What Is Reflective Writing?

Written by Scott Wilson

What is a reflection in writing? Reflection in writing is the act of including analysis or perspective on the text within the text itself. It’s a technique that is used to examine and interpret a passage or event described in a written work, and can be either a literary device or a tool for self-analysis.

Commonly found in academia, reflective writing is a genre of essay that prompts the writer to tell about a meaningful personal experience and reflect on the lesson learned or how it changed their perspective.

Though you will likely be tasked with exercises in reflection in academic setting, you will still be expected to take a creative approach in order to engage your readers.

Telling an engaging story is important here because your essay will be most effective when your readers find themselves leaning into the page, a physical posture of their interest.

Like a mirror, reflective writing allows the writer and readers to look back at the text and themselves to uncover deeper meaning. This allows perspectives or unexamined aspects of the text that might otherwise be hidden to be discovered and unpacked.

For the author, reflection is an exercise in self-analysis. While writing reflectively, the writer is expected to examine their own reactions and to document them as they are writing. In works of fiction, the reflection may be undertaken on behalf of a narrator and used to weave additional drama or meaning into a work.

Reflective writing describes the internal reactions of the writer and uses them to interpret the events described in the text.

Although reflection is a subjective exercise, it is often used to inject more objectivity into writing. When the writer engages in reflective writing, they can take a step back and deliver more context in the piece. This offers them a path not only to greater understanding of their own instincts and ideas, but also for the reader to better understand the work.

Creative Writing Degrees Use Reflection as a Tool for Study and Storytelling

Reflective writing is a popular academic tool in general. Students asked to summarize assignments, or keep journals, or describe their experiences are all engaging in reflective writing assignments. The use of reflection creates an academic focus and draws more learning from a given experience by giving students time to think about both the lessons and their connections.

You can expect to be assigned quite a few reflective writing assignments in the average creative writing degree program. Just as in other academic fields, reflection is of the tools that professors use to help students understand their own process and how to deconstruct their own work to improve it. But it’s also training for using reflection creatively, as a device to create new and deeper experiences for their readers.

Self-reflective narrators like Holden Caulfield and Mr. Stevens makes works like The Catcher in the Rye , and The Remains of the Day the classic works of literature they are. While reflection offers the individual writer a tool for investigating their process and methods, it can also become a tool for injecting life and drama into characters and plots.

Where would Samuel Beckett be without the use of reflection in writing? Likely waiting on a break that never comes.

In other cases, such as the works of Milan Kundera, feature entire reflective philosophical essays, both shaping the characters and offering more universal truths that are an essential aspect of the story.

Creative writing students explore both those uses of reflective writing in other literary works and ways to use reflection in their own work and study. Assignments may ask for self-reflective essays exploring your ideas and works, or for you to incorporate reflective writing into those pieces themselves. Either way, expert professors help shape your sense of reflection and its uses through the study of creative writing.

The Components of Reflective Writing

Formulaic writing is never encouraged in creative writing, especially at the college level, but there are some key parts to reflective writing that cannot be ignored. Think of these elements as ingredients for a recipe. Key components of a reflective essay are:

- Description: Give a detailed account of the experience you had. Remember to treat your reader as though they are beside you during the experience, relying on the five senses to make the retelling of the event as real as possible. Be mindful of inundating your reader with details, instead choosing to focus on the ones that would leave holes in your story if you kept them out.

- Interpretation: What’s your take on the episode? What did you learn? What does it mean? Is there something bigger than yourself that chose to teach you this lesson? Why you, why then, would you have learned the same lesson if it had happened at a different time in your life? All of these questions are starting points for reflection. The interpretation of the experience should be personal, almost to the point of feeling uncomfortable to write (respect your boundaries, but push them where you are able).

- Evaluation: This is almost an extension of interpretation. Here, you will focus on the value of the lesson learned. You’re not here to only tell a good story about a personal experience, you’re here to explain what you learned from it and to tell your reader why it was so valuable. Maybe you don’t know the answer yet and will arrive at the conclusion as you’re planning it out. Reflective writing will be entertaining and empowering for your reader, but it offers the opportunity to be cathartic for you. Don’t be afraid to dig deep.

- Planning: This is your opportunity to share what you are currently doing with the lesson learned or what you plan to do with it. Life lessons are inevitable, the meaning of them left to our own interpretation. Their power lies in how we reflect on them, how we use the experiences to change us in one way or another. There is potential here to let this part of the essay feel like a call to action for your reader, or to turn a little too sweet. If that’s your thing, go for it. But don’t feel pressured to turn this reflective essay into an after school special if what you experienced and what you learned ended on a sad or upsetting note. Be authentic in what you say and how you say it, whether it be happy, sad, or somewhere in between. The most important thing you can do in any of your writing is remain true to yourself.

Creative Writing: Reflective Journaling

by Melissa Donovan | Aug 5, 2021 | Creative Writing | 58 comments

Reflective journaling cultivates personal awareness.

A journal is a chronological log, and you can use a journal to log anything you want. Many professionals keep journals, including scientists and ship captains. Their journals are strictly for tracking their professional progress. Fitness enthusiasts keep diet and exercise journals. Artists use journals to chronicle their artistic expressions.

A writer’s journal can hold many things: thoughts, ideas, stories, poems, and notes. It can hold dreams and doodles, visions and meditations. Anything that pertains to your creative writing ideas and aspirations can find a home inside your journal.

Today let’s explore an intimate style of journaling, one in which we explore our innermost thoughts: reflective journaling.

Creative Writing Gets Personal

A diary is an account of one’s daily activities and experiences, and it’s one of the most popular types of journals.

A reflective journal is similar to a diary in that we document our experiences. However, reflective journaling goes deeper than diary writing; we use it to gain deeper understanding of our experiences rather than simply document them.

Reflective journaling is a form of creative writing that allows us to practice self-reflection, self-exploration, and self-improvement. Through reflective journaling, we gain greater understanding of ourselves through mindful observation, contemplation, and expression. As a result, we become more self-aware.

Reflective Journaling

We all have stories to tell. With reflective journaling, you write about your own life, but you’re not locked into daily chronicles that outline your activities or what you had for dinner. You might write about something that happened when you were a small child. You might even write about something that happened to someone else — something you witnessed or have thoughts about that you’d like to explore. Instead of recounting events, you might write exclusively about your inner experiences (thoughts and feelings). Reflective journaling often reveals tests we have endured and lessons we have learned.

The Art of Recalibration is a perfect example of reflective journaling in which stories about our lives are interwoven with our ideas about life itself.

Reflective journaling has other practical applications, too. Other forms of creative writing, such as poems and stories, can evolve from reflective journaling. And by striving to better understand ourselves, we may gain greater insight to others, which is highly valuable for fiction writers who need to create complex and realistic characters. The more deeply you understand people and the human condition, the more relatable your characters will be.

Do You Keep a Journal?

I guess I’m a journal slob because my journal has a little bit of everything in it: drawings, personal stories, rants, and reflections. It’s mostly full of free-writes and poetry. I realize that a lot of writers don’t bother with journals at all; they want to focus on the work they intend to publish. But I think journaling is healthy and contributes to a writer’s overall, ongoing growth.

I once read a comment on a blog by a writer who said she didn’t keep a journal because she couldn’t be bothered with writing down the events of each day; I found it curious that she had such a limited view of what a journal could hold. A journal doesn’t have to be any one thing. It can be a diary, but it can also be a place where we write down our ideas, plans, and observations. It can hold thoughts and feelings, but it can also be a place where we doodle and sketch stories and poems.

I’m curious about your journal. Do you keep one? What do you write in it? Is your journal private or public? Is it a spiral-bound notebook or a hardcover sketchbook? Does journaling inspire or inform your other creative writing projects? Have you ever tried reflective journaling? Tell us about your experiences by leaving a comment, and keep writing!

58 Comments

Hello. I keep writing refrective journal in Japanese. Now I’m trying to it in English. My dream is publish my book of English someday.Mamo

English takes a lot of practice, even for us native speakers, but with time, patience, and commitment, you can do it! Good luck.

Except for a few short months following an interstate move in December, I’ve faithfully kept a journal for 24 years. It’s reflective, it’s prayer, it’s story starts, character sketches, research and notes, it’s sometimes a rant, and usually how I see the world and my take on life. There’s just no way I function well without the journal. It fills some deep need for reflection and observation, but also the need to physically write, which is soothing and mind-ordering for me.

Twenty-four years is a long time! I’m impressed. Wait… that’s about how long I’ve kept a journal too! However, I haven’t been that faithful about it. There are weeks and months when I’m writing so much in other forms (blogging, fiction, etc.), that my journal gets neglected. I admire anyone who can stick with it over the long haul. No wonder you’re such a good writer!

It is wonderful to know that others in this world feel this way. Journaling does seem to help me fell aggreable about the events and happenings that were wholesomel and settle the ones that were not. I never thought of writing as soothing and wondered about dragon voice recognition to do the writing for me, but it just does not have the right feel. So I have stayed with hand writing to record my experiences in this fleeting life.

I have to confess I’m not a fan of voice recognition software except in cases where it helps people who are disabled and cannot type or write. The act of writing, of putting words down on paper or typing them onto a screen, is how we learn vocabulary, sentence structure, spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Otherwise, we’re just dictating, and that’s not writing.

Yes, I definitely believe that journaling is good for working out problems and celebrating life’s blessings.

Just today I was visiting with my pastor about this very topic. He wants to journal so he could revisit his thinking from time to time but is too impatient with handwriting. He uses Dragon Writing for dictating sermons, etc. and mentioned he might try it for journaling as well. Whatever works! I’m a big fan of handwriting and I occassionally type journal entries, print them and glue them into my journal. My journals include bits of everything – handwritten entries about my life, copies of special emails, images and articles I run across, quotes, creative sign copy I see while traveling, etc. etc. I tend to keep a separate travel journals and include bits of info from local newspapers, promotional brochures, etc. Other than travel, I like to have everything in one journal.

I’m a one-journal person, too, although I have notebooks for various purposes: one for my blog, one for my client work, and another for a fiction project. I don’t consider those journals. My journal is for ideas, personal thoughts, and poetry. Keep writing!

I was just thinking of putting everything in one journal. It drives me buggy to keep track of 20 different journals.(one for this,one for that)The reflective writing sounds helpful for a course I’ve been listening to on Podcast. Thanks!

I write essay and poetry, and I also keep a journal. I write stream of conscious sessions or dive into explanations of what I’m trying to say ina poem or essay. I also write book reviews and thoughts on what I’m reading. Rant too. All kinds of stuff.

I love stream-of-consciousness writing sessions too, although I usually call it freewriting. It’s the ultimate adventure in writing for me, and it generates so much great, raw, creative material. A really good session actually feels magical.

I’ve kept a journal since the early 1970s as a record of the things going on around me in my life, events, good and not so good things. It is a record of my life. I don’t know if anyone will read it after I am gone, but it has been handy for me at times. When I wanted to know when a certain event happened, I look back in my journal. Because people know I keep a regular journal, I have often had others call and ask me when such and such happened and I am able to find it.

I think your journal will be a wonderful record of your life, something you could pass along as an heirloom or donate to an archival library. I know lots of historical writers love to dig through those archives and learn about people’s lives. I think that’s so cool!

Thanks, but I doubt that it will ever make it into an archives. I will just be happy if my children and grandchilren appreciate it. I have read that people put all kinds of things into their journals, but this one is a life journal. That is one reason I started using some of your ideas for different kinds of journals. I have started a reading journal going all the way back to when I can remember reading, recording some of my experiences and favorite books and so on. I am doing in that way as more of a legacy in the hopes that someday my grandchildren who are avid readers (and possibly a few budding writers as well) will enjoy reading about their grandma’s reading adventures. It definitely has to be what works for a person, or they wouldn’t be motivated to write in it.

What a wonderful legacy — such a treasure. Your children and grandchildren are very lucky!

I agree your grandchildren are fortunate. I recently acquired a copy of my great, great aunt’s journal. It is priceless to me and gave me so many new insights into “pioneer days” when she and her family were traveling across the prarie during the land run in Oklahoma.

I have kept a journal for years. It does reflect what is happening in my life but is more conversations with God, my hopes and dreams, my discernments and my frustrations. I know someday my kids will read them but on a whole I am very honest in them. One of the best habits I have is to ‘harvest’ them, rereading what I write and highlighting certain passage. Get double benefits from that.

I have my great Aunt’s 60 plus years of journal and want to do something with them someday. I have a friend who typed out all of his grandfathers journals, gleaned nuggets of thoughts and wisdom and published a book for his family. Isn’t that cool?

Thanks for good thought today!

I love the double benefits of journaling. In my family, there has only been one journal/diary that I know of and I believe they threw it away because it was full of so much smack-talk about other family members. I read it and didn’t think it was all that bad, but someone got offended and our little family heirloom got tossed. Ugh, what a shame. I kind of wish someone had redacted the offending passages and kept the diary. Anyway, yes, one thing about journals is that “one day someone will read them.” People need to keep that in mind. Thanks, Jean.

I’ve been keeping a journal since I’ve been able to write. It was full of angst during my teen years, but since adulthood, it’s been mostly filled with observations and just whatever’s on my mind that day. Some could be called writing exercises, but I think they’re more like Morning Pages purging my mind of whatever ails it, to free it up for fiction writing.

I was a big teen ranter and whiner too (in my journal). I did morning pages for a while and enjoyed them very much, but I’m not a morning person, so eventually I switched. Now, I guess I write night pages, except I call them moonlight pages. Ha!

Hi melissa,

Great post! I do have a journal and I write there everything you have mentioned: ideas, thought, insights, things I observe around, small stories that come out of my mind in the middle of a train ride.

Regards, Fernanda

I love the multipurpose journal best of all. There are so many different types of journals — who needs a hundred different notebooks floating around? I’m right there with you, Fernanda, although I do have special notebooks for fiction and blogging. Everything else goes into my journal though.

Nice post with some great ideas. As to your questions, I guess I’m a journal slob too. My journal has a little bit of everything and I often put in story ideas and story beginnings. So you could say I get a lot of my writing from what began in my journal. As to what type of journal, I have recently started to keep mine at an online private journaling source, makes it really easy and convenient.

Thanks for posting this.

I’m curious about private online journaling. Do you worry about a third party having control over your journal? Do you back it up locally? I can’t journal electronically anyway. For some reason, I write all poetry and journaling (plus some fiction) longhand. I would love a tablet with a stylus!

I just started using the online journaling a couple of months ago. I use penzu.com, supposedly they use the same encryption that the military uses plus you can lock your journals with two pass codes and no one is suppose to be able to access it but you, not even their staff. You can also download it or print it out at anytime. I use to journal on my computer, because I can type faster than I can write longhand. But constantly downloading to cd and having to upload it each type I wanted to use a different computer was a real pain. I’ve lost journals due to viruses or corrupted cd’s. This way it’s all backedup automatically so I don’t have to worry about losing anything, and I can access it from anywhere. It’s really nice.

Thanks, Tiffiny. I certainly see the benefits of storing a journal online. I guess everything will eventually move to the cloud. Normally, I’m all in favor of technological advances, but storing my stuff (journals, photos, music) somewhere other than my own hard drives is one advance I’m not crazy about. I like the idea, but I am fixed on having my own backup. Anyway, I’ll definitely look into penzu.com. That sounds pretty cool!

I don’t go anywhere without my spiral notebook. I don’t really call it a journal, though. I write everything in it. From grocery lists to affirmations. I tend to think of a journal as being more personal. I cannot underatand a writer who does not keep some form of journal with them at all times. I guess they figure the good ideas will rise to the top.

I kind of understand the good-ideas-rise-to-the-top concept now. A while back, I started conceptualizing a novel and I would just think about my ideas throughout the day — for several months — and didn’t write anything down. And it worked. The best ideas stuck, so then I moved on to brainstorming and note taking. But generally, I write everything down and keep little notebooks stashed in places where I might need them in a pinch (my car, purse, nightstand).

I journaled frequently during our Peace Corps experiences in Ukraine and posted them on my website so they were availableto the public. I was amazed how many people followed them. I received many e-mails from total strangers who were living vicariously through my journals. When we returned to th euSA, we decided to do a stint in AmeriCorps*VISTA and because of my journals, someone contacted me and offered us wonderful housing (a housesitting arrangement) for the duration of our tenure. My journaling is generally reflective. I also do “morning pages” (a la “The Artist’s Way”)…these tend to be rants or details of my day or dreams and schemes and plans…these are private, unedited, quickly tapped out and I do not share them since they may be too intimate or revealing. (I use 750words.com and write as fast as I can for 20 minutes every day – no editing and no thinking just hit it sister!) It is amazing to look back at my journals and relive my thoughts and obeservations. I recommend doing this kind of daily writing. It is cathartic, healing and helps one know themselves. Life is good. “Ginn” In Steamy SC http://www.pulverpages.com (look for my Ukrainian journals there and my Malawi journals and find a link to my blog on my Camino from Roncesvalles to Santiago de Compostela)

I will definitely go check out your journals and 750words.com (I’ve never heard of that site). I love a fast, intense writing session with no editing. That’s where all my best material comes from.

I used to keep diaries when I was a kid and teenager. The ones from my teens were mainly public blogs and I wrote on them nearly everyday. In my twenties I’ve kept a private hardback journal where I write about experiences I don’t want to forget, feelings, stories, lyrics, doodles, rants, etc. I write pretty much anything I want to write about. Sometimes it helps me sort things out and other times it inspires me to write about something.

It is so weird to me that kids these days are keeping public diaries on their blogs. Blogs didn’t exist when I was a teenager (and I’m grateful for that!). When I was a teen and in my twenties, I always wrote down my favorite song lyrics (and made up plenty of my own too). What I love best about journaling is that anything goes. It’s my writing space, so I can write whatever I want there, and so can you!

Hi Melissa, I’ve kept some form of journal writing for years, but in a more deliberately conscious manner for about 8 years, in which I include, as you say, ‘free writes,’ which are so great for personal growth and awareness, as well as sudden insights about family and relationships and story ideas. I love my journal and, as I say, in recent years, keep it handy with me wherever I go.

That’s so interesting because I never get personal insights from my freewrites — just a lot of raw material that I can shape into something like a poem or song. I guess when I do focused freewrites, I solve problems, but in those cases, the freewrite has an intent (as opposed to just writing anything that comes to mind). That’s what I love about freewriting — there are so many different ways to use it.

This is the first time I’ve responded to one of your posts. Yet, you can rest assured that I read them faithfully. Why? Because, um, well, uh, because they are just so darn good!

I learn from you and enjoy the process.

Before I say how I use my journals, I must disclose that I am part owner of a business which sells guided journals as well as a home study course about how to get the most out of using a journal.

My first introduction to journal keeping came while I was in college. I treated the process poorly. I was a very bad date for my poor journal. You can say that while he was always faithful to me I certainly was not that to him.

Later, peer pressure from some very wonderful friends had me reaching for another blank book.

Now, well let’s just say my journals and I have become dearest of friends.

There is one journal which is different from all my others. I began it four years ago and there are only a few pages used. Yet, this journal is used faithfully as it was intended to be used. Once a year my granddaughter and I have a Christmas Tea. After our tea I record things about the tea and ask for her input. She will be six years old when we have our tea this year. This will be the first year her own pen will touch the page.

My desire is that she continue the Christmas Tea Celebration as well as the recording of the event after my death. Perhaps her mom or a friend will join her. Some day her own daughter may be her guest.

At any rate, the treasure she and I are creating together is worth more than any gold I might think of leaving her.

Thank you for your kind words, Yvonne. Your Christmas Tea Celebration and its accompanying journal is a beautiful idea. What a wonderful thing to share with the little ones. I think it’s a lovely tradition.

Yes, I always keep a journal. My thing is to not put any rules on it or it stresses me out. So, it is chaotic, unorganized, pages ripped out, stuff written here and there, scribbles, magazine clippings stuffed inside, pictures stuffed in. Messy.

Rules are stressful, aren’t they? I find that sometimes rules promote creativity but other times (like in my own journal), they hinder it, so I’m with you Kristy — I like a messy journal.

Your post is wondeful!! I do have a journal about which i had forgotten for almost a month :/ Reading your post just reminded of the fact that it was only because of constant reflective writing in my journal that i realised that this (writing) was what i want to do for my entire life! Thank you 🙂

I think a lot of writers start out by keeping a journal. There’s something about journal writing that comes naturally to certain people, and it makes sense that they would go on to become writers.

I started to keep an everyday journal when I was going through a tough time (about 4yrs now), it was suggested to me and ever since I’ve been keeping one. It’s great to get things out,sometimes though it’s hard to put everything down because I’m afraid someone will read it (because they would if they found it).lol but I use my journal for writing thoughts, feelings about things and people,memories,dreams/nightmares, I write about events that have happened too good and bad, I do drawings,sketches,poems,favorite quotes, stick in fav pics etc. Basically a bit of everything!! I prefer leather bound journals with plain paper but at the mo I’m trying out an art blanc journal because the design caught my eye,not to fond of being restricted to lines though! 🙂 I hope I keep one on into my life,sometimes I forget how helpful it is.

Great post! 😀

Your journal sounds a lot like mine! I do have a suggestion for you. If you’re uncomfortable writing your private thoughts in your journal because you’re worried someone will invade your privacy, you might develop a code system or use images instead of text to express certain ideas. I used to use code names for people, and I would sometimes write certain words in another language or using icons. It also makes journaling a little more interesting.

I call my journals Daily Milestones, because that’s what life feels like to me. Even in the most mundane days where I don’t engage in many activities, I can still have an epiphany in some way or another. If I’ve had an activity packed day or week, then I can go off even more!

I also like titling each entry with something witty like Planting Seeds in the Sandbox because it sometimes keeps the focus and intent of a certain entry. That one in particular is about how life is like a giant sandbox and how we, like children, like to play different roles. We plant “seeds” of our imagination to sprout into our reality.

When I first started keeping a journal in 2009, my entries would just be positive messages and revelations about life, but as time went on, they became more personal. I began writing about actual events in my day rather than just abstract inspirations. It felt odd to write about what happened in my day and even more weird to write how I felt about different aspects of the day and my life. I realized if I’m not gonna be honest with myself, especially where I have all the space and time to do so; what chance would I have with being honest with other people or in my creative writing?

It’s really helpful as a fiction writer to keep a journal because I notice a lot of recurring themes to write about: Reminders of how to remain on the path of truth and virtue amongst the many others that would take too much space in my post. One thing I find is how I judge/commend other people. When I write about other people they feel like they become fictional characters because of how I pick apart their faults and qualities. It helps me see them multidimensionally and transfer that realism in the characters I create in my stories.

And of course all this leads to a massive insight to self discovery as I find myself revisitting old entries just in case I’ve strayed from the path.

Thank you, Marlon, for sharing your experience with reflective journaling and explaining how it has benefited you as a writer, storyteller, and human being. What a wonderful testimonial!

Hi Melissa, sounds like your reflective journal is much like mine, with ideas, lists, doodles and plenty of free writing and first drafts of poem. I also note down story ideas and scraps of conversation or a phrase from someone else’s poem or story – so I suppose mine is a journal cum writer;s notebook. I also have a pad specifically for things to do and also my diary and when I look through they also seem to be combination of things, sometimes including pitching ideas and client requests.

Thanks, Sue. I love learning about how other writers use their journals, notebooks, and other writing tools. I’m glad you shared yours!

Hi Melissa,

I have been filling sketchbooks for years as a way of developing my watercolor painting skills, but I am a writer too, so inevitably I worte abd write a lot too, sometimes more than I sketched. Currrently, my main journal is a sewn-binding refill from Renaissance-Art. I have about 14 of them filled. I use mostly the 5.5 x 8.5 size and put my own hardbound covers on them when done, usualy with a sketch or writing on it and imitation leather trip. I use them for sketches on the spot or from photos, like a scrapbook at times, pasting in photos and this and that. An yes, resflections, insights, acconts of evens and trips, just about anything.

Good post, as usual. Thanks.

Hi Bill! Even though I can’t see your journals, they sound beautiful! I love when words and art come together.

I honestly don’t keep a journal,but I periodicaly write in a tablet ideas for new story development. ps.I have a book out the title is THE SIR DAVID THOMAS SERIES.Perhaps it may be something you would like to read.

A tablet or notebook could be considered a journal.

Honestly, i also don’t keep a journal, but I’d write my story ideas, probable developments of them , brainy quotes by others in every-day life and any interesting observation in my phone, laptop, or on a variety of papers (which do not form a notebook in whole!). But I have a separate notebook to jot down ideas for my thesis research report. I guess I’ll keep on writing my creative notes also in future in the same manner.

Yes, now with all these electronic devices, I think a lot of writers’ notes are becoming spread out. I use Evernote, which syncs to all my devices, including my computer. It has tons of great features — for example, you can clip stuff from the web. You can also create multiple notebooks.

Hi Melissa, Personally, I love keeping journals. I have multiple journals for different things. My private journal is just a regular composition notebook where I write down basically all my thoughts and things that happen to me. Occasionally, I paste pictures and articles. Another journal I keep is a spiral-bound notebook where I write down ideas, poems, short stories, etc. I have a couple of those, and I tend to read through them from time to time. I find it helpful to keep journals, that way, I can see the progress I’ve made over the years.

I love flipping through my old idea journals. I often find little treasures that I’ve forgotten about! Sometimes I even find an old idea that I’m now ready to use.

As silly as it might sound to some, I have MANY journals I keep at once. Of course, I have many to begin with and have been journaling since 1983…I have a journal of daily quotes filled with awe inspiring quotes from famous or important to me people. I journal of family history stories for when the thoughts and memories arise, I record them. My everyday (but not always every day) journal filled with intimate and inspiring yet sometimes dark and dreary moments in life. I have two journals (one for each of my children) loaded with photos and stories of important and important to me events to record in each of their lives. I have a Christmas and Thanksgiving journal so I can record each and every holiday and gathering with family and friends and including the preparing and gift giving. A travel journal that I use to prep for journeys and attach receipts and pics and business cards. I must not forget to mention the Bibliophile Reader’s Journal to record books I am reading so that I remember the most important details from each. An honorable mention is the Homes I Have Lived In Journal where I sketch out each home’s floor plan and add pics from our old albums to depict a room that just happened to be in old photos we took. One might ask, why so many as opposed to combining all in one? My simplest answer is; each journal represents a complex chapter in the Life of Me.

That’s awesome, Marcy! What a wonderful collection you’re creating.

I have already been trying to experiment on different types of journaling method since I was a child. My family knew how attached I have always been to notebooks.However, I would always find it too tedious to keep different notebooks for different aspects of my life. Finally, at 2018, I discovered the bullet journaling method. That was when I realized that I could actually keep an all-in-one journal. Currently, my bullet journal houses my ideas, my Bible reading and book reading reflections, and my thoughts. It also serves as my diary. But probably the most treasured part of my journal is Dream Notes section where I keep my most memorable dreams. That is because I would usually have weird and vivid dreams that sometimes serve as reflections of my current mental or emotional state. Other times, those dreams could be excellent sources for stories and poems. I’m always amazed of what my mind could conceive while I’m asleep. So I keep them recorded in my journal.

I use a variation of bullet journaling too. I’ve been doing it for a couple of years now (just ordered my third one) and it’s been pretty awesome. I use mine strictly as a planner, calendar, and tracker. I’m not sure I’ll keep all those journals; they’re mostly full of work-related stuff. So I like to keep my creative journals separate. I love notebooks too. Can’t have too many!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Top Picks Thursday! For Readers and Writers 07-14-2016 | The Author Chronicles - […] and craft can be improved in many ways. Melissa Donovan shows the power of reflective journaling, and Jordan Dane…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Writing When You’re Not in the Mood

- How to Write Faster

- Writing Tips For Staying on Your Game

- Writing Resources: Bird by Bird

- Punctuation Marks: The Serial Comma

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 14, 2023

10 Types of Creative Writing (with Examples You’ll Love)

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

About Rebecca van Laer

Rebecca van Laer is a writer, editor, and the author of two books, including the novella How to Adjust to the Dark. Her work has been featured in literary magazines such as AGNI, Breadcrumbs, and TriQuarterly.

A lot falls under the term ‘creative writing’: poetry, short fiction, plays, novels, personal essays, and songs, to name just a few. By virtue of the creativity that characterizes it, creative writing is an extremely versatile art. So instead of defining what creative writing is , it may be easier to understand what it does by looking at examples that demonstrate the sheer range of styles and genres under its vast umbrella.

To that end, we’ve collected a non-exhaustive list of works across multiple formats that have inspired the writers here at Reedsy. With 20 different works to explore, we hope they will inspire you, too.

People have been writing creatively for almost as long as we have been able to hold pens. Just think of long-form epic poems like The Odyssey or, later, the Cantar de Mio Cid — some of the earliest recorded writings of their kind.

Poetry is also a great place to start if you want to dip your own pen into the inkwell of creative writing. It can be as short or long as you want (you don’t have to write an epic of Homeric proportions), encourages you to build your observation skills, and often speaks from a single point of view .

Here are a few examples:

“Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This classic poem by Romantic poet Percy Shelley (also known as Mary Shelley’s husband) is all about legacy. What do we leave behind? How will we be remembered? The great king Ozymandias built himself a massive statue, proclaiming his might, but the irony is that his statue doesn’t survive the ravages of time. By framing this poem as told to him by a “traveller from an antique land,” Shelley effectively turns this into a story. Along with the careful use of juxtaposition to create irony, this poem accomplishes a lot in just a few lines.

“Trying to Raise the Dead” by Dorianne Laux

A direction. An object. My love, it needs a place to rest. Say anything. I’m listening. I’m ready to believe. Even lies, I don’t care.

Poetry is cherished for its ability to evoke strong emotions from the reader using very few words which is exactly what Dorianne Laux does in “ Trying to Raise the Dead .” With vivid imagery that underscores the painful yearning of the narrator, she transports us to a private nighttime scene as the narrator sneaks away from a party to pray to someone they’ve lost. We ache for their loss and how badly they want their lost loved one to acknowledge them in some way. It’s truly a masterclass on how writing can be used to portray emotions.

If you find yourself inspired to try out some poetry — and maybe even get it published — check out these poetry layouts that can elevate your verse!

Song Lyrics

Poetry’s closely related cousin, song lyrics are another great way to flex your creative writing muscles. You not only have to find the perfect rhyme scheme but also match it to the rhythm of the music. This can be a great challenge for an experienced poet or the musically inclined.

To see how music can add something extra to your poetry, check out these two examples:

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen

You say I took the name in vain I don't even know the name But if I did, well, really, what's it to ya? There's a blaze of light in every word It doesn't matter which you heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Metaphors are commonplace in almost every kind of creative writing, but will often take center stage in shorter works like poetry and songs. At the slightest mention, they invite the listener to bring their emotional or cultural experience to the piece, allowing the writer to express more with fewer words while also giving it a deeper meaning. If a whole song is couched in metaphor, you might even be able to find multiple meanings to it, like in Leonard Cohen’s “ Hallelujah .” While Cohen’s Biblical references create a song that, on the surface, seems like it’s about a struggle with religion, the ambiguity of the lyrics has allowed it to be seen as a song about a complicated romantic relationship.

“I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie

If Heaven and Hell decide that they both are satisfied Illuminate the no's on their vacancy signs If there's no one beside you when your soul embarks Then I'll follow you into the dark

You can think of song lyrics as poetry set to music. They manage to do many of the same things their literary counterparts do — including tugging on your heartstrings. Death Cab for Cutie’s incredibly popular indie rock ballad is about the singer’s deep devotion to his lover. While some might find the song a bit too dark and macabre, its melancholy tune and poignant lyrics remind us that love can endure beyond death.

Plays and Screenplays

From the short form of poetry, we move into the world of drama — also known as the play. This form is as old as the poem, stretching back to the works of ancient Greek playwrights like Sophocles, who adapted the myths of their day into dramatic form. The stage play (and the more modern screenplay) gives the words on the page a literal human voice, bringing life to a story and its characters entirely through dialogue.

Interested to see what that looks like? Take a look at these examples:

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

“I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Arthur Miller acts as a bridge between the classic and the new, creating 20th century tragedies that take place in living rooms and backyard instead of royal courts, so we had to include his breakout hit on this list. Set in the backyard of an all-American family in the summer of 1946, this tragedy manages to communicate family tensions in an unimaginable scale, building up to an intense climax reminiscent of classical drama.

💡 Read more about Arthur Miller and classical influences in our breakdown of Freytag’s pyramid .

“Everything is Fine” by Michael Schur ( The Good Place )

“Well, then this system sucks. What...one in a million gets to live in paradise and everyone else is tortured for eternity? Come on! I mean, I wasn't freaking Gandhi, but I was okay. I was a medium person. I should get to spend eternity in a medium place! Like Cincinnati. Everyone who wasn't perfect but wasn't terrible should get to spend eternity in Cincinnati.”

A screenplay, especially a TV pilot, is like a mini-play, but with the extra job of convincing an audience that they want to watch a hundred more episodes of the show. Blending moral philosophy with comedy, The Good Place is a fun hang-out show set in the afterlife that asks some big questions about what it means to be good.

It follows Eleanor Shellstrop, an incredibly imperfect woman from Arizona who wakes up in ‘The Good Place’ and realizes that there’s been a cosmic mixup. Determined not to lose her place in paradise, she recruits her “soulmate,” a former ethics professor, to teach her philosophy with the hope that she can learn to be a good person and keep up her charade of being an upstanding citizen. The pilot does a superb job of setting up the stakes, the story, and the characters, while smuggling in deep philosophical ideas.

Personal essays

Our first foray into nonfiction on this list is the personal essay. As its name suggests, these stories are in some way autobiographical — concerned with the author’s life and experiences. But don’t be fooled by the realistic component. These essays can take any shape or form, from comics to diary entries to recipes and anything else you can imagine. Typically zeroing in on a single issue, they allow you to explore your life and prove that the personal can be universal.

Here are a couple of fantastic examples:

“On Selling Your First Novel After 11 Years” by Min Jin Lee (Literary Hub)

There was so much to learn and practice, but I began to see the prose in verse and the verse in prose. Patterns surfaced in poems, stories, and plays. There was music in sentences and paragraphs. I could hear the silences in a sentence. All this schooling was like getting x-ray vision and animal-like hearing.

This deeply honest personal essay by Pachinko author Min Jin Lee is an account of her eleven-year struggle to publish her first novel . Like all good writing, it is intensely focused on personal emotional details. While grounded in the specifics of the author's personal journey, it embodies an experience that is absolutely universal: that of difficulty and adversity met by eventual success.

“A Cyclist on the English Landscape” by Roff Smith (New York Times)

These images, though, aren’t meant to be about me. They’re meant to represent a cyclist on the landscape, anybody — you, perhaps.

Roff Smith’s gorgeous photo essay for the NYT is a testament to the power of creatively combining visuals with text. Here, photographs of Smith atop a bike are far from simply ornamental. They’re integral to the ruminative mood of the essay, as essential as the writing. Though Smith places his work at the crosscurrents of various aesthetic influences (such as the painter Edward Hopper), what stands out the most in this taciturn, thoughtful piece of writing is his use of the second person to address the reader directly. Suddenly, the writer steps out of the body of the essay and makes eye contact with the reader. The reader is now part of the story as a second character, finally entering the picture.

Short Fiction

The short story is the happy medium of fiction writing. These bite-sized narratives can be devoured in a single sitting and still leave you reeling. Sometimes viewed as a stepping stone to novel writing, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Short story writing is an art all its own. The limited length means every word counts and there’s no better way to see that than with these two examples:

“An MFA Story” by Paul Dalla Rosa (Electric Literature)

At Starbucks, I remembered a reading Zhen had given, a reading organized by the program’s faculty. I had not wanted to go but did. In the bar, he read, "I wrote this in a Starbucks in Shanghai. On the bank of the Huangpu." It wasn’t an aside or introduction. It was two lines of the poem. I was in a Starbucks and I wasn’t writing any poems. I wasn’t writing anything.

This short story is a delightfully metafictional tale about the struggles of being a writer in New York. From paying the bills to facing criticism in a writing workshop and envying more productive writers, Paul Dalla Rosa’s story is a clever satire of the tribulations involved in the writing profession, and all the contradictions embodied by systemic creativity (as famously laid out in Mark McGurl’s The Program Era ). What’s more, this story is an excellent example of something that often happens in creative writing: a writer casting light on the private thoughts or moments of doubt we don’t admit to or openly talk about.

“Flowering Walrus” by Scott Skinner (Reedsy)

I tell him they’d been there a month at least, and he looks concerned. He has my tongue on a tissue paper and is gripping its sides with his pointer and thumb. My tongue has never spent much time outside of my mouth, and I imagine it as a walrus basking in the rays of the dental light. My walrus is not well.

A winner of Reedsy’s weekly Prompts writing contest, ‘ Flowering Walrus ’ is a story that balances the trivial and the serious well. In the pauses between its excellent, natural dialogue , the story manages to scatter the fear and sadness of bad medical news, as the protagonist hides his worries from his wife and daughter. Rich in subtext, these silences grow and resonate with the readers.

Want to give short story writing a go? Give our free course a go!

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

Perhaps the thing that first comes to mind when talking about creative writing, novels are a form of fiction that many people know and love but writers sometimes find intimidating. The good news is that novels are nothing but one word put after another, like any other piece of writing, but expanded and put into a flowing narrative. Piece of cake, right?

To get an idea of the format’s breadth of scope, take a look at these two (very different) satirical novels:

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this. Once we donned our uniforms, we were all equals regardless of gender, age, or nationality — all simply store workers.

Keiko, a thirty-six-year-old convenience store employee, finds comfort and happiness in the strict, uneventful routine of the shop’s daily operations. A funny, satirical, but simultaneously unnerving examination of the social structures we take for granted, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is deeply original and lingers with the reader long after they’ve put it down.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The hard, gritty truth of the matter is that I hardly ever think about race. Those times when I did think about it a lot I did so because of my guilt for not thinking about it.

Erasure is a truly accomplished satire of the publishing industry’s tendency to essentialize African American authors and their writing. Everett’s protagonist is a writer whose work doesn’t fit with what publishers expect from him — work that describes the “African American experience” — so he writes a parody novel about life in the ghetto. The publishers go crazy for it and, to the protagonist’s horror, it becomes the next big thing. This sophisticated novel is both ironic and tender, leaving its readers with much food for thought.

Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is pretty broad: it applies to anything that does not claim to be fictional (although the rise of autofiction has definitely blurred the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction). It encompasses everything from personal essays and memoirs to humor writing, and they range in length from blog posts to full-length books. The defining characteristic of this massive genre is that it takes the world or the author’s experience and turns it into a narrative that a reader can follow along with.

Here, we want to focus on novel-length works that dig deep into their respective topics. While very different, these two examples truly show the breadth and depth of possibility of creative nonfiction:

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Men’s bodies litter my family history. The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.

Writer Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five men from her rural Mississippi community in as many years. In her award-winning memoir , she delves into the lives of the friends and family she lost and tries to find some sense among the tragedy. Working backwards across five years, she questions why this had to happen over and over again, and slowly unveils the long history of racism and poverty that rules rural Black communities. Moving and emotionally raw, Men We Reaped is an indictment of a cruel system and the story of a woman's grief and rage as she tries to navigate it.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker

He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life. That’s why he preferred buying bottles to splurging on sweaters. Sweaters were things. Bottles of wine, said Morgan, “are ways that my humanity will be changed.”

In this work of immersive journalism , Bianca Bosker leaves behind her life as a tech journalist to explore the world of wine. Becoming a “cork dork” takes her everywhere from New York’s most refined restaurants to science labs while she learns what it takes to be a sommelier and a true wine obsessive. This funny and entertaining trip through the past and present of wine-making and tasting is sure to leave you better informed and wishing you, too, could leave your life behind for one devoted to wine.

Illustrated Narratives (Comics, graphic novels)

Once relegated to the “funny pages”, the past forty years of comics history have proven it to be a serious medium. Comics have transformed from the early days of Jack Kirby’s superheroes into a medium where almost every genre is represented. Humorous one-shots in the Sunday papers stand alongside illustrated memoirs, horror, fantasy, and just about anything else you can imagine. This type of visual storytelling lets the writer and artist get creative with perspective, tone, and so much more. For two very different, though equally entertaining, examples, check these out:

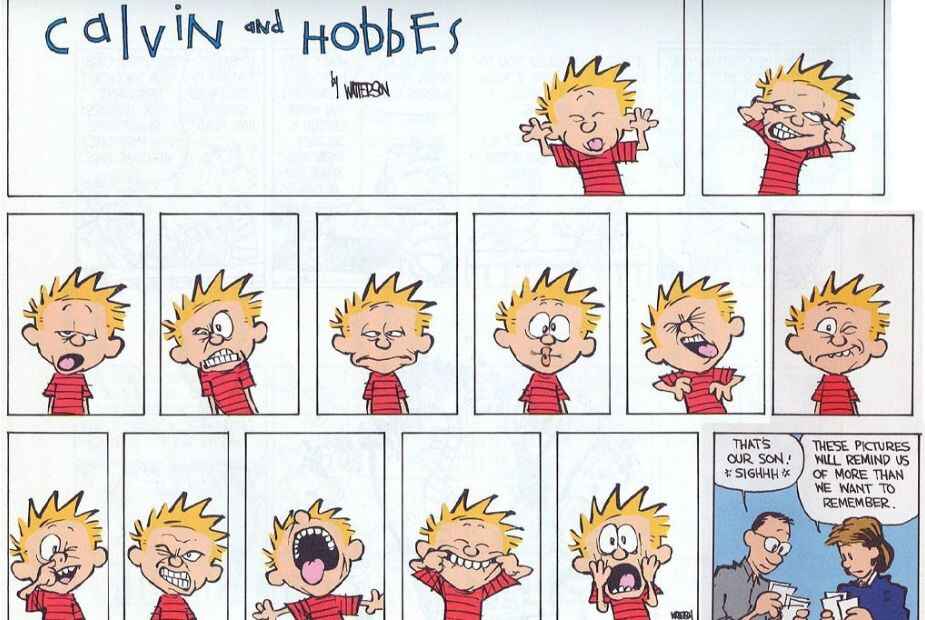

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

"Life is like topography, Hobbes. There are summits of happiness and success, flat stretches of boring routine and valleys of frustration and failure."

This beloved comic strip follows Calvin, a rambunctious six-year-old boy, and his stuffed tiger/imaginary friend, Hobbes. They get into all kinds of hijinks at school and at home, and muse on the world in the way only a six-year-old and an anthropomorphic tiger can. As laugh-out-loud funny as it is, Calvin & Hobbes ’ popularity persists as much for its whimsy as its use of humor to comment on life, childhood, adulthood, and everything in between.

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

"I shall tell you where we are. We're in the most extreme and utter region of the human mind. A dim, subconscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves. Hell, Netley. We're in Hell."

Comics aren't just the realm of superheroes and one-joke strips, as Alan Moore proves in this serialized graphic novel released between 1989 and 1998. A meticulously researched alternative history of Victorian London’s Ripper killings, this macabre story pulls no punches. Fact and fiction blend into a world where the Royal Family is involved in a dark conspiracy and Freemasons lurk on the sidelines. It’s a surreal mad-cap adventure that’s unsettling in the best way possible.

Video Games and RPGs

Probably the least expected entry on this list, we thought that video games and RPGs also deserved a mention — and some well-earned recognition for the intricate storytelling that goes into creating them.

Essentially gamified adventure stories, without attention to plot, characters, and a narrative arc, these games would lose a lot of their charm, so let’s look at two examples where the creative writing really shines through:

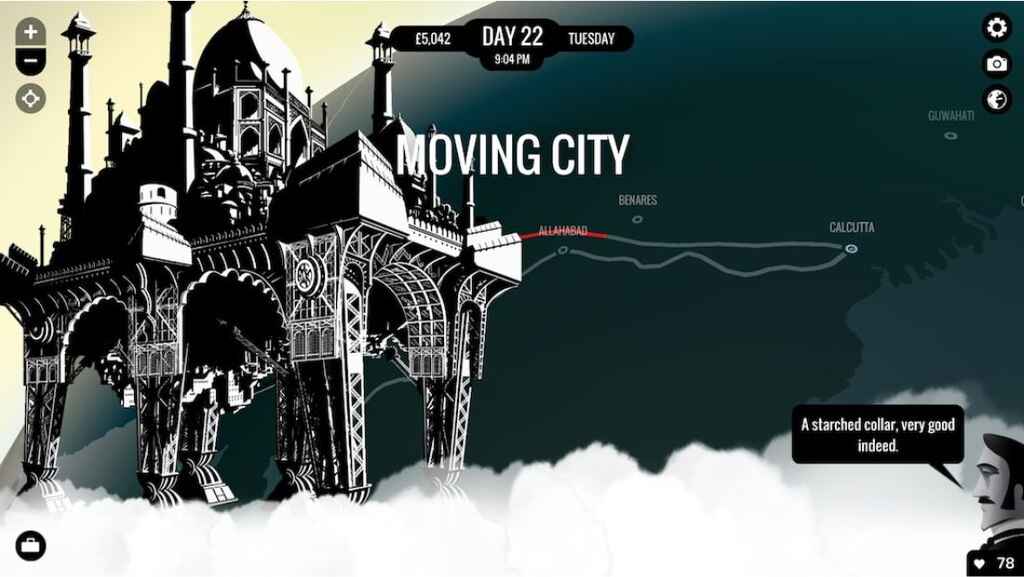

80 Days by inkle studios

"It was a triumph of invention over nature, and will almost certainly disappear into the dust once more in the next fifty years."

Named Time Magazine ’s game of the year in 2014, this narrative adventure is based on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne. The player is cast as the novel’s narrator, Passpartout, and tasked with circumnavigating the globe in service of their employer, Phileas Fogg. Set in an alternate steampunk Victorian era, the game uses its globe-trotting to comment on the colonialist fantasies inherent in the original novel and its time period. On a storytelling level, the choose-your-own-adventure style means no two players’ journeys will be the same. This innovative approach to a classic novel shows the potential of video games as a storytelling medium, truly making the player part of the story.

What Remains of Edith Finch by Giant Sparrow

"If we lived forever, maybe we'd have time to understand things. But as it is, I think the best we can do is try to open our eyes, and appreciate how strange and brief all of this is."

This video game casts the player as 17-year-old Edith Finch. Returning to her family’s home on an island in the Pacific northwest, Edith explores the vast house and tries to figure out why she’s the only one of her family left alive. The story of each family member is revealed as you make your way through the house, slowly unpacking the tragic fate of the Finches. Eerie and immersive, this first-person exploration game uses the medium to tell a series of truly unique tales.

Fun and breezy on the surface, humor is often recognized as one of the trickiest forms of creative writing. After all, while you can see the artistic value in a piece of prose that you don’t necessarily enjoy, if a joke isn’t funny, you could say that it’s objectively failed.

With that said, it’s far from an impossible task, and many have succeeded in bringing smiles to their readers’ faces through their writing. Here are two examples:

‘How You Hope Your Extended Family Will React When You Explain Your Job to Them’ by Mike Lacher (McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

“Is it true you don’t have desks?” your grandmother will ask. You will nod again and crack open a can of Country Time Lemonade. “My stars,” she will say, “it must be so wonderful to not have a traditional office and instead share a bistro-esque coworking space.”

Satire and parody make up a whole subgenre of creative writing, and websites like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Onion consistently hit the mark with their parodies of magazine publishing and news media. This particular example finds humor in the divide between traditional family expectations and contemporary, ‘trendy’ work cultures. Playing on the inherent silliness of today’s tech-forward middle-class jobs, this witty piece imagines a scenario where the writer’s family fully understands what they do — and are enthralled to hear more. “‘Now is it true,’ your uncle will whisper, ‘that you’ve got a potential investment from one of the founders of I Can Haz Cheezburger?’”

‘Not a Foodie’ by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell (Electric Literature)

I’m not a foodie, I never have been, and I know, in my heart, I never will be.

Highlighting what she sees as an unbearable social obsession with food , in this comic Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell takes a hilarious stand against the importance of food. From the writer’s courageous thesis (“I think there are more exciting things to talk about, and focus on in life, than what’s for dinner”) to the amusing appearance of family members and the narrator’s partner, ‘Not a Foodie’ demonstrates that even a seemingly mundane pet peeve can be approached creatively — and even reveal something profound about life.

We hope this list inspires you with your own writing. If there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be that there is no limit to what you can write about or how you can write about it.

In the next part of this guide, we'll drill down into the fascinating world of creative nonfiction.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

You are using an outdated browser. Please click here to upgrade your browser & improve your experience.

Explore #WeAreOCA

Writing a good reflective commentary

I recently a ran an online workshop on what a good RC might include, so for those of students who were unable to attend (and for those who did attend, but would like a refresher), here’s a summary of my suggestions.

First of all, I think it’s helpful to remember the differences between notebooks, your writing diary and a Reflective Commentary:

Notebooks are where you start writing creatively, whether in the form of ideas and notes or sketches and early drafts. Notebook writing can form the basis of the projects and creative writing assignments that you will send to your tutor. You may find yourself starting numerous notebooks for different areas of interest.

No one will read your notebooks except you. Privacy is important because the thought of anyone reading your writing may inhibit you. Notebooks can be paper or electronic (many people use their phones for jotting down ideas), or a combination of both – it’s totally up to you.

Writing Diary:

Your writing diary is where you record your thoughts on your writing and your developing writing skills. You can discuss and reflect on concepts related to the writing craft here and reflect on what you feel your own strengths and weaknesses are. What are you good at? What do you need to work on? How can you improve these skills? Which writers can you learn from? What have you been reading?

When you are generating new writing material, you’ll be partly learning on an intuitive level. A writing diary will help you to be more conscious of your learning process and more aware of the different skills you’re developing. If you add to your diary regularly, it will form a record of your writing journey.

Like your notebooks, your writing diary is for you alone and you can keep it in whatever format you prefer.

You can use your writing diary to help you write your Reflective Commentaries, but they aren’t the same thing.

Reflective Commentaries:

A Reflective Commentary is either a short piece of reflective writing (500 words for Levels 1, 2 and 3; or 350 words at Foundation Level) considering the particular assignment it accompanies, or it’s a longer piece of reflective writing which you submit at the end of the unit in which you reflect on your learning over the unit as a whole, with reference to particular assignments (especially the final assignment).

A few dos and don’ts:

Don’t discuss how you came up with your idea.

Don’t discuss pieces you started and discarded.

Don’t summarise the story, poem, script etc. – your tutor has just read it..

Do focus on the creative work you’ve just submitted to your tutor.

Do focus on a few writing techniques you’ve used in the work. You can’t cover everything, so choose those that are particularly pertinent.

Do say what writing techniques you used and why they were effective.

So, don’t say: “I wrote my story in first person” and leave it at that. Instead say: “I wrote my story in first person because I wanted the feeling of intimacy of the narrator talking directly to the reader about the events. This was important for my story because….”

Discussing Writing Techniques:

The term ‘writing techniques’ may seem rather abstract, but all it means is those techniques you used to write your creative piece. Here’s a selection of writing techniques you could consider:

Techniques in fiction:

Descriptive writing, metaphors and similes, setting, character, use of dialogue, structure, narrative pacing, point of view, tense (usually past or present), use of flashback (or, occasionally, flashforward), voice, word choice, register (formal or casual), information reveal (what do you tell the reader and when), psychic distance, use of free indirect discourse, sentence structure (e.g. a short sentence at the end of a paragraph for impact).

Techniques in poetry:

Use of stanzas, use of punctuation, imagery, word choice, tone, structure, point of view, use of sound (e.g. rhyme, or assonance, alliteration), rhythm.

These are just a few of the techniques you could discuss – there may be others that are more relevant to your particular piece of creative work.

The tone of the RC:

The reflective commentary is not an academic essay, so you don’t need to use academic jargon. Use first person, because it’s a personal reflection on your work.

However, don’t be too colloquial and chatty either – your tone needs to be moderate and considered. Don’t say “I tried to do X but it was rubbish”. Instead, say you thought it wasn’t successful as a technique and explain why.

Similarly, when discussing your reading, don’t just say “I loved this book” or “It was fab”. Instead, explain what you thought was good about it and why. Give your opinion, but support it with careful analysis.

Reflecting on your reading:

In the assessment criteria, a proportion of marks are allocated for Contextual Knowledge. Your final RC is your opportunity to demonstrate that you’ve read other writers and engaged with them seriously, not just as a reader, but as another writer.

In your final RC you should refer to both primary materials (e.g. novels, poems, stories, plays, films, memoirs, poetry performances, etc – depending on what form you’re writing in) and secondary materials (e.g. books, articles, blogs, videos, etc. about the craft of writing).

Get into good habits early on by referring to some primary and some secondary materials in your short RCs submitted with each assignment.

Think about what you’ve learnt from your reading in terms of craft – this is much more impressive than just saying you were inspired to write about the same subject.

So don’t say, “I enjoyed Vicki Feaver’s poem ‘Ironing’ and decided to write a poem about ironing of my own.” This might be true and you can put this in your writing diary, but in your RC try to think about what you learnt about the craft of writing poetry from your reading.

Include short quotations from your reading to demonstrate your points, but a short phrase or single sentence usually suffices (remember you’ve only 500 words for the short RCs).

The Final RC:

The Final RC is longer and in it you should consider what you’ve learnt from the unit as whole, as well as referring to particular assignments. You will now be close to preparing your work for assessment, so you should discuss your redrafting process – what you’ve changed and why – and also demonstrate your engagement with your tutor’s feedback.

Reflecting on redrafting:

Be precise. Don’t just say “I cut extraneous words” or “I rewrote Assignment 4 a lot”. Give examples of what you changed and why .

Use quotations from your own work when discussing what you’ve changed, but be brief: just a pertinent sentence or phrase.

Don’t just give a quotation from your assignment that shows it before redrafting, and then one after. Discuss the changes made and say why you think it is an improvement.

Reflecting on tutor feedback:

You don’t need to agree with every suggestion or comment from your tutor, but you do need to show you’ve thought about your tutor’s feedback.

Similarly, don’t say you changed something just because your tutor told you to – only change it if you think it’s the right change to make, and say why you think so.

A quirk of the system is that at Level 1 you are likely to write this final reflective commentary before receiving feedback on Assignment Five. You’ll need to redraft your final RC and add comments about your tutor feedback’s on Assignment Five and your redrafting process, before you submit this final RC for assessment.

Submit both your tutor-annotated final RC and a redrafted version at assessment.

Referencing:

Include a bibliography/reference list at end of all sources referred to in your RC (but don’t include anything you’ve not directly referred to), and use the Harvard Referencing Style.

The Bibliography does not form part of your word count.

Why write RCs:

Writing the reflective commentaries is an important part of the creative writing degree and the RCs serve several purposes. They are useful for tutors as they help us to understand students’ aims in a particular piece of writing. They should demonstrate students’ critical engagement with other writers as well as with books, articles, blogs etc. about the craft of writing, which helps us make better reading suggestions and to understand where our students are on their learning journey.

But, and arguably much more importantly, they’re a crucial part of your learning process, as they require a conscious engagement with the writing craft and a reflection on your writing skills, all of which will help you to think ‘like a writer’.

11 thoughts on “ Writing a good reflective commentary ”

Thank you Vicky. The workshop helped me have a better understanding of reflective commentaries.

This is an interesting article. I am studying photography and part of the work involves writing critiques of other people’s work. The guidelines set out above are relevant to any critique, whatever the subject matter. Thank you. I will be putting these suggestions into practice in my future work.

Thanks Vicky. I like the way you start with the Don’ts before the Dos!

Great advice Vicky! It would be lovely to see another workshop covering Reflective Commentaries. For some reason I struggle to get these right when doing my own R.Cs for the Art of Poetry.

This book called called: “Creative Writing and Critical Reflective Commentary.” was the only recent book I could find. It was really helpful to me It has an example in it and what else to include like references and how to write reflecively with underpinning critical theories.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B098MXYY54

https://celoe.telkomuniversity.ac.id/

“Your blog always provides valuable insights. Thank you for sharing!”

“I noticed you mentioned a study in this article. Do you have a link to the source for more information?”

It is critical to recognize the differences between notebooks, writing diaries, and Reflective Commentaries. Your workshop overview is important to both attendees and those who were unable to participate. Such clear thoughts greatly boost our writing experience. Thank you for sharing this enlightened viewpoint!

I’m really intrigues to know why you say so emphatically not to write about how you cam up with an idea – I would have thought his was crucial to the reflective process. Could you explain?

Your blog is appreciated for its usefulness and informative content. IFDA is the best institute for Computer Courses in Delhi and after that any courses completed IFDA is providing paid internship & 100% job placement. Best Computer Course in Delhi

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

> Next Post What is conflict?

Edge zine – submit by 15 july 2020.

Open College Of The Arts Degree Show Showcase

OCA’s Online Degree Show Showcase 2023

OCA Degree Show Showcase 21/22

OCA News: Student Fees from August 2022

Reflective Writing

“Reflection is a mode of inquiry: a deliberate way of systematically recalling writing experiences to reframe the current writing situation. It allows writers to recognize what they are doing in that particular moment (cognition), as well as to consider why they made the rhetorical choices they did (metacognition). The combination of cognition and metacognition, accessed through reflection, helps writers begin assessing themselves as writers, recognizing and building on their prior knowledge about writing.” —Kara Taczak, “Reflection is Critical for Writers’ Development” (78) Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies

Reflective writing assignments are common across the university. You may be asked to reflect on your learning, your writing, your personal experiences in relation to a theory or text, or your personal experiences in an internship or other type of experience in relation to course readings. These are assignments, as Kara Taczak notes, that offer opportunities to solidify knowledge about our experiences and how they might relate to others’ experiences and existing research. Moreso, reflection can lead to more informed understandings of our own experiences and course content in ways that may make that knowledge more useful in future classes and practice. However, often reflective writing is not taught as an explicit writing skill and can be problematically treated as a less rigorous form of writing. Below are some broad writing tips that can help not only your reflective writing to be stronger, but also the reflective inquiry to be more meaningful.

Collect relevant evidence before you start writing.

Yes–we recommend using evidence in reflective writing! When connecting personal experiences to the readings, that means selecting quotes from the readings and then coming up with specific moments in your life that relate to those quotes. When reflecting on learning or growth, that might mean locating evidence (quotes) from your previous papers that showcase growth.

Be specific.

It’s really easy to see reflective writing as more informal or casual, and thus, as requiring less attention to details; however, strong reflective writing is very precise and specific. Some examples of statements that are too vague and meaningless include, “I learned a lot about writing this semester.” Or, “I feel like my experiences are exactly as Author B says in this quote.” Neither of these statements tells us much–they are a bit devoid of content. Instead, try to name exactly what you learned about writing or exactly how your experiences are related to the quote. For example, you might reflect, “At the beginning of the semester, unsure of how to summarize a text well, I was just describing the main the idea of the text. However, after learning about Harris’ concept of capturing a writer’s “project,” I believe I have become better at really explaining a text as a whole. Specifically, in my last essay, I was able to provide a fully developed explanation of Author A’s argument and purpose for the essay as well as their materials and methods (that is, how they made the argument). For example, in this quote from my last essay,...”

Focus on a small moment from your experiences.

It’s hard to not want to recap our entire childhood or the full summer before something happened for context when sharing a personal story. However, it’s usually more effective to select a very specific moment in time and try to accurately describe what happened, who was involved, and how it made you feel and react. When writing about a moment, try to place readers there with you–help readers to understand what happened, who was involved, where it happened, why it happened, and what the results were. If this is a more creative assignment, you might even include some sensory descriptions to make the moment more of an experience for readers.

Fully explain the quote or focus of each point.

In reflective writing, you are usually asked to share your experiences in relation to something–a perspective in a text, learning about writing, the first-year experience, a summer internship, etc. When introducing this focal point, make sure you fully explain it. That is, explain what you think the quote means and provide a little summary for context. Or, if you’re reflecting on writing skills learned, before you jump to your learning and growth, stop to explain how you understand the writing skill itself–”what is analysis?,” for example. Usually, you want to fully explain the focus, explain your personal experiences with it, and then return to the significance of your experiences.

Use “I” when appropriate.

Often, in high schools, students are taught to abandon the first-person subject altogether in order to avoid over-use. However, reflective writing requires some use of “I.” You can’t talk about your experiences without using “I”! That being said, we’ve saved this advice for the bottom of the list because, as we hope the above tips suggest, there are a lot of important things that likely need explaining in addition to your personal experiences. That means you want to use “I” when appropriate, balancing your use of “I” with your explanation of the theory, quote, or situation you were in, for example.

Reflection conclusions can look forward to the future.

In the conclusion, you may want to ask and answer questions like:

- What is the significance of my experiences with X?

- What did I learn from reflecting on my experiences with Y?

- How might this reflective work inform future decisions?

- What specific tools or strategies did this activity use that might be employed in the future? When and why?

Write the reflection introduction last.