The power of role models in education: fostering integrity and respect

- Better future , Resources

- Madrid , Spain

Virtus College, The British Sixth Form

- February 9, 2024

In education, the significance of role models is often understated. A school is not just an institution for academic learning; it’s a vibrant community where every individual, from teachers to catering workers, plays a pivotal role in shaping the environment. At the heart of this community lies a fundamental truth: everyone is a role model.

What is a role model in education?

The concept of role modelling in schools extends beyond the conventional teacher-student dynamic. It encompasses every interaction within the school premises.

Teachers, who are traditionally seen as the primary role models, carry the responsibility of punctuality and dedication to their lessons. Their commitment sets a standard for students, subtly instilling the values and life skills of time management and responsibility.

Who are the role models in a school?

Role modelling isn’t confined to the classroom. The way the whole staff interact with students, offering politeness and kindness, contributes to a nurturing and respectful atmosphere. Such interactions, though seemingly small, play a crucial role in teaching students the importance of courtesy and respect in everyday life.

Older students, too, are integral role models for their younger peers. Their attitudes, behaviours, and even their approach to learning and school life set an example. This aspect is particularly important as students often relate more closely to their peers. The way older students navigate their academic and social lives can significantly influence the attitudes and choices of younger students.

The school’s environment also extends respect and recognition to those who work behind the scenes, like cleaners and administrative staff. Teaching students to be respectful to everyone, without exception, fosters a culture of inclusivity and appreciation for all contributions, regardless of the role.

Psychological studies suggest that individuals are, to a large extent, a product of their environment and the people they spend the most time with. In the context of a school, this means that every interaction, every observed behaviour, and every expressed attitude has the potential to influence. Understanding this interconnectedness is crucial in realising that each one of us, knowingly or unknowingly, is a role model to others.

Benefits of role models in students’ education

At the core of effective role modelling lies integrity. It’s about aligning actions with words, demonstrating the values we advocate. This alignment is critical in education where young minds are constantly observing and learning from those around them:

- Influence on behaviour and attitude: Role models significantly influence the behaviour and attitudes of students. When students see positive behaviours and attitudes modelled by their teachers and peers, they are more likely to emulate these traits. This modelling can lead to a more positive school culture and better student behaviour both in and out of the classroom.

- Academic motivation and performance: Role models can inspire students to strive for academic excellence. Teachers who are passionate about their subjects can ignite a similar passion in their students, leading to enhanced engagement and performance. Additionally, seeing older students or alumni succeed can motivate younger students to work harder and aim higher.

- Development of social and emotional skills: Effective role models help students develop essential social and emotional skills such as empathy, resilience, and effective communication. By observing and interacting with role models who demonstrate these skills, students learn how to navigate social situations and build healthy relationships.

- Reinforcement of values and ethics: Role models play a vital role in reinforcing values and ethics in students. Educators who demonstrate integrity, respect, and fairness not only teach these values but also show students how to live them out in real-life situations.

- Building confidence and self-esteem: When students see role models who they can identify with overcoming challenges and achieving success, it can boost their confidence and encourage them to overcome their own obstacles.

- Encouraging lifelong learning: Role models who are lifelong learners inspire students to value education beyond the classroom. They show that learning is a continuous process and encourage curiosity and exploration.

Role models at Virtus, The British Sixth Form College

Virtus, The British Sixth Form College, stands as a testament to the importance of role modelling in education. At Virtus, every member of the community, from staff to students, is seen as a role model. The school emphasises not just academic excellence but also the development of character and integrity.

Teachers at Virtus are more than educators; they are mentors who exemplify punctuality, dedication, and a passion for their subjects. Their commitment goes beyond the syllabus, inspiring students to pursue excellence in all facets of life.

Older students at Virtus are encouraged to lead by example, understanding their influence on their younger peers. They are guided to be mindful of their actions, aware that they are setting standards for the school’s culture.

Moreover, the respect for all staff, including those who work behind the scenes, is ingrained in the ethos of Virtus. This approach nurtures an environment of mutual respect and appreciation, crucial for holistic development.

In recognising and embracing our role as influencers at Virtus, we foster a culture of integrity, respect, and continuous improvement, preparing students not just for academic success, but for life.

Personalised education in schools

The importance of Co-Curricular activities for students

Guide to accessing the best universities in the UK and the Netherlands

What are the examination boards of the British System?

The BHS Method: A Transformative Approach to Education

Revolutionizing Education: The Rise of the Social Wellness School for a Post-COVID World

Find a school.

Adult Online Courses

Global Training Solutions For Individuals and Organizations

Leading by Example: Role Models in Education

Imagine a world where students are inspired not just by what they are taught, but by who teaches them. A world where educators serve as beacons of inspiration, leading by example and shaping the minds and hearts of the next generation.

In this world, role models in education play a pivotal role in the growth and development of students. But what does it mean to be an effective role model? How does the presence of a role model impact a student's educational journey? And how can teachers cultivate a culture of role modeling in schools?

Step into the realm of leading by example, where the answers to these questions await.

Key Takeaways

- Role models in education provide real-life examples of success and inspiration, motivating students to achieve their goals.

- Effective role models possess qualities such as empathy, integrity, and a growth mindset, fostering trust and admiration in students.

- Role models have a significant impact on student development, influencing positive behavior, academic performance, and personal growth.

- Teachers can lead by example by maintaining professionalism in actions and appearance, creating a culture of role modeling in schools through mentor relationships and exposure to diverse role models.

Importance of Role Models in Education

Role models play a crucial role in education by providing students with real-life examples of success and inspiration. The impact they have on student motivation is immense. When students see someone who has achieved their goals and overcome obstacles, it gives them the belief that they can do the same.

Role models show students that hard work, determination, and perseverance can lead to success. This motivation can be the driving force behind a student's desire to excel in their studies and reach their full potential.

In addition to motivating students, role models also play a significant role in building self-confidence. Seeing someone they admire and respect achieve their goals can give students the confidence to believe in themselves and their abilities. Role models serve as a reminder that success is attainable and that they too can accomplish great things.

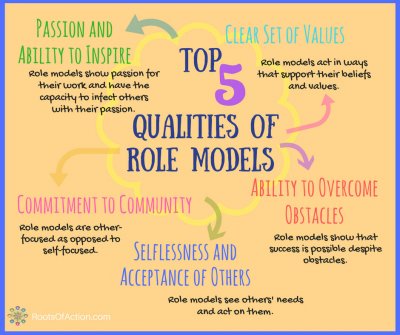

Qualities of Effective Role Models

Effective role models possess specific qualities that make them influential and inspiring figures in the lives of students. Here are some key qualities that contribute to their effectiveness:

- Empathy : Effective role models have the ability to understand and share the feelings of their students. They're compassionate and supportive, providing a safe and nurturing environment for growth and development.

- Integrity : Role models with integrity act in alignment with their values and principles. They demonstrate honesty, fairness, and ethical behavior, serving as a moral compass for their students.

- Growth mindset : Effective role models embrace a growth mindset, believing that abilities and intelligence can be developed through effort and perseverance. They encourage their students to embrace challenges, learn from failures, and continuously strive for improvement.

These qualities foster trust, respect, and admiration in students, making them more likely to emulate the behavior and values of their role models. By embodying these qualities, effective role models inspire and empower their students to reach their full potential.

Impact of Role Models on Student Development

Role models have a significant influence on student growth, inspiring them to adopt positive behavior and attitudes. By observing the actions and values of role models, students are motivated to strive for excellence and make responsible choices.

Moreover, role models can also play a crucial role in enhancing students' academic performance by instilling a strong work ethic and a passion for learning.

Influence on Student Growth

Teachers who serve as positive role models have a significant impact on the growth and development of their students. They've the power to influence student motivation, inspiring them to strive for excellence and reach their full potential. By setting high expectations and demonstrating a strong work ethic, role model teachers show students the importance of hard work and dedication.

They also play a crucial role in fostering personal growth by providing guidance and support. Through their actions and behaviors, these teachers teach students valuable life skills such as resilience, perseverance, and integrity. Moreover, they serve as a source of inspiration, showing students that with determination and a positive mindset, they can overcome obstacles and achieve success in their academic and personal lives.

Inspiring Positive Behavior

As students observe their teachers' behavior and actions, they're inspired to adopt positive behaviors themselves, leading to their overall development and growth.

Teachers play a crucial role in inspiring motivation and fostering self-confidence in their students. When students witness their teachers displaying positive behaviors such as kindness, respect, and perseverance, it encourages them to follow suit.

By consistently demonstrating these qualities, teachers become role models who inspire their students to strive for excellence and make positive choices.

Moreover, teachers who show belief in their students' abilities instill a sense of self-confidence in them. This confidence empowers students to believe in themselves, take risks, and overcome challenges.

Ultimately, the influence of positive role models in education goes beyond academic development, shaping students into well-rounded individuals who are motivated, confident, and equipped to succeed in life.

Enhancing Academic Performance

Students who have positive role models in their education experience enhanced academic performance and overall personal development. Role models can have a significant impact on student motivation and success. Here are three ways in which role models enhance academic performance:

- Setting high expectations : Positive role models, such as teachers or mentors, inspire and challenge students to strive for excellence. By demonstrating their own dedication and passion for learning, role models encourage students to set high expectations for themselves.

- Providing guidance and support : Role models offer guidance and support to students, helping them navigate academic challenges. Their presence and involvement in a student's education can significantly impact their academic performance.

- Involving parents : Role models also play a crucial role in engaging parents in their child's education. When parents see the positive effects of role models on their child's academic performance, they're more likely to become actively involved in their education.

Strategies for Teachers to Lead by Example

To be an effective role model in education, there are several strategies teachers can employ.

First, maintaining a professional dress code sets a positive example for students and shows them the importance of presenting oneself in a professional manner.

Additionally, demonstrating professionalism in actions, such as being punctual and organized, teaches students the value of responsibility and professionalism.

Teacher Dress Code

Teachers play a crucial role in setting a positive example through their dress code choices. By adhering to a professional dress code, teachers demonstrate their commitment to professionalism and create a respectful learning environment.

Here are three key points to consider when it comes to teacher dress code:

- Appropriate attire : Teachers should dress in a manner that's appropriate for their educational setting. This means avoiding clothing that's too casual or revealing, and opting for clothing that's clean, neat, and modest.

- Role modeling : Teachers serve as role models for their students, and their attire can influence how students perceive and behave in the classroom. Dressing professionally can inspire students to take their own appearance and behavior more seriously.

- School policies : It's important for teachers to familiarize themselves with their school's dress code policies. By following these policies, teachers not only demonstrate respect for their institution, but also contribute to a cohesive and unified school community.

Professionalism in Actions

As teachers set a positive example through their dress code choices, they also have the opportunity to lead by example in their actions, demonstrating professionalism and inspiring students to follow suit.

Professionalism in actions encompasses ethical behavior and high standards of conduct in the classroom. By maintaining a respectful and inclusive learning environment, teachers can promote ethical behavior among their students. This includes treating all students with fairness and respect, actively listening and responding to their needs, and being consistent in their disciplinary approach.

Teachers should also demonstrate punctuality and preparedness, showing students the importance of being responsible and organized. By modeling professionalism in their actions, teachers can instill these valuable traits in their students, preparing them for success in their future endeavors.

Consistent Classroom Expectations

Consistently setting clear expectations in the classroom is essential for teachers to lead by example. By establishing consistent discipline, you create a structured environment where students know what's expected of them. This consistency helps students feel secure and allows them to focus on their learning. It also promotes a positive teacher-student relationship, as students understand that you're fair and consistent in your approach.

To ensure consistent classroom expectations, consider the following strategies:

- Clearly communicate your expectations : Use clear and concise language to outline your expectations for behavior, work completion, and participation.

- Reinforce expectations regularly : Remind students of the expectations consistently and provide positive reinforcement when they meet them.

- Model the behavior you expect : Show students how to meet the expectations by consistently demonstrating them yourself.

Promoting Diversity in Role Models

Promoting diversity in role models is essential for fostering an inclusive and equitable educational environment. Inclusion in representation is key to ensuring that all students feel seen, heard, and valued. By showcasing a diverse range of role models, educators can break stereotypes and challenge societal norms. When students see people who look like them, come from similar backgrounds, or have similar experiences, they're more likely to believe that they too can achieve greatness.

By promoting diversity in role models, we can help students expand their perspectives and gain a deeper understanding of the world around them. When students are exposed to role models from different races, cultures, genders, abilities, and socio-economic backgrounds, they learn to appreciate diversity and develop empathy for others. This not only prepares them for the diverse society they'll encounter outside of school, but also helps them become more well-rounded individuals.

Furthermore, promoting diversity in role models encourages students to challenge stereotypes and think critically about societal norms. When students see role models who defy expectations and succeed despite facing adversity, they're inspired to question limitations placed on them by society. This can lead to a greater sense of empowerment and motivation to overcome obstacles.

Creating a Culture of Role Modeling in Schools

By fostering a culture of role modeling in schools, students are provided with opportunities to learn from and be inspired by individuals who exemplify the qualities and values that promote success and personal growth. Creating a supportive environment where role models are celebrated and encouraged can have a profound impact on the development of students.

Encouraging mentor relationships:

Schools can actively promote mentorship programs where older students or community members are paired with younger students. These mentor relationships provide guidance, support, and a positive example for students to follow.

Showcasing diverse role models:

It's important to ensure that students are exposed to a wide range of role models from different backgrounds, cultures, and professions. This diversity helps students understand that success can come in various forms and encourages them to embrace their own unique qualities.

Recognizing and celebrating achievements:

Acknowledging and celebrating the accomplishments of both students and staff members can inspire others to strive for greatness. Recognizing role models within the school community reinforces the value of hard work, dedication, and perseverance.

In conclusion, having effective role models in education can greatly impact student development. Research shows that students who have positive role models are more likely to achieve academic success, develop strong character traits, and make positive life choices.

According to a study conducted by the University of California, students who had a role model in their lives were 52% more likely to graduate from high school and attend college. Therefore, it is crucial for teachers to lead by example and promote diversity in role models to create a culture of role modeling in schools.

The eSoft Editorial Team, a blend of experienced professionals, leaders, and academics, specializes in soft skills, leadership, management, and personal and professional development. Committed to delivering thoroughly researched, high-quality, and reliable content, they abide by strict editorial guidelines ensuring accuracy and currency. Each article crafted is not merely informative but serves as a catalyst for growth, empowering individuals and organizations. As enablers, their trusted insights shape the leaders and organizations of tomorrow.

Similar Posts

Understanding and Managing Emotions for Better Learning

Uncover the secrets to understanding and managing emotions for better learning outcomes, and discover how it can transform your learning journey.

Study Skills and Techniques for Students

Hone your study skills with effective techniques and get ready to unlock a whole new world of academic success.

Ethics and Integrity in Teaching

Uncover the secrets of ethical teaching as we delve into the impact of integrity in the classroom and the keys to creating an ethical classroom culture.

Curriculum Development and Assessment Techniques for Educators

Hungry for knowledge about curriculum development and assessment techniques? Discover the key strategies and techniques that will help you excel in this important aspect of your role as an educator.

Parent-Teacher Partnerships and Community Engagement

Just imagine the endless possibilities and benefits that can come from building strong parent-teacher partnerships and engaging with the community.

How Developing Soft Skills Can Transform a Student’s Academic Journey

While hard skills such as writing well, doing maths, or performing a scientific experiment are essential in the academy, soft skills are also essential. These non-technical abilities allow you to thrive in your environment, work with others, and achieve your goals. For students, developing these skills can improve the quality of their education and pave…

25 Ways Teachers Can Be Role Models

Reviewed by Jon Konen, District Superintendent

There are many reasons why students think of teachers as role models. One of the biggest reasons is the desire to become a role model for students to look up to, to learn from, and to remember for the rest of their lives. Everyone has felt the power and lasting presence of an effective teacher, who also had a bigger impact. Whether it’s learning the value of community service, discovering a love for a particular subject, or how to tap the confidence to speak in public, teachers are the ones who light the way for us in this world.

Teachers being role models is not a new concept, and has inspired students to go into this field for ages. If you are thinking about becoming a teacher, good for you! We are here to root you on and help you make the right decision. Your next step would be speaking with schools in your area. Luckily, we have relationships with schools in every state with education programs. Just use the simple search function at the top of this page, or browse the listings below.

Before we start talking about things that make us thing of educators as role models, we are well aware this list is not complete. If you have any additional ideas or inspirational stories to share, we would love to hear from you!

Here are 25 ways of the importance of teachers

1.) Be humble. There is nothing that teaches a child or young adult mature behavior like modeling it yourself. This isn’t just true when you are right. You also have to show your students what it is like to be wrong, and admit it. This is never easy, no matter how old you are. Especially when you are in front of several students who look up to you. And let’s face it, there are some students who aren’t going to feel sorry for you. But that’s life. And you have to show them that right is right, and wrong is wrong – no matter what.

2.) Encourage them to think for themselves. Treat your classroom like a group of individuals, and celebrate their diversity. Create activities and discussions that foster conversations and discovery about who they are, and how they can appreciate the differences between each other. This type of focus from time-to-time will build a stronger bond between your students. Also, an environment of trust will build, which can relax the atmosphere and help students focus more on learning. It’s also important to help students understand the way they learn, and encourage them to explore those parts of themselves as well.

3.) Perform volunteer work. Find a way to incorporate community service into one of your lessons, and discuss how you contribute to the community you live in. Ask your students to tell you ways you could perform community service as a group. Many schools will give students a certain amount of time off if they are doing an activity that falls into this category. See if you can organize a community service event with your class. For example, if you are a music teacher, you can take your class caroling at a retirement home. Or, you can have your class pick up litter on a stretch of road. There are many ways you can instill a sense of pride in giving back among your students.

4.) Show empathy. When we think of teachers as role models, we imagine sympathetic mentors who listen to their students. Sounds simple, right? All you have to do is show that you care? It may sound simple, but we have all had teachers that we didn’t connect with. Students can tell when a teacher is tuned in or tuned out, and disconnected from them. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have all had teachers who went out of their way to show they care about us, and want to see us succeed. We all have different personalities, and you should be authentic. But be mindful that your students are looking up to you as an adult with life experience they don’t have. As they try to figure out how to move into adulthood, make sure they know you’ve got their back.

5.) Point out the positive. Create a culture in your classroom that rewards kind behavior. The importance of teachers is apparent in the link between positive reinforcement and their confidence and behavior. Teach them to be constructive with their criticism, pointing out positives before negative, or suggestions for improvement. Practice with exercises that allows the students to be positive and critical towards each other. This is the kind of respect that debate class exercises can teach children – how to agree to disagree. Teaching children to get in the habit of looking for good in others is never a bad role model for behavior.

6.) Celebrate the arts. Teachers being role models by helping students appreciate the arts isn’t the first thing that comes to people’s minds. But helping children connect with their own inner children by tapping into the arts. Even if you do not teach a creative subject, you can incorporate music, discussions about art, and give students artistic assignments that reflect the curriculum they are learning. Mixing it up every once in a while will keep their minds fresh, and encourage them to look at life a little differently. Many students are obsessed with music, art, literature and other forms of creative expression. Give bonus points for students who pursue an independent art project that goes along with a teaching.

7.) Send a positive note home to their parents twice a year. Showing your students that you appreciate them in a direct way is important. But indirect forms of gratitude can be a boost to their confidence, and model positive behavior. Most parents never expect to get a note in their kid’s bag saying what a pleasure they are to have in class. So why not give your kids a boost and let mom and dad know you care? Every parent knows, we just want our kids to do well and succeed, no matter where they are in life. This will help your relations with them as well. And we have a feeling your students will appreciate any effort you make to let their parents know they’re doing alright.

8.) Fulfill your promises. Hey, remember last fall when you said you would buy the class a turtle if they earned all those stars? Well, it’s been six months since they earned em and school is almost over… Okay, don’t be that teacher. We’re all busy. Even your students. That’s why you need to follow through on your promises when you make them. We don’t want to them to think it’s okay to say one thing, and then completely disregard it. And if you fail to keep a particular promise, be honest about it. Don’t make up an excuse. And try to make up for it. Your students will see how to deal with their own shortcomings, and will respect you more for your honesty.

9.) Dress appropriately. Look, we know how young and hip you still are. No one wants to be uncool. But teachers being role models means remembering you are in a professional environment. And it’s not your job to fit in with the cool kids. It’s your job to stand at the head of the class and foster a sense of mutual respect. After all, you want to model professional behavior for your students from day one. This will help with classroom management issues. Dressing in a professional way will keep students from thinking of you in a less respectful way. This goes for cleanliness and hygiene as well. Just make sure you take your job seriously when you show up. This is not only good to model for your students, but important in the eyes of your principal and other administrators as well.

10.) Stay away from social media with students. Educators as role models on social media is a new and important topic. Do not mix on social media with your students. And be careful what you have out there on your personal accounts. We are all too familiar with the stories of teachers and other professionals doing something unprofessional and getting fired for it. Have a policy to connect with students on the channels that your school sets up for you. Remember, parents are looking at you as well, and know that you are in a role model position with their children. When you post on social media, just realize that your students’ parents could see your words as well. Just be careful.

11.) Encourage physical activity. The importance of teachers extends to the physical fitness of their students. It doesn’t matter if every student is inclined to be physically active. Encouraging physical activity is good for all groups of students. Even if you do not teach a physical education class, you can still talk about physical activities when you lecturing or performing other activities. Even weaving the topic into your lectures or conversations can help plant the seeds in students’ minds that they should look for ways to exercise.

12.) Give lectures about role models. When you are discussing a period in history, or introducing a new subject to your students, find a way to incorporate a hero story into the lesson. For instance, if you are going to talk about French history and the Hundred Years War, you would talk about the bravery of Joan of Arc. Or you could find stories about other unlikely heroes, and those who shaped history. When you do, have your students discuss ways they can be heroes in their own lives. Even if it’s just stepping up in small ways to help others or do things they didn’t think possible.

13.) Have them read Profiles in Courage. When we think of teachers as role models, we think of the classic novels and literature they shared with us. John F. Kennedy’s Nobel Prize winning book chronicles the acts of courage by several figures throughout American history. These characters were brave enough to make tough choices in hard times, putting their country before themselves, and their personal safety. Other books can be great options, such as To Kill A Mockingbird or movies like Good Will Hunting, when you want to give your kids a break, and teach them a lesson in doing the right thing. Being a good role model for kids means showing them how to point their moral compass in the right direction no matter what. The importance of teachers cannot be overstated when it comes to reading.

14.) Hold a fundraiser. Pick a local charity and tell your students you have a goal to raise a certain amount of money within a certain period of time. You will all make a game of raising the most money and giving it to a charity. It can even be a non-organized charity. Let’s say you hear about someone in your community who lost their home to a fire. You could raise the money and give them a gift card or something they may need. There are all sorts of ways you can incorporate the idea of fundraising and charity. Be sure to include all your students in the process somehow. These types of exercises can also help give them leadership and business skills.

15.) Discuss world events. Every Monday, or on some kind of schedule, spark discussions about world events. See what they know, and ask questions that make them think. Teachers being role models includes showing students how to make sense of the world, and express different ideas in a peaceful way. This can model for students how they should act when they speak with others, and how to actively listen to other points of view. Many students will not have heard about some of the events you are speaking about. Don’t let them sit back quietly. Find ways to involve them too, by asking questions that can draw them in.

16.) Have a pot luck. Every once in a while, have a meal with your students that celebrates you time together. Yes, food is another way students can see educators as role models. So have fun with this one. After all, we all love food! Tell your students that they are welcome to bring a dish from home, or you can provide a cheap set of snacks. This can be a good way to talk about cooking with your students. Many kids aren’t involved in with the cooking at their homes. Some parents teach their kids about food, but it’s probably the exception, not the norm. So, be that teacher that shows them that they can learn to cook and eat healthy foods. You can show them that good food can also be good for you!

17.) Work extracurricular activities. When your students see you working outside of the classroom to help your school function, it says you go the extra mile. It also shows that you have a strong work ethic, and you are doing a job that you’re passionate about. That is the kind of feeling you want your students to have from their careers later in life. Show them that you enjoy your job, and it will pay off in the classroom. And, if you were once a star athlete and have coaching skills, you can be a role model for the students playing sports in a similar way.

18.) Be organized and on time. You want to present yourself in a professional way as much as possible. This means more than looking the part and acting the part, it means being the part. The best way you can show your students how to execute their work is to show up on time and be ready to teach. Plus, if you have a clear vision for how you want the lesson to go, then you will be more effective in delivering your message.

19.) Practice random acts of kindness. Here’s an idea for teachers as role models: How about you put an apple on every one of your students’ desks on the first day of school? How would that be for a proactive show of appreciation from the get-go with your class. That would also put them on notice that you are the type of teacher who will surprise them from time to time. This teaches children to go out of their way to show appreciate – even if it’s just for the heck of it.

20.) Ask for input. You know that suggestion box that companies sometimes have for employees to make recommendations? These can be ideas for lectures, field trips, and other things the students think may add to the learning environment. The importance of teachers in showing students how to participate in conversations is essential to their growth. Giving them a feeling of ownership and participation in the class decisions and idea generating process will give them a sense of pride they may not have otherwise; especially if you agree to test their idea out.

21.) Apply democratic ideals to class discussions. Just because your students may not be old enough to vote, doesn’t mean they can’t get a feel for our democratic processes. Teachers being role models to show how our democracy works can be a great lesson for students. Hold votes on decisions that reflect discussions you are having on topics to see where people stand. Then encourage debate and explain to them how our system is supposed to work. No matter where your students might fall on the political spectrum, you can set a good example by engaging them with our core values.

22.) Invite guest lecturers. Find role models in the community that do good work, or perform some kind of public service. This can be small business owners, individuals, city officials, and other notable figures who can inspire the children to do good in their lives. Plus, it’s always fun for students to learn from other people than just their own teacher. Kids need lots of role models in their lives. Plus, whoever you invite will get to share a personal story from their life, or show them how they work in their profession. There are just too many reasons why this can be a great idea!

23.) Make them keep journals. You can inspire your students to understand that it helps to keep track of your thoughts as a way of organizing your goals, connecting with your feelings, and making sense of the world around you. Your students will improve on their own communication skills through their writing practice, and have a safe space to explore their thoughts, during an otherwise hectic daily routine. When you teach students to understand themselves a little better, they will start to see educators as role models.

24.) Start a class garden. Many schools have room for classes to start their own small garden. If not, check with your county office to see if there is any land available where you can make a community garden. This can teach students about growing food, and how people have to work together to sustain our standards of living.

25.) Make them give a presentation on one of their role models. Lastly, have your students think about what makes a good role model, and present their findings to the class. It can be a famous example, or anyone who inspires your student to present. Try not to create too many rules for your students to abide by. See where their minds go, and what qualities they associate with the term.

In what ways do you think you can be a role model to your students?

There must be a million ways teachers can be stand-up role models for their students. Surely, you have a few bouncing around in your head, right? If so, share them with us on social media. Or, leave a comment below.

If you’re ready to learn more about making an impact in students’ lives as a teacher, just use our directory of schools to find out more about programs near you. All you have to do is choose your state to narrow your options.

- (888) 506-6011

- Current Students

- Main Campus

- Associate Degrees

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Post-Master’s Degrees

- Certificates & Endorsements

- View All Degrees

- Communications

- Computer Science

- Criminal Justice

- Humanities, Arts, and Sciences

- Ministry & Theology

- Social Work

- Teaching & Education

- Admission Process

- Academic Calendar

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Military Education Benefits

- Transfer Students

- Tuition & Costs

- Financial Aid

- Financial Aid FAQ

- Online Student Testimonials

- Student Services

- Resource Type

- Program Resources

- Career Outcomes

- Infographics

- Articles & Guides

- Get Started

Teacher Role Models: How to Help Students Who Need It Most

Being a teacher is the best job in the world but also very difficult. Each day brings new challenges, and each year brings new students. Getting to be a role model for these students has always been something I don’t take lightly.

I teach at a district where students don’t always have the best role models at home, and the eight hours they spend with me each day means so much. Teaching students how to treat others and how to react in situations and conflict is something I try and do each and every day.

There will always be students who don’t like school, and the last thing they want to do is sit there and learn. It is our job as educators to show them that learning is fun, and it can take you to amazing places in your future. Showing students how important education is can be hard when they don’t have those role models in their lives outside of school.

Lastly, as an educator I try and teach my students to be leaders.

Being a Role Model for Students in Need

While teachers are role models for all their students, it can be most important for those who have a rough home life. For the past two years, I’ve worked in districts that have 100% of students on free and reduced breakfast and lunch. A lot of them live in a small, run-down apartment or house with more than five children. Some live with grandparents or spend most of their time with them because their parents are working or not capable of caring for them.

One way to start the year off right and make students feel safe and comfortable in your classroom is to make it feel like a home. Show the students you put time into making your classroom for them! When I set my classroom up each August, I like to make it as homey and inviting as possible. This year, I went with a farmhouse and light blue theme, probably my favorite yet.

I love turning corners of my room into places where students can cuddle up on a beanbag chair with a good book. I want students to know how much I care about their learning environment when they walk in my classroom. Students notice the time you put in, and it helps you start to build that relationship with them from the first day of school.

The next step to building that relationship is to make each student feel like an important part of your class. Getting to know what they like, what sports they play, how many siblings they have, their hobbies and more. There are two easy things I would suggest to any teacher to really connect with their students. The first is I like to show my students I want to know more about them by inviting them to eat lunch with me in the room. I’ll pick two students who are friends and bring them up to the room. They love it. It gives them time to talk your ear off for 30 minutes without being interrupted by anyone or anything else. If you like your lunch quiet to work, then you can use this same concept but instead keep two helpers back during specials. They love to help in the room, and you can chat while doing it.

The second thing is show up to their events. If they play football, go to their games. If they sing in the school choir, go to the concert. If they are in a play, go watch the performance. The look on their face when they see you after will make it worth the time it takes up on your Saturday morning. Whenever I go to my students’ events, it is always the first thing they want to share with the class the next day during circle time. Even the kids who act too cool to say hi after their games will come up to you and say, “Miss Curtis, remember when you came to my football game?” during the last week of school. This shows them that you care about their lives outside of learning in your classroom.

Being a Role Model in Education

One day in class, I asked my students to raise their hand if their parents went to college. Most of them didn’t even know. Being a role model for students can mean many things, and talking about the importance of education is something you can do the first day of school.

Something as simple as hanging a flag of the college you attended by your desk can start the conversation very easily. Students always want to know more about college because, for most of them, it isn’t something talked about at home. I like to share stories about the classes I took in college to become a teacher or the fun things, like making new friends and going to sporting events, to get them thinking about college.

Grow Your Teaching Skills and Career

The fully online teaching degrees at CU cover a wide variety of topics, from associate level to master’s and certificates. As a student in these programs, you’ll learn to become a role model from leaders in the field.

I don’t just try to be a role model for my students; I also like to give students good examples of role models in other career options. It is easy to take a topic you are doing and change it into a career. One I use each year is construction. I decorate the room with construction signs and cones, and I have a friend who is a project manager come in and talk to the students about how he uses math in his architecture drawings every day. The students are always so interested when you bring other people in to talk about what they do.

Another easy theme is a restaurant. You can introduce students to all the different career options such as a chef, a manager or talk about opening your own business. When you do this with older students, you can do things like market day and have students create their own service or product to sell. The more options we talk about for their future, the more students are going to see themselves in one of those positions.

Teaching Students to be Leaders

Building a classroom community can be tough, but it challenges students to be a leader, a team player, patient with others and so much more. One thing I wish I learned more about in my undergrad classes was how to teach students to take ownership of their learning.

To work on that, every day I do a morning circle. Students are asked a question of the day and are able to share. Sometimes, I do a simple getting-to-know-you question, but sometimes, it’s more difficult, such as, “What does it mean to respect others?”

Showing each student that their opinion matters helps them come out of their shell and feel more comfortable sharing. In my classroom, we also do project-based learning where students are work in groups. This is one of my favorite ways to see who steps up to lead.

Group work is not easy for students; it’s always where the most conflict occurs. Students need it to be modeled before they jump in. Teaching students to listen to each other and try ideas that are different from their own is something I try to do often. Giving students roles in group work has been a game changer.

For example, someone is the project manager, and they make sure everyone in the group is doing their job and being heard. Someone is the recorder, and they write down everything that happens for the project. Someone gets to be the person who asks the teacher any questions, which is a huge help so you aren’t having a stampede of questions. Depending on the project, you could implement many more jobs.

Become a Role Model for Students

I have a quote by Nicholas A. Ferroni hanging on the bulletin board by my desk that says, “Students who are loved at home come to school to learn. Students who aren’t loved at home come to school to be loved.”

I keep this quote in mind daily. One of my favorite educators, Kim Bearden, talks about how there is always something going on with our students that we don’t know about. If we as teachers can show them we are here for them and listen to them, it will be one of the greatest examples of a role model they get to see.

I try to come to work every day expecting that it won’t be perfect but that I’ll grow through all the challenges. I try to remember there are always 40 little eyes watching me, and they’ll remember the role I play in their education.

The question is, what are they going to say they remember about you?

Our goal as teachers should always be to empower and inspire our students, and that’s exactly what Campbellsville University believes. Their online teaching degrees cover a wide variety of topics, from associate level to master’s and certificates. As a student in these programs, you’ll learn to become a role model from leaders in the field. The fully online programs were developed by practicing teachers, counselors and principals, ensuring that you receive the best possible education in the field.

This blog post was written by guest contributor Courtney Curtis of Miss Curtis Classroom. Courtney is a third-grade math and science teacher in Cincinnati, Ohio. You can follow her on her on Instagram @misscurtisclassroom .

Ask a Psychologist

Helping students thrive now.

Angela Duckworth and other behavioral-science experts offer advice to teachers based on scientific research. Read more from this blog.

‘Someone Like Me’: The Surprising Power of Role Models

- Share article

This is the last in a three-part series on the legacy of Albert Bandura. Read the first one here and the second one here .

Why do some students set ambitious goals and others don’t?

It’s hard to think you can do something if you haven’t seen someone who looks like you do it. Here’s something I wrote recently about the topic for Character Lab as a Tip of the Week :

“Angela, do you think the United States will elect a female president in your lifetime?”

Years ago, this was the last question of the last interview for a scholarship that, alas, I didn’t win. Reflexively, I frowned and shook my head no.

As the interview ended, I sensed that I’d given an answer the committee found disappointing. “Yes, of course there will be a female president in my lifetime,” they wanted me to say with a confident smile. “And I hope I have your vote.”

Where does the audacity to set ambitious goals and strive for them come from?

A decade before I was born, a young psychologist at Stanford named Al Bandura asked the same question. He randomly assigned preschool children to three groups . One watched adults play aggressively with an inflatable clown called a Bobo doll, another watched adults play quietly with a different toy while ignoring the Bobo doll, and a third had no exposure to these adult role models. Next, each of the children was left alone with the Bobo doll.

The results were striking. Only the children who watched adults play aggressively later imitated what they’d seen. They did so with eerie precision, punching and kicking the Bobo doll, hitting it with a mallet, and sitting on it just as they had seen the adult do.

Like most children, my first role models were in my family. My dad had a Ph.D. in chemistry. Most of my uncles—and countless cousins—were doctors or scientists. So if you’d asked me in, say, 3rd grade, “Angela, could you become a college professor someday, if you tried?” Without a shred of evidence that I’d be any good at such a career, I’d have nodded my head. “Sure. Why not?”

If, instead, you’d asked me, “Angela, do you think you could become an Olympic swimmer, if you tried?” I would have shaken my head. After all, nobody in my family was a professional athlete, and for the most part, the athletes on television didn’t look like me.

In the Bobo doll study, trends in the data suggest that boys were more likely to imitate the behavior of men, and girls were more likely to imitate the behavior of women. Likewise, in a more recent study , college students who were assigned to teaching assistants of similar race or ethnicity were more likely to attend office hours and discussion sections. This match also led to improved student performance in sequenced courses and positively influenced decisions on college majors.

Don’t assume that children know they can be anything they want when they grow up.

Do go out of your way to expose the young people in your life to inspiring role models they can relate to, whether it’s an Olympic athlete or a local entrepreneur. And now that we have our first female vice president, can the first female president be far behind?

The opinions expressed in Ask a Psychologist: Helping Students Thrive Now are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- LOGIN & Help

Which role models are effective for which students? A systematic review and four recommendations for maximizing the effectiveness of role models in STEM

Research output : Contribution to journal › Review article › peer-review

Is exposing students to role models an effective tool for diversifying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)? So far, the evidence for this claim is mixed. Here, we set out to identify systematic sources of variability in STEM role models’ effects on student motivation: If we determine which role models are effective for which students, we will be in a better position to maximize role models’ impact as a tool for diversifying STEM. A systematic narrative review of the literature (55 articles) investigated the effects of role models on students’ STEM motivation as a function of several key features of the role models (their perceived competence, their perceived similarity to students, and the perceived attainability of their success) and the students (their gender, race/ethnicity, age, and identification with STEM). We conclude with four concrete recommendations for ensuring that STEM role models are motivating for students of all backgrounds and demographics—an important step toward diversifying STEM.

| Original language | English (US) |

|---|---|

| Article number | 59 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 8 |

| Issue number | 1 |

| DOIs | |

| State | Published - Dec 2021 |

| Externally published | Yes |

- Role models

ASJC Scopus subject areas

Online availability.

- 10.1186/s40594-021-00315-x

Library availability

Related links.

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Role Models Keyphrases 100%

- Model of Science Keyphrases 100%

- Role Model Social Sciences 100%

- Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Social Sciences 100%

- Systematic Review Social Sciences 100%

- Narrative Review Psychology 100%

- Race-ethnicity Keyphrases 12%

- Effective Tool Keyphrases 12%

T1 - Which role models are effective for which students? A systematic review and four recommendations for maximizing the effectiveness of role models in STEM

AU - Gladstone, Jessica R.

AU - Cimpian, Andrei

N1 - Funding Information: We thank Tanner LeBaron Wallace, Shanette Porter, Allan Wigfield, the other Inclusive Mathematics Environments Fellows, and the members of the Cognitive Development Lab at New York University for insightful feedback on this work. We also thank Gabrielle Applebaum and Theodora Simons for their assistance with screening the manuscripts and synthesizing the evidence. Funding Information: This work was supported by an Inclusive Mathematics Environments Early Career Fellowship from the Mindset Scholars Network, with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to JRG. The funder played no part in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Publisher Copyright: © 2021, The Author(s).

PY - 2021/12

Y1 - 2021/12

N2 - Is exposing students to role models an effective tool for diversifying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)? So far, the evidence for this claim is mixed. Here, we set out to identify systematic sources of variability in STEM role models’ effects on student motivation: If we determine which role models are effective for which students, we will be in a better position to maximize role models’ impact as a tool for diversifying STEM. A systematic narrative review of the literature (55 articles) investigated the effects of role models on students’ STEM motivation as a function of several key features of the role models (their perceived competence, their perceived similarity to students, and the perceived attainability of their success) and the students (their gender, race/ethnicity, age, and identification with STEM). We conclude with four concrete recommendations for ensuring that STEM role models are motivating for students of all backgrounds and demographics—an important step toward diversifying STEM.

AB - Is exposing students to role models an effective tool for diversifying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)? So far, the evidence for this claim is mixed. Here, we set out to identify systematic sources of variability in STEM role models’ effects on student motivation: If we determine which role models are effective for which students, we will be in a better position to maximize role models’ impact as a tool for diversifying STEM. A systematic narrative review of the literature (55 articles) investigated the effects of role models on students’ STEM motivation as a function of several key features of the role models (their perceived competence, their perceived similarity to students, and the perceived attainability of their success) and the students (their gender, race/ethnicity, age, and identification with STEM). We conclude with four concrete recommendations for ensuring that STEM role models are motivating for students of all backgrounds and demographics—an important step toward diversifying STEM.

KW - Diversity

KW - Motivation

KW - Role models

KW - Science

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85120748159&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85120748159&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1186/s40594-021-00315-x

DO - 10.1186/s40594-021-00315-x

M3 - Review article

AN - SCOPUS:85120748159

SN - 2196-7822

JO - International Journal of STEM Education

JF - International Journal of STEM Education

Teachers as Role Models

Cite this chapter.

- Wayne Martino 3

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE,volume 21))

13k Accesses

7 Citations

In this chapter I focus on the discourse of teachers as role models to highlight the conceptual limits of such an explanatory framework for making sense of teachers' lives and their impact on student learning in schools. I stress that the issues sur rounding the call for role models in terms of recruiting more minority and male teachers in schools cannot be treated solely as a representational problem which can be addressed simply by striking the appropriate gender and ethnic balance in the teaching profession (see Latham, 1999). In fact, my argument is that the role model discourse is particularly seductive because it recycles familiar stereotypes about gen der and minorities with the effect of eliding complex issues of identity management and conflict in teachers' lives (see Britzman, 1993; Button, 2007; Griffin, 1991; Martino, in press). Moreover, claims about the potential influence of teachers, on the basis of their gender and/or ethnicity, have not been substantiated in the empiri cal literature. By reviewing significant research in the field, I demonstrate that the familiar tendency to establish a necessary correlation between improved learning and pedagogical outcomes, as a consequence of matching teachers and students on the basis of their gender and/or ethnic backgrounds, cannot be empirically substantiated.

In this sense, my aim is to provide a more informed research based knowledge and analytic framework capable of interrogating the conceptual limits of the role model discourse, particularly as it relates to establishing the potential influence of teachers on students' lives in schools. In addition, in the second part of the chapter I draw attention to the persistence of the role model discourse as a particular gendered phenomenon within the context of the call for male teachers in elementary schools to address the educational and social needs of boys. This discussion is used as a further basis for interrogating the fallacious assumptions informing the teacher role model discourse which has been invoked in response to a moral panic surrounding the crisis of masculinity vis-à-vis the perceived threat of the increasing feminization of elementary schooling (see Lingard & Douglas, 1999; Martino, 2008). In this way, I foreground the extent to which the role model argument has been used to sup port the need for both a gender balanced and a more ethnically and racially diverse teaching profession, while eschewing important political issues pertaining to: (1) the devalued status of doing women's work (Williams, 1993); (2) the significance of teaching for men's sense of their own masculinity and sexuality (Francis & Skelton, 2001; Martino & Kehler, 2006) and; (3) the impact of the social dynamics of racism and sexism on minority teachers' lives (Carrington, 2002; Ehrenberg, Goldhaber, & Brewer, 1995; Pole, 1999).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Limits of Role Modelling as a Policy Frame for Addressing Equity Issues in the Teaching Profession

The Role of Self-Study in Teaching and Teacher Education for Social Justice

Allan, J. (1994). Anomaly as exemplar: The meanings of role-modeling for men elementary teachers . Tri-College Department of Education, Loras College, Iowa.

Google Scholar

Allen, A. (2000). The role model argument and faculty diversity. Available at http://www.onlineethics.org/ CMS/workplace/workplacediv/abstractsindex/fac-diverse.aspx .

Ashley, M. (2003). Primary school boys’ identity formation and the male role model: An exploration of sexual identity and gender identity in the UK through attachment theory. Sex Education , 3 (3), 257–270.

Britzman, D. (1993). Beyond rolling models: Gender and multicultural education. In: S. K. Biklen & D. Pollard (Eds.), Gender and education (pp. 25–42). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Button, L. (2007). Gendered discourses surrounding elementary school teachers. PhD Thesis, OISE, The University of Toronto.

Carrington, B., & Skelton, C. (2003). Re-thinking role models: equal opportunities in teacher recruitment in England and Wales. Journal of Educational Policy , 18 (3), 253–265.

Article Google Scholar

Carrington, B. (2002). Ethnicity, ‘role models’ and teaching. Journal of Research in Education , 12 (1), 40–49.

Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities . Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Coulter, R., & McNay, M. (1993). Exploring men's experiences as elementary school teachers. Canadian Journal of Education , 18 (4), 398–413.

Davis, J. (2006). Research at the margin: Mapping masculinity and mobility of African-American high school dropouts. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education , 19 (3), 289–304.

Drudy, S., Martin, M., Woods, M., & O'Flynn, J. (2005). Men and the classroom: Gender imbalances in teaching . London and New York: Routledge.

Editorial. (2007, July 31) The absence of fathers. The Globe and Mail , p. A12.

Ehrenberg, R., Goldhaber, D., & Brewer, D. (1995). Do teachers' race, gender and ethnicity matter? Indus trial and Labor Relations Review , 48 (3), 547–561.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against women . London: Vintage.

Foster, T., & Newman, E. (2005). Just a knock back? Identity bruising on the route to becoming a male primary school teacher. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice , 11 (4), 341–358.

Francis, B., & Skelton, C. (2001). Men teachers and the construction of heterosexual masculinity in the classroom. Sex Education , 1 (1), 9–21.

Gold, D., & Reis, M. (1982). Male teacher effects on young children: A theoretical and empirical consid eration. Sex Roles , 8 , 493–513.

Griffin, P. (1991). Identity management strategies among lesbian and gay educators. Qualitative Studies in Education , 4 (3), 189–202.

Hoff Sommers, C. (2000, May). The War against boys. The Atlantic Monthly . Available at http://www. theatlantic.com/issues/2000/05/sommers2.htm.

hooks, B. (2004). We real cool: Black men and masculinity . New York and London: Routledge.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Training. (2002). Boys' Education: Get ting it Right . Canberra: Commonwealth Government of Australia.

King, J. (1998). Uncommon caring: Learning from men who teach young children . New York: Teachers College Press.

King, J. (2004). The (im)possibility of gay teachers for young children. Theory into Practice , 43 (2), 122–127.

Kumashiro, K. (Ed.). (2001). Troubling intersections of race and sexuality . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kunjufu, J. (2005). Countering the conspiracy to destroy black boys . Chicago: African American images.

Lahelma, E. (2000). Lack of male teachers: a problem for students or teachers? Pedagogy, Culture and Society , 8 (2), 173–186.

Lam, C. (1996). The green teacher. In D. Thiessen, N. Bascia, I. Goodson (Eds.), Making a difference about difference: The lives and careers of racial minority immigrant teachers (pp. 15–50). Toronto: Garamond Press.

Latham, A, (1999). The teacher-student mismatch. Educational Leadership 56. Available at http://www.nea.org/teachexperience/divk040506.html.

Lingard, B. (2003). Where to in gender theorizing and policy after recuperative masculinity politics? International Journal of Inclusive Education , 7 (1), 33–56.

Lingard, B., & Douglas, P. (1999). Men engaging feminisms: Profeminism, backlashes and schooling . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lingard, B., Martino, W., Mills, M., & Bahr, M. (2002). Addressing the educational needs of boys . Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training, http://www.dest.gov.au/schools/publica-tions/2002/boyseducation/index.htm

Lingard, B., Martino, W., & Mills, M. (in press). Boys and school: Beyond structural reform . London, Palgrave.

Martino, W. (2008). Male teachers as role models: Addressing issues of masculinity, pedagogy and the re-masculinization of schooling. Curriculum Inquiry , 38 (2), 189–223.

Martino, W. (in press). ‘The lure of hegemonic masculinity’: Investigating the dynamics of gender relations in two male elementary school teachers' lives. The International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education .

Martino, W., & Berrill, D. (2003). Boys, schooling and masculinities: Interrogating the ‘Right’ way to education boys. Education Review , 55 (2), 99–117.

Martino, W., & Berrill, D. (2007). Dangerous pedagogies: Addressing issues of sexuality, masculinity and schooling with male pre-service teacher education students. In K. Davison & B. Frank (Eds.), Masculinity and schooling: International practices and perspectives (pp. 13–34). Althouse Press: The University of Western Ontario, London.

Martino, W., & Frank, B. (2006). The tyranny of surveillance: Male teachers and the policing of masculini ties in a single sex school. Gender & Education , 18 (1), 17–33.

Martino, W., & Kehler, M. (2006). Male teachers and the ‘boy problem’: An issue of recuperative mascu linity politics. McGill Journal of Education , 41 (2), 1–19.

Martino, W., & Pallotta-Chiarolli, M. (2003). So what's a boy? Addressing issues of masculinity and schooling . Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Mills, M., Martino, W., & Lingard, B. (2007). Getting boys' education ‘right’: The Australian Govern ment's Parliamentary Inquiry Report as an exemplary instance of recuperative masculinity politics. British Journal of Sociology of Education , 28 (1), 5–21.

Mills, M., Martino, W., & Lingard, B. (2004). Issues in the male teacher debate: Masculinities, misogyny and homophobia. The British Journal of the Sociology of Education , 25 (3), 355–369.

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education . New York: Teachers College Press.

Ontario College of Teachers. (2004). Narrowing the gender gap: Attracting men to teaching. Report, Ontario, Canada. Available at http://www.oct.ca/publications/documents.aspx?lang=en-CA

Pepperell, S., & Smedley S. (1998). Call for more men in primary teaching: Problematizing the issues. International Journal of Inclusive Education , 2 (4), 341–357.

Pole, C. (1999). Black teachers giving voice: Choosing and experiencing teaching. Teacher Development , 3 (3), 313–328.

Quiocho, A., & Rios, F. (2000). The power of their presence: Minority group teachers and schooling. Review of Educational Research , 70 , 485–528.

Rowan, L., Knobel, M., Bigum, C., & Lankshear, C. (2002). Boys, literacies and schooling: The dangerous territories of gender-based literacy reform. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Roulston, K., & Mills, M. (2000). Male teachers in feminised teaching areas: Marching to the men's move ment drums. Oxford Review of Education , 26 (1), 221–237.

Sargent, P. (2005). The gendering of men in early childhood education. Sex Roles , 52 (3/4), 251–259.

Skelton, C. (2002). The feminisation of schooling or re-masculinising primary education? International Studies in Sociology of Education , 12 (1), 77–96.

Skelton, C. (2003). Male primary teachers and perceptions of masculinity. Education Review , 55 (2), 195–210.

Skelton, C. (2001). Schooling the boys: Masculinities and primary education . Buckingham: Open Uni versity Press.

Segal, L. (1990). Slow motion, changing masculinities, changing men . London: Virago Press.

Thiessen, D., Bascia, N., & Goodson, I. (1996). Making a difference about difference: The lives and careers of racial minority immigrant teachers . Toronto: Garamond Press.

Williams, C. (1993). Doing “women's work”: men in nontraditional occupations . Newbury Park, London & New Delhi: Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, N6G 1G7, Canada

Wayne Martino

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

Lawrence J. Saha

University of Houston, Houston, USA

A. Gary Dworkin

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Martino, W. (2009). Teachers as Role Models. In: Saha, L.J., Dworkin, A.G. (eds) International Handbook of Research on Teachers and Teaching. Springer International Handbooks of Education, vol 21. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73317-3_47

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73317-3_47

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-73316-6

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-73317-3

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- mrsstrickey

- Sep 14, 2021

Teachers as Role Models

Updated: Nov 9, 2021

The Early Career Framework states that teachers must learn that... Teachers are key role models, who can influence the attitudes, values and behaviours of their pupils.

A role model is a person whose behaviour, example, or success is or can be emulated by others, especially by younger people. The term role model is credited to sociologist Robert K. Merton, who coined the phrase during his career. Merton hypothesized that individuals compare themselves with reference groups of people who occupy the social role to which the individual aspires. An example being the way young fans will idolize and imitate professional athletes or entertainment artists.

True role models are those who possess the qualities that we would like to have, and those who have affected us in a way that makes us want to be better people. They help us to advocate for ourselves and take a leadership position on the issues that we believe in.

Role models show young people how to live with integrity, optimism, hope, determination, and compassion. They play an essential part in a child’s positive development.

Teachers are key role models, who can influence the attitudes, values and behaviours of their pupils. A positive role model serves as an example–inspiring children to live meaningful lives. Teachers are a constant presence in a child's life. They influence children as much as—if not even more than—parents do. Over the years, I've seen the tremendous impact teachers have had on their students. They're not just educators; they're role models who inspire and motivate children outside the classroom as much as they impart knowledge inside it.

Role models are people who influence others by serving as examples. They are often admired by the people who emulate them. Through their perceived personal qualities, behaviours, or achievements, they can inspire others to strive and develop without providing any direct instruction. Social scientists have shown that much of learning that occurs during childhood is acquired through observation and imitation. For most children, the most important role models are their parents and caregivers, who have a regular presence in their lives. After these, it is their teachers. Teachers follow students through each pivotal stage of development. At six to eight hours a day, five days a week, you as a teacher are poised to become one of the most influential people in your students’ life. After their parents, children will first learn from you, their primary school teacher. Then, as a middle school teacher, you will guide students through yet another important transition: adolescence. As children become young adults, learning throughout middle school and into high school, you will answer their questions, listen to their problems and teach them about this new phase of their lives. You not only watch your students grow you help them grow.

As a teacher, it is impossible to not model. Your students will see your example – positive or negative – as a pattern for the way life is to be lived.

According to David Streight, executive director of the Council for Spiritual and Ethical Education and a nationally certified school psychologist, we know the following about good role models for children:

The way you act and the kind of model you offer your students constitutes one of the five well-researched practices proven to maximize the chances your students will grow up with good consciences and well-developed moral reasoning skills.

The right kind of modelling can influence how much empathy your students will end up feeling and showing in later life.

The chances of your students growing up to be altruistic – to be willing to act for the benefit of others, even when there are no tangible rewards involved – are better depending on the kinds of role models children grow up with.

Good role models can make lifelong impressions on children, regarding how to act in the difficult situations that they will inevitably face in life.

Role modelling is a powerful teaching tool for passing on the knowledge, skills, and values of the medical profession, but its net effect on the behaviour of students is often negative rather than positive

“ We must acknowledge . . . that the most important, indeed the only, thing we have to offer our students is ourselves. Everything else they can read in a book.” – D C Tosteson

Role models differ from mentors. Role models inspire and teach by example, often while they are doing other things. Mentors have an explicit relationship with a student over time, and they more often direct the student by asking questions and giving advice freely.

Ducharme (1993), Guilfoyle, Hamilton, Placier, and Pinnegar (1995), as well as Regenspan (2002), remind us of the complex dual role of teacher educators. Korthagen, Loughran, and Lunenberg (2005) elaborate on this when they say:

Teacher educators not only have the role of supporting student teachers’ learning about teaching, but in so doing, through their own teaching, model the role of the teacher. In this respect, the teacher education profession is unique, differing from, say, doctors who teach medicine. During their teaching, doctors do not serve as role models for the actual practice of the profession i.e., they do not treat their students. Teacher educators, conversely, whether intentionally or not, teach their students as well as teach about teaching

Being a positive role model requires effort, fore-thought, and self-control for most teachers. Because your students are watching you all the time, your actions, beliefs, and attitudes become integrated into your students’ way of being; therefore, it is very important that you be very intentional about what behaviours you model for your students.

Unfortunately for teachers, the saying “Do as I say, not as I do” simply does not work. Students can sniff out hypocrisy like a blood hound, and they gain the most from teachers who demonstrate consistency between their actions and their values by “walking the talk.”

Students respect adults who live by the rules they preach. Hypocrisy disillusions students and sends them looking for alternative role models to follow.

Model through your own actions. For example, consider how you:

handle stress and frustration

respond to problems

express anger and other emotions

treat other people

deal with competition, responsibilities, loss, mistakes

celebrate special occasions