Center for Teaching

Grading student work.

Print Version

What Purposes Do Grades Serve?

Developing grading criteria, making grading more efficient, providing meaningful feedback to students.

- Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-Sectioned Courses

Minimizing Student Complaints about Grading

Barbara Walvoord and Virginia Anderson identify the multiple roles that grades serve:

- as an evaluation of student work;

- as a means of communicating to students, parents, graduate schools, professional schools, and future employers about a student’s performance in college and potential for further success;

- as a source of motivation to students for continued learning and improvement;

- as a means of organizing a lesson, a unit, or a semester in that grades mark transitions in a course and bring closure to it.

Additionally, grading provides students with feedback on their own learning , clarifying for them what they understand, what they don’t understand, and where they can improve. Grading also provides feedback to instructors on their students’ learning , information that can inform future teaching decisions.

Why is grading often a challenge? Because grades are used as evaluations of student work, it’s important that grades accurately reflect the quality of student work and that student work is graded fairly. Grading with accuracy and fairness can take a lot of time, which is often in short supply for college instructors. Students who aren’t satisfied with their grades can sometimes protest their grades in ways that cause headaches for instructors. Also, some instructors find that their students’ focus or even their own focus on assigning numbers to student work gets in the way of promoting actual learning.

Given all that grades do and represent, it’s no surprise that they are a source of anxiety for students and that grading is often a stressful process for instructors.

Incorporating the strategies below will not eliminate the stress of grading for instructors, but it will decrease that stress and make the process of grading seem less arbitrary — to instructors and students alike.

Source: Walvoord, B. & V. Anderson (1998). Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass.

- Consider the different kinds of work you’ll ask students to do for your course. This work might include: quizzes, examinations, lab reports, essays, class participation, and oral presentations.

- For the work that’s most significant to you and/or will carry the most weight, identify what’s most important to you. Is it clarity? Creativity? Rigor? Thoroughness? Precision? Demonstration of knowledge? Critical inquiry?

- Transform the characteristics you’ve identified into grading criteria for the work most significant to you, distinguishing excellent work (A-level) from very good (B-level), fair to good (C-level), poor (D-level), and unacceptable work.

Developing criteria may seem like a lot of work, but having clear criteria can

- save time in the grading process

- make that process more consistent and fair

- communicate your expectations to students

- help you to decide what and how to teach

- help students understand how their work is graded

Sample criteria are available via the following link.

- Analytic Rubrics from the CFT’s September 2010 Virtual Brownbag

- Create assignments that have clear goals and criteria for assessment. The better students understand what you’re asking them to do the more likely they’ll do it!

- letter grades with pluses and minuses (for papers, essays, essay exams, etc.)

- 100-point numerical scale (for exams, certain types of projects, etc.)

- check +, check, check- (for quizzes, homework, response papers, quick reports or presentations, etc.)

- pass-fail or credit-no-credit (for preparatory work)

- Limit your comments or notations to those your students can use for further learning or improvement.

- Spend more time on guiding students in the process of doing work than on grading it.

- For each significant assignment, establish a grading schedule and stick to it.

Light Grading – Bear in mind that not every piece of student work may need your full attention. Sometimes it’s sufficient to grade student work on a simplified scale (minus / check / check-plus or even zero points / one point) to motivate them to engage in the work you want them to do. In particular, if you have students do some small assignment before class, you might not need to give them much feedback on that assignment if you’re going to discuss it in class.

Multiple-Choice Questions – These are easy to grade but can be challenging to write. Look for common student misconceptions and misunderstandings you can use to construct answer choices for your multiple-choice questions, perhaps by looking for patterns in student responses to past open-ended questions. And while multiple-choice questions are great for assessing recall of factual information, they can also work well to assess conceptual understanding and applications.

Test Corrections – Giving students points back for test corrections motivates them to learn from their mistakes, which can be critical in a course in which the material on one test is important for understanding material later in the term. Moreover, test corrections can actually save time grading, since grading the test the first time requires less feedback to students and grading the corrections often goes quickly because the student responses are mostly correct.

Spreadsheets – Many instructors use spreadsheets (e.g. Excel) to keep track of student grades. A spreadsheet program can automate most or all of the calculations you might need to perform to compute student grades. A grading spreadsheet can also reveal informative patterns in student grades. To learn a few tips and tricks for using Excel as a gradebook take a look at this sample Excel gradebook .

- Use your comments to teach rather than to justify your grade, focusing on what you’d most like students to address in future work.

- Link your comments and feedback to the goals for an assignment.

- Comment primarily on patterns — representative strengths and weaknesses.

- Avoid over-commenting or “picking apart” students’ work.

- In your final comments, ask questions that will guide further inquiry by students rather than provide answers for them.

Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-sectioned Courses (for course heads)

- Communicate your grading policies, standards, and criteria to teaching assistants, graders, and students in your course.

- Discuss your expectations about all facets of grading (criteria, timeliness, consistency, grade disputes, etc) with your teaching assistants and graders.

- Encourage teaching assistants and graders to share grading concerns and questions with you.

- have teaching assistants grade assignments for students not in their section or lab to curb favoritism (N.B. this strategy puts the emphasis on the evaluative, rather than the teaching, function of grading);

- have each section of an exam graded by only one teaching assistant or grader to ensure consistency across the board;

- have teaching assistants and graders grade student work at the same time in the same place so they can compare their grades on certain sections and arrive at consensus.

- Include your grading policies, procedures, and standards in your syllabus.

- Avoid modifying your policies, including those on late work, once you’ve communicated them to students.

- Distribute your grading criteria to students at the beginning of the term and remind them of the relevant criteria when assigning and returning work.

- Keep in-class discussion of grades to a minimum, focusing rather on course learning goals.

For a comprehensive look at grading, see the chapter “Grading Practices” from Barbara Gross Davis’s Tools for Teaching.

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Teaching Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Grading Student Work

Strategies, best practices and practical examples to make your grading process more efficient, effective and meaningful

Top Hat Staff

This ultimate guide to grading student work offers strategies, tips and examples to help you make the grading process more efficient and effective for you and your students. The right approach can save time for other teaching tasks, like lecture preparation and student mentoring.

Grading is one of the most painstaking responsibilities of postsecondary teaching. It’s also one of the most crucial elements of the educational process. Even with an efficient system, grading requires a great deal of time—and even the best-laid grading systems are not entirely immune to student complaints and appeals. This guide explores some of the common challenges in grading student work along with proven grading techniques and helpful tips to communicate expectations and set you and your students up for success, especially those who are fresh out of high school and adjusting to new expectations in college or university.

What is grading?

Grading is only one of several indicators of a student’s comprehension and mastery, but understanding what grading entails is essential to succeeding as an educator. It allows instructors to provide standardized measures to evaluate varying levels of academic performance while providing students valuable feedback to help them gauge their own understanding of course material and skill development. Done well, effective grading techniques show learners where they performed well and in what areas they need improvement. Grading student work also gives instructors insights into how they can improve the student learning experience.

Grading challenges: Clarity, consistency and fairness

No matter how experienced the instructor is, grading student work can be tricky. No such grade exists that perfectly reflects a student’s overall comprehension or learning. In other words, some grades end up being inaccurate representations of actual comprehension and mastery. This is often the case when instructors use an inappropriate grading scale, such as a pass/fail structure for an exam, when a 100-point system gives a more accurate or nuanced picture.

Grading students’ work fairly but consistently presents other challenges. For example, grades for creative projects or essays might suffer from instructor bias, even with a consistent rubric in place. Instructors can employ every strategy they know to ensure fairness, accessibility, accuracy and consistency, and even so, some students will still complain about their grades. Handling grade point appeals can pull instructors away from other tasks that need their attention.

Many of these issues can be avoided by breaking things down into logical steps. First, get clear on the learning outcomes you seek to achieve, then ensure the coursework students will engage in is well suited to evaluating those outcomes and last, identify the criteria you will use to assess student performance.

What are some grading strategies for educators?

There are a number of grading techniques that can alleviate many problems associated with grading, including the perception of inconsistent, unfair or arbitrary practices. Grading can use up a large portion of educators’ time. However, the results may not improve even if the time you spend on it does. Grading, particularly in large class sizes, can leave instructors feeling burnt out. Those who are new to higher education can fall into a grading trap, where far too much of their allocated teaching time is spent on grading. As well, after the graded assignments have been handed back, there may be a rush of students wanting either to contest the grade, or understand why they got a particular grade, which takes up even more of the instructor’s time. With some dedicated preparation time, careful planning and thoughtful strategies, grading student work can be smooth and efficient. It can also provide effective learning opportunities for the students and good information for the instructor about the student learning (or lack of) taking place in the course. These grading strategies can help instructors improve their accuracy in capturing student performance .

Establishing clear grading criteria

Setting grading criteria helps reduce the time instructors spend on actual grading later on. Such standards add consistency and fairness to the grading process, making it easier for students to understand how grading works. Students also have a clearer understanding of what they need to do to reach certain grade levels.

Establishing clear grading criteria also helps instructors communicate their performance expectations to students. Furthermore, clear grading strategies give educators a clearer picture of content to focus on and how to assess subject mastery. This can help avoid so-called ‘busywork’ by ensuring each activity aligns clearly to the desired learning outcome.

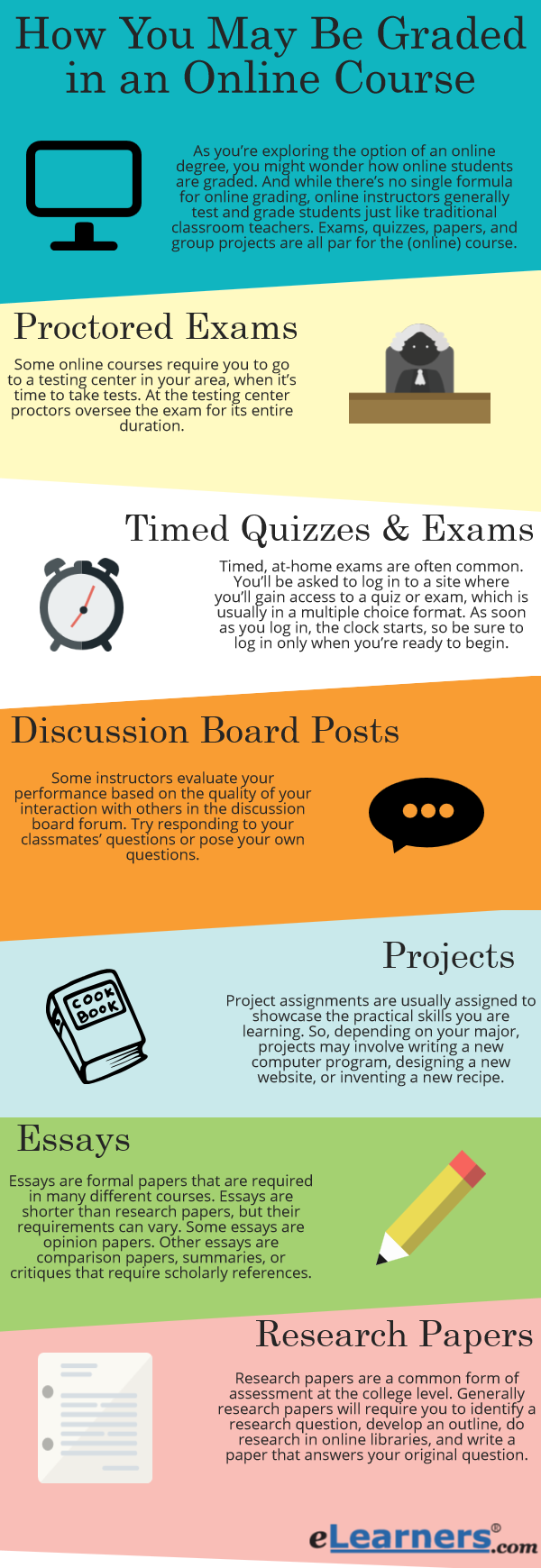

Step 1: Determine the learning outcomes and the outputs to measure performance. Does assessing comprehension require quizzes and/or exams, or will written papers better capture what the instructor wants to see from students’ performance? Perhaps lab reports or presentations are an ideal way of capturing specific learning objectives, such as behavioral mastery.

Step 2: Establish criteria to determine how you will evaluate assigned work. Is it precision in performing steps, accuracy in information recall, or thoroughness in expression? To what extent will creativity factor in the assessment?

Step 3: Determine the grade weight or value for each assignment. These weights represent the relative importance of each assignment toward the final grade and a student’s GPA. For example, how much will the final exam count relative to a research paper or essay? Once the weights are in place, it’s essential to stratify grades that distinguish performance levels. For example:

- A grade = excellent

- B grade = very good

- C grade = adequate

- D grade = poor but passing

- F grade = unacceptable

Making grading efficient

Grading efficiency depends a great deal on devoting appropriate amounts of time to certain grading tasks. For instance, some assignments deserve less attention than others. That’s why some outcomes, like attendance or participation work, can help save time by getting a simple pass/fail grade or acknowledgment of completion using a check/check-plus/check-minus scale.

However, other assignments like tests or papers need to show more in-depth comprehension of the course material. These items need more intricate scoring schemes and require more time to evaluate, especially if student responses warrant feedback.

When appropriate, multiple-choice questions can provide a quick grading technique. They also provide the added benefit of grading consistency among all students completing the questions. However, multiple-choice questions are more difficult to write than most people realize. These questions are most useful when information recall and conceptual understanding are the primary learning outcomes.

Instructors can maximize their time for more critical educational tasks by creating scheduled grading strategies and sticking to it. A spreadsheet is also essential for calculating many students’ grades quickly and exporting data to other platforms.

Making grading more meaningful in higher education

Grading student work is more than just routine, despite what some students believe. The better students understand what instructors expect them to take away from the course, the more meaningful the grading structure will be. Meaningful grading strategies reflect effective assignments, which have distinct goals and evaluation criteria. It also helps avoid letting the grading process take priority over teaching and mentoring.

Leaving thoughtful and thorough comments does more than rationalize a grade. Providing feedback is another form of teaching and helps students better understand the nuances behind the grade. Suppose a student earns a ‘C’ on a paper. If the introduction was outstanding, but the body needed improvement, comments explaining this distinction will give a clearer picture of what the ‘C’ grade represents as opposed to ‘A-level’ work.

Instructors should limit comments to elements of their work that students can actually improve or build upon. Above all, comments should pertain to the original goal of the assignment. Excessive comments that knit-pick a student’s work are often discouraging and overwhelming, leaving the student less able or willing to improve their effort on future projects. Instead, instructors should provide comments that point to patterns of strengths and areas needing improvement. It’s also helpful to leave a summary comment at the end of the assignment or paper.

Maintaining a complaint-free grading system

In many instances, an appropriate response to a grade complaint might simply be, “It’s in the syllabus.” Nevertheless, one of the best strategies to curtail grade complaints is to limit or prohibit discussions of grades during class time. Inform students that they can discuss grades outside of class or during office hours.

Instructors can do many things before the semester or term begins to reduce grade complaints. This includes detailed explanations in the grading system’s syllabus, the criteria for earning a particular letter grade, policies on late work, and other standards that inform grading. It also doesn’t hurt to remind students of each assignment’s specific grading criteria before it comes due. Instructors should avoid changing their grading policies; doing so will likely lead to grade complaints.

Assigning student grades

Since not all assignments may count equally toward a final course grade, instructors should figure out which grading scales are appropriate for each assignment. They should also consider that various assignments assess student work differently; therefore, their grading structure should reflect those differences. For example, some exams might warrant a 100-point scale rather than a pass/fail grade. Requirements like attendance or class participation might be used to reward effort; therefore, merely completing that day’s requirement is sufficient.

Grading essays and open-ended writing

Some writing projects might seem like they require more subjective grading standards than multiple-choice tests. However, instructors can implement objective standards to maintain consistency while acknowledging students’ individual approaches to the project.

Instructors should create a rubric or chart against which they evaluate each assignment. A rubric contains specific grading criteria and the point value for each. For example, out of 100 points, a rubric specifies that a maximum of 10 points are given to the introduction. Furthermore, an instructor can include even more detailed elements that an introduction should include, such as a thesis statement, attention-getter, and preview of the paper’s main points.

Grading creative work

While exams, research papers, and math problems tend to have more finite grading criteria, creative works like short films, poetry, or sculptures can seem more difficult to grade. Instructors might apply technical evaluations that adhere to disciplinary standards. However, there is the challenge of grading how students apply their subject talent and judgment to a finished product.

For creative projects that are more visual, instructors might ask students to submit a written statement along with their assignment. This statement can provide a reflection or analysis of the finished product, or describe the theory or concept the student used. This supplement can add insight that informs the grade.

Grading for multi-section courses

Professors or course coordinators who oversee several sections of a course have the added responsibility of managing other instructors or graduate student teaching assistants (TAs) in addition to their own grading. Course directors need to communicate regularly and consistently with all teaching staff about the grading standards and criteria to ensure they are applied consistently across all sections.

If possible, the course director should address students from all sections in one gathering to explain the criteria, expectations, assignments, and other policies. TAs should continue to communicate grading-related information to the students in their classes. They also should maintain contact with each other and the course director to address inconsistencies, stay on top of any changes and bring attention to problems.

To maintain consistency and objectivity across all sections, the course director might consider assigning TAs to grade other sections besides their own. Another strategy that can save time and maintain consistency is to have each TA grade only one exam portion. It’s also vital to compare average grades and test scores across sections to see if certain groups of students are falling behind or if some classes need changes in their teaching strategies.

Types of grading

- Absolute grading : A grading system where instructors explain performance standards before the assignment is completed. grades are given based on predetermined cutoff levels. Here, each point value is assigned a letter grade. Most schools adopt this system, where it’s possible for all students to receive an A.

- Relative grading : An assessment system where higher education instructors determine student grades by comparing them against those of their peers.

- Weighted grades : A method ussed in higher education to determine how different assessments should count towards the final grade. An instructor may choose to make the results of an exam worth 50 percent of a student’s total class grade, while assignments account for 25 percent and participation marks are worth another 25 percent.

- Grading on a curve : This system adjusts student grades to ensure that a test or assignment has the proper distribution throughout the class (for example, only 20% of students receive As, 30% receive Bs, and so on), as well as a desired total average (for example, a C grade average for a given test). We’ve covered this type of grading in more detail in the blog post The Ultimate Guide to Grading on A Curve .

Ungrading is an education model that prioritizes giving feedback and encouraging learning through self-reflection rather than a letter grade. Some instructors argue that grades cannot objectively assess a student’s work. Even when calculated down to the hundredth of a percentage point, a “B+” on an English paper doesn’t paint a complete picture about what a student can do, what they understand or where they need help. Alfie Kohn, lecturer on human behavior, education, and parenting, says that the basis for grades is often subjective and uninformative. Even the final grade on a STEM assignment is more of a reflection of how the assignment was written, rather than the student’s mastery of the subject matter. So what are educators who have adopted ungrading actually doing? Here are some practices and strategies that decentralize the role of assessments in the higher ed classroom.

- Frequent feedback: Rather than a final paper or exam, encourage students to write letters to reflect on their progress and learning throughout the term. Students are encouraged to reflect on and learn from both their successes and their failures, both individually and with their peers. In this way, conversations and commentary become the primary form of feedback, rather than a letter grade.

- Opportunities for self-reflection: Open-ended questions help students to think critically about their learning experiences. Which course concepts have you mastered? What have you learned that you are most excited about? Simple questions like these help guide students towards a more insightful understanding of themselves and their progress in the course.

- Increasing transparency: Consider informal drop-in sessions or office hours to answer student questions about navigating a new style of teaching and learning. The ungrading process has to begin from a place of transparency and openness in order to build trust. Listening to and responding to student concerns is vital to getting students on board. But just as important is the quality of feedback provided, ensuring both instructors and students remain on the same page.

Grading on a curve

Instructors will grade on a curve to allow for a specific distribution of scores, often referred to as “normal distribution.” To ensure there is a specific percentage of students receiving As, Bs, Cs and so forth, the instructor can manually adjust grades.

When displayed visually, the distribution of grades ideally forms the shape of a bell. A small number of students will do poorly, another small group will excel and most will fall somewhere in the middle. Students whose grades settle in the middle will receive a C-average. Students with the highest and the lowest grades fall on either side.

Some instructors will only grade assignments and tests on a curve if it is clear that the entire class struggled with the exam. Others use the bell curve to grade for the duration of the term, combining every score and putting the whole class (or all of their classes, if they have more than one) on a curve once the raw scores are tallied.

How to make your grading techniques easier

Grading is a time-consuming exercise for most educators. Here are some tips to help you become more efficient and to lighten your load.

- Schedule time for grading: Pay attention to your rhythms and create a grading schedule that works for you. Break the work down into chunks and eliminate distractions so you can stay focused.

- Don’t assign ‘busy work’: Each student assignment should map clearly to an important learning outcome. Planning up front ensures each assignment is meaningful and will avoid adding too much to your plate.

- Use rubrics to your advantage: Clear grading criteria for student assignments will help reduce the cognitive load and second guessing that can happen when these tools aren’t in place. Having clear standards for different levels of performance will also help ensure fairness.

- Prioritize feedback: It’s not always necessary to provide feedback on every assignment. Also consider bucketing feedback into what was done well, areas for improvement and ways to improve. Clear, pointed feedback is less time-consuming to provide and often more helpful to students.

- Reward yourself: Grading is taxing work. Be realistic about how much you can do and in what time period. Stick to your plan and make sure to reward yourself with breaks, a walk outside or anything else that will help you refresh.

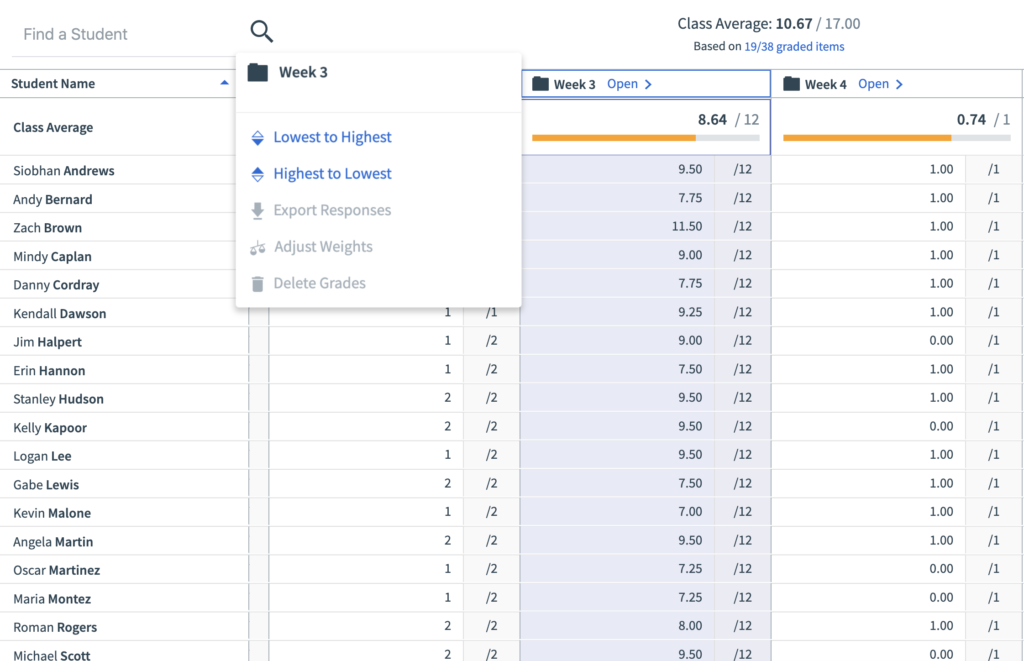

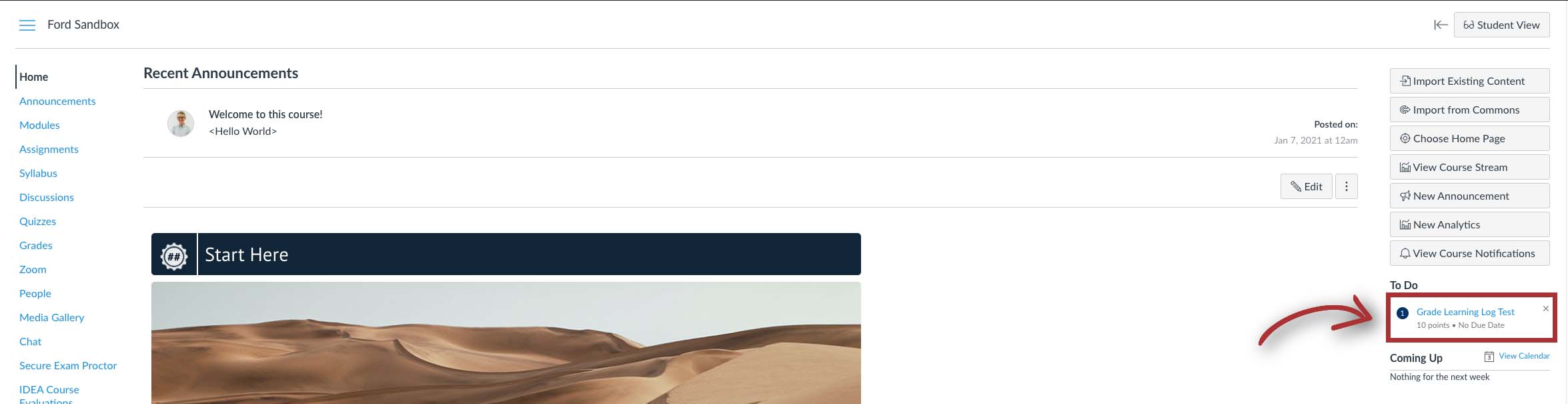

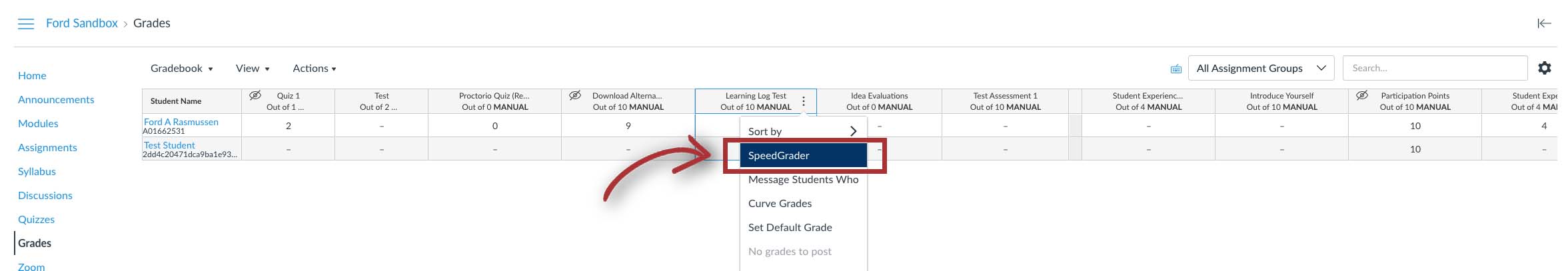

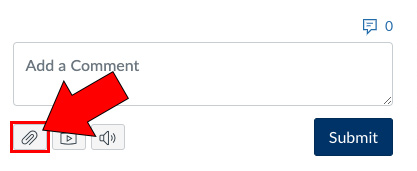

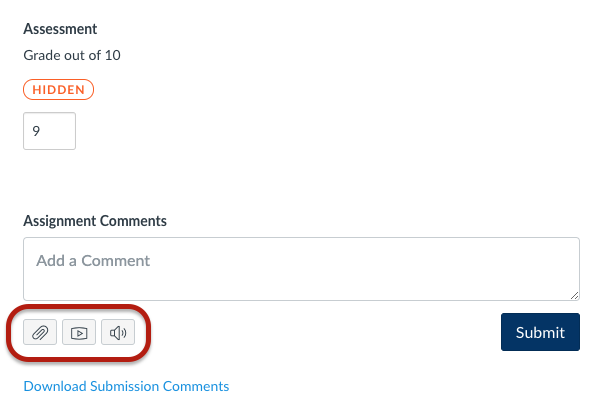

How Top Hat streamlines grading

There are many tools available to college educators to make grading student work more consistent and efficient. Top Hat’s all-in-one teaching platform allows you to automate a number of grading processes, including tests and quizzes using a variety of different question types. Attendance, participation, assignments and tests are all automatically captured in the Top Hat Gradebook , a sophisticated data management tool that maintains multiple student records.

In the Top Hat Gradebook, you can access individual and aggregate grades at a glance while taking advantage of many different reporting options. You can also sync grades and other reporting directly to your learning management system (LMS).

Grading is one of the most essential components of the teaching and learning experience. It requires a great deal of strategy and thought to be executed well. While it certainly isn’t without its fair share of challenges, clear expectations and transparent practice ensure that students feel included as part of the process and can benefit from the feedback they receive. This way, they are able to track their own progress towards learning goals and course objectives.

Click here to learn more about Gradebook, Top Hat’s all-in-one solution designed to help you monitor student progress with immediate, real-time feedback.

Recommended Readings

The Ultimate Guide to Metacognition for Post-Secondary Courses

25 Effective Instructional Strategies For Educators

Subscribe to the top hat blog.

Join more than 10,000 educators. Get articles with higher ed trends, teaching tips and expert advice delivered straight to your inbox.

- Teaching Tips

Dealing With Students Missing Exams and In-Class Graded Assignments

Teachers often become more aware of students’ out-of-class activities than they might wish. Announcements and memos from the dean of students inform about sporting teams and their games and tournaments, forensics, service learning conferences, community-based work, and the like. And teachers quickly become familiar with student lifestyles and illnesses ¾ mono, strep throat, hangovers, the opening of deer and fishing seasons, quilting bees, family vacations, and their family mortality statistics. The relationship between exams and mandatory in-class work and the death of students’ cousins and grandparents is so high it should be a concern of the National Center for Disease Control. Given all this, it is a certainty that students will miss exams and other required activities. What is a teacher to do?

If you want to hear colleagues express frustration, ask them about make-up exams and assignments. Despite knowing intellectually that such absences will occur, teachers hope and pray, even in public institutions, that all of their students will take exams as scheduled. Alas, such prayers are rarely answered, and teachers are faced with the practical issues of keeping track of students who miss exams and assignments, as well as managing make-ups.

All of our advice, except that related to ethics, should be read through the filter of the type of institution where you teach, and the types of courses you teach and how large they are. For example, at a small liberal arts school, where teaching is a faculty member’s primary responsibility, more time may be spent with students who miss exams or assignments, and more creative (time consuming) alternatives may be practical as compared with someone teaching classes of 300 or 500 or more in a Research I institution.

Ethics Teachers are not to cause students harm; we must treat them fairly and equitably, and they must be allowed to maintain their dignity (Keith-Spiegel, Whitley, Balogh, Perkins, & Wittig, 2002). Whatever your procedures are for students who miss exams and required in-class work, they must be equitable, providing students equal chances to earn a good grade by demonstrating equal knowledge. The hard part may be balancing academic rigor and accountability for what students are to learn with a fair and manageable process for those who miss required exams and assignments.

Make-up Exams These should not be more difficult than the original test but must be, as best as you can design, alternate forms of the same exam. Exam banks that accompany texts make designing such alternate forms of multiple-choice tests relatively easy, and colleagues teaching two or more sections of the same course in a semester, who give alternate forms of exams, are often a good source of advice on this matter. Be thoughtful about the following:

- An essay make-up exam may be unethical if regular exams are multiple choice or short answer (or vice versa), since students must study differently and they may be more difficult.

- An oral exam may “punish” students who do not think well on their feet, or are more socially anxious.

- Scheduling make-up exams at inconvenient or undesirable times may express your frustration, but you or someone else will have to be there at the “inconvenient” time also, and such arrangements raise issues of foul play.

- It may be inequitable to students who meet all course requirements to allow their peers to do extra credit or drop their lowest grade instead of making up a missed exam.

In-class Assignments The same considerations exist for students who miss in-class required presentations, or other graded work. If possible, students who were to present should be given opportunities to make up the assignment using the same grading criteria.

Planning Ahead

Spell-out Missed Exam Procedure in Course Policies No matter how well you teach or what inducements or penalties you impose, some students will miss exams and required class activities. Good educational practice argues that you plan for this reality as you design your course, not two days before (or after) your first exam. You want as few surprises as possible once the course begins.

Put your policies in your syllabus. Have a section in your syllabus on exams and other graded work. Specify your policies and procedures if students know in advance they will be absent, or how to notify you if, for whatever reason, they were absent, and any effect, if any, absences will have on their grade.

Keep your policy clear and simple. Before finalizing your syllabus, ask a few students to read your make-up policy to determine if it can be easily understood. If your explanation of what students are to do in the case of missing an exam, and how their grade is affected, is not easily understood, revise it. In developing your policy, do you want students to:

- Notify you if they know they will miss, preferably at least 24 hours in advance, and give you the reason? Talking with you before or after class offers the best opportunity to provide feedback if the reason is questionable, to work out alternatives, and so forth. E-mail also can be useful.

- Notify you as soon as possible after missing an exam or required assignment and give the reason? Again, in person or e-mail work best.

- Present a letter from an authority (e.g., physician) documenting the reason? Keep in mind any student can “forge” such documentation or manipulate it in other ways, e.g., “Fred came to see me complaining of a severe headache.”

- Have their grades lowered if their absence is not “acceptable” (e.g., overslept versus seriously ill)? How will you decide what is acceptable? Our experience suggests that “legitimate” reasons for absence include, but are not limited to: illness of the student or a close relative, accident, court appearance, military duty, broken auto, hazardous weather, and university activities (e.g., athletics, forensics).

Policies should reflect the nature of the exam or graded assignment. If you are teaching an introductory course and each module largely stands alone, it may be appropriate for students to make up a missed exam late in the semester. But if you want students to demonstrate knowledge or competency on an exam or assignment because future course material builds on that which comes earlier, you want to give the students much less time to make up the missed work.

Common policies. A common procedure is for the teacher, teaching assistant, or departmental secretary to distribute and proctor make-up exams during prearranged times (Perlman&McCann, in press). You might also consider allowing students to take make-up exams during exam periods in other courses you are teaching.

Make your policies easy to implement. To maintain your sanity and keep your stress level manageable, you must be able to easily implement your policies. For example, even if you, a secretary, or a graduate student distribute and proctor make-up exams, problems can arise. For example:

- The secretary is ill or on vacation, or you are ill or have a conference to attend. You never want to change the time make-ups are available to students once these are listed in the course syllabus. Have backups available who know where make-up exams are stored, can access them, and can administer and proctor them.

- Too many students for the make-up space. Investigate room sizes and number of rooms available. You may need more than one room if some students have readers because of learning disabilities.

- Students often forget there is a common make-up the last week of the semester. Remind them often and announce this policy on class days when students are taking an exam, as this may be the only time some students who have missed a previous exam come to class.

Encourage appropriate, responsible, mature behaviors. Take the high road and let students know how they “should” behave. For example, one colleague includes this statement in the syllabus:

I expect students to make every effort to take required exams and make course presentations as scheduled. If you know in advance you will miss such a requirement, please notify me. If you are ill or other circumstances cause you to miss a required graded activity, notify me as soon as possible.

One of our colleagues states in her syllabus for a psychology of aging class, “It is very bad form to invent illnesses suffered by grandparents!” By giving students exemplars on how to behave appropriately, you can then thank them for their courtesy and maturity if they follow through, positively reinforcing such behaviors.

God lives in the details. Always err on the side of being “concrete.” If a make-up exam is at the university testing center, tell students where the testing center is. If you or a secretary hold make-up exams in an office, you may want to draw a map on how to get there. It is not uncommon for students to fail to find the office at the time of the exam, and wander around a large university building.

Students Who Miss Exams You have a variety of alternatives available on how to treat students who miss a scheduled exam. Select those that fit your course and the requirements of learning students must demonstrate.

Requiring make-up exams. If you collect all copies of your multiple choice or short answer exams, you may be able to use the same exam for make-ups. Our experience is that it is extremely rare that students deliberately miss an exam to have more time to study, whereas asking peers about specific exam questions more commonly occurs. Your experiences may be different. However, if you put exams on file at the university testing center, and students can take them weeks apart, you may want different forms. If you have concerns, you will need to prepare an equivalent, alternative form of the regular exam, as is often the case for essay tests.

Using procedures other than a make-up exam. Some faculty have students outline all text chapters required for an exam, use daily quiz scores to substitute for a missed exam, use the average of students’ exams to substitute for the one missed, score relevant questions on the comprehensive final to substitute for the missed test, or use a weighted score from the entire comprehensive final substituted for missed exam. Some teachers just drop one test grade without penalty (Buchanan&Rogers, 1990; Sleigh&Ritzer, 2001). Consider whether students will learn what you want from various alternatives and whether this work is equal to what students must demonstrate on exams before adopting such procedures. If your course contains numerous graded assignments of equal difficulty, and if it is equitable for students to choose to ignore a course module by not studying or taking the exam, you should consider this process.

Other teachers build extra credit into the course. They allow all students opportunities to raise their grades, offering a safety net of sorts for those who need to “make-up” a missed exam by doing “additional” assignments such as outlining unassigned chapters in the text.

Scheduling make-ups. Pick one or two times a week that are convenient for you, a department secretary, or teaching assistant, and schedule your make-ups then. Some faculty use a common time midway through the semester and at the end of the semester as an alternative.

Students Who Miss Other In-Class Assignments Allowing students to demonstrate learning on non-exam graded assignments can be tricky. Such assignments often measure different kinds of learning than exams: the ability to work in groups, critical thinking as demonstrated in a poster, or an oral presentation graded in part on professional use of language. But you do have some alternatives.

Keeping the required assignment the same. If the assignment is a large one and due near the end of the semester, consider using an “incomplete” grade for students who miss it. Alternatively, students can present their oral work or poster in another course you are teaching if the content is relevant and time allows it. The oral required assignment also can be delivered just to the teacher or videotaped or turned in on audiotape.

Alternative assignments. As with missed exams, you can weigh other assignments disproportionately to substitute for in-class graded work — by doubling a similar assignment if you have more than one during the semester, for example. The dilemma, of course, is not allowing students easy avenues to avoid a required module or assignment without penalty. For example, oral assignments can be turned in as written work, although this may negate some of the reasons for the assignment.

When we asked colleagues about alternatives for missed in-class graded assignments (as compared with exams), almost everyone cautioned against listing them in the course syllabus. They felt that students could then weigh the make-up assignment versus the original and choose the one that gave them the greatest chance of doing well, and also the least amount of anxiety (in-class presentations often make students nervous). They recommended simply telling students that arrangements would be made for those missing in-class required graded work on a case-by-case basis.

Students Who Miss the “Make-Up” On occasion, students will miss a scheduled make-up. Say something about this event in your syllabus, emphasizing the student’s responsibility to notify the instructor. We recommend that instructors reserve the right to lower a student’s grade by “x” number of points, or “x” letter grades. If you place exams at a university testing center, you may not find out the work has not been made up until the course is over, leaving you little choice but to give the student an “F” on that exam or assignment.

When the Whole Class Misses a Required Exam or Assignment On rare, but very memorable, occasions the entire class may miss an exam or assignment. For example, both authors have had the fire alarm go off during an exam. After a bomb threat cleared the building during his exam, the campus police actually contacted one author to identify whether a person caught on camera at a service station was a student calling in the bomb scare. (It was not.) The other author experienced the bomb squad closing a classroom building during finals week due to the discovery of old, potentially explosive, laboratory chemicals. Of course, the blizzard of the century or a flood might occur the night before your exam. What is a teacher to do?

The exam or graded assignment must be delayed. Prepare beforehand. Always build a make-up policy into your syllabus for the last exam or student presentation in a course. Talk with your department chair or dean about college or university policy. State that if weather or other circumstances force a make-up, it will occur at a certain time and place. This forethought is especially important if you teach at a northern institution where bad winter weather is not unusual. For exams and assignments during the semester, the policy that works best is to reschedule them (again, stating this in your syllabus) for the next regular class period. Call attention to this policy early in the semester, and post it on your course Web site. The last thing you want to do is call or e-mail everyone in the class to tell them an exam has been cancelled.

An exam or graded assignment is interrupted. Graded assignments such as oral presentations are easily handled. If time allows, continue after the interruption; if not, continue the next class period or during your designated “make-up” time.

If something interrupts an exam, ask students to leave their exams and answers on their desks or hand them in to you, take all personal materials, and leave immediately. A teacher can easily collect everything left in most classes in a few moments. Leave materials on desks if the class is large, or be the first person back to the room after the interruption. Fire alarms, bomb scares, and the like usually cause a lot of hubbub. Only if you have a lengthy two- or three-hour class, with time to allow students to collect themselves and refocus, and no concern about their comparing answers to questions during the delay, should the exam be continued that same day or evening.

If the interruption occurs late in the class period, you might tell students to turn in their work as they leave. You can then determine how you want to grade exams or the assignment, using pro-rated points or percentages, and assign grades accordingly.

If the interruption is earlier in the hour, the exam will have to be delayed, usually until the next class period. With a multiple-choice exam, we advise giving students the full (next) class period to finish their exams. If you are concerned about students comparing questions they have already answered, you will have to quickly develop an alternate exam.

A teacher’s decisions are more complicated if the exam is short answer or essay. Students may have skimmed all essay or short answer questions before an interruption. Will they prepare for those questions before the next class period? What if some students only read the first essay question but do not know the others they must answer? Preparing an alternate exam may be feasible, but students need to know you will do so, so they do not concentrate their studying on specific topics you will not ask about.

We know that such class interruptions are rare, but they can wreak havoc with students and teachers, be stressful, and raise issues of fairness that echo throughout the rest of the course. We advise teachers to talk with colleagues, and we have found a department brown bag on the topic fascinating. Your colleagues may have some creative and sound advice.

Summary A teacher needs to plan ahead. Take some time to think about what it means for you and students who miss required in-class work. A little preparation can save a lot of time and hassle later in the semester. Students deserve and will appreciate policies that are equitable and manageable.

Author’s Note: The authors are interested how teachers deal with missed or interrupted graded in-class work (and their horror stories). Contact us with your ideas and experiences at [email protected] .

References and Recommended Reading

- Buchanan, R. W., & Rogers, M. (1990). Innovative assessment in large classes. College Teaching, 38 , 69-74.

- Carper, S. W. (1995). Make-up exams: What’s a professor to do? Journal of Chemical Education, 72 , 883.

- Davis, B. G. (1993). Tools for teaching . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Keith-Spiegel, P., Whitley, B.G. E. Jr., Balogh, D. W., Perkins, D. V., & Wittig, A. F. (2002). The ethics of teaching: A casebook (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- McKeachie, W. J. (2001). Teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (11th ed.) Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Nilson, L. B. (2003). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (2nd ed). Bolton, MA: Anker.

- Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (in press). Teacher evaluations of make-up exam procedures. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 3 (2).

- Sleigh, M. J., & Ritzer, D. R. (2001). Encouraging student attendance. APS Observer, 14 (9), pp. 19-20, 32.

Do you know of any research related to taking points off an exam for students who take a make-up for whatever reason? It is mentioned in this article but I’m interested in evidence to back up that it is fair and/or punitive in a college setting with adult learners. Thank you. Gerri Russell, MS, RN

I teach introductory nutrition and other biology classes. If a student can prove that they missed an exam or assignment for a verifiable reason, even if they let me know ahead of time (usually technology related reasons), I let them make it up without taking points off. If they can’t prove it I take off points as follows: 10% off per day late during the first week after the assignment is due. Half credit earned after that. Even if they know there are always students who just miss things for no apparent good reason. I feel like this is fair because it gives them the responsibility for making it up, and I’d rather people become familiar with the material, rather than just not do it at all.

I think that the mid semester tests must be abolished from all colleges/universities in order to let them prepare for the final exams without any pressure of getting grades,this will not give rise to any decompetition then,so I personally feel that my suggestion will be very useful I want everyone to obey that

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Author

BARON PERLMAN is editor of "Teaching Tips." A professor in the department of psychology, distinguished teacher, and University and Rosebush Professor at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh in the department of psychology, he has taught psychology for 29 years. He continues to work to master the art and craft of teaching. LEE I. MCCANN is co-editor of "Teaching Tips." A professor in the department of psychology and a University and Rosebush Professor at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, he has taught psychology for 38 years. He has presented numerous workshops on teaching and psychology curricula, his current research interests.

Student Notebook: Five Tips for Working with Teaching Assistants in Online Classes

Sarah C. Turner suggests it’s best to follow the golden rule: Treat your TA’s time as you would your own.

Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been

European Psychology Learning and Teaching Conference

The School of Education of the Paris Lodron University of Salzburg is hosting the next European Psychology Learning and Teaching (EUROPLAT) Conference on September 18–20, 2017 in Salzburg, Austria. The main theme of the conference

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

College of Business

Assignments, exams, & grading.

When we hear the word “assessment,” most of us think about course assignments and exams . While assignments and assessments are not the same thing, assignments are often used as formative or summative assessments of student learning. As formative assessments, assignments can support the scaffolding of student learning, allowing students to practice new skills so they are able to apply them in more complex projects. Instructors can provide timely feedback to support skill-building and correct errors. As summative assessments, assignments can help instructors evaluate student achievement of learning outcomes.

Grades are a hot topic for students and faculty alike, as they can determine a student’s status, scholarship eligibility, and future prospects. Instructor grading practices and philosophies can vary, often causing student anxiety and concern. Faculty conversations about grades often focus on fairness, rigor, equity, and how to truly measure learning.

The growing set of resources on this site will explore good practices for transparent and equitable assignment design, exam design and administration practices, as well as the array of conversations around grading practices. Alternative grading practices such as Ungrading and contract grading have piqued the curiosity of instructors looking for ways to engage students in their own learning and make learning rather than grades the primary focus of instruction.

Read More About Assignments, Exams, & Grading

Creating and using rubrics for assignments.

What is a Rubric? A rubric is a guide that articulates the expectations for an assignment and communicates the level of quality of performance or learning. As an assessment tool, a rubric sets the criteria for evaluating performance or work

Facilitating and Assessing Student Engagement in the Classroom

Improving student engagement in the classroom is a hot topic amongst faculty these days. At some point in the conversation, the mythological college student makes an appearance. That perfect student of the past was always on time, had always done

Mapping Your Course

Backwards Design Basics When you are planning a road trip, you probably start with the places you want to end up and then plan your route, including overnight stops, food options, and perhaps a few scenic spots to rest along

Online or Remote Exams: Considerations and Effective Practices

Remote, hybrid, and online teaching and learning have prompted most instructors to rethink course instruction and question previously held assumptions about how people learn. How to administer exams can be a particularly thorny issue, especially for courses with large enrollments

Assessment in Large Enrollment Courses

Many of my conversations with faculty focus on the challenges they have with doing good learning assessment in large classes. The best learner-centered assessment approaches are no match for 200-person enrollment. I mean, can you imagine reading 200 5-page essays?

Grade Calculator

Use this calculator to find out the grade of a course based on weighted averages. This calculator accepts both numerical as well as letter grades. It also can calculate the grade needed for the remaining assignments in order to get a desired grade for an ongoing course.

Final Grade CalculatorUse this calculator to find out the grade needed on the final exam in order to get a desired grade in a course. It accepts letter grades, percentage grades, and other numerical inputs. Related GPA Calculator The calculators above use the following letter grades and their typical corresponding numerical equivalents based on grade points.

Brief history of different grading systemsIn 1785, students at Yale were ranked based on "optimi" being the highest rank, followed by second optimi, inferiore (lower), and pejores (worse). At William and Mary, students were ranked as either No. 1, or No. 2, where No. 1 represented students that were first in their class, while No. 2 represented those who were "orderly, correct and attentive." Meanwhile at Harvard, students were graded based on a numerical system from 1-200 (except for math and philosophy where 1-100 was used). Later, shortly after 1883, Harvard used a system of "Classes" where students were either Class I, II, III, IV, or V, with V representing a failing grade. All of these examples show the subjective, arbitrary, and inconsistent nature with which different institutions graded their students, demonstrating the need for a more standardized, albeit equally arbitrary grading system. In 1887, Mount Holyoke College became the first college to use letter grades similar to those commonly used today. The college used a grading scale with the letters A, B, C, D, and E, where E represented a failing grade. This grading system however, was far stricter than those commonly used today, with a failing grade being defined as anything below 75%. The college later re-defined their grading system, adding the letter F for a failing grade (still below 75%). This system of using a letter grading scale became increasingly popular within colleges and high schools, eventually leading to the letter grading systems typically used today. However, there is still significant variation regarding what may constitute an A, or whether a system uses plusses or minuses (i.e. A+ or B-), among other differences. An alternative to the letter grading systemLetter grades provide an easy means to generalize a student's performance. They can be more effective than qualitative evaluations in situations where "right" or "wrong" answers can be easily quantified, such as an algebra exam, but alone may not provide a student with enough feedback in regards to an assessment like a written paper (which is much more subjective). Although a written analysis of each individual student's work may be a more effective form of feedback, there exists the argument that students and parents are unlikely to read the feedback, and that teachers do not have the time to write such an analysis. There is precedence for this type of evaluation system however, in Saint Ann's School in New York City, an arts-oriented private school that does not have a letter grading system. Instead, teachers write anecdotal reports for each student. This method of evaluation focuses on promoting learning and improvement, rather than the pursuit of a certain letter grade in a course. For better or for worse however, these types of programs constitute a minority in the United States, and though the experience may be better for the student, most institutions still use a fairly standard letter grading system that students will have to adjust to. The time investment that this type of evaluation method requires of teachers/professors is likely not viable on university campuses with hundreds of students per course. As such, although there are other high schools such as Sanborn High School that approach grading in a more qualitative way, it remains to be seen whether such grading methods can be scalable. Until then, more generalized forms of grading like the letter grading system are unlikely to be entirely replaced. However, many educators already try to create an environment that limits the role that grades play in motivating students. One could argue that a combination of these two systems would likely be the most realistic, and effective way to provide a more standardized evaluation of students, while promoting learning.

Search form

Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

You are hereGrades and grading, the problem with grades. Grading is a perpetually thorny issue. No one likes to assign grades, but virtually everyone acknowledges the necessity of doing so. Grading can be the cause of sleepless nights for students and teachers alike, as well as the source of frustration and dispute when two parties disagree over the appropriateness of a grade. Why this strife? Grading is about standards, and standards imply judgment. Quantitative disciplines are somewhat advantaged in this area because people who teach these subjects use judgments like “right and wrong,” while people in the humanities and other argument-oriented disciplines are stuck with “better and worse.” No one gets off easy in this grading game. Many students will flee quantitative subjects convinced that such disciplines are tyrannical and uncreative. Those same students run back after a semester in the humanities, hissing all the way that grading is subjective, personal, and unfair. Scylla, meet Charybdis. Rock, meet hard place. But maybe this predicament is caused not by the standards but by the way we apply them—or fail to apply them—throughout the semester. In quantitative subjects, running through a series of problems without giving students the opportunity to consider the whence, whither, and wherefore doesn’t exactly inspire them to think, excite their curiosity, or make them feel like they’re part of the game. No wonder they’re peeved when the questions on the test require original or high-level thought. Conversely, we may be setting students up for disappointment and frustration in the humanities when their contributions in section—no matter how far afield, poorly argued, or lacking in evidence—are greeted with a smile of approval, only to be skewered when that same level of thought appears in a paper. The point is, standards aren’t just for tests. They’re for learning, thinking, discussing, the whole shebang. View grades not solely as big red letters written atop each assignment and quiz, but within the larger context of feedback. So explain the standards to your students, apply the standards (nicely) during discussion and problem solving, and show your students that you, your section, and their hard work are the ticket to meeting them. You’ll be a lot better off at grading time. But your students are not the only ones who should be getting feedback in the classroom. A person’s teaching, as with any other activity, only improves with practice and constructive criticism. The practice will come with time; The Tables Turn! Students Evaluating You will suggest ways to elicit that constructive criticism. Why Grading is So Hard: The Jekyll and Hyde EffectMost TFs begin their semester with the hope that they will be great teachers: their students will be inspired, they will learn the material, they will do the work, and they will get good grades — all because we, as teachers, will guide them through. But eventually they hand in an assignment and we are suddenly transformed into the merciless arbiter of an impersonal standard. No longer are we the friendly, helpful TFs that we once were. We are the Grim Grader, slashing at the fields of undergraduate effort with the sharp scythes of A- and B+. We change hats; we shift loyalties. No wonder there’s some emotional fallout. Easing the PainThe best way to alleviate some of the tension between your roles as helper and evaluator is to set clear expectations and standards at the outset, preferably in writing. Students need to know what constitutes an A paper, what constitutes a B paper, and, heaven forbid, what constitutes an F (yes, Virginia, there are grades lower than C). Are students graded on attendance? Class participation? Will papers be graded on style as well as content? You don’t necessarily have to come up with these guidelines on your own, though: check with the supervising faculty member to see if any standards or grading strategies have already been set. With such explicit expectations in place, students will be far more understanding when you make the leap from Joe Smiley the TF to judge, jury, and executioner. (Don’t worry, there haven’t been any real executions at Yale since the 1950s.) By setting clear standards at the outset, you’ll avoid a lot of student complaints about your grading. Here are some suggestions for making those standards clear. Have All the AnswersIn grading exams, lab reports, and problem sets, consider preparing an answer key (or some clear indication of what made for an average/better/excellent answer) and making it available to your students—perhaps posted outside your office or on the class web site. Provide the correct answer to each question and indicate which responses earned partial credit and how many points you’ve deducted for certain errors. You can then have students compare their work to this model before coming to you with complaints or questions about grading. Samples of BrillianceWeaker writers often have no idea what a strong paper looks like, and they will have great difficulty improving their writing if they don’t see what to change. Consider distributing sample papers to let students know what you consider to be worthy of a high grade. You might also find that a few of your best writers will be willing to have their papers made available (anonymously, of course) for future students to read and learn from. Put That Preaching into PracticeMake reference to the written guidelines you give students when you comment on their work so that they can see where their performance does or does not measure up to your expectations. In the course of your first semester of teaching, you may find that you develop a new set of instructions (written or unwritten) for preparing a good term paper, problem set, or lab report. The next time you teach, write up these standards and discuss them with students before the first assignment is due. Approaches to, and Techniques for, Grading FairlyClear expectations serve a useful purpose only if they’re fairly and consistently enforced. In other words, you can’t run a classroom in which attendance counts against you only if you’re a registered Republican. In a course where all students complete identical problem sets, papers, or exams, the same criteria must be applied in grading each student’s work. Here are some suggestions for increasing consistency, which can be applied in many different situations. Grade the Question, Not the StudentWhen grading an exam or assignment with multiple sections, grade all responses to the same question (or set of related questions) together. This makes it less likely that a student’s overall level of performance on the exam or assignment will cause you to give a grade for a particular section that is undeservedly high or low. Naturally, this approach is about as exciting as an evening with C-SPAN, but the good and poor performances will stand out much more clearly this way than if you alternate among topics or question formats, and it will be easier for you to develop and adhere to consistent scoring criteria. The item-by-item approach also works well if there are multiple TFs for the same course. If each of you grades a particular question or group of questions on every exam, you’ll be in a better position to assure students that everyone’s work has been evaluated in the same way. Waiting for GodotAs you begin grading a particular assignment or exam question, read through several students’ answers without marking grades. At the very least, restrict yourself to tentative marks in pencil. This will give you a sense of the overall range of students’ responses before you start inscribing final grades in indelible red ink. Although you’ll probably think about the components of a good answer before reading any exams at all, students will occasionally surprise you by interpreting the question very differently from what you or the professor had in mind. Similarly, a question will sometimes prove to be much more difficult than you anticipated. Because such problems are often the fault of the testing instrument rather than of the student, it’s important that you understand how students are actually approaching the question before you begin to grade. After you finish grading, review the first few assignments you graded. You will often find that you were much nastier with the red ink at the beginning of the grading process than at the end, and you may be pleasantly surprised to find that some of the first assignments you graded made points other students failed to mention. You will also have developed a more refined sense of a “good” as opposed to an “average” or “weak” performance over the course of your grading, and you may realize that the first assignments you read were better (or worse) than you initially thought. For these reasons, you may not want to mark any grades in pen until you’ve finished with the whole set of exams or papers and are happy with the distribution of grades as a whole. Grade BlindIf you’ve come to know your students well in section or lab, you may have definite expectations, hopes, or fears about their performance on major assignments. In order to avoid being influenced by what you know or anticipate about a student’s work, you might want to keep the grading as anonymous as possible: just fold back the cover sheet of each paper or exam so that you can’t see the student’s name. (If you want to do this with papers, you should make a point of asking students to include their name only on the cover page.) Grading without regard to students’ identities does not prevent you from commenting on how students’ work has progressed (or degenerated) over the course of the semester. Once the actual assigning of letter grades is complete, you can always go back to your written comments and praise students who have made notable improvements (or caution students who have done the reverse). Partners in CrimeNo TF is an island. Cooperation with other TFs can take different forms, each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages.

What to Do When Students Challenge Your GradeA common scenario: you return students’ papers and, after the usual period of sighing and moaning, a student approaches you with the dreaded “I’d like to talk to you about my grade.” What then? Wait a MinuteThe first thing to do is stall for time. No joke. Don’t be pressured into hearing a case and making a decision on the spot. There will probably be other students around, and you might be in a rush to get out of the classroom. Unless the grade change is truly minor and unquestionable, set up another time when you can give the student your full consideration (within a few days, to be fair). Then, before you meet the student, take some time to remind yourself what your grading standards are. Also, if you have the student’s paper available, reconsider how the paper fits those standards (it’s always a good idea to make copies of your comments for future reference). Another option is to have the student write out his or her side of the story and turn it in with a copy of the exam or paper. That way, you’ll have time to review the case before meeting to discuss it. If the case really is clear-cut and simple, it won’t take long to explain it, and it won’t take you long to make a decision on the merits of the student’s case. Let students talk during such conferences. In fact, let them talk a lot. Resist the temptation to jump in with your defense. Shouting, “Zip it! You failed!” will only exacerbate the situation. Many students take getting a bad grade very personally, so don’t escalate things by making the grading process personal as well. Why do students complain about a grade? There are several possibilities.

Dealing with the last possibility can be frustrating, but don’t assume that that’s the reason when in fact any of the other possibilities might be the case. (We don’t have to tell you what happens when you assume, do we?) Always imagine that your student has higher motives, and aim your conversation at that level. You can always give the student the option of having the supervising professor read and re-evaluate the paper or exam. Just be sure to remind the student that the grade could go down even further. One last thing: if you allow a student to rewrite a paper, make sure that you allow every student that opportunity. In this case, it can’t be only the squeaky wheel that gets the grease. You gotta grease ’em all. “Grade Compression” (Or, Grading from A to…C?)Once upon a time, in universities far, far away, getting a C meant that your performance was average. A was at the top, F was at the bottom, and C was cleverly placed right in the middle (don’t ask what happened to E). But now we live in the world of Upward Grade Homogenization (UGH, commonly called Grade Inflation or — as Yale prefers it, “grade compression”), where most students, TFs, and professors consider C to be a bad grade—not the worst possible grade, mind you, but certainly less than average. So, the question is, what are the possible effects of UGH on your grading procedures?