MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility of Starbucks

Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility of Starbucks

Starbucks is the world’s largest and most popular coffee company. Since the beginning, this premier cafe aimed to deliver the world’s finest fresh-roasted coffee. Today the company dominates the industry and has created a brand that is tantamount with loyalty, integrity and proven longevity. Starbucks is not just a name, but a culture .

It is obvious that Starbucks and their CEO Howard Shultz are aware of the importance of corporate social responsibility . Every company has problems they can work on and improve in and so does Starbucks. As of recent, Starbucks has done a great job showing their employees how important they are to the company. Along with committing to every employee, they have gone to great lengths to improve the environment for everyone. Ethical and unethical behavior is always a hot topic for the media, and Starbucks has to be careful with the decisions they make and how they affect their public persona.

The corporate social responsibility of the Starbucks Corporation address the following issues: Starbucks commitment to the environment, Starbucks commitment to the employees, Starbucks commitment to consumers, discussions of ethical and unethical business behavior, and Starbucks commitment and response to shareholders.

Commitment to the Environment

The first way Starbucks has shown corporate social responsibility is through their commitment to the environment. In order to improve the environment, with a little push from the NGO, Starbucks first main goal was to provide more Fair Trade Coffee. What this means is that Starbucks will aim to only buy 100 percent responsibly grown and traded coffee. Not only does responsibly grown coffee help the environment, it benefits the farmers as well. Responsibly grown coffee means preserving energy and water at the farms. In turn, this costs more for the company overall, but the environmental improvements are worth it. Starbucks and the environment benefits from this decision because it helps continue to portray a clean image.

Another way to improve the environment directly through their stores is by “going green”. Their first attempt to produce a green store was in Manhattan. Starbucks made that decision to renovate a 15 year old store. This renovation included replacing old equipment with more energy efficient ones. To educate the community, they placed plaques throughout the store explaining their new green elements and how they work. This new Manhattan store now conserves energy, water, materials, and uses recycled/recyclable products. Twelve stores total plan to be renovated and Starbucks has promised to make each new store LEED, meaning a Leader in Energy and Environmental Design. LEED improves performance regarding energy savings, water efficiency, and emission reduction. Many people don’t look into environmentally friendly appliances because the upfront cost is always more. According to Starbucks, going green over time outweighs the upfront cost by a long shot. Hopefully, these new design elements will help the environment and get Starbucks ahead of their market.

Commitment to Consumers

The second way Starbucks has shown corporate social responsibility is through their commitment to consumers. The best way to get the customers what they want is to understand their demographic groups. By doing research on Starbucks consumer demographics, they realized that people with disabilities are very important. The company is trying to turn stores into a more adequate environment for customers with disabilities. A few changes include: lowering counter height to improve easy of ordering for people in wheelchairs, adding at least one handicap accessible entrance, adding disability etiquette to employee handbooks, training employees to educate them on disabilities, and by joining the National Business Disability Council. By joining the National Business Disability Council, Starbucks gains access to resumes of people with disabilities.

Another way Starbucks has shown commitment to the consumers is by cutting costs and retaining loyal customers. For frequent, loyal customers, Starbucks decided to provide a loyalty card. Once a customer has obtained this card, they are given incentives and promotions for continuing to frequent their stores. Promotions include discounted drinks and free flavor shots to repeat visitors. Also, with the economy being at an all time low, Starbucks realized that cheaper prices were a necessity. By simplifying their business practices, they were able to provide lower prices for their customers. For example, they use only one recipe for banana bread, rather than eleven!

It doesn’t end there either! Starbucks recognized that health is part of social responsibility. To promote healthier living, they introduced “skinny” versions of most drinks, while keeping the delicious flavor. For example, the skinny vanilla latte has 90 calories compared to the original with 190 calories. Since Starbucks doesn’t just sell beverages now, they introduced low calorie snacks. Along with the snacks and beverages, nutrition facts were available for each item.

Also one big way to cut costs was outsourcing payroll and Human Resources administration . By creating a global platform for their administration system, Starbucks is able to provide more employees with benefits. Plus, they are able to spend more money on pleasing customers, rather than on a benefits system.

Commitment and Response to Shareholders

One way Starbucks has demonstrated their commitment and response to shareholder needs is by giving them large portions. By large portions, Starbucks is implying that they plan pay dividends equal to 35% or higher of net income to. For the shareholders, paying high dividends means certainty about the company’s financial well-being. Along with that, they plan to purchase 15 million more shares of stock, and hopefully this will attract investors who focus on stocks with good results.

Starbucks made their commitment to shareholders obvious by speaking directly to the media about it. In 2004, Starbucks won a great tax break, but unfortunately the media saw them as “money grubbing”. Their CEO, Howard Shultz, made the decision to get into politics and speak to Washington about expanding health care and the importance of this to the company. Not only does he want his shareholders to see his commitment, but he wants all of America to be able to reap this benefits.

In order to compete with McDonalds and keeping payout to their shareholders high, Starbucks needed a serious turnaround . They did decide to halt growth in North America but not in Japan. Shultz found that drinking coffee is becoming extremely popular for the Japanese. To show shareholders there is a silver lining, he announced they plan to open “thousands of stores” in Japan and Vietnamese markets.

Commitment to Employees

The first and biggest way Starbucks shows their commitment to employees is by just taking care of their workers. For example, they know how important health care, stock options, and compensation are to people in this economy. The Starbucks policy states that as long as you work 20 hours a week you get benefits and stock options. These benefits include health insurance and contributions to employee’s 401k plan. Starbucks doesn’t exclude part time workers, because they feel they are just as valuable as full time workers. Since Starbucks doesn’t have typical business hours like an office job, the part time workers help working the odd shifts.

Another way Starbucks shows their commitment to employees is by treating them like individuals, not just number 500 out of 26,000 employees. Howard Shultz, CEO, always tries to keep humanity and compassion in mind. When he first started at Starbucks, he remembered how much he liked it that people cared about him, so he decided to continue this consideration for employees. Shultz feels that a first impression is very important. On an employee’s first day, he lets each new employee know how happy he is to have them as part of their business, whether it is in person or through a video. His theory is that making a good first impression on a new hire is similar to teaching a child good values. Through their growth, he feels each employee will keep in mind that the company does care about them. Shultz wants people to know what he and the company stand for, and what they are trying to accomplish.

Ethical/Unethical Business Behavior

The last way Starbucks demonstrates corporate social responsibility is through ethical behavior and the occasional unethical behavior. The first ethically positive thing Starbucks involves them self in is the NGO and Fair Trade coffee. Even though purchasing mostly Fair Trade coffee seriously affected their profits, Starbucks knew it was the right thing to do. They also knew that if they did it the right way, everyone would benefit, from farmers, to the environment, to their public image.

In the fall of 2010, Starbucks chose to team up with Jumpstart, a program that gives children a head start on their education. By donating to literacy organizations and volunteering with Jumpstart, Starbucks has made an impact on the children in America, in a very positive way.

Of course there are negatives that come along with the positives. Starbucks isn’t the “perfect” company like it may seem. In 2008, Starbucks made the decision to close 616 stores because they were not performing very well. In order for Starbucks to close this many stores in one year, they had to battle many landlords due to the chain breaking lease agreements. Starbucks tried pushing for rent cuts but some stores did have to break their agreements. On top of breaching lease agreements, Starbucks was not able to grow as much as planned, resulting their future landlords were hurting as well. To fix these problems, tenants typically will offer a buyout or find a replacement tenant, but landlords are in no way forced to go with any of these options. These efforts became extremely time consuming and costly, causing Starbucks to give up on many lease agreements.

As for Starbucks ethical behavior is a different story when forced into the media light. In 2008, a big media uproar arose due to them wanting to re-release their old logo for their 35th anniversary. The old coffee cup logo was basically a topless mermaid, which in Starbucks’ opinion is just a mythological creature, not a sex symbol. Media critics fought that someone needed to protect the creature’s modesty. Starbucks found this outrageous. In order to end the drama and please the critics, they chose to make the image more modest by lengthening her hair to cover her body and soften her facial expression. Rather than ignoring the media concerns, Starbucks met in the middle to celebrate their 35th anniversary.

Related posts:

- Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility at The Body Shop

- Case Study: British Petroleum and Corporate Social Responsibility

- Case Study: Starbucks Social Media Marketing Strategy

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) – Definition, Perspectives and Approaches

- The Importance of Corporate Social Responsibility in Business

- Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Corporate Social Responsibility as a Source of Competitive Advantage

- Stakeholders Perspective on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

- Stakeholder Expectations and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

- Aligning Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility

One thought on “ Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility of Starbucks ”

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Curated Resources UT Star Icon

Sustainability & CSR

Sustainability describes the ability to maintain various systems and processes — environmental, social, and economic — over time. Corporate Social Responsibility, or CSR, is as varied as the companies that practice it.

Sustainability originated in natural resource economics, but has since gained broader currency in terms of sustainable development and social equality. Corporate Social Responsibility, or CSR, usually refers to a company’s commitment to practice environmental and social sustainability and to be good stewards of the environment and the social landscapes in which they operate.

Approaches to sustainability and CSR vary according to industry and how an individual organization defines and embraces these ideas. Some companies and economists reject the idea of CSR because it implies an obligation to society and future generations beyond those contained in the binding legal requirements of business. However, most companies now embrace some notion of CSR. Some companies invest in CSR as reputation management or to sustain the profitability of a company, and some invest in CSR out of a sense of moral obligation to society.

These resources focus on sustainability and CSR primarily in terms of moral obligation. They offer insight into ethics concepts relevant to economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, and social equity. Among other things, the resources describe how companies may determine what factors to favor in ethical decisions, the impact of intangible factors in ethical dilemmas, and best practices for developing ethical culture in organizations.

Start Here: Videos

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort that we feel when our minds entertain two contradictory concepts at the same time.

Ethical Fading

Ethical fading occurs when we are so focused on other aspects of a decision that its ethical dimensions fade from view.

Tangible & Abstract

Tangible and abstract describes how we react more to vivid, immediate inputs than to ones removed in time and space, meaning we can pay insufficient attention to the adverse consequences our actions have on others.

Start Here: Cases

- Arctic Offshore Drilling

Competing groups frame the debate over oil drilling off Alaska’s coast in varying ways depending on their environmental and economic interests.

- Climate Change & the Paris Deal

While climate change poses many abstract problems, the actions (or inactions) of today’s populations will have tangible effects on future generations.

The Costco Model

How can companies promote positive treatment of employees and benefit from leading with the best practices? Costco offers a model.

Teaching Notes

Begin by viewing the “Start Here” videos. They introduce concepts that are basic to sustainability and CSR. Read through these videos’ teaching notes for details and related ethics concepts. Watch the “Related Videos” and/or read the related Case Study. “Additional Resources” offer further reading, a bibliography, and (sometimes) assignment suggestions.

The “Additional Videos” describe the way incentives affect economics, how the slippery slope leads to moral degradation, why “framing” matters to sustainability and CSR, and the hallmarks of fair and equal representation. Other videos introduce behavioral ethics biases that impact ethical decision-making, such as the tendency to switch values based on our role, and the importance of loss aversion in making moral choices.

Show a video in class, assign a video to watch outside of class, or embed a video in an online learning module such as Canvas. Then, prompt conversation in class to encourage peer-to-peer learning. Ask students to answer the video’s “Discussion Questions,” and to reflect on the ideas and issues raised by the students in the video. How do their experiences align? How do they differ? The videos also make good writing prompts. Ask students to watch a video and apply the ethics concept to course content.

Case studies are an effective way to introduce ethics topics, too, and for students to learn how to spot ethical issues. Read the recommended case studies to start class discussion on issues related to economic and environmental sustainability and social equity. The selected cases cover these topics across a wide range of disciplines and examine sustainability and CSR in terms of fair business practices, environmental policies, advertising, consumer goods, equal representation, and freedom of speech.

Ask students to answer the case study “Discussion Questions.” Then, ask students to reason through the ethical dimensions presented, and to sketch the ethical decision-making process outlined by the case. Then, challenge students to develop strategies to avoid these ethical pitfalls. Suggest students watch the case study’s “Related Videos” and “Related Terms” to further their understanding.

Ethics Unwrapped blogs are also useful prompts to engage students. Learning about ethics in the context of real-world (often current) events can enliven classroom discussion and make ethics relevant and concrete for students. Share a blog in class or post one to the class’s online learning module. To spur discussion, ask students to identify the ethical issues at hand and to name the ethics concepts related to the blog (or current event in the news). Dig more deeply into the topic using the Additional Resources listed at the end of the blog post.

Remember to review video, case study, and blogs’ relevant glossary terms. In this way, you will become familiar with all the ethics concepts contained in these material. Share this vocabulary with your students, and use it to expand and enrich ethics and leadership conversations in your classroom. To dive deeper in the glossary, watch “Related” glossary videos.

Many of the concepts covered in Ethics Unwrapped operate in tandem with each other. As you watch more videos, you will become more fluent in ethics and see the interrelatedness of ethics concepts more readily. You also will be able to spot ethical issues more easily – at least, that is the hope! As your students watch more videos, it will be easier for them to recognize and understand ethical issues, and to express their ideas and thoughts about what is and isn’t ethical and why. Hopefully, they will also come to realize the interconnectedness of ethics and leadership, and the essential role ethics plays in developing solid leadership skills that support sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

Additional Videos

- Causing Harm

- Conflict of Interest

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Diffusion of Responsibility

- Fundamental Moral Unit

- GVV Pillar 6: Voice

- Incrementalism

- Incentive Gaming

- Loss Aversion

- Moral Agent

- Moral Agent & Subject of Moral Worth

- Moral Equilibrium

- Moral Illusions Explained

- Moral Imagination

- Moral Muteness

- Moral Myopia

- Representation

- Role Morality

- Self-serving Bias

- Systematic Moral Analysis

Additional Cases

Related to economic sustainability.

- Apple Suppliers & Labor Practices

- Myanmar Amber

- Selling Enron

- The Collapse of Barings Bank

Related to Environmental Sustainability

- Buying Green: Consumer Behavior

Related to Social Equity

- Banning Burkas: Freedom or Discrimination?

- Freedom of Speech on Campus

- Pao & Gender Bias

- Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

- Responding to Child Migration

- Welfare Reform

Stay Informed

Support our work.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Corporate social responsibility

- Business management

- Corporate governance

- Business structures

The Top Sustainability Stories of 2019

- Andrew Winston

- December 30, 2019

Project Leaders Will Make or Break Your Sustainability Goals

- Antonio Nieto Rodriguez

- October 10, 2022

Collaborating with Congregations: Opportunities for Financial Services in the Inner City

- Larry Fondation

- Peter Tufano

- Patricia H. Walker

- From the July–August 1999 Issue

Gathering Green Data: Tools and Tips

- December 03, 2009

A Bolder Vision for Business Schools

- March 11, 2020

The Drucker Forum: Three Messages for Managers

- Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

- December 09, 2009

Companies that Practice “Conscious Capitalism” Perform 10x Better

- Tony Schwartz

- April 04, 2013

A Question of Character

- Suzy Wetlaufer

- From the September–October 1999 Issue

Breakthrough ideas for 2006

- From the February 2006 Issue

AI Fairness Isn’t Just an Ethical Issue

- Greg Satell

- Yassmin Abdel-Magied

- October 20, 2020

What Top Consulting Firms Get Wrong About Hiring

- Tino Sanandaji

- January 14, 2020

Under Fire, Microfinance Faces Falling Out of Favor

- Vijay Govindarajan

- August 01, 2011

Why You Need a Resilience Strategy Now

- May 09, 2014

From Starbucks to Nike, Business Asks for Green Legislation

- Mindy S. Lubber

- December 05, 2008

Copenhagen: Why the U.S. Should Build a Green City

- Mark Johnson and Josh Suskewicz

Making Sense of the Many Kinds of Impact Investing

- Brian Trelstad

- January 28, 2016

Ethics in Practice

- Kenneth R. Andrews

- From the September–October 1989 Issue

Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value

- Michael E. Porter

- Mark R. Kramer

- From the November–December 1999 Issue

Home Depot’s Blueprint for Culture Change

- From the April 2006 Issue

The State of Socially Responsible Investing

- Adam Connaker

- Saadia Madsbjerg

- January 17, 2019

Block 16: Ecuadorian Government's Perspective

- Malcolm S. Salter

- Susan E.A. Hall

- July 21, 1993

Okta For Good: Pursuing Innovation and Impact in Corporate Social Responsibility

- Andrew Isaacs

- Natalia Costa i Coromina

- Adam Rosenzweig

- August 01, 2019

LifeSpan Inc.: Abbott Northwestern Hospital

- Melvyn A.J. Menezes

- December 30, 1986

Mattelsa: A Successful Conscious Capitalism Business Model

- Juanita Cajiao

- Enrique Ramirez

- December 03, 2019

Inland Steel Industries (D)

- Kirk O. Hanson

- Stephen Weiss

- January 01, 1992

Pemex (B): The Rebound?

- Aldo Musacchio

- Noel Maurer

- Regina Garcia Cuellar

- December 04, 2012

People Analytics at Teach For America (A)

- Jeffrey T. Polzer

- Julia Kelley

- February 22, 2018

Block 16: Management's Perspective

- November 02, 1993

Kaweyan: Female Entrepreneurship and the Past and Future of Afghanistan

- Geoffrey G. Jones

- Gayle Tzemach Lemmon

- August 25, 2010

Trinity College (A)

- F. Warren McFarlan

- December 02, 1996

Hurtigruten: Sailing into Warm Water?

- Jan W. Rivkin

- Kerry Herman

Richard Fahey and Robert Saudek (A): Lighting Liberia

- Rosabeth Moss Kanter

- Anne Arlinghaus

- September 06, 2012

Mothers of Rotterdam: Scaling a Social Services Program in the Netherlands

- Laura Winig

- Julie Boatright Wilson

- June 07, 2018

Hewlett-Packard's Home Products Division in Europe--1996-2000

- David J. Arnold

- Carin-Isabel Knoop

- November 21, 2000

Henkel: Building a Winning Culture

- Robert Simons

- Natalie Kindred

- February 07, 2012

Adidas' Human Rights Policy and Euro 2000

- Robert Crawford

- February 07, 2002

IBM Values and Corporate Citizenship

- March 31, 2008

Newman's Own, Inc.

- James E. Austin

- October 07, 1998

The Tate's Digital Transformation

- April 07, 2014

Agility: A Global Logistics Company and Local Humanitarian Partner

- Rolando Tomasini

- Margaret Hanson

- Luk N. Van Wassenhove

- March 27, 2009

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Contributors

The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility

Matteo Tonello is Director of Corporate Governance for The Conference Board, Inc. This post is based on a Conference Board Director Note by Archie B. Carroll and Kareem M. Shabana , and relates to a paper by these authors, titled “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice,” published in the International Journal of Management Reviews .

In the last decade, in particular, empirical research has brought evidence of the measurable payoff of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to companies as well as their stakeholders. Companies have a variety of reasons for being attentive to CSR. This report documents some of the potential bottomline benefits: reducing cost and risk, gaining competitive advantage, developing and maintaining legitimacy and reputational capital, and achieving win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation.

The term “corporate social responsibility” is still widely used even though related concepts, such as sustainability, corporate citizenship, business ethics, stakeholder management, corporate responsibility, and corporate social performance, are vying to replace it. In different ways, these expressions refer to the ensemble of policies, practices, investments, and concrete results deployed and achieved by a business corporation in the pursuit of its stakeholders’ interests.

This report discusses the business case for CSR—that is, what justifies the allocation of resources by the business community to advance a certain socially responsible cause. The business case is concerned with the following question: what tangible benefits do business organizations reap from engaging in CSR initiatives? This report reviews the most notable research on the topic and provides practical examples of CSR initiatives that are also good for the business and its bottom line.

The Search for a Business Case: A Shift in Perspective

Business management scholars have been searching for a business case for CSR since the origins of the concept in the 1960s. [1]

An impetus for the research questions for this report was philosophical. It had to do with the long-standing divide between those who, like the late economist Milton Friedman, believed that the corporation should pursue only its shareholders’ economic interests and those who conceive the business organization as a nexus of relations involving a variety of stakeholders (employees, suppliers, customers, and the community where the company operates) without which durable shareholder value creation is impossible. If it could be demonstrated that businesses actually benefited financially from a CSR program designed to cultivate such a range of stakeholder relations, the thinking of the latter school went, then Friedman’s arguments would somewhat be neutralized.

Another impetus to research on the business case of CSR was more pragmatic. Even though CSR came about because of concerns about businesses’ detrimental impacts on society, the theme of making money by improving society has also always been in the minds of early thinkers and practitioners: with the passage of time and the increase in resources being dedicated to CSR pursuits, it was only natural that questions would begin to be raised about whether CSR was making economic sense.

Obviously, corporate boards, CEOs, CFOs, and upper echelon business executives care. They are the guardians of companies’ financial well-being and, ultimately, must bear responsibility for the impact of CSR on the bottom line. At multiple levels, executives need to justify that CSR is consistent with the firm’s strategies and that it is financially sustainable. [a]

However, other groups care as well. Shareholders are acutely concerned with financial performance and sensitive to possible threats to management’s priorities. Social activists care because it is in their long-term best interests if companies can sustain the types of social initiatives that they are advocating. Governmental bodies care because they desire to see whether companies can deliver social and environmental benefits more cost effectively than they can through regulatory approaches. [b] Consumers care as well, as they want to pass on a better world to their children, and many want their purchasing to reflect their values.

[a] K. O’Sullivan, “Virtue rewarded: companies are suddenly discovering the profit potential of social responsibility.” CFO , October 2006, pp. 47–52.

[b] Simon Zadek. Doing Good and Doing Well: Making the Business Case for Corporate Citizenship . New York: The Conference Board Research Report, 2000, 1282-00-RR.

The socially responsible investment movement Establishing a positive relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and corporate financial performance (CFP) has been a long-standing pursuit of researchers. This endeavor has been described as a “30-year quest for an empirical relationship between a corporation’s social initiatives and its financial performance.” [2] One comprehensive review and assessment of studies exploring the CSP-CFP relationship concludes that there is a positive relationship between CSP and CFP. [3]

In response to this empirical evidence, in the last decade the investment community, in particular, has witnessed the growth of a cadre of socially responsible investment funds (SRI), whose dedicated investment strategy is focused on businesses with a solid track record of CSR-oriented initiatives. Today, the debate on the business case for CSR is clearly influenced by these new market trends: to raise capital, these players promote the belief of a strong correlation between social and financial performance. [4]

As the SRI movement becomes more influential, CSR theories are shifting away from an orientation on ethics (or altruistic rationale) and embracing a performance-driven orientation. In addition, analysis of the value generated by CSR has moved from the macro to the organizational level, where the effects of CSR on firm financial performance are directly experienced. [5]

The CSR of the 1960s and 1970s was motivated by social considerations, not economic ones. “While there was substantial peer pressure among corporations to become more philanthropic, no one claimed that such firms were likely to be more profitable than their less generous competitors.” In contrast, the essence of the new world of CSR is “doing good to do well.” [6]

CSR is evolving into a core business function, central to the firm’s overall strategy and vital to its success. [7] Specifically, CSR addresses the question: “can companies perform better financially by addressing both their core business operations as well as their responsibilities to the broader society?” [8]

One Business Case Just Won’t Do

There is no single CSR business case—no single rationalization for how CSR improves the bottom line. Over the years, researchers have developed many arguments. In general, these arguments can be grouped based on approach, topics addressed, and underlying assumptions about how value is created and defined. According to this categorization, CSR is a viable business choice as it is a tool to:

- implement cost and risk reductions;

- gain competitive advantage;

- develop corporate reputation and legitimacy; and

- seek win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation. [9]

Other widely accepted approaches substantiating the business case include focusing on the empirical research linking CSR with corporate social performance (CSP) and identifying values brought to different stakeholder groups that directly or indirectly benefit the company’s bottom lines.

Broad versus narrow views Some researchers have examined the integration of CSR considerations in the day-to-day business agenda of organizations. The “mainstreaming” of CSR follows from one of three rationales:

- the social values-led model, in which organizations adopt CSR initiatives regarding specific issues for non-economic reasons;

- the business-case model, in which CSR initiatives are primarily assessed in an economic manner and pursued only when there is a clear link to firm financial performance [10] ; and

- the syncretic stewardship model, which combines the social values-led and the business-case models.

The business case model and the syncretic models may be seen as two perspectives of the business case for CSR: one narrow and one broad. The business case model represents the narrow view: CSR is only recognized when there is a clear link to firm financial performance. The syncretic model is broad because it recognizes both direct and indirect relationships between CSR and firm financial performance. The advantage of the broad view is that it enables the firm to identify and exploit opportunities beyond the financial, opportunities that the narrow view would not be able to recognize or justify.

Another advantage of the broad view of the business case, which is illustrated by the syncretic model, is its recognition of the interdependence between business and society. [11]

The failure to recognize such interdependence in favor of pitting business against society leads to reducing the productivity of CSR initiatives. “The prevailing approaches to CSR are so fragmented and so disconnected from business and strategy as to obscure many of the greatest opportunities for companies to benefit society.” [12] The adoption of CSR practices, their integration with firm strategy, and their mainstreaming in the day-to-day business agenda should not be done in a generic manner. Rather, they should be pursued “in the way most appropriate to each firm’s strategy.” [13]

In support of the business case for CSR, the next sections of the report discuss examples of the effect of CSR on firm performance. The discussion is organized according to the framework referenced earlier, which identifies four categories of benefits that firms may attain from engaging in CSR activities. [14]

Reducing Costs and Risks

Cost and risk reduction justifications contend that engaging in certain CSR activities will reduce the firm’s inefficient capital expenditures and exposure to risks. “[T]he primary view is that the demands of stakeholders present potential threats to the viability of the organization, and that corporate economic interests are served by mitigating the threats through a threshold level of social or environmental performance.” [15]

Equal employment opportunity policies and practices CSR activities in the form of equal employment opportunity (EEO) policies and practices enhance long-term shareholder value by reducing costs and risks. The argument is that explicit EEO statements are necessary to illustrate an inclusive policy that reduces employee turnover through improving morale. [16] This argument is consistent with those who observe that “[l]ack of diversity may cause higher turnover and absenteeism from disgruntled employees.” [17]

Energy-saving and other environmentally sound production practices Cost and risk reduction may also be achieved through CSR activities directed at the natural environment. Empirical research shows that being environmentally proactive results in cost and risk reduction. Specifically, data shows hat “being proactive on environmental issues can lower the costs of complying with present and future environmental regulations … [and] … enhance firm efficiencies and drive down operating costs.” [18]

Community relations management Finally, CSR activities directed at managing community relations may also result in cost and risk reductions. [19] For example, building positive community relationships may contribute to the firm’s attaining tax advantages offered by city and county governments to further local investments. In addition, positive community relationships decrease the number of regulations imposed on the firm because the firm is perceived as a sanctioned member of society.

Cost and risk reduction arguments for CSR have been gaining wide acceptance among managers and executives. In a survey of business executives by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 73 percent of the respondents indicated that “cost savings” was one of the top three reasons companies are becoming more socially responsible. [20]

Gaining Competitive Advantage

As used in this section of the report, the term “competitive advantage” is best understood in the context of a differentiation strategy; in other words, the focus is on how firms may use CSR practices to set themselves apart from their competitors. The previous section, which focused on cost and risk reduction, illustrated how CSR practices may be thought of in terms of building a competitive advantage through a cost management strategy. “Competitive advantages” was cited as one of the top two justifications for CSR in a survey of business executives reported in a Fortune survey. [21] In this context, stakeholder demands are seen as opportunities rather than constraints. Firms strategically manage their resources to meet these demands and exploit the opportunities associated with them for the benefit of the firm. [22] This approach to CSR requires firms to integrate their social responsibility initiatives with their broader business strategies.

Reducing costs and risks • Equal employment opportunity policies and practices • Energy-saving and other environmentally sound production practices • Community relations management

Gaining competitive advantage • EEO policies • Customer relations program • Corporate philanthropy

Developing reputation and legitimacy • Corporate philanthropy • Corporate disclosure and transparency practices

Seeking win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation • Charitable giving to education • Stakeholder engagement

EEO policies Companies that build their competitive advantage through unique CSR strategies may have a superior advantage, as the uniqueness of their CSR strategies may serve as a basis for setting the firm apart from its competitors. [23] For example, an explicit statement of EEO policies would have additional benefits to the cost and risk reduction discussed earlier in this report. Such policies would provide the firm with a competitive advantage because “[c]ompanies without inclusive policies may be at a competitive disadvantage in recruiting and retaining employees from the widest talent pool.” [24]

Customer and investor relations programs CSR initiatives can contribute to strengthening a firm’s competitive advantage, its brand loyalty, and its consumer patronage. CSR initiatives also have a positive impact on attracting investment. Many institutional investors “avoid companies or industries that violate their organizational mission, values, or principles… [They also] seek companies with good records on employee relations, environmental stewardship, community involvement, and corporate governance.” [25]

Corporate philanthropy Companies may align their philanthropic activities with their capabilities and core competencies. “In so doing, they avoid distractions from the core business, enhance the efficiency of their charitable activities and assure unique value creation for the beneficiaries.” [26] For example, McKinsey & Co. offers free consulting services to nonprofit organizations in social, cultural, and educational fields. Beneficiaries include public art galleries, colleges, and charitable institutions. [27] Home Depot Inc. provided rebuilding knowhow to the communities victimized by Hurricane Katrina. Strategic philanthropy helps companies gain a competitive advantage and in turn boosts its bottom line. [28]

CSR initiatives enhance a firm’s competitive advantage to the extent that they influence the decisions of the firm’s stakeholders in its favor. Stakeholders may prefer a firm over its competitors specifically due to the firm’s engagement in such CSR initiatives.

Developing Reputation and Legitimacy

Companies may also justify their CSR initiatives on the basis of creating, defending, and sustaining their legitimacy and strong reputations. A business is perceived as legitimate when its activities are congruent with the goals and values of the society in which the business operates. In other words, a business is perceived as legitimate when it fulfills its social responsibilities. [29]

As firms demonstrate their ability to fit in with the communities and cultures in which they operate, they are able to build mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders. Firms “focus on value creation by leveraging gains in reputation and legitimacy made through aligning stakeholder interests.” [30] Strong reputation and legitimacy sanction the firm to operate in society. CSR activities enhance the ability of a firm to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of consumers, investors, and employees. Time and again, consumers, employees, and investors have shown a distinct preference for companies that take their social responsibilities seriously. A Center for Corporate Citizenship study found that 66 percent of executives thought their social responsibility strategies resulted in improving corporate reputation and saw this as a business benefit. [31]

Corporate philanthropy Corporate philanthropy may be a tool of legitimization. Firms that have negative social performance in the areas of environmental issues and product safety use charitable contributions as a means for building their legitimacy. [32]

Corporate disclosure and transparency practices Corporations have also enhanced their legitimacy and reputation through the disclosure of information regarding their performance on different social and environmental issues, sometimes referred to as sustainability reporting. Corporate social reporting refers to stand-alone reports that provide information regarding a company’s economic, environmental, and social performance. The practice of corporate social reporting has been encouraged by the launch of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997-1998 and the introduction of the United Nations Global Compact in 1999. Through social reporting, firms can document that their operations are consistent with social norms and expectations, and, therefore, are perceived as legitimate.

Seeking Win-Win Outcomes through Synergistic Value Creation

Synergistic value creation arguments focus on exploiting opportunities that reconcile differing stakeholder demands. Firms do this by “connecting stakeholder interests, and creating pluralistic definitions of value for multiple stakeholders simultaneously.” [33] In other words, with a cause big enough, they can unite many potential interest groups.

Charitable giving to education When companies get the “where” and the “how” right, philanthropic activities and competitive advantage become mutually reinforcing and create a virtuous circle. Corporate philanthropy may be used to influence the competitive context of an organization, which allows the organization to improve its competitiveness and at the same time fulfill the needs of some of its stakeholders. For example, in the long run, charitable giving to education improves the quality of human resources available to the firm. Similarly, charitable contributions to community causes eventually result in the creation and preservation of a higher quality of life, which may sustain “sophisticated and demanding local customers.” [34]

The notion of creating win-win outcomes through CSR activities has been raised before. Management expert Peter Drucker argues that “the proper ‘social responsibility’ of business is to … turn a social problem into economic opportunity and economic benefit, into productive capacity, into human competence, into well-paid jobs, and into wealth.” [35] It has been argued that, “it will not be too long before we can begin to assert that the business of business is the creation of sustainable value— economic, social and ecological.” [36]

An example: the win-win perspective adopted by the life sciences firm Novo Group allowed it to pursue its business “[which] is deeply involved in genetic modification and yet maintains highly interactive and constructive relationships with stakeholders and publishes a highly rated environmental and social report each year.” [37]

Stakeholder engagement The win-win perspective on CSR practices aims to satisfy stakeholders’ demands while allowing the firm to pursue financial success. By engaging its stakeholders and satisfying their demands, the firm finds opportunities for profit with the consent and support of its stakeholder environment.

The business case for corporate social responsibility can be made. While it is valuable for a company to engage in CSR for altruistic and ethical justifications, the highly competitive business world in which we live requires that, in allocating resources to socially responsible initiatives, firms continue to consider their own business needs.

In the last decade, in particular, empirical research has brought evidence of the measurable payoff of CSR initiatives on firms as well as their stakeholders. Firms have a variety of reasons for being CSR-attentive. But beyond the many bottom-line benefits outlined here, businesses that adopt CSR practices also benefit our society at large.

[1] See Edward Freeman, Strategic Management: a Stakeholder Approach , 1984, which traces the roots of CSR to the 1960s and 1970s, when many multinationals were formed. (go back)

[2] J. D. Margolis and Walsh, J.P. “Misery loves companies: social initiatives by business.” Administrative Science Quarterly , 48, 2003, pp. 268–305. (go back)

[3] J. F. Mahon and Griffin, J .J. “Painting a portrait: a reply.” Business and Society , 38, 1999, 126–133. (go back)

[4] See, for an overview, Stephen Gates, Jon Lukomnik, and David Pitt- Watson, The New Capitalists: How Citizen Investors Are Reshaping The Business Agenda , Harvard Business School Press, 2006. (go back)

[5] M.P. Lee, “A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: its evolutionary path and the road ahead”. International Journal of Management Reviews , 10, 2008, 53–73. (go back)

[6] D.J. Vogel, “Is there a market for virtue? The business case for corporate social responsibility.” California Management Review , 47, 2005, pp. 19–45. (go back)

[7] Ibid. (go back)

[8] Elizabeth Kurucz; Colbert, Barry; and Wheeler, David “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility.” Chapter 4 in Crane, A.; McWilliams, A.; Matten, D.; Moon, J. and Siegel, D. The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 83-112 (go back)

[9] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler , 85-92. (go back)

[10] Berger,I.E., Cunningham, P. and Drumwright, M.E. “Mainstreaming corporate and social responsibility: developing markets for virtue,” California Management Review , 49, 2007, 132-157. (go back)

[11] Ibid. (go back)

[12] M.E. Porter and Kramer, M.R. “Strategy & society: the link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility.” Harvard Business Review , 84, 2006,pp. 78–92. (go back)

[13] Ibid. (go back)

[14] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler, 85-92. (go back)

[15] Ibid., 88. (go back)

[16] T. Smith, “Institutional and social investors find common ground. Journal of Investing , 14, 2005, 57–65. (go back)

[17] S. L. Berman, Wicks, A.C., Kotha, S. and Jones, T.M. “Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance.” Academy of Management Journal , 42, 1999, 490. (go back)

[18] Ibid. (go back)

[19] Ibid. (go back)

[20] Top 10 Reasons, PricewaterhouseCoopers 2002 Sustainability Survey Report, reported in “Corporate America’s Social Conscience,” Fortune , May 26, 2003, 58. (go back)

[21] Top 10 Reasons . (go back)

[22] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler (go back)

[23] N. Smith, 2003, 67. (go back)

[24] T. Smith, 2005, 60. (go back)

[25] Ibid., 64. (go back)

[26] Heike Bruch and Walter, Frank (2005). “The Keys to Rethinking Corporate Philanthropy.” MIT Sloan Management Review , 47(1): 48-56 (go back)

[27] Ibid., 50. (go back)

[28] Bruce Seifert, Morris, Sara A.; and Bartkus, Barbara R. (2003). “Comparing Big Givers and Small Givers: Financial Correlates of Corporate Philanthropy.” Journal of Business Ethics , 45(3): 195-211. (go back)

[29] Archie B. Carroll and Ann K. Buchholtz, Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability and Stakeholder Management , 8th Edition, Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2012, 305. (go back)

[30] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler, 90. (go back)

[31] “Managing Corporate Citizenship as a Business Strategy,” Boston: Center for Corporate Citizenship, 2010. (go back)

[32] Jennifer C. Chen, Dennis M.; & Roberts, Robin. “Corporate Charitable Contributions: A Corporate Social Performance or Legitimacy Strategy?” Journal of Business Ethics , 2008, 131-144. (go back)

[33] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler , 91. (go back)

[34] Porter and Kramer, 60-65. (go back)

[35] Peter F. Drucker, “The New Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility.” California Management Review , 1984, 26: 53-63 (go back)

[36] C. Wheeler, B. Colbert, and R. E. Freeman. “Focusing on Value: Reconciling Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and a Stakeholder Approach in a Network World.” Journal of General Management , (28)3, 2003, 1-28. (go back)

[37] Ibid. (go back)

Nice blog. CSR has become something very important to all the corporate houses today. However, with the rising growth of CSR activities. It is very important to have an effective software that helps to keep a track of the entire exercise.

Interesting article! Perhaps nice to give Mr. Stephen ‘Gates’ his real name back? After all “The New Capitalists: How Citizen Investors Are Reshaping The Business Agenda” was written by Stephen DAVIS. I think he would like the recognition ;)

Supported By:

Subscribe or Follow

Program on corporate governance advisory board.

- William Ackman

- Peter Atkins

- Kerry E. Berchem

- Richard Brand

- Daniel Burch

- Arthur B. Crozier

- Renata J. Ferrari

- John Finley

- Carolyn Frantz

- Andrew Freedman

- Byron Georgiou

- Joseph Hall

- Jason M. Halper

- David Millstone

- Theodore Mirvis

- Maria Moats

- Erika Moore

- Morton Pierce

- Philip Richter

- Elina Tetelbaum

- Marc Trevino

- Steven J. Williams

- Daniel Wolf

HLS Faculty & Senior Fellows

- Lucian Bebchuk

- Robert Clark

- John Coates

- Stephen M. Davis

- Allen Ferrell

- Jesse Fried

- Oliver Hart

- Howell Jackson

- Kobi Kastiel

- Reinier Kraakman

- Mark Ramseyer

- Robert Sitkoff

- Holger Spamann

- Leo E. Strine, Jr.

- Guhan Subramanian

- Roberto Tallarita

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4 Ethics and Social Responsibility

Learning objectives.

- Define business ethics and explain what it means to act ethically in business.

- Explain why we study business ethics.

- Identify ethical issues that you might face in business, such as insider trading, conflicts of interest, and bribery, and explain rationalizations for unethical behavior.

- Identify steps you can take to maintain your honesty and integrity in a business environment.

- Define corporate social responsibility and explain how organizations are responsible to their stakeholders, including owners, employees, customers, and the community.

- Discuss how you can identify an ethical organization, and how organizations can prevent behavior like sexual harassment.

- Learn how to avoid an ethical lapse, and why you should not rationalize when making decisions.

Introduction

“mommy, why do you have to go to jail”.

The one question Betty Vinson would have preferred to avoid is “Mommy, why do you have to go to jail?” [1] Vinson graduated with an accounting degree from Mississippi State and married her college sweetheart. After a series of jobs at small banks, she landed a mid-level accounting job at WorldCom, at the time still a small long-distance provider. Sparked by the telecom boom, however, WorldCom soon became a darling of Wall Street, and its stock price soared. Now working for a wildly successful company, Vinson rounded out her life by reading legal thrillers and watching her daughter play soccer.

Her moment of truth came in mid-2000, when company executives learned that profits had plummeted. They asked Vinson to make some accounting adjustments to boost income by $828 million. Vinson knew that the scheme was unethical (at the very least) but she gave in and made the adjustments. Almost immediately, she felt guilty and told her boss that she was quitting. When news of her decision came to the attention of CEO Bernard Ebbers and CFO Scott Sullivan, they hastened to assure Vinson that she’d never be asked to cook any more books. Sullivan explained it this way: “We have planes in the air. Let’s get the planes landed. Once they’ve landed, if you still want to leave, then leave. But not while the planes are in the air.” [2] Besides, she’d done nothing illegal, and if anyone asked, he’d take full responsibility. So Vinson decided to stay. After all, Sullivan was one of the top CFOs in the country; at age 37, he was already making $19 million a year. [3] Who was she to question his judgment? [4]

Six months later, Ebbers and Sullivan needed another adjustment—this time for $771 million. This scheme was even more unethical than the first: it entailed forging dates to hide the adjustment. Pretty soon, Vinson was making adjustments on a quarterly basis—first for $560 million, then for $743 million, and yet again for $941 million. Eventually, Vinson had juggled almost $4 billion, and before long, the stress started to get to her: she had trouble sleeping, lost weight, and withdrew from people at work. She decided to hang on when she got a promotion and a $30,000 raise.

By spring 2002, however, it was obvious that adjusting the books was business as usual at WorldCom. Vinson finally decided that it was time to move on, but, unfortunately, an internal auditor had already put two and two together and blown the whistle. The Securities and Exchange Commission charged WorldCom with fraud amounting to $11 billion—the largest in US history. Seeing herself as a valuable witness, Vinson was eager to tell what she knew. The government, however, regarded her as more than a mere witness. When she was named a co-conspirator, she agreed to cooperate fully and pleaded guilty to criminal conspiracy and securities fraud. But she won’t be the only one doing time: Scott Sullivan will be in jail for five years, and Bernie Ebbers will be locked up for 25 years. Both maintain that they are innocent. [5]

So where did Betty Vinson, mild-mannered midlevel executive and mother, go wrong? How did she manage to get involved in a scheme that not only bilked investors out of billions but also cost 17,000 people their jobs? [6] Ultimately, of course, we can only guess. Maybe she couldn’t say no to her bosses; perhaps she believed that they’d take full responsibility for her accounting “adjustments.” Possibly she was afraid of losing her job or didn’t fully understand the ramifications of what she was doing. What we do know is that she disgraced herself and went to jail. [7]

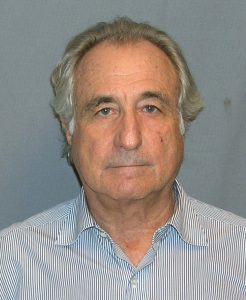

The WorldCom situation is not an isolated incident. Perhaps you have heard of Bernie Madoff, founder of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities and former chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange. [8] Madoff is alleged to have run a giant Ponzi scheme [9] that cheated investors of up to $65 billion. His wrongdoings won him a spot at the top of Time Magazine’s Top 10 Crooked CEOs. According to the SEC charges, Madoff convinced investors to give him large sums of money. In return, he gave them an impressive 8–12 percent return a year. But Madoff never really invested their money. Instead, he kept it for himself. He got funds to pay the first investors their return (or their money back if they asked for it) by bringing in new investors. Everything was going smoothly until the fall of 2008, when the stock market plummeted and many of his investors asked for their money. As he no longer had it, the game was over and he had to admit that the whole thing was just one big lie. Thousands of investors, including many of his wealthy friends, not-so-rich retirees who trusted him with their life savings, and charitable foundations, were financially ruined. Those harmed by Madoff either directly or indirectly were likely pleased when he was sentenced to jail for 150 years.

Headlines from more corporate scandals since 2015:

- In 2015, Volkswagen admitted cheating the United States emissions tests for diesel engines.

- In 2016, then Wells-Fargo CEO John Stumpf was fired for a scandal that included the creation of 1.5 million fake deposit accounts and more than 500,000 fake credit cards, all in customers’ names and without their permission. This was just the beginning of more scandals to be uncovered at one of the Top 5 largest banks in the United States. [10]

- In 2019, Facebook agrees to pay $5 billion to settle with the US Federal Trade Commission over privacy and data concerns. [11]

What can government, business and/or society do to reduce these types of ethical scandals?

Business Ethics

The idea of business ethics.

It’s in the best interest of a company to operate ethically. Trustworthy companies are better at attracting and keeping customers, talented employees, and capital. Those tainted by questionable ethics suffer from dwindling customer bases, employee turnover, and investor mistrust.

Let’s begin this section by addressing this question: What can individuals, organizations, and government agencies do to foster an environment of ethical behavior in business? First, of course, we need to define the term.

What Is Ethics?

You probably already know what it means to be ethical : to know right from wrong and to know when you’re practicing one instead of the other. We can say that business ethics is the application of ethical behavior in a business context. Acting ethically in business means more than simply obeying applicable laws and regulations: It also means being honest, doing no harm to others, competing fairly, and declining to put your own interests above those of your company, its owners, and its workers. If you’re in business you obviously need a strong sense of what’s right and wrong. You need the personal conviction to do what’s right, even if it means doing something that’s difficult or personally disadvantageous.

Why Study Ethics?

Ideally, prison terms, heavy fines, and civil suits would discourage corporate misconduct, but, unfortunately, many experts suspect that this assumption is a bit optimistic. Whatever the condition of the ethical environment in the near future, one thing seems clear: the next generation entering business—which includes most of you—will find a world much different than the one that waited for the previous generation. For example, cyberethics and how user behavior and programmed computers might impact people and society. Recent history tells us in no uncertain terms that today’s business students, many of whom are tomorrow’s business leaders, need a much sharper understanding of the difference between what is and isn’t ethically acceptable. As a business student, one of your key tasks is learning how to recognize and deal with the ethical challenges that will confront you. Asked what he looked for in a new hire, Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway and one of the world’s most successful investor, replied: “I look for three things. The first is personal integrity, the second is intelligence, and the third is a high energy level.” He paused and then added, “But if you don’t have the first, the second two don’t matter.” [12]

Identifying Ethical Issues and Dilemmas

Ethical issues are the difficult social questions that involve some level of controversy over what is the right thing to do. Environmental protection is an example of a commonly discussed ethical issue, because there can be trade offs between environmental and economic factors.

Ethical dilemmas are situations in which it is difficult for an individual to make decisions either because the right course of action is unclear or carries some potential negative consequences for the person or people involved.

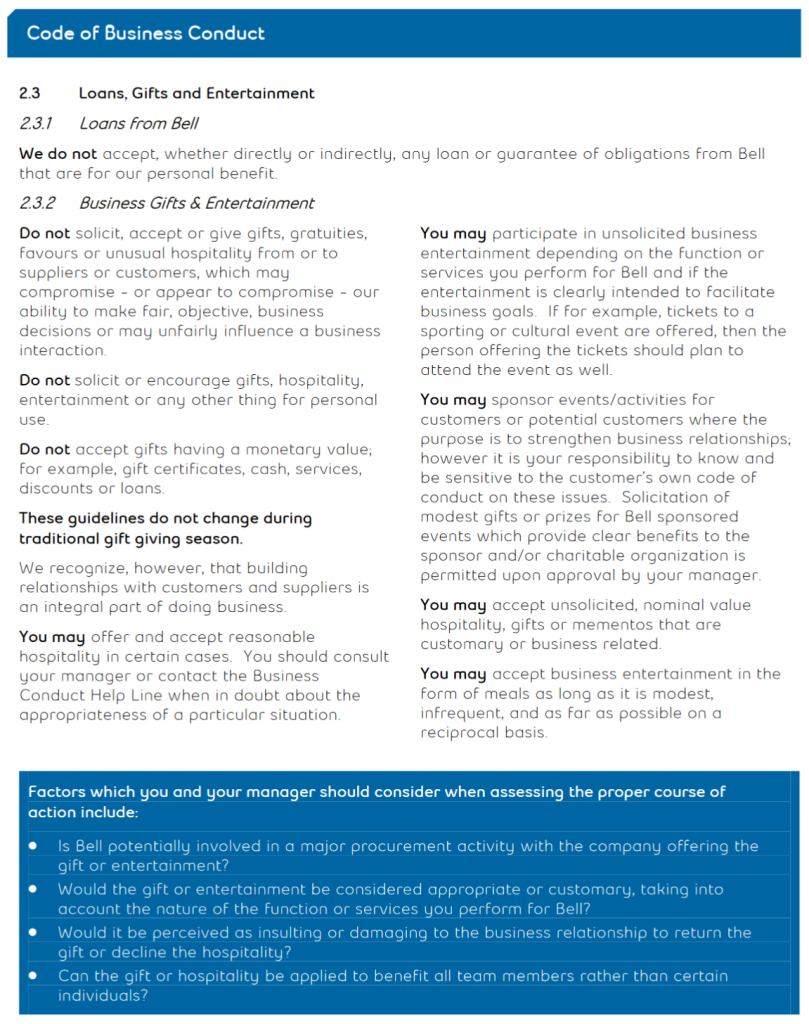

Make no mistake about it: when you enter the business world, you’ll find yourself in situations in which you’ll have to choose the appropriate behavior. How, for example, would you answer questions like the following?

- Is it OK to accept a pair of sports tickets from a supplier?

- Can I buy office supplies from my brother-in-law?

- Is it appropriate to donate company funds to a local charity?

- If I find out that a friend is about to be fired, can I warn her?

Obviously, the types of situations are numerous and varied. Fortunately, we can break them down into a few basic categories: issues of honesty and integrity, conflicts of interest and loyalty, bribes versus gifts, and whistle-blowing. Let’s look a little more closely at each of these categories.

Issues of Honesty and Integrity

Master investor Warren Buffet once told a group of business students the following: “I cannot tell you that honesty is the best policy. I can’t tell you that if you behave with perfect honesty and integrity somebody somewhere won’t behave the other way and make more money. But honesty is a good policy. You’ll do fine, you’ll sleep well at night and you’ll feel good about the example you are setting for your coworkers and the other people who care about you.” [13]

If you work for a company that settles for its employees’ merely obeying the law and following a few internal regulations, you might think about moving on. If you’re being asked to deceive customers about the quality or value of your product, you’re in an ethically unhealthy environment.

Think About This Story:

“A chef put two frogs in a pot of warm soup water. The first frog smelled the onions, recognized the danger, and immediately jumped out. The second frog hesitated: The water felt good, and he decided to stay and relax for a minute. After all, he could always jump out when things got too hot (so to speak). As the water got hotter, however, the frog adapted to it, hardly noticing the change. Before long, of course, he was the main ingredient in frog-leg soup.” [14]

So, what’s the moral of the story? Don’t sit around in an ethically toxic environment and lose your integrity a little at a time; get out before the water gets too hot and your options have evaporated. Fortunately, a few rules of thumb can guide you.

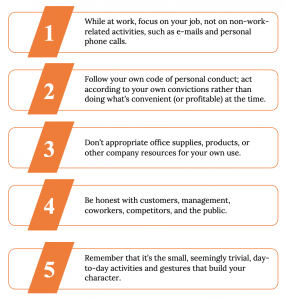

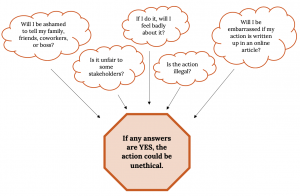

We’ve summed them up in Figure 4.2.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest occur when individuals must choose between taking actions that promote their personal interests over the interests of others or taking actions that don’t. A conflict can exist, for example, when an employee’s own interests interfere with, or have the potential to interfere with, the best interests of the company’s stakeholders (management, customers, and owners). Let’s say that you work for a company with a contract to cater events at your college and that your uncle owns a local bakery. Obviously, this situation could create a conflict of interest (or at least give the appearance of one—which is a problem in itself). When you’re called on to furnish desserts for a luncheon, you might be tempted to send some business your uncle’s way even if it’s not in the best interest of your employer. What should you do? You should disclose the connection to your boss, who can then arrange things so that your personal interests don’t conflict with the company’s.

The same principle holds that an employee shouldn’t use private information about an employer for personal financial benefit. Say that you learn from a coworker at your pharmaceutical company that one of its most profitable drugs will be pulled off the market because of dangerous side effects. The recall will severely hurt the company’s financial performance and cause its stock price to plummet. Before the news becomes public, you sell all the stock you own in the company. What you’ve done is called insider trading —acting on information that is not available to the general public, either by trading on it or providing it to others who trade on it. Insider trading is illegal, and you could go to jail for it.

Conflicts of Loyalty

You may one day find yourself in a bind between being loyal either to your employer or to a friend or family member. Perhaps you just learned that a coworker, a friend of yours, is about to be downsized out of his job. You also happen to know that he and his wife are getting ready to make a deposit on a house near the company headquarters. From a work standpoint, you know that you shouldn’t divulge the information. From a friendship standpoint, though, you feel it’s your duty to tell your friend. Wouldn’t he tell you if the situation were reversed? So what do you do? As tempting as it is to be loyal to your friend, you shouldn’t tell. As an employee, your primary responsibility is to your employer. You might be able to soften your dilemma by convincing a manager with the appropriate authority to tell your friend the bad news before he puts down his deposit.

Bribes vs. Gifts

It’s not uncommon in business to give and receive small gifts of appreciation, but when is a gift unacceptable? When is it really a bribe ?

There’s often a fine line between a gift and a bribe. The following information may help in drawing it, because it raises key issues in determining how a gesture should be interpreted: the cost of the item, the timing of the gift, the type of gift, and the connection between the giver and the receiver. If you’re on the receiving end, it’s a good idea to refuse any item that’s overly generous or given for the purpose of influencing a decision. Because accepting even small gifts may violate company rules, always check on company policy.

Google’s “Code of Conduct,” for instance, has an entire section on avoiding conflicts of interest. They outline where these conflicts might occur, such as accepting gifts, personal investments, and outside employment, and provide guidelines: “In each of these situations, the rule is the same—if you are considering entering into a business situation that creates a conflict of interest, don’t. If you are in a business situation that may create a conflict of interest, or the appearance of a conflict of interest, review the situation with your manager and Ethics & Compliance.” [15]

Whistle-Blowing

As we’ve seen, the misdeeds of Betty Vinson and her accomplices at WorldCom didn’t go undetected. They caught the eye of Cynthia Cooper, the company’s director of internal auditing. Cooper, of course, could have looked the other way, but instead she summoned up the courage to be a whistle-blower —an individual who exposes illegal or unethical behavior in an organization. Like Vinson, Cooper had majored in accounting at Mississippi State and was a hard-working, dedicated employee. Unlike Vinson, however, she refused to be bullied by her boss, CFO Scott Sullivan. In fact, she had tried to tell not only Sullivan but also auditors from the Arthur Andersen accounting firm that there was a problem with WorldCom’s books. The auditors dismissed her warnings, and when Sullivan angrily told her to drop the matter, she started cleaning out her office. But she didn’t relent. She and her team worked late each night, conducting an extensive, secret investigation. Two months later, Cooper had evidence to take to Sullivan, who told her once again to back off. Again, however, she stood up to him, and though she regretted the consequences for her WorldCom coworkers, she reported the scheme to the company’s board of directors. Within days, Sullivan was fired and the largest accounting fraud in history became public. [16]

As a result of Cooper’s actions, executives came clean about the company’s financial situation. The conspiracy of fraud was brought to an end, and though public disclosure of WorldCom’s problems resulted in massive stock-price declines and employee layoffs, investor and employee losses would have been greater without Cooper’s intervention. Even though Cooper did the right thing, and landed on the cover of Time magazine for it, the experience wasn’t exactly gratifying.

A lot of people applauded her action, but many coworkers shunned her; some even blamed her for the company’s troubles. [17]

Whistle-blowing is sometimes career suicide. A survey of 200 whistle-blowers conducted by the National Whistleblower Center found that half were fired for blowing the whistle. [18] Even those who keep their jobs can experience repercussions. As long as they stay, some will treat them (as one whistle-blower put it) “like skunks at a picnic”; if they leave, they may be blackballed in the industry. [19] On a positive note, new Federal laws have been passed which are intended to protect whistle-blowers.

For her own part, Cynthia Cooper doesn’t regret what she did. As she told a group of students at Mississippi State: “Strive to be persons of honor and integrity. Do not allow yourself to be pressured. Do what you know is right even if there may be a price to be paid.” [20] If your company tells employees to do whatever it takes, push the envelope, look the other way, and “be sure that we make our numbers,” you have three choices: go along with the policy, try to change things, or leave. If your personal integrity is part of the equation, you’re probably down to the last two choices. [21]

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward different stakeholders when making legal, economic, ethical, and social decisions. Remember that we previously defined stakeholders as those with a legitimate interest in the success or failure of the business and the policies it adopts. The term social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward their various stakeholders.

What motivates companies to be “socially responsible”? We hope it’s because they want to do the right thing, and for many companies, “doing the right thing” is a key motivator. The fact is, it’s often hard to figure out what the “right thing” is: what’s “right” for one group of stakeholders isn’t necessarily just as “right” for another. One thing, however, is certain: companies today are held to higher standards than ever before. Consumers and other groups consider not only the quality and price of a company’s products but also its character. If too many groups see a company as a poor corporate citizen, it will have a harder time attracting qualified employees, finding investors, and selling its products. Good corporate citizens, by contrast, are more successful in all these areas.

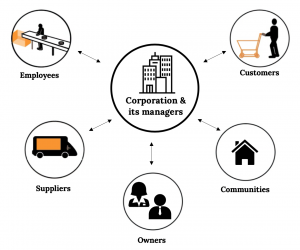

Figure 4.3 presents a model of corporate responsibility based on a company’s relationships with its stakeholders. In this model, the focus is on managers —not owners—as the principals involved in these relationships. Owners or shareholders are the stakeholders who invest risk capital in the firm in expectation of a financial return. Other stakeholders include employees , suppliers , and the communities in which the firm does business. Proponents of this model hold that customers, who provide the firm with revenue, have a special claim on managers’ attention. The arrows indicate the two-way nature of corporation-stakeholder relationships: All stakeholders have some claim on the firm’s resources and returns, and management’s job is to make decisions that balance these claims. [22]

Let’s look at some of the ways in which companies can be “socially responsible” in considering the claims of various stakeholders.

Owners or shareholders invest money in companies. In return, the people who run a company have a responsibility to increase the value of owners’ investments through profitable operations. Managers also have a responsibility to provide owners (as well as other stakeholders having financial interests, such as creditors and suppliers) with accurate, reliable information about the performance of the business. Clearly, this is one of the areas in which WorldCom managers fell down on the job. Upper-level management purposely deceived shareholders by presenting them with fraudulent financial statements

Managers have what is known as a fiduciary responsibility to owners: they’re responsible for safeguarding the company’s assets and handling its funds in a trustworthy manner. Yet managers experience what is called the agency problem; a situation in which their best interests do not align with those of the owners who employ them. To enforce managers’ fiduciary responsibilities for a firm’s financial statements and accounting records, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires CEOs and CFOs to attest to their accuracy. The law also imposes penalties on corporate officers, auditors, board members, and any others who commit fraud. You’ll learn more about this law in your accounting and business law courses.

Companies are responsible for providing employees with safe, healthy places to work—as well as environments that are free from sexual harassment and all types of discrimination. They should also offer appropriate wages and benefits. In the following sections, we’ll take a closer look at these areas of corporate responsibility.

Wages and Benefits

At the very least, employers must obey laws governing minimum wage and overtime pay. A minimum wage is set by the federal government, though states can set their own rates as long as they are higher. The current federal rate, for example, is $7.25, while the rate in many states is far higher. By law, employers must also provide certain benefits —social security (retirement funds), unemployment insurance (protects against loss of income in case of job loss), and workers’ compensation (covers lost wages and medical costs in case of on-the-job injury). Most large companies pay most of their workers more than minimum wage and offer broader benefits, including medical, dental, and vision care, as well as savings programs, in order to compete for talent. Companies may also pay a living wage, which is a sufficient wage that covers the basic cost of living for a specific location. [23]

Safety and Health

Though it seems obvious that companies should guard workers’ safety and health , some simply don’t. For over four decades, for example, executives at Johns Manville suppressed evidence that one of its products, asbestos, was responsible for the deadly lung disease developed by many of its workers. [24] The company concealed chest X-rays from stricken workers, and executives decided that it was simply cheaper to pay workers’ compensation claims than to create a safer work environment. A New Jersey court was quite blunt in its judgment: Johns Manville, it held, had made a deliberate, cold-blooded decision to do nothing to protect at-risk workers, in blatant disregard of their rights. [25]

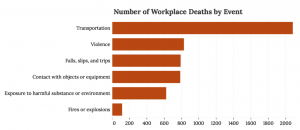

About four in 100,000 US workers die in workplace “incidents” each year. The Department of Labor categorizes deaths caused by conditions like those at Johns Manville as “exposure to harmful substances or environments.” How prevalent is this condition as a cause of workplace deaths? See Figure 4.4, “Workplace Deaths by Event or Exposure (2018),” which breaks down workplace fatalities by cause. Some jobs are more dangerous than others. For a comparative overview based on workplace deaths by occupation, see Figure 4.5.

| Transportation and material moving | 28% |

| Construction and extraction | 19% |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 8% |

| Management | 7% |

| Building and grounds cleaning/maintenance | 7% |

| Protective service | 5% |

| Farming, fishing, and forestry | 5% |

| Sales | 5% |

| Production | 4% |

| Food preparation and serving | 2% |

Fortunately for most people, things are far better than they were at Johns Manville. Procter & Gamble (P&G), for example, considers the safety and health of its employees paramount and promotes the attitude that “Nothing we do is worth getting hurt for.” With nearly 100,000 employees worldwide, P&G uses a measure of worker safety called “total incident rate per employee,” which records injuries resulting in loss of consciousness, time lost from work, medical transfer to another job, motion restriction, or medical treatment beyond first aid. The company attributes the low rate of such incidents—less than one incident per hundred employees—to a variety of programs to promote workplace safety. [26]