| Creative Biz Describe Nature Creatively: A Guide to Captivating DescriptionsHow to describe nature in creative writing – Welcome to the art of describing nature in creative writing! In this guide, we’ll dive into the techniques and strategies that will transform your nature descriptions from ordinary to extraordinary. From capturing the sensory details to conveying the emotions evoked by nature, we’ll explore a range of approaches to help you create vivid and immersive nature scenes that will leave your readers spellbound. Sensory Details Nature’s beauty lies in its intricate tapestry of sensory experiences. To effectively describe nature in writing, it is essential to engage all five senses to create a vivid and immersive portrayal that transports the reader into the heart of the natural world. Sensory details provide a tangible and visceral connection to the environment, allowing readers to experience nature through their imagination. By capturing the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures of the natural world, writers can evoke a profound sense of place and connection. Visual descriptions are the most prominent and often the first sensory detail that comes to mind. When describing nature, focus on the colors, shapes, sizes, and textures of the surroundings. Use specific and evocative language that paints a clear picture in the reader’s mind. - Instead of writing “there were many trees,” describe the “towering oaks with their gnarled trunks and emerald canopies.”

- Instead of saying “the water was blue,” describe the “azure waters that shimmered like a thousand diamonds under the sunlight.”

Sounds add depth and atmosphere to a natural setting. Describe the cacophony of birdsong, the gentle rustling of leaves in the wind, or the thunderous roar of a waterfall. Use onomatopoeia and sensory verbs to create a vivid auditory experience. - Instead of writing “the birds were singing,” describe the “melodic chorus of birdsong that filled the air, a symphony of chirps, trills, and whistles.”

- Instead of saying “the wind blew,” describe the “wind that whispered through the trees, carrying the sweet scent of wildflowers.”

Smells evoke powerful memories and emotions. Describe the fragrant scent of blooming flowers, the earthy aroma of damp soil, or the salty tang of the ocean breeze. Use evocative language that transports the reader to the heart of the natural world. - Instead of writing “the flowers smelled nice,” describe the “heady perfume of jasmine that permeated the air, a sweet and intoxicating fragrance.”

- Instead of saying “the forest smelled musty,” describe the “earthy scent of the forest floor, mingled with the fresh aroma of pine needles and the sweet decay of fallen leaves.”

While taste is less commonly associated with nature descriptions, it can add a unique and immersive element to your writing. Describe the tart sweetness of wild berries, the salty tang of seawater, or the earthy flavor of fresh herbs. - Instead of writing “the berries were sweet,” describe the “sweet and juicy berries that burst in my mouth, releasing a burst of tart and tangy flavor.”

- Instead of saying “the water was salty,” describe the “salty tang of the seawater as it kissed my lips, leaving a lingering taste of the ocean.”

Textures provide a tactile dimension to your writing. Describe the rough bark of a tree, the smooth surface of a lake, or the velvety softness of a flower petal. Use descriptive language that evokes a physical sensation in the reader. - Instead of writing “the bark was rough,” describe the “rough and gnarled bark of the ancient oak, its deep fissures and ridges creating a tactile tapestry.”

- Instead of saying “the water was smooth,” describe the “smooth and glassy surface of the lake, reflecting the sky like a perfect mirror.”

– Sensory Imagery Engage the reader’s senses with specific and evocative language that appeals to sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. Create a vivid sensory landscape that transports the reader into the heart of nature. - The emerald leaves shimmered like a thousand tiny mirrors, reflecting the dappled sunlight.

- The wind whistled through the trees, a mournful symphony that stirred the soul.

- The soft moss beneath her feet yielded like a downy pillow.

- The pungent scent of wildflowers filled the air, a heady perfume that intoxicated the senses.

- The tangy sweetness of ripe berries burst between her teeth, a taste of summer’s bounty.

Personification: How To Describe Nature In Creative Writing Personification is a literary device that gives human qualities to non-human things, such as animals, plants, or objects. It can make nature more relatable and create a deeper connection between the reader and the natural world. Examples of PersonificationHere are some examples of how personification can be used to create a deeper connection between the reader and the natural world: - The wind whispered secrets to the trees.

- The sun smiled down on the earth.

- The river danced and sang its way to the sea.

These examples give nature human qualities, such as the ability to speak, smile, and dance. This makes nature more relatable and allows the reader to connect with it on a more personal level. Table of Personification Types and EffectsHere is a table that summarizes the different types of personification and their effects on the reader: | Type of Personification | Effect on the Reader |

|---|

| Giving human qualities to animals | Makes animals more relatable and allows the reader to connect with them on a more personal level. | | Giving human qualities to plants | Makes plants more relatable and allows the reader to see them as living beings. | | Giving human qualities to objects | Makes objects more relatable and allows the reader to see them as having a personality. |

Poem Using PersonificationHere is a poem that uses personification to give a voice to a natural object, in this case, a tree: I am a tree, and I have stood for centuries, My roots deep in the earth, my branches reaching for the skies. I have seen the seasons come and go, And I have witnessed the rise and fall of civilizations. I am a silent observer, But I have a story to tell. This poem gives the tree a human voice and allows it to share its story with the reader. This creates a deeper connection between the reader and the natural world. Emotional ImpactNature writing has the power to evoke a wide range of emotions, from awe and wonder to peace and tranquility. Language plays a crucial role in conveying these emotions to the reader, creating a specific mood or atmosphere that enhances the overall impact of the writing. Figurative LanguageFigurative language, such as metaphors and similes, can create powerful emotional connections between the reader and the natural world. Metaphors compare two seemingly unrelated things, while similes use the words “like” or “as” to make a comparison. Both techniques can bring nature to life, giving it human qualities and making it more relatable and emotionally resonant. For example, the poet William Wordsworth uses a metaphor to describe the daffodils in his famous poem “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”: “A host, of golden daffodils;/ Beside the lake, beneath the trees,/ Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.” Here, Wordsworth compares the daffodils to a host of dancers, suggesting their joyful and carefree nature. The use of the word “fluttering” also evokes a sense of movement and energy, further enhancing the emotional impact of the poem. Nature’s Perspective Adopting the perspective of nature can infuse your writing with a profound sense of empathy and ecological consciousness. By giving nature a voice, you can convey its intrinsic value, resilience, and interconnectedness with humanity. Imagine nature as a sentient being, possessing its own thoughts, emotions, and experiences. Describe the landscape through its eyes, capturing the intricate details that often go unnoticed by humans. Explore the interconnectedness of all living organisms, highlighting the delicate balance that sustains the natural world. Voice and ViewpointCraft a distinct voice for nature, using language that reflects its vastness, wisdom, and timelessness. Employ sensory imagery and personification to evoke a vivid and intimate connection between the reader and the natural world. Consider the unique perspective of each element of nature, from the towering mountains to the murmuring streams. Example: “The ancient oak tree stood as a silent guardian, its gnarled roots anchoring it firmly in the earth. Its branches stretched out like welcoming arms, offering shelter to weary travelers and a sanctuary for woodland creatures.” Fresh Insights and Deeper UnderstandingWriting from nature’s perspective offers fresh insights into the human experience and our place within the natural world. By embodying nature, you can challenge anthropocentric viewpoints and foster a greater appreciation for the interdependence of all living beings. Example: “The river flowed relentlessly, carrying with it the memories and secrets of countless journeys. Its waters whispered tales of distant lands and the lives that had touched its banks.” Nature’s Rhythm and MovementNature is a dynamic entity, constantly moving and changing. To effectively capture this dynamism in writing, pay attention to the rhythms, patterns, and cycles that govern the natural world. Describe the ebb and flow of tides, the waxing and waning of the moon, the seasonal changes, and the life cycles of plants and animals. Use descriptive language to convey the movement and flow of nature. For instance, instead of simply stating that the wind is blowing, describe how it rustles through the leaves or whips up the waves. Instead of saying that the river is flowing, describe how it meanders through the landscape or cascades over rocks. Capturing Rhythmic Patterns, How to describe nature in creative writing- Identify the cycles and patterns that occur in nature, such as the changing of seasons, the movement of the stars, or the ebb and flow of tides.

- Use language that conveys rhythm and repetition, such as alliteration, assonance, or onomatopoeia.

- Pay attention to the tempo and cadence of your writing to create a sense of movement and flow.

Conveying Dynamic Movement- Use active verbs and strong action words to describe the movement of natural elements.

- Employ sensory details to create a vivid picture of the movement, such as the sound of wind whistling through trees or the feeling of water rushing over your skin.

- Consider using personification or擬人化 to give natural elements human qualities, such as the wind dancing or the river whispering.

Nature’s Scale and ImmensityWhen describing nature’s scale and immensity, the goal is to convey a sense of awe and wonder at its vastness and grandeur. This can be achieved through the use of language that emphasizes size, distance, and power. One effective technique is to use words that evoke a sense of scale, such as “colossal,” “towering,” or “expansive.” These words help to create a mental image of the sheer size of natural features, such as mountains, oceans, or forests. - The towering peaks of the Himalayas stretched up into the sky, their snow-capped summits lost in the clouds.

- The vast expanse of the ocean stretched out before us, as far as the eye could see.

- The ancient forest was a labyrinth of towering trees, their branches reaching up to the heavens.

Nature’s Interconnectedness Nature is a vast and intricate web of life, where every element plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of the ecosystem. Describing this interconnectedness requires capturing the relationships between different species, the interdependence of natural processes, and the impact of human activities on the environment. Symbiotic RelationshipsHighlight the mutually beneficial relationships between species, such as pollination, seed dispersal, and nutrient cycling. Explain how these interactions contribute to the survival and well-being of both species involved. - Describe the intricate relationship between bees and flowers, where bees collect nectar and pollen for food while aiding in the plant’s reproduction.

- Discuss the interdependence of birds and trees, where birds rely on trees for nesting and shelter, while trees benefit from the birds’ seed dispersal and insect control.

Food Webs and Trophic LevelsExplain the concept of food webs and trophic levels, illustrating how energy and nutrients flow through an ecosystem. Emphasize the interconnectedness of all organisms, from producers to consumers to decomposers. - Describe the role of phytoplankton as primary producers in marine ecosystems, providing the foundation for the entire food web.

- Explain how the decline of one species, such as a keystone predator, can have cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, affecting multiple trophic levels.

Biogeochemical CyclesDiscuss the interconnectedness of natural processes, such as the water cycle, carbon cycle, and nitrogen cycle. Explain how these cycles regulate the Earth’s climate, provide essential nutrients, and support life. - Describe the role of forests in the water cycle, capturing and releasing water vapor into the atmosphere.

- Explain how the carbon cycle links the atmosphere, oceans, and land, regulating the Earth’s temperature and providing the basis for fossil fuels.

Human ImpactDiscuss the impact of human activities on the interconnectedness of nature. Explain how pollution, deforestation, and climate change can disrupt natural relationships and threaten the stability of ecosystems. - Describe the effects of plastic pollution on marine life, entangling and harming animals.

- Explain how deforestation disrupts the water cycle and leads to soil erosion, affecting the entire ecosystem.

Sensory Overload and ImmersionNature has the power to overwhelm our senses and immerse us in its vastness. To create a sense of sensory overload and immersion in nature using descriptive language, writers can employ the following techniques: Sensory OverloadSensory overload is a technique that involves using multiple sensory details to create an overwhelming and immersive experience. By engaging several senses simultaneously, writers can transport readers into the natural world and evoke a vivid and visceral response.For example, consider the following passage: “The air was thick with the scent of pine needles, the sound of rushing water, and the feel of the wind on my skin. The sunlight filtered through the canopy, casting a dappled light on the forest floor. I could taste the crisp autumn air on my tongue, and the crunch of leaves beneath my feet filled my ears.” This passage uses a combination of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch to create a sense of sensory overload, immersing the reader in the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures of the natural world. EnvelopmentEnvelopment is a technique that describes the feeling of being fully surrounded by and enveloped in nature. By creating a sense of enclosure and immersion, writers can evoke a feeling of awe and wonder in readers.For example, consider the following passage: “I felt like I was being swallowed up by the forest, the trees towering over me like ancient guardians. The canopy of leaves formed a dense roof above my head, blocking out the sunlight and creating a sense of intimacy and seclusion. The air was heavy with the scent of damp earth and decaying leaves, and the only sound was the gentle rustling of the wind in the trees.” This passage uses imagery and sensory details to create a sense of envelopment, making the reader feel as if they are surrounded by the forest and enveloped in its sights, sounds, and smells. Awe-InspiringAwe-inspiring is a technique that conveys the overwhelming and awe-inspiring aspects of nature. By using language that evokes a sense of wonder and insignificance, writers can create a powerful emotional response in readers.For example, consider the following passage: “The sheer size and majesty of the mountains filled me with a sense of wonder and insignificance. I stood at the base of the towering peaks, my head tilted back as I gazed up at their snow-capped summits. The clouds drifted past, casting shadows on the mountain slopes, and the wind howled through the passes, carrying with it the sound of distant thunder.” This passage uses vivid imagery and sensory details to convey the awe-inspiring aspects of nature, creating a sense of wonder and insignificance in the reader. Nature’s Symbolism and Meaning Nature has the ability to evoke powerful emotions and associations, making it a rich source of symbolism in creative writing. Authors can use nature to convey deeper themes and meanings, exploring the human condition and the relationship between humanity and the natural world. For example, a stormy sea might represent inner turmoil or emotional upheaval, while a blooming flower could symbolize hope or renewal. Nature can also be used to represent human qualities, such as strength, resilience, or fragility. Nature as a Reflection of Human Emotion- A gentle breeze can convey a sense of peace and tranquility.

- A raging storm can symbolize anger, passion, or chaos.

- A wilting flower can represent sadness, loss, or vulnerability.

Nature’s Healing and Restorative Powers Nature possesses an inherent ability to heal and restore our minds and bodies. Spending time in natural environments has been shown to reduce stress, improve mood, and boost cognitive function. In this section, we will explore how to effectively describe the restorative effects of nature on the human psyche, providing examples and insights to enhance your writing. Natural Elements and Their Psychological BenefitsVarious natural elements offer specific psychological benefits. Consider incorporating the following into your writing: | Natural Element | Psychological Benefits |

|---|

| Sunlight | Boosts mood, improves sleep, and increases vitamin D levels. | | Water | Calms the nervous system, reduces stress, and promotes relaxation. | | Trees | Release phytoncides, which have antibacterial and stress-reducing effects. | | Flowers | Enhance mood, reduce anxiety, and promote a sense of well-being. | | Birdsong | Soothes the mind, improves sleep quality, and reduces stress levels. |

“Nature has a profound and healing effect on our well-being. It can reduce stress, improve mood, and boost cognitive function.” – Richard Louv, author of “Last Child in the Woods” Nature’s Threats and Fragility:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/24-profoundly-beautiful-words-describe-landscapes-and-nature-final-2ab7176631b948c7accbc62a69d1bb61.png) Nature, in its pristine beauty and intricate balance, faces myriad threats that jeopardize its well-being and the delicate equilibrium it sustains. Human activities, often driven by short-sightedness and unsustainable practices, pose significant risks to the natural world, leaving an imprint of destruction that threatens the very foundation of our planet’s ecosystems. Industrialization, urbanization, and the proliferation of consumer goods have led to an alarming increase in pollution levels. Pollutants such as greenhouse gases, toxic chemicals, and plastic waste contaminate the air, water, and soil, disrupting ecosystems and endangering countless species. Air pollution, caused by vehicle emissions and industrial processes, contributes to respiratory illnesses and climate change. Water pollution, resulting from industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and sewage discharge, contaminates water bodies, harming aquatic life and affecting human health. DeforestationThe relentless destruction of forests, driven by logging, agriculture, and urban expansion, is a major threat to biodiversity and the global ecosystem. Forests play a crucial role in regulating the climate, providing habitats for countless species, and supporting the livelihoods of millions of people. Deforestation disrupts the water cycle, exacerbates soil erosion, and contributes to climate change by releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Climate ChangeClimate change, driven by human activities that release greenhouse gases, is one of the most pressing threats to nature. Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events disrupt ecosystems, threaten species, and impact human societies. Coral reefs, essential for marine biodiversity, are particularly vulnerable to rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification. Conservation and ProtectionRecognizing the urgency of these threats, conservation efforts are vital to safeguard nature’s resilience and ensure its long-term survival. Protecting and restoring natural habitats, promoting sustainable practices, and reducing pollution are essential steps towards mitigating these threats. Individuals can contribute by adopting eco-friendly lifestyles, supporting conservation organizations, and advocating for policies that prioritize environmental protection. Nature’s Resilience and Adaptability Nature is not just beautiful; it’s also incredibly resilient and adaptable. It has the ability to withstand and overcome challenges, and even thrive in changing conditions. Nature’s AdaptabilityNature has an amazing ability to adapt to its surroundings. For example, some plants have evolved to thrive in harsh conditions, such as deserts or mountains. Some animals have developed camouflage to help them hide from predators. And some organisms have even learned to live in extreme environments, such as the deep sea or the Arctic. Nature’s ResilienceNature is also incredibly resilient. It can withstand natural disasters, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods. It can also recover from human-caused damage, such as pollution and deforestation. Nature’s resilience is a testament to its strength and adaptability. How to Describe Nature’s Resilience and AdaptabilityWhen describing nature’s resilience and adaptability, use descriptive language and vivid imagery. Focus on the details that show how nature is able to withstand and overcome challenges. For example, you might describe the way a tree bends in the wind but does not break, or the way a flower blooms in the middle of a barren landscape.You can also use personification to give nature human qualities. This can help to make nature seem more relatable and to emphasize its strength and resilience. For example, you might describe a river as “fighting” against its banks, or a mountain as “standing tall” in the face of adversity.Finally, don’t forget to evoke emotions in your writing. Nature’s resilience and adaptability can inspire a sense of awe and wonder. By capturing these emotions in your writing, you can help your readers to appreciate the beauty and strength of the natural world. Key Questions AnsweredHow do I choose the right sensory details to describe nature? Focus on details that evoke a specific sense or emotion. Use vivid language and avoid generic or overused descriptions. How can I use figurative language to enhance my nature descriptions? Metaphors, similes, and personification can bring nature to life and create a lasting impression. Use them sparingly and effectively. How do I convey the emotional impact of nature in my writing? Use language that reflects the emotions you want to evoke. Consider the tone and mood you’re aiming for and use descriptive language that creates the desired atmosphere.  3,000,000+ delegates 15,000+ clients 1,000+ locations - KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

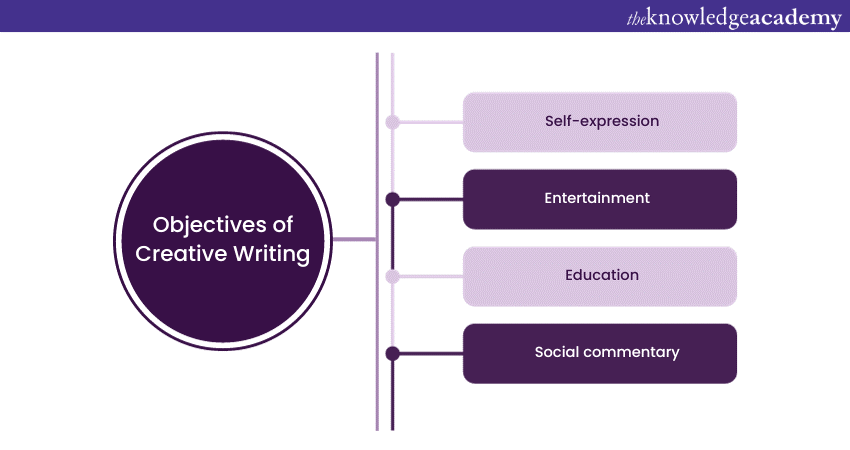

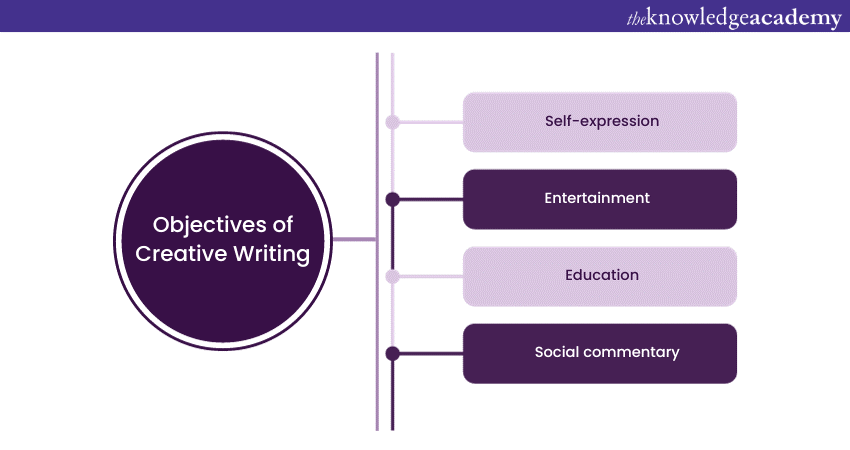

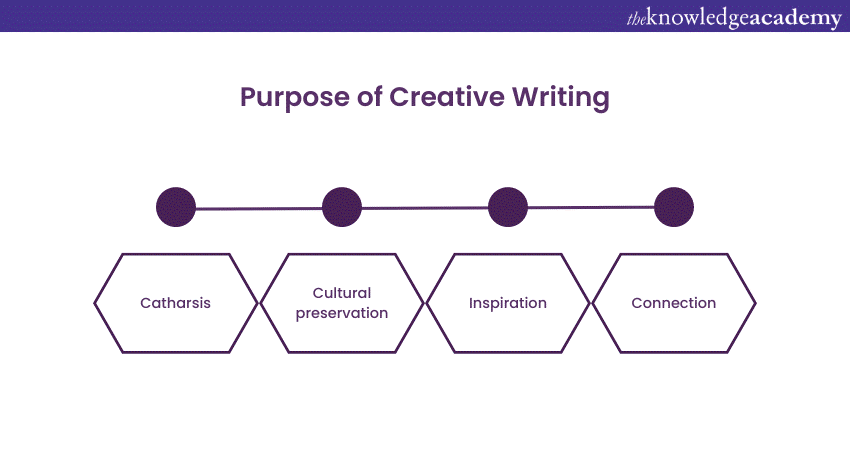

01344203999 Available 24/7  Objectives of Creative WritingDelve into the "Objectives of Creative Writing" and explore the multifaceted aims of this expressive art form. Uncover the diverse purposes, entertainment, education, and social commentary, that creative writing serves. Gain a deeper understanding of how creative writing transcends mere words, providing insight into the human experience.  Exclusive 40% OFF Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors. Share this Resource- Creative Writing Course

- Report Writing Course

- Attention Management Training

- Cake Decorating Getting Started Workshop

- Bag Making Course

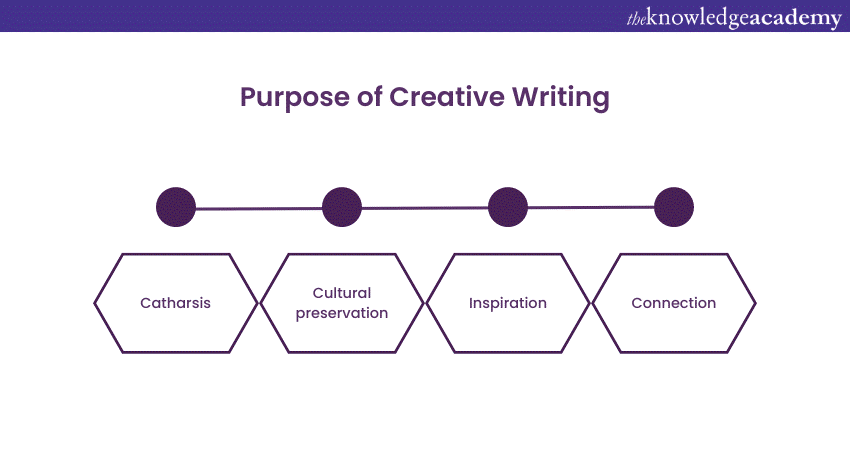

In this blog, we delve into the Objectives of Creative Writing and its purposes, shedding light on its significance in our lives. From the art of storytelling to the therapeutic release of emotions, Creative Writing is a dynamic and versatile discipline that has enchanted both writers and readers for generations. Table of C ontents 1) Objectives of Creative Writing a) Self-expression b) Entertainment c) Education d) Social commentary 2) Purpose of Creative Writing 3) Conclusion Objectives of Creative Writing Creative Writing serves as a versatile and dynamic form of expression, encompassing a range of objectives that go beyond mere storytelling. Here, we delve into the fundamental objectives that drive creative writers to craft their narratives and explore the depths of human creativity:  Self-expression Creative Writing is, at its core, a powerful means of self-expression. It provides writers with a unique canvas upon which they can paint the colours of their innermost thoughts, emotions, and experiences. This objective of Creative Writing is deeply personal and cathartic, as it allows individuals to articulate their inner worlds in ways that spoken language often cannot. Through the act of writing, authors can explore the complexities of their own psyche, giving shape and substance to feelings that might otherwise remain elusive. Whether it's capturing the euphoria of love, the depths of sorrow, or the intricacies of human relationships, Creative Writing serves as a conduit for unfiltered self-expression. Moreover, Creative Writing grants the freedom to experiment with different writing styles, tones, and literary devices, enabling writers to find their unique voices. In the process, it cultivates self-awareness, self-discovery, and a deeper understanding of one's own experiences. For many, the act of putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard is a therapeutic release, a way to make sense of the chaos within, and an avenue for personal growth and reflection. In essence, Creative Writing empowers individuals to share their inner narratives with the world, fostering connection and empathy among fellow readers who may find solace, resonance, or inspiration in the tales of others. Entertainment One of the primary and most recognisable objectives of Creative Writing is to entertain. Creative writers craft stories, poems, and essays that are designed to captivate readers, transporting them to different worlds, evoking emotions, and engaging their imaginations. At its heart, Creative Writing is the art of storytelling, and storytelling has been an integral part of human culture since time immemorial. Whether it's a thrilling mystery, a heartwarming romance, or a thought-provoking science fiction narrative, Creative Writing offers an escape from the ordinary into realms of fantasy, intrigue, and wonder. It weaves narratives with vivid imagery, compelling characters, and gripping plots, all working together to hold the reader's attention. Through Creative Writing, authors create emotional connections between the reader and the characters, fostering a sense of empathy and identification. As readers immerse themselves in a well-crafted story, they experience a wide range of emotions, from laughter to tears, joy to sorrow. It is this emotional journey that makes Creative Writing such a potent form of entertainment, offering readers a pleasurable escape from reality, a chance to explore new perspectives and a memorable experience that lingers long after the last page is turned.  Education Creative Writing is not only a source of entertainment but also a powerful educational tool. It engages writers in a process that goes beyond storytelling; it encourages research, critical thinking, and the development of effective communication skills. Writers often embark on extensive research journeys to create authentic settings, characters, and plots. This quest for accuracy and depth enriches their knowledge in various fields, ranging from history and science to culture and psychology. As they delve into their chosen topics, writers gain valuable insights and expand their intellectual horizons. Furthermore, Creative Writing teaches readers important life lessons and imparts knowledge. It introduces them to diverse perspectives, cultures, and experiences, fostering empathy and understanding. Reading well-crafted works can be an enlightening experience, challenging preconceptions and encouraging critical thinking. It also enhances vocabulary, language skills, and the ability to express thoughts and emotions effectively. In educational settings, Creative Writing nurtures creativity, encourages self-expression, and helps students develop essential communication and analytical skills. This educational objective of Creative Writing underscores its value as a holistic tool for personal and intellectual growth, making it an integral part of both formal and informal learning processes. Social commentary Creative Writing often serves as a potent medium for social commentary, embodying a powerful objective that transcends mere storytelling. Through the art of narrative, poets, novelists, and essayists alike can engage in meaningful discourse about society's values, issues, and challenges. Writers use their creative works to shine a light on important societal concerns, question norms, and provoke thought. They employ allegory, satire, symbolism, and other literary techniques to critique, challenge, or explore various aspects of the human condition and the world we inhabit. Whether addressing issues such as inequality, injustice, environmental crises, or political corruption, Creative Writing can be a catalyst for change. By portraying the complexities of real-life situations and characters, writers encourage readers to reflect on their own lives and the world around them. This introspection can lead to increased awareness and, ideally, inspire action to address pressing societal issues. In essence, the social commentary objective of Creative Writing underscores its role as a mirror reflecting the world's triumphs and flaws. It empowers writers to be advocates for change, storytellers with a purpose, and champions of social justice, ensuring that Creative Writing continues to be a powerful force for positive transformation in society. Tap into your creative potential with our Creative Writing Training – Get started today! Purpose of Creative Writing Creative Writing serves a multitude of purposes, making it a dynamic and invaluable art form. Beyond its objectives, Creative Writing plays a crucial role in our lives and society, contributing to personal growth, cultural preservation, inspiration, and connection.  Catharsis One of the profound and therapeutic purposes of Creative Writing is catharsis. This aspect of Creative Writing is deeply personal, as it offers writers a means to release pent-up emotions, confront inner turmoil, and find a sense of closure. Through the act of writing, individuals can explore their innermost thoughts and feelings in a safe and controlled environment. Whether it's grappling with grief, heartbreak, trauma, or any other emotional burden, Creative Writing provides an outlet to give shape and voice to those complex emotions. It allows writers to dissect their experiences, providing a space for self-reflection and healing. The process of transforming raw emotions into words can be both liberating and transformative. It can provide a sense of relief, allowing writers to gain insight into their emotional landscapes. Moreover, sharing these emotions through writing can foster connection and empathy among readers who may have experienced similar feelings or situations, creating a sense of community and understanding. Ultimately, catharsis through Creative Writing is a journey of self-discovery and emotional release, offering solace, healing, and a path towards personal growth and resilience. It highlights the profound impact of the written word in helping individuals navigate the complexities of their own inner worlds. Cultural preservation Creative Writing serves a noble purpose beyond personal expression and entertainment—it plays a vital role in cultural preservation. This objective of Creative Writing involves safeguarding the rich tapestry of human heritage, traditions, and stories for future generations. Cultures are defined by their narratives, folklore, and historical accounts. Creative writers, whether chroniclers of oral traditions or authors of historical fiction are the custodians of these invaluable cultural treasures. They document the stories passed down through generations, ensuring they are not lost to time. Through Creative Writing, cultures are celebrated, languages are preserved, and unique identities are immortalised. Folktales, myths, and legends are retold, keeping them relevant and alive. These narratives provide insights into the beliefs, values, and wisdom of a society, fostering a deeper understanding of its roots. Moreover, Creative Writing bridges cultural divides by sharing stories from diverse backgrounds, fostering empathy and appreciation for the richness of human experience. In this way, Creative Writing becomes a bridge across generations, connecting the past with the present and preserving the collective memory of humanity for a brighter future. Inspiration One of the transformative purposes of Creative Writing is to inspire others. It is a beacon that shines brightly, guiding aspiring writers and kindling the creative flames within them. Through the power of storytelling and the written word, Creative Writing has the remarkable ability to ignite the spark of imagination and motivation. Exceptional works of literature often leave an indelible mark on readers. They can evoke a sense of wonder, curiosity, and passion, motivating individuals to embark on their own creative journeys. Many renowned authors found their calling through the inspiration they drew from the words of others, perpetuating a beautiful cycle of creativity. Creative Writing serves as a testament to human potential, showcasing the boundless depths of imagination and the infinite possibilities of language. It encourages individuals to explore their unique perspectives, cultivate their voices, and craft stories that resonate with the human experience. For writers and readers alike, Creative Writing is a wellspring of inspiration, a reminder that the world of imagination is boundless and that the written word has the power to shape minds, hearts, and the course of history. Through the act of creation and the sharing of stories, Creative Writing continues to inspire generations to dream, create, and connect with the world in profound ways. Connection Creative Writing holds a remarkable purpose - it fosters connections. It serves as a bridge between authors and readers, offering a means of understanding, empathy, and human connection that transcends time, space, and cultural boundaries. When readers immerse themselves in a well-crafted story, they embark on an emotional journey alongside the characters. This shared experience creates a bond between the author and the reader as both parties navigate the complexities of the human condition together. Readers can see the world through the eyes of characters from diverse backgrounds and cultures, fostering empathy and understanding. Furthermore, Creative Writing connects individuals across generations. Literary classics, for example, allow us to connect with the thoughts and emotions of people who lived centuries ago. These timeless works offer insights into the universal aspects of the human experience, reminding us of our shared humanity. Creative Writing also has the power to connect people in the present. Through reading and discussion, individuals can form communities, share their interpretations, and engage in meaningful dialogue. Book clubs, literary events, and online forums all provide platforms for people to connect over their love for literature. Conclusion In conclusion, Creative Writing is a multifaceted art form with diverse objectives and purposes. From self-expression and entertainment to education, social commentary, catharsis, cultural preservation, inspiration, and connection, it enriches our lives in myriad ways. This timeless craft continues to captivate, inspire, and connect us, shaping our world through the power of words. Embark on your personal growth journey with our Personal Development Training – Explore now! Frequently Asked QuestionsUpcoming business skills resources batches & dates. Fri 27th Sep 2024 Fri 25th Oct 2024 Fri 22nd Nov 2024 Fri 27th Dec 2024 Fri 10th Jan 2025 Fri 14th Mar 2025 Fri 9th May 2025 Fri 11th Jul 2025 Fri 12th Sep 2025 Fri 14th Nov 2025 Get A QuoteWHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE? My employer By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry - Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this courseOur biggest summer sale.  We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry. By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry. We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements. Or select from our popular topics - ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- ISO 9001 Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch. Fill out your contact details below Thank you for your enquiry! One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements. Back to Course Information Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements. * WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE? Preferred Contact Method No preference Back to course information Fill out your training details below Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are. HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING? HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED? Online Instructor-led Online Self-paced WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE? Next 2 - 4 months WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING? Looking for some information Looking for a discount I want to book but have questions One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements. Your privacy & cookies!Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy . We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.  - Kelvin Smith Library

- Creative Writing

- Research Guides

- Creative Writing Resources

Research Services Librarian Get Online Help- KSL Ask A Librarian Information on how to get help by email, phone, & chat.

Reminder: Online Access- Library resources require going through CWRU Single Sign-On.

- The best method is to follow links from the library website.

- When logged in and a browser window is not closed, access should continue from resource to resource.

- Remember to close your browser when done.

- CWRU Libraries Discovery & Authentication by Brian Gray Last Updated Jan 28, 2022 266 views this year

Research Guide for Creative WritingWelcome to the Creative Writing Research Guide! Within this guide, you will find recommended resources for studying how to write creative works, including poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction . The Creative Writing Resources page looks broadly at the art and practice of writing, but if you want to narrow it to a specific type, the By Type page divides them up and provides tailored resources for each category. Related Guides for Creative WritingOther research guides related to Creative Writing: - English by Nicole Clarkson Last Updated Aug 30, 2024 349 views this year

- Poetry by Nicole Clarkson Last Updated Aug 16, 2024 208 views this year

- Film Studies by Nicole Clarkson Last Updated Aug 16, 2024 115 views this year

- Shakespeare by Nicole Clarkson Last Updated Jul 29, 2024 239 views this year

Research Tools- KSL Research Databases An A-Z list of available databases & related resources.

CWRU Libraries Discovery- Next: Creative Writing Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 30, 2024 12:53 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.case.edu/creative_writing

What is Nature Writing?Definition and Examples - An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator 's encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject. "In critical practice," says Michael P. Branch, "the term 'nature writing' has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice , and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay . Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda" ("Before Nature Writing," in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism , ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001). Examples of Nature Writing:- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:- "Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . .. "The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs , literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . . "In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir's words, that 'the money changers were in the temple' continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature's wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs. "Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing." (J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing . Norton, 2002)

"Human Writing . . . in Nature"- "By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really 'nature writing' anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau's] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There's something to celebrate." (David Gessner, "Sick of Nature." The Boston Globe , Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer- "I do not believe that the solution to the world's ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature "Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a 'nature writer' is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that 'nature never did betray the heart that loved her.' Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. 'Nature writing' is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically 'nature writing' does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things." (Joseph Wood Krutch, "Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer." New York Herald Tribune Book Review , 1952)

- Thoreau's 'Walden': 'The Battle of the Ants'

- What Is Style in Writing?

- The Title in Composition

- A Fable by Mark Twain

- 20 Quotes on the Nature of Writing

- What's the Secret of Good Writing?

- Prewriting for Composition

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- What Is Prose?

- Definition and Examples of Online Writing

- Creative Nonfiction

- Best Practices for Business Writing

- Unity in Composition

- Tips on Great Writing: Setting the Scene

- Invention (Composition and Rhetoric)

Nature Writing Examplesby Lisa Hiton  From the essays of Henry David Thoreau, to the features in National Geographic , nature writing has bridged the gap between scientific articles about environmental issues and personal, poetic reflections on the natural world. This genre has grown since Walden to include nature poetry, ecopoetics, nature reporting, activism, fiction, and beyond. We now even have television shows and films that depict nature as the central figure. No matter the genre, nature writers have a shared awe and curiosity about the world around us—its trees, creatures, elements, storms, and responses to our human impact on it over time. Whether you want to report on the weather, write poems from the point of view of flowers, or track your journey down a river in your hometown, your passion for nature can manifest in many different written forms. As the world turns and we transition between seasons, we can reflect on our home, planet Earth, with great dedication to description, awe, science, and image. Journal Examples: Keeping Track of Your TracksOne of the many lost arts of our modern time is that of journaling. While keeping a journal is a beneficial practice for all, it is especially crucial to nature writers. John A. Murray , author of Writing About Nature: A Creative Guide , begins his study of the nature writing practice with the importance of journaling: Nature writers may rely on journals more consistently than novelists and poets because of the necessity of describing long-term processes of nature, such as seasonal or environmental changes, in great detail, and of carefully recording outdoor excursions for articles and essays[…] The important thing, it seems to me, is not whether you keep journals, but, rather, whether you have regular mechanisms—extended letters, telephone calls to friends, visits with confidants, daily meditation, free-writing exercises—that enable you to comprehensively process events as they occur. But let us focus in this section on journals, which provide one of the most common means of chronicling and interpreting personal history. The words journal and journey share an identical root and common history. Both came into the English language as a result of the Norman Victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. For the next three hundred years, French was the chief language of government, religion, and learning in England. The French word journie, which meant a day’s work or a day’s travel, was one of the many words that became incorporated into English at the time[…]The journal offers the writer a moment of rest in that journey, a sort of roadside inn along the highway. Here intellect and imagination are alone with the blank page and composition can proceed with an honesty and informality often precluded in more public forms of expression. As a result, several important benefits can accrue: First, by writing with unscrutinized candor and directness on a particular subject, a person can often find ways to write more effectively on the same theme elsewhere. Second, the journal, as a sort of unflinching mirror, can remind the author of the importance of eliminating self-deception and half-truths in thought and writing. Third, the journal can serve as a brainstorming mechanism to explore new topics, modes of thought, or types of writing that otherwise would remain undiscovered or unexamined. Fourth, the journal can provide a means for effecting a catharsis on subjects too personal for publication even among friends and family. (Murray, 1-2) A dedicated practice of documenting your day, observing what is around you, and creating your own field guide of the world as you encounter it will help strengthen your ability to translate it all to others and help us as a culture learn how to interpret what is happening around us. Writing About Nature: A Creative Guide by John A. Murray : Murray’s book on nature writing offers hopeful writers a look at how nature writers keeps journals, write essays, incorporate figurative language, use description, revise, research, and more. Botanical Shakespeare: An Illustrated Compendium of All the Flowers, Fruits, Herbs, Trees, Seeds, and Grasses Cited by the World’s Greatest Playwright by Gerit Quealy and Sumie Hasegawa Collins: Helen Mirren’s foreword to the book describes it as “the marriage of Shakespeare’s words about plants and the plants themselves.” This project combines the language of Shakespeare with the details of the botanicals found throughout his works—Quealy and Hasegawa bring us a literary garden ripe with flora and fauna puns and intellectual snark. - What new vision of Shakespeare is provided by approaching his works through the lens of nature writing and botanicals?

- Latin and Greek terms and roots continue to be very important in the world of botanicals. What do you learn from that etymology throughout the book? How does it impact symbolism in Shakespeare’s works?

- Annotate the book using different colored highlighters. Seek out description in one color, interpretation in another, and you might even look for literary echoes using a third. How do these threads braid together?

The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland by Nan Shepherd : The Living Mountain is Shepherd’s account of exploring the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland. Part of Britain’s Arctic, Shepherd encounters ravenous storms, clear views of the aurora borealis, and deep snows during the summer. She spent hundreds of days exploring the mountains by foot. - These pages were written during the last years of WWII and its aftermath. How does that backdrop inform Shepherd’s interpretation of the landscape?

- The book is separated into twelve chapters, each dedicated to a specific part of life in the Cairngorms. How do these divisions guide the writing? Is she able to keep these elements separate from each other? In writing? In experiencing the land?

- Many parts of the landscape Shepherd observes would be expected in nature writing—mountains, weather, elements, animals, etc. How does Shepherd use language and tone to write about these things without using stock phrasing or clichéd interpretations?

Birds Art Life: A Year of Observation by Kyo Maclear : Even memoir can be delivered through nature writing as we see in Kyo Maclear’s poetic book, Birds Art Life . The book is an account of a year in her life after her father has passed away. And just as Murray and Thoreau would advise, journaling those days and the symbols in them led to a whole book—one that delicately and profoundly weaves together the nature of life—of living after death—and how art can collide with that nature to get us through the hours. - How does time pass throughout the book? What techniques does Maclear employ to move the reader in and out of time?

- How does grief lead Maclear into art? Philosophy? Nature? Objects?

- The book is divided into the months of the year. Why does Maclear divide the book this way?

- What do you make of the subtitles?

Is time natural? Describe the relationship between humans and time in nature. So dear writers, take to these pages and take to the trails in nature around you. Journal your way through your days. Use all of your senses to take a journey in nature. Then, journal to make a memory of your time in the world. And give it all away to the rest of us, in words. Lisa Hiton is an editorial associate at Write the World . She writes two series on our blog: The Write Place where she comments on life as a writer, and Reading like a Writer where she recommends books about writing in different genres. She’s also the interviews editor of Cosmonauts Avenue and the poetry editor of the Adroit Journal .  Share this post: Similar Blogs What is Environmental Writing?As our environment becomes increasingly impacted by humans, our relationship to the...  Advice for Fantasy Writing and Getting Published, with Guest Judge Tomi Adeyemi!Writing in the science fiction or fantasy genre offers a unique opportunity to explore our reality...  Nature & Environmental Poetry Competition 2023 Winners Announced!From the urbanization of a natural space to a forest still haunted by the effects of fire, our ... Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. - View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 27 February 2023

The role of memory in creative ideation- Mathias Benedek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6258-4476 1 ,

- Roger E. Beaty ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6114-5973 2 ,

- Daniel L. Schacter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2460-6061 3 , 4 &

- Yoed N. Kenett ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3872-7689 5

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 2 , pages 246–257 ( 2023 ) Cite this article 2190 Accesses 47 Citations 67 Altmetric Metrics details - Human behaviour

- Neuroscience

Creativity reflects the remarkable human capacity to produce novel and effective ideas. Empirical work suggests that creative ideas do not just emerge out of nowhere but typically result from goal-directed memory processes. Specifically, creative ideation is supported by controlled retrieval, involves semantic and episodic memory, builds on processes used in memory construction and differentially recruits memory at different stages in the creative process. In this Perspective, we propose a memory in creative ideation (MemiC) framework that describes how creative ideas arise across four distinguishable stages of memory search, candidate idea construction, novelty evaluation and effectiveness evaluation. We discuss evidence supporting the contribution of semantic and episodic memory to each stage of creative ideation. The MemiC framework overcomes the shortcomings of previous creativity theories by accounting for the controlled, dynamic involvement of different memory systems across separable ideation stages and offers a clear agenda for future creativity research. This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution Access optionsSubscribe to this journal Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles 55,14 € per year only 4,60 € per issue Buy this article - Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF