- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

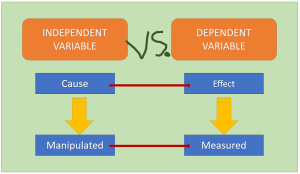

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

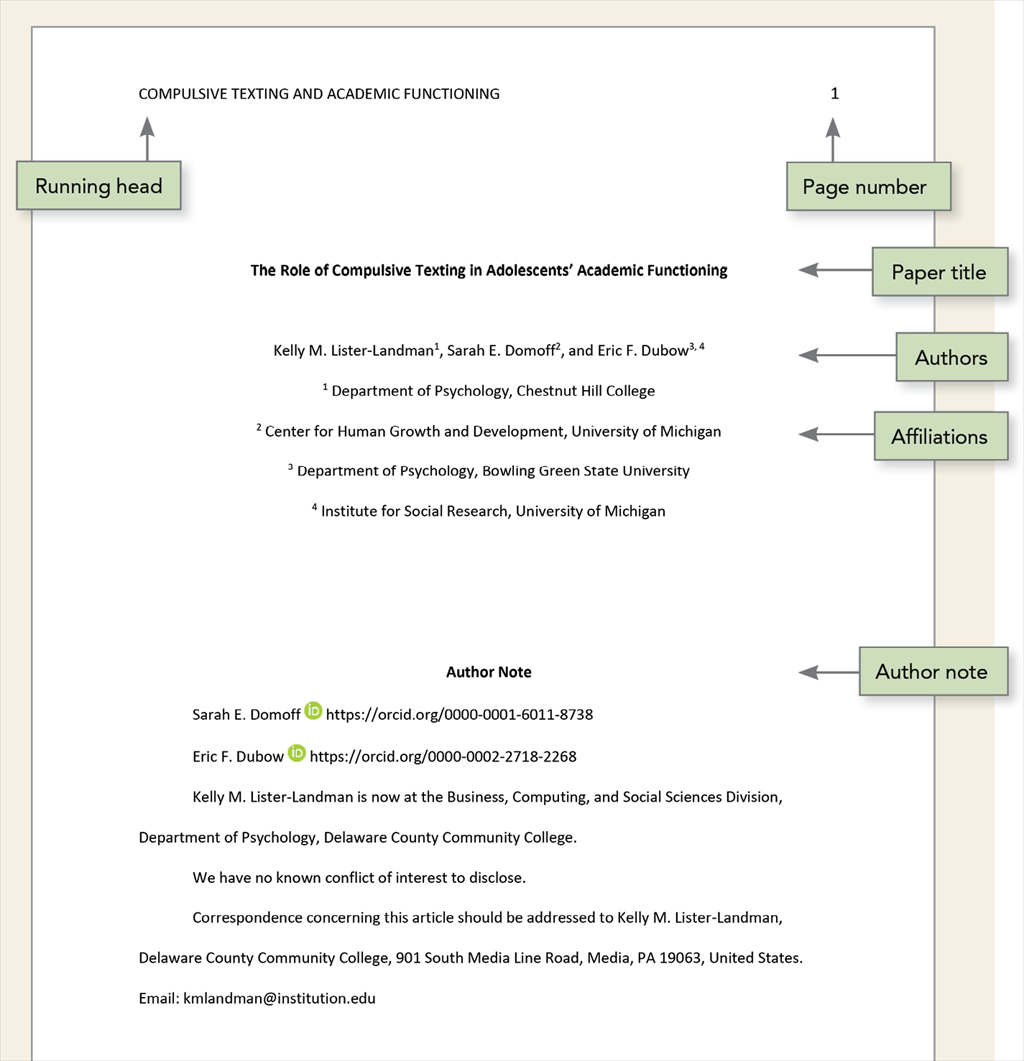

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

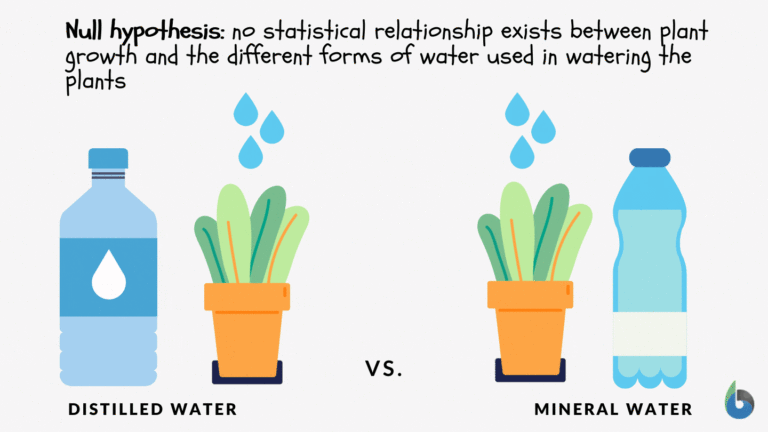

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

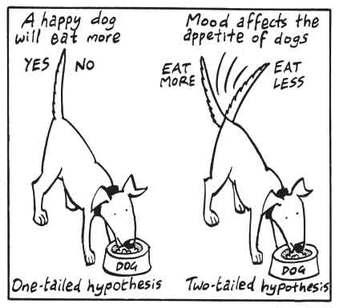

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

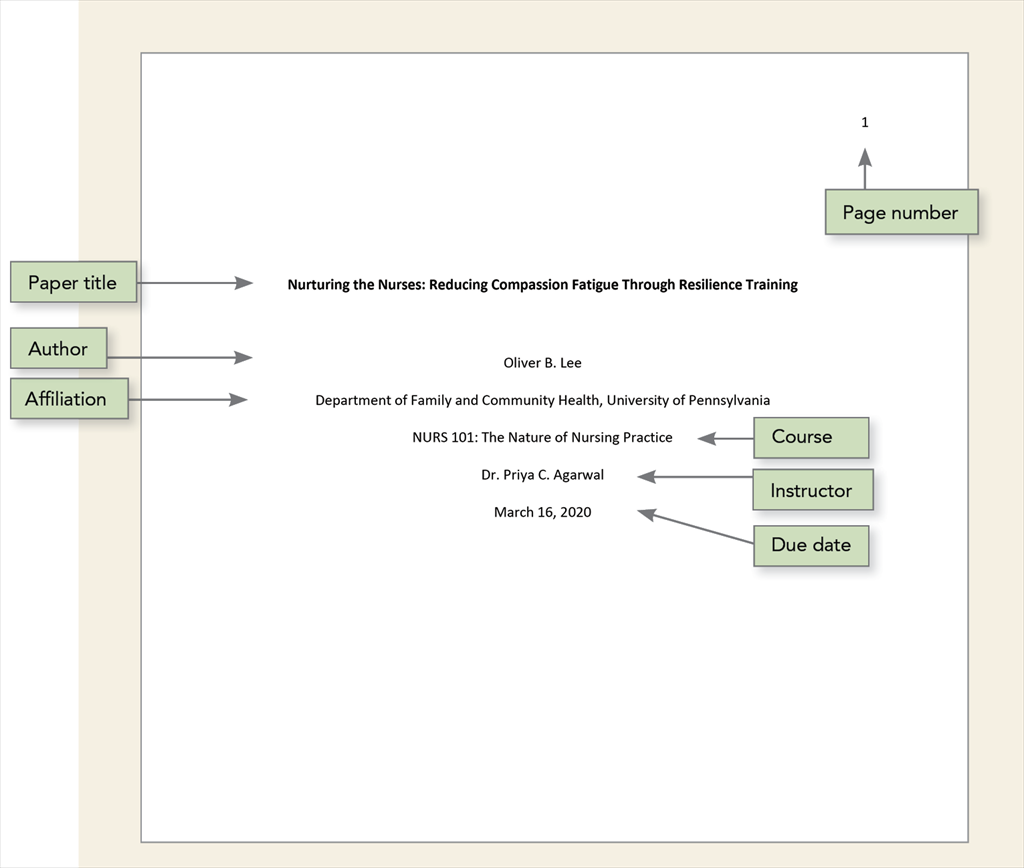

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Hi” best wishes to you and your very nice blog”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Step 1. ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is high school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout high school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | High school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

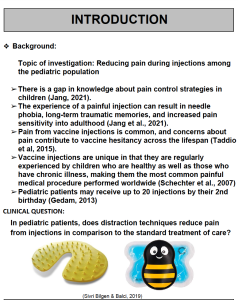

The First Step: Ask; Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

In this module, we will learn about identifying the problem, start the “Ask” process with developing an answerable clinical question, and learn about purpose statements and hypotheses.

Content includes:

- Identifying the problem

- Determining the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO)

- Asking a Research/Clinical Question (Based on PICO)

Statements of Purpose

Objectives:

- Describe the process of developing a research/practice problem.

- Describe the components of a PICO.

- Identify different types of PICOs.

- Distinguish function and form of statements of purpose.

- Describe the function and characteristics of hypotheses.

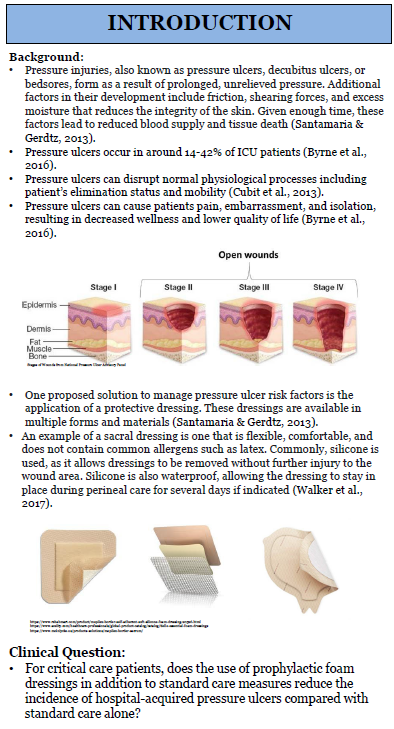

Development of a Research/Practice Problem

Practice questions frequently arise from day-to-day problems that are encountered by providers (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). Often, these problems are very obvious. However, sometimes we need to back up and take a close look at the status quo to see underlying issues. The basis for any research project is indeed the underlying problem or issue. A good problem statement or paragraph is a declaration of what it is that is problematic or what it is that we do not know much about (a gap in knowledge) (Polit & Beck, 2018).

The process of defining the practice/clinical problem begins by seeking answers to clinical concerns. This is the first step in the EBP process: To ask . We start by asking some broad questions to help guide the process of developing our practice problem.

- Is there evidence that the current treatment works?

- Does the current practice help the patient?

- Why are we doing the current practice?

- Should we be doing the current practice this way?

- Is there a way to do this current practice more efficiently?

- Is there a more cost-effective method to do this practice?

Problem Statements:

For our EBP Project, we will need to ask these broad questions and then develop our problem that exists. This establishes the “background” of the issue we want to know more about.

For example, if we are choosing a clinical question based on wanting to know if adjunct music therapy helps decrease postoperative pain levels than just pharmaceuticals alone, we might consider the underlying problems of:

- Postoperative pain is not adequately managed in greater than 80% of patients in the US, although rates vary depending on such factors as type of surgery performed, analgesic/anesthetic intervention used, and time elapsed after surgery (Gan, 2017).

- Poorly controlled acute postoperative pain is associated with increased morbidity, functional and quality-of-life impairment, delayed recovery time, prolonged duration of opioid use, and higher health-care costs (Gan, 2017).

- Multimodal analgesic techniques are widely used but new evidence is disappointing (Rawal, 2016).

In the above examples, we are establishing that poorly managed postoperative pain is a problem. Thus, looking at evidence about adjunctive music therapy may help to address how we might manage pain more effectively. These are our problem statements. This would be our introduction section on the EBP poster. For the sake of our EBP poster, you do not need to list these on the poster references. A heads up: The sources used to help develop our research/clinical program should not be the same resources that we use to answer our upcoming clinical question. In essence, we will be conducting two literature reviews: One, to establish the underlying problem; and, two: To find published research that helps to answer our developed clinical question.

Here is the introduction to the article titled, “The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure” (Haedtke et al, 2017). You can read that the underlying problem is multifocal: 67% of patient with heart failure (HF) experience pain, depression is a comorbidity that affects 22% to 42% of HF patients, and that little attention has been paid to this relationship in patients with HF. The researchers have established the need for further research and why further research is needed.

Here is another example of how the clinical problem is addressed in an EBP poster that wants to appraise existing evidence related to dressing choice for decubitus ulcers.

When trying to communicate clinical problems, there are two main sources (Titler et al, 1994, 2001):

- Problem-focused triggers : These are identified by staff during routine monitoring of quality, risk, adverse events, financial, or benchmarking data.

- Knowledge-focused triggers : There are identified through reading published evidence or learning new information at conferences or other professional meetings.

Sources of Evidence-Based Clinical Problems:

| Triggers | Sources of Evidence |

| Problem-focused |

|

| Knowledge-focused |

Most problem statements have the following components:

- Problem identification: What is wrong with the current situation or action?

- Background: What is the nature of the problem or the context of the situation? (this helps to establish the why)

- Scope of the problem: How many people are affected? Is this a small problem? Big problem? Potential to grow quickly to a large problem? Has been increasing/decreasing recently?

- Consequences of the problem: If we do nothing or leave as the status quo, what is the cost of not fixing the issue?

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

- Proposed solution: How will the information or evidence contribute to the solution of the problem?

If you are stumped on a topic, ask faculty, RNs at local facilities, colleagues, and key stakeholders at local facilities for some ideas! There is usually “something” that the nursing field is concerned about or has questions about.

Components of a PICO Question

After we have asked ourselves some background questions, we need to develop a foreground (focused) question. A thoughtful development of a well-structured foreground clinical/practice question is important because the question drives the strategies that you will use to search for the published evidence. The question needs to be very specific, non-ambiguous , and measurable in order to find the relevant evidence needed and also increased the likelihood that you will find what you are looking for.

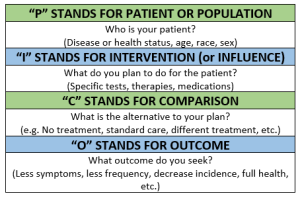

In developing your clinical/practice question, there is a helpful format to utilize to establish the key component. This format includes the Patient/Population, Intervention/Influence/Exposure, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) (Richardson, Wilson, Nishikawa, & Hayward, 1995).

Let’s dive into each component to better understand.

P atient, population, or problem: We want to describe the patient, the population, or the problem. Get specific. We will want to know exactly who we are wanting to know about. Consider age, gender, setting of the patient (e.g. postoperative), and/or symptoms.

I ntervention: The intervention is the action or, in other words, the treatment, process of care, education given, or assessment approaches. We will come back to this in more depth, but for now remember that the intervention is also called the “Independent Variable”.

C omparison: Here we are comparing with other interventions. A comparison can be standard of care that already exists, current practice, an opposite intervention/action, or a different intervention/action.

O utcome: What is that that we are looking at for a result or consequence of the intervention? The outcome needs to have a metric for actually measuring results. The outcome can include quality of life, patient satisfaction, cost impacts, or treatment results. The outcome is also called the “Dependent Variable”.

The PICO question is a critical aspect of the EBP project to guide the problem identification and create components that can be used to shape the literature search.

Let’s watch a nice YouTube video, “PICO: A Model for Evidence-Based Research”:

“PICO: A Model for Evidence Based Research” by Binghamton University Libraries. Licensed CCY BY .

Great! Okay, let’s move on and discuss the various types of PICOs.

Types of PICOs

Before we start developing our clinical question, let’s go over the various types of PICOs and the clinical question that can result from the components. There are various types of PICOs but we are concerned with the therapy/treatment/intervention format of PICO for our EBP posters.

Let’s take a look at the various types of PICOs:

| Type of Question | PICO Template |

| Therapy/Intervention/Treatment (We will use this type for our EBP Posters) | In _________ (Population), what is the effect of ___________ (Intervention) in comparison to ___________(Comparison) on __________ (Outcome)? Or Does _________ (Intervention) compared to __________ (Comparison) decrease/increase ______________ (Outcome) in ____________ (Population)?

|

| Diagnosis/Assessment | For _________ (Population), does __________ (Identifying tool/procedure) yield more accurate or more appropriate diagnostic/assessment information than __________ (Comparative tool/procedure) about __________ (Outcome)?

|

| Prognosis | For ______ (Population), does _______ (Exposure to disease or condition), relative to _______ (Comparative disease or condition) increase the risk of ________ (Outcome)?

|

| Etiology/Harm | Does (Influence, exposure, or characteristic) increase the risk of ________ (Outcome) compared to ________ (Comparative influence, exposure, or condition) in ________ (Population)?

|

| Description (Prevalence/Incidence) | These questions vary from the typical PICO in that explicit comparisons are not typical (except to compare population). In ______ (Population), how prevalent is ________ (Outcome)?

|

| Meaning or Process | Explicit comparisons are not typical in these types of questions. These are qualitative questions and are used to elicit narrative, subjective responses. What is it like for ________ (Population) to experience _________ (situation, condition, circumstance)?

|

The first step in developing a research or clinical practice question is developing your PICO. Well, we’ve done that above. You will select each component of your PICO and then turn that into your question. Making the EBP question as specific as possible really helps to identify specific terms and narrow the search, which will result in reducing the time it times searching for relevant evidence.

Once you have your pertinent clinical question, you will use the components to begin your search in published literature for articles that help to answer your question. In class, we will practice with various situations to develop PICOs and clinical questions.

Many articles have the researcher’s statement of purpose (sometimes referred to as “aim”, “goal”, or “objective”) for their research project. This helps to identify what the overarching direction of inquiry may be. You do not need a statement of purpose/aim/goal/objective for your EBP poster. However, knowing what a statement of purpose is will help you when appraising articles to help answer your clinical question.

The following statement of purpose was written as an aim. The population (P) was identified as patients with HF, the interventions (I) included physical activity/exercise, and the outcomes (O) included pain, depression, total activity time, and sitting time as correlated with the interventions.

In the articles above, the authors made it easy and included their statements of purpose within the abstract at the beginning of the article. Most articles do not feature this ease, and you will need to read the introduction or methodology section of the article to find the statement of purpose, much like within article 3.1.

In qualitative studies, the statement of purpose usually indicates the nature of the inquiry, the key concept, the key phenomenon, and the population.

Function and Characteristics of Hypotheses.

A hypothesis (plural: hypothes es ) is a statement of predicted outcome. Meaning, it is an educated and formulated guess as to how the intervention (independent variable – more on that soon!) impacts the outcome (dependent variable). It is not always a cause and effect. Sometimes there can be just a simple association or correlation. We will come back to that in a few modules.

In your PICO statement, you can think of the “I” as the independent variable and the “O” as the dependent variable . Variables will begin making more sense as we go. But for now, remember this:

Independent Variable (IV): This is a measure that can be manipulated by the researcher. Perhaps it is a medication, an educational program, or a survey. The independent variable enacts change (or not) onto the independent variable.

Dependent Variable (DV): This is the result of the independent variable. This is the variable that we utilize statistical analyses to measure. For instance, if we are intervening with a blood pressure medication (our IV), then our DV would be the measurement of the actual blood pressure.

Most of the time, a hypothesis results from a well-worded research question. Here is an example:

Research Question : “Does sexual abuse in childhood affect the development of irritable bowel syndrome in women?”

Research Hypothesis : Women (P) who were sexually abused in childhood (I) have a higher incidence of irritable bowel syndrome (O) than women who were not abused (C).

You may note in that hypothesis that there is a predicted direction of outcome. One thing leads to something.

But, why do we need a hypothesis? First, they help to promote critical thinking. Second, it gives the researcher a way to measure a relationship. Suppose we conducted a study guided only by a research question. Take the above question, for example. Without a hypothesis, the researcher is seemingly prepared to accept any result (Polit & Beck, 2021). The problem with that is that it is almost always possible to explain something superficially after the fact, even if the findings are inconclusive. A hypothesis reduces the possibility that spurious results will be misconstrued (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Not all research articles will list a hypothesis. This makes it more difficult to critically appraise the results. That is not to say that the results would be invalidated, but it should ignite a spirit of further inquiry as to if the results are valid.

Hypotheses (also called alternative hypothesis) can be stated as:

- Directional or nondirectional

- Simple or complex

- Research or Null

Simple hypothesis : Statement of causal (cause and effect) relationship – one independent variable (intervention) and one dependent variable (outcome).

Example : If you stay up late, then you feel tired the next day.

Complex hypothesis : Statement of causal (cause and effect) or associative (not causal) between two or more independent variables (interventions) and/or two or more dependent variables (outcomes).

Example : Higher the poverty, higher the illiteracy in society, higher will be the rate of crime (three variables – two independent variables and one dependent variable).

Directional hypothesis : Specifies not only the existence but also the expected direction of the relationship between the dependent (outcome) and the independent (intervention) variables. You will also see this called “One-tailed hypothesis”.

Example : Depression scores will decrease following a 6-week intervention.

Nondirectional hypothesis : Does not specify the direction of relationship between the variables. You will also see this called “Two-tailed hypothesis”.

Example : College students will perform differently from elementary school students on a memory task (without predicting which group of students will perform better).

Null hypothesis : The null hypothesis assumes that any kind of difference between the chosen characteristics that you see in a set of data is due to chance. Now, the null hypothesis is why the plain old hypothesis is also called alternative hypothesis. We don’t just assume that the hypothesis is true. So, it is considered an alternative to something just happening by chance (null).

Example : Let’s say our research question is, “Do teens use cell phones to access the internet more than adults?” – our null hypothesis could state: Age has no effect on how cell phones are used for internet access.

And then, further develop the problem and background through finding existing literature to help answer the following questions:

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

With the previous example of pain in the pediatric population, here is an example of an Introduction section from a past student poster:

- What was the research problem? Was the problem statement easy to locate and was it clearly stated? Did the problem statement build a coherent and persuasive argument for the new study?

- Does the problem have significance for nursing?

- Was there a good fit between the research problem and the paradigm (and tradition) within which the research was conducted?

- Did the report formally present a statement of purpose, research question, and/or hypotheses? Was this information communicated clearly and concisely, and was it placed in a logical and useful location?

- Were purpose statements or research questions worded appropriately (e.g., were key concepts/variables identified and the population specified?

- If there were no formal hypotheses, was their absence justified? Were statistical tests used in analyzing the data despite the absence of stated hypotheses?

- Were hypotheses (if any) properly worded—did they state a predicted relationship between two or more variables? Were they presented as research or as null hypotheses?

References & Attribution

“ Green check mark ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

“ Light bulb doodle ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

“ Magnifying glass ” by rawpixel licensed CC0

“ Orange flame ” by rawpixel licensed CC0 .

Chen, P., Nunez-Smith, M., Bernheim, S… (2010). Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25 (9), 947-53.

Dearholt, S.L., & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines (2nd Ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Gan, T. (2017). Poorly controlled postoperative pain: Prevalence, consequences, and prevention. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 2287-2298.

Genc, A., Can, G., Aydiner, A. (2012). The efficiency of the acupressure in prevention of the chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer, 21 , 253-261.

Haedtke, C., Smith, M., VanBuren, J., Kein, D., Turvey, C. (2017). The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 32 (5), E21-E25.

Pankong, O., Pothiban, L., Sucamvang, K., Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim Internal Journal of Nursing Res, 22 (2), 131-143.

Polit, D. & Beck, C. (2021). Lippincott CoursePoint Enhanced for Polit’s Essentials of Nursing Research (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Rawal, N. (2016). Current issues in postoperative pain management. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 33 , 160-171.

Richardson, W.W., Wilson, M.C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R.S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. American College of Physicians, 123 (3), A12-A13.

Titler, M. G., Kleiber, C., Steelman, V.J. Rakel, B. A. Budreau, G., Everett,…Goode, C.J. (2001). The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13 (4), 497-509.

Evidence-Based Practice & Research Methodologies Copyright © by Tracy Fawns is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The P value: What it really means

As nurses, we must administer nursing care based on the best available scientific evidence. But for many nurses, critical appraisal, the process used to determine the best available evidence, can seem intimidating. To make critical appraisal more approachable, let’s examine the P value and make sure we know what it is and what it isn’t.

Defining P value

The P value is the probability that the results of a study are caused by chance alone. To better understand this definition, consider the role of chance.

The concept of chance is illustrated with every flip of a coin. The true probability of obtaining heads in any single flip is 0.5, meaning that heads would come up in half of the flips and tails would come up in half of the flips. But if you were to flip a coin 10 times, you likely would not obtain heads five times and tails five times. You’d be more likely to see a seven-to-three split or a six-to-four split. Chance is responsible for this variation in results.

Just as chance plays a role in determining the flip of a coin, it plays a role in the sampling of a population for a scientific study. When subjects are selected, chance may produce an unequal distribution of a characteristic that can affect the outcome of the study. Statistical inquiry and the P value are designed to help us determine just how large a role chance plays in study results. We begin a study with the assumption that there will be no difference between the experimental and control groups. This assumption is called the null hypothesis. When the results of the study indicate that there is a difference, the P value helps us determine the likelihood that the difference is attributed to chance.

Competing hypotheses

In every study, researchers put forth two kinds of hypotheses: the research or alternative hypothesis and the null hypothesis. The research hypothesis reflects what the researchers hope to show—that there is a difference between the experimental group and the control group. The null hypothesis directly competes with the research hypothesis. It states that there is no difference between the experimental group and the control group.

It may seem logical that researchers would test the research hypothesis—that is, that they would test what they hope to prove. But the probability theory requires that they test the null hypothesis instead. To support the research hypothesis, the data must contradict the null hypothesis. By demonstrating a difference between the two groups, the data contradict the null hypothesis.

Testing the null hypothesis

Now that you know why we test the null hypothesis, let’s look at how we test the null hypothesis.

After formulating the null and research hypotheses, researchers decide on a test statistic they can use to determine whether to accept or reject the null hypothesis. They also propose a fixed-level P value. The fixed level P value is often set at .05 and serves as the value against which the test-generated P value must be compared. (See Why .05?)

A comparison of the two P values determines whether the null hypothesis is rejected or accepted. If the P value associated with the test statistic is less than the fixed-level P value, the null hypothesis is rejected because there’s a statistically significant difference between the two groups. If the P value associated with the test statistic is greater than the fixed-level P value, the null hypothesis is accepted because there’s no statistically significant difference between the groups.

The decision to use .05 as the threshold in testing the null hypothesis is completely arbitrary. The researchers credited with establishing this threshold warned against strictly adhering to it.

Remember that warning when appraising a study in which the test statistic is greater than .05. The savvy reader will consider other important measurements, including effect size, confidence intervals, and power analyses when deciding whether to accept or reject scientific findings that could influence nursing practice.

Real-world hypothesis testing

How does this play out in real life? Let’s assume that you and a nurse colleague are conducting a study to find out if patients who receive backrubs fall asleep faster than patients who do not receive backrubs.

1. State your null and research hypotheses

Your null hypothesis will be that there will be no difference in the average amount of time it takes patients in each group to fall asleep. Your research hypothesis will be that patients who receive backrubs fall asleep, on average, faster than those who do not receive backrubs. You will be testing the null hypothesis in hopes of supporting your research hypothesis.

2. Propose a fixed-level P value

Although you can choose any value as your fixed-level P value, you and your research colleague decide you’ll stay with the conventional .05. If you were testing a new medical product or a new drug, you would choose a much smaller P value (perhaps as small as .0001). That’s because you would want to be as sure as possible that any difference you see between groups is attributed to the new product or drug and not to chance. A fixed-level P value of .0001 would mean that the difference between the groups was attributed to chance only 1 time out of 10,000. For a study on backrubs, however, .05 seems appropriate.

3. Conduct hypothesis testing to calculate a probability value

You and your research colleague agree that a randomized controlled study will help you best achieve your research goals, and you design the process accordingly. After consenting to participate in the study, patients are randomized to one of two groups:

- the experimental group that receives the intervention—the backrub group

- the control group—the non-backrub group.

After several nights of measuring the number of minutes it takes each participant to fall asleep, you and your research colleague find that on average, the backrub group takes 19 minutes to fall asleep and the non-backrub group takes 24 minutes to fall asleep.

Now the question is: Would you have the same results if you conducted the study using two different groups of people? That is, what role did chance play in helping the backrub group fall asleep 5 minutes faster than the non-backrub group? To answer this, you and your colleague will use an independent samples t-test to calculate a probability value.

An independent samples t-test is a kind of hypothesis test that compares the mean values of two groups (backrub and non-backrub) on a given variable (time to fall asleep).

Hypothesis testing is really nothing more than testing the null hypothesis. In this case, the null hypothesis is that the amount of time needed to fall asleep is the same for the experimental group and the control group. The hypothesis test addresses this question: If there’s really no difference between the groups, what is the probability of observing a difference of 5 minutes or more, say 10 minutes or 15 minutes?

We can define the P value as the probability that the observed time difference resulted from chance. Some find it easier to understand the P value when they think of it in relationship to error. In this case, the P value is defined as the probability of committing a Type 1 error. (Type 1 error occurs when a true null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected.)

4. Compare and interpret the P value

Early on in your study, you and your colleague selected a fixed-level P value of .05, meaning that you were willing to accept that 5% of the time, your results might be caused by chance. Also, you used an independent samples t-test to arrive at a probability value that will help you determine the role chance played in obtaining your results. Let’s assume, for the sake of this example, that the probability value generated by the independent samples t-test is .01 (P = .01). Because this P value associated with the test statistic is less than the fixed-level statistic (.01 < .05), you can reject the null hypothesis. By doing so, you declare that there is a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups. (See Putting the P value in context.)

In effect, you’re saying that the chance of observing a difference of 5 minutes or more, when in fact there is no difference, is less than 5 in 100. If the P value associated with the test statistic would have been greater than .05, then you would accept the null hypothesis, which would mean that there is no statistically significant difference between the control and experimental groups. Accepting the null hypothesis would mean that a difference of 5 minutes or more between the two groups would occur more than 5 times in 100.

Putting the P value in context

Although the P value helps you interpret study results, keep in mind that many factors can influence the P value—and your decision to accept or reject the null hypothesis. These factors include the following:

- Insufficient power. The study may not have been designed appropriately to detect an effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Therefore, a change may have occurred without your knowing it, causing you to incorrectly reject your hypothesis.

- Unreliable measures. Instruments that don’t meet consistency or reliability standards may have been used to measure a particular phenomenon.

- Threats to internal validity. Various biases, such as selection of patients, regression, history, and testing bias, may unduly influence study outcomes.

A decision to accept or reject study findings should focus not only on P value but also on other metrics including the following:

- Confidence intervals (an estimated range of values with a high probability of including the true population value of a given parameter)

- Effect size (a value that measures the magnitude of a treatment effect)

Remember, P value tells you only whether a difference exists between groups. It doesn’t tell you the magnitude of the difference.

5. Communicate your findings

The final step in hypothesis testing is communicating your findings. When sharing research findings (hypotheses) in writing or discussion, understand that they are statements of relationships or differences in populations. Your findings are not proved or disproved. Scientific findings are always subject to change. But each study leads to better understanding and, ideally, better outcomes for patients.

Key concepts

The P value isn’t the only concept you need to understand to analyze research findings. But it is a very important one. And chances are that understanding the P value will make it easier to understand other key analytical concepts.

Selected references

Burns N, Grove S: The Practice of Nursing Research: Conduct, Critique, and Utilization. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004.

Glaser DN: The controversy of significance testing: misconceptions and alternatives. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8(5):291-296.

Kenneth J. Rempher, PhD, RN, MBA, CCRN, APRN,BC, is Director, Professional Nursing Practice at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore (Md.). Kathleen Urquico, BSN, RN, is a Direct Care Nurse in the Rubin Institute of Advanced Orthopedics at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Interpreting statistical significance in nursing research

Introduction to qualitative nursing research

Navigating statistics for successful project implementation

Nurse research and the institutional review board

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Research 101: Forest plots

Understanding confidence intervals helps you make better clinical decisions

Differentiating statistical significance and clinical significance

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

Are you confident about confidence intervals?

Making sense of statistical power

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Hypothesis Testing

Yarandi , Hossein

HOSSEIN N. YARANDI teaches biostatistics and health economics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. He received his BS in economics and statistics from Tehran University and his MA in economics and PhD in econometrics from Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. He has taught statistics, macro and microeconomics, finite math, calculus, operations research, statistical methods in research, mathematical statistics with computer applications, multivariate statistics, design and analysis of experiment, and health economics at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, State University of New York at Fredonia, and the University of Florida .

HYPOTHESIS TESTING IS the process of making a choice between two conflicting hypotheses. The null hypothesis, H 0 , is a statistical proposition stating that there is no significant difference between a hypothesized value of a population parameter and its value estimated from a sample drawn from that population. The alternative hypothesis, H 1 or H a , is a statistical proposition stating that there is a significant difference between a hypothesized value of a population parameter and its estimated value. When the null hypothesis is tested, a decision is either correct or incorrect. An incorrect decision can be made in two ways: We can reject the null hypothesis when it is true (Type I error) or we can fail to reject the null hypothesis when it is false (Type II error). The probability of making Type I and Type II errors is designated by α and β, respectively. The smallest observed significance level for which the null hypothesis would be rejected is referred to as the p -value. The p -value only has meaning as a measure of confidence when the decision is to reject the null hypothesis. It has no meaning when the decision is that the null hypothesis is true.

Full Text Access for Subscribers:

Individual subscribers.

Institutional Users

Not a subscriber.

You can read the full text of this article if you:

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Trends in hypothesis testing and related variables in nursing research: a retrospective exploratory study

Affiliation.

- 1 Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 21560925

- DOI: 10.7748/nr2011.04.18.3.38.c8462

Aim: To compare the inclusion and the influences of selected variables on hypothesis testing during the 1980s and 1990s.

Background: In spite of the emphasis on conducting inquiry consistent with the tenets of logical positivism, there have been no studies investigating the frequency and patterns of hypothesis testing in nursing research

Data sources: The sample was obtained from the journal Nursing Research which was the research journal with the highest circulation during the study period under study. All quantitative studies published during the two decades including briefs and historical studies were included in the analyses

Review methods: A retrospective design was used to select the sample. Five years from the 1980s and 1990s each were randomly selected from the journal, Nursing Research. Of the 582 studies, 517 met inclusion criteria.

Discussion: Findings suggest that there has been a decline in the use of hypothesis testing in the last decades of the 20th century. Further research is needed to identify the factors that influence the conduction of research with hypothesis testing.

Conclusion: Hypothesis testing in nursing research showed a steady decline from the 1980s to 1990s. Research purposes of explanation, and prediction/ control increased the likelihood of hypothesis testing.

Implications for practice: Hypothesis testing strengthens the quality of the quantitative studies, increases the generality of findings and provides dependable knowledge. This is particularly true for quantitative studies that aim to explore, explain and predict/control phenomena and/or test theories. The findings also have implications for doctoral programmes, research preparation of nurse-investigators, and theory testing.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- A descriptive study of research published in scientific nursing journals from 1985 to 2010. Yarcheski A, Mahon NE, Yarcheski TJ. Yarcheski A, et al. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012 Sep;49(9):1112-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.03.004. Epub 2012 Apr 6. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012. PMID: 22483613

- Nursing research in Italy. Zanotti R. Zanotti R. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1999;17:295-322. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1999. PMID: 10418662 Review.

- The research evidence published in high impact nursing journals between 2000 and 2006: a quantitative content analysis. Mantzoukas S. Mantzoukas S. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Apr;46(4):479-89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.016. Epub 2009 Feb 1. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009. PMID: 19187934

- Incorporating multiculturalism into oncology nursing research: the last decade. Phillips J, Weekes D. Phillips J, et al. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002 Jun;29(5):807-16. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.807-816. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002. PMID: 12058155 Review.

- [Analysis of research papers published in the Journal of the Korean Academy of Nursing-focused on research trends, intervention studies, and level of evidence in the research]. Shin HS, Hyun MS, Ku MO, Cho MO, Kim SY, Jeong JS, Jeong GH, Seomoon GA, Son YJ. Shin HS, et al. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010 Feb;40(1):139-49. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2010.40.1.139. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010. PMID: 20220290 Korean.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Nursing Research

- First Online: 24 January 2019

Cite this chapter

- Lars-Petter Jelsness-Jørgensen 3 , 4

1675 Accesses

Nurses play an increasingly active role in clinical research in IBD. By reviewing existing literature on the topic, this chapter provides a brief overview of some main concepts related to research in nursing. In addition, the chapter provides some general advice in relation to implementing evidence-based practice, as well as carrying out independent research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Ethics and Integrity in Nursing Research

Case Study in Nursing

Abrandt Dahlgren M, Higgs J, Richardson B (2004) Developing practice knowledge for health professionals. Butterworth-Heinemann, Edinburgh

Google Scholar

Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, Lindgren S, Moum B, Hjortswang H et al (2011) The prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency in IBD outpatients in Scandinavia. Scand J Gastroenterol 46(3):304–309

Article Google Scholar

Bager P, Befrits R, Wikman O, Lindgren S, Moum B, Hjortswang H et al (2012) Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease is common and multifactorial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 35(1):133–141

Article CAS Google Scholar

Coenen S, Weyts E, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Noman M, Ballet V et al (2017) Effects of introduction of an inflammatory bowel disease nurse position on the quality of delivered care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29(6):646–650

Czuber-Dochan W, Ream E, Norton C (2013a) Review article: description and management of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 37(5):505–516

Czuber-Dochan W, Dibley LB, Terry H, Ream E, Norton C (2013b) The experience of fatigue in people with inflammatory bowel disease: an exploratory study. J Adv Nurs 69(9):1987–1999

Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bassett P, Berliner S, Bredin F, Darvell M et al (2014a) Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis 8(11):1398–1406

Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H (2014b) Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohns Colitis 8(8):835–844

Dibley L, Norton C (2013) Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19(7):1450–1462

Dibley L, Bager P, Czuber-Dochan W, Farrell D, Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Kemp K et al (2017) Identification of research priorities for inflammatory bowel disease nursing in Europe: a Nurses-European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Delphi Survey. J Crohns Colitis 11(3):353–359

PubMed Google Scholar

Dicenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB (2009) Accessing pre-appraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Evid Based Nurs 12(4):99–101

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N et al (2014) Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 14:89

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Thompson R (2016) Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Jaghult S, Larson J, Wredling R, Kapraali M (2007) A multiprofessional education programme for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 42(12):1452–1459

Jaghult S, Saboonchi F, Johansson UB, Wredling R, Kapraali M (2011) Identifying predictors of low health-related quality of life among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparison between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis with disease duration. J Clin Nurs 20(11–12):1578–1587

Jelsness-Jorgensen LP (2015) Does a 3-week critical research appraisal course affect how students perceive their appraisal skills and the relevance of research for clinical practice? A repeated cross-sectional survey. Nurse Educ Today 35(1):e1–e5

Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T (2011a) Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011:492034

Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA (2011b) Chronic fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33(1):106–114

Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA (2011c) Chronic fatigue is more prevalent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in healthy controls. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17(7):1564–1572

Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum B (2012a) Chronic fatigue is associated with increased disease-related worries and concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 18(5):445–452