Lauren's Rhet 102 Webpage

Essay 1 Reflection and Revision

Reflection of Essay 1:

To revise my paper Professor gave me a tip to help in my revision process. The advice that she gave me stated that I need to fix a few minute errors, which is typical of revisions, but she also gave me the advice to alter my conclusion completely so that it does not the typical “five paragraph format.”

My paper did not have too many grammatical errors, but I did fix the few that were present. The bigger element to my revision consisted of me completely revamping my conclusion.

To revise my conclusion I made sure I answered the question of so what. I now realize that a conclusion is not just a summary of your paper but rather a sum of what points should be take away from the paper. I now realize that a conclusion my final chance to leave a lasting impression of my readers.

I watch a video on conclusions to help improve my conclusions. This video helped me understand the exact purpose of conclusions. I was so used to just writing papers in the 5 five paragraph format that I thought a conclusion was just a restatement of my paper in one tiny paragraph, and I thought that a conclusion was just a regurgitation of my introduction. I have since learned that my conclusion is more like my opinion and should leave readers thinking about my paper and understanding the significance of my paper. Watching the video on conclusions really worked in sense of really helping me understand the purpose of conclusions and how to write them.

Video that aided in my revision of my conclusion:

Revision of Essay 1:

Revised Rhet 102 essay #1

A publish.illinois.edu site

Encyclopedia

Writing with artificial intelligence, reflection essay.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Kristen Gay

At first glance, academic and reflection can sound like contradictory concepts. Writing an academic reflection essay often involves striking a balance between a traditional, academic paper and a reflective essay. In order to find this balance, consider the terms that encompass the title of the assignment

The term “academic” suggests that the writer will be expected to observe conventions for academic writing, such as using a professional tone and crafting a thesis statement. On the other hand, the term “reflection” implies that the writer should critically reflect on their work, project, or writing process, depending on the assignment, and draw conclusions based on these observations.

In general, an academic reflection essay is a combination of these two ideas: writers should observe conventions for academic writing while critically reflecting on their experience or project. Note that the term “critically” suggests that the writing should not merely tell the reader what happened, what you did, or what you learned. Critical reflection takes the writing one step further and entails making an evaluative claim about the experience or project under discussion. Beyond telling readers what happened, critical reflection tends to discuss why it matters and how it contributed to the effectiveness of the project.

Striking the proper balance between critical reflection and academic essay is always determined by the demands of the particular writing situation, so writers should first consider their purpose for writing, their audience, and the project guidelines. While the subject matter of academic reflections is not always “academic,” the writer will usually still be expected to adapt their arguments and points to academic conventions for thesis statements, evidence, organization, style, and formatting.

Several strategies for crafting an academic reflection essay are outlined below based on three important areas: focus, evidence, and organization.

A thesis statement for an academic reflection essay is often an evaluative claim about your experiences with a process or assignment. Several strategies to consider for a thesis statement in an academic reflection essay include:

- Being Critical: It is important to ensure that the evaluative claim does not simply state the obvious, such as that you completed the assignment, or that you did or did not like it. Instead, make a critical claim about whether or not the project was effective in fulfilling its purpose, or whether the project raised new questions for you to consider and somehow changed your perspective on your topic.

- Placement: For some academic reflection essays, the thesis may not come in the introduction but at the end of the paper, once the writer has fully explained their experiences with the project. Think about where the placement of your thesis will be most effective based on your ideas and how your claim relates to them.

Consider the following example of a thesis statement in an academic reflection essay:

By changing my medium from a picture to a pop song, my message that domestic violence disproportionately affects women was more effectively communicated to an audience of my classmates because they found the message to be more memorable when it was accompanied by music.

This thesis makes a critical evaluative claim (that the change of medium was effective) about the project, and is thus a strong thesis for an academic reflection paper.

Evidence for academic reflection essays may include outside sources, but writers are also asked to support their claims by including observations from their own experience. Writers might effectively support their claims by considering the following strategies:

- Incorporating examples: What examples might help support the claims that you make? How might you expand on your points using these examples, and how might you develop this evidence in relation to your thesis?

- Personal anecdotes or observations: How might you choose relevant personal anecdotes/observations to illustrate your points and support your thesis?

- Logical explanations: How might you explain the logic behind a specific point you are making in order to make it more credible to readers?

Consider the following example for incorporating evidence in an academic reflection essay:

Claim: Changing the medium for my project from a picture to a pop song appealed to my audience of fellow classmates.

Evidence: When I performed my pop song remediation for my classmates, they paid attention to me and said that the message, once transformed into song lyrics, was very catchy and memorable. By the end of the presentation, some of them were even singing along.

In this example, the claim (that the change of medium was effective in appealing to the new audience of fellow classmates) is supported because the writer reveals their observation of the audience’s reaction. (For more about using examples and anecdotes as examples, see “Nontraditional Types of Evidence.”)

Organization

For academic reflection essays, the organizational structure may differ from traditional academic or narrative essays because you are reflecting on your own experiences or observations. Consider the following organizational structures for academic reflection essays:

- Chronological Progression: The progression of points will reflect the order of events/insights as they occurred temporally in the project.

Sample Chronological Organization for a Remediation Reflection:

Paragraph 1: Beginning of the project

Paragraph 2: Progression of the remediation process

Paragraph 3: Progression of the remediation process

Paragraph 4: Progression of the remediation process

Paragraph 5: Progression of the remediation process

Paragraph 6: Conclusion—Was the project effective. How and why? How did the process end?

- By Main Idea/Theme: The progression of points will centralize on main ideas or themes of the project.

Sample Organization By Main Idea/Theme for a Remediation Reflection:

Paragraph 1: Introduction

Paragraph 2: Discuss the message being translated

Paragraph 3: Discuss the change of medium

Paragraph 4: Discuss the change of audience

Paragraph 5: Was the change effective? Explain.

Paragraph 6: Conclusion

Remember that while these strategies are intended to help you approach an academic reflection paper with confidence, they are not meant to be prescriptive. Academic reflection essays are often unique to the writer because they ask the writer to consider their observations or reactions to an experience or project. You have distinctive ideas and observations to discuss, so it is likely that your paper will reflect this distinctiveness. With this in mind, consider how to most effectively compose your paper based on your specific project guidelines, instructor suggestions, and your experiences with the project.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

📕 Studying HQ

Ultimate Guide to Writing a Reflective Essay

Carla johnson.

- June 14, 2023

- How to Guides

Writing about yourself is a powerful way to learn and grow as a person. It is a type of writing that makes you think about your thoughts, feelings, and experiences and how they have affected your personal and professional growth. A reflective essay is a type of writing that lets you talk about your own experiences, thoughts, and insights. In this article , we’ll tell you everything you need to know about writing a reflective essay, from how to define it and figure out what it’s for to how to do it well.

What You'll Learn

Definition of a Reflective Essay

A reflective essay is a type of writing in which you write about your own thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It is a type of personal writing that lets you talk about your own thoughts and experiences and share them with other people. Students are often asked to write reflective essays for school, but they can also be used for personal or professional growth.

Purpose of a Reflective Essay

The goal of a reflective essay is to get you to think about your life and how it has affected your personal and professional growth. Reflective essays can help you learn more about yourself and your experiences, as well as find places where you can grow and improve. They can also help you get better at writing and better at getting your ideas across.

Importance of Reflective Writing

Writing about yourself and your work is an important way to grow personally and professionally. It can help you learn more about yourself, figure out where you need to grow and change, and learn more about how you think and feel. Writing about yourself can also help you get better at critical thinking and analysis , and it can help you get your ideas across better. It is a useful tool for anyone who wants to grow personally and professionally, and it can be used in many different situations, from academic writing to keeping a personal journal.

Writing about yourself and your work is a powerful way to grow personally and professionally. Reflective essays give you a chance to think about your own life and how it has affected your personal and professional growth. By writing about your thoughts and feelings, you can learn more about them, find ways to grow and improve, and improve your writing and communication skills . In the next parts of this article, we’ll show you how to write a good reflective essay step by step, from choosing a topic and organizing your thoughts to writing and revising your essay.

Elements of a Reflective Essay

A reflective essay is a type of writing that allows you to reflect on your personal experiences, thoughts, and feelings. There are several essential elements that should be included in a reflective essay to ensure that it is effective in conveying your personal reflections and experiences.

Personal Reflection

The first essential element of a reflective essay is personal reflection. This involves exploring your own thoughts and feelings about the experience you are reflecting on. It is important to be honest and open about your thoughts and feelings, as this will make your essay more authentic and meaningful.

Description of the Experience

The second element of a reflective essay is a description of the experience that you are reflecting on. This includes providing details about the experience, such as where it took place, who was involved, and what happened. The description should be clear and concise, and should provide enough detail for the reader to understand the context of your reflection.

Analysis of the Experience

The third element of a reflective essay is analysis of the experience. This involves exploring the experience in more depth, and examining your thoughts and feelings about it. You should consider what you learned from the experience, and how it impacted your personal and professional growth .

Evaluation of the Experience

The fourth element of a reflective essay is evaluation of the experience. This involves examining the experience from different perspectives, and considering its strengths and weaknesses. You should reflect on what you would do differently if you were in the same situation again, and how you could improve your response or approach.

Identification of Key Learning

The fifth element of a reflective essay is identifying the key learning that you gained from the experience. This involves reflecting on the insights and lessons that you learned from the experience, and how these have impacted your personal and professional growth. This can include new skills, knowledge, or perspectives that you gained from the experience.

Planning for Future Action

The final element of a reflective essay is planning for future action. This involves considering how you can apply the lessons and insights gained from the experience to improve your future actions. You should reflect on how you can use what you learned to approach similar situations differently in the future.

How to Write a Reflective Essay

Writing a reflective essay can be a challenging task, but by following a few simple steps, you can write an effective and meaningful essay .

Steps for Writing a Reflective Essay:

1. Brainstorming and Selecting a Topic

Begin by brainstorming and selecting a topic for your reflective essay. Think about a personal experience or event that had a significant impact on your personal or professional growth.

2. Creating an Outline

Create an outline for your essay . This should include an introduction, body, and conclusion, as well as sections for each of the essential elements described above.

3. Writing the Introduction

Write the introduction for your essay . This should include a brief overview of the experience that you will be reflecting on, as well as the purpose and focus of your essay.

4. Writing the Body

Write the body of your essay, which should include the personal reflection, description of the experience, analysis of the experience, evaluation of the experience, identification of key learning, and planning for future action . Make sure to use specific examples and details to support your reflection.

5. Writing the Conclusion

Write the conclusion for your essay , which should summarize the key points of your reflection and provide closure for the reader. You can also include a final reflection on the experience and what it means to you.

6. Revising and Editing

Pay close attention to grammar, spelling, and sentence structure as you reread and edit your essay . Make sure your essay is easy to read and flows well. You might also want someone else to look over your essay and give you feedback and ideas.

If you follow these steps, you should be able to write a good reflective essay. Remember to be honest and open about your thoughts and feelings, and to support your reflection with specific examples and details. You can become a good reflective writer with practice , and you can use this skill to help your personal and professional growth.

Reflective Essay Topics

Reflective essays can be written on a wide range of topics, as they are based on personal experiences and reflections. Here are some common categories of reflective essay topics:

Personal Experiences

– A time when you overcame a personal challenge

– A difficult decision you had to make

– A significant event in your life that changed you

– A moment when you learned an important lesson

– A relationship that had a significant impact on you

Professional Experiences

– A challenging project or assignment at work

– A significant accomplishment or success in your career

– A time when you had to deal with a difficult colleague or boss

– A failure or setback in your career and what you learned from it

– A career change or transition that had a significant impact on you

Academic Experiences

– A challenging course or assignment in school

– A significant accomplishment or success in your academic career

– A time when you struggled with a particular subject or topic and how you overcame it

– A research project or paper that had a significant impact on you

– A teacher or mentor who had a significant impact on your academic career

Cultural Experiences

– A significant trip or travel experience

– A significant cultural event or celebration you participated in

– A time when you experienced culture shock

– A significant interaction with someone from a different culture

– A time when you learned something new about a different culture and how it impacted you

Social Issues

– A personal experience with discrimination or prejudice

– A time when you volunteered or worked for a social cause or organization

– A significant event or moment related to a social issue (e.g. protest, rally, community event)

– A time when you had to confront your own biases or privilege

– A social issue that you are passionate about and how it has impacted you personally

Reflective Essay Examples

Example 1: Reflecting on a Personal Challenge

In this reflective essay, the writer reflects on a personal challenge they faced and how they overcame it. They explore their thoughts, feelings, and actions during this time, and reflect on the lessons they learned from the experience.

Example 2: Reflecting on a Professional Experience

In this reflective essay, the writer reflects on a challenging project they worked on at work and how they overcame obstacles to successfully complete it. They explore their thoughts and feelings about the experience and reflect on the skills and knowledge they gained from it.

Example 3: Reflecting on an Academic Assignment

In this reflective essay, the writer reflects on a challenging academic assignment they completed and how they overcame difficulties to successfully complete it. They explore their thoughts and feelings about the experience and reflect on the skills and knowledge they gained from it.

Example 4: Reflecting on a Cultural Experience

In this reflective essay, the writer reflects on a significant cultural experience they had, such as traveling to a new country or participating in a cultural event. Theyexplore their thoughts and feelings about the experience, reflect on what they learned about the culture, and how it impacted them personally.

Example 5: Reflecting on a Social Issue

In this reflective essay, the writer reflects on their personal experiences with discrimination or prejudice and how it impacted them. They explore their thoughts and feelings about the experience, reflect on what they learned about themselves and the issue, and how they can take action to address it.

These examples demonstrate how reflective essays can be used to explore a wide range of personal experiences and reflections. By exploring your own thoughts and feelings about an experience, you can gain insights into your personal and professional growth and identify areas for further development . Reflective writing is a powerful tool for self-reflection and personal growth, and it can be used in many different contexts to help you gain a deeper understanding of yourself and the world around you.

Reflective Essay Outline

A reflective essay should follow a basic outline that includes an introduction, body, and conclusion. Here is a breakdown of each section:

Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the experience you will be reflecting on and a preview of the key points you will be discussing in your essay .

Body: The body of the essay should include several paragraphs that explore your personal reflection, description of the experience, analysis of the experience, evaluation of the experience, identification of key learning, and planning for future action.

Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the key points of your reflection and provide closure for the reader.

Reflective Essay Thesis

A reflective essay thesis is a statement that summarizes the main points of your essay and provides a clear focus for your writing. A strong thesis statement is essential for a successful reflective essay, as it helps to guide your writing and ensure that your essay is focused and coherent.

Importance of a Strong Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement is important for several reasons. First, it provides a clear focus for your writing, which helps to ensure that your essay is coherent and well-organized. Second, it helps to guide your writing and ensure that you stay on topic throughout your essay . Finally, it helps to engage your reader and provide them with a clear understanding of what your essay is about.

Tips for Writing a Thesis Statement

To write a strong thesis statement for your reflective essay, follow these tips:

– Be clear and concise: Yourthesis statement should clearly state the main focus and purpose of your essay in a concise manner.

– Use specific language: Use specific language to describe the experience you will be reflecting on and the key points you will be discussing in your essay .

– Make it arguable: A strong thesis statement should be arguable and provide some insight or perspective on the experience you are reflecting on.

– Reflect on the significance: Reflect on the significance of the experience you are reflecting on and why it is important to you.

Reflective Essay Structure

The structure of a reflective essay is important for ensuring that your essay is well-organized and easy to read. A clear structure helps to guide the reader through your thoughts and reflections, and it makes it easier for them to understand your main points.

The Importance of a Clear Structure

A clear structure is important for several reasons. First, it helps to ensure that your essay is well-organized and easy to read. Second, it helps to guide your writing and ensure that you stay on topic throughout your essay. Finally, it helps to engage your reader and provide them with a clear understanding of the key points you are making.

Tips for Structuring a Reflective Essay

To structure your reflective essay effectively, follow these tips:

– Start with an introduction that provides an overview of the experience you are reflecting on and a preview of the key points you will be discussing in your essay .

– Use body paragraphs to explore your personal reflection, description of the experience, analysisof the experience, evaluation of the experience, identification of key learning, and planning for future action. Ensure that each paragraph has a clear focus and supports your thesis statement .

– Use transition words and phrases to connect your paragraphs and make your essay flow smoothly.

– End your essay with a conclusion that summarizes the key points of your reflection and provides closure for the reader.

– Consider using subheadings to organize your essay and make it more structured and easy to read.

By following these tips, you can create a clear and well-structured reflective essay that effectively communicates your personal experiences and reflections. Remember to use specific examples and details to support your reflection, and to keep your focus on the main topic and thesis statement of your essay .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is a reflective essay.

A reflective essay is a type of writing that allows you to reflect on your personal experiences, thoughts, and feelings. It involves exploring your own thoughts and feelings about an experience, and reflecting on what you learned from it.

2. What are the elements of a reflective essay?

The essential elements of a reflective essay include personal reflection, description of the experience, analysis of the experience, evaluation of the experience, identification of key learning, and planning for future action.

3. How do I choose a topic for a reflective essay?

To choose a topic for a reflective essay, think about a personal experience or event that had a significant impact on your personal or professional growth. You may also consider professional experiences, academic experiences, cultural experiences, or social issues that have impacted you personally.

Reflective writing is a powerful tool for personal and professional development. By exploring your own thoughts and feelings about an experience, you can gain insights into your personal and professional growth and identify areas for further development. To write an effective reflective essay, it is important to follow a clear structure, use specific examples and details to support your reflection, and stay focused on the main topic and thesis statement of your essay . By following these tips and guidelines, you can become a skilled reflective writer and use this tool to improve your personal and professional growth.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Have a subject expert write for you now, have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, popular topics.

Business Analysis Examples Essay Topics and Ideas How to Guides Literature Analysis Nursing

- Nursing Solutions

- Study Guides

- Cookie Policy

- Free College Essay Examples

- Privacy Policy

- Research Paper Writing Service

- Research Proposal Writing Services

- Writing Service

- Discounts / Offers

Study Hub:

- Studying Blog

- Topic Ideas

- Business Studying

- Nursing Studying

- Literature and English Studying

Writing Tools

- Citation Generator

- Topic Generator

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Maker

- Research Title Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Summarizing Tool

- Terms and Conditions

- Confidentiality Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Refund and Revision Policy

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Contact Us:

📧 [email protected]

📞 +1 (315)-961-6813

2012-2024 © studyinghq.com. All rights reserved

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

U Should B Writing

An OER for students.

Reflection Essays

Your professor has probably assigned a reflection essay to include with your portfolio. This essay serves as a statement that discusses how you’ve developed as a writer over the past semester, as well as what revisions you’ve made to your major assignments. Specifically, you should describe what changes your instructors and peers have recommended and what steps you’ve taken to incorporate their feedback into your final drafts.

The reflection statement can take several forms, and it may range in length. A typical reflection runs 1,000-1,200 words.

Some instructors may ask you to include a short reflection statement for each major paper, or they may want you to compose a single essay that reflects on your work over the course of the semester. Either way, the reflection component should follow these criteria:

You should reference key concepts from the course objectives and WPA Outcomes Statement 3.0 . You don’t need to specifically mention the WPA statement by name, but you need to demonstrate a vocabulary for discussing writing. For example:

- rhetorical knowledge (audience, thesis statements, claims, evidence)

- genre awareness (academic essays, newspaper articles, documentaries, PSAs, etc)

- conventions (style, grammar, formatting, citation)

- process (brainstorming, outlining, revision, peer review)

- critical thinking (inquiry, debate, analysis, multiple perspectives)

- information literacy (source types and evaluation, library database use, search tools)

- electronic literacy (website construction, use of hyperlinks, Adobe Programs, etc)

- modality (visual, textual, aural)

Write a general statement about what major improvements and developments you’ve undergone as a writer. Try to be specific and genuine. For example, you may have learned to start your drafts earlier, or developed the ability to break down the writing process into smaller units and keep an organized writing schedule. You may have also learned to write for a wider range of genres. If so, lead with these major points about your growth as a writer.

Support these assertions with concrete examples from class discussions, or your own experiences writing in and outside of class. Pinpoint key “turning” points tied to major writing assignments or readings that influenced your approach or perceptions about writing.

You may want to describe any misconceptions or attitudes toward writing that you held at the beginning of the semester. How did they change? Why? What is your new attitude toward these aspects of writing?

Provide clear statements about how you revised your papers based on feedback from peers and instructors. You should also describe any Writing Center visits, or other activities that helped you draft and revise your papers.

Give specific examples of how you revised per instructor and peer feedback, with evidence from your own papers in the form of direct and indirect citations.

Summarize the feedback you received from your instructor and your peers in detail. You can even quote from their comments to provide a specific account of their reaction.

Focus your discussion on global or higher order revisions first, then discuss any changes you made regarding formatting and sentence-level editing.

You can integrate excerpts from your papers to show “before” and “after” portraits of important passages you revised.

Describe what specific additions or extra research you did after receiving feedback on your first draft.

Reflect on research skills (broadly defined) that you developed and deployed during at least one assignment. Familiarity with library search tools plays a key role here.

Explain and justify your revisions and composing choices, including any feedback you did not understand or agree with.

Describe the process of composing the portfolio itself, including design choices regarding layout, file arrangement, font, color, use of hyperlinks, and choice of platform (Google Sites, Weebly, Wix, WordPress, etc).

Tips & Advice

You don’t need to provide in-depth discussion of every single writing project you completed. In fact, doing that would probably result in a much longer reflection.

Spend some time brainstorming and freewriting about your projects. You may feel overwhelmed or stuck at first. The earlier you start reflecting, the more material you’ll have for the essay.

Open an electronic document on MS Word or Google Docs and simply type thoughts and feelings that occur to you, which you can develop later.

Your instructor may have encouraged or required you to keep a journal or blog on your writing throughout the semester. This would be an excellent source to re-read and draw from when outlining your reflection essay.

Focus on 1-2 key assignments where you think you grew the most as a writer and developed new abilities or outlooks.

Do your best to avoid cliches and platitudes. At first, you may feel compelled to spend some time praising the course or the instructor. While that may be true, a reflection essay should focus on your own intellectual development.

A List of Reflection Questions

- How much did you know about writing at the beginning of the semester?

- How much did you know about a specific topic before you researched it for one of the assignments?

- What process did you go through to finish this draft?

- How did this writing assignment differ from others you’ve done in the past?

- What problems did you encounter while working on this draft? How did you solve them?

- What resources did you draw on while working on this draft? Were they helpful?

- How do you feel about this piece of writing, or your writing in general?

- What aspects of your writing did you struggle with the most–brainstorming, research, revision, proofread, procrastination, block, etc?

- Wha t challenges did you overcome as a writer on a given assignment, or throughout the semester? What challenges remain for you to address next semester?

- What standards do you hold for yourself and your own writing? Do you feel like you meet these standards?

- How did you define good writing at the beginning of the semester? Has that changed since then?

- When you compare first and final drafts of your writing, what are the changes that stand out most to you?

- What aspects of the writing process work well for you? Which don’t? What did you learn about writing, research, and revision from other people in the class? Did they share tips or strategies during peer review workshops?

- What did your peers say about your first drafts?

- What did your instructor say about your first drafts?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Reflective Essay

- 3-minute read

- 29th August 2018

If you think that a “reflective essay” is a college paper written on a mirror, this post is for you. That’s because we’re here to explain exactly what a reflective essay is and how to write one. And we can tell you from the outset that no mirrors are required to follow our advice.

What Is Reflective Writing?

The kind of “reflection” we’re talking about here is personal. It involves considering your own situation and analyzing it so you can learn from your experiences. To do this, you need to describe what happened, how you felt about it, and what you might be able to learn from it for the future.

This makes reflective writing a useful part of courses that involve work-based learning . For instance, a student nurse might be asked to write a reflective essay about a placement.

When writing a reflective essay, moreover, you may have to forget the rule about not using pronouns like “I” or “we” in academic writing. In reflective writing, using the first person is essential!

The Reflective Cycle

There are many approaches to reflective learning, but one of the most popular is Gibb’s Reflective Cycle . This was developed by Professor Graham Gibbs and can be applied to a huge range of situations. In all cases, though, it involves the following steps:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

- Description – You will need to describe your experiences in detail. This includes what happened, where and when it happened, who else was involved, and what you did.

- Feelings – How you felt before, during, and after the experience you describe.

- Evaluation and Analysis – Think about what went well and what could be improved upon based on your experience. Try to refer to ideas you’ve learned in class while thinking about this.

- Conclusions – Final thoughts on what you’ve learned from the experience.

- Action – How you will put what you’ve learned into practice.

If your reflective essay addresses the steps above, you are on the right track!

Structuring a Reflective Essay

While reflective essays vary depending upon topic and subject area, most share a basic overall structure. Unless you are told otherwise, then, your essay should include the following:

- Introduction – A brief outline of what your essay is about.

- Main Body – The main part of your essay will be a description of what happened and how it made you feel . This is also where you will evaluate and analyze your experiences, either as part of the description or as a separate section in the essay.

- Conclusion – The conclusion of your essay should sum up what you have learned from reflecting on your experiences and what you would do differently in the future.

- Reference List – If you have cited any sources in your essay, make sure to list them with full bibliographic information at the end of the document.

Finally, once you’ve written your essay, don’t forget to get it checked for spelling and grammar errors!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Skip To Main Content

- Report an Accessibility Barrier

- Accessibility

Revision Strategies

Revision Strategies

Why is Revising Important? What is Revision?

Now what? You’ve done your research, written your paper, but the big question now is: what do you do next? Answer: Revise. Although it can be a daunting word, revision is the time during your writing when you can carefully go back over your paper to fix any mistakes that may confuse or trip up your reader. Revision is a time to smooth out the flow of your thoughts through transitioning between your paragraphs, to make sure that each of your paragraphs are balanced with supporting evidence and your own original thought, and to look at sentence level edits like grammar and sentence flow in the final stages. While most see this as a time to make sure commas are in the right place, revision is for looking at the big picture just as much as the fine details and below are some tips and tricks to get you started!

How do I Go About it?

One of the first steps in the revision process is making sure you set aside enough time to properly edit your paper. If you finish a paper twenty minutes before it’s due, then there is little you can do to revise it. Although sometimes it’s hard to find time to write and revise amidst your busy schedule, I promise it’s worth it!

Writing a paper a few days before it is due will allow you to take a step back and edit the big and small details without the pressure of a looming deadline. This will also give you time to consult writing tutors, your classmates, or your teacher if you find you need help during the process. The ratio of planned writing time to revision is usually along the lines of 70/30 or 80/20 depending on the type of writing assignment you have.

For example, if you are assigned an 8-page research paper, then you are more than likely going to spend 70% of your timing writing and 30% of your time revising since you will have more writing that needs revising before you turn it. This is versus if you are assigned a 1-page reflection essay that requires you to spend more time writing at 80% and only about 20% of your time revising since there is only so much writing that can fit onto one page.

Let’s face it, many of us get bored while writing. Taking a brief moment to step back after writing your first draft to do other things will allow you to return to the assignment later with fresh eyes in order to spot any errors that you may have missed before.

The Big Picture

When thinking about revision, our minds often jump to making sentence-level edits first. However, revision is much more than that!

The first step in any revision process is taking a step back to look at the big picture. Does your paper have an introduction with a thesis statement? Does it have complete and coherent body paragraphs? What about a conclusion that sums up the main focus of your paper for the reader one last time? For a better understanding of how a typical essay is organized, check out “How is it Organized?” on our Reading Strategies page.

Keep in mind that the Big Picture also includes any rubrics or assignment guidelines that your teacher may have given you. It’s important to note requirements like word/paper length during writing and revision as you don’t want to have a complete paper only to realize at the end that you missed the word count or forgot to include three scholarly sources. For more tips on how to keep rubrics and requirements in mind click here to jump to our section on assignment guidelines . Link to rubrics and assignments guidelines sections below.

Main Intent

Start with the main intent of your paper which is found in the ‘thesis statement.’ The thesis statement is included in the introduction paragraph and is typically found at the conclusion of the paragraph. It tells what the text will focus on and how the writer plans to achieve this. Do you state clearly and concisely what your paper will achieve and why and/or how? Do your body paragraphs support your thesis statement? Does your conclusion paragraph match your thesis statement? If you make sure that every part of your paper can be brought back to your thesis statement, then your paper will be more well-rounded and fluent.

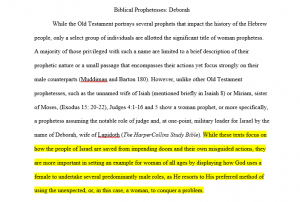

Note the thesis statement that is highlighted in yellow from an analysis paper on the biblical prophetess Deborah below.

This thesis statement tells what the body paragraphs will analyze: “these texts” (analysis being the how ). It also tells why : because “they are more important in setting an example for woman of all ages by displaying how God uses a female to undertake several predominantly male roles, as He resorts to His preferred method of using the unexpected, or, in this case, a woman, to conquer a problem.”

The following paragraphs in the paper will analyze the biblical texts that mention Deborah in order to show the reader that God uses women in male roles, an aspect that the writer found while analyzing the texts. We can assume that certain body paragraphs will inform us of the texts and others will attempt to prove the writer’s reasoning with supporting evidence from other sources.

Paragraphs

When reviewing your body paragraphs, you may want to consider why you are writing your paper. Are you trying to argue, persuade, or analyze? Does the structure of your paper enable you to do so? For example, a research paper is different from a persuasive paper since a persuasive paper is trying to persuade t he reader to see a topic as the writer does while a research paper focuses on objectively analyzing available sources of a topic to come to a conclusion, without regards to the writer’s personal opinion. So , the persuasive paper will have paragraphs that inform the reader of a topic, but also paragraphs that attempt to prove to the reader why their stance is the best stance on the topic.

Topic Sentences tell the intent and focus of a paragraph. Most of the time they are original thought or observation. They can sometimes be used to attract the reader’s attention to a certain issue or point by giving a preview of what the paragraph is about which propels them to keep reading. Topic sentences are typically found at the beginning and ending of a paragraph to introduce and then sum up the points mentioned within the paragraph.

For example, if you were to write a topic sentence for a paragraph in the aforementioned Deborah essay stating that it is hard to properly analyze the biblical texts because women prophets, especially Deborah, are sadly not as studied as male prophets, a poor intro topic sentence for paragraph might be:

“Many people find it difficult to study the texts with Deborah in them because there is little research done on female prophets.”

While we are able to see that this paragraph will focus on the aspect of female prophets and that it is hard to study the texts with Deborah in them because there is little research on female prophets, there is no transition from the last paragraph to connect the thoughts of the paper nor is the sentence specific about who the “many people” are.

Whereas a more defined topic sentence with proper transitioning between paragraphs and one that introduces the full intent of the paragraph might be:

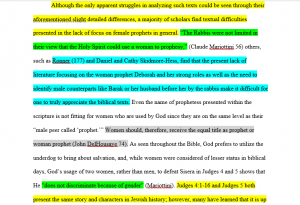

“Although the only apparent struggles in analyzing such texts could be seen through their aforementioned slight detailed differences, a majority of scholars find textual difficulties presented in the lack of focus on female prophets in general.”

This topic sentence, which is the first sentence of the paragraph, transitions the reader from the paragraph before it by using a good transition phrase starting with the word “Although.” “Although” is generally used to compare and contrast ideas, and ere it is used to do just that.

By acknowledging the intent of the paragraph before it as well as previous research in general, this makes the previous information relevant to this paragraph since the content of this paragraph will be slightly contrasting since the writer is stating that this is actually the biggest issue in analysis not the other ones previously stated even though they are important too.

The second half of the sentence also serves to tell the intent of the paragraph. Here as the reader, we know that we are going to be presented with sources that support the idea that there is a lack of focus on female prophets in general which makes it hard to study them.

Some questions to ask might be:

- Do your paragraphs have a clear topic sentence? Do your topic sentences tell the main intent of that specific paragraph? Is it one clear point? If not, you may want to pick the point that best describes the content in your paragraph.

- Do your paragraphs transition smoothly? What draws your attention during reading? Is it to the things that you want to draw attention to?

Examples/Evidence provide a foundation atop which you can build your paper on. Teachers will typically give a minimum or maximum number of sources that you can have in your paper within the rubric or assignment guidelines. Always remember to pick sources that will best support the main intent of your paper and the assignment’s requirements. However, try to keep an open mind when you’re choosing your sources. When you’re writing a paper, you want sources that will support your argument, but, if you’re struggling to find any, try reconsidering your initial idea . It’s okay to be wrong, and it’s okay to revise and change; that’s all part of the process of learning. What you want to avoid is pulling bits and pieces from sources that don’t agree with your argument. This is called ‘cherry-picking’, and it can actually make writing a paper harder, since you have to construct writing that fits your sources, instead of finding sources that fit your writing. Some questions to ask would be:

- Do your paragraphs have enough examples, quotes, paraphrasing, and summary from other sources to provide support for the main topic of each paragraph? Do you have more quotes than paraphrasing or vice vera?

- Sometimes it may work better to have a quote rather than summary; however, keep in mind that well-rounded papers typically have an even amount of all in order to keep the audience’s attention and show that you know what you are talking about.

- Do you explain why you included that examples, quotes, paraphrasing, or summary with a follow-up sentence on how it supports your argument or research? Does your inclusion of this example lead into the idea of your next sentence?

- Sometimes having too many sources can drown out your own thought, so be sure to keep an eye out to see if your paragraphs are balanced with original thought and other sources.

One way to check if your paragraphs are complete is by putting them to the PREP test:

P oint: Does your paragraph have an introduction topic sentence? What is this paragraph going to be about?

R eason: Does your paragraph give reasoning for your topic sentence? Why do you think this way, or why is your point valid?

E xample: Does your paragraph provide an example/ evidence from supporting sources that backup your reasoning. Do you provide quotes, and/or paraphrasing, and/or summary from other sources?

P oint: Does your paragraph have a conclusion topic sentence? Does it sum up/(re)state the focus of the paragraph without being repetitive? Does it provide a smooth transition into your next paragraph?

Structural Edits

Structural Edits are just what the name hints at: they involve the overall structure, or layout, of your paper. When doing structural edits, you are looking at how your paragraphs are arranged and how the sentences within them are arranged.

Are your paragraphs arranged in a way that promotes the best flow of thoughts and transitions between them? Are your sentences arranged in a way that enables the reader to follow your thoughts while reading? Or are your paragraphs choppy and jump from idea to idea without any rhyme or reason?

Here are a few different ways of how to go about Structural Edits:

The Outline Method

As you reread your paper, create an outline as you go. Do not look at your original outline but follow the flow of your written paper.

Note where your introduction and thesis are. What does your introduction introduce and how? Note where each of your paragraphs are, what the focus of each paragraph is, what supporting and/or challenging evidence does it provide, and where their topic sentences are. Finally, note where your conclusion is. Does it sum up everything in your paper well?

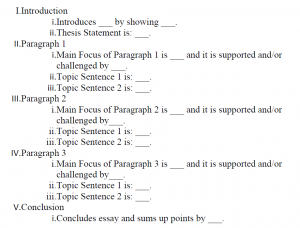

Once you finish, you should have an outline that looks somewhat like this:

(Access a downloadable copy of the Outline Method here.)

Now pull your original outline back out. Does your current outline and original outline match in the same places? If not, look and see how and why. Are your paragraphs in reverse order? Do you have holes in your new outline where you haven’t supported a point in one of your paragraphs? Are your topic sentences in the middle of one of your paragraphs instead of at the beginning or end? Does this work for that particular paragraph (sometimes it can depending on the length and focus of the paragraph)?

Please note that outlines are meant to be flexible, so if your current outline doesn’t 100% match the original outline THIS IS OKAY because some changes are good! As you write and revise, you are usually able to feel and see if it makes more sense to put one paragraph in a different place or to use one source but not the other. Most of the time you know when something doesn’t look or sound right as you’re writing or editing. Just make sure that your new outline matches the main points you are trying to focus on in the original outline. Trust your instincts and, if you are not sure, consult a writing tutor, your classmates, or your teacher for advice on how to revise your paper.

One last thing to remember is the above outline is an outline for a basic essay. If you are doing scientific research or writing a business proposal, your outline is bound to look different. However, the same basic principles still apply. Read your writing, create an outline of your writing from your reading, and consult and compare your original and current outline to see if you need to change anything.

The PowerPoint Method

If you are a visual leaner, one way to help you visualize your paper is by copying and pasting your paragraphs onto PowerPoint slides. Put one paragraph on a slide from beginning to end (ex: Introduction is on the first slide and Conclusion is on the last slide). Now read your paper both in your head or out loud if that helps. Does your paper flow well in the order that it is in? Try moving some of the slides around. Does it read better if Paragraph 2 is in front of Paragraph 1? While you won’t always need to rearrange your paragraphs, if you are finding that your paper is a little hard to read or choppy, using the PowerPoint method can help you see if it is the layout that is affecting your paper’s flow.

Sentences

Note that you could also use the same method when looking at the sentences in one of your paragraphs if it harder to read. Create a PowerPoint and try putting one sentence on each slide. Now seeing if moving some slides around in a different order helps the paragraph to be read better or be understood more easily. Do you find that you need an example to backup up one of your own statements in the paragraph? Do sentences 4 and 5 need to be rearranged to make everything clearer? Do you need to delete a sentence in order for everything to be connected better?

The Paragraph-Cutting Method

If you’re a hands-on learner this might be just the thing for you!

Paragraph cutting is much like the PowerPoint Method. If you’re not comfortable with PowerPoint or don’t have the time, print your paper out and lay it in front of you. With scissors, cut the paragraphs out and line them up top to bottom from introduction to conclusion and start reading.

Just like the PowerPoint method, you can rearrange the paragraphs to see what layout best fits your paper and intent. You can also use this method on individual paragraphs by cutting up the sentences and rearranging them as noted above.

During this time, you might realize that a sentence you have in Paragraph 1 might actually fit better in Paragraph 3, so you can physically cut it out and move it to the other paragraph. Once you are done take a picture of your finished structure just in case you forget your edits later, and then transfer your edits into your actual paper.

The Highlighting Method

The Highlighting Method is a simple way to check the structure of your paper and assess what you do or don’t have in your paper as well. With at least 4 different colored highlighters (or more depending on the type of paper you’re writing or what your rubric asks you to include) highlight the different elements of your paper. Maybe you want your thesis and topic sentences to be highlighted in blue and your supporting evidence to be highlighted in orange. The Highlighting Method gives you a chance to see the placement and type of sentences you have in each paragraph by color-coordinating. This not only helps you to assess your paragraphs but also how much or how little you have in each paragraph.

Note in the example of the Highlighter Method above:

- Topic sentences (which are original thought or observation) are highlighted in yellow.

- Quotes are highlighted in green.

- Summary is highlighted in blue.

- Paraphrasing is highlighted in gray.

- Anything that is not highlighted is original thought from the writer.

The end result: This method allows us to see that this paragraph is balanced with original thought as well as a variety of sources and ways in which the writer was able incorporate them into her paragraph.

Rubrics and Assignment Guidelines

Teachers typically give a rubric or assignment guideline when assigning a paper so make sure to consult it when you start the revision process to remind yourself what you need to include in your paper. They are extremely helpful in making sure that you have all the big bases covered in your writing since they include what the teacher expects to find when reading your paper, such as word length, formatting, number and type of sources, and how clear your points are.

It might be helpful for you to print out a copy of the rubric or assignment guideline for yourself and check off if you meet each of paper’s requirements when revising. If you find that you have the box for word length checked off but don’t have enough sources to meet the minimum for the source requirement, this gives you a chance to find additional sources and incorporate them into your paper before the deadline.

Rubrics and assignment guidelines can be your best friends when you’re revising! Don’t be afraid of using them to your advantage during the revision process!

Sentence Level Edits While it’s essential to make sure that there are no issues with the overall structure of your paper, you should also look at some of the smaller problems. You can go about tackling some of the sentence-level edits by proofreading your paper.

Proofreading Proofreading is usually the final step when it comes to revising. This is when you read over your paper specifically to look for any mistakes involving things such as spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Even though revising involves more than just checking your grammar, it’s still important to make sure that your paper is grammatically correct. Having grammatical errors in your paper can not only cause you to lose points on your assignment, but it can also cause your readers to become confused and misunderstand what you’re trying to say. Before you begin this process, you should doublecheck to make sure that you’ve handled any larger issues first, such as problems with the organization, style or formatting issues, etc. If everything’s correct, then you’re ready to take a look at the grammatical errors. While proofreading may seem like a tedious process, there are a few strategies that may help you.

Proofreading Strategies

Set your work to the side for a little while. After you’ve spent some time writing and revising a paper, you become very familiar with it. You know what it says, or what it’s supposed to say. However, this familiarity can actually be a hindrance when it comes to trying to proofread. So, after you’ve finished with your major revisions, consider setting your paper to the side for a bit, maybe overnight, or even just for a few hours if you’re short on time. That way, when you come back to it, you’ll have a fresh perspective to begin proofreading with.

Don’t just use Spellcheck. Spellcheck, or any program like it, is a very useful tool when it comes to proofreading. You should always make sure to use it before turning in an assignment, as it can catch errors that you might not have noticed. However, you should not rely on it. There are certain problems that it can’t catch, or that it may miss, so you should look back over your paper after using Spellcheck on it.

Print out a hard copy. Printing out a hard copy of your paper has some of the same benefits as setting it aside for a few days. By the time you’ve reached the proofreading stage of revision, you’ll have already become very familiar with your paper, and you’ll have become used to seeing it on a screen. When you print your paper out, you’ll be seeing it in a new format, which can make it easier to spot errors. Also, having a hard copy of your paper gives you the opportunity to mark-up a physical copy of your work.

Read your work out loud. Reading your work out loud can help you find grammatical errors, but it’s mainly useful for making sure that your sentences flow together and don’t sound awkward. Something that looks good on paper may actually end up sounding disjointed. This is a great way to ensure that your writing is cohesive. Reading aloud in front of a friend or family member can also be helpful for identifying these types of errors. They may be able to catch things that you may not notice.

Look for one type of error at a time. Proofreading may seem like a daunting task, as it encompasses so many things. A way to make it less intimidating can be that you only focus on looking for one type of error at a time. For example, on your first read-through, you look for any spelling errors. Then, on your second read-through, you look for any comma errors. This can help to make the proofreading process a little more manageable.

Ask another person to review it. Once you’re finished proofreading your paper, it can still be helpful to have another set of eyes look over it. Like with setting your work aside, or printing out a hard copy, having a fresh perspective look over the paper can be helpful. You can ask a friend or family member to read your work, or you can always make an appointment with a consultant at the Writing Center to go over your paper. If you’d like to set up an appointment with a consultant, click here .

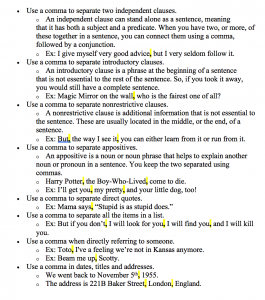

Many people have trouble knowing when and where to use a comma in their sentences. This can lead to confusion in their readers, because, depending on where a comma is placed, it can change the meaning of the sentence completely. Below are a few general rules that can help you check and make sure that your paper uses commas correctly.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of proper comma use.

Subject Verb Agreement

Another common mistake that people make while writing a paper is that, in their sentences, their subjects and verbs don’t agree. Subjects and verbs agree when they are both singular or plural, and in the same “person” (first person, third person, etc.). An example of subject-verb agreement would be: “I am” or “he is”, while an example of subject-verb disagreement would be: “He am” or “I is”.

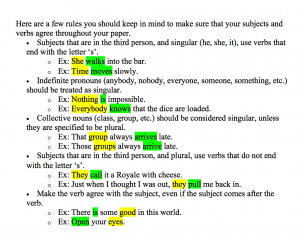

Here are a few rules you should keep in mind to make sure that your subjects and verbs agree throughout your paper.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of subject-verb agreement.

Active and Passive Voice

While you’re working on your paper, you should always make sure to keep your writing in the active voice, and not the passive voice. The difference between the two is that in the active voice, the subject of your sentence is performing the action, while in the passive voice, the subject is receiving the action. That may sound confusing, so here’s an example to show you what they both look like.

Active Voice Example: The hero saved the day.

Passive Voice Example: The day was saved by the hero.

In the first example, the subject of the sentence, the hero, is performing the verb. He is actively saving the day. However, in the second example, the action already happened. It’s in the past; the day was saved.

In your writing, you want to avoid phrases that sound like the second example. The active voice is typically clearer, which makes it easier for your readers to understand what it is that you’re trying to say.

While you’re editing your writing, if you come across a sentence that includes a “by the…” phrase, that sentence is probably written in the passive voice. You can fix it by rearranging some of your words.

For example: The knight was kidnapped by the dragon .

You see we have a “by the” phrase. That means that this sentence is written in the passive voice, so, what we need to do is reorganize. Who is actually doing something in this sentence? The dragon, he is actively kidnapping the knight. The knight is being useless and doing nothing, so why should he be the star of the sentence? He shouldn’t be; the dragon should be the subject instead. So, he and the knight switch places. If the dragon is the new subject, then we need to update our verb as well.

So, our new sentence would be: The dragon kidnapped the knight.

This sentence is written in the active voice, because the subject of the sentence, the dragon, is the one who is doing something.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of how to change passive voice sentences into active voice.

Questions to Keep You on Track

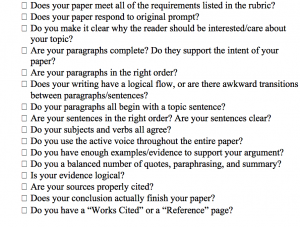

As you’re revising your paper, feel free to use the questions below to help you through the revision process.

Print out your own checklist here.

References

Academic Guides. (n.d.). Writing a Paper: Proofreading . https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/writingprocess/proofreading .

Hobart and William Smith Colleges. (n.d.). Academics: Revision Strategies . https://www.hws.edu/academics/ctl/writes_revision.aspx .

Lumen. (n.d.). Guide to Writing . https://courses.lumenlearning.com/styleguide/chapter/subject-verb-agreement/ .

Purdue Writing Lab. (n.d.). Changing Passive to Active Voice // Purdue Writing Lab . Purdue Writing Lab. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/active_and_passive_voice/changing_passive_to_active_voice.html .

Student Success. (n.d.). Commas (Eight Basic Uses) . https://www.iue.edu/student-success/coursework/commas.html .

The Writing Center. (n.d.). Subject-Verb Agreement . https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/subject-verb-agreement .

Reflective Writing and the Revision Process: What Were You Thinking?

|

| Giles, Sandra L. “Reflective Writing and the Revision Process: What Were You Thinking?” , vol. 1, 2010, pp. 191–204. |

|

| In Sandra Giles, “Reflective Writing and the Revision Process: What Were You Thinking?”, she explains that reflective writing is an activity that asks to think about your own thinking. Giles explains in her essay that reflective writing helps you in the revision aspect of writing an essay. She mentions a process called “Letter to the Reader”, in this process students write to their readers explaining their purpose, how they want the effect their readers, describe their process and talk about their peer evaluations. This process allows you to see where you have errors and what needs to be fixed within your essay. |

|

| No new terms |

|

| Moving forward I will be able to use this process of reflective writing to help polish my writing pieces and make sure there no problems or mistakes. |

|

| How does reflective writing help in the revision process? |

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Readings on Writing

Reflective Writing and the Revision Process: What Were You Thinking?

Sandra giles, chapter description.

This essay explains to students that reflective writing involves their thinking about their own thinking. They may be asked to reflect about their audience and purpose for a piece of writing. They may write about their invention, drafting, revision, and editing processes. They may self-assess or evaluate their writing, learning, and development as writers. These activities help cement learning. They also help writers gain more insight into and control over composing and revising processes by helping them gain critical distance and by providing a mechanism for them to do the re-thinking and re-seeing that effective revision requires. The article gives examples of student reflective writing, explains how they function in a student’s learning, and gives scholarly support for why these kinds of activities are effective.

Alternate Downloads:

You may also download this chapter from Parlor Press or WAC Clearinghouse.

Writing Spaces is published in partnership with Parlor Press and WAC Clearinghouse .

36 Reflective Writing and the Revision Process: What Were You Thinking?

Sandra L. Giles

“Reflection” and “reflective writing” are umbrella terms that refer to any activity that asks you to think about your own thinking. As composition scholars Kathleen Blake Yancey and Jane Bowman Smith explain, reflection records a “student’s process of thinking about what she or he is doing while in the process of that doing” (170). In a writing class, you may be asked to think about your writing processes in general or in relation to a particular essay, to think about your intentions regarding rhetorical elements such as audience and purpose, or to think about your choices regarding development strategies such as comparison-contrast, exemplification, or definition. You may be asked to describe your decisions regarding language features such as word choice, sentence rhythm, and so on. You may be asked to evaluate or assess your piece of writing or your development as a writer in general. Your instructor may also ask you to perform these kinds of activities at various points in your process of working on a project, or at the end of the semester.

A Writer’s Experience

The first time I had to perform reflective writing myself was in the summer of 2002. And it did feel like a performance, at first. I was a doctoral student in Wendy Bishop’s Life Writing class at Florida State University, and it was the first class I had ever taken where we English majors actually practiced what we preached; which is to say, we actually put ourselves through the various elements of process writing. Bishop led us through invention exercises, revision exercises, language activities, and yes, reflective writings. For each essay, we had to write what she called a “process note” in which we explained our processes of working on the essay, as well as our thought processes in developing the ideas. We also discussed what we might want to do with (or to) the essay in the future, beyond the class. At the end of the semester, we composed a self-evaluative cover letter for our portfolio in which we discussed each of our essays from the semester and recorded our learning and insights about writing and about the genre of nonfiction.

My first process note for the class was a misguided attempt at good-student-gives-the-teacher-what-she-wants. Our assignment had been to attend an event in town and write about it. I had seen an email announcement about a medium visiting from England who would perform a “reading” at the Unity Church in town. So I went and took notes. And wrote two consecutive drafts. After peer workshop, a third. And then I had to write the process note, the likes of which I had never done before. It felt awkward, senseless. Worse than writing a scholarship application or some other mundane writing task. Like a waste of time, and like it wasn’t real writing at all. But it was required.

So, hoop-jumper that I was, I wrote the following: “This will eventually be part of a longer piece that will explore the Foundation for Spiritual Knowledge in Tallahassee, Florida, which is a group of local people in training to be mediums and spirituals healers. These two goals are intertwined.” Yeah, right. Nice and fancy. Did I really intend to write a book-length study on those folks? I thought my professor would like the idea, though, so I put it in my note. Plus, my peer reviewers had asked for a longer, deeper piece. That statement would show I was being responsive to their feedback, even though I didn’t agree with it. The peer reviewers had also wanted me to put myself into the essay more, to do more with first-person point of view rather than just writing a reporter-style observation piece. I still disagree with them, but what I should have done in the original process note was go into why: my own search for spirituality and belief could not be handled in a brief essay. I wanted the piece to be about the medium herself, and mediumship in general, and the public’s reaction, and why a group of snarky teenagers thought they could be disruptive the whole time and come off as superior. I did a better job later—more honest and thoughtful and revealing about my intentions for the piece—in the self-evaluation for the portfolio. That’s because, as the semester progressed and I continued to have to write those darned process notes, I dropped the attitude. In a conference about my writing, Bishop responded to my note by asking questions focused entirely on helping me refine my intentions for the piece, and I realized my task wasn’t to please or try to dazzle her. I stopped worrying about how awkward the reflection was, stopped worrying about how to please the teacher, and started actually reflecting and thinking. New habits and ways of thinking formed. And unexpectedly, all the hard decisions about revising for the next draft began to come more easily.

And something else clicked, too. Two and a half years previously, I had been teaching composition at a small two-year college. Composition scholar Peggy O’Neill taught a workshop for us English teachers on an assignment she called the “Letter to the Reader.” That was my introduction to reflective writing as a teacher, though I hadn’t done any of it myself at that point. I thought, “Okay, the composition scholars say we should get our students to do this.” So I did, but it did not work very well with my students at the time. Here’s why: I didn’t come to understand what it could do for a writer, or how it would do it, until I had been through it myself.

After Bishop’s class, I became a convert. I began studying reflection, officially called metacognition, and began developing ways of using it in writing classes of all kinds, from composition to creative nonfiction to fiction writing. It works. Reflection helps you to develop your intentions (purpose), figure out your relation to your audience, uncover possible problems with your individual writing processes, set goals for revision, make decisions about language and style, and the list goes on. In a nutshell, it helps you develop more insight into and control over composing and revising processes. And according to scholars such as Chris M. Anson, developing this control is a feature that distinguishes stronger from weaker writers and active from passive learners (69–73).

My Letter to the Reader Assignment

Over recent years, I’ve developed my own version of the Letter to the Reader, based on O’Neill’s workshop and Bishop’s class assignments. For each essay, during a revising workshop, my students first draft their letters to the reader and then later, polish them to be turned in with the final draft. Letters are composed based on the following instructions:

This will be a sort of cover letter for your essay. It should be on a separate sheet of paper, typed, stapled to the top of the final draft. Date the letter and address it to “Dear Reader.” Then do the following in nicely developed, fat paragraphs: 1. Tell the reader what you intend for the essay to do for its readers. Describe its purpose(s) and the effect(s) you want it to have on the readers. Say who you think the readers are. • Describe your process of working on the essay. How did you narrow the assigned topic? What kind of planning did you do? What steps did you go through, what changes did you make along the way, what decisions did you face, and how did you make the decisions? • How did comments from your peers, in peer workshop, help you? How did any class activities on style, editing, etc., help you? 2. Remember to sign the letter. After you’ve drafted it, think about whether your letter and essay match up. Does the essay really do what your letter promises? If not, then use the draft of your letter as a revising tool to make a few more adjustments to your essay. Then, when the essay is polished and ready to hand in, polish the letter as well and hand them in together.

Following is a sample letter that shows how the act of answering these prompts can help you uncover issues in your essays that need to be addressed in further revision. This letter is a mock-up based on problems I’ve seen over the years. We discuss it thoroughly in my writing classes: