Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 12 May 2021

Good presentation skills benefit careers — and science

- David Rubenson 0

David Rubenson is the director of the scientific-communications firm No Bad Slides ( nobadslides.com ) in Los Angeles, California.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A better presentation culture can save the audience and the larger scientific world valuable time and effort. Credit: Shutterstock

In my experience as a presentation coach for biomedical researchers, I have heard many complaints about talks they attend: too much detail, too many opaque visuals, too many slides, too rushed for questions and so on. Given the time scientists spend attending presentations, both in the pandemic’s virtual world and in the ‘face-to-face’ one, addressing these complaints would seem to be an important challenge.

I’m dispirited that being trained in presentation skills, or at least taking more time to prepare presentations, is often not a high priority for researchers or academic departments. Many scientists feel that time spent improving presentations detracts from research or clocking up the numbers that directly affect career advancement — such as articles published and the amount of grant funding secured. Add in the pressing, and sometimes overwhelming, bureaucratic burdens associated with working at a major biomedical research institute, and scientists can simply be too busy to think about changing the status quo.

Improving presentations can indeed be time-consuming. But there are compelling reasons for researchers to put this near the top of their to-do list.

You’re probably not as good a presenter as you think you are

Many scientists see problems in colleagues’ presentations, but not their own. Having given many lousy presentations, I know that it is all too easy to receive (and accept) plaudits; audiences want to be polite. However, this makes it difficult to get an accurate assessment of how well you have communicated your message.

Why your scientific presentation should not be adapted from a journal article

With few exceptions, biomedical research presentations are less effective than the speaker would believe. And with few exceptions, researchers have little appreciation of what makes for a good presentation. Formal training in presentation techniques (see ‘What do scientists need to learn?’) would help to alleviate these problems.

Improving a presentation can help you think about your own research

A well-designed presentation is not a ‘data dump’ or an exercise in advanced PowerPoint techniques. It is a coherent argument that can be understood by scientists in related fields. Designing a good presentation forces a researcher to step back from laboratory procedures and organize data into themes; it’s an effective way to consider your research in its entirety.

You might get insights from the audience

Overly detailed presentations typically fill a speaker’s time slot, leaving little opportunity for the audience to ask questions. A comprehensible and focused presentation should elicit probing questions and allow audience members to suggest how their tools and methods might apply to the speaker’s research question.

Many have suggested that multidisciplinary collaborations, such as with engineers and physical scientists, are essential for solving complex problems in biomedicine. Such innovative partnerships will emerge only if research is communicated clearly to a broad range of potential collaborators.

It might improve your grant writing

Many grant applications suffer from the same problem as scientific presentations — too much detail and a lack of clearly articulated themes. A well-designed presentation can be a great way to structure a compelling grant application: by working on one, you’re often able to improve the other.

It might help you speak to important, ‘less-expert’ audiences

As their career advances, it is not uncommon for scientists to increasingly have to address audiences outside their speciality. These might include department heads, deans, philanthropic foundations, individual donors, patient groups and the media. Communicating effectively with scientific colleagues is a prerequisite for reaching these audiences.

Collection: Conferences

Better presentations mean better science

An individual might not want to spend 5 hours improving their hour-long presentation, but 50 audience members might collectively waste 50 hours listening to that individual’s mediocre effort. This disparity shows that individual incentives aren’t always aligned with society’s scientific goals. An effective presentation can enhance the research and critical-thinking skills of the audience, in addition to what it does for the speaker.

What do scientists need to learn?

Formal training in scientific presentation techniques should differ significantly from programmes that stress the nuances of public speaking.

The first priority should be to master basic presentation concepts, including:

• How to build a concise scientific narrative.

• Understanding the limitations of slides and presentations.

• Understanding the audience’s time and attention-span limitations .

• Building a complementary, rather than repetitive, relationship between what the speaker says and what their slides show.

The training should then move to proper slide design, including:

• The need for each slide to have an overarching message.

• Using slide titles to help convey that message.

• Labelling graphs legibly.

• Deleting superfluous data and other information.

• Reducing those 100-word text slides to 40 words (or even less) without losing content.

• Using colour to highlight categories of information, rather than for decoration.

• Avoiding formats that have no visual message, such as data tables.

A well-crafted presentation with clearly drawn slides can turn even timid public speakers into effective science communicators.

Scientific leaders have a responsibility to provide formal training and to change incentives so that researchers spend more time improving presentations.

A dynamic presentation culture, in which every presentation is understood, fairly critiqued and useful for its audience, can only be good for science.

Nature 594 , S51-S52 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01281-8

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Related Articles

- Conferences and meetings

- Research management

Tales of a migratory marine biologist

Career Feature 28 AUG 24

Nail your tech-industry interviews with these six techniques

Career Column 28 AUG 24

How to harness AI’s potential in research — responsibly and ethically

Career Feature 23 AUG 24

Hybrid conferences should be the norm — optimize them so everyone benefits

Editorial 06 AUG 24

How to spot a predatory conference, and what science needs to do about them: a guide

Career Feature 30 JUL 24

Predatory conferences are on the rise. Here are five ways to tackle them

Editorial 30 JUL 24

Binning out-of-date chemicals? Somebody think about the carbon!

Correspondence 27 AUG 24

No more hunting for replication studies: crowdsourced database makes them easy to find

Nature Index 27 AUG 24

Partners in drug discovery: how to collaborate with non-governmental organizations

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions in the fields of energy and resources.

Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

School of Sustainable Energy and Resources at Nanjing University

ATLAS - Joint PhD Program from BioNTech and TRON with a focus on translational medicine

5 PhD positions for ATLAS, the joint PhD Program from BioNTech and TRON with a focus on translational medicine.

Mainz, Rheinland-Pfalz (DE)

Translational Oncology (TRON) Mainz

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) Researcher/Associate Researcher

Xiaoliang Sunney XIE’s Group is recruiting researchers specializing in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Beijing, China

Changping Laboratory

Supervisory Bioinformatics Specialist CTG Program Head

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) is a global leader in biomedical informatics and computational health data science and the world’s largest b...

Bethesda, Maryland (US)

National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information

Post Doctoral Research Scientist

Post-Doctoral Research Scientist Position in Human Transplant Immunology at the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology in New York, NY

New York City, New York (US)

Columbia Center for Translational Immunoogy

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Patterns of PowerPoint Use in Higher Education: a Comparison between the Natural, Medical, and Social Sciences

- Published: 28 November 2019

- Volume 45 , pages 65–80, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- David Chávez Herting 1 ,

- Ramón Cladellas Pros 1 &

- Antoni Castelló Tarrida 1

1455 Accesses

7 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

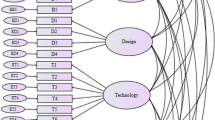

PowerPoint is one of the most widely used technological tools in educational contexts, but little is known about the differences in usage patterns by faculty members from various disciplines. For the study we report in this article we used a survey specially designed to explore this question, and it was completed by 106 faculty members from different disciplines. The results suggest the existence of different patterns in the use of PowerPoint. In addition, the importance of habit in its use is highlighted. Those professors who reported greater dependence on PowerPoint tended to use PowerPoint primarily as study material for their students. We discuss the practical relevance of these results.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

How do academic disciplines use powerpoint.

Comprehensive evaluation of the use of technology in education – validation with a cohort of global open online learners

“It’s Not a Plug-In Product”

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Baker, J. P., Goodboy, A. K., Bowman, N. D., & Wright, A. A. (2018). Does teaching with PowerPoint increase students’ learning? A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 126 , 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.003

Article Google Scholar

Bartsch, R. A., & Cobern, K. M. (2003). Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Computers & Education, 41 , 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(03)00027-7

Blokzijl, W., & Andeweg, B. (2005). The effects of text slide format and presentational quality on learning in college lectures. Proceedings of the International Professional Communication Conference, 2005 , 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1109/IPCC.2005.1494188

Cladellas, R., & Castelló, A. (2017). Percepción del aprendizaje, procedimientos de evaluación y uso de la tecnología PowerPoint en la formación universitaria de medicina [Perception of learning, evaluation procedures, and use of PowerPoint in university medical training]. Intangible Capital, 13 , 302–318. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.814

Cosgun Ögeyik, M. (2017). The effectiveness of PowerPoint presentation and conventional lecture on pedagogical content knowledge attainment. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54 , 503–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1250663

Craig, R. J., & Amernic, J. H. (2006). PowerPoint presentation technology and the dynamics of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 31 , 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-006-9017-5

Cullen, A. E., Williams, J. L., & McCarley, N. G. (2018). Conscientiousness and learning via feedback to identify relevant information on PowerPoint slides. North American Journal of Psychology, 20 , 425–444.

Google Scholar

Garrett, N. (2016). How do academic disciplines use PowerPoint? Innovative Higher Education, 41 , 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-016-9381-8

Grech, V. (2018). The application of the Mayer multimedia learning theory to medical PowerPoint slide show presentations. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 41 , 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453054.2017.1408400

Hallewell, M. J., & Lackovic, N. (2017). Do pictures “tell” a thousand words in lectures? How lecturers vocalise photographs in their presentations. Higher Education Research & Development, 36 , 1166–1180. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1303454

Hertz, B., van Woerkum, C., & Kerkhof, P. (2015). Why do scholars use PowerPoint the way they do? Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 78 , 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490615589171

Huxham, M. (2010). The medium makes the message: Effects of cues on students’ lecture notes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11 , 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787410379681

James, K. E., Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2006). Powerful or pointless? Faculty versus student perceptions of PowerPoint use in business education. Business Communication Quarterly, 69 , 374–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569906294634

Johnson, D. A., & Christensen, J. (2011). A comparison of simplified-visually rich and traditional presentation styles. Teaching of Psychology, 38 , 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311421333

Kahraman, S., Çevik, C., & Kodan, H. (2011). Investigation of university students’ attitude toward the use of PowerPoint according to some variables. Procedia Computer Science, 3 , 1341–1347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2011.01.013

Kim, H. (2018). Impact of slide-based lectures on undergraduate students’ learning: Mixed effects of accessibility to slides, differences in note-taking, and memory term. Computers & Education, 123 , 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.004

Ledbetter, A. M., & Finn, A. N. (2018). Perceived teacher credibility and students’ affect as a function of instructors’ use of PowerPoint and email. Communication Education, 67 , 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2017.1385821

Levasseur, D. G., & Sawyer, J. K. (2006). Pedagogy meets PowerPoint: A research review of the effects of computer-generated slides in the classroom. Review of Communication, 6 , 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358590600763383

MacKiewicz, J. (2008). Comparing Powerpoint experts’ and university students’ opinions about PowerPoint presentations. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 38 , 149–165. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.38.2.d

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38 , 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_6

Moulton, S. T., Türkay, S., & Kosslyn, S. M. (2017). Does a presentation’s medium affect its message? PowerPoint, Prezi, and oral presentations. PLoS One, 12 (7), e0178774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178774

Otter, R., Gardner, G., & Smith-Peavler, E. (2019). PowerPoint use in the undergraduate biology classroom: Perceptions and impacts on student learning. Journal of College Science Teaching, 48 (3), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/jcst19_048_03_74

Paivio, A. (1990). Mental representations: A dual coding approach . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Pate, A., & Posey, S. (2016). Effects of applying multimedia design principles in PowerPoint lecture redesign. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8 , 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2015.12.014

Roberts, D. (2018a). The engagement agenda, multimedia learning and the use of images in higher education lecturing: Or, how to end death by PowerPoint. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42 , 969–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1332356

Roberts, D. (2018b). “The message is the medium”: Evaluating the use of visual images to provoke engagement and active learning in politics and international relations lectures. Politics, 38 , 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395717717229

Sharp, J. G., Hemmings, B., Kay, R., Murphy, B., & Elliott, S. (2017). Academic boredom among students in higher education: A mixed-methods exploration of characteristics, contributors and consequences. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41 , 657–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1159292

Shigli, K., Agrawal, N., Nair, C., Sajjan, S., Kakodkar, P., & Hebbal, M. (2016). Use of PowerPoint presentation as a teaching tool for undergraduate students in the subject of gerodontology. The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society, 16 , 187–192. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4052.167940

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36 , 157–178.

Williams, J. L., McCarley, N. G., Sharpe, J. L., & Johnson, C. E. (2017). The ability to discern relevant from irrelevant information on PowerPoint slides: A key ingredient to the efficacy of performance feedback. North American Journal of Psychology, 19 , 219–236.

Wisniewski, C. S. (2018). Development and impact of a simplified approach to didactic PowerPoint presentations performed in a drug information course. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10 , 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2017.11.004

Worthington, D. L., & Levasseur, D. G. (2015). To provide or not to provide course PowerPoint slides? The impact of instructor-provided slides upon student attendance and performance. Computers & Education, 85 , 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.002

Yilmazel-Sahin, Y. (2009). A comparison of graduate and undergraduate teacher education students’ perceptions of their instructors’ use of Microsoft PowerPoint. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 18 , 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759390903335866

Zdaniuk, A., Gruman, J. A., & Cassidy, S. A. (2017). PowerPoint slide provision and student performance: The moderating roles of self-efficacy and gender. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43 , 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1367369

Download references

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the CONICYT PFCHA/DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE/2015 – 72160199.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

David Chávez Herting, Ramón Cladellas Pros & Antoni Castelló Tarrida

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Chávez Herting .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chávez Herting, D., Cladellas Pros, R. & Castelló Tarrida, A. Patterns of PowerPoint Use in Higher Education: a Comparison between the Natural, Medical, and Social Sciences. Innov High Educ 45 , 65–80 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-09488-4

Download citation

Published : 28 November 2019

Issue Date : February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-09488-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Higher education

- Educational technology

- Slide presentations

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Center for Teaching

Making better powerpoint presentations.

Print Version

Baddeley and Hitch’s model of working memory.

Research about student preferences for powerpoint, resources for making better powerpoint presentations, bibliography.

We have all experienced the pain of a bad PowerPoint presentation. And even though we promise ourselves never to make the same mistakes, we can still fall prey to common design pitfalls. The good news is that your PowerPoint presentation doesn’t have to be ordinary. By keeping in mind a few guidelines, your classroom presentations can stand above the crowd!

“It is easy to dismiss design – to relegate it to mere ornament, the prettifying of places and objects to disguise their banality. But that is a serious misunderstanding of what design is and why it matters.” Daniel Pink

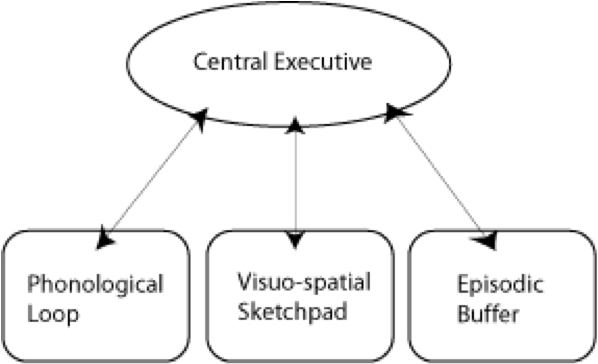

One framework that can be useful when making design decisions about your PowerPoint slide design is Baddeley and Hitch’s model of working memory .

As illustrated in the diagram above, the Central Executive coordinates the work of three systems by organizing the information we hear, see, and store into working memory.

The Phonological Loop deals with any auditory information. Students in a classroom are potentially listening to a variety of things: the instructor, questions from their peers, sound effects or audio from the PowerPoint presentation, and their own “inner voice.”

The Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad deals with information we see. This involves such aspects as form, color, size, space between objects, and their movement. For students this would include: the size and color of fonts, the relationship between images and text on the screen, the motion path of text animation and slide transitions, as well as any hand gestures, facial expressions, or classroom demonstrations made by the instructor.

The Episodic Buffer integrates the information across these sensory domains and communicates with long-term memory. All of these elements are being deposited into a holding tank called the “episodic buffer.” This buffer has a limited capacity and can become “overloaded” thereby, setting limits on how much information students can take in at once.

Laura Edelman and Kathleen Harring from Muhlenberg College , Allentown, Pennsylvania have developed an approach to PowerPoint design using Baddeley and Hitch’s model. During the course of their work, they conducted a survey of students at the college asking what they liked and didn’t like about their professor’s PowerPoint presentations. They discovered the following:

Characteristics students don’t like about professors’ PowerPoint slides

- Too many words on a slide

- Movement (slide transitions or word animations)

- Templates with too many colors

Characteristics students like like about professors’ PowerPoint slides

- Graphs increase understanding of content

- Bulleted lists help them organize ideas

- PowerPoint can help to structure lectures

- Verbal explanations of pictures/graphs help more than written clarifications

According to Edelman and Harring, some conclusions from the research at Muhlenberg are that students learn more when:

- material is presented in short phrases rather than full paragraphs.

- the professor talks about the information on the slide rather than having students read it on their own.

- relevant pictures are used. Irrelevant pictures decrease learning compared to PowerPoint slides with no picture

- they take notes (if the professor is not talking). But if the professor is lecturing, note-taking and listening decreased learning.

- they are given the PowerPoint slides before the class.

Advice from Edelman and Harring on leveraging the working memory with PowerPoint:

- Leverage the working memory by dividing the information between the visual and auditory modality. Doing this reduces the likelihood of one system becoming overloaded. For instance, spoken words with pictures are better than pictures with text, as integrating an image and narration takes less cognitive effort than integrating an image and text.

- Minimize the opportunity for distraction by removing any irrelevant material such as music, sound effects, animations, and background images.

- Use simple cues to direct learners to important points or content. Using text size, bolding, italics, or placing content in a highlighted or shaded text box is all that is required to convey the significance of key ideas in your presentation.

- Don’t put every word you intend to speak on your PowerPoint slide. Instead, keep information displayed in short chunks that are easily read and comprehended.

- One of the mostly widely accessed websites about PowerPoint design is Garr Reynolds’ blog, Presentation Zen . In his blog entry: “ What is Good PowerPoint Design? ” Reynolds explains how to keep the slide design simple, yet not simplistic, and includes a few slide examples that he has ‘made-over’ to demonstrate how to improve its readability and effectiveness. He also includes sample slides from his own presentation about PowerPoint slide design.

- Another presentation guru, David Paradi, author of “ The Visual Slide Revolution: Transforming Overloaded Text Slides into Persuasive Presentations ” maintains a video podcast series called “ Think Outside the Slide ” where he also demonstrates PowerPoint slide makeovers. Examples on this site are typically from the corporate perspective, but the process by which content decisions are made is still relevant for higher education. Paradi has also developed a five step method, called KWICK , that can be used as a simple guide when designing PowerPoint presentations.

- In the video clip below, Comedian Don McMillan talks about some of the common misuses of PowerPoint in his routine called “Life After Death by PowerPoint.”

- This article from The Chronicle of Higher Education highlights a blog moderated by Microsoft’s Doug Thomas that compiles practical PowerPoint advice gathered from presentation masters like Seth Godin , Guy Kawasaki , and Garr Reynolds .

Presenting to Win: The Art of Telling Your Story , by Jerry Weissman, Prentice Hall, 2006

Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery , by Garr Reynolds, New Riders Press, 2008

Solving the PowerPoint Predicament: using digital media for effective communication , by Tom Bunzel , Que, 2006

The Cognitive Style of Power Point , by Edward R. Tufte, Graphics Pr, 2003

The Visual Slide Revolution: Transforming Overloaded Text Slides into Persuasive Presentations , by Dave Paradi, Communications Skills Press, 2000

Why Most PowerPoint Presentations Suck: And How You Can Make Them Better , by Rick Altman, Harvest Books, 2007

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- DOI: 10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2014.03.592

- Corpus ID: 144485052

The Impact of Using PowerPoint Presentations on Students’ Learning and Motivation in Secondary Schools

- Fateme Samiei Lari

- Published 6 May 2014

- Education, Computer Science

- Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Tables from this paper

66 Citations

Attitudes of efl learners and instructors towards the application of power point presentation in iranian classroom context, enhancing learners’ awareness of presentation literacy to stimulate interactive and creative learning in tertiary education, using ppt as an effective cutting edge tool for innovative teaching-learning, the effect of using powerpoint media on students’ english learning motivation to the eleventh grade students of smk muhamadyah 1 samarinda in 2018/2019 academic year, does teaching with powerpoint increase students' learning a meta-analysis, the effect of using powerpoint presentations in academic achievement of social and national studies in the fifth grade students at-risk for learning disabilities, effects of using technology to engage students in learning english at a secondary school, guidelines for creating video podcasts in mathematics higher education, statistical analysis of the effect of lesson and learning styles on the learning and retention of information of secondary school chemistry students, assessment of the efficacies of inverted classroom approach and powerpoint presentation on students’ achievement and self-efficacy in biology, 11 references, student perceptions on language learning in a technological environment: implications for the new millennium.

- Highly Influential

EFFECT OF TECHNOLOGY ON MOTIVATION IN EFL CLASSROOMS

The use of power point presentations at in the department of foreign language education at middle east technical university, using multimodal presentation software and peer group discussion in learning english as a second language, teaching english as a global language in smart classrooms with powerpoint presentation., can powerpoint presentations effectively replace textbooks and blackboards for teaching grammar do students find them an effective learning tool, the value of technology in the efl and esl classroom: using the smartpen to enhance the productivity and effectiveness of esl instruction, social studies teachers’ perspectives of technology integration, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

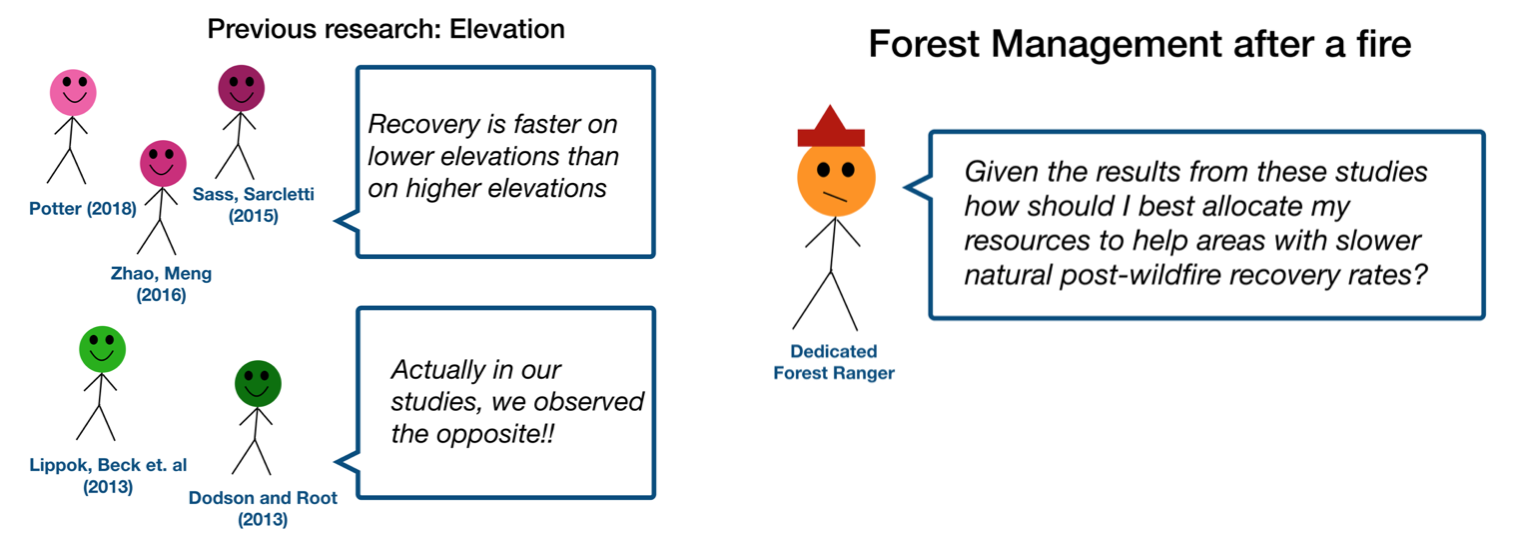

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

6 Tips For Giving a Fabulous Academic Presentation

6-tips-for-giving-a-fabulous-academic-presentation.

Tanya Golash-Boza, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of California

January 11, 2022

One of the easiest ways to stand out at an academic conference is to give a fantastic presentation.

In this post, I will discuss a few simple techniques that can make your presentation stand out. Although, it does take time to make a good presentation, it is well worth the investment.

Tip #1: Use PowerPoint Judiciously

Images are powerful. Research shows that images help with memory and learning. Use this to your advantage by finding and using images that help you make your point. One trick I have learned is that you can use images that have blank space in them and you can put words in those images.

Here is one such example from a presentation I gave about immigration law enforcement.

PowerPoint is a great tool, so long as you use it effectively. Generally, this means using lots of visuals and relatively few words. Never use less than 24-point font. And, please, never put your presentation on the slides and read from the slides.

Tip #2: There is a formula to academic presentations. Use it.

Once you have become an expert at giving fabulous presentations, you can deviate from the formula. However, if you are new to presenting, you might want to follow it. This will vary slightly by field, however, I will give an example from my field – sociology – to give you an idea as to what the format should look like:

- Introduction/Overview/Hook

- Theoretical Framework/Research Question

- Methodology/Case Selection

- Background/Literature Review

- Discussion of Data/Results

Tip #3: The audience wants to hear about your research. Tell them.

One of the most common mistakes I see in people giving presentations is that they present only information I already know. This usually happens when they spend nearly all of the presentation going over the existing literature and giving background information on their particular case. You need only to discuss the literature with which you are directly engaging and contributing. Your background information should only include what is absolutely necessary. If you are giving a 15-minute presentation, by the 6 th minute, you need to be discussing your data or case study. At conferences, people are there to learn about your new and exciting research, not to hear a summary of old work.

Tip #4: Practice. Practice. Practice.

You should always practice your presentation in full before you deliver it. You might feel silly delivering your presentation to your cat or your toddler, but you need to do it and do it again. You need to practice to ensure that your presentation fits within the time parameters. Practicing also makes it flow better. You can’t practice too many times.

Tip #5: Keep To Your Time Limit

If you have ten minutes to present, prepare ten minutes of material. No more. Even if you only have seven minutes, you need to finish within the allotted time. If you write your presentation out, a general rule of thumb is two minutes per typed, double-spaced page. For a fifteen-minute talk, you should have no more than 7 double-spaced pages of material.

Tip #6: Don’t Read Your Presentation

Yes, I know that in some fields reading is the norm. But, can you honestly say that you find yourself engaged when listening to someone read their conference presentation? If you absolutely must read, I suggest you read in such a way that no one in the audience can tell you are reading. I have seen people do this successfully, and you can do it too if you write in a conversational tone, practice several times, and read your paper with emotion, conviction, and variation in tone.

What tips do you have for presenters? What is one of the best presentations you have seen? What made it so fantastic? Let us know in the comments below.

Want to learn more about the publishing process? The Wiley Researcher Academy is an online author training program designed to help researchers develop the skills and knowledge needed to be able to publish successfully. Learn more about Wiley Researcher Academy .

Image credit: Tanya Golash-Boza

Read the Mandarin version here .

Watch our Webinar to help you get published

Please enter your Email Address

Please enter valid email address

Please Enter your First Name

Please enter your Last Name

Please enter your Questions or Comments.

Please enter the Privacy

Please enter the Terms & Conditions

Leveraging user research to improve author guidelines at the Council of Science Editors Annual Meeting

How research content supports academic integrity

Finding time to publish as a medical student: 6 tips for Success

Software to Improve Reliability of Research Image Data: Wiley, Lumina, and Researchers at Harvard Medical School Work Together on Solutions

Driving Research Outcomes: Wiley Partners with CiteAb

ISBN, ISSN, DOI: what they are and how to find them

Image Collections for Medical Practitioners with TDS Health

How do you Discover Content?

Writing for Publication for Nurses (Mandarin Edition)

Get Published - Your How to Webinar

Related articles.

User Experience (UX) Research is the process of discovering and understanding user requirements, motivations, and behaviours

Learn how Wiley partners with plagiarism detection services to support academic integrity around the world

Medical student Nicole Foley shares her top tips for writing and getting your work published.

Wiley and Lumina are working together to support the efforts of researchers at Harvard Medical School to develop and test new machine learning tools and artificial intelligence (AI) software that can

Learn more about our relationship with a company that helps scientists identify the right products to use in their research

What is ISBN? ISSN? DOI? Learn about some of the unique identifiers for book and journal content.

Learn how medical practitioners can easily access and search visual assets from our article portfolio

Explore free-to-use services that can help you discover new content

Watch this webinar to help you learn how to get published.

Finding time to publish as a medical student: 6 tips for success

How to Easily Access the Most Relevant Research: A Q&A With the Creator of Scitrus

Atypon launches Scitrus, a personalized web app that allows users to create a customized feed of the latest research.

FOR INDIVIDUALS

FOR INSTITUTIONS & BUSINESSES

WILEY NETWORK

ABOUT WILEY

Corporate Responsibility

Corporate Governance

Leadership Team

Cookie Preferences

Copyright @ 2000-2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., or related companies. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Rights & Permissions

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.19(9); 2019 Sep

Seven tips for giving an engaging and memorable presentation

Effective and memorable presentations should be fun, and informative for the presenters and the learners. Engaging presenters stimulate connections with the audience. Excellent presentations not only provide information, but also give opportunities to apply new ideas during and after the talk to ‘real-life’ situations, and add relevant ‘take-home’ messages. 1 In this article we highlight educational techniques that can be used to enhance the impact of a presentation. Although all these techniques can be incorporated in the modified form into large plenary lectures, we suggest that the ‘think-pair-share’, ‘role-playing’, and ‘flipped classroom’ techniques may be more effective in smaller classroom settings.

Tip 1: Know your audience—before and during your talk

Every audience has a different level of interest, knowledge, and experience. A presentation about asthma should be different when given to patients compared with intensivists. The presenter should have a clear a priori idea of why the learners are coming to this lecture, what may motivate them, and what would be valuable to them . Whenever feasible, an assessment of the audience's needs is helpful for the presenter to focus on meaningful points. Sometimes needs-based assessments are prepared in advance, depending on the lecture or meeting, and this information may be available from the organisers of the meeting. However, if the information is not available beforehand, there are methods for collecting real-time assessments that are themselves engaging to learners. Another benefit of engaging audiences in this way is that an audience response system (ARS) can provide real-time feedback before, during, and after a presentation. 2 ARS can range from low-technology (hand raising), to newer generation ‘iClicker’ devices, or online websites such as Poll Everywhere, which can also be used to collect free-text responses. The audience's responses can help learners reinforce the importance of the topic, and provide a gauge for the presenter to customise subsequent information. Furthermore, research has shown that incorporation of multiple-choice questions to allow for ‘test-taking’ is an effective way of solidifying new knowledge. 2 Advantages of web-based ARS programs are that they are free, user-friendly, and accessible by various mobile devices. The potential disadvantages are reliability of Wi-Fi or cell phone carrier connectivity in a lecture theatre. In the absence of connectivity, an invitation to raise hands can engage participants, although without anonymity.

Tip 2: Tell a story

Stories connect people. A story that is personal to the speaker can evoke memories that are relatable and add concrete meaning to the presentation. 3 Consider starting your presentation with a story that shows why the topic is important to you. In addition, stories focus the audience on the speaker, rather than a slideshow. Even when the stories are not based on personal experiences, they can invoke learners to imagine themselves in similar situations applying knowledge to solve a problem. Descriptions of clinical cases that focus on initial presentations of patients allow learners to imagine seeing that patient and stimulate critical thinking. Experiencing the case vicariously makes the learning more memorable.

Tip 3: Trigger videos

Trigger videos are short (ideally 30 s to 3 min) audiovisual clips that represent a case or problem. Videos can be created using a handheld video recorder or smartphone, and edited using movie-editing software. Alternatively, videos can be found online and incorporated into presentations with appropriate attributions. Chosen well, trigger videos can present a thought-provoking dilemma that encourages discussion and debate. 4 They can alter the dynamics of a presentation. Success requires careful linking or embedding the videos into the presentation, making sure they play on the computer and projector, and confirming appropriate loudness of the audio settings.

Tip 4: Think-pair-share

When introducing a novel concept to a small group, consider using the ‘think-pair-share’ technique. In this technique, learners first think quietly about the challenging idea, then pair with neighbours to discuss, and then share their collective thoughts with the audience. 5 This technique gives the audience time to pause, think, and reflect on educational content. Encouraging the audience to come to work with the knowledge in a collaborative way incorporates experiential learning into your presentation. To be successful, allow for extra time in the presentation, ensure the audience's seating arrangement is conducive to small conversations, and display summarised ideas for referencing throughout the presentation. 5 , 6

Tip 5: Role play

When presenting an abstract concept that is controversial or thought-provoking, the use of scripted actors can be helpful. Both exemplary and poor examples can be demonstrated for topics such as obtaining informed consent, speaking up about safety concerns, or giving difficult feedback. Similarly, small group role-play can allow audience members to practice and experiment with actions and language with their peers. 7 The instructor should introduce the exercise in a way that helps assure psychological safety among learners, with an emphasis on deliberate practice rather than perfect performance.

Tip 6: ‘Flip’ the classroom

In situations where homework is assigned, consider ‘flipping’ the classroom experience where work is prepared by the learners before the teaching session. Preparatory work can comprise reading material or watching videos of lectures or demonstrations. This allows for more active collaborative learning, for example learners can solve a diagnostic challenge together, debate the pros and cons of a controversial topic, or practice skills. 8 The classroom experience is enriched by the interaction of many learners, rather than the perspective of a single presenter.

Tip 7: Applying the ‘take-home message’

Many are familiar with the framework of ‘ tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then summarise what you just said. ’ We advocate an additional component in the conclusion, where learners are challenged to commit to a change in their behaviour as a result of something they just learned: ‘ What is something you can do differently and better tomorrow or with your next patient as a result of this presentation? ’ Incorporating this question in the evaluation of a presentation can help facilitate behaviour change by having the learners write an example. Similarly, incentives can be offered for behaviour change: ‘ We have your email addresses, and with your permission we would like to follow-up with you in 2 weeks to see if you have any stories to share about applying this new information. We'll be collecting the responses and having a raffle to select one person to receive a gift card... ’ Not only does this provide an incentive to experimentation, but it also gives valuable and often heart-warming feedback to the presenter.

Dynamic educational techniques increase the engagement of the audience. We emphasise the importance of connecting with the learners and obtaining a commitment to apply the new knowledge for change and improvement. The extent to which these techniques are used will depend on the level of audience expertise, time constraints, and access to audiovisual aids. When used, they can result in a more memorable experience for both learners and presenters.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Christine Mai MD MS-HPEd is assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and program director of the Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital. Her clinical and research interests are in simulation education and graduate medical education.

Rebecca Minehart MD MS-HPEd is assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and program director of the Obstetric Anesthesia Fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital.

May Pian-Smith MD is associate professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and director of quality and safety for the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Matrix codes: 1H02, 2H02, 3J02

ISSN 2579-9533 ; pISSN 1410-7201

LLT FULL PAPER TEMPLATE

- Author Guidlines

- Editorial Team

- Advisory Board/Peer Reviewers

- Copyright Notice

- Focus and Scope

- No Author Fees

- Publication Ethics

- Open Access Policy

- Publication Frequency

- Review Process

- Online Submissions

- Originality Screening

- Author Registration

- LLT Contact Info

- Indexing and Abstracting

- Repository Policy

- Visitor Statistics

LLT Journal: A Journal on Language and Language Teaching

Scopus Inclusion Tracking

Accepted date: 8 July 2023 Thank you.

LLT Journal Barcode

(Link to ISSN BRIN)

LLT Journal Stats

View My Stats

- Other Journals

TOOLS

| : |

K.M. Widi Hadiyanti Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia Indonesia

Widya Widya Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia Indonesia

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

OUR CONTACT

LLT Journal English Language Education Sanata Dharma University Yogyakarta, Indonesia

For more details, please visit: LLT Journal Contact Address

- Announcements

- REVIEW PROCESS

- ADVISORY BOARD/PEER REVIEWERS

ANALYZING THE VALUES AND EFFECTS OF POWERPOINT PRESENTATIONS

Abdellatif, Z. (2015). Exploring students perceptions of using PowerPoint in enhancing their active participation in the EFL classroom: Action research study. Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, 55, 36-39.

Ahmad, J. (2012). English Language Teaching (ELT) and integration of media technology. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47(2012), 924-929.

Anh, N. T. Q. (2011). Efficacy of PowerPoint presentations: students perception. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (pp. 1-9). Malaysia.

Bartsch, R. A., & Cobern, K. M. (2003). Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Computers & Education, 41(2003), 77-86.

Corbeil, G. (2007). Can PowerPoint presentations effectively replace textbooks and blackboards for teaching grammar? Do students find them an effective learning tool? CALICO Journal, 24(3), 631-656.

Craig, R. J., & Amernic, J. H. (2006). PowerPoint presentation technology and the dynamics of teaching. Innov High Educ, (31), 147-160.

Daniels, L. (1999). Introducing technology in the classroom: PowerPoint as a first step. Journals of Computing in Higher Education, 10(2), 42-46.

Davies, T. L., Lavin, A. M., & Korte, L. (2009). Student perceptions of how technology impacts the quality of instruction and learning. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 2-16.

Fisher, D. L., (2003). Using PowerPoint for ESL teaching. The Internet TESL Journal, 9(4). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Fisher-PowerPoint.html

Frey, B. A., & Birnbaum D. J. (2002). Learners perceptions on the value of PowerPoint in lectures. Education Resources Information Center, 1-9.

Howard, G. S., & Conway, C. G. (1985). Construct validity of measures of college teaching effectiveness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 187-196.

Khoury, R. M., & Mattar, D. M. (2012). PowerPoint in accounting classrooms: Constructive or destructive? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(10), 240-259.

King, L. (2010). The science of psychology: An appreciative view. New York: McGraw Hill.

Morgan-Thomas, Maxine. (2014). Acting out in class: the group role-play advantage over PowerPoint presentation. Journal of Legal Studies in Business.

Oommen, A. (2012). Teaching English as a global language in smart classrooms with PowerPoint presentation. English Language Teaching, 5(12), 54-61.

Ozaslan, E. N., & Maden, Z, (2013). The use of PowerPoint presentations in the Department of Foreign Language Education at Middle East Technical University. Middle Eastern & African Journal of Educational Research, (2), 38-45.

Schcolnik, M., & Kol, S. (1999). Using presentation software to enhance language learning. The Internet TESL Journal, 5(3). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Schcolnik-PresSoft.html

Sewasew, D., Mengestie, M., & Abate, G. (2015). A comparative study on PowerPoint presentation and traditional lecture method in material understandability, effectiveness and attitude. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(2), 234-243.

Shyamlee, S. D., & Phil, M. (2012). Use of Technology in English language teaching and learning: An analysis. 2012 International Conference on Language, Medias and Culture (pp. 150-156). Singapore.

Struyven, K., Dochy, F., & Janssens, S. (2005). Students perceptions about evaluation and assessment in higher education: A review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 325-341.

Susskind, J. E. (2004). PowerPoints power in the classroom: Enhancing students self-efficacy and attitudes. Computers & Education, 45(2005), 203-215.

Szabo, A., & Hastings, N. (2000). Using IT in the undergraduate classroom: Should we replace the blackboard with PowerPoint? Computers & Education, 35(2000), 175-187.

Taylor, G. (2012). Making a place for PowerPoint in EFL classrooms. OnCUE Journal, 6(1), 41-51.

Yilmazel-Sahin, Y. (2007). Teacher education students perceptions of use of MS PowerPoint and the value of accompanying handouts (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Maryland, College Park, United States of America).

- There are currently no refbacks.

Indexed and abstracted in:

LLT Journal Sinta 2 Certificate (S2 = Level 2)

We would like to inform you that LLT Journal: A Journal on Language and Language Teaching has been nationally accredited Sinta 2 by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia based on the decree No. Surat Keputusan 158/E/KPT/2021. Validity for 5 years: Vol 23 No 1, 2020 till Vol 27 No 2, 2024

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA.

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

COMMENTS

The "presentation slide" is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what ...

Despite the prevalence of PowerPoint in professional and educational presentations, surprisingly little is known about how effective such presentations are. All else being equal, are PowerPoint presentations better than purely oral presentations or those that use alternative software tools? To address this question we recreated a real-world business scenario in which individuals presented to a ...

There is nothing more frustrating than sitting through a presentation bombarded by slide after slide of small text, difficult to read graphs, irrelevant clip art images, and poorly designed templates. Often to blame is the use and abuse of PowerPoint 1 (e.g., Tufte, 2003; Bumiller, 2010 ). Academics typically only endure weak PowerPoint ...

The tools provided in this article can help you develop a presentation that will be meaningful and impactful to your audience. It is a great feeling when audience members come to you after your presentation to share with you how much they enjoyed and learned from your talk. ... Wax D. 10 tips for more effective PowerPoint presentations. 2017 ...

Like any technology, the effective use of PowerPoint requires that it be integrated effectively into the human-technical system. A variety of HF/E principles with a long history can be used to improve the PowerPoint presentation, just as such principles can improve any display used by humans to accomplish a task.

Abstract. Nowadays, PowerPoint is an educational tool for teaching and delivering materials in classes. It was basically developed for presentation and not essentially for teaching and learning in a classroom. Its applications in teaching and learning settings should provide better means of communicating information to the students.

A dynamic presentation culture, in which every presentation is understood, fairly critiqued and useful for its audience, can only be good for science. Nature 594 , S51-S52 (2021) doi: https://doi ...

Highlights. •. This is a meta-analysis on using PowerPoint to supplement traditional teaching. •. 48 studies were included over a 22-year period. •. PowerPoint had no effect on students' cognitive learning. •. Moderators (e.g., subject matter, sample type, learning measurement, and study method) were considered to explain heterogeneity.

Beyond bullet points: Using Microsoft PowerPoint to create presentations that inform, motivate, and inspire. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press. Google Scholar. ... Professional presentations with PowerPoint]. Den Haag, Netherlands: Academic Service. Google Scholar. Cyphert D. (2004). The problem of PowerPoint: Visual aid or visual rhetoric? ...

Abstract. The use of PowerPoint for teaching presentations has considerable potential for encouraging more professional presentations. This paper reviews the advantages and disadvantages associated with its use in a teaching and learning context and suggests some guidelines and pedagogical strategies that need to be considered where it is to be used.

PowerPoint is one of the most widely used technological tools in educational contexts, but little is known about the differences in usage patterns by faculty members from various disciplines. For the study we report in this article we used a survey specially designed to explore this question, and it was completed by 106 faculty members from different disciplines. The results suggest the ...

2. Literature Review Microsoft Power-Point is a presentation program developed by Microsoft. It is a part of the Microsoft Office system which is widely used by business people, educators, students, and trainers. As a part of the Microsoft Office suite, Power-Point has become the world's most widely used presentation program.

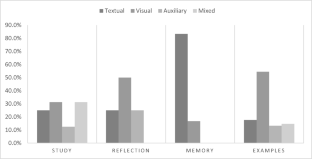

combined image-text presentations to biology students, the authors found that image-only presentations had a positive impact on students' academic performance. Similarly, Cladellas and Castelló (2017) found that the text-only format did not contribute to a better academic performance with a sample of medical students. On the other hand,

Few data support superior learning effectiveness of PowerPoint as compared with older tools such as 35-mm slides and the chalkboard . In response to these problems, newer presentation tools have emerged that provide opportunities for more engaging lectures . One such alternative is Prezi, a web-based tool that presents information using spatial ...

Introduction. PowerPoint is a widely used teaching tool in higher education for many years now. One of the benefits of this technology is its potential to enhance students' engagement and empower effective learning [1-3].Moreover, this technology helps students to organise their notes if they use it as a starting point to expand their knowledge from assigned textbooks.

This article from The Chronicle of Higher Education highlights a blog moderated by Microsoft's Doug Thomas that compiles practical PowerPoint advice gathered from presentation masters like Seth Godin, Guy Kawasaki, and Garr Reynolds.; Bibliography. Presenting to Win: The Art of Telling Your Story, by Jerry Weissman, Prentice Hall, 2006 Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design ...

The purpose of this study was to identify the effect of using PowerPoint presentations in academic achievement of Social and National Studies in the fifth grade students at-risk for learning … Expand. 2. PDF. ... Power point Presentations are utilized by almost the whole faculty in the department of Foreign Language Education.

Advantage of using Power Point presentations in EFL classroom. International Journal of . English Language and Translation Studies, 1, 3-16. ... academic language use, professional development ...

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor's standpoint. I've presented my own ...

While active-learning strategies are not mutually exclusive with the use of PowerPoint presentations in the dissemination of information, they do require thoughtful design, time for reflection, and interaction to achieve deeper levels of learning (Chi and Wylie, 2014). This may be as simple as allowing 30-60 seconds for prediction or ...

Tip #1: Use PowerPoint Judiciously. Images are powerful. Research shows that images help with memory and learning. Use this to your advantage by finding and using images that help you make your point. One trick I have learned is that you can use images that have blank space in them and you can put words in those images.

Excellent presentations not only provide information, but also give opportunities to apply new ideas during and after the talk to 'real-life' situations, and add relevant 'take-home' messages. 1 In this article we highlight educational techniques that can be used to enhance the impact of a presentation. Although all these techniques can ...

Oommen, A. (2012). Teaching English as a global language in smart classrooms with PowerPoint presentation. English Language Teaching, 5(12), 54-61. Ozaslan, E. N., & Maden, Z, (2013). The use of PowerPoint presentations in the Department of Foreign Language Education at Middle East Technical University.