Designing Research Assignments: Scaffolding Research Assignments

- Student Research Needs

- Assignment Guidelines

- Assignment Ideas

- Scaffolding Research Assignments

- BEAM Method

What is scaffolding?

Educational scaffolding refers to the process of providing temporary supports for learners to guide them towards achieving a goal or completing a complex task.

Scaffolding can take many forms. One type of scaffolding is called process scaffolding, where a complex task, such as a research paper is broken down into smaller, more manageable parts.

Attribution

Portions of this page were modified from Lehigh University Libraries' Information Literacy in ENG2: An Instructor Guide and Modesto Junior College's Designing Research Assignments Guide .

Scaffolding a Research Assignment

| Assignment Ideas for Each Stage | |

|---|---|

| Selecting a topic | |

| Finding background information/Presearch | |

| Research | |

| Source evaluation | |

| Draft | |

| Final Draft | |

Scaffolding Suggestions

| Research Stage | Support Provided |

|---|---|

| Selecting a topic | Students often have considerable difficulty selecting a topic and coming up with an appropriate research question. |

| Research |

- << Previous: Assignment Ideas

- Next: BEAM Method >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://columbiacollege-ca.libguides.com/designing_assignments

- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Designing Research Assignments

- Scaffolding

- Rethinking Requirements

- The BEAM Method

- Threshold Concepts

Assuming Students are Good at Research

Students are very good at finding things online. They are less adept at evaluating the resources they locate and utilizing them to support or refute a point they are making or engaging in the academic conversation on a given topic.

Instead of assuming students are good at research, consider designing research assignments as though students know little to nothing about the academic research process and scaffold assignments as much as possible. This allows students to build a foundation for their future work. Throughout the assignment, incorporate elements of threshold concepts in information literacy alongside those from your discipline.

Scaffolding Examples

One effective method of scaffolding is to take a complex assignment and break it into smaller components. Providing formative feedback on the earlier assignments will help students master each step in the process before proceeding further. This type of scaffolding helps students get started on complex assignments early and ensures that they are on track throughout.

Troubleshoot Scaffolding

| “Scaffolding takes too much time.” | |

| “My students don’t like a lot of small assignments. They complain it’s too much work.” | |

| “It adds too much to my grading load." | |

| “I tried grading and giving feedback on early drafts and students just made the specific changes I suggested and expected better marks.” | |

| “I like the idea of peer review but I’m afraid that students won’t take it seriously.” | |

| “Scaffolding makes it too easy and will alienate the brighter students.” |

Adapted from Skene, Allyson and Sarah Fedko. " Assignment Scaffolding ." Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Toronto Scarborough, https://ctl.utsc.utoronto.ca/technology/sites/default/files/scaffolding.pdf.

- << Previous: Rethinking Requirements

- Next: The BEAM Method >>

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 11:17 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/researchassignments

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

Scaffolding Methods for Research Paper Writing

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Students will use scaffolding to research and organize information for writing a research paper. A research paper scaffold provides students with clear support for writing expository papers that include a question (problem), literature review, analysis, methodology for original research, results, conclusion, and references. Students examine informational text, use an inquiry-based approach, and practice genre-specific strategies for expository writing. Depending on the goals of the assignment, students may work collaboratively or as individuals. A student-written paper about color psychology provides an authentic model of a scaffold and the corresponding finished paper. The research paper scaffold is designed to be completed during seven or eight sessions over the course of four to six weeks.

Featured Resources

- Research Paper Scaffold : This handout guides students in researching and organizing the information they need for writing their research paper.

- Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection : Students use Internet search engines and Web analysis checklists to evaluate online resources then write annotations that explain how and why the resources will be valuable to the class.

From Theory to Practice

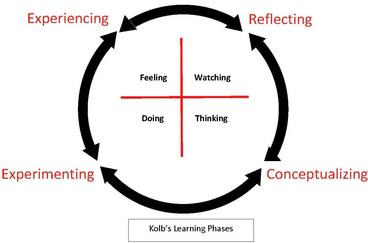

- Research paper scaffolding provides a temporary linguistic tool to assist students as they organize their expository writing. Scaffolding assists students in moving to levels of language performance they might be unable to obtain without this support.

- An instructional scaffold essentially changes the role of the teacher from that of giver of knowledge to leader in inquiry. This relationship encourages creative intelligence on the part of both teacher and student, which in turn may broaden the notion of literacy so as to include more learning styles.

- An instructional scaffold is useful for expository writing because of its basis in problem solving, ownership, appropriateness, support, collaboration, and internalization. It allows students to start where they are comfortable, and provides a genre-based structure for organizing creative ideas.

- In order for students to take ownership of knowledge, they must learn to rework raw information, use details and facts, and write.

- Teaching writing should involve direct, explicit comprehension instruction, effective instructional principles embedded in content, motivation and self-directed learning, and text-based collaborative learning to improve middle school and high school literacy.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

Computers with Internet access and printing capability

- Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Student Research Paper

- Internet Citation Checklist

- Research Paper Scoring Rubric

- Permission Form (optional)

Preparation

| 1. | Decide how you will schedule the seven or eight class sessions in the lesson to allow students time for independent research. You may wish to reserve one day each week as the “research project day.” The schedule should provide students time to plan ahead and collect materials for one section of the scaffold at a time, and allow you time to assess each section as students complete it, which is important as each section builds upon the previous one. |

| 2. | Make a copy for each student of the , the , the , the , and the . Also fill out and copy the if you will be getting parents’ permission for the research projects. |

| 3. | If necessary, reserve time in the computer lab for Sessions 2 and 8. Decide which citation website students will use to format reference citations (see Websites) and bookmark it on student computers. |

| 4. | Schedule time for research in the school media center or the computer lab between Sessions 2 and 3. |

Student Objectives

Students will

- Formulate a clear thesis that conveys a perspective on the subject of their research

- Practice research skills, including evaluation of sources, paraphrasing and summarizing relevant information, and citation of sources used

- Logically group and sequence ideas in expository writing

- Organize and display information on charts, maps, and graphs

Session 1: Research Question

| 1. | Distribute copies of the and , and read the model aloud with students. Briefly discuss how this research paper works to answer the question, The example helps students clearly see how a research question leads to a literature review, which in turn leads to analysis, original research, results, and conclusion. |

| 2. | Pass out copies of the . Explain to students that the procedures involved in writing a research paper follow in order, and each section of the scaffold builds upon the previous one. Briefly describe how each section will be completed during subsequent sessions. |

| 3. | Explain that in this session the students’ task is to formulate a research question and write it on the scaffold. The most important strategy in using this model is that students be allowed, within the assigned topic framework, to ask their research questions. Allowing students to choose their own questions gives them control over their own learning, so they are motivated to “solve the case,” to persevere even when the trail runs cold or the detective work seems unexciting. |

| 4. | Introduce the characteristics of a good research question. Explain that in a broad area such as political science, psychology, geography, or economics, a good question needs to focus on a particular controversy or perspective. Some examples include: Explain that students should take care not to formulate a research question so broad that it cannot be answered, or so narrow that it can be answered in a sentence or two. |

| 5. | Note that a good question always leads to more questions. Invite students to suggest additional questions resulting from the examples above and from the Example Research Paper Scaffold. |

| 6. | Emphasize that good research questions are open-ended. Open-ended questions can be solved in more than one way and, depending upon interpretation, often have more than one correct answer, such as the question, Closed questions have only one correct answer, such as, Open-ended questions are implicit and evaluative, while closed questions are explicit. Have students identify possible problems with these research questions |

| 7. | Instruct students to fill in the first section of the Research Paper Scaffold, the Research Question, before Session 2. This task can be completed in a subsequent class session or assigned as homework. Allowing a few days for students to refine and reflect upon their research question is best practice. Explain that the next section, the Hook, should be filled in at this time, as it will be completed using information from the literature search. |

You should approve students’ final research questions before Session 2. You may also wish to send home the Permission Form with students, to make parents aware of their child’s research topic and the project due dates.

Session 2: Literature Review—Search

Prior to this session, you may want to introduce or review Internet search techniques using the lesson Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection . You may also wish to consult with the school librarian regarding subscription databases designed specifically for student research, which may be available through the school or public library. Using these types of resources will help to ensure that students find relevant and appropriate information. Using Internet search engines such as Google can be overwhelming to beginning researchers.

| 1. | Introduce this session by explaining that students will collect five articles that help to answer their research question. Once they have printed out or photocopied the articles, they will use a highlighter to mark the sections in the articles that specifically address the research question. This strategy helps students focus on the research question rather than on all the other interesting—yet irrelevant—facts that they will find in the course of their research. |

| 2. | Point out that the five different articles may offer similar answers and evidence with regard to the research question, or they may differ. The final paper will be more interesting if it explores different perspectives. |

| 3. | Demonstrate the use of any relevant subscription databases that are available to students through the school, as well as any Web directories or kid-friendly search engines (such as ) that you would like them to use. |

| 4. | Remind students that their research question can provide the keywords for a targeted Internet search. The question should also give focus to the research—without the research question to anchor them, students may go off track. |

| 5. | Explain that information found in the articles may lead students to broaden their research question. A good literature review should be a way of opening doors to new ideas, not simply a search for the data that supports a preconceived notion. |

| 6. | Make students aware that their online search results may include abstracts, which are brief summaries of research articles. In many cases the full text of the articles is available only through subscription to a scholarly database. Provide examples of abstracts and scholarly articles so students can recognize that abstracts do not contain all the information found in the article, and should not be cited unless the full article has been read. |

| 7. | Emphasize that students need to find articles from at least five different reliable sources that provide “clues” to answering their research question. Internet articles need to be printed out, and articles from print sources need to be photocopied. Each article used on the Research Paper Scaffold needs to yield several relevant facts, so students may need to collect more than five articles to have adequate sources. |

| 8. | Remind students to gather complete reference information for each of their sources. They may wish to photocopy the title page of books where they find information, and print out the homepage or contact page of websites. |

| 9. | Allow students at least a week for research. Schedule time in the school media center or the computer lab so you can supervise and assist students as they search for relevant articles. Students can also complete their research as homework. |

Session 3: Literature Review—Notes

Students need to bring their articles to this session. For large classes, have students highlight relevant information (as described below) and submit the articles for assessment before beginning the session.

| 1. | Have students find the specific information in each article that helps answer their research question, and highlight the relevant passages. Check that students have correctly identified and marked relevant information before allowing them to proceed to the Literature Review section on the . |

| 2. | Instruct students to complete the Literature Review section of the Research Paper Scaffold, including the last name of the author and the publication date for each article (to prepare for using APA citation style). |

| 3. | Have students list the important facts they found in each article on the lines numbered 1–5, as shown on the . Additional facts can be listed on the back of the handout. Remind students that if they copy directly from a text they need to put the copied material in quotation marks and note the page number of the source. Students may need more research time following this session to find additional information relevant to their research question. |

| 4. | Explain that interesting facts that are not relevant for the literature review section can be listed in the section labeled Hook. All good writers, whether they are writing narrative, persuasive, or expository text, need to engage or “hook” the reader’s interest. Facts listed in the Hook section can be valuable for introducing the research paper. |

| 5. | Use the Example Research Paper Scaffold to illustrate how to fill in the first and last lines of the Literature Review entry, which represent topic and concluding sentences. These should be filled in only all the relevant facts from the source have been listed, to ensure that students are basing their research on facts that are found in the data, rather than making the facts fit a preconceived idea. |

| 6. | Check students’ scaffolds as they complete their first literature review entry, to make sure they are on track. Then have students complete the other four sections of the Literature Review Section in the same manner. |

Checking Literature Review entries on the same day is best practice, as it gives both you and the student time to plan and address any problems before proceeding. Note that in the finished product this literature review section will be about six paragraphs, so students need to gather enough facts to fit this format.

Session 4: Analysis

| 1. | Explain that in this session students will compare the information they have gathered from various sources to identify themes. |

| 2. | Explain the process of analysis using the . Show how making a numbered list of possible themes, drawn from the different perspectives proposed in the literature, can be useful for analysis. In the Example Research Paper Scaffold, there are four possible explanations given for the effects of color on mood. Remind students that they can refer to the for a model of how the analysis will be used in the final research paper. |

| 3. | Have students identify common themes and possible answers to their own research question by reviewing the topic and concluding sentences in their literature review. Students may identify only one main idea in each source, or they may find several. Instruct students to list the ideas and summarize their similarities and differences in the space provided for Analysis on the scaffold. |

| 4. | Check students’ Analysis section entries to make sure they have included theories that are consistent with their literature review. Return the Research Paper Scaffolds to students with comments and corrections. In the finished research paper, the analysis section will be about one paragraph. |

Session 5: Original Research

Students should design some form of original research appropriate to their topics, but they do not necessarily have to conduct the experiments or surveys they propose. Depending on the appropriateness of the original research proposals, the time involved, and the resources available, you may prefer to omit the actual research or use it as an extension activity.

| 1. | During this session, students formulate one or more possible answers to the research question (based upon their analysis) for possible testing. Invite students to consider and briefly discuss the following questions: |

| 2. | Explain the difference between and research. Quantitative methods involve the collection of numeric data, while qualitative methods focus primarily on the collection of observable data. Quantitative studies have large numbers of participants and produce a large collection of data (such as results from 100 people taking a 10-question survey). Qualitative methods involve few participants and rely upon the researcher to serve as a “reporter” who records direct observations of a specific population. Qualitative methods involve more detailed interviews and artifact collection. |

| 3. | Point out that each student’s research question and analysis will determine which method is more appropriate. Show how the research question in the Example Research Paper Scaffold goes beyond what is reported in a literature review and adds new information to what is already known. |

| 4. | Outline criteria for acceptable research studies, and explain that you will need to approve each student’s plan before the research is done. The following criteria should be included: ). |

| 5. | Inform students of the schedule for submitting their research plans for approval and completing their original research. Students need to conduct their tests and collect all data prior to Session 6. Normally it takes one day to complete research plans and one to two weeks to conduct the test. |

Session 6: Results (optional)

| 1. | If students have conducted original research, instruct them to report the results from their experiments or surveys. Quantitative results can be reported on a chart, graph, or table. Qualitative studies may include data in the form of pictures, artifacts, notes, and interviews. Study results can be displayed in any kind of visual medium, such as a poster, PowerPoint presentation, or brochure. |

| 2. | Check the Results section of the scaffold and any visuals provided for consistency, accuracy, and effectiveness. |

Session 7: Conclusion

| 1. | Explain that the Conclusion to the research paper is the student’s answer to the research question. This section may be one to two paragraphs. Remind students that it should include supporting facts from both the literature review and the test results (if applicable). |

| 2. | Encourage students to use the Conclusion section to point out discrepancies and similarities in their findings, and to propose further studies. Discuss the Conclusion section of the from the standpoint of these guidelines. |

| 3. | Check the Conclusion section after students have completed it, to see that it contains a logical summary and is consistent with the study results. |

Session 8: References and Writing Final Draft

| 1. | Show students how to create a reference list of cited material, using a model such as American Psychological Association (APA) style, on the Reference section of the scaffold. |

| 2. | Distribute copies of the and have students refer to the handout as they list their reference information in the Reference section of the scaffold. Check students’ entries as they are working to make sure they understand the format correctly. |

| 3. | Have students access the citation site you have bookmarked on their computers. Demonstrate how to use the template or follow the guidelines provided, and have students create and print out a reference list to attach to their final research paper. |

| 4. | Explain to students that they will now use the completed scaffold to write the final research paper using the following genre-specific strategies for expository writing: and (unless the research method was qualitative). |

| 5. | Distribute copies of the and go over the criteria so that students understand how their final written work will be evaluated. |

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Observe students’ participation in the initial stages of the Research Paper Scaffold and promptly address any errors or misconceptions about the research process.

- Observe students and provide feedback as they complete each section of the Research Paper Scaffold.

- Provide a safe environment where students will want to take risks in exploring ideas. During collaborative work, offer feedback and guidance to those who need encouragement or require assistance in learning cooperation and tolerance.

- Involve students in using the Research Paper Scoring Rubric for final evaluation of the research paper. Go over this rubric during Session 8, before they write their final drafts.

- Strategy Guides

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Library Instruction

- Topics for Library Instruction

- Copyright Essentials for Instruction

- Scaffolding Research Assignments

- Open Educational Resources This link opens in a new window

- Embed a Library Guide in Canvas

- Embed a Database List in Canvas

- Embed Library Search Box in Canvas

- Link Journal Articles in Canvas

Instructional Services Librarian

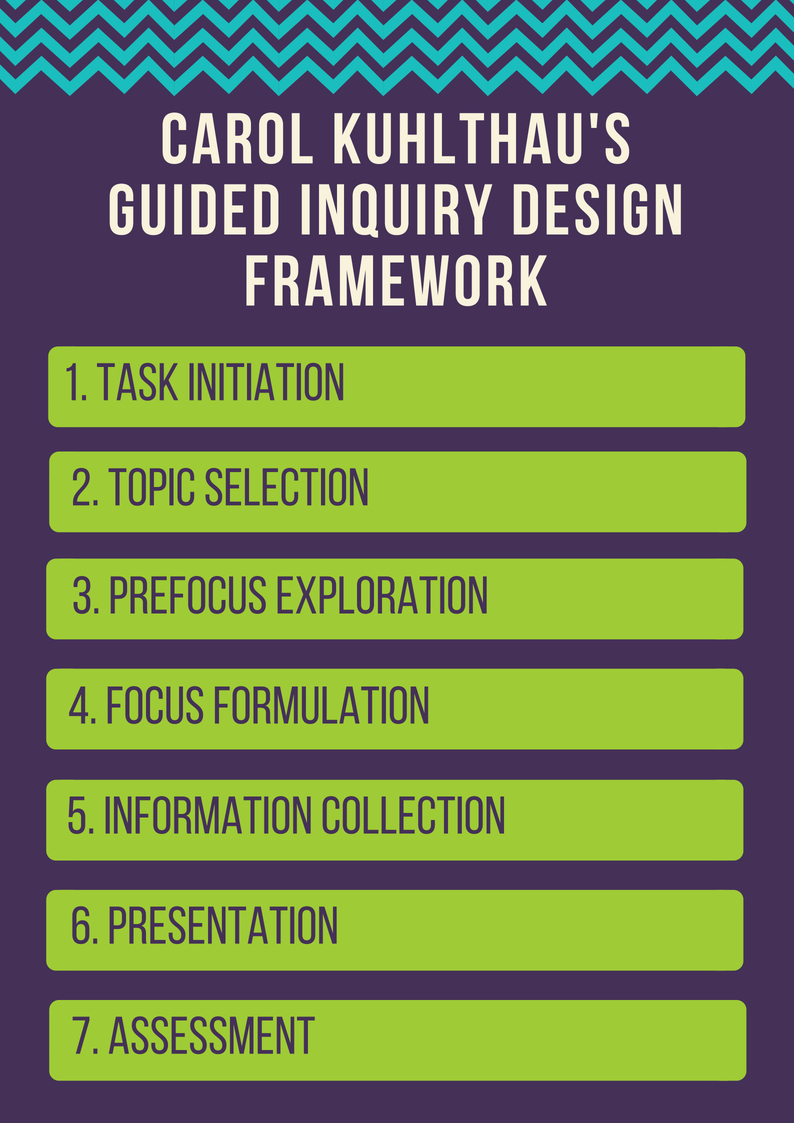

What is Assignment Scaffolding?

Assignment scaffolding is a way to systematically structure assignments (and course material) to support student learning. Scaffolding breaks down large ideas or tasks into smaller ideas or tasks that build on each other.

For example, writing a research paper involves many different tasks and skills, as well as development of ideas and knowledge. Your learners might need to develop those skills and relevant knowledge over time. Breaking down the assignment into smaller (and perhaps lower-order) tasks allows your learners to gain the skills and knowledge that are required to write the final paper. It also allows faculty the chance to periodically review the student's progress to see if they need more assistance with a particular skill, or whether they need support in developing their knowledge.

Please feel free to reach out if you are interested in scaffolding or revising an assignment. Librarians are happy to help faculty use this rewarding strategy to revise or design research assignments!

Scaffolded Assignment Ideas & Options

Below are some ideas that can be used to scaffold or revise assignments. There are many other strategies and assignments out there but this list can provide a starting place for those interested in using scaffolded assignments.

| Skills to Develop | Potential Assignments |

|---|---|

| Find Sources | Research journal/log Annotated bibliography Submit source for review, with an explanation of why it is useful & relevant |

| Evaluate Sources |

In depth analysis of author of source(s) List of supporting/refuting evidence

|

| Reading | |

| Taking Notes & Annotating Sources | |

| Summarizing Source(s) |

or

|

| Comparing Sources |

|

| Synthesis |

|

| Pre-writing |

|

- << Previous: Copyright Essentials for Instruction

- Next: TurnItIn >>

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 1:41 PM

- URL: https://resources.library.lemoyne.edu/instruction

The effects of scaffolding in the classroom: support contingency and student independent working time in relation to student achievement, task effort and appreciation of support

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2015

- Volume 43 , pages 615–641, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Janneke van de Pol 1 , 2 ,

- Monique Volman 1 ,

- Frans Oort 1 &

- Jos Beishuizen 3

138k Accesses

91 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Teacher scaffolding, in which teachers support students adaptively or contingently , is assumed to be effective. Yet, hardly any evidence from classroom studies exists. With the current experimental classroom study we investigated whether scaffolding affects students’ achievement, task effort, and appreciation of teacher support, when students work in small groups. We investigated both the effects of support quality (i.e., contingency) and the duration of the independent working time of the groups. Thirty social studies teachers of pre-vocational education and 768 students (age 12–15) participated. All teachers taught a five-lesson project on the European Union and the teachers in the scaffolding condition additionally took part in a scaffolding intervention. Low contingent support was more effective in promoting students’ achievement and task effort than high contingent support in situations where independent working time was low (i.e. help was frequent). In situations where independent working time was high (i.e., help was less frequent), high contingent support was more effective than low contingent support in fostering students’ achievement (when correcting for students’ task effort). In addition, higher levels of contingent support resulted in a higher appreciation of support. Scaffolding, thus, is not unequivocally effective; its effectiveness depends, among other things, on the independent working time of the groups and students’ task effort. The present study is one of the first experimental study on scaffolding in an authentic classroom context, including factors that appear to matter in such an authentic context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Vygotsky and a Global Perspective on Scaffolding in Learning Mathematics

Laboratory-Based Scaffolding Strategies for Learning School Science

Scaffolding or simplifying: students’ perception of support in Swedish compulsory school

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The metaphor of scaffolding is derived from construction work where it represents a temporary structure that is used to erect a building. In education, scaffolding refers to support that is tailored to students’ needs. This metaphor is alluring to practice as it appeals to teachers’ imagination (Saban et al. 2007 ). The metaphor, moreover, also appeals to educational scientists: an abundance of research has been performed on scaffolding in the last decade (Van de Pol et al. 2010 ).

Scaffolding is claimed to be effective (e.g., Roehler and Cantlon 1997 ). However, most research on scaffolding in the classroom has been correlational until now. The main question of the current experimental study is: What is the effect of teacher scaffolding on students’ achievement, task effort, and appreciation of support in a classroom setting?

- Scaffolding

Scaffolding represents high quality support (e.g., Seidel and Shavelson 2007 ). The metaphor of scaffolding is derived from mother–child observations and has been applied to many other contexts, such as computer environments (Azevedo and Hadwin 2005 ; Cuevas et al. 2002 ; Feyzi-Behnagh et al. 2013 ; Rasku-Puttonen et al. 2003 ; Simons and Klein 2007 ), tutoring settings (e.g., Chi et al. 2001 ) and classroom settings (e.g., Mercer and Fisher 1992 ; Roll et al. 2012 ). Scaffolding is closely related to the socio-cultural theory of Vygotsky ( 1978 ) and especially to the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD is constructed through collaborative interaction, mediated by verbal interaction. Student’s current or actual understanding is developed in these interactions towards their potential understanding. Scaffolding can be seen as the support a teacher offers to move the student toward his/her potential understanding (Wood et al. 1976 ).

More specifically, scaffolding refers to support that is contingent , faded , and aimed at the transfer of responsibility for a task or learning (Van de Pol et al. 2010 ). Contingent support (Wood et al. 1978 ) represents support that is tailored to a student’s understanding. Via fading, i.e., decreasing support, the responsibility for learning can be transferred which is the aim of scaffolding. However, this transfer is probably more effective when implemented contingently. Because contingency is a necessary condition for scaffolding, we focus on this crucial aspect.

Wood et al. ( 1978 ) further specified the concept of contingency by focusing on the degree of control that support exerts. They labelled support as ‘contingent’ when either the tutor increased the degree of control in reaction to student failure or decreased the degree of control in reaction to student success. This is called the contingent shift principle . This specification of contingency shows that the degree of control per se does not determine whether contingent teaching or scaffolding takes place or not. It is the tailored adaptation to a student’s understanding that determines contingency. Most studies on scaffolding did not use such a dynamic operationalization of scaffolding but merely focused on the teachers’ behaviour only.

Scaffolding and achievement

The way teachers interact with students affects students’ achievement (Praetorius et al. 2012 ). Scaffolding and more specifically contingent support represents intervening in such a way that the learner can succeed at the task (Mattanah et al. 2005 ). Contingent support continually provides learners with problems of controlled complexity; it makes the task manageable at any time (Wood and Wood 1996 ).

Stone noted that it is unclear how or why contingent support may work (Stone 1998a , b ). And until now the question ‘What are the mechanisms of contingent support?’ has still not been answered (Van de Pol et al. 2010 ). However, some suggestions have been made in the literature and three elements seem to play a role: (1) the level of cognitive processing; deep versus superficial processing of information, (2) making connections to existing mental models in long term memory, and (3) available cognitive resources. If the level of control is too high for a student (i.e., the support is non-contingent as too much help is given), superficial processing of the information is assumed. The student is not challenged to actively process the information and therefore does not actively make connections with existing knowledge or an existing mental model in the long term memory (e.g., Wittwer and Renkl 2008 ; Wittwer et al. 2010 ). In addition, it is assumed that attending to redundant information (information that is already known) “might prevent learners from processing more elaborate information and, thus, from engaging in more meaningful activities that directly foster learning cf. Kalyuga 2007 ; McNamara and Kintsch 1996 ; Wittwer and Renkl 2008 ; Wannarka and Ruhl 2008 ).” (Wittwer et al. 2010 , p. 74).

If the level of control is too low for a student (i.e., the support is non-contingent as too little help is given) deep processing cannot take place. The student cannot make connections with his/her existing knowledge. The cognitive load of processing the information is too high (Wittwer et al. 2010 ).

If the level of control fits the students’ understanding, the student has sufficient cognitive resources to actively process the information provided and is able to make connections between the new information and the existing knowledge in the long-term memory. “If explanations are tailored to a particular learner, they are more likely to contribute to a deep understanding, because then they facilitate the construction of a coherent mental representation of the information conveyed (a so-called situation model; see, e.g., Otero and Graesser 2001 )” (Wittwer et al. 2010 , p. 74). Only when support is adapted to a student’s understanding, connections between new information and information already stored in long-term memory are fostered (Webb and Mastergeorge 2003 ).

A body of research showed that parental scaffolding was associated with success on different sorts of outcomes such as self-regulated learning (Mattanah et al. 2005 ), block-building and puzzle construction tasks (Fidalgo and Pereira 2005 ; Wood and Middleton 1975 ) and long-division math homework (Pino-Pasternak et al. 2010 ). Pino-Pasternak et al. ( 2010 ) stressed that contingency was found to uniquely predict the children’s performance, also when taking into account pre-test measurements and other characteristics such as parenting style.

Yet, in the current study we focused on teacher scaffolding, in contrast to parental scaffolding. An essential difference between teacher scaffolding and parental scaffolding is that in the latter case, the parent knows his/her child better than a teacher knows his/her students which might facilitate the adaptation of the support. Additionally, the studies of parental scaffolding mentioned above took place in one-to-one situations which are not comparable to classroom situations where one teacher has to deal with about 30 students at a time (Davis and Miyake 2004 ).

Experimental studies on the effects of teacher scaffolding in a classroom setting are rare (cf. Kim and Hannafin 2011 ; Van de Pol et al. 2010 ). The only face-to-face, nonparental scaffolding studies using an experimental design are (one-to-one) tutoring studies with structured and/or hands-on tasks (e.g., Murphy and Messer 2000 ). The results of these tutoring studies are similar to the results of the parental scaffolding studies; contingent support generally leads to improved student performances. A non-experimental micro-level study that investigated the relation between different patterns of contingency (e.g., increased control upon poor student understanding and decreased control upon good student understanding) in a classroom setting is the study of Van de Pol and Elbers ( 2013 ). They found that contingent support was mainly related to increased student understanding when the initial student understanding was poor. Previous research—albeit mostly in out of classroom contexts—shows contingent support is related to students’ improved student achievement.

Scaffolding, task effort and appreciation of support

Most studies on contingent support have used students’ achievement as an outcome measure. Yet, other outcomes are important for students’ learning and well-being as well. One important factor in students’ success is task effort. Numerous studies have demonstrated that students’ task effort affects their achievement (Fredricks et al. 2004 ). Task effort refers to students’ effort, attention and persistence in the classroom (Fredricks et al. 2004 ; Hughes et al. 2008 ). Task effort is malleable and context-specific and the quality of teacher support, e.g., in terms of contingency, can affect task effort (Fredricks et al. 2004 ). If the contingent shift principle is applied, a tutor’s support is always responsive to the student’s understanding which in turn is hypothesized to stimulate student’s task effort; the tutor keeps the task challenging but manageable: “The child never succeeds too easily nor fails too often” (Wood et al. 1978 , p. 144). When support is contingent, the student knows which steps to take and how to proceed independently. When support is non-contingent, students often withdraw from the task as it is beyond or beneath their reach causing respectively frustration or boredom (Wertsch 1979 ). Hardly any empirical research exists on whether and how contingent support affects task effort. The only study that we encountered was the study of Chiu ( 2004 ) in which a positive relation was found between support in which the teacher first evaluated students’ understanding (assuming that this promoted contingency) and student’s task effort.

Another important factor in students’ success is students’ appreciation of support. Students’ appreciation of support provided (e.g., because they feel that they are being taken seriously or because they feel the support was enjoyable or pleasant) may have long-term implications as support that is appreciated might encourage students to engage in further learning (Pratt and Savoy-Levine 1998 ). Wood ( 1988 ), using informal observations, reports that students who experienced contingent support seemed more positive towards their tutors. Pratt and Savoy-Levine ( 1998 ) were the first (and, to our knowledge, only) researchers who tested this hypothesis more systematically. They investigated the effects of contingent support on students’ mathematical skills by conducting an experiment with several conditions: a full contingent (all control levels), moderate contingent (several but not all control levels) and non-contingent condition (only high-control levels) tutoring condition. Students in the full and moderate contingent conditions reported less negative feelings than students in the non-contingent condition about the tutoring session. Summarising, little is known about the effects of contingent support on students’ task effort and appreciation of support.

Support contingency and independent working time in scaffolding small-group work

Quite some research exists on small-group work but the teacher’s role is still receiving relatively little attention (Webb 2009 ; Webb et al. 2006 ). Studies that focused on the teacher’s role mainly studied how collaborative group work could be stimulated. Mercer and Littleton ( 2007 ) for example focused on how teachers could stimulate high-quality discussions in small groups (called exploratory talk). Little attention has been paid to how teachers can provide high quality contingent support to students—who work in groups—with regard to the subject-matter.

Some studies investigated effects of support types (e.g., process support versus content support) on students’ learning (e.g., Dekker and Elshout-Mohr 2004 ). However, it may not be the type of support that matters, but the quality of the support (e.g., in terms of contingency). Diagnosing or evaluating students’ understanding enables contingency and this is effective. Chiu ( 2004 ) for example found that when supporting small groups with the subject-matter, evaluating students’ understanding before giving support was the key factor in how effective the support was. Although evaluation is not necessarily the same as contingency, it most probably facilitates contingency. To be able to be contingent, a teacher needs to evaluate or diagnose students’ understanding first. The present study is one of the first study in an authentic classroom context studying small-group learning that measures the actual contingency of support.

In such an authentic classroom context, not only the support quality (here, in terms of contingency) is relevant; the duration of the groups’ independent working time, should also be taken into account. It seems reasonable to assume that scaffolded or contingent support takes more time than non-scaffolded support, given that diagnosing students’ understanding first before providing support is necessary to be able to give contingent support. This makes the scaffolding process time-consuming which may result in longer periods of independent small-group work. Constructivist learning theories assume that active and independent knowledge construction promotes students’ learning (e.g., Duffy and Cunningham 1996 ). In line with this assumption some authors suggest that groups of students should be left alone working for considerable amounts of time as frequent intervention might disturb the learning process (e.g., Cohen 1994 ). Other studies, however, found that students benefit in classrooms with a lot of individual attention (Blatchford et al. 2007 ; Brühwiler and Blatchford 2007 ). Although it is not known to what extent students should work independently, it is now generally agreed that students at least need some support and guidance during the learning process and that minimal guidance does not work (e.g., Kirschner et al. 2006 ). Guidance might not only be needed to help students with the task at hand, it might also help students to stay on-task. Wannarka and Ruhl ( 2008 ) for example found that, compared to an individual seating arrangement, students who are seated in small-groups are more easily distracted. Taking both the support quality and the independent working time into account enables us to investigate the separate and joint effects of these factors. It is vital to, in addition to contingency, also include independent working time, as the positive effects of contingency might be cancelled out by (possible) negative effects of independent working time in an authentic context as ours.

The present study

In the present study we investigated the effects of scaffolding on pre-vocational students’ achievement, task effort, and appreciation of support. As opposed to previous studies, we used open-ended tasks, a real-life classroom situation and a relatively large sample size. Thirty social studies teachers and 768 students participated in this study. Seventeen teachers participated in a scaffolding intervention programme (the scaffolding condition) and 13 teachers did not (the nonscaffolding condition). We investigated the separate and joint effects of support contingency and independent working time on students’ achievement, task effort and appreciation of support using a premeasurement and a postmeasurement.

In a manipulation check, we first checked whether the increase in contingency from premeasurement to postmeasurement was higher in the scaffolding condition than in the nonscaffolding condition. Footnote 1 In addition, we tested whether the increase in independent working time per group was higher in the scaffolding condition than in the nonscaffolding condition.

With regard to students’ achievement , we hypothesized that: students’ achievement (measured with a multiple choice test and a knowledge assignment) increases more with high levels of contingent support compared to low levels of contingent support. Because the positive effects of contingency might be ruled out by the (negative) effects of independent working time, we added the latter variable in the analyses and explored whether the effect of contingency depended on the amount of independent working time. In addition, as the relation between task effort and achievement is established (as students’ task effort is known to affect achievement, Fredricks et al. 2004 ), we additionally investigated to what extent contingency, in combination with independent working time, affected students’ achievement when controlling for task effort.

Based on the lack of previous research with regard to students’ task effort and appreciation of support, we did not formulate hypotheses regarding these outcome variables. The effects of contingency and independent working time on students’ task effort and appreciation of support was explored.

Participants

The participating schools were recruited by distributing a call in the researchers’ network and in online teacher communities. The teachers were informed that the study encompassed the conduction of a five-lesson project on the European Union (EU) and that the researchers would focus on students´ learning in small groups. To arrive at random allocation to conditions, each school was alternately allocated to the scaffolding or nonscaffolding condition based on the moment of confirmation. That is, the first school that confirmed participation was allocated to the scaffolding condition, the second school to the non-scaffolding condition, the third school to the scaffolding condition etcetera. Each school only had teachers from one condition; this was to prevent teachers from different conditions to talk to each other and influence each other.

Thirty teachers from 20 Dutch schools participated in this study; 17 teachers of 11 schools were in the scaffolding condition and 13 teachers of nine schools were in the nonscaffolding condition (never more than three teachers per school). Of the participating teachers, 20 were men and 10 were women. The teachers taught social studies in the 8th grade of pre-vocational education. The average teaching experience of the teachers was 10.4 years. Each teacher participated with one class, so a total of 30 classes participated.

During the project lessons that all teachers taught during the experiment, students worked in small groups. The total number of groups was 184 and the average number of students per group was 4.15. A total of 768 students participated in this study, 455 students in the scaffolding condition and 313 students in the nonscaffolding condition. Of the 768 students, 385 were boys and 383 were girls.

T tests for independent samples showed that the schools and teachers of the scaffolding and nonscaffolding condition were comparable with regard to teachers’ years of experience ( t (28): .90, p = .38), teachers’ gender ( t (28): .51, p = .10), teachers’ subject knowledge ( t (24): 1.16, p = .26), the degree to which the classes were used to doing small-group work ( t (23): −.87, p = .39), the track of the class ( t (28): .08, p = .94), class size ( t (28): −1.32, p = .20), duration of the lessons in minutes ( t (28): −1.18, p = .25), students’ age ( t (728): −.34, p = .74), and students’ gender ( t (748): −1.65, p = .10) (see Table 1 ).

Research design

For this experimental study, we used a between-subjects design. In Table 2 , the timeline of the study can be found.

Project lessons

All teachers taught the same project on the EU for which they received instructions. This project consisted of five lessons in which the students made several open-ended assignments in groups of four (e.g., a poster, a letter about (dis)advantages of the EU etcetera). The teachers taught one project lesson per week. Teachers composed groups while mixing student gender and ability. We used the first and last project lessons for analyses (respectively premeasurement and postmeasurement). In the premeasurement lesson, the students made a brochure about the meaning of the EU for young people in their everyday lives. In the postmeasurement lesson, the students worked on an assignment called ‘Which Word Out’ (Leat 1998 ). Three concepts of a list of concepts on the EU that have much in common had to be selected and thereafter, one concept had to be left out using two reasons. The students were stimulated to collaborate by the nature of the tasks (the students needed each other) and by rules for collaboration that were introduced in all classes (such as make sure everybody understands it, help each other first before you ask the teacher etcetera).

Scaffolding intervention programme

We developed and piloted the scaffolding intervention programme in a previous study (Van de Pol et al. 2012 ) and began after we filmed the first project lesson. The programme consisted successively of: (1) video observation of project lesson 1, (2) one two-hour theoretical session (taught per school), and (3) video observations of project lessons 2–4 each followed by a reflection session of 45 min with the first author in which video fragments of the teachers’ own lessons were watched and reflected upon. Finally, all teachers taught project lesson 5 that was videotaped. This fifth lesson was not part of the scaffolding intervention programme; it served as a postmeasurement.

The first author, who was experienced, taught the programme. The reflection sessions took place individually (teacher + 1st author) and always on the same day as the observation of the project lesson. In the theoretical session, the first author and the teachers: (a) discussed scaffolding theory and the steps of contingent teaching (Van de Pol et al. 2011 ), i.e., diagnostic strategies (step 1), checking the diagnosis (step 2), intervention strategies, (step 3), and checking students’ learning (step 4), (b) watched and analysed video examples of scaffolding, and (c) discussed and prepared the project lessons. In the subsequent four project lessons, the teachers implemented the steps of contingent teaching cumulatively.

Support quality: contingent teaching

We selected all interactions a teacher had with a small group of students about the subject-matter for analyses (i.e., interaction fragments). An interaction fragment started when the teacher approached a group and ended when the teacher left. Each interaction fragment thus consisted of a variable number of teacher and student turns, Footnote 2 depending on how long the teacher stayed with a certain group. In the premeasurement and postmeasurement respectively, the teachers in the scaffolding condition had 454 and 251 fragments and the teachers in the nonscaffolding condition had 368 and 295 fragments. We used a random selection of two interaction fragments Footnote 3 of the premeasurement and two interaction fragments of the postmeasurement per teacher for analyses and we transcribed these interaction fragments. Because we selected the interaction fragments randomly, two interaction fragments of a certain teacher’s lesson could, but must not be with the same group of students. This selection resulted in 108 interaction fragments consisting of 4073 turns (teacher + student turns).

The unit of analyses for measuring contingency was a teacher turn, a student turn, and the subsequent teacher turn (i.e., a three-turn-sequence, for coded examples see Tables 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 ). To establish the contingency of each of unit, we used the contingent shift framework (Van de Pol et al. 2012 ; based on Wood et al. 1978 ). If a teacher used more control after a student’s demonstration of poor understanding and less control after a student’s demonstration of good understanding, we labelled the support contingent. To be able to apply this framework we first coded all teacher turns and all student turns as follows.

First, we coded all teacher turns in terms of the degree of control ranging from zero to five. See Tables 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 for coded examples. Zero represented no control (i.e., the teacher is not with the group), one represented the lowest level of control (i.e., the teacher provides no new lesson content, elicits an elaborate response, and asks a broad and open question), two represented low control (i.e., the teacher provides no new content, elicits an elaborate response, mostly an elaboration or explanation of something by asking open questions that are slightly more detailed than level one questions), three represented medium control (i.e., the teacher provides no new content and elicits a short response, e.g., yes/no), four represented a high level of control (i.e., the teacher provides new content, elicits a response, and gives a hint or asks a suggestive question), and five represented high control (e.g., providing the answer). Control refers to the degree of regulation a teacher exercises in his/her support. Two researchers coded twenty percent of the data and the interrater reliability was substantial (Krippendorff’s Alpha = .71; Krippendorff 2004 ).

Second, we coded the student’s understanding demonstrated in each turn into one of the following categories: miscellaneous, no understanding can be determined, poor/no understanding, partial understanding, and good understanding (cf. Nathan and Kim 2009 ; Pino-Pasternak et al. 2010 ; see Tables 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 for an example). Two researchers coded twenty percent of the data and the interrater reliability was satisfactory (Krippendorff’s Alpha = .69). The contingency score was the percentage contingent three-turn-sequences relative to the total number of three-turn sequences per teacher per measurement occasion. This means that each class had a certain contingency score; that is, the contingency score for all students of a particular class was the same. The first author, who knew which teacher was in which condition, coded the data. We prevented bias by coding in separate rounds: first, we coded all teacher turns with regard to the degree of control; second, we coded all student turns with regard to their understanding. And only then we applied the predetermined contingency rules to all three-turn-sequences.

Independent working time

We determined the average duration (in seconds) of independent working time per group per measurement occasion (T0 and T1). We did not take short whole-class instructions (≤2 min) into account and we included this in the independent working time for each group. If the teacher provided whole-class instructions that were longer than 2 min, we started counting again after that instruction had finished and the duration of the whole-class instruction was thus not included in the independent working time for each group.

- Task effort

We measured students’ task effort in class with a questionnaire consisting of 5 items (cf. Boersma et al. 2009 ; De Bruijn et al. 2005 ). We used a five-point likert scale ranging from ‘I don’t agree at all’ to ‘I totally agree’. The internal consistency was high: the value of Cronbach’s α (Cronbach 1951 ) was .92. Kline ( 1999 ) indicated a cut-off point of .70/.80). An example item of this questionnaire is: “I worked hard on this task”.

Appreciation of support

We measured students’ appreciation of the support received with a questionnaire consisting of 3 items (cf. Boersma et al. 2009 ; De Bruijn et al. 2005 ). We used a five-point likert scale ranging from ‘I don’t agree at all’ to ‘I totally agree’. The internal consistency was high: the value of Cronbach’s α was .90. An example item of this questionnaire is: “I liked the way the teacher helped me and my group”.

Achievement: multiple choice test

We measured students’ achievement with a test that consisted of 17 multiple choice questions (each with four possible answers). We constructed the questions. An example of a question is: “The main reason for the collaboration between countries after World War II was: (a) to be able to compete more with other countries, (b) to be able to transport goods, people and services across borders freely, (c) to collaborate with regard to economic and trade matters, or (d) to be able to monitor the weapons industry. The item difficulty was sufficient as all p-values (i.e., the percentage of students that correctly answered the item) of the items were between .31 and .87 (Haladyna 1999 ). Additionally, the items were good in terms of the item discrimination (correlation between the item score and the total test score) as the mean item correlation was .33. The lowest correlation was not lower than .21; the threshold is .20 (Haladyna 1999 ). We used the number of questions answered correctly as a score in the analyses with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 17. The internal consistency was high: the value of Cronbach’s α was .79.

Achievement: knowledge assignment

We additionally measured students’ achievement with a knowledge assignment. The knowledge assignment consisted of three series of three concepts (e.g., EU, European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and European Economic Community (ECC)). The students were asked to leave out one concept and give one reason for leaving this concept out. We developed a coding scheme to code the accuracy and quality of the reasons. Each reason was awarded zero, one, or two points. We awarded zero points when the reason was inaccurate or based only on linguistic properties of the concepts (e.g., two of the three concepts contain the word ‘European’). We awarded one point when the reason was accurate but used only peripheral characteristics of the concepts (e.g., one concept is left out because the other two concepts are each other’s opposites). We awarded two points when the reason was accurate and focused on the meaning of the concepts (e.g., ECSC can be left out because they only focused on regulating the coal and steel production and the other two (EU and ECC) had broader goals that related to the economy in general). The minimum score of the knowledge assignment was 0 and the maximum score was 6. Two researchers coded over 10 % of the data and the interrater reliability was substantial (Krippendorff’s Alpha = .83).

For our analyses, we used IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.

Data screening

In our predictor variables, we only found seven missing values which we handled through the expectation–maximization algorithm. For the knowledge assignment and multiple choice test we coded missing questions as zero which meant that the answer was considered false, which is the usual procedure in school as well (this was per case never more than eight percent). For the task effort and appreciation of support questionnaire, we computed the mean scores per measurement occasion and per subscale only over the number of questions that was filled out. If a student missed all measurement occasions or if a student only completed the questionnaire or one of the knowledge tests at one single measurement occasion, we removed the case (N = 18) which made the total number of students 750 (445 in the scaffolding condition; 305 in the nonscaffolding condition).

Manipulation check

We used a repeated-measures ANOVA with condition as between groups variable, measurement occasion as within groups variable and contingency or mean independent working time as dependent variable to check the effect of the intervention on teachers’ contingency and the independent working time per group. If both the level of contingency and the independent working time appear to differ systematically between conditions over measurement occasions, we will not use ‘condition’ as an independent variable in subsequent analyses because there is more than one systematic difference between conditions. Instead, we will use the variables ‘contingency’ and ‘independent working time’ to be able to investigate the separate effects of these variables on students’ achievement, task effort, and appreciation of support.

Effects of scaffolding

To test our hypothesis about the effect of contingency on achievement and explore the effects of contingency on students’ task effort and appreciation of support, we used multilevel modelling, as the data had a nested structure (measurement occasions within students, within groups, within classes, within schools). To facilitate the interpretation of the regression coefficients, we transformed the scores of all continuous variables into z-scores (mean of zero and standard deviation of 1). We treated measurement occasions (level 1) as nested within students (level 2), students as nested within groups (level 3), groups as nested within teachers/classes (level 4) and teachers/classes as nested within schools (level 5). In comparing null models (with no predictor variables) with a variable number of levels for all dependent variables, we found that the school level (level 5) was not contributing significantly to the variance found and we therefore omitted it as a level. For the multiple choice test only, the group-level was not contributing significantly to the variance found and we therefore omitted it as a level.

We fitted four-level models fitted for each of the dependent variables separately. The independent variables in the analyses were measurement occasion (premeasurement = 0; postmeasurement = 1), contingency, and mean independent working time. We included task effort as a covariate in a separate analyses regarding achievement (multiple-choice test and knowledge assignment) as task effort is known to affect achievement (Fredricks et al. 2004 ). For each dependent variable, the model in which the intercept, and effects for teachers/classes and groups were considered random, with unrestricted covariance structure, gave the best fit and was thus used. We included the main effects of each of the independent variables and all interactions (i.e., the two-way interactions between measurement occasion and contingency, measurement occasion and independent working time, and contingency and independent working time and the three-way interaction between measurement occasion, contingency and independent working time). To test our hypothesis regarding achievement, we were specifically interested in the interaction between occasion and contingency. To check whether differences in independent working time played a role in whether contingency affected achievement, we were additionally interested in the three-way interaction between occasion, contingency, and independent working time. Finally, as we wanted to control for task effort, we included task effort as a covariate in a separate analysis.

To explore the effects of contingency on students’ task effort and appreciation of support, we were also firstly interested in the interaction effect between occasion and contingency. Secondly, we also checked the role of independent working time by looking at the three-way interaction between occasion, contingency, and independent working time.

As an indication of effect size, we reported the partial squared eta (ηp 2 ) for the manipulation check of contingency and independent working time and the explained variance the multilevel analyses (squared correlation between the students’ true scores and the estimated scores). We report only effect sizes for significant effects.

First, we verified whether the degree of the teachers’ contingency increased more from premeasurement to postmeasurement in the scaffolding condition than in the nonscaffolding condition (see Table 7 ).

The results of the repeated-measures ANOVA showed that there was a significant interaction effect of condition and measurement occasion on teachers’ contingency ( F (1,28) = 17.72, p = .00) (Fig. 1 ). The effect size can be considered large; ηp 2 was .39 (Cohen 1992 ). The degree of contingency almost doubled in the scaffolding condition (from about 50 % to about 80 %) whereas this was not the case for the nonscaffolding condition where the degree of contingency stayed between 30 and 40 %.

Average percentage contingency for the teachers of each condition compared between measurement occasions

Second, we verified whether the intervention also resulted in longer periods of independent working time for small groups, an effect that was not necessarily aimed for with the intervention (see Table 7 ). The results of the repeated-measures ANOVA showed that there was a significant interaction effect of condition and measurement occasion on the average independent working time for small groups ( F (1,22) = 11.78, p = .00) (Fig. 2 ). The effect size can be considered large; ηp 2 was .35.

Average independent working time for the groups of students of each condition compared between measurement occasions

The independent group working time almost doubled in the experimental condition from premeasurement to postmeasurement. In the scaffolding condition, each group worked independently for about 5 min on average at the premeasurement before the teacher came for support. At the postmeasurement, the duration increased to about 10 min. The average independent group working time stayed stable in the nonscaffolding condition, around 3.7 min on average.

Students’ achievement

Multiple choice test.

Only the main effect of occasion on students’ score on the multiple choice test was significant (Table 8 ). Students’ scores on the test were higher at the postmeasurement than at the premeasurement. The interaction between occasion and contingency was not significant. Our hypothesis could therefore not be confirmed based on the outcomes of the multiple choice test.

We additionally investigated whether differences in independent working time played a role in whether contingency affected achievement by looking at the three-way interaction between occasion, contingency and independent working time. This three-way interaction, however, was not significant (Table 8 ).

Finally, we additionally investigated to what extent contingency, in combination with independent working time affected students’ achievement when controlling for task effort. When taking task effort into account, the three-way interaction between occasion, contingency and independent working time was significant; medium effect size of R 2 = .30; Cohen, 1992. (Table 8 ; Fig. 3 ).

Visual representation of the three-way interaction effect of occasion, contingency, and independent working time (IWT) on the scores of the multiple choice test when controlling for task effort

When the independent working time was short, low levels of contingency resulted in an increase in scores on the multiple choice test whereas when the independent working time was long, high levels of contingency resulted in an increase in scores.

Knowledge assignment

Again, only the main effect of occasion on students’ score on the knowledge assignment was significant (Table 9 ). Students’ scores on the knowledge assignment were higher at the postmeasurement than at the premeasurement. The interaction between occasion and contingency was not significant. Our hypothesis could therefore not be confirmed based on the outcomes of the knowledge assignment.

We additionally investigated whether differences in independent working time played a role in whether contingency affected achievement by looking at the three-way interaction between occasion, contingency and independent working time. This three-way interaction was not significant (Table 9 ). In addition, when adding task effort as a covariate, the three-way-interaction remained non-significant (Table 9 ).

Students’ task effort

The main effect of occasion on students’ task effort was significant (Table 10 ); students were less on-task at the postmeasurement than at the premeasurement.

The two-way interaction between occasion and contingency was not significant, but the three-way interaction of occasion, contingency, and independent working time on students’ task effort was significant (small effect size of R 2 = .04; Cohen 1992 ). The effects of contingency were found to be different for short and long periods of independent working time (see Table 10 ; Fig. 4 ).

Visual representation of the three-way interaction effect of occasion, contingency, and independent working time on task effort

When the independent working time was short, low levels of contingency resulted in an increase in task effort. When the independent working time was long, both high levels and low levels of contingency resulted in a decrease of task effort. In this case (i.e., high levels of independent working time), the decrease in task effort was smaller with high levels of contingency than with low levels of contingency.

Students’ appreciation of support

For students’ appreciation of support, only the main effect of contingency was significant (small effect size of R 2 = .04; Cohen 1992 ). Regardless of the measurement occasion or the independent working time, higher levels of contingency were related to higher appreciation of support (Table 11 ).

With the current study, we sought to advance our understanding of the effects of scaffolding on students’ achievement, task effort, and appreciation of support. We took both the support contingency and the independent working time into account to identify the effects of scaffolding in an authentic classroom situation. This study is one of few studies on classroom scaffolding with an experimental design. With this study, we made four contributions to the current knowledge base of classroom scaffolding.

First, our manipulation check showed that teachers were able to increase the degree of contingency in their support. This increase was accompanied by an increase of the independent working time for the groups.

Second, when controlling for task effort, low contingent support only resulted in improved achievement when students worked independently for short periods of time whereas high contingent support only resulted in improved achievement students worked independently for long periods of time.

Third, low contingent support resulted in an increase of task effort when students worked for short periods of time only; high contingent support never resulted in an increase of task effort but slightly prevented loss in task effort when students worked independently for long periods of time.

Fourth, appreciation of support was related to higher levels of contingency. These four contributions are elaborated below.

First, teachers who participated in the scaffolding programme increased the contingency of their support more than teachers who did not participate in this programme. In previous research, this has not always been the case. In a study of Bliss et al. ( 1996 ) for example, teachers—who participated in a professional development programme on scaffolding—kept struggling with the application of scaffolding in their classrooms. An unintended effect of our programme (that is, we did not focus on this aspect in our programme) was that in the classrooms of teachers who learned to scaffold, the independent working time for small groups also increased. This is probably due to the fact that high contingent support—for which diagnosing students’ understanding first before providing support is necessary—takes longer than low contingent support. As transferring the responsibility for a task to the learner is a main goal of scaffolding, this unintended result may actually fit well with the idea of scaffolding. However, this is only the case when responsibility for the task is gradually transferred to the students and fading of help is a gradual process. A study design with more than two time points should be used to establish whether teachers transfer responsibility and fade their help gradually and how this is related to student outcome variables.

Second, when controlling for task effort, low contingent support only resulted in improved achievement when students worked independently for short periods of time whereas high contingent support only resulted in improved achievement when students worked independently for long periods of time. Different from what we expected, high contingent support was not more effective than low contingent support in all situations. Low contingent support was more effective than high contingent support when given frequently (i.e., with short independent working time). This might be explained by the fact that non-contingent support results in superficial processing and hampers constructing a coherent mental model (e.g., Wannarka and Ruhl 2008 ). Therefore, students do not have a deep understanding of the subject-matter and keep needing help. High contingent support was more effective than low contingent support when it was given less frequently (i.e., with long periods of independent working time). It might be the case that, as suggested by several authors, with high contingent support students have sufficient resources to actively process the information provided and can make connections between the new information and existing knowledge in the long-term memory (e.g., Wittwer et al. 2010 ). This leads to a deeper understanding and a more coherent mental model which might be represented by the higher increase in achievement scores.

We would like to stress that this finding was only true when students’ task effort was controlled for. When task effort was not included as a covariate, the three-way-interaction (between occasion, contingency, and independent working time) was not significant. This means that students’ task effort partly determines whether contingent support is effective or not. This is supported by previous research that shows that task effort affects achievement (Fredricks et al. 2004 ). It might be interesting for future research to further investigate the mutual relationships between contingency, independent working time, task effort and achievement. Previous studies showed more straightforward positive effects of scaffolding on students’ achievement (Murphy and Messer 2000 ; Pino-Pasternak et al. 2010 ). Yet, these studies were conducted in lab-settings in which the independent working time and task effort are less crucial. Our findings provide less straightforward but more ecologically valid effects of scaffolding. Yet, more research in authentic settings is needed to further determine the effects of scaffolding in the classroom.

Third, in most cases, students’ task effort decreased from premeasurement to postmeasurement which is congruent with what is found in other studies (e.g., Gottfried et al. 2001 ; Stoel et al. 2003 ). Students’ task effort, however, increased when low contingent support was given frequently. In those situations, students’ task effort may have increased because of constant teacher reinforcements, which is known to foster students’ task effort (Axelrod and Zank 2012 ; Bicard et al. 2012 ). Yet, it is also important that students learn to put effort in working on tasks without frequent teacher reinforcements as teachers do not always have time to constantly reinforce students. Although high contingent support generally resulted in a decrease of task effort, high contingent support resulted in a smaller loss in task effort than low contingent support, when the independent working time was long. A possible explanation for the smaller decrease in task effort with infrequent high contingent support might be that when support is contingent, students know better what steps to take in subsequent independent working. Because they know better what to do, they may be less easily distracted than students who received low contingent support. Yet, when the aim is to increase student task effort, frequent low contingent support seemed most beneficial.