JFK Assassination Records

Findings on MLK Assassination

- Biography of James Earl Ray

- The committee's investigation

- Dr. King was killed by one shot fired from in front of him

- The shot that killed Dr. King was fired from the bathroom window at the rear of a roominghouse at 422 1/2 South Main Street, Memphis, Tenn.

- James Earl Ray purchased the rifle that was used to shoot Dr. King and transported it from Birmingham, Ala., to Memphis, Tenn., where he rented a room at 422 1/2 South Main Street, and moments after the assassination, he dropped it near 424 South Main Street

- It is highly probable that James Earl Ray stalked Dr. King for a period immediately preceding the assassination

- James Earl Ray fled the scene of the crime immediately after the assassination

- James Earl Ray's alibi for the time of the assassination, his story of "Raoul," and other allegedly exculpatory evidence are not worthy of belief

- James Earl Ray knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily pleaded guilty to the first degree murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- The Q64 bullet was a .30-06 caliber bullet of Remington-Peters manufacture.

- The bullet was imprinted with six lands and six grooves and a right twist by the rifle from which it had been fired.

- The Q2 rifle-had general class characteristics of six lands and six grooves with a right twist.

- The cartridge case (Q3) found in the Q2 rifle had been fired in the Q2 rifle.

- The damage to Dr. King's clothing, when tested microscopically and chemically, revealed the presence of lead from a disintegrating bullet and also revealed the absence of nitrites (the presence of nitrites would have indicated a close-range discharge).

- The damage to the clothing was consistent with the caliber and condition of the Q64 bullet. (51)

STAFF COUNSEL. ...[W]hen you first heard the bulletin that Dr. King had been shot did you in your mind then realize that this had nothing to do with you or Raoul?

RAY. I didn't even pay too much attention to that. There was another bulletin, and I listened to it, and I think music was on before it, and--

STAFF COUNSEL. But his question is that, when you heard that, did you at least then assume that that must have been what the police car was blocking the--

RAY. No, no there was no connection there whatsoever. (85)

STAFF COUNSEL. Well, that's what I'm trying to pinpoint-- when you started to think Raoul may be involved in the shooting of Dr. King, what was it you were thinking of? It can't be the broadcast about the car, it's got to be some other things, and what were they?

RAY. Well, of course, the guns was always a consideration. I thought that when I, I first pulled out of the area in the car, but I hate to keep getting back to this same thing, but that Mustang was what really concerned me.

STAFF COUNSEL. That's why you wanted to get out of there, but I'm trying to find out what is it that made you decide or think Raoul may be involved in the shooting of King?

RAY. Well, I think it was his association with the Mustang, he was in the general area, and, of course, the guns.... (88)

RAY. ...The assumptions were step by step. The first assumption I made was when they started looking for the Mustang, was that they were looking probably for me. If they were looking for me, then the next assumption was that they might have been looking for this Raoul, and there may have been some offense committed in this area. (89)

- Ray's alibi

- Conflicting descriptions of Raoul

- Absence of witnesses to corroborate Raoul's existence

- The rifle purchase

- Fingerprints on the rifle

- Rental of room 5-B at Bessie Brewer's roominghouse

- The binocular purchase

- Grace Walden Stephens

Chairman STOKES. All I want to know is why you didn't tell this man [Hanes] who is representing you in a capital case the truth.

RAY. It wasn't I wasn't telling you the truth; I just didn't tell him that. It was my intention to tell the jury that.

Chairman STOKES. You were going to spring this on your attorney at the trial?

RAY. Yes; that's correct. (97)

Congressman EDGAR. Can you tell the committee why you told this false story with such serious implications to the National Enquirer and also to Mark Lane?

Mr. COWDEN. Yes. Renfro Hays was a fellow that supported me for a period of about 4 months, completely, while I was unemployed. He befriended me in that he gave me food and lodging and he had the great ability to, you know, let you know, make you feel like that you really owed him something, you know, and really what he was trying to do was sell the movie rights, a book, I believe. There were several things that he mentioned from time to time that he was trying to market, and he would call on me, especially with Mark Lane and some other people that came by to talk to me from time to time, with basically this same story. This story--I don't remember how many of us, not only Mark Lane and the National Enquirer, but this was to five or six different people. I do not know who they represented, what publication. (99)

STAFF COUNSEL. What did he do? How did he decide that it was OK? What did he do with the rifle?

RAY. I really couldn't say, he just looked at it and that was it.

STAFF COUNSEL. When you say he looked at it, ah, how did it, what did he do?

RAY. Well he just checked it over and that was it. Just like you check a rifle over I guess, you---

STAFF COUNSEL. Well, I wasn't there, how did he check it over?

RAY. Well he checked the mechanism and every--I don't remember all the details, maybe he checked the mechanisms I think and just give it cursory glance and that would be it.

STAFF COUNSEL. Did he check, pick it up and check the weight to see if it, how heavy the rifle was?

RAY. I think he just said this was, this will do or something of that order.

STAFF COUNSEL. When you say he checked the mechanism, how did he check the mechanism?

RAY. I don't recall, see I don't, I don't have the least idea on what the mechanism was all about.

STAFF COUNSEL. Well he took it out, did he take it out of the box?

RAY. Ah, yes I think it was in the box, yes.

STAFF COUNSEL. And he took it out of the box?

RAY. Yes, it was taken, it was taken out of the box and looked at yes.

STAFF COUNSEL. Now he did that, Raoul?

STAFF COUNSEL. Did you lift it and check the weight and check the sight and look through the magnifying mechanism?

RAY. No, I, no the only time I looked at it, and I looked at it quite a bit when I first purchased it. I wanted to try to give the guy the impression that I knew what I was doing. But after that I never did touch it. There was never any touching of the sights or checking the mechanism or anything like that.

STAFF COUNSEL. From the time you purchased that rifle in Aeromarine, that was the last time that you touched the rifle?

RAY. Ah, yes, I would say so.

STAFF COUNSEL. And then after that Raoul picked up the rifle and checked it out at, at the motel in Birmingham, is that right?

STAFF COUNSEL. And then how did it get back into the package?

RAY. Well he must of put it there.

STAFF COUNSEL. And then he left the package with you?

RAY. Yes. (144)

He mentioned that if he were not in a room at the South Main Street address when I arrived he would be in a bar and grill located on the ground floor of the building .... (149)

Chairman STOKES. Well, when you got there you didn't know whether he had taken a room in the name of John Willard or not then, did you?

Mr. RAY. No, I didn't know whether he had or not.

Chairman STOKES. And you didn't inquire, did you?

Mr. RAY. No, I didn't make any inquiries.

Chairman STOKES. So you just went right in, furnished your name as John Willard and got a room, even though he might have still been there already ahead of you and gotten that room?

Mr. RAY. He very well could have, yes. (151)

...it was a matter of standard operating procedure for record of arrest to be filed with respect to each person who was diagnosed by a staff physician to be dangerous to himself or others and to be in need of admission for psychiatric treatment.

...the judicial commitment of Grace E. Walden was handled no differently than hundreds of other judicial commitments handled by me over my 13-year tenure. (175)

The treatment and medication afforded Walden were, in general consistent with her diagnosis and fell well within the acceptable standard of psychiatric care. In addition, according to an examination of her records, Walden's medical history was consistent with her subsequent diagnosis. (180)

The numerous conflicting descriptions of what she saw or did not see on April 4, 1968;

The evidence indicating there was nothing sinister in her commitment to John Gaston or Western State hospitals; and

That her commitment was in no way related to her role as a possible witness in the King assassination investigation;

- Irreconcilable conflicts of interest of Foreman and Hanes

- Foreman's failure to investigate the case

- Coercion by Foreman and the Federal Government

- Ray's belief a guilty plea would not preclude a new trial

The COURT. You are entering a plea of guilty to murder in the first degree as charged in the indictment as a compromise and settling your case on an agreed punishment of 99 years in the State penitentiary. Is that what you want to do?

ANSWER. Yes, I do.

The COURT. Is this what you want to do?

ANSWER. Yes, sir.

The COURT. Do you understand that you are waiving which means you are giving up a formal trial by your plea of guilty although the laws of this State require the prosecution to present certain evidence to a jury in all cases on pleas of guilty to murder in the first degree by your plea of guilty you are also waiving [the court explains Ray's rights in great detail] ...Has anything besides this sentence of 99 years in the penitentiary been promised to you to plead guilty? Has anything else been promised to you by anyone?

ANSWER. No, it has not.

The COURT. Has any pressure of any kind by anyone in any way been used on you to get you to plead guilty?

ANSWER. No, no one in any way.

The COURT. Are you pleading guilty to murder in the first degree in this case because you killed Dr. Martin Luther King under circumstances that would make you legally guilty of murder in the first degree under the law as explained to you by your lawyer?

ANSWER. Yes, legally yes.

The COURT. Is this plea of guilty to murder in the first degree with an agreed punishment of 99 years in the State penitentiary free, voluntarily and understandingly made and entered by you?

The COURT. Is this plea of guilty on your part the free act of your free will made with your full knowledge and understanding of its meaning and consequences?

ANSWER. Yes, sir. (188) 23

Considering "all of the relevant circumstances" surrounding Ray's plea ...we agree with the district court that the plea was entered voluntarily and knowingly. As stated, Judge Battle very carefully questioned Ray as to the voluntariness of his plea before it was accepted on March 10, 1969. Ray specifically denied at that time that anyone had pressured him to plead guilty .... (197)

Irreconcilable conflicts of interest involving his attorneys, Percy Foreman and Arthur Hanes, Sr.;

Inadequate investigation by Foreman, Ray's chief defense counsel at the time of the guilty plea; Mental coercion exerted by Foreman and the Federal Government to force Ray to plead guilty; and Ray's belief that his guilty plea would not preclude his ability to secure a subsequent trial.

That the FBI threatened to have his father arrested and returned to a prison he had escaped from 40 years earlier; (249)

That the FBI burglarized the home of his sister, Carol Pepper; (250)

That his brother, John Ray, had been sentenced to 18 years for bank robbery, an excessive sentence compared to those of his codefendants; (251)

That Foreman told him that his brother, Jerry Ray, would be arrested and charged with conspiracy in the assassination if Ray did not plead guilty; (252) and That Foreman tried to induce members of Ray's family to convince him he should plead guilty. (253)

Find anything you save across the site in your account

My Life in the Aftermath of Martin Luther King’s Assassination

The last time Martin phoned me, on the day of his assassination, the call came into my office in New York. I knew him so well that I figured I could anticipate the purpose for his call. He was in Memphis with Andrew Young and the Reverend Billy Kyles, going over the details of his schedule. I expected that he wanted to make sure he knew exactly when I’d be arriving in town to assist him. It was a matter of logistics—clerical stuff, really—and I was buried in other work. I shouted to my secretary, “Tell him I’ll be there on time.”

“You don’t want to speak with Dr. King?” she asked.

Not really; I’d had this conversation many times before. “Just let him know I need someone to pick me up at the airport. I’ll be there on time.”

And thus, I missed my chance at goodbye.

Later, a verse from the Book of Matthew would repeat itself in my mind: “The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ ”

Martin did the most for the least. And everything we did for him was the least we could do. The day after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy , I had met Martin at LaGuardia Airport. He had stepped out of the jetway, shaking his head. “See, if they can kill the President of the United States, Clarence, then you and all the others might as well stop worrying about the fantasy that I can be protected,” he had said.

We didn’t ever stop worrying, but he was right.

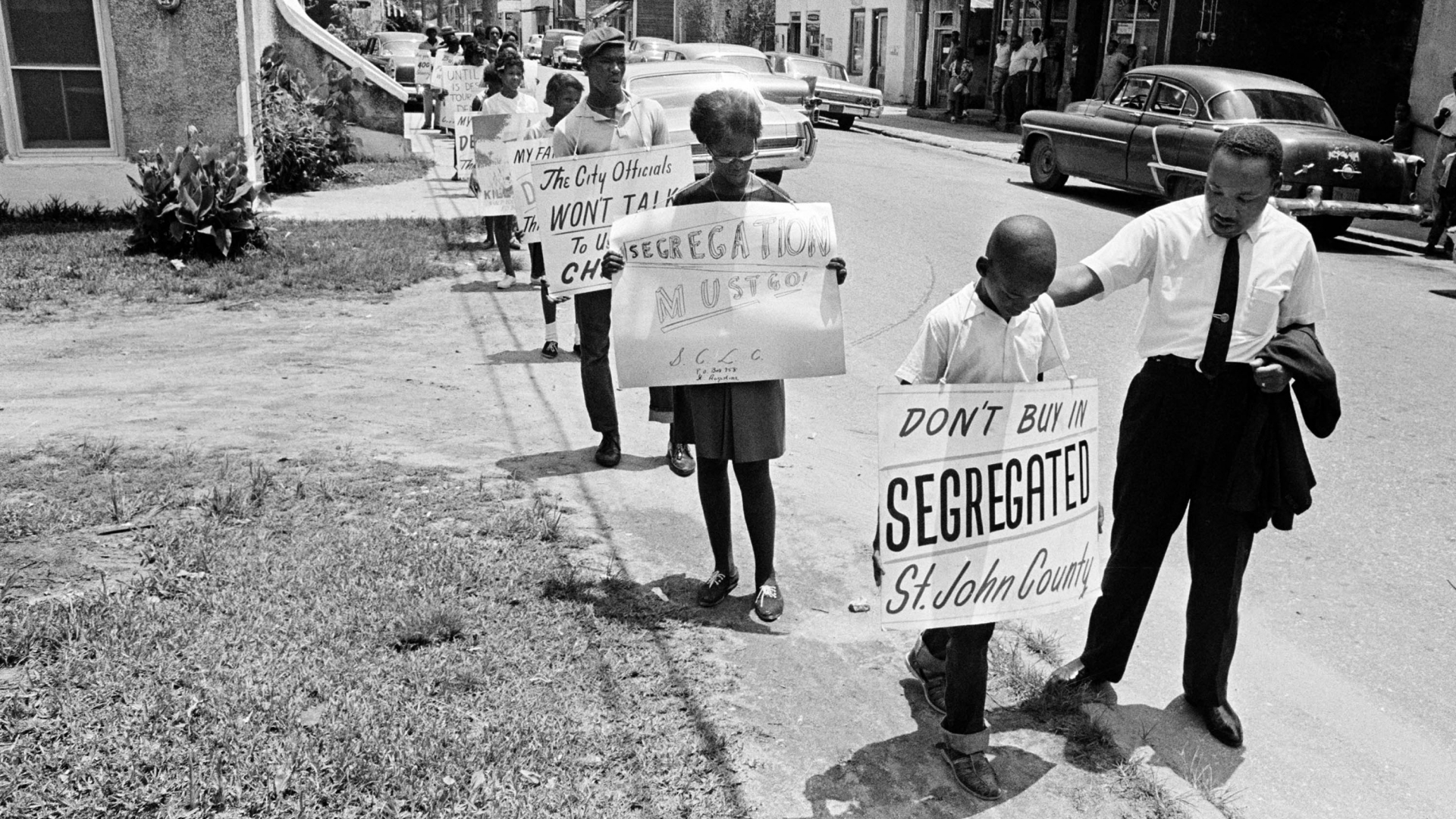

February, 1968, was rough for the city of Memphis, Tennessee. On the first of the month, two members of the mostly Black Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees were crushed to death in the faulty trash compactor of their own garbage truck. Two weeks later, the union members staged a work stoppage, protesting the city’s lack of urgency in dealing with outdated equipment and dangerous working conditions. Before long, by the city’s count, nine hundred and thirty of a thousand and one hundred sanitation workers and two hundred and fourteen of two hundred and thirty sewage and drainage workers refused to show up for work. Garbage piled up in the streets, and the mayor, the stubborn former head of the Department of Public Works (a role in which he had overseen sanitation workers), was not interested in negotiation. He brought in white strikebreakers, and the animus intensified.

Dr. King wanted to go to Memphis in support of Local 1733. I opposed the idea—not on principle but because I had already scheduled several meetings that month in Manhattan to broker introductions with generous donors, introductions that Martin had repeatedly asked me to arrange. Moreover, the relationship between the striking African American garbage workers and the city of Memphis had become increasingly bitter.

Roy Wilkins, the executive director of the N.A.A.C.P. ; Bayard Rustin; and Billy Kyles convinced Martin that his presence in Memphis would be invaluable to the cause. So he went. On March 18th, he marched with the sanitation workers, and he planned to march with them again four days later, but the union postponed its second demonstration because of an unseasonable snowstorm. On the 28th, the workers resumed their march. This time, riots erupted. Amid the tumult, a police officer shot and killed Larry Payne, an unarmed sixteen-year-old boy. In the wake of that horror, the mayor called in the National Guard.

Martin showed no signs of leaving Memphis anytime soon, but I needed to prep him for the meetings, so I planned a trip to Memphis myself. My flight was scheduled to land in the evening of April 4, 1968. I was packing for the trip when my home phone rang. I was running late, and though my first impulse was to ignore the call, I answered.

Harry Belafonte was on the line. “I can’t talk now,” I told him. “I’m jumping in a cab for the airport.”

“Turn on the TV,” Harry said, “Martin’s been shot.” He hung up the phone.

I turned on the television that I kept in the bedroom. Walter Cronkite was reporting breaking news that echoed Harry’s words. “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., has been shot,” Cronkite said.

I was stunned. I picked up the phone again and started calling my contacts in Memphis. One after another, every line was busy. A cold resignation swept through me. They finally got him.

I managed to reach Harry by phone again. “Am I getting on the plane?” I asked. We discussed the possibility, and we agreed that I could do more from my home, coördinating with our colleagues in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.), some of whom were in Memphis, but most of whom were still in Atlanta.

In the following hours, I was lost in the daze that often accompanies a sudden death. There was so much to be done. A practiced responsibility guided my movements, and my mind was occupied with plans and logistics, displacing grief. I tried to help from New York, making calls and introductions, responding to press inquiries. But it quickly became apparent that I needed to be down South, so Stanley Levison and I travelled to Atlanta to meet up with Harry.

The next few days were a tangle of duties and obligations.

There wasn’t a moment to waste on reflection. I held myself steady, assisting the family in planning the funeral, along with Harry and Stanley. Both men had long offered such stalwart support in Martin’s life and work—one, out front, the other, in the shadows—and here, at the end, they did everything they could to continue that legacy.

Together, the three of us tried to unburden Martin’s widow, Coretta, as much as possible. The Kings’ living room in Atlanta doubled as a command post. Planning the funeral was an enormous undertaking: there were questions about controlling the crowd, managing the media frenzy, selecting the pallbearers, deciding who might preside over the service itself. We were even worried about the safety of the funeral party and mourners—my friend Martin was a much more divisive figure during his lifetime than the man memorialized on library buildings and freeways today. In fact, the racist governor of Georgia refused to let Martin’s body lie in state, and he even kept the flag flying at full staff, until a federal mandate ordered him to lower it.

One day, Xernona Clayton, a Black female journalist and a member of the S.C.L.C., came to the house holding a bundle of clothes. She had gone to a store downtown, to pick out some outfits for Coretta so that she would have appropriate clothing to wear in the next few days and, of course, to Martin’s funeral. She had left the store with the bill unpaid, promising to return, she told us. Harry, Stanley, and I all took out our cards and handed them to Xernona, telling her to split the charges up among all three. “And, if there’s any problem,” I told her, “have the clerks call here for approval.”

Coretta liked the selection, and Xernona returned to the store to pay for them. We didn’t hear from anyone, and when Xernona returned, she gave us back our cards. The shopkeeper had refused payment, wanting to support the King family in their time of grief, Xernona said.

The day before the funeral, I received a call from William vanden Heuvel, a good friend of mine and a close friend to the Kennedy family. He told me that he was calling on behalf of Jacqueline Kennedy . The former First Lady would be attending the funeral, and she wanted to visit Coretta beforehand. Bill and I coördinated the details, and, on the eve of the funeral, I met Mrs. Kennedy at the door, escorting her into the private area off the dining room where Coretta had been spending most of her time.

“Coretta,” I said. “I have someone who wants to give her condolences.” The world’s second most famous widow turned to face the first. It was certainly no pleasure, but it was a surreal kind of honor to introduce two of America’s most prominent victims of political violence to each other.

In the days after the funeral, I returned to New York and tried to resume my work. With the planning behind me, I struggled to ignore a question that resurfaced in my mind again and again: Can you really live in a country that allowed something like this to happen?

I tried to reckon with the bitter heartbreak, but I fell short.

Soon, I began refusing some calls from the S.C.L.C. On other occasions, I called people there, and my messages went unreturned. As the weeks passed, I began to see my relationship with the movement differently: although I knew I had been inspired by Dr. King, I had never really understood—until circumstances forced me to understand—that I was really working only for the man. Dr. King had sculpted the S.C.L.C. mission, and I believed in that mission. But the nature of things became clear: the S.C.L.C. was an organization, not much better than most organizations, rife with ego, posturing, sabotage, blame, angst over employment and salary and status. In short, it was a group of people—well-intentioned as they might have been—who acted as people do when they are at work. Some organizations succeed at the nuts-and-bolts level, and others are meant to rise or fall with a “key man.” In the case of the S.C.L.C., Martin was the magic.

And, within the grander scope of the civil-rights movement, Martin had his enemies: those who were jealous of his influence, his presence on the national stage. And I was his man. Now persona non grata. Fine with me. I became so angry, I lost all interest in the S.C.L.C. version of the movement. There was nothing anybody could do. I was tired of giving and getting nowhere. I pulled away, retreating north, where I felt I really belonged, to a life that I decided would be more self-centered.

A return to form, I suppose.

I also believed that the American government had allowed Martin’s death to happen. His shift in focus—from demanding desegregation to demanding economic parity and an end to the unjust slaughter overseas—had led to his assassination. If worrying about Black folks, in 1963, made him the most dangerous Negro leader in the country, just imagine what the government thought of him by the time he was at Riverside Church, criticizing the President of the United States over the war in Vietnam .

Throughout the summer of 1968, I strongly considered becoming a militant. I could imagine taking up arms against the government. If you could do this to Martin King, who stood for nothing but peace and dignity, if you could bring your copper-jacketed tools of destruction and oppression to bear on such a man, maybe I’ll do the same thing to you. Why not join the Black Panthers ? Why not learn to make a bomb? Why not arm myself to the teeth and burn the whole motherfucker down?

In 2015, I met with James Comey , then the director of the F.B.I., for an hour in his office in Washington, D.C. We spoke about many things, including the assassination. He showed me what was beneath the glass on his desk: a photocopy of a memorandum from the former F.B.I. director J. Edgar Hoover , requesting authorization from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to wiretap Dr. King, and Kennedy’s authorization to do so. Comey kept a copy in plain sight, he said, so that, when his agents visited him in the office, they could be reminded of what the F.B.I. should not do.

I thought of Martin’s funeral. The procession stretched three miles long; the casket was placed on the back of a farm wagon pulled by mules. The eulogy was Martin’s own voice, prerecorded, delivering a sermon on how he should be remembered—asking that no one mention awards and honors but only the simple good he tried to do.

Mahalia Jackson, always Martin’s favorite, sang “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” Later, there was a chorus of “We Shall Overcome.”

I didn’t think we would. Not this time.

There is a color picture from the funeral that I come across occasionally: Harry Belafonte, eyes rimmed red, right next to Coretta at Martin’s funeral. Fifty-five years have passed since that day; Martin’s been dead much longer than he was ever alive, and Harry died in April, never taking enough credit for the work that he did for the cause. And then here I am, nearing the age of ninety-three: the only one of the three left standing.

In time, I’ve come to terms with the assassination, but I’ve never come to peace with it. For years, my grief made me selfish and self-destructive. Long gone are the days when I considered domestic terrorism, but the pain still runs as deep now as it did then. After some time, I realized that to turn my back on the struggle would be to turn my back on Dr. King.

I never worked with the S.C.L.C. again, but I did get involved in politics, becoming a New York State delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention. In the early seventies, I invested in one of America’s oldest and most influential Black papers, the New York Amsterdam News , and I tried to protect prisoner rights as a negotiator during the Attica uprising. I did my best to elevate Black culture, working to restore Harlem’s Apollo Theatre and build a network of Black radio stations.

And I’ve continued to bear witness to Martin’s life and character. There’s an African saying that I often reflect upon when I think about his legacy and my own part in his movement: if the surviving lions don’t tell their stories, the hunters will take all the credit. ♦

This is drawn from “ Last of the Lions . ”

New Yorker Favorites

As he rose in politics, Robert Moses discovered that decisions about New York City’s future would not be based on democracy .

The Muslim tamale king of the Old West .

Wendy Wasserstein on the baby who arrived too soon .

An Oscar-winning filmmaker takes on the Church of Scientology .

The young stowaways thrown overboard at sea .

Fiction by Jhumpa Lahiri: “ A Temporary Matter .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The Event, Key Dates, and Description Key Individuals Involved

Public opinion of the event, effects of the event.

Martin Luther King Jr. was the leader of the civil rights movement in the United States. He led the fight for civil rights by example, speaking to the public and organizing massive peaceful protests. Despite the arrest and imprisonment of King Jr.’s direct killer, James Earl Ray, the potential sponsors of the murder have never been identified. It is logical to assume that these were people who had power and who were against the changes that the victory of the civil rights movement promised.

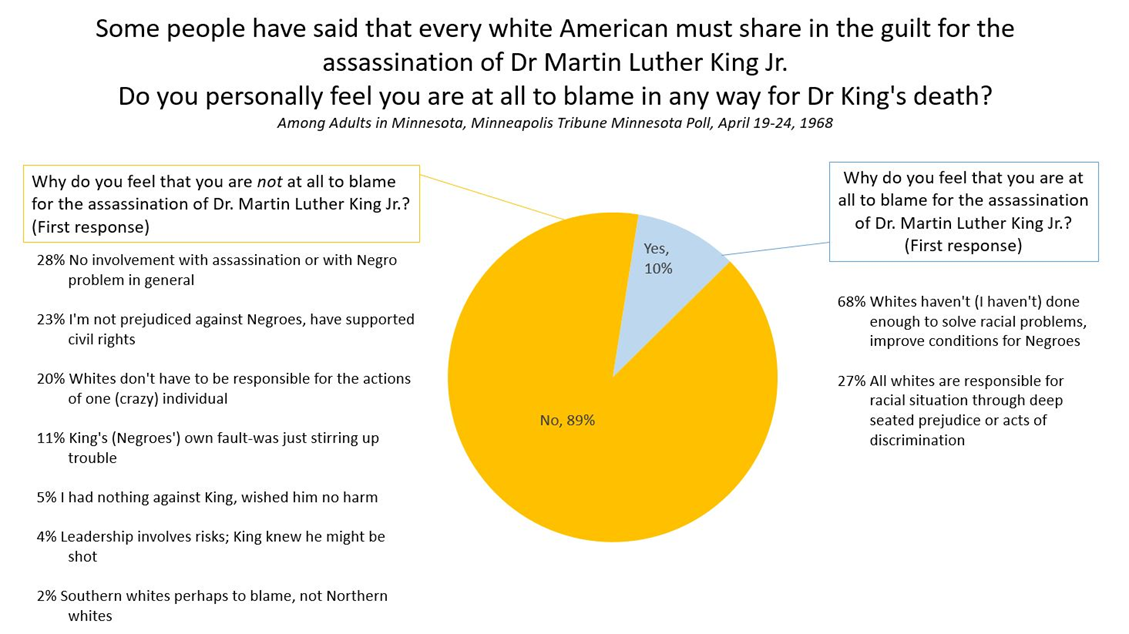

Of the 10% of Minnesota survey participants who felt guilty or responsible, 68% said that whites or they themselves did not do enough to address racial issues and improve conditions for the Negroes (“Assassination Nation,” 2018). Another 27% believed that all whites were responsible for the situation because of the prejudice and acts of racial discrimination prevailing in society. Survey participants who did not consider themselves involved, guilty or responsible for King’s death stated that “no involvement with assassination or with Negro problem is general” (28%), “I am not prejudiced against Negroes, have supported civil rights” (23 %), and “King’s (Negroes’) own fault was just stirring up trouble” (11%) (“Assassination Nation,” 2018, par. 5).

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. dealt a blow to the ideology of nonviolence and love that underpinned King’s philosophy and which he sought to make basic ideas for the civil rights movement. Congress for Mass Equality Director Floyd McKissick made the famous speech on the night after King’s assassination that “racial equality is a dead philosophy because it was killed by white racists” (Love, 2021, par. 7). Some civil rights advocates such as Stokely Carmichael suggested that the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., who encouraged the movement for nonviolent marches and tried to teach the people to show love and compassion, made a big mistake. According to Carmichael, in this way, the killers declared war on the members of the movement, among whom there were no others like Martin Luther King Jr.

Assassination Nation: Public Responses to King and Kennedy in 1968 . (2018). Web.

Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr . (2021). Web.

Love, D. (2021). What impact did King’s assassination have on the Black community? Web.

- Academic Reforms of George W. Bush

- Milton Friedman's Biography and Achievements

- Leadership Lessons From Martin Luther King Jr.

- The Emergence and Popularity of the "Black Power" Slogan

- Martin Luther King, Jr.: Leadership Analysis

- Monograph of Winston Churchill

- Eberhardt Becoming a Player in French Imperial Politics

- Researching of Mark Zuckerberg’s Creativity

- Traits of an Effective Leadership in Practice

- Latin American Studies: Fernando Ortiz

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, October 29). Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination. https://ivypanda.com/essays/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-assassination/

"Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination." IvyPanda , 29 Oct. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-assassination/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination'. 29 October.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination." October 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-assassination/.

1. IvyPanda . "Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination." October 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-assassination/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination." October 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-assassination/.

njcssjournal

social studies

The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and its Impact

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and Its Impact

by Megan Bernth with Kyle Novak

The life, ideas, and achievements of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. enter the curriculum during an examination of the African American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s or if a school commemorates his birthday or Black History Month. Reverend King’s impact on the United States continued after he was assassinated on April 4, 1968 because his ideas lived on and his achievements continued to influence people. His assassination also contributed to the racial divide in the United States, as African American communities exploded in anger. The material in this curriculum package focuses on the immediate response to his murder, testimonials and rioting, controversy about his killer, and King’s long-term legacy. Material in the package includes photographs, videos, quotes, and compelling questions. As a culminating activity, the students read three quotes statements by Reverend King that discuss his ideas of nonviolence and passive civil resistance, compare them to examples of contemporary protests, and consider the implications of Reverend King’s ideas for today.

Background: In early April of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was visiting Memphis, Tennessee to support a sanitation workers’ strike. He had faced mounting criticisms from young Blacks who thought his nonviolent attitude was doing their cause a disservice. It was because of these criticisms he had begun moving his support beyond blacks to all poor Americans and those who opposed the Vietnam War. While standing on a balcony the evening of April 4, a sniper shot and killed him. James Earl Ray was eventually arrested and convicted of the crime.

Martin Luther King Is Slain in Memphis; A White is Suspected; Johnson Urges Calm

By Early Caldwell, New York Times , April 5, 1968, p. 1

Memphis, Friday, April 5 – The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who preached nonviolence and racial brotherhood, was fatally shot here last night by a distant gunman who raced away and escaped. Four thousand National Guard troops were ordered into Memphis by Gov. Buford Ellington after the 39-year-old Nobel Prize-winning civil rights leader died. A curfew was imposed on the shocked city of 550,000 inhabitants, 40 per cent of whom are Negro. But the police said the tragedy had been followed by incidents that included sporadic shooting, fires, bricks and bottles thrown at policemen, and looting that started in Negro districts and then spread over the city.

Police Director Frank Holloman said the assassin might have been a white man who was “50 to 100 yards away in a flophouse.” Chief of Detectives W.P. Huston said a late model white Mustang was believed to have been the killer’s getaway car. Its occupant was described as a bareheaded white man in his 30’s, wearing a black suit and black tie.

A high-powered 30.06-caliber rifle was found about a block from the scene of the shooting, on South Main Street. “We think it’s the gun,” Chief Huston said, reporting it would be turned over to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Dr. King was shot while he leaned over a second-floor railing outside his room at the Lorraine Motel. He was chatting with two friends just before starting for dinner. Paul Hess, assistant administrators at St. Joseph’s Hospital, where Dr. King died despite emergency surgery, said the minister had “received a gunshot wound of the right side of the neck, at the root of the neck, a gaping wound.” In a television broadcast after the curfew was ordered here, Mr. Holloman said, “rioting has broken out in parts of the city” and “looting is rampant.” Dr. King had come back to Memphis Wednesday morning to organize support once again for 1,300 sanitation workers who have been striking since Lincoln’s Birthday. Just a week ago yesterday he led a march in the strikers’ cause that ended in violence. A 16-year-old Negro was killed, 62 persons were injured and 200 were arrested.

Policemen were pouring into the motel area, carrying rifles and shotguns and wearing helmets. But the King aides said it seemed to be 10 or 15 minutes before a fire Department ambulance arrived. Dr. King was apparently still living when he reached the St. Joseph’s Hospital, operating room for emergency surgery. He was borne in on a stretcher, the bloody towel over his head. It was the same emergency room to which James H. Meredith, first Negro enrolled at the University of Mississippi, was taken after he was ambushed and shot in June 1965, at Hernando, Miss., a few miles south of Memphis; Mr. Meredith was not seriously hurt.

- What does the New York Times report in the headline?

- How is Dr. King described in the article?

- In your opinion, why did cities declare curfews following Dr. King’s assassination?

- Why was Dr. King in Memphis?

President’s Plea, On TV, He Deplores “Brutal” Murder of Negro Leader

New York Times , April 5, 1968, p. 1

President Johnson deplored tonight in a brief television address to the nation the “brutal slaying” of the Re. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He asked “every citizen to reject the blind violence that has struck Dr. King, who lived by nonviolence.” Mr. Johnson said he was postponing his scheduled departure tonight for a Honolulu conference on Vietnam and that instead he would leave tomorrow. The President spoke from the White House. At the Washington Hilton Hotel, where Democratic members of Congress had gathered to honor the President and Vice President, Mr. Humphrey, his voice strained with emotion, said: “Martin Luther King stands with other American martyrs in the cause of freedom and justice. His death is a terrible tragedy.”

- How did President Johnson react to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.?

- Why did Vice President Humphrey describe Dr. King as one of the “American martyrs in the cause of freedom and justice”?

A Conversation with Dr. King

- Where do the ideas of non-violent civil disobedience come from?

“From the beginning a basic philosophy guided the (civil rights) movement. This guiding principle has since been referred to variously as non-violent resistance, non-cooperation, and passive resistance. But in the first days of protest none of these expressions were mentioned; the phrase most often heard was “Christian love.” . . . It was Jesus of Nazareth that stirred the Negroes to protest with the creative weapon of love. As the days unfolded, however, the inspiration of Mahatma Gandhi (a leader in the struggle for independence in India) began to exert its influence. I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was of the most potent (powerful) weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom.”

- When is civil disobedience necessary?

“There is nothing wrong with a traffic law which says you have to stop for a red light. But when a fire is raging the fire truck goes right through that red light, and normal traffic had better get out of the way. Or, when a man is bleeding to death, the ambulance goes through those red lights at top speed . . . Massive civil disobedience is a strategy for social change which is at least as forceful as an ambulance with its siren on full.”

- Why do you choose non-violent resistance over violence?

“To accept passively an unjust system is to cooperate with that system… Non-cooperation with evil is as much an obligation as is cooperation with good. Violence often brings about momentary results . . . But . . . It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones.”

- There was a wave of rioting in African American communities following the assassination of Dr. King. In your opinion, what would Dr. King have said to the rioters if he were alive?

- As you learn about the riots that followed the assassination of Dr. King, consider: Were the riots a legitimate response to King’s assassination?

- In your opinion, what has been the impact of the assassination of Dr. King and the riots that followed on American society?

Race Riots following the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (April 5-9, 1968)

Background: In the week following the death of Dr. King, riots broke out across the country. It is important to note that while Dr. King’s death may have sparked the riots, the long-standing history of racial tensions and conflicts had created an environment where violent protests were widely accepted in the wake of King’s assassination. President Johnson urged Americans to “reject the blind violence” that had killed King. Despite the President’s pleas, violence erupted and tens of thousands of National Guard, military and police officers were called on to quell the riots. By the end of the week, more than 21,000 were arrested and 2,600 injured, with 39 dead. With economic damages estimated to reach at least $65 million, entire areas and communities were destroyed. Of the 125 cities affected, Washington, Chicago and Baltimore were three that stand out amongst the rest.

Video : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TZ_5FmnSMs

Washington D.C.

Eyewitness to the Riot

Virginia Ali (a black woman who owned a restaurant with her husband in Washington): “I remember the sadness more than anything else. The radio stations were playing hymns, and people were coming in crying. People were out of control with anger and sadness and frustration. They broke into the liquor store across the street and were coming out with bottles of Courvoisier. They had no money, these youngsters. They were coming into the Chili Bowl saying, “Could you just give us a chili dog or a chili half smoke? We’ll give you this.”

George Pelecanos (an eleven-year-old black boy living in Washington): “The biggest mistake on the administrative side was not closing the schools and the government on Friday. Fourteenth Street had burned down, and officials thought it was over. But overnight, people all over the city had started talking about what was going to happen the next day. It got around by what they called the ghetto telegraph – the stoop, the barbershops, the telephones. Very early in the morning, the teachers and school administrators started freaking out because the students were out of control – they just started to walk out. People realized: This isn’t over. It’s just beginning, and we have to get out of here.”

- Describe the scenes shown in the video. Which scene is the most powerful? Why?

- How are the rioters portrayed in the video?

- How do the people interviewed remember the riot forty years later?

- According to Georg Pelecanos , what was the biggest mistake by authorities?

- In your opinion, does Ali’s quote provide a possible explanation for the riots?

- After examining the video, the quotes, and the photographs, which source do you think provides the most accurate representation of the riots? Why?

Baltimore, Maryland

Ruby Glover (a Jazz singer and administrator at Johns Hopkins Hospital) – “It looked like everything was on fire. It appeared that everything that we loved and adored and enjoyed was just being destroyed. It was just hideous.”

James Bready (editorial writer for the Evening Sun) – “We drove along North Avenue, and I remember seeing kids running along from store to store with lighted torches to touch them off. But nobody ever tried to stop the car or interfere with us. I think black people felt release after generations of ‘You mustn’t do this, you mustn’t go there, you can’t say that or think that.’ Suddenly, the lid was off.”

Tommy D’Alesandro (mayor of Baltimore during the riots) – “There was hurt within the black community that they were not getting their fair share. We were coming from a very segregated city during the 30’s, 40’s, 50’s – and it was still a segregated atmosphere.”

- How does Ruby Glover remember the riots?

- What is James Bready’s explanation for the riots?

- What is Tommy D’Alesandro’s explanation for the Baltimore riots?

Chicago, Illinois

- What does Richard Barnett believe is a positive outcome of these events?

- What is the “ragged adolescent army” described by Ben Heineman?

- What does Mrs. Dorsey accuse the police of doing?

Trenton, New Jersey

Carmen Armenti (mayor of Trenton during the riots): “This was something that was simmering in black communities for a while before our disturbances. It was not an easy time to be a public official. They were not good economic times, and there was high unemployment among African-Americans and a multitude of other frustrations for black people. Keeping the lid on racial strife was the top political priority in those days.”

Tom Murphy (a young police officer in Trenton): “I’ll never forget that scene as long as I live. They were really whacking them at us. The golf balls were hitting guys and smashing car windshields. You had to dive for cover. They ran him [another police office] over with a truck. He was lucky it had those high wheels like the ones on the SUVs we have today. If it was a car it would have killed him, but he only got hit in the head with that ‘pumpkin’ for the axle in the back of the truck.”

- Why does Mayor Armenti say “it was not a good time to be a public official”?

- How is Murphy’s account of the riots different from others we have read?

- How are events portrayed in The Trentonian ?

New York City and Buffalo, New York

Mayor John Lindsay: “It especially depends on the determination of the young men of this city to respect our laws and the teachings of the martyr, Martin Luther King. We can work together again for progress and peace in this city and this nation, for now I believe we are ready to scale the mountain from which Dr. King saw the promised land.”

Michele Martin (A young African American girl during the 1968 riot in conversation with her FDNY father): “Why is this happening?” “They killed King.” “Why is the supermarket on fire?” They’re mad.” “Why are they mad?” “Because they killed King.” “Why can’t we go out and play?” “There’s too much going on. Maybe when things calm down.”

David Garth (Mayoral press aide): “There was a mob so large it went across 125 th Street from storefront to storefront. My life is over. He [Lindsay] had no written speech. No prepared remarks. He just held up his hand and said, ‘this is a terrible thing,’ He just calmed people, and then this gigantic wave stared marching down 125 th Street, and somehow Lindsay was leading it.”

False Rumors Raise City’s Fears; Racial Unrest Exaggerated April 6, 1968, New York Times , pg. 1

Mayor, Quoting King, Urges Racial Peace Here; Lindsay Calls on Negroes in City to Follow Doctrine of Using Love to Fight Hate April 6, 1968, New York Times , pg. 26

VIOLENCE ERUPTS IN BUFFALO AREA; Looting and Fire Reported in Negro East Side April 9, 1968, New York Times , pg. 36

- Why did Mayor Lindsay walk the streets and discuss the “young men of the city”?

- In your opinion, why did Michele Martin’s father offer such simple answers?

- How did David Garth feel when he and the mayor faced the rioters?

Senator Robert Kennedy Speaks to the Nation

After the assassination of Reverend King, Senator Robert Kennedy interrupted his Presidential campaign to address the nation. An audio version of the speech is available on the website of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Source: https://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/RFK-Speeches/Statement-on-the-Assassination-of-Martin-Luther-King.aspx

(A) I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight. Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black–considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible–you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization–black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.

(B) Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love. For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times. My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: “In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

(C) What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black. So I shall ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King, that’s true, but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love–a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke. We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we’ve had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder.

(D) But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land. Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.

- What information does Senator Kennedy report”?

- In paragraph “B”, how does Kennedy suggest the country heal in this difficult time?

- According to Senator Kennedy, what did the United States need at this time?

- How did Senator Kennedy try to present a message of hope?

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- This Day In History

- History Classics

- HISTORY Podcasts

HISTORY Vault

- Link HISTORY on facebook

- Link HISTORY on twitter

- Link HISTORY on youtube

- Link HISTORY on instagram

- Link HISTORY on tiktok

✯ ✯ ✯ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ✯ ✯ ✯ His Life and Legacy

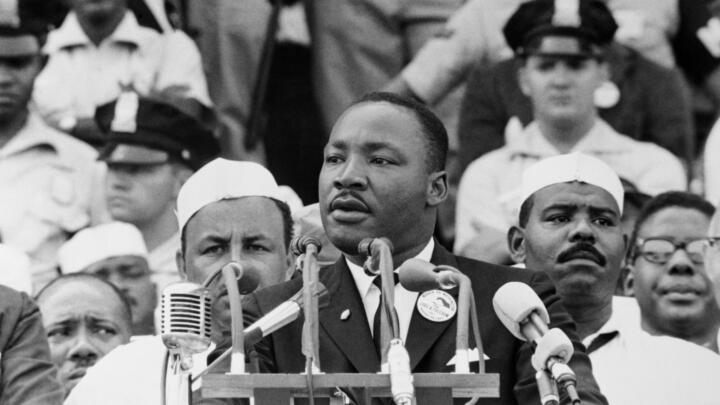

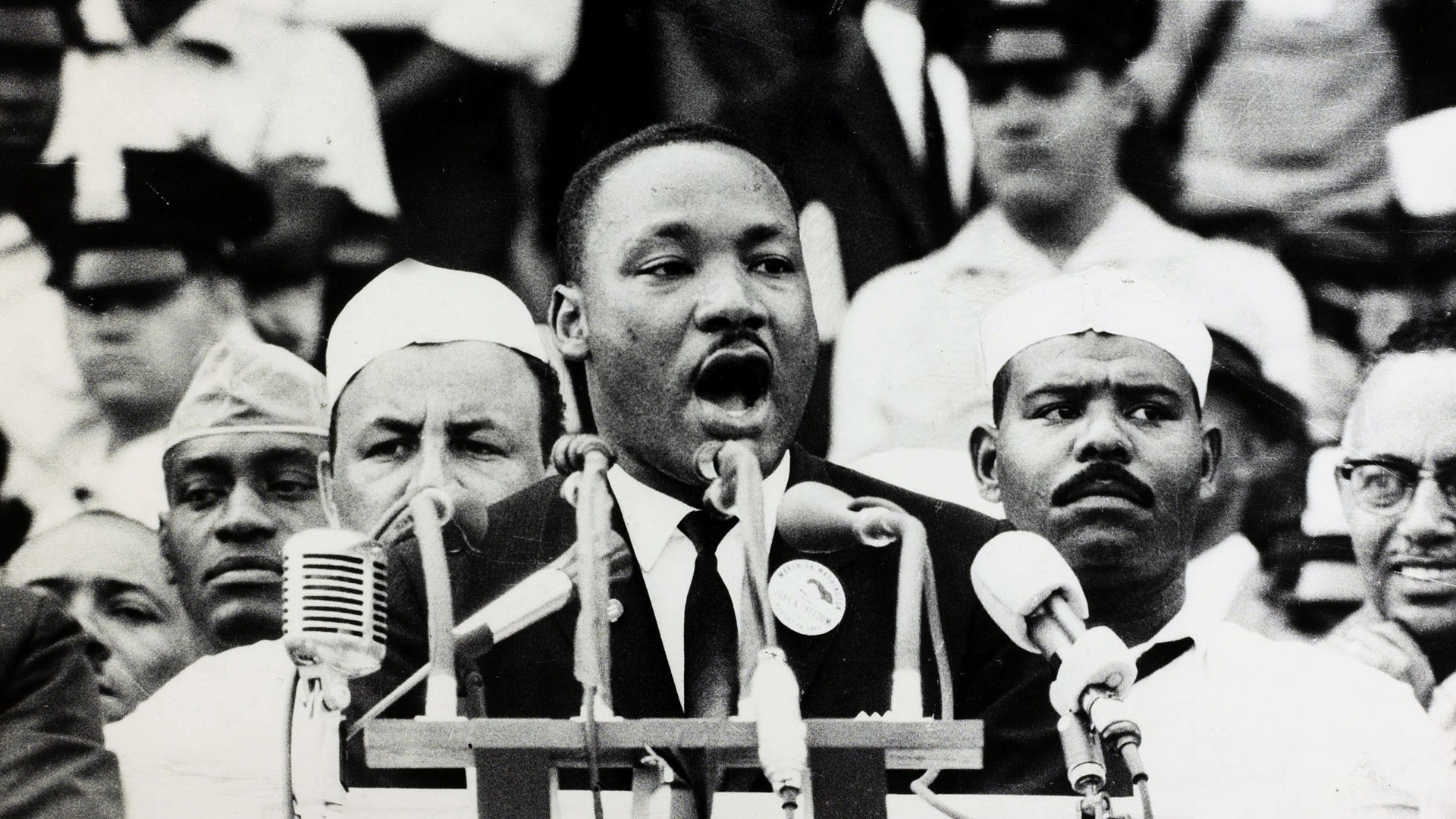

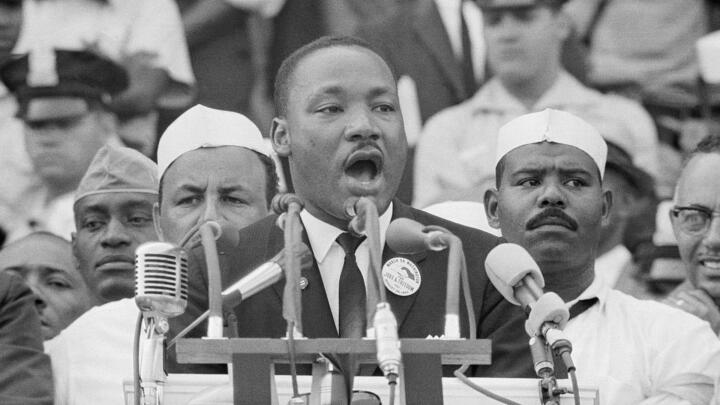

Martin Luther King Jr. dedicated his life to the nonviolent struggle for civil rights in the United States. King's leadership played a pivotal role in ending entrenched segregation for African Americans and to the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, considered a crowning achievement of the civil rights era. King was assassinated in 1968, but his words and legacy continue to resonate for all those seeking justice in the United States and around the world. As King said at the Washington National Cathedral on March 31, 1968, "Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that."

10 Things You May Not Know About Martin Luther King Jr.

An Intimate View of MLK Through the Lens of a Friend

The Fight for Martin Luther King Jr. Day

7 of Martin Luther King Jr.'s Most Notable Speeches

Martin Luther King Jr.

7 Things You May Not Know About MLK’s 'I Have a Dream' Speech

America in Mourning After MLK's Shocking Assassination: Photos

For Martin Luther King Jr., Nonviolent Protest Never Meant ‘Wait and See’

How an Assassination Attempt Affirmed MLK’s Faith in Nonviolence

Jesse Jackson on M.L.K.: One Bullet Couldn’t Kill the Movement

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Final Speech

MLK's Poor People's Campaign Demanded Economic Justice

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Famous Speech Almost Didn’t Have the Phrase 'I Have a Dream'

How Selma's 'Bloody Sunday' Became a Turning Point in the Civil Rights Movement

Playlist: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Watch the Black History collection on HISTORY Vault to look back on the history of African American achievements.

Get instant access to free updates.

Don’t Miss Out on HISTORY news, behind the scenes content, and more.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

Need help with the site?

Create a profile to add this show to your list.

Stay informed: Sign up for eNews

- Facebook (opens in new window)

- X (opens in new window)

- Instagram (opens in new window)

- YouTube (opens in new window)

- LinkedIn (opens in new window)

Martin Luther King Papers

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume V : Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959–December 1960

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume VII : To Save the Soul of America, January 1961–August 1962

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume III : Birth of a New Age, December 1955-December 1956

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume I : Called to Serve, January 1929-June 1951

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume VI : Advocate of the Social Gospel, September 1948–March 1963

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume IV : Symbol of the Movement, January 1957-December 1958

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume II : Rediscovering Precious Values, July 1951 - November 1955

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: a Turning Point in American History

This essay about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. explores the significant impact of his death on the civil rights movement and American society. It recounts the events of April 4, 1968, when King was killed in Memphis, Tennessee, and the immediate reaction of grief and violence across the United States. The essay discusses the political consequences, including the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, and the fragmentation of the civil rights movement following King’s death. It highlights King’s lasting legacy, his philosophy of nonviolence, and the continued relevance of his vision for equality and justice in addressing contemporary issues of racism and social injustice.

How it works

In addition to shocking the entire world with his untimely death, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968, marked a turning point in American history and had a profound effect on the nation’s collective consciousness. King was well-known for his leadership and support of nonviolent resistance, and he dedicated his life to fighting racial injustice and inequality.

In spite of his confession, a number of conspiracy theories have persisted over the years, suggesting that King’s assassination was part of a larger, more sinister plot.

On that fateful evening, King was shot and died while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. The African American sanitation workers were on strike against unfair treatment and poor working conditions. King’s presence in Memphis was evidence of his commitment to fighting for the rights of the oppressed, regardless of the personal risks involved. The assassin, James Earl Ray, was apprehended two months later and found guilty of the murder.

Much grief and indignation followed King’s assassination; riots and violent outbursts occurred in cities across the nation as African Americans let out their anger and frustration over the death of their leader and the injustices they still had to live with; the federal government responded by deploying the National Guard to restore order, highlighting the high level of tension that existed between the state and the black community.

In addition, King’s death had significant political ramifications: President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also called the Fair Housing Act, which attempted to eradicate housing discrimination. Although the act was viewed as a memorial to King’s legacy and a significant step toward addressing systemic racism, it did not immediately quell the unrest because many people thought that King’s vision of equality and justice had not yet been fully realized.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination had a profound long-term impact on the civil rights movement. While the movement had already advanced significantly with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, King’s death left a leadership void that was difficult to fill. The movement gradually became more fragmented, with different factions advocating for different strategies to achieve racial equality. Some groups, frustrated with the violence and lack of progress, began to adopt more militant stances, deviating from King’s nonviolent philosophy.

As the civil rights movement expanded to address issues like mass incarceration, police brutality, and economic inequality, King’s vision of a “beloved community,” where people of all races and backgrounds could live in harmony, served as a beacon for those who persisted in their quest for a more just and equitable society. King’s legacy endured, inspiring new generations of activists despite the immediate obstacles. His stirring speeches and unshakable dedication to justice served as a moral compass for later social justice movements.

In addition, King’s assassination underscored the need for ongoing dialogue and action to address racial disparities in America, serving as a stark reminder that the fight for civil rights was far from over and that true equality required constant effort and vigilance. King’s message of love, tolerance, and nonviolence remains relevant today as the nation grapples with issues of systemic racism and social injustice.

In conclusion, as we reflect on the significance of King’s life and work, we are reminded of the importance of tenacity, bravery, and compassion in the ongoing civil rights movement. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. exposed long-standing racial tensions in the United States and served as a catalyst for the ongoing fight for equality and justice. King’s legacy will always be a source of inspiration and a call to action for anyone who believes in the potential for a more just world and the power of nonviolence.

Cite this page

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History. (2024, Jul 21). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/

"The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History." PapersOwl.com , 21 Jul 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/ [Accessed: 17 Aug. 2024]

"The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History." PapersOwl.com, Jul 21, 2024. Accessed August 17, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/

"The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History," PapersOwl.com , 21-Jul-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/. [Accessed: 17-Aug-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.: A Turning Point in American History . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr-a-turning-point-in-american-history/ [Accessed: 17-Aug-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Starting Points

The Martin Luther King Assassination: Missing Pieces

by Larry Hancock & Stuart Wexler, 18 May 2009

A key factor in the investigation of Dr. King’s murder was the practice of Director Hoover and the Bureau to quickly focus FBI efforts on the physical evidence from the scene of the crime. In one sense, such a policy is perfectly understandable - it directs the resources and assets of the Bureau towards establishing the body of evidence which will be used in the prosecution of the criminal case. It also maximizes the resources available at the national FBI crime laboratories. And establishing such a body of evidence is, after all, one of the primary missions of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of such practice can be seen in the murder of President Kennedy, where we find open ended instructions issued to all FBI field offices to approach contacts and informants and begin checking suspect groups as of the afternoon of the assassination – and find those instructions canceled the following morning, directing all proactive FBI investigation towards Lee Harvey Oswald.

In the case of the King murder, with no suspect in custody, the Bureau spent the better part of two weeks initiating inquiries on the whereabouts and activities of probable suspects and beginning investigation of early leads provided by the public. Much of this attention was directed towards Klan members and militants known to have been involved in or having incited racial violence. We now have documents available which discuss a series of individuals who were investigated during the first 48-72 hours, many of them members and associates of the White Knights of Mississippi.

Once evidence had been processed which linked James Earl Ray to the crime, the Bureau’s proactive work became totally focused on Ray and individuals who were known to have been in contact with him, primarily his brothers. Leads which continued to come into the Bureau continued to be examined on the basis that others might have been involved in a conspiracy but such leads were closed relatively quickly if the suspect had no obvious or immediate association with Ray or if the individual could be shown not to have been in Memphis at the hour of the shooting.

This focus on Ray is illustrated in the handling of a lead which had been forwarded to the Justice Department from Miami immediately after the assassination. Dade County (Miami) Judge Seymour Gelber had written the U.S. Attorney General, suggesting that an investigation should be made of three men who had been involved in racial violence and a plot against Dr. King in 1964. The report contained several names and discussed the individuals’ involvement in the integration confrontations at the University of Mississippi, the possibility that the individuals might have been involved in instigating the 16th Street Church bombing in Birmingham and involved in plans to kill Dr. King in Alabama. One of the individuals had reportedly become so “hot” in Alabama at the time that he had to leave the state.[1]

That lead was forwarded to the relevant Bureau field offices and they did begin work on a background investigation of the individuals, including an attempt to determine where each had been the day of Dr. King’s murder. However, while that investigation was just getting underway, the field offices received an advisory message from Director Hoover. That message ordered that the background ID checks and as well as the overall investigation be held in abeyance. The reason given was that as of April 15th, the identification of a print from Memphis had been made and all general leads not dealing with that suspect were to be put on hold.[2] Placing such leads on hold, the closing of leads which showed no immediate evidence of suspects being in Memphis at the time of the murder or having personal contact with Ray, and the failure to correlate similar leads pointing to the same individuals may well have played a major role in the failure of the Bureau to surface a conspiracy which was indeed associated with Dr. King’s death in Memphis.

Neither the FBI nor the House Select Committee on Assassinations seemed able to conceive of a conspiracy involving people or groups who could effectively compartmentalize their actions. They also seem to have assumed that individuals who might have instigated such an act would have had to personally go to Memphis and be present at the scene of the crime. While the HSCA staff might be forgiven such a mistake, it is clear that individual FBI agents and offices had more than enough painful experience not to underestimate the “inner circle” operations of the Klan in such a fashion. Unfortunately the individuals with the most experience and understanding of the sophistication of such operations - and most success in breaking into such inner circles -were out in the FBI field offices, not directing the overall investigation. And FBI headquarters had no analysis section.

Within 48 hours of Dr. King’s murder, the FBI had received leads pointing towards White Knights leader Sam Bowers, members of his inner circle, and Klan fellow travelers as having been involved in a conspiracy which had brought about the death of Dr. King.[3] Of course those leads were among hundreds which began coming into the Bureau, but given the history of the White Knights and the Bureau’s own previous three year war against them, it would have seemed any names connected to the White Knights would have been highly suspect and worthy of a truly in-depth investigation.[4] The seriousness of such reports should have been magnified given that the FBI’s own informant and case files contained examples of at least two specific White Knight-connected plots to kill Dr. King, one in Alabama and one in Mississippi.v They also contained solid evidence that they had previously used high profile assassination as a provocation strategy in the Medgar Evers murder, that the White Knights were reported to have a standing high dollar bounty on Dr. King, and that they had recently begun to use totally unknown “outsiders” in terror attacks.

The FBI did follow up on such leads, however each was considered separately and there is no indication of any overall effort to collect or evaluate them in a coordinated fashion. In many cases the investigations appear relatively superficial, especially given that the fact that the Bureau should have been well aware of the actual amount of effort and time required to crack previous White Knight terror acts – they had learned that the hard way in their own massive MIBURN (“Mississippi Burning”) investigation, an investigation which had required hundreds of agents, many months of investigation and the combination of significant pressure and offers of both money and immunity – all targeted towards a single tightly knit radical network in Mississippi.

Analysis and follow-on to the Bureau’s King investigative effort is hindered by the fact that specific FBI interviews, provided to the House Select Committee, were classified and have yet to be released after thirty years. The Committee’s own interviews were then classified in turn. In addition, the vast majority of key FBI personal informant files remain confidential (there is also no indication that those were made available to the individual Bureau field offices in their individual King lead investigations) and we have no insight into the details of key field office files from Memphis, Jackson, Mobile, Atlanta or New Orleans. In our own work on the MLK murder, it has become apparent that a great number of documents and files which could allow a much fuller assessment of possible conspiracy in the murder of Dr. King are available. We have provided the following list to individuals pursuing Congressional action on release of King assassination records and share them with interested researchers as an illustration of what can potentially be done to jump start a common effort to unearth the conspiracy that the House Select Committee was able to characterize - but not to solve:

The Missing Pieces

FBI Central Headquarters HQ Files Sections 1-91, as well as the name index for those files, should be culled and reviewed for declassification with additional files released when found. The most abundant source of publicly available files on the MLK murder (MURKIN) are the FBI Central Headquarters files in the National Archives. At present the publicly available files on Dr. King include a few thousand pages of reports from the FBI’s MURKIN investigation, specifically Central HQ Worksheets, Department of Justice Referrals and Central Headquarters Files Sections 1 to 91. A new review (the last seems to have been in 2004) should commence to declassify material from these documents. A major obstacle to any release are the tightened standards of privacy applied to National Archive files in the past five years. Indeed, archive personnel and notations on finding aids indicate that many files or segments of files deemed suitable for full declassification as of 2005 have since been reclassified. Many sections of files are being held in abeyance, in fact, until archive staff can be sure that names and operations have been redacted from the record. Most notably, a name index that could expedite any researcher’s search of available files is being withheld in full for fear of privacy violations. This, although it is obvious that that many persons named on the list are certainly deceased and even though the name index was available to researchers even six years ago. All of these files should be reviewed for declassification using the latest death indices, and made available to the public. If possible, Congress should consider laws and statutes that would place the King material that was once in the public domain back into the public domain.

The materials from the Congressional investigation in the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. should be placed in the public domain. The House Selection Committee on Assassinations investigated King’s murder in the late 1970s, in conjunction with their more well known analysis of President Kennedy’s assassination. Yet the only material in the public record related to this investigation are those in the final report of the HSCA itself. The report makes clear, in its text and its footnotes, that thousands of new leads were unearthed and interviews were conducted as part of the investigation and none of this material is in the public domain. Experts estimate that 165 cubic square feet of material may be available in this regard. In contrast, virtually all of the HSCA’s investigative material on the Kennedy assassination is publicly available to the tune of millions of documents. Publicly available Kennedy materials include documents obtained from foreign intelligence sources and even the National Security Agency, that would obviously be more sensitive than 99% of the King material, which focused almost exclusively on domestic sources. Congress should release this King material as soon as possible by any means possible.

“Bulky files” on the King Assassination should be available to the public. Bulky files refer to the FBI’s investigation of physical evidence and would include photographs, fingerprint cards, lab reports, etc, sometimes even in original form. There are literally tens of thousands of such items publicly available on the Kennedy Assassination. A new search of the King files at the National Archives reveals a large quantity of bulky material, most notably material likely prepared for visual exhibits at the King trial. On the other hand, the kinds of material available in the Kennedy Assassination - fingerprint cards, autopsy materials, lab notes, suspect photographs, etc. - are virtually absent from the King material although it is obvious, from internal FBI communications, that hundreds of pages of such material should exist. The value of such material in the hands of skilled researchers has been demonstrated by such researchers as John Hunt and Gary Murr in the Kennedy case. The FBI laboratory should search its records for this material and provide it to the public.

All remaining records of the FBI Field Office investigations should be in centralized at the National Archives and reviewed for public access. At present, the National Archives has many boxes of records of the local investigations into various aspects of the King assassination, including records from Los Angeles Field Office, the Birmingham Field Office, the New Orleans Field Offices, and others. The record is incomplete, however, and subject to the same restrictions as those applied to the Central Headquarters files described above. To give one of the most obvious examples of “missing” material: none of the Jackson, Mississippi Field Office files are available at the National Archives. An internal FBI review in 1976, apparently done in anticipation of the future House investigation, revealed that the Jackson office had ~50% more material, in terms of boxes, than any other field office (17 boxes worth.) A reporter is now pursuing some of this material via the Jackson FBI, but this appears to be fewer boxes than that which was identified in the internal review. The next highest source of files from the local level - the Mobile, Alabama Field Office files (11 boxes) - is also nowhere to be found at the National Archives. Many other offices whose files were identified by the FBI review are not represented in the archives stash. Our understanding from talking with former FBI Special Agents is that many of these boxes were sent back to FBI Headquarters, and this appears to be confirmed by reviewing the footnotes of the House Selection Committee on Assassinations. All of these files should be located, centralized, reviewed for declassification using the latest death indices, and made available to the public.

Corollary files identified in the FBI Central Headquarters should be assumed as part of the King record, obtained and reviewed for declassification. The presently available FBI MURKIN (King murder investigation) frequently cited other relevant files - such as personnel and bureau files (BUFILES) on key figures and relevant investigations. The inference is that these files have important if indirect information to shed on the King case, yet none of these files are publicly available. When possible, they should be identified and subject to the same proposed review under the same proposed guidelines as the FBI Headquarters Central Files.

Records of prior investigations of attempted murders/assassinations of Dr. King should be publicly available; this should include past threats as well as overt attempts on Dr. King’s life. The record shows that when the FBI provided the MURKIN files to the public, they only included their investigation from April 4th, 1968 onward, when we know that they investigated prior attempts/threats on King’s life. One example would be the records of the FBI Birmingham Field Office participation in a 1958 sting investigation of a contract killing offer on Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders. This offer was reportedly extended by J.B. Stoner; Stoner would later serve as James Earl Ray’s defense attorney and employed his brother as a security assistant. Another example would be the FBI investigation of a $100,000 bounty offer on Dr. King circulated in several prisons in 1967; we only have fragmentary information from these files even though the files themselves indicate that a major investigation was undertaken. What’s more, some of the information we have is not from the MURKIN files but was obtained by researchers from a general King file. In short, the FBI did not parse out threats on Dr. King’s life out of the King Headquarters file and include them in the MURKIN files; they should do so now.

Intelligence Agency, Military files on Dr. King should be publicly available. It is clear that what we do have from the intelligence agencies and military represent a small fraction of what should be available. This has in part led to sensational claims that these agencies themselves were complicit in King’s murder. Yet much of what they have is likely innocent but relevant to the investigation of any crime. Military files would likely include detailed surveillance and security records for both Dr. King’s Memphis trip as well as past trips. Intelligence Agency files would likely include records related to James Earl Ray’s trips to Canada, to Mexico, to England and to Portugal. A massive review of CIA, NSA, DIA, DEA, Pentagon and other files should commence with the goal of identifying relevant King records and making them available to the public.

The Memphis District Attorney’s office investigatory/prosecution files should be obtained and included in the public record. Investigative journalist Gerald Posner makes clear that the Memphis District Attorney’s office has ample and often original material in their files; material that served as the basis for Posner’s book on the King murder that to which he was given privileged access. This material should be publicly available to everyone. In addition, any court and grand jury transcripts should be publicly available, as they are in the case of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s investigation of the Kennedy Assassination.

Foreign intelligence/police files should be obtained when possible and included in the public record. In the late 1970s, Congress had little success prying material from foreign sources, but what is in the public record suggests that this material is abundant and important. There are signs however that their reticence has dampened with time. The Mexicans, for instance, have created their own FOIA law within the past several years, and an investigative journalist in Canada has obtained a section of files from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police that were not previously available. If possible, either a board created to obtain and release records, or a Congressional delegation/representative should consider making an effort to obtain the files of the Mexican DFS, the Canadian Royal Mounted Police, Interpol and Scotland Yard. The files indicate that all four groups conducted their own separate investigations, including one of James Earl Ray before the King murder (in the case of the DFS.) These materials should be pursued as they may prove invaluable to researchers.