- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2021

Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study

- Håkan Källmén 1 &

- Mats Hallgren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-2403 2

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 15 , Article number: 74 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

110k Accesses

18 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

To examine recent trends in bullying and mental health problems among adolescents and the association between them.

A questionnaire measuring mental health problems, bullying at school, socio-economic status, and the school environment was distributed to all secondary school students aged 15 (school-year 9) and 18 (school-year 11) in Stockholm during 2014, 2018, and 2020 (n = 32,722). Associations between bullying and mental health problems were assessed using logistic regression analyses adjusting for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors.

The prevalence of bullying remained stable and was highest among girls in year 9; range = 4.9% to 16.9%. Mental health problems increased; range = + 1.2% (year 9 boys) to + 4.6% (year 11 girls) and were consistently higher among girls (17.2% in year 11, 2020). In adjusted models, having been bullied was detrimentally associated with mental health (OR = 2.57 [2.24–2.96]). Reports of mental health problems were four times higher among boys who had been bullied compared to those not bullied. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.4 times higher.

Conclusions

Exposure to bullying at school was associated with higher odds of mental health problems. Boys appear to be more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls.

Introduction

Bullying involves repeated hurtful actions between peers where an imbalance of power exists [ 1 ]. Arseneault et al. [ 2 ] conducted a review of the mental health consequences of bullying for children and adolescents and found that bullying is associated with severe symptoms of mental health problems, including self-harm and suicidality. Bullying was shown to have detrimental effects that persist into late adolescence and contribute independently to mental health problems. Updated reviews have presented evidence indicating that bullying is causative of mental illness in many adolescents [ 3 , 4 ].

There are indications that mental health problems are increasing among adolescents in some Nordic countries. Hagquist et al. [ 5 ] examined trends in mental health among Scandinavian adolescents (n = 116, 531) aged 11–15 years between 1993 and 2014. Mental health problems were operationalized as difficulty concentrating, sleep disorders, headache, stomach pain, feeling tense, sad and/or dizzy. The study revealed increasing rates of adolescent mental health problems in all four counties (Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), with Sweden experiencing the sharpest increase among older adolescents, particularly girls. Worsening adolescent mental health has also been reported in the United Kingdom. A study of 28,100 school-aged adolescents in England found that two out of five young people scored above thresholds for emotional problems, conduct problems or hyperactivity [ 6 ]. Female gender, deprivation, high needs status (educational/social), ethnic background, and older age were all associated with higher odds of experiencing mental health difficulties.

Bullying is shown to increase the risk of poor mental health and may partly explain these detrimental changes. Le et al. [ 7 ] reported an inverse association between bullying and mental health among 11–16-year-olds in Vietnam. They also found that poor mental health can make some children and adolescents more vulnerable to bullying at school. Bayer et al. [ 8 ] examined links between bullying at school and mental health among 8–9-year-old children in Australia. Those who experienced bullying more than once a week had poorer mental health than children who experienced bullying less frequently. Friendships moderated this association, such that children with more friends experienced fewer mental health problems (protective effect). Hysing et al. [ 9 ] investigated the association between experiences of bullying (as a victim or perpetrator) and mental health, sleep disorders, and school performance among 16–19 year olds from Norway (n = 10,200). Participants were categorized as victims, bullies, or bully-victims (that is, victims who also bullied others). All three categories were associated with worse mental health, school performance, and sleeping difficulties. Those who had been bullied also reported more emotional problems, while those who bullied others reported more conduct disorders [ 9 ].

As most adolescents spend a considerable amount of time at school, the school environment has been a major focus of mental health research [ 10 , 11 ]. In a recent review, Saminathen et al. [ 12 ] concluded that school is a potential protective factor against mental health problems, as it provides a socially supportive context and prepares students for higher education and employment. However, it may also be the primary setting for protracted bullying and stress [ 13 ]. Another factor associated with adolescent mental health is parental socio-economic status (SES) [ 14 ]. A systematic review indicated that lower parental SES is associated with poorer adolescent mental health [ 15 ]. However, no previous studies have examined whether SES modifies or attenuates the association between bullying and mental health. Similarly, it remains unclear whether school related factors, such as school grades and the school environment, influence the relationship between bullying and mental health. This information could help to identify those adolescents most at risk of harm from bullying.

To address these issues, we investigated the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems among Swedish adolescents aged 15–18 years between 2014 and 2020 using a population-based school survey. We also examined associations between bullying at school and mental health problems adjusting for relevant demographic, socioeconomic, and school-related factors. We hypothesized that: (1) bullying and adolescent mental health problems have increased over time; (2) There is an association between bullying victimization and mental health, so that mental health problems are more prevalent among those who have been victims of bullying; and (3) that school-related factors would attenuate the association between bullying and mental health.

Participants

The Stockholm school survey is completed every other year by students in lower secondary school (year 9—compulsory) and upper secondary school (year 11). The survey is mandatory for public schools, but voluntary for private schools. The purpose of the survey is to help inform decision making by local authorities that will ultimately improve students’ wellbeing. The questions relate to life circumstances, including SES, schoolwork, bullying, drug use, health, and crime. Non-completers are those who were absent from school when the survey was completed (< 5%). Response rates vary from year to year but are typically around 75%. For the current study data were available for 2014, 2018 and 2020. In 2014; 5235 boys and 5761 girls responded, in 2018; 5017 boys and 5211 girls responded, and in 2020; 5633 boys and 5865 girls responded (total n = 32,722). Data for the exposure variable, bullied at school, were missing for 4159 students, leaving 28,563 participants in the crude model. The fully adjusted model (described below) included 15,985 participants. The mean age in grade 9 was 15.3 years (SD = 0.51) and in grade 11, 17.3 years (SD = 0.61). As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5). Details of the survey are available via a website [ 16 ], and are described in a previous paper [ 17 ].

Students completed the questionnaire during a school lesson, placed it in a sealed envelope and handed it to their teacher. Student were permitted the entire lesson (about 40 min) to complete the questionnaire and were informed that participation was voluntary (and that they were free to cancel their participation at any time without consequences). Students were also informed that the Origo Group was responsible for collection of the data on behalf of the City of Stockholm.

Study outcome

Mental health problems were assessed by using a modified version of the Psychosomatic Problem Scale [ 18 ] shown to be appropriate for children and adolescents and invariant across gender and years. The scale was later modified [ 19 ]. In the modified version, items about difficulty concentrating and feeling giddy were deleted and an item about ‘life being great to live’ was added. Seven different symptoms or problems, such as headaches, depression, feeling fear, stomach problems, difficulty sleeping, believing it’s great to live (coded negatively as seldom or rarely) and poor appetite were used. Students who responded (on a 5-point scale) that any of these problems typically occurs ‘at least once a week’ were considered as having indicators of a mental health problem. Cronbach alpha was 0.69 across the whole sample. Adding these problem areas, a total index was created from 0 to 7 mental health symptoms. Those who scored between 0 and 4 points on the total symptoms index were considered to have a low indication of mental health problems (coded as 0); those who scored between 5 and 7 symptoms were considered as likely having mental health problems (coded as 1).

Primary exposure

Experiences of bullying were measured by the following two questions: Have you felt bullied or harassed during the past school year? Have you been involved in bullying or harassing other students during this school year? Alternatives for the first question were: yes or no with several options describing how the bullying had taken place (if yes). Alternatives indicating emotional bullying were feelings of being mocked, ridiculed, socially excluded, or teased. Alternatives indicating physical bullying were being beaten, kicked, forced to do something against their will, robbed, or locked away somewhere. The response alternatives for the second question gave an estimation of how often the respondent had participated in bullying others (from once to several times a week). Combining the answers to these two questions, five different categories of bullying were identified: (1) never been bullied and never bully others; (2) victims of emotional (verbal) bullying who have never bullied others; (3) victims of physical bullying who have never bullied others; (4) victims of bullying who have also bullied others; and (5) perpetrators of bullying, but not victims. As the number of positive cases in the last three categories was low (range = 3–15 cases) bully categories 2–4 were combined into one primary exposure variable: ‘bullied at school’.

Assessment year was operationalized as the year when data was collected: 2014, 2018, and 2020. Age was operationalized as school grade 9 (15–16 years) or 11 (17–18 years). Gender was self-reported (boy or girl). The school situation To assess experiences of the school situation, students responded to 18 statements about well-being in school, participation in important school matters, perceptions of their teachers, and teaching quality. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘do not agree at all’ to ‘fully agree’. To reduce the 18-items down to their essential factors, we performed a principal axis factor analysis. Results showed that the 18 statements formed five factors which, according to the Kaiser criterion (eigen values > 1) explained 56% of the covariance in the student’s experience of the school situation. The five factors identified were: (1) Participation in school; (2) Interesting and meaningful work; (3) Feeling well at school; (4) Structured school lessons; and (5) Praise for achievements. For each factor, an index was created that was dichotomised (poor versus good circumstance) using the median-split and dummy coded with ‘good circumstance’ as reference. A description of the items included in each factor is available as Additional file 1 . Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed with three questions about the education level of the student’s mother and father (dichotomized as university degree versus not), and the amount of spending money the student typically received for entertainment each month (> SEK 1000 [approximately $120] versus less). Higher parental education and more spending money were used as reference categories. School grades in Swedish, English, and mathematics were measured separately on a 7-point scale and dichotomized as high (grades A, B, and C) versus low (grades D, E, and F). High school grades were used as the reference category.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of mental health problems and bullying at school are presented using descriptive statistics, stratified by survey year (2014, 2018, 2020), gender, and school year (9 versus 11). As noted, we reduced the 18-item questionnaire assessing school function down to five essential factors by conducting a principal axis factor analysis (see Additional file 1 ). We then calculated the association between bullying at school (defined above) and mental health problems using multivariable logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (Cis). To assess the contribution of SES and school-related factors to this association, three models are presented: Crude, Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors: age, gender, and assessment year; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 plus SES (parental education and student spending money), and Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 plus school-related factors (school grades and the five factors identified in the principal factor analysis). These covariates were entered into the regression models in three blocks, where the final model represents the fully adjusted analyses. In all models, the category ‘not bullied at school’ was used as the reference. Pseudo R-square was calculated to estimate what proportion of the variance in mental health problems was explained by each model. Unlike the R-square statistic derived from linear regression, the Pseudo R-square statistic derived from logistic regression gives an indicator of the explained variance, as opposed to an exact estimate, and is considered informative in identifying the relative contribution of each model to the outcome [ 20 ]. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 26.0.

Prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems

Estimates of the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems across the 12 strata of data (3 years × 2 school grades × 2 genders) are shown in Table 1 . The prevalence of bullying at school increased minimally (< 1%) between 2014 and 2020, except among girls in grade 11 (2.5% increase). Mental health problems increased between 2014 and 2020 (range = 1.2% [boys in year 11] to 4.6% [girls in year 11]); were three to four times more prevalent among girls (range = 11.6% to 17.2%) compared to boys (range = 2.6% to 4.9%); and were more prevalent among older adolescents compared to younger adolescents (range = 1% to 3.1% higher). Pooling all data, reports of mental health problems were four times more prevalent among boys who had been victims of bullying compared to those who reported no experiences with bullying. The corresponding figure for girls was two and a half times as prevalent.

Associations between bullying at school and mental health problems

Table 2 shows the association between bullying at school and mental health problems after adjustment for relevant covariates. Demographic factors, including female gender (OR = 3.87; CI 3.48–4.29), older age (OR = 1.38, CI 1.26–1.50), and more recent assessment year (OR = 1.18, CI 1.13–1.25) were associated with higher odds of mental health problems. In Model 2, none of the included SES variables (parental education and student spending money) were associated with mental health problems. In Model 3 (fully adjusted), the following school-related factors were associated with higher odds of mental health problems: lower grades in Swedish (OR = 1.42, CI 1.22–1.67); uninteresting or meaningless schoolwork (OR = 2.44, CI 2.13–2.78); feeling unwell at school (OR = 1.64, CI 1.34–1.85); unstructured school lessons (OR = 1.31, CI = 1.16–1.47); and no praise for achievements (OR = 1.19, CI 1.06–1.34). After adjustment for all covariates, being bullied at school remained associated with higher odds of mental health problems (OR = 2.57; CI 2.24–2.96). Demographic and school-related factors explained 12% and 6% of the variance in mental health problems, respectively (Pseudo R-Square). The inclusion of socioeconomic factors did not alter the variance explained.

Our findings indicate that mental health problems increased among Swedish adolescents between 2014 and 2020, while the prevalence of bullying at school remained stable (< 1% increase), except among girls in year 11, where the prevalence increased by 2.5%. As previously reported [ 5 , 6 ], mental health problems were more common among girls and older adolescents. These findings align with previous studies showing that adolescents who are bullied at school are more likely to experience mental health problems compared to those who are not bullied [ 3 , 4 , 9 ]. This detrimental relationship was observed after adjustment for school-related factors shown to be associated with adolescent mental health [ 10 ].

A novel finding was that boys who had been bullied at school reported a four-times higher prevalence of mental health problems compared to non-bullied boys. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.5 times higher for those who were bullied compared to non-bullied girls, which could indicate that boys are more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls. Alternatively, it may indicate that boys are (on average) bullied more frequently or more intensely than girls, leading to worse mental health. Social support could also play a role; adolescent girls often have stronger social networks than boys and could be more inclined to voice concerns about bullying to significant others, who in turn may offer supports which are protective [ 21 ]. Related studies partly confirm this speculative explanation. An Estonian study involving 2048 children and adolescents aged 10–16 years found that, compared to girls, boys who had been bullied were more likely to report severe distress, measured by poor mental health and feelings of hopelessness [ 22 ].

Other studies suggest that heritable traits, such as the tendency to internalize problems and having low self-esteem are associated with being a bully-victim [ 23 ]. Genetics are understood to explain a large proportion of bullying-related behaviors among adolescents. A study from the Netherlands involving 8215 primary school children found that genetics explained approximately 65% of the risk of being a bully-victim [ 24 ]. This proportion was similar for boys and girls. Higher than average body mass index (BMI) is another recognized risk factor [ 25 ]. A recent Australian trial involving 13 schools and 1087 students (mean age = 13 years) targeted adolescents with high-risk personality traits (hopelessness, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity, sensation seeking) to reduce bullying at school; both as victims and perpetrators [ 26 ]. There was no significant intervention effect for bullying victimization or perpetration in the total sample. In a secondary analysis, compared to the control schools, intervention school students showed greater reductions in victimization, suicidal ideation, and emotional symptoms. These findings potentially support targeting high-risk personality traits in bullying prevention [ 26 ].

The relative stability of bullying at school between 2014 and 2020 suggests that other factors may better explain the increase in mental health problems seen here. Many factors could be contributing to these changes, including the increasingly competitive labour market, higher demands for education, and the rapid expansion of social media [ 19 , 27 , 28 ]. A recent Swedish study involving 29,199 students aged between 11 and 16 years found that the effects of school stress on psychosomatic symptoms have become stronger over time (1993–2017) and have increased more among girls than among boys [ 10 ]. Research is needed examining possible gender differences in perceived school stress and how these differences moderate associations between bullying and mental health.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large participant sample from diverse schools; public and private, theoretical and practical orientations. The survey included items measuring diverse aspects of the school environment; factors previously linked to adolescent mental health but rarely included as covariates in studies of bullying and mental health. Some limitations are also acknowledged. These data are cross-sectional which means that the direction of the associations cannot be determined. Moreover, all the variables measured were self-reported. Previous studies indicate that students tend to under-report bullying and mental health problems [ 29 ]; thus, our results may underestimate the prevalence of these behaviors.

In conclusion, consistent with our stated hypotheses, we observed an increase in self-reported mental health problems among Swedish adolescents, and a detrimental association between bullying at school and mental health problems. Although bullying at school does not appear to be the primary explanation for these changes, bullying was detrimentally associated with mental health after adjustment for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors, confirming our third hypothesis. The finding that boys are potentially more vulnerable than girls to the deleterious effects of bullying should be replicated in future studies, and the mechanisms investigated. Future studies should examine the longitudinal association between bullying and mental health, including which factors mediate/moderate this relationship. Epigenetic studies are also required to better understand the complex interaction between environmental and biological risk factors for adolescent mental health [ 24 ].

Availability of data and materials

Data requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis; please email the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(9):751–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 .

Article Google Scholar

Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20399 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 .

Hagquist C, Due P, Torsheim T, Valimaa R. Cross-country comparisons of trends in adolescent psychosomatic symptoms—a Rasch analysis of HBSC data from four Nordic countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1097-x .

Deighton J, Lereya ST, Casey P, Patalay P, Humphrey N, Wolpert M. Prevalence of mental health problems in schools: poverty and other risk factors among 28 000 adolescents in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(3):565–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.19 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Le HTH, Tran N, Campbell MA, Gatton ML, Nguyen HT, Dunne MP. Mental health problems both precede and follow bullying among adolescents and the effects differ by gender: a cross-lagged panel analysis of school-based longitudinal data in Vietnam. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0291-x .

Bayer JK, Mundy L, Stokes I, Hearps S, Allen N, Patton G. Bullying, mental health and friendship in Australian primary school children. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;23(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12261 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hysing M, Askeland KG, La Greca AM, Solberg ME, Breivik K, Sivertsen B. Bullying involvement in adolescence: implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519853409 .

Hogberg B, Strandh M, Hagquist C. Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years—the role of school-related stress. Soc Sci Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112890 .

Kidger J, Araya R, Donovan J, Gunnell D. The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):925–49. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2248 .

Saminathen MG, Låftman SB, Modin B. En fungerande skola för alla: skolmiljön som skyddsfaktor för ungas psykiska välbefinnande. [A functioning school for all: the school environment as a protective factor for young people’s mental well-being]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2020;97(5–6):804–16.

Google Scholar

Bibou-Nakou I, Tsiantis J, Assimopoulos H, Chatzilambou P, Giannakopoulou D. School factors related to bullying: a qualitative study of early adolescent students. Soc Psychol Educ. 2012;15(2):125–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9179-1 .

Vukojevic M, Zovko A, Talic I, Tanovic M, Resic B, Vrdoljak I, Splavski B. Parental socioeconomic status as a predictor of physical and mental health outcomes in children—literature review. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(4):742–8. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2017.56.04.23 .

Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026 .

Stockholm City. Stockholmsenkät (The Stockholm Student Survey). 2021. https://start.stockholm/aktuellt/nyheter/2020/09/presstraff-stockholmsenkaten-2020/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2021.

Zeebari Z, Lundin A, Dickman PW, Hallgren M. Are changes in alcohol consumption among swedish youth really occurring “in concert”? A new perspective using quantile regression. Alc Alcohol. 2017;52(4):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx020 .

Hagquist C. Psychometric properties of the PsychoSomatic Problems Scale: a Rasch analysis on adolescent data. Social Indicat Res. 2008;86(3):511–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9186-3 .

Hagquist C. Ungas psykiska hälsa i Sverige–komplexa trender och stora kunskapsluckor [Young people’s mental health in Sweden—complex trends and large knowledge gaps]. Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [Soc Med]. 2013;90(5):671–83.

Wu W, West SG. Detecting misspecification in mean structures for growth curve models: performance of pseudo R(2)s and concordance correlation coefficients. Struct Equ Model. 2013;20(3):455–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.797829 .

Holt MK, Espelage DL. Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. J Youth Adolscence. 2007;36(8):984–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3 .

Mark L, Varnik A, Sisask M. Who suffers most from being involved in bullying-bully, victim, or bully-victim? J Sch Health. 2019;89(2):136–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12720 .

Tsaousis I. The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2016;31:186–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005 .

Veldkamp SAM, Boomsma DI, de Zeeuw EL, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Dolan CV, van Bergen E. Genetic and environmental influences on different forms of bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and their co-occurrence. Behav Genet. 2019;49(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-019-09968-5 .

Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1187–94. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.5.1187 .

Kelly EV, Newton NC, Stapinski LA, Conrod PJ, Barrett EL, Champion KE, Teesson M. A novel approach to tackling bullying in schools: personality-targeted intervention for adolescent victims and bullies in Australia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(4):508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.010 .

Gunnell D, Kidger J, Elvidge H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2608 .

O’Reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23:601–13.

Unnever JD, Cornell DG. Middle school victims of bullying: who reports being bullied? Aggr Behav. 2004;30(5):373–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20030 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the Department for Social Affairs, Stockholm, for permission to use data from the Stockholm School Survey.

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. None to declare.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm Prevents Alcohol and Drug Problems (STAD), Center for Addiction Research and Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

Håkan Källmén

Epidemiology of Psychiatric Conditions, Substance Use and Social Environment (EPiCSS), Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Level 6, Solnavägen 1e, Solna, Sweden

Mats Hallgren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HK conceived the study and analyzed the data (with input from MH). HK and MH interpreted the data and jointly wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mats Hallgren .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Principal factor analysis description.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Källmén, H., Hallgren, M. Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 15 , 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2021

Accepted : 23 November 2021

Published : 14 December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00425-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Adolescents

- School-related factors

- Gender differences

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health

ISSN: 1753-2000

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Bullying: issues and challenges in prevention and intervention

- Published: 12 August 2023

- Volume 43 , pages 9270–9279, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Muhammad Waseem ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8720-955X 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Amanda B. Nickerson 4

1438 Accesses

3 Citations

68 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Bullying is a public health issue that persists and occurs across several contexts. In this narrative review, we highlight issues and challenges in addressing bullying prevention. Specifically, we discuss issues related to defining, measuring, and screening for bullying. These include discrepancies in the interpretation and measurement of power imbalance, repetition of behavior, and perceptions of the reporter. The contexts of bullying, both within and outside of the school setting (including the online environment), are raised as an important issue relevant for identification and prevention. The role of medical professionals in screening for bullying is also noted. Prevention and intervention approaches are reviewed, and we highlight the need and evidence for social architectural interventions that involve multiple stakeholders, including parents, in these efforts. Areas in need are identified, such as understanding and intervening in cyberbullying, working more specifically with perpetrators as a heterogeneous group, and providing more intensive interventions for the most vulnerable youth who remain at risk despite universal prevention efforts.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Updated Perspectives on Linking School Bullying and Related Youth Violence Research to Effective Prevention Strategies

Bullying and Cyberbullying Throughout Adolescence

Explore related subjects

- Medical Ethics

Data availability

This manuscript does not involve patient data. This is a review based on the published literature.

Allen, K. P. (2010a). A bullying intervention system in high school: A two-year school-wide follow-up. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 36 (3), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.01.002

Article Google Scholar

Allen, K. P. (2010b). A bullying intervention system: Reducing risk and creating support for aggressive students. Preventing School Failure, 54 (3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903496289

American Educational Research Association (2013). Prevention of bullying in schools, colleges, and universities: Research report and recommendations . https://www.aera.net/Education-Research/Issues-and-Initiatives/Bullying-Prevention-and-School-Safety/Bullying-Prevention

Axford, N., Bjornstad, G., Clarkson, S., Ukoumunne, O. C., Wrigley, Z., Matthews, J., Berry, V., & Hutchings, J. (2020). The effectiveness of the KiVa bullying prevention program in Wales, UK: Results from a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 21 (5), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01103-9

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2007). Effectiveness of programs to prevent school bullying. Victims & Offenders, 2 (2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564880701263155

Barboza, G. E., Schiamberg, L. B., Oehmke, J., Korzeniewski, S. J., Post, L. A., & Heraux, C. G. (2009). Individual characteristics and the multiple contexts of adolescent bullying: An ecological perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38 (1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9271-1

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bauman, S. (2016). Do we need more measures of bullying? The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59 (5), 487–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.021

Bear, G. G., Mantz, L. S., Glutting, J. J., Yang, C., & Boyer, D. E. (2015). Differences in bullying victimization between students with and without disabilities. School Psychology Review, 44 (1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR44-1.98-116

Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O. M., & Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. School Psychology Quarterly, 27 (4), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000008

Borgen, N. T., Olweus, D., Kirkebøen, L. J., Breivik, K., Solberg, M. E., Frønes, I., Cross, D., & Raaum, O. (2021). The potential of anti-bullying efforts to prevent academic failure and youth crime. A case using the Olweus bullying prevention program (OBPP). Prevention Science, 22 , 1147–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01254-3

Bostic, J. Q., & Brunt, C. C. (2011). Cornered: An approach to school bullying and cyberbullying, and forensic implications. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20 (3), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.03.004

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039114

Camodeca, M., & Nava, E. (2022). The long-term effects of bullying, victimization, and bystander behavior on emotion regulation and its physiological correlates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37 (3–4), NP2056–NP2075. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520934438

Carter, S. (2011). Bullies and power: A look at the research. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34 (2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2011.574455

Cascardi, M., Brown, C., Iannarone, M., & Cardona, N. (2014). The problem with overly broad definitions of bullying: Implications for the schoolhouse, the statehouse, and the ivory tower. Journal of School Violence, 13 (3), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2013.846861

Chen, Q., Zhu, Y., & Chui, W. H. (2021). A meta-analysis on the effects of parenting programs on bullying prevention. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22 (5), 1209–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020915619

Cheng, Y. Y., Chen, L. M., Ho, H. C., & Cheng, C. L. (2011). Definitions of school bullying in Taiwan: A comparison of multiple perspectives. School Psychology International, 32 (3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034313479694

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25 (2), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020149

Cosgrove, H., & Nickerson, A. B. (2015). Anti-bullying/harassment legislation and educator perceptions of severity, effectiveness, and school climate: A cross-sectional analysis. Educational Policy, 31 (4), 518–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815604217

Dale, J., Russell, R., & Wolke, D. (2014). Intervening in primary care against childhood bullying: An increasingly pressing public health need. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107 (6), 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814525071

Deshmukh, P., & Kaplan, S. (2018). Bullying as a risk factor for inpatient hospitalization: Let’s change it! Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57 (10), S260–S260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.09.397

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82 (1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32 (3), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2003.12086206

Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Polanin, J. R., & Brown, E. C. (2013). The impact of a middle school program to reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 53 (2), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.021

Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Polanin, J. R. (2015). Clinical trial of second step middle school program: Impact on bullying, cyberbullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment perpetration. School Psychology Review, 44 (4), 464–479. https://doi.org/10.17105/spr-15-0052.1

Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 5 (1), 148. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2009.6

Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2011). Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21 (2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.801

Felix, E. D., Sharkey, J. D., Green, J. G., Furlong, M. J., & Tanigawa, D. (2011). Getting precise and pragmatic about the assessment of bullying: The development of the California bullying victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 37 (3), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20389

Fredrick, S. S., Nickerson, A. B., & Livingston, J. A. (2021). Family cohesion and the relations among peer victimization and depression: A random intercepts cross-lagged model. Development and Psychopathology, 34 (4), 1429–1446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942100016X

Frey, K. S., Hirschstein, M. K., Snell, J. L., Edstrom, L. V., MacKenzie, E. P., & Broderick, C. J. (2005). Reducing playground bullying and supporting beliefs: An experimental trial of the steps to respect program. Developmental Psychology, 41 (3), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.479

Frey, K. S., Hirschstein, M. K., Edstrom, L. V., & Snell, J. L. (2009). Observed reductions in school bullying, nonbullying aggression and destructive bystander behavior: A longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (2), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013839

Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., Espelage, D. L., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019a). Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45 , 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.002

Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2019b). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45 , 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

Garandeau, C. F., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). Tackling acute cases of school bullying in the KiVa anti-bullying program: A comparison of two approaches. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42 (6), 981–991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9861-1

Garandeau, C. F., Vartio, A., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2016). School bullies' intention to change behavior following teacher interventions: Effects of empathy arousal, condemning of bullying, and blaming of the perpetrator. Prevention Science, 17 (8), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0712-x

Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2018). Decreases in the proportion of bullying victims in the classroom: Effects on the adjustment of remaining victims. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42 (1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416667492

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0 . National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved October 23, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf

Gómez Baya, D., Rubio Gónzalez, A., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2018). Online communication, peer relationships and school victimisation: A one-year longitudinal study during middle adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24 (2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1509793

Good, C. P., McIntosh, K., & Gietz, C. (2011). Integrating bullying prevention into schoolwide positive behavior support. Teaching Exceptional Children, 244 , 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005991104400106

Hagan, J. F., Shaw, J. S., & Duncan, P. M. (Eds.) (2017). Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (4th Ed) . American Academy of Pediatrics. https://brightfutures.aap.org/Bright%20Futures%20Documents/BF4_Introduction.pdf

Hall, W. (2017). The effectiveness of policy interventions for school bullying: A systematic review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8 (1), 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1086/690565

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Schwab-Reese, L., Ranapurwala, S. I., Hertz, M. F., & Ramirez, M. R. (2015). Associations between antibullying policies and bullying in 25 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 169 (10), e152411. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2411

Hensley, V. (2015). Childhood bullying: Assessment practices and predictive factors associated with assessing for bullying by health care providers . University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved October 23, 2021 from https://uknowledge.uky.edu/nursing_etds/25

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2015). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Google Scholar

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17 (4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Huang, Y., Espelage, D. L., Polanin, J. R., & Hong, J. S. (2019). A meta-analytic review of school-based anti-bullying programs with a parent component. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1 (1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-018-0002-1

Huitsing, G., Lodder, G. M. A., Browne, W. J., Oldenburg, B., Van der Ploeg, R., & Veenstra, R. (2020). A large-scale replication of the effectiveness of the KiVa Antibullying program: A randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands. Prevention Science, 21 (5), 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01116-4

Hutson, E., Melnyk, B., Hensley, V., & Sinnott, L. T. (2019). Childhood bullying: Screening and intervening practices of pediatric primary care providers. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 33 (6), e39–e45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.07.003

Ireland, J. L. (2000). "bullying" among prisoners: A review of research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5 (2), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00031-7

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Little, T. D., Poskiparta, E., Alanen, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). Going to scale: A nonrandomized nationwide trial of the KiVa antibullying program for grades 1–9. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79 , 796–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025740

Kert, A. S., Codding, R. S., Tryon, G. S., & Shiyko, M. (2010). Impact of the word “bully” on the reported rate of bullying behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 47 (2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20464

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140 (4), 1073–1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Koyanagi, A., Oh, H., Carvalho, A. F., Smith, L., Haro, J. M., Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., & DeVylder, J. E. (2019). Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 48 countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 58 (9), 907–918.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.018

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2 (6), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00165-0

Lund, E. M., & Ross, S. W. (2017). Bullying perpetration, victimization, and demographic differences in college students: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18 (3), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015620818

Merrell, K. W., Gueldner, B. A., Ross, S. W., & Isava, D. M. (2008). How effective are school bullying intervention programs? A meta-analysis of intervention research. School Psychology Quarterly, 23 (1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.26

Mishna, F. (2004). A qualitative study of bullying from multiple perspectives. Children & Schools, 26 (4), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/26.4.234

Mishna, F., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. (2006). Factors associated with perceptions and responses to bullying situations by children, parents, teachers, and principals. Victims & Offenders, 1 (3), 255–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564880600626163

Monks, C. P., Smith, P. K., Naylor, P., Barter, C., Ireland, J. L., & Coyne, I. (2009). Bullying in different contexts: Commonalities, differences, and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14 , 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.004

Morcillo, C., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., Blanco, C., Sala, R., Canino, G., Bird, H., & Duarte, C. S. (2015). Socio-cultural context and bullying others in childhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 (8), 2241–2249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0026-1

Moreno, M. A., Suthamjariya, N., & Selkie, E. (2018). Stakeholder perceptions of cyberbullying cases: Application of the uniform definition of bullying. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 62 (4), 444–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.289

Musu, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2019). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2018 (NCES 2019–047/NCJ 252571). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019047.pdf

Nelson, H. J., Burns, S. K., Kendall, G. E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2019). Preadolescent children's perception of power imbalance in bullying: A thematic analysis. PLoS One, 14 (3), e0211124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211124

Nickerson, A. B. (2019). Preventing and intervening with bullying in schools: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health, 11 (4), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9221-8

Nickerson, A. B., Fredrick, S. S., Allen, K. P., & Jenkins, L. N. (2019). Social emotional learning (SEL) practices in schools: Effects on perceptions of bullying victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 73 , 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.03.002

Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2016). KiVa anti-bullying program in Italy: Evidence of effectiveness in a randomized control trial. Prevention Science, 17 (8), 1012–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0690-z

Office of the Surgeon General (2023). Social media and youth mental health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-media-advisory.pdf

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do . Blackwell Publishing.

Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2018). Some problems with cyberbullying research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19 , 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.012

Peeters, M., Cillessen, A. H., & Scholte, R. H. (2010). Clueless or powerful? Identifying subtypes of bullies in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39 (9), 1041–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9478-9

Pepler, D. J. (2006). Bullying interventions: A binocular perspective. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15 (1), 16–20.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pepler, D., Jiang, D., Craig, W., & Connolly, J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79 (2), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x

Perren, S., & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2012). Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescence: Differential roles of moral disengagement, moral emotions, and moral values. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9 (2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2011.643168

Petrosino, A., Guckenburg, S., DeVoe, J., & Hanson, T. (2010). What characteristics of bullying, bullying victims, and schools are associated with increased reporting of bullying to school officials? (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2010–No. 092). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast and Islands. August 2010. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/northeast/pdf/REL_2010092_sum.pdf

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41 (1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., Grotpeter, J. K., Ingram, K., Michaelson, L., Spinney, E., Valido, A., Sheikh, A. E., Torgal, C., & Robinson, L. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to decrease cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Prevention Science, 23 (3), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01259-y

Raman, S., Muhammad, T., Goldhagen, J., Seth, R., Kadir, A., Bennett, S., D'Annunzio, D., Spencer, N. J., Bhutta, Z. A., & Gerbaka, B. (2021). Ending violence against children: What can global agencies do in partnership? Child Abuse & Neglect, 119 (Pt 1), 104733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104733

Rettew, D. C., & Pawlowski, S. (2016). Bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25 (2), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2015.12.002

Rideout, V. (2017). The Common-sense census: Media use by tweens and teens . Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/census_researchreport.pdf .

Rideout, V., & Robb, M. B. (2019). Social media, social life: Teens reveal their experiences . Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2019-census-8-to-18-key-findings-updated.pdf .

Rodkin, P. C., Espelage, D. L., & Hanish, L. D. (2015). A relational framework for understanding bullying: Developmental antecedents and outcomes. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038658

Ross, S. W., Horner, R. H., & Higbee, T. (2009). Bully prevention in positive behavior support. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42 (4), 747–759. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.42-747

Sabia, J. J., & Bass, B. (2017). Do anti-bullying laws work? New evidence on school safety and youth violence. Journal of Population Economics, 30 (2), 473–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0622-z

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15 (2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Singham, T., Viding, E., Schoeler, T., Arseneault, L., Ronald, A., Cecil, C. M., McCrory, E., Rijsdijk, F., & Pingault, J. B. (2017). Concurrent and longitudinal contribution of exposure to bullying in childhood to mental health: The role of vulnerability and resilience. JAMA Psychiatry, 74 (11), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2678

Smith, P. K., Singer, M., Hoel, H., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). Victimization in the school and the workplace: Are there any links? British Journal of Psychology, 94 (2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603321661868

Smith, J. D., Schneider, B., Smith, P. K., & Ananiadou, K. (2004). The effectiveness of whole-school anti-bullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review, 33 (4), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2004.12086267

Solberg, M., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus/bully victim questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29 (3), 239–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047

Srabstein, J. C., & Leventhal, B. L. (2010). Prevention of bullying-related morbidity and mortality: A call for public health policies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88 (6), 403. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.10.077123

Stopbullying.gov. (2021). Laws, policies, and regulations . https://www.stopbullying.gov/resources/laws

Sullivan, T. N., Farrell, A. D., Sutherland, K. S., Behrhorst, K. L., Garthe, R. C., & Greene, A. (2023). Evaluation of the Olweus bullying prevention program in US urban middle schools using a multiple baseline experimental design. Prevention Science, 22 (8), 1134–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01244-5

Swearer, S. M., Wang, C., Maag, J. W., Siebecker, A. B., & Frerichs, L. J. (2012). Understanding the bullying dynamic among students in special and general education. Journal of School Psychology, 50 (4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2012.04.001

Thornberg, R. (2015). The social dynamics of school bullying: The necessary dialogue between the blind men around the elephant and the possible meeting point at the social ecological square. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy and Politics, 3 (1), 161–203. https://doi.org/10.3384/confero.2001-4562.1506245

Tiiri, E., Luntamo, T., Mishina, K., Sillanmäki, L., Brunstein Klomek, A., & Sourander, A. (2020). Did bullying victimization decrease after nationwide school-based antibullying program? A time-trend study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59 (4), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.03.023

Troop-Gordon, W. (2017). Peer victimization in adolescence: The nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. Journal of Adolescence, 55 , 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., & Lösel, F. (2012). School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17 (5), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.05.002

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., Crago, R. V., & Theodorakis, N. (2016). School bullying and drug use later in life: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 31 (1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000120

Vaillancourt, T., McDougall, P., Hymel, S., Krygsman, A., Miller, J., Stiver, K., & Davis, C. (2008). Bullying: Are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32 (6), 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408095553

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34 (4), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001

Waasdorp, T. E., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: A randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166 (2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.755

Waseem, M., Paul, A., Schwartz, G., Pauzé, D., Eakin, P., Barata, I., Holtzman, D., Benjamin, L. S., Wright, J. L., Nickerson, A. B., & Joseph, M. (2017). Role of pediatric emergency physicians in identifying bullying. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 52 (2), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.07.107

Williford, A., Boulton, A., Noland, B., Little, T. D., Kärnä, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2012). Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on adolescents’ depression, anxiety, and perception of peers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40 , 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9562-y

Winding, T. N., Skouenborg, L. A., Mortensen, V. L., & Anderson, J. H. (2020). Is bullying in adolescence associated with the development of depressive symptoms in adulthood?: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Psychology, 8 , 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00491-5

Xu, M., Macrynikola, N., Waseem, M., & Miranda, R. (2020). Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: Review and implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50 , 101340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340

Ybarra, M. L., Boyd, D., Korchmaros, J. D., & Oppenheim, J. K. (2012). Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51 (1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.031

Yeager, D. S., Fong, C., Lee, H., & Espelage, D. (2015). Declines in efficacy or anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: Theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37 (1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005

Zhang, Q., Cao, Y., & Tian, J. (2021). Effects of violent video games on aggressive cognition and aggressive behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 24 (1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-139260/v1

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Lincoln Medical Center, 234 East 149th Street, Bronx, NY, 10451, USA

Muhammad Waseem

Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA

New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA

Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse Prevention, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, 428 Baldy Hall, Buffalo, NY, 14260-1000, USA

Amanda B. Nickerson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Muhammad Waseem .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

N/A (It is a literature review).

Informed consent

N/A (it does not involve any patient involvement).

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Waseem, M., Nickerson, A.B. Bullying: issues and challenges in prevention and intervention. Curr Psychol 43 , 9270–9279 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05083-1

Download citation

Accepted : 02 August 2023

Published : 12 August 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05083-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intervention

- Cyberbullying

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Bullying: What We Know Based On 40 Years of Research

APA journal examines science aimed at understanding causes, prevention

WASHINGTON — A special issue of American Psychologist ® provides a comprehensive review of over 40 years of research on bullying among school age youth, documenting the current understanding of the complexity of the issue and suggesting directions for future research.

“The lore of bullies has long permeated literature and popular culture. Yet bullying as a distinct form of interpersonal aggression was not systematically studied until the 1970s. Attention to the topic has since grown exponentially,” said Shelley Hymel, PhD, professor of human development, learning and culture at the University of British Columbia, a scholarly lead on the special issue along with Susan M. Swearer, PhD, professor of school psychology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “Inspired by the 2011 U.S. White House Conference on Bullying Prevention, this collection of articles documents current understanding of school bullying.”

The special issue consists of an introductory overview (PDF, 90KB) by Hymel and Swearer, co-directors of the Bullying Research Network, and five articles on various research areas of bullying including the long-term effects of bullying into adulthood, reasons children bully others, the effects of anti-bullying laws and ways of translating research into anti-bullying practice.

Articles in the issue:

Long-Term Adult Outcomes of Peer Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: Pathways to Adjustment and Maladjustment (PDF, 122KB) by Patricia McDougall, PhD, University of Saskatchewan, and Tracy Vaillancourt, PhD, University of Ottawa.

The experience of being bullied is painful and difficult. Its negative impact — on academic functioning, physical and mental health, social relationships and self-perceptions — can endure across the school years. But not every victimized child develops into a maladjusted adult. In this article, the authors provide an overview of the negative outcomes experienced by victims through childhood and adolescence and sometimes into adulthood. They then analyze findings from prospective studies to identify factors that lead to different outcomes in different people, including in their biology, timing, support systems and self-perception.

Patricia McDougall can be contacted by email or by phone at (306) 966-6203.

A Relational Framework for Understanding Bullying: Developmental Antecedents and Outcomes (PDF, 151KB) by Philip Rodkin, PhD, and Dorothy Espelage, PhD, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and Laura Hanish, PhD, Arizona State University.

How do you distinguish bullying from aggression in general? In this review, the authors describe bullying from a relationship perspective. In order for bullying to be distinguished from other forms of aggression, a relationship must exist between the bully and the victim, there must be an imbalance of power between the two and it must take place over a period of time. “Bullying is perpetrated within a relationship, albeit a coercive, unequal, asymmetric relationship characterized by aggression,” wrote the authors. Within that perspective, the image of bullies as socially incompetent youth who rely on physical coercion to resolve conflicts is nothing more than a stereotype. While this type of “bully-victim” does exist and is primarily male, the authors describe another type of bully who is more socially integrated and has surprisingly high levels of popularity among his or her peers. As for the gender of victims, bullying is just as likely to occur between boys and girls as it is to occur in same-gender groups.

Dorothy Espelage can be contacted by email or by phone at (217) 333-9139.

Translating Research to Practice in Bullying Prevention (PDF, 157KB) by Catherine Bradshaw, PhD, University of Virginia.

This paper reviews the research and related science to develop a set of recommendations for effective bullying prevention programs. From mixed findings on existing programs, the author identifies core elements of promising prevention approaches (e.g., close playground supervision, family involvement, and consistent classroom management strategies) and recommends a three-tiered public health approach that can attend to students at all risk levels. However, the author notes, prevention efforts must be sustained and integrated to effect change.

Catherine Bradshaw can be contacted by email or by phone at (434) 924-8121.

Law and Policy on the Concept of Bullying at School (PDF, 126KB) by Dewey Cornell, PhD, University of Virginia, and Susan Limber, PhD, Clemson University.

Since the shooting at Columbine High School in 1999, all states but one have passed anti-bullying laws, and multiple court decisions have made schools more accountable for peer victimization. Unfortunately, current legal and policy approaches, which are strongly rooted in laws regarding harassment and discrimination, do not provide adequate protection for all bullied students. In this article, the authors provide a review of the legal framework underpinning many anti-bullying laws and make recommendations on best practices for legislation and school policies to effectively address the problem of bullying.

Dewey Cornell can be contacted by email or by phone at (434) 924-0793.

Understanding the Psychology of Bullying: Moving Toward a Social-Ecological Diathesis-Stress Model by Susan Swearer, PhD, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and Shelley Hymel, PhD, University of British Columbia.

Children’s involvement in bullying varies across roles and over time. A student may be victimized by classmates but bully a sibling at home. Bullying is a complex form of interpersonal aggression that can be both a one-on-one process and a group phenomenon. It negatively affects not only the victim, but the bully and witnesses as well. In this paper, the authors suggest an integrated model for examining bullying and victimization that recognizes the complex and dynamic nature of bullying across multiple settings over time.

Susan Swearer can be contacted by email or by phone at (402) 472-1741. Shelley Hymel can be contacted by email or by phone at (604) 822-6022.

Copies of articles are also available from APA Public Affairs , (202) 336-5700.

The American Psychological Association, in Washington, D.C., is the largest scientific and professional organization representing psychology in the United States. APA's membership includes more than 122,500 researchers, educators, clinicians, consultants and students. Through its divisions in 54 subfields of psychology and affiliations with 60 state, territorial and Canadian provincial associations, APA works to advance the creation, communication and application of psychological knowledge to benefit society and improve people's lives.

Jim Sliwa (202) 336-5707

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Understanding alternative bullying perspectives through research engagement with young people.

- School of Education and Social Care, Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford, United Kingdom

Bullying research has traditionally been dominated by largescale cohort studies focusing on the personality traits of bullies and victims. These studies focus on bullying prevalence, risk and protective factors, and negative outcomes. A limitation of this approach is that it does not explain why bullying happens. Qualitative research can help shed light on these factors. This paper discusses the findings from four mainly qualitative research projects including a systematic review and three empirical studies involving young people to various degrees within the research process as respondents, co-researchers and commissioners of research. Much quantitative research suggests that young people are a homogenous group and through the use of surveys and other large scale methods, generalizations can be drawn about how bullying is understood and how it can be dealt with. Findings from the studies presented in this paper, add to our understanding that young people appear particularly concerned about the role of wider contextual and relational factors in deciding if bullying has happened. These studies underscore the relational aspects of definitions of bullying and, how the dynamics of young people’s friendships can shift what is understood as bullying or not. Moreover, to appreciate the relational and social contexts underpinning bullying behaviors, adults and young people need to work together on bullying agendas and engage with multiple definitions, effects and forms of support. Qualitative methodologies, in particular participatory research opens up the complexities of young lives and enables these insights to come to the fore. Through this approach, effective supports can be designed based on what young people want and need rather than those interpreted as supportive through adult understanding.

Introduction

Research on school bullying has developed rapidly since the 1970s. Originating in social and psychological research in Norway, Sweden, and Finland, this body of research largely focusses on individualized personality traits of perpetrators and victims ( Olweus, 1995 ). Global interest in this phenomenon subsequently spread and bullying research began in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States ( Griffin and Gross, 2004 ). Usually quantitative in nature, many studies examine bullying prevalence, risk and protective factors, and negative outcomes ( Patton et al., 2017 ). Whilst quantitative research collates key demographic information to show variations in bullying behaviors and tendencies, this dominant bullying literature fails to explain why bullying happens. Nor does it attempt to understand the wider social contexts in which bullying occurs. Qualitative research on the other hand, in particular participatory research, can help shed light on these factors by highlighting the complexities of the contextual and relational aspects of bullying and the particular challenges associated with addressing it. Patton et al. (2017) in their systematic review of qualitative methods used in bullying research, found that the use of such methods can enhance academic and practitioner understanding of bullying.

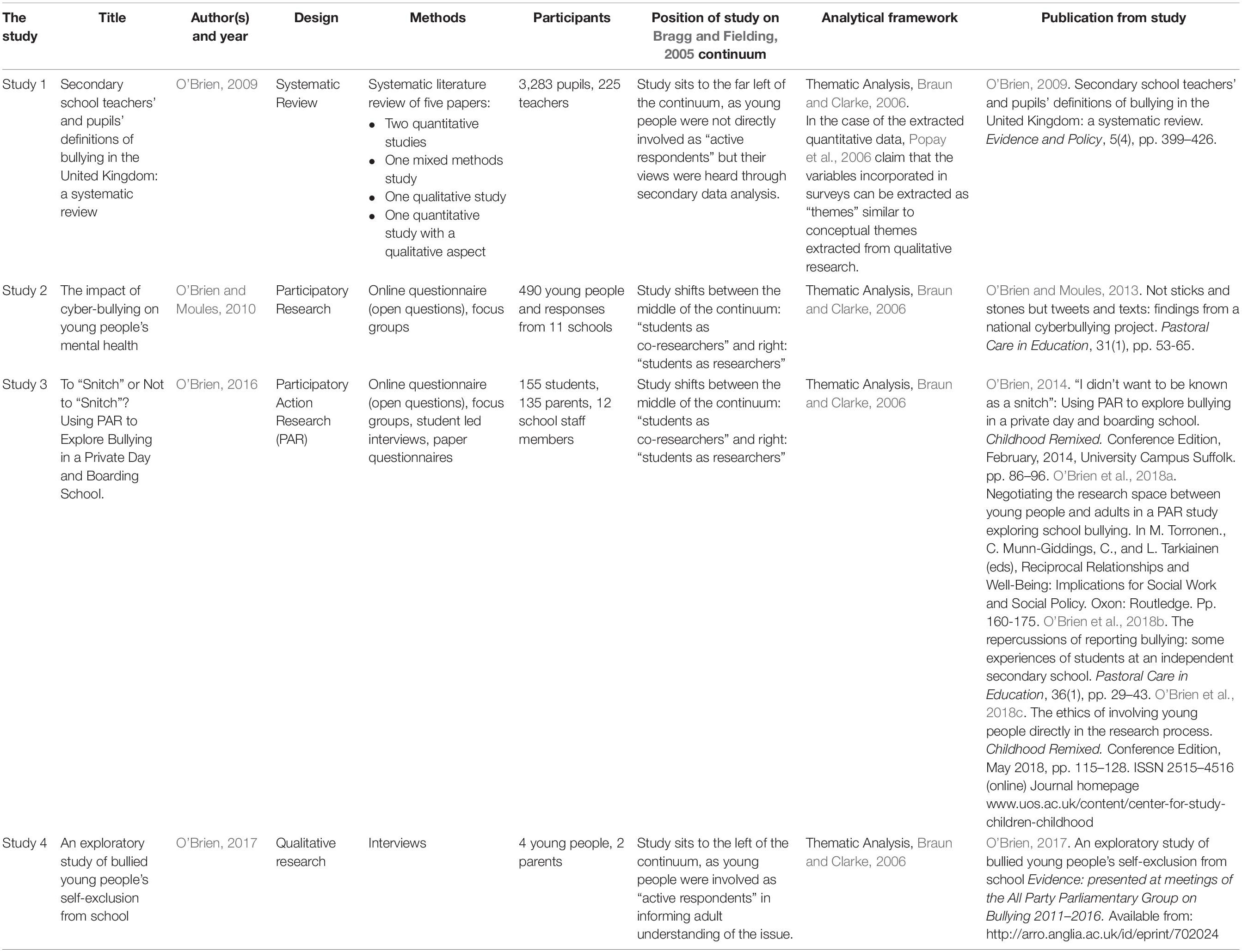

In this paper, I draw on four bullying studies; one systematic review of both quantitative and qualitative research ( O’Brien, 2009 ) and three empirical qualitative studies ( O’Brien and Moules, 2010 ; O’Brien, 2016 , 2017 ) (see Table 1 below). I discuss how participatory research methodologies, to varying degrees, were used to facilitate bullying knowledge production among teams of young people and adults. Young people in these presented studies were consequently involved in the research process along a continuum of involvement ( Bragg and Fielding, 2005 ). To the far left of the continuum, young people involved in research are referred to as “active respondents” and their data informs teacher practice. To the middle of the continuum sit “students as co-researchers” who work with teachers to explore an issue which has been identified by that teacher. Finally to the right, sit “students as researchers” who conduct their own research with support from teachers. Moving from left to right of the continuum shows a shift in power dynamics between young people and adults where a partnership develops. Young people are therefore recognized as equal to adults in terms of what they can bring to the project from their own unique perspective, that of being a young person now.

Table 1. The studies.

In this paper, I advocate for the active involvement of young people in the research process in order to enhance bullying knowledge. Traditional quantitative studies have a tendency to homogenize young people by suggesting similarity in thinking about what constitutes bullying. However, qualitative studies have demonstrated that regardless of variables, young people understand bullying in different ways so there is a need for further research that starts from these perspectives and focusses on issues that young people deem important. Consequently, participatory research allows for the stories of the collective to emerge without losing the stories of the individual, a task not enabled through quantitative approaches.

What Is Bullying?

Researching school bullying has been problematic and is partly related to the difficulty in defining it ( Espelage, 2018 ). Broadly speaking, bullying is recognized as aggressive, repeated, intentional behavior involving an imbalance of power aimed toward an individual or group of individuals who cannot easily defend themselves ( Vaillancourt et al., 2008 ). In more recent times, “traditional” bullying behaviors have been extended to include cyber-bullying, involving the use of the internet and mobile-phones ( Espelage, 2018 ). Disagreements have been noted in the literature about how bullying is defined by researchers linked to subject discipline and culture. Some researchers for example, disagree about the inclusion or not of repetition in definitions ( Griffin and Gross, 2004 ) and these disagreements have had an impact on interpreting findings and prevalence rates. However, evidence further suggests that young people also view bullying in different ways ( Guerin and Hennessy, 2002 ; Cuadrado-Gordillo, 2012 ; Eriksen, 2018 ). Vaillancourt et al. (2008) explored differences between researchers and young people’s definitions of bullying, and found that children’s definitions were usually spontaneous, and did not always encompass the elements of repetition, power imbalance and intent. They concluded, that children need to be provided with a bullying definition so similarities and comparisons can be drawn. In contrast, Huang and Cornell (2015) found no evidence that the inclusion of a definition effected prevalence rates. Their findings, they suggest, indicate that young people use their own perceptions of bullying when answering self-report questionnaires and they are not influenced by an imposed definition.