- Contact AAPS

- Get the Newsletter

How to Write a Really Great Presentation Abstract

Whether this is your first abstract submission or you just need a refresher on best practices when writing a conference abstract, these tips are for you..

An abstract for a presentation should include most the following sections. Sometimes they will only be a sentence each since abstracts are typically short (250 words):

- What (the focus): Clearly explain your idea or question your work addresses (i.e. how to recruit participants in a retirement community, a new perspective on the concept of “participant” in citizen science, a strategy for taking results to local government agencies).

- Why (the purpose): Explain why your focus is important (i.e. older people in retirement communities are often left out of citizen science; participants in citizen science are often marginalized as “just” data collectors; taking data to local governments is rarely successful in changing policy, etc.)

- How (the methods): Describe how you collected information/data to answer your question. Your methods might be quantitative (producing a number-based result, such as a count of participants before and after your intervention), or qualitative (producing or documenting information that is not metric-based such as surveys or interviews to document opinions, or motivations behind a person’s action) or both.

- Results: Share your results — the information you collected. What does the data say? (e.g. Retirement community members respond best to in-person workshops; participants described their participation in the following ways, 6 out of 10 attempts to influence a local government resulted in policy changes ).

- Conclusion : State your conclusion(s) by relating your data to your original question. Discuss the connections between your results and the problem (retirement communities are a wonderful resource for new participants; when we broaden the definition of “participant” the way participants describe their relationship to science changes; involvement of a credentialed scientist increases the likelihood of success of evidence being taken seriously by local governments.). If your project is still ‘in progress’ and you don’t yet have solid conclusions, use this space to discuss what you know at the moment (i.e. lessons learned so far, emerging trends, etc).

Here is a sample abstract submitted to a previous conference as an example:

Giving participants feedback about the data they help to collect can be a critical (and sometimes ignored) part of a healthy citizen science cycle. One study on participant motivations in citizen science projects noted “When scientists were not cognizant of providing periodic feedback to their volunteers, volunteers felt peripheral, became demotivated, and tended to forgo future work on those projects” (Rotman et al, 2012). In that same study, the authors indicated that scientists tended to overlook the importance of feedback to volunteers, missing their critical interest in the science and the value to participants when their contributions were recognized. Prioritizing feedback for volunteers adds value to a project, but can be daunting for project staff. This speed talk will cover 3 different kinds of visual feedback that can be utilized to keep participants in-the-loop. We’ll cover strengths and weaknesses of each visualization and point people to tools available on the Web to help create powerful visualizations. Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., et al. (2012). Dynamic changes in motivation in collaborative citizen-science projects. the ACM 2012 conference (pp. 217–226). New York, New York, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145238

📊 Data Ethics – Refers to trustworthy data practices for citizen science.

Get involved » Join the Data Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

📰 Publication Ethics – Refers to the best practice in the ethics of scholarly publishing.

Get involved » Join the Publication Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

⚖️ Social Justice Ethics – Refers to fair and just relations between the individual and society as measured by the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Social justice also encompasses inclusiveness and diversity.

Get involved » Join the Social Justice Topic Room on CSA Connect!

👤 Human Subject Ethics – Refers to rules of conduct in any research involving humans including biomedical research, social studies. Note that this goes beyond human subject ethics regulations as much of what goes on isn’t covered.

Get involved » Join the Human Subject Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🍃 Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics – Refers to the improvement of the dynamics between humans and the myriad of species that combine to create the biosphere, which will ultimately benefit both humans and non-humans alike [UNESCO 2011 white paper on Ethics and Biodiversity ]. This is a kind of ethics that is advancing rapidly in light of the current global crisis as many stakeholders know how critical biodiversity is to the human species (e.g., public health, women’s rights, social and environmental justice).

⚠ UNESCO also affirms that respect for biological diversity implies respect for societal and cultural diversity, as both elements are intimately interconnected and fundamental to global well-being and peace. ( Source ).

Get involved » Join the Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🤝 Community Partnership Ethics – Refers to rules of engagement and respect of community members directly or directly involved or affected by any research study/project.

Get involved » Join the Community Partnership Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

Tips for Writing an Excellent Conference Abstract

- Orientation

Add to Collection

Added to Collection

Have you ever attended a nursing conference and thought to yourself that someday you would love to present a session at this conference? Perhaps you submitted an abstract that didn’t get accepted. Have you read a call for abstracts and wished you knew how to write an excellent abstract? Maybe you are ready to take your professional growth to the next level by presenting at a national conference. Following are some tips to help you write an excellent conference abstract.

The road to an outstanding abstract begins with carefully reviewing the submission guidelines for the conference.

Before You Begin

- Read the directions carefully and often.

- Understand the format, length and content expected.

- Seek a mentor who has experience writing abstracts.

- Allow yourself enough time to prepare a first-rate submission; waiting until the last minute rarely results in quality content.

- Make sure there is evidence to support your topic, and provide current references.

Selecting a Topic

Let’s start at the beginning of your submission with the topic of your abstract. Consider the audience who attends the conference, and think of clinical or professional practice topics that would be meaningful and valuable to them. Timely and relevant topics with fresh ideas and takeaways are a great way to start, and they include:

- New research or clinical guidelines

- Topics that highlight your area of expertise

- Topics that are relevant to conference attendees

- Subjects that apply to current practice challenges or workplace concerns

- Narrowing your topic to focus on key information that will fit in the time allotted

Abstract Titles

The title is the first thing abstract scorers and conference attendees will see, so it is worth spending some time trying a few variations to see what conveys the main point of your abstract and entices the audience to read further:

- Keep the title clear and concise; be certain it accurately reflects your presentation.

- Catchy titles grab the reader’s attention, yet describe the subject well.

- A title with 12 or fewer words is optimal.

Abstract Content

Plan your abstract thoroughly before writing it. A high-quality abstract addresses the problem or question, the evidence and the solutions. It is important to give an overview of what you intend to include in the presentation. Abstracts should be concise but also informative. Sentences should be short to convey the needed information and free of words or phrases that do not add value. Keep your audience in mind as you prepare your abstract. How much background information you provide on a topic will depend on the conference. It is a good idea to explain how you plan to engage the audience with your teaching methods, such as case studies, polling or audience participation.

- After the title, the first sentence should be a hook that grabs the reader’s attention and entices them to continue reading.

- The second sentence should be a focused problem statement supported by evidence.

- The next few sentences provide the solution to the problem.

- The conclusion should reiterate the purpose of your presentation in one or two sentences.

Learning Objectives

If the conference abstract requires learning objectives, start each one with an action verb. Action verbs are words such as apply, demonstrate, explain, identify, outline and analyze. Refrain from using nonaction verbs and phrases such as understand, recognize, be able to, and become familiar with. Learning objectives must be congruent with the purpose, session description/summary and abstract text. For a list of action verbs, refer to a Bloom’s Taxonomy chart .

Editing Your Abstract

Editing is an important part of the abstract submission process. The editing phase will help you see the abstract as a whole and remove unnecessary words or phrases that do not provide value:

- The final draft should be clear and easy to read and understand.

- Your language should be professional and adhere to abstract guidelines.

- Writing in the present tense is preferred.

- If there is more than one author, each author should review and edit the draft.

- Ask a colleague who is a good editor to critique your work.

- Reread your abstract and compare it with the abstract guidelines.

- Great content that is written poorly will not be accepted.

- Prevent typographical errors by writing your submission as a Word document first, and copy and paste it into the submission platform after you check spelling and grammar.

- Follow word and character count instructions, abstract style and formatting guidelines.

- Do not try to bend the rules to fit your needs; authors who do not follow the guidelines are more likely to have their submission rejected.

- After you finish writing your abstract, put it aside and return later with a fresh mind before submitting it.

Grammar Tips

- Avoid ampersands (&) and abbreviations such as, etc.

- Parenthetical remarks (however relevant they may seem) are rarely necessary.

- It is usually incorrect to split an infinitive. An infinitive consists of the word “to” and the simple form of a verb (e.g., to go, to read).

- Examples: “To suddenly go” and “to quickly read” are examples of split infinitives, because the adverbs (suddenly and quickly) split (break up) the infinitives to go and to read.

- Contractions are not used in scholarly writing. Using contractions in academic writing is usually not encouraged, because it can make your writing sound informal.

- I’m = I am

- They’re = They are

- I’d = I had

- She’s = She is

- How’s = How is

- Avoid quotations.

- Do not be redundant or use more words than necessary.

- Use an active voice.

National Teaching Institute (NTI) Submissions

We invite you to participate in AACN’s mission to advance, promote and distribute information through education, research and science. The API (Advanced Practice Institute) and NTI volunteer committees review and score every abstract submitted for NTI. Abstracts are reviewed for relevance of content, quality of writing and expression of ideas. At NTI there are four session times to choose from. Your abstract should demonstrate that you have enough content to cover the selected time frame.

Session Types for NTI

- Mastery: 2.5 hours of content

- Concurrent: 60- or 75-minute sessions

- Preconference half-day: 3 hours of content

- Preconference full-day: 6 hours of content

Links for NTI Submissions

- Submit an abstract for NTI

- Read the Live Abstract Guidelines before submitting your abstract

Putting time and effort into writing an excellent abstract is the gateway to a podium presentation. It’s time to kickstart your professional growth and confidently submit a conference abstract.

For what conference will you submit an abstract?

This is an excellent blog with very sound advice. It has great content for nurses who are wanting to submit an abstract but feel they do not know whe ... re to start and so they never take the opportunity to do it. Read More

Are you sure you want to delete this Comment?

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

January 27th, 2015

How to write a killer conference abstract: the first step towards an engaging presentation..

34 comments | 135 shares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Helen Kara responds to our previously published guide to writing abstracts and elaborates specifically on the differences for conference abstracts. She offers tips for writing an enticing abstract for conference organisers and an engaging conference presentation. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

The Impact blog has an ‘essential ‘how-to’ guide to writing good abstracts’ . While this post makes some excellent points, its title and first sentence don’t differentiate between article and conference abstracts. The standfirst talks about article abstracts, but then the first sentence is, ‘Abstracts tend to be rather casually written, perhaps at the beginning of writing when authors don’t yet really know what they want to say, or perhaps as a rushed afterthought just before submission to a journal or a conference.’ This, coming so soon after the title, gives the impression that the post is about both article and conference abstracts.

I think there are some fundamental differences between the two. For example:

- Article abstracts are presented to journal editors along with the article concerned. Conference abstracts are presented alone to conference organisers. This means that journal editors or peer reviewers can say e.g. ‘great article but the abstract needs work’, while a poor abstract submitted to a conference organiser is very unlikely to be accepted.

- Articles are typically 4,000-8,000 words long. Conference presentation slots usually allow 20 minutes so, given that – for good listening comprehension – presenters should speak at around 125 words per minute, a conference presentation should be around 2,500 words long.

- Articles are written to be read from the page, while conference presentations are presented in person. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar, and there is nothing so tedious for a conference audience than the old-skool approach of reading your written presentation from the page. Fewer people do this now – but still, too many. It’s unethical to bore people! You need to engage your audience, and conference organisers will like to know how you intend to hold their interest.

Image credit: allanfernancato ( Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain )

The competition for getting a conference abstract accepted is rarely as fierce as the competition for getting an article accepted. Some conferences don’t even receive as many abstracts as they have presentation slots. But even then, they’re more likely to re-arrange their programme than to accept a poor quality abstract. And you can’t take it for granted that your abstract won’t face much competition. I’ve recently read over 90 abstracts submitted for the Creative Research Methods conference in May – for 24 presentation slots. As a result, I have four useful tips to share with you about how to write a killer conference abstract.

First , your conference abstract is a sales tool: you are selling your ideas, first to the conference organisers, and then to the conference delegates. You need to make your abstract as fascinating and enticing as possible. And that means making it different. So take a little time to think through some key questions:

- What kinds of presentations is this conference most likely to attract? How can you make yours different?

- What are the fashionable areas in your field right now? Are you working in one of these areas? If so, how can you make your presentation different from others doing the same? If not, how can you make your presentation appealing?

There may be clues in the call for papers, so study this carefully. For example, we knew that the Creative Research Methods conference , like all general methods conferences, was likely to receive a majority of abstracts covering data collection methods. So we stated up front, in the call for papers, that we knew this was likely, and encouraged potential presenters to offer creative methods of planning research, reviewing literature, analysing data, writing research, and so on. Even so, around three-quarters of the abstracts we received focused on data collection. This meant that each of those abstracts was less likely to be accepted than an abstract focusing on a different aspect of the research process, because we wanted to offer delegates a good balance of presentations.

Currently fashionable areas in the field of research methods include research using social media and autoethnography/ embodiment. We received quite a few abstracts addressing these, but again, in the interests of balance, were only likely to accept one (at most) in each area. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Second , write your abstract well. Unless your abstract is for a highly academic and theoretical conference, wear your learning lightly. Engaging concepts in plain English, with a sprinkling of references for context, is much more appealing to conference organisers wading through sheaves of abstracts than complicated sentences with lots of long words, definitions of terms, and several dozen references. Conference organisers are not looking for evidence that you can do really clever writing (save that for your article abstracts), they are looking for evidence that you can give an entertaining presentation.

Third , conference abstracts written in the future tense are off-putting for conference organisers, because they don’t make it clear that the potential presenter knows what they’ll be talking about. I was surprised by how many potential presenters did this. If your presentation will include information about work you’ll be doing in between the call for papers and the conference itself (which is entirely reasonable as this can be a period of six months or more), then make that clear. So, for example, don’t say, ‘This presentation will cover the problems I encounter when I analyse data with homeless young people, and how I solve those problems’, say, ‘I will be analysing data with homeless young people over the next three months, and in the following three months I will prepare a presentation about the problems we encountered while doing this and how we tackled those problems’.

Fourth , of course you need to tell conference organisers about your research: its context, method, and findings. It will also help enormously if you can take a sentence or three to explain what you intend to include in the presentation itself. So, perhaps something like, ‘I will briefly outline the process of participatory data analysis we developed, supported by slides. I will then show a two-minute video which will illustrate both the process in action and some of the problems encountered. After that, again using slides, I will outline each of the problems and how we tackled them in practice.’ This will give conference organisers some confidence that you can actually put together and deliver an engaging presentation.

So, to summarise, to maximise your chances of success when submitting conference abstracts:

- Make your abstract fascinating, enticing, and different.

- Write your abstract well, using plain English wherever possible.

- Don’t write in the future tense if you can help it – and, if you must, specify clearly what you will do and when.

- Explain your research, and also give an explanation of what you intend to include in the presentation.

While that won’t guarantee success, it will massively increase your chances. Best of luck!

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent social researcher in social care and health since 1999, and is an Associate Research Fellow at the Third Sector Research Centre , University of Birmingham. She is on the Board of the UK’s Social Research Association , with lead responsibility for research ethics. She also teaches research methods to practitioners and students, and writes on research methods. Helen is the author of Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners (2012) and Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences (April 2015) , both published by Policy Press . She did her first degree in Social Psychology at the LSE.

About the author

Dr Helen Kara FAcSS has been an independent researcher since 1999 and an independent scholar since 2011. She writes about research methods and research ethics, and teaches doctoral students and staff at higher education institutions worldwide. Her books include Creative Research Methods: A Practical Guide and Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives for Policy Press, and Qualitative Research for Quantitative Researchers for SAGE. She is an Affiliate at Swansea University and a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University.

34 Comments

Personally, I’d rather not see reading a presentation written off so easily, for three off the cuff reasons:

1) Reading can be done really well, especially if the paper was written to be read.

2) It seems to be well suited to certain kinds of qualitative studies, particularly those that are narrative driven.

3) It seems to require a different kind of focus or concentration — one that requires more intensive listening (as opposed to following an outline driven presentation that’s supplemented with visuals, i.e., slides).

Admittedly, I’ve read some papers before, and writing them to be read can be a rewarding process, too. I had to pay attention to details differently: structure, tone, story, etc. It can be an insightful process, especially for works in progress.

Sean, thanks for your comment, which I think is a really useful addition to the discussion. I’ve sat through so many turgid not-written-to-be-read presentations that it never occurred to me they could be done well until I heard your thoughts. What you say makes a great deal of sense to me, particularly with presentations that are consciously ‘written to be read’ out loud. I think where they can get tedious is where a paper written for the page is read out loud instead, because for me that really doesn’t work. But I love to listen to stories, and I think of some of the quality storytelling that is broadcast on radio, and of audiobooks that work well (again, in my experience, they don’t all), and I do entirely see your point.

Helen, I appreciate your encouraging me remark on such a minor part of your post(!), which I enjoyed reading and will share. And thank you for the reply and the exchange on Twitter.

Very much enjoyed your post Helen. And your subsequent comments Sean. On the subject of the reading of a presentation. I agree that some people can write a paper specifically to be read and this can be done well. But I would think that this is a dying art. Perhaps in the humanities it might survive longer. Reading through the rest of your post I love the advice. I’m presenting at my first LIS conference next month and had I read your post first I probably would have written it differently. Advice for the future for me.

Martin – and Sean – thank you so much for your kind comments. Maybe there are steps we can take to keep the art alive; advocates for it, such as Sean, will no doubt help. And, Martin, if you’re presenting next month, you must have done perfectly well all by yourself! Congratulations on the acceptance, and best of luck for the presentation.

Great article! Obvious at it may seem, a point zero may be added before the other four: which _are_ your ideas?

A scientific writing coach told me she often runs a little exercise with her students. She tells them to put away their (journal) abstract and then asks them to summarize the bottom line in three statements. After some thinking, the students come up with an answer. Then the coach tells the students to reach for the abstract, read it and look for the bottom line they just summarised. Very often, they find that their own main observations and/or conclusions are not clearly expressed in the abstract.

PS I love the line “It’s unethical to bore people!” 🙂

Thanks for your comment, Olle – that’s a great point. I think something happens to us when we’re writing, in which we become so clear about what we want to say that we think we’ve said it even when we haven’t. Your friend’s exercise sounds like a great trick for finding out when we’ve done that. And thanks for the compliments, too!

- Pingback: How to write a conference abstract | Blog @HEC Paris Library

- Pingback: Writer’s Paralysis | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Weekend reads: - Retraction Watch at Retraction Watch

- Pingback: The Weekly Roundup | The Graduate School

- Pingback: My Top 10 Abstract Writing tips | Jon Rainford's Blog

- Pingback: Review of the Year 2015 | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – 2015 Year-In-Review: LSE Impact Blog’s Most Popular Posts

Thank you very much for the tips, they are really helpful. I have actually been accepted to present a PuchaKucha presentation in an educational interdisciplinary conference at my university. my presentation would be about the challenges faced by women in my country. So, it would be just a review of the literature. from what I’ve been reading, conferences are about new research and your new ideas… Is what I’m doing wrong??? that’s my first conference I’ll be speaking in and I’m afraid to ruin it!!! I will be really grateful about any advice ^_^

First of all: you’re not going to ruin the conference, even if you think you made a bad presentation. You should always remember that people are not very concerned about you–they are mostly concerned about themselves. Take comfort in that thought!

Here are some notes: • If it is a Pecha Kucha night, you stand in front of a mixed audience. Remember that scientists understand layman’s stuff, but laymen don’t understand scientists stuff. • Pecha Kucha is also very VISUAL! Remember that you can’t control the flow of slides – they change every 20 seconds. • Make your main messages clear. You can use either one of these templates.

A. Which are the THREE most important observations, conclusions, implications or messages from your study?

B. Inform them! (LOGOS) Engage them! (PATHOS) Make an impression! (ETHOS)

C. What do you do as a scientist/is a study about? What problem(s) do you address? How is your research different? Why should I care?

Good luck and remember to focus on (1) the audience, (2) your mission, (3) your stuff and (4) yourself, in that order.

- Pingback: How to choose a conference then write an abstract that gets you noticed | The Research Companion

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Impact Community Insights: Five things we learned from our Reader Survey and Google Analytics.

- Pingback: Giving Us The Space To Think Things Through… | Research Into Practice Group

- Pingback: The Scholar-Practitioner Paradox for Academic Writing [@BreakDrink Episode No. 8] – techKNOWtools

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if perhaps everybody else encountering problems with your site. It appears as if some of the text in your content are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them as well? This could be a issue with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Thank you

- Pingback: Exhibition, abstracts and a letter from Prince Harry – EAHIL 2018

- Pingback: How to write a great abstract | DEWNR-NRM-Science-Conference

- Pingback: Abstracting and postering for conferences – ECRAG

Thank you Dr Kara for the great guide on creating killer abstracts for conferences. I am preparing to write an abstract for my first conference presentation and this has been educative and insightful. ‘ I choose to be ethical and not bore my audience’.

Thank you Judy for your kind comment. I wish you luck with your abstract and your presentation. Helen

- Pingback: Tips to Write a Strong Abstract for a Conference Paper – Research Synergy Institute

Dear Dr. Helen Kara, Can there be an abstract for a topic presentation? I need to present a topic in a conference.I searched in the net and couldnt find anything like an abstract for a topic presentation but only found abstract for article presentation. Urgent.Help!

Dear Rekha Sthapit, I think it would be the same – but if in doubt, you could ask the conference organisers to clarify what they mean by ‘topic presentation’. Good luck!

- Pingback: 2020: The Top Posts of the Decade | Impact of Social Sciences

- Pingback: Capturing the abstract: what ARE conference abstracts and what are they FOR? (James Burford & Emily F. Henderson) – Conference Inference

- Pingback: LSEUPR 2022 Conference | LSE Undergraduate Political Review

- Pingback: New Occupational Therapy Research Conference: Integrating research into your role – Glasgow Caledonian University Occupational Therapy Blog

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

‘It could be effective…’: Uncertainty and over-promotion in the abstracts of COVID-19 preprints

September 30th, 2021.

How to design an award-winning conference poster

May 11th, 2018.

Are scientific findings exaggerated? Study finds steady increase of superlatives in PubMed abstracts.

January 26th, 2016.

An antidote to futility: Why academics (and students) should take blogging / social media seriously

October 26th, 2015.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

Writing an abstract - a six point checklist (with samples)

Posted in: abstract , dissertations

The abstract is a vital part of any research paper. It is the shop front for your work, and the first stop for your reader. It should provide a clear and succinct summary of your study, and encourage your readers to read more. An effective abstract, therefore should answer the following questions:

- Why did you do this study or project?

- What did you do and how?

- What did you find?

- What do your findings mean?

So here's our run down of the key elements of a well-written abstract.

- Size - A succinct and well written abstract should be between approximately 100- 250 words.

- Background - An effective abstract usually includes some scene-setting information which might include what is already known about the subject, related to the paper in question (a few short sentences).

- Purpose - The abstract should also set out the purpose of your research, in other words, what is not known about the subject and hence what the study intended to examine (or what the paper seeks to present).

- Methods - The methods section should contain enough information to enable the reader to understand what was done, and how. It should include brief details of the research design, sample size, duration of study, and so on.

- Results - The results section is the most important part of the abstract. This is because readers who skim an abstract do so to learn about the findings of the study. The results section should therefore contain as much detail about the findings as the journal word count permits.

- Conclusion - This section should contain the most important take-home message of the study, expressed in a few precisely worded sentences. Usually, the finding highlighted here relates to the primary outcomes of the study. However, other important or unexpected findings should also be mentioned. It is also customary, but not essential, to express an opinion about the theoretical or practical implications of the findings, or the importance of their findings for the field. Thus, the conclusions may contain three elements:

- The primary take-home message.

- Any additional findings of importance.

- Implications for future studies.

Example Abstract 2: Engineering Development and validation of a three-dimensional finite element model of the pelvic bone.

Abstract from: Dalstra, M., Huiskes, R. and Van Erning, L., 1995. Development and validation of a three-dimensional finite element model of the pelvic bone. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 117(3), pp.272-278.

And finally... A word on abstract types and styles

Abstract types can differ according to subject discipline. You need to determine therefore which type of abstract you should include with your paper. Here are two of the most common types with examples.

Informative Abstract

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgements about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarised. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less.

Adapted from Andrade C. How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011 Apr;53(2):172-5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82558. PMID: 21772657; PMCID: PMC3136027 .

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

Navigating the dissertation process: my tips for final years

Imagine for a moment... After months of hard work and research on a topic you're passionate about, the time has finally come to click the 'Submit' button on your dissertation. You've just completed your longest project to date as part...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

My takeaways on how to write a scientific report

If you’re in your dissertation writing stage or your course includes writing a lot of scientific reports, but you don’t quite know where and how to start, the Skills Centre can help you get started. I recently attended their ‘How...

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

You can have a thorough understanding of abstracts using SciSpace ChatPDF which makes your abstract analysis part easier.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Science Writing

How to Write an Abstract

Last Updated: May 6, 2021 Approved

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 60 testimonials and 86% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 4,912,634 times.

If you need to write an abstract for an academic or scientific paper, don't panic! Your abstract is simply a short, stand-alone summary of the work or paper that others can use as an overview. [1] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source An abstract describes what you do in your essay, whether it’s a scientific experiment or a literary analysis paper. It should help your reader understand the paper and help people searching for this paper decide whether it suits their purposes prior to reading. To write an abstract, finish your paper first, then type a summary that identifies the purpose, problem, methods, results, and conclusion of your work. After you get the details down, all that's left is to format it correctly. Since an abstract is only a summary of the work you've already done, it's easy to accomplish!

Getting Your Abstract Started

- A thesis and an abstract are entirely different things. The thesis of a paper introduces the main idea or question, while the abstract works to review the entirety of the paper, including the methods and results.

- Even if you think that you know what your paper is going to be about, always save the abstract for last. You will be able to give a much more accurate summary if you do just that - summarize what you've already written.

- Is there a maximum or minimum length?

- Are there style requirements?

- Are you writing for an instructor or a publication?

- Will other academics in your field read this abstract?

- Should it be accessible to a lay reader or somebody from another field?

- Descriptive abstracts explain the purpose, goal, and methods of your research but leave out the results section. These are typically only 100-200 words.

- Informative abstracts are like a condensed version of your paper, giving an overview of everything in your research including the results. These are much longer than descriptive abstracts, and can be anywhere from a single paragraph to a whole page long. [4] X Research source

- The basic information included in both styles of abstract is the same, with the main difference being that the results are only included in an informative abstract, and an informative abstract is much longer than a descriptive one.

- A critical abstract is not often used, but it may be required in some courses. A critical abstract accomplishes the same goals as the other types of abstract, but will also relate the study or work being discussed to the writer’s own research. It may critique the research design or methods. [5] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

Writing Your Abstract

- Why did you decide to do this study or project?

- How did you conduct your research?

- What did you find?

- Why is this research and your findings important?

- Why should someone read your entire essay?

- What problem is your research trying to better understand or solve?

- What is the scope of your study - a general problem, or something specific?

- What is your main claim or argument?

- Discuss your own research including the variables and your approach.

- Describe the evidence you have to support your claim

- Give an overview of your most important sources.

- What answer did you reach from your research or study?

- Was your hypothesis or argument supported?

- What are the general findings?

- What are the implications of your work?

- Are your results general or very specific?

Formatting Your Abstract

- Many journals have specific style guides for abstracts. If you’ve been given a set of rules or guidelines, follow them to the letter. [8] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- Avoid using direct acronyms or abbreviations in the abstract, as these will need to be explained in order to make sense to the reader. That uses up precious writing room, and should generally be avoided.

- If your topic is about something well-known enough, you can reference the names of people or places that your paper focuses on.

- Don’t include tables, figures, sources, or long quotations in your abstract. These take up too much room and usually aren’t what your readers want from an abstract anyway. [9] X Research source

- For example, if you’re writing a paper on the cultural differences in perceptions of schizophrenia, be sure to use words like “schizophrenia,” “cross-cultural,” “culture-bound,” “mental illness,” and “societal acceptance.” These might be search terms people use when looking for a paper on your subject.

- Make sure to avoid jargon. This specialized vocabulary may not be understood by general readers in your area and can cause confusion. [12] X Research source

- Consulting with your professor, a colleague in your field, or a tutor or writing center consultant can be very helpful. If you have these resources available to you, use them!

- Asking for assistance can also let you know about any conventions in your field. For example, it is very common to use the passive voice (“experiments were performed”) in the sciences. However, in the humanities active voice is usually preferred.

Sample Abstracts and Outline

Community Q&A

- Abstracts are typically a paragraph or two and should be no more than 10% of the length of the full essay. Look at other abstracts in similar publications for an idea of how yours should go. [13] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Consider carefully how technical the paper or the abstract should be. It is often reasonable to assume that your readers have some understanding of your field and the specific language it entails, but anything you can do to make the abstract more easily readable is a good thing. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/abstracts/

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/presentations_abstracts_examples.html

- ↑ http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/656/1/

- ↑ https://www.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/656/1/

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136027/

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/presentations_abstracts.html

About This Article

To write an abstract, start with a short paragraph that explains the purpose of your paper and what it's about. Then, write a paragraph explaining any arguments or claims you make in your paper. Follow that with a third paragraph that details the research methods you used and any evidence you found for your claims. Finally, conclude your abstract with a brief section that tells readers why your findings are important. To learn how to properly format your abstract, read the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

May 21, 2017

Did this article help you?

Rohit Payal

Aug 5, 2018

Nila Anggreni Roni

Feb 6, 2017

Aug 27, 2019

Mike Bossert

Dec 27, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

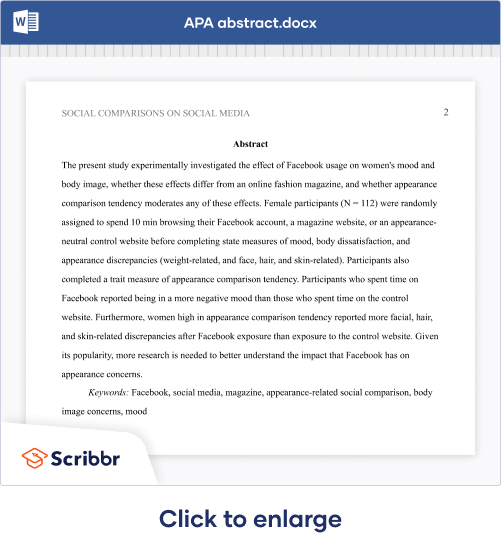

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .