Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What Are Research Objectives and How to Write Them (with Examples)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Research is at the center of everything researchers do, and setting clear, well-defined research objectives plays a pivotal role in guiding scholars toward their desired outcomes. Research papers are essential instruments for researchers to effectively communicate their work. Among the many sections that constitute a research paper, the introduction plays a key role in providing a background and setting the context. 1 Research objectives, which define the aims of the study, are usually stated in the introduction. Every study has a research question that the authors are trying to answer, and the objective is an active statement about how the study will answer this research question. These objectives help guide the development and design of the study and steer the research in the appropriate direction; if this is not clearly defined, a project can fail!

Research studies have a research question, research hypothesis, and one or more research objectives. A research question is what a study aims to answer, and a research hypothesis is a predictive statement about the relationship between two or more variables, which the study sets out to prove or disprove. Objectives are specific, measurable goals that the study aims to achieve. The difference between these three is illustrated by the following example:

- Research question : How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

- Research hypothesis : Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

- Research objective : To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

This article discusses the importance of clear, well-thought out objectives and suggests methods to write them clearly.

What is the introduction in research papers?

Research objectives are usually included in the introduction section. This section is the first that the readers will read so it is essential that it conveys the subject matter appropriately and is well written to create a good first impression. A good introduction sets the tone of the paper and clearly outlines the contents so that the readers get a quick snapshot of what to expect.

A good introduction should aim to: 2,3

- Indicate the main subject area, its importance, and cite previous literature on the subject

- Define the gap(s) in existing research, ask a research question, and state the objectives

- Announce the present research and outline its novelty and significance

- Avoid repeating the Abstract, providing unnecessary information, and claiming novelty without accurate supporting information.

Why are research objectives important?

Objectives can help you stay focused and steer your research in the required direction. They help define and limit the scope of your research, which is important to efficiently manage your resources and time. The objectives help to create and maintain the overall structure, and specify two main things—the variables and the methods of quantifying the variables.

A good research objective:

- defines the scope of the study

- gives direction to the research

- helps maintain focus and avoid diversions from the topic

- minimizes wastage of resources like time, money, and energy

Types of research objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives . 4 General objectives state what the research expects to achieve overall while specific objectives break this down into smaller, logically connected parts, each of which addresses various parts of the research problem. General objectives are the main goals of the study and are usually fewer in number while specific objectives are more in number because they address several aspects of the research problem.

Example (general objective): To investigate the factors influencing the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

Example (specific objective): To assess the influence of firm size on the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

In addition to this broad classification, research objectives can be grouped into several categories depending on the research problem, as given in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of research objectives

| Exploratory | Explores a previously unstudied topic, issue, or phenomenon; aims to generate ideas or hypotheses |

| Descriptive | Describes the characteristics and features of a particular population or group |

| Explanatory | Explains the relationships between variables; seeks to identify cause-and-effect relationships |

| Predictive | Predicts future outcomes or events based on existing data samples or trends |

| Diagnostic | Identifies factors contributing to a particular problem |

| Comparative | Compares two or more groups or phenomena to identify similarities and differences |

| Historical | Examines past events and trends to understand their significance and impact |

| Methodological | Develops and improves research methods and techniques |

| Theoretical | Tests and refines existing theories or helps develop new theoretical perspectives |

Characteristics of research objectives

Research objectives must start with the word “To” because this helps readers identify the objective in the absence of headings and appropriate sectioning in research papers. 5,6

- A good objective is SMART (mostly applicable to specific objectives):

- Specific—clear about the what, why, when, and how

- Measurable—identifies the main variables of the study and quantifies the targets

- Achievable—attainable using the available time and resources

- Realistic—accurately addresses the scope of the problem

- Time-bound—identifies the time in which each step will be completed

- Research objectives clarify the purpose of research.

- They help understand the relationship and dissimilarities between variables.

- They provide a direction that helps the research to reach a definite conclusion.

How to write research objectives?

Research objectives can be written using the following steps: 7

- State your main research question clearly and concisely.

- Describe the ultimate goal of your study, which is similar to the research question but states the intended outcomes more definitively.

- Divide this main goal into subcategories to develop your objectives.

- Limit the number of objectives (1-2 general; 3-4 specific)

- Assess each objective using the SMART

- Start each objective with an action verb like assess, compare, determine, evaluate, etc., which makes the research appear more actionable.

- Use specific language without making the sentence data heavy.

- The most common section to add the objectives is the introduction and after the problem statement.

- Add the objectives to the abstract (if there is one).

- State the general objective first, followed by the specific objectives.

Formulating research objectives

Formulating research objectives has the following five steps, which could help researchers develop a clear objective: 8

- Identify the research problem.

- Review past studies on subjects similar to your problem statement, that is, studies that use similar methods, variables, etc.

- Identify the research gaps the current study should cover based on your literature review. These gaps could be theoretical, methodological, or conceptual.

- Define the research question(s) based on the gaps identified.

- Revise/relate the research problem based on the defined research question and the gaps identified. This is to confirm that there is an actual need for a study on the subject based on the gaps in literature.

- Identify and write the general and specific objectives.

- Incorporate the objectives into the study.

Advantages of research objectives

Adding clear research objectives has the following advantages: 4,8

- Maintains the focus and direction of the research

- Optimizes allocation of resources with minimal wastage

- Acts as a foundation for defining appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Provides measurable outcomes that can help evaluate the success of the research

- Determines the feasibility of the research by helping to assess the availability of required resources

- Ensures relevance of the study to the subject and its contribution to existing literature

Disadvantages of research objectives

Research objectives also have few disadvantages, as listed below: 8

- Absence of clearly defined objectives can lead to ambiguity in the research process

- Unintentional bias could affect the validity and accuracy of the research findings

Key takeaways

- Research objectives are concise statements that describe what the research is aiming to achieve.

- They define the scope and direction of the research and maintain focus.

- The objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

- Clear research objectives help avoid collection of data or resources not required for the study.

- Well-formulated specific objectives help develop the overall research methodology, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization.

- Research objectives should cover all aspects of the problem statement in a coherent way.

- They should be clearly stated using action verbs.

Frequently asked questions on research objectives

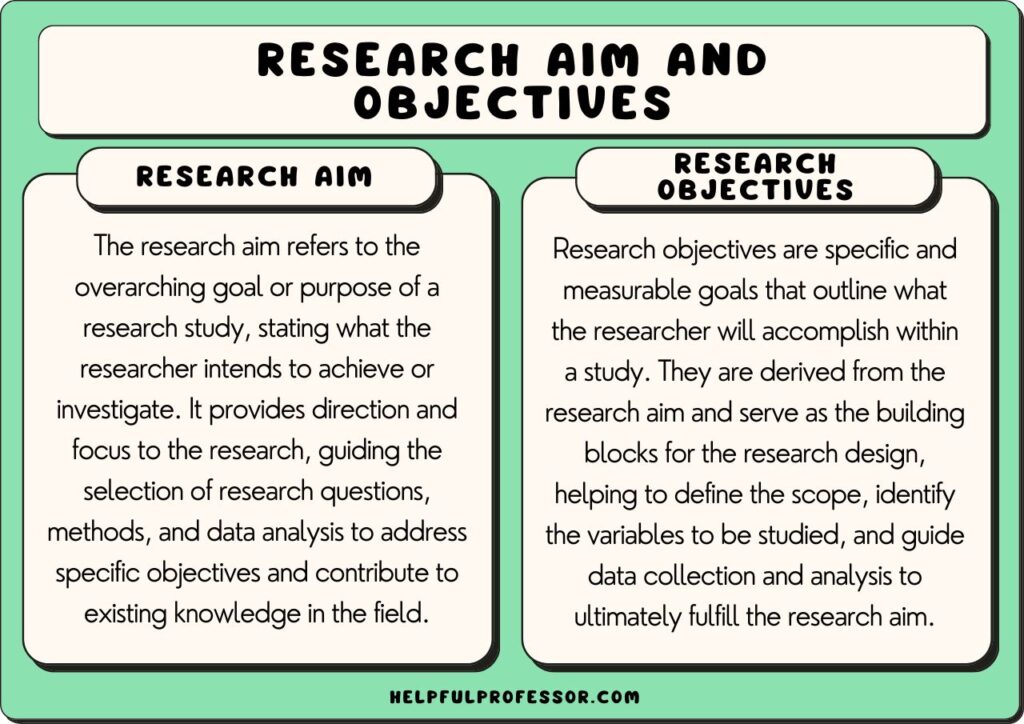

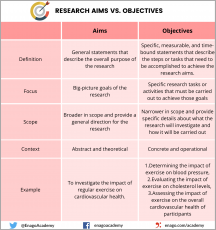

Q: what’s the difference between research objectives and aims 9.

A: Research aims are statements that reflect the broad goal(s) of the study and outline the general direction of the research. They are not specific but clearly define the focus of the study.

Example: This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.

Research objectives focus on the action to be taken to achieve the aims. They make the aims more practical and should be specific and actionable.

Example: To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation.

Q: What are the examples of research objectives, both general and specific?

A: Here are a few examples of research objectives:

- To identify the antiviral chemical constituents in Mumbukura gitoniensis (general)

- To carry out solvent extraction of dried flowers of Mumbukura gitoniensis and isolate the constituents. (specific)

- To determine the antiviral activity of each of the isolated compounds. (specific)

- To examine the extent, range, and method of coral reef rehabilitation projects in five shallow reef areas adjacent to popular tourist destinations in the Philippines.

- To investigate species richness of mammal communities in five protected areas over the past 20 years.

- To evaluate the potential application of AI techniques for estimating best-corrected visual acuity from fundus photographs with and without ancillary information.

- To investigate whether sport influences psychological parameters in the personality of asthmatic children.

Q: How do I develop research objectives?

A: Developing research objectives begins with defining the problem statement clearly, as illustrated by Figure 1. Objectives specify how the research question will be answered and they determine what is to be measured to test the hypothesis.

Q: Are research objectives measurable?

A: The word “measurable” implies that something is quantifiable. In terms of research objectives, this means that the source and method of collecting data are identified and that all these aspects are feasible for the research. Some metrics can be created to measure your progress toward achieving your objectives.

Q: Can research objectives change during the study?

A: Revising research objectives during the study is acceptable in situations when the selected methodology is not progressing toward achieving the objective, or if there are challenges pertaining to resources, etc. One thing to keep in mind is the time and resources you would have to complete your research after revising the objectives. Thus, as long as your problem statement and hypotheses are unchanged, minor revisions to the research objectives are acceptable.

Q: What is the difference between research questions and research objectives? 10

| Broad statement; guide the overall direction of the research | Specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve |

| Identify the main problem | Define the specific outcomes the study aims to achieve |

| Used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge | Used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research |

| Not mutually exclusive with research objectives | Should be directly related to the research question |

| Example: | Example: |

Q: Are research objectives the same as hypotheses?

A: No, hypotheses are predictive theories that are expressed in general terms. Research objectives, which are more specific, are developed from hypotheses and aim to test them. A hypothesis can be tested using several methods and each method will have different objectives because the methodology to be used could be different. A hypothesis is developed based on observation and reasoning; it is a calculated prediction about why a particular phenomenon is occurring. To test this prediction, different research objectives are formulated. Here’s a simple example of both a research hypothesis and research objective.

Research hypothesis : Employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

Research objective : To assess whether employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

To summarize, research objectives are an important part of research studies and should be written clearly to effectively communicate your research. We hope this article has given you a brief insight into the importance of using clearly defined research objectives and how to formulate them.

- Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010 Aug;53(4):278-81.

- Abbadia J. How to write an introduction for a research paper. Mind the Graph website. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/how-to-write-an-introduction-for-a-research-paper/

- Writing a scientific paper: Introduction. UCI libraries website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

- Research objectives—Types, examples and writing guide. Researchmethod.net website. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/research-objectives/#:~:text=They%20provide%20a%20clear%20direction,track%20and%20achieve%20their%20goals .

- Bartle P. SMART Characteristics of good objectives. Community empowerment collective website. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-smar.htm

- Research objectives. Studyprobe website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.studyprobe.in/2022/08/research-objectives.html

- Corredor F. How to write objectives in a research paper. wikiHow website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-Objectives-in-a-Research-Proposal

- Research objectives: Definition, types, characteristics, advantages. AccountingNest website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.accountingnest.com/articles/research/research-objectives

- Phair D., Shaeffer A. Research aims, objectives & questions. GradCoach website. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/

- Understanding the difference between research questions and objectives. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://board.researchersjob.com/blog/research-questions-and-objectives

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What are Experimental Groups in Research

What is IMRaD Format in Research?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Graduate School Applications: Writing a Research Statement

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a Research Statement?

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential candidate’s application for post-undergraduate study. This may include applications for graduate programs, post-doctoral fellowships, or faculty positions. The research statement is often the primary way that a committee determines if a candidate’s interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

What Should It Look Like?

Research statements are generally one to two single-spaced pages. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application.

Your research statement should situate your work within the larger context of your field and show how your works contributes to, complicates, or counters other work being done. It should be written for an audience of other professionals in your field.

What Should It Include?

Your statement should start by articulating the broader field that you are working within and the larger question or questions that you are interested in answering. It should then move to articulate your specific interest.

The body of your statement should include a brief history of your past research . What questions did you initially set out to answer in your research project? What did you find? How did it contribute to your field? (i.e. did it lead to academic publications, conferences, or collaborations?). How did your past research propel you forward?

It should also address your present research . What questions are you actively trying to solve? What have you found so far? How are you connecting your research to the larger academic conversation? (i.e. do you have any publications under review, upcoming conferences, or other professional engagements?) What are the larger implications of your work?

Finally, it should describe the future trajectory on which you intend to take your research. What further questions do you want to solve? How do you intend to find answers to these questions? How can the institution to which you are applying help you in that process? What are the broader implications of your potential results?

Note: Make sure that the research project that you propose can be completed at the institution to which you are applying.

Other Considerations:

- What is the primary question that you have tried to address over the course of your academic career? Why is this question important to the field? How has each stage of your work related to that question?

- Include a few specific examples that show your success. What tangible solutions have you found to the question that you were trying to answer? How have your solutions impacted the larger field? Examples can include references to published findings, conference presentations, or other professional involvement.

- Be confident about your skills and abilities. The research statement is your opportunity to sell yourself to an institution. Show that you are self-motivated and passionate about your project.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Objectives

Research objectives refer to the specific goals or aims of a research study. They provide a clear and concise description of what the researcher hopes to achieve by conducting the research . The objectives are typically based on the research questions and hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the study and are used to guide the research process.

Types of Research Objectives

Here are the different types of research objectives in research:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are used to explore a topic, issue, or phenomenon that has not been studied in-depth before. The aim of exploratory research is to gain a better understanding of the subject matter and generate new ideas and hypotheses .

- Descriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to describe the characteristics, features, or attributes of a particular population, group, or phenomenon. Descriptive research answers the “what” questions and provides a snapshot of the subject matter.

- Explanatory Objectives : These objectives aim to explain the relationships between variables or factors. Explanatory research seeks to identify the cause-and-effect relationships between different phenomena.

- Predictive Objectives: These objectives aim to predict future events or outcomes based on existing data or trends. Predictive research uses statistical models to forecast future trends or outcomes.

- Evaluative Objectives : These objectives aim to evaluate the effectiveness or impact of a program, intervention, or policy. Evaluative research seeks to assess the outcomes or results of a particular intervention or program.

- Prescriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to provide recommendations or solutions to a particular problem or issue. Prescriptive research identifies the best course of action based on the results of the study.

- Diagnostic Objectives : These objectives aim to identify the causes or factors contributing to a particular problem or issue. Diagnostic research seeks to uncover the underlying reasons for a particular phenomenon.

- Comparative Objectives: These objectives aim to compare two or more groups, populations, or phenomena to identify similarities and differences. Comparative research is used to determine which group or approach is more effective or has better outcomes.

- Historical Objectives: These objectives aim to examine past events, trends, or phenomena to gain a better understanding of their significance and impact. Historical research uses archival data, documents, and records to study past events.

- Ethnographic Objectives : These objectives aim to understand the culture, beliefs, and practices of a particular group or community. Ethnographic research involves immersive fieldwork and observation to gain an insider’s perspective of the group being studied.

- Action-oriented Objectives: These objectives aim to bring about social or organizational change. Action-oriented research seeks to identify practical solutions to social problems and to promote positive change in society.

- Conceptual Objectives: These objectives aim to develop new theories, models, or frameworks to explain a particular phenomenon or set of phenomena. Conceptual research seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the subject matter by developing new theoretical perspectives.

- Methodological Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and improve research methods and techniques. Methodological research seeks to advance the field of research by improving the validity, reliability, and accuracy of research methods and tools.

- Theoretical Objectives : These objectives aim to test and refine existing theories or to develop new theoretical perspectives. Theoretical research seeks to advance the field of knowledge by testing and refining existing theories or by developing new theoretical frameworks.

- Measurement Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and validate measurement instruments, such as surveys, questionnaires, and tests. Measurement research seeks to improve the quality and reliability of data collection and analysis by developing and testing new measurement tools.

- Design Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and refine research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational designs. Design research seeks to improve the quality and validity of research by developing and testing new research designs.

- Sampling Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and refine sampling techniques, such as probability and non-probability sampling methods. Sampling research seeks to improve the representativeness and generalizability of research findings by developing and testing new sampling techniques.

How to Write Research Objectives

Writing clear and concise research objectives is an important part of any research project, as it helps to guide the study and ensure that it is focused and relevant. Here are some steps to follow when writing research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Before you can write research objectives, you need to identify the research problem you are trying to address. This should be a clear and specific problem that can be addressed through research.

- Define the research questions : Based on the research problem, define the research questions you want to answer. These questions should be specific and should guide the research process.

- Identify the variables : Identify the key variables that you will be studying in your research. These are the factors that you will be measuring, manipulating, or analyzing to answer your research questions.

- Write specific objectives: Write specific, measurable objectives that will help you answer your research questions. These objectives should be clear and concise and should indicate what you hope to achieve through your research.

- Use the SMART criteria: To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and achievable, use the SMART criteria. This means that your objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound.

- Revise and refine: Once you have written your research objectives, revise and refine them to ensure that they are clear, concise, and achievable. Make sure that they align with your research questions and variables, and that they will help you answer your research problem.

Example of Research Objectives

Examples of research objectives Could be:

Research Objectives for the topic of “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment”:

- To investigate the effects of the adoption of AI on employment trends across various industries and occupations.

- To explore the potential for AI to create new job opportunities and transform existing roles in the workforce.

- To examine the social and economic implications of the widespread use of AI for employment, including issues such as income inequality and access to education and training.

- To identify the skills and competencies that will be required for individuals to thrive in an AI-driven workplace, and to explore the role of education and training in developing these skills.

- To evaluate the ethical and legal considerations surrounding the use of AI for employment, including issues such as bias, privacy, and the responsibility of employers and policymakers to protect workers’ rights.

When to Write Research Objectives

- At the beginning of a research project : Research objectives should be identified and written down before starting a research project. This helps to ensure that the project is focused and that data collection and analysis efforts are aligned with the intended purpose of the research.

- When refining research questions: Writing research objectives can help to clarify and refine research questions. Objectives provide a more concrete and specific framework for addressing research questions, which can improve the overall quality and direction of a research project.

- After conducting a literature review : Conducting a literature review can help to identify gaps in knowledge and areas that require further research. Writing research objectives can help to define and focus the research effort in these areas.

- When developing a research proposal: Research objectives are an important component of a research proposal. They help to articulate the purpose and scope of the research, and provide a clear and concise summary of the expected outcomes and contributions of the research.

- When seeking funding for research: Funding agencies often require a detailed description of research objectives as part of a funding proposal. Writing clear and specific research objectives can help to demonstrate the significance and potential impact of a research project, and increase the chances of securing funding.

- When designing a research study : Research objectives guide the design and implementation of a research study. They help to identify the appropriate research methods, sampling strategies, data collection and analysis techniques, and other relevant aspects of the study design.

- When communicating research findings: Research objectives provide a clear and concise summary of the main research questions and outcomes. They are often included in research reports and publications, and can help to ensure that the research findings are communicated effectively and accurately to a wide range of audiences.

- When evaluating research outcomes : Research objectives provide a basis for evaluating the success of a research project. They help to measure the degree to which research questions have been answered and the extent to which research outcomes have been achieved.

- When conducting research in a team : Writing research objectives can facilitate communication and collaboration within a research team. Objectives provide a shared understanding of the research purpose and goals, and can help to ensure that team members are working towards a common objective.

Purpose of Research Objectives

Some of the main purposes of research objectives include:

- To clarify the research question or problem : Research objectives help to define the specific aspects of the research question or problem that the study aims to address. This makes it easier to design a study that is focused and relevant.

- To guide the research design: Research objectives help to determine the research design, including the research methods, data collection techniques, and sampling strategy. This ensures that the study is structured and efficient.

- To measure progress : Research objectives provide a way to measure progress throughout the research process. They help the researcher to evaluate whether they are on track and meeting their goals.

- To communicate the research goals : Research objectives provide a clear and concise description of the research goals. This helps to communicate the purpose of the study to other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public.

Advantages of Research Objectives

Here are some advantages of having well-defined research objectives:

- Focus : Research objectives help to focus the research effort on specific areas of inquiry. By identifying clear research questions, the researcher can narrow down the scope of the study and avoid getting sidetracked by irrelevant information.

- Clarity : Clearly stated research objectives provide a roadmap for the research study. They provide a clear direction for the research, making it easier for the researcher to stay on track and achieve their goals.

- Measurability : Well-defined research objectives provide measurable outcomes that can be used to evaluate the success of the research project. This helps to ensure that the research is effective and that the research goals are achieved.

- Feasibility : Research objectives help to ensure that the research project is feasible. By clearly defining the research goals, the researcher can identify the resources required to achieve those goals and determine whether those resources are available.

- Relevance : Research objectives help to ensure that the research study is relevant and meaningful. By identifying specific research questions, the researcher can ensure that the study addresses important issues and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Publish a Research Paper – Step by Step...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Data Analysis – Process, Methods and Types

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

Dissertation Methodology – Structure, Example...

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

Research Objectives | Examples & How To Write Them

Introduction

Why are research objectives important, characteristics of research objectives, what is an example of a research objective, types of research objectives, formulating research objectives.

Research objectives are clear, concise statements that outline what a research project aims to achieve. They guide the direction of the study, ensuring that researchers stay focused and organized. Properly formulated objectives help in identifying the scope of the research and the methods to be used. This article will cover the importance of research objectives, their characteristics, examples, types, and how to write them. By understanding these elements, researchers can develop effective research aims that enhance the clarity and purpose of their studies. This straightforward approach will provide practical guidance for both novice and experienced researchers in crafting clear research objectives.

Research objectives are crucial because they provide a clear focus and direction for a study. A well-defined research aim can help researchers stay on track by outlining specific goals that need to be achieved. This clarity ensures that all aspects of the research are aligned with the intended outcomes.

Having well-defined objectives also facilitates effective planning and execution. Researchers can allocate resources more efficiently, select appropriate methodologies , and set realistic timelines. Moreover, clear objectives help in the assessment and evaluation of the research process and its outcomes, making it easier to determine whether the study has been successful.

Research objectives also enhance communication. They allow researchers to clearly convey the purpose and scope of their study to stakeholders, including funding bodies, academic peers, and participants. This transparency builds credibility and trust, which are essential for the integrity of the research process.

Research objectives possess several key characteristics that make them effective and useful for guiding a study. These characteristics ensure that the objectives are clear, achievable, and relevant to the research problem . Here are the essential characteristics to keep in mind when you develop research objectives for a successful research project.

- Specific : Research objectives focus on what the researcher intends to accomplish in a precise and unambiguous manner. Specific objectives break a research study into discrete and manageable tasks.

- Measurable : Objectives should include criteria for measuring progress and success. This characteristic allows researchers to track their progress and determine whether the objectives have been achieved.

- Achievable : Objectives need to be realistic and attainable within the constraints of the research project, including time, resources, and expertise. Setting achievable goals prevents frustration and ensures steady progress.

- Relevant : Objectives must be aligned with the research problem and the overall purpose of the study. They should contribute directly to addressing the study's research question or research hypothesis.

- Time-bound : Objectives should have a clear timeline for completion. This characteristic helps in planning and managing the research process, ensuring that objectives are met within a specified period.

- Clear and concise : Objectives should be articulated in a straightforward manner, avoiding complex language and jargon. Clarity helps in communicating the objectives to others involved in the research process.

- Focused : Each objective should target a specific aspect of the research problem. Having focused objectives prevents the study from becoming too broad and unmanageable.

- Logical : Objectives should follow a logical sequence that reflects the research process. This characteristic ensures that the objectives build on one another and collectively contribute to the overall research aim.

- Feasible : Consider the availability of resources, including data, equipment, and personnel, when formulating objectives. Feasibility ensures that the objectives can be realistically achieved with the available resources.

- Ethical : Objectives should respect ethical standards and guidelines . They should consider the well-being of participants, confidentiality , and integrity of the research process.

By adhering to these characteristics, researchers can develop objectives that are effective in guiding their study. Clear and well-defined objectives not only enhance the research process but also improve the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

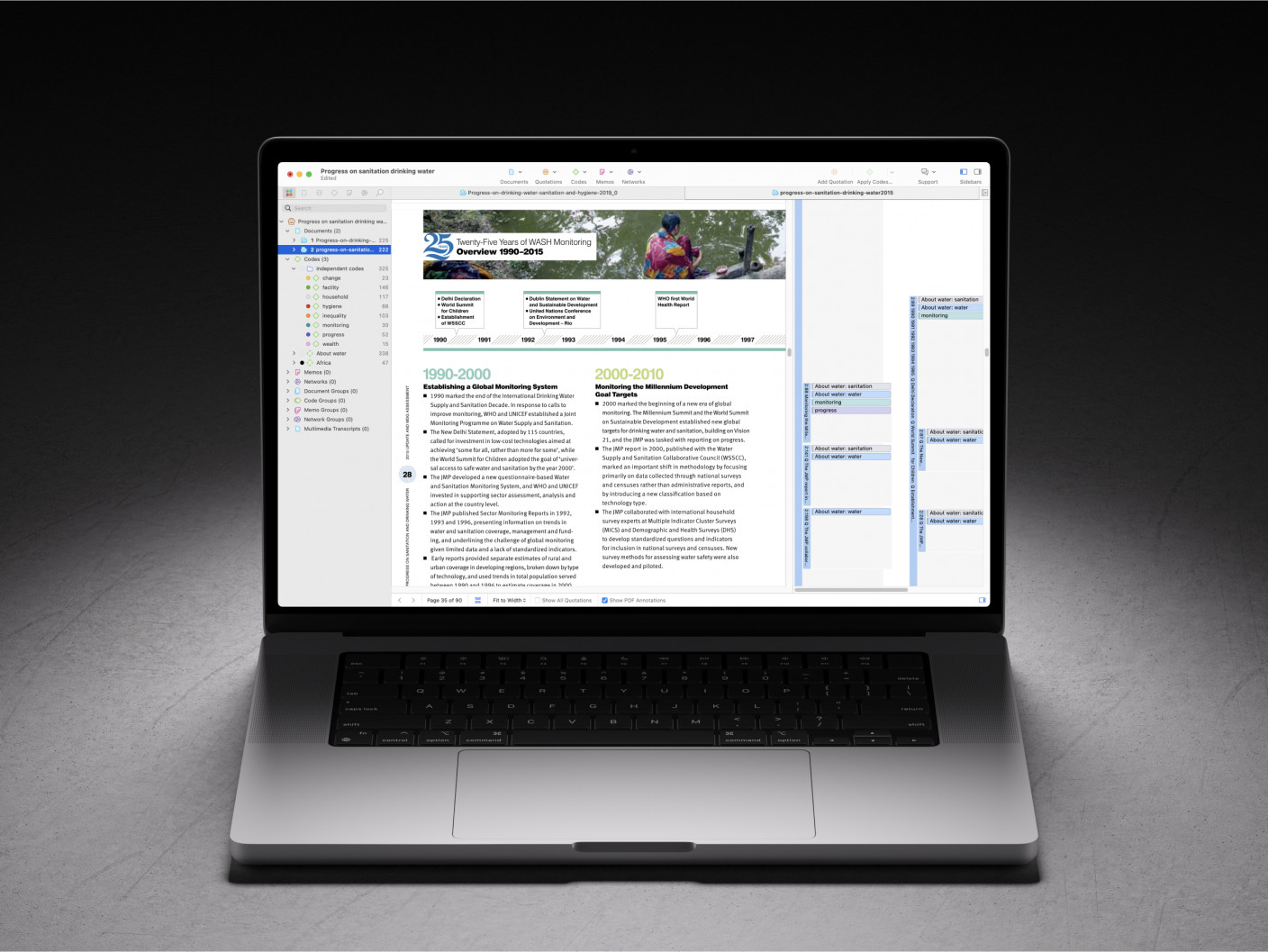

Scientific knowledge is easy to generate with ATLAS.ti

From collecting data to generating insights, do it all with ATLAS.ti. Get started with a free trial.

To illustrate what a well-defined research objective might look like, consider a study focused on improving reading comprehension among elementary school students. The research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a new instructional strategy designed to enhance students' reading skills. Here is an example of a research objective for this study:

"To assess the impact of the interactive reading program on the reading comprehension scores of third-grade students over a six-month period."

This objective is effective because it meets several key criteria:

- Specific : The objective clearly states what will be assessed (the impact of the interactive reading program) and the target group (third-grade students).

- Measurable : The impact will be measured by changes in reading comprehension scores, providing a clear metric for evaluation.

- Achievable : The objective is realistic and attainable within a six-month period, assuming the necessary resources and support are available.

- Relevant : The objective is directly related to the study's research questions , which is to improve reading comprehension among elementary school students.

- Time-bound : The objective specifies a six-month period for the assessment, ensuring that the study is conducted within a defined timeframe.

By formulating objectives in this manner, researchers can create a clear roadmap for their study from research design to research paper . This example demonstrates how to incorporate the essential characteristics of research objectives into a practical and actionable statement.

Well-defined objectives help in planning the study, selecting an appropriate research methodology , and evaluating the outcomes. They also facilitate effective communication among members of the research team and with stakeholders, ensuring that everyone involved understands the purpose and scope of the research.

Research objectives can be categorized into different types based on their purpose and focus. Understanding these types helps researchers design studies that effectively address their research questions . Here are three common types of research objectives:

Descriptive objectives

Descriptive objectives aim to describe the characteristics or functions of a particular phenomenon or group. These objectives are often used in exploratory studies to gather information and provide a detailed picture of the subject being investigated. For example, a descriptive objective might be, "To describe the dietary habits of teenagers in urban areas." This type of objective helps in understanding the current state or conditions of the research subject.

Exploratory objectives

Exploratory objectives seek to explore new areas of knowledge or investigate relationships between variables. These objectives are often used in the initial stages of research to identify patterns, generate propositions, or uncover insights that can lead to further studies. An example of an exploratory objective is, "To investigate the relationship between social media usage and academic performance among college students." This type of objective is useful for studies that aim to look into new or under-researched areas.

Explanatory objectives

Explanatory objectives aim to explain the causes or reasons behind a particular phenomenon. These objectives often involve verifying a theory or determining relationships among variables. For instance, an explanatory objective could be, "To determine the impact of a structured exercise program on the mental health of elderly individuals." This type of objective is essential for studies that seek to understand the underlying mechanisms or effects of specific interventions or conditions.

Writing research aims is a critical step in the research process . Well-defined objectives provide a roadmap for the study and help ensure that the research stays focused and relevant. Here are some steps to guide the formulation of research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Start by clearly defining the research problem or question you aim to address. Understanding the core issue helps in developing objectives that are directly related to the research focus.

- Conduct a literature review : Review existing research related to your topic to identify gaps in knowledge and areas that need further investigation. This background information can help in shaping specific and relevant objectives.

- Define the scope : Determine the scope of your study by considering factors such as the population, setting, and time frame. This will help in setting realistic and achievable objectives.

- Use the SMART criteria : Ensure that your objectives are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. This framework helps in creating clear and focused objectives that can guide the research process effectively.

- Break down the main objective : If your research has a broad aim, break it down into smaller, more specific sub-objectives. This makes the research more manageable and allows for a systematic approach to addressing the main research problem.

- Phrase objectives clearly : Write your objectives in clear and concise language, avoiding jargon and complex terms. Each objective should be easy to understand and communicate to others involved in the research.

- Align with research questions : Ensure that each objective aligns with your research question(s). The objectives should directly contribute to answering the key questions posed by your study.

- Seek feedback : Discuss your research objectives with peers, advisors, or experts in the field. Feedback can help refine the objectives and ensure that they are realistic and relevant.

Turn to ATLAS.ti for your research studies

Powerful data analysis with an intuitive interface is just a few clicks away. Download a free trial.

Writing a Research Statement

What is a research statement.

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential student's application for post-undergraduate study. The research statement is often the primary way for departments and faculty to determine if a student's interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

Although many programs ask for ‘personal statements,' these are not really meant to be biographies or life stories. What we, at Tufts Psychology, hope to find out is how well your abilities, interests, experiences and goals would fit within our program.

We encourage you to illustrate how your lived experience demonstrates qualities that are critical to success in pursuing a PhD in our program. Earning a PhD in any program is hard! Thus, as you are relaying your past, present, and future research interests, we are interested in learning how your lived experiences showcase the following:

- Perseverance

- Resilience in the face of difficulty

- Motivation to undertake intensive research training

- Involvement in efforts to promote equity and inclusion in your professional and/or personal life

- Unique perspectives that enrich the research questions you ask, the methods you use, and the communities to whom your research applies

How Do I Even Start Writing One?

Before you begin your statement, read as much as possible about our program so you can tailor your statement and convince the admissions committee that you will be a good fit.

Prepare an outline of the topics you want to cover (e.g., professional objectives and personal background) and list supporting material under each main topic. Write a rough draft in which you transform your outline into prose. Set it aside and read it a week later. If it still sounds good, go to the next stage. If not, rewrite it until it sounds right.

Do not feel bad if you do not have a great deal of experience in psychology to write about; no one who is about to graduate from college does. Do explain your relevant experiences (e.g., internships or research projects), but do not try to turn them into events of cosmic proportion. Be honest, sincere, and objective.

What Information Should It Include?

Your research statement should describe your previous experience, how that experience will facilitate your graduate education in our department, and why you are choosing to pursue graduate education in our department. Your goal should be to demonstrate how well you will fit in our program and in a specific laboratory.

Make sure to link your research interests to the expertise and research programs of faculty here. Identify at least one faculty member with whom you would like to work. Make sure that person is accepting graduate students when you apply. Read some of their papers and describe how you think the research could be extended in one or more novel directions. Again, specificity is a good idea.

Make sure to describe your relevant experience (e.g., honors thesis, research assistantship) in specific detail. If you have worked on a research project, discuss that project in detail. Your research statement should describe what you did on the project and how your role impacted your understanding of the research question.

Describe the concrete skills you have acquired prior to graduate school and the skills you hope to acquire.

Articulate why you want to pursue a graduate degree at our institution and with specific faculty in our department.

Make sure to clearly state your core research interests and explain why you think they are scientifically and/or practically important. Again, be specific.

What Should It Look Like?

Your final statement should be succinct. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application. Finally, stick to the points requested by each program, and avoid lengthy personal or philosophical discussions.

How Do I Know if It is Ready?

Ask for feedback from at least one professor, preferably in the area you are interested in. Feedback from friends and family may also be useful. Many colleges and universities also have writing centers that are able to provide general feedback.

Of course, read and proofread the document multiple times. It is not always easy to be a thoughtful editor of your own work, so don't be afraid to ask for help.

Lastly, consider signing up to take part in the Application Statement Feedback Program . The program provides constructive feedback and editing support for the research statements of applicants to Psychology PhD programs in the United States.

Handy Tips To Write A Clear Research Objectives With Examples

Introduction.

Research objectives play a crucial role in any research study. They provide a clear direction and purpose for the research, guiding the researcher in their investigation. Understanding research objectives is essential for conducting a successful study and achieving meaningful results.

In this comprehensive review, we will delve into the definition of research objectives, exploring their characteristics, types, and examples. We will also discuss the relationship between research objectives and research questions, as well as provide insights into how to write effective research objectives. Additionally, we will examine the role of research objectives in research methodology and highlight the importance of them in a study. By the end of this review, you will have a comprehensive understanding of research objectives and their significance in the research process.

Definition of Research Objectives: What Are They?

A research objective is defined as a clear and concise statement that outlines the specific goals and aims of a research study. These objectives are designed to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), ensuring they provide a structured pathway to accomplishing the intended outcomes of the project. Each objective serves as a foundational element that summarizes the purpose of your study, guiding the research activities and helping to measure progress toward the study’s goals. Additionally, research objectives are integral components of the research framework , establishing a clear direction that aligns with the overall research questions and hypotheses. This alignment helps to ensure that the study remains focused and relevant, facilitating the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Characteristics of Effective Research Objectives

Characteristics of research objectives include:

- Specific: Research objectives should be clear about the what, why, when, and how of the study.

- Measurable: Research objectives should identify the main variables of the study that can be measured or observed.

- Relevant: Research objectives should be relevant to the research topic and contribute to the overall understanding of the subject.

- Feasible: Research objectives should be achievable within the constraints of time, resources, and expertise available.

- Logical: Research objectives should follow a logical sequence and build upon each other to achieve the overall research goal.

- Observable: Research objectives should be observable or measurable in order to assess the progress and success of the research project.

- Unambiguous: Research objectives should be clear and unambiguous, leaving no room for interpretation or confusion.

- Measurable: Research objectives should be measurable, allowing for the collection of data and analysis of results.

By incorporating these characteristics into research objectives, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, achievable, and contributes to the body of knowledge in their field.

Types of Research Objectives

Research objective can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives. General objectives are broad statements that define the overall purpose of the research. They provide a broad direction for the study and help in setting the context. Specific objectives, on the other hand, are detailed objectives that describe what will be researched during the study. They are more focused and provide specific outcomes that the researcher aims to achieve. Specific objectives are derived from the general objectives and help in breaking down the research into smaller, manageable parts. The specific objectives should be clear, measurable, and achievable. They should be designed in a way that allows the researcher to answer the research questions and address the research problem.

In addition to general and specific objectives, research objective can also be categorized as descriptive or analytical objectives. Descriptive objectives focus on describing the characteristics or phenomena of a particular subject or population. They involve surveys, observations, and data collection to provide a detailed understanding of the subject. Analytical objectives, on the other hand, aim to analyze the relationships between variables or factors. They involve data analysis and interpretation to gain insights and draw conclusions.

Both descriptive and analytical objectives are important in research as they serve different purposes and contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

Examples of Research Objectives

Here are some examples of research objectives in different fields:

1. Objective: To identify key characteristics and styles of Renaissance art.

This objective focuses on exploring the characteristics and styles of art during the Renaissance period. The research may involve analyzing various artworks, studying historical documents, and interviewing experts in the field.

2. Objective: To analyze modern art trends and their impact on society.

This objective aims to examine the current trends in modern art and understand how they influence society. The research may involve analyzing artworks, conducting surveys or interviews with artists and art enthusiasts, and studying the social and cultural implications of modern art.

3. Objective: To investigate the effects of exercise on mental health.

This objective focuses on studying the relationship between exercise and mental health. The research may involve conducting experiments or surveys to assess the impact of exercise on factors such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

4. Objective: To explore the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the fashion industry.

This objective aims to understand the various factors that influence consumers’ purchasing decisions in the fashion industry. The research may involve conducting surveys, analyzing consumer behavior data, and studying the impact of marketing strategies on consumer choices.

5. Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a new drug in treating a specific medical condition.

This objective focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of a newly developed drug in treating a particular medical condition. The research may involve conducting clinical trials, analyzing patient data, and comparing the outcomes of the new drug with existing treatment options.

These examples demonstrate the diversity of research objectives across different disciplines. Each objective is specific, measurable, and achievable, providing a clear direction for the research study.

Aligning Research Objectives with Research Questions

Research objectives and research questions are essential components of a research project. Research objective describe what you intend your research project to accomplish. They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and provide a clear direction for the research. Research questions, on the other hand, are the starting point of any good research. They guide the overall direction of the research and help identify and focus on the research gaps .

The main difference between research questions and objectives is their form. Research questions are stated in a question form, while objectives are specific, measurable, and achievable goals that you aim to accomplish within a specified timeframe. Research questions are broad statements that provide a roadmap for the research, while objectives break down the research aim into smaller, actionable steps.

Research objectives and research questions work together to form the ‘golden thread’ of a research project. The research aim specifies what the study will answer, while the objectives and questions specify how the study will answer it. They provide a clear focus and scope for the research project, helping researchers stay on track and ensure that their study is meaningful and relevant.

When writing research objectives and questions, it is important to be clear, concise, and specific. Each objective or question should address a specific aspect of the research and contribute to the overall goal of the study. They should also be measurable, meaning that their achievement can be assessed and evaluated. Additionally, research objectives and questions should be achievable within the given timeframe and resources of the research project. By clearly defining the objectives and questions, researchers can effectively plan and execute their research, leading to valuable insights and contributions to the field.

Guidelines for Writing Clear Research Objectives

Writing research objective is a crucial step in any research project. The objectives provide a clear direction and purpose for the study, guiding the researcher in their data collection and analysis. Here are some tips on how to write effective research objective:

1. Be clear and specific

Research objective should be written in a clear and specific manner. Avoid vague or ambiguous language that can lead to confusion. Clearly state what you intend to achieve through your research.

2. Use action verbs

Start your research objective with action verbs that describe the desired outcome. Action verbs such as ‘investigate’, ‘analyze’, ‘compare’, ‘evaluate’, or ‘identify’ help to convey the purpose of the study.

3. Align with research questions or hypotheses

Ensure that your research objectives are aligned with your research questions or hypotheses. The objectives should address the main goals of your study and provide a framework for answering your research questions or testing your hypotheses.

4. Be realistic and achievable

Set research objectives that are realistic and achievable within the scope of your study. Consider the available resources, time constraints, and feasibility of your objectives. Unrealistic objectives can lead to frustration and hinder the progress of your research.

5. Consider the significance and relevance

Reflect on the significance and relevance of your research objectives. How will achieving these objectives contribute to the existing knowledge or address a gap in the literature? Ensure that your objectives have a clear purpose and value.

6. Seek feedback

It is beneficial to seek feedback on your research objectives from colleagues, mentors, or experts in your field. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving the clarity and effectiveness of your objectives.

7. Revise and refine

Research objectives are not set in stone. As you progress in your research, you may need to revise and refine your objectives to align with new findings or changes in the research context. Regularly review and update your objectives to ensure they remain relevant and focused.

By following these tips, you can write research objectives that are clear, focused, and aligned with your research goals. Well-defined objectives will guide your research process and help you achieve meaningful outcomes.

The Role of Research Objectives in Research Methodology

Research objectives play a crucial role in the research methodology . In research methodology, research objectives are formulated based on the research questions or problem statement. These objectives help in defining the scope and focus of the study, ensuring that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner.

The research objectives in research methodology act as a roadmap for the research project. They help in identifying the key variables to be studied, determining the research design and methodology, and selecting the appropriate data collection methods .

Furthermore, research objectives in research methodology assist in evaluating the success of the study. By setting clear objectives, researchers can assess whether the desired outcomes have been achieved and determine the effectiveness of the research methods employed. It is important to note that research objectives in research methodology should be aligned with the overall research aim. They should address the specific aspects or components of the research aim and provide a framework for achieving the desired outcomes.

Understanding The Dynamic of Research Objectives in Your Study

The research objectives of a study play a crucial role in guiding the research process, ensuring that the study is focused, purposeful, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field. It is important to note that the research objectives may evolve or change as the study progresses. As new information is gathered and analyzed, the researcher may need to revise the objectives to ensure that they remain relevant and achievable.

In summary, research objectives are essential components in writing an effective research paper . They provide a roadmap for the research process, guiding the researcher in their investigation and helping to ensure that the study is purposeful and meaningful. By understanding and effectively utilizing research objectives, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their research endeavors.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

7 Easy Step-By-Step Guide of Using ChatGPT: The Best Literature Review Generator for Time-Saving Academic Research

Writing Engaging Introduction in Research Papers : Tips and Tricks!

Understanding Comparative Frameworks: Their Importance, Components, Examples and 8 Best Practices

Revolutionizing Effective Thesis Writing for PhD Students Using Artificial Intelligence!

3 Types of Interviews in Qualitative Research: An Essential Research Instrument and Handy Tips to Conduct Them

Highlight Abstracts: An Ultimate Guide For Researchers!

Crafting Critical Abstracts: 11 Expert Strategies for Summarizing Research

Crafting the Perfect Informative Abstract: Definition, Importance and 8 Expert Writing Tips

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.

- Determine the relationship between changes in the geometry of the component and deformation for different cup designs.

- Develop three dimensional pelvis models with non-uniform bone material properties from a range of patients with varying bone quality.

- Use the key parameters that influence deformation, as identified in the foam models to determine the range of deformations that may occur clinically using the anatomic models and if these deformations are clinically significant.

It’s worth noting that researchers sometimes use research questions instead of research objectives, or in other cases both. From a high-level perspective, research questions and research objectives make the same statements, but just in different formats.

Taking the first three research objectives as an example, they can be restructured into research questions as follows:

Restructuring Research Objectives as Research Questions

- Can finite element models using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum together with explicit dynamics be used to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion?

- What is the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup?

- What is the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types?

Difference Between Aims and Objectives

Hopefully the above explanations make clear the differences between aims and objectives, but to clarify:

- The research aim focus on what the research project is intended to achieve; research objectives focus on how the aim will be achieved.

- Research aims are relatively broad; research objectives are specific.

- Research aims focus on a project’s long-term outcomes; research objectives focus on its immediate, short-term outcomes.

- A research aim can be written in a single sentence or short paragraph; research objectives should be written as a numbered list.

How to Write Aims and Objectives

Before we discuss how to write a clear set of research aims and objectives, we should make it clear that there is no single way they must be written. Each researcher will approach their aims and objectives slightly differently, and often your supervisor will influence the formulation of yours on the basis of their own preferences.

Regardless, there are some basic principles that you should observe for good practice; these principles are described below.

Your aim should be made up of three parts that answer the below questions:

- Why is this research required?

- What is this research about?

- How are you going to do it?

The easiest way to achieve this would be to address each question in its own sentence, although it does not matter whether you combine them or write multiple sentences for each, the key is to address each one.

The first question, why , provides context to your research project, the second question, what , describes the aim of your research, and the last question, how , acts as an introduction to your objectives which will immediately follow.

Scroll through the image set below to see the ‘why, what and how’ associated with our research aim example.

Note: Your research aims need not be limited to one. Some individuals per to define one broad ‘overarching aim’ of a project and then adopt two or three specific research aims for their thesis or dissertation. Remember, however, that in order for your assessors to consider your research project complete, you will need to prove you have fulfilled all of the aims you set out to achieve. Therefore, while having more than one research aim is not necessarily disadvantageous, consider whether a single overarching one will do.

Research Objectives

Each of your research objectives should be SMART :

- Specific – is there any ambiguity in the action you are going to undertake, or is it focused and well-defined?

- Measurable – how will you measure progress and determine when you have achieved the action?

- Achievable – do you have the support, resources and facilities required to carry out the action?

- Relevant – is the action essential to the achievement of your research aim?

- Timebound – can you realistically complete the action in the available time alongside your other research tasks?

In addition to being SMART, your research objectives should start with a verb that helps communicate your intent. Common research verbs include:

Table of Research Verbs to Use in Aims and Objectives

| (Understanding and organising information) | (Solving problems using information) | (reaching conclusion from evidence) | (Breaking down into components) | (Judging merit) |

| Review Identify Explore Discover Discuss Summarise Describe | Interpret Apply Demonstrate Establish Determine Estimate Calculate Relate | Analyse Compare Inspect Examine Verify Select Test Arrange | Propose Design Formulate Collect Construct Prepare Undertake Assemble | Appraise Evaluate Compare Assess Recommend Conclude Select |

Last, format your objectives into a numbered list. This is because when you write your thesis or dissertation, you will at times need to make reference to a specific research objective; structuring your research objectives in a numbered list will provide a clear way of doing this.

To bring all this together, let’s compare the first research objective in the previous example with the above guidance:

Checking Research Objective Example Against Recommended Approach

Research Objective:

1. Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

Checking Against Recommended Approach:

Q: Is it specific? A: Yes, it is clear what the student intends to do (produce a finite element model), why they intend to do it (mimic cup/shell blows) and their parameters have been well-defined ( using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum ).

Q: Is it measurable? A: Yes, it is clear that the research objective will be achieved once the finite element model is complete.

Q: Is it achievable? A: Yes, provided the student has access to a computer lab, modelling software and laboratory data.

Q: Is it relevant? A: Yes, mimicking impacts to a cup/shell is fundamental to the overall aim of understanding how they deform when impacted upon.

Q: Is it timebound? A: Yes, it is possible to create a limited-scope finite element model in a relatively short time, especially if you already have experience in modelling.

Q: Does it start with a verb? A: Yes, it starts with ‘develop’, which makes the intent of the objective immediately clear.

Q: Is it a numbered list? A: Yes, it is the first research objective in a list of eight.

Mistakes in Writing Research Aims and Objectives

1. making your research aim too broad.

Having a research aim too broad becomes very difficult to achieve. Normally, this occurs when a student develops their research aim before they have a good understanding of what they want to research. Remember that at the end of your project and during your viva defence , you will have to prove that you have achieved your research aims; if they are too broad, this will be an almost impossible task. In the early stages of your research project, your priority should be to narrow your study to a specific area. A good way to do this is to take the time to study existing literature, question their current approaches, findings and limitations, and consider whether there are any recurring gaps that could be investigated .

Note: Achieving a set of aims does not necessarily mean proving or disproving a theory or hypothesis, even if your research aim was to, but having done enough work to provide a useful and original insight into the principles that underlie your research aim.

2. Making Your Research Objectives Too Ambitious

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available. It is natural to want to set ambitious research objectives that require sophisticated data collection and analysis, but only completing this with six months before the end of your PhD registration period is not a worthwhile trade-off.

3. Formulating Repetitive Research Objectives

Each research objective should have its own purpose and distinct measurable outcome. To this effect, a common mistake is to form research objectives which have large amounts of overlap. This makes it difficult to determine when an objective is truly complete, and also presents challenges in estimating the duration of objectives when creating your project timeline. It also makes it difficult to structure your thesis into unique chapters, making it more challenging for you to write and for your audience to read.

Fortunately, this oversight can be easily avoided by using SMART objectives.

Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how to create an effective set of aims and objectives for your research project, whether it be a thesis, dissertation or research paper. While it may be tempting to dive directly into your research, spending time on getting your aims and objectives right will give your research clear direction. This won’t only reduce the likelihood of problems arising later down the line, but will also lead to a more thorough and coherent research project.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

- Defining Research Objectives: How To Write Them

Almost all industries use research for growth and development. Research objectives are how researchers ensure that their study has direction and makes a significant contribution to growing an industry or niche.

Research objectives provide a clear and concise statement of what the researcher wants to find out. As a researcher, you need to clearly outline and define research objectives to guide the research process and ensure that the study is relevant and generates the impact you want.

In this article, we will explore research objectives and how to leverage them to achieve successful research studies.

What Are Research Objectives?

Research objectives are what you want to achieve through your research study. They guide your research process and help you focus on the most important aspects of your topic.