rise of right-wing populism NBER Work. Pap. 27526 [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski R. 1989 . Commerce and Coalitions: How Trade Affects Domestic Political Alignments Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Rommel T , Walter S. 2018 . The electoral consequences of offshoring: how the globalization of production shapes party preferences. Comp. Political Stud. 51 : 5 621– 58 [Google Scholar]

- Roth S. 2018 . Introduction: contemporary counter-movements in the age of Brexit and Trump. Sociol. Res. Online 23 : 2 496– 506 [Google Scholar]

- Rudra N. 2008 . Globalization and the Race to the Bottom in Developing Countries: Who Really Gets Hurt ? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Ruggie J. 1982 . International regimes, transactions and change: embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order. Int. Organ. 36 : 2 379– 415 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. 2019 . The Responsive Union: National Elections and European Governance New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. 2020 . Public commitments as signals of responsiveness in the European Union. J. Politics 82 : 1 329– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Sciarini P , Lanz S , Nai A. 2015 . Till immigration do us part? Public opinion and the dilemma between immigration control and bilateral agreements. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 21 : 2 271– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen MR , Siczek T. 2017 . Better the devil you know? Risk-taking, globalization and populism in Great Britain. Eur. Union Politics 18 : 1 119– 36 [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D , McDowell D , Gueorguiev D. 2020 . Inside looking out: how international policy trends shape the politics of capital controls in China. Pac. Rev . In press [Google Scholar]

- Stephen MD , Zürn M. 2019 . Contested World Orders: Rising Powers, Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Politics of Authority Beyond the Nation-State New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Swank D , Betz H-G. 2003 . Globalization, the welfare state and right-wing populism in Western Europe. Socio-Econ. Rev. 1 : 2 215– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Tallberg J , Zürn M. 2019 . The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: introduction and framework. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 581– 606 [Google Scholar]

- Trubowitz P , Burgoon B. 2020 . The retreat of the west. Perspect. Politics In press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001218 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conf. Trade Dev.) 2020 . International Investment Agreements Navigator . https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements . Accessed July 4, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek B , Zaslove A 2017 . Populism and foreign policy. Oxford Handbook of Populism CR Kaltwasser, P Taggart, P Ochoa Espejo, P Ostiguy 384– 405 Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Voeten E. 2019 . Populism and backlashes against international courts. Perspect. Politics 18 : 2 407– 22 [Google Scholar]

- Volkens A , Krause W , Lehmann P , Matthieß T , Merz N et al. 2019 . The manifesto data collection Version 2019b. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR), updated Dec. 19, 2019. accessed July 15, 2020. https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/datasets [Google Scholar]

- von Borzyskowski I , Vabulas F. 2019 . Hello, goodbye: When do states withdraw from international organizations?. Rev. Int. Organ. 14 : 335– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Walter S. 2010 . Globalization and the welfare state: testing the microfoundations of the compensation hypothesis. Int. Stud. Q. 54 : 2 403– 26 [Google Scholar]

- Walter S. 2017 . Globalization and the demand-side of politics. How globalization shapes labor market risk perceptions and policy preferences. Political Sci. Res. Methods 5 : 1 55– 80 [Google Scholar]

- Walter S. 2020 . The mass politics of international disintegration Work. Pap. 105 Cent. Comp. Int. Stud., Univ. Zürich Zürich, Switz:. [Google Scholar]

- Walter S 2021 . Brexit domino? The political contagion effects of voter-endorsed withdrawals from international institutions. Comp. Political Stud In press. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414021997169 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S , Dinas E , Jurado I , Konstantinidis N. 2018 . Noncooperation by popular vote: expectations, foreign intervention, and the vote in the 2015 Greek bailout referendum. Int. Organ. 72 : 4 969– 94 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JC , Wallace J. 2021 . Domestic politics, China's rise, and the future of the liberal international order. Int. Organ. In press [Google Scholar]

- WTO (World Trade Organ.) 2020 . Annual report 2020 Rep., World Trade Organ Washington, DC: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/anrep20_e.htm [Google Scholar]

- Zaslove A. 2008 . Exclusion, community, and a populist political economy: the radical right as an anti-globalization movement. Comp. Eur. Politics 6 : 2 169– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Zaum D. 2013 . Legitimating International Organizations Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, framing theory, discursive institutionalism: the explanatory power of ideas and discourse, historical institutionalism in comparative politics, the origins and consequences of affective polarization in the united states, political trust and trustworthiness, public attitudes toward immigration, what have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research, what do we know about democratization after twenty years, economic determinants of electoral outcomes, public deliberation, discursive participation, and citizen engagement: a review of the empirical literature.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

David Brooks

Globalization Is Over. The Global Culture Wars Have Begun.

By David Brooks

Opinion Columnist

I’m from a fortunate generation. I can remember a time — about a quarter-century ago — when the world seemed to be coming together. The great Cold War contest between communism and capitalism appeared to be over. Democracy was still spreading. Nations were becoming more economically interdependent. The internet seemed ready to foster worldwide communications. It seemed as if there would be a global convergence around a set of universal values — freedom, equality, personal dignity, pluralism, human rights.

We called this process of convergence globalization. It was, first of all, an economic and a technological process — about growing trade and investment between nations and the spread of technologies that put, say, Wikipedia instantly at our fingertips. But globalization was also a political, social and moral process.

In the 1990s, the British sociologist Anthony Giddens argued that globalization is “a shift in our very life circumstances. It is the way we now live.” It involved “the intensification of worldwide social relations.” Globalization was about the integration of worldviews, products, ideas and culture.

This fit in with an academic theory that had been floating around called Modernization Theory. The idea was that as nations developed, they would become more like us in the West — the ones who had already modernized.

In the wider public conversation, it was sometimes assumed that nations all around the world would admire the success of the Western democracies and seek to imitate us. It was sometimes assumed that as people “modernized,” they would become more bourgeois, consumerist, peaceful — just like us. It was sometimes assumed that as societies modernized, they’d become more secular, just as in Europe and parts of the United States. They’d be more driven by the desire to make money than to conquer others. They’d be more driven by the desire to settle down into suburban homes than by the fanatical ideologies or the sort of hunger for prestige and conquest that had doomed humanity to centuries of war.

This was an optimistic vision of how history would evolve, a vision of progress and convergence. Unfortunately, this vision does not describe the world we live in today. The world is not converging anymore; it’s diverging. The process of globalization has slowed and, in some cases, even kicked into reverse. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights these trends. While Ukraine’s brave fight against authoritarian aggression is an inspiration in the West, much of the world remains unmoved, even sympathetic to Vladimir Putin.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Globalization: Making sense of the backlash

If you’ve searched “deglobalization” or “nearshoring” or “reshoring” lately, you’re not alone. Google queries of all three terms have surged in recent years.

It’s not hard to figure out why. Wars in Ukraine and now Gaza, U.S. tensions with China and Russia, supply chain breakdowns, and rising populism have all raised doubts about the future of globalization — and whether its promise of a more connected and interdependent world can ever be achieved.

Caroline Freund has a message for the naysayers.

“Deglobalization isn’t happening,” said Freund, the former director for trade, investment, and competitiveness at the World Bank who is now the dean of the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the University of California, San Diego. “What’s actually happening is a reshaping [of the world economy].”

Freund’s insight came during the kickoff session of the SIEPR Fall Policy Forum. The event, held annually by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), focused this year on the future of globalization and how the United States can help shape the world’s shifting landscape. The Oct. 27 forum convened more than 170 attendees and featured perspectives of top experts from government, business, and academia.

The first thing to keep in mind: Globalization has experienced setbacks before.

“The trajectory of globalization has not been linear over the past 150 years,” said Mark Duggan, The Trione Director at SIEPR and The Wayne and Jodi Cooperman Professor of Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, in his opening remarks. “Globalization has clearly had its drawbacks, [but] there is indeed good reason for optimism.”

Access the agenda and recordings of the panel sessions here

The weaponization of economic policy

At the daylong event, featured speakers and audience members delved into a host of major current events affecting U.S. policy at home and abroad — from China’s economic stumbles and Russia’s growing economy despite record-level western sanctions to the U.S. dollar’s seemingly unstoppable reign as the world’s dominant currency and the private sector’s outsized role in the artificial intelligence revolution.

The consensus: More than ever, there’s a need for coordination. Maurice Obstfeld, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, spoke of the war between Israel and Hamas that began Oct. 7.

“The tensions in the Mideast are going to roil the global economy and global cooperation in a way that is very hard to predict,” Obstfeld said in his keynote. Factor in common threats posed by climate change, pandemics, cyber breaches, and nuclear proliferation and, he said, it’s clear that “global cooperation is more essential than ever,” he said.

But what does that cooperation look like in practice? Right now, it’s about coalitions — whether it’s the U.S. teaming with Europe or Russia partnering with China — and using economic policy as weapons.

“We live in a world of market power that’s used not for economic reasons, but for geopolitical purposes,” said Oleg Itskhoki, an economics professor at UCLA and a speaker on the panel about trade tensions and a return to industrial policy. “Everything is weaponized.”

U.S. policy: Throw sand in the gears

Take, for example, U.S. restrictions on trade with China — in the form of tariffs on imports and export controls aimed at curbing China’s access to advanced semiconductor chips and the tools for making them. Or, consider the severe sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its western allies against Russia for starting a war in Ukraine.

On China tariffs and Russia sanctions, the results so far have been disappointing.

Chinese imports to the U.S. have fallen since tariffs were first imposed in 2016, but the numbers mask another problem, said Freund during the session on trade. Asian imports to the U.S., which have held steady, include products whose parts can be sourced to Chinese suppliers. “There’s still Chinese content in our imports,” she said. “It’s just now coming in a much less transparent way.”

As for Russia, the pain that the U.S. and its allies hoped to inflict on its economy by boycotting purchases of oil and gas and freezing assets hasn’t worked, said Itskhoki. China, India, and Turkey have stepped up trade with Russia. And European goods are making their way to Russia through third parties.

The lesson, Itskhoki said, is that weaponizing economic policy exacts a hefty toll on everyone.

Fellow panelist Emily Blanchard, the chief economist at the U.S. State Department, acknowledged that efforts by the U.S. and its allies to counter Chinese and Russian aggression through economic measures has had setbacks. But that doesn’t mean the West should stop trying.

“The objective is to throw sand into [Russia and China’s] gears,” said Blanchard, who is also a professor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business. This means making it as expensive as possible for them to sustain their aggression and — in Russia’s case — to also compromise the quality of the tools it’s using to try to defeat Ukraine.

“We’re clearly at a crossroads in the way that we in the United States, and countries around the world, approach their international economic policies [and their] domestic policies too,” she said.

Russia + China: A purely tactical alliance

On the newfound alliance between Russia and China, the speakers suggested it might not be as formidable as it seems. The strongest relationship between the two countries in more than 100 years is rooted in their shared perception that “enemies are everywhere,” said Kathryn Stoner, the Mosbacher Director and senior fellow at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law during a session on Russia and China.

Both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping face a similar challenge, panel speakers agreed: Trouble in their economies could lead to political strife.

For Putin, fallout from the war on Ukraine is exacerbating labor shortages and a steep drop in life expectancy linked to the pandemic, Stoner said. For Xi, the “triple whammy” of pandemic lockdowns, unsustainable government debt, and the lowest rate of direct foreign investment in three decades appears to be fueling internal dissent, said Minxin Pei, a political science professor at Claremont McKenna College.

Like Russia, China must grapple with worrisome demographic challenges. For Russia, according to Stoner, it’s a tight labor market and falling life expectancy from COVID-19 deaths and war casualties. For China, its high levels of unemployed youth, Pei said.

“This is a regime that knows that it does not have a popular mandate to the extent it used to have one, and that’s based on the economy,” he said.

Artificial intelligence: Winners and losers

It was standing room-only for a session on the global race to dominate artificial intelligence (AI) — and its far-reaching implications for worldwide security and wealth inequality.

AI will “superpower all the good, bad, and the ugly,” said Fei-Fei Li, the co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI) and unofficial “godmother” of AI who spoke on the panel.

Among AI’s potential for good: curing cancer, supercharging education, and tackling climate change.

Another speaker, Erik Brynjolfsson, the director of the Stanford Digital Economy Lab and a SIEPR senior fellow, predicted that AI will enable huge leaps in worker productivity in the coming decade that could be double what the Congressional Budget Office is predicting. “We’re (already) seeing eye-popping improvements in productivity,” he said, including in one study he co-authored earlier this year showing a 35 percent boost for junior-level workers.

Still, the panelists agreed that there will be winners and losers in the AI revolution. The risk that it could exacerbate wealth inequality — and undermine globalization’s promise of shared prosperity — is real.

This concern is one reason why the speakers were critical of the private sector’s lead in driving AI innovation. Universities haven’t been able to keep up with the speed and scale of AI advances. The same goes for the public sector.

“There are simply not enough technologists within government to actually be able to responsibly figure out how to govern this technology,” said Daniel Ho, a SIEPR senior fellow and the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law at Stanford Law School. Ho also serves on the National AI Advisory Committee .

The speakers’ insights proved timely. Three days later, on Oct. 30, President Biden released a widely anticipated executive order calling for AI safeguards . The following day, the United States and China were part of an international consortium that pledged at a United Nations summit to work together to address the technology's potentially "catastrophic" risks.

*All photos by Ryan Zhang

More News Topics

Trump’s tax-cut proposal shakes up social security debate.

- Media Mention

- Politics and Media

- Money and Finance

Can global supply chains be fixed?

- Research Highlight

- Global Development and Trade

- Regulation and Competition

Presidential debate fact check: Analyzing Trump, Harris on abortion, immigration, more

- Our Activities

- Get Involved

Reports, videos and workshops

Arguments for and against globalization

FOR Globalization

1. one billion people out of poverty.

Between 1990 and 2010, the number of people living in extreme poverty fell by half as a share of the total population in developing countries, from 43% to 21%—a reduction of almost 1 billion people.

Human development indicators have also been improving across the globe. Life expectancy has been increasing steadily everywhere, and most developing countries are now rapidly converging with the rich world; child mortality rates have gone down everywhere; literacy rates, access to clean water, electricity, and basic consumer goods, all of these indicators have been rising.

Scarcity has existed throughout human history. However, never before has the material well-being of so many people been improved in such a short space of time.

2. COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

As Adam Smith famously alluded to in The Wealth of Nations , a global free trade system allows countries to use their resources more efficiently, by selling what they produce best, while buying what other countries produce better.

In a 2011 publication , the OECD argued that comparative advantage is one of the most potent explanations of higher income growth in open economies. The differences between countries, including differences in broad policy agendas, create relative differences in productivity, giving rise to gains from trade.

3. INCREASED INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

Certain economists, such as Jagdish Bhagwati, argue that the trade openness brought about by globalisation can contribute to the spread of democracy, as “the benefits of trade brings prosperity that, in turn, creates or expands the middle class that then seeks the end of authoritarianism.” Princeton’s John Doces found that “globalisation measured as increased exports to the U.S. increases the level of democracy in the exporting country.”

Using data provided by Freedom House, George Mason economist Daniel T. Griswold found a correlation between economic openness and political and civil freedom across 123 countries.

AGAINST Globalization

1. job losses.

Critics often point out that globalisation has led to job losses in the developed world, notably in the manufacturing sector. For instance, the US has lost 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000.

What makes things worse is the sense that not everybody is playing by the same rules when it comes to global trade. A common refrain of the Trump administration in the US, for example, is that the West has opened its markets to Chinese exports, but China has not properly reciprocated. Globalization, as it currently exists, is making some in the developed world very rich, but hurting working class communities. This has been a gift to populist politicians, but it has been devastating to many communities in Europe and the US that relied on manufacturing.

2. EROSION OF STATE SOVEREIGNTY

Another common argument is that globalisation has eroded state sovereignty. International trade limits the ability of nation-states to control domestic economies, whereas international organisations and laws place limits on their decision-making abilities.

The Eurozone crisis proved that financial markets can topple governments just as easily as elections. Yet there is no democratic control over financial markets.

Large multinationals exploit legal loopholes (and use well-paid lawyers and accountants) to help them avoid taxes. They offshore their operations to countries with weak labour laws and environmental protection, circumventing higher standards in the developed world (despite selling their products there).

3. INCREASED INEQUALITY

Globalization has made some people very rich. The majority, however, are given scraps. The 2018 World Inequality Report shows that inequality is rising across the globe (particularly in rapidly-developing economies such as India and China).

Free market critics, such as the economists Joseph Stiglitz and Ha-Joon Chang, argue that globalisation has perpetuated inequality in the world rather than reducing it.

In 2007, the International Monetary Fund suggested that inequality levels may have increased due to the introduction of new technology and foreign investment in developing countries.

Photo by william william on Unsplash

Enter your email address and password to log in to Debating Europe.

Not a supporter yet?

Registration

Are you registering as an individual citizen or a Debating Europe community partner?

Individual Citizen Registration Form Community Partner Registration Form

- The University Of Chicago

- Visitors & Fellows

- BFI Employment Opportunities

- Big Data Initiative

- Chicago Experiments Initiative

- Health Economics Initiative

- Industrial Organization Initiative

- International Economics and Economic Geography Initiative

- Macroeconomic Research Initiative

- Political Economics Initiative

- Price Theory Initiative

- Ronzetti Initiative for the Study of Labor Markets

- Becker Friedman Institute China

- Becker Friedman Institute Latin America

- Macro Finance Research Program

- Program in Behavioral Economics Research

- Development Innovation Lab

- Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago

- TMW Center for Early Learning + Public Health

- UChicago Scholars

- Visiting Scholars

- Saieh Family Fellows

This chapter synthesizes and critically reviews the modern instrumental variables (IV) literature that allows for unobserved heterogeneity in treatment effects (UHTE). We start by discussing why UHTE is often an essential aspect of IV applications in economics and we explain...

The jointly optimal monetary and fiscal policy mix in a multi-sector New Keynesian model with sectoral government spending and productivity shocks entails a separation of roles: Sectoral government spending optimally adjusts to sectoral output gaps and inflation rates—a policy supported...

Whether monetary incentives to change behavior work and how they should be structured are fundamental economic questions. We overcome typical data limitations in a large-scale field experiment on vaccination (N = 5,324) with a unique combination of administrative and survey...

- View All caret-right

Upcoming Events

2024 ai in social science conference, economic theory conference honoring phil reny, 2024 women in empirical microeconomics conference, past events, bfi student lunch series – the impact of incarceration on employment, earnings, and tax filing, macro financial modeling meeting spring 2012, modeling financial sector linkages to the macroeconomy, research briefs.

Interactive Research Briefs

- Media Mentions

- Press Releases

- Search Search

- Inequality Aversion, Populism, and the Backlash Against Globalization

- Globalization increases growth but the wealthy benefit more

- Over time, this rise in inequality causes resentment among voters

- In an attempt to reduce inequality, voters will favor politicians and policies that restrict the flow of goods, services, and people across borders

- The resulting autarky means that all are less wealthy, but there is less inequality

What was the source of this anti-globalization? Why did two wealthy countries turn their backs on one of the very forces—international trade and finance—that added to their own prosperity? In a new paper, “Inequality Aversion, Populism, and the Backlash Against Globalism,” Booth professors Lubos Pastor and Pietro Veronesi develop a theory that describes how growing income inequality spurred resentment among voters and set the stage for a populist backlash against global integration.

According to their theory, a retreat from globalization is a rational response to rising inequality. And the whole cycle—economic growth that exacerbates inequality, which ultimately quells globalization—is inevitable and only a matter of time. As Pastor and Veronesi frankly state: “Globalization carries the seeds of its own destruction.” The authors draw this stark conclusion from a model that connects rising income inequality with the growth of populism. And there is little that policymakers can do to avoid such a backlash against globalization, the model reveals, short of a massive tax overhaul that would move from a system of redistributive income taxes to consumption taxes.

The size of the pie matters, but so does the size of the slices

Pastor and Veronesi, two finance academics, came to this work on the rise and fall of globalism, in part, because of the connection between financial risk aversion and wealth accumulation (they have also done previous work on asset prices and political cycles, among other related subjects). People’s willingness to take on financial risk correlates to increased wealth, on average and over time, and it’s this propensity that distinguishes the agents in the authors’ model. Those agents who are more risk averse and who, consequently, fall further behind, eventually vote for populist politicians and policies.

A retreat from globalization is a rational response to rising inequality.

The authors define populism as “a political ideology pitching ordinary people, who are viewed as homogeneous and inherently good, against the established elites, who are deemed immoral and corrupt.” The agents in the model are assumed to dislike inequality, but their primary concern is with the elites of society who consume a great deal more than others.

Non-rich agents (who are not poor) naturally care about their own consumption, but they also care a great deal about how much the rich are consuming. These agents are intent on reducing the consumption of elites, even if that means limiting the growth of their own consumption. It’s not the size of the pie that matters, in other words, it’s the relative size of their own slice.

A common feature of populism is anti-globalism, according to the authors, which is perceived as benefiting the rich more than others. This is especially true when globalization is partnered with a highly developed financial system that allows for high risk-and-reward scenarios. It is no coincidence, then, that the two countries that recently experienced a populist revolt—the US and UK—have two of the most sophisticated financial systems in the world, and that those systems have generated vast amounts of wealth for relatively few players (while also benefiting many others to a lesser degree). Populists, likewise, favor politicians and policies that restrict globalization and that favor closed borders, both to people and to goods, according to this research, because such policies hurt elites more than others. In the authors’ model, the election of a populist leads to that country consuming its own products with no cross-border trading and no access to international finance (autarky).

Another feature of the authors’ model is that this shift to populism necessarily occurs during good times and not when a country is in a downturn. The reason is that during a growth period in a globalized economy with income inequality, like the recent lengthy (though gradual) upswing, the gap between the rich and others tends to widen. Also, in a growth period, non-rich agents are also improving and, consequently, they are willing to give up some consumption to more sharply reduce the consumption of the rich. During a recession, on the other hand, the wealthy often take a larger relative hit than others (as in the recent Financial Crisis and Great Recession), and income and consumption gaps are closed.

In summary, the authors’ model makes the following predictions:

• Support for populism should be stronger in countries with higher inequality, more financial development, and a more negative current account balance. They find evidence supporting these predictions by analyzing voting data from 29 developed countries. • Populist agents are more averse to risk and are likely to place a large weight on consumption inequality. Their more conservative investment and consumption plans make them less susceptible to the negative effects of autarky and, thus, they are more inclined to favor populist policies. • These agents tend to be less wealthy because of their conservative financial positions and risk aversion. • The model also suggests education as a proxy for risk aversion: less-educated agents tend to benefit less from growth under globalization, and have less to lose from the end of globalization. • The model thus predicts that less-educated, poorer, and anti-elite agents are more likely to vote populist.

Pastor and Veronesi offer one recourse to globalization’s demise: a consumption tax on the purchases of the elites that would serve to subsidize those left behind by globalization. Such a tax could stem a populist tide and keep globalization in place. Other redistributive measures, like income taxes, could slow the impact of globalization but inequality would continue to grow in such an economy and eventually lead to populism.

Globalization is often thought as inexorable and irreversible. However, the authors recount a century of globalization that occurred prior to 1914 that was, in some ways, more expansive than current levels. The onset of World War I, though, and the period extending till after World War II, brought a retrenchment of globalization driven by a number of grievances, including income inequality. Could such a retrenchment happen again? The authors cite literature which suggests that globalization may not be compatible with certain social norms and arrangements that many people find important. Free-flowing goods, services, and migrants may create labor market tensions, but they may also raise other social tensions, including a perceived loss of culture and other norms. Pastor and Veronesi analyze one of those tensions—inequality—and their results suggest that globalization is reversible indeed.

CLOSING TAKEAWAY When inequality becomes large enough, it becomes unsustainable and will set in motion a process to reduce that inequality, according to the model, even at the risk of destroying wealth.

In effect, their model offers the following advice to countries with high inequality and current account deficits, along with sophisticated financial services industries: Get ready—change is coming. As to when such change would occur, the model cannot offer a precise prediction. However, it does suggest that globalized countries that are facing immigration strains, as well as challenges from competing nations, may be particularly vulnerable. When inequality becomes large enough, it becomes unsustainable and will set in motion a process to reduce that inequality, according to the model, even at the risk of destroying wealth.

- Pietro Veronesi

- Lubos Pastor

Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

When discussing the drawbacks and benefits of globalization, essays tend to be on the longer side. The example below is a brief exploration of this complex subject. Learn more in this concise globalization pros and cons essay.

Introduction

- Benefits and Disadvantages of Globalization

Reducing Negative Effects

In today’s world, globalization is a process that affects all aspects of people’s lives. It also has a crucial impact on businesses and governments as it provides opportunities for development while causing significant challenges. This paper discusses the advantages and disadvantages of globalization using evidence from academic sources. The report also suggests how governments and companies may implement to reduce the negative impact of the process.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Globalization

Globalization is a complex concept that can be defined by the process of interaction between organizations, businesses, and people on an international scale, which is driven by international trade. Some people may associate it with uniformity, while others can perceive it as the cause of diversification. The reason for such a difference in public opinion is that globalization has both advantages and disadvantages that should be analyzed.

The most significant positive aspects of globalization include global economic growth, the elimination of barriers between nations, and the establishment of competition between countries, which can potentially lead to a decrease in prices. Globalization supports free trade, creates jobs, and helps societies to become more tolerant towards each other. In addition, this process may increase the speed of financial and commercial operations, as well as reduce the isolation of poor populations (Burlacu, Gutu, & Matei, 2018; Amavilah, Asongu, & Andrés, 2017).

The disadvantages of globalization are that it causes the transfer of jobs from developed to lower-cost countries, a decrease in the national intellectual potential, the exploitation of labor, and a security deficit. Moreover, globalization leads to ecological deficiency (Ramsfield, Bentz, Faccoli, Jactel, & Brockerhoff, 2016). In addition, this process may result in multinational corporations influencing political decisions and offering unfair working conditions to their employees.

Firms and governments can work on eliminating the negative effects of globalization in the following ways. For example, countries should work on microeconomic policies, such as enhancing opportunities for education and career training and establishing less rigid labor markets. In addition, governments can build the necessary institutional infrastructure to initiate economic growth. To solve the problem of poor working conditions, it is vital to establish strict policies regarding minimum wages and the working environment for employees. A decrease in the national intellectual potential may be addressed by offering a broad range of career opportunities with competitive salaries, as well as educating future professionals on how their skills can solve problems on the local level.

Companies, in their turn, may invest in technologies that may lead to more flexible energy infrastructure, lower production costs, and decrease carbon emissions. They can also establish strong corporate cultures to support their workers and provide them with an opportunity to share their ideas and concerns. Such an approach may eliminate employees’ migration to foreign organizations and increase their loyalty to local organizations. It is vital for companies to develop policies aimed at reducing a negative impact on the environment as well by using less destructive manufacturing alternatives and educating their employees on ecology-related issues.

Globalization has a significant impact on companies, governments, and the population. It can be considered beneficial because it helps to eliminate barriers between nations, causes competition between countries, and initiates economic growth. At the same time, globalization may result in a decrease in the national intellectual potential, the exploitation of labor, and ecology deficiency. To address these problems, organizations and governments can develop policies to enhance the population’s education, improve working conditions, and reduce carbon emissions.

Amavilah, V., Asongu, S. A., & Andrés, A. R. (2017). Effects of globalization on peace and stability: Implications for governance and the knowledge economy of African countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 122 (C), 91-103.

Burlacu, S., Gutu, C., & Matei, F. O. (2018). Globalization – Pros and cons. Calitatea , 19 (S1), 122-125.

Ramsfield, T. D., Bentz, B. J., Faccoli, M., Jactel, H., & Brockerhoff, E. G. (2016). Forest health in a changing world: Effects of globalization and climate change on forest insect and pathogen impacts. Forestry , 89 (3), 245-252.

- Globalization of Bollywood and Its Effects on the UAE

- Globalization and Its Impact on the 21st Century Global Marketplace

- Disease Ecology Definition

- How Does Iron Deficiency Affect Pregnancy?

- Ecology: Definition & Ecological Fallacy

- Multinational Corporations Economic Implications

- Globalisation and Labour Market

- Impact of Globalisation on Labour

- The Origins of the Modern World

- Containerized Shipping Influence on World Economies

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, June 9). Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/

"Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay." IvyPanda , 9 June 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay'. 9 June.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/.

1. IvyPanda . "Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Advantages and Disadvantages of Globalization Essay." June 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

We Can’t Undo Globalization, but We Can Improve It

- Gary Pinkus,

- James Manyika,

- Sree Ramaswamy

More trade could provide a lift for U.S. firms.

You can’t go forward by going backward. Take the current debate about trade and globalization, for instance. While the impulse to erect trade barriers is understandable given the pain experienced by workers in a range of industries and communities in recent years, it is not the way to create lasting growth and shared prosperity.

- GP Gary Pinkus is the managing partner for McKinsey & Company in North America and a member of the McKinsey Global Institute Council.

- JM James Manyika is the chairman of the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company.

- SR Sree Ramaswamy is a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute.

Partner Center

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

6 Pros and Cons of Globalization in Business to Consider

- 01 Apr 2021

Throughout history, commerce and business have been limited by certain geographic constraints. In its earliest days, trade happened between neighboring tribes and city-states. As humans domesticated the horse and other animals, the distances they could travel to trade increased. These distances increased further with the development of seafaring capabilities.

Although humans have been using ships for centuries to transport goods, cargo, people, and ideas around the world, it wasn’t until the development of the airplane that the blueprint of a “globalized economy” was laid. This was for a simple reason: You can travel greater distances faster than ever before.

The development of the internet accelerated this process even more, making it easier to communicate and collaborate with others. Today, your international co-worker, business partner, customer, or friend is only a few taps or clicks away.

Globalization has had numerous effects—both positive and negative—on business and society at large. Here’s an overview of the pros and cons of globalization in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Globalization?

Globalization is the increased flow of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas across international boundaries according to the online course Global Business , taught by Harvard Business School Professor Forest Reinhardt.

“We live in an age of globalization,” Reinhardt says in Global Business . “That is, national economies are even more tightly connected with one another than ever before.”

How Globalization Affects Daily Life

Globalization has had a significant impact on various aspects of daily life.

For example, it’s changed the way consumers shop for products and services. Today, 70 percent of Americans shop online. In 2022, there were 268 million digital buyers in the US and by 2025, this number is predicted to reach 285 million.

In addition, the globalized economy has opened up new job markets by making it more feasible to hire overseas workers. This has created a wide range of career opportunities for both job seekers and employers.

The emergence of remote work post-pandemic was also made possible by globalization. According to a survey from WFH Research , only seven percent of paid workdays in the US were remote in 2019. However, this number climbed to 29 percent by January 2024.

Check out the video below to learn more about globalization, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

Advantages of Globalization

1. economic growth.

It’s widely believed that one of the benefits of globalization is greater economic growth for all parties. There are several reasons why this might be the case, including:

- Access to labor: Globalization gives all nations access to a wider labor pool. Developing nations with a shortage of knowledge workers might, for example, “import” labor to kickstart industry. Wealthier nations, on the other hand, might outsource low-skill work to developing nations with a lower cost of living to reduce the cost of goods sold and pass those savings on to the customer.

- Access to jobs: This point is directly related to labor. Through globalization, developing nations often gain access to jobs in the form of work that’s been outsourced by wealthier nations. While there are potential pitfalls to this (see “Disproportionate Growth” below), this work can significantly contribute to the local economy.

- Access to resources: One of the primary reasons nations trade is to gain access to resources they otherwise wouldn’t have. Without this flow of resources across borders, many modern luxuries would be impossible to manufacture or produce. Smartphones, for example, are dependent on rare earth metals found in limited areas around the world.

- The ability for nations to “specialize”: Global and regional cooperation allow nations to heavily lean into their economic strengths, knowing they can trade products for other resources. An example is a tropical nation that specializes in exporting a certain fruit. It’s been shown that when nations specialize in the production of goods or services in which they have an advantage, trade benefits both parties.

2. Increased Global Cooperation

For a globalized economy to exist, nations must be willing to put their differences aside and work together. Therefore, increased globalization has been linked to a reduction—though not an elimination—of conflict.

“Of course, as long as there have been nations, they've been connected with each other through the exchange of lethal force—through war and conquest—and this threat has never gone away,” Reinhardt says in Global Business . “The conventional wisdom has been that the increased intensity of these other flows—goods, services, capital, people, and so on—have reduced the probability that the world's nations will fall back into the catastrophe of war.”

3. Increased Cross-Border Investment

According to the course Global Business , globalization has led to an increase in cross-border investment. At the macroeconomic level, this international investment has been shown to enhance welfare on both sides of the equation.

The country that’s the source of the capital benefits because it can often earn a higher return abroad than domestically. The country that receives the inflow of capital benefits because that capital contributes to investment and, therefore, to productivity. Foreign investment also often comes with, or in the form of, technology, know-how, or access to distribution channels that can help the recipient nation.

Disadvantages of Globalization

1. increased competition.

When viewed as a whole, global free trade is beneficial to the entire system. Individual companies, organizations, and workers can be disadvantaged, however, by global competition. This is similar to how these parties might be disadvantaged by domestic competition: The pool has simply widened.

With this in mind, some firms, industries, and citizens may elect governments to pursue protectionist policies designed to buffer domestic firms or workers from foreign competition. Protectionism often takes the form of tariffs, quotas, or non-tariff barriers, such as quality or sanitation requirements that make it more difficult for a competing nation or business to justify doing business in the country. These efforts can often be detrimental to the overall economic performance of both parties.

“Although we live in an age of globalization, we also seem to be living in an age of anti-globalization,” Reinhardt says in Global Business . “Dissatisfaction with the results of freer trade, concern about foreign investment, and polarized views about immigration all seem to be playing important roles in rich-country politics in the United States and Europe. The threats in Western democracy to the post-war globalist consensus have never been stronger.”

2. Disproportionate Growth

Another issue of globalization is that it can introduce disproportionate growth both between and within nations. These effects must be carefully managed economically and morally.

Within countries, globalization often has the effect of increasing immigration. Macroeconomically, immigration increases gross domestic product (GDP), which can be an economic boon to the recipient nation. Immigration may, however, reduce GDP per capita in the short run if immigrants’ income is lower than the average income of those already living in the country.

Additionally, as with competition, immigration can benefit the country as a whole while imposing costs on people who may want their government to restrict immigration to protect them from those costs. These sentiments are often tied to and motivated—at least in part—by racism and xenophobia.

“Meanwhile, outside the rich world, hundreds of millions of people remain mired in poverty,” Reinhardt says in Global Business. “We don't seem to be able to agree about whether this is because of too much globalization or not enough.”

3. Environmental Concerns

Increased globalization has been linked to various environmental challenges, many of which are serious, including:

- Deforestation and loss of biodiversity caused by economic specialization and infrastructure development

- Greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of pollution caused by increased transportation of goods

- The introduction of potentially invasive species into new environments

While such issues are governed by existing or proposed laws and regulations, businesses have made climate change concerns and sustainability a priority by, for example, embracing the tenets of the triple bottom line and the idea of corporate social responsibility .

Managing the Risks of Globalization

The world is never going to abandon globalization. While it’s true that individual countries and regions put policies and practices in place that limit globalization, such as tariffs, it’s here to stay. The good news is that businesses and professionals willing to prepare for globalization’s challenges by developing strong social impact skills have the potential to benefit immensely.

Whether you’re a business owner, member of executive leadership, or an employee, understanding the impacts of globalization and how to identify its opportunities and risks can help you become more effective in your role and drive value for your organization.