How to Use a Conceptual Framework for Better Research

A conceptual framework in research is not just a tool but a vital roadmap that guides the entire research process. It integrates various theories, assumptions, and beliefs to provide a structured approach to research. By defining a conceptual framework, researchers can focus their inquiries and clarify their hypotheses, leading to more effective and meaningful research outcomes.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework is essentially an analytical tool that combines concepts and sets them within an appropriate theoretical structure. It serves as a lens through which researchers view the complexities of the real world. The importance of a conceptual framework lies in its ability to serve as a guide, helping researchers to not only visualize but also systematically approach their study.

Key Components and to be Analyzed During Research

- Theories: These are the underlying principles that guide the hypotheses and assumptions of the research.

- Assumptions: These are the accepted truths that are not tested within the scope of the research but are essential for framing the study.

- Beliefs: These often reflect the subjective viewpoints that may influence the interpretation of data.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Together, these components help to define the conceptual framework that directs the research towards its ultimate goal. This structured approach not only improves clarity but also enhances the validity and reliability of the research outcomes. By using a conceptual framework, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and focus on essential variables and relationships.

For practical examples and to see how different frameworks can be applied in various research scenarios, you can Explore Conceptual Framework Examples .

Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks Used in Research

Understanding the various types of conceptual frameworks is crucial for researchers aiming to align their studies with the most effective structure. Conceptual frameworks in research vary primarily between theoretical and operational frameworks, each serving distinct purposes and suiting different research methodologies.

Theoretical vs Operational Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are built upon existing theories and literature, providing a broad and abstract understanding of the research topic. They help in forming the basis of the study by linking the research to already established scholarly works. On the other hand, operational frameworks are more practical, focusing on how the study’s theories will be tested through specific procedures and variables.

- Theoretical frameworks are ideal for exploratory studies and can help in understanding complex phenomena.

- Operational frameworks suit studies requiring precise measurement and data analysis.

Choosing the Right Framework

Selecting the appropriate conceptual framework is pivotal for the success of a research project. It involves matching the research questions with the framework that best addresses the methodological needs of the study. For instance, a theoretical framework might be chosen for studies that aim to generate new theories, while an operational framework would be better suited for testing specific hypotheses.

Benefits of choosing the right framework include enhanced clarity, better alignment with research goals, and improved validity of research outcomes. Tools like Table Chart Maker can be instrumental in visually comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different frameworks, aiding in this crucial decision-making process.

Real-World Examples of Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Understanding the practical application of conceptual frameworks in research can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your studies. Here, we explore several real-world case studies that demonstrate the pivotal role of conceptual frameworks in achieving robust research conclusions.

- Healthcare Research: In a study examining the impact of lifestyle choices on chronic diseases, researchers used a conceptual framework to link dietary habits, exercise, and genetic predispositions. This framework helped in identifying key variables and their interrelations, leading to more targeted interventions.

- Educational Development: Educational theorists often employ conceptual frameworks to explore the dynamics between teaching methods and student learning outcomes. One notable study mapped out the influences of digital tools on learning engagement, providing insights that shaped educational policies.

- Environmental Policy: Conceptual frameworks have been crucial in environmental research, particularly in studies on climate change adaptation. By framing the relationships between human activity, ecological changes, and policy responses, researchers have been able to propose more effective sustainability strategies.

Adapting conceptual frameworks based on evolving research data is also critical. As new information becomes available, it’s essential to revisit and adjust the framework to maintain its relevance and accuracy, ensuring that the research remains aligned with real-world conditions.

For those looking to visualize and better comprehend their research frameworks, Graphic Organizers for Conceptual Frameworks can be an invaluable tool. These organizers help in structuring and presenting research findings clearly, enhancing both the process and the presentation of your research.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Own Conceptual Framework

Creating a conceptual framework is a critical step in structuring your research to ensure clarity and focus. This guide will walk you through the process of building a robust framework, from identifying key concepts to refining your approach as your research evolves.

Building Blocks of a Conceptual Framework

- Identify and Define Main Concepts and Variables: Start by clearly identifying the main concepts, variables, and their relationships that will form the basis of your research. This could include defining key terms and establishing the scope of your study.

- Develop a Hypothesis or Primary Research Question: Formulate a central hypothesis or question that guides the direction of your research. This will serve as the foundation upon which your conceptual framework is built.

- Link Theories and Concepts Logically: Connect your identified concepts and variables with existing theories to create a coherent structure. This logical linking helps in forming a strong theoretical base for your research.

Visualizing and Refining Your Framework

Using visual tools can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your conceptual framework. Decision Tree Templates for Conceptual Frameworks can be particularly useful in mapping out the relationships between variables and hypotheses.

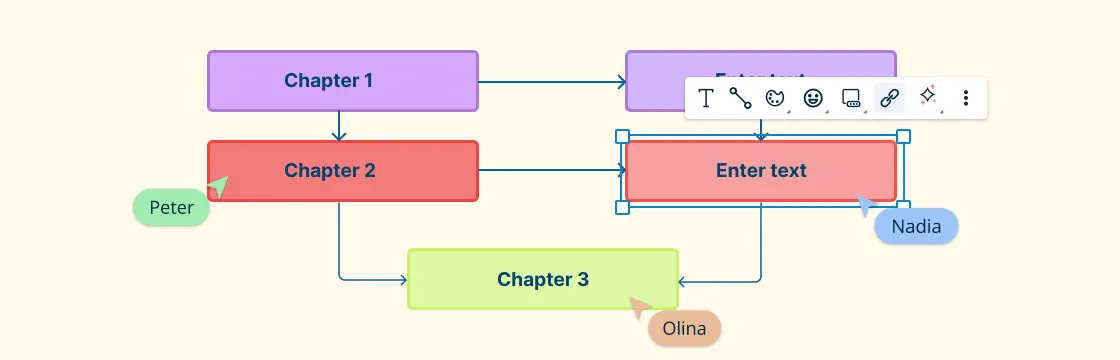

Map Your Framework: Utilize tools like Creately’s visual canvas to diagram your framework. This visual representation helps in identifying gaps or overlaps in your framework and provides a clear overview of your research structure.

Analyze and Refine: As your research progresses, continuously evaluate and refine your framework. Adjustments may be necessary as new data comes to light or as initial assumptions are challenged.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your conceptual framework is not only well-defined but also adaptable to the changing dynamics of your research.

Practical Tips for Utilizing Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Effectively utilizing a conceptual framework in research not only streamlines the process but also enhances the clarity and coherence of your findings. Here are some practical tips to maximize the use of conceptual frameworks in your research endeavors.

- Setting Clear Research Goals: Begin by defining precise objectives that are aligned with your research questions. This clarity will guide your entire research process, ensuring that every step you take is purposeful and directly contributes to your overall study aims. \

- Maintaining Focus and Coherence: Throughout the research, consistently refer back to your conceptual framework to maintain focus. This will help in keeping your research aligned with the initial goals and prevent deviations that could dilute the effectiveness of your findings.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Use your conceptual framework as a lens through which to view and interpret data. This approach ensures that the data analysis is not only systematic but also meaningful in the context of your research objectives. For more insights, explore Research Data Analysis Methods .

- Presenting Research Findings: When it comes time to present your findings, structure your presentation around the conceptual framework . This will help your audience understand the logical flow of your research and how each part contributes to the whole.

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls: Be vigilant about common errors such as overcomplicating the framework or misaligning the research methods with the framework’s structure. Keeping it simple and aligned ensures that the framework effectively supports your research.

By adhering to these tips and utilizing tools like 7 Essential Visual Tools for Social Work Assessment , researchers can ensure that their conceptual frameworks are not only robust but also practically applicable in their studies.

How Creately Enhances the Creation and Use of Conceptual Frameworks

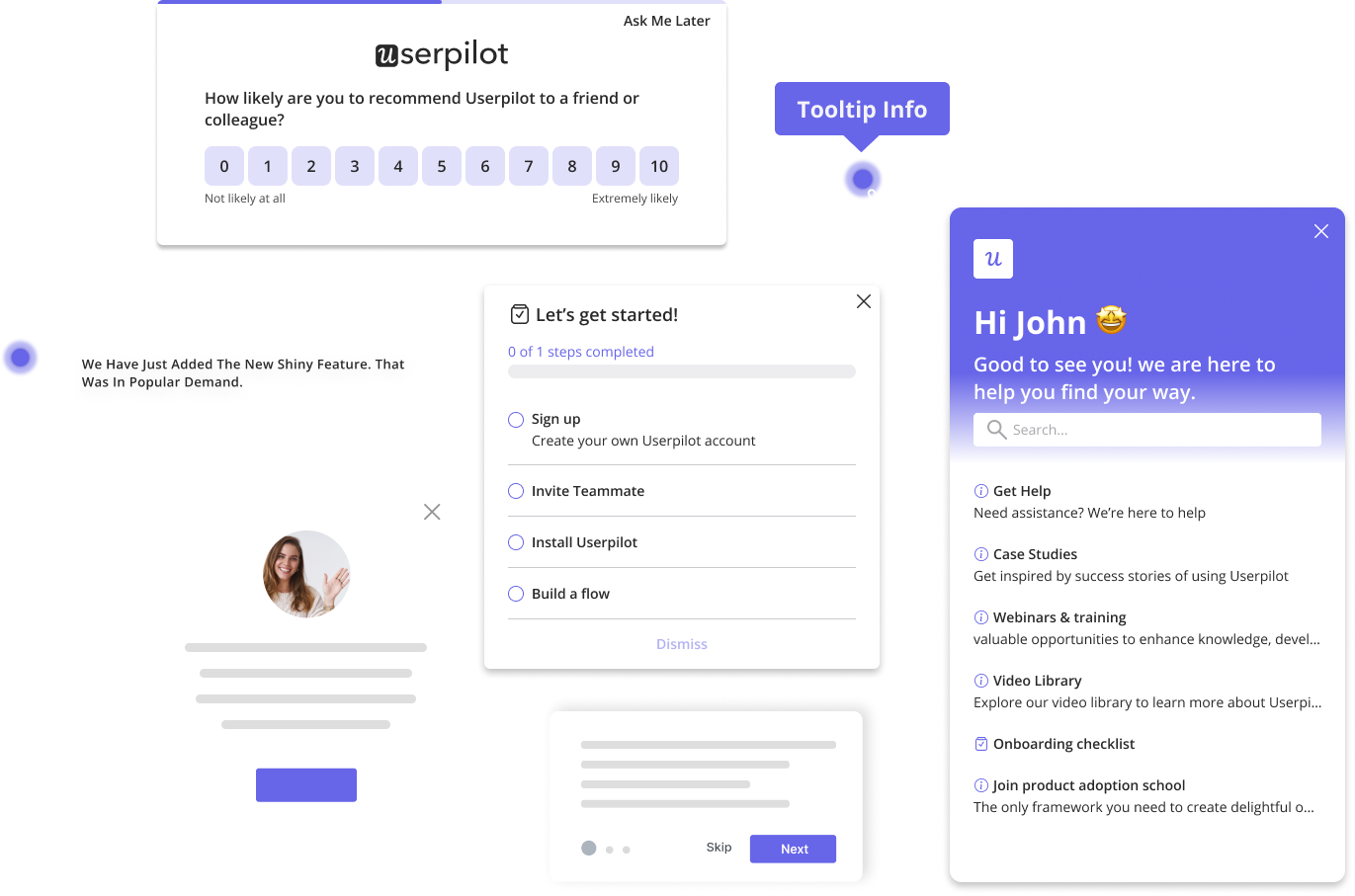

Creating a robust conceptual framework is pivotal for effective research, and Creately’s suite of visual tools offers unparalleled support in this endeavor. By leveraging Creately’s features, researchers can visualize, organize, and analyze their research frameworks more efficiently.

- Visual Mapping of Research Plans: Creately’s infinite visual canvas allows researchers to map out their entire research plan visually. This helps in understanding the complex relationships between different research variables and theories, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of the research process.

- Brainstorming with Mind Maps: Using Mind Mapping Software , researchers can generate and organize ideas dynamically. Creately’s intelligent formatting helps in brainstorming sessions, making it easier to explore multiple topics or delve deeply into specific concepts.

- Centralized Data Management: Creately enables the importation of data from multiple sources, which can be integrated into the visual research framework. This centralization aids in maintaining a cohesive and comprehensive overview of all research elements, ensuring that no critical information is overlooked.

- Communication and Collaboration: The platform supports real-time collaboration, allowing teams to work together seamlessly, regardless of their physical location. This feature is crucial for research teams spread across different geographies, facilitating effective communication and iterative feedback throughout the research process.

Moreover, the ability t Explore Conceptual Framework Examples directly within Creately inspires researchers by providing practical templates and examples that can be customized to suit specific research needs. This not only saves time but also enhances the quality of the conceptual framework developed.

In conclusion, Creately’s tools for creating and managing conceptual frameworks are indispensable for researchers aiming to achieve clear, structured, and impactful research outcomes.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Chiraag George is a communication specialist here at Creately. He is a marketing junkie that is fascinated by how brands occupy consumer mind space. A lover of all things tech, he writes a lot about the intersection of technology, branding and culture at large.

Mastering Research Frameworks: 8 Step-by-Step Guide To A Success Academic Writing!

Introduction.

Research is a fundamental aspect of any academic or scientific endeavor. It involves the systematic investigation of a particular topic or problem to generate new knowledge or validate existing theories. However, conducting research can be a complex and challenging process, requiring careful planning and organization. This is where research frameworks come into play.

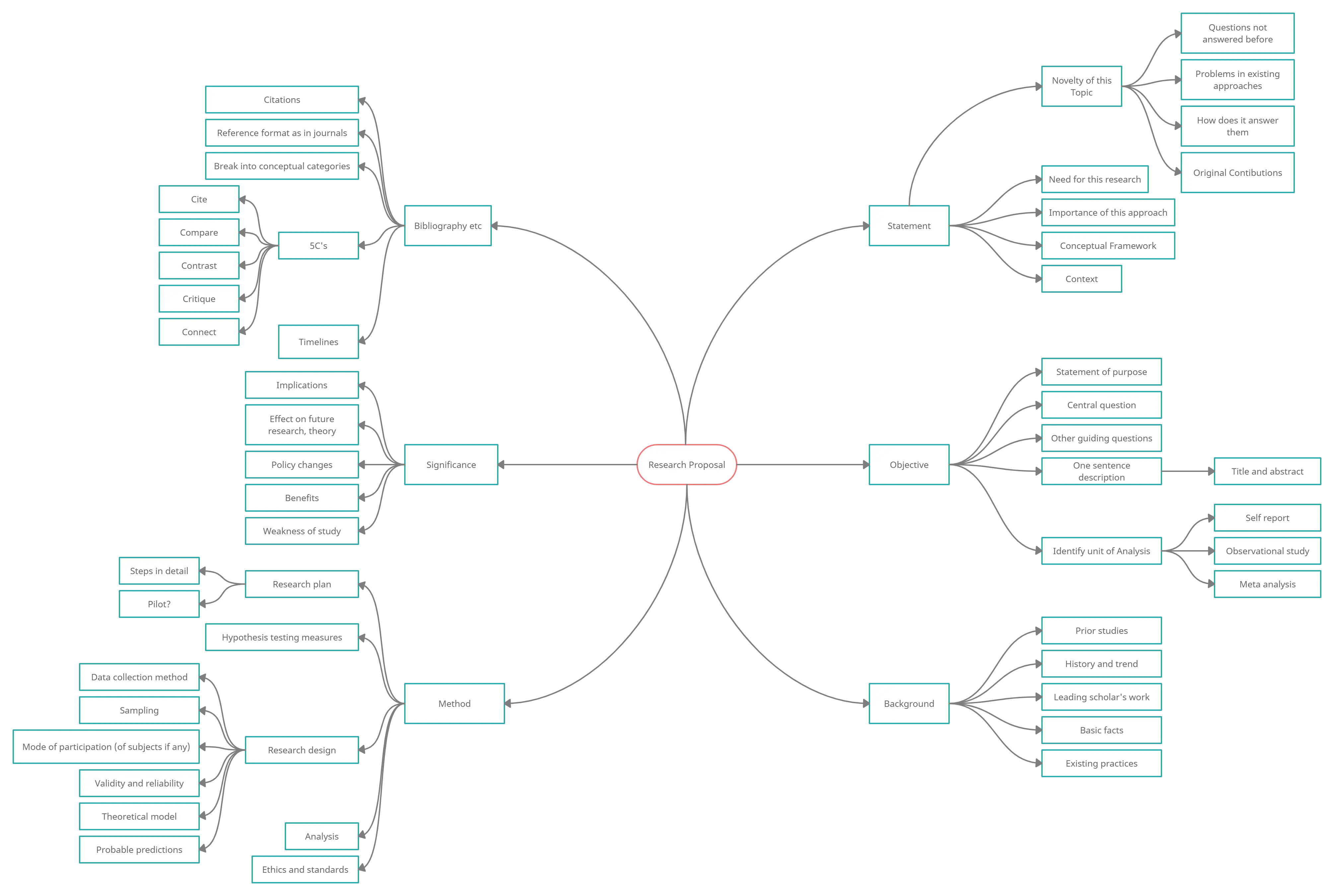

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the concept of research frameworks and how they can help researchers in their work. We will discuss the components of a research framework, the different types of frameworks, and the methodology behind developing and implementing a research framework. Additionally, we will provide examples of research frameworks as samples to guide researchers in designing their own projects. For researchers looking to collaborate and enhance their research framework strategies, platforms like Researchmate.net offer valuable resources and networking opportunities.

What is a Research Framework?

A research framework refers to the overall structure, approach, and theoretical underpinnings that guide a research study. It is a systematic and organized plan that outlines the key elements of a research project, including the research questions, objectives, methodology, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

A research framework provides researchers with a roadmap to follow throughout the research process, ensuring that the study is conducted in a logical and coherent manner. It helps researchers to organize their thoughts, identify gaps in existing knowledge, and develop a clear research plan. By establishing a research framework, researchers can ensure that their study is rigorous, valid, and reliable, and that it contributes to the existing body of knowledge in their field. Overall, a research framework serves as a foundation for the research study, guiding the researcher in every step of the research process.

Components of a Research Framework

A research framework consists of several key components that work together to guide the research process. It is essentially a structured outline that serves as a guide for researchers to organize their thoughts, define research objectives, and plan the research process comprehensively. While there are various research framework templates available, they typically include the following components:

Problem Statement

The problem statement defines the research problem or question that the study aims to address. It provides a clear and concise statement of the issue that needs to be investigated. This often emerges from identifying a research gap in the existing literature, highlighting areas that lack sufficient study or have not been explored at all.

The research objectives outline the specific goals and outcomes that the study aims to achieve. These objectives help to focus the research and provide a clear direction for the study. The objectives should be measurable and aligned with the research question to ensure that the study is targeted and relevant.

Literature Review

The literature review is a critical component of a research framework. It involves reviewing existing research and literature related to the research topic. This helps to identify gaps in the current knowledge and provides a foundation for the study.

Theoretical or Conceptual Framework

The phrases ‘ conceptual framework ‘ and ‘ theoretical framework ‘ are often used to describe the overall structure that defines and outlines a research project. These frameworks are composed of theories, concepts, and models that serve as the foundation and guide for the research process.

Methodology

The research methodology outlines the methods and techniques that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes details on the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

Data Collection

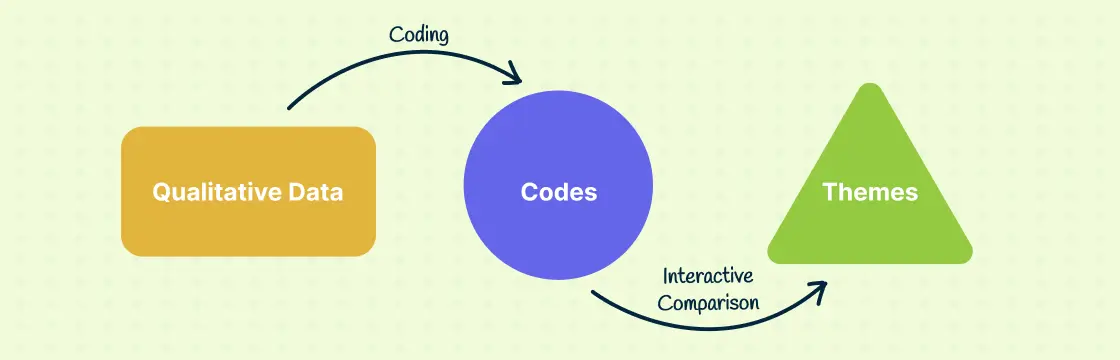

Data collection method is a component of research methodology which involves collecting data from various sources, such as surveys, interviews , observations, or existing datasets. The data collected should be relevant to the research objectives and provide insights into the research problem.

Data Analysis

Data analysis involves organizing, interpreting, and analyzing the collected data. This can include statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a combination of both, depending on the research objectives and data collected.

Findings and Conclusion

The findings and conclusion section presents the results of the data analysis and discusses the implications of the findings. It summarizes the key findings, draws conclusions, and provides recommendations for future research or practical applications. It highlights the contribution of the study to the existing body of knowledge and suggests areas for further investigation.

These components work together to provide a comprehensive framework for conducting research. Each component plays a crucial role in guiding the research process and ensuring that the study is rigorous and valid.

Types of Research Frameworks

There are two types of research frameworks: theoretical and conceptual.

A theoretical framework is a single formal theory that is used as the basis for a study. It provides a set of concepts and principles that guide the research process. On the other hand, a conceptual framework is a broader framework that includes multiple concepts and theories. It provides a unified framework for understanding and analyzing a particular research problem. The two types of frameworks relate differently to the research question and design. The theoretical framework often inspires the research question based on the existing theory, while the conceptual framework helps in organizing and structuring the research process.

Both types of frameworks have their advantages and limitations. A theoretical framework provides a solid foundation for research and allows for the testing of specific hypotheses. However, it may be limited in its applicability to a specific research problem. On the other hand, a conceptual framework allows for a more holistic and comprehensive understanding of the research problem. It provides a framework for exploring multiple perspectives and theories. However, it may lack the specificity and precision of a theoretical framework.

In practice, researchers often use a combination of theoretical and conceptual frameworks to guide their research. They may start with a theoretical framework to establish a foundation and then use a conceptual framework to explore and analyze the research problem from different angles. The choice of research framework depends on the nature of the research problem, the research question, and the goals of the study. Researchers should carefully consider the advantages and limitations of each type of framework and select the most appropriate one for their specific research context.

Research Framework Methodology

Methodology is an essential component of a research framework as it provides a structured approach to conducting research projects. The methodology section of a research framework includes the research design, sampling design, data collection techniques, analysis, and interpretation of the data. These elements are crucial in ensuring the validity and reliability of the research finding as follows:

- The research design refers to the overall plan or strategy that researchers adopt to answer their research questions. It includes decisions about the type of research, the research approach, and the research paradigm. The research design provides a roadmap for the entire research process.

- Sampling design is another important aspect of the methodology. It involves selecting a representative sample from the target population. The sample should be chosen in such a way that it accurately represents the characteristics of the population and allows for generalization of the findings.

- Data collection techniques are the methods used to gather data for the research. These can include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or the analysis of existing data. The choice of data collection techniques depends on the research questions and the nature of the data being collected. Once the data is collected, it needs to be analyzed and interpreted. This involves organizing and summarizing the data, identifying patterns and trends, and drawing conclusions based on the findings.

- The analysis and interpretation of data are crucial in generating meaningful insights and answering the research questions.

Research Framework Examples

Example 1: Tourism Research Framework

One example of a research framework is a tourism research framework. This framework includes various components such as tourism systems and development models, the political economy and political ecology of tourism, and community involvement in tourism. By using this framework, researchers can analyze and understand the complex dynamics of tourism and its impact on communities and the environment.

Example 2: Educational Research Framework

Another example of a research framework is an educational research framework. This framework focuses on studying various aspects of education, such as teaching methods, curriculum development, and student learning outcomes. It may include components like educational theories, pedagogical approaches, and assessment methods. Researchers can use this framework to guide their studies and gain insights into improving educational practices and policies.

Example 3: Health Research Framework

A health research framework is another common example. This framework is used to investigate different aspects of health, such as disease prevention, healthcare delivery, and patient outcomes. It may include components like epidemiological models, healthcare systems analysis, and health behavior theories. Researchers can utilize this framework to design studies that contribute to the understanding and improvement of healthcare practices and policies.

Example 4: Business Research Framework

In the field of business, a research framework can be developed to study various aspects of business operations, management strategies, and market dynamics. This framework may include components like organizational theories, market analysis models, and strategic planning frameworks. Researchers can apply this framework to investigate business-related phenomena and provide valuable insights for decision-making and industry development.

Example 5: Social Science Research Framework

A social science research framework is designed to study human behavior, social structures, and societal issues. It may include components like sociological theories, psychological models, and qualitative research methods. Researchers in the social sciences can use this framework to explore and analyze various social phenomena, contributing to the understanding and improvement of society as a whole.

In conclusion, a research framework provides a structured approach to organizing and analyzing research data, allowing researchers to make informed decisions and draw meaningful conclusions. Throughout this guide, we have delved into the nature of research frameworks, including their components, types, methodologies, and practical examples. These frameworks are essential tools for conducting effective and efficient research, helping researchers streamline processes, enhance the quality of findings, and contribute significantly to their fields.

However, it is important to recognize that research frameworks are not a one-size-fits-all solution; they may need to be tailored to suit the specific objectives, scope, and context of individual research projects. While these frameworks provide essential structure, they should not replace critical thinking and creativity. Researchers are encouraged to remain open to new ideas and perspectives, adapting frameworks to meet their unique needs and navigate the complexities of the research process, thereby advancing knowledge within their disciplines.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Writing engaging introduction in research papers : tips and tricks.

Understanding Comparative Frameworks: Their Importance, Components, Examples and 8 Best Practices

Revolutionizing Effective Thesis Writing for PhD Students Using Artificial Intelligence!

3 Types of Interviews in Qualitative Research: An Essential Research Instrument and Handy Tips to Conduct Them

Highlight Abstracts: An Ultimate Guide For Researchers!

Crafting Critical Abstracts: 11 Expert Strategies for Summarizing Research

Crafting the Perfect Informative Abstract: Definition, Importance and 8 Expert Writing Tips

Descriptive Abstracts: A Complete Guide to Crafting Effective Summaries in Research Writing

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on August 2, 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on March 18, 2024.

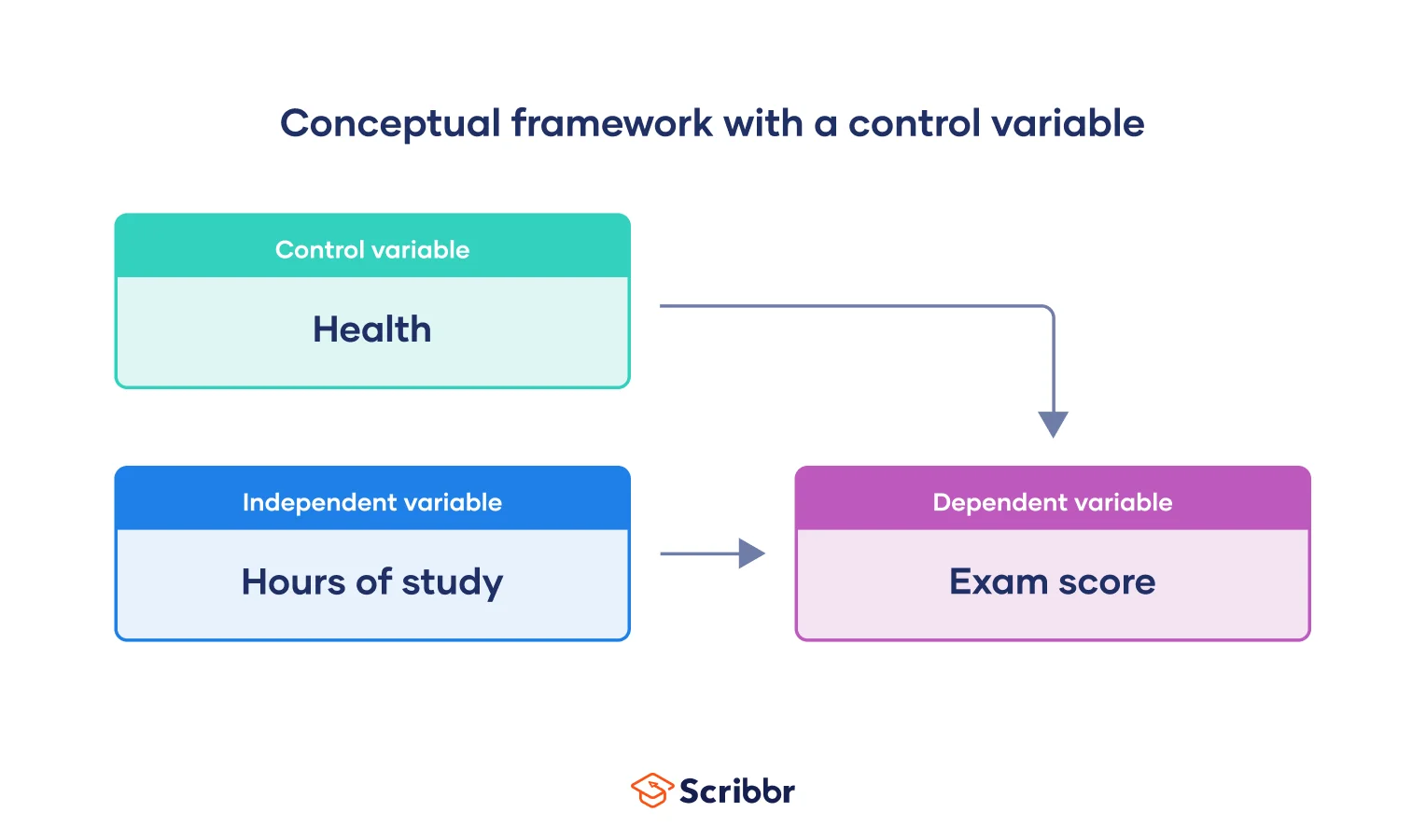

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualize your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

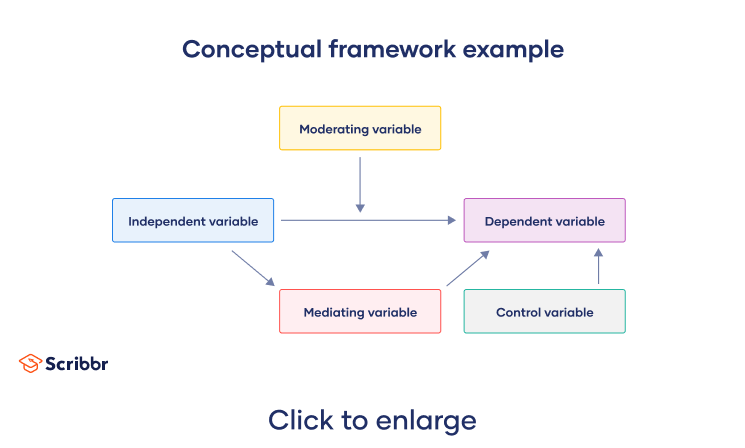

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

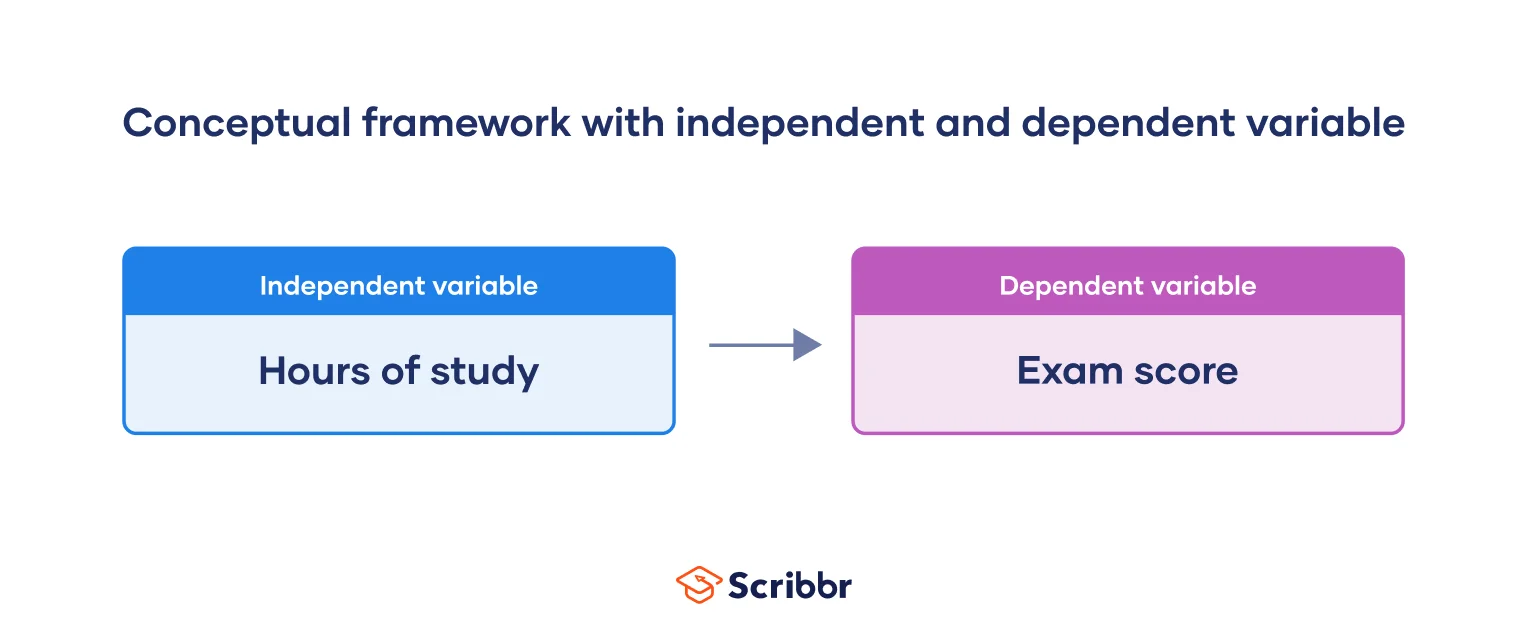

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, “hours of study,” is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, “exam score,” is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (“hours of study”).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualizing your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

We demonstrate this using basic design components of boxes and arrows. Here, each variable appears in a box. To indicate a causal relationship, each arrow should start from the independent variable (the cause) and point to the dependent variable (the effect).

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

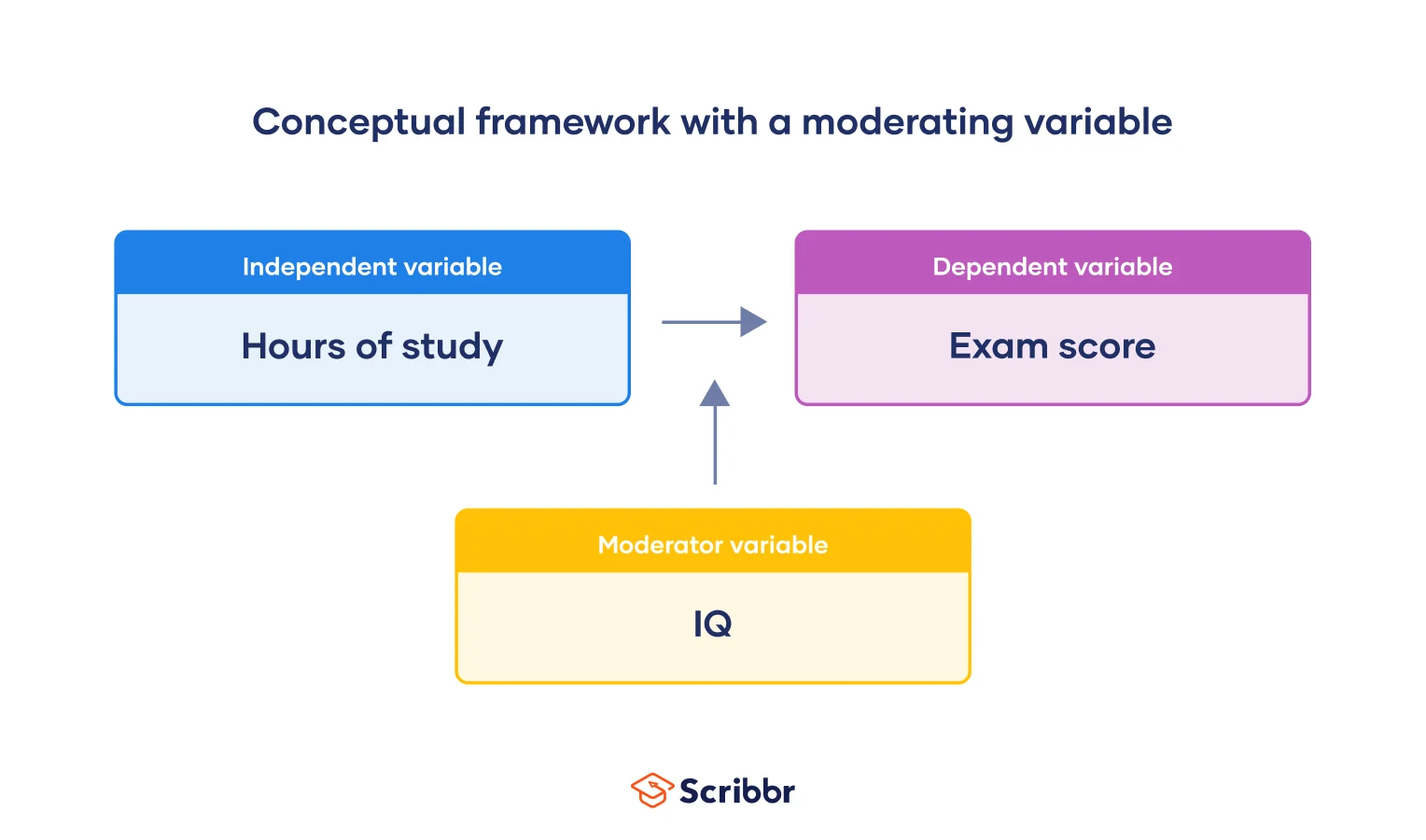

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the “effect” component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

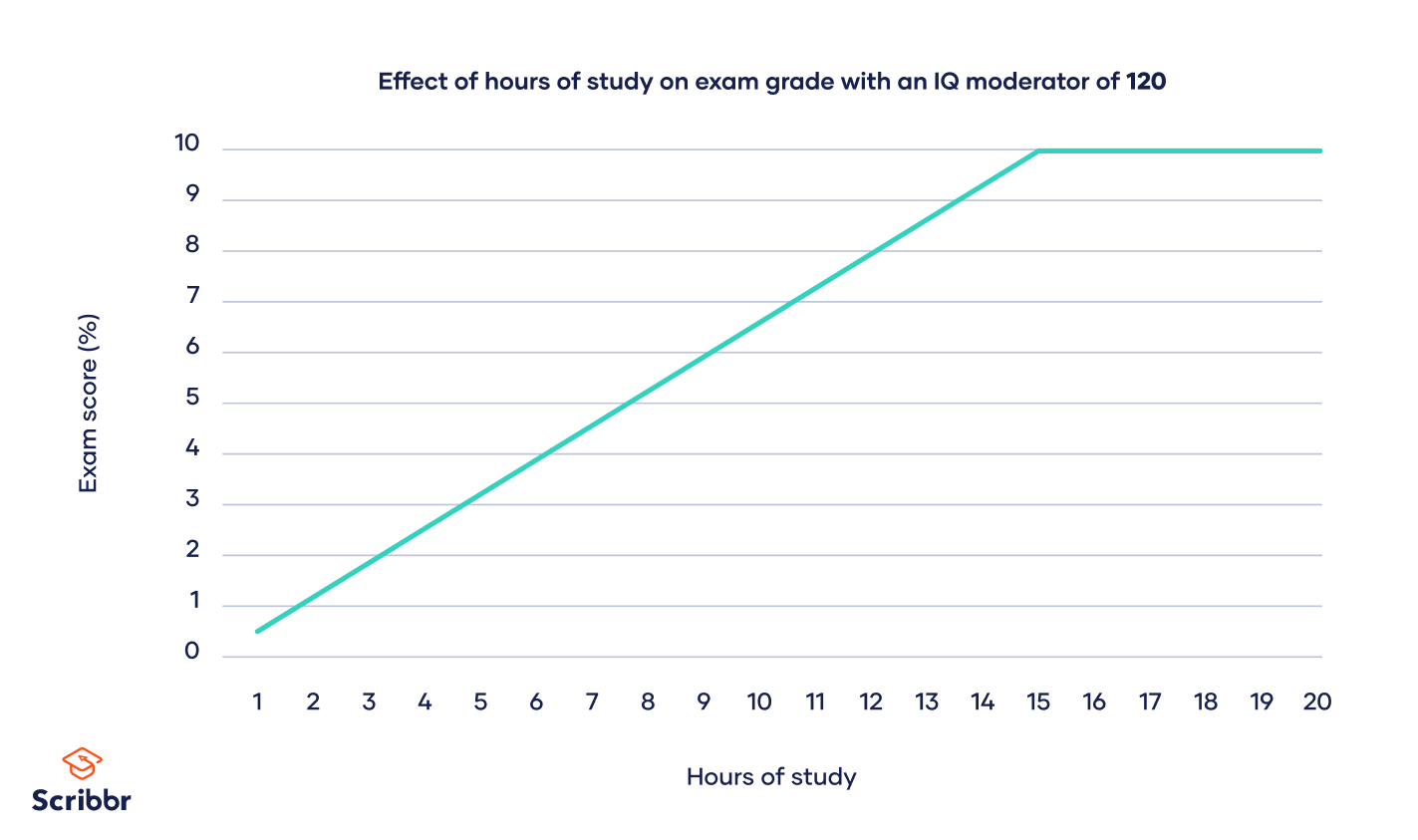

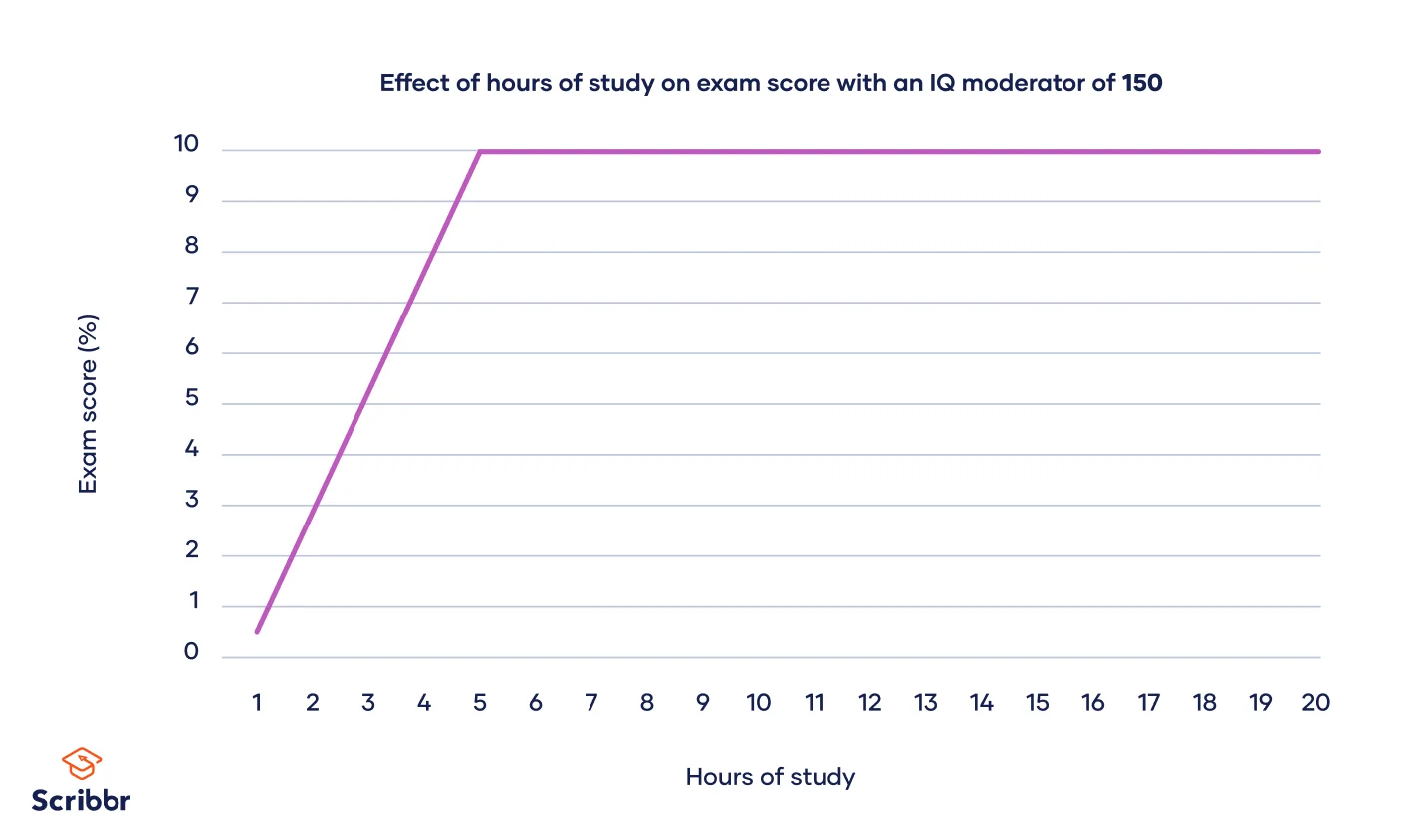

Let’s add the moderator “IQ.” Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable “hours of study” has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

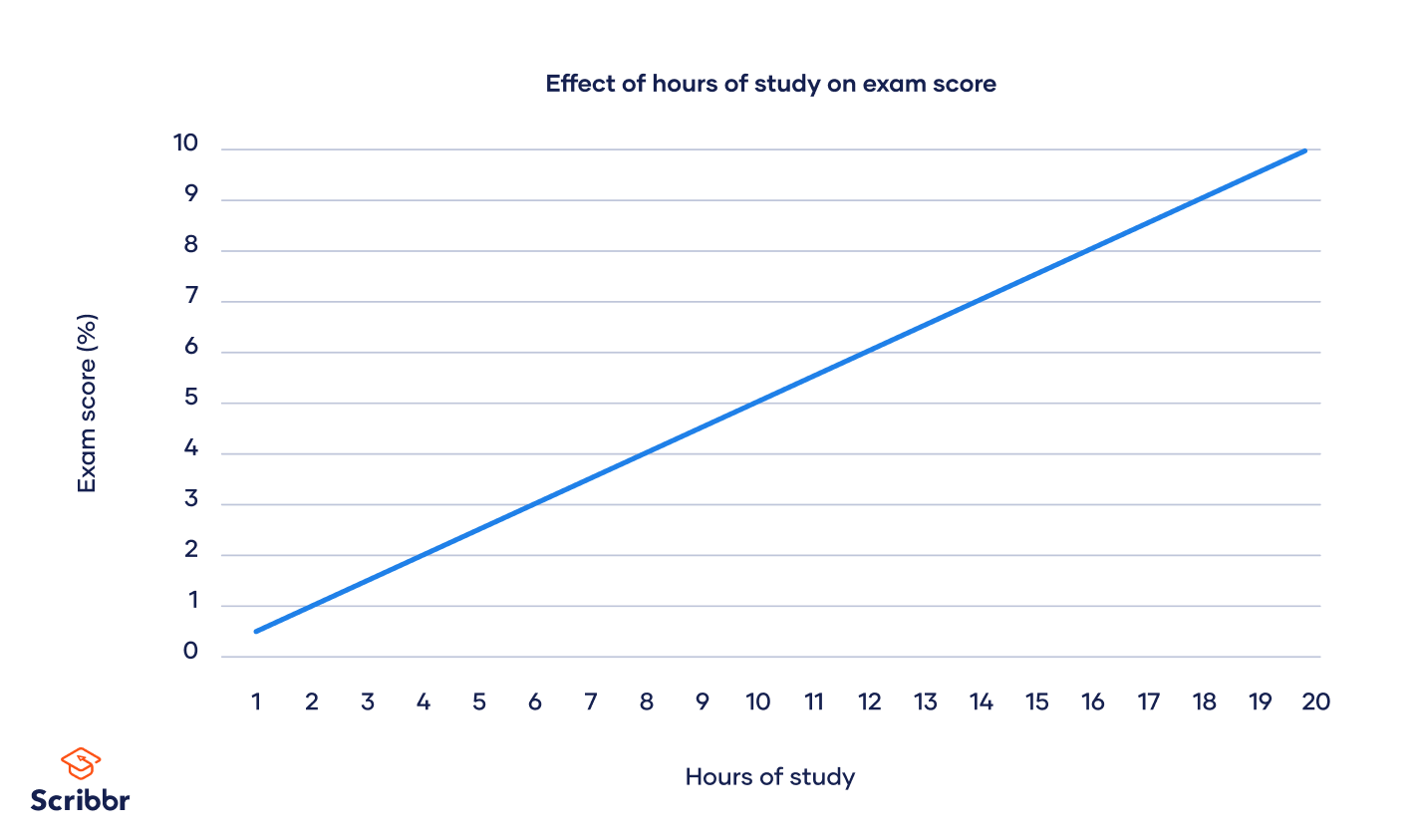

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

But the graph looks different when we add our “IQ” moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

Below, the value of the “IQ” moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

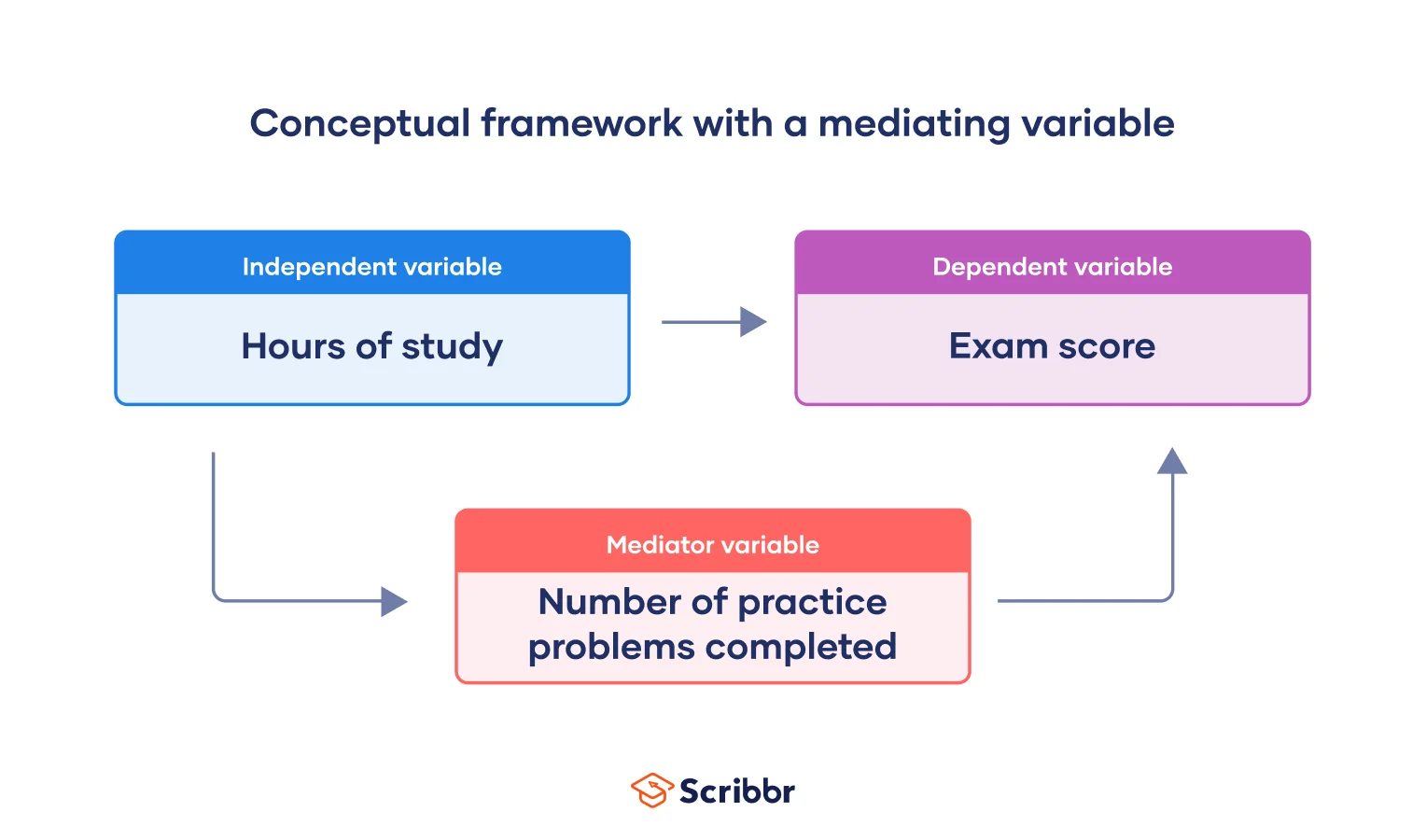

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs. mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, mediator vs. moderator variables | differences & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

What is a good example of a conceptual framework?

Last updated

18 April 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

A well-designed study doesn’t just happen. Researchers work hard to ensure the studies they conduct will be scientifically valid and will advance understanding in their field.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- The importance of a conceptual framework

The main purpose of a conceptual framework is to improve the quality of a research study. A conceptual framework achieves this by identifying important information about the topic and providing a clear roadmap for researchers to study it.

Through the process of developing this information, researchers will be able to improve the quality of their studies in a few key ways.

Clarify research goals and objectives

A conceptual framework helps researchers create a clear research goal. Research projects often become vague and lose their focus, which makes them less useful. However, a well-designed conceptual framework helps researchers maintain focus. It reinforces the project’s scope, ensuring it stays on track and produces meaningful results.

Provide a theoretical basis for the study

Forming a hypothesis requires knowledge of the key variables and their relationship to each other. Researchers need to identify these variables early on to create a conceptual framework. This ensures researchers have developed a strong understanding of the topic before finalizing the study design. It also helps them select the most appropriate research and analysis methods.

Guide the research design

As they develop their conceptual framework, researchers often uncover information that can help them further refine their work.

Here are some examples:

Confounding variables they hadn’t previously considered

Sources of bias they will have to take into account when designing the project

Whether or not the information they were going to study has already been covered—this allows them to pivot to a more meaningful goal that brings new and relevant information to their field

- Steps to develop a conceptual framework

There are four major steps researchers will follow to develop a conceptual framework. Each step will be described in detail in the sections that follow. You’ll also find examples of how each might be applied in a range of fields.

Step 1: Choose the research question

The first step in creating a conceptual framework is choosing a research question . The goal of this step is to create a question that’s specific and focused.

By developing a clear question, researchers can more easily identify the variables they will need to account for and keep their research focused. Without it, the next steps will be more difficult and less effective.

Here are some examples of good research questions in a few common fields:

Natural sciences: How does exposure to ultraviolet radiation affect the growth rate of a particular type of algae?

Health sciences: What is the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating depression in adolescents?

Business: What factors contribute to the success of small businesses in a particular industry?

Education: How does implementing technology in the classroom impact student learning outcomes?

Step 2: Select the independent and dependent variables

Once the research question has been chosen, it’s time to identify the dependent and independent variables .

The independent variable is the variable researchers think will affect the dependent variable . Without this information, researchers cannot develop a meaningful hypothesis or design a way to test it.

The dependent and independent variables for our example questions above are:

Natural sciences

Independent variable: exposure to ultraviolet radiation

Dependent variable: the growth rate of a particular type of algae

Health sciences

Independent variable: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Dependent variable: depression in adolescents

Independent variables: factors contributing to the business’s success

Dependent variable: sales, return on investment (ROI), or another concrete metric

Independent variable: implementation of technology in the classroom

Dependent variable: student learning outcomes, such as test scores, GPAs, or exam results

Step 3: Visualize the cause-and-effect relationship

This step is where researchers actually develop their hypothesis. They will predict how the independent variable will impact the dependent variable based on their knowledge of the field and their intuition.

With a hypothesis formed, researchers can more accurately determine what data to collect and how to analyze it. They will then visualize their hypothesis by creating a diagram. This visualization will serve as a framework to help guide their research.

The diagrams for our examples might be used as follows:

Natural sciences : how exposure to radiation affects the biological processes in the algae that contribute to its growth rate

Health sciences : how different aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy can affect how patients experience symptoms of depression

Business : how factors such as market demand, managerial expertise, and financial resources influence a business’s success

Education : how different types of technology interact with different aspects of the learning process and alter student learning outcomes

Step 4: Identify other influencing variables

The independent and dependent variables are only part of the equation. Moderating, mediating, and control variables are also important parts of a well-designed study. These variables can impact the relationship between the two main variables and must be accounted for.

A moderating variable is one that can change how the independent variable affects the dependent variable. A mediating variable explains the relationship between the two. Control variables are kept the same to eliminate their impact on the results. Examples of each are given below:

Moderating variable: water temperature (might impact how algae respond to radiation exposure)

Mediating variable: chlorophyll production (might explain how radiation exposure affects algae growth rate)

Control variable: nutrient levels in the water

Moderating variable: the severity of depression symptoms at baseline might impact how effective the therapy is for different adolescents

Mediating variable: social support might explain how cognitive-behavioral therapy leads to improvements in depression

Control variable: other forms of treatment received before or during the study

Moderating variable: the size of the business (might impact how different factors contribute to market share, sales, ROI, and other key success metrics)

Mediating variable: customer satisfaction (might explain how different factors impact business success)

Control variable: industry competition

Moderating variable: student age (might impact how effective technology is for different students)

Mediating variable: teacher training (might explain how technology leads to improvements in learning outcomes)

Control variable: student learning style

- Conceptual versus theoretical frameworks

Although they sound similar, conceptual and theoretical frameworks have different goals and are used in different contexts. Understanding which to use will help researchers craft better studies.

Conceptual frameworks describe a broad overview of the subject and outline key concepts, variables, and the relationships between them. They provide structure to studies that are more exploratory in nature, where the relationships between the variables are still being established. They are particularly helpful in studies that are complex or interdisciplinary because they help researchers better organize the factors involved in the study.

Theoretical frameworks, on the other hand, are used when the research question is more clearly defined and there’s an existing body of work to draw upon. They define the relationships between the variables and help researchers predict outcomes. They are particularly helpful when researchers want to refine the existing body of knowledge rather than establish it.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Theoretical Framework? How to Write It (with Examples)

Theoretical framework 1,2 is the structure that supports and describes a theory. A theory is a set of interrelated concepts and definitions that present a systematic view of phenomena by describing the relationship among the variables for explaining these phenomena. A theory is developed after a long research process and explains the existence of a research problem in a study. A theoretical framework guides the research process like a roadmap for the research study and helps researchers clearly interpret their findings by providing a structure for organizing data and developing conclusions.

A theoretical framework in research is an important part of a manuscript and should be presented in the first section. It shows an understanding of the theories and concepts relevant to the research and helps limit the scope of the research.

Table of Contents

What is a theoretical framework ?

A theoretical framework in research can be defined as a set of concepts, theories, ideas, and assumptions that help you understand a specific phenomenon or problem. It can be considered a blueprint that is borrowed by researchers to develop their own research inquiry. A theoretical framework in research helps researchers design and conduct their research and analyze and interpret their findings. It explains the relationship between variables, identifies gaps in existing knowledge, and guides the development of research questions, hypotheses, and methodologies to address that gap.

Now that you know the answer to ‘ What is a theoretical framework? ’, check the following table that lists the different types of theoretical frameworks in research: 3

| Conceptual | Defines key concepts and relationships |

| Deductive | Starts with a general hypothesis and then uses data to test it; used in quantitative research |

| Inductive | Starts with data and then develops a hypothesis; used in qualitative research |

| Empirical | Focuses on the collection and analysis of empirical data; used in scientific research |

| Normative | Defines a set of norms that guide behavior; used in ethics and social sciences |

| Explanatory | Explains causes of particular behavior; used in psychology and social sciences |

Developing a theoretical framework in research can help in the following situations: 4

- When conducting research on complex phenomena because a theoretical framework helps organize the research questions, hypotheses, and findings

- When the research problem requires a deeper understanding of the underlying concepts

- When conducting research that seeks to address a specific gap in knowledge

- When conducting research that involves the analysis of existing theories

Summarizing existing literature for theoretical frameworks is easy. Get our Research Ideation pack

Importance of a theoretical framework

The purpose of theoretical framework s is to support you in the following ways during the research process: 2

- Provide a structure for the complete research process

- Assist researchers in incorporating formal theories into their study as a guide

- Provide a broad guideline to maintain the research focus

- Guide the selection of research methods, data collection, and data analysis

- Help understand the relationships between different concepts and develop hypotheses and research questions

- Address gaps in existing literature

- Analyze the data collected and draw meaningful conclusions and make the findings more generalizable

Theoretical vs. Conceptual framework

While a theoretical framework covers the theoretical aspect of your study, that is, the various theories that can guide your research, a conceptual framework defines the variables for your study and presents how they relate to each other. The conceptual framework is developed before collecting the data. However, both frameworks help in understanding the research problem and guide the development, collection, and analysis of the research.

The following table lists some differences between conceptual and theoretical frameworks . 5

| Based on existing theories that have been tested and validated by others | Based on concepts that are the main variables in the study |

| Used to create a foundation of the theory on which your study will be developed | Visualizes the relationships between the concepts and variables based on the existing literature |

| Used to test theories, to predict and control the situations within the context of a research inquiry | Helps the development of a theory that would be useful to practitioners |

| Provides a general set of ideas within which a study belongs | Refers to specific ideas that researchers utilize in their study |

| Offers a focal point for approaching unknown research in a specific field of inquiry | Shows logically how the research inquiry should be undertaken |

| Works deductively | Works inductively |

| Used in quantitative studies | Used in qualitative studies |

How to write a theoretical framework

The following general steps can help those wondering how to write a theoretical framework: 2

- Identify and define the key concepts clearly and organize them into a suitable structure.

- Use appropriate terminology and define all key terms to ensure consistency.

- Identify the relationships between concepts and provide a logical and coherent structure.

- Develop hypotheses that can be tested through data collection and analysis.

- Keep it concise and focused with clear and specific aims.

Write a theoretical framework 2x faster. Get our Manuscript Writing pack

Examples of a theoretical framework

Here are two examples of a theoretical framework. 6,7

Example 1 .

An insurance company is facing a challenge cross-selling its products. The sales department indicates that most customers have just one policy, although the company offers over 10 unique policies. The company would want its customers to purchase more than one policy since most customers are purchasing policies from other companies.

Objective : To sell more insurance products to existing customers.

Problem : Many customers are purchasing additional policies from other companies.

Research question : How can customer product awareness be improved to increase cross-selling of insurance products?

Sub-questions: What is the relationship between product awareness and sales? Which factors determine product awareness?

Since “product awareness” is the main focus in this study, the theoretical framework should analyze this concept and study previous literature on this subject and propose theories that discuss the relationship between product awareness and its improvement in sales of other products.

Example 2 .

A company is facing a continued decline in its sales and profitability. The main reason for the decline in the profitability is poor services, which have resulted in a high level of dissatisfaction among customers and consequently a decline in customer loyalty. The management is planning to concentrate on clients’ satisfaction and customer loyalty.

Objective: To provide better service to customers and increase customer loyalty and satisfaction.

Problem: Continued decrease in sales and profitability.

Research question: How can customer satisfaction help in increasing sales and profitability?

Sub-questions: What is the relationship between customer loyalty and sales? Which factors influence the level of satisfaction gained by customers?

Since customer satisfaction, loyalty, profitability, and sales are the important topics in this example, the theoretical framework should focus on these concepts.

Benefits of a theoretical framework

There are several benefits of a theoretical framework in research: 2

- Provides a structured approach allowing researchers to organize their thoughts in a coherent way.

- Helps to identify gaps in knowledge highlighting areas where further research is needed.

- Increases research efficiency by providing a clear direction for research and focusing efforts on relevant data.

- Improves the quality of research by providing a rigorous and systematic approach to research, which can increase the likelihood of producing valid and reliable results.

- Provides a basis for comparison by providing a common language and conceptual framework for researchers to compare their findings with other research in the field, facilitating the exchange of ideas and the development of new knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How do I develop a theoretical framework ? 7

A1. The following steps can be used for developing a theoretical framework :

- Identify the research problem and research questions by clearly defining the problem that the research aims to address and identifying the specific questions that the research aims to answer.

- Review the existing literature to identify the key concepts that have been studied previously. These concepts should be clearly defined and organized into a structure.

- Develop propositions that describe the relationships between the concepts. These propositions should be based on the existing literature and should be testable.

- Develop hypotheses that can be tested through data collection and analysis.

- Test the theoretical framework through data collection and analysis to determine whether the framework is valid and reliable.

Q2. How do I know if I have developed a good theoretical framework or not? 8

A2. The following checklist could help you answer this question:

- Is my theoretical framework clearly seen as emerging from my literature review?

- Is it the result of my analysis of the main theories previously studied in my same research field?

- Does it represent or is it relevant to the most current state of theoretical knowledge on my topic?

- Does the theoretical framework in research present a logical, coherent, and analytical structure that will support my data analysis?

- Do the different parts of the theory help analyze the relationships among the variables in my research?

- Does the theoretical framework target how I will answer my research questions or test the hypotheses?

- Have I documented every source I have used in developing this theoretical framework ?

- Is my theoretical framework a model, a table, a figure, or a description?

- Have I explained why this is the appropriate theoretical framework for my data analysis?

Q3. Can I use multiple theoretical frameworks in a single study?

A3. Using multiple theoretical frameworks in a single study is acceptable as long as each theory is clearly defined and related to the study. Each theory should also be discussed individually. This approach may, however, be tedious and effort intensive. Therefore, multiple theoretical frameworks should be used only if absolutely necessary for the study.

Q4. Is it necessary to include a theoretical framework in every research study?

A4. The theoretical framework connects researchers to existing knowledge. So, including a theoretical framework would help researchers get a clear idea about the research process and help structure their study effectively by clearly defining an objective, a research problem, and a research question.

Q5. Can a theoretical framework be developed for qualitative research?

A5. Yes, a theoretical framework can be developed for qualitative research. However, qualitative research methods may or may not involve a theory developed beforehand. In these studies, a theoretical framework can guide the study and help develop a theory during the data analysis phase. This resulting framework uses inductive reasoning. The outcome of this inductive approach can be referred to as an emergent theoretical framework . This method helps researchers develop a theory inductively, which explains a phenomenon without a guiding framework at the outset.

Q6. What is the main difference between a literature review and a theoretical framework ?

A6. A literature review explores already existing studies about a specific topic in order to highlight a gap, which becomes the focus of the current research study. A theoretical framework can be considered the next step in the process, in which the researcher plans a specific conceptual and analytical approach to address the identified gap in the research.

Theoretical frameworks are thus important components of the research process and researchers should therefore devote ample amount of time to develop a solid theoretical framework so that it can effectively guide their research in a suitable direction. We hope this article has provided a good insight into the concept of theoretical frameworks in research and their benefits.

References

- Organizing academic research papers: Theoretical framework. Sacred Heart University library. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185919#:~:text=The%20theoretical%20framework%20is%20the,research%20problem%20under%20study%20exists .

- Salomao A. Understanding what is theoretical framework. Mind the Graph website. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/what-is-theoretical-framework/

- Theoretical framework—Types, examples, and writing guide. Research Method website. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/theoretical-framework/

- Grant C., Osanloo A. Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your “house.” Administrative Issues Journal : Connecting Education, Practice, and Research; 4(2):12-26. 2014. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1058505.pdf

- Difference between conceptual framework and theoretical framework. MIM Learnovate website. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://mimlearnovate.com/difference-between-conceptual-framework-and-theoretical-framework/

- Example of a theoretical framework—Thesis & dissertation. BacherlorPrint website. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.bachelorprint.com/dissertation/example-of-a-theoretical-framework/

- Sample theoretical framework in dissertation and thesis—Overview and example. Students assignment help website. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.studentsassignmenthelp.co.uk/blogs/sample-dissertation-theoretical-framework/#Example_of_the_theoretical_framework

- Kivunja C. Distinguishing between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework: A systematic review of lessons from the field. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1198682.pdf

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What is IMRaD Format in Research?

What is a Review Article? How to Write it?

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Strategy Frameworks & Tools You Can Use Right Now

- 10 Dec 2020

As a manager, business owner, or employee, you’re always seeking ways to contribute to your organization’s growth. One way to do so is by helping formulate or execute an effective business strategy.

Your organization’s strategy should be tailored to fit your business’s goals and objectives . It also requires continually measuring your business performance and reassessing as new challenges and opportunities arise.

While crafting and executing a strategy takes time, there are frameworks and tools you can use to assess your business’s position in a competitive landscape and its approach to factors like pricing and product-market fit .

Access your free e-book today.

What Is a Strategy Framework?

Strategic frameworks are structured approaches or lenses used to conceptualize, develop, and implement strategic plans. These frameworks serve as guides to help organizations define and reach their vision and goals. Using frameworks and tools at any stage of the strategic process can offer a competitive advantage.

Here are five strategy frameworks and tools you can use right now to contribute to your organization’s growth.

Strategy Frameworks and Tools You Should Know

1. jobs to be done framework.

The Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework, developed by Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen, is a way to validate a consumer’s need for a product.

The basis of Christensen’s theory is that, when people purchase products, they “hire” them to do a “job.”

By asking yourself what job your company’s offering can do for consumers, you can hone brand messaging, differentiate your product from competitors’, and improve it to more effectively complete the job to be done.

One example of this framework in action is Kind Snacks’ line of breakfast bars . While Kind Snacks sells many types of granola bars, cereals, and other healthy options, the breakfast bars contain at least one full serving of whole grains, and some flavors contain extra protein and probiotics. These specific bars fill its customers’ need for a healthy, filling breakfast option that can be taken on the go.

The JTBD framework can be used during any stage of product development—to create a new product based on a customer job that isn’t being done yet, or to reassess the jobs your existing products fulfill. How has the customer need shifted since the conception of your offering, and how can this knowledge shape your business strategy?

A strong understanding and alignment on the customer need your product fills can be a foundation for following through on strategic plans.

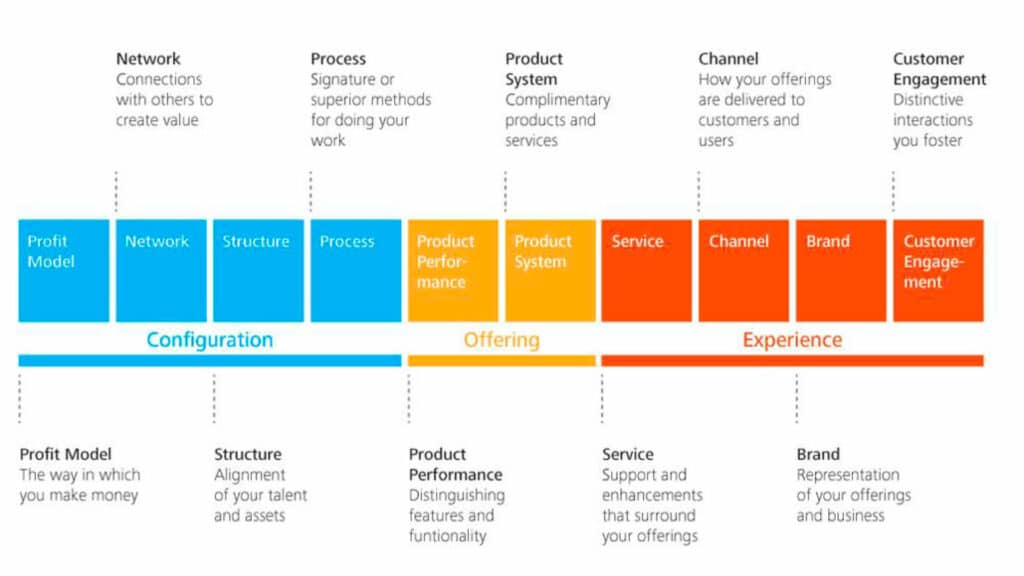

2. Value Stick Framework

The value stick framework is a visual representation of a product’s value based on customers’ willingness to pay for it. This framework is helpful when formulating a product’s pricing strategy , and it can also be an important part of an organization’s broader strategic plan.

The value stick has four components:

- Willingness to pay : The highest price a customer is willing to pay for your product or service.

- Price: The amount of money you charge for a product or service.

- Cost: The amount of money it takes to produce a product or service.

- Willingness to sell: The lowest price a firm’s suppliers are willing to accept in exchange for the raw materials needed to create products.

Each of these components fall somewhere along the stick, and their locations determine the value of the product to the customer, supplier, and business.

Picturing each of these factors as sliders on a stick can allow you to test out different scenarios and aid in strategic decision-making. If you lower the production cost, will the customer’s willingness to pay decrease? If you raise the production cost and price, will the customer’s willingness to pay increase? If so, is it worth it?

Understanding the relationship between the supplier, business, and customer, and how each entity gains value from your product, is an important exercise during strategy formulation.

Related: 2 Ways to Increase Profit Margin Using Value-Based Pricing

3. Job Design Optimization Tool

The Job Design Optimization Tool, or JDOT, was created by HBS Professor Robert Simons and is a free, online tool that anyone can use.

In the online course Strategy Execution , Simons explains that jobs are optimized for high performance when they’re designed in service of the company’s strategy. The JDOT enables you to assess the degree to which each role at your organization is optimized for strategic success.

Each job is evaluated based on four factors, or “spans,” which are presented on a sliding bar: control, accountability, influence, and support. By adjusting the bars, you can determine the amount of each span that a specific role in your organization holds.

If the bars you’ve adjusted form an “X” in the tool, this indicates that the job is “balanced”—its supply of resources is equal to its demand for resources.” The JDOT then provides recommendations to improve the role, depending on which spans are out of balance. For instance, if you’re looking to increase the span of influence, the JDOT suggests implementing cross-unit task forces and providing stretch goals.

“If you get the settings right, you can design a job in which a talented individual can successfully execute your company’s strategy,” Simons writes in the Harvard Business Review . “But if you get the settings wrong, it will be difficult for any employee to be effective.”

Keep your organization’s strategy in mind when using the JDOT to assess its roles. If any role is revealed to be unbalanced, consider raising the tool’s suggestions to your team so that everyone has the resources necessary to support the company’s strategy.

Related: 5 Keys to Successful Strategy Execution

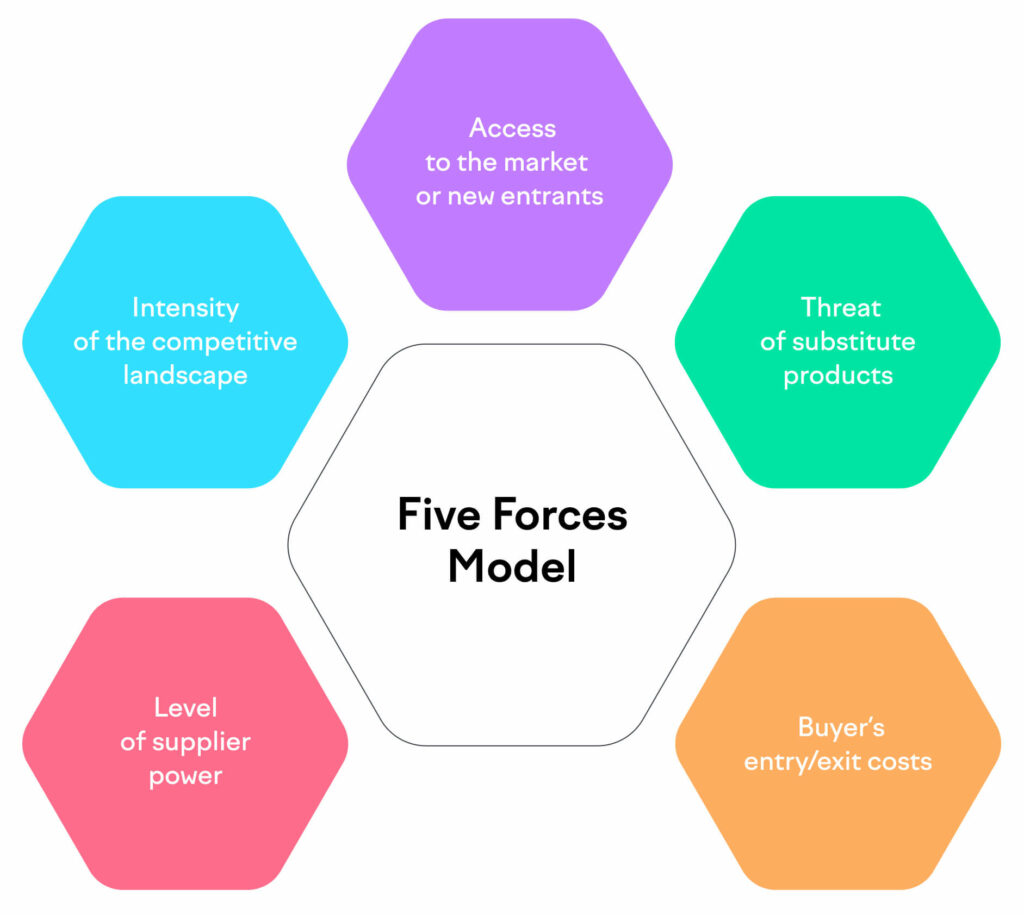

4. Disruptive Innovation Framework

Disruptive innovation, another concept coined by Christensen, refers to the process by which a smaller company—usually with fewer resources—moves upmarket and challenges larger, established businesses. The other type of innovation included in the framework is sustaining innovation , in which a company creates better-performing products to sell for higher profits to its best customers.

There are two types of disruptive innovation : low-end disruption and new-market disruption.

Low-end disruption occurs when an organization uses a low-cost business model to enter at the bottom of a market and claim an existing segment. New-market disruption, on the other hand, occurs when an organization enters at the bottom of an existing market and creates and claims a new segment.

Think about your organization’s place in the market. What segments does your brand own? Who are your competitors, and what differentiates them from your business? Are there any opportunities for your organization to either claim an existing low-end market segment or create a new one? If your organization is a big player in the market, how can you prepare for potential disruption?

Considering questions like these can raise valuable insights, opportunities, and concerns that influence your organization’s strategy.

Learn more about sustaining and disruptive innovation in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5. Balanced Scorecard

The balanced scorecard —developed in 1992 by HBS Professor Robert Kaplan and David Norton—is a tool that tracks and measures non-financial variables.

“The balanced scorecard combines the traditional financial perspective with additional perspectives that focus on customers, internal business processes, and learning and development,” Simons says in Strategy Execution . “These additional perspectives help businesses measure all the activities essential to creating value.”

The four perspectives include:

- Financial: Do your plans and processes lead to desired levels of economic value creation?

- Customer: Does your target audience perceive your product, services, and brand in the desired way?

- Internal business process: Do your organizational processes create value for customers?

- Learning and growth: Does your organization support and utilize human capital and infrastructure resources to meet goals?

To ensure you get the most out of your balanced scorecard, it’s crucial to use a strategy map as well. A strategy map is a visual representation of the relationships that directly impact your business strategy.

“A strategy map gives everyone in your business a road map to understand the relationship between goals and measures and how they build on each other to create value,” Simons says in Strategy Execution .

Creating a Strategic Foundation

The process of setting goals and formulating and executing a strategy to reach them is time-intensive and requires daily reassessment. Leveraging powerful tools and frameworks to shift your perspective, offer insight, and ensure alignment can make all the difference between an unsuccessful strategy and one that provides positive organizational growth.

Are you interested in elevating your strategic formulation, execution, or decision-making skills? Explore our online strategy courses and download our free flowchart to find the right HBS Online Strategy course for you.

This post was updated on December 8, 2023. It was originally published on December 10, 2020.

About the Author

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Design

Definition:

Research design refers to the overall strategy or plan for conducting a research study. It outlines the methods and procedures that will be used to collect and analyze data, as well as the goals and objectives of the study. Research design is important because it guides the entire research process and ensures that the study is conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner.

Types of Research Design

Types of Research Design are as follows:

Descriptive Research Design

This type of research design is used to describe a phenomenon or situation. It involves collecting data through surveys, questionnaires, interviews, and observations. The aim of descriptive research is to provide an accurate and detailed portrayal of a particular group, event, or situation. It can be useful in identifying patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational research design is used to determine if there is a relationship between two or more variables. This type of research design involves collecting data from participants and analyzing the relationship between the variables using statistical methods. The aim of correlational research is to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This type of research design involves manipulating one variable and measuring the effect on another variable. It usually involves randomly assigning participants to groups and manipulating an independent variable to determine its effect on a dependent variable. The aim of experimental research is to establish causality.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is similar to experimental research design, but it lacks one or more of the features of a true experiment. For example, there may not be random assignment to groups or a control group. This type of research design is used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a true experiment.

Case Study Research Design

Case study research design is used to investigate a single case or a small number of cases in depth. It involves collecting data through various methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. The aim of case study research is to provide an in-depth understanding of a particular case or situation.

Longitudinal Research Design

Longitudinal research design is used to study changes in a particular phenomenon over time. It involves collecting data at multiple time points and analyzing the changes that occur. The aim of longitudinal research is to provide insights into the development, growth, or decline of a particular phenomenon over time.

Structure of Research Design

The format of a research design typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem, the research questions, and the importance of the study. It also includes a brief literature review that summarizes previous research on the topic and identifies gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Research Questions or Hypotheses: This section identifies the specific research questions or hypotheses that the study will address. These questions should be clear, specific, and testable.

- Research Methods : This section describes the methods that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes details about the study design, the sampling strategy, the data collection instruments, and the data analysis techniques.

- Data Collection: This section describes how the data will be collected, including the sample size, data collection procedures, and any ethical considerations.

- Data Analysis: This section describes how the data will be analyzed, including the statistical techniques that will be used to test the research questions or hypotheses.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including descriptive statistics and statistical tests.

- Discussion and Conclusion : This section summarizes the key findings of the study, interprets the results, and discusses the implications of the findings. It also includes recommendations for future research.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research design.

Example of Research Design

An Example of Research Design could be:

Research question: Does the use of social media affect the academic performance of high school students?

Research design:

- Research approach : The research approach will be quantitative as it involves collecting numerical data to test the hypothesis.

- Research design : The research design will be a quasi-experimental design, with a pretest-posttest control group design.

- Sample : The sample will be 200 high school students from two schools, with 100 students in the experimental group and 100 students in the control group.

- Data collection : The data will be collected through surveys administered to the students at the beginning and end of the academic year. The surveys will include questions about their social media usage and academic performance.

- Data analysis : The data collected will be analyzed using statistical software. The mean scores of the experimental and control groups will be compared to determine whether there is a significant difference in academic performance between the two groups.

- Limitations : The limitations of the study will be acknowledged, including the fact that social media usage can vary greatly among individuals, and the study only focuses on two schools, which may not be representative of the entire population.

- Ethical considerations: Ethical considerations will be taken into account, such as obtaining informed consent from the participants and ensuring their anonymity and confidentiality.

How to Write Research Design

Writing a research design involves planning and outlining the methodology and approach that will be used to answer a research question or hypothesis. Here are some steps to help you write a research design:

- Define the research question or hypothesis : Before beginning your research design, you should clearly define your research question or hypothesis. This will guide your research design and help you select appropriate methods.

- Select a research design: There are many different research designs to choose from, including experimental, survey, case study, and qualitative designs. Choose a design that best fits your research question and objectives.

- Develop a sampling plan : If your research involves collecting data from a sample, you will need to develop a sampling plan. This should outline how you will select participants and how many participants you will include.

- Define variables: Clearly define the variables you will be measuring or manipulating in your study. This will help ensure that your results are meaningful and relevant to your research question.

- Choose data collection methods : Decide on the data collection methods you will use to gather information. This may include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data sources.

- Create a data analysis plan: Develop a plan for analyzing your data, including the statistical or qualitative techniques you will use.

- Consider ethical concerns : Finally, be sure to consider any ethical concerns related to your research, such as participant confidentiality or potential harm.

When to Write Research Design