- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Nile valley and delta

- The Eastern Desert

- The Western Desert

- Sinai Peninsula

- Plant and animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Rural settlement

- Urban settlement

- Demographic trends

- Agriculture and fishing

- Resources and power

- Manufacturing

- Labour and taxation

- Transportation and telecommunications

- Local government

- Political process

- Health and welfare

- Cultural milieu

- Daily life and social customs

- Cultural institutions

- Sports and recreation

- Media and publishing

- The Arab conquest

- Early Arab rule

- Egypt under the caliphate

- The Ṭūlūnid dynasty (868–905)

- The Ikhshīdid dynasty (935–969)

- Islamization

- Arabization

- Growth of trade

- The end of the Fāṭimid dynasty

- Saladin’s policies

- Power struggles

- Growth of Mamluk armies

- Political life

- Contributions to Arabic culture

- Religious life

- Economic life

- The Ottoman conquest

- Ottoman administration

- Mamluk power under the Ottomans

- Religious affairs

- The French occupation and its consequences (1798–1805)

- Military expansion

- Administrative changes

- ʿAbbās I and Saʿīd, 1848-63

- Ismāʿīl, 1863–79

- Renewed European intervention, 1879–82

- ʿAbbās Ḥilmī II, 1892–1914

- World War I and independence

- The interwar period

- World War II and its aftermath

- The Nasser regime

- The Sadat regime

- The Mubarak regime

- Unrest in 2011: January 25 Revolution

- Transition to an elected government

- The June 30 Revolution

- Return to authoritarianism

- Why is Cleopatra famous?

- How did Cleopatra come to power?

- How did Cleopatra die?

- When did Ramses II rule Egypt?

- What military campaigns did Ramses II undertake?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- CRW Flags - Flag of Egypt

- Official Tourism Site of Egypt

- Jewish Virtual Library - Egypt

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - Egypt

- globalEDGE - Egypt: Introduction

- Egypt - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Egypt - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Egypt , country located in the northeastern corner of Africa . Egypt ’s heartland, the Nile River valley and delta, was the home of one of the principal civilizations of the ancient Middle East and, like Mesopotamia farther east, was the site of one of the world’s earliest urban and literate societies. Pharaonic Egypt thrived for some 3,000 years through a series of native dynasties that were interspersed with brief periods of foreign rule. After Alexander the Great conquered the region in 323 bce , urban Egypt became an integral part of the Hellenistic world . Under the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty , an advanced literate society thrived in the city of Alexandria , but what is now Egypt was conquered by the Romans in 30 bce . It remained part of the Roman Republic and Empire and then part of Rome’s successor state, the Byzantine Empire , until its conquest by Arab Muslim armies in 639–642 ce .

Until the Muslim conquest, great continuity had typified Egyptian rural life. Despite the incongruent ethnicity of successive ruling groups and the cosmopolitan nature of Egypt’s larger urban centres, the language and culture of the rural, agrarian masses—whose lives were largely measured by the annual rise and fall of the Nile River, with its annual inundation—had changed only marginally throughout the centuries. Following the conquests, both urban and rural culture began to adopt elements of Arab culture, and an Arabic vernacular eventually replaced the Egyptian language as the common means of spoken discourse. Moreover, since that time, Egypt’s history has been part of the broader Islamic world, and though Egyptians continued to be ruled by foreign elite—whether Arab, Kurdish, Circassian, or Turkish—the country’s cultural milieu remained predominantly Arab.

Recent News

Egypt eventually became one of the intellectual and cultural centres of the Arab and Islamic world , a status that was fortified in the mid-13th century when Mongol armies sacked Baghdad and ended the Abbasid caliphate . The Mamluk sultans of Egypt, under whom the country thrived for several centuries, established a pseudo-caliphate of dubious legitimacy. But in 1517 the Ottoman Empire defeated the Mamluks and established control over Egypt that lasted until 1798, when Napoleon I led a French army in a short occupation of the country.

The French occupation, which ended in 1801, marked the first time a European power had conquered and occupied Egypt, and it set the stage for further European involvement. Egypt’s strategic location has always made it a hub for trade routes between Africa, Europe , and Asia , but this natural advantage was enhanced in 1869 by the opening of the Suez Canal , connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea . The concern of the European powers (namely France and the United Kingdom , which were major shareholders in the canal) to safeguard the canal for strategic and commercial reasons became one of the most important factors influencing the subsequent history of Egypt. The United Kingdom occupied Egypt in 1882 and continued to exert a strong influence on the country until after World War II (1939–45).

In 1952 a military coup installed a revolutionary regime that promoted a combination of socialism and Pan-Arab nationalism . The new regime’s extreme political rhetoric and its nationalization of the Suez Canal Company prompted the Suez Crisis of 1956, which was only resolved by the intervention of the United States and the Soviet Union , whose presence in the Mediterranean region thereafter kept Egypt in the international spotlight.

During the Cold War , Egypt’s central role in the Arabic-speaking world increased its geopolitical importance as Arab nationalism and inter-Arab relations became powerful and emotional political forces in the Middle East and North Africa . Egypt led the Arab states in a series of wars against Israel but was the first of those states to make peace with the Jewish state, which it did in 1979.

Egypt’s authoritarian political system was long dominated by the president, the ruling party, and the security services. With opposition political activity tightly restricted, decades of popular frustration erupted into mass demonstrations in 2011. The uprising forced Pres. Hosni Mubarak to step down, leaving a council of military officers in control of the country. Power was transferred to an elected government in 2012, and a new constitution was adopted at the end of the year. This elected government, however, was toppled a year later when the military intervened to remove the newly elected president, Mohamed Morsi , a member of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood , following a series of massive public demonstrations against his administration. (For a discussion of unrest and political change in Egypt in 2011, see Egypt Uprising of 2011 .)

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus called Egypt the “gift of the Nile.” Indeed, the country’s rich agricultural productivity—it is one of the region’s major food producers—has long supported a large rural population devoted to working the land. Present-day Egypt, however, is largely urban. The capital city, Cairo , is one of the world’s largest urban agglomerations , and manufacturing and trade have increasingly outstripped agriculture as the largest sectors of the national economy. Tourism has traditionally provided an enormous portion of foreign exchange, but that industry has been subject to fluctuations during times of political and civil unrest in the region.

The world of ancient Egypt

Few civilizations have enjoyed the longevity and global cultural reach of ancient Egypt. Their distinct visual expressions, writing system, and imposing monuments are instantly recognizable by viewers all around the world even today—put simply, their branding was on point.

Pyramid of Khafre, Egypt (photo: MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite portraying significant stability over a vast period of time, their civilization was not as static as it may appear at first glance, particularly if viewed through our modern eyes and cultural perspectives . Instead, the culture was dynamic even as it revolved around a stable core of imagery and concepts. The ancient Egyptians adjusted to new experiences, constantly adding to their complex beliefs about the divine and terrestrial realms, and how they interact. This flexibility, wrapped around a base of consistency, was part of the reason ancient Egypt survived for millennia and continues to fascinate.

Read an introductory essay about ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt: an introduction

/ 1 Completed

The Natural World of Egypt

View of the Nile River, Egypt (photo: Badics, CC BY-SA 3.0)

With the blazing sun above, flanked by vast seas of shifting sand, and fed by the life-giving Nile River (which hid frightening creatures beneath its dark waters), the natural world of Egypt was inherently beautiful but also potentially deadly. Outside the lush river valley, there was little protection from the ever-dominant sun, whose intensity was both feared and revered. The deserts were home not only to many dangerous creatures, but the sands themselves were also unpredictable and constantly shifting. The clear night skies dazzled with millions of stars, some of which seemed to move of their own accord while others rose and fell at trackable intervals. The Nile, with its annual floods, brought fertility and renewal to the land, but could also overflow and wreak havoc on the villages that lined its banks. Careful observers of their environment, the Egyptians perceived divine forces in these phenomena and many of their deities, such as the powerful sun god Ra, were connected with elements from the natural world.

Hieroglyphs, detail from the White Chapel, Karnak (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The perception of divine powers existing in the natural world was particularly true in connection with the animals that inhabited the region. There was an array of creatures that the Egyptians would have observed or interacted with on a regular basis and they feature heavily in the culture. One of the most distinctive visual attributes of Egyptian imagery is the myriad deities that were portrayed in hybrid form, with a human body and animal head. In addition, a wide range of birds, fishes, mammals, reptiles, and other creatures appear prominently in the hieroglyphic script —there are dozens of different birds alone.

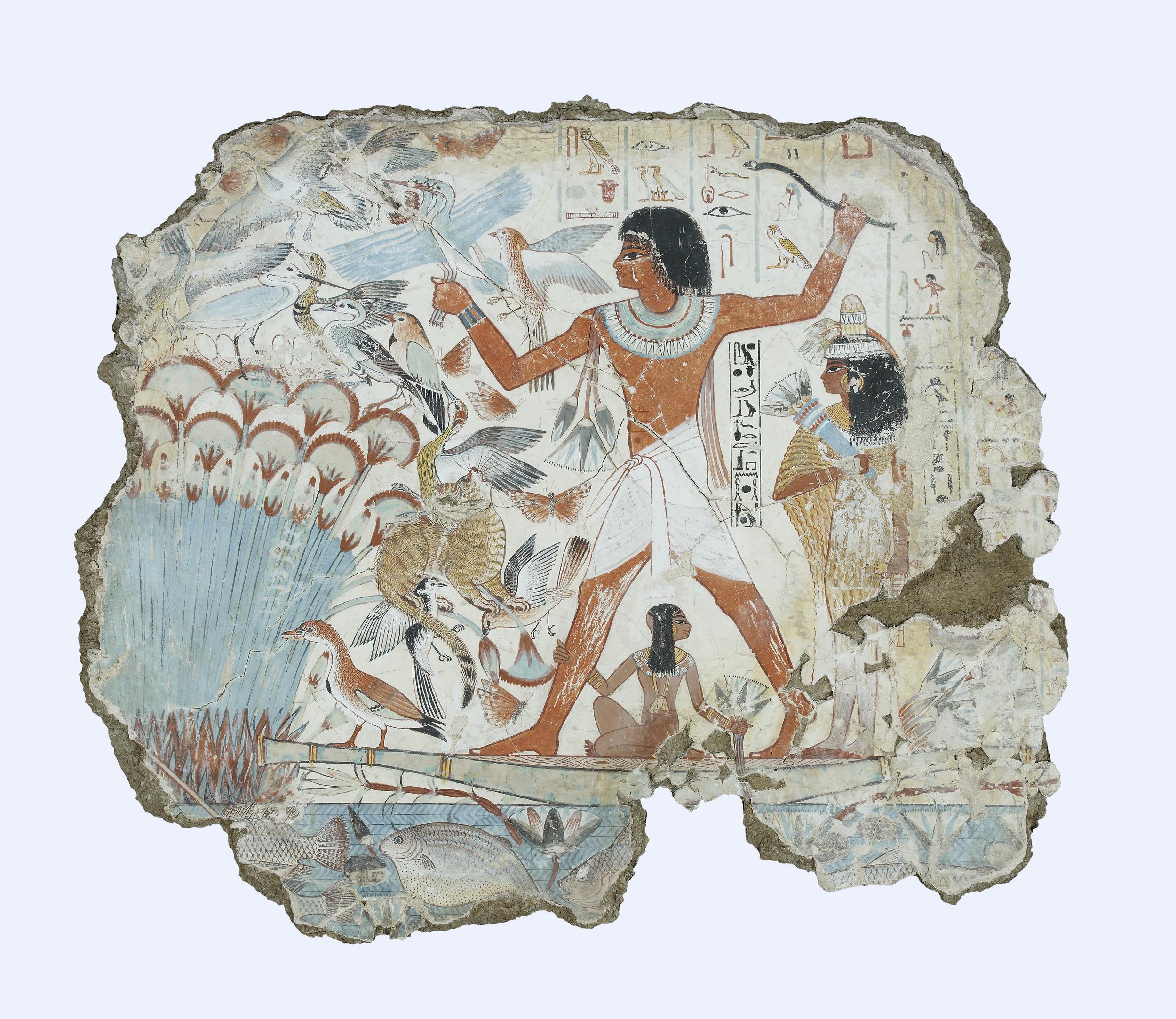

Nebamun fowling in the marshes, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, 83 x 98 cm, Thebes (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Nile was packed with numerous types of fish, which were recorded in great detail in fishing scenes that became a fixture in non-royal tombs. Most relief and painting throughout Egypt’s history was created for divine or mortuary settings and they were primarily intended to be functional. Many tomb scenes included the life-giving Nile and all it’s abundance with the goal of making that bounty available for the deceased in the afterlife. In addition to the array of fish, the river also teemed with far more dangerous animals, like crocodiles and hippopotami. Protective spells and magical gestures were used from early on to aid the Egyptians in avoiding those watery perils as they went about their daily lives.

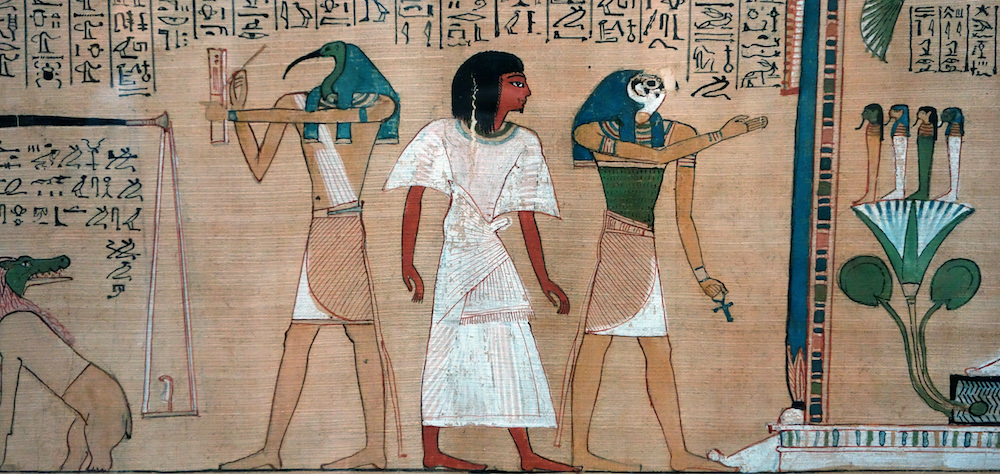

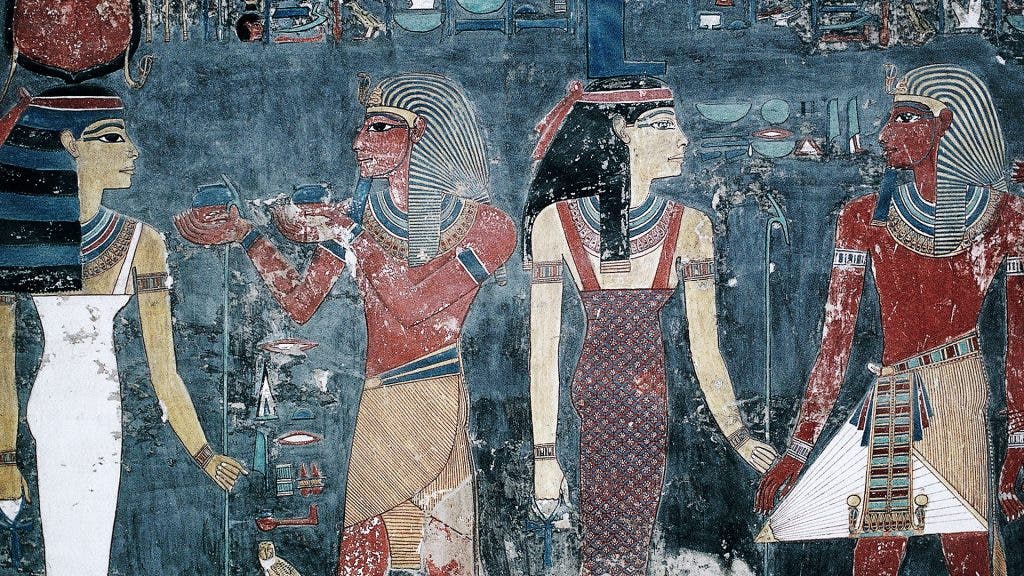

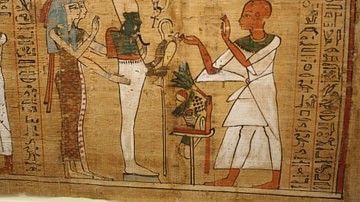

Hunefer (center) flanked by two deities: the ibis-headed Thoth (left) and the falcon-headed Horus (right), from Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead of Hunefer, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum)

The desert, likewise, was full of potentially dangerous creatures. Lions, leopards, jackals, cobras, and scorpions were all revered for their attributes and feared for their ferocity. Soaring above were birds of prey, like falcons who were sharp-eyed hunters, and massive vultures that consumed decaying flesh and fed it to their young. Scarab beetles also seemingly brought new life from decay and the sacred ibis with their curved beaks found sustenance hidden in the muddy banks of the Nile. All of these creatures (and many others) became closely associated with different deities very early in Egyptian history. The Egyptians did not worship animals; instead, certain animals were revered because it was believed that they were related to particular gods and thus served as earthly manifestations of those deities.

Model scene of workers ploughing a field, Middle Kingdom, late Dynasty 11, 2010–1961 B.C.E., wood, 54 cm (MFA Boston)

Even domesticated animals, such as cows, bulls, rams, and geese, became associated with deities and were viewed as vitally important. Cattle were probably the first animals to be domesticated in Egypt and domesticated cattle, donkeys, and rams appear along with wild animals on Predynastic and Early Dynastic votive objects , showing massive herds that were controlled by early rulers, demonstrating their wealth and prestige. Pastoral scenes of animal husbandry appear in numerous private tomb chapels and wooden models, providing detailed evidence of their daily practices. Herdsmen appear caring for their animals in depictions that include milking, calving, protecting the cattle as they cross the river, feeding, herding, and many other aspects of their day-to-day care.

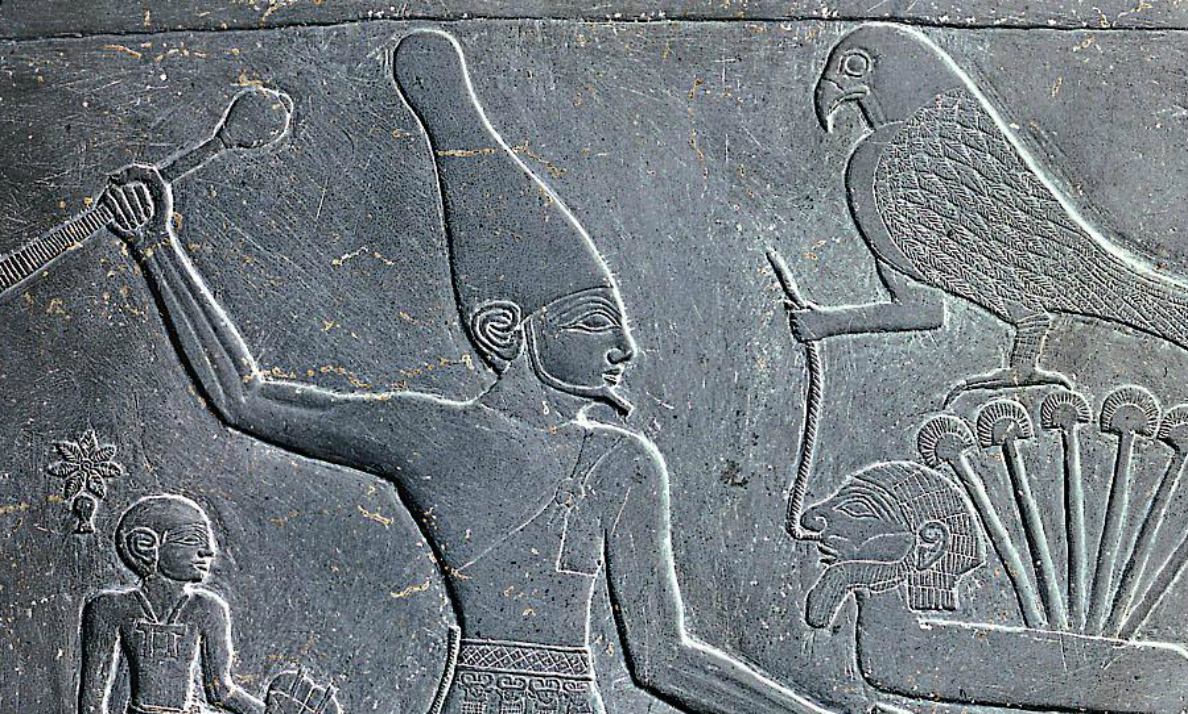

The Battlefield Palette , c. 3100 B.C.E., mudstone, found at el-Amarna, Egypt, 19.6 x 32.8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Already in the Predynastic period the king was linked with the virile wild bull, an association that continues throughout Egyptian history—one of the primary items of royal regalia was a bull tail, which appears on a huge number of pharaonic images. An early connection between the king and lions is also apparent. One scene on a Predynastic ceremonial palette ( The Battlefield Palette), shows the triumphant king as a massive lion devouring his defeated foes. First Dynasty kings appear to have kept lion cubs as pets.

The Great Sphinx (photo: superblinkymac, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In addition, lions (among other animals) were associated with the burials of some early rulers. One of the most iconic images from ancient Egypt is the massive Great Sphinx at Giza, which was sculpted from the living rock of the plateau. This fused form, with the body of a lion and the head of the king, became a common visual expression of royal power.

Historical Setting

While many of the religious and cultural characteristics of ancient Egypt were evident from very early on and continued all the way through the Roman era (contributing to overall cultural stability), sweeping conceptual developments and adoptions of external elements are also evident. Throughout ancient Egypt’s long history, periods of unified control were interspersed with moments of instability where parts of the country were controlled by different authorities. These repeated waves of political and cultural development create a decidedly complex history that spans thousands of years.

Read essays to understand the historical setting and basic characteristics of each era

Ancient Egyptian chronology and historical framework: an introduction

Predynastic and Early Dynastic: an introduction

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period: an introduction

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period: an introduction

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period: an introduction

Late Period and the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods: an introduction

/ 6 Completed

Social Organization

Conceptually, the Egyptian state was an absolute monarchy where the office of pharaoh itself was considered divine. The pharaoh (king) was viewed as the earthly manifestation of the god Horus, and was responsible as the supreme commander for making all decisions affecting the nation. In reality, the king stood at the head of a hierarchical administrative structure with layers of civil officials that oversaw various systems and were responsible to the king for their success.

Seated Scribe , c. 2500 B.C.E., c. 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, painted limestone with rock crystal, magnesite, and copper/arsenic inlay for the eyes and wood for the nipples, found in Saqqara (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most Egyptians followed the careers of their fathers and were taught by apprenticeship. Only the children of the higher classes, destined to become officials, were taught in schools and learned to read and write. Money in the modern sense did not exist in Egypt until the mid-fourth century B.C.E., so wages were usually paid in grain that could then be exchanged for copper or silver. Agriculture was the basis of the Egyptian economy and the foundation of the state, and produce was delivered to central storehouses to be administered and distributed.

Read essays about the various social strata in Egyptian society

Egyptian Social Organization: The Pharaoh

Egyptian Social Organization: Administrative officials, priests, ranks of the military, and the general population

/ 2 Completed

Art and Function

Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut , c. 1479–1458 B.C.E., Dynasty 18, New Kingdom (Deir el-Bahri, Upper Egypt), granite, 261.5 x 80 x 137 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Egyptian art is sometimes viewed as static and abstract when compared with the more naturalistic depictions of other cultures (ancient Greece for example). Much of Egyptian imagery—especially royal imagery—was governed by decorum (a sense of what was appropriate), and remained extraordinarily consistent throughout its long history. This is why their art may appear unchanging—and this was intentional. For the ancient Egyptians, consistency was a virtue and an expression of political stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of ma’at and the correctness of their culture. The Egyptians even had a tendency, especially after periods of disunion, towards archaism where the artistic style would revert to that of the earlier Old Kingdom which was perceived as a “golden age.”

Read essays about art and function

Ancient Egyptian art: an introduction its function and basic characteristics

Materials and techniques in ancient Egyptian art: an introduction

Consistency and balance

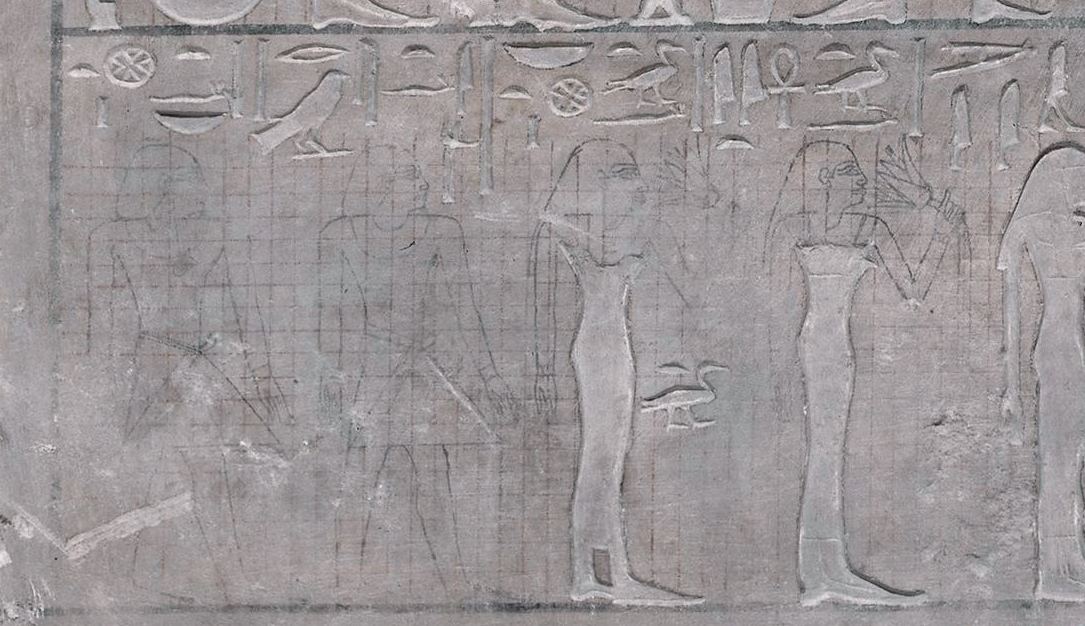

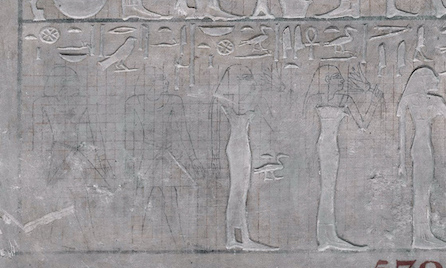

The canon of proportions grid is clearly visible in the lower, unfinished register of the Stela of Userwer, and the use of hieratic scale (where the most important figures are largest) is evident the second register that shows Userwer, his wife and his parents seated and at a larger scale than the figures offering before them. Detail of the stela of the sculptor Userwer, 12th dynasty, limestone, from Egypt, 52 x 48 cm wide (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Consistency in representation was closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself. This belief led to an active resistance to changes in codified depictions. Even the way that figures were planned and laid out by the artists was codified. During the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians developed a grid system, referred to as the canon of proportions, for creating systematic figures with the same proportions. Grid lines aligned with the top of the head, top of the shoulder, waist, hips, knees, and bottom of the foot (among other body joints).

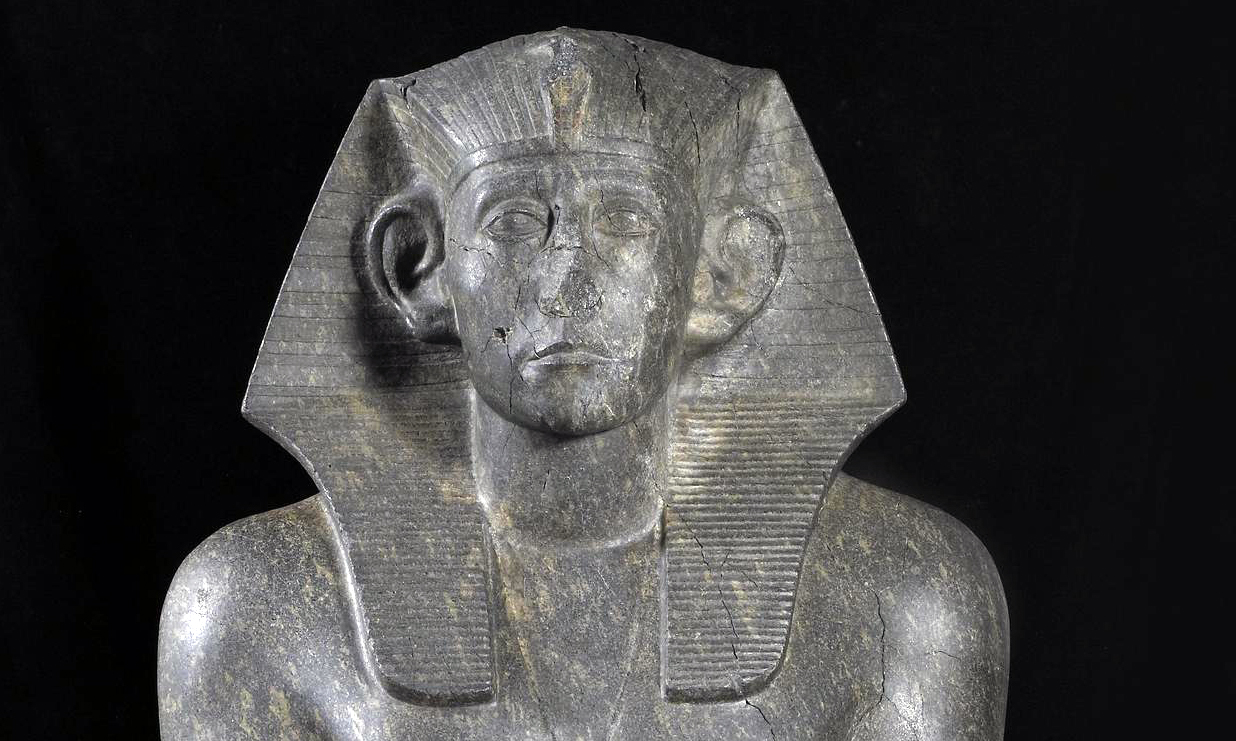

King Menkaura (Mycerinus) and Queen, 2490–2472 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4, greywacke, Menkaura Valley Temple, Giza, Egypt, 142.2 x 57.1 x 55.2 cm, 676.8 kg (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The grid aided the artist in ensuring that the proportions of their figures were correct, but those proportions shifted over time. For example, although 18 squares was the standard used for much of Egypt’s history, in the Amarna period 20 squares were used, resulting in figures with more elongated proportions.

Thutmose, Model Bust of Queen Nefertiti , c. 1340 BCE, limestone and plaster, New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, Amarna Period (Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection/Neues Museum, Berlin)

Below are several examples of Egyptian art that demonstrate their primary stylistic characteristics. These include:

- the use of hierarchical scale

- the use of registers

- use of the canon of proportions (described above)

- a preference for balance

- the integration of perspectives.

Read essays and watch videos about consistency and balance

Stela of the sculptor Userwer: The lower part is still covered with the grid used for ensuring that the proportions of the figures were correct.

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen: They both look beyond the present and into timeless eternity, their otherworldly visage displaying no human emotion whatsoever.

Thutmose, Model Bust of Queen Nefertiti : This stunning bust exemplifies a change in style.

The Seated Scribe: This painted statue differs from the ideal statues of pharaohs.

/ 4 Completed

Creative details

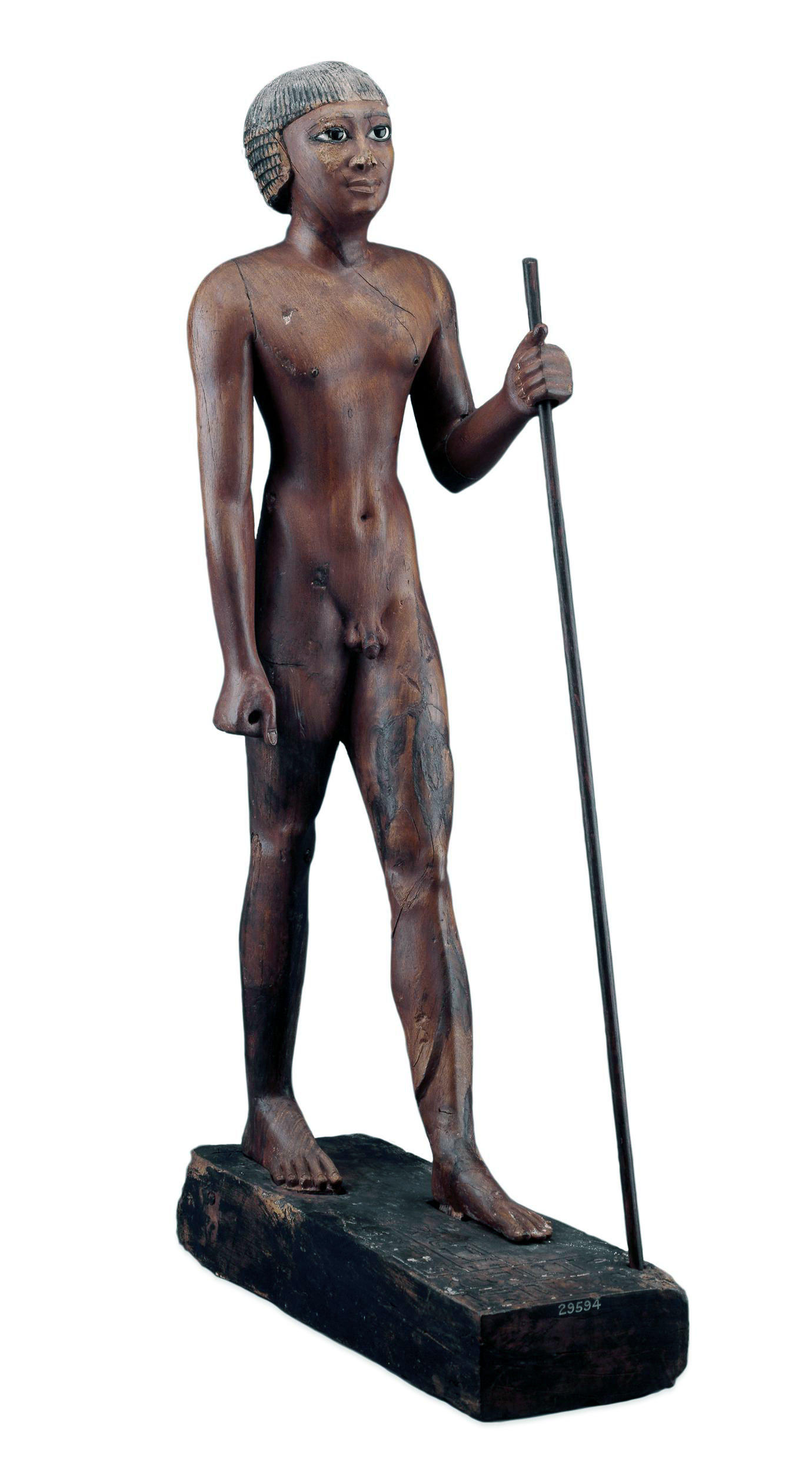

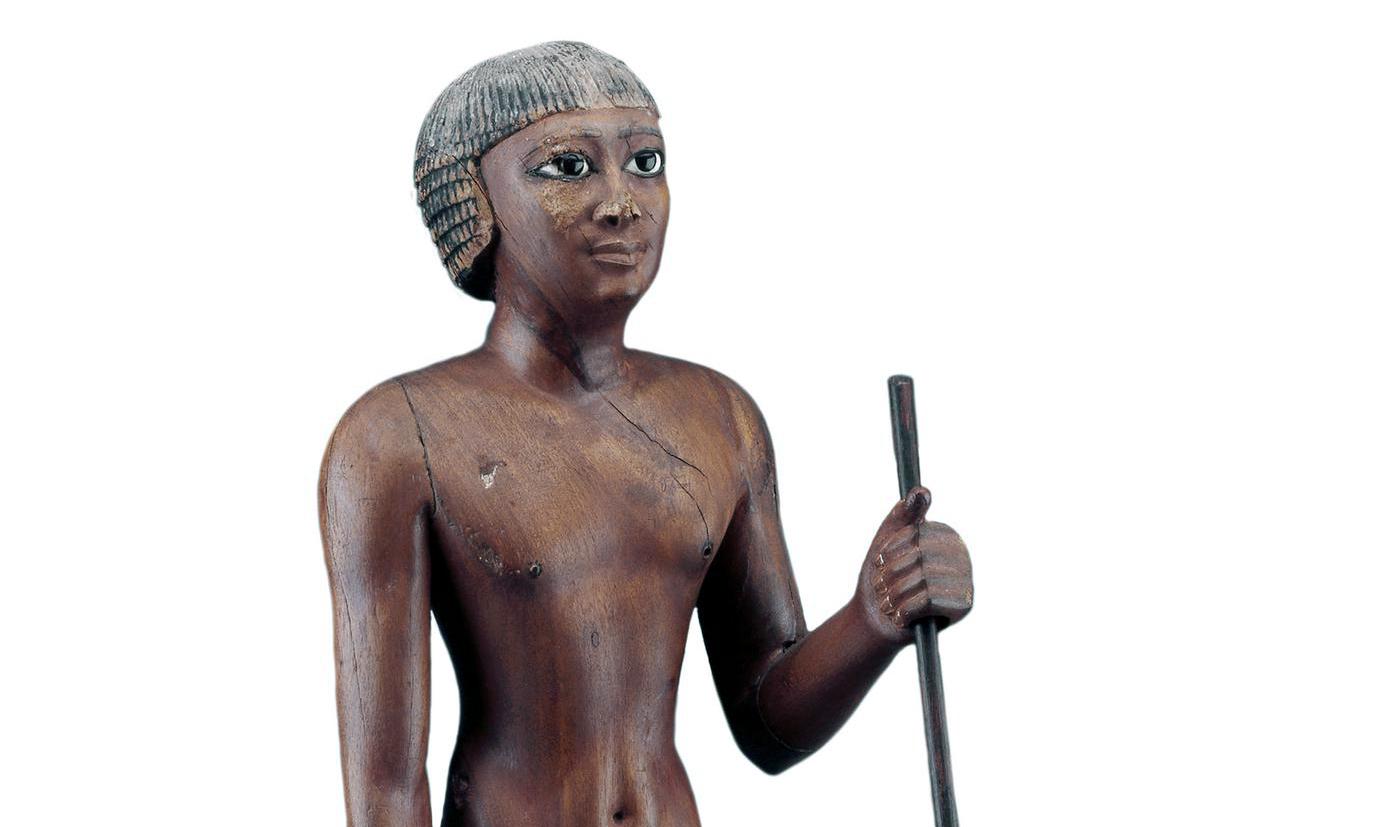

Nude figure of the Seal Bearer Tjetji, 2321 B.C.E.–2184 B.C.E. (6th Dynasty), from Akhmim, Upper Egypt, wood, obsidian, limestone, and copper, 75 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Although much Egyptian art is formal, many surviving examples of highly expressive depictions full of creative details prove that the ancient Egyptian artists were fully capable of naturalistic representations. Note, for example, the sensitive modeling of the musculature and close attention paid to realistic physical detail evident in a wood statue of a high official (the Seal Bearer Tjetji) from a Late Old Kingdom tomb. These very unusual and enigmatic statuettes of nude high officials, which are depicted in a standard pose of striding forward with left leg advanced and holding a long staff, were often painted and had eyes of inlaid stone set in copper.

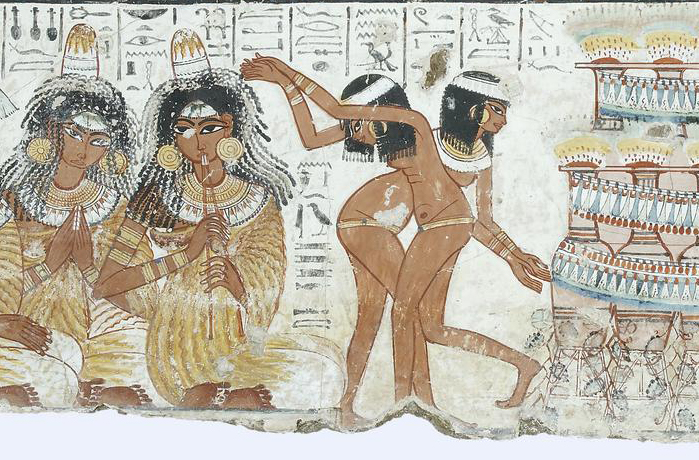

Musicians and dancers (detail), A feast for Nebamun, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, whole fragment: 88 x 119 cm, Thebes © Trustees of the British Museum

Nebamun’s tomb, with its spectacular paintings, includes several examples that demonstrate a careful observation of the natural world—especially notable in the energetic hunting cat and the sinuous dancing of the entertainers at the banquet. A marvelous wooden head of Queen Tiye presents a woman of strong personality with details that hint at her formidable character.

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye with a Crown of Two Feathers , c. 1355 B.C.E., Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, New Kingdom, Egypt, yew wood, lapis lazuli, silver, gold, faience, 22.5 cm high (Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection at the Neues Museum, Berlin)

Read essays about creative details

Wooden tomb statue of Tjeti: T he sculptor of this example has carefully modeled the muscles on the torso and legs, and paid close attention to the detail of the face.

Paintings from the Tomb-chapel of Nebamun: He is shown hunting birds from a small boat in the marshes of the Nile with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter.

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye: She was a powerful figure, but her royal life was complicated, as demonstrated through this changing statue.

/ 3 Completed

Metalworking Traditions

Scene showing the manufacture of valuable items, such as jewelry. Wall-painting, probably from the tomb of Sobekhotep, Thebes, c. 1400 B.C.E., New Kingdom, reign of Thutmose IV, painted stucco, 60 x 58.5 (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Egyptian artisans were highly skilled metalworkers from early times; although few metal sculptures have survived, those that are preserved show an incredible level of technical achievement. As with other types of craft, like woodworking, preserved images of artisans in their workshops found in private tombs provide information about the processes of production For instance, we can see a group of jewelers at work in a painting from the tomb of Sebekhotep.

Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet with the Name of Senwosret II, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret II, c. 1887–1878 B.C.E., Egypt, Fayum Entrance Area, el-Lahun (Illahun, Kahun; Ptolemais Hormos), Tomb of Sithathoryunet (BSA Tomb 8), EES 1914, Gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, lapis lazuli

The most beautifully crafted pieces of jewelry display elegant designs, incredible intricacy, and astonishingly precise stone-cutting and inlay, reaching a level that modern jewelers would be hard-pressed to achieve. The jewelry of a Middle Kingdom princess, found in her tomb at el-Lahun in the Fayum region is one spectacular example.

Statuette of Thutmose IV, 1400–1390 B.C.E., 19th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, bronze, silver, calcite, 14.7 x 6.4 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The metal statues that survive demonstrate a high level of skill in both sheet working/metal forming and casting in copper and bronze. This marvelous hollow-cast bronze statuette of a kneeling Thutmosis IV, presenting an offering of wine, provides a peek into the abilities of Egypt’s craftsmen. Note that the arms were created separately and joined to the body on tenons and the eyes were originally inlaid.

Read essays and watch a video about metalworking traditions

Paintings from the tomb of Sebekhotep: Images show jewelers at work.

Pectoral and necklace of Sithathoryunet: Fashioned delicately in gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, and lapis lazuli.

Bronze statuette of Thutmose IV: Very few metal statues survive that date from before the Late Period, though the Egyptians did have the technology to make large copper statues as early as the Old Kingdom.

This brief glimpse at the world of ancient Egypt is just a springboard for gaining an understanding of this compelling and complex culture.

A final note

The wonder of the internet is the astonishing access to information; one of the big problems with the internet is that anyone, regardless of knowledge or training, can post whatever they like and that information is presented at the same level as content put out by the experienced and trained. Information about ancient Egypt should always come from a well-vetted source, as there is a great deal of misinformation. The culture is astonishing enough on its own. Egypt remains highly influential across different areas of culture and vast swaths of time and space—Egyptian glass beads have been excavated in Viking tombs and revivals of Egyptian style still happen on an almost cyclical basis, even millenia later. We are surrounded by Egyptian imagery and concepts even if we don’t realize it; those emojis we use with such abandon are decidedly hieroglyphic. The more we know about what came before, the better we can grasp everything that has happened since. Only by understanding the past can we really envision the possibilities of the present and plan for the future.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the annual flooding of the nile help form the egyptian view of the world, how might the regular behavior of certain animals—like falcons, vultures, snakes, and scarab beetles— suggest "heavenly wisdom" to the careful observer, how would you want to be depicted for eternity what identifying symbols would you want to include, terms to know and use.

canon of proportions

hierarchical scale

Need teaching images? Here is a Google Slideshow with many of the primary images in this chapter

Read a chapter about Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife

Collaborators

Dr. Amy Calvert

Dr. Beth Harris

Dr. Steven Zucker

The British Museum

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Ancient Egypt

Egypt was a vast kingdom of the ancient world. It was unified around 3100 B.C.E. and lasted as a leading economic and cultural influence throughout North Africa and parts of the Levant until it was conquered by the Macedonians in 332 B.C.E.

Anthropology, Archaeology, Social Studies, Ancient Civilizations, World History

Ancient Egypt

Uncover the secrets of one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

It’s the year 2490 B.C. Wooden boats cruise along the Nile River in Egypt as thousands of workers stack giant stone blocks into a pyramid. This 200-foot-tall structure honors a pharaoh named Menkaure. This pharaoh’s father, Khafre, ordered construction of a 450-foot-high pyramid nearby, and his grandfather Khufu built the Great Pyramid at Giza—the largest of the three—at about 480 feet. Covered in polished white limestone, the pyramids seem to glow in the sunlight.

The Egyptians working on the pyramids are helping create a culture that will last more than 3,000 years—it will be one of the longest-lasting civilizations in the world. During that time, ancient Egyptians created works of art and engineering that still amaze us today.

History of ancient Egypt

People settled in Egypt as early as 6000 B.C. Over time, small villages joined together to become states until two kingdoms emerged: Lower Egypt, which covers the Nile River Delta up to the Mediterranean Sea in the north, and Upper Egypt, which covers the Nile Valley in the south. (The Nile River flows from south to north, so for the ancient Egyptians, the southern part of the country was "up.")

Around 3100 B.C., a king (later called a pharaoh) united these two lands to be one country, and so historians begin the long history of ancient Egypt here, dividing it into different periods. (They don’t always know the exact date of historical events. So that’s why you’ll see a "ca" next to some of the years. It stands for "circa" meaning "around.")

Early Dynastic Period, about 525 years (ca 3100 B.C. to ca 2575 B.C.): These early pharaohs worked to keep the two lands under their control. To do this, they claimed they were being watched over by the falcon god Horus, and so the people of Egypt should respect them. They also used record keeping in the form of hieroglyphic writing to record things like royal decrees and the taxes that the people paid in the form of grain. (A dynasty is a series of rulers from the same family.)

Old Kingdom, about 425 years (ca 2575 B.C. to ca 2150 B.C.): By this time, the pharaohs had enough power and wealth to build pyramids in their honor; that’s why the Old Kingdom is sometimes called the “Age of the Pyramids.” The pharaohs at this time were mostly associated with the sun god Ra, a tradition that would remain for much of Egypt’s history.

First Intermediate Period, about 200 years (ca 2130 B.C. to ca 1938 B.C.): These pharaohs lost power after drought hit Egypt. Instead, local leaders took control of their own communities, and they stopped passing along grain to the central government. Eventually, these local rulers formed independent states.

Middle Kingdom, about 300 years (ca 1938 B.C. to ca 1630 B.C.): Around 1938 B.C., Mentuhotep II reunited the country and began an era known for producing some of Egypt’s greatest pieces of art. For the first time, Egyptians wrote stories for entertainment, and pharaohs started construction of Karnak Temple in the modern-day city of Luxor.

Second Intermediate Period, about 90 years (ca 1630 B.C. to ca 1540 B.C.): Weak pharaohs again lost control. Invaders from western Asia called Hyksos ruled in the north; people from Kush, a kingdom south of Egypt, took control in Upper Egypt.

New Kingdom, about 465 years (ca 1540 B.C. to 1075 B.C.): Egyptians took back control and crowned some of Egypt’s most well-known rulers: The female pharaoh Hatshepsut ruled for 21 years; Akhenaten tried to start a new religion, and his son, the boy king Tutankhamun , reigned for 10 years. Ramses II built more monuments to himself than any other pharaoh. This was ancient Egypt's most prosperous and powerful period.

Third Intermediate Period, about 420 years (ca 1075 B.C. to ca 656 B.C.): This was a time of drought, famine, and foreign invasions. But some pharaohs thrived. Although King Taharqa was a foreign ruler from Kush, a kingdom south of Egypt, he repaired crumbling temples and even began building pyramids again for the first time in about 800 years.

Late Period, about 300 years (ca 656 B.C. to 332 B.C.): This period marks the last time that ancient Egypt was ruled by native Egyptians. Leading an army from Persia (what is now Iran), King Darius I took control.

Macedonian and Ptolemaic Egypt, about 300 years (332 B.C. to 30 B.C.): In 332 B.C., Alexander the Great conquered the ruling Persians, then gave control to the Greek general Ptolemy I Soter. From then on, Egypt was ruled by Greek pharaohs. The last one, Cleopatra VII, lost a war to the Roman ruler Octavian . Egypt would be under Roman rule for the next 600 years.

Life in ancient Egypt

Most people in ancient Egypt were farmers. They lived with their families in houses made of mud bricks that were near the Nile River.

The Nile flooded each year, leaving behind fertile soil for planting crops like wheat, barley, lettuce, flax, and papyrus. As the Egyptians learned how to move river water to their fields, they were able to grow more food, including grapes, apricots, olives, and beans.

During flood season, farmers couldn’t tend their crops. So instead, some worked building pyramids, tombs, and monuments. Other people worked as scribes (people who recorded events), priests, and doctors.

Women in ancient Egypt had more freedom than those in other ancient cultures. Like men, they could be scribes, priests, and doctors, and they usually had the same rights as men. Women could own their own homes and businesses.

Ancient Egyptians also like to have fun! They swam and canoed in the Nile, played board games, and they enjoyed making music and dancing.

The afterlife

In fact, Egyptians enjoyed life so much that they believed that the afterlife would be almost exactly the same—except without things like sadness, illness, or pesky mosquitoes. Even pets like cats, dogs, or monkeys would join them there.

Being mummified—the process of preserving a body—was an important part of how Egyptians believed their soul would enter the afterlife. So were tombs. These burial chambers were filled with things a person would need there: food, games, and even underwear!

According to legend, ancient Egyptian gods also helped people in the afterlife. Some, like the jackal-headed god Anubis, helped guide people to the underworld, where they would be judged by its ruler, the god Osiris.

Egyptians believed other gods helped them in real life, too. For instance, Osiris’s wife, the goddess Isis, helped cure human sickness, and the goddess Tefnut caused the rain to fall.

Pyramid power

Click through this gallery to see how the pyramid developed over time.

Why ancient Egypt still matters

Today, millions of tourists visit the country of Egypt each year to see the pyramids, tombs, and temples. But these monuments aren’t all this ancient culture left behind.

Ancient Egyptian astronomers created a calendar much like ours—based on the sun’s rotation—and are thought to be the first civilization to measure a year using 365 days. They were also math geniuses: Historians think that division and multiplication were first developed by these people. (Plus, how else would they have figured out how to build pyramids without a lot of math?)

This was also one of the first civilizations to have a written language using a system called hieroglyphic writing, in which symbols—not letters—represent words or sounds. (These people even created writing sheets out of a plant called papyrus.) Hieroglyphs are carved into most temples and tombs to record names and dates, describe events like battles, and give instructions for passing on to the afterlife.

- The ancient Egyptians worshipped over 2,000 gods and goddesses.

- Cleopatra, Egypt’s last pharaoh, lived closer to our time than to the building of the Pyramids at Giza.

- Ancient Egyptian bakers sometimes kneaded bread dough with their feet.

- These ancient people often referred to their pet cats as miu. (Sound familiar?)

- Ancient Egyptians called their homeland Kemet, meaning “black land.” It refers to the dark, fertile soil left behind after flooding from the Nile River.

Read This Next

Ancient rome, the discovery of king tut’s tomb, maze: egypt.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Egyptian Pyramids

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 15, 2024 | Original: October 14, 2009

Built during a time when Egypt was one of the richest and most powerful civilizations in the world, the pyramids—especially the Great Pyramids of Giza—are some of the most magnificent man-made structures in history. Their massive scale reflects the unique role that the pharaoh, or king, played in ancient Egyptian society. Though pyramids were built from the beginning of the Old Kingdom to the close of the Ptolemaic period in the fourth century A.D., the peak of pyramid building began with the late third dynasty and continued until roughly the sixth (c. 2325 B.C.). More than 4,000 years later, the Egyptian pyramids still retain much of their majesty, providing a glimpse into the country’s rich and glorious past.

The Pharaoh in Egyptian Society

During the third and fourth dynasties of the Old Kingdom, Egypt enjoyed tremendous economic prosperity and stability. Kings held a unique position in Egyptian society. Somewhere in between human and divine, they were believed to have been chosen by the gods themselves to serve as their mediators on earth. Because of this, it was in everyone’s interest to keep the king’s majesty intact even after his death, when he was believed to become Osiris, god of the dead. The new pharaoh, in turn, became Horus, the falcon-god who served as protector of the sun god, Ra.

Did you know? The pyramid's smooth, angled sides symbolized the rays of the sun and were designed to help the king's soul ascend to heaven and join the gods, particularly the sun god Ra.

Ancient Egyptians believed that when the king died, part of his spirit (known as “ka”) remained with his body. To properly care for his spirit, the corpse was mummified, and everything the king would need in the afterlife was buried with him, including gold vessels, food, furniture and other offerings. The pyramids became the focus of a cult of the dead king that was supposed to continue well after his death. Their riches would provide not only for him, but also for the relatives, officials and priests who were buried near him.

The Early Pyramids

From the beginning of the Dynastic Era (2950 B.C.), royal tombs were carved into rock and covered with flat-roofed rectangular structures known as “mastabas,” which were precursors to the pyramids. The oldest known pyramid in Egypt was built around 2630 B.C. at Saqqara, for the third dynasty’s King Djoser. Known as the Step Pyramid, it began as a traditional mastaba but grew into something much more ambitious. As the story goes, the pyramid’s architect was Imhotep, a priest and healer who some 1,400 years later would be deified as the patron saint of scribes and physicians. Over the course of Djoser’s nearly 20-year reign, pyramid builders assembled six stepped layers of stone (as opposed to mud-brick, like most earlier tombs) that eventually reached a height of 204 feet (62 meters); it was the tallest building of its time. The Step Pyramid was surrounded by a complex of courtyards, temples and shrines where Djoser could enjoy his afterlife.

After Djoser, the stepped pyramid became the norm for royal burials, although none of those planned by his dynastic successors were completed (probably due to their relatively short reigns). The earliest tomb constructed as a “true” (smooth-sided, not stepped) pyramid was the Red Pyramid at Dahshur, one of three burial structures built for the first king of the fourth dynasty, Sneferu (2613-2589 B.C.) It was named for the color of the limestone blocks used to construct the pyramid’s core.

The Great Pyramids of Giza

No pyramids are more celebrated than the Great Pyramids of Giza, located on a plateau on the west bank of the Nile River, on the outskirts of modern-day Cairo. The oldest and largest of the three pyramids at Giza, known as the Great Pyramid , is the only surviving structure out of the famed Seven Wonders of the Ancient World . It was built for Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops, in Greek), Sneferu’s successor and the second of the eight kings of the fourth dynasty. Though Khufu reigned for 23 years (2589-2566 B.C.), relatively little is known of his reign beyond the grandeur of his pyramid. The sides of the pyramid’s base average 755.75 feet (230 meters), and its original height was 481.4 feet (147 meters), making it the largest pyramid in the world. Three small pyramids built for Khufu’s queens are lined up next to the Great Pyramid, and a tomb was found nearby containing the empty sarcophagus of his mother, Queen Hetepheres. Like other pyramids, Khufu’s is surrounded by rows of mastabas, where relatives or officials of the king were buried to accompany and support him in the afterlife.

The middle pyramid at Giza was built for Khufu’s son Pharaoh Khafre (2558-2532 B.C). The Pyramid of Khafre is the second tallest pyramid at Giza and contains Pharaoh Khafre’s tomb. A unique feature built inside Khafre’s pyramid complex was the Great Sphinx, a guardian statue carved in limestone with the head of a man and the body of a lion. It was the largest statue in the ancient world, measuring 240 feet long and 66 feet high. In the 18th dynasty (c. 1500 B.C.) the Great Sphinx would come to be worshiped itself, as the image of a local form of the god Horus. The southernmost pyramid at Giza was built for Khafre’s son Menkaure (2532-2503 B.C.). It is the shortest of the three pyramids (218 feet) and is a precursor of the smaller pyramids that would be constructed during the fifth and sixth dynasties.

Who Built The Pyramids?

Though some popular versions of history held that the pyramids were built by slaves or foreigners forced into labor, skeletons excavated from the area show that the workers were probably native Egyptian agricultural laborers who worked on the pyramids during the time of year when the Nile River flooded much of the land nearby. Approximately 2.3 million blocks of stone (averaging about 2.5 tons each) had to be cut, transported and assembled to build Khufu’s Great Pyramid. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that it took 20 years to build and required the labor of 100,000 men, but later archaeological evidence suggests that the workforce might actually have been around 20,000.

10 Awe‑Inspiring Photos of the Ancient Pyramids of Egypt

From the early step pyramids to the towering Great Pyramids of Giza, the tombs are among the few surviving wonders of the ancient world.

How Did Egyptians Build the Pyramids? Ancient Ramp Find Deepens Mystery

The discovery of a 4,500‑year‑old ramp offers clues about Egyptians' technological knowledge.

Ancient Egypt’s 10 Most Jaw‑Dropping Discoveries

From King Tut's tomb to the pyramids, here are the greatest archaeological finds from Egypt.

The End of the Pyramid Era

Pyramids continued to be built throughout the fifth and sixth dynasties, but the general quality and scale of their construction declined over this period, along with the power and wealth of the kings themselves. In the later Old Kingdom pyramids, beginning with that of King Unas (2375-2345 B.C), pyramid builders began to inscribe written accounts of events in the king’s reign on the walls of the burial chamber and the rest of the pyramid’s interior. Known as pyramid texts, these are the earliest significant religious compositions known from ancient Egypt.

The last of the great pyramid builders was Pepy II (2278-2184 B.C.), the second king of the sixth dynasty, who came to power as a young boy and ruled for 94 years. By the time of his rule, Old Kingdom prosperity was dwindling, and the pharaoh had lost some of his quasi-divine status as the power of non-royal administrative officials grew. Pepy II’s pyramid, built at Saqqara and completed some 30 years into his reign, was much shorter (172 feet) than others of the Old Kingdom. With Pepy’s death, the kingdom and strong central government virtually collapsed, and Egypt entered a turbulent phase known as the First Intermediate Period. Later kings, of the 12th dynasty, would return to pyramid building during the so-called Middle Kingdom phase, but it was never on the same scale as the Great Pyramids.

The Pyramids Today

Tomb robbers and other vandals in both ancient and modern times removed most of the bodies and funeral goods from Egypt’s pyramids and plundered their exteriors as well. Stripped of most of their smooth white limestone coverings, the Great Pyramids no longer reach their original heights; Khufu’s, for example, measures only 451 feet high. Nonetheless, millions of people continue to visit the pyramids each year, drawn by their towering grandeur and the enduring allure of Egypt’s rich and glorious past.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From Egypt to Greece, explore fascinating documentaries about the ancient world.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Ancient Egyptian Literature

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

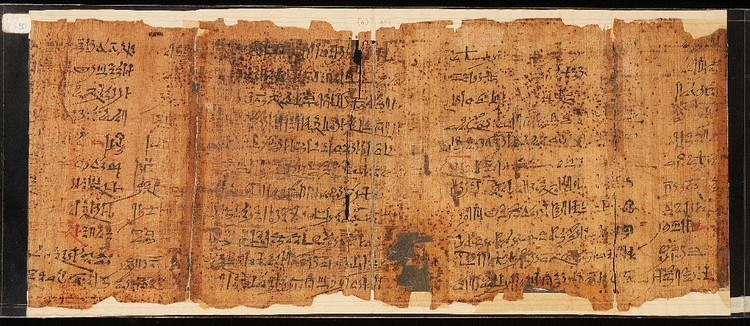

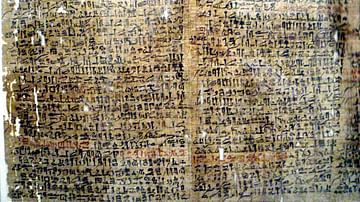

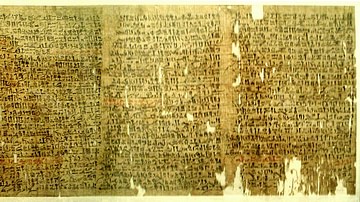

Ancient Egyptian Literature comprises a wide array of narrative and poetic forms including inscriptions on tombs, stele, obelisks, and temples; myths, stories, and legends; religious writings; philosophical works; wisdom literature; autobiographies; biographies; histories; poetry; hymns; personal essays; letters and court records.

Although many of these forms are not usually defined as "literature" they are given that designation in Egyptian studies because so many of them, especially from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), are of such high literary merit. The first examples of Egyptian writing come from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) in the form of Offering Lists and autobiographies; the autobiography was carved on one's tomb along with the Offering List to let the living know what gifts, and in what quantity, the deceased was due regularly in visiting the grave .

Since the dead were thought to live on after their bodies had failed, regular offerings at graves were an important consideration; the dead still had to eat and drink even if they no longer held a physical form. From the Offering List came the Prayer for Offerings , a standard literary work which would replace the Offering List, and from the autobiographies grew the Pyramid Texts which were accounts of a king's reign and his successful journey to the afterlife; both these developments took place during the period of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-c.2181 BCE).

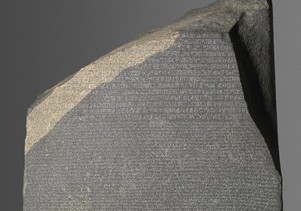

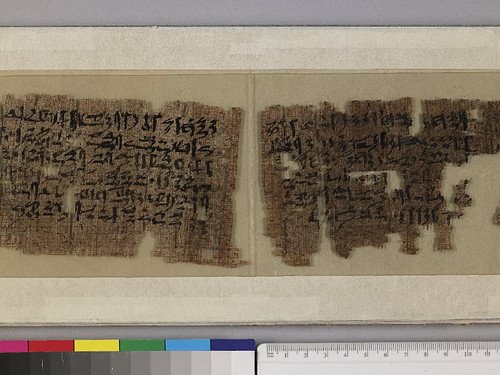

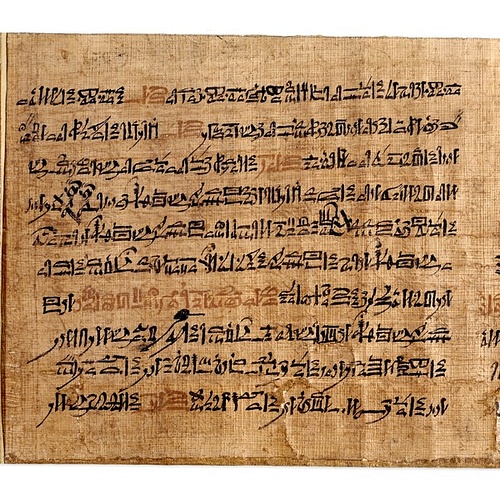

These texts were written in hieroglyphics ("sacred carvings") a writing system combining phonograms (symbols which represent sound), logograms (symbols representing words), and ideograms (symbols which represent meaning or sense). Hieroglyphic writing was extremely labor intensive and so another script grew up beside it known as hieratic ("sacred writings") which was faster to work with and easier to use.

Hieratic was based on hieroglyphic script and relied on the same principles but was less formal and precise. Hieroglyphic script was written with particular care for the aesthetic beauty of the arrangement of the symbols; hieratic script was used to relay information quickly and easily. In c. 700 BCE hieratic was replaced by demotic script ("popular writing") which continued in use until the rise of Christianity in Egypt and the adoption of Coptic script c. 4th century CE.

Most of Egyptian literature was written in hieroglyphics or hieratic script; hieroglyphics were used on monuments such as tombs, obelisks, stele, and temples while hieratic script was used in writing on papyrus scrolls and ceramic pots. Although hieratic, and later demotic and Coptic, scripts became the common writing system of the educated and literate, hieroglyphics remained in use throughout Egypt's history for monumental structures until it was forgotten during the early Christian period.

Although the definition of "Egyptian Literature" includes many different types of writing, for the present purposes attention will mostly be paid to standard literary works such as stories, legends, myths, and personal essays; other kinds or work will be mentioned when they are particularly significant. Egyptian history, and so literature, spans centuries and fills volumes of books; a single article cannot hope to treat of the subject fairly in attempting to cover the wide range of written works of the culture .

Literature in the Old Kingdom

The Offering Lists and autobiographies, though not considered "literature", are the first examples of the Egyptian writing system in action. The Offering List was a simple instruction, known to the Egyptians as the hetep -di- nesw ("a boon given by the king"), inscribed on a tomb detailing food, drink, and other offerings appropriate for the person buried there. The autobiography, written after the person's death , was always inscribed in the first person as though the deceased were speaking. Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim writes:

The basic aim of the autobiography - the self-portrait in words - was the same as that of the self-portrait in sculpture and relief: to sum up the characteristic features of the individual person in terms of his positive worth and in the face of eternity. (4)

These early obituaries came to be augmented by a type of formulaic writing now known as the Catalogue of Virtues which grew from "the new ability to capture the formless experiences of life in the enduring formulations of the written word" (Lichtheim, 5). The Catalogue of Virtues accentuated the good a person had done in his or her life and how worthy they were of remembrance. Lichtheim notes that the importance of the Virtues was that they "reflected the ethical standards of society" while at the same time making clear that the deceased had adhered to those standards (5). Some of these autobiographies and lists of virtues were brief, inscribed on a false door or around the lintels; others, such as the well-known Autobiography of Weni , were inscribed on large monolithic slabs and were quite detailed. The autobiography was written in prose; the Catalogue in formulaic poetry. A typical example of this is seen in the Inscription of Nefer-Seshem-Ra Called Sheshi from the 6th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom:

I have come from my town I have descended from my nome I have done justice for its lord I have satisfied him with what he loves. I spoke truly, I did right I spoke fairly, I repeated fairly I seized the right moment So as to stand well with people. I judged between two so as to content them I rescued the weak from the stronger than he As much as was in my power. I gave bread to the hungry, clothes to the naked I brought the boatless to land. I buried him who had no son, I made a boat for him who lacked one. I respected my father, I pleased my mother, I raised their children. So says he whose nickname is Sheshi. (Lichtheim, 17)

These autobiographies and virtue lists gave rise to the Pyramid Texts of the 5th and 6th dynasties which were reserved for royalty and told the story of a king's life, his virtues, and his journey to the afterlife; they therefore tried to encompass the earthly life of the deceased and his immortal journey on into the land of the gods and, in doing so, recorded early religious beliefs. Creation myths such as the famous story of Atum standing on the primordial mound amidst the swirling waters of chaos, weaving creation from nothing, comes from the Pyramid Texts . These inscriptions also include allusions to the story of Osiris , his murder by his brother Set, his resurrection from the dead by his sister-wife Isis , and her care for their son Horus in the marshes of the Delta.

Following closely on the heels of the Pyramid Texts , a body of literature known as the Instructions in Wisdom appeared. These works offer short maxims on how to live much along the lines of the biblical Book of Proverbs and, in many instances, anticipate the same kinds of advice one finds in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Psalms, and other biblical narratives. The oldest Instruction is that of Prince Hardjedef written sometime in the 5th Dynasty which includes advice such as:

Cleanse yourself before your own eyes Lest another cleanse you. When you prosper, found your household, Take a hearty wife, a son will be born to you. It is for the son you build a house When you make a place for yourself. (Lichtheim, 58)

The somewhat later Instruction Addressed to Kagemni advises:

The respectful man prospers, Praised is the modest one. The tent is open to the silent, The seat of the quiet is spacious Do not chatter!... When you sit with company, Shun the food you love; Restraint is a brief moment Gluttony is base and is reproved. A cup of water quenches the thirst, A mouthful of herbs strengthens the heart. (Lichtheim, 59-60)

There were a number of such texts, all written according to the model of Mesopotamian Naru Literature , in which the work is ascribed to, or prominently features, a famous figure. The actual Prince Hardjedef did not write his Instruction nor was Kagemni's addressed to the actual Kagemni. As in Naru literature, a well-known person was chosen to give the material more weight and so wider acceptance. Wisdom Literature, the Pyramid Texts , and the autobiographical inscriptions developed significantly during the Old Kingdom and became the foundation for the literature of the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom Literature

The Middle Kingdom is considered the classical age of Egyptian literature. During this time the script known as Middle Egyptian was created, considered the highest form of hieroglyphics and the one most often seen on monuments and other artifacts in museums in the present day. Egyptologist Rosalie David comments on this period:

The literature of this era reflected the added depth and maturity that the country now gained as a result of the civil wars and upheavals of the First Intermediate Period . New genres of literature were developed including the so-called Pessimistic Literature, which perhaps best exemplifies the self-analysis and doubts that the Egyptians now experienced. (209)

The Pessimistic Literature David mentions is some of the greatest work of the Middle Kingdom in that it not only expresses a depth of understanding of the complexities of life but does so in high prose. Some of the best known works of this genre (generally known as Didactic Literature because it teaches some lesson) are The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba (soul) , The Eloquent Peasant , The Satire of the Trades , The Instruction of King Amenemhet I for his Son Senusret I , the Prophecies of Neferti , and the Admonitions of Ipuwer .

The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba is considered the oldest text on suicide in the world. The piece presents a conversation between a narrator and his soul on the difficulties of life and how one is supposed to live in it. In passages reminiscent of Ecclesiastes or the biblical Book of Lamentations, the soul tries to console the man by reminding him of the good things in life, the goodness of the gods, and how he should enjoy life while he can because he will be dead soon enough. Egyptologist W.K. Simpson has translated the text as The Man Who Was Weary of Life and disagrees with the interpretation that it has to do with suicide. Simpson writes:

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

This Middle Kingdom text, preserved on Papyrus Berlin 3024, has often been interpreted as a debate between a man and his ba on the subject of suicide. I offer here the suggestion that the text is of a somewhat different nature. What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. (178)

The depth of the conversation between the man and his soul, the range of life experiences touched on, is also seen in the other works mentioned. In The Eloquent Peasant a poor man who can speak well is robbed by a wealthy landowner and presents his case to the mayor of the town. The mayor is so impressed with his speaking ability that he keeps refusing him justice so he can hear him speak further. Although in the end the peasant receives his due, the piece illustrates the injustice of having to humor and entertain those in positions of authority in order to receive what they should give freely.

The Satire of the Trades is presented as a man advising his son to become a scribe because life is hard and the best life possible is one where a man can sit around all day doing nothing but writing. All the other trades one could practice are presented as endless toil and suffering in a life which is too short and precious to waste on them.

The motif of the father advising his son on the best course in life is used in a number of other works. The Instruction of Amenemhat features the ghost of the assassinated king warning his son not to trust those close to him because people are not always what they seem to be; the best course is to keep one's own counsel and be wary of everyone else. Amenemhat's ghost tells the story of how he was murdered by those close to him because he made the mistake of believing the gods would reward him for a virtuous life by surrounding him with those he could trust. In Shakespeare's Hamlet Polonius advises his son, "Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried/ Grapple them unto thy soul with hoops of steel/ But do not dull thy palm with entertainment of each new-hatched, unfledged courage" (I.iii.62-65). Polonius here is telling his son not to waste time on those he barely knows but to trust only those who have proven worthy. Amenemhat I's ghost makes it clear that even this is a foolish course:

Put no trust in a brother, Acknowledge no one as a friend, Do not raise up for yourself intimate companions, For nothing is to be gained from them. When you lie down at night, let your own heart be watchful over you, For no man has any to defend him on the day of anguish. (Simpson, 168)

The actual king Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) was the first great king of the 12th Dynasty and was, in fact, assassinated by those close to him. The Instruction bearing his name was written later by an unknown scribe, probably at the request of Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE) to eulogize his father and vilify the conspirators. Amenemhat I is further praised in the work Prophecies of Neferti which foretell the coming of a king (Amenemhat I) who will be a savior to the people, solve all the country's problems, and inaugurate a golden age. The work was written after Amenemhat I's death but presented as though it were an actual prophecy pre-dating his reign.

This motif of the "false prophecy" - a vision recorded after the event it supposedly predicts - is another element found in Mesopotamian Naru literature where the historical "facts" are reinterpreted to suit the purposes of the writer. In the case of the Prophecies of Neferti, the focus of the piece is on how mighty a king Amenemhat I was and so the vision of his reign is placed further back in time to show how he was chosen by the gods to fulfil this destiny and save his country. The piece also follows a common motif of Middle Kingdom literature in contrasting the time of prosperity of Amenemhat I's reign, a "golden age", with a previous one of disunity and chaos.

The Admonitions of Ipuwer touches on this theme of a golden age more completely. Once considered historical reportage, the piece has come to be recognized as literature of the order vs. chaos didactic genre in which a present time of despair and uncertainty is contrasted with an earlier era when all was good and life was easy. The Admonitions of Ipuwer is often cited by those wishing to align biblical narratives with Egyptian history as proof of the Ten Plagues from the Book of Exodus but it is no such thing.

Not only does it not - in any way - correlate to the biblical plagues but it is quite obviously a type of literary piece which many, many cultures have produced throughout history up to the present day. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that everyone, at some point in his or her life, has looked back on the past and compared it favorably to the present. The Admonitions of Ipuwer simply records that experience, though perhaps more eloquently than most, and can in no way be interpreted as an actual historical account.

In addition to these prose pieces, the Middle Kingdom also produced the poetry known as The Lay of the Harper (also known as The Songs of the Harper ), which frequently question the existence of an ideal afterlife and the mercy of the gods and, at the same time, created hymns to those gods affirming such an afterlife. The most famous prose narratives in Egyptian history - The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and The Story of Sinuhe both come from the Middle Kingdom as well. The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor holds Egypt up as the best of all possible worlds through the narrative of a man shipwrecked on an island and offered all manner of wealth and happiness; he refuses, however, because he knows that all he wants is back in Egypt. Sinuhe's story reflects the same ideal as a man is driven into exile following the assassination of Amenemhat I and longs to return home.

The complexities Egypt had experienced during the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) were reflected in the literature which followed in the Middle Period. Contrary to the claim still appearing in history books on Egypt, the First Intermediate Period had not been a time of chaos, darkness, and universal distress; it was simply a time when there was no strong central government. This situation resulted in a democritization of art and culture as individual regions developed their own styles which were valued as greatly as royal art had been in the Old Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom scribes, however, looked back on the time of the First Intermediate Period and saw in it a clear departure from the glory of the Old Kingdom. Works such as The Admonitions of Ipuwer were interpreted by later Egyptologists as accurate accounts of the chaos and disorder of the era preceding the Middle Kingdom but actually, if it were not for the freedom of exploration and expression in the arts the First Intermediate Period encouraged, the later scribes could never have written the works they produced.

The royal autobiographies and Offering Lists of the Old Kingdom, only available to kings and nobles, were made use of in the First Intermediate Period by anyone who could afford to build a tomb, royal and non-royal alike. In this same way, the literature of the Middle Kingdom presented stories which could praise a king like Amenemhat I or present the thoughts and feelings of a common sailor or the nameless narrator in conflict with his soul. The literature of the Middle Kingdom opened wide the range of expression by enlarging upon the subjects one could write about and this would not have been possible without the First Intermediate Period.

Following the age of the 12th Dynasty, in which the majority of the great works were created, the weaker 13th Dynasty ruled Egypt. The Middle Kingdom declined during this dynasty in all aspects, finally to the point of allowing a foreign people to gain power in lower Egypt: The Hyksos and their period of control, just like the First Intermediate Period, would be vilified by later Egyptian scribes who would again write of a time of chaos and darkness. In reality, however, the Hyksos would provide valuable contributions to Egyptian culture even though these were ignored in the later literature of the New Kingdom .

Literature in the New Kingdom

Between the Middle Kingdom and the era known as the New Kingdom falls the time scholars refer to as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-c.1570 BCE). During this era rule in Egypt was divided between the foreign kings of the Hyksos in Lower Egypt at Avaris, Egyptian rule from Thebes in Upper Egypt, and control of the southern reaches of Upper Egypt by the Nubians. Egypt was united, and the Hyksos and Nubians driven beyond the borders, by Ahmose of Thebes (c. 1570-1544 BCE) who inaugurated the New Kingdom. The memory of the Hyksos "invasion" remained fresh in the minds of the Egyptians and was reflected in the political policies and the literature of the period.

The early pharaohs of the New Kingdom dedicated themselves to preventing any kind of incursion like that of the Hyksos and so embarked on a series of military campaigns to expand Egypt's borders; this resulted in the Age of Empire for Egypt which was reflected in a broader scope of content in the literature and art. Monumental inscriptions of the gods of Egypt and their enduring support for the pharaoh became a vehicle for expressing the country's superiority over its neighbors, stories and poems reflected a greater knowledge of the world beyond Egypt's borders, and the old theme of order vs. chaos was re-imagined as a divine struggle. These larger themes were emphasized over the pessimistic and complex views of the Middle Kingdom. The Hyksos and the Second Intermediate Period did the same for New Kingdom art and literature that the First Intermediate Period had for the Middle Kingdom; it made the works richer and more complex in plot, style, and characterization. Rosalie David writes:

New Kingdom literature, developed in a period when Egypt had founded an empire, displays a more cosmopolitan approach. This is expressed in texts that seek to promote the great state god , Amun -Ra, as a universal creator and in the inscriptions carved on temple walls and elsewhere that relate the king's military victories in Nubia and Syria . (210)

This is true only of the monumental inscriptions and hymns, however. The inscriptions are religious in nature and focus on the gods, usually either on Amun or Osiris and Isis, the gods of the two most popular religious cults of the time. Stories and poems, however, continued to deal for the most part with the conflicts people faced in their lives such as dealing with injustice, an unfaithful spouse, and trying to live one's life fully in the face of death. These same themes had been touched on or fully dealt with during the Middle Kingdom but the New Kingdom texts show an awareness of other cultures, other values, outside of the Egyptian paradigm.

Middle Kingdom literature was now considered "classical" and studied by students learning to be scribes. An interesting aspect of New Kingdom literature is its emphasis on the importance of the scribal tradition. Scribes had always been considered an important aspect of Egyptian daily life and the popularity of The Satire of the Trades makes clear how readers in the Middle Kingdom recognized this. In the New Kingdom, however, in the works extant in the Papyrus Lansing and the Papyrus Chester Beatty IV , a scribe is not simply a respected profession but one who is almost god-like in the ability to express concepts in words, to create something out of nothing, and so become immortal through their work. Lichtheim comments on the Papyrus Chester Beatty IV :

Papyrus Chester Beatty IV is a typical scribal miscellany. The recto contains religious hymns; the verso consists of several short pieces relating to the scribal profession. Among these, one piece is of uncommon interest. It is a praise of the writer's profession which goes beyond the usual cliches and propounds the remarkable idea that the only immortality man can achieve is the fame of his name transmitted by his books. Man becomes dust; only the written word endures. (New Kingdom, 167)

The concept of the sacred nature of words had a long history in Egypt. The written word was thought to have been given to humanity by the god of wisdom and knowledge, Thoth . Worship of Thoth can be dated to the late Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE) when Egyptians first began to discover writing. During the 2nd Dynasty of the Early Dynastic Period, Thoth received a consort: his sometimes-wife/sometimes-daughter Seshat . Seshat was the goddess of all the different forms of writing, patroness of libraries and librarians, who was aware of what was written on earth and kept a copy of the scribe's work in the celestial library of the gods.

Seshat ("the female scribe"), as part of her responsibilities, also presided over accounting, record-keeping, census-taking, and measurements in the creation of sacred buildings and monuments. She was regularly invoked as part of the ceremony known as "the stretching of the cord" in which the king would measure out the ground on which a temple was built. In this capacity she was known as Mistress of Builders who measured the land and lay the foundation of temples. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson writes, "she appears to have had no temple of her own, but by virtue of her role in the foundation ceremony, she was part of every temple building" (167). Her involvement in a temple complex did not end with its inception, however, as she continued to inhabit a part of the temple known as the House of Life. Rosalie David explains the function of this part of the temple:

The House of Life appears to have been an area of the temple that acted as a library, scriptorium, and higher teaching institution, where the sacred writings were produced and stored and where instruction was given. Medical and magical texts as well as religious books were probably compiled and copied there. Sometimes this institution may have been situated within the temple itself, but elsewhere it was probably located in one of the buildings within the temple precinct. Very little is known of its administration or organization but it is possible that every sizable town had one. They are known to have existed at Tell el- Amarna , Edfu, and Abydos. (203)

The name of the institution reflects the value Egyptians placed on the written word. The House of Life - a school, library, publishing house, distributor, and writer's workshop combined - was presided over by Seshat who made sure to keep copies of all that was produced there in her own celestial library.

During the New Kingdom these works were largely hymns, prayers, instructions in wisdom, praise songs, love poems, and stories. The Egyptian love poem of the New Kingdom is remarkably similar on many levels to the biblical Song of Solomon and the much later compositions of the troubadors of 12th century CE France in their evocation of a beloved who is beyond compare and worthy of all devotion and sacrifice. The same sentiments, and often imagery, used in these New Kingdom love poems are still recognizable in the lyrics of popular music in the present day.

The narrative structure of the prose work of the time, and sometimes even plot elements, will also be recognized in later works. In the story of Truth and Falsehood (also known as The Blinding of Truth by Falsehood ), a good and noble prince (Truth) is blinded by his evil brother (Falsehood) who then casts him out of the estate and assumes his role. Truth is befriended by a woman who falls in love with him and they have a son who, when he discovers the noble identity of his father, avenges him and takes back his birthright from the usurper.

This plot line has been used, with modifications, in many stories since. The basic plot of any adventure tale is utilized in the story known as The Report of Wenamun which is a story about an official sent on a simple mission to procure wood for a building project. In the course of what was supposed to be a short and easy trip, Wenamun encounters numerous obstacles he needs to overcome to reach his goal and return home.

Two of the best known tales are The Prince Who Was Threatened by Three Fates (also known as The Doomed Prince ) and The Two Brothers (also known as The Fate of an Unfaithful Wife ). The Doomed Prince has all the elements of later European fairy tales and shares an interesting similarity with the story of the awakening of the Buddha : a son is born to a noble couple and the Seven Hathors (who decree one's fate at birth) arrive to tell the king and queen their son will die by a crocodile, a snake, or a dog. His father, wishing to keep him safe, builds a stone house in the desert and keeps him there away from the world. The prince grows up in the isolation of this perfectly safe environment until, one day, he climbs to the roof of his home and sees the world outside of his artificial environment.

He tells his father he must leave to meet his fate, whatever it may be. On his journeys he finds a princess in a high castle with many suitors surrounding the tower trying to accomplish the feat of jumping high enough to catch the window's edge and kiss her. The prince accomplishes this, beating out the others, and then has to endure a trial to win the father's consent. He marries the princess and later meets all three of his fates - the crocodile, snake, and dog - and defeats them all. The end of the manuscript is missing but it is assumed, based on the narrative structure, that the conclusion would be the couple living happily ever after.

The Two Brothers tells the story of the divine siblings Anubis and Bata who lived together with Anubis' wife. The wife falls in love with the younger brother, Bata, and tries to seduce him one day when he returns to the house from the fields. Bata refuses her, promising he will never speak of the incident to his brother, and leaves. When Anubis returns home he finds his wife distraught and she, fearing that Bata will not keep his word, tells her husband that Bata tried to seduce her. Anubis plans to kill Bata but the younger brother is warned by the gods and escapes. Anubis learns the truth about his unfaithful wife - who goes on to cause more problems for them both - and must do penance before the brothers are united and the wife is punished.

From this same period comes the text known as The Contendings of Horus and Set , although the actual story is no doubt older. This tale is a divine version of the Middle Kingdom order vs. chaos motif in which Horus (champion of order) defeats his uncle Set (symbolizing chaos) to avenge his father Osiris and restore the kingdom which Set has usurped. Horus, the prince, must avenge the murder of his father by his uncle and, to do this, must endure a number of trials to prove himself worthy of the throne. This is the basic paradigm of what scholar Joseph Campbell calls "the hero's journey" and can be seen in myths around the world and throughout history. The enduring popularity of George Lucas' Star Wars films is their adherence to the narrative form and symbolism of this type of tale.

The Contendings of Horus and Set , although likely never read by later authors, is a precursor to two of the best-loved and most popular plots in western literature: Hamlet and Cinderella . American author Kurt Vonnegut has pointed out that both of these stories have been re-imagined with great success multiple times. The story of the disenfranchised who wins back what is rightfully theirs, sometimes at great cost, continues to resonate with audiences in the present day just as The Contendings of Horus and Set did for an ancient Egyptian audience.

Probably the best-known piece of literature from New Kingdom texts, however, is The Book of Coming Forth by Day , commonly known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead . Although the concepts and spells in The Egyptian Book of the Dead originated in the Early Dynastic Period and the book took form in the Middle Kingdom, it became extremely popular in the New Kingdom and the best preserved texts we have of the work date to that time.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead is a series of "spells" which are instructions for the deceased in the afterlife to help them navigate their way through various hazards and find everlasting peace in paradise. The work is not an "ancient Egyptian Bible ", as some have claimed, nor is it a "magical text of spells". As the afterlife was obviously an unknown realm, The Egyptian Book of the Dead was created to provide the soul of the deceased with a kind of map to help guide and protect them in the land of the dead.