Clinical Cases

Litfl clinical cases database.

The LITFL Clinical Case Collection includes over 250 Q&A style clinical cases to assist ‘ Just-in-Time Learning ‘ and ‘ Life-Long Learning ‘. Cases are categorized by specialty and can be interrogated by keyword from the Clinical Case searchable database.

Search by keywords; disease process; condition; eponym or clinical features…

| Topic | Title | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| ECG | ||

| ECG | WCT, ECG, Broad complex, fascicular, RVOT | |

| Toxicology | valproate, valproic acid, hyperammonemia | |

| Toxicology | valproate, valproic acid, hyperammonemia | |

| Toxicology | ||

| Metabolic | priapsim, intracavernosal, cavernosal gas, Ischaemic priapism, stuttering priapism, urology | |

| Metabolic | RTA, strong ion difference, hypocalcaemia | |

| Bone and Joint | DRUJ, dislcoation | |

| ICE | wellens, ECG, cardiac, delay | |

| ICE | SJS, stevens-johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, rash | |

| ICE | pneumothorax | |

| ICE | ||

| ICE | tibia, fracture, toddler, toddler's fracture | |

| ICE | ECG, EKG, hyperkalaemia, hyperkalemia | |

| ICE | dengue, returned traveler, traveller | |

| ICE | Lisfranc | |

| ICE | mountain, mount everest, alkalaemia, alkalemia | |

| ICE | pancreatitis, alcohol | |

| ICE | segond fracture | |

| ICE | Brugada | |

| ICE | STEMI, hyperacture, myocardial ischemia, anterior | |

| ICE | eryhthema nodosum, panniculitis | |

| ICE | BOS fracture, battle sign, mastoid ecchymosis, bruising | |

| ICE | Galleazi, fracture dislocation | |

| Toxicology | methylene blue, Methaemoglobinemia, methemoglobin | |

| Toxicology | clozapine | |

| Toxicology | Methamphetamine, body stuffing, body packer, body stuffer | |

| Toxicology | TCA, tricyclic, overdose, sodium channel blockade | |

| Toxicology | alprazolam, BZD, benzo, benzodiazepine, benzodiazepines, flumazenil | |

| Toxicology | lithium, neurotoxicity, acute toxicity | |

| Toxicology | baclofen, GABA, Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate, GHB | |

| Toxicology | Carbamazepine, toxidrome, carbamazepine cardiotoxicity, Tegretol, multiple-dose activated charcoal, MDAC | |

| Toxicology | Hepatotoxicity, Acetaminophen, Schiodt score, hepatic encephalopathy, N-acetylcysteine, NAC | |

| Toxicology | beta-blocker, B Blocker, | |

| Toxicology | Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome, cyclical vomiting, THC, delta-nine-tetrahydrocannabinol | |

| Toxicology | Colchicine | |

| Toxicology | Clonidine | |

| Toxicology | Bath salts | |

| Toxicology | Mephedrone | |

| Toxicology | Bromo-DragonFLY, M-ket, Kmax, Mexxy, Meow-Meow, Mephedrone, Methoxetamine, Naphyrone, NRG-1, Salvia, K2, Spice | |

| Toxicology | ixodes holocyclus, tick, paralysis, | |

| Toxicology | cyanide, carbon monoxide | |

| Toxicology | hypoglycemia | |

| Toxicology | Ciguatera, Scombroid, fugu, puffer fish | |

| Toxicology | ethylene glycol, HAGMA, high anion gap metabolic acidosis, osmolar gap, Fomepizole, alcohol, ethanol | |

| Toxicology | iron toxicity, Desferrioxamine chelation therapy | |

| Toxicology | chloroquine | |

| Toxicology | corrosive agent | |

| Toxicology | Antidote | |

| Toxicology | Oculogyric crisis, OGC, acute dystonia, Acute Dystonic Reaction, butyrophenone, Metoclopramide, haloperidol, prochlorperazine, Benztropine | |

| Toxicology | Tricyclic, Theophylline, Sulfonylureas, Propanolol, Opioids, Dextropropoxyphene, Chloroquine, Calcium channel blockers, Amphetamines, ectasy | |

| Toxicology | verapamil, calcium channel blocker, cardiotoxic, HIET, high-dose insulin euglycemic therapy, | |

| Toxicology | aroma, smell | |

| Toxinology | snake-bite, snake bite, Brown snake, Black, Death adder, Taipan, sea snake, tiger | |

| Toxicology | Anticholinergic syndrome, Malignant hyperthermia, Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, Serotonin toxicity | |

| Toxicology | Serotonin toxicity, Serotonin syndrome, toxidrome | |

| Toxicology | proconvulsive, venlafaxine, tramadol, amphetamines, Bupropion, Otis Campbell | |

| Toxicology | TCA, tricyclic, overdose, sodium channel blockade, Amitriptyline | |

| Toxicology | anticoagulation, warfarin | |

| Toxicology | Mickey Finn, pear, | |

| Toxicology | thyrotoxic storm, Thyroxine, T4 | |

| Toxinology | white-tailed spider, Lampona, L. cylindrata, L. murina | |

| Toxicology | Citalopram, SSRI, | |

| Toxicology | warfarin | |

| Toxicology | warfarin, accidental ingestion, toddler | |

| Toxicology | ||

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming | |

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming, penetrating, barb, steve irwin, | |

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming, Blue-Ringed Octopus, BRO, Hapalochlaena | |

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Chironex fleckeri, Box Jellyfish | |

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Jack Barnes, Carukia barnesi, Irukandji Syndrome, Darwin | |

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Jack Barnes, Carukia barnesi, Irukandji Syndrome | |

| Toxicology | Strychnine, opisthotonus, risus sardonicus | |

| Toxicology | naloxone, Buprenorphine | |

| Toxinology | snake-bite, snake bite, SVDK | |

| Toxinology | Red back spider, redback, envenoming, RBS | |

| Toxinology | Red back spider, redback, envenoming, RBS | |

| Toxicology | ||

| Toxicology | Acetaminophen, N-acetylcysteine, NAC | |

| Pediatric |

| Henoch-Schonlein Purpura, HSP, Henoch-Schönlein |

| Pediatric |

| adrenal insufficiency, glucocorticoid deficiency, NAGMA, endocrine emergency |

| Pediatric |

| Penile Zipper Entrapment, foreskin, release, Zip |

| Pediatric |

| diarrohea, vomiting, hypokalemia, hypokalaemia, dehydration |

| Pediatric |

| infantile colic, TIM CRIES, crying baby |

| Pediatric |

| Pyloric stenosis, projectile vomit, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, HPS, Rankin |

| Pediatric |

| respiratory distress, wheeze, foreign body, RMB, CXR, right main bronchus |

| Pediatric |

| airway obstruction, stridor, severe croup, harsh cough, heliox, intubation, sevoflurane |

| Pediatric |

| boot-shaped, TOF, coeur en sabot, Tetralogy of Fallot |

| Pediatric |

| Spherocytes, Shistocytes, Polychromasia, reticulocytosis, anemia, anaemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, HUS |

| Pediatric |

| Reye syndrome, ammonia, metabolic encephalopathy, aspirin |

| Pediatric |

| Ketamine, procedural sedation, pediatric sedation |

| Pediatric |

| Foreign Body, ketamine, laryngospasm, Larson's point, laryngospasm notch |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, eye trauma, Eyelid laceration, lacrimal punctum |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Retrobulbar hemorrhage, haemorrhage, RAPD, lateral canthotomy, DIP-A CONE-G, cantholysis |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, corneal abrasion, eye trauma, eyelid eversion |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, commotio retinae, eye trauma, traumatic eye injury |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Traumatic iritis, hyphaema, hyphema, |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, lens dislocation, Anterior dislocation of an intraocular lens |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, visual loss, loss of vision , blind |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Central retinal vein occlusion, CRVO, branch retinal vein occlusion, BRVO |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Central retinal artery occlusion, CRAO, cherry red spot, Branch retinal artery occlusion, BRAO |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, miosis, partial ptosis, anhidrosis, enophthalmos, horner |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, visual loss, Amaurosis fugax, TIA, transient ischemic attack |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Pre-septal cellulitis, preseptal cellulitis, peri-orbital cellulitis, Post-septal cellulitis, post septal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, AION, giant cell arteritis, GCA, Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Herpes simplex keratitis, dendritic ulcer |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Conjunctival injection, conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis, Adenovirus, trachoma, bacterial, viral, Parinaud oculoglandular conjunctivitis |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Chemical injury, cement, alkali, burn, chemical conjunctivitis, colliquative necrosis, liquefactive |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Ultraviolet keratitis, keratopathy, solar keratitis, photokeratitis, welder's flash, arc eye, bake eyes snow blindness. |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Parinaud, adie, holmes, tabes dorsalis, neurosyphylis, argyll Robertson, small irregular |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, anterior Uveitis, HLA-B27, hypopyon |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, POCUS, ONSD, |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Blowout fracture, infraorbital fracture |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, endophthalmitis, sympathetic ophthalmia, penetrating eye trauma |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, tobacco dust, Posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous debris, retinal tear, retinal break, Washer Machine Sign, Eales disease |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, dendriform keratitis, Hutchinson sign |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Siedel, FB, rust ring, Corneal foreign body, Seidel test |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Papilloedema, Papilledema, pseudopapilloedema |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, optic disc, optic neuritis, Marcus-Gunn, papillitis, multiple sclerosis, funduscopy, optic atrophy, papilledema |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, retinal break, POCUS, retinoschisis, Retinal detachment |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, cupping, glaucoma, optic neuropathy, tonometry, intraocular pressure, open angle, closed angle, gonioplasty, Acute closed-angle glaucoma |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Subconjunctival hemorrhage |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Meibomitis, blepharitis, entropion, ectropion, canaliculitis, dacryocystitis |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, blepharospasm, blink, blinking |

| EYE |

| Iritis, keratitis, acute angle-closure glaucoma, scleritis, orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) |

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, fixed, dilated, pupil, holmes-adie, glass eye |

| ECG |

| Wenckebach, AV block, SA, deliberate mistake, SA block |

| ECG |

| dual chamber AV sequential pacemaker |

| ECG |

| anterior AMI, De Winter T waves, LAD stenosis |

| ECG |

| LMCA Stenosis, ST elevation in aVR, Left Main Coronary Artery |

| ECG |

| LMCA, Left Main Coronary Artery Occlusion, ST elevation in aVR |

| ECG |

| VT, BCT, WCT, Brugada criteria, Verekie |

| ECG |

| severe hypokalaemia, spironalactone, rhabdomyolysis, ECG, u wave, diabetic ketoacidosis |

| ECG |

| pacing, pacemaker, post-op, Mobitz I, Wenckebach, AV block |

| ECG |

| bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia, CPVT, digoxin toxicity |

| ECG |

| congenital, short QT syndrome, SQTS, AF, Atrial fibrillation |

| ECG |

| RVOT, broad complex tachycardia, BCT, Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Tachycardia, VF, Arrest, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, ARVC |

| ECG |

| NSTEMI, inverted U wave, |

| ECG |

| tricyclic antidepressant, TCA, Doxepin, QRS broadening, cardiotoxic |

| ECG |

| AIVR, Accelerated idioventricular rhythm, Isorhythmic AV dissociation, Sinus arrhythmia, idioventricular |

| ECG |

| LAD, LBBB, High left ventricular voltage, HLVV, WPW, Broad Complex Tachycardia |

| ECG |

| tachy-brady, AVNRT, flutter, polymorphic VT, VF, torsades de pointes, R on T, Cardioversion |

| ECG |

| LBBB, Wellens, ECG, proximal LAD, occlusion, rate-dependent, inferior ischaemia |

| ECG |

| SI QIII TIII, PE, PTE pulmonary embolism, PEA arrest, RBBB, LAD |

| Cardiology |

| HOCM, STE, aVR, LMCA, torsades des pointes. TDP |

| Cardiology |

| aortic arch, right sided, diverticulum of Kommerell |

| Cardiology |

| IABP, CABG, shock, circulatory collapse |

| Cardiology |

| electrical alternans, ECG, pulsus paradoxus |

| Cardiology |

| Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, Waveform, dicrotic notch |

| Cardiology |

| DeBakey, TAA, aortic dissection, CTA |

| Cardiology |

| Tetraology of Fallot, BT shunt, Blalock-Tausig, ToF |

| Cardiology |

| PVP, cement, embolus, Percutaneous Vertebroplasty |

| Cardiology |

| Pulmonary Embolism, PTE, PE, McConnell, thrombolysis, echo |

| Bone and Joint |

| Missed posterior shoulder dislocation |

| Paediatrics |

| rash, neck nodule, Kawasaki |

| Paediatrics |

| rash, fever, scarlet, strawberry, Group A Beta Haemolytic Streptococci (GABHS) |

| Tropical Travel |

| diphtheria, pseudomembrance, grey tonsils, pseudomembrane, tonsillitis, diphtheria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, gram-positive bacillus |

| Urinalysis |

| purple, urine, indican, indican |

| Urinalysis |

| brown, urine, rhabdomyolysis |

| Urinalysis |

| green, urine, propofol, PRIS |

| Urinalysis |

| green, urine |

| Urinalysis |

| orange, urine |

| Bone and Joint |

| Nail, trauma, hematoma, subungual, haematoma, nail-bed |

| Bone and Joint |

| Extensor tendon, hand injury, extensor digiti minimi, |

| Bone and Joint |

| Thumb, fracture, base, phalanx, metacarpal, Edward Hallaran Bennett, bipartate |

| Paediatrics |

| Food allergy, enterocolitis, |

| Bone and Joint |

| FOOSH, wrist fracture, FOOSH - 'fall onto outstretched hand', Barton fracture, John Rhea Barton |

| Paediatrics |

| pulled elbow, nursemaid, hyperpronation |

| Cardiology |

| Phlegmasia, dolens |

| Cardiology |

| ICC, intercostal, intra-cardiac, iatrogenic |

| Bone and Joint |

| Compartment syndrome, Volkmann, fasciotomy |

| Bone and Joint |

| Ankle, compound, fracture, dislocation, Six Hour Golden Rule, saline, iodine |

| ENT |

| retropharngeal abscess, posterior pharynx, mediastinitis, Lemierre syndrome, Fusobacterium necrophorum |

| ENT |

| enlarged tonsils, pharyngitis, tonsillitis |

| Toxicology | Colgout, colchicine, label, fenofibrate | |

| Tropical Travel | Mary Mallon, Salmonella typhi, typhoid, typhoid mary | |

| Tropical Travel | Dengue Fever, single-stranded RNA virus, Aedes, mosquito, Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS), Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF) | |

| Tropical Travel | AIDS, Human immunodeficiency virus, lentivirus, anti-retroviral, | |

| Tropical Travel | tuberculosis | |

| Tropical Travel | Falciparum, Vivax, Ovale, Malariae, Knowlesi, Plasmodium | |

| Tropical Travel | cholera, gram-negative comma-shaped bacillus, rice water stool, John Snow Pump, V. cholerae, vibrio | |

| Tropical Travel | Entamoeba histolytica, protozoan parasite, Amoebic dysentery, Flask Shaped amoebic trophozoite, Bloody stool, | |

| Tropical Travel | shigellosis, Shigella, Enterotoxin, dysentery, | |

| Tropical Travel | Tetanus, Tetanispasmin, Clostridium tetani, lock jaw, Opisthotonus, Autonomic dysfunction, toxoid | |

| Tropical Travel | Rabies Immunoglobulin | |

| Tropical Travel | Koplik, measles, rash, rubeola, Morbilivirus, | |

| Trauma | permissive hypotension, MBA, MVA, widened mediastinum, pleural effusion, ICC | |

| Trauma | knife, penetrating chest wound | |

| Trauma | knife, penetrating chest wound | |

| Trauma | TBSA %, Burns Wound Assessment, Total Body Surface Area | |

| Trauma | Arterial pressure index (API), DPI (Doppler Pressure Index), Arterial Brachial Index or Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) | |

| Trauma | crush injury, degloving, deglove, amputation | |

| Trauma | hip dislocation, Allis reduction, pelvic fracture | |

| Trauma | Pelvis fracture, stabilization, stabilisation, | |

| Trauma | pelvic stabilization, Pelvis fracture, stabilisation, Pre-peritoneal packing | |

| Trauma | massive transfusion protocol, Recombinant Factor VIIa, Thromboelastography (TEG) | |

| Trauma | Critical bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, haemorrhagic shock, lethal triad, acute coagulopathy of trauma | |

| Trauma | penetrating abdominal trauma | |

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | penetrating chest trauma wound, stab, | |

| Trauma | Right Main Bronchus, RMB, Tracheostomy, Tooth, foreign Body | |

| Trauma | Lobar collapse, aspiration, blood clot | |

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm with strangulation of viscera | |

| Trauma | eschar, burns, full thickness, | |

| Trauma | supine hypotension syndrome | |

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | iPhone | |

| Trauma | oleoma, lipogranuloma, | |

| Trauma | oral commissure, lingual artery hemorrhage, | |

| Trauma | polymer fume fever, dielectric heating, super-heating, thermal injury | |

| Trauma | DRE, Digital rectal exam examination trauma | |

| Trauma | Injury Severity score, ISS, golden hour, seatbelt sign | |

| Trauma | primary secondary survey | |

| Trauma | extradural hemorrhage, EDH, Monro-Kellie | |

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | ||

| Trauma | GU, trauma, penis, penile, urethra, bladder, rupture | |

| Pulmonary | swine flu, pneumomediastinum, CXR | |

| Pulmonary | Thrombocytopenia, antiphospholipid syndrome | |

| Pulmonary | Hermann Boerhaave, Boerhaave syndrome, esophagus rupture, oesophagus | |

| Pulmonary | ||

| Pulmonary | pneumococcal pneumonia, HIV, bronchoscope, anatomy, RMB | |

| Pulmonary | subcutaneous emphysema, FLAAARDS, | |

| Pulmonary | respiratory acidosis, hypercapnoea | |

| Pulmonary | hypersensivity pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar haemorrhage, alveolar infiltrates | |

| Pulmonary | Lung collapse, recruitment maneuver, bronchoscopy | |

| Pulmonary | Vocal cord dysfunction, VCD, paradoxical vocal cord motion, PVCM, posterior chinking | |

| Pulmonary | pneumococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin-resistant | |

| Pulmonary | DOPES, | |

| Pulmonary | asthma | |

| Pulmonary | dyssynchrony, mechanical ventilation, PEEP, Plateau pressure | |

| Pulmonary | pneumomediastinum, tracheostomy, trachy, complication | |

| Pulmonary | PERC rule, D-Dimer, Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria, HAD CLOTS, | |

| Pulmonary | AMS, acute mountain sickness, high altitude, High-altitude cerebral edema, HACE, HAPE, High-altitude pulmonary edema | |

| Pulmonary | ||

| Resus | Pulseless electrical activity, PEA | |

| Resus | intraosseous access, EZ-IO, | |

| Resus | ||

| Resus | Rocuronium, suxamethonium, succinylcholine, non-depolarising muscle relaxant, sugammadex, safe apnoea time | |

| Resus | FEAST, trial, research, pediatric, fluid resuscitation | |

| Resus | ||

| Resus | ||

| Resus | ||

| Resus | ICC, intercostal | |

| Resus | Mechanical ventilation | |

| Oncology | SVC obstruction | |

| Oncology | Tumour lysis syndrome, Tumor lysis syndrome | |

| Oncology | lung metastases braine mets testicular cancer BEP chemotherapy, Cannonball metastases | |

| Oncology | re-expansion pulmonary oedema edema | |

| Metabolic | abdominal aortic aneurysm, AAA, rupture, CT, rhabdomyolysis, creatine kinase | |

| Metabolic | hypokalemia, hypokalaemia, periodic paralysis, u wave | |

| Metabolic | CATMUDPILES, OGRE, NAGMA, HAGMA, USED CARP, hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis | |

| Metabolic | anion gap, pyroglutamic acidemia, HAGMA, high-anion gap, high anion, 5-oxoprolinemia, γ-glutamyl cycle, staph aureus, sepsis | |

| Metabolic | HAGMA, high-anion gap, high anion, hypernatraemia, hypernatremia | |

| Metabolic | hypokalaemia, hypokalemia, potassium, systemic bromism, coke, pepsi, coca-cola | |

| Metabolic | CATMUDPILES, renal failure, HAGMA, LTKR | |

| Metabolic | ||

| Metabolic | acute hepatitis, arterial blood gas, fulminant hepatic failure, lactic acidosis, lactic acidosis with hypoglycaemia, metabolic acidosis, metabolic muddle | |

| Metabolic | hyperammonaemia, hyperammonemia | |

| Metabolic | Hyponatraemia, hypertonic saline, ultramarathon, runner, EAH, pontine myelinoysis | |

| Metabolic | Hyponatraemia, hypertonic saline, pontine myelinoysis, Osmolality, desmopressin, SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone secretion | |

| Gastrointestinal | Appendagitis, Epiploic, Abdominal pain, CT abdomen | |

| Gastrointestinal | CT abdomen, Small bowel obstruction, SBO | |

| Gastrointestinal | cathine, cathione, khat, hepatitis, cathionine | |

| Gastrointestinal | rectal foreign body, FB | |

| Gastrointestinal | abdominal compartment syndrome, intra-abdominal pressure, intra-abdominal hypertension, IAH, ACS | |

| Hematology | fibrinolytic, VTE, Wells, PERC | |

| Hematology | factor VIIa, rFVIIa, novoseven | |

| Hematology | Critical Bleeding, Massive Transfusion, Tranexamic Acid, TxA, MTP | |

| Hematology | Dyshemoglobinemia, Acute myeloid leukemia, AML | |

| Immunological | angiodema, angioedema, lip sweliing | |

| Immunological | frusemide, furosemide, lasix, sulfa, | |

| Immunological | wegener, GPA, granulomatosis, palpable purpura | |

| Obstetric | amniotic fluid embolism, DIC, obstetric complication, disseminated intravascular coagulation, schistocytes, | |

| Microbial | CSF, Meningococcal meningitis, | |

| Microbial | fulminant bacterial pneumonia, septic shock, Pneumococcus, Streptococcus pyogenes, urinary pneumococcal antigen, | |

| Microbial | Legionella, community acquired pneumonia | |

| Microbial | Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, Toxic-shock syndrome | |

| Microbial | ||

| Microbial | ||

| Microbial | Norovirus | |

| Toxicology | Coma, similie, metaphor, flashcard, toxidromes, anticholinergic, cholinergic, PHAILS, OTIS CAMPBELL, PACED, FAST, COOLS, CT SCAN | |

| Neurology | HIV, Mass effect, CNS lesion, Brain lesion | |

| Neurology | pancoast, argyll robertson, holmes-adie, coma, pinpoint, pin-point, horner syndrome | |

| Neurology | rule of 4, rules of four, brainstem, weber syndrome, wallenberg | |

| Neurology | rule of 4, rules of four, brainstem, Nothnagel syndrome, benedikt, claude, | |

| Neurology | ||

| Neurology | ||

| Neurology | ||

| Neurology | Unilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, medial longitudinal fasciculus, MLF, INO, one-and-a-half syndrome | |

| Neurology | GSW, gunshot wound, bullet, TBI, Codman ICP monitor, Trans-cranial doppler, Near-infrared spectroscopy, NIRS, cerebral microdialysis catheter | |

| Neurology | BPPV, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, Dix-Hallpike test, semont, epley, dix hallpike, brandt-daroff | |

| Neurology | Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis, teratoma | |

| To err is human | cognitive error, bias, entrapment | |

| To err is human | rule of thumb, heuristic, satisficing, cognitive bias, metacognition | |

| To err is human | | Anchoring Bias, confirmation, satisficing, clustering bias |

| Cardiology | ||

| Paediatric | pediatric |

Compendium of Clinical Cases

LITFL Top 100 Self Assessment Quizzes

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Presentation and History

Chief Complaint: the patient’s wife is bringing the patient in after a fall at their home

Presentation:

J.S. a 50-year-old African American male who presents with his wife after he fell at home. After the fall, he told his wife “I will be fine, I think my vision just needs checked.” The patient reports, “I was walking very fast because I really had to pee and I accidentally ran into the table and got off balance. The next thing you know I was on the ground.” The patient reports having blurred vision for the past couple of months but just has not had the time to go to the eye doctor. His wife is more concerned about other changes she has noticed such as, J.S. has been waking up 3 times a night to go to the bathroom and he has had slight confusion and forgetfulness at times. J.S. thinks he has been using the bathroom more frequently because he has been so thirsty lately due to the warmer weather. When asked further about the fall the patient does report some tingling in both his feet occasionally. The patient’s wife also thinks her husband’s legs are getting weaker because he hasn’t been able to go on as long of a walk, like they normally do. She also expressed concern about a cut J.S. got on his leg that has not healed. The patient believes he got the cut about 2 months ago while mowing the lawn.

Past Medical History:

Obesity (1999)

GERD (2005)

Anxiety (2015)

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (2017)

Surgical History:

Appendectomy (1995)

Tonsillectomy (2017)

Pertinent family history:

Father—alive; type 2 diabetes, hypertension

Mother—hyperlipidemia, died of a stroke at age 70

Sister—alive, unremarkable medical history

Pertinent Social history:

J.S. works at a bank where he is primarily sitting at a desk all day. He reports gaining more weight recently so he and his wife have started going on walks around the neighborhood each night for exercise. He reports it is hard for him to eat healthy because he works long hours and “fast food is easy”. J.S. does report having “a bad smoking habit” of half a pack a day (12 pack years). He says it helps with his anxiety and stress of his job. The patient only reports social drinking (~2 drinks per week).

Current Medications:

Xanax-.5 mg BID

Prilosec-20 mg Daily

Assessment & Vitals:

Height: 5’9”

Weight: 255 lbs.

Temp: 98.7°F

P: 85 bpm, apically, regular rhythm

RR: 16 breaths/minute, unlabored

BP: 127/78 mmHg, left arm, sitting

Pain: patient reports no pain at this time

Skin: open cut on lower left leg ~2 inches in length, erythema surrounding cut, no drainage

Peripheral neurovascular: positive for tingling in bilateral lower extremities

Lab Results:

Lipid panel:

HDL: 45 mg/dL

LDL: 105 mg/dL

Triglycerides: 140 mg/dL

Total: 190 mg/dL

Fasting blood glucose: 240

TSH: 2.0 mU/L

Urine Analysis: normal except:

Glucose: 3.0 mmol/L

Chem 7: within normal limits

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2015

The importance of good history taking: a case report

- Durga Ghosh 1 &

- Premalatha Karunaratne 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 9 , Article number: 97 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Introduction

Early comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) with good history-taking is essential in assessing the older adult.

Case presentation

Our patient, a 75-year-old Caucasian woman, was originally admitted to hospital for investigation of iron deficiency anemia. During admission, she developed pneumonia and new intermittent atrial fibrillation in association with a right-sided weakness, which was felt to be new at the time.

Following this episode, she was treated for a further chest infection and, despite clinical improvement, her inflammatory markers failed to settle satisfactorily.

She was transferred to her local hospital for a period of rehabilitation where further neurological findings made the diagnosis of solely stroke questionable; these findings prompted further history-taking, investigations and input from other disciplines, thereby helping to arrive at a working diagnosis of vasculitic neuropathy.

Conclusions

The case aims to highlight the importance of taking a good history and performing an early comprehensive assessment in the older adult.

Good history-taking, an essential part of a comprehensive assessment in an older adult [ 1 ], helped reveal an underlying debilitating neuropathy.

Our patient, a 75-year-old Caucasian woman, was admitted to hospital for investigation of iron deficiency anemia in June 2013. Her hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit and mean cell volume (MCV) levels preadmission were 10.1g/dL, 0.33 and 77 fL, respectively.

There was little known about her past medical history aside from type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) requiring insulin, hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Investigation for iron deficiency anemia confirmed extensive diverticular disease with normal upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and duodenal biopsy.

During the same admission, she developed a hospital-acquired pneumonia and new intermittent atrial fibrillation.

Coinciding with this period, she developed a new dysphasia and what was perceived to be a ‘new’ right-sided weakness. A computed tomography (CT) brain scan showed no acute change and she was treated as a patient with ischemic stroke, given the clinical findings.

She was treated for a further pneumonia in hospital and also underwent investigations such as a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) scan, which ruled out pulmonary embolism but confirmed partial left lung collapse; subsequent bronchoscopy was negative for malignancy. Her inflammatory markers remained elevated with her C-reactive protein (CRP) level approximately 140 and white cell count (WCC) 14 but she remained mentally alert and made clinical improvement. Her repeat chest X-rays were also unchanged. Given the clinical improvement, she was deemed suitable for transfer for stroke rehabilitation to her local hospital in August 2013. Her medications on transfer were: Novomix 30 twice daily (later stopped due to low blood sugar levels); clopidogrel 75 mg; quinine sulphate 200 mg; ranitidine 150 mg twice daily; folic acid 5mg; and digoxin 125mcg.

In the Rehabilitation and Assessment Directorate (RAD), the assumption was that our patient had suffered a stroke causing a right-sided weakness, as per the handover pre-transfer, however, further neurological features were detected on the post-take ward round as listed below: right lower motor neurone seventh nerve weakness; ptosis right greater than left; bilateral wrist drop; bilateral foot drop; generalized reduced tone and reduced power in all four limbs: right arm 3 out of 5, right leg 0 out of 5, left arm 3 to 4 out of 5, and left leg 2 out of 5. No comment was documented regarding sensation.

The chronicity of the neurological features was uncertain at this point as they did not appear to have been previously documented and the immediate reaction was to exclude an acute neurological process. Fortunately, her daughter was present during the ward round that day and a collateral history revealed our patient had ‘possibly’ been like this for 18 months or more. This led to a degree of reassurance with regard to the fact that the neurological findings were unlikely to be acute.

Further discussion with our patient’s son confirmed that her mobility had gradually deteriorated over a two-year period; from his perception, the only novel finding was alteration of our patient’s speech at the time of a presumed ischemic stroke.

Given the account from our patient’s son and daughter, her general practitioner (GP) was also contacted and it was reported that our patient had been referred to various disciplines for poor mobility but had failed to attend her appointments; she had been diagnosed with a Bell’s palsy and third nerve palsy in 2011, which had been attributed to her diabetes. Interestingly, a previous trial of steroids from her GP for presumed arthropathy had resulted in clinical improvement.

Our patient underwent several investigations, included below, as part of the investigative and diagnostic process. In addition, for the complete history, her blood pressure was 104/53 mmHg and heart rate was 57 beats/minute with no documented murmurs.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scan showed atrophy with small vessel disease, high signal at the left corona radiata and adjacent left occipital horn. An MRI cervical spine scan revealed no gross abnormality and a CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis showed extensive diverticular disease only.

Blood investigations

Blood tests showed her Hb level was 85g/dL; WCC was 11.1; platelets were 512, MCV was 89 and her hematinics were normal. Urea and electrolytes test (U&E), liver function test (LFT), and calcium test results were normal. Her albumin level was l0, CRP level was 120 and her baseline HBA1c level was 57mmol/L (normal range 20 to 42mmol/L). Her cholesterol level was unavailable and her blood and urine cultures were negative.

Vasculitic screen

Her antinuclear antibody test (ANA) results were 1/40 and showed a speckled pattern. She had low C3 0.71g/L (0.88 to 1.82g/L) and low C4 0.08g/L (0.16 to 0.45g/L). Her rheumatoid factor was 623, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (cANCA) results were strongly positive and myeloperoxidase / proteinase 3 (MPO/PR3) negative. Her immunoglobulin A (IgA) level was 6.5, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 115, and cryoglobulins were negative. Her carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal, and CA 125 test result was 70 (0 to 35). Serum electrophoresis showed no paraproteins and her neuroimmunological blood test results were negative.

Invasive investigations

Her lumbar puncture test result was negative.

Neurology unit investigations

Electromyography (EMG) showed severe axonal sensory motor neuropathy.

Multi-specialist input from several disciplines including rheumatology and neurology was also requested.

The neurologist documented the following clinical findings: right ptosis; right facial weakness; generalized weakness right greater than left; profound distal greater than proximal weakness and wasting left greater than right; upper limb greater than lower limb; sensation distally decreased in lower limbs; and areflexia.

The general consensus was that our patient was probably manifesting a peripheral neuropathy secondary to a vasculitis (the type of which was difficult to classify); the neuropathy had been possibly exacerbated by a recent stroke; the stroke may have been part of the vasculitic process itself or could have been related to atrial fibrillation.

It was felt that a nerve biopsy would have little else to contribute to the diagnosis and simultaneously might induce patient distress and was therefore avoided.

Given her history of T2DM, our patient was cautiously commenced on a trial of prednisolone 40mg with azathioprine on 13 September 2013; additional oral antidiabetic therapy on advice of the diabetic team was commenced and gradual step-down of steroid therapy was planned.

Within days of steroid initiation, our patient’s inflammatory markers improved. Her CRP level fell to 36 and her WCC to single figures.

Her right wrist drop showed slight improvement from initial investigations to the point of discharge. There was, however, little neurological and functional improvement otherwise.

Our patient remained bedbound and her hospital stay was complicated by a pressure ulcer, which had completely healed prior to discharge to a care home six months later. On discharge her blood test results revealed Hb of 94, WCC of 11.5, her platelets were 380 and MCV 90.8, her CRP level was 20 and albumin level was 28. She remained clinically stable and her treatment goal was to help prevent any further neurological deterioration.

Our patient had been admitted for investigation of iron deficiency anemia and suffered recurrent illness during admission precipitating a prolonged hospital admission and eventual transfer to her local hospital for stroke rehabilitation.

Looking back at the case, our patient did have a stroke as was confirmed on MRI; however, the fact that she had bilateral and long-standing neurological signs evaded detection for a considerable period of time.

It is only after a thorough history-taking, examination and comprehensive geriatric assessment post transfer to the rehabilitation unit that her illness was diagnosed. Though there may not have been a great change to her overall quality of life, an underlying debilitating diagnosis was established with a treatment goal attempting to prevent further neurological deterioration.

It can be argued that had a comprehensive geriatric assessment taken place earlier, keeping in mind that she had displayed neurological symptoms some 18 months previously, would earlier initiation of treatment been more effective in improving her quality of life? Should the fact that she had failed to attend appointments prompted further thinking as to the underlying factor causing nonattendance at clinic appointments, keeping in mind that there was a history of neurological signs?

The case aims to highlight the importance of taking a good history and performing a comprehensive assessment, especially in the older adult [ 1 ].

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s daughter for publication of clinical details and this case report. The patient verbally consented to publication of the case report but was unable to sign the document due to her wrist drop. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

angiotensin-converting enzyme

antinuclear antibody

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

carcinoembryonic antigen

chronic obstructive airways disease

C- reactive protein

computed tomography

CT pulmonary angiogram

electromyography

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

gastrointestinal

general practitioner

immunoglobulin A

liver function test

mean cell volume

myeloperoxidase/proteinase 3

magnetic resonance imaging

Rehabilitation and Assessment Directorate

type 2 diabetes mellitus

urea and electrolytes test

white cell count

Martin F. Comprehensive assessment of the frail older patient. British Geriatrics Society. http://www.bgs.org.uk . Accessed November 2014.

Download references

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to Dr Medhat Zaida, Dr Martin Perry, Dr Tracy Baird, Dr Neil McGowan for providing their valuable input and support in the diagnosis and management of this case. A big thanks to Dr Iain Keith, Dr Christopher Foster and also to Dr Gautamananda Ray for providing their valuable opinion when the manuscript was being drafted and a special thanks to all the other medical, nursing and allied health professionals involved in our patient’s care.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Acute Medicine Registrar, Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, Bankend Road, Dumfries, DG1 4AP, UK

Durga Ghosh

Vale of Leven District General Hospital, Main Street, Alexandria, G83 0UA, UK

Premalatha Karunaratne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Durga Ghosh .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DG was the locum registrar involved with management of the patient, initiating and carrying out investigations during admission, making specialist referrals, liaising with other specialities, acquiring data, drafting and designing the manuscript. PK was the consultant under whom our patient’s care was allocated. PK was also involved in initiating investigations during admission, liaising with other specialities, acquiring data, drafting and designing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Dr Durga Ghosh, ST4 Acute Medicine, Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, Dumfries Dr Premalatha Karunaratne, Consultant Physician Medicine for the Elderly, Vale of Leven District General Hospital, Alexandria and Royal Alexandra Hospital, Paisley.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ghosh, D., Karunaratne, P. The importance of good history taking: a case report. J Med Case Reports 9 , 97 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0559-y

Download citation

Received : 21 January 2015

Accepted : 02 March 2015

Published : 30 April 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-015-0559-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Older adult

- Comprehensive geriatric assessment

- Neurological examination

- Vasculitic neuropathy

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- History of Present Illness

- Review of Systems

Past Medical History

- Physical Examination

- Essential Differential Diagnosis

- Essential Immediate Steps

- Test Result 1

- Test Interpretation

- Relevant Testing

- Test Results 2

- Treatment Orders

- About the Case

Chest Pain in a 62-yr-old Man

- Medical history : Hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Surgical history : Left inguinal hernia repair at age 50.

- Medications : Chlorthalidone 25 mg once/day, lisinopril 10 mg once/day, omeprazole 20 mg prn, sildenafil prn.

- Allergies : No known drug allergies.

- Family history : Father had myocardial infarction (MI) at age 43. Mother has hypertension and type 2 diabetes. No family history of sudden cardiac death.

- Social history : Patient is married and works as an accountant. He does not participate in any formal exercise routine. Patient has smoked cigarettes for 25 yr; currently, he smokes 1 pack/day. He drinks 4 to 5 beers/wk. No illicit drug use.

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2024

Analysis of virtual standardized patients for assessing clinical fundamental skills of medical students: a prospective study

- Xinyu Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-2893-3986 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Duo Zeng 2 na1 ,

- Xiandi Wang 2 ,

- Yaoyu Fu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5890-4745 3 ,

- Ying Han 2 ,

- Manqing He 2 ,

- Xiaoling Chen 2 &

- Dan Pu 1 , 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 981 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

History-taking is an essential clinical competency for qualified doctors. The limitations of the standardized patient (SP) in taking history can be addressed by the virtual standardized patient (VSP). This paper investigates the accuracy of virtual standardized patient simulators and evaluates the applicability of the improved system’s accuracy for diagnostic teaching support and performance assessment.

Data from the application of VSP to medical residents and students were gathered for this prospective study. In a human–machine collaboration mode, students completed exams involving taking SP histories while VSP provided real-time scoring. Every participant had VSP and SP scores. Lastly, using the voice and text records as a guide, the technicians will adjust the system’s intention recognition accuracy and speech recognition accuracy.

The research revealed significant differences in scoring across several iterations of VSP and SP ( p < 0.001). Across various clinical cases, there were differences in application accuracy for different versions of VSP ( p < 0.001). Among training groups, the diarrhea case showed significant differences in speech recognition accuracy ( Z = -2.719, p = 0.007) and intent recognition accuracy ( Z = -2.406, p = 0.016). Scoring and intent recognition accuracy improved significantly after system upgrades.

VSP has a comprehensive and detailed scoring system and demonstrates good scoring accuracy, which can be a valuable tool for history-taking training.

Peer Review reports

History-taking is an essential skill for becoming a competent doctor, and it is a fundamental component of work in various medical fields [ 1 ]. History-taking typically includes general data, chief complaints, present history, past medical history, family history, social history, and review of systems, etc. Since it directs subsequent exams, diagnosis, and treatment choices, gathering patient histories is the first and most important stage in identifying medical conditions [ 2 ]. Therefore, it is vital to provide medical professionals with training in history-taking before they engage in clinical practice [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

Currently, the most common method for teaching history-taking skills combines theoretical instruction with simulation-based education, with Standardized Patients (SP) as the primary method of simulation. SP are individuals who have undergone standardized and systematic training to accurately, realistically, and consistently portray the characteristics, psychosocial features, and emotional responses required for specific medical cases [ 7 , 8 ]. Doctor-patient communication encompasses both verbal and non-verbal components, which are equally important [ 2 , 9 ]. During the diagnostic process, doctors collect information from patients by observing their facial expressions and body language. Similarly, doctors use body language and facial expressions to encourage and ensure patient comfort [ 10 , 11 ]. The United States first used SP for clinical teaching in the 1960s, and China adopted the practice in the 1990s [ 12 ]. SP teaching is a valuable bridge between theoretical instruction and clinical practice. It not only facilitates the simulation of authentic medical scenarios without ethical concerns but also boosts student engagement, enhances clinical communication skills, supports the acquisition of medical knowledge, and promotes a deeper grasp of abstract concepts [ 13 ].

However, the use of SP in medical education has its own challenges. The training process for SP is rigorous, time-consuming, and resource-intensive. Consequently, the availability of qualified SP is limited [ 14 , 15 ]. In the process of SP teaching evaluation, the influence of subjective factors cannot be avoided [ 16 ]. The lengthy and strict training process, resulting in the scarcity of SP, makes it challenging to implement one-on-one history-taking training effectively. To address these limitations of SP, virtual standardized patient (VSP) offers a potential solution. As early as the early twenty-first century, research suggested using computers to aid in history-taking exercises [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ], but VSP has not become widely adopted. Implementing VSP in history-taking instruction can effectively address the limitations found in SP. It reduces the lengthy training time and costs associated with training SP, allows for repetitive training [ 21 , 22 ], and facilitates the assessment of teaching effectiveness [ 23 ], thereby boosting student confidence [ 24 , 25 ]. It reduces the potential subjectivity of both instructors and SP, enabling a more objective and standardized evaluation [ 23 ].

We developed a VSP according to the needs, using speech recognition technology, intention recognition technology, and automatic scoring. VSP initially used sentence similarity matching and then improved to intention recognition. The article aims to explore the accuracy of VSP and assess whether the upgraded system’s accuracy can be applied to diagnostic teaching assistance and performance evaluation. This research highlights certain limitations in SP physician training and examines the application accuracy of our independently developed VSP. The goal is to establish a foundation for more effective teaching strategies.

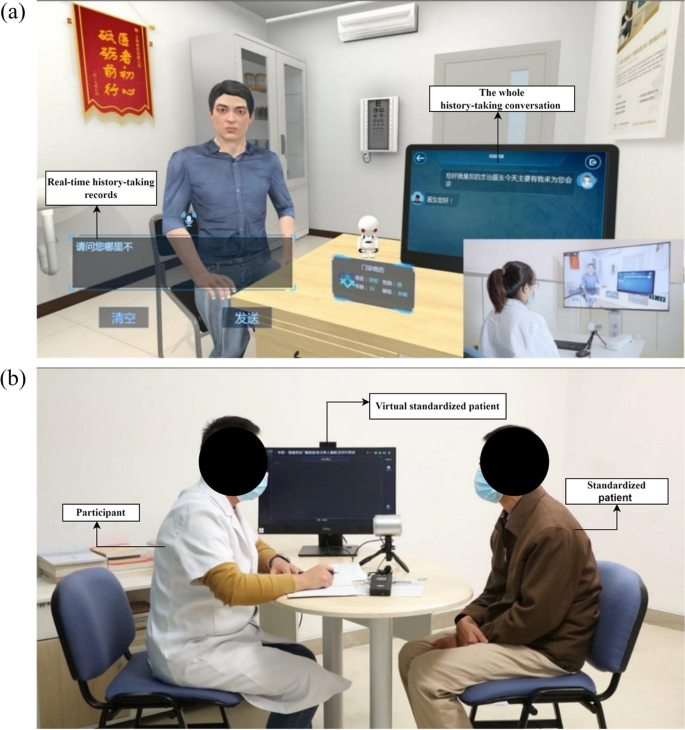

This study utilizes a virtual standardized patient history-taking system jointly developed by our institution and Shanghai Chuxin Medical Technology Co., Ltd., based on speech recognition and intent recognition technology. The system operates in both a human–computer dialogue mode and a human–computer collaborative mode, as detailed in Fig. 1 . This research employs the latter.

Human–computer dialogue mode and human–computer collaborative mode of VSP a human–computer dialogue mode; b human–computer collaborative mode

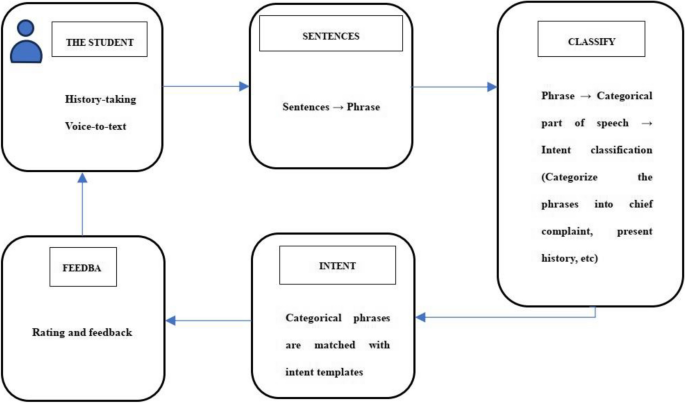

The system first converts the spoken dialogue into text. Subsequently, the sentences are dissected, breaking them down into phrases. Following part-of-speech recognition and classification, these sentences are compared to the intent templates kept in the intent library to provide assessments and comments. After gathering all the data, the system performs self-learning to adjust the corpus [ 26 ]. The specific process is illustrated in Fig. 2 .

The specific process of the virtual standardized patient history-taking system based on speech recognition technology and artificial intelligence

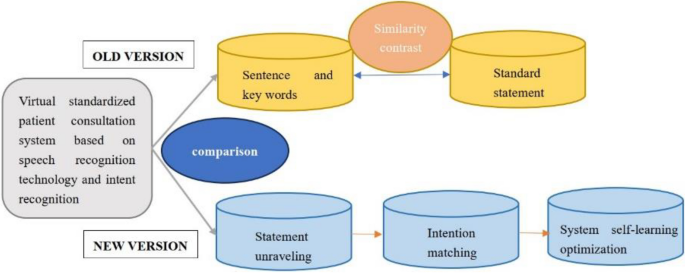

VSP underwent a general system replacement during the experiment, with VSP 1.0 being the old version and VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 being the new version. VSP 1.0 compares sentences and keywords with standard statements, for the old version of the system. It is considered the same statement when the sentences are similar to the standard statements [ 27 ]. For the updated version of the system, VSP 2.0 divides the sentences into phrases, categorizes the phrases, and matches the intent templates of the phrases [ 28 ]. VSP 3.0 is the version of VSP 2.0 self-learning optimization [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. The differences between the old and new versions are shown in Fig. 3 .

Comparison of old and new VSP

Design, setting and subjects

We adopted a prospective study design. The Biomedical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University approved this study (Approval 2019 No.1071). In this study, we applied different versions of VSP to assess the clinical performance of medical students with no prior clinical experience and residents, using a human–computer collaborative model for evaluation. In the study population, clinical medical students were recruited from the annual diagnostics course, while residents were selected from the enhanced training sessions, which covered three years. Participants willing to use VSP are recruited from these two courses, and the scoring results of history-taking can be compared with those of SP. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the tests, and they were informed that the results of this study would not affect their final course grades. All participants had previously received theoretical instruction in medical history taking.

Measurements

In this study, the accuracy of the VSP application was determined. The application accuracy included speech recognition accuracy, intention recognition accuracy, and scoring accuracy. Speech recognition accuracy is the ratio of correctly recognized characters to the total number of characters. Intent recognition accuracy is the ratio of correctly matched phrases to the total number of phrases. The system automatically determines the accuracy of speech recognition and intent recognition, and it separates intent matches with a probability of less than 80%. The results were reviewed manually by two technicians. If their results differed, a third technician made the final decision. The score consisted of the content of history-taking and the skill of history-taking, with a total of 70 scoring points, and the total score of each scoring point was different. The Department of Diagnostics’ multidisciplinary team established the scoring scale, which has been validated and applied for many years. The scale underwent minor modifications based on actual conditions to ensure quality control. Because SP is highly trained and experienced, we calculated the VSP’s scoring accuracy using its scores as the gold standard. Scoring accuracy was calculated as the ratio of the number of scoring points with the same VSP and SP scores to the total score points.

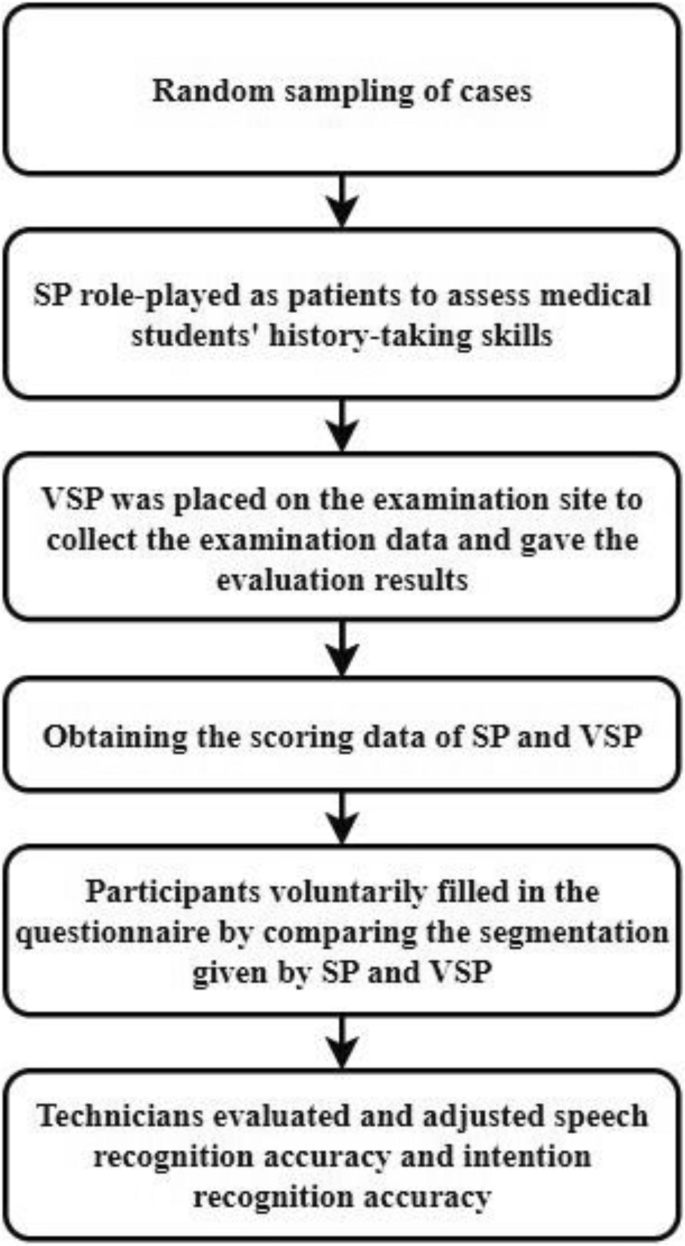

In this study, the participants randomly selected one case from the four cases (diarrhea, syncope, palpitation, cough) during the assessment process. Throughout the assessment, SP acted as a patient and interacted with participants performing the role of doctors. The VSP was placed next to it without responding, collecting information for real-time scoring. As a result, two sets of scores were obtained from SP and VSP. After the examination, participants were invited to complete relevant questionnaires voluntarily (results are shown in the appendices). Following history-taking training with SP, both SP and VSP scores are simultaneously obtained, and participants provide feedback about the VSP after comparing these scores. Speech and intent recognition employ mature commercial technologies, with accuracy automatically generated by the system upon the corpus. Lastly, technicians reviewed the texts and recordings to assess and adjust the accuracy provided by the system. See Fig. 4 for details.

The procedure of the study

Data analysis

Since the data did not meet the normal distribution, we used the Wilcoxon rank sum test when comparing the SP and VSP scores. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the significance of the differences in the accuracy of scoring, speech recognition, and intent recognition of VSP across different VSP versions in various cases. Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA tests were used for pairwise comparisons, with post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction. The independent t -test was used to compare the accuracy of scoring, speech recognition, and intent recognition of VSP 3.0 in different cases between medical students and residents. p < 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

Demographic characteristics

A total of 502 students participated in the study over the three years. Of these, 476 students were included in the final analysis, as 26 students’ data were not recorded due to VSP 1.0 system problems. Among the included participants, 89 medical students used VSP 1.0, 129 used VSP 2.0, and 104 used VSP 3.0. The 154 residents used VSP 3.0. Statistics were based on different versions and randomly selected cases, as shown in Table 1 :

The medical students who used different versions of VSP are at similar stages of learning history-taking, with comparable ages. Residents have more clinical experience than medical students in the same stage of training.

Comparison of history-taking scores given by SP and VSP

The t-test revealed significant differences in the scores given by SP and VSP for both medical students ( Z = -8.194, p < 0.05; Z = -9.864, p < 0.05; Z = -8.867, p < 0.05) and residents ( Z = -10.773, p < 0.05). Generally, VSP scores were lower than SP scores. The score distribution was skewed, mainly in the high-score range, as shown in Table 2. .

Comparison of VSP application accuracy

Our study examined four distinct medical scenarios, comparing the application accuracy of various VSP versions and determining whether there are variations in accuracy while using VSP 3.0 with medical students and residents.

Comparison of VSP application accuracy in diarrhea cases

The results indicated significant differences in the application accuracy ( H = 42.424, p < 0.001; H = 27.220, p < 0.001; H = 44.135, p < 0.001) among the three versions of the VSP system. Multiple mean comparisons revealed significant differences in scoring accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). The speech recognition accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001), and VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001) was significantly different. Intent recognition accuracy was significantly different between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). The results are presented in Table 3 .

When instructing medical students and residents in history-taking using VSP 3.0, a t-test was employed to determine whether there were any significant differences in application accuracy between the two groups. The results showed significant differences in speech recognition accuracy ( Z = -2.719, p = 0.007) and intent recognition accuracy ( Z = -2.406, p = 0.016). The results are presented in Table 4 .

Comparison of VSP application accuracy in syncope cases

There were significant differences in the application accuracy ( H = 34.506, p < 0.001; H = 27.233, p < 0.001; H = 38.485, p < 0.001). Multiple mean comparison results showed significant differences in scoring accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), as well as between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). Significant differences were observed in speech recognition accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.016), and between VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.019). Intent recognition accuracy exhibited significant differences between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001), and between VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.036). The results are presented in Table 5 .

There were no significant differences in application accuracy ( Z = -0.426, p = 0.670; Z = -0.216, p = 0.829; Z = -0.035, p = 0.972) between medical students and residents using VSP 3.0 in syncope cases. The results are presented in Table 6 .

Comparison of VSP application accuracy in palpitation cases

There were significant differences in the application accuracy ( H = 71.858, p < 0.001; H = 23.986, p < 0.001; H = 77.121, p < 0.001). Multiple mean comparison results showed significant differences in scoring accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), as well as between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). Significant differences were observed in speech recognition accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p = 0.011), VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001), and between VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.035). Intent recognition accuracy exhibited significant differences between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001), and between VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.033). The results are presented in Table 7 .

The results showed no significant differences in application accuracy ( t = 1.055, p = 0.132; t = 0.138, p = 0.068; t = -0.872, p = 0.557) when using VSP 3.0 for teaching medical students and residents in palpitation cases. The results are presented in Table 8 .

Comparison of VSP application accuracy in cough cases

There were significant differences in the application accuracy ( H = 40.521, p < 0.001; H = 18.961, p < 0.001; F = 235.851, p < 0.001). Multiple mean comparison results indicated significant differences in scoring accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), as well as between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). Significant differences were observed in speech recognition accuracy between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), as well as between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p = 0.011). Intent recognition accuracy exhibited significant differences between VSP 1.0 and VSP 2.0 ( p < 0.001), between VSP 1.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001), and between VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 ( p < 0.001). The results are presented in Table 9 .

There were no significant differences in application accuracy ( t = 0.276, p = 0.241; t = -4.933, p = 0.186; t = -0.486, p = 0.309) when using VSP 3.0 for teaching medical students and residents in cough cases. The results are presented in Table 10 .

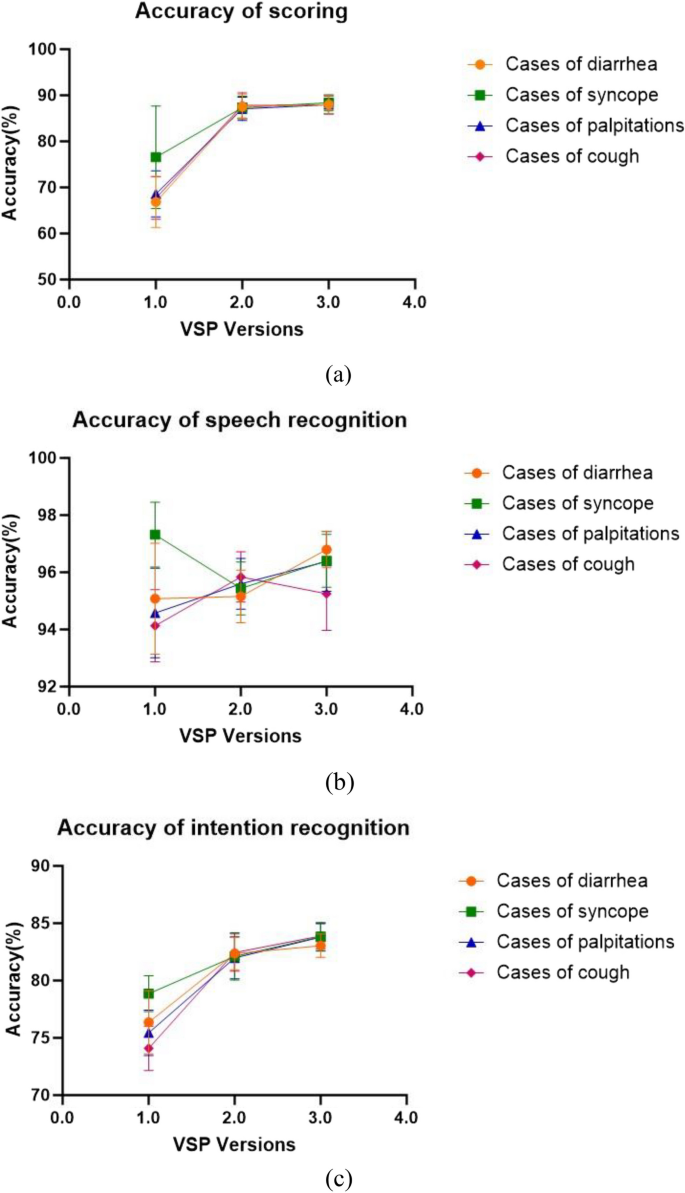

Changes in the accuracy of different cases

We conducted an analysis and comparison of scoring accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy (Fig. 5 ). Results showed that both scoring accuracy and intent recognition accuracy increased with the upgrade of the VSP version, and the standard deviation decreased. However, the trend in speech recognition accuracy varied depending on the cases. In the VSP 1.0 version, the syncope cases showed the best accuracy in speech recognition and intent recognition, followed by diarrhea, palpitations, and coughing. In the VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0 versions, scoring and intent recognition accuracy were nearly identical for all four cases.

The accuracy trend chart and the maximum accuracy was 100%. a is the accuracy of scoring; b is the accuracy of speech recognition; c is the accuracy of intention recognition

We explore the accuracy of our self-developed VSP simulator for assessing history-taking skills. While intent recognition and score accuracy have increased after updates and optimizations, speech recognition accuracy has continuously maintained a high level. The VSP application accuracy has stabilized after optimization and updating, continuously reaching high levels in various scenarios. The application accuracy of VSP does not vary depending on the population.

It is clear from the statistics in Table 2. that VSP scores are generally lower than SP scores. This finding aligns with the results of a study by Fink and others [ 33 ]. Fink et al. attributed this to the lower subjects’ interest, reduced appraisal of motivational value, and decreased quantity of evidence generation reported for VPs. However, our VSP did not engage in human–computer dialogue, so we believe the reason is different. Based on the analysis of this study, the reasons may be attributed to the overall operational processes and assessment methods of the VSP system. The accuracy of the system’s voice recognition and intention recognition might have affected the scoring accuracy since VSP will first translate the speech into text, then perform intention recognition, and finally provide the score. The lower score of VSP compared to SP may result from the recognition and classification error of speech and intention. Therefore, our study further explored the scoring accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy of VSP.

Considering the potential confounding effects of different case content, we conducted separate analyses of scoring accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy for each of the four cases: diarrhea, syncope, palpitations, and cough. All versions of VSP used these same four cases. We analyzed the scoring accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy of different VSP versions in these cases. The results all showed significant differences.

We also looked at any discrepancies in accuracy between medical students and residents using VSP 3.0. Among the results of comparing different groups, significant differences were observed only in the case of diarrhea, where speech recognition accuracy and intent recognition accuracy showed differences. The reason may be that medical students and residents conducted history-taking in different ways. Medical students, lacking clinical experience, tend to follow a standardized model provided by professors, making their approach easily recognizable by the system. In contrast, residents have some clinical experience, which leads to various inquiry styles that pose certain identification challenges. Furthermore, there are regional and dialectal accent variances in Chinese, which contributes to some degree of mistakes in the voice recognition system.

Based on the scoring accuracy data, the latest version of VSP achieved an accuracy rate of 85.40–89.62%, which aligns with similar research findings. In a study by William and colleagues [ 34 ] response accuracy ranged from 84 to 88%, and in Maicher et al.’s study [ 35 ], response accuracy ranged from 79 to 86%. The construction of this system has been relatively successful. However, future work should focus on enriching the synonym database and improving accuracy. The results of pairwise comparisons indicate a significant improvement in scoring accuracy with the newer system versions, i.e. VSP 2.0 and VSP 3.0. However, when compared with VSP 2.0, VSP 3.0 showed no improvement in scoring accuracy, indicating that the system’s self-learning functionality has a limited impact on enhancing scoring accuracy. The reason might be insufficient data in the collected corpus and insufficient time for the machine’s self-learning. It remains uncertain whether the self-learning feature of VSP has any impact on scoring accuracy. Further research is needed to confirm whether the self-learning functionality of VSP affects scoring accuracy.

In the four medical cases, speech recognition accuracy is relatively high. After pairwise comparisons, no specific patterns causing significant differences in speech recognition accuracy were observed in the data. There are possible reasons for this phenomenon. Firstly, regional and ethnic differences may contribute to distinct accents, especially when the system is designed for standard Mandarin. Secondly, speaking at a fast pace could cause the system to have difficulty accurately capturing the spoken words. Lastly, the system may fail to recognize or accurately identify sentence breaks, which could also be a contributing factor. When speech-to-text conversion fails to accurately convey the intended meaning, the system responds with errors or fails to respond. This aligns with the findings of Kammoun et al. [ 36 ], whose system automatically moves to the next section if it cannot accurately recognize the speech. In the future, adjustments can be made to the system to optimize the speech recognition section by customizing response time intervals for each individual.

Overall, intent recognition accuracy has been consistently improving. This suggests that VSP 2.0 successfully addressed the issue of intent recognition accuracy compared to VSP 1.0, and its self-learning feature provides an advantage in enhancing intent recognition accuracy. Based on the research results, it can be inferred that VSP’s intent recognition accuracy does not vary with different experience groups. Future research should include a more diverse range of participants to validate these findings.

The findings (Fig. 5 ) indicate that scoring accuracy and intent recognition accuracy improve with the upgrade of the VSP version. However, speech recognition accuracy varies across different cases. This discrepancy can be attributed to factors mentioned earlier, such as the subject’s accent, speaking speed, and sentence breakage, posing challenges for VSP recognition. In VSP 1.0, there was a notable standard deviation in application accuracy, with diarrhea cases showing the highest accuracy. This variation may be linked to VSP 1.0’s slight instability and differing word recognition accuracy across cases. The scoring process involves speech recognition followed by intent recognition, leading to relatively consistent results in scoring accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy in VSP 1.0.

This study only utilized the system’s examination mode, focusing solely on speech conversion and score feedback. The system we employed has an additional human–computer interaction mode that can be used for student history-taking training, which we did not explore in this study. Moreover, the system’s comprehension of voice text and response accuracy were not examined in this study. These aspects can be studied in future research. Furthermore, we only examined a few key metrics, including VSP score accuracy, speech recognition accuracy, and intent recognition accuracy, without discussing all the metrics. Additionally, this study only included medical students and residents. Extra variables for various demographics should be considerate for analysis to investigate the correctness of the application of VSP in various population groupings.

VSP proves to be a feasible way to train history-taking skills. This study describes the scoring process of our self-developed VSP and reveals its commendable application accuracy. The upgrading and the self-learning function of the system have played a role in improving the stability and accuracy of VSP. At this point, the accuracy of VSP 3.0 has reached the level required for the history-taking training auxiliary tool, opening up possibilities for integrating diagnostic training tools into clinical education, and effectively addressing the shortage of opportunities for students in SP training. In the future, continuous optimization of VSP will position it as a reliable training and assessment tool, fostering students’ independent learning abilities in classroom teaching.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Tawanwongsri W, Phenwan T. Reflective and feedback performances on Thai medical students’ patient history-taking skills. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):141.

Article Google Scholar

Vogel D, Meyer M, Harendza S. Verbal and non-verbal communication skills including empathy during history taking of undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):157.

Alharbi L, Almoallim H. History-Taking Skills in Rheumatology. In: Almoallim H, Cheikh M, editors. Skills in Rheumatology. Singapore: Springer; 2021. p. 3–16.

Chapter Google Scholar

Kantar A, Marchant JM, Song WJ, Shields MD, Chatziparasidis G, Zacharasiewicz A, Moeller A, Chang AB. History taking as a diagnostic tool in children with chronic cough. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:850912.

Steinkellner C, Schlömmer C, Dünser M. Medical history taking and clinical examination in emergency and intensive care medicine. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020;115(7):530–8.

Altshuler L, Wilhite JA, Hardowar K, Crowe R, Hanley K, Kalet A, Zabar S, Gillespie C, Ark T. Understanding medical student paths to communication skills expertise using latent profile analysis. Med Teach. 2023;45(10):1140–7.

Barrows HS. An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. AAMC. Acad Med. 1993;68(6):443–51. Discussion 451–443.

Gillette C, Stanton RB, Rockich-Winston N, Rudolph M, Anderson HG Jr. Cost-effectiveness of using standardized patients to assess student-pharmacist communication skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(10):73–9.

Bagacean C, Cousin I, Ubertini A-H, El Yacoubi El Idrissi M, Bordron A, Mercadie L, Garcia LC, Ianotto J-C, De Vries P, Berthou C. Simulated patient and role play methodologies for communication skills and empathy training of undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):491.

Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H, Kinoshita M, Fujimori S, Shimizu T, Yano E. Evaluating medical students’ non-verbal communication during the objective structured clinical examination. Med Educ. 2006;40(12):1180–7.

Mehrabian A, Ferris SR. INFERENCE OF ATTITUDES FROM NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION IN 2 CHANNELS. J Consult Psychol. 1967;31(3):248–52.

Stillman PL, Sawyer WD. A new program to enhance the teaching and assessment of clinical skills in the People’s Republic of China. Acad Med. 1992;67(8):495–9.

Liu T, Luo J, He H, Zheng J, Zhao J, Li K. History-taking instruction for baccalaureate nursing students by virtual patient training: A retrospective study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;71:97–104.

Aranda JH, Monks SM. Roles and Responsibilities of the Standardized Patient Director in Medical Simulation. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2023.

Google Scholar

Zhang S, Soreide KK, Kelling SE, Bostwick JR. Quality assurance processes for standardized patient programs. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(4):523–8.

Du J, Zhu X, Wang J, Zheng J, Zhang X, Wang Z, Li K. History-taking level and its influencing factors among nursing undergraduates based on the virtual standardized patient testing results: cross sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;111:105312.

Edelstein RA, Reid HM, Usatine R, Wilkes MS. A comparative study of measures to evaluate medical students’ performance. Acad Med. 2000;75(8):825–33.

Guagnano MT, Merlitti D, Manigrasso MR, Pace-Palitti V, Sensi S. New medical licensing examination using computer-based case simulations and standardized patients. Acad Med. 2002;77(1):87–90.

Hawkins R, MacKrell Gaglione M, LaDuca T, Leung C, Sample L, Gliva-McConvey G, Liston W, De Champlain A, Ciccone A. Assessment of patient management skills and clinical skills of practising doctors using computer-based case simulations and standardised patients. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):958–68.

Maicher KR, Stiff A, Scholl M, White M, Fosler-Lussier E, Schuler W, Serai P, Sunder V, Forrestal H, Mendella L, et al. Artificial intelligence in virtual standardized patients: combining natural language understanding and rule based dialogue management to improve conversational fidelity. Med Teach. 2023;45(3):279–85.

Hauze SW, Hoyt HH, Frazee JP, Greiner PA, Marshall JM. Enhancing nursing education through affordable and realistic holographic mixed reality: the virtual standardized patient for clinical simulation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1120:1–13.

Kelly S, Smyth E, Murphy P, Pawlikowska T. A scoping review: virtual patients for communication skills in medical undergraduates. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):429.

Maicher KR, Zimmerman L, Wilcox B, Liston B, Cronau H, Macerollo A, Jin L, Jaffe E, White M, Fosler-Lussier E, et al. Using virtual standardized patients to accurately assess information gathering skills in medical students. Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1053–9.

Borja-Hart NL, Spivey CA, George CM. Use of virtual patient software to assess student confidence and ability in communication skills and virtual patient impression: A mixed-methods approach. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11(7):710–8.

Quail M, Brundage SB, Spitalnick J, Allen PJ, Beilby J. Student self-reported communication skills, knowledge and confidence across standardised patient, virtual and traditional clinical learning environments. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:73.

Campillos-Llanos L, Thomas C, Bilinski É, Neuraz A, Rosset S, Zweigenbaum P. Lessons Learned from the Usability Evaluation of a Simulated Patient Dialogue System. J Med Syst. 2021;45(7):69.

Sun Y, Shuohuan W, Yukun L, Shikun F, Xuyi C, Han Z, et al. ERNIE: enhanced representation through knowledge integration [Internet]. arXiv [Preprint]. 2019. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.09223 .

Huang L, Hu J, Cai Q, Fu G, Bai Z, Liu Y, et al. The performance evaluation of artificial intelligence ERNIE bot in Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination. Postgrad Med J. 2024:qgae062.

Han H. The application of the mask detection based on automatic machine learning. Proceedings of SPIE; 2022, 12287. p. 124–9.

Wang T, Wu Y. Design and practice of teaching demonstration system for water quality prediction experiment based on EasyDL. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering; 2023. p. 1369–74.

Zhao Y, Wang P. The Prediction and Investigation of Factors in the Adaptability Level of Online Learning Based on AutoML and K-Means Algorithm. In 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Control, Electronics and Computer Technology (ICCECT); 2024. p. 1313–9.

Zhou Z. Automatic machine learning-based data analysis for video game industry. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Computer Science, Electronic Information Engineering and Intelligent Control Technology (CEI); 2022. p. 732–7.

Fink MC, Reitmeier V, Stadler M, Siebeck M, Fischer F, Fischer MR. Assessment of diagnostic competences with standardized patients versus virtual patients: experimental study in the context of history taking. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e21196.

Bond WF, Lynch TJ, Mischler MJ, Fish JL, McGarvey JS, Taylor JT, Kumar DM, Mou KM, Ebert-Allen RA, Mahale DN, et al. Virtual standardized patient simulation: case development and pilot application to high-value care. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(4):241–50.

Maicher K, Danforth D, Price A, Zimmerman L, Wilcox B, Liston B, Cronau H, Belknap L, Ledford C, Way D, et al. Developing a conversational virtual standardized patient to enable students to practice history-taking skills. Simul Healthc. 2017;12(2):124–31.

Kammoun A, Slama R, Tabia H, Ouni T, Abid M. Generative adversarial networks for face generation: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;55:1–37.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants and colleagues involved in this study.

This study was supported by a Research project of the New Century Higher Education Teaching Reform Project (the ninth phase) of Sichuan University (SCU9334), the Medical Simulation Education Research Project of the National Center for Medical Education Development (2021MNYB04), and the Experimental Technology Research Program of Sichuan University (SCU2023005).

Author information

Xinyu Zhang and Duo Zeng contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

The Chinese Cochrane Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 610041, People’s Republic of China

Xinyu Zhang & Dan Pu

West China Medical Simulation Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 610041, People’s Republic of China

Xinyu Zhang, Duo Zeng, Xiandi Wang, Ying Han, Manqing He, Xiaoling Chen & Dan Pu

West China Biomedical Big Data Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 610041, People’s Republic of China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

XZ, DZ, and DP conceptualized the study. MH, YH, XC, and XW implemented the experiment. DZ and XZ collected and analyzed the data. XZ, DZ, and XW wrote the original draft. YF revised and polished the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dan Pu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.