15 Steps to Good Research

- Define and articulate a research question (formulate a research hypothesis). How to Write a Thesis Statement (Indiana University)

- Identify possible sources of information in many types and formats. Georgetown University Library's Research & Course Guides

- Judge the scope of the project.

- Reevaluate the research question based on the nature and extent of information available and the parameters of the research project.

- Select the most appropriate investigative methods (surveys, interviews, experiments) and research tools (periodical indexes, databases, websites).

- Plan the research project. Writing Anxiety (UNC-Chapel Hill) Strategies for Academic Writing (SUNY Empire State College)

- Retrieve information using a variety of methods (draw on a repertoire of skills).

- Refine the search strategy as necessary.

- Write and organize useful notes and keep track of sources. Taking Notes from Research Reading (University of Toronto) Use a citation manager: Zotero or Refworks

- Evaluate sources using appropriate criteria. Evaluating Internet Sources

- Synthesize, analyze and integrate information sources and prior knowledge. Georgetown University Writing Center

- Revise hypothesis as necessary.

- Use information effectively for a specific purpose.

- Understand such issues as plagiarism, ownership of information (implications of copyright to some extent), and costs of information. Georgetown University Honor Council Copyright Basics (Purdue University) How to Recognize Plagiarism: Tutorials and Tests from Indiana University

- Cite properly and give credit for sources of ideas. MLA Bibliographic Form (7th edition, 2009) MLA Bibliographic Form (8th edition, 2016) Turabian Bibliographic Form: Footnote/Endnote Turabian Bibliographic Form: Parenthetical Reference Use a citation manager: Zotero or Refworks

Adapted from the Association of Colleges and Research Libraries "Objectives for Information Literacy Instruction" , which are more complete and include outcomes. See also the broader "Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education."

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- From Research to Writing

- Academic Integrity

- Using Sources and AI

- Academic Writing

Getting Started

Research support, reading and notetaking.

- GSD Writing Services

- Grants and Fellowships

- Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

- Theses and Dissertations

Research papers are a conversation between you and other scholars. To write a successful one, you will need to hone several important skills: research, notetaking, analytical thinking, and writing.

On this page you will find resources to support each of these stages. More support is available in the library, so feel free to reach out to us if you have other questions.

- Frances Loeb Library From the library homepage, you can access all kinds of resources and tools to help with your research.

- GSD Research Guides Start your research by utilizing our curated research guides.

- Manage Your Research Find GSD-approved tools to organize and store your research.

- Ask a Design Librarian If you have a research question and don't know who to ask, submit your question here and FLL library staff will find the answer.

- Research Consultations Meet with a GSD librarian to learn more about our collections, refine your research plan, and learn strategies for locating the sources you need.

On this page you will find resources to help you on the "front end" of your writing journey. Most of these documents and sites focus on reading and notetaking strategies to help you build a research agenda and argument. Also included are a series of resources from the GSD and Harvard for productivity and time management.

Questions to ask before you start reading:

1. how much time do i have for this text.

If you have more to read than you can realistically complete in the time you have, you will need to be strategic about how to proceed. Powering through as fast as you can for as long as you can will not be efficient or effective.

2. What do I most need from this text?

Knowing your purpose will help you determine how long you should spend on any one part of that text. If you are reading for class or for research, or if you are reading for background information or to explore an argument, you will use different reading strategies.

3. How can I find what I need from this text?

Once you know what you need, there are strategies for finding it quickly, like pre-reading, skimming, and scanning.

Determining your purpose

Your purpose will become clearer if you first situate the text within a larger context.

Reading for Class

Your professor had a reason for assigning the text, so first try to understand their intention. The professor might tell you their reason or provide reading questions to direct you. You can also infer the purpose from headings and groupings in the syllabus and from how the professor has approached prior readings in past lectures. Looking ahead to how you might use the text in future assignments or projects will also help you decide how much time to spend and what to focus on.

Reading for Research

For independent research, you will first need to decide if a text is even worth reading. Plan ahead by knowing what you need, like background information, theoretical underpinnings, similar arguments to engage with critically, or images and data. Check the source's date and author(s) to determine its relevance and authority. Keep your research goals in mind and try to stay focused on your immediate goals. If you discover a text that interests you but is not for this project, make a note to come back to it later. However, a source that excites your interest and changes your research goals or argument can be worth following now so long as you still have time to make that change.

Once you decide that a source is worth your time, you will apply your choice of reading strategy based on the type of information the text contains and how you plan to use it. For instance, if you want to use a graphic or obtain biographical information, a quick search would be enough. If you want to challenge the author’s argument, you will need to read more rigorously and slowly.

- << Previous: Academic Writing

- Next: GSD Writing Services >>

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 7:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

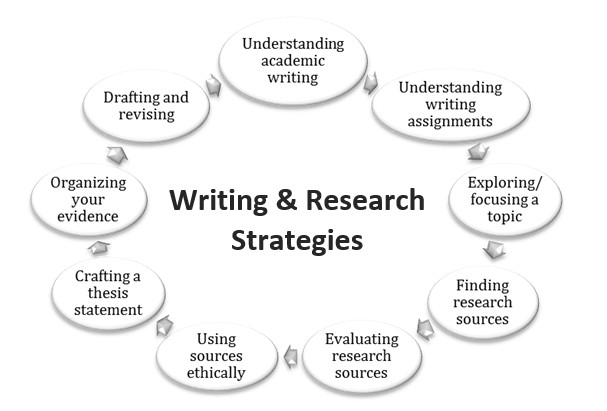

Research Process: A Step-By-Step Guide: 4d. Writing Strategies

- Getting Started

- 1a. Books and Ebooks

- 1b. Videos & Images

- 1c. Articles and Databases

- 1d. Internet Resources

- 1e. Periodical Publications

- 1f. Government and Corporate Information

- 1g. One Perfect Source?

- 2a. Know your information need

- 2b. Develop a Research Topic

- 2c. Refine a Topic

- 2d. Research Strategies: Keywords and Subject Headings

- 2e. Research Strategies: Search Strings

- 3a. The CRAAP Method

- 3b. Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- 4a. Incorporate Source Material

- 4b. Plagiarism

- 4c. Copyright, Fair Use, and Appropriation

- 4d. Writing Strategies

- 5a. MLA Formatting

- 5b. MLA Citation Examples

- 5c. APA Formatting

- 5d. APA Citation Examples

- 5e. Chicago Formatting

- 5f. Chicago Examples

- 5g. Annotated Bibliographies

- Visual Literacy

Forms of Notetaking

Use one of these notetaking forms to capture information:

- Summarize : Capture the main ideas of the source succinctly by restating them in your own words.

- Paraphrase : Restate the author's ideas in your own words.

- Quote : Copy the quotation exactly as it appears in the original source. Put quotation marks around the text and note the name of the person you are quoting.

Tips for Taking Notes by Hand

- Use index cards to keep notes and track sources used in your paper.

- Include the citation (i.e., author, title, publisher, date, page numbers, etc.) in MLA format. It will be easier to organize the sources alphabetically when creating the Work Cited page.

- Number the source cards.

- Use only one side to record a single idea, fact or quote from one source. It will be easier to rearrange them later when it comes time to organize your paper.

- Include a heading or key words at the top of the card.

- Include the Work Cited source card number.

- Include the page number where you found the information.

- Use abbreviations, acronyms, or incomplete sentences to record information to speed up the notetaking process.

- Write down only the information that answers your research questions.

- Use symbols, diagrams, charts or drawings to simplify and visualize ideas.

Example Notecard

Tips for taking notes electronically.

- Keep a separate Work Cited file of the sources you use.

- As you add sources, put them in MLA format.

- Group sources by publication type (i.e., book, article, website).

- Number source within the publication type group.

- For websites, include the URL information.

- Next to each idea, include the source number from the Work Cited file and the page number from the source. See the examples below. Note #A5 and #B2 refer to article source 5 and book source 2 from the Work Cited file.

#A5 p.35: 76.69% of the hyperlinks selected from homepage are for articles and the catalog #B2 p.76: online library guides evolved from the paper pathfinders of the 1960's

- When done taking notes, assign keywords or sub-topic headings to each idea, quote or summary.

- Use the copy and paste feature to group keywords or sub-topic ideas together.

- Back up your master list and note files frequently!

Example Work Cited Card

Why outline.

For research papers, a formal outline can help you keep track of large amounts of information.

How to Create an Outline

To create an outline:

- Place your thesis statement at the beginning.

- List the major points that support your thesis. Label them in Roman Numerals (I, II, III, etc.).

- List supporting ideas or arguments for each major point. Label them in capital letters (A, B, C, etc.).

- If applicable, continue to sub-divide each supporting idea until your outline is fully developed. Label them 1, 2, 3, etc., and then a, b, c, etc.

How to Structure an Outline

Art History Research Paper Example

- Art History Research Paper Outline This is an outline for an art history comparison essay using the point-by-point or splitting structure.

Thesis: Federal regulations need to foster laws that will help protect wetlands, restore those that have been destroyed, and take measures to improve the damange from overdevelopment.

I. Nature's ecosystem

A. Loss of wetlands nationally

B. Loss of wetlands in Illinois

1. More flooding and poorer water quality

2. Lost ability to prevent floods, clean water and store water

II. Dramatic floods

A, Cost in dollars and lives

1. 13 deaths between 1988 and 1998

2. Cost of $39 million per year

B. Great Midwestern Flood of 1993

1. Lost wetlands in IL

2. Devastation in some states

C. Flood Prevention

1. Plants and Soils

2. Floodplain overflow

III. Wetland laws

A. Inadequately informed legislators

1. Watersheds

2. Interconnections in natural water systems

B. Water purification

IV. Need to save wetlands

A. New federal definition

B. Re-education about interconnectedness

1. Ecology at every grade level

2. Education for politicians and developers

3. Choices in schools and people's lives

Example taken from The Bedford Guide for College Writers (9th ed).

Writing the Paper

Writing research papers can be very challenging.

Knowing how to incorporate your research material can help.

Recommended Books

Microsoft Office Help

If not, you can also visit the Microsoft Office website. The site contains a wealth of information including how-to documents, templates, and training videos.

Recommended Websites

- The Writing Lab at the Academy Resource Center (ARC) The Academy of Art University's Center for Academic Support

- Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL) Includes resources and instructional materials to assist with a variety of writing projects.

- University of Wisconsin's Writing Center Includes instructional materials that were developed for teaching in the Writing Center.

Literature Review

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes within a certain time period. It can be a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis.

Sources included in a literature review may include: books, peer-reviewed articles, newspaper articles, videos, conference proceedings, and websites. You should only include sources that are relevant, recent and reputable.

Source: University of North Carolina's Writing Center

- Literature Review Example

- << Previous: 4c. Copyright, Fair Use, and Appropriation

- Next: 5: Citation >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 10:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.academyart.edu/research-process

- Utility Menu

de5f0c5840276572324fc6e2ece1a882

- How to Use This Site

- Core Competencies

Write Effectively

Writing, including publication, is critical to conveying science, and is often an important indicator of success in a c/t research career. Depending on the document you are writing – a grant, proposal, article, or another format – there are a variety of styles and approaches to consider. Explore the resources below to learn to write effectively and publish across several mediums.

View Core Competencies

The sections below provide strategies, organizing tips and resources to help you become a successful writer.

Writing Tips

Techniques to becoming a better writer

Publishing Your Manuscript

How to prepare for the multi-step process

Plain Language

Resources for clear communication

Looking for Grant Writing Tips?

Related courses, how to design a clinical trial: principles & protocol development.

Hybrid (online and in-person) course on the design & implementation of clinical trials

Effectively Communicating Research

An intensive course designed to provide fellows and junior faculty with the skills necessary to express their science clearly to diverse audiences. Course content covers preparing abstracts, manuscripts, and posters, and learning to speak effectively

Learn More

Introduction

This textbook will help guide you through the process of writing a college-level research paper. While there are many approaches and strategies for doing so, this textbook will divide the process into four different writing projects:

- an annotated bibliography

- a research proposal

- a literature review

- a research essay

Each of these projects is a distinct genre that you will likely encounter in different academic disciplines and professions outside of a composition classroom.

Our goal is to give you a broad sense of these genres as separate but closely connected steps in the research process. Taken together, these projects will give you a strong foundation in research writing, with an eye towards how research writing skills fit within other disciplines and professions.

We hope that this textbook and the resources it gathers will help you feel more confident about your writing as you learn the steps of the research process.

I. Guiding Principles

You will notice some specific choices and themes throughout the chapters of the book. They have informed the authors, editors, librarians, and instructors who helped assemble it. In this section, we lay out those key guiding principles.

Research is a Conversation

When we engage in research, we contribute to an existing topic or discussion. According to Joseph Moxley and Grace Veach, for centuries, scholars have imagined research and argumentative writing much like a conversation (2021). A conversation is a cooperative activity between two or more people, and each conversation is unique to the people who take part in it. Conversations can go on for hours, days, or even decades among different participants who may come and go, and those conversations develop a unique tone, history, and shared knowledge and assumptions.

An essential part of the research process involves familiarizing yourself with the conversation surrounding your topic: the key voices, facts, ideas, and conventions. As you learn more about whatever topic you research, you will enter into this conversation, refining your own voice as you determine what you will contribute to that conversation.

This is one of the guiding metaphors in composition studies and a guiding principle in this book. When we write, we engage with the ideas of others by listening to what they have said before us. After getting a clear sense of what has been said, we can add something new to the ongoing conversation by placing our ideas in relation to those who have come before us. Our contribution is not the end of the conversation, but rather part of its ongoing engagement with complex ideas and issues.

Here is a short video from the Oklahoma State University Libraries that highlights the importance of thinking about research as a conversation:

Open Access is Collaborative

This book is an Open Electronic Resource, or OER. OERs are free, open access educational materials. Whether this is a text assigned for your class or an additional resource you have sought out on your own, we are committed to keeping this material free and accessible to all. Here is a link to Creative Commons , where you can learn more about open access materials.

Not only do OERs make educational material easier to access, they also encourage collaboration among students and educators. This textbook is the product of several authors, editors, librarians, and research assistants, along with feedback from countless students and instructors.

Throughout, we have included additional OER materials linked throughout the chapters and appendices, including images, infographics, and videos. Just as the research process is joining a conversation, we see the composition classroom as a collaborative space for sharing ideas, educational materials, and writing strategies. We hope you benefit from learning alongside these resources as much as we did from incorporating them into the book.

Genres are Determined by Rhetorical Expectations

This text focuses on the genres you will be writing in your courses and key components in the process of composing them. From a sociolinguistic perspective, a “genre” is defined as a communication activity with a shared goal established prior to the event. This means that the author and audience already understand the rhetorical purpose of the text before they write or read it, even if they do not know the content. In this book, we will discuss genres that inform and document, plan and persuade, review and synthesize, debate and convince.

Each genre has a set of commonly accepted forms and structures that enact its objectives, although these will vary between communities of practice such as workplaces, academic disciplines, and cultural centers. Literature reviews in an engineering journal will look very different than literature reviews in a psychology journal, although they will share a similar purpose for their audiences and the same underlying form.

It is important to note that genres are only relatively set—as different needs arise, genres evolve to fit the new goals. Scholars have described the recognizable characteristics of genres as the “visible effects of human action” (Hart-Davidson, 2016, p. 39). This text focuses on the role and purposes of a genre, and discussions of form only point out the fundamental structures needed to enact these goals—always observe your context, ask your instructor, and look at examples of the genre within your chosen discipline for needed specifics.

Language Practices are Shaped by Discourse Communities

Like genre, language and language practices also change over time. Language preferences evolve within all communities, including academic and professional ones. We all know that we change the way we speak and write depending on our audience, and academic disciplines are no exception. Different fields of studies and professions have very different expectations about language practices.

For example, a common piece of advice offered to developing writers is to avoid using the passive voice (“a question was asked ” or “a mistake was made ”). Many teachers explain that the passive voice hides who is performing the action (who asked the question or who made the mistake). In the sciences, the passive voice might be needed for that very reason. In a lab experiment, it doesn’t matter who prepared the samples or tests, because it shouldn’t matter as long as it is done properly. You’ll likely see a lot of passive voice, like “the subjects were given …” and “the results were analyzed …,” in order to make the experiment appear as objective as possible.

For these reasons, understanding and sharing in the rhetorical practices and objectives of a community of practice can lead to mutual understanding more effectively than grammar lessons. Studies of error perception show that the kinds of errors readers notice vary widely and are highly subjective in the degree to which they affect the reader’s opinion of a writer (Boetteger & Emory-Moore, 2018; Lunsford & Lunsford, 2008). You will not find prescriptive language or grammar instruction in this text. The authors of this guide uphold all students’ rights to their own choice of language practice and growth.

Writing is Knowledge-Construction and Inquiry

Writing is the tangible demonstration of thought. We don’t just write down things we know—we write to think through problems, to organize our ideas, and to make new connections and discoveries. In other words, writing is a way to create new knowledge for ourselves and others, not just a way to show others what we already understand. This is a result of the recursive nature of the research, reading, and writing process. There is a magic to discovering that a research topic even exists, that other people are interested in the same topics as you—reading the research of others helps to give our own understanding of the world balance and depth. But many people—students, teachers, folks making grocery lists, or people leaving instructions for the dog-sitter—often find that they never understand a topic as much as they do after they have written it down.

Do not always think of your writing as a quest to write perfect sentences and paragraphs; striving to make yourself understood is well and good, but don’t forget that writing is something you also do for yourself as a learner. Writing something down can inspire new ideas that lead to new research, new reading and information accumulation—and then more writing and rewriting. A part of writing is the desire to know more, to work through the logic of a problem—to inquire . When we say “Writing is Inquiry,” we invoke a conception of writing as exploration and discovery, and the writer as explorer and detective.

Library Referral: Research Is an Ongoing Conversation

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

You’ve already heard that research is a conversation. To be clear, it’s not a single, “one and done” type of conversation; it’s more ongoing. Maybe you start the conversation with a kernel of previous knowledge on the topic. You’ve looked at Wikipedia, done a quick Google search, read an article or listened to a podcast. You know just enough to start listening to the conversation. Then you talk to someone who knows a little more than you, and you realize that there are gaps that you need to fill.

So you take your research to the next level. You write down more specific questions. You turn these questions into keywords and search for articles on more specific aspects of your topic (see the link Choosing keywords for guidance). The new batch of articles leads to new ideas. You’re starting to develop your expertise. Now you need to circle back to the conversation and share what you’ve learned, or maybe even clear up some false assumptions you made earlier on. This might seem like backtracking, but you’re doing it right! The research is reforming your knowledge base and fine-tuning your questions. It’s all priming you to have a more informed conversation.

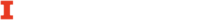

II. The Research Process

If you ask anyone what the research process is like, you’ll get different answers from each person you ask. This is because after a lot of trial and error, everyone finds a process that works especially well for them. Maybe right now you feel that you write your best work the night before it’s due, and after interacting with this book, you’ll learn that your first draft probably shouldn’t be your last. There’s really no perfect way to write other than to practice doing so. As you read through this book, look out for the various strategies and writing tips offered, and try them out to get a sense of what does and doesn’t work for you.

One thing most people will agree on is that research takes time ! For this reason, you’ll want to set goals for your writing and keep in mind that you may have to repeat steps multiple times. For example, you may decide to revisit sources throughout your research process. When you reread these sources, keep in mind that your thesis may have altered since you last read it, and your new task is to reread it with an open mind and new goals. Give yourself time to reread sources and to decide whether they’re still relevant to your work. And keep in mind that you will always have something to read—whether that be a source or your own paper when you’re making revisions.

Also, keep in mind that you’re always rereading and revising your own writing. The four writing projects described throughout the book are meant to build off one another, so you may find yourself repeating a lot of information or rephrasing in a new way. Although this can be a bit frustrating at times, think about each project like a conversation with a person who’s just not seeing your point. It’s crucial and even helpful to repeat yourself so that you can help them see your stance clearly.

Citing throughout your project is also helpful to your reader, so that they can know where your thoughts are coming from and who you’re in conversation with. Citing can take some time, so try your best to figure out whether you prefer citing as you work or leaving it as a final step. However, as you’ll see throughout this book, citing is a must across all the disciplines. Not only does it show that you know what you’re talking about, based on your own research, but it also shows that you know how to join a conversation and acknowledge other people at the table. Keep in mind that citing also helps you avoid plagiarizing someone else’s or your own work. At whichever stage of the writing process you decide to cite, leave little reminders for yourself so that you don’t forget!

As you’ll soon see, research is very messy, redundant, and technical. But it can also be very rewarding and fun to follow your thoughts into research, discover what you have to say, and consider who needs to hear it. Remember not to get lost in the recursiveness of the process, but instead to immerse yourself in it. You’ll soon learn that the strategies and moves you make in academic writing can benefit you across all the disciplines.

How to Use Sources

Evaluating the reliability of sources can be a sticky process. In this book, we address and then move beyond the simple “reliable versus unreliable” binary. We encourage you to start by asking yourself how you will use the source and for what purpose.

Are you looking for a source you can use to build a logical argument about the need for the COVID-19 vaccination or boosters, for example? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, which contains information written by scientists and physicians, would be an appropriate source for scientific expertise. Or are you looking for examples of how celebrities influence their followers when it comes to understanding the vaccine? Then you might want to look at Nicki Minaj’s tweet of Sept. 13th, 2021, and analyze that—not as if Minaj were a scientist who had studied infectious diseases and vaccines, but as a celebrity who has the power to quickly share her ideas with a large audience and who, it turns out, circulated inaccurate information.

This might lead you to ask a larger question about how cults of personality limit critical thinking. In that case, although the tweet itself contains inaccurate information and could be considered unreliable, you might still use it in your paper as a source. You could analyze the tweet (and the flurry of responses by fans, reporters, and government officials) as part of the larger discourse around the circulation of vaccine (dis)information. Throughout the book, we’ll ask you to think about your sources like this: not just is it reliable, but in what ways can a source be put to use?

In this text, we envision research as a conversation because it encourages you to find sources that speak to you and allow you to develop ideas that will eventually become the basis for your thesis. In other words, your job as a researcher is much more interesting and rigorous than merely gathering and presenting information. Research should not be limited to asserting your opinion and then finding evidence to support it; that’s a monologue rather than a conversation. Engaging in research as a conversation means that the sources you find inform your views. That is, you allow sources–those you consider reliably written by authorities on the subject—to modify your position.

The recursive nature of drafting and revising your writing works much the same way. Thus, you draft an assignment, participate in peer review in class, and/or take your draft to your local writing center to get feedback. Then you revise your draft because your partner’s comments and observations inform your essay. Then, perhaps, your instructor comments on your draft, which once again informs your position, and you revise.

You may repeat any number of these processes from getting peer or instructor feedback, rewriting, and researching. Repeating these steps is more common in advanced academic research and professional writing. Researchers may get feedback from colleagues or at conferences and revise their work before trying to publish it. Writers in all types of professions may need their work reviewed by team members, supervisors, technical editors, or lawyers in order to make sure they are achieving their goal.

Library Referral: Library Help

Libraries aren’t just buildings that give you access to books and articles. They house a range of employees—including librarians—who are paid to help you with any and every aspect of the research process. As a librarian myself, I spend many more hours meeting with students on Zoom, teaching research classes, and answering questions on chat and online than I do just handling books.

Talking to students about their research is what makes my job fun and interesting. Seek us out at any point of the research process: at the beginning, when you’re mulling over your topic; in the middle, when you’re starting to find sources; and towards the end, when you’re looking for more sources to fill in the gaps in your research or you need help with citations.

We don’t expect you to come to us at any particular stage of “readiness”; we’re trained to meet you where you are and figure out what might be most relevant for your research needs. We want to help make your research experience as painless and productive as we can. Most libraries offer research help both online and in person.

III. Overview of the Book

The rest of the book is divided into four chapters, one for each genre. In chapter one, you will learn about the annotated bibliography, where you will start your research and record some of your insights about the first sources you read. Chapters two and three are interchangeable: some instructors may have you switch the order of these writing projects. In chapter two, you will write a proposal, where you outline your plan to research your topic, identifying questions to ask and areas to explore. In chapter three, you will write a literature review, where you provide an overview of the main ideas, controversies, and conversations surrounding your topic.

After you have completed these three writing projects, you will have a good sense of your topic and should feel much more confident to add your own voice to the conversation by writing an argument-driven research essay. The final chapter provides strategies for structuring your argument and organizing your research for your essay. Three appendices are included at the end, with additional resources for writing, reading, and research strategies.

Each chapter has a similar structure. It provides sections that help familiarize you with the genre of each writing project:

- Rhetorical Consideratio ns spotlight aspects of the genre that may need specific attention.

- The Genre Across the Disciplines provides real examples of the genre as you might encounter it later in your academic or professional career.

- Research Strategies highlight parts of the research process essential to your writing project.

- Reading Strategies help you navigate the often-difficult texts you might encounter in your research, as well as help you think about how those texts might be put to use in your project.

- Writing Strategies offer different ways to help facilitate the writing process, giving advice about issues writers of all levels grapple with.

- Librarian Referrals give you practical advice from research librarians to help you find and evaluate sources (you’ve already seen a couple in this chapter).

- More Resources provide additional OER materials within the text to help you throughout the research and writing process. Additional OER materials can also be found in the appendices.

If you’ve never written a long research paper before, don’t worry. We’ll help guide you throughout the entire process. By the end of this book, you will be well-versed in your research topic. Whether you are still trying to find a topic to research or have a good idea of what you want to write about, this book will guide you through the research process and build confidence in your ability as a writer.

Boettger, R. & Emory-Moore, L. (2018). Analyzing error perception and recognition among professional communication practitioners and academics. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 462–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490618803740

Hart-Davidson, B. (2015). Genres are enacted by writers and readers. In Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. (Eds.), Naming what we know : Threshold concepts of writing studies . (Classroom edition, pp. 39-40). Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Lunsford, A. & Lunsford, K. J. (2008). “Mistakes are a fact of life”: A national comparative study. College Composition and Communication , 59(4), 781–806.

Moxley, J. & Veach, G. (2021). “Scholarship as a Conversation.” Writing Commons. https://writingcommons.org/section/information-literacy/information-literacy-perspectives-practices/scholarship-as-a-conversation/

“Inform Your Thinking Episode 1: Research is a conversation.” (2016). Oklahoma State University. YouTube . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DmbO3JX5xvU

Writing for Inquiry and Research Copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey Kessler, Mark Bennett, and Sarah Primeau is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing for Inquiry and Research

(3 reviews)

Jeffrey Kessler, University of Illinois Chicago

Mark Bennett, University of Illinois Chicago

Sarah Primeau, University of Illinois Chicago

Charitianne Williams, University of Illinois Chicago

Virginia Costello, University of Illinois Chicago

Annie R. Armstrong, University of Illinois Chicago

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9781946011213

Publisher: University of Illinois Library - Urbana

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Jason Parks, Professor of English, Anderson University on 9/1/24

While the introduction cited four specific writing projects covered in this book: an annotated bibliography, a research proposal, a literature review, and a research essay, the appendices and extra material at the end of each chapter provides even... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

While the introduction cited four specific writing projects covered in this book: an annotated bibliography, a research proposal, a literature review, and a research essay, the appendices and extra material at the end of each chapter provides even more than you might expect. I was immediately copying links and bookmarking pages once I read through each chapter. I would definitely use this in a first-year writing course.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Everything is clear, up to date, and unbiased. This was clearly put together by experts who understand the practical needs of college students.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

Everything in this book is recent and applicable to students currently (Fall 2024) writing research papers. There's even some discussion of AI, though updates will be needed as we continue to figure out how to integrate new technologies into approaches to writing instruction.

Clarity rating: 5

Everything is succinct and direct. Any jargon that is used (such as metadiscourse), includes videos and explanations. The videos are especially helpful in clarifying terms.

Consistency rating: 5

Everything is cohesive and consistent in terms of framework. While each chapter has a different focus, they all work together and point toward the same objectives of helping students make sense of the research and writing process.

Modularity rating: 4

Everything is well-organized and headings are clear. The videos were easy to access and all the links were well marked. I especially liked the additional sections at the end of the chapters that linked to more textbooks and writing center resources.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Each chapter guides students through the process of compositing/creating a specific project. There were plenty of breaks between sections with charts, diagrams, and videos.

Interface rating: 5

The text was all consistent in terms of font, headings, and visuals. There were no complicated interfaces, mostly just simple scrolling through the information.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

Everything was professionally edited and clearly written.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The text was very neutral. The examples were not limited to and didn't favor any specific background, race, or ethnicity. The video links and other topics raised in the examples had plenty of variety.

I was especially impressed with the efficiency and level of expertise. Each chapter was paired down to key points and useful tips that are relevant to current research on first-year writing programs. I thought the videos were all helpful and easy to access. I also appreciated the extra links at the end of each chapter. I will definitely be using this in my first-year research courses this semester. There was only one link to the following OER resource that didn't work: Writing a Research Paper, A Potential Method for Jerry Rhodes, "The Main Steps of Research Paper Writing". Otherwise, you could share this with students right now. If I was going to write my own textbook for an introductory research course, this is definitely the kind of book I'd want to write. After 17 years of teaching first-year composition and research, I've seen the full range of first-year research and rhetoric textbooks, and I feel like this is the kind of resource that we need, although you'd definitely want to pair this with your own examples and materials, especially if you have specific themes and/or objectives for your classes. It's not prescriptive and is useful as guide/handbook for any of the individual projects, so the chapters can definitely be used separately.

Reviewed by Terry Lovern, Adjunct Instructor, Radford University on 5/27/24

The book is quite comprehensive, showcasing the experience from all the authors. The authors' interdisciplinary approach works well, adding to the text's depth and breadth. Incorporating explanatory videos in the sections is an excellent choice,... read more

The book is quite comprehensive, showcasing the experience from all the authors. The authors' interdisciplinary approach works well, adding to the text's depth and breadth. Incorporating explanatory videos in the sections is an excellent choice, which eliminates the need to add more tutorials via YouTube. It covers all the necessary steps for conducting and composing a research paper.

Although the authors leave out important topics like emergent digital technologies and plagiarism, they at least acknowledge those shortcomings as they advocate that writing is always a human-centric action. An instructor could easily supplement other materials to cover these missing topics though.

The authors focus on what they view as the most important, evergreen steps of research writing. This approach will help the text endure over time as opposed to needed constant updates for things like digital media. Technology could be supplemented with other OER texts or by the instructor.

The book is clear and concise. First-year students and instructors alike should have no problem following the text due to its well organized content.

The book has no consistency problems. The authors use a simple, easy to follow organization of topics; their accumulated experience with first-year writing keeps the content consistent.

Modularity rating: 5

The authors do an excellent job of breaking the research writing process into easy to use sections. Assigning them out of order in class would be confusing; however, an instructor could spend a week or longer on a chapter, adding anything else they feel is necessary.

Excellent organization. Each section is distinct and separate, but shows how the entire research process is connected and scaffolded. The appendices are also laid out well and organized.

No interface issues or problems with the text itself.

No discernible surface errors are in the text.

The book is fairly neutral, so any first-year student or instructor should be able to use it. The text contains nothing culturally insensitive or offensive and focuses on how to do research writing.

This would make a great text for anyone teaching the research writing component of first-year composition. The step-by-step structure makes it easy to scaffold and incorporate into a syllabus schedule. The book would also be excellent for mentoring TA's who are learning to teach the material and for new instructors who might want more structure to their course plans.

Reviewed by Angelica Rivera, Director, Northeastern Illinois University on 4/16/24

This book consists of a Preface, Introduction, Chapters I thru Chapter IV. and it also has an Appendix I to Appendix III. Chapter I covers the Annotated Bibliography, Chapter II covers the Proposal, Chapter III covers the Literature Review and... read more

This book consists of a Preface, Introduction, Chapters I thru Chapter IV. and it also has an Appendix I to Appendix III. Chapter I covers the Annotated Bibliography, Chapter II covers the Proposal, Chapter III covers the Literature Review and Chapter IV covers the Research Essay. Each section is broken down into smaller sections to break down each topic. The book is written by 3 different authors who are experts in their field and who write about different writing genres. The authors are interdisciplinary in their approach which means students in various disciplines can use the manual to begin their inquiry process and continue with their research process. This book also has short videos that provide explanations, and references after every chapter to provide additional learning resources. Appendix I covers Reading Strategies, Appendix II covers Writing Strategies and Appendix III covers Research Strategies. Appendix I and Appendix II also have additional resources for reading and writing strategies. This book will help most first year students who are transitioning from high school to college.

This book is accessible for first year students who are in English, Composition or First year experience courses. However, the authors note that there are some limits to the topics addressed as the text does not cover research methods, databases, plagiarism and emerging writing technologies. The authors believe that writing is a human based process regardless of the tools and technologies that one uses when writing.

This book is well researched and will survive the test of time as it is accessible and will serve as a reference tool for a student who is looking to develop their writing question and develop their research approach.

This book is well researched, well organized and well written.

There was consistency throughout the text as all of the authors had experience with working with first year students and/or with the writing process.

The first 3 chapters can be assigned in any order but the fourth chapter should be the 4th step as that part consists of writing the actual research essay. This book is not meant to be used by itself and thus provides additional bibliographic sources and topics to further develop one’s knowledge of the writing process.

This book is written in the logical process of developing a research question and then conducting the research. An instructor can easily assign these chapters in chronological order and it will help the student to brainstorm to create their question and then follow the steps to conduct their research.

There were no issues with the books interface.

I found this manuscript to be well written and it contained no visible grammatical errors.

I found this book to be neutral and accessible to all students irrespective of their various backgrounds.

I give this book 5 stars because it helps students and instructors break down the research process into smaller steps which can be completed in a semester-long course in research writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Annotated Bibliography

- Chapter 2: Proposal

- Chapter 3: Literature Review

- Chapter 4: Research Essay

- Appendix I: Writing Strategies

- Appendix II: Reading Strategies

- Appendix III: Research Strategies

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Writing for Inquiry and Research guides students through the composition process of writing a research paper. The book divides this process into four chapters that each focus on a genre connected to research writing: the annotated bibliography, proposal, literature review, and research essay. Each chapter provides significant guidance with reading, writing, and research strategies, along with significant examples and links to external resources. This book serves to help students and instructors with a writing-project-based approach, transforming the research process into an accessible series of smaller, more attainable steps for a semester-long course in research writing. Additional resources throughout the book, as well as in three appendices, allow for students and instructors to explore the many facets of the writing process together.

About the Contributors

Jeffrey C. Kessler is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago. His research and teaching interrogate the intersections of writing, fiction, and critical university studies. He has published about the works of Oscar Wilde, Henry James, Vernon Lee, and Walter Pater. He earned his PhD from Indiana University.

Mark Bennett has served as director of the University of Illinois Chicago’s (UIC) First-Year Writing Program since 2012. He earned his PhD in English from UIC in 2013. His primary research interests are in composition studies and rhetoric, with a focus on writing program administration, course placement, outcomes assessment, international student education, and AI writing.

Sarah Primeau serves as the associate director of the First-Year Writing Program and teaches first-year writing classes at University of Illinois Chicago. Sarah has presented her work at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the Council of Writing Program Administrators Conference, and the Cultural Rhetorics Conference. She holds a PhD in Rhetoric and Composition from Wayne State University, where she focused on composition pedagogy, cultural rhetorics, writing assessment, and writing program administration.

Charitianne Williams is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago focused on teaching first-year composition and writing center studies. When she’s not teaching or thinking about teaching, she’s thinking about writing.

For more than twenty years, Virginia Costello has been teaching a variety of English composition, literature, and gender studies courses. She received her Ph.D. from Stony Brook University in 2010 and is presently Senior Lecturer in the Department of English at University of Illinois Chicago. Early in her career, she studied anarcho-catholicism through the work of Dorothy Day and The Catholic Worker Movement. She completed research at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and has published articles on T.S. Eliot, Emma Goldman, and Bernard Shaw. More recently, she presented her work at the Modern Studies Association conference (Portland, OR, 2022), Conference on College Composition and Communication (Chicago, Il, 2023) and Comparative and Continental Philosophy Circle (Tallinn, Estonia, 2022 and Bogotá, Columbia, 2023). Her research interests include prison reform/abolition, archē in anarchism, and Zen Buddhism.

Annie Armstrong has been a reference and instruction librarian at the Richard J. Daley Library at the University of Illinois Chicago since 2000 and has served as the Coordinator of Teaching & Learning Services since 2007. She serves as the library’s liaison to the College of Education and the Department of Psychology. Her research focuses on enhancing and streamlining the research experience of academic library users through in-person and online information literacy instruction.

Contribute to this Page

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

A Beginner's Guide to Starting the Research Process

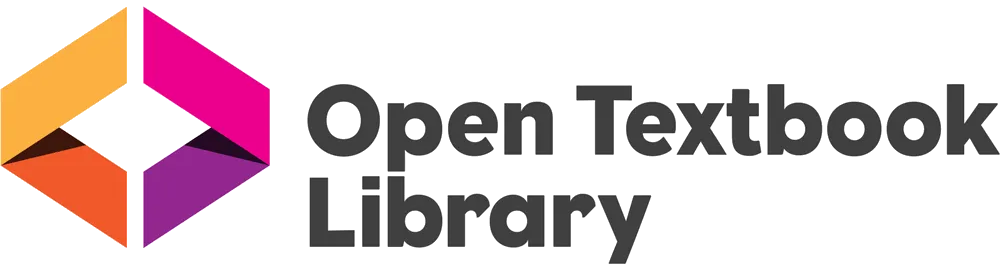

When you have to write a thesis or dissertation , it can be hard to know where to begin, but there are some clear steps you can follow.

The research process often begins with a very broad idea for a topic you’d like to know more about. You do some preliminary research to identify a problem . After refining your research questions , you can lay out the foundations of your research design , leading to a proposal that outlines your ideas and plans.

This article takes you through the first steps of the research process, helping you narrow down your ideas and build up a strong foundation for your research project.

Table of contents

Step 1: choose your topic, step 2: identify a problem, step 3: formulate research questions, step 4: create a research design, step 5: write a research proposal, other interesting articles.

First you have to come up with some ideas. Your thesis or dissertation topic can start out very broad. Think about the general area or field you’re interested in—maybe you already have specific research interests based on classes you’ve taken, or maybe you had to consider your topic when applying to graduate school and writing a statement of purpose .

Even if you already have a good sense of your topic, you’ll need to read widely to build background knowledge and begin narrowing down your ideas. Conduct an initial literature review to begin gathering relevant sources. As you read, take notes and try to identify problems, questions, debates, contradictions and gaps. Your aim is to narrow down from a broad area of interest to a specific niche.

Make sure to consider the practicalities: the requirements of your programme, the amount of time you have to complete the research, and how difficult it will be to access sources and data on the topic. Before moving onto the next stage, it’s a good idea to discuss the topic with your thesis supervisor.

>>Read more about narrowing down a research topic

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

So you’ve settled on a topic and found a niche—but what exactly will your research investigate, and why does it matter? To give your project focus and purpose, you have to define a research problem .

The problem might be a practical issue—for example, a process or practice that isn’t working well, an area of concern in an organization’s performance, or a difficulty faced by a specific group of people in society.

Alternatively, you might choose to investigate a theoretical problem—for example, an underexplored phenomenon or relationship, a contradiction between different models or theories, or an unresolved debate among scholars.

To put the problem in context and set your objectives, you can write a problem statement . This describes who the problem affects, why research is needed, and how your research project will contribute to solving it.

>>Read more about defining a research problem

Next, based on the problem statement, you need to write one or more research questions . These target exactly what you want to find out. They might focus on describing, comparing, evaluating, or explaining the research problem.

A strong research question should be specific enough that you can answer it thoroughly using appropriate qualitative or quantitative research methods. It should also be complex enough to require in-depth investigation, analysis, and argument. Questions that can be answered with “yes/no” or with easily available facts are not complex enough for a thesis or dissertation.

In some types of research, at this stage you might also have to develop a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses .

>>See research question examples

The research design is a practical framework for answering your research questions. It involves making decisions about the type of data you need, the methods you’ll use to collect and analyze it, and the location and timescale of your research.

There are often many possible paths you can take to answering your questions. The decisions you make will partly be based on your priorities. For example, do you want to determine causes and effects, draw generalizable conclusions, or understand the details of a specific context?

You need to decide whether you will use primary or secondary data and qualitative or quantitative methods . You also need to determine the specific tools, procedures, and materials you’ll use to collect and analyze your data, as well as your criteria for selecting participants or sources.

>>Read more about creating a research design

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Finally, after completing these steps, you are ready to complete a research proposal . The proposal outlines the context, relevance, purpose, and plan of your research.

As well as outlining the background, problem statement, and research questions, the proposal should also include a literature review that shows how your project will fit into existing work on the topic. The research design section describes your approach and explains exactly what you will do.

You might have to get the proposal approved by your supervisor before you get started, and it will guide the process of writing your thesis or dissertation.

>>Read more about writing a research proposal

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

More interesting articles

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

- How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Fishbone Diagram? | Templates & Examples

- What Is Root Cause Analysis? | Definition & Examples

Get unlimited documents corrected

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Encyclopedia for Writers

Writing with artificial intelligence, the ultimate blueprint: a research-driven deep dive into the 13 steps of the writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - Professor of English - USF

This article provides a comprehensive, research-based introduction to the major steps , or strategies , that writers work through as they endeavor to communicate with audiences . Since the 1960s, the writing process has been defined to be a series of steps , stages, or strategies. Most simply, the writing process is conceptualized as four major steps: prewriting , drafting , revising , editing . That model works really well for many occasions. Yet sometimes you'll face really challenging writing tasks that will force you to engage in additional steps, including, prewriting , inventing , drafting , collaborating , researching , planning , organizing , designing , rereading , revising , editing , proofreading , sharing or publishing . Expand your composing repertoire -- your ability to respond with authority , clarity , and persuasiveness -- by learning about the dispositions and strategies of successful, professional writers.

Table of Contents

Like water cascading to the sea, flow feels inevitable, natural, purposeful. Yet achieving flow is a state of mind that can be difficult to achieve. It requires full commitment to the believing gam e (as opposed to the doubting game ).

What are the Steps of the Writing Process?

Since the 1960s, it has been popular to describe the writing process as a series of steps or stages . For simple projects, the writing process is typically defined as four major steps:

- drafting

This simplified approach to writing is quite appropriate for many exigencies–many calls to write . Often, e.g., we might read an email quickly, write a response, and then send it: write, revise, send.

However, in the real world, for more demanding projects — especially in high-stakes workplace writing or academic writing at the high school and college level — the writing process involve additional steps, or strategies , such as

- collaboration

- researching

- proofreading

- sharing or publishing.

Related Concepts: Mindset ; Self Regulation

Summary – Writing Process Steps

The summary below outlines the major steps writers work through as they endeavor to develop an idea for an audience .

1. Prewriting

Prewriting refers to all the work a writer does on a writing project before they actually begin writing .

Acts of prewriting include

- Prior to writing a first draft, analyze the context for the work. For instance, in school settings students may analyze how much of their grade will be determined by a particular assignment. They may question how many and what sources are required and what the grading criteria will be used for critiquing the work.

- To further their understanding of the assignment, writers will question who the audience is for their work, what their purpose is for writing, what style of writing their audience expects them to employ, and what rhetorical stance is appropriate for them to develop given the rhetorical situation they are addressing. (See the document planner heuristic for more on this)

- consider employing rhetorical appeals ( ethos , pathos , and logos ), rhetorical devices , and rhetorical modes they want to develop once they begin writing

- reflect on the voice , tone , and persona they want to develop

- Following rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning , writers decide on the persona ; point of view ; tone , voice and style of writing they hope to develop, such as an academic writing prose style or a professional writing prose style

- making a plan, an outline, for what to do next.

2. Invention

Invention is traditionally defined as an initial stage of the writing process when writers are more focused on discovery and creative play. During the early stages of a project, writers brainstorm; they explore various topics and perspectives before committing to a specific direction for their discourse .

In practice, invention can be an ongoing concern throughout the writing process. People who are focused on solving problems and developing original ideas, arguments , artifacts, products, services, applications, and texts are open to acts of invention at any time during the writing process.

Writers have many different ways to engage in acts of invention, including

- What is the exigency, the call to write ?

- What are the ongoing scholarly debates in the peer-review literature?

- What is the problem ?

- What do they read? watch? say? What do they know about the topic? Why do they believe what they do? What are their beliefs, values, and expectations ?

- What rhetorical appeals — ethos (credibility) , pathos (emotion) , and logos (logic) — should I explore to develop the best response to this exigency , this call to write?

- What does peer-reviewed research say about the subject?

- What are the current debates about the subject?

- Embrace multiple viewpoints and consider various approaches to encourage the generation of original ideas.

- How can I experiment with different media , genres , writing styles , personas , voices , tone

- Experiment with new research methods

- Write whatever ideas occur to you. Focus on generating ideas as opposed to writing grammatically correct sentences. Get your thoughts down as fully and quickly as you can without critiquing them.

- Use heuristics to inspire discovery and creative thinking: Burke’s Pentad ; Document Planner , Journalistic Questions , The Business Model Canvas

- Embrace the uncertainty that comes with creative exploration.

- Listen to your intuition — your felt sense — when composing

- Experiment with different writing styles , genres , writing tools, and rhetorical stances

- Play the believing game early in the writing process

3. Researching

Research refers to systematic investigations that investigators carry out to discover new knowledge , test knowledge claims , solve problems , or develop new texts , products, apps, and services.

During the research stage of the writing process, writers may engage in

- Engage in customer discovery interviews and survey research in order to better understand the problem space . Use surveys , interviews, focus groups, etc., to understand the stakeholder’s s (e.g., clients, suppliers, partners) problems and needs

- What can you recall from your memory about the subject?

- What can you learn from informal observation?

- What can you learn from strategic searching of the archive on the topic that interests you?

- Who are the thought leaders?

- What were the major turns to the conversation ?

- What are the current debates on the topic ?

- Mixed research methods , qualitative research methods , quantitative research methods , usability and user experience research ?

- What citation style is required by the audience and discourse community you’re addressing? APA | MLA .

4. Collaboration

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others to exchange ideas, solve problems, investigate subjects , coauthor texts , and develop products and services.

Collaboration can play a major role in the writing process, especially when authors coauthor documents with peers and teams , or critique the works of others .

Acts of collaboration include

- Paying close attention to what others are saying, acknowledging their input, and asking clarifying questions to ensure understanding.

- Expressing ideas, thoughts, and opinions in a concise and understandable manner, both verbally and in writing.

- Being receptive to new ideas and perspectives, and considering alternative approaches to problem-solving.

- Adapting to changes in project goals, timelines, or team dynamics, and being willing to modify plans when needed.

- Distributing tasks and responsibilities fairly among team members, and holding oneself accountable for assigned work.

- valuing and appreciating the unique backgrounds, skills, and perspectives of all team members, and leveraging this diversity to enhance collaboration.

- Addressing disagreements or conflicts constructively and diplomatically, working towards mutually beneficial solutions.

- Providing constructive feedback to help others improve their work, and being open to receiving feedback to refine one’s own ideas and contributions.

- Understanding and responding to the emotions, needs, and concerns of team members, and fostering a supportive and inclusive environment .

- Acknowledging and appreciating the achievements of the team and individual members, and using successes as a foundation for continued collaboration and growth.

5. Planning

Planning refers to

- the process of planning how to organize a document

- the process of managing your writing processes

6. Organizing

Following rhetorical analysis , following prewriting , writers question how they should organize their texts. For instance, should they adopt the organizational strategies of academic discourse or workplace-writing discourse ?

Writing-Process Plans

- What is your Purpose? – Aims of Discourse

- What steps, or strategies, need to be completed next?

- set a schedule to complete goals

Planning Exercises

- Document Planner

- Team Charter

7. Designing

Designing refers to efforts on the part of the writer

- to leverage the power of visual language to convey meaning

- to create a visually appealing text

During the designing stage of the writing process, writers explore how they can use the elements of design and visual language to signify , clarify , and simplify the message.

Examples of the designing step of the writing process:

- Establishing a clear hierarchy of visual elements, such as headings, subheadings, and bullet points, to guide the reader’s attention and facilitate understanding.

- Selecting appropriate fonts, sizes, and styles to ensure readability and convey the intended tone and emphasis.

- Organizing text and visual elements on the page or screen in a manner that is visually appealing, easy to navigate, and supports the intended message.

- Using color schemes and contrasts effectively to create a visually engaging experience, while also ensuring readability and accessibility for all readers.

- Incorporating images, illustrations, charts, graphs, and videos to support and enrich the written content, and to convey complex ideas in a more accessible format.

- Designing content that is easily accessible to a wide range of readers, including those with visual impairments, by adhering to accessibility guidelines and best practices.

- Maintaining a consistent style and design throughout the text, which includes the use of visuals, formatting, and typography, to create a cohesive and professional appearance.

- Integrating interactive elements, such as hyperlinks, buttons, and multimedia, to encourage reader engagement and foster deeper understanding of the content.

8. Drafting

Drafting refers to the act of writing a preliminary version of a document — a sloppy first draft. Writers engage in exploratory writing early in the writing process. During drafting, writers focus on freewriting: they write in short bursts of writing without stopping and without concern for grammatical correctness or stylistic matters.

When composing, writers move back and forth between drafting new material, revising drafts, and other steps in the writing process.

9. Rereading

Rereading refers to the process of carefully reviewing a written text. When writers reread texts, they look in between each word, phrase, sentence, paragraph. They look for gaps in content, reasoning, organization, design, diction, style–and more.

When engaged in the physical act of writing — during moments of composing — writers will often pause from drafting to reread what they wrote or to reread some other text they are referencing.

10. Revising

Revision — the process of revisiting, rethinking, and refining written work to improve its content , clarity and overall effectiveness — is such an important part of the writing process that experienced writers often say “writing is revision” or “all writing is revision.”

For many writers, revision processes are deeply intertwined with writing, invention, and reasoning strategies:

- “Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what one is saying.” — John Updike

- “How do I know what I think until I see what I say.” — E.M. Forster

Acts of revision include

- Pivoting: trashing earlier work and moving in a new direction

- Identifying Rhetorical Problems

- Identifying Structural Problems

- Identifying Language Problems

- Identifying Critical & Analytical Thinking Problems

11. Editing

Editing refers to the act of critically reviewing a text with the goal of identifying and rectifying sentence and word-level problems.

When editing , writers tend to focus on local concerns as opposed to global concerns . For instance, they may look for

- problems weaving sources into your argument or analysis

- problems establishing the authority of sources

- problems using the required citation style

- mechanical errors ( capitalization , punctuation , spelling )

- sentence errors , sentence structure errors

- problems with diction , brevity , clarity , flow , inclusivity , register, and simplicity

12. Proofreading

Proofreading refers to last time you’ll look at a document before sharing or publishing the work with its intended audience(s). At this point in the writing process, it’s too late to add in some new evidence you’ve found to support your position. Now you don’t want to add any new content. Instead, your goal during proofreading is to do a final check on word-level errors, problems with diction , punctuation , or syntax.

13. Sharing or Publishing

Sharing refers to the last step in the writing process: the moment when the writer delivers the message — the text — to the target audience .

Writers may think it makes sense to wait to share their work later in the process, after the project is fairly complete. However, that’s not always the case. Sometimes you can save yourself a lot of trouble by bringing in collaborators and critics earlier in the writing process.

Doherty, M. (2016, September 4). 10 things you need to know about banyan trees. Under the Banyan. https://underthebanyan.blog/2016/09/04/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-banyan-trees/

Emig, J. (1967). On teaching composition: Some hypotheses as definitions. Research in The Teaching of English, 1(2), 127-135. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022783.pdf

Emig, J. (1971). The composing processes of twelfth graders (Research Report No. 13). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Emig, J. (1983). The web of meaning: Essays on writing, teaching, learning and thinking. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Ghiselin, B. (Ed.). (1985). The Creative Process: Reflections on the Invention in the Arts and Sciences . University of California Press.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive Processes in Writing: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369-388. https://doi: 10.1177/0741088312451260

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

Leijten, Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3

Lundstrom, K., Babcock, R. D., & McAlister, K. (2023). Collaboration in writing: Examining the role of experience in successful team writing projects. Journal of Writing Research, 15(1), 89-115. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2023.15.01.05

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.https://doi.org/10.17226/13398.

North, S. M. (1987). The making of knowledge in composition: Portrait of an emerging field. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Murray, Donald M. (1980). Writing as process: How writing finds its own meaning. In Timothy R. Donovan & Ben McClelland (Eds.), Eight approaches to teaching composition (pp. 3–20). National Council of Teachers of English.

Murray, Donald M. (1972). “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product.” The Leaflet, 11-14

Perry, S. K. (1996). When time stops: How creative writers experience entry into the flow state (Order No. 9805789). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304288035). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/when-time-stops-how-creative-writers-experience/docview/304288035/se-2

Rohman, D.G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1964). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Rohman, D. G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1975). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers. College Composition and Communication, 31(4), 378-388. doi: 10.2307/356600

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Recommended

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...