- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Levels of evidence in research

- 5 minute read

- 115.7K views

Table of Contents

Level of evidence hierarchy

When carrying out a project you might have noticed that while searching for information, there seems to be different levels of credibility given to different types of scientific results. For example, it is not the same to use a systematic review or an expert opinion as a basis for an argument. It’s almost common sense that the first will demonstrate more accurate results than the latter, which ultimately derives from a personal opinion.

In the medical and health care area, for example, it is very important that professionals not only have access to information but also have instruments to determine which evidence is stronger and more trustworthy, building up the confidence to diagnose and treat their patients.

5 levels of evidence

With the increasing need from physicians – as well as scientists of different fields of study-, to know from which kind of research they can expect the best clinical evidence, experts decided to rank this evidence to help them identify the best sources of information to answer their questions. The criteria for ranking evidence is based on the design, methodology, validity and applicability of the different types of studies. The outcome is called “levels of evidence” or “levels of evidence hierarchy”. By organizing a well-defined hierarchy of evidence, academia experts were aiming to help scientists feel confident in using findings from high-ranked evidence in their own work or practice. For Physicians, whose daily activity depends on available clinical evidence to support decision-making, this really helps them to know which evidence to trust the most.

So, by now you know that research can be graded according to the evidential strength determined by different study designs. But how many grades are there? Which evidence should be high-ranked and low-ranked?

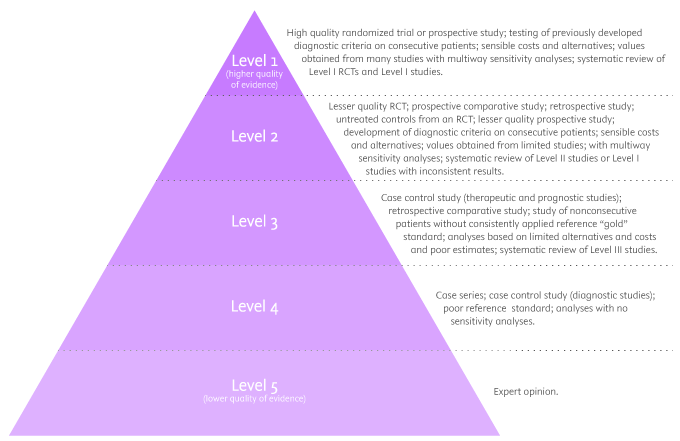

There are five levels of evidence in the hierarchy of evidence – being 1 (or in some cases A) for strong and high-quality evidence and 5 (or E) for evidence with effectiveness not established, as you can see in the pyramidal scheme below:

Level 1: (higher quality of evidence) – High-quality randomized trial or prospective study; testing of previously developed diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from many studies with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level I RCTs and Level I studies.

Level 2: Lesser quality RCT; prospective comparative study; retrospective study; untreated controls from an RCT; lesser quality prospective study; development of diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients; sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from limited stud- ies; with multiway sensitivity analyses; systematic review of Level II studies or Level I studies with inconsistent results.

Level 3: Case-control study (therapeutic and prognostic studies); retrospective comparative study; study of nonconsecutive patients without consistently applied reference “gold” standard; analyses based on limited alternatives and costs and poor estimates; systematic review of Level III studies.

Level 4: Case series; case-control study (diagnostic studies); poor reference standard; analyses with no sensitivity analyses.

Level 5: (lower quality of evidence) – Expert opinion.

By looking at the pyramid, you can roughly distinguish what type of research gives you the highest quality of evidence and which gives you the lowest. Basically, level 1 and level 2 are filtered information – that means an author has gathered evidence from well-designed studies, with credible results, and has produced findings and conclusions appraised by renowned experts, who consider them valid and strong enough to serve researchers and scientists. Levels 3, 4 and 5 include evidence coming from unfiltered information. Because this evidence hasn’t been appraised by experts, it might be questionable, but not necessarily false or wrong.

Examples of levels of evidence

As you move up the pyramid, you will surely find higher-quality evidence. However, you will notice there is also less research available. So, if there are no resources for you available at the top, you may have to start moving down in order to find the answers you are looking for.

- Systematic Reviews: -Exhaustive summaries of all the existent literature about a certain topic. When drafting a systematic review, authors are expected to deliver a critical assessment and evaluation of all this literature rather than a simple list. Researchers that produce systematic reviews have their own criteria to locate, assemble and evaluate a body of literature.

- Meta-Analysis: Uses quantitative methods to synthesize a combination of results from independent studies. Normally, they function as an overview of clinical trials. Read more: Systematic review vs meta-analysis .

- Critically Appraised Topic: Evaluation of several research studies.

- Critically Appraised Article: Evaluation of individual research studies.

- Randomized Controlled Trial: a clinical trial in which participants or subjects (people that agree to participate in the trial) are randomly divided into groups. Placebo (control) is given to one of the groups whereas the other is treated with medication. This kind of research is key to learning about a treatment’s effectiveness.

- Cohort studies: A longitudinal study design, in which one or more samples called cohorts (individuals sharing a defining characteristic, like a disease) are exposed to an event and monitored prospectively and evaluated in predefined time intervals. They are commonly used to correlate diseases with risk factors and health outcomes.

- Case-Control Study: Selects patients with an outcome of interest (cases) and looks for an exposure factor of interest.

- Background Information/Expert Opinion: Information you can find in encyclopedias, textbooks and handbooks. This kind of evidence just serves as a good foundation for further research – or clinical practice – for it is usually too generalized.

Of course, it is recommended to use level A and/or 1 evidence for more accurate results but that doesn’t mean that all other study designs are unhelpful or useless. It all depends on your research question. Focusing once more on the healthcare and medical field, see how different study designs fit into particular questions, that are not necessarily located at the tip of the pyramid:

- Questions concerning therapy: “Which is the most efficient treatment for my patient?” >> RCT | Cohort studies | Case-Control | Case Studies

- Questions concerning diagnosis: “Which diagnose method should I use?” >> Prospective blind comparison

- Questions concerning prognosis: “How will the patient’s disease will develop over time?” >> Cohort Studies | Case Studies

- Questions concerning etiology: “What are the causes for this disease?” >> RCT | Cohort Studies | Case Studies

- Questions concerning costs: “What is the most cost-effective but safe option for my patient?” >> Economic evaluation

- Questions concerning meaning/quality of life: “What’s the quality of life of my patient going to be like?” >> Qualitative study

Find more about Levels of evidence in research on Pinterest:

17 March 2021 – Elsevier’s Mini Program Launched on WeChat Brings Quality Editing Straight to your Smartphone

Professor anselmo paiva: using computer vision to tackle medical issues with a little help from elsevier author services, you may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Levels of Evidence and Study Design: Levels of Evidence

Levels of evidence.

- Study Design

- Study Design by Question Type

- Rating Systems

This is a general set of levels to aid in critically evaluating evidence. It was adapted from the model presented in the book, Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019). Some specialties may have adopted a slightly different and/or smaller set of levels.

Evidence from a clinical practice guideline based on systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Is this is not available, then evidence from a systematic review or meta-analysis of random controlled trials.

Evidence from randomized controlled studies with good design.

Evidence from controlled trials that have good design but are not randomized.

Evidence from case-control and cohort studies with good design.

Evidence from systematic reviews of qualitative and descriptive studies.

Evidence from qualitative and descriptive studies.

Evidence from the opinion of authorities and/or the reports of expert committees.

Evidence Pyramid

The pyramid below is a hierarchy of evidence for quantitative studies. It shows the hierarchy of studies by study design; starting with secondary and reappraised studies, then primary studies, and finally reports and opinions, which have no study design. This pyramid is a simplified, amalgamation of information presented in the book chapter “Evidence-based decision making” (Forest et al., 2019) and book Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019).

Evidence Table for Nursing

Advocate Health - Midwest provides system-wide evidence based practice resources. The Nursing Hub* has an Evidence-Based Quality Improvement (EBQI) Evidence Table , within the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Resource. It also includes information on evidence type, and a literature synthesis table.

*The Nursing Hub requires access to the Advocate Health - Midwest SharePoint platform.

Forrest, J. L., Miller, S. A., Miller, G. W., Elangovan, S., & Newman, M. G. (2019). Evidence-based decision making. In M. G. Newman, H. H. Takei, P. R. Klokkevold, & F. A. Carranza (Eds.), Newman and Carranza's clinical periodontology (13th ed., pp. 1-9.e1). Elsevier.

- Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Study Design >>

- Last Updated: Dec 29, 2023 2:03 PM

- URL: https://library.aah.org/guides/levelsofevidence

Systematic Reviews

- Levels of Evidence

- Evidence Pyramid

- Joanna Briggs Institute

The evidence pyramid is often used to illustrate the development of evidence. At the base of the pyramid is animal research and laboratory studies – this is where ideas are first developed. As you progress up the pyramid the amount of information available decreases in volume, but increases in relevance to the clinical setting.

Meta Analysis – systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

Systematic Review – summary of the medical literature that uses explicit methods to perform a comprehensive literature search and critical appraisal of individual studies and that uses appropriate st atistical techniques to combine these valid studies.

Randomized Controlled Trial – Participants are randomly allocated into an experimental group or a control group and followed over time for the variables/outcomes of interest.

Cohort Study – Involves identification of two groups (cohorts) of patients, one which received the exposure of interest, and one which did not, and following these cohorts forward for the outcome of interest.

Case Control Study – study which involves identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and patients without the same outcome (controls), and looking back to see if they had the exposure of interest.

Case Series – report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved.

- Levels of Evidence from The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

- The JBI Model of Evidence Based Healthcare

- How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence From the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia. Book must be downloaded; not available to read online.

When searching for evidence to answer clinical questions, aim to identify the highest level of available evidence. Evidence hierarchies can help you strategically identify which resources to use for finding evidence, as well as which search results are most likely to be "best".

Image source: Evidence-Based Practice: Study Design from Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives. This work is licensed under a Creativ e Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

The hierarchy of evidence (also known as the evidence-based pyramid) is depicted as a triangular representation of the levels of evidence with the strongest evidence at the top which progresses down through evidence with decreasing strength. At the top of the pyramid are research syntheses, such as Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews, the strongest forms of evidence. Below research syntheses are primary research studies progressing from experimental studies, such as Randomized Controlled Trials, to observational studies, such as Cohort Studies, Case-Control Studies, Cross-Sectional Studies, Case Series, and Case Reports. Non-Human Animal Studies and Laboratory Studies occupy the lowest level of evidence at the base of the pyramid.

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Locating Systematic Reviews >>

- Getting Started

- What is a Systematic Review?

- Locating Systematic Reviews

- Searching Systematically

- Developing Answerable Questions

- Identifying Synonyms & Related Terms

- Using Truncation and Wildcards

- Identifying Search Limits/Exclusion Criteria

- Keyword vs. Subject Searching

- Where to Search

- Search Filters

- Sensitivity vs. Precision

- Core Databases

- Other Databases

- Clinical Trial Registries

- Conference Presentations

- Databases Indexing Grey Literature

- Web Searching

- Handsearching

- Citation Indexes

- Documenting the Search Process

- Managing your Review

Research Support

- Last Updated: Aug 6, 2024 10:17 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucdavis.edu/systematic-reviews

Understanding Evidence Levels in Evidence-Based Medicine: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals

- Teaching Hospital Badulla University of Colombo Sri Lanka

- Teaching Hospital, Badulla, SriLanka

- Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- PLAST RECONSTR SURG

- Sandra V. Spilson

- James E McCarthy

- Patricia B Burns

- Kevin C Chung

- DeLaine Schmitz

- Loren Lipworth

- Robert E. Tarone

- Joseph K. McLaughlin

- Kevin C. Chung

- Ashwin N Ram

- INT J CANCER

- D L Sackett

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Evidence-Based Medicine

- Finding the Evidence

- eJournals for EBM

Levels of Evidence

- JAMA Users' Guides

- Tutorials (Learning EBM)

- Web Resources

Resources That Rate The Evidence

- ACP Smart Medicine

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- Clinical Evidence

- Cochrane Library

- Health Services/Technology Assessment Texts (HSTAT)

- PDQ® Cancer Information Summaries from NCI

- Trip Database

Critically Appraised Individual Articles

- Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Evidence-Based Dentistry

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice

Grades of Recommendation

| | | |

| A | 1a | Systematic review of (homogeneous) randomized controlled trials |

| A | 1b | Individual randomized controlled trials (with narrow confidence intervals) |

| B | 2a | Systematic review of (homogeneous) cohort studies of "exposed" and "unexposed" subjects |

| B | 2b | Individual cohort study / low-quality randomized control studies |

| B | 3a | Systematic review of (homogeneous) case-control studies |

| B | 3b | Individual case-control studies |

| C | 4 | Case series, low-quality cohort or case-control studies |

| D | 5 | Expert opinions based on non-systematic reviews of results or mechanistic studies |

Critically-appraised individual articles and synopses include:

Filtered evidence:

- Level I: Evidence from a systematic review of all relevant randomized controlled trials.

- Level II: Evidence from a meta-analysis of all relevant randomized controlled trials.

- Level III: Evidence from evidence summaries developed from systematic reviews

- Level IV: Evidence from guidelines developed from systematic reviews

- Level V: Evidence from meta-syntheses of a group of descriptive or qualitative studies

- Level VI: Evidence from evidence summaries of individual studies

- Level VII: Evidence from one properly designed randomized controlled trial

Unfiltered evidence:

- Level VIII: Evidence from nonrandomized controlled clinical trials, nonrandomized clinical trials, cohort studies, case series, case reports, and individual qualitative studies.

- Level IX: Evidence from opinion of authorities and/or reports of expert committee

Two things to remember:

1. Studies in which randomization occurs represent a higher level of evidence than those in which subject selection is not random.

2. Controlled studies carry a higher level of evidence than those in which control groups are not used.

Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT)

- SORT The American Academy of Family Physicians uses the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) to label key recommendations in clinical review articles. In general, only key recommendations are given a Strength-of-Recommendation grade. Grades are assigned on the basis of the quality and consistency of available evidence.

- << Previous: eJournals for EBM

- Next: JAMA Users' Guides >>

- Last Updated: Jan 25, 2024 4:15 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stonybrook.edu/evidence-based-medicine

- Request a Class

- Hours & Locations

- Ask a Librarian

- Special Collections

- Library Faculty & Staff

Library Administration: 631.632.7100

- Stony Brook Home

- Campus Maps

- Web Accessibility Information

- Accessibility Barrier Report Form

Comments or Suggestions? | Library Webmaster

Except where otherwise noted, this work by SBU Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Hierarchy of Scientific Evidence: Understanding the Levels

This article provides an in-depth exploration of the hierarchy of scientific evidence , emphasising its significance in research interpretation and application.

It examines different hierarchical levels, highlights the contributions of Guyatt and Sackett, and discusses the GRADE approach.

It also compares various grading systems and guidelines used in assessing evidence-based practices.

This knowledge is critical for researchers, policy makers, and students in understanding and effectively utilising scientific evidence.

Key Takeaways

- Levels of evidence are a hierarchical system for classifying evidence in Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM).

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are ranked at the highest level of evidence due to their unbiased design.

- Case series or expert opinions are ranked at the lowest level of evidence due to potential bias.

- The GRADE approach rates the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Exploring the Concept of Hierarchy of Evidence

Examining the concept of hierarchy of evidence helps in understanding the varying degrees of reliability and validity of scientific studies, ranging from randomised controlled trials at the top to expert opinions at the bottom.

The hierarchy of scientific evidence is a system used to rank the strength of research findings. At the top are systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which provide the most reliable evidence. RCTs are followed in the hierarchy by well-designed non-randomised controlled studies.

Lower levels of scientific evidence include observational studies and case series. The lowest level of evidence is derived from expert opinions and anecdotal evidence.

Understanding this hierarchy is crucial in assessing the credibility and applicability of research in clinical decision-making.

Understanding the GRADE Approach

The GRADE Approach, an advanced tool for evaluating the quality of evidence in healthcare, prioritises transparency and strives for simplicity, making it a fundamental asset in the realm of evidence-based medicine. This approach, endorsed by over 100 organisations globally, provides a systematic and transparent method of appraising evidence.

- Quality of Evidence Assessment : GRADE classifies evidence quality into four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low. The higher the quality, the more we can trust the evidence.

- Strength of Recommendations : GRADE distinguishes between strong and weak recommendations, bringing clarity to decision-making processes.

- Consideration of Values and Preferences : GRADE acknowledges the role of patient values and preferences, ensuring a patient-centric approach to healthcare. This multifaceted approach enhances the credibility and applicability of research findings in clinical practice.

An Insight Into the Guyatt and Sackett Hierarchy

Both Guyatt and Sackett introduced a seminal hierarchy of evidence in 1995, which placed systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials at the pinnacle, and relegated case reports to the bottom, thereby revolutionising the approach to evidence-based medicine.

This groundbreaking work stressed the importance of rigorous scientific methodology in medical research and practice. The hierarchy underscores the need for high-quality experimental designs to yield reliable evidence.

The emphasis on systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlights the value of consolidating data from multiple studies. Conversely, the low rank of case reports reflects their inherent limitations, including potential bias and lack of generalizability.

This hierarchy has profoundly shaped the field of evidence-based medicine, promoting the use of robust, high-quality evidence in clinical decision-making.

Comparing the Saunders Et Al. Protocol and Khan Et Al. Protocol

Diving into a comparative analysis, we find that the Saunders et al. protocol bases its categorisation of interventions on research design, potential harm, and general acceptance, while the Khan et al. protocol puts a stronger emphasis on the use of randomised designs and intention-to-treat analysis.

Three distinct differences emerge:

- Emphasis on Research Design: The Saunders protocol accommodates a wide range of research designs, while Khan’s protocol prefers randomised designs, thus narrowing its range of acceptable studies.

- Consideration of Potential Harm: Saunders et al. consider potential harm in their categorisation, a factor not prominently accounted for in Khan et al.’s protocol.

- Acceptance in the Scientific Community: Saunders et al. consider general acceptance among scientists, feeding into a more holistic approach. Conversely, Khan et al. focus primarily on rigorous, statistically backed evidence.

A Look at Different Grading Systems and Guidelines

Assessing different grading systems and guidelines is crucial for understanding their efficacy in evaluating research quality, and it allows for a comparative analysis between approaches such as GRADEpro, GRADE guidelines, and BMJ Best Practice.

GRADEpro and GRADE guidelines, collectively known as GRADE, provide a systematic and transparent means of appraising evidence, widely recognised and endorsed by over 100 health organisations worldwide.

Meanwhile, BMJ Best Practice offers a comprehensive solution integrating the latest research evidence, guidelines, and expert opinion. It facilitates evidence-based decisions in clinical practice.

However, each system has its strengths and weaknesses, making the choice largely dependent on the context and specific requirements of each research project.

A thorough understanding of these grading systems is essential to their effective utilisation.

Sign up for our Publishing Newsletter and start delivering creative, concise content

Frequently asked questions, how does the hierarchy of scientific evidence affect scientific content.

The hierarchy of scientific evidence significantly influences scientific content by determining the credibility and weight of the information presented. High-quality content often relies on sources from the upper levels of the hierarchy, such as systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials, which are considered more reliable due to their rigorous methodology and comprehensive analysis. This hierarchy guides researchers, publishers, and decision-makers in evaluating the strength of evidence behind scientific claims, ensuring that the most robust, well-supported findings are highlighted and disseminated. Consequently, it shapes the development of scientific theories, the formulation of guidelines, and the direction of future research, prioritizing evidence-based knowledge and practices in the scientific community.

How Are Different Types of Studies Weighted in the Hierarchy of Scientific Evidence?

In the hierarchy of scientific evidence, different types of studies are weighted based on their design and validity. Randomised controlled trials are typically at the top, while observational studies and expert opinions rank lower.

How Does the GRADE Approach Differ From Other Methods of Evaluating Scientific Evidence?

The GRADE approach to evaluating scientific evidence differs from other methods by offering a systematic and transparent process. It assesses the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation, widely endorsed by over 100 organisations globally.

What Are the Key Components of the Guyatt and Sackett Hierarchy?

The Guyatt and Sackett hierarchy is a system that categorises scientific evidence by its strength. It places systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials at the top, followed by lesser reliability evidence such as case reports.

How Do the Saunders Et Al. Protocol and the Khan Et Al. Protocol Compare in Terms of Research Design and Analysis?

The Saunders et al. protocol categorises interventions based on research design, potential harm, and general acceptance. In contrast, the Khan et al. protocol emphasises randomised designs and intention-to-treat analysis for a rigorous approach.

Can You Provide Examples of Different Grading Systems and Guidelines Used in Evidence-Based Practices and Medicine?

Examples of grading systems used in evidence-based medicine include GRADEpro, GRADE guidelines, BMJ Best Practice, and User’s guides to the medical literature. The NREPP Review Criteria assesses evidence-based practices and programs.

How Does the Hierarchy of Scientific Evidence Relate to Life Science Content?

In the realm of life sciences content , the hierarchy of scientific evidence ensures that content, especially impacting health and medical practices, is grounded in the most reliable studies. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials are prioritized for their thorough analysis and reduced bias, influencing publications, clinical guidelines, and policy-making. This ensures life science content is accurate, rigorously tested, and supports informed healthcare decisions.

In conclusion, understanding the hierarchy of scientific evidence is crucial for interpreting and applying research outcomes. This knowledge enhances the interpretation of methodological quality, results consistency, and subject relevance.

The contributions of Guyatt, Sackett, and the GRADE approach significantly influence this field. Grading systems and guidelines further aid in assessing evidence-based practices, underscoring the indispensability of understanding the levels of scientific evidence for researchers, policy makers, and students alike.

Discover the ScioWire research newsfeed: summarised scientific knowledge ready to digest.

- Library databases

- Library website

Evidence-Based Research: Evidence Types

Introduction.

Not all evidence is the same, and appraising the quality of the evidence is part of evidence-based practice research. The hierarchy of evidence is typically represented as a pyramid shape, with the smaller, weaker and more abundant research studies near the base of the pyramid, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top with higher validity but a more limited range of topics.

Several versions of the evidence pyramid have evolved with different interpretations, but they are all comprised of the types of evidence discussed on this page. Walden's Nursing 6052 Essentials of Evidence-Based Practice class currently uses a simplified adaptation of the Johns Hopkins model .

Evidence Levels:

Level I: Experimental, randomized controlled trial (RCT), systematic review RTCs with or without meta-analysis

Level II: Quasi-experimental studies, systematic review of a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, or quasi-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis

Level III: Nonexperimental, systematic review of RCTs, quasi-experimental with/without meta-analysis, qualitative, qualitative systematic review with/without meta-synthesis (see Daly 2007 for a sample qualitative hierarchy)

Level IV : Respected authorities’ opinions, nationally recognized expert committee or consensus panel reports based on scientific evidence

Level V: Literature reviews, quality improvement, program evaluation, financial evaluation, case reports, nationally recognized expert(s) opinion based on experiential evidence

Systematic review

What is a systematic review.

A systematic review is a type of publication that addresses a clinical question by analyzing research that fits certain explicitly-specified criteria. The criteria for inclusion is usually based on research from clinical trials and observational studies. Assessments are done based on stringent guidelines, and the reviews are regularly updated. These are usually considered one of the highest levels of evidence and usually address diagnosis and treatment questions.

Benefits of Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews refine and reduce large amounts of data and information into one document, effectively summarizing the evidence to support clinical decisions. Since they are typically undertaken by a entire team of experts, they can take months or even years to complete, and must be regularly updated. The teams are usually comprised of content experts, an experienced searcher, a bio-statistician, and a methodologist. The team develops a rigorous protocol to thoroughly locate, identify, extract, and analyze all of the evidence available that addresses their specific clinical question.

As systematic reviews become more frequently published, concern over quality led to the PRISMA Statement to establish a minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Many systematic reviews also contain a meta-analysis.

What is a Meta-Analysis?

Meta-analysis is a particular type of systematic review that focuses on selecting and reviewing quantitative research. Researchers conducting a meta-analysis combine the results of several independent studies and reviews to produce a synthesis where possible. These publications aim to assist in making decisions about a particular therapy.

Benefits of Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis synthesizes large amounts of data using a statistical examination. This type of analysis provides for some control between studies and generalized application to the population.

To learn how to find systematic reviews in the Walden Library, please see the Levels of Evidence Pyramid page:

- Levels of Evidence Pyramid: Systematic Reviews

Further reading

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions *updated 2022

Guidelines & summaries

Practice guidelines.

A practice guideline is a systematically-developed statement addressing common patient health care decisions in specific clinical settings and circumstances. They should be valid, reliable, reproducible, clinically applicable, clear and flexible. Documentation must be included and referenced. Practice guidelines may come from organizations, associations, government entities, and hospitals/health systems.

ECRI Guidelines Trust

Best Evidence Topics

Best evidence topics are sometimes referred to as Best BETs. These topics are developed and supported for situations or setting when the high levels of evidence don't fit or are unavailable. They originated from emergency medicine providers' need to conduct rapid evidence-based clinical decisions.

Critically-Appraised Topics

Critically-appraised topics are a standardized one- to two-page summary of the evidence supporting a clinical question. They include a critique of the literature and statement of relevant results. They can be found online in many repositories.

To learn how to find critically-appraised topics in the Walden Library, please see the Levels of Evidence Pyramid page:

- Levels of Evidence Pyramid: Critically-Appraised Topics

Critically-Appraised Articles

Critically-appraised articles are individual articles by authors that evaluate and synopsize individual research studies. ACP Journal Club is the most well known grouping of titles that include critically appraised articles.

To learn how to find critically-appraised articles in the Walden Library, please see the Levels of Evidence Pyramid page:

- Levels of Evidence Pyramid: Critically-Appraised Articles

Randomized controlled trial

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is a clinical trial in which participants are randomly assigned to either the treatment group or control group. This random allocation of participants helps to reduce any possible selection bias and makes the RCT a high level of evidence. Having a control group, which receives no treatment or a placebo treatment, to compare the treatment group against allows researchers to observe the potential efficacy of the treatment when other factors remain the same. Randomized controlled trials are quantitative studies and are often the only studies included in systematic reviews.

To learn how to find randomize controlled trials, please see our CINAHL & MEDLINE help pages:

- CINAHL Search Help: Randomized Controlled Trials

- MEDLINE Search Help: Randomized Controlled Trials

Cohort study

A cohort study is an observational longitudinal study that analyzes risk factors and outcomes by following a group (cohort) that share a common characteristic or experience over a period of time.

Cohort studies can be retrospective, looking back over time at data that has already been collected, or can be prospective, following a group forward into the future and collecting data along the way.

While cohort studies are considered a lower level of evidence than randomized controlled trials, they may be the only way to study certain factors ethically. For example, researchers may follow a cohort of people who are tobacco smokers and compare them to a cohort of non-smokers looking for outcomes. That would be an ethical study. It would be highly unethical, however, to design a randomized controlled trial in which one group of participants are forced to smoke in order to compare outcomes.

To learn how to find cohort studies, please see our CINAHL and MEDLINE help pages:

- CINAHL Search Help: Cohort Studies

- MEDLINE Search Help: Cohort Studies

Case-controlled studies

Case-controlled studies are a type of observational study that looks at patients who have the same disease or outcome. The cases are those who have the disease or outcome while the controls do not. This type of study evaluates the relationship between diseases and exposures by retrospectively looking back to investigate what could potentially cause the disease or outcome.

To learn how to find case-controlled studies, please see our CINAHL and MEDLINE help pages:

- CINAHL Search Help: Case Studies

- MEDLINE Search Help: Case Studies

Background information & expert opinion

Background information and expert opinion can be found in textbooks or medical books that provide basic information on a topic. They can be helpful to make sure you understand a topic and are familiar with terms associated with it.

To learn about accessing background information, please see the Levels of Evidence Pyramid page:

- Levels of Evidence Pyramid: Background Information & Expert Opinion

- Previous Page: Levels of Evidence Pyramid

- Next Page: CINAHL Search Help

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Levels of Evidence

Levels of evidence (or hierarchy of evidence) is a system used to rank medical studies based on the quality and reliability of their designs. The levels of evidence are commonly depicted in a pyramid model that illustrates both the quality and quantity of available evidence. The higher the position on the pyramid, the stronger the evidence. 1 Each level builds on data and research previously developed in the lower tiers.

Levels of evidence pyramids are often divided into two or three sections. The top section consists of filtered (secondary) evidence, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and critical appraisals. The section below includes unfiltered (primary) evidence, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-controlled studies, case series, and case reports. 1 Some models include an additional bottom segment for background information and expert opinion. 2

Definitions

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

A systematic review synthesizes the results from available studies of a particular health topic, answering a specific research question by collecting and evaluating all research evidence that fits the reviewer’s selection criteria. 3 The most well-known collection of systematic reviews is the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews .

Systematic reviews can include meta-analyses in which statistical methods are applied to evaluate and synthesize quantitative results from multiple studies.

A randomized controlled trial is a prospective study that measures the efficacy of an intervention or treatment. Subjects are randomly assigned to either an experimental group or a control group; the control group receives a placebo or sham intervention, while the experimental group receives the intervention being studied. Randomizing subjects is effective at removing bias, thus increasing the validity of the research. RCTs are frequently blinded so that neither the subjects (single blind), nor the clinicians (double blind), nor the researchers (triple blind) know in which group the subjects are placed. 4

A cohort study is a type of observational study, meaning that no intervention is taken among the subjects. It is also a type of longitudinal study in which research subjects are followed over a period of time. 5 A cohort study can be either prospective, which collects new data over time, or retrospective, which uses previously acquired data or medical records. This type of study examines a group of people who share a common trait or exposure and are assessed based on whether they develop an outcome of interest. An example of a prospective cohort study is a study that determines which subjects smoke and then many years later assesses the incidence of lung cancer in both smokers and non-smokers.

A case-control study is another type of observational study. It is also a type of retrospective study that looks back in time to assess information. A case-control study compares people who have the specified condition or outcome being studied (known as “cases”) with people who do not have the condition or outcome (known as “controls”). 6 An example of a case-control study is a study that assesses the lifetime smoking exposure of patients with and without lung cancer.

A case report is a detailed report of the presentation, diagnosis, treatment, treatment response, and follow-up after treatment of an individual patient. A case series is a group of case reports involving patients who share similar characteristics. A case series is observational and can be conducted either retrospectively or prospectively.

Also called a prevalence study, a cross-sectional study examines subjects at a single point in time. By definition, a cross-sectional study is only observational. 7 An example of a cross-sectional study is a survey of a population to determine the prevalence of lung cancer.

Filtered vs. Unfiltered Information

Filtered (secondary) levels of evidence include information that has been previously collected, analyzed, and aggregated by expert analysis and review. Filtered levels of evidence are placed above unfiltered levels of evidence on the pyramid. Examples of filtered levels of evidence are systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Unfiltered (primary) evidence includes original research studies, including randomized controlled trials and case-control studies. They are often published in peer-reviewed journals. 8 However, these studies have not been subjected to additional analysis and review beyond that of the peer reviewers for each study. In most cases, unfiltered levels of evidence are difficult to apply in clinical decision-making. 9

In 1972, Archibald Cochrane, a physician from Scotland, wrote Effectiveness and Efficiency, in which he argued that decisions about medical treatment should be based on a systematic review of the available clinical evidence. Cochrane proposed an international collaboration of researchers to systematically review the best clinical studies in each specialty. 10

In 1979, the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination published a ranking system for medical evidence, proposing four quality levels: 11,12

- I: Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomized controlled trial

- II-1: Evidence obtained from a well-designed cohort or case-control analytic study, preferably from more than one center or research group

- II-2: Evidence obtained from comparisons between times or places with or without the intervention

- III: Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) adopted a modified version of the Canadian Task Force’s categorization in 1988: 13,14

- II-1: Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization

- II-2: Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one center or research group

- II-3: Evidence obtained from multiple time series designs with or without the intervention; dramatic results in uncontrolled trials might also be regarded as this type of evidence

The physician Gordon Guyatt, who in 1991 coined the term “evidence-based medicine,” proposed another approach to classifying the strength of recommendations in Users' Guides to the Medical Literature . 15, 16 Referencing Guyatt’s paper, Trisha Greenhalgh summarized his revised hierarchy as follows: 17

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Randomized controlled trials with definitive results (confidence intervals that do not overlap the threshold of a clinically significant effect)

- Randomized controlled trials with non-definitive results (a point estimate that suggests a clinically significant effect but with confidence intervals overlapping the threshold for this effect)

- Cohort studies

- Case-control studies

- Cross-sectional surveys

- Case reports

Evidence levels can vary based on the clinical question being asked (i.e., the categorization of evidence for a medical treatment may differ from evidence for determining disease prevalence). For example, The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine and American Society of Plastic Surgeons published tables specific to therapeutic, diagnostic, and prognostic studies. 18,19

- Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evidence Based Medicine. 2016;21(4):125–127.

- Illustration adapted from model displayed in “Evidence-Based Practice in Health”. The model is attributed to the National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. Retrieved from University of Canberra Library.

- Turner M. “Evidence-Based Practice in Health”. 2014. Retrieved from University of Canberra website.

- Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1716.

- Barrett D, Noble H. What are cohort studies? Evid Based Nur. 2019;22(4):95–6.

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. Study design 101: Case control study. 2019.

- Singh Setia M. Methodology Series Module 3: Cross-sectional Studies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(3):261–264.

- Northern Virginia Community College. Evidence-based practice for health professionals. 2022.

- Kendall S. Evidence-based resources simplified. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(2):241–243.

- Stavrou A, Challoumas D, Dimitrakakis G. Archibald Cochrane (1909–1988): The father of evidence-based medicine. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(1):121–124.

- Spitzer WO, et al. The periodic health examination. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Can Med Assoc J. 1979;121(9):1193–1254.

- Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The Levels of Evidence and their Role in Evidence-Based Medicine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010:128(1):305–310.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (as of 2018). Grade definitions.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. DIANE Publishing, 1989. ISBN 1568062974.

- Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hayward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274(22):1800–1804.

- Zimerman AL. Evidence-Based Medicine: A Short History of a Modern Medical Movement. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(1):71–76.

- Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ. 1997;315(7102):243–246. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7102.243

- Sullivan D, Chung KC, Eaves FF 3rd, Rohrich RJ. The level of evidence pyramid: Indicating levels of evidence in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery articles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):311–314. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182195826

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of evidence. March 2009. CEBM.

Contributors

- Moira Tannenbaum, MSN

- Stacy Sebastian, MD

- Brian Sullivan, MD

Published: August 17, 2021

Updated: November 1, 2022

How Do I...?

- How Do I...? Home

- ...Use the library (in general)?

- ...Select a Topic and Make a Research Plan?

- ...Determine the Types and Levels of Sources?

- ...Evaluate Information?

- ...Find Information in the Library Collection?

- ...Use Sources Ethically and Create Correct Citations

- ...Get More Help?

Types and Levels of Sources

The types of sources you use in your research is important. not all information is created equally. there are better sources for different types of information needs., once you have defined your topic and research question consider:, the information cycle (how information is produced and disseminated over time after an event) , type of source, primary, secondary or tertiary, scholarly/peer-reviewed or not, level of evidence, systematic review, randomized controlled trials.

- Know Your Sources

This tool provides a brief description of each type of source and breaks down 6 factors of what to consider when selecting a source.

Click the image below for more information.

Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources

Sources fall into three main categories, primary, secondary and tertiary., primary sources give firsthand accounts or direct evidence regarding the event. they are writings contemporary to what is being researched., secondary sources discuss information presented elsewhere. it is created later, after the event, by someone who did not participate or experience the event. most scholarly articles and books are secondary sources., tertiary sources consolidate and summarize primary and secondary sources. for example, encyclopedias and factbooks are considered tertiary (although some may be secondary)..

- Examples of Types of Sources

Scholarly Articles and Peer-Review

Sources are created for different audiences. sources created by scholars for other scholars are often published in scholarly/peer-reviewed journals., peer-review is a vetting process a source may go through. the peer-review process involves an author submitting their work for review, then a group of their "peers" (other people working in the same field) evaluate the work for quality and meeting scientific standards. then the work is returned to the original author for edits/revisions. then the work is (hopefully) re-submitted and accepted for publishing., the peer-review process is not perfect and academic publishing is highly competitive so problems do occur. you can read about some of the conversations about revising peer-review in the following articles: scientists aim to pull peer review out of the 17th century , the future of peer review and when reviewing goes wrong: the ugly side of peer review ..

image from https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/howscienceworks_16

There are several features of scholarly sources that distinguish them from popular sources including:

Written for experts by experts, use of professional language for the discipline, based on original research or analysis of previous research, contains citations, no attractive packaging or ads, scientific paper format (abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references), peer-reviewed, published by academic publisher.

Knowing how to read a scholarly article is a very important skill. Knowing these steps can help you better understand the research you find.

Levels of Evidence

In health sciences and medicine, sources also have a level of evidence based on the type of research conducted for the work. the levels of evidence are described in a pyramid with the lowest level of evidence at the bottom and the highest level of evidence at the top. the amount of sources meeting the criteria of these levels decreases as the levels increase so that there are a lot more level vii sources than level i sources., unitypoint health uses the iowa model for evidence-based practice: https://uihc.org/iowa-model-revised-evidence-based-practice-promote-excellence-health-care.

- Rating System for the Hierarchy of Evidence for Intervention/Treatment Questions

The level of evidence can usually be discovered in the methods section of the article. Some authors will state exactly what type of study the article is about and for other sources, the reader will have to determine the study type.

Use this chart to help determine the level, level i is a systematic review and level vii is an expert opinion..

- Level of evidence flow chart

Another library has created a guide with even more information. Check it out at the link below.

- EBP Tool Kit from Winona State's Darrell W. Krueger Library

You can also use this handy chart from the University of New Mexico.

- Evidence Pyramid - Levels of Evidence

Theoretical Models and Frameworks

Theoretical models and frameworks create a structure and vision for the study. you can think of these as blueprints for the study. a scientific study will use a theoretical framework or model to guide the design of the study. , types of clinical research, action research, cross-sectional, descriptive, experimental , exploratory, longitudinal, meta-analysis, mixed methods, observational, philosophical, how to support research with theoretical and conceptual frameworks, learn more at https://rushu.libguides.com/c.phpg=694134.

- << Previous: ...Select a Topic and Make a Research Plan?

- Next: ...Evaluate Information? >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:07 AM

- URL: https://methodistcol.libguides.com/howdoi

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Types of research papers

Analytical research paper

Argumentative or persuasive paper, definition paper, compare and contrast paper, cause and effect paper, interpretative paper, experimental research paper, survey research paper, frequently asked questions about the different types of research papers, related articles.

There are multiple different types of research papers. It is important to know which type of research paper is required for your assignment, as each type of research paper requires different preparation. Below is a list of the most common types of research papers.

➡️ Read more: What is a research paper?

In an analytical research paper you:

- pose a question

- collect relevant data from other researchers

- analyze their different viewpoints

You focus on the findings and conclusions of other researchers and then make a personal conclusion about the topic. It is important to stay neutral and not show your own negative or positive position on the matter.

The argumentative paper presents two sides of a controversial issue in one paper. It is aimed at getting the reader on the side of your point of view.

You should include and cite findings and arguments of different researchers on both sides of the issue, but then favor one side over the other and try to persuade the reader of your side. Your arguments should not be too emotional though, they still need to be supported with logical facts and statistical data.

Tip: Avoid expressing too much emotion in a persuasive paper.

The definition paper solely describes facts or objective arguments without using any personal emotion or opinion of the author. Its only purpose is to provide information. You should include facts from a variety of sources, but leave those facts unanalyzed.

Compare and contrast papers are used to analyze the difference between two:

Make sure to sufficiently describe both sides in the paper, and then move on to comparing and contrasting both thesis and supporting one.

Cause and effect papers are usually the first types of research papers that high school and college students write. They trace probable or expected results from a specific action and answer the main questions "Why?" and "What?", which reflect effects and causes.

In business and education fields, cause and effect papers will help trace a range of results that could arise from a particular action or situation.

An interpretative paper requires you to use knowledge that you have gained from a particular case study, for example a legal situation in law studies. You need to write the paper based on an established theoretical framework and use valid supporting data to back up your statement and conclusion.

This type of research paper basically describes a particular experiment in detail. It is common in fields like:

Experiments are aimed to explain a certain outcome or phenomenon with certain actions. You need to describe your experiment with supporting data and then analyze it sufficiently.

This research paper demands the conduction of a survey that includes asking questions to respondents. The conductor of the survey then collects all the information from the survey and analyzes it to present it in the research paper.

➡️ Ready to start your research paper? Take a look at our guide on how to start a research paper .

In an analytical research paper, you pose a question and then collect relevant data from other researchers to analyze their different viewpoints. You focus on the findings and conclusions of other researchers and then make a personal conclusion about the topic.

The definition paper solely describes facts or objective arguments without using any personal emotion or opinion of the author. Its only purpose is to provide information.

Cause and effect papers are usually the first types of research papers that high school and college students are confronted with. The answer questions like "Why?" and "What?", which reflect effects and causes. In business and education fields, cause and effect papers will help trace a range of results that could arise from a particular action or situation.

This type of research paper describes a particular experiment in detail. It is common in fields like biology, chemistry or physics. Experiments are aimed to explain a certain outcome or phenomenon with certain actions.

- Library Home

- Books & Media

- Clarkson College ScholarWorks

- Textbooks @ Clarkson College Library

- 7th edition

- FAQ Database

- Request an Article

- RAP Sessions

- Individual/Group Sessions

- Writing Lab

- Alumni Library Services

- Book a Study Room

- Printing & Copying

- Remote Access

- Information Literacy Tutorials (Credo Instruct)

- Library Learning Tutorials

- Request In-Class Instruction

- Request a Literature Search

- Request Classroom Laptops

- Require a RAP Session

- Submit Course Reserves

- Submit to ScholarWorks

Clarkson College LibAnswers

How do i determine the level of evidence of an article, johns hopkins nursing ebp: levels of evidence.

Level I Experimental study, randomized controlled trial (RCT) Systematic review of RCTs, with or without meta-analysis

Level II Quasi-experimental Study Systematic review of a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental, or quasi-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis.

Level III Non-experimental study Systematic review of a combination of RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental, or non-experimental studies only, with or without meta-analysis. Qualitative study or systematic review, with or without meta-analysis

Level IV Opinion of respected authorities and/or nationally recognized expert committees/consensus panels based on scientific evidence. Includes: - Clinical practice guidelines - Consensus panels

Level V Based on experiential and non-research evidence. Includes: - Literature reviews - Quality improvement, program or financial evaluation - Case reports - Opinion of nationally recognized expert(s) based on experiential evidence

From Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice : Models and Guidelines Dearholt, S., Dang, Deborah, & Sigma Theta Tau International. (2012). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice : Models and Guidelines .

The links below will provide further information.

Links & Files

- The JBI Levels of Evidence

- Tutorial - Identifying Types of Evidence

- Tutorial - Using the Hierarchy of Evidence

- Tutorial - Understanding Study Design

- Winona State University Level of Evidence page

- Last Updated Jan 11, 2022

- Answered By Anne Heimann

FAQ Actions

- Share on Facebook

Comments (0)

Nights & Weekends: all questions will be answered within 48 hours

Need Research Help? Tell us about your topic and assignment.

Reporting an issue? Include details about where you encountered the issue and any error messages. If you need immediate assistance, please call the Library.

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Evidence-Based Practice for Nursing: Evaluating the Evidence

- What is Evidence-Based Practice?

- Asking the Clinical Question

- Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN

Evaluating Evidence: Questions to Ask When Reading a Research Article or Report

For guidance on the process of reading a research book or an article, look at Paul N. Edward's paper, How to Read a Book (2014) . When reading an article, report, or other summary of a research study, there are two principle questions to keep in mind:

1. Is this relevant to my patient or the problem?

- Once you begin reading an article, you may find that the study population isn't representative of the patient or problem you are treating or addressing. Research abstracts alone do not always make this apparent.

- You may also find that while a study population or problem matches that of your patient, the study did not focus on an aspect of the problem you are interested in. E.g. You may find that a study looks at oral administration of an antibiotic before a surgical procedure, but doesn't address the timing of the administration of the antibiotic.

- The question of relevance is primary when assessing an article--if the article or report is not relevant, then the validity of the article won't matter (Slawson & Shaughnessy, 1997).

2. Is the evidence in this study valid?

- Validity is the extent to which the methods and conclusions of a study accurately reflect or represent the truth. Validity in a research article or report has two parts: 1) Internal validity--i.e. do the results of the study mean what they are presented as meaning? e.g. were bias and/or confounding factors present? ; and 2) External validity--i.e. are the study results generalizable? e.g. can the results be applied outside of the study setting and population(s) ?

- Determining validity can be a complex and nuanced task, but there are a few criteria and questions that can be used to assist in determining research validity. The set of questions, as well as an overview of levels of evidence, are below.

For a checklist that can help you evaluate a research article or report, use our checklist for Critically Evaluating a Research Article

- How to Critically Evaluate a Research Article

How to Read a Paper--Assessing the Value of Medical Research

Evaluating the evidence from medical studies can be a complex process, involving an understanding of study methodologies, reliability and validity, as well as how these apply to specific study types. While this can seem daunting, in a series of articles by Trisha Greenhalgh from BMJ, the author introduces the methods of evaluating the evidence from medical studies, in language that is understandable even for non-experts. Although these articles date from 1997, the methods the author describes remain relevant. Use the links below to access the articles.

- How to read a paper: Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about) Not all published research is worth considering. This provides an outline of how to decide whether or not you should consider a research paper. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997b). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7102), 243–246.

- Assessing the methodological quality of published papers This article discusses how to assess the methodological validity of recent research, using five questions that should be addressed before applying recent research findings to your practice. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997a). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7103), 305–308.

- How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests This article and the next present the basics for assessing the statistical validity of medical research. The two articles are intended for readers who struggle with statistics more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997f). How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7104), 364–366.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician II: "Significant" relations and their pitfalls The second article on evaluating the statistical validity of a research article. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997). Education and debate. how to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: "significant" relations and their pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition), 315(7105), 422-425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.422

- How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997d). How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7106), 480–483.

- How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997c). How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7107), 540–543.

- How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997e). How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7108), 596–599.

- Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997i). Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 672–675.

- How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) A set of questions that could be used to analyze the validity of qualitative research more... less... Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7110), 740–743.

Levels of Evidence

In some journals, you will see a 'level of evidence' assigned to a research article. Levels of evidence are assigned to studies based on the methodological quality of their design, validity, and applicability to patient care. The combination of these attributes gives the level of evidence for a study. Many systems for assigning levels of evidence exist. A frequently used system in medicine is from the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine . In nursing, the system for assigning levels of evidence is often from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's 2011 book, Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . The Levels of Evidence below are adapted from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's (2011) model.

Uses of Levels of Evidence : Levels of evidence from one or more studies provide the "grade (or strength) of recommendation" for a particular treatment, test, or practice. Levels of evidence are reported for studies published in some medical and nursing journals. Levels of Evidence are most visible in Practice Guidelines, where the level of evidence is used to indicate how strong a recommendation for a particular practice is. This allows health care professionals to quickly ascertain the weight or importance of the recommendation in any given guideline. In some cases, levels of evidence in guidelines are accompanied by a Strength of Recommendation.

About Levels of Evidence and the Hierarchy of Evidence : While Levels of Evidence correlate roughly with the hierarchy of evidence (discussed elsewhere on this page), levels of evidence don't always match the categories from the Hierarchy of Evidence, reflecting the fact that study design alone doesn't guarantee good evidence. For example, the systematic review or meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are at the top of the evidence pyramid and are typically assigned the highest level of evidence, due to the fact that the study design reduces the probability of bias ( Melnyk , 2011), whereas the weakest level of evidence is the opinion from authorities and/or reports of expert committees. However, a systematic review may report very weak evidence for a particular practice and therefore the level of evidence behind a recommendation may be lower than the position of the study type on the Pyramid/Hierarchy of Evidence.

About Levels of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation : The fact that a study is located lower on the Hierarchy of Evidence does not necessarily mean that the strength of recommendation made from that and other studies is low--if evidence is consistent across studies on a topic and/or very compelling, strong recommendations can be made from evidence found in studies with lower levels of evidence, and study types located at the bottom of the Hierarchy of Evidence. In other words, strong recommendations can be made from lower levels of evidence.

For example: a case series observed in 1961 in which two physicians who noted a high incidence (approximately 20%) of children born with birth defects to mothers taking thalidomide resulted in very strong recommendations against the prescription and eventually, manufacture and marketing of thalidomide. In other words, as a result of the case series, a strong recommendation was made from a study that was in one of the lowest positions on the hierarchy of evidence.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Quantitative Questions

The pyramid below represents the hierarchy of evidence, which illustrates the strength of study types; the higher the study type on the pyramid, the more likely it is that the research is valid. The pyramid is meant to assist researchers in prioritizing studies they have located to answer a clinical or practice question.

For clinical questions, you should try to find articles with the highest quality of evidence. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses are considered the highest quality of evidence for clinical decision-making and should be used above other study types, whenever available, provided the Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis is fairly recent.

As you move up the pyramid, fewer studies are available, because the study designs become increasingly more expensive for researchers to perform. It is important to recognize that high levels of evidence may not exist for your clinical question, due to both costs of the research and the type of question you have. If the highest levels of study design from the evidence pyramid are unavailable for your question, you'll need to move down the pyramid.

While the pyramid of evidence can be helpful, individual studies--no matter the study type--must be assessed to determine the validity.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Qualitative Studies

Qualitative studies are not included in the Hierarchy of Evidence above. Since qualitative studies provide valuable evidence about patients' experiences and values, qualitative studies are important--even critically necessary--for Evidence-Based Nursing. Just like quantitative studies, qualitative studies are not all created equal. The pyramid below shows a hierarchy of evidence for qualitative studies.

Adapted from Daly et al. (2007)

Help with Research Terms & Study Types: Cut through the Jargon!

- CEBM Glossary

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine|Toronto

- Cochrane Collaboration Glossary

- Qualitative Research Terms (NHS Trust)

- << Previous: Finding Evidence

- Next: Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 10:03 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/ebn

- Carnegie Classification

- American Council on Education

- Higher Education Today

- Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education

2025 Research Designations

- Research Designations

The 2025 Carnegie Classifications will include research designations as separate listings from the Basic Classification. There will be three research groupings, all of which will be set by a threshold. Thresholds may be changed in future years; updated methodology will be shared ahead of each classification release.

In 2025, the Carnegie Classifications will use the higher of either a three-year average (2021, 2022, 2023) or most recent single year data (2023). In future releases, the classifications will use only a three-year average. Spending data will be taken from the Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey for FY2021, FY2022, and FY2023. Doctorate production will be taken from data reported to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) for academic years 2020-21, 2021-22, and 2022-23. Research doctorates include all degrees reported as a Doctor’s Degree – Research/Scholarship in IPEDS, following the IPEDS definition .

These changes are part of a series of updates for the Carnegie Classifications. For more information about the changes, please see the press release and the FAQ .

Research 1: Very High Spending and Doctorate Production

On average in a single year, these institutions spend at least $50 million on research & development and produce at least 70 research doctorates.

Research 2: High Spending and Doctorate Production

On average in a single year, these institutions spend at least $5 million on research & development and produce at least 20 research doctorates.

Research Colleges and Universities

On average in a single year, these institutions spend at least $2.5 million on research & development. Institutions that are in the R1 or R2 categories are not included.

Join Our Mailing List

Join our mailing list to be the first to receive ACE's news on the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

Our email opt-in form uses iframes. If you do not see the form, please check your tracking or privacy settings.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 August 2024

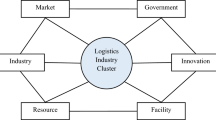

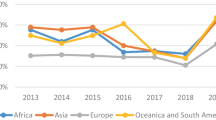

The impact of international logistics performance on import and export trade: an empirical case of the “Belt and Road” initiative countries

- Weixin Wang 1 ,

- Qiqi Wu 2 ,

- Jiafu Su ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6001-5744 3 &

- Bing li 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1028 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

180 Accesses

Metrics details

- Business and management