Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

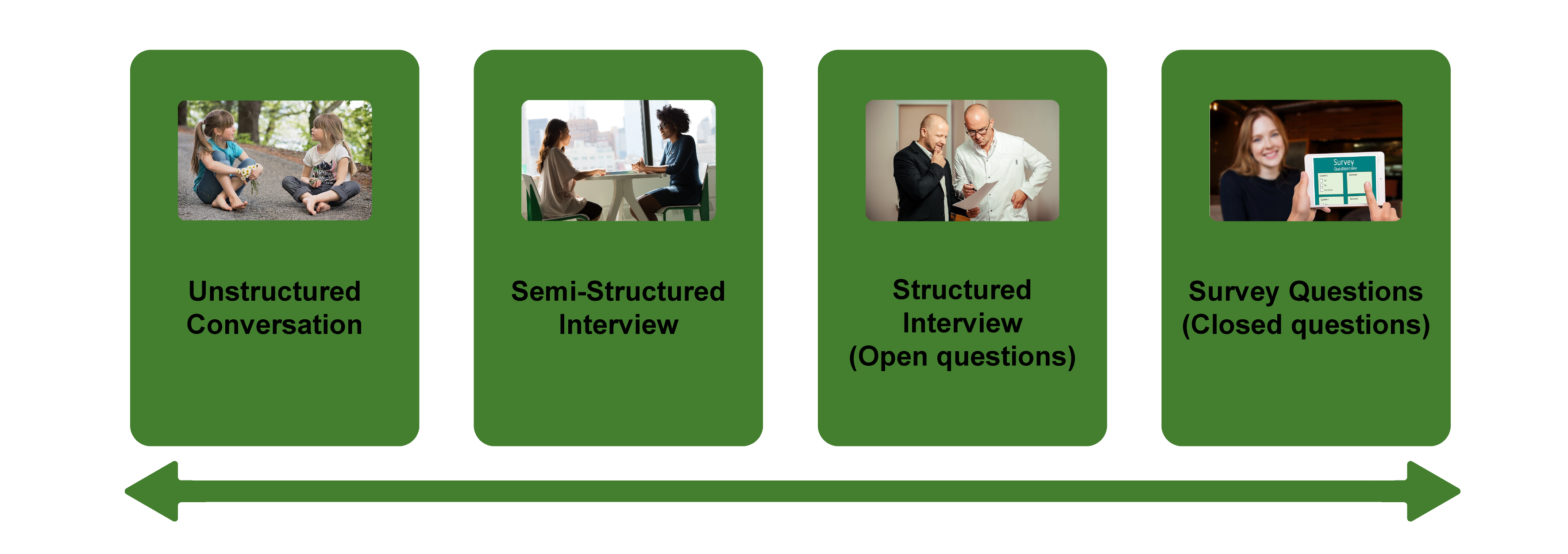

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Qualitative study design: Interviews

- Qualitative study design

- Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Interviews are intended to find out the experiences, understandings, opinions, or motivations of participants. The relationship between the interviewer and interviewee is crucial to the success of the research interview; the interviewer builds an environment of trust with the interviewee/s, guiding the interviewee/s through a set of topics or questions to be discussed in depth.

Interviews are the most commonly used qualitative data gathering technique and are used with grounded theory, focus groups, and case studies.

- Interviews are purposive conversations between the researcher and the interviewee, either alone or as part of a group

- Interviews can be face to face, via telecommunications (Skype, Facetime, or phone), or via email (internet or email interview)

- The length of an interview varies. They may be anywhere from thirty minutes to several hours in length, depending on your research approach

- Structured interviews use a set list of questions which need to be asked in order, increasing the reliability and credibility of the data but decreasing responsiveness to interviewee/s. Structured interviews are like a verbal survey

- Unstructured interviews are where the interviewer has a set list of topics to address but no predetermined questions. This increases the flexibility of the interview but decreases the reliability of the data. Unstructured interviews may be used in long-term field observation research

- Semi-structured interviews are the middle ground. Semi-structured interviews require the interviewer to have a list of questions and topics pre-prepared, which can be asked in different ways with different interviewee/s. Semi-structured interviews increase the flexibility and the responsiveness of the interview while keeping the interview on track, increasing the reliability and credibility of the data. Semi-structured interviews are one of the most common interview techniques.

- Flexible – probing questions can be asked, and the order of questions changed, depending on the participant and how structured or unstructured the interview is

- Quick way to collect data

- Familiarity – most interviewees are familiar with the concept of an interview and are comfortable with this research approach

Limitations

- Not all participants are equally articulate or perceptive

- Questions must be worded carefully to reduce response bias

- Transcription of interviews can be time and labour intensive

Example questions

- What are the experiences of midwives in providing care to high-risk mothers, where there is a history of drug or alcohol use?

Example studies

Sandelin, A., Kalman, S., Gustafsson, B. (2019). Prerequisites for safe intraoperative nursing care and teamwork – operating theatre nurses’ perspectives: a qualitative interview study, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28, 2635-2643. Doi: 10.1111/jocn.14850

Babbie, E. (2008). The basics of social research (4th ed). Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth

Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (5th ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE

Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. Journal of basic and clinical pharmacy, 5(4), 87-88. doi:10.4103/0976-0105.141942

Lindlof, T. & Taylor, B. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE .

- << Previous: Surveys & questionnaires

- Next: Sampling >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 11:46 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Qualitative Research Design: Start

Qualitative Research Design

What is Qualitative research design?

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much . It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research, which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Research Paradigms

- Positivist versus Post-Positivist

- Social Constructivist (this paradigm/ideology mostly birth qualitative studies)

Events Relating to the Qualitative Research and Community Engagement Workshops @ CMU Libraries

CMU Libraries is committed to helping members of our community become data experts. To that end, CMU is offering public facing workshops that discuss Qualitative Research, Coding, and Community Engagement best practices.

The following workshops are a part of a broader series on using data. Please follow the links to register for the events.

Qualitative Coding

Using Community Data to improve Outcome (Grant Writing)

Survey Design

Upcoming Event: March 21st, 2024 (12:00pm -1:00 pm)

Community Engagement and Collaboration Event

Join us for an event to improve, build on and expand the connections between Carnegie Mellon University resources and the Pittsburgh community. CMU resources such as the Libraries and Sustainability Initiative can be leveraged by users not affiliated with the university, but barriers can prevent them from fully engaging.

The conversation features representatives from CMU departments and local organizations about the community engagement efforts currently underway at CMU and opportunities to improve upon them. Speakers will highlight current and ongoing projects and share resources to support future collaboration.

Event Moderators:

Taiwo Lasisi, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in Community Data Literacy, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Emma Slayton, Data Curation, Visualization, & GIS Specialist, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Nicky Agate , Associate Dean for Academic Engagement, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Chelsea Cohen , The University’s Executive fellow for community engagement, Carnegie Mellon University

Sarah Ceurvorst , Academic Pathways Manager, Program Director, LEAP (Leadership, Excellence, Access, Persistence) Carnegie Mellon University

Julia Poeppibg , Associate Director of Partnership Development, Information Systems, Carnegie Mellon University

Scott Wolovich , Director of New Sun Rising, Pittsburgh

Additional workshops and events will be forthcoming. Watch this space for updates.

Workshop Organizer

Qualitative Research Methods

What are Qualitative Research methods?

Qualitative research adopts numerous methods or techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one-on-one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be participant observers to share the experiences of the subject or non-participant or detached observers.

What constitutes a good research question? Does the question drive research design choices?

According to Doody and Bailey (2014);

We can only develop a good research question by consulting relevant literature, colleagues, and supervisors experienced in the area of research. (inductive interactions).

Helps to have a directed research aim and objective.

Researchers should not be “ research trendy” and have enough evidence. This is why research objectives are important. It helps to take time, and resources into consideration.

Research questions can be developed from theoretical knowledge, previous research or experience, or a practical need at work (Parahoo 2014). They have numerous roles, such as identifying the importance of the research and providing clarity of purpose for the research, in terms of what the research intends to achieve in the end.

Qualitative Research Questions

What constitutes a good Qualitative research question?

A good qualitative question answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions and behavior.

Examples of good Qualitative Research Questions:

What are people's thoughts on the new library?

How does it feel to be a first-generation student attending college?

Difference example (between Qualitative and Quantitative research questions):

How many college students signed up for the new semester? (Quan)

How do college students feel about the new semester? What are their experiences so far? (Qual)

- Qualitative Research Design Workshop Powerpoint

Foley G, Timonen V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015 Aug;50(4):1195-210. [ PMC free article: PMC4545354 ] [ PubMed: 25523315 ]

Devers KJ. How will we know "good" qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;34(5 Pt 2):1153-88. [ PMC free article: PMC1089058 ] [ PubMed: 10591278 ]

Huston P, Rowan M. Qualitative studies. Their role in medical research. Can Fam Physician. 1998 Nov;44:2453-8. [ PMC free article: PMC2277956 ] [ PubMed: 9839063 ]

Corner EJ, Murray EJ, Brett SJ. Qualitative, grounded theory exploration of patients' experience of early mobilisation, rehabilitation and recovery after critical illness. BMJ Open. 2019 Feb 24;9(2):e026348. [ PMC free article: PMC6443050 ] [ PubMed: 30804034 ]

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018 Dec;24(1):9-18. [ PMC free article: PMC5774281 ] [ PubMed: 29199486 ]

Houghton C, Murphy K, Meehan B, Thomas J, Brooker D, Casey D. From screening to synthesis: using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2017 Mar;26(5-6):873-881. [ PubMed: 27324875 ]

Soratto J, Pires DEP, Friese S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: Potentialities for researchs in health. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(3):e20190250. [ PubMed: 32321144 ]

Zamawe FC. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med J. 2015 Mar;27(1):13-5. [ PMC free article: PMC4478399 ] [ PubMed: 26137192 ]

Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018 Dec;24(1):120-124. [ PMC free article: PMC8816392 ] [ PubMed: 29202616 ]

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 1-440.

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245-51. [ PubMed: 24979285 ]

Palermo C, King O, Brock T, Brown T, Crampton P, Hall H, Macaulay J, Morphet J, Mundy M, Oliaro L, Paynter S, Williams B, Wright C, E Rees C. Setting priorities for health education research: A mixed methods study. Med Teach. 2019 Sep;41(9):1029-1038. [ PubMed: 31141390 ]

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:25 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/c.php?g=1346006

Qualitative Research 101: Interviewing

5 Common Mistakes To Avoid When Undertaking Interviews

By: David Phair (PhD) and Kerryn Warren (PhD) | March 2022

Undertaking interviews is potentially the most important step in the qualitative research process. If you don’t collect useful, useable data in your interviews, you’ll struggle through the rest of your dissertation or thesis. Having helped numerous students with their research over the years, we’ve noticed some common interviewing mistakes that first-time researchers make. In this post, we’ll discuss five costly interview-related mistakes and outline useful strategies to avoid making these.

Overview: 5 Interviewing Mistakes

- Not having a clear interview strategy /plan

- Not having good interview techniques /skills

- Not securing a suitable location and equipment

- Not having a basic risk management plan

- Not keeping your “ golden thread ” front of mind

1. Not having a clear interview strategy

The first common mistake that we’ll look at is that of starting the interviewing process without having first come up with a clear interview strategy or plan of action. While it’s natural to be keen to get started engaging with your interviewees, a lack of planning can result in a mess of data and inconsistency between interviews.

There are several design choices to decide on and plan for before you start interviewing anyone. Some of the most important questions you need to ask yourself before conducting interviews include:

- What are the guiding research aims and research questions of my study?

- Will I use a structured, semi-structured or unstructured interview approach?

- How will I record the interviews (audio or video)?

- Who will be interviewed and by whom ?

- What ethics and data law considerations do I need to adhere to?

- How will I analyze my data?

Let’s take a quick look at some of these.

The core objective of the interviewing process is to generate useful data that will help you address your overall research aims. Therefore, your interviews need to be conducted in a way that directly links to your research aims, objectives and research questions (i.e. your “golden thread”). This means that you need to carefully consider the questions you’ll ask to ensure that they align with and feed into your golden thread. If any question doesn’t align with this, you may want to consider scrapping it.

Another important design choice is whether you’ll use an unstructured, semi-structured or structured interview approach . For semi-structured interviews, you will have a list of questions that you plan to ask and these questions will be open-ended in nature. You’ll also allow the discussion to digress from the core question set if something interesting comes up. This means that the type of information generated might differ a fair amount between interviews.

Contrasted to this, a structured approach to interviews is more rigid, where a specific set of closed questions is developed and asked for each interviewee in exactly the same order. Closed questions have a limited set of answers, that are often single-word answers. Therefore, you need to think about what you’re trying to achieve with your research project (i.e. your research aims) and decided on which approach would be best suited in your case.

It is also important to plan ahead with regards to who will be interviewed and how. You need to think about how you will approach the possible interviewees to get their cooperation, who will conduct the interviews, when to conduct the interviews and how to record the interviews. For each of these decisions, it’s also essential to make sure that all ethical considerations and data protection laws are taken into account.

Finally, you should think through how you plan to analyze the data (i.e., your qualitative analysis method) generated by the interviews. Different types of analysis rely on different types of data, so you need to ensure you’re asking the right types of questions and correctly guiding your respondents.

Simply put, you need to have a plan of action regarding the specifics of your interview approach before you start collecting data. If not, you’ll end up drifting in your approach from interview to interview, which will result in inconsistent, unusable data.

2. Not having good interview technique

While you’re generally not expected to become you to be an expert interviewer for a dissertation or thesis, it is important to practice good interview technique and develop basic interviewing skills .

Let’s go through some basics that will help the process along.

Firstly, before the interview , make sure you know your interview questions well and have a clear idea of what you want from the interview. Naturally, the specificity of your questions will depend on whether you’re taking a structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach, but you still need a consistent starting point . Ideally, you should develop an interview guide beforehand (more on this later) that details your core question and links these to the research aims, objectives and research questions.

Before you undertake any interviews, it’s a good idea to do a few mock interviews with friends or family members. This will help you get comfortable with the interviewer role, prepare for potentially unexpected answers and give you a good idea of how long the interview will take to conduct. In the interviewing process, you’re likely to encounter two kinds of challenging interviewees ; the two-word respondent and the respondent who meanders and babbles. Therefore, you should prepare yourself for both and come up with a plan to respond to each in a way that will allow the interview to continue productively.

To begin the formal interview , provide the person you are interviewing with an overview of your research. This will help to calm their nerves (and yours) and contextualize the interaction. Ultimately, you want the interviewee to feel comfortable and be willing to be open and honest with you, so it’s useful to start in a more casual, relaxed fashion and allow them to ask any questions they may have. From there, you can ease them into the rest of the questions.

As the interview progresses , avoid asking leading questions (i.e., questions that assume something about the interviewee or their response). Make sure that you speak clearly and slowly , using plain language and being ready to paraphrase questions if the person you are interviewing misunderstands. Be particularly careful with interviewing English second language speakers to ensure that you’re both on the same page.

Engage with the interviewee by listening to them carefully and acknowledging that you are listening to them by smiling or nodding. Show them that you’re interested in what they’re saying and thank them for their openness as appropriate. This will also encourage your interviewee to respond openly.

Need a helping hand?

3. Not securing a suitable location and quality equipment

Where you conduct your interviews and the equipment you use to record them both play an important role in how the process unfolds. Therefore, you need to think carefully about each of these variables before you start interviewing.

Poor location: A bad location can result in the quality of your interviews being compromised, interrupted, or cancelled. If you are conducting physical interviews, you’ll need a location that is quiet, safe, and welcoming . It’s very important that your location of choice is not prone to interruptions (the workplace office is generally problematic, for example) and has suitable facilities (such as water, a bathroom, and snacks).

If you are conducting online interviews , you need to consider a few other factors. Importantly, you need to make sure that both you and your respondent have access to a good, stable internet connection and electricity. Always check before the time that both of you know how to use the relevant software and it’s accessible (sometimes meeting platforms are blocked by workplace policies or firewalls). It’s also good to have alternatives in place (such as WhatsApp, Zoom, or Teams) to cater for these types of issues.

Poor equipment: Using poor-quality recording equipment or using equipment incorrectly means that you will have trouble transcribing, coding, and analyzing your interviews. This can be a major issue , as some of your interview data may go completely to waste if not recorded well. So, make sure that you use good-quality recording equipment and that you know how to use it correctly.

To avoid issues, you should always conduct test recordings before every interview to ensure that you can use the relevant equipment properly. It’s also a good idea to spot check each recording afterwards, just to make sure it was recorded as planned. If your equipment uses batteries, be sure to always carry a spare set.

4. Not having a basic risk management plan

Many possible issues can arise during the interview process. Not planning for these issues can mean that you are left with compromised data that might not be useful to you. Therefore, it’s important to map out some sort of risk management plan ahead of time, considering the potential risks, how you’ll minimize their probability and how you’ll manage them if they materialize.

Common potential issues related to the actual interview include cancellations (people pulling out), delays (such as getting stuck in traffic), language and accent differences (especially in the case of poor internet connections), issues with internet connections and power supply. Other issues can also occur in the interview itself. For example, the interviewee could drift off-topic, or you might encounter an interviewee who does not say much at all.

You can prepare for these potential issues by considering possible worst-case scenarios and preparing a response for each scenario. For instance, it is important to plan a backup date just in case your interviewee cannot make it to the first meeting you scheduled with them. It’s also a good idea to factor in a 30-minute gap between your interviews for the instances where someone might be late, or an interview runs overtime for other reasons. Make sure that you also plan backup questions that could be used to bring a respondent back on topic if they start rambling, or questions to encourage those who are saying too little.

In general, it’s best practice to plan to conduct more interviews than you think you need (this is called oversampling ). Doing so will allow you some room for error if there are interviews that don’t go as planned, or if some interviewees withdraw. If you need 10 interviews, it is a good idea to plan for 15. Likely, a few will cancel , delay, or not produce useful data.

5. Not keeping your golden thread front of mind

We touched on this a little earlier, but it is a key point that should be central to your entire research process. You don’t want to end up with pages and pages of data after conducting your interviews and realize that it is not useful to your research aims . Your research aims, objectives and research questions – i.e., your golden thread – should influence every design decision and should guide the interview process at all times.

A useful way to avoid this mistake is by developing an interview guide before you begin interviewing your respondents. An interview guide is a document that contains all of your questions with notes on how each of the interview questions is linked to the research question(s) of your study. You can also include your research aims and objectives here for a more comprehensive linkage.

You can easily create an interview guide by drawing up a table with one column containing your core interview questions . Then add another column with your research questions , another with expectations that you may have in light of the relevant literature and another with backup or follow-up questions . As mentioned, you can also bring in your research aims and objectives to help you connect them all together. If you’d like, you can download a copy of our free interview guide here .

Recap: Qualitative Interview Mistakes

In this post, we’ve discussed 5 common costly mistakes that are easy to make in the process of planning and conducting qualitative interviews.

To recap, these include:

If you have any questions about these interviewing mistakes, drop a comment below. Alternatively, if you’re interested in getting 1-on-1 help with your thesis or dissertation , check out our dissertation coaching service or book a free initial consultation with one of our friendly Grad Coaches.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.4 Types of qualitative research designs

Learning objectives.

- Define focus groups and outline how they differ from one-on-one interviews

- Describe how to determine the best size for focus groups

- Identify the important considerations in focus group composition

- Discuss how to moderate focus groups

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of focus group methodology

- Describe case study research, ethnography, and phenomenology.

There are various types of approaches to qualitative research. This chapter presents information about focus groups, which are often used in social work research. It also introduces case studies, ethnography, and phenomenology.

Focus Groups

Focus groups resemble qualitative interviews in that a researcher may prepare a guide in advance and interact with participants by asking them questions. But anyone who has conducted both one-on-one interviews and focus groups knows that each is unique. In an interview, usually one member (the research participant) is most active while the other (the researcher) plays the role of listener, conversation guider, and question-asker. Focus groups , on the other hand, are planned discussions designed to elicit group interaction and “obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive, nonthreatening environment” (Krueger & Casey, 2000, p. 5). In focus groups, the researcher play a different role than in a one-on-one interview. The researcher’s aim is to get participants talking to each other, to observe interactions among participants, and moderate the discussion.

There are numerous examples of focus group research. In their 2008 study, for example, Amy Slater and Marika Tiggemann (2010) conducted six focus groups with 49 adolescent girls between the ages of 13 and 15 to learn more about girls’ attitudes towards’ participation in sports. In order to get focus group participants to speak with one another rather than with the group facilitator, the focus group interview guide contained just two questions: “Can you tell me some of the reasons that girls stop playing sports or other physical activities?” and “Why do you think girls don’t play as much sport/physical activity as boys?” In another focus group study, Virpi Ylanne and Angie Williams (2009) held nine focus group sessions with adults of different ages to gauge their perceptions of how older characters are represented in television commercials. Among other considerations, the researchers were interested in discovering how focus group participants position themselves and others in terms of age stereotypes and identities during the group discussion. In both examples, the researchers’ core interest in group interaction could not have been assessed had interviews been conducted on a one-on-one basis, making the focus group method an ideal choice.

Who should be in your focus group?

In some ways, focus groups require more planning than other qualitative methods of data collection, such as one-on-one interviews in which a researcher may be better able to the dialogue. Researchers must take care to form focus groups with members who will want to interact with one another and to control the timing of the event so that participants are not asked nor expected to stay for a longer time than they’ve agreed to participate. The researcher should also be prepared to inform focus group participants of their responsibility to maintain the confidentiality of what is said in the group. But while the researcher can and should encourage all focus group members to maintain confidentiality, she should also clarify to participants that the unique nature of the group setting prevents her from being able to promise that confidentiality will be maintained by other participants. Once focus group members leave the research setting, researchers cannot control what they say to other people.

Group size should be determined in part by the topic of the interview and your sense of the likelihood that participants will have much to say without much prompting. If the topic is one about which you think participants feel passionately and will have much to say, a group of 3–5 could make sense. Groups larger than that, especially for heated topics, can easily become unmanageable. Some researchers say that a group of about 6–10 participants is the ideal size for focus group research (Morgan, 1997); others recommend that groups should include 3–12 participants (Adler & Clark, 2008). The size of the focus group is ultimately the decision of the researcher. When forming groups and deciding how large or small to make them, take into consideration what you know about the topic and participants’ potential interest in, passion for, and feelings about the topic. Also consider your comfort level and experience in conducting focus groups. These factors will help you decide which size is right in your particular case.

It may seem counterintuitive, but in general, it is better to form focus groups consisting of participants who do not know one another than to create groups consisting of friends, relatives, or acquaintances (Agar & MacDonald, 1995). The reason is that group members who know each other may not share some taken-for-granted knowledge or assumptions. In research, it is precisely the taken-for-granted knowledge that is often of interest; thus, the focus group researcher should avoid setting up interactions where participants may be discouraged to question or raise issues that they take for granted. However, group members should not be so different from one another that participants will be unlikely to feel comfortable talking with one another.