Open Resources for English Language Teaching (ORELT) Portal

Search form

You are here, unit 5: promoting creative writing, introduction.

Creative writing is writing about events in an imaginative way. Novels, plays, short stories and poems are some examples of creative writing. We often think creative writing can only be done by “experts” — that is, poets, playwrights and novelists. Interestingly, however, creative writing can actually be cultivated through classroom writing activities. Students learn to write creatively by reading and analysing the works of experienced writers and by writing stories, poems or plays of their own. This helps them to acquire both the language (vocabulary and structures) and narrative skills (making an interesting beginning, using dialogue skilfully, weaving in contemporary, everyday events to sound more natural, etc.) that they need.

This unit is about how you can promote creative writing amongst your students. It aims to help you and your students explore how a narrative can be developed into an interesting story, or how the words we use every day can be arranged into a rhyming poem. The unit should help you encourage your students to explore and write descriptions that appeal to the senses, arguments that are convincing and narratives that relate ordinary events in an extraordinary way. Your task is to help your students notice what makes the texts creative rather than a collection of ordinary factual information.

Unit outcomes

Upon completion of this unit you will be able to:

|

|

Terminology

|

| A short story is a short work of fiction that is usually written in prose, often in narrative format. This format or medium tends to tell a story in lesser detail than longer works of fiction, such as novels or books. | |

| A novel is a long narrative in literary prose. | ||

| Drama is a type of fictional text that tells a story through dialogue between characters. Unlike novels, drama uses set directions in place of descriptions, and is divided into scenes and acts rather than chapters. | ||

| A comparison between two things (objects or events) made in an overt and obvious manner, using words such as or : , etc. | ||

| The word is from the Greek meaning . A metaphor makes a comparison between two things (objects or events) by transferring the qualities of one to the other in a non-obvious manner. For example: he is /her /the In the first example, the quality of of a lion is transferred to the person, the second one transfers the of a mouse to the girl’s character, and in the third example, is used for its negative characteristics such as and . |

Teacher support information

Creative writing is considered to be any writing — fiction, poetry, non-fiction, drama. etc. — that falls outside the bounds of normal professional, journalistic, academic and technical forms of writing. Works in this category include novels, epics, short stories and poems (see Resource 1: Why and how to teach creative writing , and Resource 2 : Kinds of creative writing ). A creative writer often gives his or her readers pictures to see, sounds to hear, or things to taste, feel and smell. Note that creative writers look for words that help us to see and hear what they have seen, heard or imagined.

A writer can tell us about the things he or she has seen or imagined by using descriptive words such as shining, narrow, huge, small, glowing, etc. He or she may also use phrases or expressions like the road was a ribbon of moonlight, the wind was a torrent of darkness, his heart was jumping, etc. Expressions like these are called figures of speech .

A number of teaching techniques, including story retelling and shared writing, can help you develop your students’ creative writing skills. (See Resources 3a and b on shared writing).

|

| In an effort to develop her students’ creative writing skills, Mrs Rweza, a secondary school teacher, decided to use the story re-telling technique. She prepared herself by reading several stories and picking one that she thought was suitable to read to her class. During the creative writing lesson, she invited her class to listen carefully to the story. After the story was read, Mrs Rweza guided her students in discussing the important parts of the story. She used questions such as Working in groups, the students also discussed and reached a consensus on what they would include or exclude if they were to reconstruct the story, and why. At the end of the first lesson, Mrs Rweza asked the students to write their own version of the story as their home assignment. In the next lesson the students discussed their stories with their partners. Then Mrs Rweza asked some students to present their stories to the class. She was amazed by the descriptions, arguments and explanations that the students wrote. She realised that this was an effective strategy for developing creativity and imaginative thinking in students. |

|

|

Activity 1: Promoting creative writing through shared writing

|

| , and . |

Activity 2: Developing imagination

|

|

A short, thin man was standing in front of a big box. His big eyes were popping out and his mouth was full of saliva. He was thinking, “This is my catch! I will no longer be hungry, skinny and weak.” Suddenly a large woman appeared from nowhere. She lifted the heavy box as if it were empty, and ran away with it as fast as the wind. Before the little man could say anything, two policemen came running up behind him and asked, “Have you seen a big box anywhere?” He looked at the policemen and then turned around again, but the woman and the box had disappeared. You can also use this technique to teach students to write different kinds of passages. |

Activity 3: Writing a rhyming poem

|

| Provide a selection of poems for your students and have a class discussion on what is special about them. Your objective is to have your students identify points such as unusual combinations of words, use of rhyming words, special comparisons like similes and metaphors, and so on, with examples from the poems. The students now need to practise using their imagination to compose something creatively. You can begin with simple activities such as making a list of rhyming words, then combining or using them in creative and unusual ways and making short verses with them. As a first step, ask your students to write five words that end with the same sounds; for example, / / . Let the students use the words in interesting and usual expressions that describe something (object or action) creatively; for example, similes such as or metaphors such as . Guide the students in writing five short sentences that end with the rhyming words. Guide the students in discussing in groups what appears to be special about their sentences. As a homework assignment, ask your students to write two verses of a poem of their own. |

Unit summary

|

| This unit has familiarised you with the techniques of developing creative writing skills in your students. These techniques included retelling a story orally and in writing, as well as the process of shared writing. Your students will also have learned how to practise writing short stories and simple poems. |

Reflections

|

|

Resource 1: Why and how to teach creative writing

|

|

Creative writing is any composition — fiction, poetry, or non-fiction — that expresses ideas in an imaginative and unusual manner. Creative texts are texts that are non-technical, non-academic and non-journalistic, and are read for pleasure rather than for information. In this sense, creative writing is a process-oriented term for what has been traditionally called literature, and includes novels, epics, short stories and poems. Creative texts may be descriptive, narrative or expository, based on personal experiences or popular topics. Any kind of writing that involves an imaginative portrayal of ideas can be called creative writing.

Creative writing sharpens students’ ability to express their thoughts clearly. It encourages them to think beyond the ordinary, and to use their imagination to express their ideas in their own way. Learning about creative writing also makes students familiar with literary terms and mechanisms such as sound patterns or metaphors. This, in turn, can help students to improve their command over the resources of language — for example, vocabulary, sentence patterns and metaphorical expressions — when composing their own creative work. It has also been argued that creative writing helps develop critical thinking skills, as students learn to question and to “think outside the box.” The ability to evaluate a piece of literary work improves students’ problem-solving abilities too.

The teaching of creative writing basically focuses on students’ self-expression. It is taught by taking students through a series of steps that demonstrate the of writing. As a first step, students are introduced to a range of fictional and non-fictional texts, with their attention being drawn to the distinctive structural and linguistic features of each text. They are also sensitised to the and for which specific texts are written. The students are then given practice in the use of linkers, connectives and other semantic markers that are used to connect and present ideas logically in a text. Typical semantic markers in narrative texts are words such as and so on; they perform various functions in the text, such as showing time relationships, cause and effect relationships, conditions, sequence of events and so on. The students are then gradually taught to dramatise events by: Lastly, students are helped to express more complex and layered meanings in stories that: |

Resource 2: Kinds of creative writing

|

| Creative writing usually includes , , and texts. In a text, a writer gives his or her readers pictures to see, sounds to hear, and things to taste, feel and smell. writing defines, explains or describes how something is done or how something happens. A describes an event chronologically, usually with a beginning, middle and end. An is intended to convince others of something or to persuade them to do something. The following are examples of different types of creative texts.

Soil is a dynamic medium in which many chemical, physical and biological activities constantly occur. Soil is a result of decay, but it is also a medium for growth. The characteristics of soil change in different seasons. It may alternately be cold or warm, and dry or moist. When the soil becomes too cold or too dry, biological activity becomes slow, or stops altogether. Biological activity speeds up when leaves fall or grasses die. Soil chemistry thus changes according to season, and the soil adjusts to different climatic conditions, temperature fluctuations and the amount of moisture in the atmosphere.

When I was a child I always wanted a dog, but my mother refused, saying she didn’t have time to look after it and we didn’t have space for a dog to run around. When I was 14 we moved to a bigger house with a big garden, but Mother still refused to let me have a dog. One day a friend of ours brought us a puppy that he’d found abandoned by the side of the road. He was adorable! He had big brown eyes, velvety ears and a happy smile. I pleaded with Mother to keep him. Eventually she gave in to my promises of looking after the dog, working hard at school and taking on extra chores. I called the dog Murphy. He was very loving but also very energetic and I found that I had to spend two hours a day running with him and playing with him. One day he escaped out of the garden and killed our neighbours’ chicken. I felt ill with anxiety in case Mother made me give him away — or worse, have him put down. Luckily our neighbours loved dogs and told us not to worry about it. They asked only that Murphy not be allowed to escape from the house again. We promised that we’d do our absolute best to make sure he didn’t sneak out and cause more trouble. One day, when I was 19, I came home to find Mother sobbing. Murphy had spotted a cat in the street and had squeezed out of an open window to chase after it. In his excitement he didn’t see a car coming. The driver didn’t have time to stop and he hit Murphy. Our only consolation was that Murphy died instantly and didn’t suffer. I was surprised by how upset Mother was by Murphy’s death. She always said she hadn’t wanted a dog but when he died she was the one who seemed to miss him most. (Written by Lesley Cameron, Maple Ridge, Canada)

The settlement of Liberia was founded in 1822 by freed blacks from the United States of America. It was organized by the American Colonization Society—a body of white Americans who believed the increasing number of freed blacks in the southern states was a danger to the maintenance of other blacks in slavery. Representatives of the Colonization Society forced local African chiefs in the Cape Mesurado area to sell them land by threatening them at gunpoint. In the decade that followed, further settlements of freed blacks from America were made along the coastline from Cape Palmas to Sherbo island. Though originally organized by American whites, educated blacks soon took over administration of the settlement. In 1847 they declared their colony the independent republic of “Liberia.” (The name was derived from the Latin word liber, meaning “free,” from which are also derived a number of English words such as “liberty” and “liberal.”) It had a constitution modelled on that of the United States and its capital, Monrovia was named after the American president, Monroe. (Excerpted from by Kevin Shillington (p. 241), from the website )

Imagine a good of yours. Better yet, imagine a loved one, perhaps a brother or sister or son or daughter. Now try to imagine life without them, simply because someone took away their life, and the murderer thought that they were above the law. What if someone took the life of your child or loved one? What are we to do about the person(s), such as these murderers who decide that they can take a loved one's life? Obviously, anyone who takes one's life, other than in self defense, should not ever be let out into everyday society to function in everyday life. Those that prey on the weak will always prey on them. A majority of those convicted and sentenced to capital punishment have been found to be "repeat offenders that continually prey on the weak and innocent”.

* Thirty-seven out of fifty (37 of 50) states in America currently hold laws authorizing the death penalty. * Currently there are more than 2000 people on death row. * Because of various legal interferences, a majority of executions will be stalled. One argument cited against capital punishment is the , which is the likeliness of someone not to commit a crime as a result of being aware of the consequences of the crime. But many argue that the death penalty does not deter. Punishment is socially valuable because it deters criminals from repeating their crimes and may keep others from repeating the same acts. If the deterring effect misses its point, it is the fault of the justice system. At its current standing, the system is viewed as a joke because no one takes it seriously. Both the lengthy time and the high expense that result from innumerable appeals, including many technicalities which have little nothing to do with the question of guilt or innocence, have made everyone make fun of the justice system. If the wasteful amount of appeals were eliminated or at least controlled, the procedure would be much shorter, less expensive and more efficient. Many argue that the death penalty violates human rights. Yet they do not question the reason or action that got the convict on death row in the first place. Every person has an equal right to life, "until they take another's life, then all bets are off”. Society does not understand that when a convict on death row is executed it is because they themselves took some innocent person's life. The only impression given about the death penalty should be the fact that murder is a crime punishable by death. The main purpose here is to instil fear in other people, to show that this will not be tolerated and that justice comes first, always. (Adapted from "Free Capital Punishment Essays — Is the Death Penalty Effective?" ) |

Resource 3a: Using shared writing

|

| The point of using a shared writing strategy is to make the writing process a shared experience, making it visible and concrete while inviting students into the writer’s world in a safe, supportive environment. At the same time, it gives teachers the opportunity of direct teaching of key skills, concepts and processes. All aspects of the writing process are modelled, although not always all at once. At the lower grade levels especially, teachers can concentrate on one or two key aspects of writing in short, focused lessons. Using student input, the teacher guides the group in brainstorming ideas and selecting a topic. As a group, they talk about topics, audience, purpose, details they will include and other considerations. As the group composes the text, the teacher asks probing questions to bring out more detail and to help students make their writing more interesting and meaningful. The tone of this discussion should be collaborative rather than directive. The teacher might say something like, rather than While some pieces will be short and completed in one lesson, others will be longer and may continue through several days’ lessons. This allows students to see that writing can be an extended, ongoing process, and it also allows the teacher to train the students to look at their work critically through strategies such as the periodic re-reading of one’s work before resuming writing and completing the composition. Some teachers include a few well-chosen, purposeful errors during drafting to facilitate the later editing stage. Writing with the class or group, the teacher also has an opportunity to highlight and model the revision process, helping students add to or take away from their text. The group may also decide to change words, text order or other aspects of the writing to achieve their intended meaning. The teacher will often ask questions to help the students focus on communicating their message clearly and concisely. If needed, the teacher can help guide the group in adding detail, taking away unnecessary and confusing words or passages, or changing the structure of the text to clarify meaning. The teacher can also use the shared writing strategy for editing text and focusing on mechanics and conventions such as spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. The structure of the text — that is, paragraph division etc. — is also a focus in this stage, as it is in the drafting and revising stages. From |

Resource 3b: Using the shared writing technique in class

|

| Start by drawing on previous knowledge of stories and wondering/ brainstorming what kind of stories and characters the students like. (In shared writing, to wonder constantly is a strategy for fulfilling the most important function of the activity: to encourage and shape the students’ ideas about how they might express themselves best, and then how it will be written down, as in a book or on paper.) When a consensus is reached about the type of story — for example, the class likes stories about animals — the class must then choose a character — for example, a cow. Then the students should think of what exciting event will happen to this cow. They should agree on the event; for example, They should choose this event from all the ideas put forward by the students. This is another important lesson for students when writing creatively — many ideas are generated but only some can be selected and followed up. Split the students into five mixed-ability groups. The groups take turns to help compose a part of the story and to illustrate their pages. This allows the students to focus their attention on the various elements of the structure of the story as they work through it. All this shaping and teaching is done through the teacher “wondering.” The development of the setting, opening and resolution occur as the writing occurs. Working with small groups gives the teacher the opportunity to emphasise story coherence — the way each part follows from, develops or resolves what has gone before. Re-reading the story is important to assess whether it makes sense and to ensure that each contribution fits in. |

Resource 4: Sample process of shared writing

|

|

The cow lived in a village near the Serengeti National Park.

The cow jumped over the fence.

It ran away to the forest that surrounded the village.

Wonder how we could make the ideas sound like a book. Did the cow try to get back to the village? Did anyone see the cow and try to bring it back? Or did the cow get lost?

The cow met a lion.

The lion roared.

The cow cried “moo” and tried to run away.

The cow ran deeper into the forest and jumped into a river.

It saw a crocodile.

The cow jumped out of the water.

The cow wanted to go home.

It saw a bus and wanted to get into the bus.

The bus driver told it off because cows were not allowed on buses.

The cow ran home. |

Teacher question and answer

|

| When I ask students to use their imaginations and creative abilities to compose something, I find they simply copy passages from prose or poetry texts they have. How can I motivate them to think on their own? One of the reasons students feel anxious about producing their own texts is because we them rather than them composition. For example, we say without showing them this is to be done. The activities described above try to address this problem by taking students through the process of creative writing, beginning from the formulation of ideas to making a draft. If you follow this strategy in the class and take students through a step-by-step demonstration, their inhibitions will gradually disappear. |

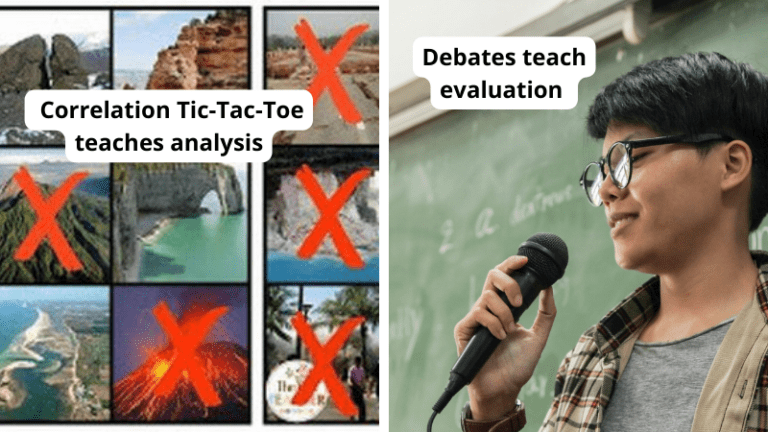

48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content Area

Critical thinking questions include, ‘Why is this important? What are the causes and effects of this? How do we know if this is true?”

What Are Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content Area?

by TeachThought Staff

Critical thinking is the heart and soul of learning, and–in our estimation anyway–ultimately more important than any one specific content area or subject matter.

It’s also an over-used and rather nebulous phrase — how do you teach someone to think? Of course, that’s the purpose of education, but how do you effectively optimize that concept into lasting knowledge and the ability to apply it broadly?

Looking for more resources to teach critical thinking? Check out our critical thinking curricula resources on TpT.

What Is Critical Thinking?

This question is what inspires the creation of seemingly endless learning taxonomies and teaching methods: our desire to pin down a clear definition of what it means to think critically and how to introduce that skill in the classroom.

This makes critical thinking questions–well, critical. As Terry Heick explains in What Does Critical Thinking Mean?:

“To think critically about something is to claim to first circle its meaning entirely—to walk all the way around it so that you understand it in a way that’s uniquely you. The thinker works with their own thinking tools–schema. Background knowledge. Sense of identity. Meaning Making is a process as unique to that thinker as their own thumbprint. There is no template.

After circling the meaning of whatever you’re thinking critically about—navigation necessarily done with bravado and purpose—the thinker can then analyze the thing. In thinking critically, the thinker has to see its parts, its form, its function, and its context.

After this kind of survey and analysis you can come to evaluate it–bring to bear your own distinctive cognition on the thing so that you can point out flaws, underscore bias, emphasize merit—to get inside the mind of the author, designer, creator, or clockmaker and critique his work.”

A Cheat Sheet For Critical Thinking

In short, critical thinking is more than understanding something — it involves evaluation, critiquing, and a depth of knowledge that surpasses the subject itself and expands outward. It requires problem-solving, creativity, rationalization, and a refusal to accept things at face value.

It’s a willingness and ability to question everything.

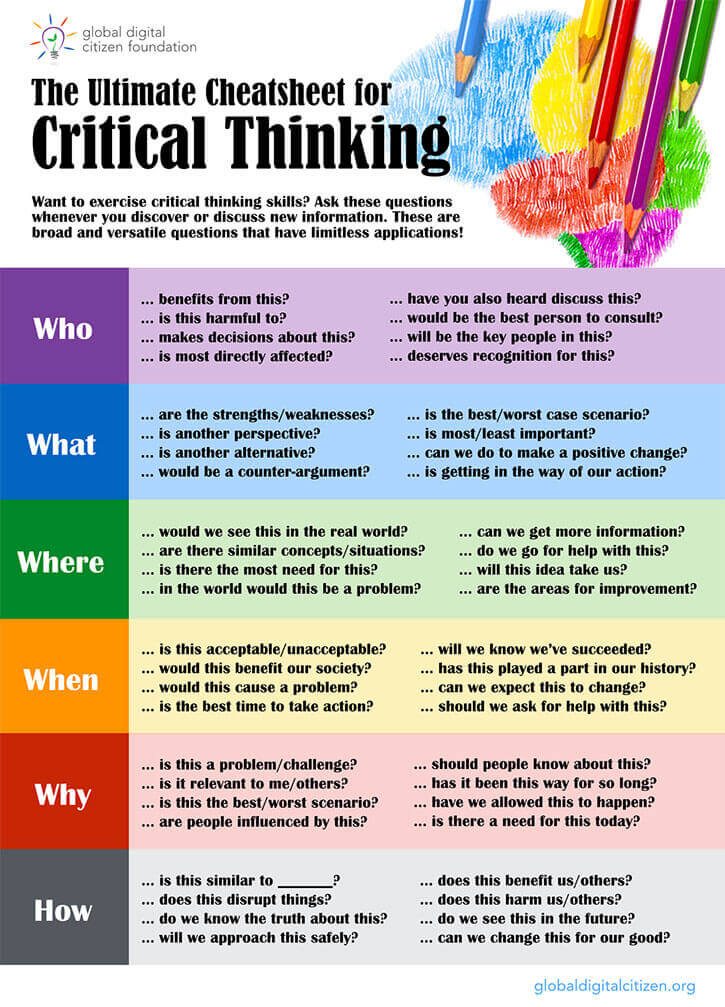

The Ultimate Cheat Sheet For Digital Thinking by Global Digital Citizen Foundation is an excellent starting point for the ‘how’ behind teaching critical thinking by outlining which questions to ask.

It offers 48 critical thinking questions useful for any content area or even grade level with a little re-working/re-wording. Enjoy the list!

48 Critical Thinking Questions For Any Content Area

See Also: 28 Critical Thinking Question Stems & Response Cards

TeachThought is an organization dedicated to innovation in education through the growth of outstanding teachers.

Reading & Writing Purposes

Introduction: critical thinking, reading, & writing, critical thinking.

The phrase “critical thinking” is often misunderstood. “Critical” in this case does not mean finding fault with an action or idea. Instead, it refers to the ability to understand an action or idea through reasoning. According to the website SkillsYouNeed [1]:

Critical thinking might be described as the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking.

In essence, critical thinking requires you to use your ability to reason. It is about being an active learner rather than a passive recipient of information.

Critical thinkers rigorously question ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value. They will always seek to determine whether the ideas, arguments, and findings represent the entire picture and are open to finding that they do not.

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct.

Someone with critical thinking skills can:

- Understand the links between ideas.

- Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas.

- Recognize, build, and appraise arguments.

- Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

- Approach problems in a consistent and systematic way.

- Reflect on the justification of their own assumptions, beliefs and values.

Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/critical-thinking.html

Critical thinking—the ability to develop your own insights and meaning—is a basic college learning goal. Critical reading and writing strategies foster critical thinking, and critical thinking underlies critical reading and writing.

Critical Reading

Critical reading builds on the basic reading skills expected for college.

College Readers’ Characteristics

- College readers are willing to spend time reflecting on the ideas presented in their reading assignments. They know the time is well-spent to enhance their understanding.

- College readers are able to raise questions while reading. They evaluate and solve problems rather than merely compile a set of facts to be memorized.

- College readers can think logically. They are fact-oriented and can review the facts dispassionately. They base their judgments on ideas and evidence.

- College readers can recognize error in thought and persuasion as well as recognize good arguments.

- College readers are skeptical. They understand that not everything in print is correct. They are diligent in seeking out the truth.

Critical Readers’ Characteristics

- Critical readers are open-minded. They seek alternative views and are open to new ideas that may not necessarily agree with their previous thoughts on a topic. They are willing to reassess their views when new or discordant evidence is introduced and evaluated.

- Critical readers are in touch with their own personal thoughts and ideas about a topic. Excited about learning, they are eager to express their thoughts and opinions.

- Critical readers are able to identify arguments and issues. They are able to ask penetrating and thought-provoking questions to evaluate ideas.

- Critical readers are creative. They see connections between topics and use knowledge from other disciplines to enhance their reading and learning experiences.

- Critical readers develop their own ideas on issues, based on careful analysis and response to others’ ideas.

The video below, although geared toward students studying for the SAT exam (Scholastic Aptitude Test used for many colleges’ admissions), offers a good, quick overview of the concept and practice of critical reading.

Critical Reading & Writing

College reading and writing assignments often ask you to react to, apply, analyze, and synthesize information. In other words, your own informed and reasoned ideas about a subject take on more importance than someone else’s ideas, since the purpose of college reading and writing is to think critically about information.

Critical thinking involves questioning. You ask and answer questions to pursue the “careful and exact evaluation and judgment” that the word “critical” invokes (definition from The American Heritage Dictionary ). The questions simply change depending on your critical purpose. Different critical purposes are detailed in the next pages of this text.

However, here’s a brief preview of the different types of questions you’ll ask and answer in relation to different critical reading and writing purposes.

When you react to a text you ask:

- “What do I think?” and

- “Why do I think this way?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “reaction” questions about the topic assimilation of immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: I think that assimilation has both positive and negative effects because, while it makes life easier within the dominant culture, it also implies that the original culture is of lesser value.

When you apply text information you ask:

- “How does this information relate to the real world?”

e.g., If I asked and answered this “application” question about the topic assimilation , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: During the past ten years, a group of recent emigrants has assimilated into the local culture; the process of their assimilation followed certain specific stages.

When you analyze text information you ask:

- “What is the main idea?”

- “What do I want to ‘test’ in the text to see if the main idea is justified?” (supporting ideas, type of information, language), and

- “What pieces of the text relate to my ‘test?'”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “analysis” questions about the topic immigrants to the United States , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: Although Lee (2009) states that “segmented assimilation theory asserts that immigrant groups may assimilate into one of many social sectors available in American society, instead of restricting all immigrant groups to adapting into one uniform host society,” other theorists have shown this not to be the case with recent immigrants in certain geographic areas.

When you synthesize information from many texts you ask:

- “What information is similar and different in these texts?,” and

- “What pieces of information fit together to create or support a main idea?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “synthesis” questions about the topic immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop by using examples and information from many text articles as evidence to support my idea: Immigrants who came to the United States during the immigration waves in the early to mid 20th century traditionally learned English as the first step toward assimilation, a process that was supported by educators. Now, both immigrant groups and educators are more focused on cultural pluralism than assimilation, as can be seen in educators’ support of bilingual education. However, although bilingual education heightens the child’s reasoning and ability to learn, it may ultimately hinder the child’s sense of security within the dominant culture if that culture does not value cultural pluralism as a whole.

Critical reading involves asking and answering these types of questions in order to find out how the information “works” as opposed to just accepting and presenting the information that you read in a text. Critical writing involves recording your insights into these questions and offering your own interpretation of a concept or issue, based on the meaning you create from those insights.

- Crtical Thinking, Reading, & Writing. Authored by : Susan Oaks, includes material adapted from TheSkillsYouNeed and Reading 100; attributions below. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : TheSkillsYouNeed. Located at : https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Quoted from website: The use of material found at skillsyouneed.com is free provided that copyright is acknowledged and a reference or link is included to the page/s where the information was found. Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/

- The Reading Process. Authored by : Scottsdale Community College Reading Faculty. Provided by : Maricopa Community College. Located at : https://learn.maricopa.edu/courses/904536/files/32966438?module_item_id=7198326 . Project : Reading 100. License : CC BY: Attribution

- image of person thinking with light bulbs saying -idea- around her head. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/light-bulb-idea-think-education-3704027/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video What is Critical Reading? SAT Critical Reading Bootcamp #4. Provided by : Reason Prep. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hc3hmwnymw . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- image of man smiling and holding a lightbulb. Authored by : africaniscool. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/man-african-laughing-idea-319282/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

- How to apply critical thinking in learning

Sometimes your university classes might feel like a maze of information. Consider critical thinking skills like a map that can lead the way.

Why do we need critical thinking?

Critical thinking is a type of thinking that requires continuous questioning, exploring answers, and making judgments. Critical thinking can help you:

- analyze information to comprehend more thoroughly

- approach problems systematically, identify root causes, and explore potential solutions

- make informed decisions by weighing various perspectives

- promote intellectual curiosity and self-reflection, leading to continuous learning, innovation, and personal development

What is the process of critical thinking?

1. understand .

Critical thinking starts with understanding the content that you are learning.

This step involves clarifying the logic and interrelations of the content by actively engaging with the materials (e.g., text, articles, and research papers). You can take notes, highlight key points, and make connections with prior knowledge to help you engage.

Ask yourself these questions to help you build your understanding:

- What is the structure?

- What is the main idea of the content?

- What is the evidence that supports any arguments?

- What is the conclusion?

2. Analyze

You need to assess the credibility, validity, and relevance of the information presented in the content. Consider the authors’ biases and potential limitations in the evidence.

Ask yourself questions in terms of why and how:

- What is the supporting evidence?

- Why do they use it as evidence?

- How does the data present support the conclusions?

- What method was used? Was it appropriate?

3. Evaluate

After analyzing the data and evidence you collected, make your evaluation of the evidence, results, and conclusions made in the content.

Consider the weaknesses and strengths of the ideas presented in the content to make informed decisions or suggest alternative solutions:

- What is the gap between the evidence and the conclusion?

- What is my position on the subject?

- What other approaches can I use?

When do you apply critical thinking and how can you improve these skills?

1. reading academic texts, articles, and research papers.

- analyze arguments

- assess the credibility and validity of evidence

- consider potential biases presented

- question the assumptions, methodologies, and the way they generate conclusions

2. Writing essays and theses

- demonstrate your understanding of the information, logic of evidence, and position on the topic

- include evidence or examples to support your ideas

- make your standing points clear by presenting information and providing reasons to support your arguments

- address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints

- explain why your perspective is more compelling than the opposing viewpoints

3. Attending lectures

- understand the content by previewing, active listening , and taking notes

- analyze your lecturer’s viewpoints by seeking whether sufficient data and resources are provided

- think about whether the ideas presented by the lecturer align with your values and beliefs

- talk about other perspectives with peers in discussions

Related blog posts

- Survival guide to group work

- Four common group project challenges (and what to do)

- Determine the best way to graph your data

- How to read graphs and diagrams

- A beginner's guide to successful labs

Recent blog posts

Blog topics.

- assignments (1)

- Graduate (2)

- Learning support (27)

- note-taking and reading (8)

- research (2)

- tests and exams (8)

- time management (3)

- Tips from students (9)

- undergraduate (29)

- university learning (12)

Blog posts by audience

- Current undergraduate students (31)

- Current graduate students (5)

- Future undergraduate students (9)

- Future graduate students (1)

Blog posts archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (8)

- August (10)

Contact the Student Success Office

South Campus Hall, second floor University of Waterloo 519-888-4567 ext. 84410

Immigration Consulting

Book a same-day appointment on Portal or submit an online inquiry to receive immigration support.

Request an authorized leave from studies for immigration purposes.

Quick links

Current student resources

Employment and volunteer opportunities

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg, and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations .

Creative Writing for Critical Thinking

Creating a Discoursal Identity

- © 2018

- Hélène Edberg 0

Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Introduces a new analytical model, based on activity theory, making it possible to analyse learning through writing in student texts

- Examines student trajectories as they learn to think critically through creative writing

- Offers practical advice as well as theoretical grounding to support this new approach

13k Accesses

6 Citations

2 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

Autofictionalizing Reflective Writing Pedagogies: Risks and Possibilities

Virginia Woolf, the Historical Sense, and Creative Criticism

Writing with, Learning from, and Paying Forward Mentorship from Early-Career Scholars: My Scholarly Formation into Academic Writing

- discourse analysis

- textual analysis

- meta-reflection

- creative writing

- identity negotiation

- critical thinking

- literary diction

Table of contents (10 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

Hélène Edberg

Creative Writing and Critical Thinking: From a Romantic to a Sociocritical View on Creative Writing

Basic outlines of the research, discoursal identity and subject, text as a site of negotiation: a model for text analysis, writers’ positions, critical metareflection, a follow-up study: creative writing for critical metareflection in a different context, concluding discussion about discoursal identity and learning critical thinking through creative writing, creative writing for critical metareflection: some educational implications, back matter, authors and affiliations, about the author, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Creative Writing for Critical Thinking

Book Subtitle : Creating a Discoursal Identity

Authors : Hélène Edberg

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65491-1

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Social Sciences , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-319-65490-4 Published: 20 February 2018

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-319-88041-9 Published: 11 May 2019

eBook ISBN : 978-3-319-65491-1 Published: 08 February 2018

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : IX, 416

Number of Illustrations : 2 b/w illustrations, 2 illustrations in colour

Topics : Discourse Analysis , Language and Literature , Stylistics , Creative Writing , Popular Science in Linguistics

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

1.3 Glance at Critical Response: Rhetoric and Critical Thinking

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use words, images, and specific rhetorical terminology to understand, discuss, and analyze a variety of texts.

- Determine how genre conventions are shaped by audience, purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Distinguish among different types of rhetorical situations and communicate effectively within them.

Every day you find yourself in rhetorical situations and use rhetoric to communicate with and to persuade others, even though you might not realize you are doing it. For example, when you voice your opinion or respond to another’s opinion, you are thinking rhetorically. Your purpose is often to convince others that you have a valid opinion, and maybe even issue a call to action. Obviously, you use words to communicate and present your position. But you may communicate effectively through images as well.

Words and Images

Both words and images convey information, but each does so in significantly different ways. In English, words are written sequentially, from left to right. A look at a daily newspaper or web page reveals textual information further augmented by headlines, titles, subtitles, boldface, italics, white space, and images. By the time readers get to college, they have internalized predictive strategies to help them critically understand a variety of written texts and the images that accompany them. For example, you might be able to predict the words in a sentence as you are reading it. You also know the purpose of headers and other markers that guide you through the reading.

To be a critical reader, though, you need to be more than a good predictor. In addition to following the thread of communication, you need to evaluate its logic. To do that, you need to ask questions such as these as you consider the argument: Is it fair (i.e., unbiased)? Does it provide credible evidence? Does it make sense, or is it reasonably plausible? Then, based on what you have decided, you can accept or reject its conclusions. You may also consider alternative possibilities so that you can learn more. In this way, you read actively, searching for information and ideas that you understand and can use to further your own thinking, writing, and speaking. To move from understanding to critical awareness, plan to read a text more than once and in more than one way. One good strategy is to ask questions of a text rather than to accept the author’s ideas as fact. Another strategy is to take notes about your understanding of the passage. And another is to make connections between concepts in different parts of a reading. Maybe an idea on page 4 is reiterated on page 18. To be an active, engaged reader, you will need to build bridges that illustrate how concepts become part of a larger argument. Part of being a good reader is the act of building information bridges within a text and across all the related information you encounter, including your experiences.

With this goal in mind, beware of passive reading. If you ever have been reading and completed a page or paragraph and realized you have little idea of what you’ve just read, you have been reading passively or just moving your eyes across the page. Although you might be able to claim you “read” the material, you have not engaged with the text to learn from it, which is the point of reading. You haven’t built bridges that connect to other material. Remember, words help you make sense of the world, communicate in the world, and create a record to reflect on so that you can build bridges across the information you encounter.

Images, however, present a different set of problems for critical readers. Sometimes having little or no accompanying text, images require a different skill set. For example, in looking at a photograph or drawing, you find different information presented simultaneously. This presentation allows you to scan or stop anywhere in the image—at least theoretically. Because visual information is presented simultaneously, its general meaning may be apparent at a glance, while more nuanced or complicated meanings may take a long time to figure out. And even then, odds are these meanings will vary from one viewer to another.

In the well-known image shown in Figure 1.3 , do you see an old woman or a young woman? Although the image remains static, your interpretation of it may change depending on any number of factors, including your experience, culture, and education. Once you become aware of the two perspectives of this image, you can see the “other” easily. But if you are not told about the two ways to “see” it, you might defend a perspective without realizing that you are missing another one. Most visuals, however, are not optical illusions; less noticeable perspectives may require more analysis and may be more influenced by your cultural identity and the ways in which you are accustomed to interpreting. In any case, this image is a reminder to have an open mind and be willing to challenge your perspectives against your interpretations. As such, like written communication, images require analysis before they can be understood thoroughly and evaluation before they can be judged on a wider scale.

If you have experience with social media, you may be familiar with the way users respond to images or words by introducing another image: the meme . A meme is a photograph containing text that presents one viewer’s response. The term meme originates from the Greek root mim , meaning “mime” or “mimic,” and the English suffix -eme . In the 1970s, British evolutionary biologist and author Richard Dawkins (b. 1941) created the term for use as “a unit of cultural transmission,” and he understood it to be “the cultural equivalent of a gene.” Today, according to the dictionary definition, memes are “amusing or interesting items that spread widely through the Internet.” For example, maybe you have seen a meme of an upset cat or of a friend turning around to look at something else while another friend is relating something important. The text that accompanies these pictures provides some expression on the part of the originator that the audience usually finds humorous, relatable, or capable of arousing any range of emotion or thought. For example, in the photograph shown in Figure 1.4 of a critter standing at attention, the author of the text conveys anxiousness. The use of the word like has been popularized in the meme genre to mean “to give an example.”

While these playful aspects of images are important, you also should recognize how images fit into the rhetorical situation. Consider the same elements, such as context and genre, when viewing images. You may find multiple perspectives to consider. In addition, where images show up in a text or for an audience might be important. These are all aspects of understanding the situation and thinking critically. Engaged readers try to connect and build bridges to information across text and images.

As you consider your reading and viewing experiences on social media and elsewhere, note that your responses involve some basic critical thinking strategies. Some of these include summary, paraphrase, analysis, and evaluation, which are defined in the next section. The remaining parts of this chapter will focus on written communication. While this chapter touches only briefly on visual discourse, Image Analysis: What You See presents an extensive discussion on visual communication.

Relation to Academics

As with all disciplines, rhetoric has its own vocabulary. What follows are key terms, definitions, and elements of rhetoric. Become familiar with them as you discuss and write responses to the various texts and images you will encounter.

- Analysis : detailed breakdown or other explanation of some aspect or aspects of a text. Analysis helps readers understand the meaning of a text.

- Authority : credibility; background that reflects experience, knowledge, or understanding of a situation. An authoritative voice is clear, direct, factual, and specific, leaving an impression of confidence.

- Context : setting—time and place—of the rhetorical situation. The context affects the ways in which a particular social, political, or economic situation influences the process of communication. Depending on context, you may need to adapt your text to audience background and knowledge by supplying (or omitting) information, clarifying terminology, or using language that best reaches your readers.

- Culture : group of people who share common beliefs and lived experiences. Each person belongs to various cultures, such as a workplace, school, sports team fan, or community.

- Evaluation : systematic assessment and judgment based on specific and articulated criteria, with a goal to improve understanding.

- Evidence : support or proof for a fact, opinion, or statement. Evidence can be presented as statistics, examples, expert opinions, analogies, case studies, text quotations, research in the field, videos, interviews, and other sources of credible information.

- Media literacy : ability to create, understand, and evaluate various types of media; more specifically, the ability to apply critical thinking skills to them.

- Meme : image (usually) with accompanying text that calls for a response or elicits a reaction.

- Paraphrase : rewording of original text to make it clearer for readers. When they are part of your text, paraphrases require a citation of the original source.

- Rhetoric : use of effective communication in written, visual, or other forms and understanding of its impact on audiences as well as of its organization and structure.

- Rhetorical situation : instance of communication; the conditions of a communication and the agents of that communication.

- Social media : all digital tools that allow individuals or groups to create, post, share, or otherwise express themselves in a public forum. Social media platforms publish instantly and can reach a wide audience.

- Summary : condensed account of a text or other form of communication, noting its main points. Summaries are written in one’s own words and require appropriate attribution when used as part of a paper.

- Tone : an author’s projected or perceived attitude toward the subject matter and audience. Word choice, vocal inflection, pacing, and other stylistic choices may make the author sound angry, sarcastic, apologetic, resigned, uncertain, authoritative, and so on.

As you read through these terms, you likely recognize most of them and realize you are adept in some rhetorical situations. For example, when you talk with friends about your trip to the local mall, you provide details they will understand. You might refer to previous trips or tell them what is on sale or that you expect to see someone from school there. In other words, you understand the components of the rhetorical situation. However, if you tell your grandparents about the same trip, the rhetorical situation will be different, and you will approach the interaction differently. Because the audience is different, you likely will explain the event with more detail to address the fact that they don’t go to the mall often, or you will omit specific details that your grandparents will not understand or find interesting. For instance, instead of telling them about the video game store, you might tell them about the pretzel café.

As part of your understanding of the rhetorical situation, you might summarize specific elements, again depending on the intended audience. You might speak briefly about the pretzel café to your friends but spend more time detailing the various toppings for your grandparents. If, by chance, you have previously stopped to have a pretzel, you might provide your analysis and evaluation of the service and the food. Once again, you are engaged in rhetoric by showing an understanding of and the ability to develop a strategy for approaching a particular rhetorical situation. The point is to recognize that rhetorical situations differ, depending, in this case, on the audience. Awareness of the rhetorical situation applies to academic writing as well. You change your presentation, tone, style, and other elements to fit the conditions of the situation.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-3-glance-at-critical-response-rhetoric-and-critical-thinking

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Get 50% off your first box of Home Chef! 🥙

100+ Critical Thinking Questions for Students To Ask About Anything

Critical thinkers question everything.

In an age of “fake news” claims and constant argument about pretty much any issue, critical thinking skills are key. Teach your students that it’s vital to ask questions about everything, but that it’s also important to ask the right sorts of questions. Students can use these critical thinking questions with fiction or nonfiction texts. They’re also useful when discussing important issues or trying to understand others’ motivations in general.

“Who” Critical Thinking Questions

Questions like these help students ponder who’s involved in a story and how the actions affect them. They’ll also consider who’s telling the tale and how reliable that narrator might be.

- Is the protagonist?

- Is the antagonist?

- Caused harm?

- Is harmed as a result?

- Was the most important character?

- Is responsible?

- Is most directly affected?

- Should have won?

- Will benefit?

- Would be affected by this?

- Makes the decisions?

“What” Critical Thinking Questions

Ask questions that explore issues more deeply, including those that might not be directly answered in the text.

- Background information do I know or need to know?

- Is the main message?

- Are the defining characteristics?

- Questions or concerns do I have?

- Don’t I understand?

- Evidence supports the author’s conclusion?

- Would it be like if … ?

- Could happen if … ?

- Other outcomes might have happened?

- Questions would you have asked?

- Would you ask the author about … ?

- Was the point of … ?

- Should have happened instead?

- Is that character’s motive?

- Else could have changed the whole story?

- Can you conclude?

- Would your position have been in that situation?

- Would happen if … ?

- Makes your position stronger?

- Was the turning point?

- Is the point of the question?

- Did it mean when … ?

- Is the other side of this argument?

- Was the purpose of … ?

- Does ______ mean?

- Is the problem you are trying to solve?

- Does the evidence say?

- Assumptions are you making?

- Is a better alternative?

- Are the strengths of the argument?

- Are the weaknesses of the argument?

- Is the difference between _______ and _______?

“Where” Critical Thinking Questions

Think about where the story is set and how it affects the actions. Plus, consider where and how you can learn more.

- Would this issue be a major problem?

- Are areas for improvement?

- Did the story change?

- Would you most often find this problem?

- Are there similar situations?

- Would you go to get answers to this problem?

- Can this be improved?

- Can you get more information?

- Will this idea take us?

“When” Critical Thinking Questions

Think about timing and the effect it has on the characters or people involved.

- Is this acceptable?

- Is this unacceptable?

- Does this become a problem?

- Is the best time to take action?

- Will we be able to tell if it worked?

- Is it time to reassess?

- Should we ask for help?

- Is the best time to start?

- Is it time to stop?

- Would this benefit society?

- Has this happened before?

“Why” Critical Thinking Questions

Asking “why” might be one of the most important parts of critical thinking. Exploring and understanding motivation helps develop empathy and make sense of difficult situations.

- Is _________ happening?

- Have we allowed this to happen?

- Should people care about this issue?

- Is this a problem?

- Did the character say … ?

- Did the character do … ?

- Is this relevant?

- Did the author write this?

- Did the author decide to … ?

- Is this important?

- Did that happen?

- Is it necessary?

- Do you think I (he, she, they) asked that question?

- Is that answer the best one?

- Do we need this today?

“How” Critical Thinking Questions

Use these questions to consider how things happen and whether change is possible.

- Do we know this is true?

- Does the language used affect the story?

- Would you solve … ?

- Is this different from other situations?

- Is this similar to … ?

- Would you use … ?

- Does the location affect the story?

- Could the story have ended differently?

- Does this work?

- Could this be harmful?

- Does this connect with what I already know?

- Else could this have been handled?

- Should they have responded?

- Would you feel about … ?

- Does this change the outcome?

- Did you make that decision?

- Does this benefit you/others?

- Does this hurt you/others?

- Could this problem be avoided?

More Critical Thinking Questions

Here are more questions to help probe further and deepen understanding.

- Can you give me an example?

- Do you agree with … ?

- Can you compare this with … ?

- Can you defend the actions of … ?

- Could this be interpreted differently?

- Is the narrator reliable?

- Does it seem too good to be true?

- Is ______ a fact or an opinion?

What are your favorite critical thinking questions? Come exchange ideas on the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook .

Plus, check out 10 tips for teaching kids to be awesome critical thinkers ., you might also like.

5 Critical Thinking Skills Every Kid Needs To Learn (And How To Teach Them)

Teach them to thoughtfully question the world around them. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Writing to Think: Critical Thinking and the Writing Process

“Writing is thinking on paper.” (Zinsser, 1976, p. vii)

Google the term “critical thinking.” How many hits are there? On the day this tutorial was completed, Google found about 65,100,000 results in 0.56 seconds. That’s an impressive number, and it grows more impressively large every day. That’s because the nation’s educators, business leaders, and political representatives worry about the level of critical thinking skills among today’s students and workers.

What is Critical Thinking?

Simply put, critical thinking is sound thinking. Critical thinkers work to delve beneath the surface of sweeping generalizations, biases, clichés, and other quick observations that characterize ineffective thinking. They are willing to consider points of view different from their own, seek and study evidence and examples, root out sloppy and illogical argument, discern fact from opinion, embrace reason over emotion or preference, and change their minds when confronted with compelling reasons to do so. In sum, critical thinkers are flexible thinkers equipped to become active and effective spouses, parents, friends, consumers, employees, citizens, and leaders. Every area of life, in other words, can be positively affected by strong critical thinking.

Released in January 2011, an important study of college students over four years concluded that by graduation “large numbers [of American undergraduates] didn’t learn the critical thinking, complex reasoning and written communication skills that are widely assumed to be at the core of a college education” (Rimer, 2011, para. 1). The University designs curriculum, creates support programs, and hires faculty to help ensure you won’t be one of the students “[showing]no significant gains in . . . ‘higher order’ thinking skills” (Rimer, 2011, para. 4). One way the University works to help you build those skills is through writing projects.

Writing and Critical Thinking

Say the word “writing” and most people think of a completed publication. But say the word “writing” to writers, and they will likely think of the process of composing. Most writers would agree with novelist E. M. Forster, who wrote, “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” (Forster, 1927, p. 99). Experienced writers know that the act of writing stimulates thinking.

Inexperienced and experienced writers have very different understandings of composition. Novice writers often make the mistake of believing they have to know what they’re going to write before they can begin writing. They often compose a thesis statement before asking questions or conducting research. In the course of their reading, they might even disregard material that counters their pre-formed ideas. This is not writing; it is recording.

In contrast, experienced writers begin with questions and work to discover many different answers before settling on those that are most convincing. They know that the act of putting words on paper or a computer screen helps them invent thought and content. Rather than trying to express what they already think, they express what the act of writing leads them to think as they put down words. More often than not, in other words, experienced writers write their way into ideas, which they then develop, revise, and refine as they go.

What has this notion of writing to do with critical thinking? Everything.

Consider the steps of the writing process: prewriting, outlining, drafting, revising, editing, seeking feedback, and publishing. These steps are not followed in a determined or strict order; instead, the effective writer knows that as they write, it may be necessary to return to an earlier step. In other words, in the process of revision, a writer may realize that the order of ideas is unclear. A new outline may help that writer re-order details. As they write, the writer considers and reconsiders the effectiveness of the work.

The writing process, then, is not just a mirror image of the thinking process: it is the thinking process. Confronted with a topic, an effective critical thinker/writer

- asks questions

- seeks answers

- evaluates evidence

- questions assumptions

- tests hypotheses

- makes inferences

- employs logic

- draws conclusions

- predicts readers’ responses

- creates order

- drafts content

- seeks others’ responses

- weighs feedback

- criticizes their own work

- revises content and structure

- seeks clarity and coherence

Example of Composition as Critical Thinking

“Good writing is fueled by unanswerable questions” (Lane, 1993, p. 15).

Imagine that you have been asked to write about a hero or heroine from history. You must explain what challenges that individual faced and how they conquered them. Now imagine that you decide to write about Rosa Parks and her role in the modern Civil Rights movement. Take a moment and survey what you already know. She refused to get up out of her seat on a bus so a White man could sit in it. She was arrested. As a result, Blacks in Montgomery protested, influencing the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Martin Luther King, Jr. took up leadership of the cause, and ultimately a movement was born.

Is that really all there is to Rosa Parks’s story? What questions might a thoughtful writer ask? Here a few:

- Why did Rosa Parks refuse to get up on that particular day?

- Was hers a spontaneous or planned act of defiance?

- Did she work? Where? Doing what?

- Had any other Black person refused to get up for a White person?

- What happened to that individual or those individuals?

- Why hadn’t that person or those persons received the publicity Parks did?

- Was Parks active in Civil Rights before that day?

- How did she learn about civil disobedience?

Even just these few questions could lead to potentially rich information.

Factual information would not be enough, however, to satisfy an assignment that asks for an interpretation of that information. The writer’s job for the assignment is to convince the reader that Parks was a heroine; in this way the writer must make an argument and support it. The writer must establish standards of heroic behavior. More questions arise:

- What is heroic action?

- What are the characteristics of someone who is heroic?

- What do heroes value and believe?

- What are the consequences of a hero’s actions?

- Why do they matter?

Now the writer has even more research and more thinking to do.

By the time they have raised questions and answered them, raised more questions and answered them, and so on, they are ready to begin writing. But even then, new ideas will arise in the course of planning and drafting, inevitably leading the writer to more research and thought, to more composition and refinement.

Ultimately, every step of the way over the course of composing a project, the writer is engaged in critical thinking because the effective writer examines the work as they develop it.

Why Writing to Think Matters

Writing practice builds critical thinking, which empowers people to “take charge of [their] own minds” so they “can take charge of [their] own lives . . . and improve them, bringing them under [their] self command and direction” (Foundation for Critical Thinking, 2020, para. 12). Writing is a way of coming to know and understand the self and the changing world, enabling individuals to make decisions that benefit themselves, others, and society at large. Your knowledge alone – of law, medicine, business, or education, for example – will not be enough to meet future challenges. You will be tested by new unexpected circumstances, and when they arise, the open-mindedness, flexibility, reasoning, discipline, and discernment you have learned through writing practice will help you meet those challenges successfully.

Forster, E.M. (1927). Aspects of the novel . Harcourt, Brace & Company.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2020, June 17). Our concept and definition of critical thinking . https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-concept-of-critical-thinking/411

Lane, B. (1993). After the end: Teaching and learning creative revision . Heinemann.

Rimer, S. (2011, January 18). Study: Many college students not learning to think critically . The Hechinger Report. https://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/article24608056.html

Zinsser, W. (1976). On writing well: The classic guide to writing nonfiction . HarperCollins.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

a. illustrate--This answer is incorrect. b. expand. c. explain. d. interrupt. ___________________ are created to describe dramatic or humorous scenes that will eventually be played out by actors. Screenplays. Dialogue is the essence of real-life conversation. True. Real people talk over each other, they use half phrases, they jump around ...

15 of 15. Quiz yourself with questions and answers for Creative Writing Unit 5 Quiz, so you can be ready for test day. Explore quizzes and practice tests created by teachers and students or create one from your course material.

written in journal style. narrative essay. a story that is based on fact but reads like a fiction story. creative essay truth. it should be developed with vivid details. creative essay (author) author should utilize any devices used in other forms of writing. creative essay truth 2. it is solely based on experiences that took place in reality.

Creative writing is any composition — fiction, poetry, or non-fiction — that expresses ideas in an imaginative and unusual manner. Creative texts are texts that are non-technical, non-academic and non-journalistic, and are read for pleasure rather than for information. In this sense, creative writing is a process-oriented term for what has ...

The Ultimate Cheat Sheet For Digital Thinking by Global Digital Citizen Foundation is an excellent starting point for the 'how' behind teaching critical thinking by outlining which questions to ask. It offers 48 critical thinking questions useful for any content area or even grade level with a little re-working/re-wording. Enjoy the list!

Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. 3. Clarify Thinking. When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier.

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct. Someone with critical thinking skills can: Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build, and appraise arguments. Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

Critical thinking is a key skill needed for everyday life. It should be applied to all aspects of a learner's studies, no matter their age or ability. It's a way of adding perspective, questioning intent and understanding ways of improving. Take a minute to watch this short video. It will help you to understand what we mean by Critical ...

CRITICAL THINKING AND CREATIVE WRITING OPEN ELECTIVE PAPER Volume - I (As per National Education Policy 2020) ... Question Paper Pattern ….. 78 11.Model Question Paper ….. 79 . 4 UNIT- 1 HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF SHORT STORIES A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and

Critical thinking starts with understanding the content that you are learning. This step involves clarifying the logic and interrelations of the content by actively engaging with the materials (e.g., text, articles, and research papers). You can take notes, highlight key points, and make connections with prior knowledge to help you engage.

writing. 1.1 Critical Thinking and Creative Writing A lack of critical thinking skills among university students has given rise to the concern of university lecturers in many European countries, in the United States, and elsewhere. There is an urgent need for theories that contribute to new ways of understanding how students learn, and meth-

5. CT is a way of thinking that tries to seek the trush and objectivity by questioning, looking for alternatives. 6. Its objective is the growth of individuals as distinctive persons. Critical Thinking in Class. Approaches to work CT in Class. 1. Decision-making processes, problem solving or argument analysis. 2.

Introduction; 3.1 Identity and Expression; 3.2 Literacy Narrative Trailblazer: Tara Westover; 3.3 Glance at Genre: The Literacy Narrative; 3.4 Annotated Sample Reading: from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass; 3.5 Writing Process: Tracing the Beginnings of Literacy; 3.6 Editing Focus: Sentence Structure; 3.7 Evaluation: Self-Evaluating; 3.8 Spotlight on …

In an age of "fake news" claims and constant argument about pretty much any issue, critical thinking skills are key. Teach your students that it's vital to ask questions about everything, but that it's also important to ask the right sorts of questions. Students can use these critical thinking questions with fiction or nonfiction texts.

Creative Writing Quiz questions and Answers Units 5-8. 60 terms. analisebutler. Preview. Creative Writing Unit 3 Fiction First. 15 terms. JoeMama_2_0_0_ Preview. Literature Test. 69 terms. BOOVDANCER. Preview. Vocab week 7(5) 20 terms. Isaac_Velasquez556. Preview. Creative Writing: Unit 3. 21 terms. kaykay_36. Preview. College and Career ...

"Writing is thinking on paper." (Zinsser, 1976, p. vii) Google the term "critical thinking." How many hits are there? On the day this tutorial was completed, Google found about 65,100,000 results in 0.56 seconds. That's an impressive number, and it grows more impressively large every day. That's because the nation's educators, business leaders, and political…

40355. Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap. City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative. This text offers instruction in analytical, critical, and argumentative writing, critical thinking, research strategies, information literacy, and proper documentation through the study of literary works from major genres, while ...