Module 11: Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Case studies: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify schizophrenia and psychotic disorders in case studies

Case Study: Bryant

Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized thoughts and delusion of control were noticeable. He told the doctors he has not been receiving any treatment, was not on any substance or medication, and has been experiencing these symptoms for about two weeks. Throughout the course of his treatment, the doctors noticed that he developed a catatonic stupor and a respiratory infection, which was identified by respiratory symptoms, blood tests, and a chest X-ray. To treat the psychotic symptoms, catatonic stupor, and respiratory infection, risperidone, MECT, and ceftriaxone (antibiotic) were administered, and these therapies proved to be dramatically effective. [1]

Case Study: Shanta

Shanta, a 28-year-old female with no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, was sent to the local emergency room after her parents called 911; they were concerned that their daughter had become uncharacteristically irritable and paranoid. The family observed that she had stopped interacting with them and had been spending long periods of time alone in her bedroom. For over a month, she had not attended school at the local community college. Her parents finally made the decision to call the police when she started to threaten them with a knife, and the police took her to the local emergency room for a crisis evaluation.

Following the administration of the medication, she tried to escape from the emergency room, contending that the hospital staff was planning to kill her. She eventually slept and when she awoke, she told the crisis worker that she had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) a month ago. At the time of this ADHD diagnosis, she was started on 30 mg of a stimulant to be taken every morning in order to help her focus and become less stressed over the possibility of poor school performance.

After two weeks, the provider increased her dosage to 60 mg every morning and also started her on dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets (10 mg) that she took daily in the afternoon in order to improve her concentration and ability to study. Shanta claimed that she might have taken up to three dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets over the past three days because she was worried about falling asleep and being unable to adequately prepare for an examination.

Prior to the ADHD diagnosis, the patient had no known psychiatric or substance abuse history. The urine toxicology screen taken upon admission to the emergency department was positive only for amphetamines. There was no family history of psychotic or mood disorders, and she didn’t exhibit any depressive, manic, or hypomanic symptoms.

The stimulant medications were discontinued by the hospital upon admission to the emergency department and the patient was treated with an atypical antipsychotic. She tolerated the medications well, started psychotherapy sessions, and was released five days later. On the day of discharge, there were no delusions or hallucinations reported. She was referred to the local mental health center for aftercare follow-up with a psychiatrist. [2]

Another powerful case study example is that of Elyn R. Saks, the associate dean and Orrin B. Evans professor of law, psychology, and psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School.

Saks began experiencing symptoms of mental illness at eight years old, but she had her first full-blown episode when studying as a Marshall scholar at Oxford University. Another breakdown happened while Saks was a student at Yale Law School, after which she “ended up forcibly restrained and forced to take anti-psychotic medication.” Her scholarly efforts thus include taking a careful look at the destructive impact force and coercion can have on the lives of people with psychiatric illnesses, whether during treatment or perhaps in interactions with police; the Saks Institute, for example, co-hosted a conference examining the urgent problem of how to address excessive use of force in encounters between law enforcement and individuals with mental health challenges.

Saks lives with schizophrenia and has written and spoken about her experiences. She says, “There’s a tremendous need to implode the myths of mental illness, to put a face on it, to show people that a diagnosis does not have to lead to a painful and oblique life.”

In recent years, researchers have begun talking about mental health care in the same way addiction specialists speak of recovery—the lifelong journey of self-treatment and discipline that guides substance abuse programs. The idea remains controversial: managing a severe mental illness is more complicated than simply avoiding certain behaviors. Approaches include “medication (usually), therapy (often), a measure of good luck (always)—and, most of all, the inner strength to manage one’s demons, if not banish them. That strength can come from any number of places…love, forgiveness, faith in God, a lifelong friendship.” Saks says, “We who struggle with these disorders can lead full, happy, productive lives, if we have the right resources.”

You can view the transcript for “A tale of mental illness | Elyn Saks” here (opens in new window) .

- Bai, Y., Yang, X., Zeng, Z., & Yang, H. (2018). A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. BMC psychiatry , 18(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1655-5 ↵

- Henning A, Kurtom M, Espiridion E D (February 23, 2019) A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Cureus 11(2): e4126. doi:10.7759/cureus.4126 ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A tale of mental illness . Authored by : Elyn Saks. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6CILJA110Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Authored by : Ashley Henning, Muhannad Kurtom, Eduardo D. Espiridion. Provided by : Cureus. Located at : https://www.cureus.com/articles/17024-a-case-study-of-acute-stimulant-induced-psychosis#article-disclosures-acknowledgements . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Elyn Saks. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elyn_Saks . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. Authored by : Yuanhan Bai, Xi Yang, Zhiqiang Zeng, and Haichen Yangcorresponding. Located at : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5851085/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

Schizophrenia case studies: putting theory into practice

This article considers how patients with schizophrenia should be managed when their condition or treatment changes.

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Treatments for schizophrenia are typically recommended by a mental health specialist; however, it is important that pharmacists recognise their role in the management and monitoring of this condition. In ‘ Schizophrenia: recognition and management ’, advice was provided that would help with identifying symptoms of the condition, and determining and monitoring treatment. In this article, hospital and community pharmacy-based case studies provide further context for the management of patients with schizophrenia who have concurrent conditions or factors that could impact their treatment.

Case study 1: A man who suddenly stops smoking

A man aged 35 years* has been admitted to a ward following a serious injury. He has been taking olanzapine 20mg at night for the past three years to treat his schizophrenia, without any problems, and does not take any other medicines. He smokes 25–30 cigarettes per day, but, because of his injury, he is unable to go outside and has opted to be started on nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in the form of a patch.

When speaking to him about his medicines, he appears very drowsy and is barely able to speak. After checking his notes, it is found that the nurses are withholding his morphine because he appears over-sedated. The doctor asks the pharmacist if any of the patient’s prescribed therapies could be causing these symptoms.

What could be the cause?

Smoking is known to increase the metabolism of several antipsychotics, including olanzapine, haloperidol and clozapine. This increase is linked to a chemical found in cigarettes, but not nicotine itself. Tobacco smoke contains aromatic hydrocarbons that are inducers of CYP1A2, which are involved in the metabolism of several medicines [1] , [2] , [3] . Therefore, smoking cessation and starting NRT leads to a reduction in clearance of the patient’s olanzapine, leading to increased plasma levels of the antipsychotic olanzapine and potentially more adverse effects — sedation in this case.

Patients who want to stop, or who inadvertently stop, smoking while taking antipsychotics should be monitored for signs of increased adverse effects (e.g. extrapyramidal side effects, weight gain or confusion). Patients who take clozapine and who wish to stop smoking should be referred to their mental health team for review as clozapine levels can increase significantly when smoking is stopped [3] , [4] .

For this patient, olanzapine is reduced to 15mg at night; consequently, he seems much brighter and more responsive. After a period on the ward, he has successfully been treated for his injury and is ready to go home. The doctor has asked for him to be supplied with olanzapine 15mg for discharge along with his NRT.

What should be considered prior to discharge?

It is important to discuss with the patient why his dose was changed during his stay in hospital and to ask whether he intends to start smoking again or to continue with his NRT. Explain to him that if he wants to begin, or is at risk of, smoking again, his olanzapine levels may be impacted and he may be at risk of becoming unwell. It is necessary to warn him of the risk to his current therapy and to speak to his pharmacist or mental health team if he does decide to start smoking again. In addition, this should be used as an opportunity to reinforce the general risks of smoking to the patient and to encourage him to remain smoke-free.

It is also important to speak to the patient’s community team (e.g. doctors, nurses), who specialise in caring for patients with mental health disorders, about why the olanzapine dose was reduced during his stay, so that they can then monitor him in case he does begin smoking again.

Case 2: A woman with constipation

A woman aged 40 years* presents at the pharmacy. The pharmacist recognises her as she often comes in to collect medicine for her family. They are aware that she has a history of schizophrenia and that she was started on clozapine three months ago. She receives this from her mental health team on a weekly basis.

She has visited the pharmacy to discuss constipation that she is experiencing. She has noticed that since she was started on clozapine, her bowel movements have become less frequent. She is concerned as she is currently only able to go to the toilet about once per week. She explains that she feels uncomfortable and sick, and although she has been trying to change her diet to include more fibre, it does not seem to be helping. The patient asks for advice on a suitable laxative.

What needs to be considered?

Constipation is a very common side effect of clozapine . However, it has the potential to become serious and, in rare cases, even fatal [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] . While minor constipation can be managed using over-the-counter medicines (e.g. stimulant laxatives, such as senna, are normally recommended first-line with stool softeners, such as docusate, or osmotic laxatives, such as lactulose, as an alternative choice), severe constipation should be checked by a doctor to ensure there is no serious bowel obstruction as this can lead to paralytic ileus, which can be fatal [9] . Symptoms indicative of severe constipation include: no improvement or bowel movement following laxative use, fever, stomach pain, vomiting, loss of appetite and/or diarrhoea, which can be a sign of faecal impaction overflow.

As the patient has been experiencing this for some time and is only opening her bowels once per week, as well as having other symptoms (i.e. feeling uncomfortable and sick), she should be advised to see her GP as soon as possible.

The patient returns to the pharmacy again a few weeks later to collect a prescription for a member of their family and thanks the pharmacist for their advice. The patient was prescribed a laxative that has led to resolution of symptoms and she explains that she is feeling much better. Although she has a repeat prescription for lactulose 15ml twice per day, she says she is not sure whether she needs to continue to take it as she feels better.

What advice should be provided?

As she has already had an episode of constipation, despite dietary changes, it would be best for the patient to continue with the lactulose at the same dose (i.e. 15ml twice daily), to prevent the problem occurring again. Explain to the patient that as constipation is a common side effect of clozapine, it is reasonable for her to take laxatives before she gets constipation to prevent complications.

Pharmacists should encourage any patient who has previously had constipation to continue taking prescribed laxatives and explain why this is important. Pharmacists should also continue to ask patients about their bowel habits to help pick up any constipation that may be returning. Where pharmacists identify patients who have had problems with constipation prior to starting clozapine, they can recommend the use of a prophylactic laxative such as lactulose.

Case 3: A mother is concerned for her son who is talking to someone who is not there

A woman has been visiting the pharmacy for the past 3 months to collect a prescription for her son, aged 17 years*. In the past, the patient has collected his own medicine. Today the patient has presented with his mother; he looks dishevelled, preoccupied and does not speak to anyone in the pharmacy.

His mother beckons you to the side and expresses her concern for her son, explaining that she often hears him talking to someone who is not there. She adds that he is spending a lot of time in his room by himself and has accused her of tampering with his things. She is not sure what she should do and asks for advice.

What action can the pharmacist take?

It is important to reassure the mother that there is help available to review her son and identify if there are any problems that he is experiencing, but explain it is difficult to say at this point what he may be experiencing. Schizophrenia is a psychotic illness which has several symptoms that are classified as positive (e.g. hallucinations and delusions), negative (e.g. social withdrawal, self-neglect) and cognitive (e.g. poor memory and attention).

Many patients who go on to be diagnosed with schizophrenia will experience a prodromal period before schizophrenia is diagnosed. This may be a period where negative symptoms dominate and patients may become isolated and withdrawn. These symptoms can be confused with depression, particularly in younger people, though depression and anxiety disorders themselves may be prominent and treatment for these may also be needed. In this case, the patient’s mother is describing potential psychotic symptoms and it would be best for her son to be assessed. She should be encouraged to take her son to the GP for an assessment; however, if she is unable to do so, she can talk to the GP herself. It is usually the role of the doctor to refer patients for an assessment and to ensure that any other medical problems are assessed.

Three months later, the patient comes into the pharmacy and seems to be much more like his usual self, having been started on an antipsychotic. He collects his prescription for risperidone and mentions that he is very worried about his weight, which has increased since he started taking the newly prescribed tablets. Although he does not keep track of his weight, he has noticed a physical change and that some of his clothes no longer fit him.

What advice can the pharmacist provide?

Weight gain is common with many antipsychotics [10] . Risperidone is usually associated with a moderate chance of weight gain, which can occur early on in treatment [6] , [11] , [12] . As such, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends weekly monitoring of weight initially [13] . As well as weight gain, risperidone can be associated with an increased risk of diabetes and dyslipidaemia, which must also be monitored [6] , [11] , [12] . For example, the lipid profile and glucose should be assessed at 12 weeks, 6 months and then annually [12] .

The pharmacist should encourage the patient to attend any appointments for monitoring, which may be provided by his GP or mental health team, and to speak to his mental health team about his weight gain. If he agrees, the pharmacist could inform the patient’s mental health team of his weight gain and concerns on his behalf. It is important to tackle weight gain early on in treatment, as weight loss can be difficult to achieve, even if the medicine is changed.

The pharmacist should provide the patient with advice on healthy eating (e.g. eating a balanced diet with at least five fruit and vegetables per day) and exercising regularly (e.g. doing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week), and direct him to locally available services. The pharmacist can record the adverse effect on the patient’s medical record, which will help flag this in the future and thus help other pharmacists to intervene should he be prescribed risperidone again.

*All case studies are fictional.

Useful resources

- Mind — Schizophrenia

- Rethink Mental Illness — Schizophrenia

- Mental Health Foundation — Schizophrenia

- Royal College of Psychiatrists — Schizophrenia

- NICE guidance [CG178] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management

- NICE guidance [CG155] — Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management

- British Association for Psychopharmacology — Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology

About the author

Nicola Greenhalgh is lead pharmacist, Mental Health Services, North East London NHS Foundation Trust

[1] Chiu CC, Lu ML, Huang MC & Chen KP. Heavy smoking, reduced olanzapine levels, and treatment effects: a case report. Ther Drug Monit 2004;26(5):579–581. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200410000-00018

[2] de Leon J. Psychopharmacology: atypical antipsychotic dosing: the effect of smoking and caffeine. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55(5):491–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.491

[3] Mayerova M, Ustohal L, Jarkovsky J et al . Influence of dose, gender, and cigarette smoking on clozapine plasma concentrations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2018;14:1535–1543. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S163839

[4] Ashir M & Petterson L. Smoking bans and clozapine levels. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2008;14(5):398–399. doi: 10.1192/apt.14.5.398b

[5] Young CR, Bowers MB & Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull 1998;24(3):381–390. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033333

[6] Taylor D, Barnes TRE & Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry . 13th edn. London: Wiley Blackwell; 2018

[7] Oke V, Schmidt F, Bhattarai B et al . Unrecognized clozapine-related constipation leading to fatal intra-abdominal sepsis — a case report. Int Med Case Rep J 2015;8:189–192. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S86716

[8] Hibbard KR, Propst A, Frank DE & Wyse J. Fatalities associated with clozapine-related constipation and bowel obstruction: a literature review and two case reports. Psychosomatics 2009;50(4):416–419. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.416

[9] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Clozapine: reminder of potentially fatal risk of intestinal obstruction, faecal impaction, and paralytic ileus. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/clozapine-reminder-of-potentially-fatal-risk-of-intestinal-obstruction-faecal-impaction-and-paralytic-ileus (accessed April 2020)

[10] Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382(9896):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3

[11] Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory . Norwich: Lloyd-Reinhold Communications LLP; 2018

[12] Cooper SJ & Reynolds GP. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30(8):717–748. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645254

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 (accessed April 2020)

You might also be interested in…

Nearly half of long-term antidepressant users could safely taper off medication using helpline

Boots UK shuts online mental health service to new patients

Eating disorders: identification, treatment and support

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Understanding Schizophrenia: A Case Study

Schizophrenia is characterized mainly, by the gross distortion of reality, withdrawal from social interaction, disorganization and fragmentation of perception, thoughts and emotions. Insight is an important concept in clinical psychiatry, a lack of insight is particularly common in schizophrenia patient. Previous studies reported that between 50-80% of patients with schizophrenia do not believe, they have a disorder. By the help of psychological assessment, we can come to know an individual's problems especially in cases, where patient is hesitant or has less insight into illness. Assessment is also important for the psychological management of the illness. Knowing the strengths and weaknesses of that particular individual with psychological analysis tools can help to make better plan for the treatment. The present study was designed to assess the cognitive functioning, to elicit severity of psychopathology, understanding diagnostic indicators, personality traits that make the individual vulnerable to the disorder and interpersonal relationship in order to plan effective management. Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder, characterized mainly by the gross distortion of reality, withdrawal from social interaction, and disorganization and fragmentation of perception, thought and emotion. Approximately, 1% world population suffering with the problem of Schizophrenia. Both male and female are almost equally affected with slight male predominance. Schizophrenia is socioeconomic burden with suicidal rate of 10% and expense of 0.02-1.65% of GDP spent on treatment. Other co-morbid factors associated with Schizophrenia are diabetes, Obesity, HIV infection many metabolic disorders etc. Clinically, schizophrenia is a syndrome of variables symptoms, but profoundly disruptive, psychopathology that involves cognition, emotion, perception, and other aspects of behavior. The expression of these manifestations varies across patients and over the time, but the effect of the illness is always severe and is usually long-lasting. Patients with schizophrenia usually get relapse after treatment. The most common cause for the relapse is non-adherent with the medication. The relapse rate of schizophrenia increases later time on from 53.7% at 2 years to

Related Papers

Bangladesh Journal of Psychiatry

Luna Krasota Nur Laila

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric illness with high rate of relapse which is commonly associated with noncompliance of medicine, as well as stress and high expressed emotions. The objective of the study was to determine the factors of relapse among the schizophrenic patients attending in outpatient departments of three tertiary level psychiatric facilities in Bangladesh. This was a cross sectional study conducted from July, 2001 to June, 2002. Two hundred patients including both relapse and nonrelapse cases of schizophrenia and their key relatives were included by purposive sampling. The results showed no statistically significant difference in terms of relapse with age, sex, religion, residence, occupation and level of education (p>0.05), but statistically significant difference was found with marital status and economic status (p<0.01). The proportion of non-compliance was found to be 80% and 14%, of high expressed emotion was 17% and 2% and of the occurrence of stressf...

Ashok Kumar Patel

BMC Psychiatry

Bonginkosi Chiliza

Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria

Helio Elkis

OBJECTIVES: The heterogeneity of clinical manifestations in schizophrenia has lead to the study of symptom clusters through psychopathological assessment scales. The objective of this study was to elucidate clusters of symptoms in patients with refractory schizophrenia which may also help to assess the patients' therapeutical response. METHODS: Ninety-six treatment resistant patients were evaluated by the anchored version Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-A) as translated into Portuguese. The inter-rater reliability was 0.80. The 18 items of the BPRS-A were subjected to exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation. RESULTS: Four factors were obtained: Negative/Disorganization, composed by emotional withdrawal, disorientation, blunted affect, mannerisms/posturing, and conceptual disorganization; Excitement, composed of excitement, hostility, tension, grandiosity, and uncooperativeness, grouped variables that evoke brain excitement or a manic-like syndrome; Positive, compo...

Nicholas Tarrier

Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Research

James Mwaura

Sou Agarwal

Schizophrenia Bulletin

Joseph Goldberg

International journal of mental health nursing

Inayat ullah Shah

Despite a large body of research evaluating factors associated with the relapse of psychosis in schizophrenia, no studies in Pakistan have been undertaken to date to identify any such factors, including specific cultural factors pertinent to Pakistan. Semistructured interviews and psychometric measures were undertaken with 60 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (49 male and 11 female) and their caregivers at four psychiatric hospitals in the Peshawar region in Pakistan. Factors significantly associated with psychotic relapse included treatment non-adherence, comorbid active psychiatric illnesses, poor social support, and high expressed emotion in living environments (P < 0.05). The attribution of symptoms to social and cultural values (97%) and a poor knowledge of psychosis by family members (88%) was also prevalent. In addition to many well-documented factors associated with psychotic relapse, beliefs in social and cultural myths and values were found to be an important, and p...

Octavian Vasiliu

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Medicine and Public Health

amresh srivastava

Epidemiologia e psichiatria sociale

Rita Roncone

Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry

Archives of Psychiatric Nursing

Karen Schepp

Derege Kebede

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Swapnesh Tiwari

Actas españolas de psiquiatría

Enrique Echeburúa

European Psychiatry

Schizophrenia Research

Jonathan Rabinowitz

Adellah Sariah

Rikus Knegtering

Actas espanolas de psiquiatria

Manuel Bousono

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease

Andrea Affaticati , Rebecca Ottoni

Psychiatry Research

Massimo Tusconi

zewdu shewangizaw

IOSR Journals

Annals of General Psychiatry

Andreas Schreiner

Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN

Lawrence Annable

ROMANIAN JOURNAL …

Cornelia Rada

Ifeta Licanin

American family physician

Stephen Schultz

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

CASE REPORT article

Early-onset schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms: a case study of a drug-naive female patient treated with cariprazine.

- Institute of Genomic Medicine and Rare Disorders, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental disorder characterized by positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms. Negative symptoms are usually present from the prodromal phase; early diagnosis and management of negative symptoms is a major health concern since an insidious onset dominated by negative symptoms is associated with a worse outcome. Antipsychotic medications, which are effective for treating positive symptoms, are generally ineffective for treating negative or cognitive symptoms. We present a 23-year-old woman showing severe symptoms at her first visit to our department. The patient’s parents reported that their daughter had experienced several years of psychosocial decline and putative psychiatric symptoms, but no medical attention had been previously sought; as such, the diagnosis of schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms was very much delayed. Early onset of schizophrenia, longer duration of untreated psychosis, and severe negative symptoms, which have limited treatment options, suggested a poor prognosis. We initiated monotherapy with cariprazine, a novel antipsychotic that has recently been proven efficacious in treating schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms. This report describes a 52-week cariprazine treatment regimen and follows the patient’s impressive clinical improvement confirmed by PANSS and CGI scores, and psychological tests.

Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic, and heterogeneous mental disorder that often has debilitating long-term outcomes. Its lifetime prevalence rate is estimated to be approximately 1% worldwide in the adult population ( Lehman et al., 2010 ). Onset generally occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood, with an average age of 18 years for men and 25 years for women. 1 The term early-onset schizophrenia (EOS) is used to refer to patients who are diagnosed with the disorder before this age. EOS is a severe, frequently disabling, and chronic condition with a prevalence approaching 0.5% in those younger than 18 years ( Hafner and Van der Heiden, 1997 ).

Schizophrenia is accompanied by a distortion of personality that affects fundamental mental and social functions, making everyday life extremely difficult for patients. Clinical symptoms are often classified in three main domains: positive symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness/persecution; negative symptoms, such as emotional withdrawal, blunted affect, and passive social withdrawal; and cognitive symptoms, such as impaired perception, learning, thinking, and memorizing. EOS may be accompanied by greater symptom severity, premorbid developmental impairment, ‘soft’ neurological signs (eg, clumsiness, motor incoordination), and a higher rate of substance abuse ( Hsiao and McClellan, 2008 ; Clemmensen et al., 2012 ; Immonen et al., 2017 ). Accordingly, diagnosis of EOS is often difficult and frequently delayed since onset is more commonly insidious than acute, which makes it difficult to differentiate EOS from underlying cognitive deficits, premorbid functional impairment, or other abnormalities ( Russell, 1994 ; Bartlet, 2014 ). Given this common delay in recognition of the disorder, the duration of untreated psychosis is often very long, further contributing to a poor outcome ( Penttila et al., 2014 ).

Although various hypotheses have been developed, the etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia and EOS is not fully understood ( McGuffin, 2004 ; Klosterkotter et al., 2011 ). 2 Among the rising and falling neurochemical theories, the dopamine hypothesis has remained a primary hypothesis guiding the treatment of schizophrenia. There are four dopaminergic pathways in the human brain: the mesolimbic, the mesocortical, the tuberoinfundibular, and the nigrostriatal. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia are associated with the hyperdopaminergic state of D 2 receptors in the mesolimbic area, while negative and cognitive symptoms are believed to be related to the hypodopaminergic dysregulation of the prefrontal cortex ( Stahl, 2003 ).

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia, which affect up to 60% of patients with schizophrenia ( Rabinowitz et al., 2013 ), form a complex clinical constellation of symptoms that challenge both diagnosis and treatment. By definition, negative symptoms mean the absence of normal functions. Negative symptoms are classified by their etiology as primary negative symptoms, which are core features of the disease itself, and secondary negative symptoms, which are consequences of positive symptoms, antipsychotic treatment, depression or extrapyramidal side effects. Five constructs have been accepted by general consensus as key aspects of negative symptoms: blunted affect, alogia, anhedonia, asociality, and avolition ( Marder and Galderisi, 2017 ). Patients with predominant negative symptoms lose their motivation, cannot function at school or work, and their interpersonal relationships severely decay. Due to impaired daily functioning and social amotivation, they may need constant care.

Although early intervention is associated with improvement in negative symptoms ( Boonstra et al., 2012 ), this may be challenging since negative symptoms develop slowly and may be difficult to detect or differentiate from other clinical features ( Kirkpatrick et al., 2001 ; Galderisi et al., 2018 ). Moreover, a more insidious onset predicts poorer outcome and more severe negative symptoms ( Kao and Liu, 2010 ; Immonen et al., 2017 ; Murru and Carpiniello, 2018 ). Diagnosis of patients with predominantly negative symptoms (lacking manifest psychotic signs) is often delayed, resulting in a longer duration of untreated psychosis. The length of untreated psychosis is closely related to poorer functional outcome ( Perkins et al., 2005 ).

Negative symptoms have traditionally had minimal response to antipsychotic treatment. First-generation antipsychotics are effective in treating positive symptoms, but negative symptom improvement is only evident when symptoms are secondary to positive symptoms. It was initially hoped that second-generation antipsychotics would target both positive and negative symptoms, but efficacy data have been disappointing. This was a large meta-analysis where only four second-generation drugs (amisulpride, risperidone, olanzapine, and clozapine) resulted to be more efficacious than first-generation antipsychotics in the overall change of symptoms, including positive and negative symptoms. The other examined second-generation antipsychotics were only as efficacious as first-generation antipsychotic agents ( Leucht et al., 2009 ). These studies were mainly conducted in patients with general symptoms of schizophrenia, therefore a secondary effect on negative symptoms could not be ruled out. Therefore negative symptom improvement cannot be considered a core component of atypicality ( Veerman et al., 2017 ). Previous studies have demonstrated that no drug had a beneficial effect on negative symptoms when compared to another drug ( Arango et al., 2013 ; Millan et al., 2014 ; Fusar-Poli et al., 2015 ), meaning that head to head comparisons of different agents among each other did not result in superiority of one drug to another. The latest comparison ( Krause et al., 2018 ) evaluated all studies that have been performed in the negative symptom population so far, and has found that amisulpride claimed superiority only to placebo, olanzapine was superior to haloperidol, but only in a small trial (n = 35), and cariprazine outperformed risperidone in a large well-controlled trial.

Hence cariprazine emerged as an agent of particular interest in regard to negative symptoms. Cariprazine is a dopamine D 3 /D 2 receptor partial agonist and serotonin 5-HT 1A receptor partial agonist. It has been hypothesized that cariprazine is the only antipsychotic that can block D 3 receptors in the living brain, thereby exhibiting functions that are related to D 3 blockade (e.g., improvement of negative symptoms) ( Stahl, 2016 ). In that large clinical trial including 460 patients with predominant negative symptoms and stable positive symptoms of schizophrenia, cariprazine was significantly more effective than risperidone in improving negative symptoms and patient functioning ( Nemeth et al., 2017 ).

Case Description

The 23-year-old female patient visited the Institute of Rare Diseases at our university with her parents. They had suspected for a long time that something was wrong with their daughter, but this was the first time they had asked for medical help. The patient was quiet and restrained since she did not speak much, her parents told us her story instead. Initially, the patient had done very well in a bilingual secondary school and was socially active with friends and peers. At the age of 15 years, her academic performance started to deteriorate, with her first problems associated with difficulty learning languages and memorizing. Her school grades dropped, and her personality started to gradually change. She became increasingly irritated, and was verbally and physically hostile toward her classmates, resorting to hitting and kicking at times. She was required to repeat a school year and subsequently dropped out of school at the age of 18 because she was unable to complete her studies. During these years, her social activity greatly diminished. She lived at home with her parents, did not go out with friends, or participate in relationships. Most of the time she was silent and unsociable, but occasionally she had fits of laughter without reason. Once the patient told her mother that she could hear the thoughts of others and was probably hearing voices as well. Slowly, her impulse-control problems faded; however, restlessness of the legs was quite often present.

Our patient’s medical history was generally unremarkable. She lacked neurological or psychiatric signs. She had a tonsillectomy and adenotomy at age 7 years. Epilepsy was identified in the patient’s family history (father’s uncle). On physical examination, there were no signs of internal or neurological disease; body mass index was 21.5 (normal weight).

During the first psychiatric interview and examination, we found that our patient was alert and vigilant, but had trouble relating due to decreased integrity of consciousness. Her attention could be aroused or partially directed, and she had difficulty keeping a target idea. Autopsychic and allopsychic orientations were preserved. Longer thinking latencies and slowed movement responses were observed, sometimes with even cataleptic impressions. Cognitive functions, such as thinking, memory, and concept formation, were severely impaired, and we were unable to carry out some of our neurocognitive tests -such as the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination ( Hsieh et al., 2013 ), the Toulouse-Pieron attention test (Kanizsa G1951), Bells test ( Gauthier et al., 1989 ) and the Trail Making Test- because of the patient’s denial of symptoms and refusal to cooperate.

She often looked aside and laughed frequently, suggesting the presence of perceptual disturbances, but she denied her symptoms when asked. In contrast to the periodic inappropriate laughing, apathy and anhedonia were markedly present. During the examination, the patient could not recall anything she would do or even think of with pleasure. According to the heteroanamnesis, she lost her interest in activities she used to like, did not go out with friends anymore, and showed no signs of joy or intimacy towards her family members either.

Along with the affective hyporesponsiveness, amotivation and a general psychomotor slowing were observed. Hypobulia, void perspectives, and lack of motivation were explored. Parental statements indicated that the patient’s social activity had continued to diminish, and her appearance and personal physical hygiene had deteriorated. When we initiated a conversation, the patient was negativistic and agitated. Her critical thinking ability was reduced, which led to inappropriate behavior (she, e.g., unexpectedly stood up and left the room while the examination was still ongoing). Considering her status, she was admitted to the clinic after her first visit.

After several differential diagnostic tests were performed (e.g., routine diagnostic laboratory parameters, immune serological analyses, electroencephalogram, magnetic resonance imaging, genetic testing), all the possible common and rare disorders, such as Huntington’s disease, Niemann Pick C disease, mitochondrial disorders, and autoimmune diseases, were ruled out.

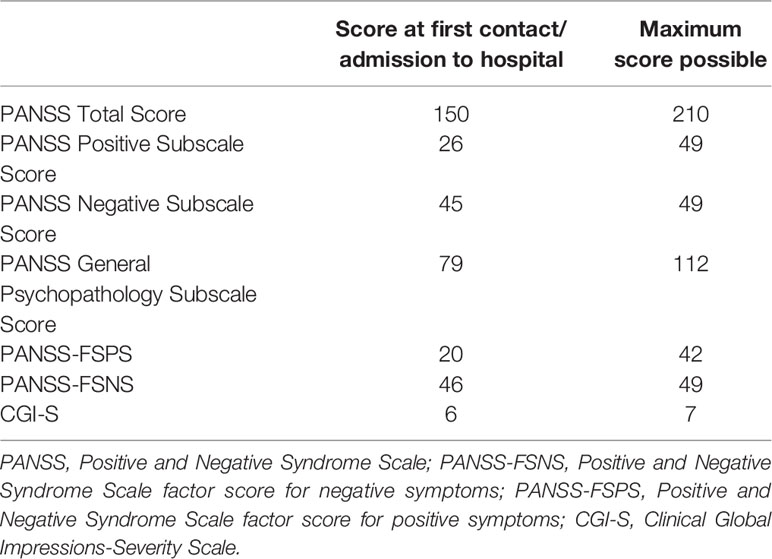

At first contact, to differentiate the symptoms and severity of putative schizophrenia, we mapped the positive, negative, and general symptoms, as well as a clinical impression, using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms, and the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) ( Groth-Marnat, 2009 ).

The patient had a very high PANSS total score, which corresponded to being considered “severely ill” or “among the most severely ill’ on the CGI-S ( Leucht et al., 2005 ). The PANSS score was derived dominantly from the negative items of the scale. Overall, her negative symptoms fulfilled criteria for predominantly negative symptoms, meaning that positive symptomatology was reduced, while negative symptoms were more explicit and dominated the clinical picture ( Riedel et al., 2005 ; Olie et al., 2006 ; Mucci et al., 2017 ). Baseline rating scale sores are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1 Summary of symptom scale scores at the time of admission to the hospital.

The diagnosis of EOS with predominantly negative symptoms was given and treatment with the antipsychotic agent cariprazine was initiated. The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks following her arrival at the clinic. Cariprazine was started at the dose of 1.5 mg/day and titrated up to 4.5 mg/day over a 2-week period: the patient received 1.5 mg/day for the first 3 days, 3 mg/day from day 4 to day 12, and eventually 4.5 mg/day from day 13 onward. During these 2 weeks, which were spent in hospital, the patient’s explicit negative symptoms such as poverty of speech, psychomotor retardation, poor eye contact, and affective nonresponsiveness improved; however, delusions and hallucinatory perceptions did not fade significantly.

Two weeks after discharge, we saw the patient for her first outpatient visit. Significant clinical improvement was observed. The patient calmly cooperated during the examination, with no signs of agitation. She was oriented to time, place, and self, attention could be drawn and directed, and she was able to keep a target idea and change the subject. Although according to the family, perceptual disturbances were still present, laughing with no reason and looking aside were much less frequent, and restlessness of the legs had stopped; these symptoms were not observed during the examination. Psychomotoric negativism had improved greatly, the patient was more communicative, and she paid more attention to the activities of family members. The pace of speech was close to normal: the thinking latencies and slowed movement responses as observed at admission were not seen anymore. The patient had adequate reaction time to questions asked and could focus in the interview. Mild obstipation and somnolence in the evening were her main complaints. Apart from some tick-like eye closures, there was no pathological finding during physical and neurological examination. At this point, cariprazine was reduced to 3 mg per day.

At her second outpatient visit, which occurred 8 weeks after treatment initiation, further improvement was observed. According to her mother, the patient was more active and open at home. Neurological examination found that the alternating movements of her fingers were slightly slowed. Cariprazine 3 mg/day was continued with concomitant anticholinergic medication.

At the third outpatient visit, which occurred 16 weeks after the first contact, the patient’s overall symptoms, including cognitive functions, such as memory and abstract thinking, as well as functions in activities of daily living, had improved remarkably. She had started to participate in the family’s daily life, even taking responsibility for some household duties; further, she went to the hairdresser for the first time in years, a step forward from her previous state of self-neglect. She was probably still having auditory hallucinations, which she considered natural, and some extrapyramidal symptom (EPS)-like ruminating movements, like to-and-fro swinging of her trunk, were observed. She did not look aside any more and tics were no longer present. Compared with previous visits overall, she was very relaxed, retained eye contact, cooperated, and communicated adequately during the interview. She started to develop insight into her condition, and she told us that her “thoughts were not healthy.” At the last two visits, the synkinesis of the arms was reduced.

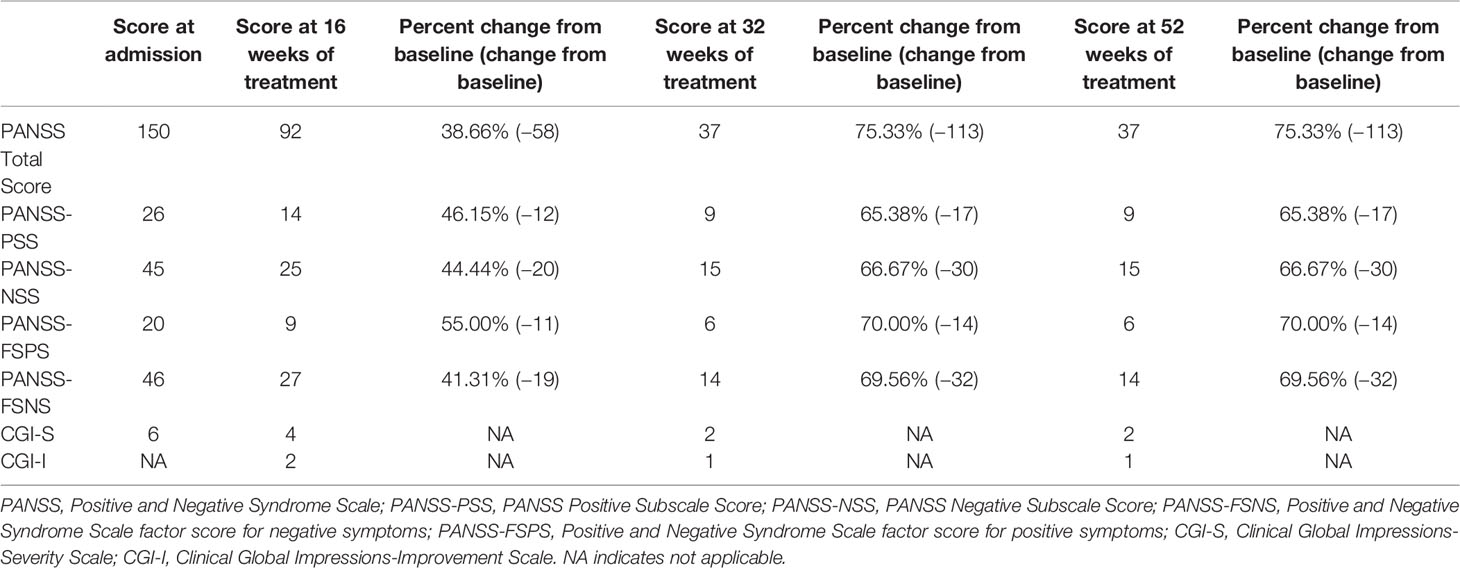

After 16 weeks of treatment, the patient’s PANSS Negative Subscale Score and PANSS factor score for negative symptoms (PANSS-FSNS) score were reduced by 44.44% and 41.31%, respectively. Recent studies have demonstrated that linking the percentage improvement of PANSS with CGI-S and -Improvement (CGI-I) scores shows that a 25–50% reduction of PANSS scores corresponds to clinically meaningful change ( Correll et al., 2011 ; Fusar-Poli et al., 2015 ). In acutely ill patients with predominantly positive symptoms who are more likely to respond well to treatment, the 50% cutoff would be a more clinically meaningful criterion; however, since even slight improvement might represent a clinically significant effect in a patient with atypical schizophrenia, the use of 25% cutoff is justified ( Correll et al., 2011 ; Fusar-Poli et al., 2015 ).

In this regard, the 44.44% (change from baseline: −20) and 41.31% (change from baseline: −19) improvement demonstrated on PANSS Negative Symptom subscale and PANSS-FSNS, respectively, are considered a clearly clinically relevant change. Beyond the impaired synkinesis and alternating movement of the arms and fingers, there were no other treatment-related physical dysfunctions. Change from baseline on the PANSS and CGI scales are shown over the course of treatment in Table 2 .

Table 2 Summary of symptom scale scores at weeks 16, 32, and 52.

Since our patient’s symptoms demonstrated strong improvement and tolerability was favorable, cariprazine therapy was continued. Improvement in both negative and positive symptoms was maintained over the course of treatment. At her later visits (32 and 52 weeks), PANSS total score was reduced to a level that was close to the minimum, and the decrease in negative symptom scores was considerable (PANSS-NSS=66.67% and PANS-FSNS=70.00% at both time points). The patient’s progress was also reflected in clinical and functional measurements, with the CGI-S score reduced to 2 (borderline mentally ill) and a CGI-I score of 1 (very much improved) indicating notable improvement.

Cariprazine has demonstrated broad spectrum efficacy in the treatment of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. In a field where no treatment is available for difficult-to-treat negative symptoms, this case is unique and may have important implications for schizophrenia treatment. Despite experiencing approximately 8 years of untreated symptoms and functional impairment associated with predominantly negative symptom EOS, our 23-year-old female patient showed considerable symptomatic and functional improvement after several weeks of treatment with cariprazine. Given that the duration of untreated negative symptoms is associated with worse functional outcomes ( Boonstra et al., 2012 ), the remarkable improvement seen in this case shows how valuable cariprazine could be for patients with similar symptom presentations. Although it is not possible to generalize the observations and findings of this single case, it has the novelty of detecting a potential effect of cariprazine in a drug-naïve patient with marked negative symptoms of early-onset schizophrenia. To our knowledge, no cariprazine-related data has been published in this type of patients. A single case study is obviously far from being predictive for the efficacy of a drug, however, the results seen with this case are promising. With a dose recommended for patients with negative symptoms, our patient’s clinical condition, including positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, as well as social functioning have improved notably, with the effect maintained for over 12 months. Generally, cariprazine has been well tolerated, with mild EPS observed after 8 weeks, but no metabolic, cardiac, or other side effects.

This case report suggests that the management of patients with EOS and prominent negative symptoms is achievable in everyday practice with cariprazine. More real-world clinical experience is needed to support this finding.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was supported from Research and Technology Innovation Fund by the Hungarian National Brain Research Program (KTIA_NAP_ 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002). Editorial support for this case report was supported by funding from Gedeon Richter. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the patient and her family for giving us the opportunity to share her story in the form of a publication. Also, we acknowledge editorial assistance was provided by Carol Brown, MS, ELS, of Prescott Medical Communications Group, Chicago, Illinois, USA, a contractor of Gedeon Richter plc.

- ^ http://www.schizophrenia.com/szfacts.htm

- ^ https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml

Arango, C., Garibaldi, G., Marder, S. R. (2013). Pharmacological approaches to treating negative symptoms: a review of clinical trials. Schizophr. Res. 150 (2-3), 346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.026

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bartlet, J. (2014). Childhood-onset schizophrenia: what do we really know? Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2 (1), 735–747. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.927738

Boonstra, N., Klaassen, R., Sytema, S., Marshall, M., De Haan, L., Wunderink, L., et al. (2012). Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms–a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Schizophr. Res. 142 (1-3), 12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.017

Clemmensen, L., Vernal, D. L., Steinhausen, H. C. (2012). A systematic review of the long-term outcome of early onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 12, 150. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-150

Correll, C. U., Kishimoto, T., Nielsen, J., Kane, J. M. (2011). Quantifying clinical relevance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Clin. Ther. 33 (12), B16–B39. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.016

Fusar-Poli, P., Papanastasiou, E., Stahl, D., Rocchetti, M., Carpenter, W., Shergill, S., et al. (2015). Treatments of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of 168 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Schizophr. Bull. 41 (4), 892–899. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu170

Galderisi, S., Mucci, A., Buchanan, R. W., Arango, C. (2018). Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry 5 (8), 664–677. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6

Gauthier, L., Dehaut, F., Joanette, Y. (1989). A quantitative and qualitative test for visual neglect. Int. J. Clin. Neuropsychol. 11 (2), 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.04.018

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Groth-Marnat, G. (2009). “Handbook of Psychological Assessment”. Fifth ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

Google Scholar

Hafner, H., Van der Heiden, W. (1997). Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatry 42 (2), 139–151. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200204

Hsiao, R., McClellan, J. (2008). Substance abuse in early onset psychotic disorders. J. Dual Diagn. 4 (1), 87–99. doi: 10.1300/J374v04n01_06

Hsieh, S., Schubert, S., Hoon, C., Mioshi, E., Hodges, J. R. (2013). Validation of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr. Cognit. Disord. 36 (3-4), 242–250. doi: 10.1159/000351671

Immonen, J., Jaaskelainen, E., Korpela, H., Miettunen, J. (2017). Age at onset and the outcomes of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry 11 (6), 453–460. doi: 10.1111/eip.12412

Kao, Y. C., Liu, Y. P. (2010). Effects of age of onset on clinical characteristics in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry 10, 63. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-63

Kirkpatrick, B., Buchanan, R. W., Ross, D. E., Carpenter, J. (2001). A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58 (2), 165–1671. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.165

Klosterkotter, J., Schultze-Lutter, F., Bechdolf, A., Ruhrmann, S. (2011). Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry 10 (3), 165–174. doi: 10.1007/s00406-018-0869-3

Krause, M., Zhu, Y., Huhn, M., Schneider-Thoma, J., Bighelli, I., Nikolakopoulou, A., et al. (2018). Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 268 (7), 625–639. doi: 10.1007/s00406-018-0869-3

Lehman, A. F., Lieberman, J. A., Dixon, L. B., McGlashan, T. H., Miller, A. L., Perkins, D. O., et al. (2010). “Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia”, 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association. Avaialble at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf .

Leucht, S., Kane, J. M., Kissling, W., Hamann, J., Etschel, E., Engel, R. R. (2005). What does the PANSS mean? Schizophr. Res. 79 (2-3), 231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.008

Leucht, S., Corves, C., Arbter, D., Engel, R. R., Li, C., Davis, J. M. (2009). Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 373 (9657), 31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X

Marder, S. R., Galderisi, S. (2017). The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry 16 (1), 14–24. doi: 10.1002/wps.20385

McGuffin, P. (2004). Nature and nurture interplay: schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Prax 31 Suppl 2, S189–S193. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-834565

Millan, M. J., Fone, K., Steckler, T., Horan, W. P. (2014). Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical characteristics, pathophysiological substrates, experimental models and prospects for improved treatment. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24 (5), 645–692. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.03.008

Mucci, A., Merlotti, E., Ucok, A., Aleman, A., Galderisi, S. (2017). Primary and persistent negative symptoms: Concepts, assessments and neurobiological bases. Schizophr. Res. 186, 19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.014

Murru, A., Carpiniello, B. (2018). Duration of untreated illness as a key to early intervention in schizophrenia: A review. Neurosci. Lett. 669, 59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.003

Nemeth, G., Laszlovszky, I., Czobor, P., Szalai, E., Szatmari, B., Harsanyi, J., et al. (2017). Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 389 (10074), 1103–1113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30060-0

Olie, J. P., Spina, E., Murray, S., Yang, R. (2006). Ziprasidone and amisulpride effectively treat negative symptoms of schizophrenia: results of a 12-week, double-blind study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 21 (3), 143–151. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000182121.59296.70

Penttila, M., Jaaskelainen, E., Hirvonen, N., Isohanni, M., Miettunen, J. (2014). Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 205 (2), 88–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127753

Perkins, D. O., Gu, H., Boteva, K., Lieberman, J. A. (2005). Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 162 (10), 1785–1804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785

Rabinowitz, J., Werbeloff, N., Caers, I., Mandel, F. S., Stauffer, V., Menard, F., et al. (2013). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia–the remarkable impact of inclusion definitions in clinical trials and their consequences. Schizophr. Res. 150 (2-3), 334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.023

Riedel, M., Muller, N., Strassnig, M., Spellmann, I., Engel, R. R., Musil, R., et al. (2005). Quetiapine has equivalent efficacy and superior tolerability to risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 255 (6), 432–437. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0622-6

Russell, ,. A. T. (1994). The Clinical Presentation of Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 20 (4), 631–646. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.4.631

Stahl, S. M. (2003). Describing an atypical antipsychotic: Receptor binding and its role in pathophysiology. Prim Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 5 (Suppl 3), 9–13.

Stahl, S. M. (2016). Mechanism of action of cariprazine. CNS Spectr. 21 (2), 123–127. doi: 10.1017/S1092852916000043

Veerman, S. R. T., Schulte, P. F. J., de Haan, L. (2017). Treatment for Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review. Drugs 77 (13), 1423–1459. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0789-y

Keywords: cariprazine, schizophrenia, negative symptoms, early-onset schizophrenia, second-generation antipsychotic

Citation: Molnar MJ, Jimoh IJ, Zeke H, Palásti Á and Fedor M (2020) Early-Onset Schizophrenia With Predominantly Negative Symptoms: A Case Study of a Drug-Naive Female Patient Treated With Cariprazine. Front. Pharmacol. 11:477. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00477

Received: 24 October 2019; Accepted: 26 March 2020; Published: 23 April 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Molnar, Jimoh, Zeke, Palásti and Fedor. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Judit Molnar, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Physiother Can

- v.62(4); Fall 2010

Language: English | French

Case Report: Schizophrenia Discovered during the Patient Interview in a Man with Shoulder Pain Referred for Physical Therapy

Purpose: The purpose of this case report is to demonstrate the importance of a thorough patient interview. The case involves a man referred for physical therapy for a musculoskeletal dysfunction; during the patient interview, a psychiatric disorder was recognized that was later identified as schizophrenia. A secondary purpose is to educate physical therapists on the recognizable signs and symptoms of schizophrenia.

Client description: A 19-year-old male patient with chronic shoulder, elbow, and wrist pain was referred for physical therapy. During the interview, the patient reported that he was receiving signals from an electronic device implanted in his body.

Measures and outcome: The physical therapist's initial assessment identified a disorder requiring medical referral. Further management of the patient's musculoskeletal dysfunction was not appropriate at this time.

Intervention: The patient was referred for further medical investigation, as he was demonstrating signs suggestive of a psychiatric disorder. The patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia by a psychiatrist and was prescribed Risperdal.

Implications: This case study reinforces the importance of a thorough patient interview by physical therapists to rule out non-musculoskeletal disorders. Patients seeking neuromusculoskeletal assessment and treatment may have undiagnosed primary or secondary psychiatric disorders that require recognition by physical therapists and possible medical referral.

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : L'objectif de cette étude de cas consiste à démontrer l'importance de réaliser des entrevues en profondeur avec les patients. Le cas étudié concerne un homme dirigé vers la physiothérapie en raison d'une dysfonction musculosquelettique. Au cours de l'entrevue avec ce patient, un problème psychiatrique a été décelé; par la suite, de la schizophrénie a été diagnostiquée. Le deuxième objectif de cette étude de cas est d'éduquer et de sensibiliser les physiothérapeutes aux signes et aux symptômes aisément reconnaissables de la schizophrénie.

Description du client : Le patient est un jeune homme de 19 ans qui souffre de douleurs chroniques à l'épaule, au coude et au poignet et qui avait été dirigé en physiothérapie. Au cours de l'entrevue, le patient a déclaré qu'il recevait des signaux provenant d'un appareil électronique implanté dans son corps.

Mesures et résultats : L'évaluation préliminaire du physiothérapeute a permis d'identifier un problème qui nécessitait que le patient soit redirigé vers un médecin. Une gestion plus poussée de la dysfonction musculosquelettique de ce patient a été jugée inappropriée à cette étape.

Intervention : Le patient a été dirigé vers une investigation médicale plus approfondie, puisqu'il manifestait des signes de possibles problèmes psychiatriques. Le patient a par la suite été diagnostiqué comme schizophrène et on lui a prescrit du Risperdal.

Implication : Cette étude de cas vient réaffirmer l'importance, pour le physiothérapeute, de procéder à des entrevues approfondies avec les patients pour s'assurer qu'il n'y a pas d'autres problèmes que les seules dysfonctions musculosquelettiques. Les patients qui souhaitent obtenir une évaluation et un traitement musculosquelettique peuvent souffrir aussi d'un problème psychiatrique primaire ou secondaire non diagnostiqué qui exige d'être reconnu par le physiothérapeute et qui nécessitera vraisemblablement une attention médicale ultérieure.

INTRODUCTION

A recent US study demonstrated that less than one-third of diagnoses provided to physical therapists by primary-care physicians are specific. 1 The same study illustrated that physical therapists must assume a greater diagnostic role and must routinely provide medical screening and differential diagnosis of pathology during the examination. 1 Similarly, studies conducted in Australia and Canada have concluded that the majority of referrals for physical therapy are not provided with a specific diagnosis. 2 , 3 Medical screening is important, since physical therapists are increasingly functioning as the primary contact for patients with neuromusculoskeletal dysfunctions, 4 , 5 which means a greater likelihood of encountering patients with non-musculoskeletal disorders, including psychiatric disorders.

As demonstrated by the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, it is imperative to take an individual's psychological state into account, since disorders in this area can lead to disability. 6 Many psychiatric conditions are commonly encountered in physical therapy practice; for example, depression, anxiety, and fear-avoidance have all been associated with low back, neck, and widespread musculoskeletal pain. 7 – 9 These psychiatric disorders have been identified both as risk factors for musculoskeletal dysfunction and as an important secondary psychosocial aspect of disablement. 7 – 10 It is therefore important for physical therapists to consider the primary and secondary roles of psychopathology in disability.

Although various models of primary-care physical therapy have demonstrated physical therapists' expertise in the realm of neuromusculoskeletal dysfunctions, there is a need for increased competencies in academic, clinical, and affective domains. 5 Few et al. propose a hypothesis-oriented algorithm for symptom-based diagnosis through which physical therapists can arrive at a diagnostic impression. 11 This algorithm takes into account the various causes of pathology, including psychogenic disorders. 11 Although additional research is necessary to validate Few et al.'s algorithm, it provides one model that considers underlying pathologies in determining the appropriateness of physical therapy intervention. 11 The present case report further illustrates the importance of considering the patient's affective and psychological state in order to more effectively screen for and identify psychiatric disorders that require medical referral.

The purpose of this case report is to demonstrate the importance of a thorough patient interview. We present the case of a man, referred for physical therapy for a musculoskeletal dysfunction, who was determined during the patient interview to have an undiagnosed psychiatric disorder, later identified as schizophrenia. In addition, this report is intended to educate physical therapists about the recognizable signs and symptoms of schizophrenia.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient was a 19-year-old male university student. His recreational activities included skateboarding, snowboarding, break dancing, and weight training. The patient first sought medical attention from a sport medicine physician in January 2006, when he reported right lateral wrist pain since falling and hitting the ulnar aspect of his wrist while skateboarding in October 2005. Plain film radiographs taken after the injury were negative, and the patient did not receive any treatment. The physician found no wrist swelling, minimal tenderness over the ulnar aspect of the right wrist, full functional strength, and minimally restricted range of motion (ROM). The patient was given ROM exercises and was diagnosed with a right wrist contusion.

Over the next 22 months, the patient returned to the same sport medicine clinic 10 times, reporting pain in his wrist, shoulder, elbow, knee, ankle, and neck. He stated that the elbow, wrist, and shoulder injuries were due to falls while skateboarding and snowboarding or to overuse during weight training; some injuries had no apparent cause. Over the course of his medical care, the patient followed up with three different physicians at the same clinic. He was diagnosed by these physicians, in order of occurrence, with (1) right wrist contusion and sprain; (2) right wrist impingement and left wrist strain; (3) right shoulder supraspinatus tendinopathy; (4) right peroneal overuse injury and strain; (5) disuse adhesions of the right peroneals and right hip adhesions; (6) right ankle neuropathic pain secondary to nerve injury and sprain and right-knee patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS); (7) neuropathic pain of the right peroneal nerve; (8) trauma-induced left-knee PFPS; (9) ongoing post-traumatic left-knee PFPS; and (10) right levator scapula strain, chronic right infraspinatus strain, right elbow ulnar ridge contusion, and right wrist chronic distal ulnar impingement secondary to malaligned triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC).

After his tenth visit to a physician, the patient was referred for physical therapy for chronic right levator scapula strain and right supraspinatus strain. During the interview, the patient stated that he had right shoulder pain because of a snowboarding injury sustained 1 year earlier and because of a fall onto the lateral right shoulder 2 years ago. Aggravating activities to the shoulder included pull-ups, rowing, and free weights. No position or movement alleviated his pain, and the pain did not fluctuate over the course of the day. His sleep was disturbed only when lying on the right shoulder. The patient was in generally good health, but he said that his right wrist and left knee occasionally felt cold for no apparent reason. He denied experiencing any loss of sensation, decreased blood flow, or numbness or tingling in the knee and wrist. The patient said he believed that his knee and wrist became cold as a result of electromagnetic impulses sent to the joint via an electrical implant in his body and that this device was the cause of his ongoing shoulder pain.

According to the patient, this device had been implanted into his body 2 years earlier by a government organization (the Central Intelligence Agency, the US government, or the US Army) to control his actions. Electromagnetic impulses generated by the implant had caused his falls and injuries; they also caused his joints to become cold or painful when he was doing something “they” did not want him to do, such as break dancing, snowboarding, skateboarding, or exercising. The patient also believed that many other people unknowingly had implants; he claimed that friends, neighbours, professors, and strangers were “working with them” and that they “emotionally abuse[d]” him by giving signs such as kicking a leg back to let him know he was being watched. Furthermore, he indicated that he often received commands telling him to harm his friends or family and that these orders came either from the electrical implant or from the people he claimed were emotionally abusing him. He therefore distanced himself from some friends because he did not want to follow through with these commands. I asked the patient if he felt he would harm himself or others because of his psychotic-like symptoms. He denied any desire to inflict harm on himself or others. Had he posed a threat to himself or others, he would have been “formed” (i.e., committed to a psychiatric facility by the appropriate medical professional).

The patient's past medical and family history were unremarkable. He did not use any prescription or over-the-counter medications, but he felt his thoughts about electrical implants were decreased by the use of marijuana, which he used socially. He was a non-smoker and a social consumer of alcohol. He had a normal gait and appeared comfortable in an unsupported seated position. He denied any weight changes, bowel or bladder problems, night pain, or difficulty breathing.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The patient reported a maximum verbal numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) score of 8/10 and a minimum score of 0/10, with pain usually present in the shoulder. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre chronic pain study, when the baseline NPRS raw score fluctuated by 0 points, the sensitivity and specificity were 95.32% and 31.80% respectively; 12 , 13 when there was a 4-point raw score change, the sensitivity and specificity were 35.92% and 96.92% respectively. 12 The patient stated that when he experienced shoulder pain, it was located on the anterior, posterior, and lateral aspects of his shoulder and radiated down to his elbow and wrist. He reported 0/10 shoulder pain while seated.

Standing posture was assessed in the frontal and sagittal planes. 14 The patient had a mild forward head posture and internally rotated glenohumeral joints in the sagittal plane. The frontal-plane analysis revealed a slight elevation of the right shoulder and level iliac crests. Such visual assessment of cervical and lumbar lordosis has an intrarater reliability of k =0.50 but an interrater reliability of k =0.16. 15

In the frontal plane, the right scapula was abducted four finger-widths from the mid-thoracic spine, and the left scapula was abducted three finger-widths. The scapulas were superiorly rotated bilaterally. Surface palpation of the acromial angle, inferior angle, and spine of the scapula differed less than 0.98 cm, 0.46 cm, and 0.67 cm, respectively, from the actual bony location, with a 95% confidence interval. 16 There was visible hypertrophy of the pectoralis major muscle bilaterally. Active and passive ROM were tested for the shoulders as recommended by Magee. 14 The patient had full bilateral active ROM, with minimal pain at end-range flexion and abduction that was not increased with overpressure in accordance with Magee. 14 He had full passive ROM with no pain reported.

Manual muscle testing based on Hislop and Montgomery revealed 4/5 strength of external rotation at 0° and 45° of abduction, with pain reported along the anterolateral shoulder. 17 Testing also showed 3/5 strength and no pain with resisted abduction with the arm at the side at approximately 30° of abduction. 18 Manual muscle testing is a useful clinical assessment tool, although a recent literature review suggested that further testing is required for scientific validation. 18 Palpation of the shoulder, as described by Hoppenfeld, revealed slight tenderness over the greater tubercle, as well as along the length of the levator scapula muscle. 19

Special tests were negative for the sulcus sign, Speed's test, the drop arm test, and the empty can test, as described by Magee. 14 Research shows that Speed's test has a sensitivity and specificity of 32% and 61% for biceps and labral pathology respectively; 20 the drop arm test has a sensitivity of 27% and a specificity of 88% as a specific test for rotator cuff tears, and the empty can test has a sensitivity of 44% and a specificity of 90% in diagnosing complete or partial rotator cuff tears. 20 , 21 The Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement tests were both negative. 14 According to a meta-analysis by Hegedus et al., the Neer test is 79% sensitive and 53% specific, while the Hawkins-Kennedy test is 79% sensitive and 59% specific, for impingement. 21

I (NS) diagnosed the patient with mild supraspinatus tendinosis, with no evidence of tearing of the rotator cuff muscles, based on the following findings drawn from the patient interview: shoulder pain aggravated by pull-ups, rowing, and free weights; increased pain when lying on the affected shoulder. Additional significant findings from the physical examination included full shoulder active ROM with minimal pain at end-range flexion and abduction; pain along the anterior lateral shoulder with resisted testing of external rotation at 0° and 45° of abduction; negative drop arm and empty can tests; and tenderness over the greater tubercle of the humerus. The musculoskeletal dysfunction did not explain the level of pain reported by the patient (maximum NPRS 8/10), nor was the physical examination able to reproduce the exact location of the reported shoulder pain or the elbow, wrist, and knee pain described by the patient.