Interview Essay

Interview essay generator.

Essay writing is different for everyone. Some people choose to go to the library and search for facts on a given subject, while others like to focus on gathering information through personal statements .

During this interview process, interviewers typically ask a series of interview questionnaire that their readers may want to know about. These details are either recorded or jotted down by the interviewee. With what has been gathered, an individual may then write a complete essay regarding the exchange.

Interview Essay Sample

- Google Docs

Size: 168 KB

Personal Interview Essay Template

Size: 136 KB

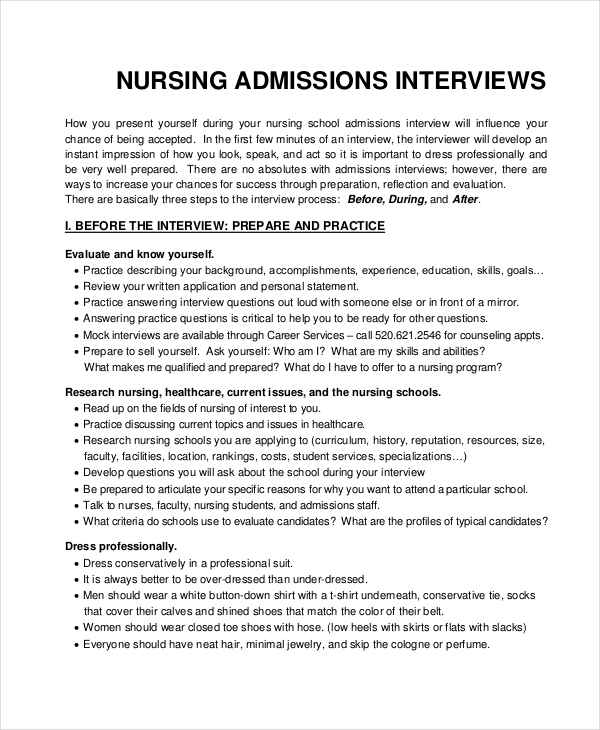

Nursing Interview Essay Template

Size: 123 KB

Leadership Interview Essay Template

Size: 154 KB

Teacher Interview Essay Template

Size: 150 KB

Job Interview Essay Sample

Narrative Interview

Size: 70 KB

Career Interview Essay

Size: 29 KB

What Is an Interview Essay?

Interview essays are typically based on research gathered from personal testimonies. This could be based on one’s personal experiences or their own input on a given matter. It may be informative essay , descriptive essay , or even persuasive essays , depending on the questions asked by the interviewer.

The content of the essay may include direct quotes from the interview or it may come in a written narrative form. Through this, we are able to gain additional information from a particular perspective.

What to Include in an Interview Essay

For every essay, a thesis statement is needed to help your readers understand the subject being tackled in your work. For an interview short essay , you would need to talk about your interviewee. Any information that will create a credible image for your interviewee will be necessary.

Next, it’s necessary to include the significant ideas that you have acquired from your interview. Ideally, you should pick three of these ideas, elaborate what has been said, and present it in paragraphs. Be sure to emphasize these points in a detailed and concise manner, a lengthy explanation might be too redundant. You may also see sample essay outlines .

Leadership Essay

Size: 24 KB

Nursing Interview Example

Size: 146 KB

Personal Interview

Size: 18 KB

Parent Interview Sample

Size: 15 KB

Guidelines for an Interview Essay

When writing an interview essay, it would be best to create an outline first.

Organize the information you have gathered from your interviewee and structure it in a logical order. This could be from one’s personal information to the most compelling details gathered. Be reminded of the standard parts of an essay and be sure to apply it to your own work.

Even when most, if not all, of your essay’s content is based on what you have gathered from your interviewee, you would still need to create a good starting of essay and end to your essay.

Additionally, do not forget to put quotation marks around the exact words used by your interviewee. It would also be best to proofread your work and make sure that there is a smooth transition for each thought. You may also like personal essay examples & samples.

How to Conclude an Interview Essay?

You can end your interview essay how ever you wish to do so. It could be about your learning from the interview, a call to action, or a brief summary writing from what has been expressed in the essay.

But keep in mind, this would depend on your purpose for writing the essay. For instance, if you interviewed a biologist to spread awareness about mother nature, then it would be best to conclude your essay with a call to action. Knowing this, it’s important to end your essay well enough for it to be memorable.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write an Interview Essay on a local community leader.

Discuss the career journey of a teacher in your Interview Essay.

How To Write an Interview Essay

The aim of an interview is that through using people rather than books or articles, the writer can obtain a first-person viewpoint on a subject. The interview can be related to experiences in their life or may be related to a field in which they are an expert. Clearly these types of essays require a different form of planning and research. Typically, this includes the following steps:

- Determine the subject on which the person is to be interviewed.

- Identify the target interviewees, contact them, and ask for consent.

- Personal details (name, occupation, or credentials where appropriate, age if relevant, location if relevant)

- Primary question: The main focus of the work and some short main topic questions

- Notes on exploring the respondent’s answers – i.e., reminder questions for the writer such as “why do you feel that way?”, “Can you explain that in more detail?”, “Why do you think some people disagree with you?”

- Analyse the information / answers given by your interviewee.

Once you have followed these stages, you can draft / outline your interview essay in a more standard format:

- Break up the responses into key themes or points that you will make.

- Identify any other sources that you will use in your essay.

- Give an approximate word count to each section.

Note that using closed questions requiring “yes/no” answers are effective for gathering factual information, however, more detailed responses can be achieved with open-ended questions starting, “how”, “why”, “talk to me about…” and similar. Using these questions also encourages you to ask more for more detail that will expand your essay and source information.

Analysing your interviews

When analysing your interview(s), the approach will depend on the focus of your interview. For example, if you have undertaken 2/3 interviews for considering an experience, you may wish to follow the narrative route. However, if you have undertaken only one interview on a specific topic in which your interviewee is an expert, you may look at content analysis. In both cases, however you should, as you look through the interview notes or transcriptions if you have these and ask yourself:

- What reasons/ points/ perspectives did the interviewees give in support or opposition to the main topic

- Are they positive or negative?

- How does their responses compare to existing views?

- How interesting or important are the responses given?

- What is your own perspective of the views/reasons/responses given?

Once you have written down your initial analysis in order to structure your interview essay in a logical format you should then list the points/reasons given in the following way:

- least to most important

- positive first, then negative

- negative, then positive

- those you disagree with, those you agree with

- those which are pretty typical, those which are unusual.

Writing your Interview Essay

Introduction.

Your introduction should commence with an indication of the key question asked. This can either be in the form of a comment from the interviewee or a description of the situation that led to the development of your main question.

In addition, you should clearly state the type of interview undertaken (survey, narrative etc.) so that the reader has a context for your work. The introduction should then provide an overview of the responses given, along with your own perspectives and thoughts on these (your thesis statement) before introducing the body of the essay through linking. For example, “having stated X, the work will now provide a more detailed overview of some of the key comments and their implications in relation to XX”.

The body text should follow the order of your points indicated above. Use only one paragraph per point structured by indicating the point made, why you agree/disagree and any other relevant subpoints made by the interviewee in regard to the first points.

The paragraph should conclude with a link to the next theme which leads to the next paragraph and demonstrates cohesion of thought and logical flow of reporting the interview analysis. Note: you can include quotations from the interview, but do not rely on these, they should only be used to reinforce a point of view, and where possible avoid the inclusion of slang or swearing unless it is vital to the point you are making.

Your conclusion should bring together all the perspectives given by the interviewee. It is, in effect, a synopsis of the work with your own conclusions included. It is useful to refer back to the main question and your thesis statement to indicate how the interviewee answered (or not) your question and what this means for your future views or action in regard to the topic. A strong conclusion is as vital as a strong introduction and should not introduce any new information but should be a precis of the overall essay.

Key Phrases for an Interview Essay

The main subject under discussion was…”

“The interviewee was very clear when discussing…”

“The interviewee was somewhat vague when asked about…”

“This raised the question of…”

“When asked about x, the interviewee stated/asserted/claimed/maintained/declared, believed/thought/.”

“From the perspectives given by the interviewee it seems that…”

How to Write an Interview Essay: Complete Guide

College and high school teachers often assign interview papers to test their learners’ planning, paraphrasing, and critical thinking skills. So, besides drafting a well-substantiated and information-packed piece, students must also organize and conduct an interviewing process.

Hence, this assignment is far from straightforward. Quite the contrary, it requires substantial pre-work before the actual meeting. Moreover, the task further complicates if you include several subjects or elaborate on a compelling theme.

What if you can’t meet an ideal candidate to elaborate on your topic? How to pose questions that reveal valuable information and present your findings on paper? How to write an interview essay introduction with attention-grabbing ideas that bring up current dilemmas or resolve an issue? There are so many trilemmas spinning around your head.

Fortunately, there’s no need to feel intimated or discouraged. This article will help you grasp the basics of an interview paper and how to write an outstanding piece. It will also discuss the steps involved in the writing process and give a few helpful tips that ensure your final product passes with flying colors.

What Is an Interview Essay?

An interview paper is an academic written piece that presents the insight the interviewer gained while interviewing one or several people. It aims to expose different perspectives on a particular topic once the writer gathers relevant data through research. Typically, the essence of the paper will rest upon your findings from the interviews.

The presented viewpoints will depend on the respondent. So, for example, if your paper interview focuses on social media, you might consider talking to an influencer. Conversely, if you’re elaborating on a burning social issue, you may want to speak to a local authority. Or set up a meeting with a scientist if you’re exploring natural sciences.

The interview paper must help the reader understand a concept backed by relevant statements. Unlike definition essay writing , where you paraphrase and cite trusted sources like scholarly books, the interview paper will stem from authoritative individuals in the respective field.

Finally, you can reap a lot of benefits from drafting interview essays. More specifically, those interested in becoming broadcast journalists, newspaper reporters, or editors will learn to pose thought-provoking questions. Similarly, HR managers will polish their screening ability and hire excellent candidates. Even prospective detectives and inspectors can gain from writing an interview essay. They will formulate a variety of engaging questions to get honest and accurate answers.

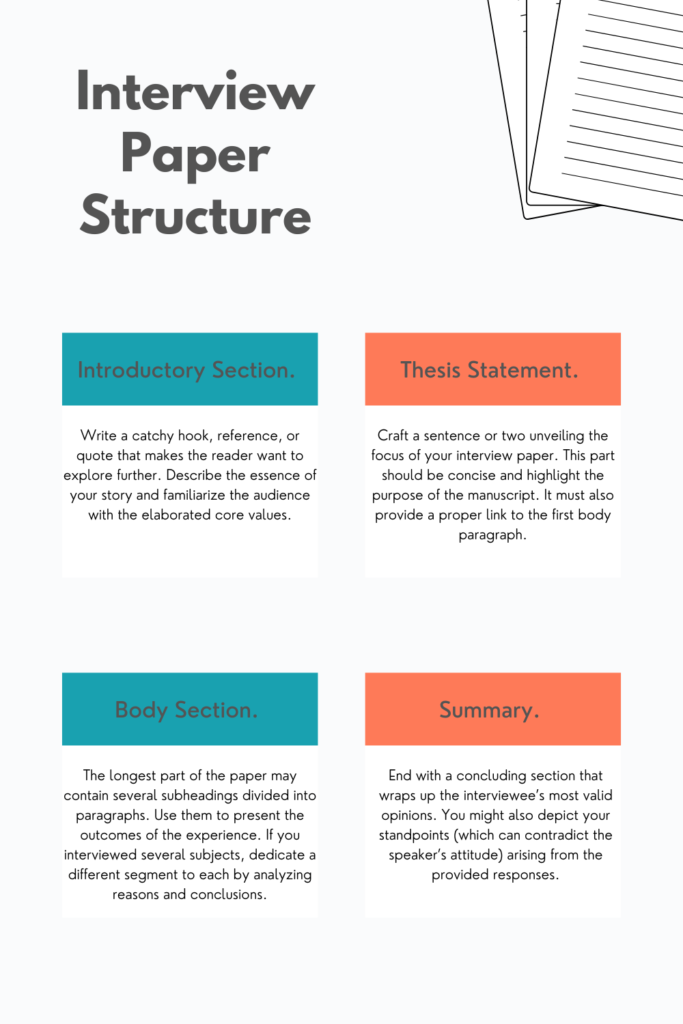

Outline and Typical Structure of an Interview Paper

Most essays follow the template of a basic 5-paragraph paper. Yet, the length can vary according to your subject and data availability. A standard interview essay from a custom writing service can range from 2,000 to 5,000 words or up to ten pages. Individual works are usually shorter.

The interview essay format will have an introduction, body segments (perspectives grouped under different subheadings), and a summary. Here’s an overview of what to put in each part.

Introduction . The writer needs to create an atmosphere of uncertainty and urgency to stimulate the audience to keep reading. It should also provide background information about the theme and the interviewee. Furthermore, the initial part can list statistics or what society thinks about the respective topic. Finally, your intro must contain a thesis that transitions into the main section.

Body . This part will present the pillars on which you conceptualized your research. If you get stuck while drafting the body, you might hire an online service to write an essay for you and incorporate the gathered data. They will isolate the main points and help you frame the perfect timeline of events.

Moreover, the body should reflect important facts, life periods, and considerations of your interviewees. For instance, you might split your paper into infancy, adolescence, university, marriage, and golden years. Or you might divide your segments according to different discussion questions.

Conclusion . Use the ending part to summarize the interviewee’s thoughts and your insights into the matter. You might also compare the available data to the facts collected during the meeting and verify their validity. The bottom line must leave a lasting impression on your audience.

Steps for Writing a Successful Interview

Below is a detailed description of the paper composition journey. Consider each step carefully and be consistent in your approach.

Define the Paper’s Objective

Writing an interview paper urges you to establish the overall purpose. You will have to specify the message you plan to deliver. For example, if you want to verify a public opinion, you’ll have to question several subjects. Alternatively, proving a natural phenomenon will require a conversation with an expert in the field.

Explore the Subject

Find and prepare printed and virtual materials related to your research. Previous interviews and works by the interviewee are also vital. Unlike rebuttal essays , your primary goal is to gather details supporting your claims. Therefore, brainstorm any note you found based on your predefined criteria.

Pick an Interview Format

Your sample form will depend on the specific theme. Most students decide to buy a literature essay online due to their lack of formatting skills. Here are the various formats you can choose when presenting your findings.

This format implies using direct or indirect speech to analyze the storyline. Consider retelling the considerations of the interviewee and citing the original wording. The narrative format is also advisable if you talk to a few interviewees. The structure should contain an intro, a body (each paragraph can describe a particular idea of a single person), and a summary.

Question-and-answer essays are ideal when interviewing one person. Most magazines and news reports prefer this type because it is the simplest. Your interview paper will have an intro, different parts for each question and answer, an analysis with your perspective, and a summary.

Informative

Also known as conversational or personal, these papers are informal and take first or second-person narration flow. However, writing in a dialogue form might be confusing and perplexing for an untrained eye.

Formulate the Questions

Make a thorough list of all the aspects you want to discuss and cover in the interview paper. Ask close-ended (yes/no) and open-ended questions that require in-depth responses. If you struggle with your questionnaire, consider the following suggestions:

- Share your core values

- What would you change in the world if you had a superpower for a day?

- How did your childhood impact your personality?

- What is the recipe for success?

- What is the best aspect of your job?

- How do you overcome your deepest fears?

- Define happiness with examples

- What object do you hold most dear and why?

- What is the most significant challenge in our society?

- How do you imagine the world’s future?

Get in Touch with the Respondent

Make an effort to contact your interviewee/s and be professional when arranging the meeting. You might need to use several communication channels to reach your target person. Focus on scheduling a time that works for everyone involved in the project.

Facilitate the Interview

Choose a peaceful and quiet place without any distractions. Always arrive on time for the meeting. Alternatively, consider setting it up in an online format, if finding a physical location isn’t viable. Most importantly, allow the speakers enough time to share their thoughts and maintain an impartial attitude to avoid miscommunication.

Interview Essay Writing Tips

Here’s some additional advice for writers taking the first steps toward interview writing.

Stick to Your Teacher’s Instructions

Your professor will probably mention the paper structure. For instance, if you receive a classification essay writing guidelines , don’t experiment with other formats. Moreover, rehearse the face-to-face meeting with a family member to avoid possible deadens. Here, you might come up with a follow-up question that clarifies some vague points.

Quote and Paraphrase Your Sources

Organize all the details on the background, education, and achievements before interviewing itself. When referring to the topics discussed, cite them properly and give credit. Also, explain the protocol to the respondent and the purpose of the research.

Consider Recording the Interview

The longer the meeting, the more details you’ll forget once you finish it. Avoid over-relying on your memory, and bring a recorder. Taking notes is also essential. However, don’t record unless the respondent gives prior approval.

Mind These Formatting Rules

Use a font size of 12 in Times New Roman with double spacing. Don’t forget to write a title page, too. When including citations longer than 40 words, use block quotes.

Edit and Proofread

Don’t expect the first draft to be the best. Reduce grammar mistakes and typos by polishing your initial wording. The final version must be logical, easy to read, and plagiarism-free.

Bottom Line

As intimidating as the interview paper might seem at the onset, these guidelines will help you stay focused and organized. Above all, pick an important topic with questions that affect ordinary people. This way, you can set up and develop the interviews more quickly. Undoubtedly, an A+ grade takes dedication and perseverance to research and write your paper.

Related posts:

- How To Write A Good Compare And Contrast Essay: Topics, Examples And Step-by-step Guide

How to Write a Scholarship Essay

- How to Write the Methods Section for a Research Paper: Effective Writing Guide

- Explaining Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy with Demonstrative Examples

Improve your writing with our guides

Definition Essay: The Complete Guide with Essay Topics and Examples

Critical Essay: The Complete Guide. Essay Topics, Examples and Outlines

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Types of Interviews – A Simple Guide & Examples

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

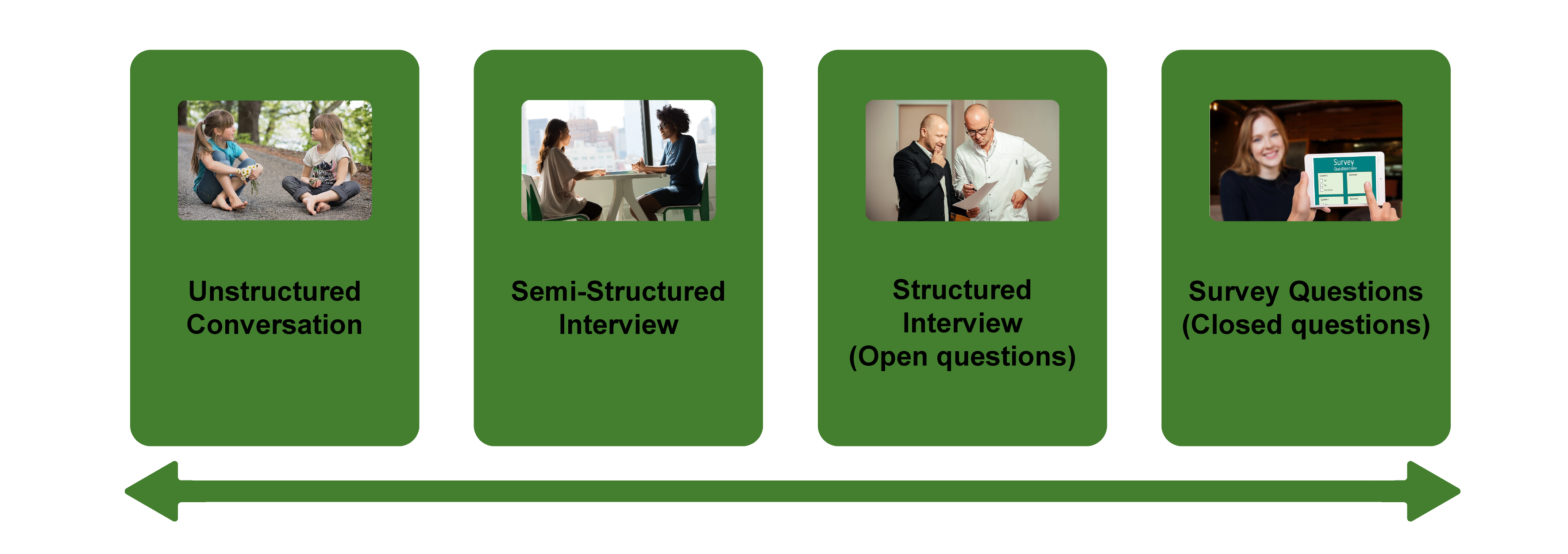

The methodology of employing different types of interviews plays a pivotal role in research, allowing for deep, qualitative insight into subjects’ experiences and perspectives. From structured to semi-structured and unstructured interviews, each type provides unique and invaluable information to meet diverse research objectives. In this guide, we will learn about the different types of interviews and where they are best applied.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Types of Interviews – In a Nutshell

- 2 Definition: Types of interviews

- 3 Types of interviews – Structured interview

- 4 Types of interviews – Semi-structured interview

- 5 Types of interviews – Unstructured interview

- 6 Types of interviews – Focus group

- 7 Types of interviews – Examples of interview questions

- 8 Pros and Cons of different types of interviews

Types of Interviews – In a Nutshell

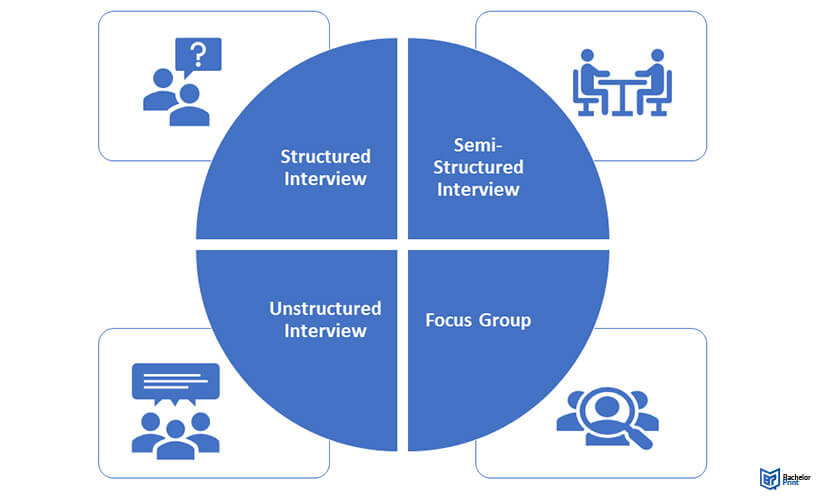

- The types of interviews you can use in research are structured interviews, unstructured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and focus group interviews.

- The interviewer effect is a bias that arises when the characteristics of the researcher influence the responses of the interviewees.

- A focus group is a research method that involves asking interview questions to a small group of people.

Definition: Types of interviews

There are three types of interviews, and these differ in the structure of the questions. The types of interviews are structured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and unstructured interviews. Structured interviews involve the use of set questions, and these must be asked in a given order. On the other hand, unstructured interviews are flexible and feature open-ended questions. Semi-structured interviews have elements of both structured and unstructured interviews.

Types of interviews – Structured interview

A structured interview is one where the questions are predetermined and set in a particular order. Typically, the questions will be closed-ended and will offer multiple choices. Since the questions are asked in a set order, it is easy for the researcher to compare responses and determine the patterns. Structured interviews help to mitigate biases and offer higher levels of validity and reliability. You can use this type of interview in the following cases:

- You understand the subject thoroughly and can design excellent questions

- You don’t have sufficient time and resources to carry out the research

- Your research question depends on a strong parity between the respondents

Types of interviews – Semi-structured interview

Semi-structured interviews have elements of both structured and unstructured interviews. With these interviews, the researcher will have an idea of the questions to ask, but the phrasing and order of the questions will not be set. Since they are often open-ended, the researcher will enjoy high levels of flexibility, and they will still be able to compare the responses fairly easily. These types of interviews are ideal in these situations:

- The researcher has a lot of experience in interviews

- The research question is exploratory in nature

Types of interviews – Unstructured interview

Unstructured interviews are also known as non-directive interviewing, and they don’t have a set pattern. Also, questions are not arranged in advance. These interviews are used as exploratory research tools and are commonly used in social sciences and humanities. Here are some occasions when an unstructured interview will be a great fit:

- If the research question is exploratory in nature

- If the research requires you to form a connection with your respondents

Types of interviews – Focus group

With focus group interviews, the researcher will present the questions to a group instead of an individual. These types of interviews don’t just study the responses of the interviewees; they also study the group dynamic and body language. The main issue with focus group interviews is that they have low external validity, and the interviewer may be biased when choosing the responses to include. Here are a few cases where focus group interviews can be suitable:

- If the study depends on group discussion dynamics

- If the questions are complex and can’t be answered with multiple choices

- If the study is open to uncovering new ideas and questions

Types of interviews – Examples of interview questions

The types of interview questions will vary depending on the type of interview. With structured interviews, the questions are set and precise, but the other types of interviews allow for flexible and open-ended questions.

| | • Do you own a car? Yes/No • Which is your favorite beverage? Coffee, tea, or chocolate |

| • How do you feel about pets? • Why do you think you have those feelings regarding pets? | |

| • Do you like sports cars? Yes/No • If yes, what do you like about these vehicles? • If no, what do you have about these vehicles? | |

| • If you could change one thing about our products, what would it be? |

Pros and Cons of different types of interviews

Interviews can help you collect useful information, but the types of interviews come with different pros and cons.

| | • Less susceptible to interviewer bias • Offer very high levels of credibility and validity • Simple to use Won’t cost a lot of money or time | • Can make the interviewees uncomfortable • Are not flexible • Have limited scope since they are closed-ended |

| • Highly flexible • Respondents are more open as it is structured like a daily conversation • Have a lower risk of bias • Offer more details and nuance | • Can be hard to generalize the results of these interviews • Can be hard for the interviewer to keep their opinions or feelings in check • Consumes a lot of time • Pose a risk of low internal validity • The interviewer may be tempted to ask leading questions, and this increases bias | |

| • Limits distraction during the interview • Combines the benefits of structured and unstructured interviews • Offers high levels of detail | • The flexibility of these interviews can reduce the validity of the study • They have a high risk of bias • It is hard to come up with good questions for these types of interviews | |

| • Is highly efficient • Interviewees will be more open • Can be done on a low budget • Makes it easy to discuss a variety of topics | • Interviewer won’t be able to ask too many questions • Requires excellent leadership and social skills • It has a risk of social desirability bias • Interviewer cannot guarantee confidentiality |

What is an interviewer effect?

This is a type of bias that emerges when the characteristics of an interviewer affect the responses given by the respondents.

When should you use unstructured interviews?

Unstructured interviews are great for building a bond with the respondent, and they can be used in cases where the interviewer needs the interviewee to be 100% honest.

When should you use structured interviews?

Structured interviews will be a good option for your research if you have limited time and resources. This is because they are easy to analyze.

What are the three types of interviews in research?

The three types of interviews in research are structured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and unstructured interviews.

Extremely satisfied, excellent deal with delivery in less than 24h. The print...

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

| Name | |

|---|---|

| Anbieter | Eigentümer dieser Website, |

| Zweck | Speichert die Einstellungen der Besucher, die in der Cookie Box von Borlabs Cookie ausgewählt wurden. |

| Cookie Name | borlabs-cookie |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 1 Jahr |

| Name | |

|---|---|

| Anbieter | Bachelorprint |

| Zweck | Erkennt das Herkunftsland und leitet zur entsprechenden Sprachversion um. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | ip-api.com |

| Cookie Name | georedirect |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 1 Jahr |

| Name | |

|---|---|

| Anbieter | Playcanvas |

| Zweck | Display our 3D product animations |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | playcanv.as, playcanvas.as, playcanvas.com |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 1 Jahr |

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland |

| Zweck | Cookie von Google zur Steuerung der erweiterten Script- und Ereignisbehandlung. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Cookie Name | _ga,_gat,_gid |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 2 Jahre |

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Meta Platforms Ireland Limited, 4 Grand Canal Square, Dublin 2, Ireland |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um Facebook-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | .facebook.com |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland |

| Zweck | Wird zum Entsperren von Google Maps-Inhalten verwendet. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | .google.com |

| Cookie Name | NID |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 6 Monate |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Meta Platforms Ireland Limited, 4 Grand Canal Square, Dublin 2, Ireland |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um Instagram-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | .instagram.com |

| Cookie Name | pigeon_state |

| Cookie Laufzeit | Sitzung |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Openstreetmap Foundation, St John’s Innovation Centre, Cowley Road, Cambridge CB4 0WS, United Kingdom |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um OpenStreetMap-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | .openstreetmap.org |

| Cookie Name | _osm_location, _osm_session, _osm_totp_token, _osm_welcome, _pk_id., _pk_ref., _pk_ses., qos_token |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 1-10 Jahre |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Twitter International Company, One Cumberland Place, Fenian Street, Dublin 2, D02 AX07, Ireland |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um Twitter-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | .twimg.com, .twitter.com |

| Cookie Name | __widgetsettings, local_storage_support_test |

| Cookie Laufzeit | Unbegrenzt |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Vimeo Inc., 555 West 18th Street, New York, New York 10011, USA |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um Vimeo-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | player.vimeo.com |

| Cookie Name | vuid |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 2 Jahre |

| Akzeptieren | |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Anbieter | Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland |

| Zweck | Wird verwendet, um YouTube-Inhalte zu entsperren. |

| Datenschutzerklärung | |

| Host(s) | google.com |

| Cookie Name | NID |

| Cookie Laufzeit | 6 Monate |

Privacy Policy Imprint

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 10 October 2022.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure. Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order. Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing, and semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research.

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyse because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered ‘the best of both worlds’.

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalisability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualise your initial hypotheses

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behaviour, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organise than experiments or large surveys. However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to ‘cherry-pick’ responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilise this research method.

| Type of interview | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Structured interview | ||

| Semi-structured interview | ||

| Unstructured interview | ||

| Focus group |

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. They are often quantitative in nature. Structured interviews are best used when:

- You already have a very clear understanding of your topic. Perhaps significant research has already been conducted, or you have done some prior research yourself, but you already possess a baseline for designing strong structured questions.

- You are constrained in terms of time or resources and need to analyse your data quickly and efficiently

- Your research question depends on strong parity between participants, with environmental conditions held constant

More flexible interview options include semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview, but it is not always the best fit for your research topic.

Unstructured interviews are best used when:

- You are an experienced interviewer and have a very strong background in your research topic, since it is challenging to ask spontaneous, colloquial questions

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. While you may have developed hypotheses, you are open to discovering new or shifting viewpoints through the interview process.

- You are seeking descriptive data, and are ready to ask questions that will deepen and contextualise your initial thoughts and hypotheses

- Your research depends on forming connections with your participants and making them feel comfortable revealing deeper emotions, lived experiences, or thoughts

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, October 10). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 12 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/types-of-interviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, face validity | guide with definition & examples, construct validity | definition, types, & examples.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Types of Interviews in Research and Methods

There are more types of interviews than most people think. An interview is generally a qualitative research technique that involves asking open-ended questions to converse with respondents and collect elicit data about a subject.

The interviewer, in most cases, is the subject matter expert who intends to understand respondent opinions in a well-planned and executed series of star questions and answers .

Interviews are similar to focus groups and surveys for garnering information from the target market but are entirely different in their operation – focus groups are restricted to a small group of 6-10 individuals, whereas surveys are quantitative.

Interviews are conducted with a sample from a population, and the key characteristic they exhibit is their conversational tone.

LEARN ABOUT: telephone survey

What is An Interview?

An interview is a way to get information from a person by asking questions and hearing their answers.

An interview is a question-and-answer session where one person asks questions, and the other person answers those questions. It can be a one-on-one, two-way conversation, or there can be more than one interviewer and more than one participant.

The interview is the most important part of the whole selection bias process. It is used to decide if a person should be interviewed further, hired, or taken out of consideration. It is the main way to learn more about applicants and the basis for judging their job-related knowledge, research skills , and abilities.

Fundamental Types of Interviews in Research

A researcher has to conduct interviews with a group of participants at a juncture in the research where information can only be obtained by meeting and personally connecting with a section of their target audience. Interviews offer the researchers a platform to prompt their participants and obtain inputs in the desired detail. There are three fundamental types of interviews in research:

1. Structured Interviews:

Structured interviews are defined as research tools that could be more flexible in their operations are allow more or no scope of prompting the participants to obtain and analyze results. It is thus also known as a standardized interview and is significantly quantitative in its approach.

Questions in this interview are pre-decided according to the required detail of information. This can be used in a focus group interview and an in-person interview.

These interviews are excessively used in survey research with the intention of maintaining uniformity throughout all the interview sessions.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

They can be closed-ended and open-ended – according to the type of target population. Closed-ended questions can be included to understand user preferences from a collection of answer options. In contrast, open-ended ones can be included to gain details about a particular section in the interview.

Example of a structured interview question:

Here’s an example of a structured question for a job interview for a customer service job:

- Can you talk about what it was like to work in customer service?

- How do you deal with an angry or upset customer?

- How do you ensure that the information you give customers is correct?

- Tell us about when you went out of your way to help a customer.

- How do you handle a lot of customers or tasks at once?

- Can you talk about how you’ve used software or tools for customer service?

- How do you set priorities and use your time well while giving good customer service?

- Can you tell us about when you had to get a customer to calm down?

- How do you deal with a customer who wants something that goes against your company’s rules?

- Tell me about a time when you had to deal with a hard customer or coworker.

Advantages of structured interviews:

- It focuses on the accuracy of different responses, due to which extremely organized data can be collected. Different respondents have different types of answers to the same structure of questions – answers obtained can be collectively analyzed.

- They can be used to get in touch with a large sample of the target population.

- The interview procedure is made easy due to the standardization offered by it.

- Replication across multiple samples becomes easy due to the same structure of the interview.

- As the scope of detail is already considered while designing the interview questions, better information can be obtained. The researcher can analyze the research problem comprehensively by asking accurate research questions .

- Since the structure of the interview is fixed, it often generates reliable results and is quick to execute.

- The relationship between the researcher and the respondent is not formal, due to which the researcher can clearly understand the margin of error in case the respondent either degree to be a part of the survey or is just not interested in providing the right information.

Disadvantages of structured interviews:

- The limited scope of assessment of obtained results.

- The accuracy of information overpowers the detail of information.

- Respondents are forced to select from the provided answer options.

- The researcher is expected to always adhere to the list of decided questions, irrespective of how interesting the conversation is turning out to be with the participants.

- A significant amount of time is required for a structured interview.

Learn more: Market Research

2. Semi-Structured Types of Interviews:

Semi-structured interviews offer a considerable amount of leeway to the researcher to probe the respondents, along with maintaining a basic interview structure. Even if it is a guided conversation between researchers and interviewees – appreciable flexibility is offered to the researchers. A researcher can be assured that multiple interview rounds will not be required in the presence of structure in this type of research interview.

Keeping the structure in mind, the researcher can follow any idea or take creative advantage of the entire interview. Additional respondent probing is always necessary to garner information for a research study. The best application of semi-structured interviews is when the researcher doesn’t have time to conduct research and requires detailed information about the topic.

Example of a semi-structured interview question:

Here’s an example of a semi-structured marketing job interviews question:

- Can you tell us about the marketing work you’ve done?

- What do you think are the most important parts of a marketing campaign that works?

- Tell me about a campaign you worked on that you’re very proud of.

- How do you do research on the market and look at data to help you make marketing decisions?

- Can you tell us about a time when you had to change your marketing plan because of something that didn’t go as planned?

- How do you figure out if a marketing campaign worked?

- Can you talk about how you’ve used social media to market?

- How do you ensure your marketing message gets through to the people you want to hear it?

- Can you tell us about a time when you had to run a marketing campaign on a small budget?

- How do you keep up with changes and trends in marketing?

Advantages of semi-structured interviews:

- Questions from semi-structured interview questions are prepared before the scheduled interview, giving the researcher time to prepare and analyze the questions.

- It is flexible to an extent while maintaining the research guidelines.

- Unlike a structured interview, researchers can express the interview questions in the preferred format.

- Reliable qualitative data can be collected via these interviews.

- The flexible structure of the interview.

Learn more: Quantitative Data

Disadvantages of semi-structured interviews:

- Participants may question the reliability factor of these interviews due to the flexibility offered.

- Comparing two different answers becomes difficult as the guideline for conducting interviews is not entirely followed. No two questions will have the exact same structure, and the result will be an inability to compare are infer results.

3. Unstructured Interviews:

Also called in-depth interviews , unstructured interviews are usually described as conversations held with a purpose in mind – to gather data about the research study. These interviews have the least number of questions as they lean more towards a normal conversation but with an underlying subject.

The main objective of most researchers using unstructured interviews is to build a bond with the respondents, due to which there is a high chance that the respondents will be 100% truthful with their answers. There are no guidelines for the researchers to follow. So they can approach the participants ethically to gain as much information as possible about their research topic.

Since there are no guidelines for these interviews, a researcher is expected to keep their approach in check so that the respondents do not sway away from the main research motive.

For a researcher to obtain the desired outcome, he/she must keep the following factors in mind:

- The intent of the interview.

- The interview should primarily take into consideration the participant’s interests and skills.

- All the conversations should be conducted within the permissible limits of research, and the researcher should try and stick by these limits.

- The researcher’s skills and knowledge should match the interview’s purpose.

- Researchers should understand the dos and don’ts of it.

Example of an unstructured interview question:

Here’s an example of a question asked in an unstructured interview:

- Can you tell me about when you had to deal with something hard and how you did it?

- What are some of the things you’re most proud of, and what did you learn from them?

- How do you deal with ambiguity or not knowing what to do at work?

- Can you describe how you lead and how you get your team going?

- Tell me about a time when you had to take a chance and how it turned out.

- What do you think are the most important qualities for success in this role?

- How do you deal with setbacks or failures, and what do you learn from them?

- Can you tell me about a time when you had to solve a problem by thinking outside the box?

- What do you think makes you different from the other people who want this job?

- Can you tell me about a time when you had to make a hard choice and how you made that choice?

Advantages of Unstructured Interviews:

- Due to this type of interview’s informal nature, it becomes extremely easy for researchers to try and develop a friendly rapport with the participants. This leads to gaining insights in extreme detail without much conscious effort.

- The participants can clarify all their doubts about the questions, and the researcher can take each opportunity to explain his/her intention for better answers.

- There are no questions that the researcher has to abide by, and this usually increases the flexibility of the entire research process.

Disadvantages of Unstructured Interviews:

- Researchers take time to execute these interviews because there is no structure to the interview process.

- The absence of a standardized set of questions and guidelines indicates that its reliability of it is questionable.

- The ethics involved in these interviews are often considered borderline upsetting.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research & Qualitative Data Collection

Other Types of Interviews

Besides the 3 basic interview types, we have already mentioned there are more. Here are some other interview types that are commonly used in a job interview:

Behavioral Interview

During this type of interview, candidates are asked to give specific examples of how they have acted in the past. The idea behind this kind of interview is that what someone did in the past can be a sign of how they will act in the future. And by this interview, the company can also understand the interviewee’s behavior through body language.

Panel Interview

During a panel interview, three or more interviewers usually ask questions and evaluate the candidate’s answers as a group. This is a good way to get a full picture of a candidate’s skills and suitability for the job.

Group Types of Interviews

Multiple people are interviewed at the same time in group interviews. This form of interview often focus groups that are utilized on entry-level positions or employment in customer service to examine how well candidates get along with others and function as a team.

Case Interview

During a case interview, candidates are given a business problem or scenario and asked to think about how to solve it. In the consulting and finance fields, this kind of interview is common.

Technical Interview

A candidate’s technical skills and knowledge are tested during a technical interview, usually in fields like engineering or software development. Most of the time, candidates are asked to solve problems or complete technical tasks.

Stress Interview

During a stress interview, candidates are put under pressure or asked difficult or confrontational questions on purpose to see how they react in stressful situations. This kind of interview is used to see how well a candidate can deal with stress and hard situations.

Methods of Research Interviews:

There are four methods to conduct research interviews, each of which is peculiar in its application and can be used according to the research study requirement.

Personal Interviews:

Personal interviews are one of the most used types of interviews, where the questions are asked personally directly to the respondent as a form of an individual interview. One of the many in-person interviews is a lunch interview, which is frequently better suited for casual inquiries and discussions.

For this, a researcher can have a guide to online surveys to take note of the answers. A researcher can design his/her survey in such a way that they take notes of the comments or points of view that stands out from the interviewee. It can be a one-on-one interview as well.

- Higher response rate.

- When the interviewees and respondents are face-to-face, there is a way to adapt the questions if this is not understood.

- More complete answers can be obtained if there is doubt on both sides or a remarkable piece of information is detected.

- The researcher has an opportunity to detect and analyze the interviewee’s body language at the time of asking the questions and taking notes about it.

Disadvantages:

- They are time-consuming and extremely expensive.

- They can generate distrust on the part of the interviewee since they may be self-conscious and not answer truthfully.

- Contacting the interviewees can be a real headache, either scheduling an appointment in workplaces or going from house to house and not finding anyone.

- Therefore, many interviews are conducted in public places like shopping centers or parks. Even consumer studies take advantage of these sites to conduct interviews or surveys and give incentives, gifts, and coupons. In short, There are great opportunities for online research in shopping centers.

- Among the advantages of conducting such types of interviews is that the respondents will have more fresh information if the interview is conducted in the context and with the appropriate stimuli so that researchers can have data from their experience at the scene of the events immediately and first hand. The interviewer can use an online survey through a mobile device that will undoubtedly facilitate the entire process.

Telephonic Type of Interviews:

Phonic interviews are widely used and easily combined with online surveys to conduct research effectively.

Advantages:

- To find the interviewees, it is enough to have their phone numbers on hand.

- They are usually lower cost.

- The information is collected quickly.

- Having a personal contact can also clarify doubts or give more details of the questions.

- Many times researchers observe that people do not answer phone calls because it is an unknown number for the respondent or simply already changed their place of residence and they cannot locate it, which causes a bias in the interview.

- Researchers also face that they simply do not want to answer and resort to pretexts such as they are busy to answer, they are sick, they do not have the authority to answer the questions asked, they have no interest in answering, or they are afraid of putting their security at risk.

- One of the aspects that should be taken care of in these types of interviews is the kindness with which the interviewers address the respondents in order to get them to cooperate more easily with their answers. Good communication is vital for the generation of better answers.

Learn More: Data Collection Methods: Types & Examples

Email or Web Page Types of Interviews:

Online research is growing more and more because consumers are migrating to a more virtual world, and it is best for each researcher to adapt to this change.

The increase in people with Internet access has made it popular that interviews via email or web page stand out among the types of interviews most used today. For this nothing better than an online survey.

More and more consumers are turning to online shopping, which is why they are a great niche to be able to carry out an interview that will generate information for the correct decision-making.

Advantages of email surveys:

- Speed in obtaining data

- The respondents respond according to their time, when they want, and where they decide.

- Online surveys can be mixed with other research methods or using some of the previous interview models. They are tools that can perfectly complement and pay for the project.

- A researcher can use a variety of questions and logic to create graphs and reports immediately.

Disadvantages of email survey:

- Low response rates

- Limited access to certain populations

- Potential for spam filters

- Lack of personal touch

What to Avoid in Different Types of Interviews

Try not to do any of the following things when you’re in an interview:

- Don’t blame your previous managers, coworkers, or companies. This will make a bad impression on the interviewer and show that you are not accountable.

- Do not go to the interview without knowing anything about the company you are interviewing for. Interviewers will think you don’t care about learning about the company if you don’t know anything.

- Don’t fidget with things because that shows you lack self-confidence and focus.

- Stop checking the time because it shows that you have something more important to do and that you don’t give the interview much importance.

Related Questions of Interviews

After the interview is over, you might also get a chance to ask some questions. You should make the most of this chance to learn useful things from the interviewer. Based on what you’ve learned, you can then decide if the company and the job are a good fit for you. You can ask the interviewer questions about the company or about the job role.

Here are some common but important questions to ask in an interview:

- What do you anticipate from team members in this role?

- What does a typical day look like for an employee in this role?

- What qualities are essential for success in this position?

- How is success measured for this position?

- How does this job profile relate to the organization’s overarching objectives?

- What are your company’s guiding principles?

- Which departments will I work closely with throughout my time in this profile?

Learn more: Quantitative Research

To summarize the discussion, an effective interview will be one that provides researchers with the necessary data to know the object of study and that this information is applicable to the decisions researchers make.

Undoubtedly, the objective of the research will set the pattern of what types of interviews are best for data collection. Based on the research design , a researcher can plan and test the questions, for instance, if the questions are correct and if the survey flows in the best way.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

In addition, other types of research can be used under specific circumstances.

For example, there are no connections or adverse situations to carry out surveyors. In these types of occasions, it is necessary to conduct field research, which can not be considered an interview if not rather a completely different methodology.

QuestionPro is a flexible online survey platform that can help researchers do different kinds of interviews, like structured, semi-structured, unstructured, phone interview, group interview, etc. It gives researchers a flexible platform that can be changed to fit their needs and the needs of their research project.

QuestionPro can help researchers get detailed and useful information from participants using features like skip logic, piping, and live chat. Also, the platform is easy to use and get to, making it a useful tool for researchers to use in their work.

LEARN ABOUT: Candidate Experience Survey

Overall, QuestionPro can be helpful for researchers who want to do good interviews and collect good project data.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

The 3 main types of interviews are 1. Structured interviews 2. Semi-structured interviews 3. Unstructured interviews

There are different ways to conduct an interview, and each one can add depth and substance to the information the interviewer gathers by asking questions. We discuss four interview methods: situational, professional behavior profiling, stress, and behavioral.

Face-to-face means in-person interviews are the most common type of interview. It’s about getting a good sense of the candidate by focusing on them directly. But it also allows the person interviewed to talk freely and ask questions.

Personal interviews, phone interviews, email or web page interviews, and a combination of these methods are the four types of research interviews.

MORE LIKE THIS

Jotform vs SurveyMonkey: Which Is Best in 2024

Aug 15, 2024

360 Degree Feedback Spider Chart is Back!

Aug 14, 2024

Jotform vs Wufoo: Comparison of Features and Prices

Aug 13, 2024

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Essay Papers Writing Online

10 essential tips for crafting an effective interview essay.

Unlock the magic of storytelling by capturing the essence of human experiences through the power of interviews. Going beyond just words on a page, an interview essay transforms a simple conversation into a captivating narrative that engages readers on a deep and emotional level. By delving into the intricacies of someone’s thoughts, experiences, and insights, an interview essay brings a unique perspective to the table, allowing readers to immerse themselves in a world of diverse voices and compelling narratives.

With the interview essay, you have the opportunity to weave a rich tapestry of perspectives, uncovering hidden gems of wisdom that often go unnoticed in everyday life. As you engage in thoughtful conversations with individuals from different walks of life, you unravel unique stories that have the power to educate, inspire, and enlighten readers. Through the artful use of quotes, anecdotes, and vivid descriptions, an interview essay breathes life into the pages, creating an intimate connection between the reader and the interview subject.

Mastering the art of the interview essay requires not only strong interviewing skills but also empathy, curiosity, and the ability to connect with people on a deeper level. By listening intently and asking thought-provoking questions, you can encourage interviewees to open up, share their experiences, and provide insights that transcend the surface level. With each interview, you embark on a journey of discovery, peeling back the layers of someone’s life and inviting readers to join you on this transformative expedition.

Choosing the Right Interviewee

When embarking on the journey of conducting an interview, the first and crucial step is selecting the right interviewee. This step requires careful consideration and evaluation to ensure a successful and meaningful interview. The interviewee plays a pivotal role in shaping the tone and direction of the interview, bringing unique perspectives, experiences, and insights to the conversation.

One important aspect to consider when choosing an interviewee is their expertise and knowledge in the subject matter. Look for individuals who possess deep understanding and experience in the area of interest. This will contribute to the richness and authenticity of the interview, allowing for in-depth discussions and a deeper exploration of the topic.

Another factor to consider is the interviewee’s articulation and communication skills. A great interviewee should be able to express their thoughts and ideas clearly and effectively. Look for individuals who have the ability to convey their thoughts in a coherent and concise manner, as it will enhance the overall quality of the interview.

Furthermore, it is valuable to select an interviewee who is open-minded and willing to share their perspectives openly. This fosters an environment of trust and encourages candid discussions during the interview. Seek interviewees who are comfortable expressing their opinions and are receptive to exploring different viewpoints.

Additionally, it is essential to consider the interviewee’s availability and willingness to participate in the interview. Ensure that the individual is committed and available for the agreed-upon interview date and time. This will ensure a smooth and hassle-free process, allowing for ample preparations and scheduling.

Overall, selecting the right interviewee is a vital step in the interview process. By considering factors such as expertise, communication skills, openness, and availability, you can ensure that your interview is engaging, informative, and insightful.

Preparing a List of Questions

When it comes to conducting an interview, one of the most important steps is preparing a thoughtful and engaging list of questions. A well-crafted set of questions can not only help you gather the necessary information for your interview essay, but it can also create a dynamic and engaging conversation with your interviewee.

To begin, it’s important to consider the purpose of your interview and what you hope to learn from your interviewee. Whether you are writing a profile on a notable individual or exploring a specific topic, your questions should be targeted and focused. Think about the key information you want to gather and structure your questions accordingly.

When crafting your questions, it’s also important to strike a balance between open-ended and specific inquiries. Open-ended questions allow your interviewee to share their thoughts and experiences in more depth, while specific questions can help guide the conversation and ensure you obtain the information you need.

Additionally, it’s helpful to consider the interviewee’s background and expertise when formulating your questions. Tailoring your questions to their unique perspective and experiences can help elicit more thoughtful and insightful responses. Doing some preliminary research on your interviewee can provide valuable context and inform the types of questions you ask.

Lastly, don’t be afraid to be flexible and adapt your questions in the moment. Interviewing is a dynamic process, and sometimes the best insights and stories come from unexpected avenues of conversation. Allow the interview to unfold naturally and be prepared to adjust your questions based on the flow of the dialogue.

Remember, the goal of preparation is not to rigidly stick to a script, but rather to have a well-thought-out framework that can guide the conversation and help you achieve your objectives as an interviewer.

Conducting the Interview

When it comes to the process of gathering information for your interview essay, the stage of conducting the interview is crucial. This is the moment when you will have the opportunity to engage with your interviewee and extract valuable insights to create a compelling narrative. The effectiveness of your interview will greatly depend on your preparation, approach, and ability to establish trust and rapport with the person you are interviewing.

Preparation: Before conducting the interview, it is essential to thoroughly research and familiarize yourself with the topic and the person you will be interviewing. This will not only help you ask informed and relevant questions but also show your interviewee that you are genuinely interested and invested in the conversation. Take the time to identify key areas you want to explore, as well as any specific questions you may have.

Approach: When you actually sit down with your interviewee, it is important to approach the interview with a professional yet friendly demeanor. Introduce yourself and explain the purpose of the interview, highlighting the value it will bring. Make sure to actively listen, allowing the conversation to flow naturally. Use open-ended questions to encourage your interviewee to share their thoughts and experiences in depth. Additionally, keep in mind that body language and non-verbal cues play a significant role in building rapport, so strive to maintain eye contact and exhibit attentive body language.

Establishing Trust and Rapport: To create a comfortable and trusting environment, it is crucial to show genuine interest, empathy, and respect for your interviewee’s perspectives and experiences. Actively listening and responding empathetically will help build rapport and allow your interviewee to open up and share their insights more freely. It is also essential to be mindful of any sensitive topics or boundaries that your interviewee may have and to approach them with sensitivity and tact.

By carefully preparing for the interview, approaching it with professionalism and empathy, and focusing on building trust and rapport, you will set the stage for a successful and insightful conversation that will serve as a foundation for your interview essay.

Transcribing and Organizing the Material

One of the essential steps in creating a well-rounded interview essay is the transcription and organization of the material gathered during the interview process. After conducting the interview, the next crucial task is to transcribe the recorded audio or written notes into a readable format.