Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

Climate change

- Climate change is directly contributing to humanitarian emergencies from heatwaves, wildfires, floods, tropical storms and hurricanes and they are increasing in scale, frequency and intensity.

- Research shows that 3.6 billion people already live in areas highly susceptible to climate change. Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year, from undernutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress alone.

- The direct damage costs to health (excluding costs in health-determining sectors such as agriculture and water and sanitation) is estimated to be between US$ 2–4 billion per year by 2030.

- Areas with weak health infrastructure – mostly in developing countries – will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.

- Reducing emissions of greenhouse gases through better transport, food and energy use choices can result in very large gains for health, particularly through reduced air pollution.

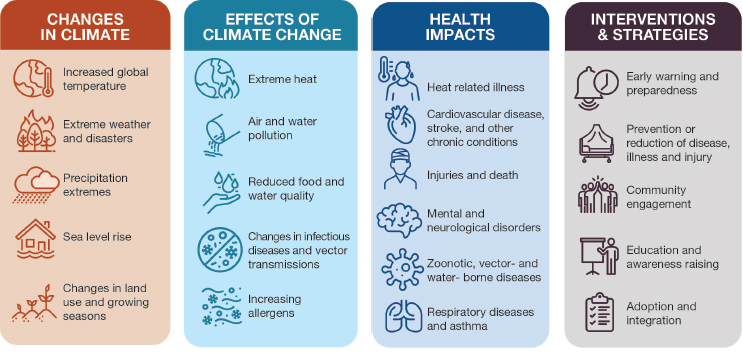

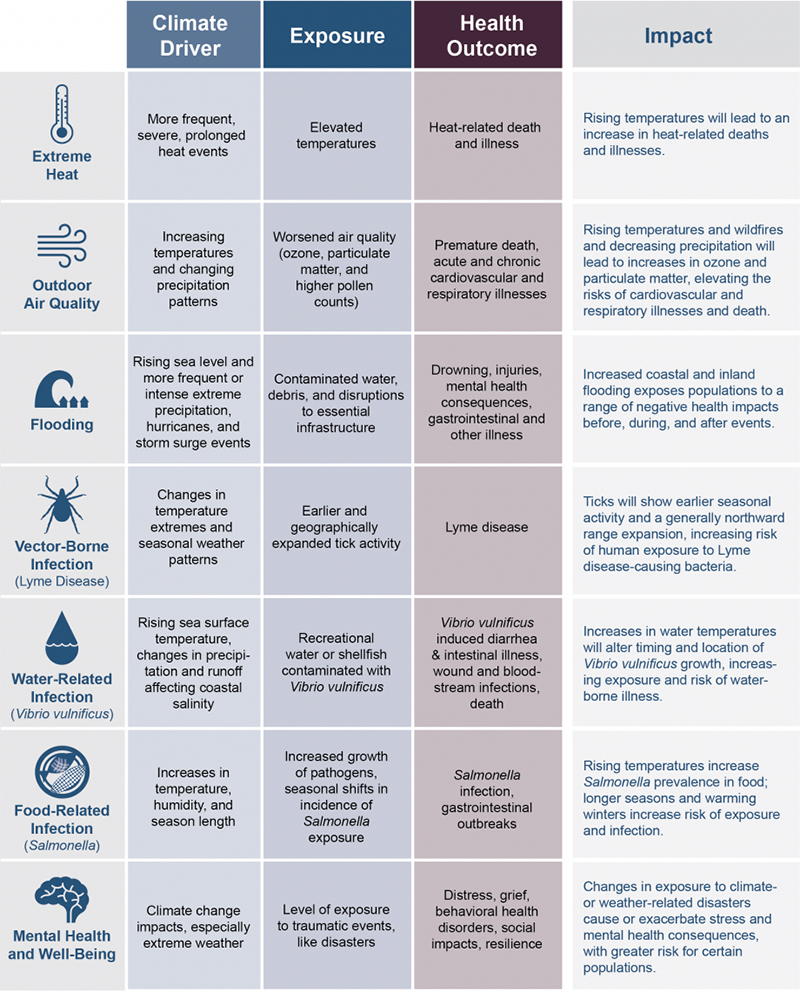

Climate change presents a fundamental threat to human health. It affects the physical environment as well as all aspects of both natural and human systems – including social and economic conditions and the functioning of health systems. It is therefore a threat multiplier, undermining and potentially reversing decades of health progress. As climatic conditions change, more frequent and intensifying weather and climate events are observed, including storms, extreme heat, floods, droughts and wildfires. These weather and climate hazards affect health both directly and indirectly, increasing the risk of deaths, noncommunicable diseases, the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, and health emergencies.

Climate change is also having an impact on our health workforce and infrastructure, reducing capacity to provide universal health coverage (UHC). More fundamentally, climate shocks and growing stresses such as changing temperature and precipitation patterns, drought, floods and rising sea levels degrade the environmental and social determinants of physical and mental health. All aspects of health are affected by climate change, from clean air, water and soil to food systems and livelihoods. Further delay in tackling climate change will increase health risks, undermine decades of improvements in global health, and contravene our collective commitments to ensure the human right to health for all.

Climate change impacts on health

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) concluded that climate risks are appearing faster and will become more severe sooner than previously expected, and it will be harder to adapt with increased global heating.

It further reveals that 3.6 billion people already live in areas highly susceptible to climate change. Despite contributing minimally to global emissions, low-income countries and small island developing states (SIDS) endure the harshest health impacts. In vulnerable regions, the death rate from extreme weather events in the last decade was 15 times higher than in less vulnerable ones.

Climate change is impacting health in a myriad of ways, including by leading to death and illness from increasingly frequent extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, storms and floods, the disruption of food systems, increases in zoonoses and food-, water- and vector-borne diseases, and mental health issues. Furthermore, climate change is undermining many of the social determinants for good health, such as livelihoods, equality and access to health care and social support structures. These climate-sensitive health risks are disproportionately felt by the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, including women, children, ethnic minorities, poor communities, migrants or displaced persons, older populations, and those with underlying health conditions.

Figure: An overview of climate-sensitive health risks, their exposure pathways and vulnerability factors. Climate change impacts health both directly and indirectly, and is strongly mediated by environmental, social and public health determinants.

Although it is unequivocal that climate change affects human health, it remains challenging to accurately estimate the scale and impact of many climate-sensitive health risks. However, scientific advances progressively allow us to attribute an increase in morbidity and mortality to global warming, and more accurately determine the risks and scale of these health threats.

WHO data indicates 2 billion people lack safe drinking water and 600 million suffer from foodborne illnesses annually, with children under 5 bearing 30% of foodborne fatalities. Climate stressors heighten waterborne and foodborne disease risks. In 2020, 770 million faced hunger, predominantly in Africa and Asia. Climate change affects food availability, quality and diversity, exacerbating food and nutrition crises.

Temperature and precipitation changes enhance the spread of vector-borne diseases. Without preventive actions, deaths from such diseases, currently over 700 000 annually, may rise. Climate change induces both immediate mental health issues, like anxiety and post-traumatic stress, and long-term disorders due to factors like displacement and disrupted social cohesion.

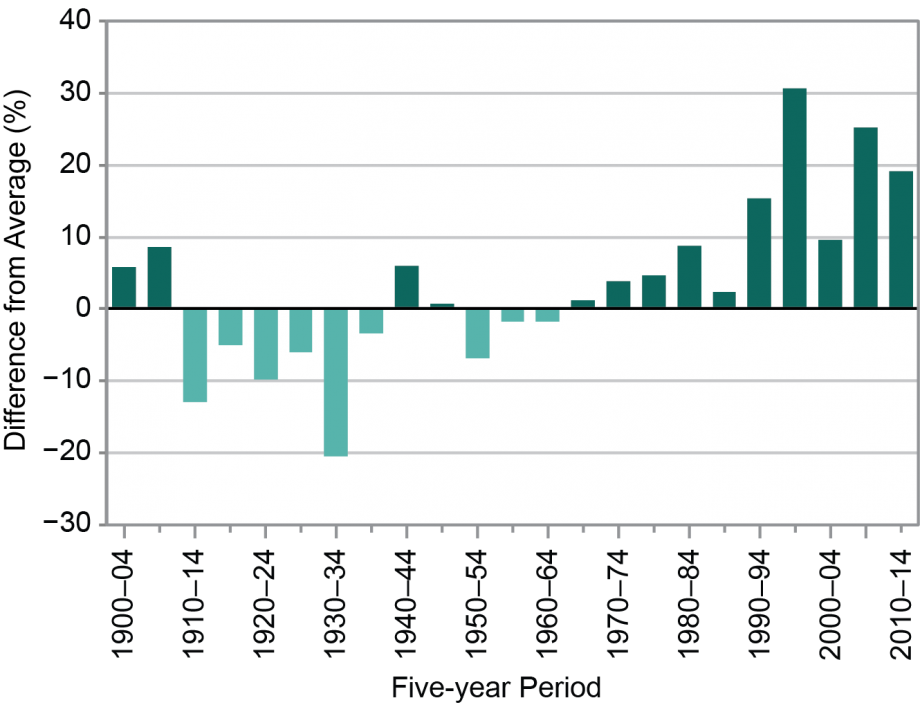

Recent research attributes 37% of heat-related deaths to human-induced climate change. Heat-related deaths among those over 65 have risen by 70% in two decades. In 2020, 98 million more experienced food insecurity compared to the 1981–2010 average. The WHO conservatively projects 250 000 additional yearly deaths by the 2030s due to climate change impacts on diseases like malaria and coastal flooding. However, modelling challenges persist, especially around capturing risks like drought and migration pressures.

The climate crisis threatens to undo the last 50 years of progress in development, global health and poverty reduction, and to further widen existing health inequalities between and within populations. It severely jeopardizes the realization of UHC in various ways, including by compounding the existing burden of disease and by exacerbating existing barriers to accessing health services, often at the times when they are most needed. Over 930 million people – around 12% of the world’s population – spend at least 10% of their household budget to pay for health care. With the poorest people largely uninsured, health shocks and stresses already currently push around 100 million people into poverty every year, with the impacts of climate change worsening this trend.

Climate change and equity

In the short- to medium-term, the health impacts of climate change will be determined mainly by the vulnerability of populations, their resilience to the current rate of climate change and the extent and pace of adaptation. In the longer-term, the effects will increasingly depend on the extent to which transformational action is taken now to reduce emissions and avoid the breaching of dangerous temperature thresholds and potential irreversible tipping points.

While no one is safe from these risks, the people whose health is being harmed first and worst by the climate crisis are the people who contribute least to its causes, and who are least able to protect themselves and their families against it: people in low-income and disadvantaged countries and communities.

Addressing climate change's health burden underscores the equity imperative: those most responsible for emissions should bear the highest mitigation and adaptation costs, emphasizing health equity and vulnerable group prioritization.

Need for urgent action

To avert catastrophic health impacts and prevent millions of climate change-related deaths, the world must limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. Past emissions have already made a certain level of global temperature rise and other changes to the climate inevitable. Global heating of even 1.5°C is not considered safe, however; every additional tenth of a degree of warming will take a serious toll on people’s lives and health.

WHO response

WHO’s response to these challenges centres around 3 main objectives:

- Promote actions that both reduce carbon emissions and improve health: supporting a rapid and equitable transition to a clean energy economy; ensuring that health is central to climate change mitigation policy; accelerating mitigation actions that bring the greatest health gains; and mobilizing the strength of the health community to drive policy change and build public support.

- Build better, more climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health systems: ensuring core services, environmental sustainability and climate resilience as central components of UHC and primary health care (PHC); supporting health systems to leapfrog to cheaper, more reliable and cleaner solutions, while decarbonizing high-emitting health systems; and mainstreaming climate resilience and environmental sustainability into health service investments, including the capacity of the health workforce.

- Protect health from the wide range of impacts of climate change : assessing health vulnerabilities and developing health plans; integrating climate risk and implementing climate-informed surveillance and response systems for key risks, such as extreme heat and infectious disease; supporting resilience and adaptation in health-determining sectors such as water and food; and closing the financing gap for health adaptation and resilience.

Leadership and Raising Awareness : WHO leads in emphasizing climate change's health implications, aiming to centralize health in climate policies, including through the UNFCCC. Partnering with major health agencies, health professionals and civil society, WHO strives to embed climate change in health priorities like UHC and target carbon neutrality by 2030.

Evidence and Monitoring : WHO, with its network of global experts, contributes global evidence summaries, provides assistance to nations in their assessments, and monitors progress. The emphasis is on deploying effective policies and enhancing access to knowledge and data.

Capacity Building and Country Support : Through WHO offices, support is given to ministries of health, focusing on collaboration across sectors, updated guidance, hands-on training, and support for project preparation and execution as well as for securing climate and health funding. WHO leads the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH) , bringing together a range of health and development partners, to support countries in achieving their commitments to climate-resilient and low carbon health systems.

Why climate change is still the greatest threat to human health

Polluted air and steadily rising temperatures are linked to health effects ranging from increased heart attacks and strokes to the spread of infectious diseases and psychological trauma.

People around the world are witnessing firsthand how climate change can wreak havoc on the planet. Steadily rising average temperatures fuel increasingly intense wildfires, hurricanes, and other disasters that are now impossible to ignore. And while the world has been plunged into a deadly pandemic, scientists are sounding the alarm once more that climate change is still the greatest threat to human health in recorded history .

As recently as August—when wildfires raged in the United States, Europe, and Siberia—World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement that “the risks posed by climate change could dwarf those of any single disease.”

On September 5, more than 200 medical journals released an unprecedented joint editorial that urged world leaders to act. “The science is unequivocal,” they write. “A global increase of 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average and the continued loss of biodiversity risk catastrophic harm to health that will be impossible to reverse.”

Despite the acute dangers posed by COVID-19, the authors of the joint op-ed write that world governments “cannot wait for the pandemic to pass to rapidly reduce emissions.” Instead, they argue, everyone must treat climate change with the same urgency as they have COVID-19.

Here’s a look at the ways that climate change can affect your health—including some less obvious but still insidious effects—and why scientists say it’s not too late to avert catastrophe.

Air pollution

Climate change is caused by an increase of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere, mostly from fossil fuel emissions. But burning fossil fuels can also have direct consequences for human health. That’s because the polluted air contains small particles that can induce stroke and heart attacks by penetrating the lungs and heart and even traveling into the bloodstream. Those particles might harm the organs directly or provoke an inflammatory response from the immune system as it tries to fight them off. Estimates suggest that air pollution causes anywhere between 3.6 million and nine million premature deaths a year.

“The numbers do vary,” says Andy Haines , professor of environmental change and public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and author of the recently published book Planetary Health . “But they all agree that it’s a big public health burden.”

People over the age of 65 are most susceptible to the harmful effects of air pollution, but many others are at risk too, says Kari Nadeau , director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University. People who smoke or vape are at increased risk, as are children with asthma.

Air pollution also has consequences for those with allergies. Carbon dioxide increases the acidity of the air, which then pulls more pollen out from plants. For some people, this might just mean that they face annoyingly long bouts of seasonal allergies. But for others, it could be life-threatening.

“For people who already have respiratory disease, boy is that a problem,” Nadeau says. When pollen gets into the respiratory pathway, the body creates mucus to get rid of it, which can then fill up and suffocate the lungs.

Even healthy people can have similar outcomes if pollen levels are especially intense. In 2016, in the Australian state of Victoria, a severe thunderstorm combined with high levels of pollen to induce what The Lancet has described as “the world’s largest and most catastrophic epidemic of thunderstorm asthma.” So many residents suffered asthma attacks that emergency rooms were overwhelmed—and at least 10 people died as a result.

Climate change is also causing wildfires to get worse, and wildfire smoke is especially toxic. As one recent study showed, fires can account for 25 percent of dangerous air pollution in the U.S. Nadeau explains that the smoke contains particles of everything that the fire has consumed along its path—from rubber tires to harmful chemicals. These particles are tiny and can penetrate even deeper into a person’s lungs and organs. ( Here’s how breathing wildfire smoke affects the body .)

Extreme heat

Heat waves are deadly, but researchers at first didn’t see direct links between climate change and the harmful impacts of heat waves and other extreme weather events. Haines says the evidence base has been growing. “We have now got a number of studies which has shown that we can with high confidence attribute health outcomes to climate change,” he says.

Most recently, Haines points to a study published earlier this year in Nature Climate Change that attributes more than a third of heat-related deaths to climate change. As National Geographic reported at the time , the study found that the human toll was even higher in some countries with less access to air conditioning or other factors that render people more vulnerable to heat. ( How climate change is making heat waves even deadlier .)

That’s because the human body was not designed to cope with temperatures above 98.6°F, Nadeau says. Heat can break down muscles. The body does have some ways to deal with the heat—such as sweating. “But when it’s hot outside all the time, you cannot cope with that, and your heart muscles and cells start to literally die and degrade,” she says.

If you’re exposed to extreme heat for too long and are unable to adequately release that heat, the stress can cause a cascade of problems throughout the body. The heart has to work harder to pump blood to the rest of the organs, while sweat leeches the body of necessary minerals such as sodium and potassium. The combination can result in heart attacks and strokes .

Dehydration from heat exposure can also cause serious damage to the kidneys, which rely on water to function properly. For people whose kidneys are already beginning to fail—particularly older adults—Nadeau says that extreme heat can be a death sentence. “This is happening more and more,” she says.

Studies have also drawn links between higher temperatures and preterm birth and other pregnancy complications. It’s unclear why, but Haines says that one hypothesis is that extreme heat reduces blood flow to the fetus.

Food insecurity

One of the less direct—but no less harmful—ways that climate change can affect health is by disrupting the world’s supply of food.

You May Also Like

2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

Extreme heat is the future. Here are 10 practical ways to manage it.

The U.S. plans to limit PFAS in drinking water. What does that really mean?

Climate change both reduces the amount of food that’s available and makes it less nutritious. According to an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report , crop yields have already begun to decline as a result of rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. Meanwhile, studies have shown that increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can leech plants of zinc, iron, and protein—nutrients that humans need to survive.

Malnutrition is linked to a variety of illnesses, including heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. It can also increase the risk of stunting, or impaired growth , in children, which can harm cognitive function.

Climate change also imperils what we eat from the sea. Rising ocean temperatures have led many fish species to migrate toward Earth’s poles in search of cooler waters. Haines says that the resulting decline of fish stocks in subtropic regions “has big implications for nutrition,” because many of those coastal communities depend on fish for a substantial amount of the protein in their diets.

This effect is likely to be particularly harmful for Indigenous communities, says Tiff-Annie Kenny, a professor in the faculty of medicine at Laval University in Quebec who studies climate change and food security in the Canadian Arctic. It’s much more difficult for these communities to find alternative sources of protein, she says, either because it’s not there or because it’s too expensive. “So what are people going to eat instead?” she asks.

Infectious diseases

As the planet gets hotter, the geographic region where ticks and mosquitoes like to live is getting wider. These animals are well-known vectors of diseases such as the Zika virus, dengue fever, and malaria. As they cross the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, Nadeau says, mosquitoes and ticks bring more opportunities for these diseases to infect greater swaths of the world.

“It used to be that they stayed in those little sectors near the Equator, but now unfortunately because of the warming of northern Europe and Canada, you can find Zika in places you wouldn’t have expected,” Nadeau says.

In addition, climate conditions such as temperature and humidity can impact the life cycle of mosquitoes. Haines says there’s particularly good evidence showing that, in some regions, climate change has altered these conditions in ways that increase the risk of mosquitos transmitting dengue .

There are also several ways in which climate change is increasing the risk of diseases that can be transmitted through water, such as cholera, typhoid fever, and parasites. Sometimes that’s fairly direct, such as when people interact with dirty floodwaters. But Haines says that drought can have indirect impacts when people, say, can’t wash their hands or are forced to drink from dodgier sources of freshwater.

Mental health

A common result of any climate-linked disaster is the toll on mental health. The distress caused by drastic environmental change is so significant that it has been given its own name— solastalgia .

Nadeau says that the effects on mental health have been apparent in her studies of emergency room visits arising from wildfires in the western U.S. People lose their homes, their jobs, and sometimes their loved ones, and that takes an immediate toll. “What’s the fastest acute issue that develops? It’s psychological,” she says. Extreme weather events such as wildfires and hurricanes cause so much stress and anxiety that they can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder and even suicide in the long run.

Another common factor is that climate change causes disproportionate harm to the world’s most vulnerable people. On September 2, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released an analysis showing that racial and ethnic minority communities are particularly at risk . According to the report, if temperatures rise by 2°C (3.6°F), Black people are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in related deaths. Another 34 percent are more likely to live in areas with a rise in childhood asthma.

Further, the effects of climate change don’t occur in isolation. At any given time, a community might face air pollution, food insecurity, disease, and extreme heat all at once. Kenny says that’s particularly devastating in communities where the prevalence of food insecurity and poverty are already high. This situation hasn’t been adequately studied, she says, because “it’s difficult to capture these shocks that climate can bring.”

Why there’s reason for hope

In recent years, scientists and environmental activists have begun to push for more research into the myriad health effects of climate change. “One of the striking things is there’s been a real dearth of funding for climate change and health,” Haines says. “For that reason, some of the evidence we have is still fragmentary.”

Still, hope is not lost. In the Paris Agreement, countries around the world have pledged to limit global warming to below 2°C (3.6°F)—and preferably to 1.5°C (2.7°F)—by cutting their emissions. “When you reduce those emissions, you benefit health as well as the planet,” Haines says.

Meanwhile, scientists and environmental activists have put forward solutions that can help people adapt to the health effects of climate change. These include early heat warnings and dedicated cooling centers, more resilient supply chains, and freeing healthcare facilities from dependence on the electric grid.

Nadeau argues that the COVID-19 pandemic also presents an opportunity for world leaders to think bigger and more strategically. For example, the pandemic has laid bare problems with efficiency and equity that have many countries restructuring their healthcare facilities. In the process, she says, they can look for new ways to reduce waste and emissions, such as getting more hospitals using renewable energy.

“This is in our hands to do,” Nadeau says. “If we don’t do anything, that would be cataclysmic.”

Related Topics

- AIR POLLUTION

- WATER QUALITY

- NATURAL DISASTERS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- CLIMATE CHANGE

Here’s what extreme heat does to the body

This summer's extreme weather is a sign of things to come

Some antibiotics are no longer as effective. That's as concerning as it sounds.

This African lake may literally explode—and millions are at risk

We got rid of BPA in some products—but are the substitutes any safer?

- Photography

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Ways to Give

- Contact an Expert

- Explore WRI Perspectives

Filter Your Site Experience by Topic

Applying the filters below will filter all articles, data, insights and projects by the topic area you select.

- All Topics Remove filter

- Climate filter site by Climate

- Cities filter site by Cities

- Energy filter site by Energy

- Food filter site by Food

- Forests filter site by Forests

- Freshwater filter site by Freshwater

- Ocean filter site by Ocean

- Business filter site by Business

- Economics filter site by Economics

- Finance filter site by Finance

- Equity & Governance filter site by Equity & Governance

Search WRI.org

Not sure where to find something? Search all of the site's content.

How Climate Change Affects Health and How Countries Can Respond

- Climate Resilience

- adaptation finance

- climate change

- climatewatch-pinned

Since early 2020, the world’s attention has been on the global coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic continues to put massive stress on existing health systems, exposing their fault lines. As nations think about how to make health systems more resilient to current and future threats, one threat must not be overlooked: climate change is also impacting human health and straining heavily burdened health services everywhere.

Health-related risks linked to climate change range widely, from increased likelihood of transmitting vector-borne diseases to decreased access to services as a result of natural disasters. For example, air pollution — the sources of which are often the same as those that drive climate change — kills 4.2 million people every year and makes countless more sick and debilitated. Ground-level ozone, a key component of air pollution, is even more harmful to human health when temperatures are higher. Climate change events like hurricanes and floods can also destroy or limit access to health infrastructure and services.

Human health is a priority in 59% of countries’ national climate adaptation commitments under the Paris Agreement and close to half of countries acknowledge the negative health effects of climate change. However, countries struggle to understand specific climate risks to health, as well as how to identify and fund comprehensive health adaptation actions. Only 0.5% of multilateral climate finance targets health projects. Domestic funding for this issue is also minimal or nonexistent.

This is unacceptable considering the need for resilient and stable health systems.

A new paper by WRI showcases how countries can integrate health-related risks from climate change into their national climate and health strategies and put them into action. Doing so is essential, not only in preventing the worst impacts of climate change, but in keeping people healthy and nations prosperous.

How Does Climate Change Affect Human Health?

There are many ways health risks link to climate change, which often intersect with one another. Common risks include:

1. Increased risk of vector- and water-borne diseases.

Climate change is redistributing and increasing the optimal habitats for mosquitoes and other pathogens that carry disease. In some cases, these pathogens are bringing infectious diseases into communities that had not encountered them before. For example, warmer temperatures expand mosquito breeding ranges, causing malaria to shift upslope into new villages.

One study projects that, because of climate change, up to an additional 51.3 million people will be at risk from exposure to malaria in Western Africa by 2050. These shifts can heighten suffering, increase countries’ burdens of disease and cause epidemics. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one-sixth of illness and disability suffered globally is due to vector-borne diseases, which are predicted to spread due to climate change.

Climate effects related to changing rainfall patterns, water quality and water scarcity can also trigger or worsen diseases within a country. For example, Ghana is now facing a higher prevalence of cholera, diarrhea, malaria and meningitis because flooding contaminates and exacerbates sanitation problems and water quality. Cholera outbreaks in Ghana have a high fatality rate and are particularly frequent during the rainy seasons and in coastal regions.

2. Increased risks to lives and livelihoods.

Similarly, higher temperatures and extreme events — such as intense rainfall, stronger cyclones and increased risk of landslides — can cause physical injuries, water contamination , decreased labor productivity and mental stress such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorders. Hot weather and more intense heat waves reduce people’s ability to work and stay healthy; an environment that is too hot and humid makes it impossible for the human body to sweat and can lead to overheating and death.

Changes in the rainy seasons and other, slower-onset climate change risks like salt intrusion from rising sea levels can also negatively impact crop yields and food quality over time. This can lead to greater food insecurity and undernutrition. Bangladesh has the largest delta of any country in the world, and increasing salinity has already negatively affected its crop, fish and livestock production.

Even in places where agriculture yields may be boosted due to climate change, evidence has emerged that such increases can come at the expense of nutrition. These food security threats, in turn, affect people’s every day health, especially when it comes to child growth and development .

Environmental degradation and natural resources instability and competition exacerbated by climate impacts can also contribute to forced migration and social conflict . This can expose people to physical and mental health stressors, exacerbate existing health issues, lead to poorer living conditions and reduce access to affordable medical care.

3. Greater risk of social inequities.

The effects of climate change are especially felt by the most vulnerable , including people living in poverty, those who are marginalized or socially excluded, women, children, the elderly and those who are already ill or living with a disability. Without adequate support and funding, vulnerable groups will continue to suffer the most from the impacts of climate change on health.

The rising frequency, intensity and duration of extreme weather events will disproportionately impact the physical and economic capacities of people and households already struggling with weakened health and chronic disease. Due to their already debilitated or weakened immune systems, people with cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and other pre-existing health conditions are at higher risk of injury or sickness from natural disasters and other climate-related risks.

The elderly and people who perform heavy physical labor, including agricultural laborers, are especially at risk from the effects of increasing heat and heat wave events, which stress the heart (possibly leading to cardiac arrest) and can cause severe dehydration, which damages other vital organs like the kidneys.

When combined with poorer nutrition and water stress, the result is often worse existing health problems, which can further entrench generational poverty and systemic vulnerabilities . This, in turn, contributes to heightened mortality and morbidity at a wider scale, increasing countries’ disease burdens.

What Are the Challenges to Integrating Climate Adaptation into Health Plans?

Several technical and financial challenges remain when it comes to incorporating climate-sensitive risks into health systems. Many countries and groups lack a strong understanding of the links between climate change and health. This is made more complicated when considering that cause-and-effect is difficult, and at times impossible, to prove.

While environmental health and public health officers can see the connections, policymakers may not understand them without proper training. These knowledge gaps can lead to inconsistent policies and a lack of adaptation activities in health budgets.

Many countries also have inadequate finance to implement adaptation and health activities.

As our case study illustrates, in Ghana, for instance, policymakers have limited human resources and skills available to identify and develop appropriate adaptation measures to reduce climate-sensitive health risks. As a result, it is difficult to persuade Parliament to dedicate an adequate budget for such activities. Frequent changes in administration can also make it difficult to ensure consistent allocation of public resources for adaptation in the health sector.

Despite being a priority in national policies and international commitments, technical and financial support requests to the NDC Partnership and multilateral climate funds like the Green Climate Fund often vastly underrepresent health-specific activities.

In a global review of more than 100 countries, the UN found that only one in five countries is spending enough to implement climate-related health commitments. This gap will be further exacerbated by 2030, when the direct damage costs to health are expected to be between $2 billion to $4 billion per year — even without considering indirect effects.

How Can Governments Adapt to Protect Human Health from the Effects of Climate Change?

While it can be difficult to identify, understand and reduce climate-sensitive health risks, a lack of information should not prevent action or delay no-regrets adaptation measures to strengthen health care systems. No-regrets measures include actions that protect communities whether climate impacts materialize as severely as expected or not, such as building robust food and medical supply chains, retrofitting technology and equipment, increasing training of medical staff and establishing protections against interrupted health services.

Governments can establish policy frameworks and collaboration mechanisms to provide needed guidance and support for no-regrets adaptation measures. Champions of climate and health issues inside and outside of the health sector can rally critical supporters and resources to influence policies and drive action.

Fiji, one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world, provides an excellent example of how to advance solutions. The nation developed and implemented its national Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan and integrated it into various policies and plans. The adaptation and health activities in Fiji’s plan are expected to increase the nation’s ability to provide and use reliable information on climate-sensitive health risks through an early warning system; improve capacity within health sector institutions to respond to these risks; and allow the nation to pilot disease prevention measures in higher-risk areas.

Fiji also set up a Climate Change and Health Unit within its Ministry of Health and allocated domestic funding to advance climate-health activities, like early warning systems, and build the capacity of health institutions to respond to climate threats. Health and climate change also remain on the political agenda thanks to the continuous efforts of and leadership from its Permanent Secretaries of the Ministry of Health, who encourage collaboration with other ministries.

Protecting the Health of Current and Future Generations

The links between climate change and health continue to grow in clarity and evidence. Policymakers can seize on the political momentum created by the global pandemic to strengthen their countries’ abilities to respond to a range of shocks and stressors — including the linked challenges of infectious disease and climate change. Strengthening the overall capacities and resources of health systems will increase adaptive capacity to deal with climate impacts, ensuring that current and future generations remain healthy.

Relevant Work

Key investments can build resilience to pandemics and climate change, 6 big findings from the ipcc 2022 report on climate impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, global emissions and local deforestation are combining to create dangerous levels of heat stress in the tropics, how floods in pakistan threaten global security, how you can help.

WRI relies on the generosity of donors like you to turn research into action. You can support our work by making a gift today or exploring other ways to give.

Stay Informed

World Resources Institute 10 G Street NE Suite 800 Washington DC 20002 +1 (202) 729-7600

© 2024 World Resources Institute

Envision a world where everyone can enjoy clean air, walkable cities, vibrant landscapes, nutritious food and affordable energy.

Newsroom Post

Climate change: a threat to human wellbeing and health of the planet. taking action now can secure our future.

BERLIN, Feb 28 – Human-induced climate change is causing dangerous and widespread disruption in nature and affecting the lives of billions of people around the world, despite efforts to reduce the risks. People and ecosystems least able to cope are being hardest hit, said scientists in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, released today.

“This report is a dire warning about the consequences of inaction,” said Hoesung Lee, Chair of the IPCC. “It shows that climate change is a grave and mounting threat to our wellbeing and a healthy planet. Our actions today will shape how people adapt and nature responds to increasing climate risks.”

The world faces unavoidable multiple climate hazards over the next two decades with global warming of 1.5°C (2.7°F). Even temporarily exceeding this warming level will result in additional severe impacts, some of which will be irreversible. Risks for society will increase, including to infrastructure and low-lying coastal settlements.

The Summary for Policymakers of the IPCC Working Group II report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability was approved on Sunday, February 27 2022, by 195 member governments of the IPCC, through a virtual approval session that was held over two weeks starting on February 14.

Urgent action required to deal with increasing risks

Increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding plants’ and animals’ tolerance thresholds, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals. These weather extremes are occurring simultaneously, causing cascading impacts that are increasingly difficult to manage. They have exposed millions of people to acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on Small Islands and in the Arctic.

To avoid mounting loss of life, biodiversity and infrastructure, ambitious, accelerated action is required to adapt to climate change, at the same time as making rapid, deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. So far, progress on adaptation is uneven and there are increasing gaps between action taken and what is needed to deal with the increasing risks, the new report finds. These gaps are largest among lower-income populations.

The Working Group II report is the second instalment of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), which will be completed this year.

“This report recognizes the interdependence of climate, biodiversity and people and integrates natural, social and economic sciences more strongly than earlier IPCC assessments,” said Hoesung Lee. “It emphasizes the urgency of immediate and more ambitious action to address climate risks. Half measures are no longer an option.”

Safeguarding and strengthening nature is key to securing a liveable future

There are options to adapt to a changing climate. This report provides new insights into nature’s potential not only to reduce climate risks but also to improve people’s lives.

“Healthy ecosystems are more resilient to climate change and provide life-critical services such as food and clean water”, said IPCC Working Group II Co-Chair Hans-Otto Pörtner. “By restoring degraded ecosystems and effectively and equitably conserving 30 to 50 per cent of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean habitats, society can benefit from nature’s capacity to absorb and store carbon, and we can accelerate progress towards sustainable development, but adequate finance and political support are essential.”

Scientists point out that climate change interacts with global trends such as unsustainable use of natural resources, growing urbanization, social inequalities, losses and damages from extreme events and a pandemic, jeopardizing future development.

“Our assessment clearly shows that tackling all these different challenges involves everyone – governments, the private sector, civil society – working together to prioritize risk reduction, as well as equity and justice, in decision-making and investment,” said IPCC Working Group II Co-Chair Debra Roberts.

“In this way, different interests, values and world views can be reconciled. By bringing together scientific and technological know-how as well as Indigenous and local knowledge, solutions will be more effective. Failure to achieve climate resilient and sustainable development will result in a sub-optimal future for people and nature.”

Cities: Hotspots of impacts and risks, but also a crucial part of the solution

This report provides a detailed assessment of climate change impacts, risks and adaptation in cities, where more than half the world’s population lives. People’s health, lives and livelihoods, as well as property and critical infrastructure, including energy and transportation systems, are being increasingly adversely affected by hazards from heatwaves, storms, drought and flooding as well as slow-onset changes, including sea level rise.

“Together, growing urbanization and climate change create complex risks, especially for those cities that already experience poorly planned urban growth, high levels of poverty and unemployment, and a lack of basic services,” Debra Roberts said.

“But cities also provide opportunities for climate action – green buildings, reliable supplies of clean water and renewable energy, and sustainable transport systems that connect urban and rural areas can all lead to a more inclusive, fairer society.”

There is increasing evidence of adaptation that has caused unintended consequences, for example destroying nature, putting peoples’ lives at risk or increasing greenhouse gas emissions. This can be avoided by involving everyone in planning, attention to equity and justice, and drawing on Indigenous and local knowledge.

A narrowing window for action

Climate change is a global challenge that requires local solutions and that’s why the Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) provides extensive regional information to enable Climate Resilient Development.

The report clearly states Climate Resilient Development is already challenging at current warming levels. It will become more limited if global warming exceeds 1.5°C (2.7°F). In some regions it will be impossible if global warming exceeds 2°C (3.6°F). This key finding underlines the urgency for climate action, focusing on equity and justice. Adequate funding, technology transfer, political commitment and partnership lead to more effective climate change adaptation and emissions reductions.

“The scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner.

For more information, please contact:

IPCC Press Office, Email: [email protected] IPCC Working Group II: Sina Löschke, Komila Nabiyeva: [email protected]

Notes for Editors

Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The Working Group II report examines the impacts of climate change on nature and people around the globe. It explores future impacts at different levels of warming and the resulting risks and offers options to strengthen nature’s and society’s resilience to ongoing climate change, to fight hunger, poverty, and inequality and keep Earth a place worth living on – for current as well as for future generations.

Working Group II introduces several new components in its latest report: One is a special section on climate change impacts, risks and options to act for cities and settlements by the sea, tropical forests, mountains, biodiversity hotspots, dryland and deserts, the Mediterranean as well as the polar regions. Another is an atlas that will present data and findings on observed and projected climate change impacts and risks from global to regional scales, thus offering even more insights for decision makers.

The Summary for Policymakers of the Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) as well as additional materials and information are available at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

Note : Originally scheduled for release in September 2021, the report was delayed for several months by the COVID-19 pandemic, as work in the scientific community including the IPCC shifted online. This is the second time that the IPCC has conducted a virtual approval session for one of its reports.

AR6 Working Group II in numbers

270 authors from 67 countries

- 47 – coordinating authors

- 184 – lead authors

- 39 – review editors

- 675 – contributing authors

Over 34,000 cited references

A total of 62,418 expert and government review comments

(First Order Draft 16,348; Second Order Draft 40,293; Final Government Distribution: 5,777)

More information about the Sixth Assessment Report can be found here .

Additional media resources

Assets available after the embargo is lifted on Media Essentials website .

Press conference recording, collection of sound bites from WGII authors, link to presentation slides, B-roll of approval session, link to launch Trello board including press release and video trailer in UN languages, a social media pack.

The website includes outreach materials such as videos about the IPCC and video recordings from outreach events conducted as webinars or live-streamed events.

Most videos published by the IPCC can be found on our YouTube channel. Credit for artwork

About the IPCC

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the UN body for assessing the science related to climate change. It was established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988 to provide political leaders with periodic scientific assessments concerning climate change, its implications and risks, as well as to put forward adaptation and mitigation strategies. In the same year the UN General Assembly endorsed the action by the WMO and UNEP in jointly establishing the IPCC. It has 195 member states.

Thousands of people from all over the world contribute to the work of the IPCC. For the assessment reports, IPCC scientists volunteer their time to assess the thousands of scientific papers published each year to provide a comprehensive summary of what is known about the drivers of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and how adaptation and mitigation can reduce those risks.

The IPCC has three working groups: Working Group I , dealing with the physical science basis of climate change; Working Group II , dealing with impacts, adaptation and vulnerability; and Working Group III , dealing with the mitigation of climate change. It also has a Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories that develops methodologies for measuring emissions and removals. As part of the IPCC, a Task Group on Data Support for Climate Change Assessments (TG-Data) provides guidance to the Data Distribution Centre (DDC) on curation, traceability, stability, availability and transparency of data and scenarios related to the reports of the IPCC.

IPCC assessments provide governments, at all levels, with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies. IPCC assessments are a key input into the international negotiations to tackle climate change. IPCC reports are drafted and reviewed in several stages, thus guaranteeing objectivity and transparency. An IPCC assessment report consists of the contributions of the three working groups and a Synthesis Report. The Synthesis Report integrates the findings of the three working group reports and of any special reports prepared in that assessment cycle.

About the Sixth Assessment Cycle

At its 41st Session in February 2015, the IPCC decided to produce a Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). At its 42nd Session in October 2015 it elected a new Bureau that would oversee the work on this report and the Special Reports to be produced in the assessment cycle.

Global Warming of 1.5°C , an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty was launched in October 2018.

Climate Change and Land , an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems was launched in August 2019, and the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate was released in September 2019.

In May 2019 the IPCC released the 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories , an update to the methodology used by governments to estimate their greenhouse gas emissions and removals.

In August 2021 the IPCC released the Working Group I contribution to the AR6, Climate Change 2021, the Physical Science Basis

The Working Group III contribution to the AR6 is scheduled for early April 2022.

The Synthesis Report of the Sixth Assessment Report will be completed in the second half of 2022.

For more information go to www.ipcc.ch

Related Content

Remarks by the ipcc chair during the press conference to present the working group ii contribution to the sixth assessment report.

Monday, 28 February 2022 Distinguished representatives of the media, WMO Secretary-General Petteri, UNEP Executive Director Andersen, We have just heard …

February 2022

Fifty-fifth session of the ipcc (ipcc-55) and twelfth session of working group ii (wgii-12), february 14, 2022, working group report, ar6 climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

Climate Change: Evidence and Causes: Update 2020 (2020)

Chapter: conclusion, c onclusion.

This document explains that there are well-understood physical mechanisms by which changes in the amounts of greenhouse gases cause climate changes. It discusses the evidence that the concentrations of these gases in the atmosphere have increased and are still increasing rapidly, that climate change is occurring, and that most of the recent change is almost certainly due to emissions of greenhouse gases caused by human activities. Further climate change is inevitable; if emissions of greenhouse gases continue unabated, future changes will substantially exceed those that have occurred so far. There remains a range of estimates of the magnitude and regional expression of future change, but increases in the extremes of climate that can adversely affect natural ecosystems and human activities and infrastructure are expected.

Citizens and governments can choose among several options (or a mixture of those options) in response to this information: they can change their pattern of energy production and usage in order to limit emissions of greenhouse gases and hence the magnitude of climate changes; they can wait for changes to occur and accept the losses, damage, and suffering that arise; they can adapt to actual and expected changes as much as possible; or they can seek as yet unproven “geoengineering” solutions to counteract some of the climate changes that would otherwise occur. Each of these options has risks, attractions and costs, and what is actually done may be a mixture of these different options. Different nations and communities will vary in their vulnerability and their capacity to adapt. There is an important debate to be had about choices among these options, to decide what is best for each group or nation, and most importantly for the global population as a whole. The options have to be discussed at a global scale because in many cases those communities that are most vulnerable control few of the emissions, either past or future. Our description of the science of climate change, with both its facts and its uncertainties, is offered as a basis to inform that policy debate.

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following individuals served as the primary writing team for the 2014 and 2020 editions of this document:

- Eric Wolff FRS, (UK lead), University of Cambridge

- Inez Fung (NAS, US lead), University of California, Berkeley

- Brian Hoskins FRS, Grantham Institute for Climate Change

- John F.B. Mitchell FRS, UK Met Office

- Tim Palmer FRS, University of Oxford

- Benjamin Santer (NAS), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- John Shepherd FRS, University of Southampton

- Keith Shine FRS, University of Reading.

- Susan Solomon (NAS), Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Kevin Trenberth, National Center for Atmospheric Research

- John Walsh, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

- Don Wuebbles, University of Illinois

Staff support for the 2020 revision was provided by Richard Walker, Amanda Purcell, Nancy Huddleston, and Michael Hudson. We offer special thanks to Rebecca Lindsey and NOAA Climate.gov for providing data and figure updates.

The following individuals served as reviewers of the 2014 document in accordance with procedures approved by the Royal Society and the National Academy of Sciences:

- Richard Alley (NAS), Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University

- Alec Broers FRS, Former President of the Royal Academy of Engineering

- Harry Elderfield FRS, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge

- Joanna Haigh FRS, Professor of Atmospheric Physics, Imperial College London

- Isaac Held (NAS), NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

- John Kutzbach (NAS), Center for Climatic Research, University of Wisconsin

- Jerry Meehl, Senior Scientist, National Center for Atmospheric Research

- John Pendry FRS, Imperial College London

- John Pyle FRS, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge

- Gavin Schmidt, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- Emily Shuckburgh, British Antarctic Survey

- Gabrielle Walker, Journalist

- Andrew Watson FRS, University of East Anglia

The Support for the 2014 Edition was provided by NAS Endowment Funds. We offer sincere thanks to the Ralph J. and Carol M. Cicerone Endowment for NAS Missions for supporting the production of this 2020 Edition.

F OR FURTHER READING

For more detailed discussion of the topics addressed in this document (including references to the underlying original research), see:

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2019: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [ https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc ]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), 2019: Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25259 ]

- Royal Society, 2018: Greenhouse gas removal [ https://raeng.org.uk/greenhousegasremoval ]

- U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), 2018: Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume II: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States [ https://nca2018.globalchange.gov ]

- IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C [ https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15 ]

- USGCRP, 2017: Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume I: Climate Science Special Reports [ https://science2017.globalchange.gov ]

- NASEM, 2016: Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21852 ]

- IPCC, 2013: Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) Working Group 1. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis [ https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1 ]

- NRC, 2013: Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18373 ]

- NRC, 2011: Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts Over Decades to Millennia [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12877 ]

- Royal Society 2010: Climate Change: A Summary of the Science [ https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2010/climate-change-summary-science ]

- NRC, 2010: America’s Climate Choices: Advancing the Science of Climate Change [ https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12782 ]

Much of the original data underlying the scientific findings discussed here are available at:

- https://data.ucar.edu/

- https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu

- https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu

- https://ess-dive.lbl.gov/

- https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/

- https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/

- http://scrippsco2.ucsd.edu

- http://hahana.soest.hawaii.edu/hot/

| was established to advise the United States on scientific and technical issues when President Lincoln signed a Congressional charter in 1863. The National Research Council, the operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering, has issued numerous reports on the causes of and potential responses to climate change. Climate change resources from the National Research Council are available at . | |

| is a self-governing Fellowship of many of the world’s most distinguished scientists. Its members are drawn from all areas of science, engineering, and medicine. It is the national academy of science in the UK. The Society’s fundamental purpose, reflected in its founding Charters of the 1660s, is to recognise, promote, and support excellence in science, and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. More information on the Society’s climate change work is available at |

Climate change is one of the defining issues of our time. It is now more certain than ever, based on many lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth's climate. The Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences, with their similar missions to promote the use of science to benefit society and to inform critical policy debates, produced the original Climate Change: Evidence and Causes in 2014. It was written and reviewed by a UK-US team of leading climate scientists. This new edition, prepared by the same author team, has been updated with the most recent climate data and scientific analyses, all of which reinforce our understanding of human-caused climate change.

Scientific information is a vital component for society to make informed decisions about how to reduce the magnitude of climate change and how to adapt to its impacts. This booklet serves as a key reference document for decision makers, policy makers, educators, and others seeking authoritative answers about the current state of climate-change science.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 01 June 2010

Reframing climate change as a public health issue: an exploratory study of public reactions

- Edward W Maibach 1 ,

- Matthew Nisbet 1 , 2 ,

- Paula Baldwin 1 ,

- Karen Akerlof 1 &

- Guoqing Diao 3

BMC Public Health volume 10 , Article number: 299 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

55k Accesses

264 Citations

213 Altmetric

Metrics details

Climate change is taking a toll on human health, and some leaders in the public health community have urged their colleagues to give voice to its health implications. Previous research has shown that Americans are only dimly aware of the health implications of climate change, yet the literature on issue framing suggests that providing a novel frame - such as human health - may be potentially useful in enhancing public engagement. We conducted an exploratory study in the United States of people's reactions to a public health-framed short essay on climate change.

U.S. adult respondents (n = 70), stratified by six previously identified audience segments, read the essay and were asked to highlight in green or pink any portions of the essay they found "especially clear and helpful" or alternatively "especially confusing or unhelpful." Two dependent measures were created: a composite sentence-specific score based on reactions to all 18 sentences in the essay; and respondents' general reactions to the essay that were coded for valence (positive, neutral, or negative). We tested the hypothesis that five of the six audience segments would respond positively to the essay on both dependent measures.

There was clear evidence that two of the five segments responded positively to the public health essay, and mixed evidence that two other responded positively. There was limited evidence that the fifth segment responded positively. Post-hoc analysis showed that five of the six segments responded more positively to information about the health benefits associated with mitigation-related policy actions than to information about the health risks of climate change.

Conclusions

Presentations about climate change that encourage people to consider its human health relevance appear likely to provide many Americans with a useful and engaging new frame of reference. Information about the potential health benefits of specific mitigation-related policy actions appears to be particularly compelling. We believe that the public health community has an important perspective to share about climate change, a perspective that makes the problem more personally relevant, significant, and understandable to members of the public.

Peer Review reports

Climate change is already taking a toll on human health in the United States [ 1 ] and other nations worldwide [ 2 ]. Unless greenhouse gas emissions worldwide are sharply curtailed - and significant actions taken to help communities adapt to changes in their climate that are unavoidable - the human toll of climate change is likely to become dramatically worse over the next several decades and beyond [ 3 ]. Globally, the human health impacts of climate change will continue to differentially affect the world's poorest nations, where populations endemically suffer myriad health burdens associated with extreme poverty that are being exacerbated by the changing climate. As stated in a recent British Medical Journal editorial, failure of the world's nations to successfully curtail emissions will likely lead to a "global health catastrophe" [ 4 ]. In developed countries such as the United States, the segments of the population most at risk are the poor, the very young, the elderly, those already in poor health, the disabled, individuals living alone, those with inadequate housing or basic services, and/or individuals who lack access to affordable health care or who live in areas with weak public health systems. These population segments disproportionately include racial, ethnic, and indigenous minorities [ 5 ].

While legislation to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has stalled in Congress, in December 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) moved toward regulating carbon dioxide and five other of the gases under the Clean Air Act, citing its authority to protect public health and welfare from the impacts of global warming [ 5 ]. The agency found that global warming poses public health risks - including increased morbidity and mortality - due to declining air quality, rising temperatures, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and higher incidences of food- and water-borne pathogens and allergens.

This finding comes as a relatively small group of public health professionals are working rapidly to better comprehend and quantify the nature and magnitude of these threats to human health and wellbeing [ 6 ]. This new but rapidly advancing public health focus has received minimal news media attention, even at internationally leading news organizations such as the New York Times [unpublished data]. It is not surprising therefore that the public also has yet to fully comprehend the public health implications of climate change. Recent surveys of Americans [ 7 ], Canadians [ 8 ], and Maltese [ 9 ] demonstrate that the human health consequences of climate change are seriously underestimated and/or poorly understood, if grasped at all. About half of American survey respondents, for example, selected "don't know" (rather than "none," "hundreds," "thousands," or "millions") when asked the estimated number of current and future (i.e. 50 years hence) injuries and illnesses, and death due to climate change. An earlier survey of Americans [ 10 ] demonstrated that most people see climate change as a geographically and temporally distant threat to the non-human environment. Notably, not a single survey respondent freely associated climate change as representing a threat to people. Similarly, few Canadians, without prompting, can name any specific human health threat linked to climate change impacts in their country [ 8 ].

Cognitive research over the past several decades has shown that how people "frame" an issue - i.e., how they mentally organize and discuss with others the issue's central ideas - greatly influences how they understand the nature of the problem, who or what they see as being responsible for the problem, and what they feel should be done to address the problem [ 11 , 12 ]. The polling data cited above [ 7 – 9 ] suggests that the dominant mental frame used by most members of the public to organize their conceptions about climate change is that of "climate change as an environmental problem." However, when climate change is framed as an environmental problem, this interpretation likely distances many people from the issue and contributes to a lack of serious and sustained public engagement necessary to develop solutions. This focus is also susceptible to a dominant counter frame that the best solution is to continue to grow the economy - paying for adaptive measures in the future when, theoretically, society will be wealthier and better able to afford them - rather than focus on the root causes of the environmental problem [ 13 ]. This economic frame likely leaves the public ambivalent about policy action and works to the advantage of industries that are reluctant to reduce their carbon intensity. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of a countervailing populist movement on climate change that has made policy solutions so difficult to enact [ 13 , 14 ].

Significant efforts have been made over the past several years by public health organizations to raise awareness of the public health implications of climate change and prepare the public health workforce to respond, although as noted above, it is not clear the extent to which public health professionals, journalists, or most importantly, the public and policy makers have taken notice. In the United States, National Public Health Week 2008 was themed "Climate Change: Our Health in the Balance," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention created a Climate Change and Public Health program, and several professional associations assessed the public health system's readiness to respond to the emerging threat [ 15 – 17 ]. Globally, World Health Day 2008 was themed "Protecting Health from Climate Change," and the World Health Organization has developed a climate change and health work plan, the first objective of which is "raising awareness of the effects of climate change on health, in order to prompt action for public health measures" [ 18 ]. Several prominent medical journals have released special issues on climate change and health [ 19 – 21 ], and these and other medical journals [ 4 ] have issued strongly worded editorials urging health professionals to give voice to the health implications of climate change.

An important assumption in these calls to action is that there may be considerable value in introducing a public health frame into the ongoing public - and policy - dialogue about climate change. While there is indeed solid theoretical basis for this assumption, to the best of our knowledge there is not yet empirical evidence to support the validity of the assumption [ 22 ].

The purpose of this study therefore was to explore how American adults respond to an essay about climate change framed as a public health issue. Our hypothesis was that a public health-framed explanation of climate change would be perceived as useful and personally relevant by readers, with the exception of members of one small segment of Americans who dismiss the notion that human-induced climate change is happening. We used two dependent measures in this hypothesis: a composite score based on respondent reactions to each sentence in the essay, and the overall valence of respondents' general comments made after reading the essay.

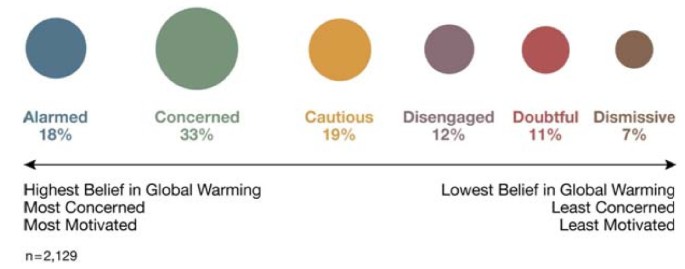

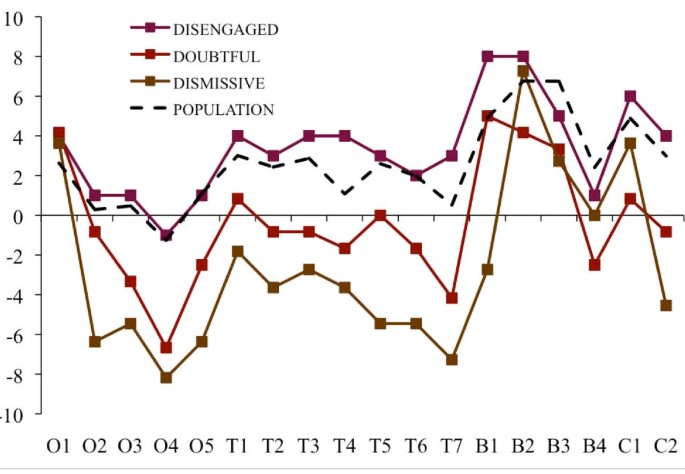

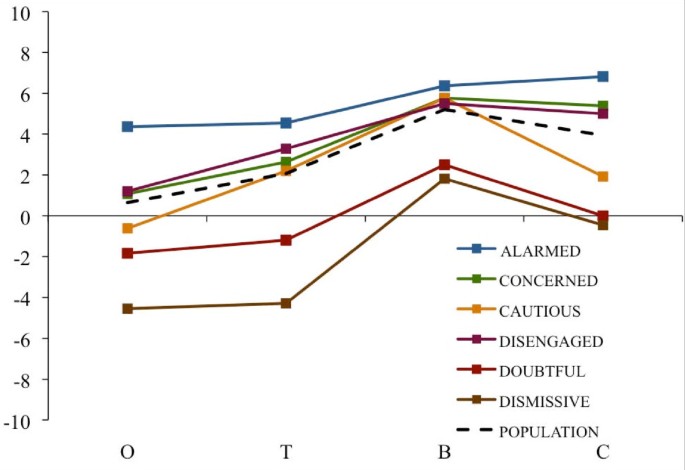

Our study builds on previous research that identified six distinct segments of Americans, termed Global Warming's Six Americas [ 7 ]. These six segments of Americans - the Alarmed (18% of the adult population), the Concerned (33%), the Cautious (19%), the Disengaged (12%), the Doubtful (11%), and the Dismissive (7%) - fall along a continuum from those who are engaged on the issue and looking for ways to take appropriate actions (the Alarmed) to those who actively deny its reality and are looking for ways to oppose societal action (the Dismissive; see Figure 1 ). The four segments in the middle of the continuum are likely to benefit most from a reframing of climate change as a human health problem because, to a greater or lesser degree, they are not yet sure that they fully understand the issue and are still, if motivated to do so, relatively open to learning about new perspectives.

Global Warming's Six Americas . A nationally representative sample of American adults classified into six unique audience segments based on their climate change-related beliefs, behaviors and policy preferences.

Between May and August 2009, 74 adults were recruited to participate in semi-structured in-depth elicitation interviews that lasted an average of 43 minutes (ranging from 16 to 124 minutes) and included the presentation of a public health framed essay on climate change. The recruitment process was designed to yield completed interviews with a demographically and geographically diverse group of at least 10 people from each of the previously identified "Six Americas" [ 7 ]. Four respondents were dropped from this study due to incomplete data, leaving a sample size of 70. Audience segment status (i.e., which one of the "Six Americas" a person belonged) was assessed with a previously developed 15-item screening questionnaire that identifies segment status with 80% accuracy [unpublished data].

To achieve demographic diversity in the sample, we recruited an approximately balanced number of men and women, and an approximately balanced number of younger (18 to 30), middle-aged (31 to 50), and older (51 and older) adults (see Table 1 ). We did not set recruitment quotas for racial/ethnic groups, but did make an effort to recruit a mix of people from various racial/ethnic backgrounds.

To achieve geographic diversity, we recruited participants in one of two ways. The majority of participants (n = 56) were recruited - and then interviewed - face-to-face in one of two locations: out-of-town visitors were interviewed at a central location on the National Mall in Washington, DC (a national park situated between the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian Museum buildings, and the Lincoln Memorial); and shoppers were interviewed at an "outlet" mall (i.e., discount branded merchandise shopping mall) adjacent to an interstate freeway in Hagerstown, MD. The outlet mall is more than an hour driving distance outside of Washington, DC and attracts shoppers from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, as well as visitors from further away who are driving the interstate freeway. The remaining study participants were recruited via email from among participants to a nationally representative survey that we conducted in Fall 2008 [ 7 ]. They were interviewed subsequently by telephone, after being mailed a copy of the test "public health essay" - described below - in a sealed envelope marked "do not open until asked to do so by the interviewer." As an incentive to participate, all respondents were given a $50 gift card upon completion of their interview. George Mason University Human Subjects Review Board provided approval for the study protocol (reference #6161); all potential respondents received written consent information prior to participation.

The 70 study participants resided in 29 states. Using U.S. Census Bureau classifications, 14% (n = 10) were from the Northeast region, 21% (n = 15) were from the Midwest, 40% (n = 28) from the South, and 23% (n = 16) were from the West; state and region were unknown for one participant. In 2006, the geographic distribution of the overall U.S. population was 18%, 22%, 36% and 23% in the Northeast, Midwest, South and West, respectively [ 23 ].

Data Collection and Coding

The majority of the interview was devoted to open-ended questions intended to establish the respondent's emotions, attitudes, beliefs, knowledge and behavior relative to global warming's causes and consequences. For example, respective open-ended questions asked alternatively if, how, and for whom global warming was a problem; how global warming is caused; if and how global warming can be stopped or limited; and what, if anything, an individual could do to help limit global warming. Toward the end of the interview, respondents were asked to read "a brief essay about global warming" (see Appendix 1), which was designed to frame climate change as a human health issue. Respondents were also given a green and a pink highlighting pen and asked to "use the green highlighter pen to mark any portions of the essay that you feel are especially clear or helpful, and use the pink highlighter pen to mark any portions of the essay that are particularly confusing or unhelpful."