COPD Case Study: Patient Diagnosis and Treatment (2024)

by John Landry, BS, RRT | Updated: May 16, 2024

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease that affects millions of people around the world. It is primarily caused by smoking and is characterized by a persistent obstruction of airflow that worsens over time.

COPD can lead to a range of symptoms, including coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, which can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.

This case study will review the diagnosis and treatment of an adult patient who presented with signs and symptoms of this condition.

25+ RRT Cheat Sheets and Quizzes

Get access to 25+ premium quizzes, mini-courses, and downloadable cheat sheets for FREE.

COPD Clinical Scenario

A 56-year-old male patient is in the ER with increased work of breathing. He felt mildly short of breath after waking this morning but became extremely dyspneic after climbing a few flights of stairs. He is even too short of breath to finish full sentences. His wife is present in the room and revealed that the patient has a history of liver failure, is allergic to penicillin, and has a 15-pack-year smoking history. She also stated that he builds cabinets for a living and is constantly required to work around a lot of fine dust and debris.

Physical Findings

On physical examination, the patient showed the following signs and symptoms:

- His pupils are equal and reactive to light.

- He is alert and oriented.

- He is breathing through pursed lips.

- His trachea is positioned in the midline, and no jugular venous distention is present.

Vital Signs

- Heart rate: 92 beats/min

- Respiratory rate: 22 breaths/min

Chest Assessment

- He has a larger-than-normal anterior-posterior chest diameter.

- He demonstrates bilateral chest expansion.

- He demonstrates a prolonged expiratory phase and diminished breath sounds during auscultation.

- He is showing signs of subcostal retractions.

- Chest palpation reveals no tactile fremitus.

- Chest percussion reveals increased resonance.

- His abdomen is soft and tender.

- No distention is present.

Extremities

- His capillary refill time is two seconds.

- Digital clubbing is present in his fingertips.

- There are no signs of pedal edema.

- His skin appears to have a yellow tint.

Lab and Radiology Results

- ABG results: pH 7.35 mmHg, PaCO2 59 mmHg, HCO3 30 mEq/L, and PaO2 64 mmHg.

- Chest x-ray: Flat diaphragm, increased retrosternal space, dark lung fields, slight hypertrophy of the right ventricle, and a narrow heart.

- Blood work: RBC 6.5 mill/m3, Hb 19 g/100 mL, and Hct 57%.

Based on the information given, the patient likely has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) .

The key findings that point to this diagnosis include:

- Barrel chest

- A long expiratory time

- Diminished breath sounds

- Use of accessory muscles while breathing

- Digital clubbing

- Pursed lip breathing

- History of smoking

- Exposure to dust from work

What Findings are Relevant to the Patient’s COPD Diagnosis?

The patient’s chest x-ray showed classic signs of chronic COPD, which include hyperexpansion, dark lung fields, and a narrow heart.

This patient does not have a history of cor pulmonale ; however, the findings revealed hypertrophy of the right ventricle. This is something that should be further investigated as right-sided heart failure is common in patients with COPD.

The lab values that suggest the patient has COPD include increased RBC, Hct, and Hb levels, which are signs of chronic hypoxemia.

Furthermore, the patient’s ABG results indicate COPD is present because the interpretation reveals compensated respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia. Compensated blood gases indicate an issue that has been present for an extended period of time.

What Tests Could Further Support This Diagnosis?

A series of pulmonary function tests (PFT) would be useful for assessing the patient’s lung volumes and capacities. This would help confirm the diagnosis of COPD and inform you of the severity.

Note: COPD patients typically have an FEV1/FVC ratio of < 70%, with an FEV1 that is < 80%.

The initial treatment for this patient should involve the administration of low-flow oxygen to treat or prevent hypoxemia .

It’s acceptable to start with a nasal cannula at 1-2 L/min. However, it’s often recommended to use an air-entrainment mask on COPD patients in order to provide an exact FiO2.

Either way, you should start with the lowest possible FiO2 that can maintain adequate oxygenation and titrate based on the patient’s response.

Example: Let’s say you start the patient with an FiO2 of 28% via air-entrainment mask but increase it to 32% due to no improvement. The SpO2 originally was 84% but now has decreased to 80%, and his retractions are worsening. This patient is sitting in the tripod position and continues to demonstrate pursed-lip breathing. Another blood gas was collected, and the results show a PaCO2 of 65 mmHg and a PaO2 of 59 mmHg.

What Do You Recommend?

The patient has an increased work of breathing, and their condition is clearly getting worse. The latest ABG results confirmed this with an increased PaCO2 and a PaO2 that is decreasing.

This indicates that the patient needs further assistance with both ventilation and oxygenation .

Note: In general, mechanical ventilation should be avoided in patients with COPD (if possible) because they are often difficult to wean from the machine.

Therefore, at this time, the most appropriate treatment method is noninvasive ventilation (e.g., BiPAP).

Initial BiPAP Settings

In general, the most commonly recommended initial BiPAP settings for an adult patient include this following:

- IPAP: 8–12 cmH2O

- EPAP: 5–8 cmH2O

- Rate: 10–12 breaths/min

- FiO2: Whatever they were previously on

For example, let’s say you initiate BiPAP with an IPAP of 10 cmH20, an EPAP of 5 cmH2O, a rate of 12, and an FiO2 of 32% (since that is what he was previously getting).

After 30 minutes on the machine, the physician requested another ABG to be drawn, which revealed acute respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia.

What Adjustments to BiPAP Settings Would You Recommend?

The latest ABG results indicate that two parameters must be corrected:

- Increased PaCO2

- Decreased PaO2

You can address the PaO2 by increasing either the FiO2 or EPAP setting. EPAP functions as PEEP, which is effective in increasing oxygenation.

The PaCO2 can be lowered by increasing the IPAP setting. By doing so, it helps to increase the patient’s tidal volume, which increased their expired CO2.

Note: In general, when making adjustments to a patient’s BiPAP settings, it’s acceptable to increase the pressure in increments of 2 cmH2O and the FiO2 setting in 5% increments.

Oxygenation

To improve the patient’s oxygenation , you can increase the EPAP setting to 7 cmH2O. This would decrease the pressure support by 2 cmH2O because it’s essentially the difference between the IPAP and EPAP.

Therefore, if you increase the EPAP, you must also increase the IPAP by the same amount to maintain the same pressure support level.

Ventilation

However, this patient also has an increased PaCO2 , which means that you must increase the IPAP setting to blow off more CO2. Therefore, you can adjust the pressure settings on the machine as follows:

- IPAP: 14 cmH2O

- EPAP: 7 cmH2O

After making these changes and performing an assessment , you can see that the patient’s condition is improving.

Two days later, the patient has been successfully weaned off the BiPAP machine and no longer needs oxygen support. He is now ready to be discharged.

The doctor wants you to recommend home therapy and treatment modalities that could benefit this patient.

What Home Therapy Would You Recommend?

You can recommend home oxygen therapy if the patient’s PaO2 drops below 55 mmHg or their SpO2 drops below 88% more than twice in a three-week period.

Remember: You must use a conservative approach when administering oxygen to a patient with COPD.

Pharmacology

You may also consider the following pharmacological agents:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Albuterol)

- Long-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Formoterol)

- Anticholinergic agents (e.g., Ipratropium bromide)

- Inhaled corticosteroids (e.g., Budesonide)

- Methylxanthine agents (e.g., Theophylline)

In addition, education on smoking cessation is also important for patients who smoke. Nicotine replacement therapy may also be indicated.

In some cases, bronchial hygiene therapy should be recommended to help with secretion clearance (e.g., positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy).

It’s also important to instruct the patient to stay active, maintain a healthy diet, avoid infections, and get an annual flu vaccine. Lastly, some COPD patients may benefit from cardiopulmonary rehabilitation .

By taking all of these factors into consideration, you can better manage this patient’s COPD and improve their quality of life.

Final Thoughts

There are two key points to remember when treating a patient with COPD. First, you must always be mindful of the amount of oxygen being delivered to keep the FiO2 as low as possible.

Second, you should use noninvasive ventilation, if possible, before performing intubation and conventional mechanical ventilation . Too much oxygen can knock out the patient’s drive to breathe, and once intubated, these patients can be difficult to wean from the ventilator .

Furthermore, once the patient is ready to be discharged, you must ensure that you are sending them home with the proper medications and home treatments to avoid readmission.

Written by:

John Landry is a registered respiratory therapist from Memphis, TN, and has a bachelor's degree in kinesiology. He enjoys using evidence-based research to help others breathe easier and live a healthier life.

- Faarc, Kacmarek Robert PhD Rrt, et al. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 12th ed., Mosby, 2020.

- Chang, David. Clinical Application of Mechanical Ventilation . 4th ed., Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Rrt, Cairo J. PhD. Pilbeam’s Mechanical Ventilation: Physiological and Clinical Applications. 7th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Gardenhire Douglas EdD Rrt-Nps. Rau’s Respiratory Care Pharmacology. 10th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Heuer Al PhD Mba Rrt Rpft. Wilkins’ Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care. 8th ed., Mosby, 2017.

- Rrt, Des Terry Jardins MEd, and Burton George Md Facp Fccp Faarc. Clinical Manifestations and Assessment of Respiratory Disease. 8th ed., Mosby, 2019.

Recommended Reading

How to prepare for the clinical simulations exam (cse), faqs about the clinical simulation exam (cse), 7+ mistakes to avoid on the clinical simulation exam (cse), copd exacerbation: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epiglottitis scenario: clinical simulation exam (practice problem), guillain barré syndrome case study: clinical simulation scenario, drugs and medications to avoid if you have copd, the pros and cons of the zephyr valve procedure, the 50+ diseases to learn for the clinical sims exam (cse).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Case history

Case history #1.

A 66-year-old man with a smoking history of one pack per day for the past 47 years presents with progressive shortness of breath and chronic cough, productive of yellowish sputum, for the past 2 years. On examination he appears cachectic and in moderate respiratory distress, especially after walking to the examination room, and has pursed-lip breathing. His neck veins are mildly distended. Lung examination reveals a barrel chest and poor air entry bilaterally, with moderate inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. Heart and abdominal examination are within normal limits. Lower extremities exhibit scant pitting edema.

Case history #2

A 56-year-old woman with a history of smoking presents to her primary care physician with shortness of breath and cough for several days. Her symptoms began 3 days ago with rhinorrhea. She reports a chronic morning cough productive of white sputum, which has increased over the past 2 days. She has had similar episodes each winter for the past 4 years. She has smoked 1 to 2 packs of cigarettes per day for 40 years and continues to smoke. She denies hemoptysis, chills, or weight loss and has not received any relief from over-the-counter cough preparations.

Other presentations

Some patients report chest tightness, which often follows exertion and may arise from intercostal muscle contraction. Weight loss, muscle loss, and anorexia are common in patients with severe and very severe COPD. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report Other presentations include fatigue, hemoptysis, cyanosis, and morning headaches secondary to hypercapnia. Chest pain and hemoptysis are uncommon symptoms of COPD and raise the possibility of alternative diagnoses. [2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2019 [internet publication]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

Physical examination may demonstrate hypoxia, use of accessory muscles, paradoxical rib movements, distant heart sounds, lower-extremity edema and hepatomegaly secondary to cor pulmonale, and asterixis secondary to hypercapnia.

Patients may also present with signs and symptoms of COPD complications. These include severe shortness of breath, severely decreased air entry, and chest pain secondary to an acute COPD exacerbation or spontaneous pneumothorax. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report [3] Garcia-Pachon E. Paradoxical movement of the lateral rib margin (Hoover sign) for detecting obstructive airway disease. Chest. 2002 Aug;122(2):651-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12171846?tool=bestpractice.com Patients with COPD often have other comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome and diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, lung cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bronchiectasis, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive impairment. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report [4] Morgan AD, Rothnie KJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of 12 cardiovascular diseases: a population-based study using UK primary care data. Thorax. 2018 Sep;73(9):877-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29438071?tool=bestpractice.com [5] Maltais F, Decramer M, Casaburi R, et al; ATS/ERS Ad Hoc Committee on Limb Muscle Dysfunction in COPD. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 May 1;189(9):e15-62. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24787074?tool=bestpractice.com

One UK study found that 14.5% of patients with COPD had a concomitant diagnosis of asthma, whereas a global meta-analysis estimated the pooled prevalence of asthma in patients with COPD to be 29.6% (range: 12.6% to 55.5%). [6] Nissen F, Morales DR, Mullerova H, et al. Concomitant diagnosis of asthma and COPD: a quantitative study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 Nov;68(676):e775-82. https://bjgp.org/content/68/676/e775 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30249612?tool=bestpractice.com [7] Hosseini M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, et al. Global prevalence of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019 Oct 23;20(1):229. https://respiratory-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-019-1198-4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31647021?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice

Log in to access all of bmj best practice, help us improve bmj best practice.

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

- LOGIN / FREE TRIAL

‘Racism absolutely must not be tolerated’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: COPD

Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study

04 May, 2020

This case study explains the symptoms, causes, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This article uses a case study to discuss the symptoms, causes and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, describing the patient’s associated pathophysiology. Diagnosis involves spirometry testing to measure the volume of air that can be exhaled; it is often performed after administering a short-acting beta-agonist. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease involves lifestyle interventions – vaccinations, smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation – pharmacological interventions and self-management.

Citation: Price D, Williams N (2020) Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study. Nursing Times [online]; 116: 6, 36-38.

Authors: Debbie Price is lead practice nurse, Llandrindod Wells Medical Practice; Nikki Williams is associate professor of respiratory and sleep physiology, Swansea University.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is used to describe a number of conditions, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although common, preventable and treatable, COPD was projected to become the third leading cause of death globally by 2020 (Lozano et al, 2012). In the UK in 2012, approximately 30,000 people died of COPD – 5.3% of the total number of deaths. By 2016, information published by the World Health Organization indicated that Lozano et al (2012)’s projection had already come true.

People with COPD experience persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that can be due to airway or alveolar abnormalities, caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases, commonly from tobacco smoking. The projected level of disease burden poses a major public-health challenge and primary care nurses can be pivotal in the early identification, assessment and management of COPD (Hooper et al, 2012).

Grace Parker (the patient’s name has been changed) attends a nurse-led COPD clinic for routine reviews. A widowed, 60-year-old, retired post office clerk, her main complaint is breathlessness after moderate exertion. She scored 3 on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (Fletcher et al, 1959), indicating she is unable to walk more than 100 yards without stopping due to breathlessness. Ms Parker also has a cough that produces yellow sputum (particularly in the mornings) and an intermittent wheeze. Her symptoms have worsened over the last six months. She feels anxious leaving the house alone because of her breathlessness and reduced exercise tolerance, and scored 26 on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT, catestonline.org), indicating a high level of impact.

Ms Parker smokes 10 cigarettes a day and has a pack-year score of 29. She has not experienced any haemoptysis (coughing up blood) or chest pain, and her weight is stable; a body mass index of 40kg/m 2 means she is classified as obese. She has had three exacerbations of COPD in the previous 12 months, each managed in the community with antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol.

Ms Parker was diagnosed with COPD five years ago. Using Epstein et al’s (2008) guidelines, a nurse took a history from her, which provided 80% of the information needed for a COPD diagnosis; it was then confirmed following spirometry testing as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) guidance.

The nurse used the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model, as it combines the pathological description of COPD with the patient’s subjective experience of the illness (Silverman et al, 2013). Effective communication skills are essential in building a trusting therapeutic relationship, as the quality of the relationship between Ms Parker and the nurse will have a direct impact on the effectiveness of clinical outcomes (Fawcett and Rhynas, 2012).

In a national clinical audit report, Baxter et al (2016) identified inaccurate history taking and inadequately performed spirometry as important factors in the inaccurate diagnosis of COPD on general practice COPD registers; only 52.1% of patients included in the report had received quality-assured spirometry.

Pathophysiology of COPD

Knowing the pathophysiology of COPD allowed the nurse to recognise and understand the physical symptoms and provide effective care (Mitchell, 2015). Continued exposure to tobacco smoke is the likely cause of the damage to Ms Parker’s small airways, causing her cough and increased sputum production. She could also have chronic inflammation, resulting in airway smooth-muscle contraction, sluggish ciliary movement, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting goblet cells, as well as release of inflammatory mediators (Mitchell, 2015).

Ms Parker may also have emphysema, which leads to damaged parenchyma (alveoli and structures involved in gas exchange) and loss of alveolar attachments (elastic connective fibres). This causes gas trapping, dynamic hyperinflation, decreased expiratory flow rates and airway collapse, particularly during expiration (Kaufman, 2013). Ms Parker also displayed pursed-lip breathing; this is a technique used to lengthen the expiratory time and improve gaseous exchange, and is a sign of dynamic hyperinflation (Douglas et al, 2013).

In a healthy lung, the destruction and repair of alveolar tissue depends on proteases and antiproteases, mainly released by neutrophils and macrophages. Inhaling cigarette smoke disrupts the usually delicately balanced activity of these enzymes, resulting in the parenchymal damage and small airways (with a lumen of <2mm in diameter) airways disease that is characteristic of emphysema. The severity of parenchymal damage or small airways disease varies, with no pattern related to disease progression (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2018).

Ms Parker also had a wheeze, heard through a stethoscope as a continuous whistling sound, which arises from turbulent airflow through constricted airway smooth muscle, a process noted by Mitchell (2015). The wheeze, her 29 pack-year score, exertional breathlessness, cough, sputum production and tiredness, and the findings from her physical examination, were consistent with a diagnosis of COPD (GOLD, 2018; NICE, 2018).

Spirometry is a tool used to identify airflow obstruction but does not identify the cause. Commonly measured parameters are:

- Forced expiratory volume – the volume of air that can be exhaled – in one second (FEV1), starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres);

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) – the total volume of air that can be forcibly exhaled – at timed intervals, starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres).

Calculating the FEV1 as a percentage of the FVC gives the forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC). This provides an index of airflow obstruction; the lower the ratio, the greater the degree of obstruction. In the absence of respiratory disease, FEV1 should be ≥70% of FVC. An FEV1/FVC of <70% is commonly used to denote airflow obstruction (Moore, 2012).

As they are time dependent, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC are reduced in diseases that cause airways to narrow and expiration to slow. FVC, however, is not time dependent: with enough expiratory time, a person can usually exhale to their full FVC. Lung function parameters vary depending on age, height, gender and ethnicity, so the degree of FEV1 and FVC impairment is calculated by comparing a person’s recorded values with predicted values. A recorded value of >80% of the predicted value has been considered ‘normal’ for spirometry parameters but the lower limit of normal – equal to the fifth percentile of a healthy, non-smoking population – based on more robust statistical models is increasingly being used (Cooper et al, 2017).

A reversibility test involves performing spirometry before and after administering a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) such as salbutamol; the test is used to distinguish between reversible and fixed airflow obstruction. For symptomatic asthma, airflow obstruction due to airway smooth-muscle contraction is reversible: administering a SABA results in smooth-muscle relaxation and improved airflow (Lumb, 2016). However, COPD is associated with fixed airflow obstruction, resulting from neutrophil-driven inflammatory changes, excess mucus secretion and disrupted alveolar attachments, as opposed to airway smooth-muscle contraction.

Administering a SABA for COPD does not usually produce bronchodilation to the extent seen in someone with asthma: a person with asthma may demonstrate significant improvement in FEV1 (of >400ml) after having a SABA, but this may not change in someone with COPD (NICE, 2018). However, a negative response does not rule out therapeutic benefit from long-term SABA use (Marín et al, 2014).

NICE (2018) and GOLD (2018) guidelines advocate performing spirometry after administering a bronchodilator to diagnose COPD. Both suggest a FEV1/FVC of <70% in a person with respiratory symptoms supports a diagnosis of COPD, and both grade the severity of the condition using the predicted FEV1. Ms Parker’s spirometry results showed an FEV1/FVC of 56% and a predicted FEV1 of 57%, with no significant improvement in these values with a reversibility test.

GOLD (2018) guidance is widely accepted and used internationally. However, it was developed by medical practitioners with a medicalised approach, so there is potential for a bias towards pharmacological management of COPD. NICE (2018) guidance may be more useful for practice nurses, as it was developed by a multidisciplinary team using evidence from systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, providing a holistic approach. NICE guidance may be outdated on publication, but regular reviews are performed and published online.

NHS England (2016) holds a national register of all health professionals certified in spirometry. It was set up to raise spirometry standards across the country.

Assessment and management

The goals of assessing and managing Ms Parker’s COPD are to:

- Review and determine the level of airflow obstruction;

- Assess the disease’s impact on her life;

- Risk assess future disease progression and exacerbations;

- Recommend pharmacological and therapeutic management.

GOLD’s (2018) ABCD assessment tool (Fig 1) grades COPD severity using spirometry results, number of exacerbations, CAT score and mMRC score, and can be used to support evidence-based pharmacological management of COPD.

When Ms Parker was diagnosed, her predicted FEV1 of 57% categorised her as GOLD grade 2, and her mMRC score, CAT score and exacerbation history placed her in group D. The mMRC scale only measures breathlessness, but the CAT also assesses the impact COPD has on her life, meaning consecutive CAT scores can be compared, providing valuable information for follow-up and management (Zhao, et al, 2014).

After assessing the level of disease burden, Ms Parker was then provided with education for self-management and lifestyle interventions.

Lifestyle interventions

Smoking cessation.

Cessation of smoking alongside support and pharmacotherapy is the second-most cost-effective intervention for COPD, when compared with most other pharmacological interventions (BTS and PCRS UK, 2012). Smoking cessation:

- Slows the progression of COPD;

- Improves lung function;

- Improves survival rates;

- Reduces the risk of lung cancer;

- Reduces the risk of coronary heart disease risk (Qureshi et al, 2014).

Ms Parker accepted a referral to an All Wales Smoking Cessation Service adviser based at her GP surgery. The adviser used the internationally accepted ‘five As’ approach:

- Ask – record the number of cigarettes the individual smokes per day or week, and the year they started smoking;

- Advise – urge them to quit. Advice should be clear and personalised;

- Assess – determine their willingness and confidence to attempt to quit. Note the state of change;

- Assist – help them to quit. Provide behavioural support and recommend or prescribe pharmacological aids. If they are not ready to quit, promote motivation for a future attempt;

- Arrange – book a follow-up appointment within one week or, if appropriate, refer them to a specialist cessation service for intensive support. Document the intervention.

NICE (2013) guidance recommends that this be used at every opportunity. Stead et al (2016) suggested that a combination of counselling and pharmacotherapy have proven to be the most effective strategy.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Ms Parker’s positive response to smoking cessation provided an ideal opportunity to offer her pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) – as indicated by Johnson et al (2014), changing one behaviour significantly increases a person’s chance of changing another.

PR – a supervised programme including exercise training, health education and breathing techniques – is an evidence-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary intervention that:

- Improves exercise tolerance;

- Reduces dyspnoea;

- Promotes weight loss (Bolton et al, 2013).

These improvements often lead to an improved quality of life (Sciriha et al, 2015).

Most relevant for Ms Parker, PR has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, which are linked to an increased risk of exacerbations and poorer health status (Miller and Davenport, 2015). People most at risk of future exacerbations are those who already experience them (Agusti et al, 2010), as in Ms Parker’s case. Patients who have frequent exacerbations have a lower quality of life, quicker progression of disease, reduced mobility and more-rapid decline in lung function than those who do not (Donaldson et al, 2002).

“COPD is a major public-health challenge; nurses can be pivotal in early identification, assessment and management”

Pharmacological interventions

Ms Parker has been prescribed inhaled salbutamol as required; this is a SABA that mediates the increase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in airway smooth-muscle cells, leading to muscle relaxation and bronchodilation. SABAs facilitate lung emptying by dilatating the small airways, reversing dynamic hyperinflation of the lungs (Thomas et al, 2013). Ms Parker also uses a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) inhaler, which works by blocking the bronchoconstrictor effects of acetylcholine on M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle; release of acetylcholine by the parasympathetic nerves in the airways results in increased airway tone with reduced diameter.

At a routine review, Ms Parker admitted to only using the SABA and LAMA inhalers, despite also being prescribed a combined inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 -agonist (ICS/LABA) inhaler. She was unaware that ICS/LABA inhalers are preferred over SABA inhalers, as they:

- Last for 12 hours;

- Improve the symptoms of breathlessness;

- Increase exercise tolerance;

- Can reduce the frequency of exacerbations (Agusti et al, 2010).

However, moderate-quality evidence shows that ICS/LABA combinations, particularly fluticasone, cause an increased risk of pneumonia (Suissa et al, 2013; Nannini et al, 2007). Inhaler choice should, therefore, be individualised, based on symptoms, delivery technique, patient education and compliance.

It is essential to teach and assess inhaler technique at every review (NICE, 2011). Ms Parker uses both a metered-dose inhaler and a dry-powder inhaler; an in-check device is used to assess her inspiratory effort, as different inhaler types require different inhalation speeds. Braido et al (2016) estimated that 50% of patients have poor inhaler technique, which may be due to health professionals lacking the confidence and capability to teach and assess their use.

Patients may also not have the dexterity, capacity to learn or vision required to use the inhaler. Online resources are available from, for example, RightBreathe (rightbreathe.com), British Lung Foundation (blf.org.uk). Ms Parker’s adherence could be improved through once-daily inhalers, as indicated by results from a study by Lipson et al (2017). Any change in her inhaler would be monitored as per local policy.

Vaccinations

Ms Parker keeps up to date with her seasonal influenza and pneumococcus vaccinations. This is in line with the low-cost, highest-benefit strategy identified by the British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society UK’s (2012) study, which was conducted to inform interventions for patients with COPD and their relative quality-adjusted life years. Influenza vaccinations have been shown to decrease the risk of lower respiratory tract infections and concurrent COPD exacerbations (Walters et al, 2017; Department of Health, 2011; Poole et al, 2006).

Self-management

Ms Parker was given a self-management plan that included:

- Information on how to monitor her symptoms;

- A rescue pack of antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol;

- A traffic-light system demonstrating when, and how, to commence treatment or seek medical help.

Self-management plans and rescue packs have been shown to reduce symptoms of an exacerbation (Baxter et al, 2016), allowing patients to be cared for in the community rather than in a hospital setting and increasing patient satisfaction (Fletcher and Dahl, 2013).

Improving Ms Parker’s adherence to once-daily inhalers and supporting her to self-manage and make the necessary lifestyle changes, should improve her symptoms and result in fewer exacerbations.

The earlier a diagnosis of COPD is made, the greater the chances of reducing lung damage through interventions such as smoking cessation, lifestyle modifications and treatment, if required (Price et al, 2011).

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive respiratory condition, projected to become the third leading cause of death globally

- Diagnosis involves taking a patient history and performing spirometry testing

- Spirometry identifies airflow obstruction by measuring the volume of air that can be exhaled

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is managed with lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, as well as self-management

Related files

200506 diagnosis and management of copd – a case study.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Nurse-led cognitive behavioural therapy for respiratory patients

Anxiety and depression are common comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This…

Issues of home-based non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation is increasingly used to manage patients with COPD at home,…

Improving outcomes with online COPD self-care

An innovative approach to the self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is…

An audit of care provided to patients with COPD

Nationwide audit of COPD care reveals many aspects of provision have improved,…

Have your say

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases & Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Clinical Trials

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Ask a Scientist

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- Education and Awareness

- < Back To COPD: Learn More Breathe Better®

COPD Digital Resource Toolkit for Health Professionals

Use the COPD resources below to help patients and their families and caregivers learn more about COPD including risk factors, signs and symptoms, treatment options, and more.

Healthcare providers play an important role in the diagnosis and management of COPD. Often a visit to a physician's office is not triggered by breathing issues and patients do not always fully report their symptoms.

Use the resources below and these COPD educational videos to help patients and their families and caregivers.

Community Presentation

Download the presentation below to share valuable COPD information with patients and others in your community.

What You Should Know About COPD - Presentation for Community Outreach

Print or Order these Publications

Continuing Medical Education (CME) Resources

Check back periodically for free CME opportunities.

Listen to the following CME podcast episodes produced by Breathe Better Network partner, Pri-Med in partnership with Learn More Breathe Better. 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ is available for each episode when accessed directly through Pri-Med. Or, listen to the episodes on Apple Music, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or wherever else you may listen to podcasts.

CME credit for the following podcast episodes is available until May 31, 2025:

- Identifying and Testing for COPD in the Primary Care Setting

- COPD Treatment for Primary Care Providers

- Patient Case Studies: COPD Screening, PRISm, and AAT Deficiency

- Pulmonary Fibrosis: What Primary Care Providers Need to Know

- Cystic Fibrosis: The Primary Care Provider’s Role in Case Finding and Referral

- Sarcoidosis in the Lungs: What Primary Care Providers Should Know

COPD National Action Plan Resources

Talk about the COPD National Action Plan at meetings, conferences, or during webinars. Feel free to use the below PowerPoint in its entirety or pick and choose the slides that are most relevant to your audience.

COPD National Action Plan Slides PPT version

COPD National Action Plan Slides PDF version

COPD Data on Perceptions and Awareness

The Learn More Breathe Better program tracks and gathers insights into consumer and health care provider attitudes and behaviors related to COPD. This includes awareness and knowledge about the disease, experience with symptoms, patient communication and information, and physicians' approaches to COPD treatment and management.

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

101 templates

39 templates

art portfolio

100 templates

24 templates

43 templates

9 templates

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

It seems that you like this template, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd) presentation, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, also known as COPD, encompasses a group of diseases that cause problems with breathing. In the United States alone it affects about 16 million people. If you are preparing a presentation about it you can use this Slidesgo proposal. It has a simple style, with a white background and light blue waves and lines, which convey elegance and serenity. In addition, we have included a multitude of resources that you can edit to convey your information, such as graphics, map, infographics, etc.

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 26 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the free resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Register for free and start downloading now

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Create your presentation Create personalized presentation content

Writing tone, number of slides.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

- Health Science

Major Case Study: COPD PowerPoint Presentation

Related documents.

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Major Case Study: COPD

Feb 20, 2012

400 likes | 906 Views

Major Case Study: COPD. Emily Brantley Dietetic Intern Andrews University. Patient’s Initials: NM Primary Problem & other medical conditions: COPD , DM, IBS, Pneumonia, IgA deficiency Height: 160.02 Weight: 107.2 Age: 62 years old Sex: Female. Introduction. Introduction.

Share Presentation

- medical conditions

- risk factor

- present medical status

- depakote er valproic acid

Presentation Transcript

Major Case Study: COPD Emily Brantley Dietetic Intern Andrews University

Patient’s Initials: NM Primary Problem & other medical conditions: COPD, DM, IBS, Pneumonia, IgA deficiency Height: 160.02 Weight: 107.2 Age: 62 years old Sex: Female Introduction

Introduction • Reason patient was chosen for case study: • NM was chosen because of the multiple complications that she faces. • Date the study began and ended • December 5, 2013 – December 6, 2013 • Focus of this study: • Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) • NM has other comorbidities, however, NM is most often admitted to the hospital for exacerbation of COPD.

Social History • NM is a Christian woman who lives at home with her husband and pet parakeet. • She is currently on Medicare. • Retired RN. • Her three children are all adults and live within the region. • NM is a former smoker • Medical records indicate that she does not smoke or drink alcohol anymore.

Normal Anatomy and Physiology of Applicable Body Functions • COPD is characterized by slow, progressive obstruction of the airways. • There are two physical conditions that make up COPD. • Emphysema • Characterized by abnormal, permanent enlargement and destruction of the alveoli • Chronic Bronchitis • A progressive cough with inflammation of bronchi and other lung changes • Frequently, both illnesses coexist as part of this disorder. • In both cases, the disease limits the airflow 1&2

Past Medical History

Past Medical History • NM initially received the diagnosis of COPD in 1997. • American Thoracic Society states comorbidities such as cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and psychological disorders are commonly reported in patients with COPD, but with great variability in reported prevalence.

Past Medical History • Pneumonia • NM has been hospitalized six times within the past year for episodes of pneumonia. • COPD is more frequently associated with pneumonia. • Corticosteroids are standard of care for acute exacerbations of COPD, but their role in the management of patients with COPD with pneumonia is less defined. 3 • Diabetes Mellitus. • The evidence for an interaction between diabetes and COPD is supported by studies that demonstrate reduced lung function as a risk factor for the development of diabetes. • Smoking has been established as a risk factor for both COPD and Diabetes Mellitus. 3 • Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). • An increased prevalence of GERD has been reported in patients with COPD. A study of 421 patients with severe COPD using 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring showed that 62% had pathological GERD, and 58% of the patients reported no symptoms of GERD.3

Past Medical History • Bronchial Asthma • Adrenal Insufficiency • Coronary Artery Disease • Trachaeomalacia • Addison’s disease • Hypothyroidism • Bipolar Disorder • Irritable Bowel syndrome • Vascular stent placement • Hyperlipidemia • Hyperthyroidism • Anemia

Present Medical Status and Treatment

Theoretical Discussion of Disease Condition • COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in America. COPD is also more prevalent in women.3&4 • The primary risk factor in the development of COPD is smoking. • Beyond the cessation of smoking, it has been shown that the inflammatory stress continues to damage the lung tissue. • Other risk factors include air pollution, secondhand smoke, history of childhood infections, and occupational exposure to certain industrial pollutants.

Theoretical Discussion of Disease Condition • Although normal lung function gradually declines with age, individuals who are smokers have a more rapid decline—twice the rate of nonsmokers. • Low body weight has also been shown to be a risk factor for the development of COPD even after adjusting for other potential risk factors including smoking and age.2 • Malnourished patients with COPD experience worsened respiratory muscle strength, decreased ventilator drive and response to hypoxia, and altered immune function.1,5&6

Usual Treatment of the Condition • An early and accurate diagnosis of COPD is the key to treatment. • Quitting smoking is the single most important thing that can be done to help treat COPD.7 • The usual treatment of COPD is composed of four main goals for effective management: • 1. Assess and monitor the disease • 2. Reduce risk factors • 3. Maintain stable COPD and respiratory status • 4. Manage any exacerbations • Once the disease progresses, rehabilitation programs along with oxygen therapy are used as treatment. • Medications include bronchodilators, glucocorticosteroids, mucolytic agents, and antibiotics to treat infections. • In cases where COPD may be advanced, there is an option for surgical intervention, such as a lung transplant.1

Patient’s Symptoms upon Admission Leading to Present Diagnosis • NM was admitted with shortness of breath, cough, diarrhea, hypokalemia and fever. • She revealed that one of the possible causes of her diarrhea may be the fact that she had “been around a couple of people with Clostridium Difficile.” • NM also showed symptoms of hyperlipidemia and hypertension • High blood pressure is a complication of COPD.6 • Hyperglycemia is a side effect of steroid therapy for COPD. • Steroids can increase the blood sugar making diabetes harder to control.8

Laboratory Findings and Interpretation

Current Medications • Depakote ER (Valproic Acid) • Lexapro (Escitaloprem) • Florinef (Fludrocortison Acitate) • Fluticasone- salmeterol • Metronidazole Flagyl • Insulin Lispro (Humalog) • Misoprostal (Cytotec) • Monelukast (Singulair) • Pantaprazole (Protonix oral) • Potassium Chloride • RisperiDONE (RisperDAL) • Rosuvastatin (Crestor) • NaCl • Tolterodine • Voriconazole

Observable Physical and Psychological Changes in Patient • NM physically looked well nourished. • She did not appear to have difficulty breathing until after she spoke for a long period of time. • She did have a severe cough that she tried to conceal. • NM was a very agreeable patient for both psychological interviews. • In spite of her COPD diagnosis and all of the multiple medical comorbidities that NM faced, she still presented a positive attitude and spoke openly about her faith.

Treatment • NM received a chest x ray that revealed consolidation in the left lung and midline lung level. • Once this was identified, she was admitted to the hospital from the Emergency room for treatment. • She was started on IV steroids, IV antibiotics, flagyl and nebulizers around the clock to see how she progressed.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Nutrition History • Beginning in March 2012, NM began intentionally losing weight by following a PCP prescribed commercial diet known as Optifast. • Optifast offers shakes, protein bars and soups. • With this regimen, NM has lost 70 pounds since March 2012. • At home, NM usually sticks to her Optifast food items for breakfast, lunch and snacks between meals. • For dinner, she shares a meal with her husband. • He is a professional chef who is control of purchasing groceries and prepares dinner most nights.

Analysis of Previous Diet: 24 hour recall

Current Prescribed Diet • NM was on steroid therapy to treat her COPD. • Because of the steroid therapy, NM was admitted with consistently high blood glucose levels. • For this reason, doctor’s orders were given for an Average Diabetic Diet for the duration of her stay at Winter Park Memorial Hospital. • An Average Diabetic Diet provides a consistent 60-75 grams of carbohydrates for each meal. • NM’s diet order remained the same for her entire stay.

Objectives of Dietary Treatment • The objective of the Average Diabetic diet is to maintain NM’s blood sugars within normal limits or as close as possible to normal levels. • Steroid therapy that NM was undergoing to treat her COPD helps keep blood sugars high • Finger-stick blood sugar levels referred to as “Accuchecks” ranged inconsistently from 130 to 289 as seen on the lab values table above.

Patient’s Physical and Psychological Response to Diet • At home, NM followed an eating pattern similar to that of the Average Diabetic Diet but with the addition of snacks in between meals. • She denied facing vomiting or constipation while on this diet. • She did admit to experiencing diarrhea and nausea upon admission to the hospital. • As previously mentioned, NM believed she was exposed to Clostridium Difficile, to which she attributes to the cause of having diarrhea.

List nutrition-related problems with supporting evidence • COPD: Increased energy expenditure related to increased energy requirements during COPD exacerbation as evidenced by measured resting energy expenditure greater than predicted needs.

Evaluation of Present Nutritional Status • According to the diet analysis table, NM was meeting her increased caloric needs for COPD. • Her diarrhea subsided by day two of hospitalization. • Per lab values as those noted above in the table, there did not appear to be any indication of dehydration.

Calorie and Protein Guidelines • Nutritional needs are often increased in COPD due to the increased work of breathing. • Optimal nutritional status plays an important role in maintaining the integrity of the respiratory system and in allowing maximal participation in daily living.1 • Caloric requirements for COPD individually determined based on: • Patient age, weight and gender, the extent of protein energy malnutrition loss of lean body mass, current medications and other acute or chronic medical conditions. • The Mifflin St. Jeor equation may underestimate the caloric requirements of patient’s with COPD because of the caloric increase from metabolically active tissue. • To compensate for this underestimation, a stress activity factor may be added according to the degree of stress. • In most cases the total calorie intake of the COPD patient is more important than the source from calories.

Calorie and Protein Guidelines • For maintenance 1.33 x REE or 25/35 calories per kilogram is appropriate for the needs of the COPD patient. • Protein is recommended at 1.0-1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight for maintenance.1 • Below is a chart of how NM’s needs were clinically calculated during her hospital admission on December 5th through the 6th.

Need for Alternative Feeding Methods and the Patient’s Nutrition Education Process • NM was in fact meeting the additional needs required for COPD, I do not believe that there was any need for alternative feedings such as tube feeding. • Moreover, in explaining the prescribed diabetic diet to NM, no type of barrier to learning was identified.

Prognosis • NM expressed her motivation to continue to follow a diet similar to that of the Average Diabetic Diet upon her return home as long as her increased COPD needs were met. • She was aware of the effects of steroid therapy on her blood sugar levels. • NM clearly verbalized her understanding on the use of steroids, their effects on increasing blood sugar levels and the importance of meal planning especially around carbohydrates. • This was more of a motivating factor for her to continue monitoring her diet on discharge.

Summary • From this study, I learned how very serious COPD is. • It was once explained to me some time ago that COPD was like a gradual suffocating in a pillow. • Seeing NM experiencing shortness of breath during the interviews or when speaking to me during the interviews made me realize that even the slightest amount of energy requires oxygen. • Imagine not being able to breathe to conduct the simplest activities of daily living! • In addition to other medical issues as NM had, it made me realize how important nutrition energy is needed for healing.

Thank You!

References • Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, Raymond JL. Krause’s Food, Nutrition and Diet Therapy, 13th Edition, Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2012 • Nelms M, Sucher KP, Lacey K, Roth SL. Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology, 2nd Edition. Cengage Learning, Inc: 2010. • Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Make BJ. Comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of the American Thoracic Society. 2008 May 1; 5(4): 549-555 • Centers for Disease Control. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Data and Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/copd/data.htm. Accessed December 29, 2013. • American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Disease-Related Malnutrition and Enteral Nutrition Therapy. Available at: http://www.nutritioncare.org/index.aspx?id=5696. Accessed January 5, 2014. • Mayo Clinic. Disease and Conditions: COPD. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/seo/basics/symptoms/con-20032017. Accessed January 8, 2014. • National Institutes of Health: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. How Is COPD Treated? Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/copd/treatment.html. Accessed January 8, 2014. • British Lung Foundation. Steroids. Available at: http://www.blf.org.uk/Page/Steroids. Accessed December 29, 2013. • MedlinePlus: A service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine From the National Institutes of Health National Institutes of Health. Drugs and Supplements. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/drug_Ca.html • U.S. National Library of Medicine. Drug Information from the National Library of Medicine. Available at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/learn-about-drugs.html. Accessed January 8, 2014. • Optifast. Product Information. Available at: http://www.optifast.com/Pages/index.aspx. Accessed January 7, 2014

References: Images • http://sciencelife.uchospitals.edu/2013/05/07/qa-dr-christopher-wigfield-on-the-future-of-lung-transplantation/ • http://www.guidantwealth.com/Goal-early-retirement.html • http://www.recessionista.com • http://www.everydayhealth.com • https://www.spiriva.com/?sc=SPRACQWEBPGOGBS1105034&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_term=spiriva&utm_campaign=Branded&MTD=2&ENG=1 • http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/imagepages/19376.htm • http://www.cdc.gov/copd/data.htm • http://www.www.kingcounty.gov • http://www.www.anactivelife.com • http://www.optifast.com/Pages/index.aspx • www.fairmed.at • www. Eatright.org • http://www.alltheweigh.com

- More by User

“This is a Test. This is Only a Test!”

“This is a Test. This is Only a Test!”. * Overcoming Test Anxiety* Presented by: Brenda Peedin Tutor Coordinator Student Support Services TRiO Johnston Community College. Who is likely to get test anxiety?. Those people who worry a lot Perfectionists

1.5k views • 10 slides

Software Testing

Test Lifecycle and Test Process. Software Testing. Test Level Process. Test Planning and Control. Test Planning and Control. Test Analysis and Design Review test basis Identify test condition Decide test design tech. Evaluate testability Setup Environment.

1.74k views • 124 slides

3D Test Issues

Bill Eklow October 26, 2011. 3D Test Issues . 3D Test Challenges – Key Areas (http://www.itrs.net/) . Defects TSV’s Test access Test Flows/Test Scheduling Heterogeneous Die Debug Power. 3D Sources of defects (known good -> unknown). Thermal (Reliability, Performance)

1.59k views • 14 slides

Test and Test Equipment December 2012 Hsin -Chu , Taiwan

Test and Test Equipment December 2012 Hsin -Chu , Taiwan. Roger Barth. Chapter Content. Test Drivers & Challenges Test & Yield Learning Test Cost Concurrent/Adaptive Test 3D Device Test Test Technology Requirements Test parallelism DFx

5.46k views • 18 slides

Who wants to be a Millionaire?

Who wants to be a Millionaire?. Hosted by Miss Cook. The Prizes. 8 - Doughnuts 9 – Formula Card on Test 10 – 2% Test E.C. 11 – 3 % Test E.C. 12 – 5% Test E.C. 13 – Group Test 14 – 100% on Test. 1 – A “good job!” 2 – A “Terrific!” 3 – A “Fantastic!” 4 – Calculator on Test

796 views • 18 slides

Test Preparation, Test Taking Strategies, and Test Anxiety

Test Preparation, Test Taking Strategies, and Test Anxiety. PASS 0900. Before the Test. Spread studying over several days Ask instructor what to expect Make a list of what is to be studied for the test Use review material in book Review by yourself or with other students

860 views • 13 slides

Test Automation Tools: QF-Test and Selenium

Test Automation Tools: QF-Test and Selenium. by P. Kratzer / P.Sivera Software Engineer ESO. Introduction to QF-Test. QF-Test is a GUI test tool for Java and web apps developed by German company Quality First Software GmbH (QFS) Vendor web site: http://www.qfs.de/en/

898 views • 19 slides

System Test Specification

STV. TSPC. System Test Specification. Location of the Test Specification Sources of Test Cases Test Cases from the Requirements Specs Test Cases from the Design Documentation Test Cases from the Usage Profile Test Case Selection Criteria Black-Box Test Methods Data Flow Analysis

746 views • 26 slides

TDC ( Test Description Code)

TDC ( Test Description Code). CSH version 1.4 - duration 45 min. TDC (Test Description Code) Overview. What is TDC? User documentation Test tool chain Features Test Structure Test Case definition Example of converted test cases Pratical Requirements

552 views • 15 slides

Engine Condition Diagnosis

Engine Condition Diagnosis. Compression test Cranking vacuum test Cylinder leakage test Dynamic compression test Idle vacuum test. Paper test Power balance test Restricted exhaust Running compression test Vacuum test Wet compression test. KEY TERMS.

2.25k views • 56 slides

Chi-square test or c 2 test

Chi-square test or c 2 test. Chi-square test. Used to test the counts of categorical data Three types Goodness of fit Independence Homogeneity. c 2 distribution –. df=3. df=5. df=10. c 2 distribution. Different df have different curves Skewed right Only positive values

1.3k views • 25 slides

Test. Test. Test. Test. Test. 100. 100. 100. 100. 100. 200. 200. 200. 200. 200. 300. 300. 300. 300. 300. 400. 400. 400. 400. 400. 500. 500. 500. 500. 500. May kill fish or other organisms. What is acid rain?. Used to preserve food. What is sodium nitrate?.

897 views • 51 slides

Test del Software, con elementi di Verifica e Validazione, Qualità del Prodotto Software

Test del Software, con elementi di Verifica e Validazione, Qualità del Prodotto Software. G. Berio. Argomenti Introduttivi. Definizione(i) di test Test d’accettazione e test dei difetti Test delle unità e test in the large (test d’integrazione e test di sistema) (strategie di test)

4.87k views • 90 slides

Test of Significance

Test of Significance. Presenter: Vikash R Keshri Moderator: Mr. M. S. Bharambe. Outline. Introduction : Important Terminologies. Test of Significance : Z test. t test. F test. Chi Square test. Fisher’s Exact test. Significant test for correlation Coefficient.

3.71k views • 54 slides

System Test Tools

SYST. TOOL. System Test Tools. Test atorTool Categories Tools for SystemTest Management Tools for System Test Operations Test Plan Editing Tool (TESTPLAN) Test Case Specification Tool (TESTSPEC) Test Documentation Tool (TESTDOC) Test Data Generator (TESTDATA)

965 views • 26 slides

Lesson 7. How do you conduct a radon test?. Prepare for the test. Determine timing of the test How long test will last Appropriate weather conditions during test period Convenience of owner or resident Determine the location of the test Consider how to prevent or detect interference.

2.82k views • 40 slides

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

Clinical and radiological features associated with rupture of pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm: a retrospective study

- Min Liu 1 na1 ,

- Jixiang Liu 1 na1 ,

- Wei Yu 2 na1 ,

- Xiaoyan Gao 2 ,

- Shi Chen 2 ,

- Wei Qin 2 ,

- Ziyang Zhu 2 ,

- Chenghong Li 2 , 3 ,

- Fajiu Li 2 &

- Zhenguo Zhai 1

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 24 , Article number: 417 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Hemoptysis resulting from rupture of the pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm (PAP) is massive and fatal, while factor contributing to the rupture of pseudoaneurysm remains elusive. This study aimed to elucidate the clinical and radiological features of PAP and identify the risk factors associated with rupture.

Patients who developed hemoptysis with PAP were collected from January 2019 to December 2022 retrospectively. Clinical data of the demographic characteristics, radiological findings, treatment strategies, and prognosis were collected. A comparative analysis was performed on the characteristics in the ruptured and non-ruptured cases.

A total of 58 PAPs were identified in the 50 patients. The most common causes were infection (86%) and cancer (8%). The PAPs were located predominantly in the upper lobes of both lungs, and 57 (99.3%) were distributed in the segmental or subsegmental pulmonary arteries. The median diameter was 6.1(4.3–8.7) mm. A total of 29 PAPs were identified adjacent to pulmonary cavitations, with the median diameter of the cavity being 18.9 (12.4–34.8) mm. Rupture of pseudoaneurysm occurred in 21 cases (42%). Compared to unruptured group, the ruptured group had a significantly higher proportion of massive hemoptysis (57.1% vs. 6.9%, p < 0.001), larger pseudoaneurysm diameter (8.1 ± 3.2 mm vs. 6.0 ± 2.3 mm, p = 0.012), higher incidence of pulmonary cavitation (76.2% vs. 44.8%, p = 0.027), and larger cavitation diameters (32.9 ± 18.8 mm vs. 15.7 ± 8.4 mm, p = 0.005). The mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) in the ruptured group was also significantly higher than that in the unruptured group [23.9 ± 7.4 mmHg vs. 19.2 ± 5.0 mmHg, p = 0.011]. Endovascular treatment was successfully performed in all 21 patients with ruptured PAP, of which the clinical success rate was 96.0%. Five patients experienced recurrent hemoptysis within one year.

Conclusions

Massive hemoptysis, pseudoaneurysm diameter, pulmonary cavitation, and elevated mPAP were the risk factors for rupture of pseudoaneurysm. Our findings facilitate early identification and timely intervention of PAP at high risk of rupture.

Peer Review reports

Hemoptysis is a serious clinical complication, which can be fatal. The source of hemorrhage is mainly the bronchial artery. Hemoptysis due to pulmonary arterial origin is quite rare and it is estimated to occur in less than 10% of cases [ 1 ]. Pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm (PAP) is one of causes associated with pulmonary artery. Histologically, a pseudoaneurysm comprises either the media, adventitia, or the soft tissue surrounding the vessel, unlike a true aneurysm which involves all three layers of the artery. As a consequence, the pseudoaneurysm has a higher risk of rupture [ 2 ]. Hemoptysis has been described as a possible warning sign for rupture of PAP. In patients with massive hemoptysis undergoing bronchial artery embolization, 5-11% patients result from PAP rupture [ 3 ]. Once PAP ruptures, the mortality can be as high as 50% [ 4 ]. Therefore, risk assessment of the rupture of PAP is critical for early identification.

As low incidence and asymptomatic manifestation, patients with PAP are frequently underdiagnosis or misdiagnosed. PAP may be congenital or acquired. It has been found that PAP was associated with infection, primary or metastatic lung neoplasm, traumatic injury, pulmonary arterial hypertension, or vasculitis [ 5 , 6 ]. Previous case series have reported that pseudoaneurysms secondary to aspergillus and tumors both tend to be adjacent to cavitary lesion [ 4 , 7 ]. Rasmussen’s aneurysms were often accompanied by tuberculous cavities, which appeared to be more prone to rupture and cause fatal hemoptysis [ 4 ]. However, it remains uncertain whether the cavitary lesions and the rupture are clinically related.

The diameter of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) has been well-established as a crucial determinant and independent predictor of AAA rupture [ 8 ]. A reliable assessment of hemodynamics is also crucial for predicting the risk of AAA rupture [ 9 ]. Nevertheless, the relationship between pseudoaneurysm size and hemodynamics and PAP rupture has rarely been discussed. Currently, only case reports and series have described the etiology and radiological features. Little is known about the relevant factors for rupture of pseudoaneurysm in the lung. Therefore, this study aimed to illustrate the clinical characteristics of the rupture of pseudoaneurysm in a single center and further identify patients at high risk of rupture for early intervention.

Study population

Clinical data were collected from individuals who underwent computed tomography angiography (CTA) or transcatheter pulmonary vascular intervention for hemoptysis between January 2019 and December 2022. The medical data collected included age, gender, clinical symptoms, medical history, volume of hemoptysis, underlying etiology, imaging characteristics, and intervention and treatment outcomes. Hemoptysis was defined as mild (≤ 39 ml/day), moderate (40–199 ml/day), or massive (≥ 200 ml/day) [ 10 ]. The study received approval from institutional review boards for the retrospective review of electronic records and imaging (WHSHIRB-K-2022004). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Imaging findings

Computed tomography angiography

A 64-detector CT scanner was used to conduct CTA, from the thoracic inlet to a position 5–10 cm above the upper abdomen, employing a slice thickness of 1.00 mm. PAP was identified as focal dilations of the pulmonary artery. Information regarding the location, number, size, and level of PAP was collected systematically. Other CT findings, such as cavitations adjacent to PAP were also documented. The size of the PAP was determined using the longest diameter observed on the axial CT scan [ 11 ]. The size of the cavitation was measured based on its maximum diameter [ 12 ].

Digital subtraction angiography

All of the patients underwent bronchial and non-bronchial systemic collateral arterial angiography to identify the target vessels of hemoptysis. Right heart catheterization was conducted during digital subtraction angiography (DSA). This procedure involved measuring pressures at various sites and calculating the cardiac output (CO) using thermodilution. Pulmonary angiography was performed initially at the bifurcation of the right or left pulmonary artery to demonstrate the presence of any PAP and to delineate the anatomy of the pulmonary artery. Selective segmental or subsegmental angiography was performed to determine the location and feeding vessel.

Based on imaging from CTA and DSA, the PAPs were classified into four types. Type A can be visualized by non-selective pulmonary arteriography, type B by selective segmental or subsegmental pulmonary arteriography, type C by bronchial and non-bronchial systemic arteriography, while type D is only visible on pulmonary CT angiography and not on catheter-directed angiography [ 13 ]. If a PAP was not visualized on CTA but appeared on DSA pulmonary angiography, the maximum diameter of the PAP observed by DSA was measured to determine its size. The criteria of identification of rupture: (1) the presence of pseudoaneurysm and extravasation of contrast agent in angiography. (2) no signs of bronchial artery rupture were observed during angiography in patients with paroxysmal hemoptysis. (3) cessation or significant reduction of hemoptysis after embolization.

Treatment methods

A 5 F angiography catheter (Cook, USA) was superselected into the feeding vessels of the PAP and a 1.98 F microcatheter (Asahi, Japan) was superselected into the pseudoaneurysm sac to embolize with the coil. In a case in which the microcatheter could not reach the aneurysm sac, a pseudoaneurysm was excluded by coil embolization of the feeding vessel. The neck of the pseudoaneurysm was embolized when the pseudoaneurysm sac was too large to embolize fully. Patients were observed for 72 h postoperatively to assess complications and treatment effects. The evaluation of PAP embolization included technical success and clinical success [ 14 ]. Technical success was defined as a pseudoaneurysm no longer visible after embolization, while clinical success was defined as cessation of hemoptysis or a significant reduction after the procedure.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 24.0, IBM Corp). The data were expressed as either median and the first and third quartiles (Q1-Q3), mean ± standard deviation (SD), or absolute number and percentage of patients. For normally distributed data, the t-test was used to compare differences between the two groups. If the data were non-normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Chi-square (χ2) tests or Fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions between the two groups. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

From January 2019 to December 2022, a total of 2782 inpatients presented with hemoptysis. PAP was detected in 50 cases by pulmonary artery CTA or DSA arteriography. The flowchart for selecting the study population is shown in Fig. 1 . The baseline characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1 . The mean age was 62.1 ± 13.4 years, with 36 (72%) of them being male. The proportion of patients with massive hemoptysis was 14 (28%), and three of them received preoperative endotracheal intubation due to asphyxia. The cause of PAP is listed in Table 2 . Notably, the most common causes were infection and pulmonary malignancy. Infection was presented in 43 cases (86%), including obsolete and active tuberculosis (40% and 12%, respectively), bronchiectasis (12%), and focal pneumonia (8%). Fungal infection was observed in 5 patients (10%) and 3 of them were identified as Aspergillus infection through sputum culture (Fig. 2 ). Four cases (8%) were caused by malignant tumors, including primary lung cancer and liver cancer with lung metastasis.

The flowchart of selecting the study population

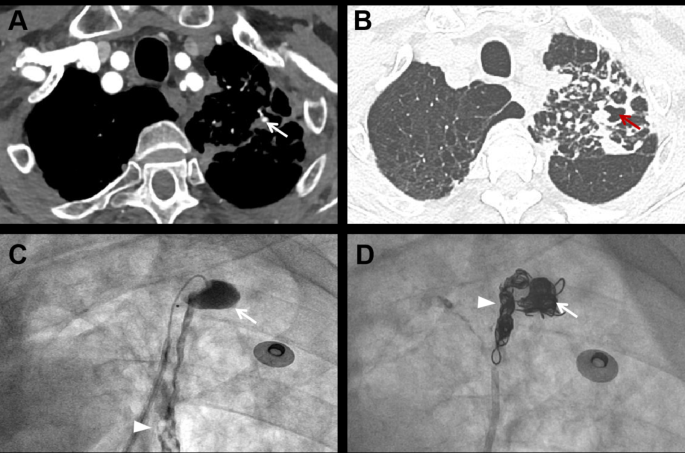

Representative images of Aspergillus infection combined with pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm. A 48-year-old male was admitted with massive hemoptysis. Sputum culture confirmed aspergillus infection. Bronchial artery embolization was performed six months ago due to hemoptysis. ( A ) The axial enhanced CT scan reveals a PAP (arrow) located in the segmental pulmonary artery of the right upper lobe. The PAP is accompanied by cavitary lesions; ( B ) The axial enhanced CT scan displayed a crescent-shaped cavity (red arrow) in the right upper lobe, indicating a typical imaging manifestation of aspergillus infection; ( C ) Selective subsegmental pulmonary artery angiography confirmed the PAP (arrow); ( D ) The aneurysmal sac (arrow) was embolized with coils

Imaging features

A total of 58 PAPs were identified in all the patients with hemoptosis. The imaging features are detailed in Table 3 . The PAPs were located primarily in the upper lobes of the lungs, with 24 (41.4%) in the left upper lobe, and 18 (31.0%) in the right upper lobe. They had a strong predilection for the peripheral pulmonary arteries and 57 (99.3%) were located in the segmental or subsegmental pulmonary arteries. The median diameter of PAP was 6.1(4.3–8.7) mm, and the maximum diameter was 15.2 mm. A total of 29 PAPs were identified adjacent to pulmonary cavitations (Fig. 3 ). The median diameter of the cavity was 18.9 (12.4–34.8) mm, with the maximum diameter being 77.4 mm. Four cases (8%) coexisted with bronchial artery aneurysms. pseudoaneurysm in 21 cases (42%) were considered as ruptured, of which most presented massive hemoptysis (Fig. 4 ).

Representative images of tuberculous cavity combined with pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm. A 54-year-old male was admitted to the hospital due to massive hemoptysis. He was diagnosed with sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. ( A ) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) in the segmental pulmonary artery of the left upper lobe; ( B ) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a large cavitary lesion (red arrow) adjacent to the PAP

Representative images of ruptured pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm. A 76-year-old male was hospitalized due to sudden massive hemoptysis. The patient had a history of tuberculosis and a positive sputum smear indicated the recurrence of tuberculosis. ( A ) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) distributed in the segmental pulmonary artery of the left upper lobe; ( B ) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows that the PAP is adjacent to a cavitary lesion (red arrow); ( C ) Selective subsegmental pulmonary arteriography shows contrast agent extravasation from the PAP to the cavity (arrow) and trachea (arrowhead), confirming its rupture; ( D ) Final angiography shows occlusion of pseudoaneurysm (arrow) and the proximal of the feeding vessel (arrowhead) after coil embolization

Clinical characteristics of ruptured pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm

To identify the risk factors for rupture of PAP, we compared the clinical features between ruptured and unruptured patients. The clinical characteristics and hemodynamic features of the two groups are summarized in Table 4 . No significant differences were observed between the two groups across gender, age, etiology, and distribution. Compared to the non-rupture group, the rupture group had a significantly higher proportion of massive hemoptysis (57.1% vs. 6.9%, p < 0.001), larger pseudoaneurysm diameter (8.1 ± 3.2 mm vs. 6.0 ± 2.3 mm, p = 0.012), higher incidence of pulmonary cavitation (76.2% vs. 44.8%, p = 0.027), and larger cavitation diameters (32.9 ± 18.8 mm vs. 15.7 ± 8.4 mm, p = 0.005). The mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) in the ruptured group was also significantly higher than that in the unruptured group (23.9 ± 7.4 mmHg vs. 19.2 ± 5.0 mmHg, p = 0.011). Meanwhile, there was no statistical significance in the other hemodynamic parameters.

Treatment and outcome