Peer Pressure Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on peer pressure.

Peer pressure can be both negative and positive. Because if a person is a peer pressuring you for a good cause then it is motivation. Motivation is essential for the growth of a person. While peer pressure for a bad cause will always lead you to a disastrous situation.

Therefore it necessary for a person to not get influenced by the people around them. They should analyze the outcome of the deed in a strict manner. So that they no may commit anything harmful for themselves. As this world is full of bad people, so you need to be careful before trusting anybody.

Advantages of Peer Pressure

Peer pressure is advantageous in many ways. Most importantly it creates a sense of motivation in the person. Which further forces the person to cross the barrier and achieve something great. Furthermore, it boosts the confidence of a person. Because our brain considers people’s opinions and makes them a priority.

Many salesmen and Entrepreneurs use this technique to influence people to buy their products. Whenever we are in a social meet we always get various recommendations. Therefore when a person gets these recommendations the brain already starts liking it. Or it creates a better image of that thing. This forces the person to buy the product or at least consider it.

This peer pressure technique also works in creating a better character of a person. For instance, when we recommend someone for a particular job, the interviewer already gets a better image of that person. Because he is recommended by a person the interviewer trusts. Therefore there is a great chance of that person to get hired.

Above all the main advantage of peer pressure can be in youth. If a young person gets influenced by an individual or a group of people. He can achieve greater heights in his career.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Disadvantages of Peer Pressure

There are various disadvantages of peer pressure which can harm a person in many ways. If any person is not willing to perform a task then the peer pressure can be frustrating to him.

Furthermore, peer pressure should not be in an excessive manner. Because it lands a negative impact on the person. A person should be of the mindset of listening to himself first. While considering opinions in favor of him.

Peer pressure in youth from a bad company can lead a person to a nasty situation. Furthermore, it can also hamper a student’s career and studies if not averted. Youth these days are much influenced by the glamorous life of celebrities.

And since they follow them so much, these people become their peers. Thus they do such things that they should not. Drugs and smoking are major examples of this. Moreover most shocking is that the minors are even doing these things. This can have adverse effects on their growth and career.

It is necessary to judge the outcome of a deed before getting influenced by peers. Furthermore, peer pressure should always be secondary. Your own thoughts and wants should always have the first priority.

Q1. What is peer pressure?

A1 . Peer pressure is the influence on people by their peers. As a result, people start following their opinions and lifestyle. Furthermore, it is considering a person or his opinion above all and giving him the priority.

Q2. Which sector of the society is the peer pressure adversely affecting?

A2 . Peer pressure has adverse effects on the youth of society. Some false influencers are playing with the minds of the youngsters. As a result, the youth is going in the wrong direction and ruining their career opportunities.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Peer Pressure: 100, 200, and 450 Word Samples in English

- Updated on

- Mar 2, 2024

Have you ever done something just because your friends or peers have done it? Say, watched a movie or TV series, visited places, consumed any substance, or academic achievement. This is a classic example of peer pressure. It means you are influenced by your peers or people around you.

Peer pressure can be both positive and negative, but mostly, it has negative effects. Peer pressure often occurs during adolescence or teenage years when individuals are more susceptible to the opinions and actions of their peers. Sometimes, peer pressure can lead to serious consequences. Therefore, we must deal with peer pressure in a civilized and positive way.

On this page, we will provide you with some samples of how to write an essay on peer pressure. Here are essay on peer pressure in 100, 200 and 450 words.

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay on Peer Pressure in 450 Words

- 2 Essay on Peer Pressure in 200 Words

- 3 Essay on Peer Pressure in 100 Words

Master the art of essay writing with our blog on How to Write an Essay in English .

Essay on Peer Pressure in 450 Words

‘Be true to who you are and proud of who you’re becoming. I have never met a critic who was doing better than me.’ – Jeff Moore

Why do we seek recognition? Why do we want to fit in? Why are we not accepting ourselves in just the way we are? The answer to these questions is almost the same; peer pressure. Peer pressure is the influence of our peers in such a way, that we wish and try to do things in the same way as others did.

Negatives and Positive Peer Pressure

Peer pressure can have positive and negative effects. Positive peer pressure can result in better academic performance, personal growth and development, etc. We can be a source of inspiration to our friends or vice versa, which can result in better academic growth, adopting healthier lifestyles, and engaging in community service. For example, you are part of a group collaborating on a community project that demonstrates the constructive influence of peer interaction. This can encourage a sense of purpose and shared responsibility.

Negative Peer Pressure is the opposite of positive peer pressure. In such cases, we are influenced by the negative bad habits of our peers, which often result in disastrous consequences. Consider the scenario where one of your friends starts smoking simply to conform to the smoking habits of his peers, highlighting the potentially harmful consequences of succumbing to negative influences.

How to Deal With Peer Pressure?

Peer pressure can be dealt with in several ways. The first thing to do is to understand our own values and belief systems. Nobody wants to be controlled by others, and when we know what is important to us, it becomes easier to resist pressure that goes against our beliefs.

A person with self-esteem believes in his or her decisions. It creates a strong sense of self-worth and confidence. When you believe in yourself, you are more likely to make decisions based on your principles rather than succumbing to external influences.

Choosing your friends wisely can be another great way to avoid peer pressure. Positive peer influence can be a powerful tool against negative peer pressure.

Building the habit of saying ‘No’ and confidently facing pressure in uncomfortable situations can be a great way to resist peer pressure. So, it is important to assertively express your thoughts and feelings.

Peer pressure can have different effects on our well-being. It can contribute to personal growth and development, and it can also negatively affect our mental and physical health. We can deal with peer pressure with the necessary skills, open communication, and a supportive environment. We must act and do things in responsible ways.

Also Read: Essay on Green Revolution in 100, 200 and 500 Words

Essay on Peer Pressure in 200 Words

‘A friend recently started smoking just because every guy in his class smokes, and when they hang out, he feels the pressure to conform and be accepted within the group. However, he is not aware of the potential health risks and personal consequences associated with the habit.

This is one of the many negative examples of peer pressure. However, peer pressure can often take positive turns, resulting in better academic performance, and participation in social activities, and physical activities.

Dealing with peer pressure requires a delicate balance and determination. Teenagers must have alternative positive options to resist negative influences. Developing a strong sense of self, understanding personal values, and building confidence are crucial components in navigating the challenges posed by peer pressure.

Learning to say ‘No’ assertively can be a great way to tackle peer pressure. You must understand your boundaries and be confident in your decisions. This way, you can resist pressure that contradicts your values. Also, having a plan in advance for potential pressure situations and seeking support from trusted friends or mentors can contribute to making informed and responsible choices.

‘It is our choice how we want to deal with peer pressure. We can make good and bad decisions, but in the end, we have to accept the fact that we were influenced by our peers and we were trying to fit in.’

Essay on Peer Pressure in 100 Words

‘Peer pressure refers to the influence of your peers. Peer pressure either be of positive or negative types. Positive peer pressure can encourage healthy habits like academic challenges, physical activities, or engaging in positive social activities. Negative peer pressure, on the other hand, can lead us to engage in risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, reckless driving, or skipping school, to fit in with our peers.’

‘There are many ways in which we can deal with peer pressure. Everyone has their personal beliefs and values. Therefore, they must believe in themselves and should not let other things distract them. When we are confident in ourselves, it becomes easier to stand up for what we believe in and make our own choices. Peer pressure can be dealt with by staying positive about yourself.’

Ans: ‘Peer pressure refers to the influence of your peers. Peer pressure either be of positive or negative types. Positive peer pressure can encourage healthy habits like academic challenges,, physical activities, or engaging in positive social activities. Negative peer pressure, on the other hand, can lead us to engage in risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, reckless driving, or skipping school, to fit in with our peers.’

Ans: Peer pressure refers to the influence of our peers or people around us.

Ans: Peer pressure can have both positive and negative effects on school children. It can boost academic performance, encourage participation in social activities, adopt healthier lifestyles, etc. However, peer pressure often results in risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, unsafe activities, or other harmful behaviours.

Related Articles

For more information on such interesting speech topics for your school, visit our speech writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Shiva Tyagi

With an experience of over a year, I've developed a passion for writing blogs on wide range of topics. I am mostly inspired from topics related to social and environmental fields, where you come up with a positive outcome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

The Effects of Peer Pressure on Students, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 761

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

There are no simple answers to the effects of peer pressure on students. It would be unfair to say that most peer pressure results in unwise decisions, as it is often generalized within current culture. Peer pressure transforms a student in a unique manner. The current analysis will examine the most dangerous effects of peer pressure on students, as well as the general negative and positive effects.

Dangerous Effects of Peer Pressure

There are a number of dangerous effects that peer pressure can have on students. These effects are often felt within media and schools, which is where the perceived dangers of peer pressures lie, according to most. However, they certainly cannot be disregarded due to the truth of these concerns.

Alcohol is felt within the consequences of peer pressure in students. With regards to underage drinking, this is a significant problem within students, especially in high school and college. The habits and commonplace of underage drinking is established in high school, which is then perpetuated to one’s college years.

Partying in general is another example of the more dangerous effects of peer pressure. Younger students at parties are around others who are unsupervised, which makes them more susceptible to peer pressure. Thus, items like drinking and other inappropriate behavior are accepted in one’s social circle. Peer pressure is commonly seen at parties, which is where a number of dangerous activities occur.

Sex is also another example of the negative effects of peer pressure. Students are having sex at a younger age, resulting in items like teenage pregnancies. As underage and unprotected sex becomes accepted in social circles, peer pressure often has an effect on students in this way as well.

General Negative Effects

There are a number of generally negative effects that peer pressure can have on a student’s development. Beyond the more dangerous effects, at least in regards to the more clearly defined negative effects, a number of underlying effects of peer pressure can be seen with students. The dynamics that are presented in peer pressure in students can unfortunately be quite negative.

Peer pressure can often drown out the opinion of one. When students are engaged in certain social circles, it is not uncommon to see the unfair treatment of individuals. Certain individuals, whether they are not liked, ignored, or just not seen, are often unable to relate to others.

Peer pressure also removes the choices that one should be able to make. A number of events and activities that students are involved in are done on a social level. Such activities remove the healthy choices that enable students to seek adventure and healthy activities, instead of what is expected or on schedule.

The underlying negative dynamic of peer pressure is the ultimate undermining of individuality. Peer pressure has the unfortunate effect of removing one’s own will and desires, in order to become accepted or liked within a social circle. As seen in these negative examples and in the more dangerous illustrations, the individual is often casted our in peer pressure. As a result, one is left to follow others in that of peer pressure.

General Positive Effects

Peer pressure can of course have positive effects on students. While this is often not portrayed, it rings true for many students. It can often push and help one to realize or perform something, to help someone thrive with the help of others.

Peer pressure can help individuals in more difficult periods. Friends are there to help someone in tough times, and peer pressure can help someone who needs wise council. Many students, who are involved with the right people, are able to enjoy the positive relationships when they need them the most.

Some activities driven by peer pressure can help students get involved. Activities and functions can be great for the social development of a student. Peer pressure, even when applied outside of one’s comfort zone, can ultimately be beneficial.

Peer pressure can also help individuals make the right choices. When students face difficult choices in their life, they often rely on their friends. In this manner peer pressure can help persuade one to the right decision, allowing their friend to see the positive way to react to an important choice.

It is unfortunate that peer pressure is often regarded in one dimension. While there are certainly negative effects of peer pressure, such as those that undermine one’s individuality and encourage dangerous practices, peer pressure can help an individual develop through the difficult times as a student and a person. Centered on surrounding oneself with positive influences, peer pressure can rise above the negative effects to institute healthy social and personal steps of one’s development.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Restructuring For Growth, Research Paper Example

Just Web Internet Policy Manual, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology Peer Pressure

Navigating Peer Pressure: Supporting Students' Academic Success

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Caste System

- Conflict Resolution

- Social Conflicts

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Social Impact Oct 2, 2018

How peer pressure can lead teens to underachieve—even in schools where it’s “cool to be smart”, new research offers lessons for administrators hoping to improve student performance..

Leonardo Bursztyn

Georgy Egorov

Robert Jensen

Peer pressure can play a huge role in the choices that students make in school, extending beyond the clothes they wear or music they listen to.

Think, for example, of a student deciding whether to participate in educational activities, such as raising their hand in class or signing up for enrichment programs. While these efforts may be good for a college application, they also could affect how classmates perceive the student. Pressure to not seem like a nerd could make kids refrain from taking part. So why, exactly, do some kids shy away from showing effort in front of their peers? In a recent study, Georgy Egorov , a professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at Kellogg, and his collaborators considered two possibilities. In some schools, perhaps kids face a social stigma for publicly making an effort to excel. The researchers called this culture “smart to be cool.” But in other schools, perhaps high achievers are popular, and students feel pressure to do well; in other words, it’s “cool to be smart.” Perhaps counterintuitively, this type of school culture could also cause kids to avoid participating if they do not view themselves as smart and don’t want to reveal their poor grasp of the material. “If social pressure rewards high performance, then they might want to shy away from engaging if they feel unprepared,” Egorov says. The researchers used a mathematical model, as well as a field experiment at three high schools, to confirm their prediction that the reason why students shy away from showing effort can differ depending on which of these two school cultures is predominant. Given that, it is important for administrators to know which culture is stronger at a particular school when designing policies, Egorov says. For example, in a cool-to-be-smart school, students might be more likely to attend an after-school program if it is called “enrichment” rather than “extra help.” But in a smart-to-be-cool school, kids might find it more socially acceptable to seek “extra help” to avoid failing a class than “enrichment,” which suggests trying to excel. Overall, the research suggests that the reasons why some students fail to take advantage of educational opportunities can differ greatly depending on the school’s overall culture. “Many schools have kids who are underperforming,” Egorov says, “but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s all the same mechanism at work.”

An Alternate Explanation

The starting point for this research was an influential 2006 paper by Harvard economist Roland Fryer. Fryer was interested in underperformance among minority students, and looked in particular at the role of peer pressure. He found that in some types of schools, African-American and Hispanic students become less popular as their grades increase, while white students become more popular as their grades go up. In situations where studying hard is stigmatized by one’s peers, Fryer concluded, underperforming students may be deliberately trying not to appear engaged in school. But what about schools that have the opposite culture, where kids are admired for being high achievers? Do students there also deliberately downplay a desire to excel? And, if they do, are they doing it for the same reasons as students in smart-to-be-cool schools? To find out, Egorov and his collaborators, Leonardo Bursztyn at the University of Chicago and Robert Jensen at the University of Pennsylvania, first created a mathematical model to represent students in a school.

The reasons why some students fail to take advantage of educational opportunities can differ greatly depending on the school’s overall culture.

The model allowed for two types of school culture, one that rewarded high achievement and one that rewarded a lack of effort. The model also allowed students to choose to sign up for an educational activity, with their choice either being made public or kept private, as well as their performance on it being made public or kept private. Importantly, the researchers also introduced a lottery to the model. Among the students who signed up, some of them would “win” the chance to participate in the activity. The team showed that when the probability of “winning” the activity changed, interesting differences emerged. In the smart-to-be-cool school, one would expect that if signing up and participating in an activity were done publicly, fewer kids would do it because they wouldn’t want to seem like they are trying hard. But what happens when the chances of winning the activity increase? In making their decision, students are weighing two types of benefits: the social perks of their classmates’ approval if they do not appear to be trying to excel vs. the economic perks of getting a better education. When the chances of winning are low, the student is socially stigmatized for signing up and probably will not even receive the educational reward. But if the chances of winning are high, the net benefits increase. While the student still faces disapproval from peers, at least she is more likely to boost her economic prospects. And, under these circumstances, the model predicts that more students would likely sign up. “You are more likely to sign up if at least you get something for that,” Egorov says. In this “public” scenario, increasing the chances of winning would have the opposite effect at a cool-to-be-smart school. Students there benefit socially from signing up: showing they want to participate makes them fit in with the high achievers. So when the probability of winning is low, students can sign up to signal that they are smart without running a big risk that they will actually have to do the activity in public, which could reveal that they are low performers. If the chances of winning—and therefore having their performance made public—are high, they are less likely to sign up. Egorov compares the situation to a teacher asking a question in class. If a low-performing student raises his hand when no one else is doing so, his chances of “winning” participation—that is, being called on by the teacher—are high. So the student is unlikely to take that risk. But if ten other kids have already raised their hands, a low-performing student might do the same to fit in with smart peers, since the teacher probably won’t call on him anyway. “Raising your hand is safe,” Egorov says. “You try to pool with the high performers at low risk.”

Striking Differences

To test these predictions, the team visited 11th-grade classrooms at three high schools in Los Angeles: one that previous research hinted would have a smart-to-be-cool culture, and two others that the team suspected might have a cool-to-be-smart culture. (A subsequent survey of students indeed confirmed that the schools had the predicted cultures.) To run their experiment, the researchers gave 511 students a form that offered the chance to enter a lottery to win a real SAT prep package, which would include a diagnostic test to identify strengths and weaknesses. Some forms said that the sign-up decision and test results would be completely anonymous; others hinted that the results might be visible to classmates. The team also varied the probability of winning the lottery for the package. Some forms said the student had a 75 percent chance, while others listed a 25 percent chance. As expected, fear of peers’ judgment seemed to drive decisions. In both types of schools, when the students’ choice and test results were private, about 80 percent signed up. But in the public scenario, that figure dropped to 53 percent. If the experiment had stopped there, the researchers might have assumed that effort and achievement were stigmatized in all the schools. But when researchers analyzed the results based on whether the probability of winning the lottery was high or low, a very different picture emerged. As their model predicted, changing the chance of winning in the public scenario revealed substantial differences between the two types of schools. In the smart-to-be-cool school, sign-up rates rose from 44 percent to 62 percent when the probability of winning the lottery increased, suggesting that students were willing to risk social stigma only when they thought they stood a good chance of accessing the SAT prep package. But in cool-to-be-smart schools, sign-up rates showed the opposite pattern, dropping from 66 percent to 40 percent.

Tailored Policy Solutions

Egorov is quick to point out that the experiment was done at only three schools, so the findings should not be generalized across schools based solely on their student demographics or other observable factors, such as school location. But, he says, the results suggest that administrators should understand their school’s culture when designing policies. For example, making class participation mandatory in a smart-to-be cool school could reduce the stigma of raising one’s hand. But in a cool-to-be-smart school, the same policy could provoke struggling students to disrupt class so they can avoid participating.

James Farley/Booz, Allen & Hamilton Research Professor; Professor of Managerial Economics & Decision Sciences

About the Writer Roberta Kwok is a freelance science writer based near Seattle.

About the Research Bursztyn, Leonardo, Georgy Egorov, and Robert Jensen. Forthcoming. “Cool to Be Smart or Smart to Be Cool? Understanding Peer Pressure in Education.” Review of Economic Studies .

We’ll send you one email a week with content you actually want to read, curated by the Insight team.

84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best peer pressure topic ideas & essay examples, 📌 simple & easy peer pressure essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on peer pressure, ❓ questions about peer pressure.

- Peer Pressure: Positive and Negative Effects When I was in high school, I happened to be assigned to a discussion group that was comprised of people who valued the process of studying a lot. The influence of the group played a […]

- Peer Pressure in Society The peer pressure of various characteristics due to the community’s contradicting desire can lead to moral decay or psychological illness in a person.

- Friends’ Influence and Peer Pressure in Adolescents The list of physical and emotional transformations happening to the young people during adolescence is universal; the processes are the same for all teenagers.

- Peer Pressure and Smoking Influence on Teenagers The study results indicate that teenagers understand the health and social implications of smoking, but peer pressure contributes to the activity’s uptake.

- Peer Pressure in High School However, the best and easy way in this tough world, or in the peer group, is to prove oneself as a rebellious teen.

- Peer Pressure Causes and Resistance If Jack does not stay in a company where everybody smokes, he will not feel the pressure to do it. If it does not help, and Jack continues to feel pressure, it is possible for […]

- How Does Peer Pressure Contribute to Adolescent Depression? Therefore, it is possible to note that peer pressure is one of the most significant factors contributing to the development of adolescent depression.

- Peer Pressure and Life Span Reduction: An Unusual Perspective on the old Problem Therefore, among the dependable variables, the temper of the victim and his/her aptitude to change under the pressure of the circumstances should be mentioned.

- Peer Pressure as One of the Main Teenagers Problem The introduction of a healthy social and psychological environment in schools is a program that will be implemented to help curb negative effects of peer pressure.

- Peer Pressure: Facing Challenges The group should conduct lectures on the basis of education and upbringing for families to be aware of the challenges and constraints.

- The Strength of Peer Pressure on the Youth

- The Influence of Peer Pressure and Its Social and Financial Problems

- The Issues of Depression, Peer Pressure and Stress Among Youth

- Peer Pressure Can Be Attributed to Increased Number of Teenage Smoking

- The Potential Benefits of Peer Pressure

- The Positive And Negative Effects Of Peer Pressure

- An Overview of the Dangers of Peer Pressure in the United States

- The Effects Of Peer Pressure On Adolescents Delinquent Behavior

- Early Adolescents’ Perceptions of Peer Pressure

- The Importance of Good Communication with Family to Withstand Peer Pressure and Bad Influences from Friends

- An Evaluation of the Influence of Peer Pressure to the Rising Use of Drugs

- The Negative Effects of Peer Pressure in the Teenaged Years

- Theories of Personality: Giving in to Peer Pressure

- Effective Ways a Student Resist Peer Pressure

- Peer Pressure Awareness: Live Above the Influence

- The Positive and Negative Influences of Peer Pressure on Behavior

- Body Image, Peer Pressure, and Identity in Mean Girls

- Peer Pressure and its Impact on Teenagers Choices

- The Influence of Peer Pressure in Succumbing to Alcohol and Cigarettes

- The Impact of Peer Pressure in Adolescents and How to Cope with It

- The Variables of Positive Peer Pressure for Creating a Safer School Environment

- The Pressue is On: The Impacts of Peer Pressure in Julius

- The Influence of Peer Pressure on Children and Adults

- Dealing with Peer Pressure as a Teenager

- The Peer Pressure on the Human Beings

- Understanding Diabetes Burnout and the Contribution of Peer Pressure to Diabetes in Children

- The Reasons or Teenage Attractions to Gangs and Peer Pressure Resulting in Crime

- Transparency, Inequity Aversion, and the Dynamics of Peer Pressure in Teams: Theory and Evidence

- The Effects of Peer Pressure on the Academic Performance

- The Role Of Peer Pressure On Teens And Decision Making

- The Theme Of Peer Pressure In Night By Elie Wiesel

- What Is Peer Pressure Health And Social Care

- Cool to be Smart or Smart to be Cool? Understanding Peer Pressure in Education

- Effects of Peer Pressure on Decision Making

- The Types of Peer Pressure Teenagers Face

- What Peer Pressure Is How It Affects Us

- The Negative Impacts and Influence of Peer Pressure on Teenagers

- The Poor Choices Teenagers Make Due to Peer Pressure

- Caue and Effects of Peer Pressure

- Does Peer Pressure Have an Effect on First Time Drug Use

- Peer Pressure In Adolescents: Drugs, Alcohol, And Sex

- The Pros and Cons of Peer Pressure

- The Role of Peer Pressure in the Development of Eating Disorders

- What Are the Main Causes of Peer Pressure?

- What Is the Problem of Peer Pressure?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Society?

- What Are the Statistics on Peer Pressure?

- How Can Peer Pressure Be Defined as Influence From Members Of?

- Does Peer Pressure Help Students Grow?

- Does Peer Pressure Create Social Pressure?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Social Behavior?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect the Brain?

- How Does Peer Pressure Contribute to the Spread of HIV Among the Youth?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Youth?

- How Can Peer Pressure Positively and Negatively Affect a Teen?

- What Are the Four Types of Peer Pressure?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Decision Making?

- Why Are Parents Loosening up on Restructuring Their Children and Giving Way to Peer Pressure?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Someone’s Choices and Their Lifestyle?

- What Can Schools Do to Stop Peer Pressure?

- Does Peer Pressure Have an Influence on College Students Being in a Monogamous Relationship?

- How Much Does Peer Pressure Affect Students?

- Does Peer Pressure Have an Effect on First-Time Drug Use?

- How Do Peers Pressure Influence Learning?

- What Is Peer Pressure for Students?

- How Can Peer Pressure Lead To Crime?

- How Does Peer Pressure Affect Educational Investments?

- How Has Peer Pressure Been Popularly Blamed for Adolescent Behaviors?

- How Can Peer Pressure Impact Negatively on Teenagers?

- How Can We Stop Peer Pressure?

- Who Is Most Affected by Peer Pressure?

- Why Is Peer Pressure a Problem?

- Alcohol Essay Titles

- Cyber Bullying Essay Ideas

- Drug Abuse Research Topics

- Marijuana Ideas

- Online Community Essay Topics

- Smoking Research Topics

- Teenagers Research Topics

- Bullying Research Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/peer-pressure-essay-topics/

"84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/peer-pressure-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/peer-pressure-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/peer-pressure-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "84 Peer Pressure Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/peer-pressure-essay-topics/.

Essay on Peer Pressure

Updated December 21, 2023

Do you know the latest trend?

In the quest to find our place within friend circles, we often engage in activities we might not truly desire. The constant need to stay in tune with our identity while also aligning with the vibes of our peers has become a crucial aspect of teenage life. If you’ve ever felt the pressure to conform, rest assured, you’re not alone. Today, we address this widespread challenge experienced by every teenager and offer practical suggestions on navigating and coping with it.

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

Types of Peer Pressure

Let’s delve into the various types of peer pressure:

1. Direct Peer Pressure

Direct peer pressure involves explicit attempts by individuals to influence others to conform to specific behaviors, choices, or actions. This can manifest through direct persuasion, encouragement, or even coercion. Examples include friends urging someone to try drugs, engage in risky activities, or adopt a particular lifestyle. The impact of direct peer pressure is immediate and tangible, as individuals may feel compelled to conform to avoid social rejection or gain approval.

2. Indirect Peer Pressure

Unlike its direct counterpart, indirect peer pressure operates more subtly. It involves the influence of societal norms, trends, or expectations that indirectly shape individuals’ behaviors. In this form, individuals may feel compelled to conform without explicit suggestions from peers. Adapting one’s appearance, interests, or behavior to align with what is considered popular or socially acceptable reflects the subtlety of indirect peer pressure. It often operates on a broader societal level, shaping cultural expectations and individual choices.

3. Positive Peer Pressure

Positive peer pressure involves encouraging or influencing peers towards behaviors that have constructive outcomes. Friends may motivate one another to study harder, participate in sports, or perform community service. This peer pressure fosters personal growth and development, creating a positive and supportive social environment. It emphasizes shared goals that benefit individuals and the community, promoting a sense of collective achievement.

4. Negative Peer Pressure

Negative peer pressure, on the other hand, encourages individuals to participate in potentially dangerous actions. Friends might pressure someone to skip classes, experiment with drugs, or engage in delinquent activities. Negative peer pressure often stems from the desire for social acceptance, fear of exclusion, or misguided attempts to fit in. The consequences of succumbing to negative peer pressure can range from immediate risks to long-term adverse effects on an individual’s well-being.

5. Individual Peer Pressure

Individual peer pressure is an internalized form where individuals pressure themselves to conform to perceived expectations, even without direct external influence. This may stem from a desire to fit in, avoid standing out, or align with personal ideals. The pressure comes from within, as individuals may feel compelled to adopt certain habits or make specific choices based on their perception of social norms or expectations.

6. Relational Peer Pressure

Relational peer pressure involves the influence exerted by the dynamics within specific relationships or cliques. Individuals within a close-knit group may feel pressure to conform to maintain social harmony. This form can be particularly intense, as the desire to belong and avoid conflict within the group may lead individuals to compromise their values or adopt behaviors that align with the group’s expectations.

7. Cyber Peer Pressure

With the advent of technology, cyber peer pressure emerges through online platforms, social media, and digital interactions. Individuals may feel compelled to conform to digital trends, participate in online challenges, or adopt behaviors influenced by their peers. Cyber peer pressure adds a new dimension to social influence as the online world shapes perceptions and expectations, impacting individuals’ choices and behaviors in both virtual and real-life settings.

Factors Contributing to Peer Pressure

Many factors shape the influence of peer pressure, each playing a role in the complex dynamics of social interactions. Here are key factors contributing to peer pressure:

- Developmental Stage: Peer pressure varies across different stages of development, with adolescents being particularly susceptible. During this phase, individuals often strive for identity and acceptance, making them more prone to conforming to peer expectations.

- Social Environment: Family, school, and community settings significantly impact the nature and intensity of peer pressure. Cultural norms and societal expectations can shape the values and behaviors that peers influence.

- Media and Technology: The pervasive influence of media, including social media platforms, can amplify peer pressure. Digital trends and online behaviors can quickly become influential, setting new standards for acceptance and popularity.

- Parental Influence: Parental attitudes and expectations affect how individuals respond to peer pressure. Parenting styles that encourage open communication and provide guidance can equip individuals with the tools to resist negative influences.

- School Environment: The social dynamics within schools, including the prevalence of cliques and social hierarchies, can intensify peer pressure. Academic and extracurricular pursuits may also contribute to individual pressures.

- Individual Differences: Personal traits, such as self-esteem, confidence, and resilience, play a crucial role in how individuals respond to peer pressure. Those with a strong sense of self are often better equipped to resist negative influences.

- Desire for Acceptance: The innate human need for social acceptance can drive individuals to conform to peer expectations. Fear of rejection or exclusion can be a powerful motivator, leading to choices that align with group norms.

- Cultural Influences: Cultural values and norms shape the expectations placed on individuals within a particular society. Conforming to these expectations may be seen as fitting in and gaining social approval.

- Peer Group Dynamics: The characteristics and behaviors of a specific peer group strongly influence the type of pressure exerted. Groups with shared interests and values may exert positive pressure, while others may promote negative behaviors.

- Lack of Guidance: Inadequate advice from trusted adults or mentors might leave individuals vulnerable to peer pressure. Having supportive role models can help individuals navigate peer pressure more effectively.

Effects of Peer Pressure

- Psychological Impact: Peer pressure can exert a profound psychological toll on individuals, manifesting in heightened stress, anxiety, and emotional turmoil. The persistent drive to conform to the expectations of a peer group can lead to internal conflicts as individuals struggle with the friction between their real selves and the need for social acceptability. Rejection or isolation can weaken identity, affect mental health, and lead to inadequacy.

- Behavioral Changes: The effects of peer pressure often extend to observable changes in behavior. Individuals may find themselves engaging in activities they would otherwise avoid, succumbing to the influence of their peers. This might range from following specific fashion trends to engaging in dangerous activities or substance misuse. Behavioral changes, driven by the desire to fit in or gain approval, may have immediate consequences and, if unchecked, can lead to long-term habits that deviate from one’s true values.

- Social Conformity: One prevalent effect of peer pressure is the inclination towards social conformity, where individuals alter their actions and beliefs to align with those of their peers. While providing a sense of belonging, this conformity can erode individual autonomy and critical thinking. The fear of standing out or being perceived as different may lead individuals to compromise their values, hindering personal growth and the development of a strong, independent identity.

- Risk-Taking Behavior: Negative peer pressure is often associated with increased risk-taking behavior. Whether it involves experimenting with substances, engaging in dangerous activities, or disregarding personal safety, individuals under the influence of peer pressure may take risks they would otherwise avoid. The allure of acceptance within a group can override rational decision-making, exposing individuals to potentially harmful situations and long-term consequences.

- Impact on Academic Performance: Peer pressure can extend into the academic sphere, affecting an individual’s focus, priorities, and study habits. Pursuing social acceptance may lead some students to prioritize socializing over academic responsibilities, potentially resulting in lower grades and compromised educational outcomes. This shift in priorities can affect future opportunities and personal development.

- Strained Relationships: The influence of peer pressure can strain relationships with family and non-peer connections. Conflicting expectations between peer groups and other significant relationships may create tension and create isolation. The pressure to prioritize peer relationships over familial or personal values can strain bonds and create challenges in maintaining a healthy support system outside the immediate peer group.

Coping Strategies and Solutions

1. building resilience.

Building resilience involves developing the ability to withstand and bounce back from challenges, including peer pressure. This can be achieved by fostering a strong sense of self, cultivating a positive mindset, and embracing failures as opportunities for growth. Resilient individuals are better equipped to navigate social pressures while staying true to their values and beliefs.

Example: Encouraging individuals to reflect on past challenges, identify strengths gained from overcoming them, and framing setbacks as learning experiences enhance resilience.

2. Assertiveness and Communication Skills

Developing assertiveness and effective communication skills empowers individuals to express their thoughts, opinions, and boundaries confidently. Being able to articulate one’s values and decisions helps in resisting negative peer pressure without succumbing to the fear of social rejection.

Example: Role-playing scenarios where individuals practice assertive communication can strengthen their ability to convey their choices respectfully and confidently.

3. Support Networks

Establishing and maintaining supportive relationships can be a crucial coping strategy. Having friends, family, or mentors who understand and respect individual choices provides a strong foundation against negative peer influences. Support networks offer encouragement, guidance, and a sense of belonging.

Example: Encouraging open communication within families, fostering mentorship programs, and creating supportive peer groups help individuals build and sustain positive connections.

4. Setting Boundaries

Clearly defining personal boundaries involves recognizing one’s limits and communicating them effectively. Setting boundaries is essential to maintaining autonomy and safeguarding individual values in the face of peer pressure.

Example: Individuals can practice assertively communicating their boundaries, such as saying “no” to activities that go against their values or comfort levels, reinforcing their commitment to personal integrity.

5. Cultivating Self-Efficacy

Cultivating self-efficacy involves developing a belief in one’s ability to navigate challenges and achieve goals. Individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to resist negative peer pressure, as they have confidence in their capacity to make independent and positive choices.

Example: Encouraging individuals to set and achieve small goals builds self-efficacy, contributing to a sense of agency and control over their lives.

6. Critical Thinking Skills

Enhancing critical thinking skills enables individuals to assess situations objectively, weigh potential consequences, and make informed decisions. This cognitive ability is crucial in resisting peer pressure by allowing individuals to evaluate the impact of their choices on their well-being and future.

Example: Engaging in discussions that encourage critical thinking, such as analyzing the motivations behind peer pressure, helps individuals develop a thoughtful and analytical approach to decision-making.

7. Positive Role Models

Positive role models provide individuals with examples of values and behaviors that align with their aspirations. Observing and learning from role models who exemplify resilience, integrity, and independence can inspire individuals to resist negative peer pressure.

Example: Encouraging mentorship programs, highlighting inspirational figures, and fostering positive role models within communities contribute to a supportive environment.

Parental and Educational Roles

1. parental guidance.

- Open Communication: Effective communication between parents and their adolescents is a cornerstone in mitigating the impact of peer pressure. Encouraging an open dialogue creates a space where adolescents feel comfortable expressing their thoughts, concerns, and experiences. Parents might get significant insights into their children’s difficulties by actively listening and providing nonjudgmental assistance.

- Setting Realistic Expectations: Parents greatly influence their children’s expectations and values. Parents can assist teens in developing a strong internal compass by setting realistic expectations and emphasizing the implications of confident choices. This entails instilling a feeling of duty and accountability in them and equipping them to make informed decisions in the face of peer pressure.

2. School-based Programs

- Peer Mentoring: Peer mentoring programs within educational institutions can provide adolescents with positive role models. Older students serving as mentors can offer guidance, share personal experiences, and create a supportive environment for younger peers. This fosters a sense of community and helps counterbalance negative peer pressure with constructive influences.

- Character Education Initiatives: Integrating character education into the curriculum can equip students with essential life skills. This includes promoting values such as integrity, resilience, and empathy. Through targeted programs, schools can create an atmosphere that encourages personal development and cultivates a strong sense of self, helping students withstand negative peer pressure.

Case Studies and Examples

1. resisting negative peer pressure in college.

Emma, a college freshman, faced pressure from her new group of friends to participate in heavy drinking at social gatherings. Despite feeling uncomfortable with excessive alcohol consumption, Emma didn’t want to be perceived as “uncool” or risk social exclusion.

Emma decided to communicate her boundaries with her friends openly. She expressed her preference not to engage in heavy drinking due to personal reasons and health concerns. Surprisingly, her friends respected her decision; some shared similar problems but hesitated to voice them. This case illustrates the power of assertiveness and open communication in resisting negative peer pressure.

2. Positive Peer Pressure Leading to Academic Success

Mark was part of a friend group prioritizing academic achievement as a high school student. Although initially hesitant, Mark was positively influenced by his friends’ dedication to their studies.

Over time, Mark’s grades improved, and he became more focused on his academic goals. The positive peer pressure from his friends helped him develop better study habits and encouraged him to set higher educational aspirations for himself. This example showcases how peer influence can contribute to constructive outcomes when aligned with personal growth.

3. Navigating Cultural Expectations

Sara, a teen from a conservative cultural background, was under pressure to conform to traditional gender norms and job expectations. Her family expected her to pursue a medical career, but she aspired to become a graphic designer.

Sara engaged in open and respectful communication with her family, explaining her passion for graphic design. With time, she educated her family on the potential success and fulfillment she could find in this field. Eventually, her family, realizing her dedication, supported her decision. This case demonstrates the importance of setting and communicating personal goals even when facing cultural or familial expectations.

4. Peer Support in Overcoming Substance Abuse

Jake struggled with substance abuse during his teenage years, influenced by a group of friends who engaged in regular drug use. Recognizing the negative impact on his life, Jake decided to seek help.

With the support of a counselor and the encouragement of a new group of friends who promoted a drug-free lifestyle, Jake successfully overcame his addiction. This example underscores the significance of positive peer support in overcoming detrimental behaviors and making positive life choices.

5. Balancing Social and Academic Commitments

Sophia, a college student, faced the challenge of balancing social activities with academic responsibilities. Her friends often encouraged her to prioritize social events over study sessions.

Sophia implemented a time-management plan that allowed her to participate in social activities while dedicating focused time to her studies. She found a balance that met her social and academic needs by communicating her academic goals to her friends and involving them in group study sessions. This case highlights the importance of effective time management and communication in navigating peer pressure.

Peer pressure is a pervasive force that significantly shapes individuals’ lives. Whether facing challenges or enjoying positive influences, navigating peer pressure requires a combination of resilience, assertiveness, and a strong sense of self. Individuals can navigate social dynamics by fostering open communication, building supportive networks, and embracing positive role models while staying true to their values. Ultimately, understanding and addressing peer pressure contribute to personal growth, empowerment, and the development of authentic, fulfilling lives.

*Please provide your correct email id. Login details for this Free course will be emailed to you

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Web Development & many more.

Forgot Password?

This website or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Explore 1000+ varieties of Mock tests View more

Submit Next Question

🚀 Limited Time Offer! - 🎁 ENROLL NOW

Cover Story

Students under pressure

College and university counseling centers are examining how best to serve the growing number of students seeking their services.

By Amy Novotney

September 2014, Vol 45, No. 8

Print version: page 36

11 min read

Nicole Stearman remembers the morning well. Around 10:30 a.m., just as her research methods class at Eastern Washington University was finishing up, she felt an abrupt sense of terror and shortness of breath. It was the start of a panic attack — not the first she'd experienced — and she knew she needed immediate help. Stearman headed straight to the university's counseling and psychological services center.

When she arrived, she learned there were no counselors available, so she left and found a corner of the building to ride out the rest of the attack. "I can't really time my panic attacks to hit only on weekdays during the center's 11 a.m.- 4 p.m. counselor walk-in hours," says Stearman, who'd been diagnosed with depression and social phobia/social anxiety disorder in high school. "While the counseling center is a great resource, it could be a lot better."

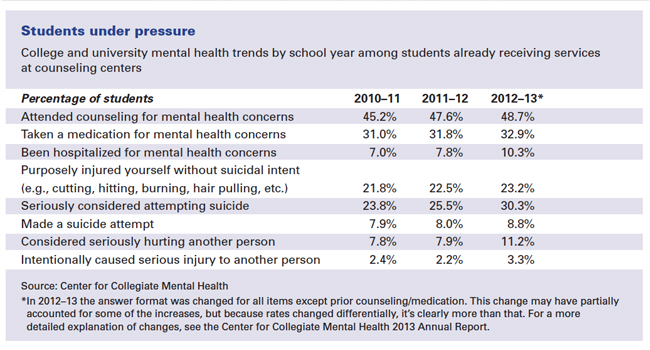

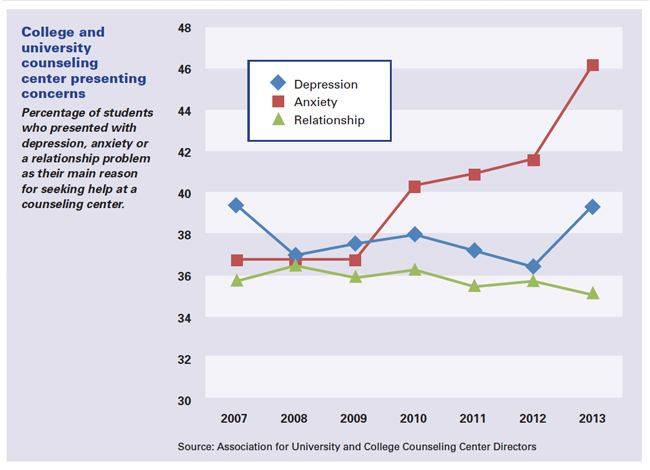

Stearman is one of an increasing number of students who struggle with getting treatment for their mental health issues in college. About one-third of U.S. college students had difficulty functioning in the last 12 months due to depression, and almost half said they felt overwhelming anxiety in the last year, according to the 2013 National College Health Assessment, which examined data from 125,000 students from more than 150 colleges and universities.

Other statistics are even more alarming: More than 30 percent of students who seek services for mental health issues report that they have seriously considered attempting suicide at some point in their lives, up from about 24 percent in 2010, says Pennsylvania State University psychologist Ben Locke, PhD, who directs the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH), an organization that gathers college mental health data from more than 263 college and university counseling or mental health centers.

"Those who have worked in counseling centers for the last decade have been consistently ringing a bell saying something is wrong, things are getting worse with regard to college student mental health," Locke says. "With this year's report, we're now able to say, ‘Yes, you're right.' These are really clear and concerning trends."

Psychologists are stepping in to help address these trends in several ways. Researchers are examining the effect of mental health on how prepared students are for learning and exploring innovative ways to expand services and work with faculty to embed mental wellness messages in the classroom, says Louise Douce, PhD, special assistant to the vice president of student life at Ohio State University.

"For students to be able to learn at their peak capacity, they need to be physically, emotionally, intellectually and spiritually well," says Douce. "Students who struggle are more likely to drop out of school, but by providing services for their anxiety, depression and relationship issues, we can help them manage these issues, focus on their academics and learn new ways to be in the world."

More students, more need

One of the biggest reasons why college and university counseling services are seeing an increase in the number of people requesting help and in the severity of their cases is simply that more people are now attending college. Enrollment in degree-granting institutions increased by 11 percent from 1991 to 2001 and another 32 percent from 2001 to 2011, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

"One of the things that seems to be going on for colleges and universities is that as access to colleges and universities continues to grow, the population of colleges and universities is moving towards the general population, especially if you combine community colleges as part of that equation. So the level of need for access and the severity of concerns is growing — just like it has been in the general population," Locke says.

In addition, students who may not have attended college previously due to mental health issues, such as depression or schizophrenia, or behavioral or developmental concerns, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism, are now able to attend thanks to better treatment approaches and new medications. Access to wraparound services and individualized education plans in primary and secondary education have also helped more students graduate high school and qualify to attend college.

But when these young people go to college, such specialized services and accommodations rarely exist. The result is more students seeking help at counseling centers. Over the last three school years, the CCMH reports a nearly 8 percent increase in the number of students seeking mental health services. And college counseling centers report that 32 percent of centers report having a waiting list at some point during the school year, according to the 2013 Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors (AUCCCD) survey .

Unfortunately, even as students want more services, many center budgets remain unchanged or have increased only slightly from years past, the same survey finds. AUCCCD survey data suggest that larger institutions have struggled to attain pre-2008 recession budget levels, reflected in fewer counseling clinicians proportionate to the student body, compared with smaller institutions. The result can be seen in lower utilization rates and large waiting lists. In fact, the AUCCCD survey finds that from 2010 to 2012, the average maximum number of students on a waiting list for institutions with more than 25,000 students nearly doubled, from 35 students to 62 students.

Healthy minds and the bottom line

One way that counseling centers are trying to get more support for mental health services is by focusing on a factor administrators understand: a return on investment.

Research led by University of Michigan economist Daniel Eisenberg, PhD, for example, suggests that investing in mental health services for college students can help keep them from dropping out ( B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy , 2009). That's good news for schools since they want to retain tuition revenue, but more important, it helps secure significantly higher lifetime earnings for the students, Eisenberg says.

"Every college and university cares a lot about its retention rate," he says. "It's one of the primary indicators of operating a successful institution — that people want to stay and that people are succeeding there."

Eisenberg has replicated these findings with samples from other colleges and universities, and in 2013, posted a formula to help counseling centers develop their own return on investment spreadsheet to present to university administrators when advocating for additional funding. Users can plug in their school's population size, departure/retention rate, and prevalence of depression to calculate the economic case for student mental health services.

"This economic case doesn't even count the most direct benefits of mental health services and programs — the boost in student well-being and the relief of suffering," Eisenberg says. Students who participate in counseling report improvements in their satisfaction with their quality of life — often a better predictor of student retention than grade point average.

Innovative treatment models

The insufficient funding for college mental health services also means inadequate access to care and treatment. Colleges and universities are addressing this challenge by developing quick screening tools and brief consultations to rapidly determine the needs of each new student who visits the counseling center. The University of Texas at Austin's Counseling and Mental Health Center, for example, created a Brief Assessment and Referral Team (BART), which replaces a lengthy initial consultation with a brief assessment with a trained counselor, who then refers the student to the appropriate level of care.

"For some students, a single session with a mental health professional is all they need, perhaps to help them problem-solve a situation or talk about a personal concern," says Chris Brownson, PhD, associate vice president for student affairs and director of UT-Austin's Counseling Center. "Other students are in need of more intermediate or even extended care. This is a way of getting students in front of a counselor more quickly and then ultimately getting them connected to the type of treatment that they need in a much faster way."

In another effort to connect students with mental health services faster, the University of Florida's Counseling and Wellness Center launched its Therapist Assisted Online (TAO) program to deliver therapy to students with anxiety disorders — all over a computer or smartphone screen. The seven-week program consists of several modules that teach students to observe their anxiety, live one day at a time and face fears. Students also have weekly 10- to 12-minute video conferences with counselors, as well as homework that they do via an app. They even get text message reminders to prompt them to complete their assignments, says Sherry Benton, PhD, the former director of the UF counseling center who led TAO's development.

The idea for TAO emerged after the center got funding to hire three more counselors, which Benton thought would help them eliminate their waiting list. Instead, it only bought them two weeks without a waiting list.

"It just seemed like every time we got an increase in funding and got more staff, we just had more students who wanted services," she recalls. The realization forced her to rethink how the center delivered care. TAO's success has been beyond Benton's expectations: When she compared the outcomes of the center's traditional face-to-face services with TAO's outcomes, the online clients' improvement in well-being and anxiety symptoms was significantly better than those receiving face-to-face therapy.

"It was phenomenal," says Benton, whose study on the results was submitted for journal publication in June. She thinks the program's success is due to how it's integrated into each student's life via smartphones — the technology allows students to do their therapy homework easily, and their counselors can monitor what students do during the week.

"Let's face it, we would all floss our teeth more often if our dentist could check up on us every few days and see if we were flossing," says Benton. She is now working with the school's office of technology and licensing to develop TAO into a commercial product and is investigating a similar prototype to treat substance abuse and depression among college students.

Education and awareness

Counseling centers are also reaching out beyond the therapist's walls in another way: working with faculty to include wellness awareness in their interactions with students.

"Certainly the bread and butter of what counseling centers do is seeing and treating individuals, but there's a significant amount of campus policy, faculty and staff training, consultation, outreach/prevention, and crisis work they provide as well," Douce says.

Data from the AUCCCD survey confirm that counseling centers are getting involved in more and more aspects of the university, says David Reetz, PhD, director of counseling services at Aurora University in the suburbs of Chicago, and one of the survey's lead authors.

The association's data show that a typical counseling center staffer spends about 65 percent of his or her time in direct clinical service, and another 20 percent to 25 percent of time on outreach initiatives, such as training students, faculty and other staff in mental health issues, as well as offering suicide, sexual violence, and drug and alcohol prevention programs, Reetz says.

At Aurora University, for example, in addition to delivering presentations to faculty on ways to detect early signs of student distress, strategies to intervene and techniques for referring them to the appropriate mental health services, Reetz instructs faculty on the best ways to increase student motivation, pulling in concepts from the psychological literature on resilience, growth mindsets and grit. "We're taking psychological concepts that we … have been using in one form or another in the clinical setting and helping faculty think about how they can … infuse these concepts into their curriculum or into creating their classroom climate," Reetz says.

Some counseling centers are beefing up their efforts to help all students understand the importance of mental health. That's essential, since 78 percent of students with mental health problems first receive counseling or support from friends, family or other nonprofessionals, suggests a 2011 study led by Eisenberg ( Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease ).

One popular alliance among counseling centers and students is Active Minds . The organization's more than 400 student-run chapters throughout the United States support efforts to remove the stigma around mental health issues. For example, the Active Minds' "Send Silence Packing" is a traveling exhibition of 1,100 donated backpacks that represent the number of college students who die by suicide each year. "The backpacks are spread out in a high-traffic area on campus, like the quad, and it's impossible to walk by without taking notice," says Sara Abelson, senior director of programs at Active Minds. "It helps students recognize the need to pay attention, because we all have a role to play in preventing suicide."

Abelson says the organization is also dedicated to championing the idea that student mental health and well-being are central to the mission, purpose and outcomes of every school — and that they need to be a priority.

"I think we're beginning to see more and more universities recognizing that creating a healthy climate and an open dialogue about mental health needs to be a priority," she says. "They're also realizing that it can't just be the responsibility of the counseling center, but that this is relevant across the university, and that everyone from the students to the administration needs to be playing a role."

Amy Novotney is a journalist in Chicago.

Related Articles

- APA partners to review college student mental health

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What to Know About Peer Pressure

It's not as simple as just saying no

- Positive Peer Pressure

Peer Pressure vs. Parental Influence

Peer pressure beyond childhood.

Have you ever been pressured to have "one more drink," or stay out later than you said you'd be home? If so, you've been a victim of peer pressure—chances are, most of us have. Peer pressure is the process by which members of the same social group influence other members to do things that they may be resistant to, or might not otherwise choose to do.

Peers are people who are part of the same social group, so the term "peer pressure" refers to the influence that peers can have on each other. Usually, the term peer pressure is used when people are talking about behaviors that are not considered socially acceptable or desirable, such as experimentation with alcohol or drugs. According to child and adolescent psychiatrist Akeem Marsh, MD , "it’s very easy to be influenced by peer pressure as we humans are wired as social creatures."

sturti / Getty Images

Though peer pressure is not usually used to describe socially desirable behaviors, such as exercising or studying, peer pressure can have positive effects in some cases.

What Is an Example of Peer Pressure?

Peer pressure causes people to do things they would not otherwise do with the hope of fitting in or being noticed.

For adolescents, peer relationships are the most important of all thus leading to an increased susceptibility to peer pressure.

Things people may be peer pressured into doing include:

- Acting aggressively (common among men)

- Bullying others

- Doing drugs

- Dressing a certain way

- Drinking alcohol

- Engaging in vandalism or other criminal activities

- Physically fighting

- Only socializing with a certain group

Peer pressure or the desire to impress their peers can override a teen or tween's fear of taking risks, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse for Kids. Risky behavior with drugs and/or alcohol may result in the following:

- Alcohol or drug poisoning

- Asphyxiation

- Driving under the influence (of alcohol or other drugs)

- Sexually transmitted diseases

Behavioral Addiction

People can also feel an internal pressure to participate in activities and behaviors they think their peers are doing, which can put them at risk for the following behavioral addictions:

- Food addiction

- Gambling addiction

- Internet addiction

- Sex addiction

- Shopping addiction

- Video game addiction

In the case of teens, parents are rarely concerned about the peer pressure their kids may face to engage in sports or exercise, as these are typically seen as healthy social behaviors. This is OK, as long as the exercise or sport does not become an unhealthy way of coping, excessive to the point of negatively affecting their health, or dangerous (as in dangerous sports).

What starts out as positive peer pressure may become negative pressure if it leads a person to over-identify with sports, for example, putting exercise and competition above all else.

If taken to an extreme, they may develop exercise addiction , causing them to neglect schoolwork and social activities, and ultimately, use exercise and competition in sports as their main outlet for coping with the stresses of life. This can also lead to numerous health consequences.

What Are Examples of Positive Peer Pressure?