Decent work & economic growth

Rebuilding economies after covid-19: will countries recover.

[goal: 8] aims to promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full employment, and decent work for all. COVID-19 caused the deepest global recession in decades, reducing global GDP by 3.1 percent in 2020. Today only 5 percent of the world population live in a country that is on track to return to or surpass pre-COVID projections of economic output.

↓ Read the full story

The damage done

Global gdp growth, covid-19 took a heavy toll on the global economy in 2020, gdp growth (annual %).

Source: World Bank, Global Economic Prospects ([link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects NYGDPMKTPKDZ]). World Development Indicators ([link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG]).

The pandemic's impact across regions continues

Gdp growth rate, adjusted for inflation. post-2022 data is projected.

Source: World Bank, Global Economic Prospects June 2023 ([link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects NYGDPMKTPKDZ])

Global economic recovery remains elusive

Economic output, $4.7 trillion.

lower than expected in 2020

Global GDP has fallen behind pre-COVID projections

Level of gdp compared to pre-covid projections (value for 2019=100).

Source: [link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects World Bank Global Economic Prospects]

COVID-19 caused damage across regions

In 2023, [emphasis: 95 percent of people] live in countries with [emphasis: lower GDP growth] than forecast before the pandemic.

Only 23 countries out of 188 are on track to recover from COVID-19 impacts by 2023

Source: Global Economic Prospects ([link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects NYGDPMKTPKDZ]). World Development Indicators ([link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD NY.GDP.MKTP.KD])

Growth in India and Indonesia not on track to make up lost GDP

Source: Global Economic Prospects ([link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects NYGDPMKTPKDZ]). World Development Indicators ([link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD NY.GDP.MKTP.KD]).

China on lower growth trajectory

Some countries have made up lost ground, some countries have benefited from high commodity prices or natural resource discoveries, ukraine: a double impact, gdp in tourism-dependent economies.

lower than expected

Economies based on tourism took a large hit

Choose a country to explore impacts, covid-19’s impact on jobs, unemployment remains elevated compared with pre-covid levels, unemployment, total (% of total labor force).

Source: [link: https://ilostat.ilo.org/ ILOSTAT]

Women have higher rates of unemployment than men in most regions

Regional gap between the unemployment rate of men and women, will the recovery be shared.

In [emphasis: 60 percent] of countries with data, the bottom 40 percent of income grew faster from 2012 to 2017.

Countries differ in how well prosperity is shared

Source: [link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/brief/global-database-of-shared-prosperity World Bank Global Database of Shared Prosperity, 2012-17. 9th vintage].

Learn more about SDG 8

In the charts below you can find more facts about SDG {activeGoal} targets, which are not covered in this story. The data for these graphics is derived from official UN data sources.

SDG target 8.10

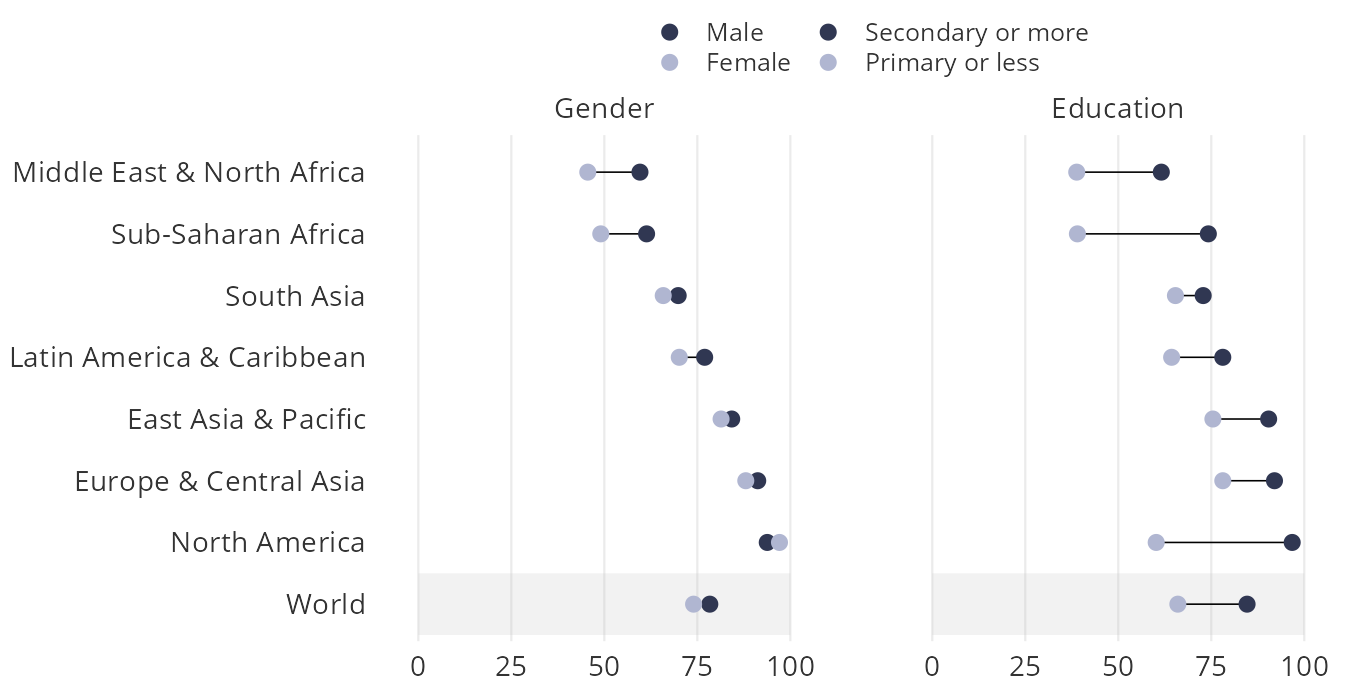

Financial account ownership is lower among women and those with less education.

Account ownership by gender and education, 2021 (% of population ages 15 and older).

Source: Global Findex Database. Retrieved from World Development Indicators ([link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FX.OWN.TOTL.MA.ZS FX.OWN.TOTL.MA.ZS], [link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FX.OWN.TOTL.FE.ZS FX.OWN.TOTL.FE.ZS], [link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FX.OWN.TOTL.PL.ZS FX.OWN.TOTL.PL.ZS], [link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FX.OWN.TOTL.SO.ZS FX.OWN.TOTL.SO.ZS]). DOWNLOAD

SDG target 8.6

In most countries, young women are less likely to participate in education, employment, or training.

Proportion of youth (aged 15-24 years) not in education, employment or training (neet).

* The figure only includes countries with at least one estimate for 2010-2019. When multiple estimates are available for the same country in the same decade, the latest value is used. Only data for eight high-income countries are available.

Source: International Labour Organization (ILO). Retrieved from World Development Indicators ([link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.NEET.MA.ZS SL.UEM.NEET.MA.ZS], [link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.NEET.FE.ZS SL.UEM.NEET.FE.ZS]). DOWNLOAD

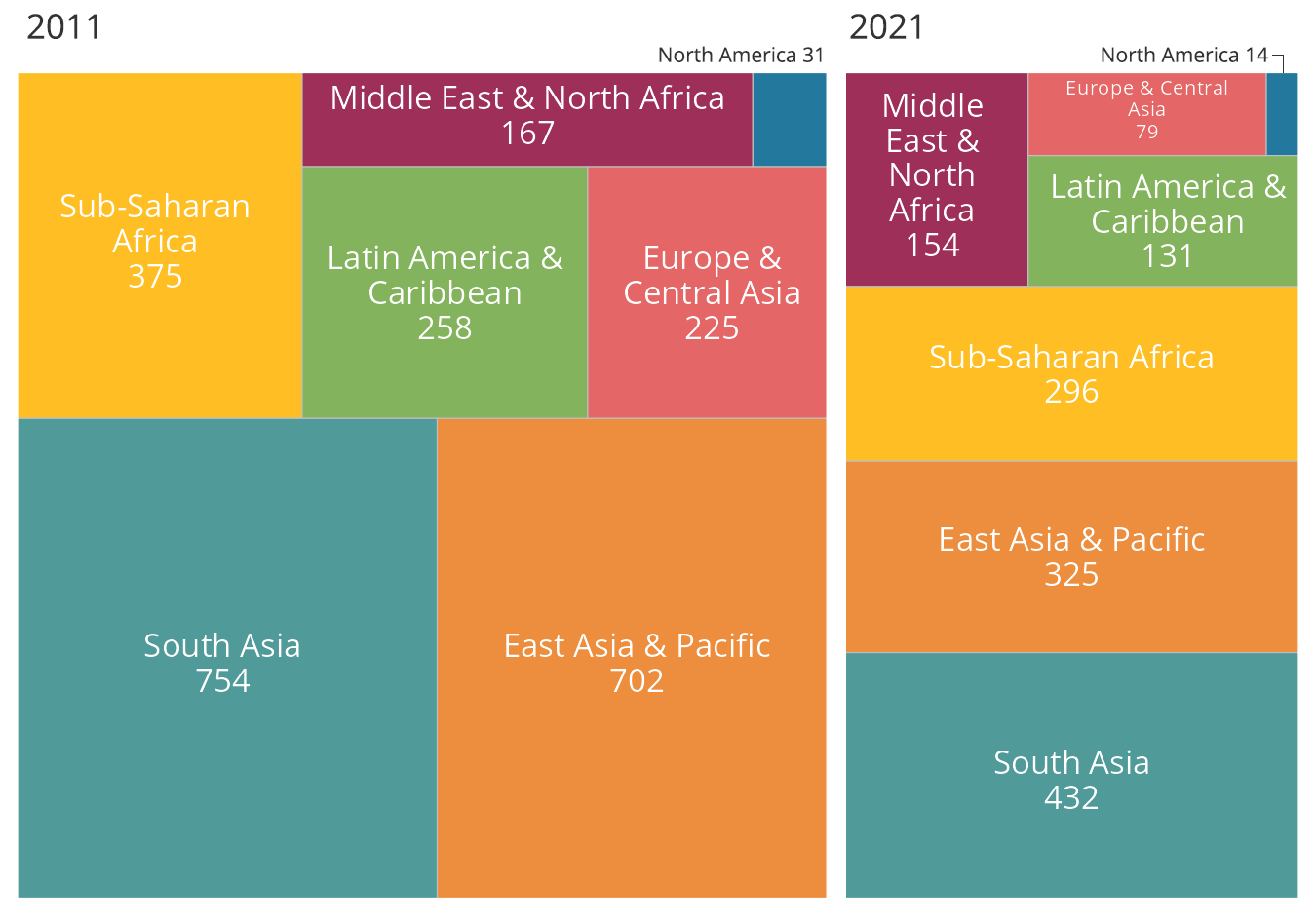

The unbanked population has shrunk from close to 2.5 billion in 2011 to around 1.2 billion in 2021

Adults with no account (%), 2011-2021.

Source: World Bank. [link: https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/ Global Findex Database] DOWNLOAD

- News, Stories & Speeches

- Get Involved

- Structure and leadership

- Committee of Permanent Representatives

- UN Environment Assembly

- Funding and partnerships

- Policies and strategies

- Evaluation Office

- Secretariats and Conventions

- Asia and the Pacific

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- New York Office

- North America

- Climate action

- Nature action

- Chemicals and pollution action

- Digital Transformations

- Disasters and conflicts

- Environment under review

- Environmental rights and governance

- Extractives

- Fresh Water

- Green economy

- Ocean, seas and coasts

- Resource efficiency

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Youth, education and environment

- Publications & data

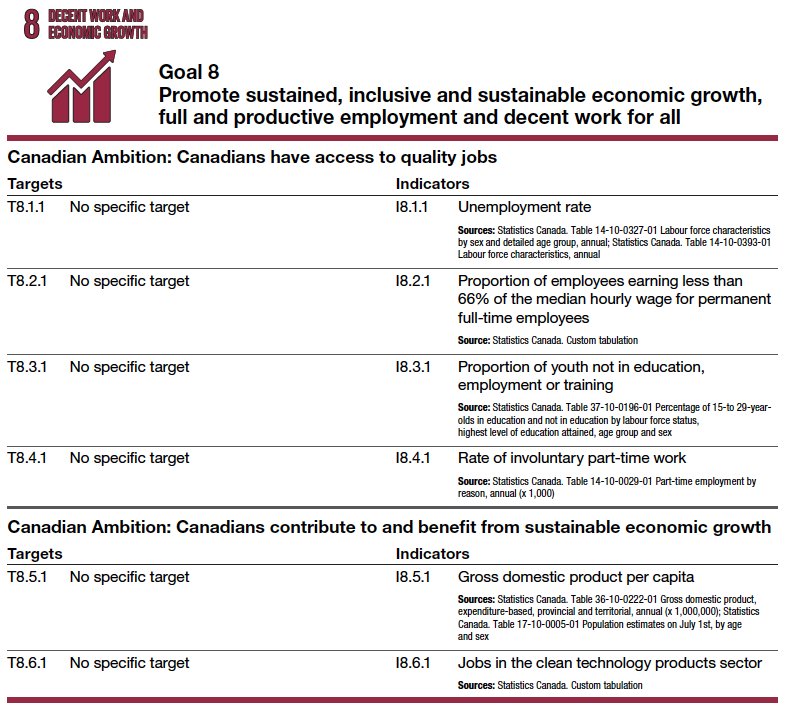

GOAL 8: Decent work and economic growth

Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all:

Preserving the environment is key to support sustainable economic growth as the natural environment plays an important role in supporting economic activities. It contributes directly, by providing resources and raw materials such as water, timber and minerals that are required as inputs for the production of goods and services; and indirectly, through services provided by ecosystems including carbon sequestration, water purification, managing flood risks, and nutrient cycling.

`Natural` disasters directly affect economic activities leading to very high economic losses throwing many households into poverty. Maintaining ecosystems and mitigating climate change can therefore have a great positive impact on countries` economic and employment sectors

Sustained and inclusive economic growth is a prerequisite for sustainable development, which can contribute to improved livelihoods for people around the world. Economic growth can lead to new and better employment opportunities and provide greater economic security for all. Moreover, rapid growth, especially among the least developed and developing countries, can help them reduce the wage gap relative to developed countries, thereby diminishing glaring inequalities between the rich and poor.

Indicators:

- 8.4.1 Material footprint, material footprint per capita and material footprint per GDP (Tier II*)

- 8.4.2 Domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP (Tier I)

* Agreed methodology only at global level. Not for country level monitoring.

- United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD)

- International Resource Panel

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)

- University of Vienna

- Vienna Institute of Social Ecology

- Nagoya University

Related Sustainable Development Goals

© 2024 UNEP Terms of Use Privacy Report Project Concern Report Scam Contact Us

- Development Economics

- Economic Growth

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- In book: Before the UN Sustainable Development Goals: A Historical Companion

- Publisher: Oxford University Press

- City University of New York - John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- F.H. Nekhwevha

- ENERG POLICY

- Int Rev Appl Econ

- Maria Prebble

- Shouvik Chakraborty

- Juliann Emmons Allison

- Kirin McCrory

- Stephanie Pinnington

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Partnerships

- What came before

- Integrated Social Protection

- SDG Financing

- Small Island Developing States

- Development Emergency

- Where we work

Annual Report 2023

- Publications

- About the goals

- Youth Corner

- A Time to Act

- Breakthrough Alliance

Goal 8 Decent work and economic growth

- Facts and figures

- Goal 8 targets

Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all

Over the past 25 years the number of workers living in extreme poverty has declined dramatically, despite the long-lasting impact of the economic crisis of 2008/2009. In developing countries, the middle class now makes up more than 34 percent of total employment – a number that has almost tripled between 1991 and 2015.

However, as the global economy continues to recover we are seeing slower growth, widening inequalities and employment that is not expanding fast enough to keep up with the growing labour force. According to the International Labour Organization, more than 204 million people are unemployed in 2015.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to encourage sustained economic growth by achieving higher levels of productivity and through technological innovation. Promoting policies that encourage entrepreneurship and job creation are key to this, as are effective measures to eradicate forced labour, slavery and human trafficking. With these targets in mind, the goal is to achieve full and productive employment, and decent work, for all women and men by 2030.

Decent work is one of 17 Global Goals that make up the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development . An integrated approach is crucial for progress across the multiple goals.

Learn more about the targets for Goal 8 .

- The global unemployment rate in 2017 was 5.6per cent, down from 6.4per cent in 2000.

- Globally, 61per cent of all workers were engaged in informal employment in 2016. Excluding the agricultural sector, 51per cent of all workers fell into this employment category.

- Men earn 12.5per cent more than women in 40 out of 45 countries with data.

- The global gender pay gap stands at 23 per cent globally and without decisive action, it will take another 68 years to achieve equal pay. Women’s labour force participation rate is 63 per cent while that of men is 94 per cent.

- Despite their increasing presence in public life, women continue to do 2.6 times the unpaid care and domestic work that men do.

- Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 per cent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries

- Achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation, including through a focus on high-value added and labour-intensive sectors

- Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services

- Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, with developed countries taking the lead

- By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

- By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training

- Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

- Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment

- By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

- Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance and financial services for all

- Increase Aid for Trade support for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, including through the Enhanced Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance to Least Developed Countries

- By 2020, develop and operationalize a global strategy for youth employment and implement the Global Jobs Pact of the International Labour Organization

International Labour Organization

UN Development Programme

Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System: Policy Innovations for a Green Economy

UN Global Compact

Economic and Social Commission for Asia & the Pacific

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

Economic and Social Commission for Africa

Economic and Social Commission for Europe

Economic and Social Commission for Latin America & the Caribbean

IMF – World Economic Outlook

UN Capital Development Fund

Asian Development Bank

Articles related to Goal 8

Strengthening the resilience of school communities in falcón, venezuela, uzbekistan’s invigorated social system: a powerful buffer to support the most vulnerable, launch ceremony of the project “sustainable pineapple value chain development” in suriname, pineapple potential written all over the sandy soil of suriname, mongolia’s top sdg governing body endorses the draft integrated national financing strategy, indigenous women take the lead to improve food security in their costa rican communities, social inclusion ensures equal opportunities in turkmenistan, human-centered social policies – the core of the un's "activate" programme, our programmes contributing to goal 8, an integrated and universal social protection linked to developmental social welfare services in south africa, strategic policy options for sdg financing, resilient caribbean, advancing innovative financing solutions in the eastern caribbean, early childhood and sustainable development: towards a comprehensive care system, financing the future - aligning budgeting, planning and mobilizing financing through an integrated national financing framework, building back equal through innovative financing for gender equality and women's empowerment, enhancing social protection for female tea garden workers and their families in sylhet division, bangladesh, harnessing blue economy finance for sids recovery and sustainable development, resilient belize, additional financing leveraged to accelerate sdg achievement, strengthening the architecture and the ecosystem for financing the sustainable development goals (sdgs) in burundi: a synergy of actions for integrated solutions, sustainable, integrated and inclusive finance framework for cabo verde, connecting blue economy actors: generating employment, supporting livelihoods and mobilizing resources, integrated national financing framework to catalyze blended finance for transformative csdg achievement, implementing the integrated national financing framework for cameroon to unlock, leverage and catalyze resources to accelerate sdg achievement for inclusive growth, roadmap for an integrated national financing framework in colombia, support for the development of an integrated national financing framework for the sdgs in cuba, integrated financing for sdgs acceleration and resilience in djibouti, communities of care in the dr, expanding the social protection system for young men and women in the informal economy, advancing the sdgs by improving livelihoods, social protection, human rights and resilience of vulnerable communities via economic diversification and digital transformation, transforming social protection for persons with disabilities in georgia, accelerating attainment of sdg in ghana, guinea national integrated financing and implementation strategy for sdg achievement, building resilience in guinea-bissau through a shock-responsive social protection system, a progressive pathway towards a universal social protection system in kenya to accelerate the achievement of the sdgs, transforming national dialogue for the development of an inclusive national sp system for lebanon, unlocking sustainable & structural investments for an inclusive & green development of madagascar, build malawi window: a specialized structured blended finance vehicle for agribusiness, roadmap for an inclusive sustainable development goals financing framework, contributing to establish an enabling environment to promote sustainable green and blue economy in mauritius and seychelles, closing gaps: making social protection work for women in mexico, rolling out an integrated approach to the sdg financing in mongolia, activate integrated social protection and employment to accelerate progress for young people in montenegro, strengthening namibia’s financing architecture for enhanced quality & scale of financing for sdgs, integrating policy and financing for accelerated progress on sdgs in uganda, towards a universal and holistic social protection floor for persons with disabilities and older persons in the state of palestine, good oceans, good business, improving the quality of life of indigenous peoples in the department of lékoumou through improved access to social protection programmes in the republic of congo, accelerating integrated policy interventions to promote social protection in rwanda, enhancing development finance and effectiveness in rwanda through integrated and innovative approaches for national priorities and the sdgs, strengthening resilience of pacific island states through universal social protection, sustainable financing for the 2030 agenda through viable inff in cook islands, niue and samoa, promoting local food value chains and equitable job opportunities through a sustainable agri-food industry in stp, toward a somali led transition to national social protection, the accelerator for agriculture and agroindustry development and innovation plus (3adi+): sustainable pineapple value chain development, improving the system of social protection through the introduction of inclusive quality community-based social services, renewable energy fund: innovative finance for clean tech solutions in uruguay, supporting viet nam towards the 2030 integrated finance strategy for accelerating the achievement of the sdgs, zambia’s integrated financing framework for sustainable development, catalysing investment into renewable energy for the acceleration of the attainment of the sustainable development goals in zimbabwe.

Advertisement

From “Decent work and economic growth” to “Sustainable work and economic degrowth”: a new framework for SDG 8

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 23 October 2021

- Volume 49 , pages 281–311, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Halliki Kreinin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0095-8393 1 , 2 &

- Ernest Aigner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8195-3588 1 , 3 , 4

29k Accesses

39 Citations

42 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) have successfully raised awareness and built momentum for taking collective action, while also remaining uncritical of the central causes of the environmental crises – economic growth, inequality, and overconsumption in the Global North. We analyse SDG 8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” from the perspective of strong sustainability – as phenomena, institutions and ideologies – and find that it does not fit the criteria of strong sustainability. Based on this observation, we propose a novel framework for SDG8 in line with strong sustainability and the latest scientific research, “Sustainable Work and Economic Degrowth”, including a first proposal for new sub-goals, targets and indicators. This encompasses an integrated systems approach to achieving the SDGs’ overalls goals – a sustainable future for present and future generations. The key novel contributions of the paper include new indicators to measure societies’ dependence on economic growth, to ensure the provisioning of welfare independent of economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Sustainable Development Goals prioritize economic growth over sustainable resource use: a critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective

A Narrative Review of Research on the Sustainable Development Goals in the Business Discipline

Social Innovation for Sustainable Development

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The SDGs, as part of the UN’s “2030 Agenda” were meant as a global answer to the problems posed by looming environmental crises and poverty (UN 2015 ). The aim of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their 169 targets was to set an ambitious new plan to “end poverty without imposing significant costs on Earth’s life-support systems” (Gaffney 2014 ). The SDGs have been successful in bringing attention to many different ecological and social crises and are an impressive product of political compromise and dialogue. Some of the SDGs have been praised by environmental researchers for aiming to “achieve harmony with nature”, with corresponding indicators concentrating on the environmental impact of human societies in line with strong sustainability, i.e., such as SDG 6 – “Clean Water and Sanitation” “Life below Water” (SDG 14), and “Life on Land” (SDG 15) (Hickel 2019a ; Eisenmenger et al. 2020 ). Social goals such as “No Poverty” (SDG 1), “Zero Hunger” (SDG 2), “Good Health and Well-Being” (SDG 3), “Quality Education” (SDG 4), and “Gender Equality” (SDG 5), indicate the extent to which globally unequal social relations and unmet human needs structure everyday lives and still plague global societies (UN 2015 ).

However, they have also remained contested due to some inherent inconsistencies – most visible in the case of SDG 8, the focus of this policy study. Criticism of internal inconsistencies include that SDG 1 accounts for poverty only monetarily, not in terms of human needs, and without facilitating the redistribution of wealth, suggesting that it therefore cannot meet its goal of poverty reduction (Salleh 2016 ; Lim et al. 2018 ; Hickel 2019a ). It is also argued that further guidelines are needed to make sure that SDG 9 (“Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure”) is compatible with sustainability (Lim et al. 2018 ), and that SDG 17 (“Partnerships for the Goals”) facilitates the corporate capture of the SDGs (Rai et al. 2019 ; Eisenmenger et al. 2020 ). SDG 8 “Decent work and economic growth”, which undermines sustainability directly, has come under the most extensive criticism from the start of the Agenda 2030 process and discussions (Adelman 2018 ; Demaria 2018 ; Rai et al. 2019 ; Hickel 2019a ; Eisenmenger et al. 2020 ). This is because long-term economic growth is at odds with ecological sustainability (Haberl et al. 2020 ; Wiedenhofer et al. 2020 ). The need for remaining within a safe operating space for humanity also encompasses the need for transforming work, creating new forms of work, and terminating work, since the work process is the mediating link between society and the environment (UNDP 2015 ). This makes the focus on the “decency” of work a good start for social outcomes, but inadequate for long-term social-ecological sustainability. Reimagining SDG 8 – from “Decent Work and Economic Growth” to “Sustainable Work and Economic Degrowth” is therefore a critical first step to making the SDGs more internally coherent, and meeting the goals of Agenda 2030.

We provide a new framework, targets, sub goals and indicators for SDG 8 in line with the latest scientific evidence and the paradigm of strong sustainability. The new framework provides a starting point for further discussions on indicators to measure societies’ independence of growth, and hence move towards sustainability. The remaining sections are organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and provides the background for the study. Section 3 documents the research method and design of the study. Section 4 provides the findings of the analysis of the current SDG 8 framework, as well as the new proposed indicator framework. Finally, Sect. 5 provides tentative policy advice, provisional conclusions, and avenues for further research in this field.

2 Conceptual framework: Strong Sustainability, Degrowth, and Sustainable Work

“[T]he strong sustainability criteria (…) is derived from the recognition that natural resources are essential inputs in economic production, consumption or welfare that cannot be substituted for by physical or human capital(…) it is understood that some environmental components are unique and that some environmental processes may be irreversible (over relevant time horizons). (…) Strong sustainability focuses on ecosystems and environmental assets that are critical in the sense of providing unique and essential services (such as life-support) or unique and irreplaceable non-use values. The ozone layer is an example of the first; songbirds or coral reefs might be an example of the second.” (Ayres et al. 2001 , pp. 4–5)

The research fields of degrowth and sustainable work are based on the paradigm of strong sustainability that views the economy as a sub-system of society, in itself a sub-system of the environment (Ayres et al. 2001 ; Elder and Olsen 2019 ). While societal and economic systems are not “natural” (they are not bound by any “natural laws” but rather created by humans, and can therefore be altered), it is not possible to alter the natural system or ecological limits (Spash 2020 ). If there is a conflict between the economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability, this means that we must prioritise the environmental, as both society and economy are dependent on it.

Research in degrowth is interested in a “socially sustainable and equitable reduction (and eventually stabilisation) of society's throughput” while ensuring wellbeing (Kallis 2011 , p. 873). Currently postgrowth/degrowth scenarios, while politically complicated, are humanity’s best bet to avoiding a devastating 1.7 degrees of warming by 2030, as predicted by the latest IPCC report (Hickel et al. 2021a ). This is because “degrowth scenarios minimize many key risks for feasibility and sustainability compared to technology-driven pathways, such as the reliance on high energy-GDP decoupling, large-scale carbon dioxide removal and large-scale and high-speed renewable energy transformation” (Keyßer and Lenzen 2021 ). Importantly, the focus of degrowth lies in limiting the economic expansion of the Global North to give people in the Global South the chance to meet their material needs for wellbeing within the bounds of the planet. Degrowth is thus about reorienting the economy towards societal welfare – this might even entail nominal economic growth in the Global South in the short-term, as material and energy expansion is needed to provide for human needs. However, the key point is limiting economic expansion beyond what is needed for societal welfare to avoid ecological collapse – starting with the affluent North (Schneider et al. 2010 ; Kallis 2011 ). Degrowth in the Global North is needed most of all for the “buy-in” of the Global South to long-term social-ecological sustainability. Current lifestyles in the Global North are deeply unsustainable and unjust (Wiedmann et al. 2020 ). Replicating the old pattern of industrial development of the Global North in the Global South will place all (both Global North and Global South) outside the safe operating space for humanity with planetary boundaries (Krausmann et al. 2016 ; Görg et al. 2017 ; Steffen et al. 2018 ).

The sustainable work concept focuses on work as a relation between society and nature, in other words a relation of societal throughput in the economy. Relevant literature includes research on degrowth, postwork and ecofeminist critiques of both the organisation of work (productive and reproductive work), and its role in driving environmental crises through the consumption of materials/primary energy (Littig 2002 , 2018 ; UNDP 2015 ; Barth et al. 2016 , 2018 , 2019 ). Sustainable work also makes practical and normative suggestions for the societal organisation of work. Work should: (1) facilitate mixed work options for both men and women including paid/unpaid, self-providing, and community work; (2) allow for a “self-determined sustainable way of life for men and women”; (3) guarantee long-term health; (4) provide fair pay for all genders (including income and transfers); and (5) be in line with ecologically and socially compatible production of goods and services (Littig 2018 , p. 574). Of course, achieving sustainable work potentially reduces the significance of work in contemporary societies, for large fractions of work today are not in line with the four aspects of sustainable work. This has been emphasized by the UNDP ( 2015 ), as achieving sustainable work does not only require new forms of work, or the transformation of work, but also the termination of work. Importantly, the theory of sustainable work employed here departs from the concept of sustainable work used by Eurofound ( 2015 , 2017 ) and other researchers (i.e. Docherty et al. 2009 ) in relation to supporting life-course and full employment. These latter conceptualisations of sustainable work focus solely on social sustainability and do not include an in-depth consideration of the environment as the basis for the materials and energy inputs and waste-sink outputs of the work process, in line with the paradigm of strong sustainability.

In this paper, we first analyse SDG 8 from the perspective of strong sustainability, as phenomena, institutions and ideologies, and as the next step, provide a new alternative indicator framework. The new “Degrowth and Sustainable Work” framework roughly follows the approach of Foster et al. ( 2020 ) and Niemeijer and de Groot ( 2008 ) for selecting indicator sets. This process includes three steps: (1) defining a research question, (2) identifying a causal network (in this case the wider national and global policy arena), and (3) selecting indicators. This conceptual framework for indicator selection emphasises indicator sets, rather than single indicators, as well as focusing on the interrelation of different indicators and goals (in work, welfare, the economy, and the environment). It thus facilitates “the identification of the most relevant indicators for a specific domain, problem and location, leading to an indicator set that is at once transparent, efficient and powerful,” in its ability to consider economic and social drivers of environmental impacts (Niemeijer and de Groot 2008 , pp. 14, 16, 21).

This paper is underpinned by the new policy sociology theory of policy analysis and study. It sees the state (as well as the field of international policy-making) as a contested terrain of political action, rather than a unitary actor making simple managerial decisions based on rationality. The aim of policy study then, as one of the central purposes of socioeconomic research, is to review and evaluate policies meant to shape or guide societal (or environmental) welfare (Blackmore and Lauder 2005 ; Foster et al. 2020 ). Indicators “measure policy progress, success, or failure” but also assign importance to certain things, and thus “shape our view of ‘objective’ reality” (Foster et al. 2020 , p. 4). While the selection criteria for SDG indicators is the following: “policy-relevant, reliable, measurable/clearly defined, simple/easily communicated, broad in scope, and limited in number” (Allen et al. 2020 , p. 523), economic and social indicators of sustainability most importantly must be in line with the concept of strong sustainability and the latest environmental science (Wiedmann et al. 2020 ; IPCC 2021 ).

Since indicators shape social actuality through measuring and highlighting certain elements, it is important to be open and transparent about political priorities and subjective choices (which exist in every process of selecting indicators, and indeed in the wider policy process). In this policy study, the basis for selecting indicators for the new SDG 8 goal is a review of indicators to measure societal progress towards social and environmental welfare in line with environmental science and strong sustainability, relevant to economy and work. In addition, the contribution of this paper includes new proposed indicators, as a starting point for discussions on a new altered SDG 8. Footnote 1

The strong sustainability approach to environment-economy relations bears consequences for the types of indicators we use to assess sustainability and welfare, since, as mentioned above, indicators are normative, political, and value-laden tools. From the perspective of strong sustainability, therefore, sustainability indicators must measure scale, and distribution, while staying open to value pluralism (Roman and Thiry 2017 ). This translates to measuring the effects of the scale of economic activity on the environment, such as pressures on ecosystems, as well as the social foundations of the economy, including how material resources and welfare is divided between different groups globally and nationally. Finally, value pluralism means that an emphasis is put on critiquing and politicising the use of different measurements, and opening up the debate on indicators (Roman and Thiry 2017 ).

We follow the policy advice on (strong) sustainability indicators when proposing the new SDG 8 framework. There are a plethora of “beyond GDP” indicators aiming to measure welfare and sustainability, including indicator sets (dashboards), aggregate non-monetary indices, aggregate monetary indices, as well as subjective wellbeing indices – however, not all are in line with strong sustainability (Walker and Jackson 2019 ). The principles of strong sustainability exclude aggregate monetary indices as a relevant measure of the economy’s environmental sustainability as well as financial measurements of the environment, due to strong uncertainty, value incommensurability, and the preanalytic vision of the economy as a sub-system of the biosphere (Spash 2012 ; Roman and Thiry 2017 ). Aggregate non-monetary indices also include inherent problems with ranking and weighting, which can leave the resulting number easily manipulatable where there is a lack of cohesive theory (Walker and Jackson 2019 , p. 8).

The main shortcoming of indicators sets (such as the SDGs themselves), on the other hand, is that they can easily become overwhelming due to the number of different information included. There must therefore be a limit on the number of indicators included in order to provide a succinct and simple policy tool. Nevertheless, indicators sets can provide more complex and multidimensional information on progress (Walker and Jackson 2019 ). Subjective wellbeing indices can augment other indicators, since welfare also consists of subjective experiences – however, these measures can be susceptible to one-off events (i.e. moods), and cannot account for environmental sustainability (Walker and Jackson 2019 ). With certain exceptions for aggregate indices, we therefore largely focus on non-aggregate indicators of scale of the environmental impact of the economy, distribution of welfare and harm, and subjective wellbeing, as relevant measures of sustainable welfare for the new SDG 8 indicator set. Where possible, we refer to literature and existing indicators, suggesting necessary new indicators where needed, and limiting the number of indicators for conciseness and policy relevance. Some of the proposed indicators reflect a conceptual starting point and require additional research in collaboration with experts in the respective fields to better identify the causal mechanisms.

In summary, this policy study followed a coherent research design to develop a preliminary new framework for SDG 8 in line with strong sustainability. In the next section, we will present this framework and discuss the results of the policy analysis. (Table 1 ).

4 Strong sustainability and SDG 8

The current SDG 8 sub-goals can be seen in Table 2 in the Appendix, which also explains whether they pertain to economic growth, work, or both. A major concern of the ability of the SDGs to fulfil their goals is linked to SDG 8. As Table 2 shows, seven of the 12 sub-goals of SDG 8 focus on economic growth. Three focus directly on economic growth and production (sub-goals 8.1, 8.2, 8.3), while economic growth is related resource and energy use, tourism, financial markets and foreign direct investments in sub-goals 8.4, 8.9, 8.10, and 8.a, respectively. Eight out of the 12 sub-goals of SDG 8 are related to “work”. However, only two are indeed related to the decency of work (sub-goal 8.7 and 8.8), the rest of focus on the goal of increasing employment in society, and their respective productivity – which are not in line with strong sustainability and the UNDP ( 2015 ) framework on sustainable work (sub-goals 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6, 8.7, 8.9, 8.b). “Decent work” is an important goal, however, since the work process in fundamentally important for sustainability, the goal must become sustainable work – to encompass social and environmental sustainability aspects of work, as well as decency, in line with the goals of Agenda 2030.

4.1 The problems with SDG 8 – “Economic Growth”

Since World War II, economic growth has dominated both societal discussions as well as Economics, despite long-standing critique. This is because economic growth represents not only a “phenomenon” but also an “institution”, and an “ideology” (Haapanen and Tapio 2016 ). GDP was born as a wartime measure to assess countries’ wartime production capabilities, but was never intended as a measure of wellbeing. It became a proxy for economic welfare as well as general societal welfare, due, in part, to the ease of the single numeric representation – despite its crass oversimplification of reality (Stiglitz et al. 2018 ). The use of GDP as a proxy for societal wellbeing has been widely criticised, yet GDP continues to hold dominance (Fitoussi and Durand 2018 ; Stiglitz et al. 2018 , 2020 ). In this section, we will analyse the problems with economic growth –as a “phenomenon” (i.e. its direct energy/material and waste manifestation), as an “institution” (i.e. in its relation to institutions such as the welfare state), and as an “ideology” (i.e. its dominance in public discussions as a “normal”/”natural” phenomenon outside critique), while referring to the sub-goals of SDG 8 and how these should be altered in line with strong sustainability (Haapanen and Tapio 2016 ).

4.1.1 Economic Growth as a phenomenon – social welfare

Considering economic growth as a phenomenon, many economists agree that economic growth fails to capture the most important aspects of social welfare. It does not capture the distribution of income in society, or the extent to which and how many members of society successfully have their basic needs met in the process of production and consumption. It does not measure health, happiness, education, equality of opportunity, or even whether the economy is headed for a crash (Fitoussi and Durand 2018 ; Stiglitz et al. 2018 , 2020 ). Despite correlations between welfare and GDP per capita, depending on the respective region, deviations are often large (Jones and Klenow 2016 ). There is also a long history of critique of equating economic growth or increased consumption with wellbeing (including health and happiness), rather than social policies (Easterlin 1974 ; Preston 1975 ). Wellbeing is related to economic activity, but this consideration must include the role nature and the physical reality of environmental systems, as well as broader societal institutions and norms, and considerations of the economic process as a historic, irreversible, materials and energy-converting process (Ayres and Warr 2009 ).

Many citizens in the Global South need better access to material and energy resources to meet their basic needs and improve their lives – which would even entail GDP growth. However, measuring GDP growth alone tell us little about whether increased production and consumption has improved access to basic resources for the material welfare of those in need, or been captured. Research suggests that especially in places of high deprivation, a focus on wellbeing and meeting human needs is more efficient (than a GDP-growth focus) and does so within planetary boundaries (Brand-Correa and Steinberger 2017 ; Hickel 2019a ; Steinberger et al. 2020 ). Although the Global North has experienced huge levels of economic growth since the 1970s and 1980s, this has not translated into increases in welfare because of stagnating wages and rising inequality (Rezai and Stagl 2016 ) and because consumption has mostly been spent on positional goods by higher income groups, not to meet human needs (O’Neill et al. 2018 ). Arguably, the positive relationship between economic growth and welfare from the start of industrialisation leading up to the 1970s, in Global North countries, was institutional – in other words it was due to political rules and institutions – as post-war public welfare was achieved in the political terrain of policy-making, in political struggles (Berberoglu 2019 ; Hickel 2019b ; Cahen-Fourot 2020 ). Collective provisioning systems (health care centres, public transport, garbage disposal, as well as access to shelter, sanitation and minimum floor area) have historically been more important to the attainment of wellbeing than average income or total energy consumption (Baltruszewicz et al. 2021 ).

The real aim of poverty reduction within planetary boundaries must focus on reducing inequality, not on further economic expansion as a way to avoid distributional issues – although this is politically much more difficult. Given the current relationship between economic growth and poverty reduction through income growth for the poorest, it would take 207 years to eliminate poverty ($5 a day) via economic growth, and require the global economy to grow to a size 175 times larger than in 2015 (Hickel 2015 ; Salleh 2016 ). Research on material flows shows the continuation of uneven relations between the Global North and Global South – “a widespread intuition in both capitalist core nations and more peripheral areas that the economic and technological expansion of the former occurs at the expense of the latter” (Hornborg 2009 , p. 245). Between 1990–2015, high-income countries have simultaneously appropriated resources with high-embodied material, labour and land from low-income countries, while generating monetary surplus though taking part in international trade – in effect keeping the Global North developed on the back of the Global South (Dorninger et al. 2021 ). This drain from the Global South to the Global North since the 1960s has totalled around $62 trillion, or $152 trillion (constant 2011 US Dollars) when also considering lost growth. Drain through unequal exchange now equals around $2.2 trillion a year, enough to end extreme poverty 15 times over (Hickel et al. 2021b ). Rises in foreign direct investments have been historically also tied to land grabbing and the destruction of local sustainable community livelihoods (De Schutter 2011 , 2013 ), while international trade currently increases global resource use (Plank et al. 2018 ). Further global trade, in its current form, can therefore be seen not as the answer to, but rather the driver of continued inequalities, underdevelopment, and environmental crises.

The inclusion of SDG sub-goals 8.1, 8.2 and 8.3 thus promotes a narrative of poverty reduction which is inefficient at best, and unsustainable in the long term (Lim et al. 2018 ). Sub-goal 8.a, on the other hand is not in line with current trade patterns of ecologically unequal exchange. Sub-goal 8.10 is contradictory to the overall (current) goal of SDG 8, as it remains open, how financialisation of the economy, nature, society, environment, or work, should contribute to economic growth or decent work (Epstein 2005 ; Fine 2013 ; Hache 2019 ; Kemp-Benedict and Kartha 2019 ). A better set of sub-goals would set out to provide welfare within planetary boundaries, and would aim to measure societal well-being in a society within the Earth’s carrying capacity – a measure of whether a society is moving towards a sustainable wellbeing economy. New indicators would need to include subjective and objective well-being measures; calculated for different societal groups (O’Neill 2012 ; O’Neill et al. 2018 ). Considering the well-being of the lowest group (for instance at the 10th percentile), would be especially important to achieving subjective and objective wellbeing for all. To measure material well-being, indicators measuring material deprivation and outlining access to basic social goods and services should be used, instead of using the proxy of GDP growth (Hickel 2019a ). We also suggest that one indicator should measure the wellbeing of non-human beings and eco-systems, which is not included in SDG 8, but forms a wider understanding of societal “wellbeing” in strong sustainability (Ayres et al. 2001 ; Kopnina and Cherniak 2015 ). This could include for instance measuring animal rights and share of wilderness and non-managed ecosystems. Further, wellbeing also entails human-nature relations in terms of a healthy and stable environment – which is separate from measuring the environmental impacts of the economy. We suggest that an additional indicator would be needed to be calculate this for generational welfare—in terms of the chances of living a full life, including long-term effects of the climate crisis and the probability of other tipping points that will mainly affect younger generations.

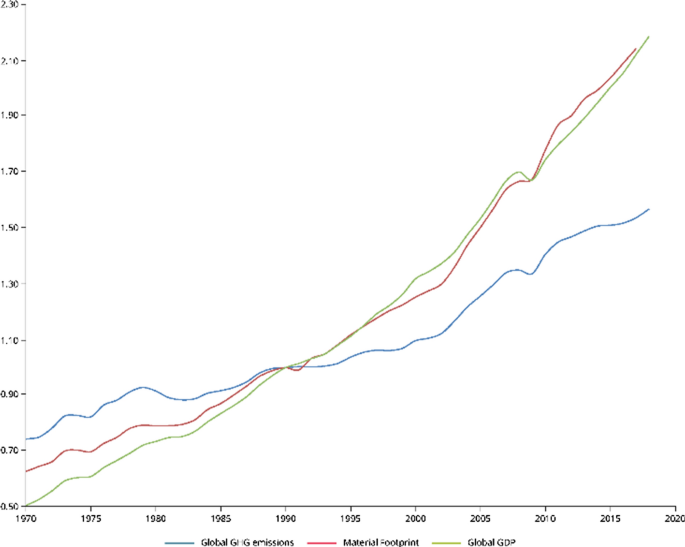

4.1.2 Economic Growth as a phenomenon – environmental welfare

Economic growth has historically been coupled to the devastation of the natural world, thus undermining the long-term ability of societies to provide for their needs. Economic growth has globally not been decoupled from resource consumption and environmental impacts, and it cannot be decoupled at a scale and speed necessary (i.e. using technology) to avoid dangerous climate change and other environmental crises – especially biodiversity loss, which possibly poses an even starker challenge than climate change, yet remains largely under-discussed in Economics (EEA 2019 , 2021 ; Haberl et al. 2020 ; Wiedenhofer et al. 2020 ; Wiedmann et al. 2020 ). The global material footprint has increased in line with GDP and GHG emissions (as shown on Fig. 1 ), while there have been efficiency gains in GHG emissions. Rising energy expenditures (since globally the most easily accessible sources of energy and materials have been used up) as well as rebound effects make continued economic growth an unsustainable goal for societies, while technological progress is unlikely to offer solace due to the life-cycle energy and materials intensity of technology, as well as its impacts of biodiversity loss (Ayres and Warr 2009 ; Rammelt and Crisp 2014 ; Parrique et al. 2019 ). Despite different country-based accounting methods showing a decoupling of economic growth from environmental impacts (CO2 emissions, but not biodiversity loss) or materials use, the idea of the environmental Kuznet’s curve has been widely critiqued. Instead of maturing out of emissions and materials use, countries in the Global North have rather shifted (CO2) emissions to the Global South, while holding on to the profits – leading to a strong “recoupling” of growth and emissions in the Global South, and decoupling in specific Global North countries – an accountancy trick (Roberts and Parks 2009 ; Dorninger et al. 2021 ).

Relative change in main global economic and environmental indicators from 1970 to 2018. Source: (EEA 2021 )

A strong set of indicators of the effect of the economy on the environment would not leave legal cracks for such accountancy tricks. As we explained, sub-goal 8.1 is an inadequate strategy for poverty alleviation and welfare and also not in line with avoiding dangerous climate change, while sub-goal 8.2 is short-sighted when it comes to technological solutions (Hickel 2019a ). Sub-goal 8.4 can be considered part of a “poorly conceptualised fantasy” that “functions to obfuscate fundamental tensions” between economic expansion and environmental limits, and out of touch with the need to stay within the Earth’s carrying capacity, or indeed on the effects of technology on biodiversity (Schandl et al. 2016 ; Fletcher and Rammelt 2017 , p. 450; Keyßer and Lenzen 2021 ). We suggest that it would be necessary to measure the environmental effects of the economy, including indicators for material and energy use, biodiversity loss, footprints, and intensities to indicate the reduction in material throughputs. This includes measures of the direct material and energy inputs in absolute terms, but also shares of renewable energies (O’Neill 2012 ). Since material and energy use is highly concentrated on selected sectors, indicators that capture the most material and energy intensive sectors are important, as for instance the domestic value added of the globally ten most polluting sectors, as a share of total domestic value added. To avoid accountancy tricks, and to measure ecologically unequal exchange, we suggest that new SDG 8 indicators should also reflect on the harm caused abroad by domestic final consumption. This harm is embedded in intermediate goods and services imports. It is further embedded in hidden non-imported flows of materials generated in the exporting countries to support production, impacting their environment and population. Footprint indicators calculating material and energy use in final consumption would need to be extended in two ways to adequately measure economy-environment interactions and whether societies are moving towards a more sustainable and equitable path, in line with strong sustainability. Firstly, separate indicators should be calculated on the material and energy footprint of intermediate goods by sector and industries, to identify industries that are particularly harmful; secondly, material and energy indicators for the exported goods themselves would need to be considered, since export-led economic growth should not be based on material and energy intensive sectors. Furthermore, we suggest that more complex indicators should reflect on secondary and tertiary effects of consumer goods exported to other countries (i.e. full life-cycle emissions of cars produced and exported).

4.1.3 Economic Growth as an institution and ideology

“In the EU, as elsewhere, we must dislodge growth from our institutions, as well as from our imaginaries and engage in a ‘well-being transition’. The need for and desirability of this has never been so strong, nor has our ability to achieve it.” (Laurent 2021 , p. 34)

Economic growth is an institution and tied to other institutions, rules, and norms in society, which make it harder to challenge. Societal institutions based on growth, requiring growth, or boosting growth are omnipresent, including full-time work (through the productivity trap), the welfare state, social services, and taxation, amongst others. Economic growth and paid labour are currently connected drivers of environmental crises (Victor 2008 ; Jackson 2009 ; Jackson and Victor 2011 ; Kallis et al. 2012 ; Bohnenberger and Fritz 2021 ). While researchers are already contending with the difficult issue of the operationalisation of a welfare state in a non-growing economy (Bohnenberger and Fritz 2021 ; Laurent 2021 ), a common argument for economic growth, as an institution, remains unemployment, Footnote 2 which according to ‘Okuns Law’ would sky rocket. In reality, unemployment depends on institutional arrangements and thus varies between countries (Antal 2014 ). There is evidence that certain institutions (e.g., unemployment benefits, social partnership, working time reduction, and state employment or jobs guarantee) weaken the relation between employment and economic growth (Jackson and Victor 2011 ; Knight et al. 2013 ; Stocker et al. 2014 ; Bohnenberger and Fritz 2021 ). As explained, economic growth has been used as a justification to ignore inequality – therefore the answer to remaining within the Earth’s carrying capacity and providing human welfare must focus on distributional issues (Hickel 2019b ; Wiedmann et al. 2020 ). There are enough material and energy resources available for everyone to live well – if these are not hoarded by a few (Brand-Correa and Steinberger 2017 ).

GDP growth can also be considered an ideology due to the primacy given to economic growth and its normalisation as “commonsense” despite evidence of environmental limits to increases in economic production (Ferguson 2018 ; Barry 2020 ). Economic growth became a central element of both liberal and socialist theoretical movements in the industrial era with the market economy and the planned economy sharing the same growth ideology. This worked to strengthening the place of “growthism” and societal (over)consumption as valid societal goals, despite signs of environmental pressures due to economic expansion (Takis 2005 ; Ferguson 2018 ). While it is politically difficult to challenge the ideology of growth, to achieve the goals of Agenda 2030, the environmental and social pressures of further economic growth cannot be ignored.

The amalgamation of economic growth and work in the framework of SDG 8, especially under sub-goal 8.2, 8.3, and 8.9 show how societal institutions and welfare have been coupled to the institution of economic growth, while the ideology of economic growth is especially visible in sub-goal 8.1 (Salleh 2016 ; Lim et al. 2018 ; Reichel and Perey 2018 ). We suggest that for an improved SDG 8, a set of indicators would be needed to measure the dependence of the society on economic growth for employment rates (although, as explained in the chapter that follows, this would include working time reduction). A first simple indicator could be based on the correlation between economic growth and unemployment rates in the last ten years. A next set of indicators could measure individual and societal dependence on economic growth, to show, if the respective country is able to degrow the economy in line with sustainability requirements without loss of wellbeing, social instability, or harmful economic disruptions. To the best of the knowledge of the authors, contributions on indicators that measure societal dependence on economic growth are so far missing.

The societal, state-level or institutional dependence economic growth should also be measured: this includes state institutions, inequality and employment. The dependence of state institution on economic growth relates to the ability of state to repay debts independent of economic growth and their ability to finance social provisioning, including health and care services. An indicator could be the share of social provisioning to GDP ratios. This would be distinctive from overall state expenditure to GDP. Given the substantial amount of biophysically harmful subsidies that are currently part of state expenditure, this is substantially lower than current indicators of state expenditure. Further, the dependence of the pension system on economic growth should be considered, by for instance an index for measuring financial sustainability, given current demographic composition. It has been established in the degrowth literature, that high levels of inequality (measured in income, wealth, well-being and political rights) create a dependency on economic growth as a way to avoid redistribution for improving welfare outcomes (Kallis et al. 2012 ; Hickel 2019b ). Inequality is a driver of economic growth as it drives individual consumption to keep up with higher income groups (Oh et al. 2012 ). This indicates that high levels of inequality foster economic growth. Thus, measures of inequality could be used as indicators of the dependence on economic growth, as the Gini or 10-to-90 ratio of subjective and objectives measures of well-being. Another set of indicators should measure the extent to which the economy is unsustainably dependent on economic growth – the extent to which firms need to grow to have and control a larger market share, and survive competition (Lavoie 2014 ). Again, a first proxy could be based on the correlation between bankruptcies and growth. First, on the firm level, we can measure the correlation between firm growth (in terms of workers or turnover) and bankruptcies, using similar indicators on the economy level. More complex models could further improve our understanding of the dependence of the economy on economic growth.

It would also be necessary to measure the dependence of households and individuals on economic growth. This includes subjective and objective well-being dependence on economic growth, measured with the correlation of household income and well-being indicators. A low correlation would indicate a low dependence on economic growth, since additional income would not improve the well-being of individuals; again, this should be calculated for different social groups and the 10th wellbeing percentile for wealth/income. Furthermore, the share of income spent on basic goods and services by different social groups, including the above-mentioned 10th wellbeing percentile group, could give relevant insights on the dependence of low-income groups on economic growth.

4.2 The problems with SDG 8 – “(Decent?) Work”

Much like economic growth, paid work in the growth society not only represents a “phenomenon” (as an activity), but also an “institution”, and an “ideology” – with effects on welfare and the environment. Social scientists have long established that we are living in a work-centred society, where daily lives depend on employment, independently of the value it contributes to societal or individual welfare, or indeed its environmental impacts (Weeks 2011 ; Komlosy 2018 ).

4.2.1 Work as a phenomenon – its effects on welfare

As a phenomenon, the welfare effects of paid work are contradictory. In a work society, ideally, everyone gets a little, but not too much – however paid work is also not essential to welfare in other forms of societal organising of provisioning. Material wellbeing in productive economies and societies is tied to paid employment, through which members of society can afford the necessities of life. Paid employment in a work society also provides latent positive psychosocial functions including identity, variety, social contact and community, shared goals, and routine (Jahoda 1981 , 1982 ; Paul and Moser 2006 ; Catalano et al. 2011 ). Employment is thus currently important for public health and social welfare concerns due to the negative effects of unemployment, and in this light SDG 8.3 can be considered somewhat positive. Nevertheless, 8 h a week is optimal for receiving the wellbeing effects of work (Kamerāde et al. 2019 ). The negative social welfare effects (as separate from the environmental effects, discussed below) of overemployment are manifold – including health problems (physical or mental, even death in dangerous occupations), the effect of sedentary lifestyles, isolation, and stress, as well as separation from and little time with family or friends (Jacobs and Gerson 2001 ; Cho et al. 2018 ; Tsutsumi 2019 ). Meaningless work, or so called “bullshit jobs” which do not add to societal welfare and have little value (according to the employees in these jobs), also have a negative effect on wellbeing (Graeber 2018 ). A simple focus on paid and productive labour as promoting welfare also hides the fact that productive labour relies on socially and environmentally reproductive labour, the often unpaid work of keeping society going, mostly undertaken by women (Power 2004 ; Biesecker and Hofmeister 2010 ; Ariel Salleh 2017 ). Neither socially-environmentally reproductive labour, nor the welfare effects of work are currently discussed as part of the sub-goals of SDG 8 focusing on work.

4.2.2 Work as a phenomenon – its effects on the environment

The ecological effects of paid employment, as a phenomenon, have historically been damaging. Average working hours in the US between 2007–2013 as an example had a strong positive relationship to carbon emissions (Fitzgerald et al. 2018 ) and similar effects can be seen in other studies on Germany and Italy with regard to energy use per hour worked (Fischer-Kowalski and Haberl 1998 ; Fischer-Kowalski and Haas 2016 ). In particular, work in industry and manufacturing requires high levels energy per hour worked (Hardt et al. 2020 ), implying a high energy footprint compared to most leisure activities. Much production and work is currently environmentally damaging, and not oriented towards providing activities that promote human or environmental welfare – but the creation of products for profit (Gerold et al. 2019 ). This suggests that a reduction in the quantity of paid or “productive” employment is necessary to stay within the planetary boundaries, as well as qualitative change in work itself – towards societally and environmentally necessary work (Knight and Schor 2014 ; Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ). There is an urgent need to limit the work of certain sectors: i.e. mining, fracking, deforestation, aviation, shipping and animal agriculture – while there is a need for more “work” in rewilding, nature restoration, autonomous and solidarity activities, and so on (Salleh 2016 ). Labour-intensive services such as the care sector are also in need of more work, for their – compared to other industries – low level of energy use (Hardt et al. 2020 ), and CO2 intensity. Nevertheless, also these sectors need to drastically reduce the CO2 emissions in absolute terms. Footnote 3 This includes for instance social services like care, health services and social work, where productivity increases are only possible at a cost to the quality of provisioning, and not based on higher energy use, as in productive industries producing goods. However, overall working hours likely need to be reduced drastically to achieve the Paris 1.5° C goal, given estimates that use current CO2 intensities of production (Frey 2019 ). The failure of the current sub-goals of SDG 8 to distinguish between sectoral-effects of employment puts them at odds with social and environmental outcomes.

Recent estimates have shown that factor substitution between capital and labour is very low (Gechert et al. 2021 ). Therefore, working time reduction would likely reduce the amount of employed capital (itself energy and materials intensive) as the two factors are best understood as complements. Considering the possible need to limit productive employment in line with limiting the effects of production on the environment suggests that work must be shared out more equally between members of society to avoid overwork and underemployment (Schor 2008 ; Knight et al. 2013 ). Crucially, however, the institutional context is important. Since inequality, and overconsumption by affluent members of society is a concern, working time reduction could act as a demand-side mitigation strategy if combined with a reduction in income and consumption for the affluent (Knight et al. 2013 ; Gerold and Nocker 2018 ). Work, as a phenomenon, is ecologically harmful also due to its relation to consumption, not just production, as paid employment in the growth society leads to the work-and-spend cycle, with overconsumption, compensatory consumption, and conspicuous consumption of positional goods due to overwork (Schor 2008 ; Oh et al. 2012 ; Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ). Depending on the form of working time reduction, consumption rebounds can also be large i.e. if annual work-hours decreases are used for highly carbon-intensive leisure activities such as air travel, or if working time reduction for example triggers changes in emissions related to production processes. This highlights the importance of the embeddedness of working time reduction policies in a wider sustainability-focused policy framework of reducing inequality and overconsumption (Fremstad et al. 2019 ; Antal et al. 2020 ). Complementary policies to working time reduction, such as minimum and maximum income corridors would then be necessary to make sure that those in the lower income scale could meet their material needs while limiting overconsumption by the affluent, to stay within planetary boundaries (Fuchs 2019 ).

Currently, neither the welfare effects of work nor the necessity of reducing working hours to limit the environmental effects of production are discussed in SDG 8. Sub-goals 8.3, 8.5 and 8.10. cut off “the very feet [development] stands on”, as many communities provide sustainable wellbeing for members outside commodification through commoning, community agriculture, and other means of social provisioning in line with environmental barriers and community goals (Salleh 2016 , p. 954). Therefore, a focus on measuring welfare through meeting material needs could be more fruitful than paid employment.

The decency of work should entail the social value and environmental harm of the good produced in a certain economy. A core question would be, if the respective work contributes to achieving the SDGs at large. Graeber ( 2018 ) points out that the social value of work can also be evaluated by workers themselves. Work-place wellbeing and the perceived ability to co-determine work-arrangements and the products of work should be considered. Policies such as a voluntary jobs guarantee, working time reduction and work sharing, universal basic services, or even income, would help provide decent lives while reducing the pressure to accept indecent (including environmentally harmful) employment. Again, in addition to national averages, indicators by gender, age, ethnicity, and at the 10th wellbeing percentile would be important in measuring the sustainability and decency of work. Another aspect of the decency of work are working hours and their respective distribution. Hence, Gini hours in paid work and share of labour force in paid work of more than 30 h a week could provide important insights in line with sustainability and welfare requirements (von Jorck et al. 2019 ). For an improved SDG 8, a set of indicators should reflect the dependence of states and individuals on indecent and unsustainable work (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ; Hardt et al. 2020 ). Such indicators relate to literature in the field of welfare-state research, including the level of decommodification, the right-not-to-work and share of population with access to social security. The latter could also be relevant relative to the share of the working population, in order to measure the dependence on work to access social security. High unemployment rates also indicate a high dependence on work. Again, an index of institutions that reduce unemployment and employment could be relevant, including universal basic services or income, a voluntary jobs guarantee, or work-sharing/working time reduction.

Currently SDG 8 covers the decency of work in sub-goals 8.7 (anti-slavery) and 8.8 (labour standards). However, sub-goal 8.8 does not discuss which types of work are societally needed if work needs to be limited due to its environmental and societal impacts – as Bohnenberger also explains in this special issue. Furthermore, the sub-goals do not reflect a goal, but much more the status quo in wealthier Global North countries, which have stronger historic labour institutions in better bargaining positions for basic human, and health and safety rights, or payment. Impacts on other economies and societies need to be considered in order to achieve wellbeing, economic degrowth, and sustainable work. Gómez-Paredes et al. ( 2015 ) propose a labour footprint that calculates for instance forced, indecent, harmful, and child labour embedded in imported goods and services. For a new and improved SDG 8, a measure of decent work would not only entail social harm caused in other places related in imported goods, but also impacts on other countries for exports of socially harmful goods or services, for instance the share of exports of weapons and fossil fuels.

4.2.3 Work as an institution and ideology

Paid work is both an institution as well as tied to other institutions – especially in growth economies. We have already discussed the relationship between economic growth and work as institutions. The narrow dependence on paid employment as the road to societal services i.e. healthcare, education, housing, effectively make work an institution of societal control (Weeks 2011 ; Frayne 2015 , 2016 ). This reflects a societal shift from welfare to workfare, and has serious consequences for staying within planetary limits while providing societal welfare, due to the escalatory logic of the growth system (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ). “Decent” work in the form of paid labour is not available to everyone (Scherrer 2018 ), and this type of “development” through labour market integration is unlikely to lead to long-term sustainable welfare (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ). Rather, the focus should therefore be on providing material welfare – whether inside or outside formal employment. As the UNDP ( 2015 ) points out, work not only needs to be decent, but also environmentally unharmful, to be sustainable. Globally, the number of un-, under- and precariously employed people is increasing, while social rules are globally institutionalising inclusion through the formal labour market only (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ; Scherrer 2018 ). However, when access to services is institutionalised on the basis of formal employment, this implies that those without access to work are excluded from basic services (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ; Gerold et al. 2019 ). This highlights the contradictory position of work as an institution of social control (Weeks 2011 ). In the Global North (i.e. Austria) currently welfare state access for migrants for example is limited via a restricted access to the labour market (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ).

The SDGs not only tie the institutions of economic growth to the institution of work, but also “praise” and promote paid work, as the only solution to poverty and sustainability – this is because paid work can also be considered an ideology. Komlosy ( 2018 ) divides discourses around work into either (1) “praising work”, (2) “overcoming work”, or (3) “transforming work”. Staying within planetary boundaries while providing societal welfare requires that we reconsider both economic growth as a goal, as well as work, which is “assumed as a natural feature of society and as an end in itself” (Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 , p. 344). Employment and work ethic are inherently related to attitudes towards social and environmental issues. Questioning the ideology of work allows us to review work which legitimises morally questionable or unsustainable activities, as jobs have been historically used as an excuse to destroy the environment (Räthzel and Uzzell 2011 ; Hoffmann and Paulsen 2020 ). Questioning the work ideology allows us to review ideas of autonomy and agency in decision making, when it comes to work – wage-labour exceptionalism during the Corona crisis showed the prevalence of work over autonomous time and the problems with the ideology of work. Currently, there is little or no co-determinism of what is produced, why, and for whom (Gorz 1985 ).

“Praising work” is a fundamental part of the ideology of work in the growth society, and reflected in SDG 8. Both the sub-goals that relate to youth unemployment (8.6, 8.b), as well as those pertaining to productive fulltime work (8.3, 8.5, 8.9) implicitly praise work and productivism, as an ideology – i.e. independent of the effects of work on society (welfare) or the environment (ecological sustainability). Sub-goals 8.3, 8.5, and 8.6 underwrite the institution of work without considering the escalatory effects of aiming to provide societal welfare through paid labour only. Sub-goal 8.7, which aims to end forced and child labour is the only relevant target which counters the implicit morality of work as an institution, and challenges the primacy of work in its relation to other institutions. We suggest that in order to measure the social effects of work, a set of indicators should reflect the demand for participation and autonomy. Indicators with regard to participation could be based on an extensive notion of democracy, which goes beyond representative democracy to economic democracy. This could include the share of cooperatively organised firms and companies and the ability to decide on production processes in a certain country. Secondly, time-autonomy could be used to measure daily available time that is not occupied by paid or unpaid work and care activities. Again, the indicators should be calculated for different social groups. In particular, discretionary time is likely to be limited for women, relative to men, due to current societal inequalities in unpaid work and care. As an already existing indicator, “Time wealth” is a useful index that goes beyond measuring paid/unpaid time to include five dimensions of time quality relevant for discussing sustainable work: tempo (speed), plannability, time synchronisation, time sovereignty, and free time (von Jorck et al. 2019 ).

4.3 Sustainable work and economic degrowth—a new set of indicators for SDG 8

In the following, we bring together all of the analysis of the previous chapters to provide a preliminary new SDG 8 indicator framework to measure progress towards degrowth and sustainable work – for welfare within Earth’s carrying capacity. Building on an understanding that indicators must be open to value pluralism, it is the objective of the authors here to provide a starting point for a broader democratic debate on which indicators should be included as part of SDG 8. We base our indicator framework in Table 1 , on the methodology presented in Sect. 3 , and the preceding discussion in Sect. 4 . We highlight already existing robust indicators or indices in literature, and propose novel indicators for measuring further aspects of societal welfare, which do not yet exist. Given the exploratory nature of the study, the proposed indicators vary in their elaboration and local applicability. Some of them aim to identify a causality (e.g. of economic growth on unemployment). Identifying all possible causal mechanisms is beyond this exploratory article and there is a strong need for additional research in collaboration with experts in the respective fields.

Further, it is noteworthy that the focus on economic degrowth requires a focus at the lower end of the respective distribution, as the measures do not focus on increasing the well-being of the average of a certain population, but rather aim to ensure that all citizens meet their basic needs. Hence, all indicators focus on the 10th income/wealth percentile of the respective distribution, and not the average.

Sub-goal 1), Wellbeing , focuses on providing sustainable welfare in line with the Earth’s carrying capacity, as well as the welfare of ecosystems and non-human animals, including the temporal element of welfare – whether societies are headed for collapse. We suggest that the Happy Planet Index is an existing and easily operationalisable aggregate measure of subjective welfare, while the human needs within planetary boundaries approach of the “Safe and just framework” provides a robust existing dashboard of indices of material welfare as an objective measure. In addition to considering the effects of the economy on non-human living beings and wilderness (Aplet et al. 2000 ), we suggest that measures of wellbeing should additionally consider the possibilities of future generations to meet their material and welfare needs, as the outcome of current production and economic processes. This new indicator should be based on robust and internationally agreed modelling of future scenarios by the IPCC (i.e. IPCC 2021 ), but to the best knowledge of the authors does not yet exist. Despite possible problems with such an operationalisation (not limited to the critique that scenario analyses tend towards optimism as the norm (Keary 2016 ; van Zeist et al. 2020 )), a similar measure would be needed to provide a coherent overview of the extent to which current material welfare is “stolen” from future generations.